ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the accomplishment of highlighting in multiparty video-mediated learning activities. The focus is on moments of screen sharing and the verbal, embodied, and digital resources participants deploy to draw joint attention to a referent on screen. Drawing on screen recorded data (90 h) from an adult education setting (i.e. online crisis management course) and using multimodal conversation analysis (CA), the paper illustrates that highlighting consists of carefully coordinated conduct, including the mobilisation of the cursor and the selection of parts of text in concert with talk and bodily-visual practices. The analysis shows highlighting as a referential and collaborative practice used: 1) to establish and maintain co-participants’ attention to specific topics and items (e.g. words) during multi-unit turns, and 2) to initiate negotiations of written content. The study contributes to a better understanding of screens and digital objects as collaborative and structuring resources and of how they can be meaningfully deployed in task-based online teaching and learning.

1. Introduction

During the past years, interactional features of technology-mediated settings have been investigated in diverse fields, including education, linguistics, applied linguistics and communication. Video-mediated learning situations, in particular, have drawn an increasing amount of attention among social interaction scholars (e.g. Sert and Balaman Citation2018). Many of the existing studies have revealed the complexities of coordinating social actions when various modalities are simultaneously used (e.g. talking, writing) (e.g. Balaman Citation2021; Melander Bowden and Svahn Citation2020; Sert and Balaman Citation2018). Establishing joint attention and managing screen-based activities along with talk have also been shown to be a practical problem for participants (see e.g. Balaman and Pekarek Doehler Citation2021; Pekarek Doehler and Balaman Citation2021). However, more research is still needed on video-mediated multiparty settings in which participants have limited access to each other’s conduct around structured objects (e.g. screens). The present study aims to fill this research gap by investigating the accomplishment of highlighting in adult learners’ groupwork situations where the participants interact via the Zoom video platform. These situations typically involve one person sharing an online document (e.g. Word document, PowerPoint slides) via the interface and making it thereby visible to co-participants. This paper focuses on the coordination of talk, embodied conduct and screen-based actions in moments when the person controlling the screen selects a piece of a text with the cursor to draw attention to a here-and-now referent on the document (cf. Due and Toft Citation2021). The study emphasises the impact of timing when producing the key highlighting actions, such as cursor movement and text selection, and how they may have different functions in the highlighting sequence and ongoing pedagogical activity.

The data for the study come from an online course that is part of adult experts’ crisis management training, and they are analysed using multimodal conversation analysis (CA). CA enables a detailed examination of the participants’ verbal, embodied, and digital-visual conduct and how they are sequentially and temporally organised in interaction (see Mondada Citation2014; Sidnell and Stivers Citation2013). The findings show highlighting as a situationally constructed referential practice (cf. Goodwin Citation2003; see also Heritage Citation2010) and as the current speaker’s method to establish mutual focus on textual elements on the shared document (e.g. words, phrases, sentences, or paragraphs). It is accomplished via talk, bodily displays and carefully coordinated screen-based actions (i.e. precursory movement of the cursor and text selection) by the person sharing the screen and co-participants’ verbal and embodied displays (e.g. nods). The analysis shows that highlighting is used to draw attention to specific items, to guide co-participants’ attention during multi-unit turns (e.g. accounts and elaborations), and to initiate negotiations of written content. Furthermore, the analysis illustrates how the functions of text selection differ depending on the timing and sequential environment as text selection can be part of turn-initiation or used for confirmation-seeking purposes. The findings shed light on the complexities of coordinating social conduct across modalities and on the affordances digital objects have in organising interaction in pedagogical activities (see also Gibson Citation2014). The study is topical in the fields of education and classroom interaction in that it deals with ways to foster and enhance online educational processes. The results can be used to inform future research and practice, such as teacher training.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Digital objects and highlighting in the organisation of interaction

Previous literature has demonstrated that highlighting is a situated accomplishment, made relevant via the interlocutors’ locally produced conduct that is designed to make some element in the interactional setting stand out and to draw joint attention (e.g. Goodwin Citation1994, Citation2003). The focus of earlier work has been on verbal and bodily-visual practices, such as gesturing and pointing, and on the ways in which material objects feature in the process (e.g. Majlesi Citation2022). Some work has also been done on technologically rich co-present situations, including the use of computers, where digital objects have been found to be used as key structural resources for establishing mutual focus (e.g. Heath and Luff Citation2000; Luff et al. Citation2013). It has been shown that screens themselves can easily draw attention and become part of the “organisational hub” of a given situation (e.g. Cekaite Citation2009; Heath and Luff Citation2000; Hindmarsh and Heath Citation2000; Nissi and Lehtinen Citation2016).

Findings on highlighting that entail the use of the cursor remain scarce. In their recent investigation, Due and Toft (Citation2021) provide a detailed analysis of how participants in an open-office workspace accomplish joint orientation to editing a written text by using the resources in both the physical and digital environment. They conceptualise the combination of actions that include pointing to, talking about and, ultimately, selecting parts of text with a cursor as phygital highlighting, referring to the situated resources in play and “the seamless interplay between bodily and digital actions employed for the social organisation of making some content stand out in order to achieve joint attention” (Citation2021, 4). In a similar vein, in this study, highlighting is conceptualised as a participant’s method to “accountably mark specific details in digital content on a screen, in order to draw joint attention towards this specific aspect of the content” (Due and Toft Citation2021, 1). Other studies have also shown how, in situations where participants are in the same physical setting, the embodied configuration around screens can create a special place to detect and make corrections on shared documents and thereby facilitate the accomplishment of goal-oriented activities (see e.g. Cekaite Citation2009; Greiffenhagen and Watson Citation2009; Musk Citation2016).

Ways to emphasise elements on screen have also been touched upon in studies on technology-mediated (i.e. audio and video mediated) interaction (e.g. Arminen, Licoppe, and Spagnolli Citation2016; Luff et al. Citation2013; Oittinen Citation2022a). In their research on audio-mediated meetings of an international IT-company, Olbertz-Siitonen and Piirainen-Marsh (Citation2021) focus on cursor pointing and illustrate how it becomes a situated activity and a resource for the current speaker to draw co-participants’ attention to a mutual focus point. The study shows how the mobilisation of the cursor is sequentially and temporally coordinated with the ongoing talk, and how pointing as part of first actions (e.g. questions) makes relevant specific next actions (i.e. a response) as well as the negotiation of the participants’ situated roles and responsibilities in the ongoing decision-making process (Citation2021, 16–17). Previous studies have thereby illustrated how the resources for accomplishing mutual focus on a visually perceivable referent on screen vary depending on situational variables and affordances; whereas in co-present settings, one can reflexively mobilise the embodied configuration (e.g. Due and Toft Citation2021), in technology-mediated environments digital resources, such as cursor pointing, may become more prominent. In the latter, access to material and digital structured objects and to co-participants’ visual perspectives is more limited (i.e. one cannot know for sure what others see on their screens), which may have an impact on the practices of carrying out collaborative work.

