ABSTRACT

We applied the path to intended violence (PTIV) [Calhoun, F. S., & Weston, S. W. (2003). Contemporary threat management: A practical guide for identifying, assessing, and managing individuals of violent intent. Specialized Training Services] model and the Terrorist Radicalization Assessment Protocol (TRAP-18; [Meloy, J. R. (2017). The TRAP-18 manual version 1.0. Washington, DC: Global Institute of Forensic Research]) to study the case of a lone-actor jihadist who carried out a fatal shooting at a joint Army-Navy recruiting center in Little Rock, Arkansas, on 1 June 2009. The PTIV model examines incidents using six progressive stages: grievance; violent ideation; researching and planning; preparation; probing and breaching; and attack [Calhoun, F. S., & Weston, S. W. (2003). Contemporary threat management: A practical guide for identifying, assessing, and managing individuals of violent intent. Specialized Training Services]. The TRAP-18 is a structured professional judgment tool and comprises 18 behavior-based warning signs for terror incidents. The findings from the retroactive application of the TRAP-18, in this case, show that in the week before the attack, the perpetrator exhibited 5 of the 8 proximal warning behaviors and 5 of the 10 distal warning behaviors. The retroactive application of the TRAP-18 and PTIV to cases of targeted violence assists with identifying a timeline of behaviors, which in turn provides insight into the pathway to violence and warning signs that someone may be a threat of violence.

Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad (Carlos Bledsoe) a Tennessee-born lone-actor jihadist (herein, referred to as AMM) carried out a fatal shooting at a joint Army-Navy recruiting center in Little Rock, Arkansas, on 1 June 2009. AMM, 23, fatally shot Private William Andrew Long and seriously wounded Private Quinton I. Ezeagwula, while they were standing in uniform outside the Army-Navy Career Center in Little Rock, AR (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). AMM plead guilty to capital murder, attempted capital murder, and 10 counts of unlawful discharge of a weapon from a vehicle on 25 July 2011. He received a life sentence without the possibility of parole on the capital murder charge and was also given 11 more life sentences for the remaining charges. He also received an additional 15 years, for each of the charges involving a firearm, which were to all run consecutively (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). As highlighted by a report on the case published by the National Threat Assessment Center, AMM’s attack was part of his personal campaign of violence, during which he planned to attack Jewish and military targets in retaliation for American actions in Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, and Bagram Air Base (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). Prior to this attack, AMM demonstrated various behaviors that were observed by family and peers, and when analyzed retroactively shows a detailed path to radicalization and violence.

In a recent review, Kenyon et al. (Citation2021) highlighted that ‘the time lone actors dedicate to attack planning and preparation, their social ties to like-minded others, their increased internet use and limited attention paid to operational security measures all mean early-detection and prevention of this threat is distinctly possible’ (p. 20). This time that lone actors dedicate to the planning and preparation for their attack should be encouraging to security and law enforcement agencies, particularly when the person of concern is assessed using tools such as the Terrorist Radicalization Assessment Protocol which enables professionals to prioritize cases of possible lone-actor cases for monitoring or risk management (Meloy & Genzman, Citation2016). Goodwill and Meloy (Citation2019) have highlighted that there have been six instruments developed that professionals can use for the purposes of assessing the risk or threat of terrorist violence. These include the Extremism Risk Guide (ERG 22+), Islamic Radicalization (IR-46), Identifying Vulnerable People (IVP), Multi-Level Guidelines (MLG Version 2), Terrorist Radicalization Assessment Protocol (TRAP-18), and the Violent Extremism Risk Assessment (VERA Version 2 Revised) (Lloyd, Citation2019).

Previous case studies which have utilized the TRAP-18 retroactively

A recent systematic review identified studies which have utilized the TRAP-18 either prospectively (operational use) or retroactively or studies which have investigated the validity and reliability of the TRAP-18 (Allely & Wicks, Citation2022). In their systematic review, Allely and Wicks (Citation2022) found a total of 17 relevant articles which consisted of 6 case studies and 11 empirical articles. A brief overview of some of these studies will now be discussed. We recommend readers refer to this systematic review as it includes detailed tables of all the studies and their findings.

As mentioned above, there have been some published case studies which have utilized the TRAP-18 retroactively (Böckler et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Erlandsson & Reid Meloy, Citation2018; Meloy & Genzman, Citation2016; Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015). The cases included the case of the Frankfurt Airport attack in 2011 in which a 21-year-old man shot several US soldiers, murdering two US airmen and severely wounding two others (Böckler et al., Citation2015); the case of 24-year-old Anis A. who killed 12 and injured more than 50 people during a terror attack on 19 December 2016, where he drove a truck into a Christmas market in Berlin (Böckler et al., Citation2017); the case of Anton Lundin Pettersson (the Kronan School attack) who murdered three people and injured another seriously on the 22nd of October 2015 (Erlandsson & Reid Meloy, Citation2018); the case of Anders Breivik who killed 77 people in 2 separate attacks, a bombing in Oslo and a mass murder utilizing two firearms on the island of Utøya on 22 July 2011 (Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015); and the case of a US Army psychiatrist and jihadist, Malik Nidal Hasan, who committed mass murder at Fort Hood, Texas, in November 2009 (Meloy & Genzman, Citation2016).

In four of these five case studies, the lone actors were evaluated on the full TRAP-18. For the case study paper on Anders Breivik (Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015) and the case study paper on Anis. A (Böckler et al., Citation2017) only the eight warning behaviors were investigated. In the Frankfurt Airport attack (2011), six out of the eight (75.0%) proximal warning behaviors were present. In the Christmas market in Berlin attack (2016), five out of the eight (62.5%) proximal warning behaviors were present. In the Kronan School attack (2015), seven out of the eight (87.5%) proximal warning behaviors were present. In the Bombing in Oslo and mass murder on the island of Utøya (2011), six out of eight (75.0%) proximal warning behaviors were present. Lastly, in the Fort Hood, Texas attack (2009), six out of eight (75.0%) proximal warning behaviors were present. Turning now to the distal characteristics that were present in each of the three case studies where the full TRAP-18 was applied, in the Frankfurt Airport attack (2011), 9 out of the 10 (90%) distal characteristics were present. In the Kronan School attack (2015), 8 out of the 10 (80%) distal characteristics were present. Lastly, in the Fort Hood, Texas attack (2009), 7 out of 10 (70%) distal characteristics were present. Looking at the percentage of indicators present across the full TRAP-18 in the three cases where this was carried out, the following was found. In the Frankfurt Airport attack (2011), 15 out of the 18 (83.33%) were present. In the Kronan School attack (2015), 15 out of the 18 (83.33%) were present. Lastly, in the Fort Hood, Texas attack (2009), 13 out of 18 (72.22%) were present. Across the five case studies, there was some overlap in the items for which no evidence was present. Specifically, for all five cases, there was no evidence present for one of the proximal warning behaviors, Directly Communicated Threat. In terms of all the other indicators for which there was no evidence present, there was no evidence for proximal warning behavior, Novel Aggression in four out of the five cases. There was also no evidence for proximal warning behavior, Energy Burst, in only one case. Interestingly, the distal characteristic, Criminal Violence (History) was identified as absent in all three cases where the full TRAP-18 was applied. Failure to Affiliate with an Extremist Group was another distal characteristic that was identified as being absent in two of the three cases where the full TRAP-18 was applied. Lastly, Mental Disorder was a distal characteristic that was found to be absent in only one of the three cases which applied the full TRAP-18 assessment.

