ABSTRACT

Human emotions are profoundly social and this becomes particularly salient in the translation profession, where translators often need to withstand close scrutiny of their work by fellow translators, revisers, project managers, clients, etc. The emotions arising from those relationships can be remarkably diverse, from mild to intense, from negative to positive. Similar emotions arise amongst our students when we ask them to engage with authentic, project-based learning. Simulated Translation Bureaus (STBs), for instance, mimic the stresses and strains of the real workplace and therefore generate similarly strong emotions. How can we help our students manage these? Could emotional intelligence be a new dimension to introduce into translator training programmes around the world? According to Trait Emotional Intelligence theory (Trait EI), we cannot ‘enhance’ our students’ personalities, but knowing what kind of personality they have, and the behavioural dispositions they are prone to, may help them to develop coping strategies in the face of adversity. This paper explores the usefulness of Trait EI theory in translator education by applying it to students enrolled on STBs at Newcastle and Swansea universities.

1. Introduction

In what Schmitt (Citation2019) calls ‘Translation 4.0’, the role of translators is becoming much more complex, multi-faceted and ill-defined (see also Risku and Schlager Citation2021). As translator educators, we therefore need to help our students learn to tolerate ambiguity (see Hubscher-Davidson Citation2018b) by developing what Angelone (Citation2022) calls ‘adaptive expertise’. Because they require students to work on ill-defined tasks, Simulated Translation Bureaus (STBs), which are a form of authentic project-based learning in which translator competence is seen as ‘emergent’ (Kiraly Citation2013, 206), seem the perfect way to do so.

STBs, where students create and run their own fictitious translation agencies for course credit, require students to work closely with others to deliver translation projects under tight deadlines. Although they can take different forms (Buysschaert, Fernandez-Parra, and van Egdom Citation2017), they generally act as a mock workplace that generates similar levels of stress as the real workplace, but in a safe educational environment (Kerremans et al. Citation2018). For many students, taking part in an STB can give rise to a whole range of emotions, both positive (excitement and joy) and negative (fear and anger). Indeed, when put in a situation where they have to meet tight deadlines, while not being able to control every aspect of the project, some students may experience feelings of stress similar to those experienced by professional translators (Courtney and Phelan Citation2019).

How do we deal with our students’ emotions in STBs, then? Can we help them manage their emotions better? If so, how? Could emotional intelligence be a new dimension to be added to translator training programmes around the world? This is what we have tried to answer with the present study that explore for the first time the potential of adding an emotional intelligence dimension – Trait Emotional Intelligence (trait EI) theory – to translator education to support students’ wellbeing in the UK university context. We chose this theory, which is rooted in personality theory, as viewing emotional intelligence (EI) as a personality trait, instead of an ability, allows for a straightforward measurement of subjective emotions (Petrides, Niven, and Mouskounti Citation2006). In addition, Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr (Citation2021) recently argued for the relevance of EI theory, which ‘enjoy[s] widespread empirical support’ (Petrides Citation2010, 138), in translation contexts.

2. Emotions, translation and translator education

Of course, the study of aspects of emotional intelligence is not new. In order to achieve our aim, our study builds on research that has integrated constructs from the field of psychology into translation studies by exploring the possibilities of integrating trait EI into translator education.

2.1. Emotion and translation

Since James Holmes (Citation1972/2000, 177) first petitioned for more research into what he called ‘translation psychology’, there has been an increasing number of studies researching the role of emotions in translation from a process-oriented perspective (for a historical review of these, see Bolaños-Medina Citation2016). These studies have brought to our attention the fact that a translator’s emotional attitude either towards the task or themselves (level of confidence in their ability to complete the task) can impact the quality of the work they produce (see Fraser Citation1996; Jääskeläinen Citation1999; Laukkanen Citation1996).

More recently, Koskinen published Translation and Affect, in which she borrows concepts from the fields of psychology, neurosciences and sociology to further explore the role of emotions in translation. To her, translation as a service is ‘affective labour’ because it requires ‘the creation and manipulation of emotions, the production and distribution of feelings, and the management of affinity or distance’ (Koskinen Citation2020, 30). Interestingly, Koskinen focuses not only on the relation between the translator and the text to translate, but also on the wider context:

The contemporary networked translation industry provides constellations of mutual dependence where translators, project managers, revisers, terminologists and IT people and other parties are in constant, albeit often virtual and indirect, contact. […] These networks of relations provide a second layer of affective labour. […]

Further, it has been evidenced that the use of translation technology can be a source of ‘cognitive friction’ for (trainee) translators (O’Brien et al. Citation2017). This, in turn, can generate what Koskinen (Citation2020, 146) calls ‘technostress’, which ‘reduces performance and harms individual wellbeing’.

Negative affects (or ‘negative emotions’) in translation, we can conclude, can lead to diminished wellbeing and decreased job satisfaction, which could make translation as a profession less sustainable (Hubscher-Davidson Citation2020). If emotions can have an impact on translators’ wellbeing, one can wonder if the way individual translators perceive, regulate and express their emotions has an impact on their ability to thrive in the profession. This is what Hubscher-Davidson (Citation2018a) attempted to find out in Translation and Emotion, the first large-scale attempt to research the link between translator personality and emotions. Her empirical study confirmed that ‘emotional intelligence plays a role in translators’ job satisfaction and award/prize winning success, as well as stress resilience and wellbeing’ (Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr Citation2021, 18). In her study, Hubscher-Davidson saw beyond emotional intelligence as pure cognitive ability and therefore adopted a trait model of EI instead.

Unlike ability models that see EI as an ‘ability’ to be assessed by intelligence-like tests, trait models see EI as a ‘disposition’ that can be evaluated by personality-like questionnaires (Nelis et al. Citation2009, 36). Hubscher-Davidson thus adopted Petrides’s conception of EI as measured by self-report questionnaires of ‘trait emotional intelligence’. In that sense, trait EI is a ‘theoretical framework that integrates emotions, personality traits, and intelligence, broadly defined’ (Petrides Citation2021). It can be understood as ‘a constellation of behavioural dispositions and self-perceptions concerning one’s ability to recognise, process, and use emotion-laden information’ (Petrides, Frederickson, and Furnham Citation2004, 278). In Petrides’s trait EI theory, therefore, EI is conceptualised as a ‘distinct (because it can be isolated in personality space), compound (because it is partially determined by several personality dimensions) construct that lies at the lower levels of personality hierarchies’ (Petrides, Pita, and Kokkinaki Citation2007, 283), meaning that it is rooted within individuals. Hubscher-Davidson justified her choice of trait EI theory as a framework for her study as follows:

[…] there are certain stable personality traits and behavioural dispositions that are helpful for successful translation and others that are less so. Trait theory, in my view, also enables the characterisation and understanding of translators and the differences between them.

