ABSTRACT

The resiliency of literacy clinics was tested during 2020–2021, as many pivoted from in-person (F2F) to online or 3-way remote learning because of the COVID-19 pandemic. University-based literacy clinics advance teacher education, provide services to K-12 students who may need instructional support, and are a laboratory for research. The purpose of the study was to examine modifications in literacy instruction and assessment as a consequence of the changes in modality. Participants (n = 58) were literacy clinic directors/instructors from multiple states and countries. Data were analyzed in three phases: researchers individually coded; multiple teams cross-checked; a macro team collated across themes. Alterations during the pandemic involved place, time, types of texts, innovative instructional tools, and new ways of operationalizing literacy assessment and instruction. Some clinics used technology to transform instruction and innovate, while for others the goal was to replicate existing practices. Teachers, students in the context of their families, and teacher educators demonstrated resiliency, resourcefulness, and creativity in the face of interruptions and stress. Findings, viewed through the lens of the TPACK framework, can help us understand how transformations in instruction and assessment affect literacy learning not only in the context of clinics, but in school classrooms as well.

Worldwide, most educational institutions altered practices from traditional in-person (F2F) reading and writing instruction to remote scenarios during COVID-19 (Francom et al., Citation2021; Onyema et al., Citation2020). Remote refers to instructors and students being physically separated during instruction (Lindner et al., Citation2020). As faculty working at 17 different literacy clinic sites across the Americas and in close consultation with clinic directors at another 35 sites, we observed that most university-based literacy clinics also dramatically pivoted in response to the large-scale health threat of COVID-19.

In fact, we noticed that in 2020 most literacy clinics moved to 3-way remote, with K-12 students in their homes, clinicians in their homes, and the clinic director in their home/office. The change brought forth significant alterations to assessment and instruction practices. This study explored the transformational moment of institutional change as literacy clinics reacted to the pandemic and imagined a future based on new insights about teaching and learning.

Literacy clinics currently and historically are sites designed for the development of veteran or pre-service teachers (Bader & Wiesendanger, Citation1986; Laster, Citation2013). University-based literacy clinics are the manifestations of required clinical practica, which are significant components of a graduate degree in literacy education or of pre-service training of K-12 teachers. The teachers are called clinicians and provide assessments of students’ needs in reading and writing, design appropriate learning environments, and deliver specific literacy instruction for their assigned students (Deeney et al., Citation2011; Dozier & Deeney, Citation2013). In many but not all literacy clinics, young students advance their reading and writing within the context of their families (Deeney et al., Citation2019; Laster, Citation1999). According to Pletcher et al. (Citation2019)’s close examination of 10 literacy clinics, there are two levels of supported learning. The clinicians receive supervision and coaching from the clinic director as they perfect their skills in assessment and instruction. In turn, clinicians provide instruction for the young students in their identified areas of need, whether it is reading comprehension, fluency, or word recognition including phonemic and phonological awareness.

There is extant research on literacy clinics, including on the use of technology before the pandemic (Dubert & Laster, Citation2011; Laster et al., Citation2018; Ortlieb et al., Citation2014; Rhodes, Citation2013; Vasinda et al., Citation2015). However, there is a dearth of research about online clinic environments, with a few exceptions that do not incorporate what occurred during the pandemic (Lilienthal, Citation2014; Vokatis, Citation2017, Citation2018). Heflich and Smith (Citation2012), for example, describe how they exchanged their F2F university-based literacy clinic with school-based clinical experiences (supervised by school personnel rather than clinical faculty) when transforming their program to fully online.

As researchers and literacy clinic faculty, we were interested in how the changes in modality caused by the pandemic impacted strategies for literacy assessment and instruction. We wondered whether transferring F2F practices to 3-way remote environments was practical and productive. We wondered what major changes occurred spurred on by the pandemic-induced alterations, and if any would remain post-pandemic. Therefore, we surveyed and analyzed data from multiple literacy clinic sites to identify what occurred during the pandemic. Literacy clinic directors were also responsive to questions asking about their visions for the future of literacy clinics.

Theoretical frameworks/background literature

In this section, we describe existing research on literacy clinic and connect that to several theoretical foundations, social constructivism and social constructionism. Then, we delve deeper into contemporary theoretical models of reading and writing, which undergird the types of literacy assessment and instruction found in many literacy clinics. Emerging from these foundational pillars, we summarize some of the essential practices common across literacy clinics, whether they are F2F or in virtual spaces. Among others, these include parallel layers of learning by educators and students, teacher-student relationships that spark learning engagement, and instruction informed by ongoing assessments. Interwoven is a discussion of the growth of the use of technology in clinics, particularly online presence, and teachers’ skills in using technology for literacy instruction.

Literacy clinic research

Researchers have examined literacy clinic structure (Coffee et al., Citation2013; Evensen, Citation1999), such as expectations of clinicians’ lesson plans and instruction, as well as logistics including recruitment of young students. Another strand of research looked at the transference of what clinicians learn in literacy clinic practica to their classrooms (Deeney et al., Citation2011). A recent interview study examined teacher efficacy in assessment and instruction (Pletcher et al., Citation2019). Interestingly, researchers have also focused on the use of technology in pre-pandemic clinics, such as the use of tablets and apps (Laster et al., Citation2018, Citation2016; Vasinda et al., Citation2015). Use of video recordings (Bowers et al., Citation2017) Was shown to assist clinicians as they reflected on their instruction. In an earlier article (Dubert & Laster, Citation2011), literacy clinics were described as technology training sites for teachers, with a warning to use technology for powerful assessment and instruction, rather than as drill-and-practice tools. Thus, this study is an extension of previous perspectives on literacy clinics’ function and use of technology, but with the added twist of what happened when they were propelled into the pandemic era.

Social constructivism: individually tailored instruction

Although there is collaboration between clinician and student in clinic, Dewey’s (Citation1902/1990) constructivist learning theory is a helpful foundation in that it focuses on self-actualization and growth of the individual. Clinics vary in modes of operation, though most utilize one-on-one or small group instruction (Bader & Wiesendanger, Citation1986), which allows for deepened individualized growth. These smaller teacher-student configurations have shown to be more effective in terms of student gains (Ortlieb & McDowell, Citation2016), but also in terms of teachers’ understanding of literacy theory and practice (Hoffman et al., Citation2019). Spending more time with a smaller group of students allows preservice (and inservice) teachers to strengthen their relationships with students and promote engagement and self-directed learning. Such designs allow students to develop more autonomy and self-awareness (Codling, Citation2013), which can enhance learning. Instruction is constantly informed by various forms of individual assessment and builds on a student’s cultural and linguistic contexts (Hoffman et al., Citation2019). A recent survey of literacy clinics revealed that reading material is selected based on student needs and interests, and consists mainly of trade books (Pletcher et al., Citation2019).

Theory of social constructionism

Another theoretical foundation of literacy clinic research is social constructionism, which is related to but distinct from Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) social constructivism (a cognitive description of a learner’s trajectory). Instead of a focus on an individual’s cognitive development, social constructionism examines how learning happens with engagement in social contexts (Hruby, Citation2001; Tharp & Gallimore, Citation1988). Gergen (Citation1985) explained, “From the constructionist position the process of understanding is not automatically driven by forces of nature, but is the result of active, cooperative enterprise of persons in relationship” (p. 267). The cooperative and collaborative enterprise in literacy clinics is the learning environment established by teacher educators, teachers, students, and families. In these dynamic spaces of interaction, there are multiple layers of simultaneous learning among educators, students, and families (Dozier et al., Citation2006).

