ABSTRACT

Japanese Lesson Study (JLS) is a professional development method, involving teachers collaboratively planning lessons, observing their enactment, then discussing observations of teaching and learning. This paper explores translation of JLS internationally, seeking to understand how and why it is adapted and how an understanding of national culture and implementation paradigms might support translation.

We begin by examining evidence on adaptation and challenges of JLS implementation internationally, finding both deviation from the seven components of JLS, and qualitative evidence of perceived challenges to successful implementation.

Further we explore two bodies of the literature explaining how and why such adaptations occur. First, implementation science reveals that full fidelity appears not to be amenable to the complexity of education innovations like LS, but that adaptation is fraught with challenges, with no linear pathway. Secondly, Hofstede’s and colleagues’ dimensions of culture enable us to hypothesise about how Japan’s culture might have framed development of JLS, and to predict possible challenges when translated into a host nation.

Finally, we hypothesize as to the relationship between adoption of either fidelity or adaptation implementation paradigms, and identified differences between Japan and the host nation’s national culture, suggesting avenues for further research which may serve to test hypotheses empirically.

Introduction

Lesson Study (LS) is a collaborative approach to professional development (PD) that originated in Japan. LS is translated from the Japanese words jugyou (instruction or lesson) and kenkyu (research or study), and involves teachers collaboratively planning a lesson, observing it being taught, then discussing what they have learnt about teaching and learning (Fernandez Citation2002). Fujii says ‘for Japanese educators, lesson study is like air, felt everywhere because it is implemented in everyday school activities’ (Fujii Citation2014, p. 3): LS in Japan is systemic and embedded.

Whilst LS can take multiple forms in Japan, operating at school, local and national level, this paper relies on Seleznyov’s (Citation2018) seven components of school-based LS, the main PD system for in-service teachers at Japan’s elementary and middle schools (Fujii Citation2016b):

Identify focus: Teachers compare long-term goals for pupil learning and development to pupils’ current learning characteristics in order to identify a school-wide research theme, which may be pursued for 2 or 3 years;

Planning: Teachers work in collaborative groups to carry out kyozai kenkyuu (a study of material relevant to the research theme) leading to the production of a collaboratively written plan for a research lesson. The detailed plan, written over several meetings, attempts to anticipate pupil responses, misconceptions and successes for the lesson, and provides a written account of the lesson’s place within the unit, explains the lesson’s relevance to the school’s research theme, and details decisions taken about the activities to take place during the lesson;

Research lesson: The research lesson is taught by a nominated teacher, who is a member of the collaborative planning group. Other group members act as silent observers, collecting any available evidence of pupil learning, with a particular focus on the research theme;

Post-lesson discussion: The collaborative group meet to formally discuss the evidence gathered, following a set of conversation protocols. Their learning in relation to the research theme is identified and recorded by the discussion chair. It is intended that this learning informs subsequent cycles of research;

Repeated cycles of research: Subsequent research lessons are planned and taught that draw on the findings from the post-lesson discussions. These are new lessons and not revisions nor re-teachings of previous research lessons. They may involve new nominated teachers and new classes;

Outside expertise: There is input from a koshi or knowledgeable other into the planning process and the post-lesson discussion. This may be an academic, a local area adviser or a very experienced teacher from another school;

Mobilising knowledge: Opportunities are created for teachers working in one LS group to access and use the knowledge from other groups, through observing other groups’ ‘open house’ research lessons both within and beyond their own school, from the koshi’s experiences of networking across schools, or through the publication of the lesson plan and the group’s research findings (Seleznyov Citation2018, pp. 220–221).

LS as an approach to in-service teacher PD has increased in popularity internationally over the last three decades (Xu and Pedder Citation2014), despite the initial sparsity of research clarifying its practices (Fujii Citation2014) or demonstrating its impact on pupil learning (Seleznyov Citation2019). However, numerous studies have highlighted challenges faced by those seeking to implement and use LS outside Japan (e.g. Lim et al. Citation2011, Lee and Ling Citation2013, Verhoef et al. Citation2015).

This paper seeks to support practitioners using or considering introducing LS in their own contexts as an approach to in-service teacher PD by attempting to understand how and why LS might need to be adapted in contexts outside Japan. We start by exploring the trajectory of LS internationally as a borrowed policy (Cartwright Citation2013): evidence of the challenges international users have faced and of adaptions being made to the Japanese LS model, using Seleznyov’s (Citation2018) seven components of LS. We further explore implementation science literature (Durlak Citation1998) and adaptation in particular, focusing on its relevance to international policy borrowing. Finally, we use Hofstede et al.’s (Citation2010) analysis of cultural differences at national level as a theoretical lens by which local adaptations made by international practitioners might be anticipated and understood. We conclude by offering practical advice to practitioners seeking to introduce and implement LS in contexts beyond Japan and suggesting avenues for future research.

The research questions are:

How is Japanese LS adapted when implemented in international contexts and why?

How might an understanding of national culture be relevant in understanding how Japanese LS is adapted?

Lesson Study as borrowed policy

Over recent decades, LS has gained extensive traction across Europe, Asia, Africa, North and South America (Isoda Citation2007, Fujii Citation2014), as a ‘travelling reform’ (Steiner-Khamsi and Waldow Citation2012): a reform borrowed from another nation to address perceived problems in performance. Significant recent examples of travelling reforms include the Shanghai mathematics project in the UK, in which teachers from Shanghai and the UK visit each other’s schools to learn about the Shanghai approach and see it actualised in UK classrooms (Boylan et al. Citation2019).

Whilst the recent exponential growth of such policy borrowing has provided opportunities for education, it has also thrown up considerable challenges (Cartwright Citation2013), not least as a result of the marketisation of international policy borrowing, with claims to simple solutions to local problems of practice (Burdett and O’Donnell Citation2016). If not carefully handled, there can be a significant mismatch between the borrowed policy and its new context, and considerable resistance by stakeholders in local education systems, meaning the policy may either have limited longevityfor example, failing to become an embedded approach once funding and support is stopped, or fail to achieve its main goals or expected impact (Dolowitz Citation2009).