2.2. Trait EI theory and translator education

Hubscher-Davidson’s empirical study looked into professional translators’ personality traits and behavioural dispositions. This highlights one of the features of recent studies into emotions and translation: most of them tend to focus on professional translators. To our knowledge, at the time of writing, few empirical research studies have been carried out on the impact of personality traits on trainee translators’ ability to successfully manage their emotions and, therefore, succeed in translation (with some notable exceptions such as, for instance, Rojo López et al. Citation2021). This is despite the fact that, as stated earlier, trainee translators who are asked to engage with authentic, project-based learning by working in an STB often experience feelings very similar to those experienced by professional translators. A reason for this might be the collective nature of STBs that requires students to engage with at-times complex ‘networks of relations’, which they may have never done before. These networks constitute a ‘second layer of affective labour’ (Koskinen Citation2020, 39) that some students must learn to navigate. What is more, many students also experience the feeling of ‘technostress’ described by Koskinen (Citation2020, 146) about professional translators, not least when they have to use translation technology autonomously as part of a complex translation project.

How could trait EI theory help students navigate this second layer of affective labour in translator education, especially during experiential learning? As we have already mentioned, trait EI theory sees EI as a personality trait and not an ability. To put it simply, ‘[t]rait EI is concerned with our perceptions of our emotional ability, that is, it captures how good we think we are at perceiving, regulating, and expressing emotions in order to adapt to our environment and maintain wellbeing’ (Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr Citation2021, 23). With trait EI theory, the focus is therefore not on what individuals know or can do but on ‘what they consistently do’, as seen by themselves (21). The fact that, with this theory, EI is conceived as a personality trait suggests that it is relatively stable over time. However, empirical studies have shown that ‘short and well-designed interventions are capable of modifying and influencing individuals’ emotional competencies, […] and that these changes can be effective for some time post-intervention’ (33; see also Hodzic et al. Citation2018; Kotsou et al. Citation2019). This suggests that EI traits are somewhat malleable. Mikolajczak’s model, which ‘conceptualises [EI] as a three-level model which integrates individual differences in emotion-related knowledge, abilities and dispositions’ (Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr Citation2021, 22), can help us understand why interventions targeting all three levels of EI could prove particularly effective. In this model, the three levels of EI are (Mikolajczak Citation2009, 27):

Knowledge: The first level of EI, which focuses on ‘the knowledge a person has about emotions and how to deal with emotion-laden situations’;

Abilities: The second level of EI, which refers to ‘the ability to implement a given strategy in an emotional situation’;

Dispositions: The third level of EI, which is ‘the propensity to behave in a certain way in emotional situations’.

As the last level of EI, dispositions are ‘captured by all emotion-related traits’ (Mikolajczak Citation2009, 27). However, Mikolajczak (27) notes that some people do what they do in emotional situations because they do not have the knowledge or the ability to do otherwise. In this model, the three levels of EI-related individual differences are therefore ‘loosely connected’; knowledge does not necessarily – but can – translate into abilities which, in turn, do not always – but can – translate into dispositions. Interventions that target EI knowledge and abilities could therefore lead to improvement in the EI disposition level, as attested by recent studies (see Campo, Laborde, and Mosley Citation2016).

Interestingly for us, ‘[trait] EI can be taught in courses or embedded systematically into one’s environmental context, and learned’ (Mpofu et al. Citation2017, 288). Using trait EI theory to embed EI literacy as part of soft skills training could have positive pedagogical implications for translator training. It is, for instance, now well-documented that there is a ‘positive association between trait EI and well-being related variables’ (Nelis et al. Citation2009, 36), as trait EI can help respond better to stress and increase general wellbeing (Dave et al. Citation2021). Further, ‘high EI contributes to increased motivation, planning, and decision making, which positively influence academic performance’ (Fernando et al. Citation2011, 152). Concerning professional translators in particular, Hubscher-Davidson’s research findings (Hubscher-Davidson Citation2018a, 196–197) suggest that translators with high trait EI are more likely to report higher job satisfaction. This could explain why there have been calls of late for translator training programmes to further embed emotional literacy and EI as part of soft-skills development (see Hubscher-Davidson Citation2018a; Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr Citation2021; Perdikaki and Georgiou Citation2022). Indeed, another of Hubscher-Davidson’s studies also found that focused EI training ‘can develop translators’ trait EI level and have real effects on behavioural modification’ which, in turn, ‘may enhance performance in ambiguous situations and […] facilitate the resolution of complex emotional decision-making’ (Hubscher-Davidson Citation2018b, 94). Embedding trait EI theory through interventions therefore appears to be an appropriate way to better support trainee translators engaging with experiential learning on STBs.

Using both quantitative and qualitative data, our study’s main hypothesis is therefore that trait EI theory can help improve students’ experience on STBs and that translator trainers around the world could find EI training effective if integrated into their translation courses. To probe our hypothesis, we will first look into whether a self-report questionnaire based on trait EI theory can be used as a helpful baseline survey that gives us a pre-STB snapshot of a cohort’s EI (Dispositions) and, consequently, insights into their trait EI facets that could be seen as less adaptive/functional for the purposes of an STB. Raising awareness of a cohort’s EI profile (Knowledge), and offering extra support around those identified needs, could in turn help students develop appropriate strategies to manage their cohort’s less adaptive/functional trait EI facets more successfully during the STBs (Abilities). We will also then explore whether students feel they have developed (other aspects of) their EI as a result of openly discussing the potential role of emotions while taking part in an STB (Dispositions). This could mean that using trait EI theory to raise awareness of the role of emotions during authentic, project-based learning could also help our students enter the translation industry as better prepared, more resilient individuals who take better care of their wellbeing.

3. Methodology

Our study took place across two higher education institutions in the UK, Newcastle University (NU) and Swansea University (SU). At both institutions, translation and interpreting students take part in an STB in order to develop some essential translator skills experientially. At NU, this happens on the final-year translation module of the undergraduate Translation degree programme. At SU, however, Translation students can take part in an STB at both BA and MA level.

