ABSTRACT

During recent years, many European education systems have attempted to modernise their governance by establishing some variety of an ‘evidence-based governance regime’. Since 2008, a policy of performance standards has been introduced in Austrian education. This policy includes the communication of competence-based output standards, the provision of support material (e.g. competence-based assignments, diagnostic tests) and in-service training opportunities, nationwide comparative competence tests (at the end of the primary and lower secondary cycle of schooling), and data feedback of assessments results to students, teachers, schools, and administrative authorities.

The paper aims to develop a conceptual model for research into the processes and effects of such a ‘performance standard policy’. Official documents are analysed in order to formulate the ‘programme theory’ underpinning the policy. Main elements of this policy, its intended effects, and the processes and intermediary mechanisms are outlined in a conceptual model that may be used to organise and orchestrate research into performance standard policies.

Introduction

During recent years, many European nations have attempted to modernise the governance of their education systems. In Austria – and, very similarly, in the education systems of the German Bundesländer (Rürup, Citation2007) – the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) shock of 2001 and the political and media debate in its wake provided the essential impulse for governments to initiate changes and thereby show leadership in a context of proclaimed crisis (see Tillmann, Dedering, Kneuper, Kuhlmann, & Nessel, Citation2008). The major model for modernisation was so-called ‘evidence-based governance’.Footnote1 This model is meant to regulate operation of the system and its continuous improvement by virtue of the following features (see Altrichter & Maag Merki, Citation2016):

The governance model sets expectations for the performance of the education system and communicates them more clearly than before.

Evaluation and accountability are considered to be key issues in ensuring quality provision for all. Evaluation measures are to produce evidence as to whether expectations have been met via practical operation of the system units.

‘Evidence’ is fed back through reports and mechanisms of data feedback that are meant to stimulate and orientate system development.

These governance models try to include stakeholders more actively than before, by asking their opinion (e.g. in inspection visits), by actively communicating quality standards and performance results to them, and by encouraging them to react to the ‘comparative performance’ of individual schools by raising their ‘voice’ in the individual schools or by exercising ‘choice’ regarding good schools.

Finally, these models are usually built on a concept of multi-level system structure. Actors on all levels of the system – education politicians, administrators, school leaders, teachers, students etc. – are included and provided with evaluation information. It is assumed that they will use the information to make more reflective and rational choices in developing and improving their performance.

There are several instruments that may be used to build up a national system of evidence-based education governance. The actual configuration of system elements varies widely between countries (see e.g. Ehren, Altrichter, McNamara, & O’Hara, Citation2013); however, there are two dominant arrangements in Europe (which often exist side by side): school inspections on one hand and performance standards and comparative testing on the other.

School inspections are clearly a typical incarnation of the evidence-based governance philosophy: they set normative expectations through their processes of inspecting and through their quality standards and criteria. They collect and analyse data that is already available through comparative assessments or evaluations, or that has been freshly acquired through school visits, interviews with stakeholders and/or classroom observation. They use this information to develop inspection reports that evaluate the school’s performance against inspection criteria and include some (explicit or implicit, depending on different national systems) recommendations for classroom and school improvement (Altrichter & Kemethofer, Citation2016).

Performance standard policies are another practical embodiment of evidence-based governance in education. They usually include the following elements. They set normative expectations by formulating performance standards for specific competences or subjects and age groups. These standards are tested by nationwide comparative student assessments, and the results are fed back to various operative and administrative actors on all levels of the school system, but also to parents, and, in some countries, to the public and the media (Maag Merki, Citation2016).

In this paper, a specific national example for performance standard policies taken from Austria will be analysed in more detail. Performance standards were introduced into the Austrian education system in 2008 through an amendment to the School Instruction Law (SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008), after expert commissions had been calling for such measures for some time (e.g. Haider, Eder, Specht, & Spiel, Citation2003; Specht, Citation2006). In its central concepts and strategy elements, the Austrian legislation was influenced by the German expert opinion by Klieme et al. (Citation2003) and by an expert commission appointed by the Austrian education minister (Zukunftskommission; see Haider et al., Citation2003; Haider, Eder, Specht, Spiel, & Wimmer, Citation2005). The policy includes, in short, the following features: performance standards for the primary cycle of schooling (students of 10 years) in maths and German (native language) and for the lower secondary cycle (students of 14 years) in maths, German and English (main foreign language) have been formulated. Classroom material, diagnostic tests and sample test items were offered alongside other publications and workshops in order to support full implementation of the new ‘standards’ and competence-based teaching in classrooms. After a pilot phase of provisional implementation, nationwide comparative standard testing for secondary students was administered for the first time in May 2012, and performance results were fed back to students/parents, teachers, school leaders and administrators. In 2013, the first round of national standard testing took place for primary schools.

Since the start of the pilot phase, different aspects of performance standard implementation have been examined via questionnaires administered to teachers and headpersons (see Amtmann, Grillitsch, & Petrovic, 2011; Dinges & Egger, Citation2015; Freudenthaler & Specht, Citation2005, Citation2006; Grabensberger, Freudenthaler, & Specht, Citation2008; Grillitsch, Citation2010; Grillitsch & Amtmann, Citation2012; Rieß & Zuber, Citation2014). The overall findings have been inconclusive with respect to the intended impact (for a synthesis, see Altrichter, Moosbrugger, & Zuber, Citation2016; Maag Merki, Citation2016) – similarly to much research on new governance instruments (see e.g. the synthesis on inspection research by Husfeldt, Citation2011). An explanation (e.g. suggested by Husfeldt, Citation2011, p. 10) is that research has used overly simple models that:

have been based on a global, undifferentiated image of the reform strategy (ignoring its possibly more complex internal structure consisting of effective, non-effective, and detrimental elements), and

has not included information on the internal processes and effective mechanisms that were meant to lead to the goals.

Improvement of this situation is the main purpose of this paper. It aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the processes and effects of newgovernance strategies by formulating a conceptual model elaborating the assumptions underpinning this policy (Ehren et al., Citation2013; Jones & Tymms, Citation2014); in particular, explaining the pathways that are thought to mediate between policy interventions and expected outcomes (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011a, p. 175) is useful. Such a model is intended to provide a rationale for deciding which elements of the policy and its implementation have to be attended to both by research and evaluation on one hand, and by policy formulation and implementation on the other.