2.2. Coordinating screen-based actions in video-mediated learning situations

Technology-mediated educational interaction has been increasingly studied from a conversation analytic perspective (see e.g. Dooly and Davitova Citation2018; González-Lloret Citation2015; Jakonen, Balaman, and Dooly Citation2022). Synchronous online sessions have formed an important core of these investigations, and research has been done on both audio-mediated (e.g. Gibson Citation2014) and video-mediated learning situations (e.g. Sert and Balaman Citation2018; see also Jakonen and Jauni Citation2022; Oittinen Citation2022b). These studies have illustrated both the challenges and affordances of technology-mediated settings for organising interaction that vary depending on contextual factors, such as platform features, pedagogical design, and participant configuration (e.g. whether a “talking heads” configuration (see Licoppe and Morel Citation2012) is deployed or some other format).

In studies on video-mediated instructional settings, the teachers’ and learners’ ability to manage screen-based activities along with ongoing interaction (i.e. talk, embodied and screen-based displays) has been highlighted as a key element (e.g. Hjulstad Citation2016; Malabarba, Mendes, and de Souza Citation2022; Pekarek Doehler and Balaman Citation2021; Sert and Balaman Citation2018). The coordination of task-based pedagogical activities is typically described as complex processes that are impacted by the use of individual screens and by the availability of spoken and written communication channels. Additional interactional work and recipient-designed ways to use the available resources, such as shared documents, chat and platform-based features (e.g. cursor), are part and parcel of establishing and maintaining an intersubjective understanding of ongoing events (e.g. Balaman and Pekarek Doehler Citation2021; Melander Bowden and Svahn Citation2020; Oittinen Citationforthcoming). Earlier research has illustrated how the cursor can be used for attention-seeking purposes during hinting sequences (Balaman and Pekarek Doehler Citation2021) and screen-based searches in learner-learner interaction (Uskokovic and Taleghani-Nikazm Citation2022), but up to this date, highlighting has not received a lot of attention. An exception to this is Badem-Korkmaz and Balaman’s (Citation2022) case analysis of a video-mediated foreign language whole class session where they introduce “highlighting aloud” during screen sharing as one of the teacher’s strategies to draw attention to the ongoing discussion and to pursue a response from the learners. The study shows how the shared screen display is meaningfully mobilised as part of the attempt and how, although being also response-indicative in the sequential environment, highlighting is yet locally accomplished through talk and other situated resources.

A body of work has emphasised the ways in which multiple modalities intertwine and impact on collaborative task accomplishment, such as speaking and writing (e.g. Balaman Citation2021; Gibson Citation2014; Li and Zhu Citation2013). The present study contributes to and builds on these earlier findings on social interaction in technologised work and educational settings, focusing specifically on participants’ methods to manage talk and screen-based activities in small-group learning situations. It increases understanding, in particular, of the complexities of managing multiple modalities in video-mediated multiparty interaction, which has not been much studied before, but also of ways to use the cursor so that highlighting becomes a recognised social practice which can, ideally, facilitate the overall educational process.

3. Data and methods

The data for this study come from the context of multinational crisis management training and a two-week course organised in 2021, which took place in an online environment for the first time (Oittinen et al. Citation2021). The topic of the course was the protection of civilians in crisis areas, and it was targeted at people working in different positions and sectors of crisis management. The course tasks and assignments were connected to a scenario-based learning format which was to develop the learners’ in-depth understanding of how to make threat assessments in real-life missions. The database for this study consists of 90 hours of screen-recorded footage, all of which come from sessions where the participants use the Zoom video platform. All ethical guidelines and policies of research integrity were adhered to in the study, including asking the participants to sign an informed consent form. The participants’ identities are protected by using pseudonyms.

There were altogether eighteen learners and six teachers in the course, and they came from diverse cultural and organisational backgrounds, including the military, navy, and educational institutions. The language of the course was English, which is the working language of many multinational crisis management missions. Most of the participants in the recordings speak English as a second or a foreign language, but there are also some native English speakers. All the learners participated in the course from their respective locations, except for some of the teachers and course organisers who were in the same building during the course. The course included daily plenary (i.e. whole group) sessions and meetings in small groups. There were altogether three small groups each of which consisted of six learners and a designated instructor. In the first week, the instructors’ role was to help the groups in community building and to guide their discussions, whereas in the second week, they were to give room for the learners to carry out tasks more independently. During the second week, the groups were given tasks based on the scenario and they had to prepare presentations for the whole group discussions that typically followed the small-group tasks. When working in small groups, it was common that document drafts, materials and templates were shared via the Zoom interface by the instructor or the person acting as the typist.

The methodological framework of the study is multimodal CA, which affords the analyst with the approach and tools to carry out a detailed investigation of talk and multimodal conduct (Mondada Citation2014; Sidnell and Stivers Citation2013; see also Schegloff, Jefferson, and Sacks Citation1977). CA is particularly fruitful for the analysis of talk, gestures, body movement and screen-based behaviours, as it enables detecting the ways in which participants themselves orient to each other’s temporally and sequentially organised actions across modalities. The study is based on a collection of cases from the small-group sessions when text selection is used by the person sharing the screen. Overall, there was great variation among the small groups regarding highlighting, and the selected extracts in this article attempt to show the recurrence and systematicity in those participants who frequently used text selection during screen sharing: an instructor (Jani) in week 1 and a learner (Oili) in week 2. The reason for choosing to focus on highlighting initiated by these two participants is that the instances found in other participants were few and lacked systematic recipient-designed patterns regarding their sequential placement in interaction. To further narrow down the focus, not all cases of cursor highlighting by the selected participants were included in the collection, namely instances where they simply deleted textual elements without any negotiation or uptake from co-participants. Altogether 64 cases of highlighting were analysed in detail (30 by Jani and 33 by Oili), of which 30 were connected to the current speaker’s attempt to draw attention to a specific item or topic on the shared document and 33 to initiate the negotiation of written content.Footnote1 The selected extracts are illustrative of these practices. They have been transcribed employing the conventions developed by Jefferson (Citation2004) and using an applied model of Mondada’s conventions (Citation[2001] 2018) (see APPENDIX).