Overall, these findings indicate that in these five cases, most of the items included in the TRAP-18 framework appear to be relevant and descriptive of the characteristics of lone-actor terrorists. However, the case study findings, to date, appear to suggest that certain indicators of the TRAP-18 may not be applicable to most lone actors including Novel Aggression, Directly Communicated Threat, Criminal Violence, Failure to Affiliate with an Extremist or Other Group, and Mental Disorder. The lack of criminal violence is particularly interesting due to this factor’s association with the risk of terrorist recidivism among those arrested and prosecuted for violent offenses or attempts to conduct violent attacks. Furthermore, there has been significant reporting on ISIS’ intentional recruitment of violent offenders in Europe (Basra & Newmann, Citation2017). Moreover, increased attention has been placed on radicalization and recruitment within prison facilities among populations of both violent and nonviolent offenders. Although the study finds that directly communicated threats may not be relevant to lone actors, the lack of presence of this within the five cases may reflect a subject’s desire to maintain operational security.

In their case study on the 2011 Frankfurt, Germany, airport attack, Böckler et al. (Citation2015) drew attention to this individual's very short and accelerated pathway to violence. It appears that this individual's radicalization process started when he was about 16 or 17 years old (when he was in 10th grade at school) but his actual pathway to violence, which was primed by his immersion in Salafist ideology, was just a day or two. Not weeks, months or even years as in many other cases. This particular case study highlights to threat assessment professionals that there is a lack of time to find and then interdict along the late stages of the pathway (planning, preparation, implementation) when compared to the proximal warning behaviors (fixation on a cause and identification) which still appear to take months, and in some cases even years, to completely crystalize or develop (Böckler et al., Citation2015). The case study explored by Erlandsson and Reid Meloy (Citation2018) revealed that the individual had no documented history of mental illness and also no clear external markers for mental illness. However, there are some indications of depressive disorder in Pettersson for a couple of months preceding the attack; he also had thoughts of suicide (he had also engaged in self-injury in the past). Police investigation of material saved on his computer, coupled with information obtained from the people in his surroundings, revealed that Pettersson had been socially withdrawn and that he experienced himself as different. Two weeks prior to carrying out his attack, he completed an online test for depression and subsequently carried out a search online for information about depressive disorders. Following this, he looked at live suicide videos online and evidence also shows that he went through a page belonging to a help organization for people with suicidal thoughts. The information this individual saved to his computer was also studied. There were significant amounts of material which contained content regarding topics such as hopelessness, being misunderstood, self-hate, violence, and death. This case study supports the belief that these types of attacks ‘may be motivated in part by troubled individuals whose psychopathology is magnified by social and economic volatility, and the political movements, often extreme, that rise to address them’ (Erlandsson & Reid Meloy, Citation2018, p. 1926). These individuals do not work in complete isolation or in a vacuum as the terms ‘lone-actor’ or ‘lone-wolf’ would imply. These terms give rise to the notion that the individual is stealthy, skillful, and operating entirely in isolation which they are typically not (Schuurman et al., Citation2019 as cited in Erlandsson & Reid Meloy, Citation2018).

An important point to take into strong consideration in threat assessment was raised by Meloy, Habermeyer, et al. (Citation2015) who state that a precise mental health diagnosis has ‘little incremental validity when threat assessing a person who warrants concern that he might perpetrate an act of intended or targeted violence, but greater relevance when threat managing a case’ (p. 165). Studies have suggested that what is important to assess in someone presenting with, for example, psychosis, is the level of positive symptoms and their ‘relationship to the motivation for violence’ (e.g. Douglas et al., Citation2009; Hoffmann et al., Citation2011; see Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015). In their case study paper (on the case of the perpetrator of the Norway attacks on 22 July 2011), Meloy, Habermeyer, et al. (Citation2015) note some of the potential limitations in their study – limitations which would apply to most, if not all, analysis of retrospective case studies. For instance, relying on multiple sources of information necessitating the need to fact check and the possibility of hindsight and confirmatory bias. It is easier to identify warning behaviors retroactively after the attack has occurred than it would be to identify them prospectively (Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015).

There is an increasing number of empirical studies which have applied the TRAP-18 assessment to evaluate terrorist incidents retroactively (e.g. Böckler et al., Citation2021; Brugh et al., Citation2020; Challacombe & Lucas, Citation2019; García-Andrade et al., Citation2019; Goodwill & Meloy, Citation2019; Meloy et al., Citation2019, Citation2021; Meloy & Gill, Citation2016; Meloy, Roshdi, et al., Citation2015). Meloy and Gill (Citation2016) found that the TRAP-18 appears to have utility as an investigative template and organizing tool for threat assessment professionals. In another study, Meloy, Roshdi, et al. (Citation2015) found the TRAP-18 to have good-to-excellent interrater reliability and content validity when applied to a small sample of individual terrorists in Europe – both lone actors and members of autonomous cells (Meloy, Roshdi, et al., Citation2015). The TRAP-18 behaviors are considered patterns rather than being discrete variables (Meloy, Citation2017). For a review of articles which have used the TRAP-18 either to single case studies or larger samples see Allely and Wicks (Citation2022). The retroactive use of these tools can assist in creating a detailed evidence-base of the temporal sequencing of warning behaviors displayed in the days, weeks, months, and even years leading up to the attack, further aiding to prevention efforts and early identification of individuals on the pathway to violence.

The terrorist radicalization assessment protocol (TRAP-18)

The TRAP-18 (Meloy & Gill, Citation2016; Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015; Meloy, Citation2017) comprises 18 behavior-based warning signs for terror incidents. Eight of the 18 behavior-based warning signs are proximal characteristics and ten are distal characteristics. The proximal characteristics are typically displayed closer in time to the incident. The ten distal characteristics are those which developed over time and are more distantly related to the act for which there is a concern (Meloy & Gill, Citation2016; Meloy, Citation2017).

It is stressed by the developer of the TRAP-18 that the definitions of each of the 18 behavior-based warning signs which will be outlined below are abbreviated and they should not be used as the basis for threat assessment without training in the use of structured professional instruments and the TRAP-18 manual (Meloy, Citation2017). The eight proximal warning behaviors (Meloy & Gill, Citation2016; Meloy, Citation2017) include (1) pathway (attack research, planning, or implementation), (2) fixation (abnormal preoccupation on an individual or cause), (3) identification (self-identification as a fighter/warrior/agent of change), (4) novel aggression (an initial violent action which is unrelated to the target), (5) energy burst (an increase in the frequency or range of behaviors which are related to the targeted individual or cause leading up to a violent incident), (6) leakage (communication to an outside party of the individual’s intent for violence which can be unconscious or conscious), (7) last resort (where the person feels that there is no other way to solve the grievance other than violence, and for that violence to be now – they feel violence is their only option), and (8) directly communicated threat (communication of violence to target or law enforcement before action) (Meloy et al., Citation2012; Meloy & Gill, Citation2016; Meloy & O'toole, Citation2011; Silver et al., Citation2018). In the TRAP-18, the ten distal characteristics focus on the individual’s lone-actor status. The 10 distal characteristics consist of: (1) personal grievance and moral outrage (confluence of factors shaping an individual to have a strong viewpoint about the targeted individual or cause), (2) framed by an ideology (justifying beliefs for action), (3) failure to affiliate with an extremist group (failure/rejection of individual with desired terrorist or other group), (4) dependence on virtual community (communication using social media and other online vectors with like-minded individuals), (5) thwarting of occupational goals (setback/failure in academic/life pursuits), (6) changes in thinking and emotions (thinking pattern becomes absolute and simplistic), (7) failure of sexual-intimate pair bonding (individual fails to sexually or intimately bond), (8) mental disorder (historic or present major mental health disorder), (9) greater creativity and innovation (innovative terrorist action or process imitated by others), and (10) criminal violence (past criminal history) (Meloy & Gill, Citation2016). The developers of the TRAP-18 view it as being a complementary tool to other well-established instruments.