Such a conceptual model (see Ehren, Leeuw, & Scheerens, Citation2005, Citation2013; Leeuw, Citation2003; similarly: Resnick, Besterfield-Sacre, Mehalik, Sherer, & Halverson, Citation2007) reconstructs

by what intermediary processes (or coordination mechanisms; Balog & Cyba, Citation2004)

specific elements of a policy are linked to

expected results or effects (usually formulated as reform goals).

Such a conceptual model may be

normative if it reconstructs the expectations and assertions for impact that underpin the proponents’ versions of a reform (see e.g. Ehren et al., Citation2013), or it may be

empirical if expectations of impact have been tested and the model’s elements, coordination mechanisms, and goals/results have been reformulated to reflect empirical findings (see e.g. Gustafsson et al., Citation2015).

Such conceptual models have proved useful, e.g. for research in data use (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011b) and in inspections (Ehren et al., Citation2013; Gustafsson, Lander, & Myrberg, Citation2014; Jones & Tymms, Citation2014). However, these models conceptualise different policies (inspections) or only parts of the processes (data use) that are relevant in ‘performance standard policies’. Thus, this paper aims to propose a conceptual model for a performance standard policy. In the following paragraphs, we will focus on the specific case of the Austrian performance standard policy. Of course, the long-term goal is to identify more general mechanisms of performance standard policies that may also be relevant for other national contexts. However, generalisation cannot be achieved before understanding national specificities. Although we see a range of ‘travelling policies’ when it comes to reforming education systems, the embedding of supposedly similar policies into different national contexts may lead to a broad variation of results (Ozga & Jones, Citation2006).

Austrian education is usually considered a centralist-bureaucratic governance system (Windzio, Sackmann, & Martens, Citation2005) with comparatively little autonomy for individual schools, but more room for manoeuvre for individual teachers. Since the middle of the 1990s, the system has been modernised by introducing some elements of a new ‘evidence-based governance policy’ (such as more school autonomy, performance standards, etc.; see Altrichter & Soukup-Altrichter, Citation2008).

In this paper, we aim to reconstruct the normative conceptual model underpinning the Austrian performance standard policy; we will do this by discussing the following research questions:

What impact does the Austrian performance standard policy aim to have on schools?

What are the elements and mechanisms by which this impact is intended to be achieved?

The major purpose of such a reconstruction lies in the possibility of validating the claims included in the policy. This will be done via an empirical study (not reported in this paper). In the next but one section we will explain the research strategy and the methods applied. Before doing so, theoretical ideas and existing conceptual models for conceptualising innovation of educational governance will be examined.

Innovating governance systems

Introducing a new evidence-based governance strategy such as a performance standard policy aspires to change the regulation of an education system. How should systemic innovation be conceptualised? We use three theoretical leads for developing our conceptual model.

Actors making sense of ‘structural offers’: Based on the ‘governance’ concept proposed by actor-centred institutionalism (Altrichter, Citation2010; Mayntz, Citation2009; Schimank, Citation2007), innovatory ideas and instruments are inserted as ‘structural offers’ in an interactional and discursive arena with a multitude of actors. In order to become socially relevant, they must be taken up by actors who translate them into meaning, action and structures. These interpretative processes have been described by Coburn and Turner (Citation2011a, p. 175) as ‘sense making’ that involves noticing information, making meaning of it, and constructing implications for action.

Interpretation processes in multi-level systems: These interpretive processes are influenced by the dynamics of the social interaction between actors on the multiple levels in education. The ‘governance view’ emphasises that complex social systems (such as education systems) are multi-level systems. A level is characterised by specific principles of action, which may differ from the logic of action on another level (Benz, Citation2004, p. 127). This implies that ‘interpretive processes’ between levels are most important for the implementation of a reform. New elements must be ‘re-contextualised’ (Fend, Citation2006) for the respective level, i.e. they must be ‘translated’ into actions and work structures that are appropriate for the specific level.

Policy elements embedded in contexts: The performance standard policy is certainly a case of ‘travelling policies’ (Ozga & Jones, Citation2006). Nationwide comparative tests were quite alien to German-speaking education systems before Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and PISA. The international large-scale assessment exercises have acquainted these systems with the idea of testing and have helped to build up knowledge and technology for the practical operation of such test systems. However, policies that are embedded in different systems may not work in an identical way and produce the same results as in the systems they were imported from (Ozga & Jones, Citation2006). For instance, it has been shown that ‘new inspections’ have been implemented in German education systems in a ‘low-stake’ or ‘soft governance’ manner that builds on rational insight, self-regulation and supportive context as the springboards of improvement (Böttger-Beer & Koch, Citation2008). In these respects, the Austrian school system is more similar to those of the German federal states than those of England, the Netherlands or the Scandinavian states (see e.g. Altrichter & Kemethofer, Citation2015; Windzio et al., Citation2005).

Are there extant conceptual models for evidence-based governance changes in the literature that could be used in our study? Altrichter and Kanape-Willingshofer (Citation2012) analysed Austrian documents about performance standard policy and identified two broad goals of the reform: (1) improved student competences, and (2) equality of opportunities and justice in the education system. They emphasised the necessity of multi-level recontextualization, and formulated hypotheses about plausible and non-plausible effects. Our paper builds on and extends their findings.

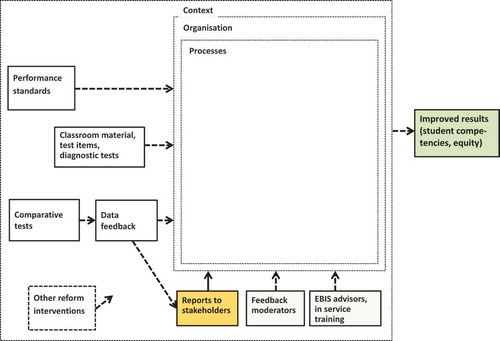

Another model that is relevant for our purposes is Coburn and Turner’s (Citation2011a) framework for research on data use, since it conceptualises an important part of the processes that are to be expected within performance standard policies. Their aspiration is to bring some structure into the ‘somewhat disorganised’ research base on data use (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011a, p. 175). In the centre of their framework (see ) is the process of data use, which is seen as an ‘interpretive process that involves noticing data in the first place, making meaning of it, and constructing implications for action’ (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011a, p. 175). This process is interactive as it is influenced by the dynamics of the social interaction between actors on the multiple levels in education.