Schools, on the other hand, are organized bureaucratically into chains of authority (Tharp & Gallimore, Citation1988), which often interfere with teachers’ agency to teach. In literacy clinics, though, power structures are less pronounced, and it is common for the supervisor, clinicians, and families to work together. Through a social constructionist lens, a supervisor’s role becomes that of assisting performance in collaboration (Tharp & Gallimore, Citation1988), rather than that of an authoritarian working in a hierarchical structure. In fact, many clinics provide a platform for learning the skills of collaborative professional development toward the role of becoming literacy coaches (Laster & Finkelstein, Citation2016; Msengi & Laster, Citation2022). Thus, the social constructionist perspective is an apt lens through which literacy clinics can be explored.

Theories of literacy processes

Adding a contemporary lens, the Active View of Reading theoretical framework aligns with the ways in which instruction and assessment are viewed in this study (Duke & Cartwright, Citation2021) and in literacy clinics (Laster et al., Citation2021). In the Active View of Reading, Duke and Cartwright (Citation2021) posit that reading development requires more than decoding and language comprehension, which are the two larger components defined in the traditional Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, Citation1986). Duke and Cartwright (Citation2021) identify processes such as print and vocabulary knowledge, fluency, morphological awareness, and grapho-phonological semantic cognitive flexibility, which explain reading ability across and beyond word recognition and language comprehension. Evidence also shows that there is a considerable overlap between word recognition and language comprehension, which can explain the shared variance of these two components in reading ability. The Active View of Reading also draws attention to self-regulation and other executive function skills that affect reading development, and which explain the role of motivation, engagement, cognitive flexibility, and strategy use in reading comprehension. This approach views readers as active meaning makers who can rely on various reading subprocesses and cognitive tools to engage with text and understand it deeply. Instruction and assessment that considers these components beyond decoding and language comprehension have proven effective in promoting reading improvement (e.g., Cabell & Hwang, Citation2020; Lonigan et al., Citation2018).

Two theories that support current views of writing are sociocultural and sociocognitive. Sociocultural research on writing has examined co-writing, how reading and talking mediate writing, writing as a mode of social interaction, and understanding how culture shapes writing (Bazerman, Citation2016). Sociocognitive theories of writing, on the other hand, focus mainly on the mental processes that writers undertake (Flower & Hayes, Citation1994; Citation1986). The sociocognitive theory of writing has served as a backbone to writing instruction. In this model there are three key components: the task environment (external elements that influence our writing), the cognitive processes involved in the act of writing (including planning, organizing, and revising), and the writer’s long-term memory, which includes one’s topic knowledge and understanding of the audience. Over the years, this model has been adapted to include motivational (Graham, Citation2006), self-regulatory (Zimmerman & Risemberg, Citation1997), and rhetorical aspects (Bereiter & Scardamalia, Citation1987), and has consistently remained a theoretical lens to understand how writers engage in text creation. Research using this model revealed that writing is a goal-directed process (MacArthur & Graham, Citation2016), that writing involves the articulation of complex mental operations, and, more recently, how cognitive processes differ across novice and more expert writers.

Research on students’ writing during the COVID-19 pandemic is emerging. In a quantitative study in Norway, Skar et al. (Citation2021) measured 2,453 first grade students’ writing fluency, handwriting, and attitudes about writing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, the researchers reported statistically significant differences (losses) in writing fluency and handwriting, and less significant differences in attitudes about writing.

Technology in literacy learning

Understanding how technology facilitates learning is crucial, but it is also necessary for teachers to develop a critical outlook as to what constitutes robust, evidence-based resources and pedagogy. One lens to view technological practices in literacy teaching/learning is the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge model (TPACK) established by Mishra and Koehler (Citation2006). They identified an additional domain of teacher knowledge, Technological Knowledge and integrated it with Shulman’s (Citation1986) Pedagogical Content Knowledge developing a more contemporary and comprehensive model of teacher knowledge. In the context of literacy in general, TPACK includes the ability to use digital tools to support and extend literacy learning opportunities, as well as when and where to best leverage those tools and platforms.

The incorporation of technology in literacy assessment and instruction has increased in the last decade, but it has also signaled the presence of challenges in literacy clinics and elsewhere. One concern is whether technology is used in powerful ways, such as supporting students’ generative learning (Tysseling & Laster, Citation2013). Virtual instruction challenged clinicians’ TPACK in terms of considering new instructional strategies and tools, managing distractions, and finding reading materials for online teaching (Deeney et al., Citation2020; Vasinda et al., Citation2020). They had to consider changes in instruction for virtual formats. For example, in contrast to print texts which are tangible, linear, and in a fixed format, online texts require different navigation skills (Coiro, Citation2021). Not only are there a range of types of texts (e.g., hypertext), types of readers, and types of reading activities, but also there are many kinds of contexts for digital reading. Earlier, Kymes (Citation2005) expressed concern that teachers may show their students how to navigate the web, but do not generally teach their students explicitly how to process information selection, assess the quality of the content, or think metacognitively while reading online.

During the abrupt pandemic pivot to remote learning, there were additional challenges and affordances of technology usage. On the one hand, the shift to online assessment and instruction meant that students from remote areas without the means to physically attend a clinic could now engage in tutoring virtually (Laster et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, the inequities of the digital divide caused by lack of access to devices or connectivity (Kalyanpur & Kirmani, Citation2005; Lohnes-Watulak & Laster, Citation2016) were exacerbated during the pandemic (Ravitch, Citation2020), especially for marginalized populations (National Academy of Education, Citation2020). This can lead to educational decline as more privileged students have devices and technological access while those who are marginalized do not (Onyema et al., Citation2020).

Finally, online presence (Lehman & Conceição, Citation2010) is rightly a growing topic of research. Emerging from what we know about intrinsic motivation (Cambria & Guthrie, Citation2010; Marinak & Gambrell, Citation2013), careful examination of the learning that occurs in online spaces must include understanding of teacher-student engagement, also known as online presence. This links to the research that has established that engagement affects reading comprehension (Liebfreund, Citation2021).

In this section, we described the salient theoretical frameworks we reflected upon as we analyzed survey responses: social constructivism (Vygotsky, Citation1978), social constructionism (Gergen (Citation1985), the Active View of Reading (Duke & Cartwright, Citation2021), and theoretical frameworks for writing instruction. Equally important, we have described the technological lenses we looked through: the TPACK framework (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006), online presence (Lehman & Conceição, Citation2010), concerns about digital divides, and the complexities of online for literacy learning (Coiro, Citation2021). These lenses allowed us to identify key themes in the survey responses. We organized our analysis around two research questions: How did the pandemic impact reading assessment and instruction in literacy clinics? and How did the pandemic impact writing assessment and instruction in literacy clinics?

Methodology

In this section we first describe the participants, then the survey instrument, including how it was developed, and shared. In the last section, we report in detail our processes of data analyses.

Participants

After IRB approval of this exempt study, we began recruitment and survey delivery in two stages. During the first stage, each member of the team electronically sent out surveys to literacy clinic directors and educators whom they knew. Surveys were sent to literacy clinic directors and instructors in 40 U.S. states, Canada, Brazil, Colombia, and Australia. In all, 73 surveys were initially distributed, and 43 responded, for a 59% response rate. It is important to note that the survey responses were anonymous, and no identifying data were collected.

For the second stage of survey distribution, two months after the first survey, we employed multi-stage sampling (Fowler, Citation1993) and reached out to major literacy associations (i.e., Literacy Research Association, International Literacy Association, and Association of Literacy Educators and Researchers) to seek out more participants. Consequently, we received 15 additional survey responses. Taken together, 58 completed surveys were received.

