ABSTRACT

In this paper, we examine the role of principals in making schools more inclusive, which means enabling joint learning of all students. The article draws on empirical investigations from 2700 pages of legal documents on how international policies have been handled in two particular national contexts, Germany and Norway. We regard, in particular, school principals’ responsibilities for inclusive schools. The comparative design reveals the following findings: From a historical perspective, expectations for principals to open their schools for all learners has shifted from low-stake to high-stake governance means starting with solely stating general responsibilities of principals. Since this approach has not resulted in desired outcomes like making school organisations more inclusive, responsibilities have been coupled more with accountability. With this, the work of principals has become more complex and has been coped with differently in different contexts. German principals have wide areas of responsibility in a restricted scope of action because their work is embedded in highly developed but inflexible bureaucratic structures. Norwegian principals face sole responsibility with outcome-oriented accountability and even penalties in case of not achieving certain standards. The latter approach opens schools for “more” children with varying needs but is also more challenging for principals.

Introduction

This paper describes the development of expectations towards principals in different national contexts (Germany and Norway) and explains similarities and differences. For this purpose, it uses the policy goal of making school systems more inclusive as an example to understand education dynamics about nation-specific particularities. International agreements that oblige states to work actively to enable all people, independently from their conditions, to take part in all parts of society must be implemented in specific contexts. Such implementation processes reveal how various solutions are chosen in various historical and spatial contexts. They also illustrate how reform trajectories evolve in iterative processes (Wermke & Forsberg, Citation2023).

The UNESCO Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education from (Citation1994) is the point of departure to investigate how normative policies focused on inclusion are operationalised as responsibilities and accountability systems of school principals in various contexts. The paper’s central ambition is not to understand the nature of inclusion as an education policy whose implementation is rendered by various stakeholders. Instead, we take the inclusion movement and its ambition to open mainstream schools for all children as an example to investigate regulation histories for school principals.

Organising inclusive schooling is a key challenge issued by international pressure, like the Salamanca Statement (Citation1994) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) from 2006. This is implemented step by step, processing expectations to school principals and changing responsibilities and accountabilities. Principals are situated between statutory provisions for inclusive schooling and challenges in practical implementation. They must decide and make sense of constantly changing policies, even though the path is not clearly defined (Badstieber, Citation2021; Knutsen & Emstad, Citation2021). Therefore, investigating school principals’ work in implementing inclusion policies will reveal insights into regulation histories of various contexts and different scope of actions manifested by principals.

Against this backdrop, our paper asks: How are school principals’ responsibilities depicted in regulations in Germany and Norway regarding the implementation of inclusion policies since 1994? Moreover, how are school principals in both national contexts made accountable for their work towards a school for all?

Germany and Norway are particularly interesting for this comparison. Even though they differ in their educational traditions, they have similarities in later educational reforms, influenced by international trends, like inclusion and more school autonomy with accountability. Local education systems play a vital role in this (Aasen et al., Citation2012; Wissenschaftlicher Dienst des deutschen Bundestages, Citation2020). However, similarities in country comparison can present evidence for universalities in the matter of principals’ responsibility in relation to inclusion. Differences instead might point to government-specific particularities. Because of Germany’s complex multi-tracked school system and its comparability with Norway, this article focuses on primary education.

The paper is disposed in the following way: after presenting research on leading inclusive schools, the focus is first set on a context description of both countries. Afterwards, our methodological design is explained before finally presenting the results and their discussions.

Research on leadership for inclusive schools

Several global trends have significantly affected national school systems since the end of the 20th century. One has been the powerful movement towards an inclusive school for all, represented by the Declaration of Salamanca in Citation1994, accelerated by the CRPD in Citation2006. Its overall vision is that

all children should learn together, wherever possible, regardless of their difficulties or differences. Inclusive schools must recognize and respond to the diverse needs of their students, accommodating both different styles and rates of learning and ensuring quality education to all through appropriate curricula, organizational arrangements, teaching strategies, resource use, and partnerships with their communities. (UNESCO, Citation1994, p. 11)

These kinds of policies must be implemented internationally, nationally, and locally. The school principal is an important stakeholder in the process from intended to enacted policy (Moos, Nihlfors, & Paulsen, Citation2016). Educational leadership is a major determinant of school changes and developments (Rorrer, Skrla, & Scheurich, Citation2008). Principals have to ensure the implementation of international and national legislation. In contrast, they must consider local conditions: “The gap school leaders manage is the gap between ensuring the school fulfills legal requirements in a proper way and at the same time taking the local established school culture into account”Footnote1 (Knapp, Citation2020, p. 178). School principals are assumed to be central to inclusion (Badstieber, Citation2021).

Several international studies are especially focusing on school leadership in inclusive school settings with focus on principals’ attitudes (Bailey & du Plessis, Citation1997), comparing which leadership model would nurture inclusive school settings (Kugelmass & Ainscow, Citation2004), analysing the work of one successful school principal (Hoppey & McLeskey, Citation2013) or presenting the prominent role of national and regional educational administrators instead of school principals in organising inclusive schooling (Ainscow, Citation2020). Even though the studies have different approaches to inclusion, reaching from the placement of students with special needs in ordinary classrooms to an understanding of the diversity of all learners, they have something in common: school principals play a vital role in the implementation of (successful) inclusive practices at school, but cannot solve this “major challenge” alone. Collaboration and participation from all stakeholders and additional resources are needed. Ainscow (Citation2020) even calls upon policy documents based on a clear and widely understood definition of inclusion and equity, where leadership is mentioned as a principle that guides the work of teachers.

For the German case, few studies focus on school leadership concerning the system and stakeholders surrounding them (Brauckmann, Schwarz, Brauckmann, & Felici, Citation2015). The topic of school autonomy in general has been widely discussed since the 2010s since several federal states are working with a model of so-called autonomous schools (Blossfeld et al., Citation2010; Heinrich, Citation2006; Rürup, Citation2019; Wissenschaftlicher Dienst des Deutschen Bundestages, Citation2020; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, Förster, & Preuße, Citation2012). Interestingly, these investigations work with schools, not school principals. However, one broader study investigated school leaders’ areas of responsibility. Hanssen (Citation2013) analysed German school laws regarding school principals’ task allocations. It brings out difficulties in the collaboration between school principals and system-level educational administrators, highlighting the imbalance between responsibility and accountability. However, since this analysis is from 2013, it does not display the contemporary situation but will reveal insights for further work. In studies about German school leadership, inclusive education is getting more attention. For example, Badstieber and Amrhein (Citation2021) conducted questionnaires and interviews in ten federal states with principals from secondary education, figuring out that school principals see themselves as active transformers in implementation processes. Furthermore, school principals’ understanding of inclusion is incredibly important. Another study, working in one federal state, introduced several leadership models from school principals from so-called “focus schools” (with an emphasis on inclusive education) and their approaches (Scheer, Citation2020). Amrhein (Citation2011) furthermore interviewed secondary education teachers. One result was the characterisation of the role of school principals in implementing inclusive schooling as an intermediary actor between school authorities and school staff.