4. Highlighting as a referential and collaborative practice

The analysis of data shows that highlighting is an important referential practice through which the person sharing their screen can establish mutual focus on some visibly perceivable aspect on a shared document (e.g. a word, sentence, or a phrase). Highlighting consists of moving the cursor over relevant content on screen and selecting a part of a text, both of which are carefully coordinated with other actions, such as talk and gestures (see also Due and Toft Citation2021). It is illustrated how the participants use highlighting to draw attention to specific topics or items relevant to the ongoing activity during multi-unit turns (e.g. as part of accounts and elaborations) (4.1) and to initiate negotiations of written content (4.2). Whereas in the first subsection, the design of the first highlighting turn, including talk and cursor mobilisation, invites co-participants’ contributions to the ongoing activity foremost in implicit ways (e.g. via embodied resources, see also Balaman Citation2021), in the second one, it calls for more explicit co-participation (e.g. providing a response to a teacher’s question or co-editing the shared document). The analysis also shows how the functions of text selection differ in the presented highlighting sequences; depending on its timing and length, it can be used as part of turn-initiation or for confirmation-seeking purposes.

4.1. Highlighting as a practice to draw attention to topics and key items

The findings demonstrate that highlighting is an efficient practice to draw attention to visually perceivable here-and-now referents in multi-unit turns, such as those that include accounts and elaborations. The first extract that illustrates this point comes from a moment in a small-group session that is facilitated by the instructor, Jani. He has opened and shared a Word document with a lot of text and background information relevant for an upcoming task that the learners are supposed to carry out in two smaller groups. He has also reached a page presenting the first task-related question (i.e. “Which body mandated the mission?”) and an extract from a legal framework for crisis management missions and asked whether the group has familiarised itself with the materials prior to the session. Three participants (Simon, Iina and Birgit) either verbally or bodily (i.e. via head shakes) indicate that this is not the case. The extract shows how, after this, Jani spontaneously redesigns the pedagogical activity (i.e. he does not put the learners into small groups but instead introduces the topic; Lines 7–12) and uses highlighting to draw attention to and emphasise specific points on the document (Lines 13 & 16).

Extract 1: “We will go through this”

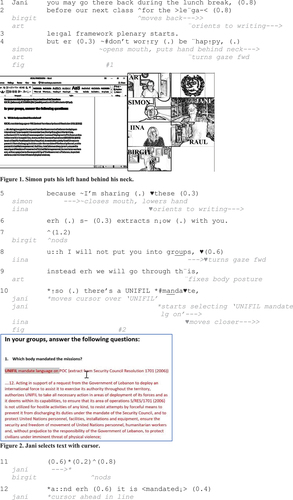

The extract begins with Jani’s long multi-unit turn, with which he first provides a solution and reassurance for the group (Lines 1–4) and then orientates the learners to what is to come: he will go through the materials of the pre-reading task because it had gone unnoticed (Lines 5–6). During this, Simon opens his mouth and puts his left hand behind his neck, orienting potentially to turn-taking (Fig. 1), but since no opportunities to take the floor emerge, he quickly lowers his hands and thereby abandons the trajectory. After a silence of 1.2 seconds and Birgit’s nod that seems to indicate go-ahead (Oittinen Citation2022b), Jani elaborates with an account and explicates the upcoming procedure (Line 8–9). This invites the attention of Iina, who ceases other activities in her local space (i.e. writing) and bodily orients to listening. Art has produced a similar perceivable shift in attention a moment earlier.

Next, Jani produces a boundary marking “so” which prefaces his move to the first point: a question related to the imaginary mission the learners have been working on in the course. As part of mentioning the first relevant content, he starts selecting a phrase on the document that includes the key words of the question (“UNIFIL mandate”; Line 10, Fig. 2). The text selection occurs simultaneously with uttering the latter word aloud, during which Iina moves closer to her screen and thereby indicates heightened attention (Goodwin and Goodwin Citation1986). During the ensuing silence, Jani completes the text selection and Birgit acknowledges the turn with a nod. After this, Jani produces a turn that is an answer to the question visible on screen (“Which body mandated the mission?”; Lines 12–13). It is noteworthy that he does not give a detailed answer verbally but instead uses the formulation “body of UN”, concurrently with selecting the phrase “from Security Council,” which is part of the answer (Fig. 3).

Another long silence (3.3 seconds) ensues, during which Birgit again nods visibly while some other co-participants orient to writing. Keeping the text activated, Jani first produces a sequence expansion, which is an explicit repetition of what the question was, and then a response to it (Lines 15–18). Concurrently with Jani uttering the first part of the response, “UN” (Line 19), Simon shows his understanding by nodding (Line 15–18). It is only after this and a pause of 1.4 seconds that Jani finally deselects the content with his cursor. This occurs right prior to voicing the key information of the answer aloud, “security council”, and a sequence-closing token “okay” (Line 18) to which Birgit reacts by nodding. The placement of inactivating the textual element is important, in that it indicates that the content is no longer relevant for Jani’s turn. In the extract, highlighting is accomplished via Jani’s text selection that occurs simultaneously with uttering the key items and via the co-participant’s locally constructed conduct that, at least ostensibly, function as implicit indications of co-participation (e.g. nods). The sequential environment informs the design of Jani’s highlighting turn(s) (e.g. using lowering intonation and pausing after uttering the selected items) that manifests its attention-seeking purpose.

