?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Social media platforms have become a prominent feature in modern-day communication, allowing users to express opinion and communicate with friends and likeminded individuals. However, with this revolutionary form of communication comes risks of exploitation and utilisation of these platforms for potentially illegal and harmful means. This article aims to explore the community guidelines and policies of prominent social media sites regarding extremist material, comparing the platform’s policies with the user experiences. To measure social media user experience and user exposure to extremist material, this article pilots the use of a new scale: The Online Extremism Exposure Scale (OECE), which measures both the user’s exposure to extremist communication and hate speech online. Users reported varied levels of exposure to both hate speech and extremist communication, with. the results indicating that users in the sample are being exposed to extremist material approximately 48.44% of the time they spend on social media daily. The results of this pilot study highlight potential failings by prominent social media platforms in their efforts to reduce users being exposed to extremist material. Limitations, future research, and implications are discussed in detail.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The rise in popularity of social media platforms over the last few years can be attributed to numerous factors, such as the ever-increasing dependence on the internet in our everyday lives and the Covid-19 pandemic that forced people to stay indoors, where social media was often the only form of communication with friend and family outside of their residence (Molla, Citation2021). It has been estimated that 58.4% of the world’s population use social media, with users having an average screen time of almost two and half hours every day (Global WebIndex, Citation2022). As social media provides users with the means to instantly communicate with other users around the world and spread information to large audiences from varying backgrounds and locations with very little effort, it has been argued that social media has potentially become a fundamental element of all aspects of modern life, from corporate business using it to market new products, to intelligence agencies using it gather intel on a potential suspect (Fortin et al., Citation2021). With these new innovative forms of communication and tool for promoting one’s own brand and ideas, it was natural that these cyberspaces would eventually be taken advantage of by individuals and groups with negative and potentially criminal intent, such as fraudsters who could take advantage of the anonymity that comes with an online presence and extremist groups who could utilise the vast audiences, they can reach through social media platforms (Thukral & Kainga, Citation2022).

Focusing on extremist groups, research exploring the evolution of extremist groups to incorporate the internet and social media into their work has found that social media has now become a fundamental tool in extremist groups (organisations that actively or vocally oppose mainstream and fundamental societal values: HM Government, Citation2015) recruitment strategy, as it allows them to spread their propagandas and messages to large audiences when trying to recruit more members for their cause (Tsesis, Citation2017). It has been argued that social media has become a prominent instigator for the radicalisation process (a changing in beliefs and behaviours that justify violence to promote a particular ideology: Doosje et al., Citation2016) in individuals, with social media platforms also providing these individuals with the knowledge and information about not only how to join an extremist organisation but the technical and material knowledge about how to commit a terrorist attack (Bastug et al., Citation2020). This potentially indicates that social media and online networking might have direct influence on the preparation and activity of terrorist groups (Organisations that use or threaten action to promote a particular ideology: Terrorism Act 2000), with research even suggesting that the ease of communication social media platforms provides these extremist and terrorist organisations, allows them to advance both the quality and quantity of their efforts to further the cause they promote (Chetty & Alathur, Citation2018).

Looking directly at the extremist content that is on social media and how it may be encouraging the radicalisation process in individuals, it appears that extremism online takes the form of numerous linguistical archetypes, all having unique purposes and desired responses from the users who are exposed to this content (Williams & Tzani, Citation2022). One of the most prominent extremist groups using social media as a tool of recruitment is the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which use social media to promote a positive perception of the group while also striving to encourage a negative perception of the world outside the group and foster damaging and hateful perceptions of their enemies and opposition (Khawaja & Khan, Citation2016). However, it is not just ISIS that use social media to promote their own brand, with Williams and Tzani (Citation2022) finding that positive framing of one’s own group while simultaneously negatively framing outside groups and perceived opposition is one of the most prominent strategies of most extremist groups in social media cyberspaces, using this framing combination as not only a recruitment technique but to also promote radicalisation. This utilisation of language (labelled ‘hate language’ by Williams & Tzani, Citation2022) of an extremist group negatively framing outgroup members appears prominently in research exploring the extremist discourse on social media (Agarwal & Sureka, Citation2015; Grover & Mark, Citation2019). It is this running narrative of the group being a vehicle for social justice, compared to their opposition who are focused on oppressing them, that promote a sympathetic and gradual shift in perspective for individuals exposed to this content, especially when it is accompanied by intense images and videos to enhance their argument further (Bouko et al., Citation2022).