In Norway, educational leadership research focuses on the interplay between school principals and educational administrators and perceived steering and control regarding political changes (Wermke, Jarl, Prøitz, & Nordholm, Citation2022; Wermke, Nordholm, Andersson, & Kotavuopio-Olsson, Citation2023). The study from 2023 shows how school principals are governed by laws and curriculum, comparing several countries, while Norwegian principals experience slightly more autonomy than principals from Finland and Sweden. Wermke, Jarl, Prøitz, and Nordholm (Citation2022) show the significant role of historical and nation-specific particularities in governing schools. Moos, Nihlfors, and Paulsen (Citation2016) even report how local discourses differ from national and international politics and emphasise the role of school authorities. Others again show the importance of school principals’ work with regulations in implementing reforms. For example, Prøitz, Rye, and Aasen (Citation2019) present control signals from national authorities as the basis for the development of everyday school life. They show that school principals indeed interpret and work with national policies and that there are diverse ways in translating them into pedagogical practice. Abrahamsen and Aas (Citation2019) highlight the importance of government propositions to the Norwegian Parliament in this process. In all these studies, the aspects of autonomy, accountability, and New Public Management and more complex task allocations for school principals play a key role.

Few studies cover inclusive policies in the analysis of educational leadership. One study especially worked out leading strategies for the development of inclusive lessons. Two main responsibilities are developing teacher competencies and tracing learning outcomes (Knudsmoen, Mausethagen, & Dalland, Citation2022). Collaborating with teachers on inclusion issues is important for school principals (Knutsen & Emstad, Citation2021). They also mention decision-making and responsibilities to identify needs and potential of students.

Neither international nor national studies conducted in Germany and Norway regarding school principals’ role in the implementation of inclusion policies have analysed different school legislation, and principals’ task allocations manifested there, even if it is known that these stakeholders are situated between statutory provisions for inclusive schooling and challenges in the practical implementation with uncertain responsibilities. On one side, principals are supposed to ensure the implementation of reforms and improvement of their school and its outcomes. Conversely, their actual scope of action regarding an inclusive school setting is still unclear. Furthermore, school principals are acting between conflicting priorities of different stakeholders, like education authorities, legal guardians, pupils, and teachers affecting their role (Wermke, Nordholm, Andersson, & Kotavuopio-Olsson, Citation2023). Investigating school principals’ task allocations manifested in legal texts will pinpoint significant relations of what policy in various contexts intends in schools for all children.

Leading inclusive schools in context

Germany and Norway are interesting to compare due to many similarities in later education reforms that significantly affected educational leadership. One of these reforms is the shift towards inclusive schooling. Germany and Norway have both signed the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (Citation1994) and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The more recent CRPD states that all students should have equal access to inclusive, free education with equal opportunities (United Nations, Citation2006). Both countries therefore refer to the same starting point as to what inclusive education should look like. Nevertheless, despite some more precise descriptions, the statement leaves room for one’s own interpretation and national implementation. However, these statements and their accompanying reforms are embedded in different educational traditions. Countries differ in their education systems, with a bureaucratised, tracked approach in Germany and a comprehensive one in Norway.

Germany, for example, sees joint learning of pupils with and without disabilities as the basis of inclusive education. It goes on to say that “inclusive education enables children and young people with disabilities or with special educational needs to have equal access to all educational offerings, to offers of various educational courses and to school life” (Kultusministerkonferenz, Citation2011). Inclusive education is furthermore often seen in the context of special educational support and is closely linked to the diagnosis of a disability and corresponding special educational needs (Klemm, Citation2021; Sekretariat der Ständigen Konferenz der Kultusminister der Länder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Citation2021). In Norway, on the other hand, inclusive education is about all children experiencing “that they belong. They should feel safe and discover that they are valuable and that they are able to help shape their own learning. An inclusive environment welcomes all children and pupils” (Meld. St. 6 (Citation2019–2020), p. 11). In the basic definition of inclusive education, the focus in Norway, unlike in Germany, is not on disability and special needs education but on all pupils.

However, the two countries resemble each other in their method of system regulation (Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2021). The educational systems emphasise learning outcomes and pupils’ personal growth, where principals play a vital role (Grissom, Blissett, & Mitani, Citation2018).

The work of German principals

Education policy in Germany is executed in 16 federal states with individual educational systems and regulations. The decision-making power lies within the federal states. Still, a Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (Kultusministerkonferenz, KMK) was established nationally to harmonise the different educational systems and policies. Even though the whole education system is under governmental supervision, federal states are responsible for legislation and administration; the German constitution contains fundamental regulations for education (Döbert, Citation2015).

The Board of Education (Schulbehörde) is subordinated to the respective federal states’ Ministry of Education. They are responsible for the so-called internal school affairs, which means the education systems’ organisation, administration, and supervision. They also regulate educational goals. School authorities within municipalities and cities (Schulträger) handle external school affairs, like buildings, interior and teaching and learning aids (Sekretariat der Ständigen Konferenz der Kultusminister der Länder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Citation2021; Wermke, Freier, & Nordholm, Citation2023).

The structure of the German educational system has not changed in decades (Döbert, Citation2015). However, occasionally, there have been discussions regarding educational autonomy at the state, federal state, and municipality levels. In the 1980s, schools received more freedom to develop their school quality, educational programme, and learning environment. The federal states supplied recommendations and scripts, but these offers were no specific concepts until the 1990s and the emergence of New Public Management and cost-performance-analysis in schools. Single schools have more scope of action for local apposite use of personnel, time, and money. This led to comprehensive changes in the former central regulated top-down action planning and implementation (Rürup, Citation2007; Thiel, Citation2019).

Concurrent accountability was getting a legal basis, implemented through concrete methods for achieving educational goals and evaluation within schools. After insufficient PISA results in Citation2001, the German state wanted to ensure the development of quality and quality management. A new proportion between framework requirements and flexible supporting structures for the mostly autonomous working schools was needed (Wissenschaftlicher Dienst des Deutschen Bundestages, Citation2020). National educational standards were implemented, and

there was a common movement in the German federal states to open up additional decision-making leeway for individual schools, combined with a strengthening of school principals and the development of systematic educational monitoring, consisting of tests, school inspections and based on that, public reports respectively performance agreements and target agreements between the board of education [on federal state level] and individual schools. (Rürup, Citation2019, p. 66)

Federal states were increasingly influencing schools through this monitoring and the approval of school programmes. Personal supervision and advice by state school authorities for principals lost their importance (Kuper, Citation2020; Sekretariat der Ständigen Konferenz der Kultusminister der Länder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Citation2021).