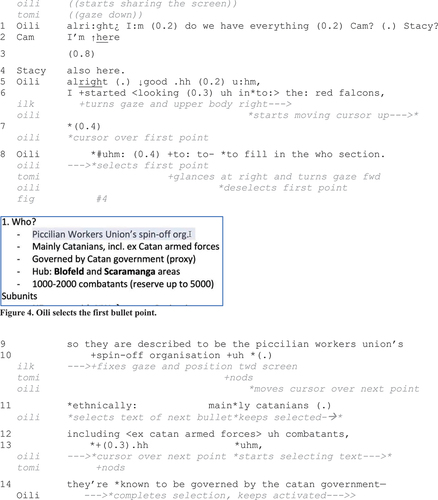

The second extract comes from a small-group session where the learners’ task is to identify and discuss perpetrator strategies in the imaginary crisis scenario. They also need to document their work and present it later, and Oili has agreed to be the typist. In addition to five learner participants (Oili, Kimi, Ilkka, Cam and Stacy), there is a preassigned facilitator (Tomi) and two course organisers behind black boxes (i.e. their names are visible but their faces are not). Before the moment of the extract's beginning, the learners have engaged in individual wok during which everyone has read the relevant learning materials regarding the scenario with a specific area to focus on. Oili’s task has been to find information on the first question regarding who the perpetrator is, which is likely the reason why she goes first. During individual work, she has created a table which she also shares at the beginning of the extract. Thereafter, Oili uses highlighting to draw attention to the list of points she has added to the table, one-by-one, and she does this in close concert with talk (Lines 8, 10 and 13). What is different in the extract compared to the previous one is that only the small-group facilitator, Tomi, and one other learner in addition to Oili, Ilkka, have their cameras on.

Extract 2: “I started looking into”

The extract begins from a moment when Oili starts sharing her screen and, immediately after this, initiates a transition into task-related talk via “alright”, uttering it with a high pitch intonation (Line 1) (see e.g. Filipi and Wales Citation2003). She also inquires if everyone is present, targeting specifically two people, Cam and Stacy, both of whom have their cameras switched off. After receiving a verbal response from both, Oili continues with a sequence-closing “alright” (Ibid.) and an assessment “good”. When she initiates talk about her own topic area, Ilkka turns his gaze to the right and seems to be manipulating the devices in his physical location for a while. When Oili continues, she utters some words at a slower pace and at the same time starts to move her cursor upwards on the bulleted list (Line 6). This indicates a search-in-progress for relevant written content that Oili is orienting to while talking (see also Balaman and Pekarek Doehler Citation2021). Although hesitating, Oili selects the first bullet point about the perpetrator’s identity with a cursor (Fig. 4). The selection is yet reversed quite rapidly, as Oili goes back a step and explicates that her task was to focus on the “who”, Red Falcons (Line 8). After this, she does not reselect the item but produces a so-prefaced account that is followed by reading it aloud. Towards the end of the turn, Ilkka finally ceases other activities and seems to be orienting to listening.

When Oili reaches the end of reading aloud the first bullet point, she utters a pause-indicative “uh”, during which she moves the cursor over the next point in a precursory manner (see also Olbertz-Siitonen and Piirainen-Marsh Citation2021), right prior to selecting it. The selection becomes completed when Oili reads the point aloud (Line 11–12). At the end of this and concurrently with audible pausing (i.e. an in-breath and interjection, “uhm”), Oili similarly selects the next bullet point prior to verbalising the content. Thereafter, Oili deploys a similar procedure with the rest of the points she has written in the column. The extract illustrates how Oili deploys the cursor both to foreground reading aloud what is shared on screen (i.e. it is used as a visual signposting strategy; cf. Oittinen Citation2022a) and to accomplish joint attention on specific phrases. Although there is some perceivable delay in getting everyone’s attention (i.e. at least Tomi and Ilkka seem to be engaged with other activities), it is not treated as problematic in the highlighting sequence or the ongoing activity. Furthermore, as shown in the previous extract, the first highlighting actions in this sequential environment do not make verbal or auditory co-participation relevant, and the person sharing the screen takes silence as a sign of alignment with the ongoing turn. However, in this case most of the co-participants have their cameras off, which can make the role of silence ambiguous.

This section has shown how highlighting can be used to draw attention to specific topics and items and to guide co-participants’ attention during multi-unit turns (e.g. as part of accounts and elaborations), also revealing some of its complexities. The actions that accomplish highlighting include moving the cursor in a precursory manner and selecting written content in close concert with talk (i.e. uttering the key items) and embodied conduct. Although the first highlighting turns in this sequential environment are clearly attention-seeking, they also make implicit displays of co-participation (e.g. turn-acknowledging nods) relevant. However, not having access to the participants’ physical environments limits the possibilities to fully interpret embodied actions, which is a practical challenge to both the participants and researcher.

4.2. Highlighting as a practice to initiate negotiation of written content

In the data, highlighting is also used to initiate negotiation of written content and to establish specific items as learnables (see Majlesi and Broth Citation2012) or negotiables in the ongoing activity. The former connects to teacher’s practices by which in situ sense-making of topics and terminology can be fostered and the latter to learners’ ways to seek confirmation and agreement during independent small-group tasks. These manifest in sequential environments where text selection occurs as part of response-indicative verbal displays, such as questions and rising intonation patterns, and they include keeping the context selected for the duration of the negotiation.

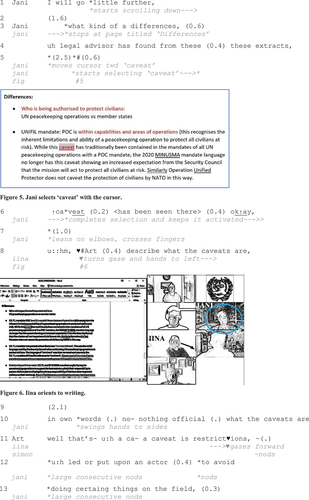

In the next extract, Jani is leading a discussion on the similarities and differences between two mandates, one of them being the UNIFIL mandate used to protect civilians in crisis areas. He has just introduced a page focusing on similarities and now moves on to the differences, which is also the section title on the shared document. As part of accomplishing the transition between the items, he scrolls down the page, selects one of the underlined words in the text, “caveat”, and asks the learners to explain its meaning (Lines 6–8). By doing so, he uses highlighting to emphasise the significance of a task-related concept and to create a special place to negotiate its meaning (i.e. he establishes it as a learnable, cf. Svennevig Citation2018)

Extract 3: “What the caveats are”

When Jani produces the forward orienting formulation, “I will go little further” (Line 1), he starts scrolling down the page and does so until the relevant text is visible. After a 1.6-second pause, and concurrently with the beginning of his question formulation (“what kind of differences”, Lines 3–4), he reaches the slide with the title “Differences”. Although there is a long silence after the question, it is accounted by Jani’s movement of the cursor over the word “caveat” on the shared document. He starts selecting it slowly right before uttering “caveat” emphatically (Fig. 5). Since all the learners’ gazes are fixed towards their screens (i.e. there are no detectable gaze shifts at this point), it can be interpreted as an indication of joint attention (cf. Oittinen Citationforthcoming). Jani’s elaboration that follows reveals that “caveat” is indeed one of the expected answers (Line 6). To summarise, the accomplishment of highlighting includes the prefacing action of moving the cursor over relevant content and selecting it concurrently with verbally drawing the co-participants’ attention to it.