This exposure is then enhanced further if the user interacts with the extremist content and engages in communication with the users posting this content, increasing their interest and curiosity about this newfound ideology, potentially furthering the advancement of the radicalisation process. With social media potentially acting as a facilitator for individuals to become radicalised while also being utilised as a convenient hub for the planning and communication of extremist and terrorist activity, effective safeguarding strategies for both counter terrorism agencies and the social media platforms themselves are more imperative than ever (Osaherumwen, Citation2017).

Looking at efforts to challenge online extremism and terrorist-related content in social media cyberspaces, research has suggested that the current strategies being implemented by counter terrorism bodies, although varied widely in their strategy and utilisation of resources, have fallen short of what is effectively needed to police social media appropriately, (Elgot & Dodd, Citation2022; Lyons et al., Citation2022). As noted above, one of the main strategies applied by extremist groups when operating online is the promotion of both a positive framing narrative of the group and a negative framing narrative of the group’s opposition, to gain both support for their own group while simultaneously discrediting other groups who oppose the groups positive narrative (Williams & Tzani, Citation2022). To counter this, counter terrorism bodies have produced units to counteract the content the extremist group promote and provide an alternative narrative to the positive and negative framing the group is advocating (Aistrope, Citation2016). However, despite the widespread consensus that this is one of the most effective counter measures to combat the extremist narrative, there is evidence to suggest that they are not only limited in their efficiency but also advancing the extremist narrative further (Belanger et al., Citation2020). One of the potential reasons for this strategy's failures, is that these government controlled counter terrorism efforts fail to effectively counteract the narratives and misinformation that is flooded onto these social media platforms by extremist groups with the counter-misinformation teams assigned to this role often being noticeably disingenuous, often producing the opposite effect of what they were hoping to achieve and actually unintentionally supporting the extremist groups narrative that their opposition are trying to oppress and silence them (Aistrope, Citation2016).

With outside efforts to police social media by counter terrorism agencies being limited in efficiency, the line of defence against extremist content in public social cyberspaces is the social media sites themselves. Social media platforms have been publicly adamant in their efforts to reduce and moderate any material on their sites that breaches their outlined content policies regarding extremism and terrorism (Grygiel & Brown, Citation2019). This is usually achieved through a mixture of both content moderation and private multilateralism, in a continually advancing effort to become proactive on an effective safeguarding and counter terrorism scale (Borelli, Citation2021). However, there are numerous instances where these social media sites have failed to act on an issue of extremism on their site, such as falsely claiming to have removed harmful accounts without evidence and even presenting advertisements alongside harmful extremist content (Grygiel & Brown, Citation2019). It could be argued that these issues arise from the perpetual juggling of both the combination of allowing their users to engage in free speech and the constant demand for moderation of extremist content (Grygiel & Brown, Citation2019). This issue could also be influenced through the choice of definition that these sites choose to implement, such as the contrasting stances adopted by YouTube and Facebook, with the former providing a vague and unclear statement, claiming that the site ‘strictly prohibits content related to terrorism’, whereas Facebook attaches a detailed lengthy classification of what they define as terrorist content, focusing on it having to contain a threat of violence (MacDonald et al., Citation2019).

Another potential influence on why there are shortcomings in the extremist moderation efforts of social media sites, is their criteria for a breach of policy, with Facebook stating that they may remove content that breaches their policies on extremism but only if the intention of the content was harmful, with posts being created to raise awareness of extremist content not being classified as a breach (Meta, Citationn.d.). Twitter has also made this claim, stating that content will be moderated based on intent of the post, as opposed to the content of the post (Twitter, Citationn.d.), potentially showcasing this balancing act and dichotomy of maintaining the platform as a space for free speech while also trying to screen for extremist content.

Despite these highlighted limitations and potential issues in their practiced policies, popular social media sites still maintain the stance that despite a few case examples they are still operating and expanding their safeguarding strategies to prevent extremism on their networks at an acceptable and expected standard (Squire, Citation2019). Yet, research has highlighted that there are numerous issues and failings in not only their ability to moderate and prevent extremism from appearing on their sites but also in their own implementation of their own policies regarding extremism and their aim of making their platforms a non-harmful source of content for all their users. Focusing on the users’ experience of these sites, there is little research exploring the exposure rate to which a social media user experiences harmful extremist content while they are using these sites.