The expectation of principals has changed from being “rule-bounded administrators” to “entrepreneurial managers” (Mintrop, Brauckmann, & Felici, Citation2015). Wissinger (Citation2011) subsequently identified two main tasks of educational leaders: the improvement of student performance and the implementation of educational policy and micropolitical reforms (strategic management apart from organisational goals) as a response to demands of a profoundly changed school environment and a school in need of reorganisation. Simultaneously, governing through tests and inspections is more used for other sociopolitical requirements. For example, the implementation of inclusive education is controlled through inspections. This approach makes the issue from the government, implementing inclusive schooling, to one from school principals and schools.

The work of Norwegian principals

Norway is divided into 356 municipalities, organised into eleven counties. While counties govern upper secondary schools, municipalities are responsible for primary and lower secondary schools. Municipalities were strengthened in their rights with “kommuneloven” in Citation1992, leading to a decentralisation of the school system (Engeland & Langfeldt, Citation2009). The expectation that the state can regulate an equal offer for education through detailed regulation and governance has been replaced by the confidence that teachers, school principals, and municipalities as school owners can work best when following national aims (clearly defined through the Curriculum) and leading students to national competence standards (Aasen et al., Citation2012). Due to different sizes of municipalities and diverse competencies, various approaches emerged, resulting in different educational offers, quality outcomes of education, and divergent demands from the municipalities to the state (Aasen et al., Citation2012; Prøitz, Novak, & Mausethagen, Citation2022).

For this reason, the Norwegian state changed schools’ governing from input- to more outcome-control, leading to a new, goal and result-oriented educational reform in Citation2006 (Aasen et al., Citation2012). They emphasised school principals as the professionals closest to the conditions of students’ learning and results. However, it was determined that principals need a framework for their work, manifested in a national quality assessment system. Much of the implementation work was dedicated to school principals, also from municipalities. However, due to a lack of competencies from local educational authorities and school principals during this implementation process, the national governance and follow-up of results were strengthened again. Still, detailed offers for school principals’ education were implemented (Prøitz, Rye, & Aasen, Citation2019). On that account, the relationship between local autonomy and national control is still characterised by accountability:

Although Norway’s municipalities have a long tradition of local autonomy, they must provide education following the Norwegian Education Act and its related regulations (i.e., the national curriculum, national regulations for assessment and reporting results for monitoring purposes). (Prøitz, Novak, & Mausethagen, Citation2022, p. 92)

An increasingly outcome-oriented education system and a high degree of accountability characterise central reform elements of the last 30 years. The decision-making power in schools lies between the power of the state and their local distributed autonomy, administrated by municipalities. These municipalities again have to work between political and professional decision-making power (Prøitz, Rye, & Aasen, Citation2019). This led to a “complexity of mixed forms of state governing, local autonomy, accountability, and responsibility” (Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2021, p. 9).

In conclusion, school principals partially have the possibility for more autonomy. Still, at the same time, they have to manage the rising duty of documentation of learning outcomes and sharp supervision of their local sphere of action (Møller, Aasen, Rye, & Prøitz, Citation2013). Their scope of action “is narrowed by the municipal use of national standardized tests to hold schools accountable” (Camphuijsen, Møller, & Skedsmo, Citation2021). It has been claimed that central aspects of the Nordic education model, like focus on community and socially inclusive policy, are declining at the cost of facing outcome-oriented education (Blossing, Imsen, & Moos, Citation2014).

Summary

As the review of the literature and the context descriptions show, are school principals in both countries at the forefront in implementing and translating educational reforms. One of these challenges is the realisation of inclusive education. Here, school principals are situated between statutory provisions and uncertain responsibilities. On the one hand, they have to ensure the implementation of this reform, improvement of their school, and its outcomes. On the other hand, their scope of action regarding a school for all is still unclear.

Summarising both countries, it can be said that they have different approaches to an inclusive school setting, framed by different historical educational reform traditions. The German conservative mindset regarding education admittedly led to changes in the system. Still, these changes can be seen more as an attempt to implement new reforms in an established system, causing continuing stability (Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2021). A more progressive mindset in Norway led to many reforming changes but also uncertainty in allocations of responsibilities (Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2021). Nevertheless, both countries face issues with implementing (in Germany) and performing (in Norway) inclusive schooling. The placement of a pupil depending on resources available at one school leads to a questionable location of pupils in Germany. Norway, instead, is toiling with the quality of special needs education realised in local schools.

Material and method

An analysis of comprehensive legal texts from Germany and Norway was conducted to understand the historical context and development of principals and their agenda. These kinds of documents were chosen to identify and understand requirements and expectations of educational leaders as well as the development of principals’ scope of action from a historical-comparative perspective. Principals in both countries must follow the law and justify their decisions based on the Education Act (Møller & Skedsmo, Citation2013). Furthermore, “principals’ work is greatly framed by policy expectations” (Wermke, Nordholm, Andersson, & Kotavuopio-Olsson, Citation2023, p. 7). In Norway, the Ministry of Education and Research initiates national school reforms and leads the school system. Therefore, Education Acts always apply to the whole country, and exceptions are documented in the laws. Just over 90% of students in Norway receiving special education attend regular classes. This figure has remained relatively stable over the past five years (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2022). Due to the complexity of the German federal state system, this study focuses on legislation from Hesse, Bremen, and North Rhine-Westphalia, based on a representation of both rural and urban environments and their percentage of children with special needs education taught in regular schools, seen in comparison to all children with diagnosed special needs education. In the school year 2019/2020, Bremen led the “inclusion ranking” with almost 90% of children with special needs education taught in regular schools, while Hesse was nearly at the other end of the ranking table with 37.7%. North Rhine-Westphalia presents the middle (Klemm, Citation2021). Since not all tasks are unequivocally regulated and formulated in legal acts (Møller & Skedsmo, Citation2013; Stenersen & Prøitz, Citation2022), guidance documents regarding school principalship and inclusive schooling are further included in the analysis. This support material makes school laws more practical-oriented (Hopmann, Citation1999) and depicts rules of procedure and principles focused on inclusion in school settings.

For the Norwegian case, all documents until 1994 were available online, whereas reaching the German Education Act and guiding documents proved difficult. Documents dating back before 2000 were just sparsely or not at all available online. After different approaches and several phone calls, we got access to archive databases of the ministries. However, it is important to mention that these documents are important sources over the given period because these regulations and their guiding documents reveal what principals should do and how this changed historically. In the end, we worked with four Education Acts (one from each of the three federal states in Germany and one from Norway) and their changes from 1994 until 2022 in addition to thirteen guiding documents, which summed up in an empirical material of ca. 2700 pages.