The majority of the research on education policy borrowing has focused on:

•curriculum and pedagogy, for example UK adoption of Swiss approaches to teaching mathematics (Ochs Citation2006); Vavrus and Bartlett on Tanzania’s attempt to emulate US pedagogies (Vavrus and Bartlett Citation2012); the UK Shanghai maths project (Boylan et al. Citation2019);

•assessmentfor example, Sweden’s interest in reforming assessment systems (Forsberg and Román Citation2014); the global emergence of National Qualification Frameworks (Chakroun Citation2010);

•organisationfor example, Germany’s vocational training (Tomlinson Citation2005) and OECD’s push for lifelong learning (Grek Citation2013).

A search for the literature on the feasibility of borrowing PD practices for in-service teachers yields few results. Harris et al. (Citation2016) review of leadership preparation and development across seven education systems is one of the only studies; it showed that increased policy borrowing was leading to a convergence of approaches to leadership PD, and that issues of culture and context were being ignored, to the detriment of successful implementation. In this context, the implementation of LS beyond Japan provides a rich source of evidence on the successes and challenges of the translation of teacher PD practices. The next section explores the evidence of such challenges to the introduction and implementation of LS internationally.

Challenges to the translation of LS

Whilst Japanese authors recognise the need for ‘creative transformation’ (Isoda Citation2007) of LS beyond Japan, they also note that this:

‘[…] may entail the loss of some of the powerful influences that shape and give direction to lesson study in Japan’ (Isoda Citation2007, p. xxiii).

Similarly, Chokshi and Fernandez (Citation2004) claim ‘Lesson study is easy to learn, but difficult to master’ (p. 524). They warn that educators may:

‘ … focus on structural aspects of the process … or … mimic its superficial features, while ignoring the underlying rationale.’ (p. 524)

Seleznyov’s (Citation2018) systematic literature review explored how faithful international implementation of LS was to the components of Japanese LS. Of 97 studies published between 2005 and 2015:

33% did not include identification of a research theme;

63% did not include kyozai kenkyuu, or the study of material relevant to the research theme, a crucial part of lesson planning in Japan;

60% involved revising and re-teaching a lesson, or polishing a ‘perfect’ lesson;

55% did not engage a koshi or knowledgeable other; and

61% did not mention mobilising knowledge between LS groups.

Qualitative studies of translation of LS provide evidence for the reasons why it has been challenging to maintain the integrity of LS practices in international contexts. Several authors noted the lack of structures and systems to accommodate LS, especially time, as an impediment to implementation and sustainability (e.g., White et al. Citation2005, Lee and Ling Citation2013, Abdella Citation2015, Groves et al. Citation2016, Godfrey et al. Citation2019). These challenges were attributed to specific features of the Japanese education system, in which LS is systemic and embedded, being absent in non-Japanese contexts. For example, school structures such as timetabling and non-teaching time facilitate LS, a ‘Research Steering Committee’ exists in each school, there are regular year group meetings and teacher work rooms where colleagues discuss learning (Lee and Ling Citation2013). Similarly, at system level, there are designated research schools, national and district funding, and an expectation that teachers investigate proposed national curriculum changes through LS (Lewis Citation2000).

A focus on demonstrating short term impact in many nations proved similarly challenging, given the long-term developmental goals of LS in Japan (e.g. Lewis et al. Citation2006, Lim et al. Citation2011).

US authors noted that weak teacher research skills led to shallow engagement in LS: US teachers struggled to develop a research hypothesis, design an appropriate classroom experiment, gather and use appropriate evidence, and generalise findings (Fernandez Citation2002, Murata Citation2011). Similarly, teachers in the Netherlands who did not view LS as a research process designed to develop teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge were less likely to sustain the approach nor to include those stages of LS which distinguished it as an inquiry process (Wolthuis et al. Citation2020).

A dearth of access to quality learning and research material have made kyozai kenkyuu, the preparatory study phase of lesson planning, difficult to achieve in some nations (e.g. Lewis et al. Citation2006, Lim et al. Citation2011, Williams et al. Citation2014, Groves et al. Citation2016). Similarly, the absence of available koshis and associated costs have made it difficult for schools to access outside expertise to support LS processes (e.g. Fernandez Citation2002, Wake et al. Citation2013). Akiba et al. (Citation2019) showed that relying solely on expertise within US schools did in some circumstances lead to lower quality LS discussions.

Finally, it has been claimed that accountability pressures have left teachers unwilling to engage in LS or heavily focused on curriculum coverage to the detriment of learning about pedagogy (e.g. White et al. Citation2005, Verhoef et al. Citation2015, Abdella Citation2015). Several authors noted that such pressures had led teachers to refocus LS as an opportunity to showcase ‘excellent’ teachers, or to be polite instead of offering constructive criticism, thereby failing to engage in rich conversations about learning (e.g. Perry and Lewis Citation2009, Wake et al. Citation2013).

In summary, literature has highlighted and sought to explain why international projects have adapted LS, either missing out components altogether, or struggling to implement them as intended. Given the extensive evidence of adaptations to and challenges in the implementation of LS practices outside Japan, this paper therefore seeks to explore how and why Japanese LS is adapted when implemented in international contexts, and how national culture is relevant in understanding how LS can be effectively adapted.

To answer these questions, the paper goes on to review two bodies of the literature, first implementation science, which explores the mechanisms by which any change to PD practices might be introduced in a sustainable and successful way (Lendrum and Humphrey Citation2012); and secondly culture, which may explain the particular challenges an alien PD practice such as LS might face when implemented internationally.

A framework to understand the translation of LS

Whereas LS developed in situ within Japan, internationally LS is introduced as an innovation to current teacher PD practices. In order to understand adaptations and challenges to implementation, it is important to understand both the general challenges any implemented change to practice might face, and the challenges that might be specific to a complex practice like LS, with its seven key components (Seleznyov Citation2018). Insights from implementation literature may explain how and why adaptation occurs, and whether the implementer should be concerned about such adaptations.