The research team chose to define the literacy clinic supervisors and instructors who responded to the survey as literacy clinic directors. Interestingly, some of the participants indicated that they filled several positions in literacy clinics (e.g., administrators, clinician supervisors, coaches, and instructors). In a like manner, we chose to describe the graduate or undergraduate students enrolled in literacy clinic courses as clinicians. Of the 58 literacy clinics described by survey respondents, data revealed that of the clinicians 62.7% were graduate students/practicing teachers, 22% were pre-service graduate students, and 40.7% were undergraduate students.

Survey procedures

For this research, we adapted a researcher-designed (Fowler, Citation1993) survey instrument. That is, the first author developed a first draft of the survey about changes in literacy clinics from pre-pandemic to emergency instruction. The survey was then reviewed, revised, and edited by the other researchers, culminating in a final draft (Appendix).

The researchers employed this survey to gather information about all aspects of literacy clinics. Data were gathered about the roles of the participants, descriptions of literacy clinics pre- and during the pandemic (e.g., assessment and instruction, teaching spaces), descriptions of learners (e.g., undergraduates, graduate students), and technologies utilized both before and during the pandemic. Additionally, the participants answered open-ended questions about the affordances and constraints that the pandemic pivot brought to their literacy clinics. Questions focused on literacy clinics’ changes (e.g., recruitment of students, instructional delivery, online assessment, online supervision and coaching). Importantly, participants were asked about the clinic changes that were sustainable and worth keeping, and a final section was provided for any additional information that the participants wanted to share. The survey was open for a period of 11 weeks. At that time, the researchers downloaded the data for analytical coding.

Data analysis

We analyzed the data guided by qualitative protocols (Creswell, Citation2013). The research team developed a collaborative spreadsheet on which each survey respondent had a unique identifying number and survey responses were entered in cells across each row. The data analysis included initial coding of data (Saldaña, Citation2021). Additionally, definitions, categories, and themes were developed across participants’ responses.

Phase I: coding

The research team members were first placed in teams of two and assigned specific survey questions that addressed the a priori topics of demographics/logistics; planning, technology, assessment of writing, assessment of reading, instruction of reading, instruction of writing, parents, student gains, and online supervision. (Some of these topics are discussed in companion articles.)

Employing initial coding (Saldaña, Citation2021), we gleaned information about the affordances, constraints, and lessons learned from literacy clinic directors. The research teams analyzed the open-ended survey questions employing Charmaz’s (Citation2007) coding protocol: researchers read each response, coding one line at a time, noting and highlighting significant words or phrases, and assigning in vivo codes that incorporated the important words and phrases. Concomitantly, researchers crafted reflexive and analytic memos, and noted any connections made to previous research. Throughout this process, researchers noted connections between themes, categories, and codes. Research teams met often to resolve any differences in coding results. Lastly, another two-researcher team met to analyze the data for missing codes and categories, continuing to compose reflexive and analytic memos. Specifically, all work was color-coded so that the research team could note the stages of data analysis while reviewing the data.

Phase II: categories and definitions

Once the coding was completed, the researchers began a second phase of data analysis. In other words, a new document was created for the purpose of searching for collections of similar categories. Employing color-coding, teams of researchers looked for patterns as they refined their list of potential categories. For example, Question 10 focused on the effects of the pandemic on reading instruction, asking survey respondents to provide details. As a result of searching for patterns in Question 10, five themes emerged: Time, Digital Tools, Engagement, Technology, and Content. Additionally, research teams searched for the significance of each determined category by counting the frequency that the category surfaced in the data. Research teams devised category definitions, providing significant direct quotations from survey respondents to illustrate the definitions.

Lastly, research teams met to discuss and reach consensus regarding their coding, reflexive and analytic memos, category creating, and definition analysis. Upon completion of these important discussions, the teams composed narrative summaries, and the summaries were incorporated into the findings.

Phase III

Three researchers examined all the coding holistically. They determined larger themes, and derived profiles of clusters of literacy clinics. These results are reported in a separate article.

Findings

The following section describes the main findings of the study. We first describe and explain assessment and instruction findings for reading. Next, we focus on writing results, both assessment and instruction. Finally, we capture some of the themes from the data about the educators and the environment; these include time, learner engagement, transitioning to remote, and resiliency.

Reading

Our first research question was How did the pandemic impact reading assessment and instruction in literacy clinics? The results of our data analysis revealed several major themes, which are described in detail below. While all respondents had to shift current assessment and instruction practices out of necessity, some shifts were viewed as affordances, while others were viewed as constraints.

Assessment

In considering the impact of the pandemic on reading assessment, some literacy clinic respondents described alterations in the assessment tools used. Others explained the process of assessment during the pandemic and how that was different from their usual clinic practices. Additionally, reliability and validity were questionable for some respondents.

Tools

Most respondents discussed changes in how reading assessments were administered via an online format. The types of and specific assessments used were affected in different ways. Being able to access the online version of some commercial assessments provided some clinicians with tools they were familiar with, which facilitated the process of collecting data about students’ strengths and needs. The Qualitative Reading Inventory (QRI; Leslie & Caldwell, Citation2017) was available for online use, but mostly not the Developmental Reading Assessment (Beaver & Carter, Citation2019). Four respondents (7%) said they continued to use running records as an assessment tool, because they were free, and clinicians were familiar with it. On the other hand, three respondents (5%) said using informal reading inventories was particularly challenging.

During the spring 2020 quick pivot, it was unclear who would make assessments available online: clinic supervisors or clinicians. Many sought online commercial materials. Some barriers identified by these respondents were the cost of online assessments and copyright permission difficulties. Finding resources for assessment ended up not just being a challenge but also an affordance as clinicians were stretched to creatively problem-solve new assessment pathways.

Process

Those who attempted to adapt assessments to an online format detailed strategies for doing so, including screen sharing, converting paper forms to digital formats by scanning and uploading, and using e-texts where available. These adaptations required additional time, preparation, and resources on the part of the clinicians and/or clinic directors. Respondents often administered fewer or different assessments or dropped assessments that they were not able to administer in an online format. A few respondents described affordances of online assessments such as the flexibility and creativity of clinicians in identifying various online resources, and some stated that their assessment of reading had not changed much during the pandemic.

Reliability and validity

One recurring theme was the issue of the reliability and validity of assessment results when administered online. Inconsistent administration and parental intervention may have affected the assessment results, according to five respondents (9%). Respondent #51 explained:

Conducting informal reading inventories was very challenging, as those materials aren’t readily shared virtually with students. Teachers were creative in the ways they made IRI materials available to the student clients. For two clients, the parents were present during assessment sessions and parents interjected with anecdotes and information, as well as to redirect student behavior. This may have impacted assessment results somewhat.

Difficulty with student attention and engagement, and the inability to assess physical movement (e.g., eye tracking, finger-pointing) may have contributed to a lack of reliability. Eighteen (31%) respondents also described technical difficulties (e.g., audio quality or strength of Internet connection) as a challenge that potentially impacted reliability.

Instruction

There were many shifts in reading instruction as a result of the pandemic. We report on four major areas that arose from the data: (a) time, (b) instructional resources and strategies, (c) shifting to digital tools, and (d) student engagement.