The path to intended violence model (Calhoun & Weston, Citation2003)

A practical and well-grounded model for threat assessment, referred to as the path to intended violence (PTIV) model, was developed by Calhoun and Weston (Citation2003). There are six progressions to this path including: holding a grievance (e.g. a perceived sense of injustice, a threat or loss, a need for fame, or revenge), ideation (considering the only option to be violence, discussing one's thoughts with others, or modeling oneself after other assailants), research/planning (collecting information specific to one’s target, or stalking the target), preparations (e.g. collating one’s costume, weapon(s), equipment, transportation, or engaging in ‘final act’ behaviors), breach (e.g. assessing levels of security, devising ‘sneaky or covert approach’), and attack (Calhoun & Weston, Citation2003). The PTIV model has been retroactively applied to a number of other contemporary perpetrators of public mass shootings (Allely & Faccini, Citation2017, Citation2019; Faccini, Citation2016; Faccini & Allely, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Schildkraut et al., Citation2022). For instance, Allely and Faccini (Citation2017) carried out a case study and retroactively applied the PTIV model to Elliot Rodger's (herein referred to as ER), who killed 6 people and injured 14 others (by gunshot, stabbing, and vehicle ramming) near the campus of the University of California in Santa Barbara (UCSB) on 23 May 2014. One of the aspects of this case that Allely and Faccini (Citation2017) identified when they applied the PTIV to this case was that ER’s narcissistic rage and its overlap with the PTIV accounted for his attack in May 2014. Essentially, they argued that his narcissistic rage (that encompassed his sense of injustice and need for revenge) propelled him onto the PTIV. In another paper, Faccini and Allely (Citation2016a) retroactively applied the PTIV to the case of Anders Breivik (herein referred to as AB) who killed eight people by detonating a van bomb at Regjeringskvartalet in Oslo, then killed 69 participants of a Workers’ Youth League (AUF) summer camp in a mass shooting on the island of Utøya on 22 July 2011. What the findings suggested in this case was that it was not AB’s narcissistic personality disorder per se that was critical in him carrying out his attacks but the four factors, namely, narcissistic decompensation, its overlaps with step one on the path or grievance, the violence-only decision (step 2 of the path), and then researching, preparing, planning, breaching security leading to the attack of others (Faccini & Allely, Citation2016a).

Aims of the present case study

In this case analysis paper, we applied the PTIV and the TRAP-18 (Meloy, Citation2017) in order to study the case of Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad (Carlos Bledsoe) a lone-actor jihadist (herein, referred to as AMM) who carried out a fatal shooting at a joint Army-Navy recruiting center in Little Rock, Arkansas, on 1 June 2009. The aim of the present case study is to retroactively apply the TRAP-18 and PTIV to the case of AMM. The retroactive use of these tools can assist in creating a detailed evidence-base of the temporal sequencing of warning behaviors displayed in the days, weeks, months, and even years leading up to the attack, further aiding to prevention efforts and early identification of individuals on the pathway to violence.

Method

All of the information that we found and used in this case study paper on the case of AMM was obtained from open-source materials. In order to identify documents or academic peer-reviewed articles relating to the case of AMM we first conducted a search on Googlescholar using the following search terms: ‘Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad’ or ‘Abdulhakim Muhammad’ or ‘Carlos Bledsoe’. From this search we identified seven texts relating to the case (Bergen, Citation2011; Bergen et al., Citation2011; Bergen & Hoffman, Citation2010; Etter, Citation2015; Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014; Hamm & Spaaij, Citation2017; Zierhoffer, Citation2014). On 8th June 2022, we also carried out a search of the databases for relevant articles on the case of AMM. Six databases were searched including SalfordUniversityJournals@Ovid; Journals@Ovid Full Text June 07, 2022; APA PsycArticles Full Text; APA PsycExtra 1908 to May 09, 2022; APA PsycInfo 1806 to May Week 5 2022 and, lastly, Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions 1946 to June 07, 2022. The following search criteria were entered into the databases and searched by title: (‘Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad’ or ‘Abdulhakim Muhammad’ or ‘Carlos Bledsoe’ or ‘Army-Navy recruiting center’).m_titl. This returned only one academic peer-reviewed article which was relevant (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). This paper identified in the database search was one of the key sources for this case study paper on AMM. One of the key reasons for this was that Gartenstein-Ross not only conducted field research in Little Rock, Arkansas but also read all available court documents and media reporting related to the attack by AMM before carrying out the field research. During the field research, Gartenstein-Ross made special notes of figures who appeared to have had a special insight into AMM and the attack. It was these figures that Gartenstein-Ross interviewed during the field research. Gartenstein-Ross interviewed AMM’s father by telephone and when in Little Rock, an interview was carried out with prosecutor Larry Jegley; Lt. Carl Minden of the Pulaski County detention facility where AMM was held; guards at that facility who worked there during the time that AMM was incarcerated; and Jim Hensley, an attorney who was part of the defense team. Gartenstein-Ross also visited the detention facility itself and was granted access to the administrative segregation wing where AMM had been held and was able to gain access to the files that the prosecution used in this case (see Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014).

In the paper, we apply the PTIV model and the TRAP-18 to the case of AMM. The information identified for the application of the PTIV model for the case of AMM (and the temporal sequencing of events it records) were used to retroactively apply the TRAP-18. Both authors read all official or academic peer-reviewed material that was publicly available regarding the case. Both authors completed the coding of the TRAP-18 independently and then conducted consensus coding.

Case study of AMM

Early life

AMM was born as Carlos Bledsoe on 9 July 1985, and he was brought up in Memphis, Tennessee. He was raised by a middle-class Baptist family. His family operated a tour company which was called ‘Twin City Tours’. When he was eight years of age, AMM began to assist the family business. Melvin Bledsoe (AMM’s father) said that the family company played a significant role in AMM’s upbringing. In 2003, AMM graduated from high school and went to college at Tennessee State University in Nashville. His plan was to obtain a degree in business administration and eventually run the tour company – his family business (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014).

As a juvenile, AMM had many documented instances of aggression and threats of violence toward others in and out of the school environment. It is alleged that AMM was a member of a gang and was reported to have received occasional suspensions from school due to fighting during middle school. In addition to engaging in violent behavior on school grounds, AMM also has a record with the Shelby County Sheriff’s Office for making threats of violence toward others, unlawful possession of weapons, and destroying property (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). During his competency evaluation following the Little Rock, Arkansas incident, AMM admitted to using guns and knives during altercations in his teen years (Gray, Citation2010).

AMM’s record of violent behavior extended past his school years into late teen years and early adulthood, resulting in law enforcement contacts and criminal charges. AMM was charged with unlawful possession of a weapon (brass knuckles) in 2003 after an incident in which AMM hit a woman’s car window while wearing chrome-plated brass knuckles and threatened to kill her after she struck his vehicle during a traffic accident. Due to his juvenile status, this case was processed non-judicially. In another incident in February of 2004, he was arrested and criminally charged with drug and weapons possession after an equipment violation traffic stop in which officers observed a loaded SKS rifle, two shotguns, two shotgun shells, a switchblade, and an ounce of marijuana. This criminal charge was later reduced to ‘possession of a prohibited weapon (switchblade)’ and was later expunged on 21 June 2004 (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015) after a plea deal was made detailing that he would serve one year of probation and on the condition that he would avoid further legal trouble (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014).

In 2004 AMM began to explore other religions including Judaism where he reported feeling unwelcome due to being African American. In December of that year, he converted to Islam and ceased alcohol and drug use. AMM’s family reported markable changes in behavior including not engaging in activities he previously enjoyed, becoming more argumentative with relatives during discussions of religion, allowing his dog to run away, and taking down pictures of Martin Luther King Jr. that he had in his bedroom since childhood (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM is reported to have attempted to convert family members to Islam, which elicited anger from his father. In 2005, AMM reportedly dropped out of college and lived in several apartments in which he failed to pay rent, resulting in legal proceedings against him. It was during this time that AMM was reported to have difficulty maintaining employment, which he attributed to anti-Muslim beliefs, disregarding an instance of being caught sleeping in his car during one job (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015).

Application of the PTIV in the case of AMM

The PTIV model, which was developed by Calhoun and Weston (Citation2003), was applied to the case of AMM.