It is also important to consider whether any adaptations occur as a result of LS being translated into a culturally alien milieu, a consideration raised by the international policy borrowing literature. Hofstede et al.’s (Citation2010) national dimensions of culture are used to consider the extent to which LS aligns with Japan’s national culture, and is therefore a product of its birthplace. Their model also enables us to consider the possible challenges the introduction of LS into a different national culture might engender, and how practitioners might anticipate and plan to tackle such challenges, or seek necessary adaptation to LS’s new context.

We recognise that differences in education system structures across nations may also help explain implementation challenges and present necessary adaptations. For reasons of space, and given that education system structures could be seen as by-products of national culture, this field of the literature is not prioritised in this paper.

Lesson Study: implementation and adaptation

Durlak (Citation1998) defines implementation as ‘how well a proposed programme or intervention is put into place’ (p. 5). Lendrum and Humphrey (Citation2012) review of implementation literature argued that the most serious threat to an innovation’s success might be quality of implementation. Similarly, Sherer and Spillane (Citation2011) noted the constancy in schools of change, and that proposed changes rarely moved beyond enthusiastic promises and initial energy; a successful implementation process may be key to enabling change.

Implementation literature falls broadly into two categories: fidelity paradigm and adaptation paradigm. Harn et al. (Citation2013) define fidelity as ‘the degree to which a treatment/intervention is implemented as intended’ (p. 182). It is interesting to note that the majority of implementation science literature, especially that focusing on fidelity, comes from medicine and prevention science, and when applied in school contexts, it is frequently in the context of a medical-education hybrid, such as a pupil mental health programme (Harn et al. Citation2013).

Albers and Pattuwage (Citation2017) systematic review of implementation studies in education did identify that higher fidelity produces better outcomes for pupils, but was unable to specify what sufficiently high fidelity means in practice, noting that expectations of near-perfect fidelity may not only be unrealistic but may actually reduce impact. Durlak and DuPre’s systematic review of studies of pupil mental health prevention and promotion (Durlak and DuPre Citation2008) noted that 60% fidelity had been associated with positive outcomes, and that few programmes attained fidelity rates over 80%. For example, Telzrow et al.’s (Citation2000) study of the introduction of behavioural problem-solving approaches into 227 US schools found that student outcomes improved significantly even though two of eight components of the programme were not implemented with fidelity, despite these two components having been consistently verified as important in previous related studies. Harn et al. (Citation2013) state that a focus on high fidelity could be misleading:

‘if student performance is good, but the fidelity observation is low, do … educators really want to allocate their limited resources to more training for the purpose of increasing fidelity?’ (p. 190)

In this way, international implementers of adapted versions of LS might see evidence of impact on teachers and pupils both as corroborating the appropriateness of local adaptations, and of the unnecessary nature of full fidelity. Furthermore, both Lendrum and Humphrey (Citation2012) and Harn et al. (Citation2013) noted that fidelity was dynamic and might deteriorate or improve over time, particularly for complex or multi-component innovations like LS. For example, Schaper, McIntosh and Hoselton (Citation2016) explored rates of fidelity across 353 schools in the US to a complex behaviour management intervention, and found that levels of fidelity varied over time and at school level, peaking during the second of 4 years of implementation.

Both fidelity and adaptation paradigms agree that the introduction of any new practice into a social setting relies on the complex interplay between the characteristics of the new practice and the setting, what Datnow et al. (Citation1998) refer to as ‘conditional matrix’. In education, innovations were usually more multidimensional than in medicine and prevention science, since consideration must be taken of not just what is done and for how long, but also how well, and in which context, for example by who, to whom and in which setting (Harn et al. Citation2013). Whilst the fidelity paradigm can offer valuable insights into implementing and adapting innovations successfully, and ensuring they have positive impact on pupils, it also:

‘follows a rather linear and rational logic incompatible with complex practice environments and … presents too linear an approach in that it views frontline staff as pure deliverers of manualised programs’ (Albers and Pattuwage Citation2017, p. 21)

By contrast, the adaptation paradigm sees local adaptation as supporting congruence between the innovation and its setting, improving outcomes and sustainability, and making implementation viable (Lendrum and Humphrey Citation2012). One example is the US schools’ Drug Abuse Resistance Programme, which was quickly implemented and frequently adapted, yet showed lasting effects and long-term sustainability (Tobler et al. Citation1994). Adaptation has commonly been seen as implementation failure (Lendrum and Humphrey Citation2012) and there has therefore been less research on its effectiveness. However, Lendrum and Humphrey (Citation2012) noted that:

‘Increasingly, … researchers are suggesting that it is a complex mix of both fidelity and adaptation that contributes to the effectiveness of an intervention rather than fidelity alone’ (p. 636)

For example Bryk (Citation2016) states that a simple innovation that does not require practitioners to change their own classroom practices in any way, will benefit from full fidelity. So Wijekumar et al.’s (Citation2013) online reading comprehension development programme, which simply involved students being supervised to work through a series of online tasks, sought fidelity in terms of ensuring software and hardware was functional and lesson time was allocated, and supervising students to prevent ‘gaming’ by skipping tasks: their impact evaluation showed that where fidelity was high, student outcomes improved (Wijekumar et al. Citation2013). Other more complex innovations with several new processes and tools, changes in staff roles, considerable development of knowledge and/or skills, and changes in the ways participants act and think, require what Bryk calls ‘adaptive integration’. Like LS’s seven components, such innovations consist of ‘a set of interrelated actions, all of which stand in strong relationship with one another’; a weakness in any one element may mean failure to achieve intended outcomes. Bryk (Citation2016) advises the implementer not to measure fidelity, but to ask whether local changes are consistent with the intervention’s original design principles, and to gather evidence as to how well the adapted innovation is working, for whom and under what circumstances.