Time

Time was mentioned often when respondents described the ways in which reading instruction was affected by the pandemic. Responses showed an intersection between an impact on planning time, as well as actual teaching time. Instructional time was reduced due to family schedules, digital fatigue, or simply because it took longer to accomplish tasks done faster in a F2F experience. Tutoring sessions also slowed down because of connectivity issues; for example, having to wait for websites or materials to download. Similarly, clinicians had to devote time to learning how to use digital tools, sharing screens, or displaying content online. Clinicians also needed to spend more time looking for resources and adjusting to their lesson plans. Finally, respondents mentioned time in relation to the volume of reading texts when they compare F2F versus online instruction. Some commented that students spent less time actually reading books when tutoring was online. Twenty-five (43%) respondents commented that, although reading instruction did not change, it was impossible to get the same amount of work accomplished in the online format.

Instructional resources and strategies

In line with this, eight (14%) respondents mentioned that it was easier to find activities that targeted decoding aspects of reading (e.g., phonemic awareness, letter-sound relationships, word reading). Ten respondents (17%) mentioned that it seemed as though comprehension strategies and some reading behaviors were harder to model in an online format. Yet, clinicians found ways to adapt, such as with a digital highlighter instead of tracking text with finger.

One theme that clearly stood out was the strategies and changes made to accommodate instruction in an online learning environment. Forty-seven percent of respondents said that there was less instructional flexibility in methods, materials, and activities. Respondent #59 reported that “The pandemic impacted the materials that were used for instruction, and this was extremely challenging. We use several manipulatives and resources that were not able to be used during the pandemic because of the potential of COVID contamination.” (We now know that COVID is an airborne virus.)

In considering how reading instruction was affected because of the pandemic, thirteen (22%) respondents identified finding digital texts as a primary need. More specifically, they procured interactive, digital tools: for example, Jamboard, Pear Deck, and Google Slides. In transitioning their reading instruction to online, respondents named sources such as Reading A-Z and Epic! as being instrumental in meeting their needs. In order for the use of digital texts to be successful, the clinician had to screen share and utilize available digital teaching tools, such as text highlighting. Also, students had to adapt to reading on a device. Some teachers curated libraries of e-books to offer students a selection of texts at an appropriate level of reading and interest. There was a sense that there were many resources, but it just took time to locate them and learn how to use them. In some cases, the clinic supervisors took the lead in procuring digital texts and tools; and, in other cases, the clinicians took this responsibility. For example, Respondent #13 stated, “There was a learning curve involved in finding and effectively using digital tools. I started by sharing a Wakelet of good resources I researched ahead of time. Then I created collaborative spaces for sharing teacher resources. My teachers took it and ran. I ended up actually learning so much from them!.”

Shifting to digital tools

Some respondents sought to replicate current practices into an online format, whereas others used the technology to transform their practices. For example, to replicate existing reading practices, Respondent #5 noted:

While tutors used texts to read for children on the screen, they used tools available on these platforms to guide children during reading. For instance, if someone used the Reading A-Z texts, these texts could be projected, and tutors can use highlighting tools. As a result, tutors’ guidance and language was influenced by the availability of certain tools.

Transformative practices, on the other hand, emerged among some clinics. Respondent #28 shared the following examples of their thought process: “Collectively had to think through how to best use technological texts and tools to transform instruction as opposed to using tools for the sake of using tools.” Respondent #30 mentioned strategy modeling as one of the major challenges of online tutoring, so clinicians had to find innovative ways to model reading behaviors. For example, a digital highlighter could assist in modeling inferential comprehension. Or, to help students with word identification, clinicians could model chunking a word into manageable parts using a digital pen.

One aspect of both assessment and instruction was how the use of technology enhanced or detracted from the core purposes of the literacy clinic. Many discovered new ways to strengthen instruction, though it took time to learn new tools. They procured interactive, digital tools: for example, Jamboard, Pear Deck, and Google Slides. Even if the supervisors had a very high bar to meet for learning new technology, in many cases the clinicians were quick to learn, very creative, and collaborative. A report from one literacy clinic noted that teachers

… were creative in how they used technology … A key feature was using interactive sites like Google Slides or allowing students to control the [teacher’s] computer via Zoom. These allowed for interaction in digital spaces … . [Teachers] became comfortable with these tools and gained confidence in how they could design online instruction … (Respondent #56).

Engaging learners

Many respondents noted that reading instruction was impacted by challenges in sustaining learners’ attention when online, and that this affected learners’ progress in reading proficiency. Respondent #8 expressed that “it was more difficult to engage students because of distractions at home … . It seemed less engaging to have virtual word sorts and hunts vs. books or cards in hand.” Although many reported that virtual activities were less engaging than having hands-on materials, some respondents found digital game-like activities to be effective for motivating students. Age also emerged as a factor, with younger children being much more difficult to engage. Respondents reported that young children were quieter and more reserved online and less willing to share and participate. As a result, some teachers found it more difficult to connect with students on a social-emotional level and establish a trusting social presence. Thus, student behaviors, and, particularly, engagement, were largely viewed as negatively impacting literacy learning when literacy clinics went to a remote modality. Respondent #11 summed up some of these concerns:

Most frustrating were the limitations of technology and the constraints on the types of instructional tasks and texts that we could use. The teaching is much more one-dimensional … teachers found it difficult to maintain some children’s focus … . There were frequent interruptions from other family members, distractions from television or other conversations in the background, etc. Some literacy clinic personnel reported great frustration with the interruptions to instruction. One respondent remarked:

Loud noises/disruptions, etc. were also BIG frustrations when tutoring over ZOOM. Also, behavior disruptions – many children/students displayed tricky behaviors (run into the next room to ‘find’ something, pretending they couldn’t hear or see their tutor, physically shutting the computer off when they didn’t want to be in tutoring) were all challenges. (#42)

Additionally, Respondent #25 noted a specific technological hindrance: “some very young kids have difficulty accessing materials or using things like keyboards, if they have not learned letters and sounds yet. So, it is limiting for very young children.” This theme will be carried into the analysis of data about writing.

Writing

Our second research question was, How did the pandemic impact writing assessment and instruction in literacy clinics? Like assessment of reading, writing assessment was affected both in terms of product and process. Second, writing instruction had both obstacles and breakthroughs. Some teachers found the shift challenging because they could not engage in side-by-side teaching, and they had to adapt methods and materials. However, some teachers embraced the change and employed new and creative methods for writing instruction.

Assessment

The challenges of writing assessment in an online environment forced clinic professionals to consider multiple aspects of the assessment of writing: Data on the process that the student engages in to write, and the writing product itself. The former was most difficult to capture, whereas the latter was possible with simple modifications.

Process

Assessing the writing process online requires adaptation. Observing the act of a student writing was different from the F2F context. Sometimes writing took place outside of the tutoring session and then only the product could be assessed. Respondent #1 concluded: “It was very difficult to assess the PROCESS of writing; only the product was available.”

Technology, or at least distance, was a barrier for accessing the process of writing for some students. For younger students, still refining their fine motor and keyboarding skills, having to use technology for writing made assessment challenging. As Respondent #30 observed, “Writing assessments were greatly affected, especially spelling assessments and printing (fine motor) assessments. For sentence/paragraph writing, most clients typed (if they had keyboarding skills) or tutors scribed from an oral response.” The online platform presented other challenges, too. Issues such as connectivity, clarity, or the apps or programs needed to assess writing process often caused disruption. In an online tutoring environment, it also tended to take more time to accomplish learning objectives.

Product

Some clinics used techniques such as utilizing the video platform chat boxes or holding up writing to the camera for the teacher/tutor to assess the finished product. Many described how family members actively took scans or photos of writing samples and emailed or texted these to the clinic. There was a range of summative statements such that some clinics did not alter their writing assessment methods, others did less writing then prior to the pandemic, and some opted to forgo writing assessment altogether. Many of the responses described the inherent challenges that became limitations in attempting to assess writing in an online learning environment.