Figure 1. Framework for data use (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011a, p. 176).

The processes of data use are embedded in and shaped by the organisational and political context of schools and districts, e.g. by data use routines, configuration of time, access to data, organisational and occupational norms, specific styles of leadership, and more general relations of power and authority (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011a, p. 175). Other important influencing factors are the interventions to promote data use that may be put forward in different levels of aggregation, such as individual tools, more comprehensive data initiatives, or high-profile policy initiatives including comprehensive accountability policies (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011a, p. 176). The final element of the framework is potential outcomes, which the authors identify in three areas: student learning, teacher and administrative practice, and organisational or systemic change (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011a, p. 177).

Wiesner, Schreiner, and Breit (Citation2016) recently proposed another model for data use in the context of Austrian performance standard policy. As per Coburn and Turner (Citation2011a), they focused on the ‘interpretive processes’ by distinguishing steps of reception, reflection, action and evaluation. ‘Reflection’ is the crucial element for effects for classroom and school development. The model is relevant to our discussion in that it refers to the specific Austrian policy model and its support structures. Since it focuses on the processes of data use and does not account for other possible trajectories of effect, there is still a need for a more comprehensive conceptualisation.

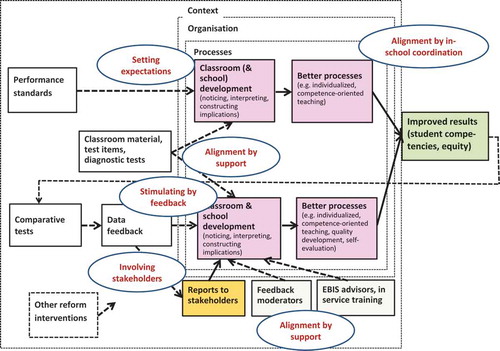

Ehren et al. (Citation2013) used a similar approach to ours, conducting a document analysis of inspection frameworks, legislation and documents to develop the ‘programme theories’ of new school inspections in six European countries. Via a cross-case analysis, they proposed a more general conceptual model of ‘new school inspections’, which, in short, consists of several relevant features of inspections (see , first column) that are supposed to improve education (last column). The most interesting parts are, however, the assumptions about intermediary processes: inspections work because they stimulate schools to increase their self-evaluative and development actions (third column), which in turn will boost the school’s improvement capacity and the overall quality of learning conditions (fourth column). These processes are fuelled by three intermediary mechanisms: inspections promote quality development by ‘setting expectations’ through their quality criteria; by ‘providing feedback’ that will stimulate and orientate improvement work if it is taken on board by the professionals in schools; and by ‘involving stakeholders’ who will engage in support or pressure schools to improve. The model is theoretically grounded and has been empirically tested (e.g. Ehren et al., Citation2015), and seems to include relevant ideas that may provide some stimulation for our endeavour of conceptualising a performance standard policy.

Figure 2. Intended effects of school inspections – proposed conceptual model (Ehren et al., Citation2013, p. 14).

Research design

We may summarise the argument to this point as follows: in the midst of inconclusive results on the effects of performance standards policies, we need more elaborate conceptual models that also account for the processes by which actors make use of and ‘re-contextualise’ these policies. While there are elaborate models on data use, performance standard policies seem to build on more effective processes than just data use that also have to be accounted for in a conceptual model.

This study comprises the initial part of a more comprehensive project that aims to understand the processes stimulated at the school level by performance standard policies. The aim of this paper is to reconstruct the assumptions underpinning educational policy. We are using a ‘policy scientific’ procedure proposed by Leeuw (Citation2003) and used for reconstructing other contemporary educational policies, such as ‘new inspections’ (see e.g., Ehren et al., Citation2005; Citation2013; Gustafsson et al., Citation2014; Jones & Tymms, Citation2014). ‘This method is empirical and analytic in nature, drawing strength from its reliance on multiple data sources (documents and interviews) as well as its use of diagrams to present the program theory.’ (Jones & Tymms, Citation2014, p. 317).

The procedure used in our analysis includes the following stages:

Reconstruction of the conceptual model based on a content analysis of relevant documents that are supposed to represent the official view of the performance standard policy. In our case, these documents include:

Legal documents that set out the key elements of the performance standards policy. These documents are amendments (Erläuterungen zur SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008; SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008) of two central educational laws, the School Organisation Act (SchOG, Citation2012) and the School Instruction Act (SchUG, Citation2012). Implementation of the new regulations was specified in two ministerial decrees (SchUG-Novelle, Citation2009, Citation2011).

Implementation documents provided by the BIFIE (i.e. the Federal Institute for Educational Research, Innovation & Development of the Austrian School System, Salzburg), which has been charged by the ministry with supporting the implementation of performance standards. These documents are available from the BIFIE webpage (https://www.bifie.at/). They include texts explaining the elements of the policy (BIFIE, Citation2012a, Citation2012b), but also material that is meant as practical support for teachers, such as example lesson plans and assignments for students (BIFIE, Citation2016a), and diagnostic tests (BIFIE, Citation2016b). Additionally, we analysed support opportunities for teachers and schools that are directly offered by the ministry (EBIS, Citation2012), and ministerial information about the new national quality-management system (SQA, Citation2012), which explains links to the performance standard policy.

Expert opinion documents. Since the official documents and webpages are not very systematic with respect to information regarding the processes meant to mediate between reform instruments and aspired effects, expert opinions by Austrian (see Eder, Neuweg, & Thonhauser, Citation2009; Eder, Posch, Schratz, Specht, & Thonhauser, Citation2002; Haider et al., Citation2003, Citation2005) and German expert groups (the report by Klieme et al., Citation2003, had an important impact on the Austrian debate) are used for reconstructing these aspects of the conceptual model.