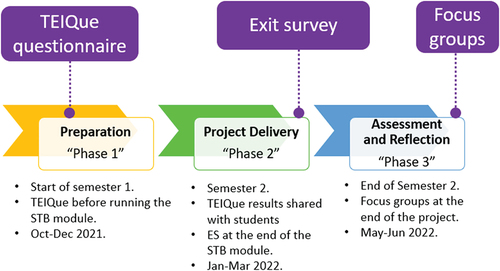

All STBs followed the same timeline of Preparation, Project Delivery and Assessment and Reflection (see ). In Phase 1, students were trained in translation project management (including terminology management) as well as in the use of the technology they would need to deliver the project. Students were then allocated to an STB, assigned a specific role (project manager, terminologist, IT manager, etc.) on top of their role as translator, and asked to start working collectively on setting up their STB. In Phase 2, collaborative work started with all STBs working autonomously on delivering the translation projects commissioned by their ‘clients’ (the tutors). Finally, during Phase 3 all students were asked to reflect critically on the hard and soft skills they had developed by taking part in an STB as part of the assessment strategy.

3.1. Setting and participants

At both institutions, all students taking part in an STB were invited to join the study. Of the 33 eligible students, 24 agreed to take part (10 at NU and 14 at SU). Out of the 24 students, 13 were undergraduate students (10 at NU and 3 at SU) and 11 were postgraduate students. Most of the participants in the study were female; there were only 5 male students (3 in NU and 2 in SU) and 1 student preferred not to say. 14 of the participants were in the 18–22 age bracket. However, at NU this age bracket represented 70% of participants as opposed to 50% at SU. 8 participants were in the 23–25 age bracket (2 at NU and 6 at SU). Only 2 participants were in the 26–30 bracket (1 at NU at 1 at SU).

3.2. Research design and data collection

This study adopted a mixed-methods research design that combined qualitative and quantitative data. During Phase 1, a psychometric instrument – the TEIQue – was used as a baseline survey to obtain a snapshot of students’ EI dispositions. This self-report questionnaire was chosen because it is based exclusively on trait EI theory and allows for a comprehensive measurement of trait EI (Petrides Citation2011). Based on the published empirical research, we agree that findings from self-report questionnaires tend to be accurate as there are ‘strong correlations between self-reports and actual behaviours’ (Hubscher-Davidson Citation2018a, 46). Further, it has also been found that, compared with other self-report measures of EI, TEIQue has ‘superior psychometric properties and greater validity’ than other self-report measures of EI (Andrei et al. Citation2016, 263).

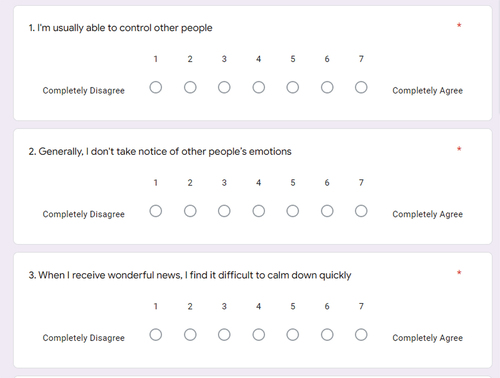

TEIQue is available in short form (30 questions) or long form (153 questions); both forms are available free of charge for academic research purposes. The long TEIQue, the one used in the present study, takes around 30 minutes to complete and the 153 items have answers on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 is ‘completely agree’ to 7 ‘completely disagree’. It provides scores for 4 factors (Wellbeing, Self-Control, Emotionality and Sociability) subdivided into 15 facets (such as Self-Esteem, Assertiveness, Emotion Regulation, Emotion Expression or Stress Management). The broader factors are illustrated in together with the facets they contain. At the time of writing, the TEIQue can be downloaded from the Psychometric Lab website: https://psychometriclab.com/obtaining-the-teique/.

Figure 2. The factors and facets of the TEIQue questionnaire used to evaluate a person's general emotional functioning (Source: Petrides Citation2023; see also Petrides Citation2009, 93).

The TEIQue questionnaire also generates a global trait EI score, thus giving a quantitative assessment of the emotional world of the participants (Dispositions). However, our students did not see any of the labels for the factors and facets, such as Wellbeing, Self-Control, etc. Students were simply asked questions such as the ones shown in and they were asked to select the answer that fitted most closely how they perceive themselves to be, which is how the TEIQue was designed to be conducted.

For the purposes of our study, we prefaced the TEIQue with a few questions tailored specifically to the needs of our own study. This included questions about gender and age, but also about how the participants perceived themselves as translators before embarking on the STBs, which provided us with more fine-grained background information to help contextualise the results.

Students answered the TEIQue completely anonymously. The data from the TEIQue was used to profile each cohort’s overall EI profile before students started working collectively in their STBs. The scores obtained from the TEIQue allowed us to identify each cohort’s facets of EI that could be seen as less adaptive/functional for the purposes of an STB (i.e. where students scored lower) and where, therefore, specific interventions may be needed to support them better during Phase 2. The first intervention consisted of sharing each cohort’s TEIQue results with the students at the start of Phase 2. No individual scores were provided, simply an anonymised averaged group-level score. This allowed for an open discussion around the potential implications of their overall EI profile for their work on the STBs during Phase 2. This discussion aimed to enhance students’ emotion-related Knowledge and Abilities (Mikolajczak Citation2009, 27). We discussed, for instance, how a cohort’s relatively high score for the EI facet Empathy could be seen as indicative of a particularly adaptive/functional trait for the collaborative nature of work on STBs. Conversely, if a cohort scored lower on Emotion Perception (i.e. the ability to be clear about your own and other people’s feelings), it may indicate that this cohort could benefit from heightened awareness of the impact of their emotions on the way they exchange messages during Phase 2 and implement appropriate strategies. This awareness could result, for instance, in greater care being taken to deliver considerate messages in the professional context of STBs, especially during pressure points. Based on each cohort’s TEIQue scores, we thus identified relevant wellbeing workshops delivered by our respective institutions (e.g. on managing conflict) that could serve as specific interventions and strongly encouraged students to attend them in the first few weeks of Phase 2. Finally, during this initial intervention we also discussed the implications of the fact that these were cohort-level – as opposed to individual – results; students would have to bear in mind during Phase 2 that everyone’s trait EI profile is different.