Step 1: grievance

The first step on this path involves an individual having personal (arises or aggravated from mental illness) and/or political grievances (Calhoun & Weston, Citation2003). AMM engaged in many leakage behaviors leading up to the attack that clearly outlined his grievance or motivation for the incident. In 2009, AMM posted a video online that outlined his plans to attack Jewish and military targets in retaliation of the Americans’ actions against Muslims such as Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, and Bagram Air Base (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). When asked about mental health during his court-ordered competency evaluation following the incident, AMM stated that he shot the soldiers ‘not due to mental illness, but due to obligation. It is a religious belief’ and emphasized that his actions were directly tied to his theological views (Gray, Citation2010). The evaluator for this competency evaluation included a letter to Judge Wright that AMM authored where he plead guilty to all charges pressed against him and stated ‘I wasn’t insane or post traumatic, nor was I forced to do this act. Which I believe it is justified according to Islamic Laws and the Islamic Religion Jihad to fight those who wage war on Islam and Muslims’ (Gray, Citation2010). Within this competency evaluation, AMM expressed deep hatred toward the United States, and accused United States Military Personnel of ‘target shooting the Koran’ and ‘pissing on the Koran’ and raping Muslim women and children (Gray, Citation2010). Throughout the entirety of the evaluation, AMM consistently tied his ideological beliefs to the motivation for the attack, using his religious views to defend the act of violence, and showing a lack of remorse for the event, even stating that he ‘would have shot more soldiers had there been more in the parking lot’ (Gray, Citation2010).

Step 2: violent ideation

The second step, ideation, details an individual’s belief that the only option for resolving their grievance is through violent means. They may begin to engage in leakage behaviors such as sharing their violent thoughts with others, and may take a particular interest in perpetrators of past acts of violence and can begin to identify with them (Calhoun & Weston, Citation2003). Having known individuals of Muslim faith during childhood, Muhammad began to experiment with Islam. While AMM was visiting a Mosque in Nashville, members of the congregation asked AMM how long had been practicing Islam and were reportedly enthusiastic upon hearing that Muhammad was not currently practicing but was interested in the faith. AMM reported feeling ‘drawn and amazed’ by salah, the congregational prayer. He was given a translation of the Qur’an and other books (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). He read books, watched movies about Malcolm X, and attended a speech by Minister Louis Farrakhan (the leader of the Nation of Islam) to learn more about Islam and in December 2004, he converted to Islam. Specifically, he adhered to the philosophy of the Sunni sect. For instance, he stopped drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana. He also spent a lot of his time in Nashville’s Somali community (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015).

In 2004, when he was 19 years of age, AMM took his shahadah (the declaration of faith) at a mosque in Memphis (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). He would also attend prayers at the Islamic Center of Nashville. At the start of the fall 2005 semester, he dropped out of college (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM stated that, at the time of the attack, he ascribed to an interpretation of Islam that is best described as Salafi-jihadi. Gartenstein-Ross (Citation2014) makes the following statement regarding this: ‘By Salafi, I mean that he adhered to an austere religious methodology that seeks to re-create Islam as it was supposedly practiced by the Prophet Muhammad and the first three generations of Muslims. The term jihadi refers to the belief that violence should be undertaken in purifying Islam in this manner. Although the term jihadi is controversial among terrorism researchers, in large part because it is derived from the religious term jihad, it has the benefit of being an organic term, the way those within the movement refer to themselves’ (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014, pp. 114–115). There were a number of other things that AMM adopted that were consistent with a Salafi practice (e.g. trying to grow a beard). AMM also started to roll his pants legs up above his ankles which is often associated with Salafism. He started chewing on a miswak which is a stick that cleans teeth – something that the Prophet Muhammad is reported to have done. On 29 March 2006, he also legally changed his name from Carlos Bledsoe to Abdulhakim Mujahid Muhammad – providing further evidence of his rejection of his old identity and allowing Salafism to define his new identity (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014).

By the time he had converted to Islam, AMM had already determined his desire to engage in an act of violence. However, he never revealed or leaked his extremist beliefs to anyone (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM left the U.S. for Aden in Yemen on 11 September 2007. Before he left, the imam of Masjid Furooq in Nashville wrote a letter to the Yemen Al Khair Institute on AMM’s behalf saying that he ‘‘seeks knowledge’’ of Islam which is why he wanted to go to Yemen (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). His family tried to get him to remain in the US as they were concerned that he may become involved in radical activities. He claimed he was going to Yemen because he wanted to learn Arabic and visit Mecca which is an Islamic holy site in Saudi Arabia. AMM signed a one-year contract to teach English at the British Academy where he would earn $300 per month in order to support his move. The school was a recruiting tool to radicalize westerners – something his family later learned. AMM informed his sister before leaving the U.S., that he was planning to get married while he was in Yemen and live in Saudi Arabia eventually. During his time in Yemen, the emails that he sent to his sister became increasingly more and more religious and he continued to try and convert her to Islam (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015).

As mentioned earlier, AMM self-identified as Salafi by the time he left the U.S. and had begun practicing intently, adopting the customs, mores, and rules of the faith. However, it appears that it was not until his time in Yemen that he came to embrace the need to undertake religious violence (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). While in Yemen, AMM’s interests in violent extremism were nurtured by the contacts he made with others who shared those interests (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM placed political rage at the core of his explanation for the attack, expressing his anger over U.S. foreign policy while simultaneously tying in his perceived religious obligation (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). AMM expressed his outrage and displeasure of the news reports of the maltreatment of Muslims by U.S. soldiers and spoke about his experiences with Afghan child refugees (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). He believed there was a religious obligation to undertake violence – he embraced the need for violent action (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014).

AMM moved from Aden to Yemen’s capital city, Sana’a, in November 2007. When there he taught English classes while enrolled in Arabic courses. AMM married one of his English class students, another teacher, in September of 2008, selling his car in the U.S. to pay the dowry (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). On 14 November 2008, AMM was arrested in Yemen at a border checkpoint while trying to travel to the Federal Republic of Somalia. His visa to Yemen had expired and he was in possession of a fake Somali passport. As a result, he was detained. Later, AMM claimed that he wanted to travel to Somalia in order to be around like-minded individuals who shared the desire to commit acts of terrorism against Jewish and American targets. He was particularly interested in training on how to make explosives and car bombs (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM boasted that his attack would have been more successful had he undergone this training (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014).

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) suspected that AMM may have ties to terrorism after discovering that he had been in possession of instructional materials for the building of explosives, home-made silencers, and videos of militants during an arrest. While the agent from the FBI Nashville field office was conducting an interview with AMM in Yemen, AMM requested that the agent assist him in being released from the prison. When he was not released, he reportedly felt abandoned by the U.S. government. The radicals he met in prison encouraged that belief and told him that the U.S. had deserted him and that they were the only ones who cared about him. According to AMM, it was at this time that he began to plan a campaign of violence against Jewish and American military targets. AMM’s parents were informed two weeks later of his arrest by his wife in Yemen. Upon learning this, AMM’s parents contacted their congressional representative who subsequently contacted the U.S. Department of State on the behalf of AMM. AMM was subsequently released and on 29 January 2009, he was sent back to the U.S. His wife stayed in Yemen (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015).

Step 3: researching and planning

The third step towards intended violence is where the individual collates information related to the intended target(s) (Calhoun & Weston, Citation2003). In the case of AMM, he began planning the details by conducting research online to identify and harden potential targets and deciding on his final plan to assassinate Jewish targets and attack military recruiting centers in the Southeast, mid-Atlantic, and Northeast areas of the U.S. Towards the end of May 2009, AMM’s sister spoke with him about his new position in the family business and he seemed excited. However, on 28 May 2009, he posted a video online where he is seen discussing plans to attack Jewish and military targets in retaliation for the actions of Americans against Muslims. In the video, he describes his anger about the actions of the American in Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib, and Bagram Air Base – as well as his anger at other things (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015).