After a brief pause, Jani produces a boundary marking “okay” with a rising intonation and then takes his hands off the keyboard, lifts his elbows on the table and crosses his fingers. By so doing, he orients to further discussion of the term “caveat”. Having the key item still selected, Jani changes the turn-taking format and produces a targeted request to Art (i.e. asks him to explain what caveats are; Line 8). This illustrates how highlighting can be deployed in a prefacing manner and as a response-seeking pedagogical device (cf. Majlesi Citation2022). By asking Art to explain the selected content, the reason for keeping the word “caveat” selected becomes clear: it is not merely about drawing attention to the word but about making it relevant as a learnable (Svennevig Citation2018). Concurrently with Jani’s actions, Iina, who has been orienting to listening, turns her gaze and upper body to her left side and starts typing (Fig. 6). The ensuing silence of 2.0 seconds indicates that the shift in turn-taking is potentially surprising to the learners and something to which they need to adjust. Jani also orients to this and to the possibility of Art not knowing the answer by producing an elaborative account and encouraging Art to use own words that need not to be “official” (Line 10). When Art responds, the others display their agreement with his initial answer by nodding. As Art continues the turn with an elaboration of what he means with “restrictions” (Lines 12–13), Jani displays agreement with large consecutive nods.

What happens after the exchange between Art and Jani is that Jani still keeps the word “caveat” selected and recycles the question to another participant, Simon, invoking thus further discussion on its meaning. In the extract, highlighting is a teacher’s method to establish and maintain mutual focus on a learnable through a series of turns, being thus part of the pedagogical design of the activity. The timing of the first highlighting turn (including cursor movement and text selection) is also important in that it precedes the initiation of a question-answer sequence that becomes extended with the prolonged text selection. The extract thereby illustrates the instuctor’s creative and reflexive ways to draw attention to visual referents and mobilise participation in video-mediated teaching.

The next extract comes from another day of the small-group’s work where Oili is the typist. The learners have just engaged in individual work for 15 minutes during which each participant has had one topic area of perpetrator characteristics on which to find information. During this, Oili has also prepared a table divided into different sections accordingly (motives, tactics, rationales, and capabilities), which the group is now using to organise the discussion. The extract shows how Oili, who is sharing her screen view, deploys highlighting to confirm mutual understanding of the points made by the prior speaker, Kimi, and to provide space to (re)negotiate the written form of selected texts: to make them negotiables in the ongoing activity (Lines 3, 19–23 & 32–33). Kimi’s turn has concerned findings on “motives”, which is also the column where the text selection takes place. Due to the length of the extract, it is divided into two parts (4a & 4b).

Extract 4a: “Just to insert in the big picture”

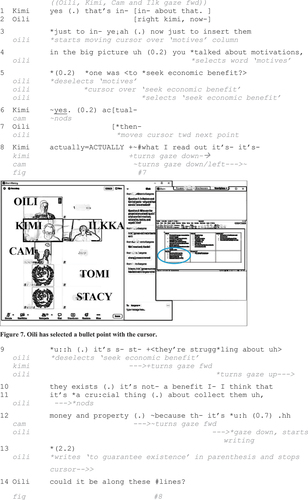

At the beginning of the extract, Oili starts to produce an account and uses the cursor to draw attention to the points she has written to the “motives” column during Kimi’s prior turn. In lines 2–4, Oili first acknowledges Kimi’s turn and then accomplishes a transition that is followed by a prefacing account, “just to insert them in the big picture”. At the same time, Oili starts moving the cursor towards the relevant column and right before uttering “motivations”, she selects the column title, “motives”. During a minor pause (Line 5), she deselects “motives” and, concurrently with uttering the first thing on the list (“seek economic benefit”), selects the same content on the document (Fig. 7). She thereby deploys the practice of “highlighting aloud” (Badem-Korkmaz and Balaman Citation2022). As a reaction to this, Cam nods. Oili’s intonation is slightly rising, which indicates that a response is the relevant next action and highlighting is used for confirmation-seeking purposes. Kimi begins to produce an immediate, complying response uttered in an emphatic manner (Line 6). After a brief pause, he continues with an elaboration in overlap with Oili’s progressive marker “then”, uttered with a continuing intonation, during which Oili also starts moving the cursor towards the next point (Line 7). Kimi interrupts Oili emphatically by producing the contrastive adverb “actually” twice, in an increasingly higher volume, and continues with an explanation. During this, he hesitates, gazes down and thereby indicates searching for the words to describe what he has meant (Lines 8–9; cf. Uskokovic and Taleghani-Nikazm Citation2022). Oili orients to Kimi’s turn continuation by deselecting the content (“seek economic benefit”) and stopping the cursor, by which she indicates putting her own trajectory on hold.

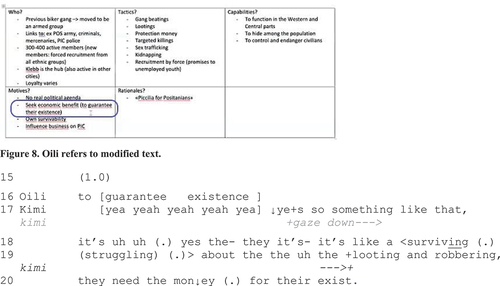

When Kimi proceeds, he still struggles to make his point, to which Oili reacts by gazing upwards for a while, as if trying to think about a solution as well. Kimi continues by refuting a specific word Oili has written, selected, and said aloud: “(it’s not a) benefit”. Oili acknowledges this via a nod. Towards the end of Kimi’s turn, which is left incomplete (Line 12), Oili gazes down and starts reformulating in writing what Kimi just said. During the silence of 2.2 seconds that ensues, Oili writes another content (“to guarantee existence”) that she places in parenthesis after the original bullet point. She then draws Kimi’s attention to this written candidate solution by leaving the cursor next to it and producing a question including a deictic expression (“could it be along these lines”, Line 14; Fig. 8). It is noteworthy that she produces an implicit, written correction of the word “existence” that Kimi has mistakenly uttered as “exists” in his spoken turn. Although Kimi complies with the formulation, he only partially agrees (“something like that”) (Line 17), after which he continues to elaborate and rephrase his point (Lines 18–20). The extract illustrates how Oili’s first highlighting turn has an important confirmation-seeking function: it is designed to ensure mutual understanding and agreement over written content and to assign Kimi responsibility for either accepting or rejecting it (cf. Olbertz-Siitonen and Piirainen-Marsh Citation2021).