(2) Particularly with respect to the processes that link reform elements and intended outcomes, there are sometimes conceptual gaps in the documents at hand, which were filled by reference to existing practices and by interpretations of the research group. In any case, validation of the conceptual model was the second step of the procedure, which took place in a workshop on 15 October 2016, in Graz, Austria, and was attended by educational researchers, officers from BIFIE, and in-service persons supporting teachers and schools in implementing the performance standards policy. The workshop produced some minor changes to the model but, in principle, supported the reconstruction.

(3) The last step is the evaluation of the conceptual model. It includes checks for consistency and ‘a check [as to] whether the mechanisms are clear or have any gaps’ (Jones & Tymms, Citation2014, p. 318). This is conducted through discussion of the various coordinating mechanisms in the previous section, while the final step of evaluation goes beyond the scope of this paper. That is, the realism of the model has to be analysed by using and extrapolating evidence from research literature. Of course, an ultimate check lies in using the conceptual model for empirical research about the policy.

Results

Policy elements

What we refer to as the ‘performance standard policy’ consists of a number of elements (see Altrichter & Kanape-Willingshofer, Citation2012, p. 359), which are explained step by step in :

Performance standards (see , line 1), which are to ‘set clear educational goals’ (Breit et al., Citation2012, p. 3). These standards describe intended learning results by listing those competences students are to have achieved by the end of the 4th (in German and maths) and 8th year (in German, English, and maths) of schooling (BIFIE, Citation2012a). For practical work in classrooms, these competences are clarified by exemplary student activities that are to serve as indicators for aspired learning results and as more concrete versions of the syllabus.

Periodical standard testing (see , line 3, first box). The first round of comparative national tests took place in May 2012 for 8th class Mathematics; results were fed back at the beginning of 2013. Every year, a full age cohort of students is tested in one of the subjects and age group performance standards are formulated for them; i.e. not all subjects and age groups are tested every year, but, for instance, in 2018 students of the 4th year of primary schools in maths will be tested, while in the next year students of the 8th class in English will be tested (BIFIE, Citation2016e). As a consequence, not all students and not all teachers are submitted to these testing exercises.

The results are fed back (see , line 3, second box) to students/parents, teachers, school leaders, and administrators on all levels, usually in December. All actors receive only ‘their’ results alongside comparative Austrian figures; e.g. teachers are given aggregated class results but not individual student performance figures; headpersons get their school’s results but not those of individual teachers etc. The performance figures are communicated as ‘fair comparisons’ that account for the special composition of the school with respect to, e.g., gender, regional, socioeconomic and migration indicators (BIFIE, Citation2012b). ‘The results of the standard testing and their feedback are to stimulate targeted processes of quality development in every school’ (BIFIE, Citation2016c).Footnote2

Support measures for implementation (see , lines 2 and 4). The webpage of the state institute for educational research, BIFIE, which has been mandated to manage and support implementation of the policy, has enumerated the following measures (BIFIE, Citation2012a):

Information ‘for all actors and system levels involved’ (BIFIE, Citation2012a);

Development and dissemination of classroom material, such as ‘publications, continuous updating of teaching, learning and support material (practical handbooks, topical booklets collection of test items and assignments, guidelines, brochures, video vignettes etc.), in printed and electronic form’ (BIFIE, Citation2012a). This material aims to ‘support teachers’ practical implementation of performance standards’ (BIFIE, Citation2016d).

Development and dissemination of diagnostic instruments ‘which enable teachers to check competences of students and classes and thereby considerably contribute to targeted support of students’ (BIFIE, Citation2012a).

Training ‘of disseminators, management personnel (regional and local administrators, principals) and of teachers at teacher training institutions’ (BIFIE, Citation2012a).

To aid understanding and interpretation of test results, school leaders may call upon so-called feedback moderators (Rückmeldemoderator/innen) for one or two dates.

The ministerial programme ‘Consultancy for School Development’ (EBIS, Citation2012) coordinates various offers of consultancy for school and classroom development and regulates quality criteria for such support measures.

(4) Including school partners (see , line 4, ‘reports to stakeholders’ box). The group-specific aggregation and selective communication of results is obviously intended to prevent comparison and competition between individual students, teachers and schools. However, there has been some effort to achieve in-school transparency: according to a letter from the then-education minister to all schools (BMUKK, Citation2012) part of the ‘performance standard feedback report’ has to be handed over to the elected representatives of parents, students and teachers of every school in due time. By a given date, these results have to be discussed by these representatives in the ‘school partnership council’. This opportunity will allow school partners ‘to discuss openly about strengths, weaknesses, and potentials for development […] and to define goals and responsibilities’ (BMUKK, 2012). Thereby, the conversations in the school partnership councils are meant to contribute to the quality development of schools. Feedback results and school partners’ reactions must also be taken up in the periodical ‘target agreements’ between the school management and regional administrators (BMUKK, 2012).

Policy goals and intended effects

Policies may have different intentions: they may be symbolic if using signs, words and images and referring to values that are cherished or feared by the public (Edelman, Citation1985); or they may have an ‘enlightening intention’, providing new and more human views on the functioning of society (Weiss, Citation1977). Here, we are concentrating on the instrumental side of the policy – i.e. on the intended and proclaimed effects on a policy field that have been made explicit by its proponents. When we are discussing the validity of the normative conceptual model, we will also have to attend to possible unintended effects.

What intentions are connected with the performance standard policy? In the documents we analysed, normative aspirations are included in longer texts that create broad ‘normative fields’, rather than a clear list of separate goals. For instance, on the BIFIE webpage one can read that the policy will support ‘the long-term and well-planned building up of essential competences’ (BIFIE, Citation2012a). Transparent and comparable educational goals aim to sensitise students and teachers to the quality criteria and provide an orientation for quality development. Performance standards require changes in the culture of classrooms in the direction of results- and competence-oriented learning and teaching (BIFIE, Citation2012a). The results of the periodic standard tests are meant to be ‘indispensable for steering and planning of education and also for quality development and assurance. Thus, educational standards serve for further developing the school system’ (Erläuterungen zur SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008). They enable ‘teachers to continuously compare the current state of competencies with the intended goals. This concrete comparison serves as basis for individual support of students’ (BIFIE, Citation2012a).