Finally, the analysis was characterised by content document analysis (Bowen, Citation2009) in the further development of Prøitz (Citation2015), combining elements from content analysis with thematic analysis. To filter out the passages about principals’ responsibilities regarding inclusive education, the analysis began with an extended word count in Acrobat Reader (see ).

Table 1. Chosen words for word counts in German and Norwegian documents.

The chosen words resemble each other. The Norwegian term tilpasset opplæring (adapted education), for example, is not used in the German context; instead, Integration is still common. The word count gave an overview of the frequency of using these terms and presented the method for selecting paragraphs. That means those paragraphs using one of these words were marked. In a second step, the Education Acts from 1994 and 2022 and governing documents from their respective year of origin and current issues were used to trace changes back and forth in time.

This work was done in both directions, from 1994 until 2022 and 2022 until 1994, because it could happen that paragraphs just appeared or disappeared. Furthermore, documents between those years were examined to determine if new paragraphs about principals’ responsibility regarding inclusive schooling appeared after 1994 but disappeared before 2022. Following a systematic interpretative reading, these key paragraphs were intercoded by two persons inductively into school principals’ most frequent responsibilities, mentioning the composition of inclusive schooling and their associated accountability rationales, using the data analysis software NVivo. Finally, we sorted all codes with their traced paragraphs in a chronological, neatly arranged chart to begin with in-depth reading. Only sections of the regulations that explicitly stated school principals’ responsibility were included in the analysis. It may be that a principal does not have to do a task alone, can delegate things, or needs to involve other units. Still, as stated in the Education Act and the accompanying documents, the school principal is responsible.

Findings

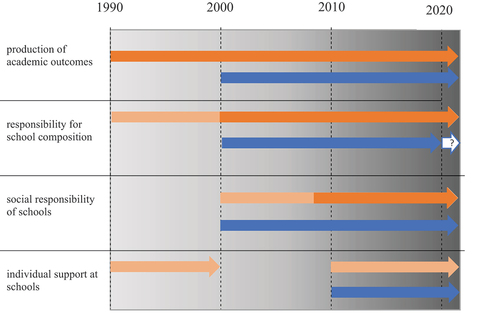

The following categories emerged through inductive category formation: production of academic outcomes, responsibility for school composition, social responsibility of schools, and individual support at schools, and are explained in more detail in the following section.

Production of academic outcomes

Both countries are struggling with satisfying academic outcomes for all children. Continuously, from the 1990s on, school principals in Germany have been responsible for the production of such outcomes, for example, through schools fulfilling the so-called Bildungsauftrag (since 1990s), the evaluation of the whole schoolwork (since 2000s) and the organisation and conducting of lessons (since 2010s). Similar in the three countries is a focus on developing quality and outcomes since the 2000s, with descriptions getting more detailed.

She or he is responsible for the quality development and quality assurance of teaching and has the final right to make decisions in this area (HSchG §63). The school principal is obliged to inform herself/himself about the proper process and the methodological and technical quality of teaching and educational work and has to intervene if necessary. (LDO HE §17)

While responsibilities for producing academic outcomes increased over the years, the scope of action became more restricted. Starting at the beginning of the 2000s, German legislation mentions responsibilities from principals and their decisions regarding academic outcomes by legal and administrative regulation, following directives from school authorities and decisions from the school member assembly (Schulkonferenz) (ADO NRW §17). At the same time, the overall responsibility of school principals is emphasised (see ).

German principals have to focus on quality management by several entities, principals in Norway instead “have an independent responsibility for assessing whether all pupils get satisfactory benefits from teaching” (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2021, p. 40), depicted in . Other than in Germany, it is not common for Norwegian school principals to visit lessons and give feedback about quality of teaching. Nevertheless, when a principal considers that their school cannot fulfil requirements for special needs education and provide satisfying outcomes to all pupils, it is their responsibility to start a reassessing process and ask for more resources, for example, economic support from the municipality (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2021).

Responsibility for school composition

To a variable extent, school principals in Germany decide on admission to school. In the federal states of Hesse and Nord Rhine-Westphalia, school principals decide if children applying under six years (school enrolment age) already have the mental and physical age for visiting school. The other way around, if children do not yet have the required level of physical, mental, or emotional development, parents are heard, and based on the recommendation of a school’s psychological or doctoral service, school principals are, regarding the law, responsible for deferring children for one year. Furthermore, decisions on special tuition before school starts lies within principals (HSchG §58; SchulG NRW §35). The Bremen law instead states that “the school” is responsible for school admission (BremSchulG §53), while the regulation for school principals mentions that it lies within principals’ responsibility since 2005 (LehrDiV BR §22). Regarding an inclusive environment, a restriction on the schools’ autonomy has been mentioned since 1994:

The schools organize their internal affairs within the framework of laws, legal ordinances, administrative regulations, and decisions of the school authorities. Insofar as the Senator for Education and Science is authorized by law to issue legal ordinances in the area of schooling, these may only restrict the independence of the school to a necessary extent to promote and ensure equality in education and equal opportunities for students. (BremSchVwG §22)

This paragraph has furthermore restricting influence on school principals’ scope of action (see ).

In contrast to the responsibility of possibly excluding pupils from school stands the responsibility from Norwegian principals. While German principals “design” school environments by approving children to school, Norwegian principals have to accept all children but are later on responsible for keeping school environments best for everyone. Extensive changes were implemented in Citation2002, with a new paragraph diligently taking care of pupils’ school environment. Schools are supposed to have zero tolerance for harassment in the event of bullying, abuse, and discrimination. In the year of the implementation of this paragraph, school principals had a special responsibility for systematic work and intern control:

The school must actively conduct continuous and systematic work to promote pupils’ health, environment, and safety to fulfill the requirements in or in connection with this chapter. The school principal is responsible for the day-to-day implementation. (Opplæringslova §9A, Citation2002)

In Citation2017, the formulation changed slightly, but school principals were still responsible. This part of the paragraph changed again in Citation2020, reading now:

Everyone who works at the school must monitor whether pupils have a safe and good school environment and intervene against violations such as bullying, violence, discrimination, and harassment if possible. Everyone who works at the school must notify the principal if they suspect or become aware that a pupil does not have a safe and good school environment. In serious cases, the principal must notify the school owner. (Opplæringslova §9A, Citation2020)

The explicit mention of school principals’ responsibility disappeared. Instead, the requirement for schools to follow a written plan was added, which serves as a supervisory body for giving an account of what has been done. In contradiction to the disappearance of principals’ responsibility in the law, the document “Requirements and expectations to school principals” published by the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training is still emphasising responsibilities in Citation2020: “The school principal is responsible for pupils’ learning results and the school environment and for facilitating good learning processes at the school” (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2020). Since 2006, these results have been assessed and tracked nationally (see ).