It could be argued that this is because the social media sites are successfully implementing their anti-extremist policies, yet we know that there are numerous instances of individuals not only being exposed to extremist material on social media but also being exposed at a degree of severity that it potentially begins and encourages the process of radicalisation (Baugut & Neumann, Citation2020). Therefore, if there are policies in place to facilitate the user experience and safeguard users from extremist content, yet there are still reported breaches of these policies escaping the moderation strategies of the sites, then maybe the most appropriate area to investigate in regard to this issue is the user experience itself and explore not only if users of social media are experiencing content that the site claims is moderated for but what, if any, extremist content they are being most exposed to. This will allow both an indication and measurement of how much extremist content individuals on social media are being exposed to, as well as any discrepancies between the rules and safety regulations of social media platforms and the users’ experiences on these sites, in the context of extremist content. The present study aims to do that by:

Methodology

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Huddersfield.

Participants

The sample utilised for the questionnaire analysis consisted of 106 participants, with an age range of 18–77 (M = 35.58, SD = 14.89). As the target population for this research were individuals who use social media sites (as this research is measuring their experience and perspective of extremist content online), the most appropriate place to disseminate this survey was on mainstream social media sites (e.g. Facebook, Twitter), as this was a supplementary method of assuring that the participants did indeed use social media sites. The questionnaire was available to participate in for 3 months, ending in October 2022. 58.5% of the sample consisted of self-identified female participants (N = 62), with self-identified male participants being the second largest gender categorisation (N = 26). One participant identified as transgender and another participant identified as non-binary, with 16 of the participants opting for the option to not state their gender. Regarding the countries in which these participants were based, 72.6% of the sample claimed to be based in the United Kingdom (N = 77), with the next most popular domain being the United States with 4.7% of the sample (N = 5). 15.1% of participants did not state their domain country (N = 16).

Questionnaire

Demographics and online usage

The questionnaire asked participants to state their demographical information (e.g. age, gender) and asked them to state what social media sites they currently use from a list of popular platforms (e.g. Twitter, Facebook, Instagram), as well as state the average amount of time they spend on these sites. The questionnaire consisted of the Online Extreme Content Exposure Scale.

Online Extreme Content Exposure Scale (OECE)

The scale that was utilised for this research was created through a combination of both the findings produced from a systematic review by Williams and Tzani (Citation2022), where they explored the radicalisation language found on social media, and the policies and promises social media sites state they are upholding in their efforts to prevent radicalisation. This then resulted in a scale being created, which comprised of 20 questions measured on a 6-point Likert scale (Anchor range: 1 = Never, 6 = Always) asking participants about the frequency of exposure to extremist content they experience on social media e.g. ‘I see hateful comments online that are directed to a particular group/persons’. To ensure that all participants were familiar with the terms included in some of the questions, before the questions were presented, a screen containing the UK government’s definition of Extremism (HM Government, Citation2021) was shown to participants as well as the definition of ‘Ideology’ (Vocabulary.com, Citationn.d.). The window of the questionnaire that contained the definitions utilised and presented to participants stated:

Here are some definitions of the terms Extremism and Ideology to consider when answering the next set of questions. Please only click ‘Next’ once you have read both definitions

Definition of Extremism:

The UK Government defines extremism as vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. Extremism also includes calls for death of members of the armed forces.

Definition of Ideology:

An ideology is a set of opinions or beliefs of a group or an individual.

The justification for including and exploring hate speech alongside extremist communication in the OECE’s exploration of exposure to extremist content, is the evidence in previous literature that has explored extremist content online and highlighted that hate speech is potentially a common precursor to an individual’s involvement with extremist and terrorist organisations (Grover & Mark, Citation2019; Parker & Sitter, Citation2016; Scrivens, Citation2021; Williams & Tzani, Citation2022). There is also evidence from previous research to suggest that individuals who become involved with extremist and terrorist groups started their radicalisation process through interaction and engagement with other likeminded individuals and groups on social media through the mutual opinions and shared support of using hate speech towards a targeted population, often the outgroup of their similar and mutual ideological beliefs (Gerstendfeld et al., Citation2003; Phadke & Mitra, Citation2020; Weimann & Masri, Citation2020). This prevalence and potential importance of hate speech in previous literature exploring the same phenomena (online exposure to extremist content) as the present study, warranted the inclusion of hate speech in the OECE as a separate measure to extremist communication. As the two phenomena can sometimes occur simultaneously or be the product of the other (such as the exposure with hate speech online encouraging extremist communication with other likeminded individuals: Williams & Tzani, Citation2022), the OECE also provides an overall score of extremist exposure, which consists of a combination of both the exposure scores of hate speech and extremist communication reported by the participants.

Social media sites policy

The comparative information for the questionnaire, the social media sites’ extremism safeguarding policies, were all sourced from the official sites of each site. The information sourced from these sites was in relation to the extremist topics explored in the questionnaire: Hate Speech and Extremist content, which the sites all discuss in their individual community standards sections of their rules and policies. All information sourced was in accordance with the policy regulations that were active in November 2022, with all the sites included in Appendix.