In our summary (see also Altrichter & Kanape-Willingshofer, Citation2012, p. 360) the Austrian standard policy is characterised by the following goals (see , ‘improved results [student competencies, equity]’ box on the right hand side):

(Goal 1) Central aims of the policy are improved student competencies, which are to be achieved by focusing actors on clear and comparable goals and via feedback information about reaching these goals.

(G2) Less clear and less often stated, yet visible in ministerial texts, is a wish for equity and justice in education. This is to be achieved by communicating comparable (= uniform for all) educational goals, by making output differences visible, and via more focused and individualised teaching and learning.

(G3) The documents analysed seem to indicate that the policy makers do not only think in terms of output goals, but also – and even to a more significant degree – in terms of different processes that are opening pathways to goals (1) and (2), but that seem to function as indicators for success in themselves. ‘Developing a new, individualising, results- and competence-oriented classroom culture’, and ‘evidence-based classroom and school development’ are the most prominent of these process goals.

It is exactly the reconstruction of these processes implied in the reform that we turn to in the next step to survey the remaining uncharted area in . Similarly to Coburn and Turner (Citation2011a), we refer to the multi-level structure of education by distinguishing interactional ‘processes’ that are influenced by and influence ‘organisational’ and ‘societal contexts’ (indicated by the rectangular frames in ). The ‘other reform interventions’ box in the lower-left-hand side of reminds us that simultaneous reforms may (unintentionally) reinforce or interfere with the processes that are the focus of the analysis.

Intermediary processes

What are the main processes that are intended to connect the policy elements with the intended effects? In our analysis, the following assumptions underpin the Austrian performance standard policy.

Setting expectations (process 1)

A central idea of the performance standard policy is to communicate the normative aspirations, or the goals of educational processes, more clearly than before (see , line 1). ‘The first function of educational standards is to provide schools with guidance in the implementation of binding educational objectives.’ (Klieme et al., Citation2003, p. 9; see also O’Day, Citation2004) Standards aim to provide a clear and transparent reference system for professional action, for learning, but also for political decision making with respect to educational development (Klieme et al., Citation2003, p. 47).

Nobody will deny that, even prior to the new policy, educational laws and syllabi included educational aims that were meant to communicate societal expectations for schooling. However, the new idea is that such goals must be formulated more clearly, in a language of measurable competences that students must master by the end of learning cycles (‘output orientation’).

Standards will ‘work’ if actors on different levels of schooling attend to their normative messages when they are making educational decisions. In principle, this is true for all relevant actors: school leaders should have these standards in mind if they are making decisions for professional development, and students will be well advised to attend to them when they organise their learning. The vast majority of statements, however, refer to teachers (Altrichter & Kanape-Willingshofer, Citation2012, p. 362); the assumption is that clarification of output goals will influence teachers’ lesson planning. Although the conceptualisation by Coburn and Turner (Citation2011a) was proposed for the process of data use, it seems useful for understanding this process: it is assumed that teachers will notice ‘performance standards’, will be able to interpret their (partially novel) messages, and will construct implications, in particular with respect to lesson planning. This standard-oriented classroom development will translate into improved educational processes, in particular into a type of competence-oriented teaching and learning (SchUG-Novelle, Citation2009, § 3 (2)) that will closely align (e.g. via observation and diagnostic testing) with individual competences and will apply – wherever necessary – individualised teaching strategies to support student development (SchUG-Novelle, Citation2009, § 3 (3); BIFIE, Citation2012a). This type of teaching will result in improved student competencies.

This process will also be relevant for more equitable results: First, clear, transparent and vigorously communicated competence goals will decrease the differences in performance requirements between schools and teachers (Eder et al., Citation2009, p. 254). Second, competence-oriented and individualised teaching will – due to diagnostic attention to individual learning – help disadvantaged students to achieve performance goals (Beer & Benischek, Citation2011, p. 21).

This process is functionally equal to the coordinating mechanism of Setting expectationsFootnote3 described in the conceptual model on inspections by Ehren et al. (Citation2013): the formulation and communication of performance standards aim to make actors, and in particular teachers, notice and interpret the novel educational messages, and, in consequence, change their classroom processes and more generally engage in school development. Of course, elements of Setting expectations are also included in other processes; performance tests and data feedback will not only function through the test results they insert into the system, but the instruments and the processes connected with them will draw also much attention and, thus, will signal the normative intentions of the policy to the actors (Patton, Citation1998). The same holds true for the public elements of process 4 and for process 3.

From a theoretical perspective, the mechanism of Setting expectations can be explained by neo-institutional theories. They hold that decisions in organisations are not made primarily with regard to efficiency criteria, but actors also seek legitimacy from their environment by fulfilling relevant normative expectations (Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977, p. 340; Scott, Citation2001). Particularly in situations of pressure and uncertainty, it is most important to conform to the environment’s norms; in consequence, organisations look for strategies and examples that are proven to provide normative inconspicuousness and legitimacy, e.g. by doing as other actors do, by taking over successful examples, etc. (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1991). In the context of a performance standard policy, conformity to standards, best in advance of testing, and continuously investing in development processes may provide such legitimacy. Adherence to classroom teaching material provided by the authorities, using diagnostic tests and in-service opportunities, and calling in ‘feedback moderators’ and development advisors may show to the environment that the teachers and the school are seriously attending to the new policy.

These processes of Setting expectations and schools adapting their practices to the normative messages of the ‘standard policy’ can lead to both positive and negative educational consequences. The search for legitimate responses in a school’s environment may stimulate enrichment of learning; however, it may also narrow and limit the educational processes when the entire work is focused on the sole purpose of achieving results on a limited set of indicators (e.g. Perryman, Citation2006).

Stimulating by data feedback (process 2)

There is a second fundamental process by which the performance standard policy aims to achieve its goals (see , line 3): the results of teaching and learning processes are measured by national comparative tests and they are fed back – in different aggregated versions – to students, teachers, school leaders and regional and central administrators (BIFIE, Citation2012a).

Figure 4. Conceptual model of the Austrian performance standard policy – Second step of reconstruction.