At the end of Phase 2, once all STBs had ceased trading, students were asked to complete an Exit Survey (ES; see ). Completed anonymously, the ES consisted of 24 items, most of which were self-report 7-point Likert scale items (1 being the lowest and 7 the highest). The ES aimed to gather quantitative data around students’ perceptions of their own emotion management – as well as other group members’ – on the STBs (questions 4–18), and the impact they felt this may have had on their engagement with the STBs (questions 19–20). It thus allowed us to gather insights into students’ perceived abilities during the STBs. It also aimed to obtain some insights regarding students’ engagement with the project interventions (question 2–3) and how successfully they felt these had been in helping raise their awareness of the key role of emotions (Knowledge) not just on STBs, but on all collaborative translation projects (questions 1, 22–23).

Table 1. Results from the TEIQue questionnaire and global trait EI scores (C = Cronbach’s alpha [α]; SD = standard deviation [σ]).

Table 2. Results from the Exit Survey (ES).

After completing the ES, each cohort was invited to a focus group (FG) during Phase 3 so that qualitative data could be added to the quantitative data gathered with the ES. Both FGs used the same as prompts to explore whether students felt they had increased their awareness of trait EI and its impact on their work as a result of direct interventions such as the session discussing their EI profile, attending wellbeing workshops, and discussing openly the potential role of emotions throughout the project. This was in line with studies that have shown that interventions focusing on all three levels can have an impact on trait EI (see Nelis et al. Citation2011). Alongside the ES, the two FGs thus also enabled us to find out more about whether students felt their perception of the potential role of emotions on their performance, not just in the STBs but also in professional translation settings, had changed as a result of this project.

3.3. Ethical considerations and limitations

Our study adhered to the British Education Research Association’s Ethical Guidelines for Education Research (Citation2018). However, our dual roles as lecturers/researchers on the project caused ‘explicit tensions in [the] area of confidentiality’ (British Educational Research Association Citation2018, 13). Due to the rather personal nature of the questions contained in the TEIQue, the idea that we, as their lecturers, could trace individual students’ answers back to them could have caused undue stress. This is why it was decided that students be asked to complete the TEIQue completely anonymously, despite the fact that this created a first limitation for our research project, as results could only be analysed at cohort level.

As completing the TEIQue takes around 30 minutes, we decided not to ask our students to take it again at the end of Phase 2 but to take a shorter ES instead. This was in order to lighten their workloads, avoid questionnaire fatigue, and focus the post-experiment survey on questions more relevant to our students’ recent experience on STBs. The ES still provided valuable insights into students’ perceptions of their own emotion-management during the STBs, and the perceived effectiveness of the extra support we offered.

Concerning the focus groups, our above-mentioned dual roles may also have had an impact on what students decided to share with us. Despite our best efforts to create a relaxed and friendly atmosphere during the focus groups, some of our students may have given us the answers they believed we wanted to hear as their lecturers. Nevertheless, we believe that despite these limitations we managed to gather the data we needed to answer our research questions while protecting our students’ rights.

The absence of control groups in our project is also a result of ethical considerations. Control groups may have helped to validate or discredit the idea that interventions influenced the EI of the students exposed to them as part of our project. However, this would have meant purposely depriving some of our students of the extra support to manage their emotions during Phase 2, which could have put them at a disadvantage.

Finally, concerning the use of TEIQue, we must stress that judgements about individuals in relation to the TEIQue should be predicated on as wide an evidence base as possible and should combine information from multiple sources. We must also add that this project focused on emotion management on STBs, but that there are numerous other competences that trainee translators will also need to develop to engage successfully with a collaborative translation project (see, for instance, EMT Citation2022).

4. Results and discussion

In this research, of 33 eligible students 24 volunteered to complete the TEIQue in Phase 1. At the end of the project, 17 students out of the 24 who had completed the TEIQue volunteered to complete the ES, and 14 volunteered to take part in the focus groups. This allowed for the quantitative scores from the TEIQue to be complemented with more translation-specific and STB-specific questions in the ES and with qualitative data from the focus groups.

4.1. Results from the Trait EI Questionnaire (TEIQue)

The TEIQue was made accessible to our students through Google Forms in the autumn of 2021 and the responses were collected in an Excel spreadsheet. This spreadsheet was uploaded to the TEIQue website in order to obtain the automatically generated global trait EI scores for our cohorts. As we have seen, the questionnaire consists of 153 items. The participants had to rate each item on a scale of 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Participants’ responses allowed us to obtain a global trait EI score, which is a ‘broad index of general emotional functioning’ (Petrides Citation2021), as well as scores for the 4 factors and each of the 15 facets. We generated scores for each cohort separately (NU; SU), as well as for both cohorts combined (NU+SU) (see ). Higher scores suggest more adaptive/functional EI facets, while lower scores suggest less adaptive/functional EI facets. also shows the mean, the Cronbach’s alpha and the standard deviation.

The scores for NU, SU as well as NU+SU are summarised by the global trait EI scores shown at the bottom of . The global trait EI for NU+SU was 4.84, with low standard deviation (0.45) despite some outliers in the data. In this study, the internal consistency for global trait EI was good despite the relatively small sample (α = .81). The global trait EI for NU was 5.09 (α = .80). For SU, it was 4.6 and we should note the lower Cronbach’s alpha (α = .64).

shows that both NU and SU students achieved similar scores across the four factors overall. Both cohorts scored highest on Wellbeing (5.15; α = .81) and Emotionality (5.23; α = .69). Based on their own assessment, NU and SU students therefore seemed to possess the interpersonal skills and the self-confidence required to embark on an STB. On the other hand, both cohorts scored lowest on Self-Control (4.35; α = .43) and Sociability (4.66; α = .80).

In order to determine more specifically the facets of EI where our students could benefit from greater support during Phase 2, we singled out the three facets with the lowest score and with a Cronbach score greater than .70 for each cohort. At both NU and SU, the two lowest-scoring facets were both from the Self-Control factor: Emotion Regulation (NU: 4, α = .86; SU: 3.84, α = .76) and Stress Management (NU: 4.42, α = .85; SU: 4.04, α = .77). The fact that, according to the TEIQue scores, our students would benefit from enhanced support in relation to these two facets brought empirical evidence to the intuition that set this project’s wheels in motion. Indeed, students’ ability to control their emotions and manage their stress levels could have a big impact on the way they experience – and perform on – complex, collaborative translation projects where they will likely experience frustrations while trying to solve new challenges (see Hubscher-Davidson Citation2018b).