There were a few responses related to the effective use of digital tools and devices that made writing assessment possible, such as shared Google Documents or taking scans of writing samples. As Respondent #33 said, “Tutees instant messaged, texted writing samples. They held writing samples up; so tutors could see and screen shot their samples virtually. Parents were contacted and asked to photograph and email or text writing samples.”

In some cases, the clinic director and the clinicians had to adapt to implement even modified writing assessments. The educators became problem solvers thinking of ways to complete the assessments. They also acted as facilitators between the family and the students to obtain the writing assessment components that they needed. As Respondent #31 stated, “this was challenging and different but teachers made it work.” This final statement speaks to the tenacity and flexibility needed for writing assessment.

Instruction

Though challenging, teachers who persisted found creative ways to adapt. Respondents noted that teachers became more proficient with digital tools and that effective instruction was possible as they taught mini-lessons, modeled writing, provided guided practice, and supported inquiry projects. Overall, responses ranged from “Writing instruction was not impacted too much … ” to “Writing instruction was by far the biggest casualty of the clinic moving online.” Of 52 responses, 25 (48%) identified challenges and difficulties to online tutoring ranging from small adjustments to abandoning writing instruction (3 respondents) or reducing time spent engaging in it.

Categories of challenges included the inability to observe the writing process in “side-by-side instruction” and difficulties of students sharing writing samples with the clinicians. Some challenges related to logistics of how to use new tools, students’ difficulty with keyboarding fluency, and instructional time lost to explaining and demonstrating the use of new tools.

Transitioning to remote

The challenge of sharing writing samples between students and clinicians resulted in engaging parents as partners. Although the students who used paper and pencil held their writing up to the camera, teachers wanted and needed the samples for further examination. Enlisting the parents or caregivers to scan or photograph the writing sample and send them via text or e-mail engaged them as partners in the remote learning. Working with young and emergent writers was noted as especially challenging: “For emergent writers, writing instruction in an online setting was particularly tricky. Without sitting next to the child, it was difficult to find ways to engage them/redirect them/scaffold them in meaningful ways” (#19). In some homes, students did not have writing materials that the clinics provide during F2F sessions, so some clinicians delivered supplies (e.g., paper, pens) to homes when possible.

Although almost half of the respondents recounted difficulties and challenges, almost as many related evidence of teachers and students adapting to new contexts with shifts, changes, flexibility, and creativity using the Zoom chat feature, interactive Google Docs or Slides.

Some of the tutors used iPad apps and their computers in tandem for kids who also had both. Some turned over control of the screen to their intermediate kids and used Google Docs. Others just had the kids hold up their papers or parents took a photo and sent it to the tutor. (#50)

Although the use of screens could benefit the writers, there were still challenges. Some respondents identified approaches that were challenging to implement online, such as shared and interactive writing; others found the transition relatively easy.

Writing instruction was not impacted too much, as modeling, and guided practice could be accomplished on the screen, and children could still write using paper-pencil or keyboard, depending on their preference. However, we did have to interrupt writers at times to have them share their writing so far, rather than being able to “look over their shoulder” so to speak. This may have interrupted thought processes. (#26)

Pivoting and resiliency

Across both research questions, there was overall evidence that many clinic educators were resilient, creative, and collaborative. An optimistic perspective came from Respondent #2: “The hopeful aspects are that we recognize that we have more options with respect to delivering clinic instruction that should help the clinicians provide consistent, effective instruction.” Stated respondent #8, “My candidates [teachers] and their students are resilient. I am hopeful for the future of education because these candidates adjusted so well to a new teaching normal.” Some respondents noted that the collaboration among the clinicians and the leadership that they displayed were remarkable. Respondent #33 said, “I was uplifted at how resourceful and resilient the tutees were and how well they transitioned. I was uplifted at the gains I saw with tutors and tutees.” Clearly, there were a range of insights about how educators and students pivoted in flexible ways during the pandemic.

Furthermore, the pandemic-induced shifts have driven many of us to consider changes in what has been traditional literacy assessment and instruction. One respondent (#18) articulated the point:

… potential to create joyful, liberating accelerative literacy instruction in online settings … For too many students who experience reading and writing difficulties, literacy instruction is reductionist. These children and youth need new opportunities to see themselves as part of a ‘literacy community’ and their proficiency with digital tools can provide them with this bridge … we have an opportunity as a literacy clinic community to not just transfer print literacies to online environments (although, of course, part of that is necessary) but to rethink what counts as educational literacies and for whom. There are opportunities of connecting teachers and students from around the country and world – helping students to see both the word and the world that is possible with a liberatory literacy education.

Discussion

Key topics from the findings are discussed in this section in conjunction with others’ research and theoretical frameworks. Guiding our understanding of the findings were our research questions: How did the pandemic impact reading assessment and instruction in literacy clinics? and How did the pandemic impact writing assessment and instruction in literacy clinics?

In the discussion, we first use the foundations of social constructionism and the subset of resiliency to view key aspects of the data, such as digital tools. Second, we examine the teachers’ multifaceted skills within the frame of TPACK (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006). Third, robust collaboration among many layers of learners in literacy clinics spotlights the importance of engagement and online presence. Finally, the issue of inclusivity gives the broadest lens.

The social constructionist perspective is a valuable lens through which literacy clinics’ altered contexts can be viewed. During the pandemic period, in contrast to pre-pandemic literacy clinics, clinicians showed up virtually in multiple people’s homes, and these novel social contexts had significant impacts. For example, parents interrupted instruction in some cases; in other cases, parents re-directed their children to engage in the learning. For writing assessment and instruction, parents stepped in as essential helpers. The learning environment was not automatic, but the result of clinic personnel and families in active, cooperative relationships.

Other evidence of social constructionism were the collaborations between clinic directors and clinicians. There was dynamic and reciprocal learning about technology to support both assessment and instruction of literacy. Clinicians taught teacher educators, and vice versa. Furthermore, respondents talked about how clinicians communicated and assisted each other. They pooled resources, sharing instructional ideas, as well as digital assessments and materials. Thus, the many layers of learning – of the clinicians and of the students, but also of parents and teacher educators – evolved and progressed by way of communication and collaborations.

Additionally, the Active View of Reading (Duke & Cartwright, Citation2021), which is rooted in social constructionism, was a beneficial perspective in extrapolating survey findings. The survey results imply elements of this contemporary theoretical framework in respondents’ descriptions of the nuanced complexities of their new learning environment, including motivation and engagement, executive functions (e.g., focus, attention), and strategy use. Evidence of the Active View of Reading includes instructional adaptations made to extend engagement into the online space, such as student interactions using digital tools. Among the findings, there were also descriptions of how clinicians engaged students in learning through game-like activities and quality children’s literature.