Actors are supposed to notice and interpret data feedback, and construct conclusions from it. For the interpretation of performance results, comparisons of goals and actual achievements are considered most relevant (Erläuterungen zur SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008; Wiesner et al., Citation2016, p. 19). Where there are discrepancies between aspiration and actual performance, processes of reflection and of development will be triggered. Since the Austrian governance system is considered to be ‘low stake’ and does not apply much accountability pressure to actors (Altrichter & Kemethofer, Citation2015; similarly for the German education systems, see Maier, Citation2010, p. 127), the main dynamic for improvement is to be derived from cognitive insight into the discrepancies between goals and achievement. These discrepancies have a dual function: they provide motivational stimulation to embark on improvement processes in the first place, and they are indicators for the fields that are in need of classroom and/or school development (Erläuterungen zur SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008).

Again, the level of teachers seems most important in the documents analysed. The underlying idea is that teachers’ reflection on ‘discrepancies’ will result in changes in their lesson planning and classroom teaching, which will reinforce the competence- and result orientation and individualised support. Contrary to process 1, official documents make much more reference to school-level use of data feedback: the legal document (SchUG-Novelle, Citation2009, § 3 (4)) explicitly refers to school leaders and teachers using data feedback ‘for long-term systematic quality development’ (Erläuterungen zur SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008). Furthermore, data feedback is expected to promote a ‘culture of continuous self-evaluation and shared quality development’ (Erläuterungen zur SchUG-Novelle, Citation2008) in schools.

Performance measurement and data feedback takes place ‘periodically’ – i.e. not every competence is measured every year. This may be for mainly economic reasons; however, the conceptual implication is that continuous feedback to individual actors is not necessary to trigger classroom and school development, but that discontinuous feedback to social groups of actors (the school, the maths faculty) will suffice for this purpose, because there will be processes of social coordination (see process 4 and process 5).

In addition, process 2 is meant to contribute to more equitable performance results. Comparative testing should allow the detection of social and regional disparities in provision and performance (Blömeke, Herzig, & Tulodziecki, Citation2005, p. 151; Eder et al., Citation2009, p. 265; Klieme et al., Citation2003, p. 27). This information will allow increasing and targeting organisational and instructional support for specific groups (Eder et al., Citation2009, p. 251). However, the special Austrian version of data feedback will not be particularly useful for individual diagnosis and support, since feedback to teachers is aggregated at a class level and does not offer information on individual students’ profiles (Eder et al., Citation2009, p. 254).

Measuring actual performance and feeding it back to actors is one of the cornerstones of the evidence-based governance logic. A theoretical basis for this coordination mechanism of Stimulating by feedback is offered by theories of performance feedback and goal setting (Visscher & Coe, Citation2002). Actors adapt their actions and/or their perception of the situation according to their interpretation of the ‘feedback information’ provided by their environment. An extensive body of research has shown that feedback may have a positive effect on learning – although not in all cases. Feedback cues, task characteristics and situational and personal variables may moderate the effect of feedback (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996).

While feedback theories are well established on an interpersonal level, and seem plausible for performance feedback at first sight, there has been some debate regarding whether it is feasible to transfer feedback theories and findings to the more complex conditions of a multi-level system (see Altrichter et al., Citation2016, p. 247). For most actors, performance data feedback is not personalised feedback that can be easily connected with specific actions. Rather, performance feedback is just one element in a more complex informational arena (Kuper, Citation2005, p. 101); more than one actor in a school must ‘notice’ its informational relevance and develop some shared ‘interpretation’ in order to become a valid stimulus for further development. Even if staff arrive at a common understanding of the messages of performance feedback, they may lack appropriate alternative teaching strategies to improve the situation (Dubs, Citation2006).

Alignment by support (process 3)

Implementation of the performance standard policy is accompanied by a support structure consisting of teaching material, exemplary assignments, test items, diagnostic tests, informational leaflets and webpages, in-service offers etc. (see , line 2). Such support instruments are meant to provide another step of clarification of the normative intentions implied in the performance standards. However, they not only signal normative messages, but are closer to school-level action: they operationally spell out how these expectations are to be translated into concrete actions and structures at the school and classroom level. In our reconstruction, they are positioned to influence the processes of noticing, interpreting, and constructing implications, thereby making it more likely that these processes yield results that are suited to the original policy intentions.

There are two additional types of support instruments that, in principle, function in the same way, though at specific points of the overall process: so-called ‘feedback moderators’ may be called in by schools to help with ‘interpreting’ performance feedback. Neither their task description nor their training equip them for supporting the process of ‘constructing implications’ for classroom and school development (Amtmann et al., Citation2011). For these processes, the EBIS advisory personnel and regional in-service trainers would offer assistance, albeit to a quantitatively limited degree. These functions are included in , line 4; however, in further discussions they will be subsumed in the function ‘support instruments’ for clarity purposes.

Theoretically, the coordination mechanism Alignment by support can also be explained through a neo-institutionalist rationale. These processes can be easily subsumed under the mechanism of Setting expectations; however, we chose to keep it separate in our model to indicate their special position in the rationale of functioning. While performance standards indicate performance goals and communicate a general idea of how to pursue them, support strategies go a step further: they clarify the normative expectations of the performance standard policy in a language that is closer to action and more precise, thus explaining what teachers should do when they want to translate the more general expectations into classroom action.

Support material and other support strategies take over (part of) teachers' recontextualization work by providing practical solutions for different aspects of competence-oriented teaching. If teachers accept these structural offers, find them useful and practical, and process them intelligently, then support material may be a very effective means of steering a reform in accordance with its proponents’ intentions.

However, this type of implementation support has been criticised because it does exactly the work for teachers that lies at the centre of the profession: to expertly translate educational goals and more general methodical ideas, based on the needs of specific students and contextual factors, into concrete educational arrangements. As a consequence, such strategies have been criticised for being ‘deprofessionalizing’, since they take over from teachers those tasks that would allow to cultivate their professionalism and develop their personal competencies. They seem to invite teachers to accept ready-made ‘recontextualizations’ and to abstain from checking such proposals through their ‘professional knowledge and experience’.