Step 4: preparation

The preparation step includes obtaining all the equipment in order to carry out the planned attack. The preparation step can be where the individual obtains the weapon(s), the costume of choice, transportation, supplies, and potentially fulfilling ‘final act’ deeds (Calhoun & Weston, Citation2003). AMM initiated planning for his attack in Little Rock, AR. Muhammad began to prepare for his attack in Little Rock, Arkansas by identifying targets and purchasing necessary supplies. His purchase of guns and ammunition took quite a while due to his budget which was limited (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). In his preparation for an attack, AMM purchased guns and a significant amount of ammunition. In early May 2009, he purchased a .22 rifle with a laser sight at Walmart to test the security measures put in place for suspicious firearm purchases, such as questioning or purchase holds which did not happen (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014; National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM bought a semiautomatic handgun, a week later, from a newspaper advertisement. He later got in touch with a man to get information on where he would be able to buy ammunition. He also purchased a second-hand Russian-made semiautomatic assault rifle from another individual and he completed this transaction in a parking lot. Concerned that the FBI was monitoring him, AMM purchased used guns from individuals to attempt to avoid detection through federal background checks (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM refused to use credit cards to purchase any of these supplies (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). Therefore, he was adhering to Islam’s prohibition on the accrual and payment of interest (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). AMM explained that he ‘trained’ for his attack at empty construction sites where he practiced his marksmanship, specifically to practice shooting people.

Step 5: probing and breaching

This fifth step is when the individual assesses the level of security in the location they are planning on carrying out their attack (Calhoun & Weston, Citation2003). In January 2009, he was deported back to the U.S. For approximately three months, he lived with his family in Memphis and then moved to Little Rock. To support him, his family gave him a job with Twin City Tours in Little Rock. The family company had since expanded to that region. AMM had formulated the intention to carry out an attack in the U.S., while incarcerated in Yemen. He started to develop a plan of action (recruiting centers and Jewish organizations being his planned targets) when he moved to Little Rock. Some of the locations for an attack that he considered included: Little Rock, Memphis, Nashville, Florence, Kentucky, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and D.C. (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). Three days leading up to the attack on the Army-Navy Recruiting Center, AMM attempted to attack six other targets, all of which were unsuccessful. On 30 May 2009, just passed midnight, AMM fired 10 shots from a .22 rifle at the home of his first target, a rabbi in Little Rock, AR, driving away and continuing his plan of violence 135 miles away in Memphis, TN. Around 3:00 AM, AMM arrived at the home of a second rabbi, but was concerned about being reported by neighbors and did not fire on the second rabbi’s home. The next day, 31 May 2009, he traveled another 215 miles to Nashville, TN and went to the home of a third rabbi but did not attack. He then drove to a Jewish community center in Nashville. He did not attack this fourth target because of the presence of children at the center. Later that day, he drove 260 miles to Florence, KY and approached a military recruiting center. However, because it was a Sunday, it was closed. He made the decision to return to Nashville, so drove 215 miles overnight. At around 2:00 am on 1 June 2009 he arrived at his sixth target, another home of a rabbi. At his sixth target’s home, he threw a Molotov cocktail but it bounced off the window and did not cause damage. Feeling discouraged by his failures, he drove back to Little Rock, AR in order to plan his next move (a six-hour journey) (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015).

Step 6: attack

On 1 June 2009, shortly after 10:00 am, while en route to his apartment from his three-day journey (detailed in step 5 above), AMM saw Private Long and Private Ezeagwula in U.S. Army fatigues who were standing outside the Army Navy Career Center in Little Rock, AR. At 10:19 am, he drove up to the Army Navy Center and pointed his rifle out of the car window firing 15 shots at the two soldiers (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015). Private Long collapsed immediately and when he arrived at the hospital less than an hour later (at 10:56 am) he was pronounced dead. Private Ezeagwula was seriously injured but survived the attack. When he was shot, he crawled back into the recruiting station while AMM continued to fire through the window until he had emptied his ten-round clip (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). AMM fled the scene. About 12 min later, he was pulled over and arrested. He was arrested wearing a green ammunition belt which had over 150 rounds of ammunition attached. In his pocket, there was also a loaded semiautomatic handgun and 24 rounds of ammunition. Officers found the rifle he had used in the attack in his truck in addition to a laser-sight equipped rifle, two silencers which were home-made, about 200 rounds of ammunition of various calibers, Molotov cocktails, binoculars, clothing, a white lab coat, medicine, and a plastic tub containing non-perishable food, water, and a butane lighter (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015).

When AMM was brought in for questioning after his arrest, waiving his Miranda rights, he told Detective Matt Nelson and Detective Tommy Hudson who were interviewing him that he was a practicing Muslim and that he had shot the two soldiers because of his anger at the U.S. military. He claimed that the previous night he had watched the video ‘Fitna Exposed’, which was a response to Dutch parliamentarian Geert Wilders’s anti-Islam movie ‘Fitna’. He proceeded to say that this video was the sole trigger which motivated his attack. He subsequently said that he had actually formulated the intention to carry out an attack when he was in Yemen and had explored other targets (in Nashville and Florence, Kentucky) before driving by the Little Rock recruiting station seeing the ‘easy targets’ (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014). He also made the claim that he was associated with al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), the jihadi organization’s Yemeni affiliate. It is considered unlikely that AMM had been a formal member (Gartenstein-Ross, Citation2014).

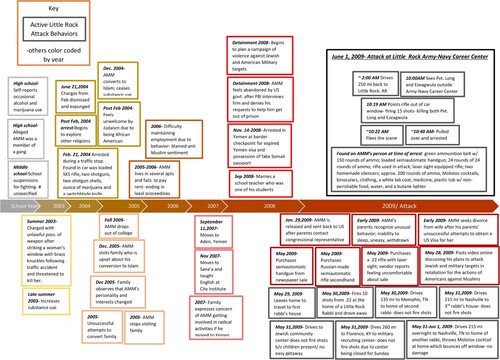

We have created a visual timeline of AMM’s warning behaviors (which were identified by applying the PTIV model to this case) from 2003 to the day of the attack on 1 June 2009 (see ).

Presence or absence of TRAP-18 indicators

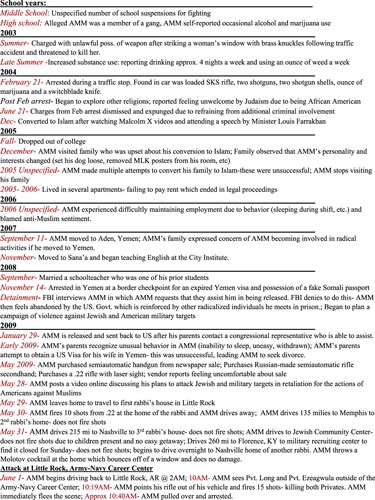

Each of the 18 indicators on the TRAP-18 is coded by the assessor as either present or absent. The assessor also has the option of selecting ‘Unknown’ if there is insufficient evidence to determine whether the indicator is present or absent. The presence of a cluster of TRAP-18 distal characteristics, coupled with the absence of all proximal warning behaviors means that the case should be monitored and reviewed on a regular basis (there is no need for more active management resources at this point). However, the presence of any one proximal warning behavior warrants active management of the case (e.g. face-to-face interview with the person of concern) (Corner et al., Citation2016; Corner & Gill, Citation2015; Goodwill & Meloy, Citation2019; Guldimann & Meloy, Citation2020; Meloy & Genzman, Citation2016). The TRAP-18 was retroactively applied to the case of AMM. The two authors carried out the TRAP-18 independently and then met to discuss their coding. There was agreement on all codes. Although this is not the proposed way to conduct a TRAP-18 in practice, in the research realm this was done in order to offer an additional layer of reliability rather than one author applying the TRAP-18 to this case without any type of verification. The findings from the retroactive application of the TRAP-18 in the case of AMM show that in the week before the attack, he exhibited five of the eight proximal warning behaviors (pathway, fixation, identification, energy burst, and leakage) and five of the 10 distal warning behaviors (personal grievance and moral outrage, framed by an ideology, thwarting of occupational goals, changes in thinking and emotion and criminal violence) ().