Social responsibility of schools

Since the 2000s, both countries have set focus on social responsibilities of schools and the responsibility of school principals accompanied by this. In all three examined German federal states, school principals are responsible for schools, especially for the school fulfilling its schooling mandate. Hesse has to be mentioned here as a special case. Principals in this federal state always have to object to resolutions from the school member assembly violating legal provisions. Since 2010, the assembly also has to reconsider and possibly make a new decision if the school principal has significant concerns for pedagogical reasons (HSchG §87).

Norwegian principals are also responsible for schools fulfilling their social responsibility. This has been explicitly mentioned since the 2000s. However, fulfilling this task contains principals acting on behalf of central and local authorities since 2020, depicted in (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2020). The document about requirements to school principals states another comprehensive area of social responsibility, namely the responsibility from schools accommodating to changes in society:

The principal is responsible for developing and changing the organization in line with internal and external changes to always adapt to its tasks and context. […] The principal is responsible for the school capturing societal changes, the basis of students, legal guardians, technology and politics, and subjects that may be important to the school’s mission and activities. Therefore, the school principal’s ability for strategic management, development, change processes, and competence development management is crucial. (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2020)

At the same time, it is mentioned that expectations and requirements are high and that no single person can fulfil this in all areas of responsibilities on the same qualitative level; school principals are seen as ideal persons in this document. However, it is mentioned again that school principals’ responsibility is technically all-embracing (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2020).

Individual support at schools

One document from North Rhine-Westphalia from the 1990s stated that school principals decide on the organisation of support courses for German language for students and which pupils are allowed to join this course in case of requests from legal guardians or teachers (LRS NRW). Since the 2010s and revisions from the first school law, principals are responsible for decisions on support measures. However, this is just stated in general terms and not described further. Principals’ responsibility for individual support in schools is regulated in more detail in Hesse:

Suppose there is a right to special needs education considering one child’s previous educational history at the time of registration to school, and no immediate admission to special needs education at the school. In that case, the principal will decide within paragraphs 2 to 4 after hearing the parents and in consultation with the school authority about special educational needs’ type, scope, and organization. (HSchG §54)

In addition, a so-called committee for special needs education is initiated, advising on this decision. If the committee cannot agree on one decision, the school authority finally decides, in consultation with the principal (see ).

Norwegian principals have an area of responsibility for individual support at schools, too. Since 2010, “the principal is responsible for facilitating good planning work and has to ensure that the drawn up individual education plans are within requirements of the law” (Opplæringslova §5). Another task is mentioned in the guiding document for special needs education. While law states that teachers must purchase special needs education requisition to principals, without further indication for school principals (Opplæringslova §5), the guiding document is more specific. Principals are directly obliged to initiate a necessary investigation if one child has the right to special needs education. They are not allowed to reject this request (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2021).

Sanction and penalty

One aspect not presented in the chart but still important is the part about sanctions and penalties. There is no penalty for German school principals mentioned in school legislation since they are civil servants. The state of North Rhine-Westphalia mentions since 2010 that, teachers can appeal to the school authority in case of a complaint. It does not list what is happening further (ADO NRW §11).

Entirely different is the Norwegian case. In Citation2002, the implementation year of the new paragraph regarding pupils’ school environment, a penalty was implemented. If requirements mentioned in the paragraph or accorded regulations were intentionally or negligently violated, fines, imprisonment for up to three months or both can be expected. Even complicity is punished similarly (Opplæringslova §9A, Citation2002). Since 2017, this penalty has been, among others, explicitly sent to school principals. It is called the 9A case (after the paragraph number).

The principal is punished for intentionally, negligently, seriously, or repeatedly violating the law according to §9A–4 third and fourth paragraphs with fines, imprisonment for up to three months, or both. (Opplæringslova §9A, Citation2017)

More detailed control and intervention from the county governor have been further regulated since 2010. If a 9A case was registered with the school principal one week ago, but the child still does not perceive a good school environment, legal guardians, or the child itself can refer to the county governor, who controls the proceeding. In case of missing or incorrect action, the county governor defines and controls actions and sets deadlines (see ) (Opplæringslova §9A, Citation2023).

Summary

The established categories are related to the Declaration of Salamanca of 1994, its School for All, and the principals’ responsibility that producing academic outcomes is associated with leadership regarding satisfying academic outcomes for all children. The responsibility for school composition instead points out principals’ tasks in admitting children to school, while the category social responsibility of schools focuses on responsibilities concerning well-being. Lastly, individual support at schools explains the responsibility of school principals when it comes to any assistance for single pupils.

Since all these categories were evaluated from 1994 until 2022, the historical shift in school principals’ responsibilities can be summed up as seen in . Since accountability is not explicitly mentioned as such and appears gradually, it is marked with a grey background. It simply becomes stronger during the time of investigation.

Figure 1. depiction of principals’ responsibilities manifested in regulations in Germany (orange; lighter orange points to just one of the three federal states) and Norway (blue) and depiction of accountability becoming stronger (grey background getting darker)

It is important to remember that these results focus solely on developing a School for All and, therefore, cut off many other responsibilities from school principals. For example, principals in both countries are responsible for teachers. In all three German states, principals are teachers’ superiors, have to work on target agreements with them, and are responsible that teachers fulfil their duty for further education (BremSchVwG §63; HSchG §88). Since 2020, Norwegian principals have been responsible for the competencies of staff at schools (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2020). However, their explicit responsibility regarding teachers is not mentioned in the law. These tasks can lead to inclusion because teachers are responsible for the lessons and their quality. Since this research has chosen the Declaration of Salamanca as its starting point of examination and its goal of a School for All, these results are just a selection of the findings. Furthermore, it has to be mentioned that Norwegian school principals certainly have more tasks regarding inclusive schooling than mentioned here. One guiding document for special needs education states that

The school owner can delegate their authority to the principal. We assume in this guiding document that the authority is delegated from the school owner to the school to the principal and therefore have chosen to write ‘the school’ when we mention who makes individual decisions. (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2021, p. 9)

However, the overall responsibility remains with the municipality as the school owner (Schulträger).

Discussion

Summarising the results presented in , it can be said that German principals have a more stable area of responsibility seen over the years. If a task or responsibility for school principals was implemented, it is not taken away anymore but adapted and described in more detail. North Rhine-Westphalia is the only federal state investigated here that took some responsibility away. The chart furthermore shows that Norwegian principals got more responsibility over the years.