At NU, the third lowest-scoring facet Assertiveness (4.51; α = .91) was from the Sociability factor. At SU, however, it was Self-Esteem from the Well-being factor (4.18; α = .77). This cohort had scored lower on the auxiliary facet of Adaptability (4.16) but this facet was not a focus of the present study due to the lower reliability score (α = .65).

The background questions at the beginning of the TEIQue questionnaire can help us shed light on the difference between the two cohorts. As 70% of NU respondents were in the 18–22 age bracket, we can venture that age may have had an impact on how students perceive their own ability to be forthright and stand up for their rights. However, it seems more difficult to explain the lower Self-Esteem score for the SU cohort (and we should note that this score was also lower for the NU cohort). Some factors, not captured in this study (such as the greater number of international students in the SU cohort), may help explain this. Indeed, there may be a cultural and linguistic dimension at play here as the TEIQue was designed based on a Western understanding of emotions; reading and answering TEIQue questions that probe how successful and confident you see yourself in a language that is not your mother tongue may well have had an impact on the scores (see Gökçen et al. Citation2014; Harzing Citation2006). This is something we believe is worthy of further exploration in future studies.

On the basis of the TEIQue results, we organised targeted interventions. As previously mentioned, we started with an initial one-hour informal session at the beginning of Phase 2 during which we drew our students’ attention to the importance of Emotion Regulation and Stress Management (both NU and SU) and Assertiveness (NU) or Self-Esteem (SU) in relation to the STBs (Knowledge). We also encouraged them to attend relevant wellbeing workshops organised by our respective institutions that would help them with these specific facets of EI during Phase 2 (e.g. NU workshop Managing Interpersonal Conflict in Group Work [Emotion Regulation]; SU workshop Skills for Life [Self-Esteem, Abilities]).

4.2. Results from the Exit Survey (ES)

The ES was completed anonymously in the spring of 2022 by 17 of the 24 TEIQue respondents (NU: 70%; SU: 71%). We devised this questionnaire ourselves in order to gather data on students’ perception of the effectiveness of the support we put in place around emotional intelligence as part of this project for engaging more effectively with the STBs. To this end, the ES collected additional quantitative and qualitative information on students’ perceived experiences with the STBs (Abilities). The combined scores from the 24 Likert-type questions of the ES, including standard deviation scores, are shown in .

Respondents’ answers to the ES give us some information as to students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of our interventions around each cohort’s EI needs identified by the TEIQue survey. At both NU and SU, Stress Management and Emotion Regulation were identified as less adaptive/functional traits. In the ES, question 16 asked students to rate, on a scale of 1 to 7, how successfully they thought they had managed to cope with pressure and regulate their own stress during the STBs (see ). Whether this was a result of the interventions or not, SU students self-reported very successful stress management during the STBs (6; σ = .82). For NU, the lower score of 4.86 (σ = 2.12) seems to indicate that students had more difficulty in coping with pressure and regulating their own stress during the STBs despite our interventions. However, the high standard deviation also indicates a wider distribution of results and, therefore, greater variation in the way NU respondents perceived their own stress management during the STBs. Similarly, question 14 asked students to rate, on a scale of 1 to 7, how successfully they thought they had managed to stay in control of their emotions during the STBs. Again, most SU students self-reported very successful emotion management during the STBs (6; σ = 1.05). NU students, however, reported a much lower score of 4 (σ = 2.16). As in question 16, however, the wide distribution of results indicates differing perceptions around successful emotion management on STBs for this cohort.

Assertiveness (NU) and Self-Esteem (SU) were the other cohort-specific EI traits that had been identified as less adaptive/functional that were, therefore, the object of targeted interventions for the purposes of the STBs. Concerning Assertiveness, NU respondents’ answer to question 9, the very high score of 6.29 (σ = 0.95) seems to suggest that they felt they had the appropriate coping strategies (Abilities) to be assertive in their STBs (see ). It is interesting to note, though, that NU’s score for this question remains marginally lower than SU’s (6.40, σ = 0.84) despite the fact that SU students did not benefit from specific support on this trait EI facet. As for Self-Esteem, SU respondents’ relatively high score of 5.80 (σ = 1.03) for question 6 seems to suggest that the project’s support may have helped them feel more confident about their contributions to their STBs (see ). Similarly, though, we should note that SU’s score for this question remains lower than NU’s (6.29, σ = 1.11), despite the fact that NU students did not benefit from specific interventions on this.

As the ES asked students directly about their perceived abilities on the STBs, we should note that there may have been an element of social desirability at play in students’ answers (Saldanha and O’Brien Citation2013, 153). This notwithstanding, by and large both NU and SU students scored well on the ES in relation to regulating their emotions, managing their stress, being assertive, and having self-esteem during the STBs (Abilities). However, this does not seem to have arisen from their attending the suggested wellbeing workshops that were meant to serve as specific interventions around each cohort’s less adaptive/functional EI facets as identified by the TEIQue. Indeed, the answers to question 3 show that none of the ES respondents attended the workshops in question (see ). Question 3a gave us some reasons for this. Out of the 17 respondents, 6 students said they were not able to attend for a variety of reasons ranging from timetabling issues to inconvenient days or times, so it is possible that these students might have attended a workshop had the circumstances been more favourable at the time. 4 students did not attend because they said they did not know about the workshops. Another 2 students did not attend because they wanted to focus on delivering the translations by the deadline. Finally, 1 student said they had already attended similar workshops in previous years. Although, at first glance, it appears that many students did not attend the workshops, under better circumstances and with more preparation and dissemination of information, there could have been as many as 10 students attending the signposted workshops.

Despite students’ lack of engagement with the wellbeing workshops, some of the project’s other interventions seem to have contributed more directly to these relatively high scores on the ES, indicating increased awareness of the importance of emotions and emotion management on STBs (Knowledge). Students’ answer to question 2, for instance, shows that they found it helpful to see their cohort’s Trait EI profile before embarking on the STBs (see ). This was further supported by students’ qualitative comments in question 2a that asked them to justify their answer to question 2. 14 students answered the question, with 4 of them saying they found the process useful, providing comments such as ‘good to know’ or ‘really helpful’. Another 2 students found it helpful from their own perspective, with comments such as ‘helped me manage my expectations’ and ‘good emotion can help me do the job efficiently’. Interestingly, 5 students replied from a group’s perspective, thereby displaying their understanding of the importance of taking others’ emotions into account as well as their own on STBs: ‘Performing as a cohort is very important. […] Emotional intelligence makes up a very important part of a group’s performance’ and ‘It was definitely helpful to understand where the concerns were. […] The session specifically tackling these concerns and emotions was also brilliant for our team to better understand each other’.