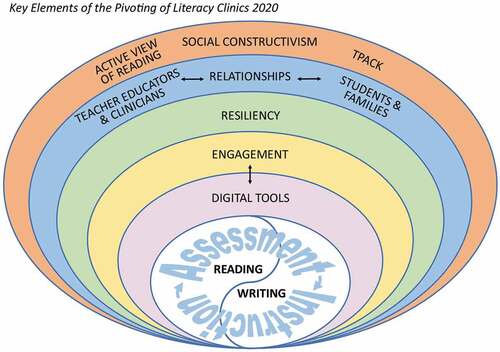

In addressing our second research question, we note that writing instruction, specifically teaching the writing process (D. Graves, Citation1994; D. H. Graves, Citation1983), was another challenge as clinics pivoted. Students’ independent practice was seldom implemented in the tutoring sessions, and often teaching of the writing process did not occur. Drawing from Flower & Hayes’ (Citation1984) sociocognitive theory of writing, students did not have opportunities to properly consider the task environment, an important component of the model. Bromley et al. (Citation2015) indicate that assessment of writing includes teacher-student conferences, as well as rubrics and portfolios; our findings showed no evidence of these assessment strategies. Remote clinics faced major difficulties when young children tried to use digital tools for writing; specifically, there was intermittent connectivity and teachers’ lacked access to students’ actual writing process. illustrates the contexts and interactions between and among persons, activities, and phenomena shown in the Findings and discussed in the Discussion section.

Despite pandemic-related challenges, respondents remarked on the flexibility and resiliency of all participants in the literacy clinics. We know from Drew and Sosnowski’s (Citation2019, p. 492) model of resiliency that “Resilient teachers embrace uncertainty, reframing negative experiences into learning experiences. Reframing helps teachers retain power, not cede it to situations, which helps balance constraining and enabling factors.” Our findings support this description of literacy clinic professionals. Furthermore, Drew and Sosnowski say that relationships with colleagues and students are key to enduring and prevailing when faced with challenges. Clinicians were eager to learn of new ways to communicate, assess student learning, effectively instruct their students, and coach colleagues. As respondent #31 stated,

“teachers did a wonderful job of being flexible and resourceful in identifying tools for engagement and instruction.”

Resiliency showed up during the pivots required by the pandemic for many clinicians as they began or continued to integrate technology. At the same time, the supervisors, too, had to integrate content and pedagogical knowledge with new technological tools. The spectrum of survey responses conveying the challenges and opportunities of online instruction could be mapped on to educators’ proficiencies of Technological, Pedagogical, and Content knowledge, or TPACK (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006). During the pandemic, the need for strong TPACK was thrust into the spotlight.

Our findings build on the work of Secoy and Sigler (Citation2019), who found that teachers can retain the integrity of their traditional literacy instruction while moving some instructional components to digital spaces. TPACK (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006) aids us in describing the range of integrated actions of educators in literacy clinics. Before the pandemic, clinicians were primed to spotlight how best to teach the processes of proficient reading and writing, demonstrating Pedagogical Content Knowledge, or PCK (Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006; Shulman, Citation1986). For Technological Content Knowledge (TCK), another intersection of TPACK, clinicians combined technology with reading and writing content. The clinicians located templates, apps, or websites that addressed specific literacy needs of individual students, such as learning basic phonics, sequencing stories, making inferences, or understanding new vocabulary. Also, the pandemic provided valuable opportunities for clinicians and supervisors to consider ways that all types of literacy assessments could be administered through digital platforms.

Mishra and Koehler (Citation2006) provide a frame to understand that clinicians had to bring their established knowledge of pedagogy into digital spaces. Teachers and supervisors had little choice but to adapt, integrate, and leverage their pedagogical strategies with technology tools and formats. For example, to successfully use digital texts, the clinician had to choose appropriate texts (TCK), model effective comprehension strategies using those digital texts (TPK), screen share and use available digital teaching tools (e.g., text highlighting) (TK), and then scaffold the students’ interactions with the digital texts (TPACK). Additionally, the TPACK model gives acknowledgment to the influence and importance of the context of teaching that includes adapting the needs of a class; or in the case of a literacy clinic, the needs of the students in the context of their families (MacKinnon, Citation2017; Mishra & Koehler, Citation2006). The pandemic provided an additional context of 3-way remote teaching and learning. Those clinicians with well-developed and practiced TPACK may have more easily navigated the pandemic pivot with positive outcomes and attitudes.

Looking more deeply at the instances of learning engagement in the instructional sessions, we turn to the data related to motivation and engagement. Some respondents voiced their perspectives that virtual platforms can never replace F2F venues for personal interaction. During the pandemic, instruction took place in separate physical spaces, there was restricted use of physical materials, and in some cases clinician-student interactions were constrained. However, others noted the possibility and reality of establishing valuable online presences. One respondent (#42) concluded “It is possible to build a child/tutor relationship over ZOOM. I saw it time and time again.”

In fact, online presence logically builds on the research foundations of literacy motivation and engagement (Cambria & Guthrie, Citation2010; Marinak & Gambrell, Citation2013). Even though intangible, participants can experience online presence in ways that are subjective (takes place in our mind), objective (being psychologically in the same space as others), and social (e.g., an online interactive community); (Lehman & Conceição, Citation2010). The survey results give evidence of all three of these dimensions of online presence. Respondents described the online presences of teachers, students, and families in the virtual spaces of remote literacy clinics; most significant were their descriptions of the communication and interaction among those that they observed, as well as what took place in their (the clinic directors’) own minds.

Relatedly, there is an established correlation between engagement and reading comprehension (Liebfreund, Citation2021). While focused on assessment and instruction of reading and writing, we happily report on engagement but do not have data on student achievement. Missing from this study, also, was any mention of the complexities of digital reading (Coiro, Citation2021). Hopefully, follow-up research will probe the factors of digital texts, activities, contexts, and the impact on readers.

Also, our survey was limited in furthering our understanding of whether the digital divide was maintained or crossed. Respondents voiced that they could only accept students to participate in a clinic if they had devices and reliable connectivity. Perhaps, literacy clinics can help bridge the gap in achievement between economically advantaged students and those who are economically disadvantaged. Earlier, that gap was found to be significantly greater for online reading comprehension–including locating information, reading critically, synthesizing, and communicating–than in reading and writing activities that were offline (Leu et al., Citation2015). Literacy clinic directors’ survey comments, though, point to future options for serving less privileged or geographically distant families, as was demonstrated during the pandemic. There may be some diversifying of the clinical practica experience as the online/remote clinics reach wider audiences. Some of the clinicians had the opportunity to work with more diverse populations. Expanding the reach of literacy clinics for clinicians and for students is a sprout from the pandemic experiences that may further develop in future years.

Looking more broadly, cultural or political contexts may help explain some of the variations among the respondents, as the survey responses represent many regions of North America and a few other countries. The data from our study contained a range of opinions about whether there was increased or decreased interaction with parents/caregivers; that may be explained by cultural, political, or geographic differences. Literacy clinics, as well as educational technology, must address the local needs of communities and families (Selwyn & Jandrić, Citation2020).

Limitations

Sampling can be a concern when using multi-stage sampling methods (Fowler, Citation1993). We could have missed recruitment of literacy clinic personnel who were not known to our researchers or who were not members of any of the leading literacy research organizations.

A second limitation of this research is that it was a snapshot in time during the spring of 2020. Given the dynamic nature of the pandemic, the impacts on literacy clinics continue to evolve. Consequently, these findings provide a window into decision-making at this important moment in time but may not translate to other semesters or years. The survey items prompted respondents to consider their practices in the “post-pandemic” timeframe. We now realize that this terminology was premature; we would have been wiser to frame the future-oriented questions in a more nuanced way.

The survey items were not sensitive to capture the reasons why there was such a range of contrasting responses. Also, we have become aware that some terms used in the questions (e.g., online, remote, digital, hybrid) are not universally defined; in fact, these were terms in transition during this study’s time period. In future research, we recommend that respondents provide conceptualizations of these terms. In fact, we are in the process of a follow-up interview study in which these conceptualizations and the chronological changes within the literacy clinics will be explored in-depth.