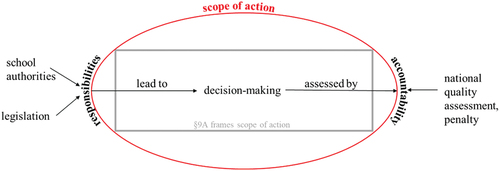

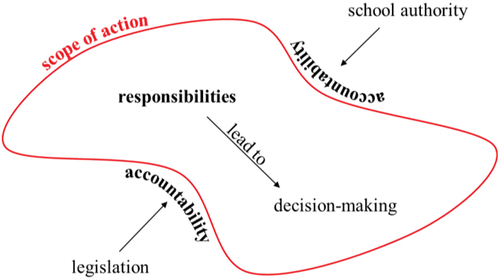

Seen in direct comparison, school principals from Norway have fewer areas of responsibility than German principals, but usually, the sole responsibility, which can be seen in terms like “independent responsibility” or “overall responsibility” (see ). Accountability is not mentioned explicitly in the legislation but is nevertheless present through monitoring results and pressure through penalties regarding the school environment. German principals instead have more extensive areas of responsibility but are usually not autonomous in their decision-making. They have a closely defined room for manoeuvre, demarcated by regulations from school authorities, school doctors, and the school member assembly, and decisions have to be made “in consultation with” either the assembly, school authorities, or other entities (see ). Other than in Norway, where accountability is more located at the end of decision-making processes, German accountability is placed at the beginning and throughout the decision-making process through narrow room for manoeuvre and the school member assembly as supervisory body. However, Norwegian school principals’ scope of action is further framed by the paragraph regarding the school environment of pupils (Opplæringslova §9A) and its strict guidelines. We have depicted the Norwegian case in and the German case in .

Figure 2. Relation school principals’ scope of action – responsibilities – accountabilities in Norway

Figure 3. Relation school principals’ scope of action – responsibilities – accountabilities in Germany

Even though some areas of responsibility are explicitly directed to school principals in both countries, they often undertake chores from school authorities with overlapping areas and no clear boundaries. School principals have to fulfil tasks without responsibility or real decision-making power. Following Kuper’s argument, they have no “premise for decisions” (Kuper, Citation2020).

To explain this premise in more detail and show the difference between Germany and Norway, we must look closely at Luhmann (Citation2020). He states that premises for decisions show how an organisation creates conditions for its decisions through overarching decision-making, giving three opportunities. One of the options is to decide on communication paths on which transactions are dealt with. Another one is deciding on programmes that are decisive for further decisions. In all explored federal states of Germany, schools can and have to set their school programme, which might look like they can influence further decision-making regarding their plan (for example, the plan would be an inclusive school). However, school programmes have to be created according to school authorities, so it can be questioned if the premise for decision-making lies within the school. The final alternative Luhmann (Citation2020) mentioned is the premise for decisions through personnel decisions, the assignment of tasks, and competence expectations. This is present in the Norwegian law. Even though school authorities take part in this through the assignment of tasks, school principals have to arrange the competencies needed and being available at schools since 2020. This shows that in various ways, school principals in both countries must work operatively, conduct tasks, and fulfil their responsibilities. At the same time, they also have to work strategically and transform government strategies and requirements from school authorities into practice.

In essence, Germany and Norway have the same requirements but, as has been shown, work with different approaches. In both countries, state governments make the decisions on premises, and school principals are to implement policies regarding premises in their schools, together with and upon their teaching staff. Implementation can be connoted with more or sometimes less responsibility and accountability. Both aspects are complementary. The German school as an organisation gained more decision-making power over the years, while school principals also got more areas of responsibility concomitant with a more restricted room for manoeuvre due to several accountability expectations. Norwegian school principals have fewer areas of responsibility but, therefore, often sole responsibility with a wider room for manoeuvre than in Germany. Besides that, it is emphasised that no single human being can fulfil all the requirements set by school principals and that everybody should focus on their strengths. Norwegian principals’ accountability is present through outcome control as long as all rules are followed, and all children have a satisfying school milieu. Otherwise, penalties can be expected. German principals are usually controlled throughout their work with the help of school contracts, target agreements, and school member assemblies. In this context, sanctions are not mentioned in the legislation.

These different approaches can be explained with Esping-Andersen’s typology of the three welfare states (Citation1990): Germany as a conservative state with more segmentation, a performance-based “equality” and a status that results from the position on the labour market, Norway as a socio-democratic state with equality, inclusion, and equality of performance as values of reference (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990). This impacts school systems and the view on and execution of responsibility and accountability. Hopmann (Citation2008) explains this with the so-called “constitutional mindsets”. “No State Left Behind” is the game’s name in Germany. The school systems from different federal states are momentously shaped by bottom-up governance and control. Norway, instead, is focusing on leaving no school behind. Even though governance is national, local autonomy and responsibility are emphasised with high reliance on school professionals.

Conclusion

Concluding the implementation of the Declaration of Salamanca and its manifestation in regulations, it can be summarised that both countries started with responsibilities for school principals, increasing over time. Later on, accountabilities were added to secure and trace the implementation of inclusive education. Based on the Education Acts and their guiding documents, it can be determined that German principals’ work is more shaped by accountability than Norwegian principals’ work, and that German regulation presents stricter requirements. This may be due to the fact that Germany, characterised by 16 federal states with different education systems and a sophisticated special education system, has difficulties in implementing inclusive education. This means that more and more areas of responsibility are being transferred to school principals. However, due to international pressure to successfully implement inclusive education, the work of school principals is perceived as something that must be monitored on an ongoing basis. In contrast, Norwegian society is already based on the principle of equality, important for inclusive education. Nevertheless, a controlling authority has also been introduced here (Norway’s principals can expect personal punishments and outcome control), which is much stricter than in Germany, but only applies to certain aspects, namely a satisfactory school environment. It can therefore be said that school principals in both countries work responsibly to implement inclusive education. In doing so, school principals do have a certain scope of action, which, depending on the context, is sometimes more, sometimes less limited. In Germany, there are large areas of responsibility for school principals, although decisions are ultimately not made autonomously and are strongly framed by law. In addition, school authorities have a strong controlling role. In Norway, there are clearly defined areas of responsibility with a wide scope of action, which is ultimately framed by a possible punishment. In addition, school principals in both countries must take chores from school authorities with no clear boundaries and therefore no real decision-making power. Whether more precisely defined areas of responsibility or a clearly defined scope of action with less framing will help against this “hanging in the air” or if school principals will then ultimately take sole responsibility for the implementation of inclusive education must be investigated in practice.

However, overcoming the assumption that accountability and control are negative is important. It is essential to consider the complexity of these aspects and the context in which actions are embedded (Cribb & Gewirtz, Citation2007). Furthermore, there is a difference between policy implementation and its enactment. Responsibility and accountability are perceived differently by school principals. It can be seen as a burden or freedom of legal arrangement.

Geolocation information

Paper’s study area: Germany and Norway

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carolina Dahle

Carolina Dahle is a PhD fellow at the University of South-Eastern Norway, Department of Educational Science. Her research interests lie in the field of inclusive education policy and practice and their relationship seen from a comparative perspective.

Wieland Wermke

Wieland Wermke is professor of Special Education at Stockholm University, Department of Special Education. His research focuses on the relation of education professionalism and education policy from an international and comparative perspective.