As attested by the scores for questions 19 and 20 of the ES (4.88 and 4.94 respectively), students generally agreed that discussing the role of emotions before the running of the STBs helped them become more aware of the potential impact of their emotions, as well as those of their fellow team members, on successful contributions to the STBs. When looking at respondents’ scores for question 21 and question 1, it is clear that students feel the project has heightened their awareness of the important role played by emotions in collective translation projects such as STBs (Knowledge). When respondents reported a score of 4.47 (σ = 1.23) for the importance they gave to emotions on STBs before the project started (question 1), the score rose to 5.35 (σ = 1.17) after completing the project. Based on responses to question 22, a majority of respondents also felt that this heightened awareness of the importance of emotions on STBs helped them contribute more successfully to their STB (5.18, σ = 1.38). The highest score (5.71, σ = 0.92), however, was for question 24 that asked the students to recap their entire perception of this project’s usefulness for their professional career (see ). Interestingly, the standard deviation score indicates a relatively narrow distribution of individual scores, which in turn suggests that a high number of respondents agreed that the project and intervention helped them reflect on their own emotions in collaborative contexts and for their future career ambitions.

These positive findings may not be entirely attributed to our targeted interventions, but at least they will have served to raise students’ awareness of their own emotions and how to deal with them (Knowledge and Abilities). This is further attested by the ES’s final and open question which elicited answers such as: ‘Thanks to this project, now I am aware of my weak and strong sides. Emotions have played a tremendous role in this project. It could be easier if people were more comfortable with sharing their emotions’. However, another answer to this question is worthy of our attention here:

Could there be more emphasis on how your actions can make other individuals in the group feel/react? I believe that the emotions training was very helpful, but how people responded in our group didn’t necessarily correlate with how they acted during the project.

This answer contains a suggestion for the future, that is to say, putting greater emphasis on how our actions can make others feel. Taking a coaching approach to emotion-management during STBs alongside the workshops could be a particularly apt way to do so. Indeed, as highlighted by Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr: ‘Engaging with silent questioning is critical to self-awareness and to being able to understand or empathise with other points of view’ (Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr Citation2021, 54). This is therefore an avenue for future research that we plan to explore in subsequent iterations of the project.

4.3. Results from the focus groups

The focus groups took place during Phase 3, after the completion of the ES. We conducted one focus group per university. In total 14 of the 24 students who had completed the TEIQue attended (NU: 4; SU: 10). These voluntary focus groups were semi-structured in that we prepared questions in advance but also encouraged open discussion about any aspects the students wanted to bring up. The 9 questions encapsulated the information we wanted to glean from the students regarding the role they thought their emotions played during the STBs, spread out through a number of questions. We also asked FG participants whether they had taken part in any of the signposted wellbeing workshops as we could not assume they had all completed the ES. Finally, we asked participants for feedback on how we could further help manage emotions on STBs. As the focus groups were conducted in hybrid mode, in person and over Zoom. We collected the transcripts and analysed them manually in order to extract relevant information.

As expected from a semi-structured interview, the discussions in the focus groups did not adhere too strictly to the 9 questions or to the order in which we had written them. Although we asked 9 distinct questions, the students used the same answers to different questions and therefore there is some overlap between questions. So, rather than presenting the answers to each question separately, we grouped the students’ responses into three broad themes: emotions about the STBs (both positive and negative), perceived achievements and feedback for future iterations.

In general, students reported more negative emotions than positive ones. However, students at both institutions highlighted that they had felt excitement and anticipation at the thought of taking part in an STB. This could equate to excitement and anticipation at the thought of starting a new job, for example. The list of negative emotions referred mostly to the time when they were running their STBs, and ranged from fear (1. of the unknown; 2 of letting oneself down; 3 of letting others down), to stress and frustration and an anticlimactic end of the project. In addition, some students felt the STB was a ‘roller coaster’ of emotions.

In terms of achievements, students reported that this project had made them learn to ‘take a step back’ and view their contribution to the STB more holistically which, in turn, helped them calm down and tackle issues more competently and confidently. A second achievement was that they had learned to separate friend relationships from business relationships. This was a common theme at both institutions: students had made friends on the course, but in STBs they were required to act professionally with each other which raised boundary issues, that is, when to be friendly and when to be professional. Finally, and importantly, students reported that they were certainly more aware now of the role emotions played in STBs and that they would definitely take them into account when embarking on their professional careers. In their own words: ‘I think, like, working on emotions and acknowledging them helped me to go: Okay … Right… I’m going to have emotions about this, but I don’t want them to sort of take over!’ Such comments in the FG can be seen as confirming what we observed from the ES; taking part in this project seems to have enhanced students’ emotion-related Knowledge and Abilities (Mikolajczak Citation2009, 27).

The focus groups enabled us to shed light on the potential impact of the workshops. One NU FG participant said they attended the signposted workshop that aimed to help with the trait EI facet Emotion Regulation: Managing Interpersonal Conflict in Group Work. They explained it had helped them understand the following:

No one intentionally wants to cause conflict so there’s always some sort of reason, or they have something going on that’s causing them not to be constructive […]. So it’s being able to step back from the situation and, say, […] instead of you just arguing with someone maybe asking them […] what’s causing them to act like that [and] is there anything you can do. And you end up resolving this situation, instead of just causing more conflict.

Another participant explained that they had booked to attend a workshop about emotions in teamwork but that they did not because of conflicting priorities. With hindsight, they said, they would prioritise the workshop. They further explained that after having had an especially challenging day (‘peak stress’) with their team on the STB, they decided to attend a life coaching session with an organisation outside the university. This session ‘[…] helped me to kind of decide how I was going to approach the fact that I wasn’t happy with that aspect of the group, how I was going to talk to people about it’. Again, this confirms that adopting a coaching approach with coaching activities such as the ones advocated by Hubscher-Davidson and Lehr (Citation2021, 51–65) could prove very effective in supporting students’ emotions during experiential learning.