When the situation proceeds, Oili continues to use highlighting to seek confirmation regarding the remaining points raised by Kimi (i.e. what she has written in the “tactics” column). The last extract shows how selecting multiple items on the list leads to the negotiation of their placement on the shared document (Lines 21–27) and, eventually, to closing the sequence (Lines 34–40). These induce verbal involvement of Cam and Kimi, but also another written modification by Oili (i.e. adding one more bullet point in the column).

Extract 4b: “Did I catch them all”

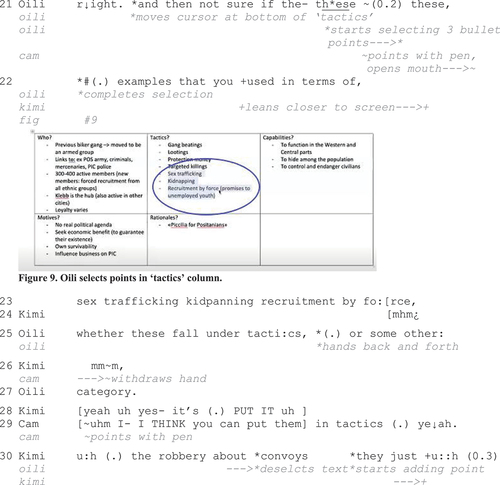

In the extract, Oili initiates negotiation of written content regarding the location of the text on the shared document (Lines 21–25). She explicitly mentions not being sure whether the points are suitably placed in the “tactics” column or if they should be placed elsewhere. Oili uses highlighting for confirmation-seeking purposes and initiates it by producing an indirect question and by concurrently selecting the three relevant bullet points (Fig. 14). The text selection occurs at the same time with uttering the indexical pronoun “these”, which shows the strong connection between the verbal reference and the on-screen action and the how they become an assemblage intelligible in the moment (see Due and Toft Citation2021). Kimi orients to this by leaning closer to the screen, as if trying to ensure better visual access to the selected content. After completing the selection, Oili leaves it active and reads aloud the points (Lines 25–27; cf. Badem-Korkmaz and Balaman Citation2022). Towards the end of Oili’s turn, Kimi first acknowledges the question via “mm”, agrees and then continues with an imperative phrase “put it”. Cam, who has indicated an attempt to take the floor already earlier (in Line 21), begins to talk at the same time and produces an agreeing formulation. However, it receives no uptake; instead, Kimi continues his turn (Line 30).

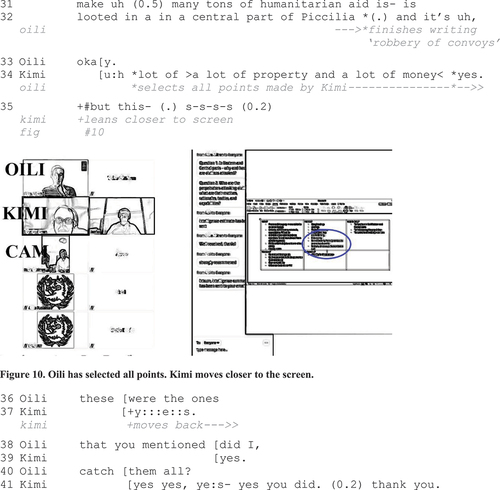

After some hesitation, Kimi introduces another point to be added to which Oili orients by deselecting the items and starting writing (Lines 30–32). While Kimi elaborates on the point, Oili finishes and produces an in-turn acknowledgement of the turn, “okay”. Although Kimi still continues, Oili starts selecting the modified list of points on “tactics” with the cursor. Kimi indicates noticing of this by speeding up and leaving the turn incomplete for the duration of leaning closer to the screen (Lines 35–36, Fig. 10). After this, Oili seeks for a confirmation from Kimi regarding whether the selected points include everything that Kimi has said (Lines 36–40). Kimi, in turn, produces multiple complying responses and during this displays orientation to close the sequence by leaning back. He also thanks Oili, which brings the topic to a close. It is noteworthy that Oili keeps the points selected until Kimi has finished his confirmation turn, and it is only along with the transition into the next point that she finally deselects them.

This subsection has shown that highlighting is a practice used to invite the negotiation of written content than can have to do with its meaning, form, or location on the shared document. Furthermore, highlighting was seen as a situated practice to promote joint sense-making, to establish specific items as negotiables and to seek confirmation or agreement. In relation to the latter, it was illustrated how text selection that occurs at the imminence of response-indicative first turns (e.g. questions or accounts with rising intonation patterns) may call for responses that help co-editing texts and constructing shared authorship (see also Due and Toft Citation2021; Greiffenhagen and Watson Citation2009). Although the typist has authority over the written modality in these situations, highlighting can function as a means to invite active co-participation in different phases of the writing process.

5. Concluding discussion

This study has investigated the accomplishment of highlighting in multiparty video-mediated activities of a crisis management course. For this, the methodological framework of multimodal CA was deployed. The findings illustrate that highlighting is an important collaborative practice used to: 1) to draw the co-participants’ attention to a specific point or item, a here-and-now referent, on a shared online document, and 2) to invite the negotiation of written content. Furthermore, highlighting was found to invoke different forms of co-participation, depending on its sequential environment and on the multimodal resources deployed in its accomplishment (e.g. timing and length of text selection). The study gives insights into the complexities of using digital tools, namely the cursor, in distributed learning situations in which video and other channels for communication are simultaneously used (see also Balaman Citation2021; Melander Bowden and Svahn Citation2020)

The analyses showed that highlighting is a referential and situated practice designed to establish mutual focus on textual elements visible to everyone via shared screen. It was accomplished via careful coordination of talk, embodied conduct, and screen-based activities (i.e. precursory cursor movement and text selection). The first analytic section (Extracts 1–2) showed highlighting as an effective current speaker’s strategy to draw and guide the co-participants’ attention during multi-unit turns (e.g. elaborations) and thereby sustain mutual understanding of ongoing events. The design and timing of the first highlighting actions produced by the person sharing the screen were important in that they invited implicit displays of co-participation (e.g. embodied acknowledgement tokens). However, interpreting reciprocal embodied behaviours (e.g. gaze direction and nods) of co-participants in moments where a vocal response is not invited was not straightforward, which also depicts the challenges video-mediated environments set for the participants for organising their conduct.