Table 1. Presence or absence of TRAP-18 Indicators in the case of AMM.

Discussion

In this case study of AMM and the attack on the Army-Navy Career Center in Little Rock, AR in June of 2009 both authors found that many of the proximal warning behaviors (5/8) and distal characteristics (5/10) were present leading up to the attack. These findings are consistent with the previously mentioned case studies where the TRAP-18 was administered retroactively. The proximal warning behaviors absent from this case study included novel aggression, last resort and directly communicated threat. These absent behaviors are also consistent with the prior studies looking at the attacks of the Frankfurt Airport, Berlin Christmas Market, the Kronan School, the perpetrators of the bombing in Osla, and shooting on the island of Utøya and Fort Hood Army Base (Böckler et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Erlandsson & Reid Meloy, Citation2018; Meloy & Genzman, Citation2016; Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015). In these case studies, there was zero evidence (0/5 cases) of a directly communicated threat, which is also absent from this case example. Additionally, this case example showed no evidence of novel aggression leading up to the attack, which is reflective of the previously mentioned studies where only one out of the five attackers was found to display novel aggression. The application of the PTIV model to this case also showed the temporal sequence of behaviors in the days, months, and even years leading up to the attack (see ).

The findings of this case example differ from previously conducted studies by having an absence of mental health disorder as well as the presence of criminal behavior. In the studies previously mentioned, three of the examples, Frankfurt Airport, the Kronan School, and Fort Hood (Böckler et al., Citation2015; Erlandsson & Reid Meloy, Citation2018; Meloy & Genzman, Citation2016), utilized the full TRAP-18. Within these findings, all but one of the subjects had a presence of mental health disorders and none of the subjects had a presence of criminal behavior. In regard to overall scores for TRAP-18 administration, the average number of TRAP-18 factors present, both proximal warning behaviors and distal characteristics, was 14.33, with a mode of 15. Within this case example, the subject, AMM, displayed only 10 factors of the TRAP-18. The retroactive use of these tools can assist in creating a detailed evidence-base of the temporal sequencing of warning behaviors displayed in the days, weeks, months, and even years leading up to the attack, further aiding to prevention efforts and early identification of individuals on the pathway to violence.

Potential limitations

There are potential limitations with the application of the PTIV model and the TRAP-18 to the case study presented in this article. First, the use of the PTIV and the TRAP-18 were carried out retroactively and not prospectively. The authors have not had any direct access to AMM or family members in order to carry out the application of the PTIV model and the TRAP-18.

Additionally, much of the information found and reported within this case example are items of self-report through evaluation, law enforcement and disciplinary records, and minimal reporting by family members. Within the literature, there was a limited number of sources that included direct interviews with family or friends, providing less insight into the day-to-day life of AMM. It should also be noted that around 2005, AMM discontinued contact with his family (National Threat Assessment Center, Citation2015) which may contribute to this lack of information source. This information would have been beneficial to determine AMM’s internet usage and presence, which could lend to the presence of the distal characteristic ‘dependence on virtual community’.

Clinical and legal implications

The findings of this retroactive application of the tools for the case of AMM support the theory that attackers who have perpetrated acts of targeted violence present with the proximal warning behaviors that are screened by the TRAP-18. Dr. Reid Meloy, the creator of the TRAP-18, states that a ‘warning’ needs to be initiated with the presence of one (1) proximal warning sign (Goodwill & Meloy, Citation2019). A warning is defined as a threat assessment with active management and involving any individuals in the subject’s life that may have the ability to serve in a role that enhances the management plan. The retroactive application of the TRAP-18 and PTIV to cases of targeted violence assists with identifying a timeline of behaviors, which in turn provides insight into pathway to violence and warning signs that someone may be a threat of violence. In this case, it is shown that AMM would have met the criteria to be administered a full threat assessment and active management plan far prior to the attack at Little Rock. Based on these findings, it is assumed that the TRAP-18 could be useful for clinicians to use as a screening tool to determine if a threat assessment or management plan is appropriate and can assist with early identification and intervention. The PTIV model was also used within this case example to analyze AMM’s trajectory toward the violent attack. The authors found that AMM displayed behavior progression consistent with the PTIV model and were able to identify examples of each step. These findings suggest that the PTIV model may be effective at identifying individuals of concern and assist in determining how imminent the threat posed by the individual may be. The use of the PTIV model may also assist clinicians or threat assessors in determining how quickly intervention may be needed as well as the most appropriate level of intervention. For example, an individual displaying probing and breaching behaviors may elicit more immediate and severe intervention in comparison to an individual who has not yet expressed violent ideation in addition to their identified grievance.

One finding from this case example that differed from other identified cases is the absence of a diagnosed mental health disorder within the subject. During AMM’s life, there is no documentation of a psychiatric evaluation outside of the forensic competency evaluation conducted after his arrest. During this evaluation, the court-ordered evaluator did not diagnose AMM with any mental health disorders recognized within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) (Gray, Citation2010). The nexus between mental health and lone-actor terrorism has been studied extensively and findings suggest the presence of mental health concerns is common amongst perpetrators. For instance, a study by Fein and Vossekuil (Citation1999) found that a majority (61%) of the lone-actor terrorists from their sample had contact with mental health services prior to attack, while a study by Gill, Horgan, and Deckert (Citation2014) found that only 31% of a sample of lone-actor terrorists had a documented history of mental illness (Corner & Gill, Citation2015). Taking into account the use of separate samples, these findings may suggest that while some individuals who later go on to perpetrate an act of targeted violence may seek or contact mental health services, fewer are receiving a formal diagnosis or treatment plan. While the presence of a mental health disorder is one of the ten distal characteristics within the TRAP-18, it is important to consider one’s ability to access mental health treatment, and facilitates a larger conversation regarding accessibility to behavioral health services and process of receiving a formal diagnosis. Universally, many factors serve as a barrier to receiving mental health treatment and subsequently a formal diagnosis, including but not limited to financial ability, lack of family support, cultural beliefs, and fear of stigmatization (Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., Citation2015). It is possible that individuals who engage in acts of targeted violence or lone-actor violent extremism may have experienced mental health concerns but were unable to access treatment, barring a formal diagnosis, therefore it is important to not rely solely on the presence of a mental health diagnosis to dictate an assessor’s final determination.

The role of mental health professionals in threat assessment extends greatly past diagnosis and clinical practice. Empirical evidence suggests that mental health professionals may also have a role in preventing lone-actor terrorist attacks (Corner & Gill, Citation2015) through proper and timely screening, information sharing, and participation in management plans. A common barrier of cross-system collaboration within threat assessment is the withholding of pertinent information, which has long impacted mental health professional’s willingness to share information regarding concerning behaviors. Across the world, mental health professionals are subject to information sharing statutes that inhibit the ability to share information except in certain circumstances where breaching confidentiality is appropriate, most commonly to prevent death of client or others. Research suggests that there may be ‘Protected Health Information paranoia’ where clinicians are reluctant, even fearful, of sharing any information due to the potential repercussions of improper information sharing even with the extensive research suggesting the benefits of ethical information sharing – such as enhanced care of patients (Wilkes, Citation2015). Information silos rob practitioners of the opportunity for early stage intervention by trained threat assessment and management professionals and the potential for prevention of violent acts. Instances of missed opportunity are documented in other cases of targeted violence such as the Aurora Theatre Shooter, James Holmes (herein referred to as JH) – who’s therapist was aware of his homicidal ideations but declined to report to law enforcement due to being unsure if information sharing criteria was met. While JH’s therapist was ultimately found not guilty of malpractice, it does not refute that prior knowledge of the violent ideations and warning behavior may have provided opportunity for intervention by law enforcement (see also Allely, Citation2020; Reid, Citation2018). To combat information sharing barriers, it is important to consider the use of agency Memorandums of Understanding or person-specific Releases of Information. Both information sharing release documents drastically impact both the ability and willingness of a professional to provide otherwise undisclosable information regarding their client, thus enhancing the assessor’s knowledge of the subject. These signed documents or agreements additionally suggest that a professional serving as an individual of concern’s therapist also can serve as an active member of a threat management plan, creating a more consistent and wholistic management plan. It is important to note that information sharing is identified to not only be a barrier across disciplines but also within different agencies of the same field, including law enforcement (Joyal, Citation2012). Efficient information sharing protocols and procedures for the providing and receiving of information may provide additional opportunities for intervention and the ability for cross-collaboration.