The focus groups thus made it clear that the students who attended the workshops felt this was an effective way to develop coping strategies for specific aspects of their trait EI, and that the workshops had, therefore, improved their experience on the STBs. This aligns with findings that a workshop approach with group discussions and interactive participation is the most successful form of EI intervention (Hodzic et al. Citation2018, 145). Timetabling issues and a lack of awareness that workshops are high priority were frequent reasons given by students for not attending the wellbeing workshops. It seems that tailoring workshops to the students’ specific needs and embedding them directly into the course would be a better way to make sure students engage with them, rather than simply signposting them to workshops organised outside the module context.

The focus groups were also the opportunity for students to share their advice with us for future STBs. Firstly, students from both institutions said they would welcome more sessions on the role that emotions can play in STBs at the beginning of Phase 2. They claimed such sessions would help with their fear of the unknown and this could be partly achieved by embedding the wellbeing workshops more directly into the course. Students also asked for the tutors to touch base more regularly to see how students are feeling and whether any issues need addressing. Similarly, students in managerial roles in the STBs should also touch base regularly with their staff and freelance translators. ‘Little but often’ was the general consensus. Again, this seems to suggest that offering individual coaching sessions as the need arises, as well as interactive workshops, could prove an effective way to support students and enhance their emotion-related knowledge and abilities during the STBs which, in turn, could have a positive effect on their EI dispositions.

5. Conclusion

How do we deal with our students’ emotions on STBs? Should translator trainers seriously consider introducing an emotional intelligence dimension into translator training? These are the questions our project aimed to answer by undertaking an initial exploration of the usefulness of raising trainee translators’ awareness of the importance of EI in experiential translator education. Emotion-generating activities that aim to prepare our students for this profession, such as STBs, can be challenging for some students. Yet, they are very necessary. We therefore need to make sure we support our students effectively and holistically on STBs.

Based on our quantitative and qualitative results, it is our view that using the TEIQue as a baseline to capture a cohort’s trait EI profile, and fostering students’ perspective-taking by discussing the results with that cohort before an STB takes place, is an effective way for students to increase their awareness not just of their own EI, but also of that of fellow team members (Knowledge). Similarly, targeted workshops and talking openly about the important role emotions play throughout an STB can help students manage their emotions in general, and their cohort’s less adaptive/functional trait EI facets in particular, more successfully in their STBs (Abilities). Despite the noted limitations, this project’s EI intervention has thus helped students deal with what Koskinen (Citation2020, 39) calls the ‘second layer of affective labour’ as well as what Hubscher-Davidson (Citation2018b, 78) calls ‘tolerance of ambiguity’ on STBs. Students’ responses in the ES and FGs seem to suggest that this, in turn, has helped them contribute more successfully to their STBs through improved emotional efficacy.

Our study therefore seems to bring more evidence to the claim that EI training that focuses on emotion-related knowledge and abilities can help develop our students’ dispositions (Campo, Laborde, and Mosley Citation2016). This, in turn, can help improve students’ performance and wellbeing as translators. Of course, further data is required in order to make more conclusive claims, but these results already suggest that there is scope for expanding research (and training) in this area. Our project findings, for instance, seem to suggest that problem-based learning in general, and STBs in particular, can be seen as a means for trainee translators to develop their EI, provided they are well-supported throughout. Further empirical research into this is needed, however, before we can ascertain that fact. Similarly, there is still much to debate (e.g. to what extent translator trainers should integrate EI training in translator education and how this should be done), but we hope this study will have contributed to opening the doors to further research into how to ensure that our graduates enter the translation industry as better prepared, more resilient individuals who take better care of their wellbeing.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2023.2237327.

References

- Andrei, F., A. B. Siegling, A. M. Aloe, B. Baldaro, and K. V. Petrides. 2016. “The Incremental Validity of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Personality Assessment 98 (3): 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1084630.

- Angelone, E. 2022. “Documenting Adaptive Expertise, Diversification and Ill-Defined Tasks in the Language Industry.” Paper presented at the 10th European Society for Translation Studies Congress. Oslo, Denmark, June 2022.

- Bolaños-Medina, A. 2016. “Translation Psychology within the Framework of Translation Studies: New Research Perspectives.” In From the Lab to the Classroom and Back Again: Perspectives on Translation and Interpreting Training, edited by C. M. De León and V. González-Ruiz, 59–99. Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang.

- British Educational Research Association. 2018. “Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research.” Accessed August 6, 2023. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018-online.

- Buysschaert, J., M. Fernandez-Parra, and G. van Egdom. 2017. “Professionalising the Curriculum and Increasing Employability Through Authentic Experiential Learning: The Cases of INSTB.” Current Trends in Translation Teaching and Learning-E (CTTL-E) 4 (1): 78–111. http://www.cttl.org/uploads/5/2/4/3/5243866/cttl_e_2017_3.pdf.

- Campo, M., S. Laborde, and E. Mosley. 2016. “Emotional Intelligence Training in Team Sports.” Journal of Individual Differences 37 (3): 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000201.

- Courtney, J., and M. Phelan. 2019. “Translators’ Experiences of Occupational Stress and Job Satisfaction.” International Journal of Translation & Interpreting Research 11 (1): 100–113. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.111201.2019.a06.

- Dave, H. P., K. Keefer, S. W. Snetsinger, R. R. Holden, and J. D. A. Parker. 2021. “Stability and Change in Trait Emotional Intelligence in Emerging Adulthood: A Four-Year Population-Based Study.” Journal of Personality Assessment 103 (1): 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1693386.

- EMT. 2022. “Competence Framework 2022.” Accessed August 6, 2023. https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2022-11/emt_competence_fwk_2022_en.pdf.

- Fernando, M., M. D. Pietro, L. S. Alemeida, C. Ferrándiz, R. Bermejo, J. A. López-Pina, D. Hernández, et al. 2011. “Trait Emotional Intelligence and Academic Performance: Controlling for the Effects of IQ, Personality, and Self-Concept.” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 29 (2): 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282910374707.

- Fraser, J. 1996. “The Translator Investigated: Learning from Translation Process Analysis.” The Translator 2 (1): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.1996.10798964.

- Gökçen, E., A. Furnham, S. Mavroveli, and K. V. Petrides. 2014. “A Cross-Cultural Investigation of Trait Emotional Intelligence in Hong Kong and the UK.” Personality and Individual Differences 65:30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.053.