Lendrum and Humphrey (Citation2012) stated that effective innovations often clarified which components can and should be locally adapted, and which required fidelity (Lendrum and Humphrey Citation2012). Wigelsworth et al.’s (Citation2012) review of the light touch rollout of the UK’s social and emotional learning programme in secondary schools, which did not require fidelity, found that compared with the carefully implemented pilot projects, impact on outcomes was low, and attributed this to confusion about which components would benefit from fidelity. Brown (Citation2019) suggests it is easier to reach fidelity in terms of an innovation’s intended achievements by being ‘unfaithful’ in the new cultural context. This aligns with Isoda’s (Citation2007) description of the need for a ’creative transformation’ of LS.

However, implementers might be rightly wary of pushing flexibility too far, leading to a less successful innovation. Although Murata (Citation2011) sees modifications to international LS as ‘expected and essential’, she also highlights the danger of losing what is powerful through excess modifications. The tipping point between too much and too little adaptation needs to consider the relative effects of surface and deep structural changes (Lendrum and Humphrey Citation2012), and may be highly innovation-dependant. Harn et al. (Citation2013) stress the importance of identifying the ‘active ingredients (p. 184), or what Domitrovich et al. (Citation2008) call the ‘core components’, enabling implementers to understand the underlying theory and the rationale for fidelity. For example, positioned as a programme to be adapted locally, Molloy et al. (Citation2013) used data from 166 US user schools to identify the ‘active ingredients’ of a behaviour programme that schools experiencing one of three behavioural problems might focus on. Unfortunately, the literature has done little more than describe the components of Japanese LS, not distinguishing empirically between core and desirable components nor exploring impact of different combinations of adaptations, largely due to the dearth of large-scale LS impact evaluations (Seleznyov Citation2019).

In conclusion, implementation is a complex process, treading a fine balancing act between a focus on fidelity or adaptation. Full fidelity does not seem to be amenable to complex multi-component education innovations like LS, but adaptation is fraught with challenges, with no linear pathway to successful implementation. As detailed above, literature has highlighted two ways in which international projects have adapted LS: either projects have missed out components, or struggled to implement them as intended.

The next section explores culture as a concept which might help international LS implementers anticipate some of the challenges to the introduction and sustainability of LS, and decide which adaptations might be relevant or necessary in their own contexts.

Lesson study: culture and adaptation

Alexander (Citation2001) describes life in schools inseparable from that of wider society: ‘a culture does not stop at the front gates’ (p. 29–30); the character and functions of schools are shaped by cultural values and beliefs that shape our lives more broadly. The concept of culture is widely used, but its definition remains elusive, both across and within disciplines (Baldwin et al. Citation2006). For the purpose of this paper, Hofstede et al.’s (Citation2010) definition of culture, building on Kroeber and Kluckhohn (Citation1952) classic definition, is used: ‘the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others’ (Hofstedeet al., Citation2010, p. 6). Hofstede et al. (Citation2010) state that unlike personality, culture is learned and not innate, constantly reproduces itself, and is manifested through ‘symbols, heroes, rituals and values’ (p. 7).

Hofstede et al.’s (Citation2010) empirical study of cultural differences across 76 nations involved surveys administered to employees from a single multinational organisation and enabled a categorisation of national cultural differences along six dimensions. Hofstede’s work has experienced enduring popularity since its original publication in the 1970s and succeeded in maintaining its status as the most reliable model of national culture. Various authors have criticised Hofstede’s use of the nation as a unit of study (McSweeney Citation2002), his failure to consider the effects of organisational culture (McSweeney Citation2002), not taking into account political climate (Jones Citation2007), the idea that culture can is uniform across nations (Oyserman et al. Citation2002), and his methodologies (McSweeney Citation2002, Fang Citation2003, Jones Citation2007). However, a number of replication studies and meta-analyses over several decades have corroborated one or many of Hofstede’s original results and dimensions (e.g., Hoppe Citation1990, Søndergaard Citation1994, Mouritzen and Svara Citation2002), and several have shown that whilst nations’ cultures may change over time, relative positions remain intact (Hofstede et al. Citation2010). It would therefore seem that Hofstede’s model offers a reliable framework within which to understand culture and how it might shape local responses to Japanese LS.

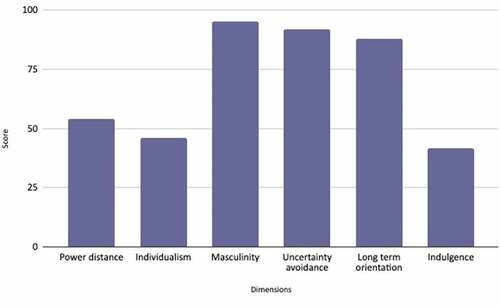

We use Hofstede’s six dimensions to hypothesise about how Japan’s culture may have shaped development of LS since it began in the 1860s, and about the introduction and implementation of LS outside Japan, particularly in nations with very different cultural profiles. shows Japan’s overall profile across the six dimensions.

Figure 1. Japan’s scores across six cultural dimensions using Hofstede’s published data (Hofstede Citation2010).

compares Japan’s scores to mean and median scores for all countries in the dataset, showing the range for each dimension based on Hofstede’s published data (Hofstede Citation2010)

Table 1. Japan’s cultural profile and comparisons to full data set.

For three dimensions, Japan’s scores sit relatively close to median scores, namely:

a)Power distance

‘The extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organisations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally’ (Hofstede et al. Citation2010, p. 61). Japan scored 54 on this measure, only slightly above the median score of 62.

b)Individualism

Individualistic societies are those where:

‘ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him- or herself and his or her immediate family … .[whereas] in collectivist societies, people … . are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty’ (Hofstede et al. Citation2010, p. 92). Japan scored 46, just above the median score of 45.

c)Indulgence

‘Indulgence stands for a tendency to allow relatively free gratification of basic and natural human desires related to enjoying life and having fun … . … .[whereas] restraint reflects a conviction that such gratification needs to be curbed and regulated by strict social norms.’ (Hofstede et al. Citation2010, p. 281) Japan scored 42, only slightly below the median score of 45.