In our view, both consequences are plausible: support material may offer the chance for more stimulating learning experiences for students, and may challenge teachers to develop their professional knowledge. Alternatively, they may limit the teacher’s repertoire to those elements that are considered safe under the new regime, and thereby confine students’ learning experiences. Which alternative applies will depend on teachers’ existing level of professionalism and the specific context of the school; ultimately, it is an empirical question.

Involving stakeholders (process 4)

The Austrian performance standard policy also includes stakeholders of schools (, line 4, ‘reports to stakeholders’ box). A ministerial letter obliges all schools to share data feedback reports with parent and (upper secondary) student representatives and discuss it in meetings of the school partnership council (BMUKK, 2012). The idea is that (1) involvement of school partners will help to ensure that development focuses are found that are for the common good of all school partners; (2) ‘external observation’Footnote4 by non-professionals will motivate schools to more vigorous and more continuous development, since school partners may organise support for development or ask for improvement if the school fails to continuously strive for it (Ehren et al., Citation2013, p. 23). The binding function of obligatory contact points to external actors is also used when references to standards and performance results are made an obligatory item of the target agreements between schools and regional administration (BMUKK, 2012).

It is a recurrent element of new evidence-based governance models to include stakeholders in decision processes (see Altrichter & Kemethofer, Citation2016). According to their satisfaction with the development of the schools, they will voice support or criticism. In other instances, they will exit a given school and choose another one. According to theories of social coordination and of governance (e.g. Schimank, Citation2002; Boer, Enders, & Schimank, Citation2007), the inclusion of a 'third’ party will reinforce normative expectations and make it more likely that schools respond to them. From this perspective, social coordination between levels is seen as an important condition for reform.

Parent and student representatives and regional administrators in the process of target agreements are the only actors representing the societal context (‘political context’ in Coburn & Turner’s [Citation2011a] model) who are explicitly mentioned in the official explanation of the performance standard policy. In reality, schools may find themselves in situations in which alignment processes with other actors of the ‘societal context’ are necessary, e.g. regional media may comment on performance standard data, local business may suggest specific competence goals, etc.

However, also in a more general sense, societal expectations will provide important conditions for the appropriation of a new policy by in-school actors. For instance, the national ‘evaluation culture’ will be an important condition for use of data feedback (Gross Ophoff, Citation2013, p. 21; Maier & Kuper, Citation2012, 90). In all these respects, schools would have to consider in what way to take the various claims on board when making developmental decisions regarding performance standard processes. Thus, the mechanism Involving stakeholders also stands as a placeholder for possible alignment processes with the societal context.

Alignment by in-school coordination (process 5)

In the previous section, coordination between individual schools and external stakeholders was considered as an essential factor for implementing reforms. The same is true for in-school coordination. In the official documents, processes of in-school coordination are not explicitly mentioned; rather, they are implicitly alluded to by the fact that it is not always clear whether the explanations refer to individual actors or groups of staff, or ‘the whole school’. The official wording of process 1 seems to refer more often to individualistic processes, while terms such as ‘quality development’ and ‘quality evaluation’ used in process 2 seem to address coordinated action in schools. Again, the theoretical underpinning lies in the tenets of the governance perspective, for which coordination is an essential condition for the chance of reform taking root in an organisation and of becoming part of its normal operation. In , this process is referred to by the gap between the frame ‘processes’ and the frame ‘organisation’, which indicates the need for in-school coordination.

Summary and discussion

The paper is set in a political context, in which many European education systems have attempted to modernise their governance by setting up or refining some variety of an ‘evidence-based governance regime’. In this paper, we have reconstructed the normative conceptual model of the Austrian performance standard policy through a systematic analysis of official documents. The results show that five major social mechanisms of coordination are meant to organise the pathways from ‘policy elements’ to its ‘intended effects’ by aligning relevant actors to specific ways of organising and coordinating their actions. The labels of these coordinating mechanisms are phrased from the perspective of the external actors attempting to stimulate educational reform; of course, they can only be fully understood if the intended processes in reaction to the stimulation are complemented.

The conceptual model proposed here is compatible with Coburn and Turners’ (Citation2011a) model for data use, but extends their model to processes that occur before data use. This is plausible because similar processes are conceptualised. The coordinating mechanisms found in our model resonate with the findings by Ehren et al. (Citation2013) for European inspections arrangements. In our view, this makes sense because recurring elements may point to underlying functional patterns that are characteristic of ‘evidence-based governance’ arrangements that both inspections and performance-standard policies are incarnations of. This hypothesis may be followed up by further research. Another interesting question for analysis is whether performance standard policies in other education systems can be reconstructed on similar terms; alternatively, these policies may be built on different mechanisms and may take on very different meanings when they are embedded in alternative educational contexts (Ozga & Jones, Citation2006). In our discussion, we have shown that there are potential theoretical underpinnings for all the mechanisms (Ehren et al., Citation2015); however, they are referring to different theoretical traditions that may not always be compatible.

The limitations of our argument are clearly connected with the specific analytic strategy of document analysis and interpretative reconstruction, whose potential will only be revealed when it is followed up by further research steps. We have emphasised that the result of our study is a normative conceptual model in that it aims to reconstruct what the proponents want the performance standard policy to be and to deliver. As another step, it would be necessary to use existing research knowledge to verify the empirical plausibility of the conceptual assumptions.

This step cannot be conducted in this paper due to a lack of space. However, we expect that not all the mechanisms are empirically as well founded as they initially sound (see also Ehren et al., Citation2013). For instance, the mechanism of Setting expectations, which has proved powerful in European inspection models (Ehren et al., Citation2015), has not driven many teachers in the Austrian pilot implementation to use performance standards for lesson planning (Freudenthaler & Specht, Citation2005; Citation2006; Grillitsch, Citation2010; see also Asbrand, Heller, & Zeitler, Citation2012). Stimulating by data feedback was not effective for school improvement (at least in the short term) in European inspection studies (Ehren et al., Citation2015); research regarding the low-stake environments of Austrian and German schools systems has frequently shown that performance data feedback triggers disappointingly few classroom and school improvement activities (Altrichter et al., Citation2016; Grabensberger et al., Citation2008; Maier & Kuper, Citation2012).