Finally, absent from the survey responses are any mention of whether increased access to online texts assisted with students having greater exposure to multicultural texts, even though they did express that they were able to gather substantial digital resources. Access to a greater range of children’s literature may, in the future, be a thrust forward toward more culturally sustaining literacy pedagogies (Ladson-Billings, Citation2014; Paris & Alim, Citation2017).

Conclusions and implications

This research opens new pathways forward for literacy clinics, for their explicit purposes of teacher education, support to K-12 students, and contributions to the research in literacy (Laster, Citation2013). The trajectory of effective practices that carried from F2F to virtual spaces included instruction that was informed by ongoing assessments using digital materials and digital platforms. Importantly, relationships and teacher autonomy were critical to the success of what occurred during the pandemic. We posit that these components of teacher decision-making will continue to be essential in clinics and classrooms.

Thus, this research adds to the appreciation of the complexities of digital literacies (Coiro, Citation2021) and of online presence (Lehman & Conceição, Citation2010). These findings reinforce the essential need to create engaging learning environments, whether F2F or in virtual spaces. Teacher educators and clinicians must continue to activate intentional planning for social and emotional engagement, as a pathway into instructional engagement.

Importantly, the growth of the use of technology had many tensions, as well as surprising successes. It is likely that whatever the state of the world, technology for teaching and learning will continue. TPACK helps to examine the specialized knowledge teachers need to usefully utilize technology as an instructional tool. Our research highlights a need to go beyond TPACK for the enhancement of digital literacies. All clinics, whatever their format, need to have a repository of digital resources readily available. This includes literacy assessments, as well as large collections of diverse culturally responsive digital texts of all levels, genres, and topics. Additionally, TPACK focuses on teacher knowledge rather than quality of technology integration. While it is expected that greater TPACK would result in higher quality technology integration, examining technology integration from an evaluative stance, such as Hughes et al. (Citation2006)’s Replacement, Amplification, and Transformation Framework would provide insight into the quality of the technology integration.

Furthermore, we recommend that whether clinics have formats that are F2F, hybrid, or online, there should be intensified attention to the practices of digital literacies as a significant and explicit focus of instruction. Teacher educators can support clinicians to explicitly instruct students in navigating multiple sites, comprehending a range of online texts and modalities, evaluating the authority of texts, and summarizing and synthesizing digital information.

In essence, this research contributes to our understanding of the pandemic-induced shifts that demonstrated the resiliency, collaboration, and creativity embedded in the parallel layers of learning by teacher educators, clinicians, and students in the contexts of their families. From this research, we gleaned that clinic directors, as well as clinicians, benefit greatly from collaboration. They share materials, assessments, and strategies, both in times of emergency, such as the pandemic, and routinely. Moreover, the data from this research demonstrated that families are essential helpers in the online spaces. A takeaway is that in all modalities clinicians and teacher educators should pivot to actively involve families in the immediate and long-term literacy growth of their children.

Finally, we hope that clinics will expand their perspectives on enhancing equity. For example, removing geographic boundaries by using technology expands recruitment of diverse students. Yet, digital devices, connectivity, and online resources are essential for broad participation, even when the clinic meets in person. In fact, internet access is a proposed human right (Szoszkiewicz, Citation2020; U.N, Citation2016). Thus, clinic personnel may be ideally situated to advocate for more digital opportunities for marginalized citizens.

In conclusion, we encourage all clinic stakeholders to reflect on what works in both F2F and online clinics. We expect each clinic will continuously evolve while attending to the professional development needs of the clinicians and the cultural contexts of the local community. Reading and writing assessment and instruction is dynamic; we learn from our experiments, our successes and failures, and our affordances and challenges. Research from literacy clinics is essential to our greater understanding of literacy learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bader, L. A., & Wiesendanger, K. D. (1986). University based reading clinics: Practices and procedures. The Reading Teacher, 39(7), 698–702. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20199193

- Bazerman, C. (2016). What do sociocultural studies of writing tell us about learning to write. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 11–23). The Guilford Press.

- Beaver, J., & Carter, M. (2019). Developmental reading assessment (3rd ed.). Pearson.

- Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Erlbaum.

- Bowers, E., Laster, B., Ryan, T., Gurvitz, D., Cobb, J., & Vazzano, J. (2017). Video for teacher reflection: Reading clinics in action. In R. Brandenburg, K. Glasswell, M. Jones, & J. Ryan (Eds.), Reflective theories in teacher education practice - process, impact and enactment (pp. 141–160). Springer Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3431-2_8

- Bromley, P., Schonberg, E., & Northway, K. (2015). Student perceptions of intellectual engagement in the writing center: Cognitive challenge, tutor involvement, and productive sessions. The Writing Lab Newsletter, 39(7–8), 1–6.

- Cabell, S. Q., & Hwang, H. (2020). Building content knowledge to boost comprehension in the primary grades. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S99–S107. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.338

- Cambria, J., & Guthrie, J. T. (2010). Motivating and engaging students in reading. New England Reading Association Journal, 46(1), 16–29.

- Charmaz, K. (2007). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Codling, R. M. (2013). Creating an optimal learning environment for struggling readers. In E. Ortlieb & E. H. Cheek (Eds.), Literacy research, practice and evaluation: Volume 2. Advanced literacy practices: From the clinic to the classroom (pp. 21–42). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Coffee, D., Hubbard, D., Holbein, M., & Delacruz, S. (2013). Creating a university-based literacy center. In E. Ortlieb & E. H. Cheek (Eds.), Literacy research, practice and evaluation: Volume 2. Advanced literacy practices: From the clinic to the classroom (pp. 21–42). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Coiro, J. (2021). Toward a multifaceted heuristic of digital reading to inform assessment, research, practice, and policy. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(1), 9–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.302

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publishers.

- Deeney, T., Dozier, C., Cavendish, L., Ferrara, P., Gallagher, T., Gurvitz, D., Hoch, M., Huggins, S., Laster, B., McAndrews, S., McCarty, R., Milby, T., Msengi, S., Rhodes, J., & Waller, R. (2019, December). Student and family perceptions of the literacy lab/reading clinic experience. Paper presented at the LRA Annual Meeting, Tampa, FL.

- Deeney, T., Dozier, C., Cavendish, L., Ferrara, P., Gallagher, T., Gurvitz, D., Hoch, M., Huggins, S., Laster, B., McAndrews, S., McCarty, R., Milby, T., Msengi, S., Rhodes, J., & Waller, R. (2020, December). Student perspectives of reading and participation in literacy labs/reading clinics. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Literacy Research Association, Online.

- Deeney, T., Dozier, C., Smit, J., Davies, S., Laster, B., Applegate, M., Cobb, J., Gaunty-Porter, D., Gurvitz, D., McAndrews, S., Ryan, T., Eeg-Moreland, M., Sargent, S., Swanson, M., Dubert, L., Morewood, A., & Milby, T. (2011). Clinic experiences that promote transfer to school contexts: What matters in clinical teacher preparation. In P. J. Dunston & L. Gambrell (Eds.), 60th yearbook of the literacy research association (pp. 127–143). Literacy Research Association.

- Dewey, J. (19021990). The child and the curriculum. The University of Chicago Press.

- Dozier, C., & Deeney, T. (2013). Keeping learners at the center of teaching. In E. T. Ortlieb & E. H. Cheeks (Eds.), Literacy, research, practice, & evaluation: From clinic to classroom (pp. 367–386). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Dozier, C., Johnston, P., & Rogers, R. (2006). Critical literacy/critical teaching: Tools for preparing responsive teachers. Teachers College Press.