Whilst we recognise that a significantly different score to that of Japan on any of the above dimensions might mean a host nation could face cultural challenges to LS’s implementation and sustainability, this paper focuses on three of Hofstede’s dimensions for which Japan’s scores fall into the top quartile (see above). These high scores might reasonably be presumed to have had a stronger impact on the design of LS’s seven components (Seleznyov Citation2018). The three dimensions are listed below, and we seek both to explore the possible relationship between these strong cultural beliefs and the seven components of LS, and to hypothesise as to the challenges a nation with very different scores in these dimensions might face.

d)Masculinity

In masculine societies:

‘emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life’ (Hofstede et al. Citation2010, p. 140). Japan scored 95, almost double the median score of 49.

Masculine societies encourage commitment to one job for life, and therefore believe that challenge, career progression and recognition are vital (Hofstede et al. Citation2010). LS is a practice which enables teachers to receive both challenge and recognition, supporting lifelong career progression. Teaching the research lesson observed by all school staff, invites challenge from more experienced colleagues. Teaching an ‘open house’ research lesson (Fernandez and Yoshida Citation2012) which is accessible to all teachers from the district, provides opportunity for a public display of skills. Post-lesson discussions also offer colleagues opportunities to visibly share expertise, as they offer colleagues productive feedback. LS offers valuable opportunities for career progression: experienced LS teachers can lead school Research Groups, become koshis, or become involved in high profile regional or national LS groups (Fujii Citation2016b).

Japanese teachers commit many hours to the LS planning process often above and beyond usual working hours, aligning with masculine societies’ tendency to ‘live in order to work’ (Hofstede et al. Citation2010, p. 167). Lesson planning for each research lesson cycle can take up to 6 months (Fujii Citation2016a) and about 10–15 hours of each teacher’s time (Fernandez Citation2002).

Countries with more feminine profiles may be less willing to want to teach research lessons, or to offer critical feedback, since their focus is on harmonious relationships (Hofstede et al. Citation2010), and not on seeking visible success. Teachers may be less likely to commit sufficient time to LS, without reduced teaching commitments, since feminine societies work to live, instead of living to work (Hofstede et al. Citation2010).

e)Uncertainty avoidance

‘The extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations’ (Hofstede et al. Citation2010, p. 191). Japan scored 92, 22 points above the median score of 70.

Hofstede (Citation2010) state that uncertainty avoidance is not risk avoidance, but rather a rejection of ambiguity. Protocols and rules help avoid ambiguity, hence LS is structured, rule bound, and almost ritualistic, as exemplified in the carefully sequenced components of LS (Seleznyov Citation2018). Similarly, LS is timetabled carefully across the school year, each teacher joining a subject team, each subject team leading one research lesson, which every teacher in the school will observe. Protocols dictate that as new teachers develop relevant expertise and confidence, each is identified in sequence to teach a research lesson (Fernandez and Yoshida Citation2012).

The lengthy, meticulous and detailed planning of LS, including significant time spent predicting student responses, helps avoid unanticipated events in the research lesson. Uncertainty avoidance may also explain a heavy emphasis in Japanese LS planning on the slow and careful process of kyozai kenkyuu, in which teachers explore relevant evidence from nationally sanctioned teacher manuals and other schools’ LS reports, before planning lesson (Murata Citation2011). By building on what is already known, it is easier to predict with reasonable accuracy what students’ common misconceptions might be, and to therefore produce a detailed anticipatory plan.

In line with uncertainty avoiders’ tendency to work hard, Japanese LS relies on teachers committing many hours to planning (Fujii Citation2016a), often above and beyond usual working hours. Teachers in uncertainty avoiding cultures like Japan know they are likely to stay in the same workplace for some time, and LS is therefore designed around a commitment to slow, incremental learning: a school’s research theme lasts 2 to 3 years. In this way, LS focuses on development of teacher expertise over decades, not months (Lewis et al. Citation2006).

Uncertainty avoidance also explains the role of koshi, as there is a greater tendency to revere expertise. The koshi’s views on the research lesson are not for discussion or debate, she is treated with reverence, and views she offers are always built into subsequent research lessons (Fujii Citation2016b).

Nations with contrasting profiles may find that teachers do not adhere to the carefully structured stages of the LS process, preferring to flex the rules to better meet their own needs and desire for creative freedom. Teachers may not value investing considerable hours in planning, perceiving this as unnecessary extra workload, particularly spending time pouring over study material and anticipating pupil responses. Instead, a quickly thought-through lesson plan may suffice, since for low uncertainty avoidant nations, learning happens whilst doing (Hofstede et al. Citation2010). Similarly, teachers may want to move on quickly from one research theme to the next, even if not fully explored, since low uncertainty avoidant nations focus on innovation, rather than long term development of ideas (Hofstede et al. Citation2010). The koshi or knowledgeable other may be seen as unnecessary, teachers instead believing that teachers bring sufficient practice-based expertise to the process.

f)Long-term orientation

‘The fostering of virtues oriented toward future rewards – in particular perseverance’ (Hofstede et al. Citation2010, p. 239). Japan scored 88, almost double the median score of 45.

Japan’s long-term orientation and associated belief in perseverance and effort (Hofstede et al. Citation2010) is clearly seen in LS, where a research theme will be pursued by a school for at least 2 years (Takahashi Citation2014) and involve considerable teacher time. Long-term solutions matter more than short-term goals; in LS, the research lesson itself is not the end of the process, merely one stage in the long journey towards knowledge.

Long-term oriented societies focus on learning, accountability, self-discipline, and effort (Hofstede et al. Citation2010), as exemplified in LS, a process in which all teachers learn within a framework of collective professional accountability, demonstrating their self-discipline and effort, through diligent application in the collective planning process, each teacher taking responsibility for teaching research lessons in turn. All teacher participants are positioned as learners, from novice to koshi (Fujii Citation2016b).