Scoring of the scales

For the scoring of the OECE components, each corresponding answer to the questions applied the traditional 6-point Likert scale values (1 = Nothing, 6 = Always), with the Hate Speech component of the OECE having a possible score range of 12–72 and extremist exposure having a possible range of between 8 and 48. The overall scale has an extremist exposure score range of 20–120.

Regarding the interpretation of the scores, this study views that anything above the lowest possible score is a concern and an indication that these sites contain extremist/terrorist material, as the absolute goal and aim for all the included social media sites is no extremist content on their sites whatsoever. Any score above the lowest possible score indicates that these sites do contain some extremist material, with the higher the score the more extremist material being exposed to individuals. If the highest score on each item is classified as ‘Always’, then a maximum overall score would indicate that the participant is always exposed to extremist content/hate speech when using social media sites. With this logic implemented, a potential percentage of exposure could be created: e.g. Mean score for Hate Speech Exposure of 50, minus the value between zero and the minimum score (50–12 = 38) multiplied by 1.38 (100/72). Then the following equation can be completed, and a percentage of exposure produced:

In this example, the percentage could potentially provide the inference that this individual is exposed to extremist content 52.77% of the time they are using social media sites.

Reliability

As this is a new scale, the reliability of the measures is relevantly unknown. However, in the context of the present study and sample, the Cronbach Alpha for the OECE overall was α = .936, with the Hate Speech segment individually recording a Cronbach Alpha of α = .921 for the 12 items, with the 8 items of the Extremist Communication segment of the OECE recording a α = .909.

Results

Social media site policies

Each social media site’s community guidelines were reviewed and cross referenced with the topics explored within the OECE scale, with each topic openly stated in the community guidelines of the social media site being marked in .

Table 1. A table to show the topics each social media site openly states they do not support.

As highlighted in the table above, all the selected social media sites have open statements in their community guidelines that overtly state their intolerance of any of the Hate Speech components included in the OECE Hate Speech scale. However, the results also indicate that some of the selected sites do not openly state their intolerance to certain aspects of the Extremist Communication items of the OECE, with four sites excluding an open declaration against the use of Extremist symbols on their site.

Site popularity and average time of use

When reviewing the participant’s response to the question ‘Which of the following online sites do you use? [Tick all that are relevant]’, followed by the selected sites, the results showcase how Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram are the four most prominently used social media sites by the participant, as over half the sample stated they use these sites (). The questionnaire also asked participants the average time they spent on these social media sites a day, with the average time being just over two and half hours a day (M = 2.39, SD = .89). This corresponds with literature exploring the same variable (Global WebIndex, Citation2022).

Table 2. Table to show the frequency of participants that used the selected sites.

OECE

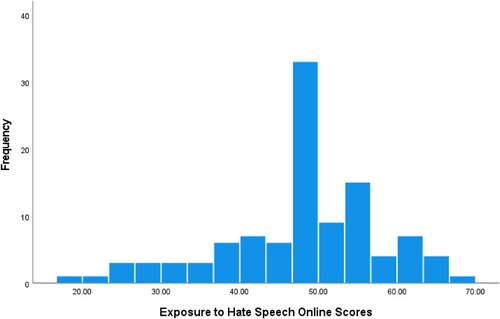

Hate speech

The responses to the Hate Speech component of the OECE scale revealed that the mean average score of the participants in regard to their exposure to hate speech when using social media was 47.73 out of a maximum 72 (SD = 9.93: ). As a percentage of 72, this indicates that on average, the participants in the sample were exposed to hate speech when using social media 49.63% of the time.

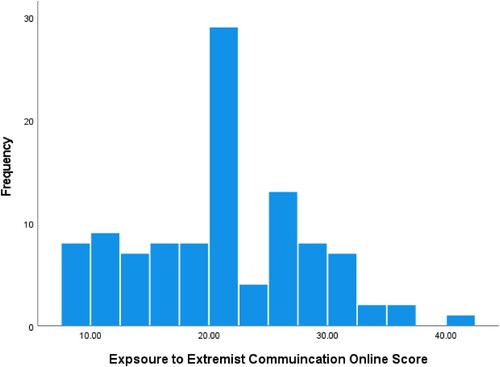

Extremist communication

The results of the Extremist Communication item scale of the OECE revealed that the mean average score was 20.71 out of 48 (SD = 8.21), with this indicating that the sample was exposed to extremist communication 26.48% of the time they were using social media sites ().