- Drew, S. V., & Sosnowski, C. (2019). Emerging theory of teacher resilience: A situational analysis. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 18(4), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-12-2018-0118

- Dubert, L. A., & Laster, B. (2011). Technology in practice: Educators trained in reading clinic/literacy labs. Journal of Reading Education, 36(2), 23–29.

- Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S25–S44 . https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

- Evensen, D. (1999). Introduction. In P. Mosenthal & D. Eversen (Eds.), Reconsidering the role of the reading clinic in a new age of literacy (pp. ix–xii). JAI Press.

- Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1984). Images, plans, and prose: The representation of meaning in writing. Written Communication, 1(1), 120–160.

- Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1994). A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. In R. B. Ruddell, M. R. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading. International Reading Association (pp. 928–950).

- Fowler, F. J. (1993). Survey research methods (2nd ed). Sage Publishers.

- Francom, G. M., Lee, S. J., & Pinkney, H. (2021). Technologies, challenges and needs of K-12 teachers in the transition to distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. TechTrends, 65(4), 589–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00625-5

- Gergen, K. J. (1985). The social constructionist movement in modern psychology. American Psychologist, 40(3), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.40.3.266

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

- Graham, S. (2006). Writing. In P. Alexander & P. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 457–477). Erlbaum.

- Graves, D. H. (1983). Writing: Teachers and children at work. Heinemann Educational Books.

- Graves, D. (1994). A fresh look at writing. Heinemann Publishing.

- Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1986). Writing research and the writer. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1106–1113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1106

- Heflich, S. R., & Smith, W. E. (2012). Transitioning online: Moving a graduate reading program online while continuing to maintain program rigor and meet standards. In L. Martin, M. Boggs, S. Szabo, & T. Morrison (Eds.), Association of literacy educators and researchers yearbook: The joy of teaching literacy (Vol. 34, pp. 105–119). Association of Literacy Educators and Researchers.

- Hoffman, J., Svrcek, N., Lammert, C., Daley-Lesch, A., Steinitz, E., Greeter, E., & DuJulio, S. (2019). A research review of literacy tutoring and mentoring in initial teacher preparation: Towards practices that can transform teaching. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 233–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X19833292

- Hruby, G. (2001). Sociological, postmodern, and new realism perspectives in social constructionism: Implications for literacy research. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(1), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.36.1.3

- Hughes, J., Thomas, R., & Scharber, C. (2006, March). Assessing technology integration: The RAT–replacement, amplification, and transformation-framework. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 1616–1620). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

- Kalyanpur, M., & Kirmani, M. H. (2005). Diversity and technology: Classroom implications of the digital divide. Journal of Special Education Technology, 20(4), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264340502000402

- Kymes, A. (2005). Teaching online comprehension strategies using think-alouds. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(6), 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1598/jaal.48.6.4

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A. K. A. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

- Laster, B. (1999). Welcoming family literacy at the front door. In P. Mosenthal & D. Eversen (Eds.), Reconsidering the role of the reading clinic in a new age of literacy (pp. 325–346). JAI Press.

- Laster, B. (2013). A historical view of student learning and teacher development in reading clinics. In E. T. Ortlieb & E. H. Cheeks (Eds.), Literacy, research, practice, & evaluation: From clinic to classroom (pp. 3–20). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Laster, B., & Finkelstein, C. (2016). Professional learning for educators focused on reading comprehension. In S. E. Israel (Ed.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (2nd ed.), pp. 70–83). Guilford.

- Laster, B., Rhodes, J., & Wilson, J. (2018, April). Literacy teachers using ipads in clinical settings. In E. Langran & J. Borup (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 544–550). Washington, D.C., United States: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/182579

- Laster, B., Rogers, R., Gallagher, T., Scott, D. B., Vasinda, S., Orellana, P., Rhodes, J., Waller, R., Deeney, T., Hoch, M., Cavendish, L., Milby, T., Butler, M., Johnson, T., Msengi, S., Dozier, C., Huggins, S., & Gurvitz, D. (2021, December). Contrapuntal voices from literacy clinics during COVID-19: What do we harvest for the future? Literacy Research Association Conference, Atlanta, GA., USA.

- Laster, B., Tysseling, L., Stinnett, M., Wilson, J., Cherner, T., Curwen, M., Ryan, T., & Huggins, S. (2016). Effective use of tablets (iPads) for multimodal literacy learning: What we learn from reading clinics/literacy labs. The App Teacher. https://appedreview.com/effective-use-tablets-ipads-multimodal-literacy-learning-learn-reading-clinicsliteracy-labs/

- Lehman, R. M., & Conceição, S. C. (2010). Creating a sense of presence in online teaching: How to“ be there” for distance learners (Vol. 18). John Wiley & Sons.

- Leslie, L., & Caldwell, J. S. (2017). Qualitative reading inventory (6th) ed.). Pearson North America.

- Leu, D. J., Forzani, E., Rhoads, C., Maykel, C., Kennedy, C., & Timbrell, N. (2015). The new literacies of online research and comprehension: Rethinking the reading achievement gap. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.85

- Liebfreund, M. D. (2021). Cognitive and motivational predictors of narrative and informational text comprehension. Reading Psychology, 42(2), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2021.1888346

- Lilienthal, L. K. (2014). Moving the university reading clinic online. In S. Szabo, L. Haas, & S. Vasinda (Eds.), Exploring the world of literacy: Thirty-sixth yearbook (pp. 179–193). Association of Literacy Educators and Researchers.

- Lindner, J., Clemons, C., Thoron, A., & Lindner, N. (2020). Remote instruction and distance education: A response to COVID-19. Advancements in Agricultural Development, 1(2), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v1i2.39

- Lohnes-Watulak, S., & Laster, B. P. (2016, December). Take 2: A second look at technology stalled: Exploring the new digital divide in one urban school. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 12(2), 1–2. http://jolle.coe.uga.edu/take-2/

- Lonigan, C. J., Burgess, S. R., & Schatschneider, C. (2018). Examining the simple view of reading with elementary school children: Still simple after all these years. Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518764833

- MacArthur, C., & Graham, S. (2016). Writing research from a cognitive perspective. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 24–40). Guilford Press.

- MacKinnon, G. R. (2017). Highlighting the importance of context in the TPACK model: Three cases of non-traditional settings. Issues and Trends in Learning Technologies, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.2458/azu_itet_v5i1_mackinnon

- Marinak, B. A., & Gambrell, L. B. (2013). Meet them where they are: Engaging instruction for struggling readers. In Ortlieb, E. and Cheek, E.H. (Ed.), School-based interventions for struggling readers, K-8 (pp. 41–60). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2048-0458(2013)0000003006

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A new framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 108(6), 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

- Msengi, S., & Laster, B. (2022). Pivots during Covid-19: Teachers, students, parents, and supervisors in the circle of literacy clinics. In V. Shinas (Ed.), Cases on practical applications for remote, hybrid, and hyflex teaching (pp. 244-265). IGI Global.

- National Academy of Education. (2020). COVID-19 educational inequities roundtable series, summary report. National Academy of Education. https://naeducation.org/covid-19-educational-inequities-roundtable-series-summary-report/

- Onyema, E. M., Nwafor, C., Obafemi, F., Shuvro, S., Fyneface, G. A., Sharma, A., & Alhuseen, O. A. (2020). Impact of coronavirus pandemic on education. Journal of Education and Practice, 11(13). https://www.iiste.org 2222-288X.

- Ortlieb, E., & McDowell, F. D. (2016). Looking closer at reading comprehension: Examining the use of effective practices in a literacy clinic. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 15(2), 260–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-08-2015-0069