Having free time is less important in these societies (Hofstede et al. Citation2010), again, supporting the significant time commitment to LS. There is a focus on avoiding shame (Hofstede et al. Citation2010), which may also encourage teachers to commit considerable time to planning research lessons. However, long-term orientation values the goal more than the individual, and encourages humility (Hofstede et al. Citation2010); we can see how this may have helped shape the post-lesson discussion, where evidence of learning enables non-threatening criticism of the research lesson teacher. Quotes from Japanese teachers demonstrate the humility with which teachers receive criticism:

‘It is very hard thing to do because everybody has pride in his or her teaching. I know nobody likes to hear about their weaknesses … But other teachers will help to measure your real teaching skills by looking at your lessons.’ (Fernandez and Yoshida Citation2012, p. 225)

Short-term oriented nations may seek quick results from LS (Hofstede et al. Citation2010), probably through short-term measurable targets. Seleznyov (Citation2019) showed that such short-term results are unlikely for LS, and this may mean schools either abandon LS after a short-term experiment, or fail to pursue research themes over long time frames. Since short-term oriented nations care about status (Hofstede et al. Citation2010), teachers may not avoid the vulnerable position of teaching a research lesson and facing associated critical feedback.

In summary, the above three key dimensions from Hofstede’s framework allow us to hypothesise about how Japan’s culture might have framed the development of LS, and this may also help explain challenges LS might face when translated internationally. However, a nation with a very different profile to Japan on any other dimensions not explored in the above analysis may also face challenges when implementing LS. A close analysis of national cultural beliefs against those of Japan, using Hofstede et al.’s (Citation2010) six dimensions, may support the local implementer in anticipating which of LS’s seven components (Seleznyov Citation2018) are likely to present challenges for local schools and teachers.

Conclusion

We return now to the research questions for this paper:

How is Japanese LS adapted when implemented in international contexts and why?

How might an understanding of national culture be relevant in understanding how Japanese LS is adapted?

Evidence from international LS studies indicates there are often significant adaptations to the model when implemented in other nations: some components are missed out altogether, and several studies highlight challenges to implementing components as intended. These challenges include lack of time and space to accommodate LS process; weak teacher research skills; focus on short-term goals; accountability pressures; dearth of study material for kyozai kenkyuu; and no access to koshi support.

The complex, multi-component nature of LS suggests it would be problematic to expect full fidelity, and the ways in which international translations of LS projects have missed out, or struggled to implement components with fidelity, may be inevitable adaptations emerging from the complexities of changing practice in social contexts like schools. Unfortunately, research has not shown which components of Japanese LS advocates might reasonably adapt nor in which way, if they are seeking to achieve similar impact on pupil and teacher learning to the Japanese (Stigler and Hiebert Citation1999). Each implementer in each different national context is likely to end up treading a careful balancing act between a focus on full fidelity and possible failed implementation, and a focus on local adaptation leading to loss of intended impact.

Moreover, the interplay between different dimensions of cultural beliefs in Japan, which may well have shaped the development of LS in situ, is unlikely to be replicated in non-Japanese contexts, making successful implementation of all LS’s components more difficult. Culture shapes nations’ education systems, schools’ PD practices, and teachers’ beliefs. Three key dimensions from Hofstede’s framework allow us to hypothesise about how Japan’s culture might have framed development of LS in situ, but any significant difference between Japan’s national profile and that of the host country may make fidelity to components of LS problematic to achieve, and such challenges may leave the implementer considering considerable adaptations to the model.

Discussion and implications

In summary, the context into which LS will be implemented should be considered when deciding upon an implementation paradigm, with an understanding of the possible consequences for impact and sustainability of any adaptations selected. For the practitioner, developing an understanding of the cultural profile of the host nation, and the degree to which this profile differs to that of Japan, may help predict challenges to full implementation of LS, and enable considered planning for suitable adaptation with a view to sustainability. However, a lack of clarity about the relationship between relative degrees of adaptation to the components of Japanese LS and overall impact, will make it difficult to predict whether LS will have similar impact on teachers and pupils in its new context, as in Japan.

If a host nation has a similar cultural profile to Japan, and adopts a fidelity paradigm, the practitioner might hypothesise that fidelity to the components of LS is more feasible, as is achieving a similar impact and longevity in its new context. If on the other hand, an implementer of LS into a host nation with a similar cultural profile to Japan decides to adapt many of the components of Japanese LS, it is likely this approach may ensure longevity, but it is less clear whether it will be possible to achieve similar impact.

If a host nation has a very different cultural profile to that of Japan, and practitioners decide to seek fidelity to the components of LS, the process of implementation is likely to lead to unintended adaptations, as stakeholders struggle to manage the clash between their own cultural beliefs and practices and the components of LS. In this circumstance, the practitioner might predict that both desired impact of LS and its sustainability is less likely to be achieved. Should such a culturally different host nation focus on necessary local adaptation through implementation, it may be possible to achieve desired impact and longevity for LS, although this is by no means certain.

A consideration both of national cultural differences and of the chosen implementation paradigm, may prove useful for practitioners seeking to introduce LS into their own nation’s schools. This approach enables practitioners to weigh up the feasibility of implementing LS with fidelity, and to be cautious about expectations of impact and sustainability. Further research might seek to explore whether anticipation of challenges through Hofstede (Citation2010) six dimensions helps practitioners of LS make deliberate and successful plans for local adaptation, whilst at the same time achieving promised impact on teacher and pupil learning.

One limitation of our approach is that it does not enable us to explore how different combinations of adaptations to various LS components might impact positively or negatively on desired outcomes. Research might usefully explore which combinations of adaptations prove to be more or less impactful and sustainable, and in which contexts; for example, is adherence to the research elements of the process crucial to successful implementation of LS, as suggested by Seleznyov (Citation2018), or does this depend on the cultural profile of the host nation?

Those exploring teacher PD more broadly might also consider framing explorations of international borrowing of other PD approaches in terms of an understanding of the complexity of implementation in different cultural contexts, as exemplified through a comparison of national profiles using Hofstede’s six dimensions: are certain features of PD models implemented more easily in nations with particular cultural profiles?

Acknowledgments

With grateful thanks to Dr Aki Murata, who gave generously of her time to act as a critical friend for this paper.