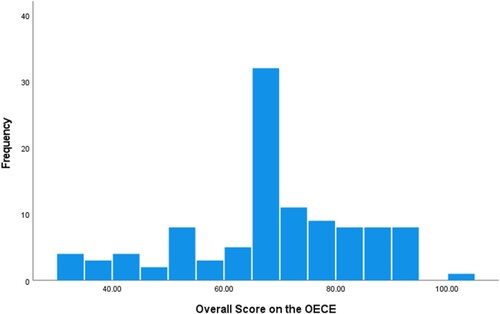

When reviewing the results of the OECE overall, the results revealed a mean average of 68.44 (SD = 15.34). When transformed into a percentage, the results potentially indicate that the participants are exposed to extremist content on social media 48.44% of the time ().

If users on average spend just over two and half hours a day on social media (M = 2.39) and are exposed to extremist material 48.44% of the time, this could potentially suggest users are being exposed to extremist material for 77 min a day via social media (48.44% of 159 min).

Discussion

The results highlighted that despite the overwhelming statements by these prominent social media sites that they have no tolerance for extremist material and content on their sites, the results from the questionnaire exploring user experience showcased that this harmful material still exists on these sites. Inspecting the results further, each site stated openly that they do tolerate any of the hate speech elements explored by the OECE, all stating in their community guidelines these topics will be removed, yet the user experience questionnaire revealed that participants are exposed to hate speech on social media regularly. Furthermore, regarding the extremist communication scale of the OECE, despite all the sites included stating some level of intolerance to extremist communication, participants reported that they were exposed to extremist content consistently when using the social media platforms. Overall, this potentially showcases the failings of these social media sites to police their networks for extremist content.

When inspecting the discrepancy between sites on their statements, Twitter did not explicitly claim that support of extremism was against policy, unlike the other sites included, but stated that glorification of violence or hate was. This coincides with contemporary reports that have showcased how Twitter is a valid amplifier of extremist narratives, with posts on that site being held responsible for instigating and fuelling far-right extremist attacks while remaining in the community guidelines (Hayden, Citation2021). Reddit and Quora were also highlighted in the policy table for not explicitly stating their intolerance of extremist discussion, with this also coinciding with reports of these online sites containing posts that have influenced extremist attacks, with Reddit specifically accused of playing a significant role in the far-right Charlottesville riots (Mulcair, Citation2022). A potential explanation as to why these sites have deviated from the community guidelines that were intolerant of these extremist discussions and supports, that the other sites all outrightly stated, could be fuelled by how the sites are constructed. These three sites are structured to provide users with a platform that provides users with the ability to express their opinion and individual beliefs, with the justification of expressing free speech as their defence against potentially causing offence or harm (Mulcair, Citation2022). In addition, these three sites operate within the legislative framework of the country their main offices are based (US), where free speech is written into the first amendment of the country's constitutional legislative practice (The White House, Citationn.d.), making free speech a more predominant focus for the company’s direction and actions. These US-based companies are also protected by the Communications Decency Act (1996) which provides a broad immunity for these social media sites in regard to the content that is shared on their sites, placing responsibility for content on the users as opposed to the sites themselves. Issuing change to their community guidelines and removing content that contains extremist material would impede their ability to provide this free speech element, and a fundamental legislative right, to their users (Yar, Citation2018).

However, this research suggests that the issues of extremist material being exposed to users is not monogamous to social media sites that do not explicitly state their intolerance of extremist narratives. Facebook, a site that has openly declared intolerance towards all the components included in the OECE, have been constantly criticised for their platform containing large volumes of extremist material and discussion, especially regarding the discussions promoting and supporting far-right and ISIS ideologies. The social media platform Tik Tok also openly states their intolerance to hate speech or extremist communication in their community guidelines, yet it has been well documented beyond the results of this research that users are being consistently exposed to extremist ideological material (Weimann & Masri, Citation2020). This potentially indicates that the issue of extremist content thriving on social media sites goes beyond the policies and statements made by individual companies.