Notes

1. This and all subsequent translations into English have been done by the authors.

References

- Aasen, P., Møller, J., Rye, E., Ottesen, E., Prøitz, T. S., & Hertzberg, F. (2012). Kunnskapsløftet som styringsreform - et løft eller et løfte? Forvaltningsnivåenes og institusjonenes rolle i implementeringen av reformen. NIFU report 20/2012. Retrieved from https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/tall-og-forskning/rapporter/2012/fire_slutt.pdf

- Abrahamsen, H. N., & Aas, M. (2019). Mellomleder i skolen. Bergen: Fagbokforlag.

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. doi:10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

- Amrhein, B. (2011). Inklusion in der Sekundarstufe. Eine empirische Analyse. Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt.

- Badstieber, B. (2021). Inklusion als Transformation?! Eine empirische Analyse der Rekontextualisierungsstrategien von Schulleitenden im Kontext schulischer Inklusion. Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt.

- Badstieber, B., & Amrhein, B. (2021). Handlungspraktiken von Schulleitenden im Kontext integrations-/inklusionsorientierter Schulentwicklungsprozesse – empirische Befunde aus der Schweiz und Deutschland. In A. Köpfer, J. J. W. Powell, & R. Zahnd (Eds.), Handbuch Inklusion International. Globale, nationale und lokale Perspektiven auf Inklusive Bildung (pp. 383–406). Opladen, Berlin, Toronto: Barbara Budrich.

- Bailey, J., & du Plessis, D. (1997). Understanding principals’ attitudes towards inclusive schooling. Journal of Educational Administration, 35(5), 428–438. doi:10.1108/09578239710184574

- Blossfeld, H.-P., Bos, W., Daniel, H.-D., Hannover, B., Lenzen, D., Prenzel, M., & Wößmann, L. (2010). Bildungsautonomie: Zwischen Regulierung und Eigenverantwortung - die Bundesländer im Vergleich Expertenrating der Schul- und Hochschulgesetze der Länder zum Jahresgutachten 2010. München: vbw.

- Blossing, U., Imsen, G., & Moos, L. (2014). Schools for all: A nordic model. In U. Blossing, G. Imsen, & L. Moos (Eds.), The Nordic education model: “A school for all” encounters neo-liberal policy (pp. 231–239). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7125-3_13

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. doi:10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Brauckmann, S., Schwarz, A., Brauckmann, S., & Felici, P. (2015). No time to manage? The trade-off between relevant tasks and actual priorities of school leaders in Germany. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(6), 749–765. doi:10.1108/IJEM-10-2014-0138

- Camphuijsen, M. K., Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2021). Test-based accountability in the Norwegian context: Exploring drivers, expectations and strategies. Journal of Education Policy, 36(5), 624–642. doi:10.1080/02680939.2020.1739337

- Cribb, A., & Gewirtz, S. (2007). Unpacking autonomy and control in education: Some conceptual and normative groundwork for a comparative analysis. European Educational Research Journal, 6(3), 203–213. doi:10.2304/eerj.2007.6.3.203

- Döbert, H. (2015). Germany. In W. Hörner, H. Döbert, L. R. Reuter, & B. von Kopp (Eds.), The education systems of Europe (pp. 305–333). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-07473-3_19

- Engeland, Ø., & Langfeldt, G. (2009). Forholdet mellom stat og kommune i styring av norsk utdanningspolitikk 1970 - 2008. Acta Didactica Norge, 3(1), article 9. doi:10.5617/adno.1037

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Grissom, J. A., Blissett, R. S. L., & Mitani, H. (2018). Evaluating school principals: Supervisor ratings of principal practice and principal job performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(3), 446–472. doi:10.3102/0162373718783883

- Hanssen, K. (2013). Rechtliche Regelungen zu Tätigkeitsfeldern von Schulleiterinnen und Schulleitern bei erweiterter Eigenverantwortung von Schulen. Eine Untersuchung der Rechtslage in den Ländern Berlin und Niedersachen (Ergänzung zu der Untersuchung der Rechtslage in den Ländern Bayern, Hessen und Nordrhein-Westfalen sowie in den Ländern Brandenburg und Hamburg). Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsforschung und Bildungsinformation. Retrieved from https://www.dipf.de/de/forschung/pdf-forschung/steubis/projekt-sharp-pdf/Endfassung_BE_NI.pdf

- Heinrich, M. (2006). Autonomie und Schulautonomie: Die vergessenen ideengeschichtlichen Quellen der Autonomiedebatte der 1990er Jahre. Münster: Monsenstein und Vannerdat.

- Hopmann, S. T. (1999). The curriculum as a standard of public education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 18(1–2), 89–106. doi:10.1023/A:1005139405296

- Hopmann, S. T. (2008). No child, no school, no state left behind: Schooling in the age of accountability. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 40(4), 417–456. doi:10.1080/00220270801989818

- Hoppey, D., & McLeskey, J. (2013). A case study of principal leadership in an effective inclusive school. The Journal of Special Education, 46(4), 245–256. doi:10.1177/0022466910390507

- Klemm, K. (2021, June 15th). Zum aktuellen stand der inklusion in Deutschland schulen. Friedrichs Bildungsblog – Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Retrieved from https://www.fes.de/themenportal-bildung-arbeit-digitalisierung/bildung/artikelseite-bildungsblog/zum-aktuellen-stand-der-inklusion-in-deutschlands-schulen

- Knapp, M. (2020). Between legal requirements and local traditions in school improvement reform in Austria: School leaders as gap managers. European Journal of Education, 55(2), 169–182. doi:10.1111/ejed.12390

- Knudsmoen, H., Mausethagen, S., & Dalland, C. (2022). Ledelsesstrategier for utvikling av inkluderende undervisning. Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk, 8, 189–203. doi:10.23865/ntpk.v8.3435

- Knutsen, B., & Emstad, A. B. (2021). Ledelse for en inkluderende skole - også for elever med stort læringspotensial. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Kugelmass, J., & Ainscow, M. (2004). Leadership for inclusion: A comparison of international practices. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4(3), 133–141. doi:10.1111/j.1471-3802.2004.00028.x

- Kultusministerkonferenz. (2011). Inklusive Bildung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Behinderungen in Schulen. Beschluss der Kultusministerkonferenz vom 20.10.2011. https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2011/2011_10_20-Inklusive-Bildung.pdf

- Kuper, H. (2020). Zum Verhältnis von Schulaufsicht und Schulleitung - Organisationstheoretische Perspektive. In E. D. Klein & N. Bremm (Eds.), Unterstützung - Kooperation - Kontrolle: Zum Verhältnis von Schulaufsicht und Schulleitung in der Schulentwicklung (pp. 85–105). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-28177-9_5