References

- Abdella, A., 2015. Lesson study as a support strategy for teacher development: a case study of middle school science teachers in Eritrea. Thesis (PhD). Stellenbosch University. Available from: https://scholar.sun.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10019.1/97776/abdella_lesson_2015.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y [Accessed 15 Jun 2021].

- Akiba, M., et al. 2019. Lesson study design features for supporting collaborative teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77 (x), 352–365. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.10.012

- Albers, B. and Pattuwage, L. 2017. Implementation in education: findings from a scoping review. Available from: http://www.ceiglobal.org/application/files/2514/9793/4848/Albers-and-Pattuwage-2017-Implementation-in-Education.pdf [Accessed 05 Nov 2020].

- Alexander, R., 2001. Culture and pedagogy: international comparisons in primary education. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Baldwin, J.R., et al. 2006. Redefining culture: perspectives across the disciplines. eds. London: Routledge.

- Boylan, M., et al., 2019. Longitudinal evaluation of the mathematics teacher exchange: china-England-Final Report. Available from: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/25166/1/BRANDED-MTE%20combined.pdf [Accessed 04 Jun 2021].

- Brown, C., 2019. Using theories of action approach to measure impact in an intelligent way: a case study from Ontario Canada. Journal of Educational Change, 21 (x), 135–156. doi:10.1007/s10833-019-09353-3

- Bryk, A., 2016. Fidelity of Implementation: is It the Right Concept? Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Available at: https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/blog/fidelity-of-implementation-is-it-the-right-concept/ [Accessed 05 Nov 2020].

- Burdett, N. and O’Donnell, S., 2016. Lost in translation? The challenges of educational policy borrowing. Educational Research, 58 (2), 113–120. doi:10.1080/00131881.2016.1168678

- Cartwright, N., 2013. Knowing what we are talking about: why evidence doesn’t always travel. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 9 (1), 97–112. doi:10.1332/174426413X662581

- Chakroun, B., 2010. National qualification frameworks: from policy borrowing to policy learning. European Journal of Education, 45 (2), 199–216. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3435.2010.01425.x

- Chokshi, S. and Fernandez, C., 2004. Challenges to importing Japanese lesson study: concerns, misconceptions, and nuances. Phi Delta Kappan, 85 (7), 520–525. doi:10.1177/003172170408500710

- Datnow, A., Hubbard, L., and Mehan, H., 1998. Educational reform implementation: a co-constructed process. Research Report #5. Center for Research on Education, Diversity & Excellence. Santa Cruz: Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence.

- Dolowitz, D., 2009. Learning by observing: surveying the international arena. Policy and politics, 37 (3), 317–334. doi:10.1332/030557309X445636

- Domitrovich, C., et al. 2008. Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: a conceptual framework. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 1 (3), 6–28. doi:10.1080/1754730X.2008.9715730

- Durlak, J., 1998. Why program implementation is important. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the community, 17 (2), 5–18. doi:10.1300/J005v17n02_02

- Durlak, J. and DuPre, E., 2008. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American journal of community psychology, 41 (3–4), 327–350. doi:10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

- Fang, T., 2003. A critique of Hofstede’s fifth national culture dimension. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 3 (3), 347–368. doi:10.1177/1470595803003003006

- Fernandez, C., 2002. Learning from Japanese approaches to professional development: the case of lesson study. Journal of teacher education, 53 (5), 393–405. doi:10.1177/002248702237394

- Fernandez, C. and Yoshida, M., 2012. Lesson study: a Japanese approach to improving mathematics teaching and learning. Place. London: Routledge.

- Forsberg, E. and Román, H., 2014. The art of borrowing in Swedish assessment policies: more than a matter of transnational impact. In: A. Nordin and D. Sundberg, eds. Transnational Policy Flows in European Education. Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Fujii, T., 2014. Implementing Japanese lesson study in foreign countries: misconceptions revealed. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 16 (1), 1–18.

- Fujii, T., 2016a. Designing and adapting tasks in lesson planning: a critical process of Lesson Study. ZDM, 48 (x), 1–13. doi:10.1007/s11858-016-0770-3

- Fujii, T., 2016b. Japanese lesson study in mathematics: critical role of external experts. In: Japanese lesson study in mathematics. London: UCL Institute of Education.

- Godfrey, D., et al. 2019. A developmental evaluation approach to lesson study: exploring the impact of lesson study in London schools. Professional Development in Education, 45 (2), 325–340. doi:10.1080/19415257.2018.1474488

- Grek, S., 2013. Expert moves: international comparative testing and the rise of expertocracy. Journal of education policy, 28 (5), 695–709. doi:10.1080/02680939.2012.758825

- Groves, S., et al. 2016. Critical factors in the adaptation and implementation of Japanese lesson study in the Australian context. ZDM, 48 (4), 501–512. doi:10.1007/s11858-016-0786-8

- Harn, B., Parisi, D., and Stoolmiller, M., 2013. Balancing fidelity with flexibility and fit: what do we really know about fidelity of implementation in schools?. Exceptional Children, 79 (2), 181–193. doi:10.1177/001440291307900204

- Harris, A., Jones, M., and Adams, D., 2016. Qualified to lead? A comparative, contextual and cultural view of educational policy borrowing. Educational Research, 58 (2), 166–178. doi:10.1080/00131881.2016.1165412

- Hofstede, G., 2010. Dimension Data Matrix. Viewed 15 March 2020, https://geerthofstede.com/research-and-vsm/dimension-data-matrix/

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G., and Minkov, M., 2010. Cultures and organizations: software of the mind (Vol. 3). London: McGraw-Hill.

- Hoppe, M., 1990. A comparative study of country elites: international differences in work-related values and learning and their implications for management training and development. Unpublished Thesis. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Isoda, M., 2007. A brief history of mathematics lesson study in Japan Section 2.1:“Where did Lesson Study Begin, and how far has it come?. In: In Isoda, M. Japanese lesson study in mathematics: its impact, diversity and potential for educational improvement. Singapore: World Scientific, 8–15.

- Jones, M., 2007. Hofstede - culturally questionable?. Available at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1389&context=commpapers [Accessed 05 Nov 2020].