The results also provided potential inferences on the volume of the extremist material users experience, such as the potential inference produced from the Hate Speech scale of the OECE, suggesting that the users in this research sample were, on average, being exposed to hate speech 49.63% of the time they were on social media. This is a potentially alarming statistic to reveal, especially considering the overall OECE results revealed the participants were potentially exposed to both hate speech and extremist communication 48.44% of the time they spent on social media. This potentially contradicts the transparency reports that these social media sites provide the public, which outline the behind-the-scenes tackling of the content the OECE measured in the context of user perception (Hate speech and Extremist communication). Facebooks July to September 2022 report highlighted that they claim to have found and flagged 99.1% of extremist-related content and 90.2% of hate speech content on their site before users had chance to be exposed to it and report it to the site admin (Meta, Citation2022). The same report highlighted similar reporting’s for Instagram, reporting 96.7% of extremist-related content and 93.7% of hate speech content was removed before users had a chance to report it. YouTubes transparency report showed that 94.5% of the total removed videos in the report period of July–September 2022 were removed on automatic detection via automated flagging or member of YouTube’s Trusted flagging programme, with the aim to remove the video before users are exposed to its content (Google, Citationn.d.). Yet, although we are unable to determine how much of the extremist content the users claim they were exposed to was on these two sites, these claims combined with the findings of this research could indicate that; even after removing more than 90% of the content screened in the OECE, users were still exposed to this content for nearly half of their time on the site, potentially indicating that the approximately 10% of content that was exposed to users before being reported constituted almost half of their time on the site. If almost half the content users are exposed to its potential extremist nature, then this highlights not only a potential explanation to the rising numbers of individuals being radicalised (Bates, Citation2012) but also the potentially large failings of the social media companies at policing the extremist content on their sites. Further research into the failings of the social media sites individually could provide a deeper exploration of what extremist content is most prevalent on which site, potentially identifying commonalities and differing tactics by extremist promoters when they utilise social media sites for ideological promotion.

Limitations

As this was a pilot study, exploring this area with the utilisation of a new scale (OECE), there were some limitations. The sample size utilised for this pilot study was limited to only 106 participants potentially effecting the validity of the findings. However, it was discussed by Johanson and Brooks (Citation2010) that the minimum representative sample size for a pilot study that is purposed for scale development is 30 participants. In reflection of this, the present study utilised a much larger sample, potentially increasing the validity of the scale’s reliability scores and validity of the measurements. Another limitation was the operationalisation of the abstract terms utilised in the study, such as ideology and extremism, as the literature showcases the lack of cohesion regarding a generalised understanding of these concepts. Although the present study provided definitions of these two terms to aid in the participant’s understanding of the terms utilised in the survey, the participant’s level of understanding surrounding these speculative terms is unknown as it was not measured for in this pilot study. Future expansions on the OECE scale should implement a possible measurement of understanding for these terms, to ensure the participants are utilising a similar understanding of the measured phenomena, which would enhance the validity and reliability of the results.

Implications

The main implication of this study is that it pilots and utilises a potentially valuable measure of online exposure to extremist material. The scale was not only reliable when assessed through Cronbach Alpha analysis, which highlighted a strong internal reliability for both individual sub scales and the scale as a whole, but also produced results that can provide a potential inference on the volume of extremist material an individual is exposed to on a daily basis while using social media, using the suggested formulaic equation. The utility of the OECE provides a valuable tool and assessment into the volume of extremist content online and even potentially the phenomena of individuals becoming radicalised through social media interactions. The utilisation of the subscales of the OECE also provides a potential avenue for exploration regarding the specific typology of the extremist content an individual is being exposed to, such as hate speech, which has been highlighted as a key instigator of an individual becoming interested in extreme ideologies and a common linguistic device of extremist discourse (Williams & Tzani, Citation2022). As found in the present study, participants experience more exposure to hate speech than outright discussion of extremist ideology, potentially highlighting a preferred tactic of extremist online promotion and potentially showcasing how content moderation is more effective for extremist communication as opposed to hate speech. The OECE could be utilised to explore social media sites individually, to discover potential commonalities and differences in the volumes and typologies of exposure users experience on those sites. This could then enhance the findings of the present study, by highlighting the social media sites that expose their users to the highest volumes of extremist content, potentially calling attention to the gaps in their content moderation and contrast in their public community guidelines and policies.

Conclusion

The results of this research showcase the potential failings of social media companies regarding their safeguarding of extremist material and upholding their community guidelines. The results also indicated that users of prominent social media sites may be exposed to extremist material daily, showcasing not only the volume of extremist material online but the prevalence of exposure of this material to users. Although this paper was only a pilot study, the OECE demonstrated its potential as not only a measure of extremist exposure online, but the type of extremism users is exposed to (i.e. Hate speech).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas James Vaughan Williams

Thomas James Vaughan Williams: At the time of article submission, Thomas was a part time lecturer for the MSc Investigative Psychology at the University of Huddersfield and was working towards gaining his Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology with a focus on the language used online by terrorists to radicalise and recruit followers and supporters.

Calli Tzani

Calli Tzani: At the time of article submission, Dr Calli Tzani was a senior lecturer for the MSc Investigative Psychology and MSc Investigative Psychology at the University of Huddersfield. Dr Tzani has been conducting research on online fraud, harassment, terrorism prevention, bullying, sextortion, and other prevalent areas. See profile at https://research.hud.ac.uk.