- Luhmann, N. (2020). Organisation und Entscheidung. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi:10.1007/978-3-322-97093-0

- Meld. St. 6. (2019-2020). Early intervention and inclusive education in kindergartens, schools and out-of-school-hours care. Ministry of Education and Research. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/meld.-st.-6-20192020/id2677025/

- Mintrop, R., Brauckmann, S., & Felici, P. (2015). Public management reform without managers: The case of German public schools. International Journal of Educational Management, 29(6), 790–795. doi:10.1108/IJEM-06-2015-0082

- Møller, J., Aasen, P., Rye, E., & Prøitz, T. S. (2013). Kunnskapsløftet som styringsreform. In B. Karseth, J. Møller, & P. Aasen (Eds.), Reformtakter: Om fornyelse og stabilitet i grunnopplæringen (pp. 23–41). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2013). Modernising education: New public management reform in the Norwegian education system. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 45(4), 336–353. doi:10.1080/00220620.2013.822353

- Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Paulsen, J. M. (2016). Nordic superintendents: agents in a broken chain. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25106-6

- Opplæringslova §9A, 2002 Opplæringslova. (2002). Lov om grunnskolen og den vidaregåande opplæringa (LOV-2002-12-20-112). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/LTI/lov/2002-12-20-112

- Opplæringslova §9A, 2017 Opplæringslova. (2017). Lov om grunnskolen og den vidaregåande opplæringa (LOV-2017-06-09-38). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/LTI/lov/2017-06-09-38

- Opplæringslova §9A, 2020 Opplæringslova. (2020). Lov om grunnskolen og den vidaregåande opplæringa (LOV-2020-06-19-89). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/LTI/lov/2020-06-19-89

- Opplæringslova §9A, 2023 Opplæringslova. (2023). Lov om grunnskolen og den vidaregåande opplæringa (LOV-1998-07-17-61). Lovdata. https://lovdata.no/lov/1998-07-17-61

- Prøitz, T. S. (2015). Learning outcomes as a key concept in policy documents throughout policy changes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(3), 275–296. doi:10.1080/00313831.2014.904418

- Prøitz, T. S., Novak, J., & Mausethagen, S. (2022). Representations of student performance data in local education policy. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 34(1), 89–111. doi:10.1007/s11092-022-09379-x

- Prøitz, T. S., Rye, E., & Aasen, P. (2019). Nasjonal styring og lokal praksis - skoleledere og lærere som endringsagenter. In R. Jensen, B. Karseth, & E. Ottesen (Eds.), Styring og ledelse i grunnopplæringen: Spenninger og dynamiker (pp. 21–38). Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Rorrer, A. K., Skrla, L., & Scheurich, J. J. (2008). Districts as institutional actors in educational reform. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(3), 307–357. doi:10.1177/0013161X08318962

- Rürup, M. (2007). Innovationswege im deutschen Bildungssystem. Die Verbreitung der Idee “Schulautonomie” im Ländervergleich. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-90735-2

- Rürup, M. (2019). Schulautonomie in Deutschland – ein Dauerthema der Schulreform. In E. R. In, C. Wiesner, D. Paasch, & P. Heißenberger (Eds.), Schulautonomie – Perspektiven in Europa. Befunde aus dem EU-Projekt INNOVITAS (pp. 61–75). Münster: Waxmann.

- Scheer, D. (2020). Schulleitung und Inklusion. In Empirische Untersuchung zur Schulleitungsrolle im Kontext schulischer Inklusion. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-27401-6

- Sekretariat der Ständigen Konferenz der Kultusminister der Länder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. (2021). Das Bildungswesen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2018/2019. Darstellung der Kompetenzen, Strukturen und bildungspolitischen Entwicklungen für den Informationsaustausch in Europa. Retrieved from https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/pdf/Eurydice/Bildungswesen-dt-pdfs/dossier_de_ebook.pdf

- Stenersen, C. R., & Prøitz, T. S. (2022). Just a buzzword? The use of concepts and ideas in educational governance. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(2), 193–207. doi:10.1080/00313831.2020.1788153

- Thiel, C. (2019). Lehrerhandeln zwischen Neuer Steuerung und Fallarbeit. In Professionstheoretische und empirische Analysen zu einem umstrittenen Verhältnis. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-23160-6

- UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. Salamanca: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2020). Krav Og forventninger til en rektor. Retrieved from https://www.udir.no/kvalitet-og-kompetanse/etter-og-videreutdanning/rektor/krav-og-forventninger-til-en-rektor/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2021). Veilederen Spesialundervisning. Retrieved from https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/spesialpedagogikk/spesialundervisning/Spesialundervisning/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2022). Utdanningsspeilet 2022. Retrieved from https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/publikasjoner/utdanningsspeilet/utdanningsspeilet-2022/grunnskolen/spesialundervisning-i-grunnskolen/

- Wermke, W., & Forsberg, E. (2023). Understanding education reform policy trajectories by analytical sequencing. In T. S. Prøitz, P. Aasen, & W. Wermke (Eds.), From Education Policy to Education Practice. Unpacking the Nexus (pp. 59–73). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-36970-4_4

- Wermke, W., Freier, R., & Nordholm, D. (2023). Framing curriculum making: Bureaucracy and couplings in school administration. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 55(5), 562–579. doi:10.1080/00220272.2023.2251543

- Wermke, W., Jarl, M., Prøitz, T. S., & Nordholm, D. (2022). Comparing principal autonomy in time and space: Modelling school leaders’ decision making and control. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 54(6), 733–750. doi:10.1080/00220272.2022.2127124

- Wermke, W., Nordholm, D., Andersson, A., & Kotavuopio-Olsson, R. (2023). Deconstructing autonomy: The case of principals in the North of Europe. European Education Research Journal. doi:10.1177/14749041221138626

- Wermke, W., & Prøitz, T. S. (2021). Integration, fragmentation and complexity - governing of the teaching profession and the nordic model. In J. E. Larsen, B. Schulte, & F. W. Thue (Eds.), Schoolteachers and the Nordic model: Comparative and historical perspectives (pp. 216–229). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003082514-17

- Wissenschaftlicher Dienst des deutschen Bundestages. (2020). Schulautonomie in den Landesgesetzen. Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

- Wissinger, J. (2011). Schulleitung und Schulleitungshandeln. In E. Terhart, H. Bennewitz, & M. Rothland (Eds.), Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf (pp. 98–115). Münster: Waxmann.

- Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., Förster, M., & Preuße, D. (2012). Implementierung und Wirksamkeit der erweiterten Autonomie im öffentlichen Schulwesen - eine Mehrebenenbetrachtung. In A. Wacker, U. Maier, & J. Wissinger (Eds.), Schul- und Unterrichtsreform durch ergebnisorientierte Steuerung. Empirische Befunde und forschungsmethodische Implikationen (pp. 79–107). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-94183-7_4