- Kroeber, A. and Kluckhohn, C., 1952. Culture: a critical review of concepts and definitions. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum.

- Lee, C. and Ling, L., 2013. The role of lesson study in facilitating curriculum reforms. International journal for lesson and learning studies, 2 (3), 200–206. doi:10.1108/IJLLS-06-2013-0039

- Lendrum, A. and Humphrey, N., 2012. The importance of studying the implementation of interventions in school settings. Oxford Review of Education, 38 (5), 635–652. doi:10.1080/03054985.2012.734800

- Lewis, C., 2000. Lesson Study: the Core of Japanese Professional Development. Presentation at Special Interest Group on Research in Mathematics Education, American Educational Research Association Meetings, New Orleans. Accessed 05 Nov 2020. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED444972.pdf

- Lewis, C., Perry, R., and Murata, A., 2006. How should research contribute to instructional improvement? The case of lesson study. Educational researcher, 35 (3), 3–14. doi:10.3102/0013189X035003003

- Lim, C., et al. 2011. Taking stock of lesson study as a platform for teacher development in Singapore. Asia-Pacific journal of teacher education, 39 (4), 353–365. doi:10.1080/1359866X.2011.614683

- McSweeney, B., 2002. Hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences: a triumph of faith – a failure of analysis. Human Relations, 55 (x), 89–118. doi:10.1177/0018726702551004

- Molloy, L., et al. 2013. Understanding real-world implementation quality and “active ingredients” of PBIS. Prevention science, 14 (6), 593–605. doi:10.1007/s11121-012-0343-9

- Mouritzen, P. and Svara, J., 2002. Leadership at the apex: politicians and administrators in Western local governments. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Murata, A., 2011. Introduction: conceptual overview of lesson study. In. Lesson study research and practice in mathematics education. Springer Netherlands, 1 (12), 1–11.

- Ochs, K., 2006. Cross‐national policy borrowing and educational innovation: improving achievement in the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Oxford Review of Education, 32 (5), 599–618. doi:10.1080/03054980600976304

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H., and Kemmelmeier, M., 2002. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128 (1), 3–72. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3

- Perry, R. and Lewis, C., 2009. What is successful adaptation of lesson study in the US?. Journal of educational change, 10 (4), 365–391. doi:10.1007/s10833-008-9069-7

- Schaper, A., McIntosh, K. and Hoselton, R., 2016. Within-year fidelity growth of SWPBIS during installation and initial implementation. School Psychology Quarterly, 31(3), p.358

- Seleznyov, S., 2018. Lesson study: an exploration of its translation beyond Japan. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 7 (3), 217–229. doi:10.1108/IJLLS-04-2018-0020

- Seleznyov, S., 2019. Lesson study beyond Japan: evaluating impact. International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies, 8 (1), 2–13. doi:10.1108/IJLLS-09-2018-0061

- Sherer, J. and Spillane, J., 2011. Constancy and change in work practice in schools: the role of organizational routines. Teachers College Record, 113 (3), 611–657.

- Søndergaard, M., 1994. Research note: hofstede’s consequences: a study of reviews, citations and replications. Organization studies, 15 (3), 447–456. doi:10.1177/017084069401500307

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. and Waldow, F., eds., 2012. World yearbook of education 2012: policy borrowing and lending in education. Oxford: Routledge.

- Stigler, J. and Hiebert, J., 1999. The teaching gap: best ideas from the world’s teachers for improving education in the classroom. New York: Free Press.

- Takahashi, A., 2014. The role of the knowledgeable other in lesson study: examining the final comments of experienced lesson study practitioners. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 16 (1), 1–17.

- Telzrow, C., McNamara, K., and Hollinger, C., 2000. Fidelity of problem-solving implementation and relationship to student performance. School Psychology Review, 29 (3), 443–461. doi:10.1080/02796015.2000.12086029

- Tobler, N., Ringwalt, C., and Flewelling, R., 1994. How effective is drug abuse resistance education? A meta-analysis of project DARE outcome evaluations. American Journal of Public Health, 84 (9), 1394–1401. doi:10.2105/AJPH.84.9.1394

- Tomlinson, S., 2005. Education in a post welfare society. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Vavrus, F. and Bartlett, L., 2012. Comparative pedagogies and epistemological diversity: social and materials contexts of teaching in Tanzania. Comparative Education Review, 56 (4), 634–658. doi:10.1086/667395

- Verhoef, N., et al. 2015. Professional development through lesson study: teaching the derivative using GeoGebra. Professional development in education, 41 (1), 109–126. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.886285

- Wake, G., Foster, M., and Swann, M., 2013. Bowland maths lesson study project report. http://www.bowlandmaths.org.England/lessonstudy/report.html [Accessed 15 September 2021]

- White, A., Lim, C., and Chiew, C., 2005. An examination of a Japanese model of teacher professional learning through Australian and Malaysian lenses. In Australian Association for Research in Education 2005 conference proceedings. Australia.

- Wigelsworth, M., Humphrey, N., and Lendrum, A., 2012. A national evaluation of the impact of the secondary social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL) programme. Educational psychology, 32 (2), 213–238. doi:10.1080/01443410.2011.640308

- Wijekumar, K., Meyer, B., and Lei, P., 2013. High-fidelity implementation of web-based intelligent tutoring system improves fourth and fifth graders content area reading comprehension. Computers & education, 68 (2013), 366–379. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.021

- Williams, J., Ryan, J., and Morgan, S., 2014. Lesson study in a performative culture. In: O. McNamara, J. Murray, and M. Jones, eds. (2013). Workplace learning in teacher education. Dordrecht: Springer, 151–167.

- Wolthuis, F., van Veen, K., de Vries, S. and Hubers, M.D., 2020. Between lethal and local adaptation: Lesson study as an organizational routine. International journal of educational research, 100, p.101534

- Xu, H. and Pedder, D., 2014. Lesson study: an international review of the research. In: P. Dudley, ed. Lesson Study. Routledge: Oxford, 29–58.