The second analytic section illustrated moments when highlighting was used to create a space to (re)negotiate the written content. The negotiations were connected to the meaning, form, and location of textual elements on the shared document, and they entailed establishing specific items as learnables (Majlesi and Broth Citation2012) or negotiables in the ongoing interaction. In these cases, the first highlighting actions were designed so that their organisation called for more explicit co-participation (Extracts 3–4). The verbal resources to instigate these moments included questions and accounts with rising intonation patterns and deploying the resource of prolonged text selection (i.e. deselecting written content only after the negotiation is complete). Unlike in collaborative tasks of co-present situations around computers (see Due and Toft Citation2021), the participants were not able to deploy embodied referential practices (e.g. pointing), which made verbalisation, bodily-visual adjustments to the conditions of the video-mediated environment (e.g. leaning over) and the use of the cursor prevalent in the moment. The participants thus used both auditory (e.g. boundary markings and deictic expressions) and digital-visual resources as assemblages (cf. Due and Toft Citation2021) to ensure joint attention and agreement. In cases of collaborative writing, highlighting was also shown as a sequential environment that can create opportunities for co-editing and establishing shared authorship over the written content (cf. Stevanovic and Peräkylä Citation2012).

The study has taken a bottom-up interactional approach to online collaborative activities and to the ways in which participants orient to the affordances of the socio-digital setting (e.g. Luff et al. Citation2013; Olbertz-Siitonen and Piirainen-Marsh Citation2021). It has given insights into the ways in which access to digitally shared objects is established not only multimodally but across modalities, contributing to the growing body of work on how the varying organisations of talk, bodily conduct and screen activities figure in the process (e.g. Balaman Citation2021; Sert and Balaman Citation2018). Although the role of the person sharing the screen was found pivotal in the setting (i.e. this person had special rights to control what was shown and when), highlighting was yet shown as a collaborative practice. The present study also contributes to a better understanding of verbal, embodied and digital resources in video-mediated task-based interaction (e.g. Malabarba, Mendes, and de Souza Citation2022; Pekarek Doehler and Balaman Citation2021). Unlike previous studies that have focused on collaborative work on platforms and settings where access to shared documents is not restricted (e.g. Balaman Citation2021), this paper has shown the affordances and limitations of collaborating in situations in which everyone can see but not modify what is shown on the screen. The study has implications for teaching and learning and for developing practices that are more inclusive by nature (Moorhouse, Li, and Walsh Citation2021; see also Oittinen Citation2022b). It is suggested that, in the future, more attention is given to both practitioners’ and learners’ abilities to carry out and support task accomplishment in environments with multiple channels of communication (Gibson Citation2014) and use this information in (teacher) training.

Although the focus of the present study was mainly on the practices of two participants, the findings can help inform future design for teaching in video-mediated learning (e.g. what kind of instructions to give and how to use the tools). They can also be used to develop collaborative work practices and tasks that are suitable for online environments more generally. More research is still called for on the detailed organisation of instructional settings where video platforms are used, and on the ways in which these organisations may change over time and across settings.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (247.9 KB)Acknowledgements

I wish to thank all the course participants, especially the trainees, instructors, and course coordinators, for taking part in the study and for letting members of the PeaceTalk project to observe their important and invaluable work. I am grateful to FINCENT, the Finnish National Defense University and my fellow PeaceTalk researchers for their support. Thank you also to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments on the earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2023.2259020.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Written content refers to the texts that either the teachers or learners have produced and becomes visible via screen sharing.

References

- Arminen, I., C. Licoppe, and A. Spagnolli. 2016. “Respecifying Mediated Interaction.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 49 (4): 290–309.

- Badem-Korkmaz, F., and U. Balaman. 2022. “Eliciting Student Participation in Video-Mediated EFL Classroom Interactions: Focus on Teacher Response-Pursuit Practices.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2022.2127772.

- Balaman, U. 2021. “The Interactional Organization of a Video-Mediated Collaborative Writing: Focus on Repair Practices.” TESOL Quarterly 55 (3): 979–993. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3034.

- Balaman, U., and S. Pekarek Doehler. 2021. “Navigating the Complex Social Ecology of Screen-Based Activity in Video-Mediated Interaction.” Pragmatics 32 (1): 54–79.

- Cekaite, A. 2009. “Collaborative Corrections with Spelling Control.” International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning 4 (3): 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-009-9067-7.

- Dooly, M., and N. Davitova. 2018. “What Can We Do to Talk More?’: Analysing Language learners’ Online Interaction.” Hacettepe Egitim Dergisi 33:215–237. https://doi.org/10.16986/HUJE.2018038804.

- Due, B., and T. Toft. 2021. “Phygital Highlighting: Achieving Joint Visual Attention When Physically Co-Editing a Digital Text.” Journal of Pragmatics 177:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.01.034.

- Filipi, A., and R. Wales. 2003. “Differential Uses of okay, right, and alright, and Their Function in Signaling Perspective Shift or Maintenance in a Map Task.” Semiotica 2003 (147): 429–455. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.2003.102.

- Gibson, W. J. 2014. “Sequential Order in Multimodal Discourse: Talk and Text in Online Educational Interaction.” Discourse & Communication 8 (1): 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481313503222.

- González-Lloret, M. 2015. “Conversation Analysis in Computer-Assisted Language Learning.” Galico Journal 32 (3): 569–594. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v32i3.27568.

- Goodwin, C. 1994. “Professional Vision.” American Anthropology 96 (3): 606–633. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100.