The importance of information sharing extends past mental health professionals and is often seen as a barrier across a variety of professions and agencies. A systematic review of the Arapahoe High School shooting in 2016 identified the lack of proper information sharing from school officials to law enforcement and other community agencies to be a large system error that led to failure to appropriately intervene (Goodrum & Woodward, Citation2016). It was determined that the failure to implement an interagency information sharing agreement and the lack of information sharing protocols directly contributed to the failure to provide intervention and potentially prevent an act of targeted violence. The value of information sharing within threat assessment can be found paralleled within ‘intelligence-led policing.’ Intelligence-led policing is the practice of utilizing crime analysis to identify patterns and appropriately deploy resources (Cope, Citation2004). The use of crime analysis is exemplified through information sharing across jurisdictional lines, both local and federal, and creates a more robust picture when determining key trends, allowing the opportunity to minimize risk through intervention and strategic deployment. An example of this is the use of Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTF). JTTFs are organized and managed by the FBI and comprised of officers from many jurisdictions including federal partners (Deflem, Citation2012). The JTTF is ultimately responsible for the investigation and prosecution of planned or carried out acts of terrorism and is involved in all aspects of a counterterrorism investigation. Each FBI field office houses a JTTF, with a collective contribution to the National Joint Terrorism Task Force in Washington D.C. and a common goal of terrorism prevention. This model is considered a ‘force multiplier’ and is a facilitator of information sharing across local and federal law enforcement partners (Deflem, Citation2012). This same consideration rings true for civilian-led threat assessment efforts and has the potential to reframe the mindset regarding information sharing. Without strong network of officers across jurisdictions and efficient information sharing protocols, JTTFs lose efficacy and crucial time when working to prevent acts of terrorism. The same rings true for generalized threat assessment, and especially affects the accuracy of structural judgement tools. Structural judgement tools such as the TRAP-18 are most effective when multiple data points of information are gathered across systems as it sheds light into the different areas of an individual’s life and their interactions with systems that they may operate within.

An individual’s determined level of risk may vary drastically based on the amount and severity of information gathered. Without proper information sharing, key indicators can be neglected, the cost being missed opportunity for early intervention, and the ability to prevent an act of violence. This is especially true for individuals that engage in what Clemmow, Bouhana, and Gill describe as low frequencies of leakage indicators and dynamic stressors (Citation2020). Individuals who are identified to have patterns of low frequency of leakage behavior may be more difficult to identify as a potential threat, especially if they are lacking past interactions of violence to demonstrate propensity (Clemmow et al., Citation2020). The need for information sharing across systems is imperative in cases such as this as even seemingly small data points may sway a determination. Interagency information sharing agreements are not only beneficial for the information gathering phase of threat mitigation, but also play a vital role in the development of a comprehensive threat management plan. A multidisciplinary team in which there are representatives from the various systems in which an individual of concern operates within allows for a consistent and comprehensive management plan, which may increase efficacy, so long as information sharing guidelines are clearly established and all parties are educated on the exemptions of information sharing guidelines. Another vital benefit of a cross-systems approach to threat management is the expanded capability to monitor and apply correction to an individual who may not adhere to countermeasures or other supportive management techniques (Ennis et al., Citation2015), which is paralleled within the JTTF model of counterterrorism with cross-jurisdictional representatives. AMM was not placed on any form of active threat management plan and it is difficult to say whether a comprehensive threat management plan may have been effective in preventing the tragedy in Little Rock. What can be said is that the use of a structural judgement tool such as the TRAP-18, with a culmination of information from the various sources regarding AMM’s mental state and propensity for violence may have initiated a proper threat assessment and allowed the opportunity for early intervention efforts such as punitive countermeasures, the addition of pro-social supports, and attempts to increase connection to society. It is important to remember that the use of threat assessment is not designed to predict whether an individual will conduct an attack, but to analyze observable behaviors and formulate a plan to counteract identified grievances through all means possible (Ennis et al., Citation2015). The ability to prevent begins with the willingness to share information and ends with the fear to collaborate.

On an individual level, it is important to be mindful of confirmation bias when using the TRAP-18 as Gill (Citation2015) highlighted. Another significant clinical implication of the utilization of the TRAP-18, especially with juveniles, is the impact of labeling on an individual’s quality of life and care. When looking at the diagnostic labeling of individuals, there is evidence that suggests that the presence of mental health diagnoses is stigmatizing and can serve as a barrier in a variety of instances ranging from job selection and hiring to access to quality healthcare. An example of this is the label of ‘psychopathic’, specifically in juveniles, and the moral and ethical concern that such a label may heavily influence and drive decision making in a legal setting toward punitive action rather than rehabilitative efforts (Petrila & Skeem, Citation2003, p. 691). Experimental studies have also produced results showing that individuals labeled as having a psychotic disorder or antisocial personality traits were more likely to be rated as having a higher potential for future violence (Edens et al., Citation2004). When administering the TRAP-18, where the presence of a mental health disorder is listed as one of the identified Distal Characteristics, it is important to acknowledge and control for pre-existing bias of those with mental health disorders in order to accurately assess an individual’s level of threat (Murrie et al., Citation2005). The retroactive use of the TRAP-18 on convicted perpetrators may have less clinical implications than in cases focused on individuals of concern with the purpose of early identification and prevention.

A potential legal implication of the application of the TRAP-18 for individuals presenting with concerning behavior is the possibility of being subject to a production of records request by law enforcement agencies regardless of organizational affiliation. Practitioners should also be mindful of the use of their TRAP-18 assessment results and the implications or potential influence on sentencing of future criminal proceedings.

This case highlights the importance of organizations such as Parents For Peace (P4P). P4P was co-founded by Melvin Bledsoe after his son (the case reported in this article) was radicalized and committed a deadly act of terrorism on US soil. His goal is that no other family should experience the trauma he continues to wrestle with. P4P is a non-governmental public health nonprofit organization empowering families, friends, and communities to prevent radicalization, violence, and extremism (https://www.parents4peace.org/about/). P4P offers a support helpline, community education through Serve2Unite, and rehabilitation with our Trauma and Recovery Program. In addition to prevention and recovery programs, P4P intervenes in the radicalization process through helpline interventions.

Future research directions

The absence of protective factors is a potential limitation of the TRAP-18 (Goodwill & Meloy, Citation2019). It would be beneficial to integrate the identification of key protective factors into the TRAP-18 assessment to assist in the creation of a robust threat management plan. Gill (Citation2015) mentioned the risk of confirmation bias when utilizing the TRAP-18 as it only focuses on identifying ‘risk factors’ and emphasized the lack of understanding around how protective factors can influence the accuracy of an individual’s determined level of threat (Gill, Citation2015). Further research is needed to determine relevant protective factors for evaluating the level of threat an individual may pose, and how those protective factors affect an individual’s determined level of threat.