Helen Gavin

Helen Gavin, PhD, joined the University of Huddersfield as Divisional Head of Psychology and Counseling in 2005, having previously been Head of the School of Psychology at the University of the West of England, and Senior Lecturer in Psychology at Teesside University. Since 2018, she has been Subject Lead in Psychology with responsibility for postgraduate developments, management, and leadership.

Maria Ioannou

Prof Dr Maria Ioannou is a Chartered Forensic Psychologist (British Psychological Society), HCPC Registered Practitioner Psychologist (Forensic), Chartered Scientist (BPS), European Registered Psychologist (Europsy), Associate Fellow of the British Psychological Society, Chartered Manager (Chartered Management Institute) and a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. She is the Course Director of the MSc Investigative Psychology and Course Director of the MSc Security Science.

References

- Agarwal, S., & Sureka, A. (2015). Lecture notes in computer science. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Distributed Computing and Internet Technology, 8956(1), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14977-6_47

- Aistrope, T. (2016). Social media and counterterrorism strategy. Australian Journal of International Affairs, 70(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2015.1113230

- Bastug, M. F., Douai, A., & Akca, D. (2020). Exploring the ‘demand side’ of online radicalization: Evidence from the Canadian context. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 43(7), 616–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1494409

- Bates, R. A. (2012). Dancing with wolves: Today’s lone W s lone wolf terrorists. The Journal of Public and Professional Sociology, 4(1), 1–14. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1023&context=jpps

- Baugut, P., & Neumann, K. (2020). Online propaganda use during Islamist radicalization. Information. Communication & Society, 23(11), 1570–1592. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1594333

- Belanger, J. J., Nisa, C. F., Schumpe, B. M., Gurmu, T., Williams, M. J., & Putra, I. E. (2020). Do counter-narratives reduce support for ISIS? Yes, but not for their target audience. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(1059), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01059

- Borelli, M. (2021). Social media corporations as actors of counter-terrorism. New Media & Society, 1(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211035121

- Bouko, C., Naderer, B., Rieger, D., Ostaeyen, P. V., & Voue, P. (2022). Discourse patterns used by extremist Salafists on Facebook: Identifying potential triggers to cognitive biases in radicalized content. Critical Discourse Studies, 19(3), 252–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2021.1879185

- Chetty, N., & Alathur, S. (2018). Hate speech review in the context of online social networks. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40(1), 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.003

- Doosje, B., Moghaddam, F. M., Kruglanski, A. W., de Wolf, A., Mann, L., & Feddes, A. R. (2016). Terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization. Current Opinion in Psychology, 11(1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.008

- Elgot, J., & Dodd, V. (2022, May 16). Leaked Prevent review attacks ‘double standards’ on far right and Islamists. Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/may/16/leaked-prevent-review-attacks-double-standards-on-rightwingers-and-islamists

- Fortin, F., Donne, J. D., & Knop, J. (2021). The use of social media in intelligence and its impact on police work. In J. J. Nolan, F. Crispino, & T. Parsons (Eds.), Policing in an Age of Reform (pp. 213–231). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56765-1_13

- Gerstendfeld, P. B., Grant, D. R., & Chiang, C. P. (2003). Hate online: A content analysis of extremist internet sites. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 3(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2003.00013.x

- Global WebIndex. (2022). The biggest social media trends for 2022. Global WebIndex. https://www.gwi.com/reports/social

- Google. (n.d.). YouTube community guidelines enforcement. Google. https://transparencyreport.google.com/youtube-policy/removals?hl=en

- Grover, T., & Mark, G. (2019). Detecting potential warning behaviors of ideological radicalization in an alt-right subreddit. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 13(1), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v13i01.3221

- Grygiel, J., & Brown, N. (2019). Are social media companies motivated to be good corporate citizens? Examination of the connection between corporate social responsibility and social media safety. Telecommunications Policy, 43(5), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2018.12.003

- Hayden, ME. (2021). We make mistakes: Twitter’s embrace of the extreme far right. Southern Poverty Law Centre. https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2021/07/07/we-make-mistakes-twitters-embrace-extreme-far-right

- HM Govermment. (2015). Counter-extremism strategy (Cm. 9148). Home Office. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/counter-extremism-strategy

- HM Government. (2021). Revised prevent duty guidance: For England and Wales. HM Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prevent-duty-guidance/revised-prevent-duty-guidance-for-england-and-wales#:~:text=The%20Prevent%20strategy%2C%20published%20by,becoming%20terrorists%20or%20supporting%20terrorism