- Harzing, A.-W. 2006. “Response Styles in Cross-National Survey Research: A 26-Country Study.” International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management 6 (2): 243–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595806066332.

- Hodzic, S., J. Scharfen, P. Ripoll, H. Holling, and F. Zenasni. 2018. “How Efficient are Emotional Intelligence Trainings: A Meta-Analysis.” Emotion Review 10 (2): 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073917708613.

- Holmes, J. 1972/2000. “The Name and Nature of Translation Studies.” In The Translation Studies Reader, edited by L. Venuti, 172–185. London: Routledge.

- Hubscher-Davidson, S. 2018a. Translation and Emotion. A Psychological Perspective. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315720388.

- Hubscher-Davidson, S. 2018b. “Do Translation Professionals Need to Tolerate Ambiguity to Be Successful? A Study of the Links Between Tolerance of Ambiguity, Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction.” In Innovation and Expansion in Translation Process Research, edited by R. Jääskeläinen and I. Lacruz, 77–103. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/ata.18.05hub.

- Hubscher-Davidson, S. 2020. “The Psychology of Sustainability and Psychological Capital: New Lenses to Examine Wellbeing in the Translation Profession.” European Journal of Sustainable Development Research 4 (4): em0127.

- Hubscher-Davidson, S., and C. Lehr. 2021. Improving the Emotional Intelligence of Translators. A Roadmap for an Experimental Training Intervention. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88860-2.

- Jääskeläinen, R. 1999. Tapping the Process: An Explorative Study of the Cognitive and Affective Factors Involved in Translating. Joensuu: University of Joensuu.

- Kerremans, K., M. Fernandez-Parra, K. Konttinen, R. Loock. 2018. “Assessing Interpersonal Skills in Translator Training: The Cases of INSTB”. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Research into the Didactics of Translation, Barcelona, Spain, June 2018.

- Kiraly, D. 2013. “Towards a View of Translator Competence as an Emergent Phenomenon: Thinking Outside the Box(es) in Translator Education.” In New Prospects and Perspectives for Educating Language Mediators, edited by D. Kiraly, S. Hansen-Schirra, and K. Maksymski, 197–224. Tuebingen: Narr Verlag.

- Koskinen, K. 2020. Translation and Affect: Essays on Sticky Affects and Translational Affective Labour. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.152.

- Kotsou, I., M. Mikolajczak, A. Heeren, J. Grégoire, and C. Leys. 2019. “Improving Emotional Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Existing Work and Future Challenges.” Emotion Review 11 (2): 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073917735902.

- Laukkanen, J. 1996. “Affective and Attitudinal Factors in Translation Processes.” Target 8 (2): 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.8.2.04lau.

- Mikolajczak, M. 2009. “Going Beyond the Ability-Trait Debate: The Three-Level Model of Emotional Intelligence.” E-Journal of Applied Psychology 5 (2): 25–31. https://doi.org/10.7790/ejap.v5i2.175.

- Mpofu, E., B. A. Bracken, F. J. R. van de Vijver, and D. H. Saklofske. 2017. “Teaching About Intelligence, Concept Information, and Emotional Intelligence.” In Internationalizing the Teaching of Psychology, edited by G. J. Rich, U. P. Gielen, and H. Takooshian, 281–295, Charlotte, NC: IAP Information Age Publishing.

- Nelis, D., et al. 2011. “Increasing Emotional Competence Improves Psychological and Physical Well-Being, Social Relationships, and Employability.” Emotion 11 (2): 354–366.

- Nelis, D., J. Quoidback, M. Mikolajczak, and M. Hansenne. 2009. “Increasing Emotional Intelligence: (How) is It Possible?” Personality and Individual Differences 47 (1): 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.046.

- O’Brien, S., M. Ehrensberger-Dow, M. Connolly, and M. M. Hasler. 2017. “Irritating CAT Tool Features That Matter to Translators.” HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business 56 (56): 145–162. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v0i56.97229.

- Perdikaki, K., and N. Georgiou. 2022. “Permission to Emote: Developing Coping Techniques for Emotional Resilience in Subtitling.” In The Psychology of Translation, edited by S. Hubscher-Davidson and C. Lehr, 58–80. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140221-4.

- Petrides, K. V. 2009. “Psychometric Properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue).” In Assessing Emotional Intelligence, edited by J. Parker, D. Saklofske, and C. Stough, 85–102. Boston: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-88370-0_5

- Petrides, K. V. 2010. “Trait Emotional Intelligence Theory.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 3 (2): 136–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01213.x.

- Petrides, K. V. (2021). Trait Emotional Intelligence (TraitEi). https://traitei.com/trait

- Petrides, K. V. 2023. Trait Emotional Intelligence (Trait EI). https://teique.com/about/theory

- Petrides, K. V., N. Frederickson, and A. Furnham. 2004. “The Role of Trait Emotional Intelligence in Academic Performance and Deviant Behaviour at School.” Personality and Individual Differences 36 (2): 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00084-9.

- Petrides, K. V., L. Niven, and T. Mouskounti. 2006. “Trait Emotional Intelligence of Ballet Dancers and Musicians.” Psicothema 18 (supl): 101–107.

- Petrides, K. V., R. Pita, and F. Kokkinaki. 2007. “The Location of Trait Emotional Intelligence in Personality Factor Space.” British Journal of Psychology 98 (2): 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712606X120618.

- Risku, H., and D. Schlager. 2021. “Epistemologies of Translation Expertise.” In Contesting Epistemologies in Cognitive Translation and Interpreting Studies, edited by S. L. Halverson and Á. M. García, 11–31. New York: Routledge.

- Rojo López, A. M., P. Cifuentes Férez, L. Espín López, and J. Bhattacharya. 2021. “The Influence of Time Pressure on Translation trainees’ Performance: Testing the Relationship Between Self-Esteem, Salivary Cortisol and Subjective Stress Response.” Plos One 16 (9): e0257727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257727.

- Saldanha, G., and S. O’Brien. 2013. Research Methodologies in Translation Studies. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315760100.

- Schmitt, P. 2019. “Translation 4.0. Evolution, Revolution, Innovation or Disruption?” Lebende Sprachen 64 (2): 193–229. https://doi.org/10.1515/les-2019-0013.