It is also recommended that further research investigate the possibility of differences across ideological frameworks embraced by the subject within the TRAP-18 assessment, looking at a terrorist’s motivation and the belief system that influenced them to act, i.e. political, religious, single issue conflict, or an idiosyncrasy (García-Andrade et al., Citation2019). Further research on the concurrent use of the TRAP-18 and other validated actuarial health risk assessment measures such as the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), Historical Clinical Risk Management-20 (HCR-20), Columbia Suicide Screening, Beck Depression Inventory, etc. Understanding around the effects of combined use of tools may assist in identifying factors that may contribute to an individual’s grievance and vulnerability to coercion, which can be beneficial when determining and implementing countermeasures and threat management plans. Lastly, future research is needed in order to understand why some of the TRAP-18 indicators are not present in lone-actor terrorist cases.

Conclusion

The application of the TRAP-18 and the Path to Intended Violence for individuals of concern is recommended by the authors in addition to the retroactive use of both tools for accused perpetrators of extreme violence. The retroactive use of these tools can assist in creating a detailed evidence-base of the temporal sequencing of warning behaviors displayed in the days, weeks, months and even years leading up to the attack, further aiding to prevention efforts and early identification of individuals on the pathway to violence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

C. Tassin

Courtney Tassin, M.A., is an instructor and subject matter expert at the Louisiana State University’s National Center of Biomedical Research and Training and a Master Trainer for the US Department of Homeland Security’s Threat Evaluation and Reporting Courses. City Government of Aurora, Colorado, Louisiana State University’s National Center of Biomedical Research and Training, University of Denver’s Graduate School of Professional Psychology.

C. S. Allely

Clare S. Allely, Professor of Forensic Psychology, School of Health Sciences, University of Salford, Manchester, England and affiliate member of the Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. She is also an Associate of The Children's and Young People's Centre for Justice (CYCJ) at the University of Strathclyde. Her research specializes in how certain features of autism spectrum disorder may provide the context of vulnerability to engaging in a wide range of offending behaviors including lone-actor terrorism, terroristic behaviors, extremism, the viewing of indecent child imagery, mass shootings, school shootings, hands-on sexual offending, cybercrime, stalking, violence, zoophilia, and arson. She also has a research interest in the pathway to intended violence in extreme violent offenders (e.g. lone-actor terrorists, school shooters, mass shooters, and serial homicide offenders). She acts as an expert witness in criminal cases and HCPC fitness to practice cases and also contributes to the evidence-base used in the courts on psychology and legal issues through her published work. She is author of the book ‘The Psychology of Extreme Violence: A Case Study Approach to Serial Homicide, Mass Shooting, School Shooting and Lone-actor Terrorism’ published by Routledge in 2020 and author of the book ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder in the Criminal Justice System: A Guide to Understanding Suspects, Defendants and Offenders with Autism’ published by Routledge in 2022.

References

- Allely, C., & Faccini, L. (2019). Clinical profile, risk, and critical factors and the application of the “path toward intended violence” model in the case of mass shooter Dylann Roof. Deviant Behavior, 40(6), 672–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2018.1437653

- Allely, C. S. (2020). The contributory role of psychopathology and inhibitory control in the case of mass shooter James Holmes. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 51, Article 101382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101382

- Allely, C. S., & Faccini, L. (2017). “Path to intended violence” model to understand mass violence in the case of Elliot Rodger. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.09.005

- Allely, C. S., & Wicks, S. J. (2022). The feasibility and utility of the terrorist radicalization assessment protocol (TRAP-18): A review and recommendations. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2022-51960-001

- Basra, R., & Newmann, P. R. (2017). Crime as jihad: Developments in the crime-terror nexus in Europe. Combating Terrorism Center, 10, 9.

- Bergen, P. (2011). Assessing the terrorist threat. DIANE Publishing.

- Bergen, P., & Hoffman, B. (2010). Assessing the terrorist threat. A report of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s National Security Preparedness Group, 6. http://ctcitraining.org/docs/BPC_AssessTerroristThreat.pdf

- Bergen, P., Hoffman, B., & Tiedemann, K. (2011). Assessing the jihadist terrorist threat to America and American interests. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 34(2), 65–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2011.538830

- Böckler, N., Allwinn, M., Metwaly, C., Wypych, B., Hoffmann, J., & Zick, A. (2021). Islamist terrorists in Germany and their warning behaviors: A comparative assessment of attackers and other convicts using the TRAP-18. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 7(3-4), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000150

- Böckler, N., Hoffmann, J., & Meloy, J. R. (2017). “Jihad against the enemies of Allah”: The Berlin Christmas market attack from a threat assessment perspective. Violence and Gender, 4(3), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2017.0040

- Böckler, N., Hoffmann, J., & Zick, A. (2015). The Frankfurt airport attack: A case study on the radicalization of a lone-actor terrorist. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 2(3-4), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000045

- Brugh, C. S., Desmarais, S. L., & Simons-Rudolph, J. (2020). Application of the TRAP-18 framework to US and Western European lone actor terrorists. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1758372

- Calhoun, F. S., & Weston, S. W. (2003). Contemporary threat management: A practical guide for identifying, assessing, and managing individuals of violent intent. Specialized Training Services.

- Challacombe, D. J., & Lucas, P. A. (2019). Postdicting violence with sovereign citizen actors: An exploratory test of the TRAP-18. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 6(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000105

- Clemmow, C., Bouhana, N., & Gill, P. (2020). Analysing person-exposure patterns in lone-actor terrorism: Implications for threat assessment and intelligence gathering. Criminology and Public Policy, 19(2), 451–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12466

- Cope, N. (2004). ‘Intelligence led policing or policing led intelligence?’ Integrating volume crime analysis into policing. British Journal of Criminology, 44(2), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/44.2.188

- Corner, E., & Gill, P. (2015). A false dichotomy? Mental illness and lone-actor terrorism. Law and Human Behavior, 39(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000102

- Corner, E., Gill, P., & Mason, O. (2016). Mental health disorders and the terrorist: A research note probing selection effects and disorder prevalence. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 39(6), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2015.1120099

- Deflem, M. (2012). Joint terrorism task forces. In Frank Shanty (Ed.), Counterterrorism: From the cold war to the war on terror, vol. 1 (pp. 423–426). Praeger Security International.

- Douglas, K. S., Guy, L. S., & Hart, S. D. (2009). Psychosis as a risk factor for violence to others: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 135(5), 679–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016311

- Edens, J. F., Desforges, D. M., Fernandez, K., & Palac, C. A. (2004). Effects of psychopathy and violence risk testimony on mock juror perceptions of dangerousness in a capital murder trial. Psychology, Crime, and Law, 10(4), 393–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160310001629274

- Ennis, L., Hargreaves, T., & Gulayets, M. (2015). The integrated threat and risk assessment centre: A program evaluation investigating the implementation of threat management recommendations. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 2(2), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000040

- Erlandsson, Å, & Reid Meloy, J. (2018). The Swedish school attack in Trollhättan. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 63(6), 1917–1927. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13800

- Etter, G. W. (2015). Changes in local law enforcement brought about by 9/11. In Terrorism and counterterrorism today (Vol. 20, pp. 219–240). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Faccini, L. (2016). The application of the models of autism, psychopathology and deficient Eriksonian development and the path of intended violence to understand the Newtown shooting. Archives of Forensic Psychology, 1(3), 1–13.

- Faccini, L., & Allely, C. (2016a). Mass violence in individuals with autism spectrum disorder and narcissistic personality disorder: A case analysis of Anders Breivik using the “path to intended and terroristic violence” model. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.10.002

- Faccini, L., & Allely, C. S. (2016b). Mass violence in an individual with an autism spectrum disorder: A case analysis of Dean Allen Mellberg using the” path to intended violence” model. International Journal of Psychology Research, 11(1), 1–18.

- Fein, R. A., & Vossekuil, B. (1999). Assassination in the United States: An operational study of recent assassins, attackers, and near-lethal approachers. Journal of Forensic Science, 44(2), 321–333.