- Johanson, G. A., & Brooks, G. P. (2010). Initial scale development: Sample size for pilot studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(3), 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409355692

- Khawaja, A. S., & Khan, A. H. (2016). Media strategy of ISIS: An analysis. Strategic Studies, 36(2), 104–121. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48535950

- Lyons, I., Turner, C., & Rowan, C. (2022, April 11). Prevent is ‘failing’, say terror experts after murderer Ali Harbi Ali deceived officials. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2022/04/11/prevent-failing-say-terror-experts-murderer-ali-harbi-ali-deceived/

- Macdonald, S., Correia, S. G., & Watkin, A. L. (2019). Regulating terrorist content on social media: automation and the rule of law. International Journal of Law in Context, 15(1), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552319000119

- Meta. (2022). Community standards enforcement report. Meta. https://transparency.fb.com/data/community-standards-enforcement/

- Meta. (n.d.). Hate speech policy details. Meta. https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/

- Molla, R. (2021, March 1). Posting less, posting more, and tired of it all: How the pandemic has changed social media. Vox. https://www.vox.com/recode/22295131/social-media-use-pandemic-covid-19-instagram-tiktok

- Mulcair, C. (2022). Censorship online and hate speech: The case of Reddit. The Mantle. https://www.themantle.com/international-affairs/censorship-online-and-hate-speech-case-reddit

- Osaherumwen, S. (2017). International terrorism: The influence of social media in perspective. World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 3(10), 86–91. https://wwjmrd.com/upload/1509043009.pdf

- Parker, T., & Sitter, N. (2016). The four horsemen of terrorism: It’s not waves, it’s strains. Terrorism and Political Violence, 28(2), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2015.1112277

- Phadke, S., & Mitra, T. (2020). Many faced hate: A cross platform study of content framing and information sharing by online hate groups. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, Hawaii, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376456

- Scrivens, R. (2021). Exploring radical right-wing posting behaviors online. Deviant Behavior, 42(11), 1470–1484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2020.1756391

- Squire, M. (2019, August 7). How big tech and policymakers miss the mark when fighting online extremism. TechTank. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2019/08/07/how-big-tech-and-policymakers-miss-the-mark-when-fighting-online-extremism/

- The White House. (n.d.). The constitution. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/our-government/the-constitution/

- Thukral, P., & Kainga, V. (2022). How social media influence crime. Indian Journal of Law and Legal Research, 4(2), 1–11. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360540601_How_Social_Media_Influence_Crime

- Tsesis, A. (2017). Social media accountability for terrorist propaganda. Fordham Law Review, 86(2), 605–632. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/flr86&id=623&collection=journals&index=

- Twitter. (n.d.). The Twitter rules. Twitter Help Center. https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/twitter-rules#:~:text=Violence%3A%20You%20may%20not%20threaten,and%20glorification%20of%20violence%20policies

- Vocabulary.com. (n.d.). Ideology. Vocabulary.com. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/ideology#:~:text=An%20ideology%20is%20a%20set,socialism%2C%20and%20Marxism%20are%20ideologies

- Weimann, G., & Masri, N. (2020). Research note: Spreading hate on TikTok. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 1(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2020.1780027

- Williams, T. J. V., & Tzani, C. (2022). How does language influence the radicalisation process? A systematic review of research exploring online extremist communication and discussion. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2022.2104910

- Yar, M. (2018). A failure to regulate? The demands and dilemmas of tackling illegal content and behaviour on social media. International Journal of Cybersecurity Intelligence & Cybercrime, 1(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.52306/01010318RVZE9940

Appendix

Facebook, Instagram

Hate speech – https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/.

Violent and graphic content – https://transparency.fb.com/en-gb/policies/community-standards/violent-graphic-content/.

Violent and hateful entities policy – https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/violent-entities.

Hateful Conduct Policy – https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/hateful-conduct-policy.

YouTube

Hate Speech policy – https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2801939.

Violent or graphic content policies: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2802008.

Harmful or dangerous content policies: https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2801964.

Community guidelines – https://policy.pinterest.com/en-gb/community-guidelines.

Tumblr

Community guidelines – https://www.tumblr.com/policy/en/community.

Content policy – https://www.redditinc.com/policies/content-policy.

Snapchat

Community guidelines: https://values.snap.com/en-GB/privacy/transparency/community-guidelines.

Quora

Platform policies: https://help.quora.com/hc/en-us/articles/360000470706-Platform-Policies.

TikTok

Community guidelines: https://www.tiktok.com/community-guidelines?lang=en.