- Goodwin, C. 2003. “Pointing as Situated Practice.” In Pointing: Where Language, Culture, and Cognition Meet, edited by S. Kita, 217–242. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Goodwin, M. H., and C. Goodwin. 1986. “Gesture and Coparticipation in the Activity of Searching for a Word.” Semiotica 62 (1/2): 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1986.62.1-2.51.

- Greiffenhagen, C., and R. Watson. 2009. “Visual Repairables: Analyzing the Work of Repair in Human-Computer Interaction.” Visual Communication 8 (1): 65–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357208099148.

- Heath, C., and P. Luff. 2000. Technology in Action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. 2010. “Conversation Analysis: Practices and Methods.” In Qualitative Sociology, edited by D. Silverman, 208–230. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Hindmarsh, J., and C. Heath. 2000. “Sharing the Tools of the Trade: The Interactional Constitution of Workplace Objects.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 29 (5): 523–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124100129023990.

- Hjulstad, J. 2016. “Practices for Built Space in Videoconference-Mediated Interactions.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 49 (4): 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1199087.

- Jakonen, T., M. Balaman, and U. Dooly. 2022. “Interactional Practices in Technology-Rich L2 Environments in and Beyond the Physical Borders of the Classroom.” Classroom Discourse 13 (2): 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2022.2063547.

- Jakonen, T., and H. Jauni. 2022. “Managing Activity Transitions in Robot-Mediated Hybrid Language Classrooms.” Computer Assisted Language Learning 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2022.2059518.

- Jefferson, G. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by G. H. Lerner, 13–31. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.125.02jef.

- Licoppe, C., and J. Morel. 2012. “Video-In-Interaction: “Talking Heads” and the Multimodal Organization of Mobile and Skype Video Calls.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 45 (4): 399–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.724996.

- Li, M., and W. Zhu. 2013. “Patterns of Computer-Mediated Interaction in Small Writing Groups Using Wikis.” Computer-Assisted Language Learning 26 (1): 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2011.631142.

- Luff, P., M. Jirotka, N. Yamashita, H. Kuzuoka, C. Heath, and G. Eden. 2013. “Embedded Interaction: The Accomplishment of Actions in Everyday and Video-mediated Environments.” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 20 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/2442106.2442112.

- Majlesi, A. R. 2022. “Gestural Matching and Contingent Teaching: Highlighting Learnables in Table-Talk at Language Cafés.” Social Interaction, Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v5i2.130871.

- Majlesi, A. R., and M. Broth. 2012. “Emergent Learnables in Second Language Classroom Interaction.” Learning, Culture & Social Interaction 1 (3–4): 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.08.004.

- Malabarba, T., A. C. O. Mendes, and J. de Souza. 2022. “Multimodal Resolution of Overlapping Talk in Video-Mediated L2 Instruction.” Languages 7 (2): 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020154.

- Melander Bowden, H., and J. Svahn. 2020. “Collaborative Work on an Online Platform in Video-Mediated Homework Support.” Social Interaction, Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 3 (3). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v3i3.122600.

- Mondada, L. (2001) 2018. “Conventions for Multimodal Transcription.” https://franz.unibas.ch/fileadmin/franz/user_upload/redaktion/Mondada_conv_multimodality.

- Mondada, L. 2014. “The Local Constitution of Multimodal Resources for Social Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 65:137–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004.

- Moorhouse, B. L., Y. Li, and S. Walsh. 2021. “E-Classroom Interactional Competencies: Mediating and Assisting Language Learning During Synchronous Online Lessons.” RELC Journal 54 (1): 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220985274.

- Musk, N. 2016. “Correcting Spellings in Second Language learners’ Computer-Assisted Collaborative Writing.” Classroom Discourse 7 (1): 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2015.1095106.

- Nissi, R., and E. Lehtinen. 2016. “Negotiation of Expertise and Multifunctionality: PowerPoint Presentations as Interactional Activity Types in Workplace Meetings.” Language & Communication 48:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2016.01.003.

- Oittinen, T. 2022a. “Material and Embodied Resources in the Accomplishment of Closings in Technology-Mediated Business Meetings.” Pragmatics 32 (3): 299–327. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.19045.oit.

- Oittinen, T. 2022b. “Negotiating Collaborative and Inclusive Practices in University students’ Group-To-Group Videoconferencing Sessions.” Linguistics and Education 71:71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2022.101107.

- Oittinen, T. Forthcoming. “Including Written Turns in Spoken Interaction: Chat as an Organizational and Participatory Resource in Video-Mediated Activities.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 4.

- Oittinen, T., P. Haddington, A. Kamunen, and I. Rautiainen. 2021. “PeaceTalk Video Corpus pt. 3 (Protection of Civilians Online Course).” http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:att:da20376a-91a0-4e31-b006-1da89468bc3a.

- Olbertz-Siitonen, M., and A. Piirainen-Marsh. 2021. “Coordinating Action in Technology Supported Shared Tasks: Virtual Pointing as a Situated Practice for Mobilizing a Response.” Language & Communication 79:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2021.03.005.

- Pekarek Doehler, S., and U. Balaman. 2021. “The Routinization of Grammar as a Social Action Format: A Longitudinal Study of Video-Mediated interactions.”Research on Language and Social Interaction.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 54 (2): 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2021.1899710.

- Schegloff, E., G. Jefferson, and H. Sacks. 1977. “The Preference for Self-Correction in the Organization of Repair in Conversation.” Language 53 (2): 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1977.0041.

- Sert, O., and U. Balaman. 2018. “Orientations to Negotiated Language and Task Rules in Online L2 Interaction.” ReCALL 30 (3): 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344017000325.

- Sidnell, J., and T. Stivers, Eds. 2013. The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118325001

- Stevanovic, M., and A. Peräkylä. 2012. “Deontic Authority in Interaction: The Right to Announce, Propose and Decide.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 45 (3): 297–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.699260.

- Svennevig, J. 2018. “’what’s It Called in Norwegian?’ Acquiring L2 Vocabulary Items in the Workplace.” Journal of Pragmatics 126:68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.10.017.

- Uskokovic, B., and C. Taleghani-Nikazm. 2022. “Talk and Embodied Conduct in Word Searches in Video-Mediated Interactions.” Social Interaction: Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 5 (1). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v5i2.130876.

APPENDIX

Transcription conventions (Jefferson Citation2004; Mondada Citation[2001] 2018)