Additionally, it would be worthwhile to learn more about unintended effects (which are usually not included in normative models). Inspection research has taught us that arrangements that produce more effects with respect to improvement tend to also trigger more unintended and undesirable effects of limiting student experiences (Altrichter & Kemethofer, Citation2015). This question seems to be particularly interesting since the Austrian performance standard policy puts much effort into support material, which may have either an enriching or a narrowing influence on student learning. These are empirical questions, and the original purpose of the conceptual model was indeed to frame empirical research regarding performance standard policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. It has been argued by proponents and critics of evidence-based approaches that many practical policies using this label fail to fully meet the criterion of being firmly grounded in research evidence. As a consequence, they suggest calling such policies data-driven or accountability-based governance (e.g. Bellmann, Citation2016). Nevertheless, the concept ‘evidence-based governance’ is in use at the policy level, on which our analysis focuses.

2. All quotations from sources in German have been translated by the authors.

3. In order to indicate the status of ‘coordination mechanisms’, they are written with an initial capital letter.

4. It may be debated whether student and parent representatives should be considered as actors that are external to individual schools or as ‘in-school partners’. In the centralist-bureaucratic tradition of schooling in Austria, it seems empirically valid to treat them as ‘external actors’ that are only included in in-school decision making on specific occasions, as prescribed by law.

References

- Altrichter, H. (2010). Theory and Evidence on Governance: Conceptual and empirical strategies of research on governance in education. European Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 147–158. doi:10.2304/eerj.2010.9.2.147

- Altrichter, H., & Kanape-Willingshofer, A. (2012). Bildungsstandards und externe Überprüfung von Schülerkompetenzen: Mögliche Beiträge externer Messungen zur Erreichung der Qualitätsziele der Schule. In B. Herzog-Punzenberger (Eds.), Nationaler Bildungsbericht 2012 (pp. 22–61). Graz: Leykam.

- Altrichter, H., & Kemethofer, D. (2015). Does accountability pressure through school inspections promote school improvement? School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26(1), 32–56. doi:10.1080/09243453.2014.927369

- Altrichter, H., & Kemethofer, D. (2016). Stichwort: Schulinspektion. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 19(3), 487–508. doi:10.1007/s11618-016-0688-0

- Altrichter, H., & Maag Merki, K. (2016). Steuerung der Entwicklung des Schulwesens. In H. Altrichter & K. Maag Merki (Eds.), Handbuch neue Steuerung im Schulsystem. (2nd ed., pp. 1–27). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Altrichter, H., Moosbrugger, R., & Zuber, J. (2016). Schul- und Unterrichtsentwicklung durch Datenrückmeldung. In H. Altrichter & K. Maag Merki (Eds.), Handbuch Neue Steuerung im Schulsystem (2nd ed., pp. 235–277). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Altrichter, H., & Soukup-Altrichter, K. (2008). Changes in educational governance through more autonomous decision-making and in-school curricula? International Journal of Contemporary Sociology, 45(2), 33–49.

- Amtmann, E., Grillitsch, M., & Petrovic, A. (2011). Bildungsstandards in Österreich. Die Ergebnisrückmeldung im ersten Praxistest. Das Rückmeldedesign zur Baseline-Testung (8. Schulstufe) aus der Sicht der Adressaten (BIFIE-Report 7/2011). Graz: Leykam.

- Asbrand, B., Heller, N., & Zeitler, S. (2012). Die Arbeit mit Bildungsstandards in Fachkonferenzen. Ergebnisse aus der Evaluation des KMK-Projekts for.mat. Die Deutsche Schule, 104(1), 31–43.

- Balog, A., & Cyba, E. (2004). Erklärung sozialer Sachverhalte durch Mechanismen. In M. Gabriel (Eds.), Paradigmen der akteurszentrierten Soziologie (pp. 21–42). Wiesbaden: VS.

- Beer, R., & Benischek, I. (2011). Aspekte kompetenzorientierten Lernens und Lehrens. In Bundesinstitut für Bildungsforschung, Innovation und Entwicklung des österreichischen Schulwesens (BIFIE) (Eds.), Kompetenzorientierter Unterricht in Theorie und Praxis pp. 5–28. Graz: Leykam.

- Bellmann, J. (2016). Datengetrieben und/oder evidenzbasiert? Wirkungsmechanismen bildungspolitischer Steuerungsansätze. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 19(Suppl 1), 147–161. doi:10.1007/s11618-016-0702-6

- Benz, A. (2004). Multilevel governance – governance in Mehrebenensystemen. In A. Benz (Ed.), Governance – Regieren in komplexen Regelsystemen (pp. 125–146). Wiesbaden: VS.

- BIFIE. (2012a). Text “Bildungsstandards“. Retrieved November 14, 2016, from https://www.bifie.at/bildungsstandards

- BIFIE. (2012b). Überprüfung und Rückmeldung. Retrieved July 4, 2012, from https://www.bifie. at/system/files/dl/bist_ueberpruefung-und-rueckmeldung_201205_0.pdf

- BIFIE. (2016a). Materialien für den Unterricht. Retrieved October 26, 2016, from https://www.bifie.at/node/51

- BIFIE. (2016b). Informelle Kompetenzmessung (IKM). Retrieved October 26, 2016, from https://www.bifie.at/ikm

- BIFIE. (2016c). Überprüfung und Rückmeldung der Bildungsstandards. Retrieved October 26, 2016, from https://www.bifie.at/standardueberpruefung

- BIFIE. (2016d). Materialien für den Unterricht. Retrieved October 26, 2016, from https://www.bifie.at/node/51

- BIFIE. (2016e). Aktuelle Standardüberprüfungen. Retrieved October 26, 2016, from https://www.bifie.at/node/59

- Blömeke, S., Herzig, B., & Tulodziecki, G. (Eds.). (2005). Gestaltung von Schule. Eine Einführung in die Schulpädagogik. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- BMUKK. [Bundesministerium für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur] (2012). Letter of the education minister on occasion of the first round of performance standard testing. September 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2017, from http://www.schulpartner.info/wp-content/myuploads/2012/10/Bildungsstandards-Kurzinfo.pdf

- Boer, H., De, Enders, J., & Schimank, U. (2007). On the way towards new public management? The governance of university systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. In D. Jansen (Ed.), New forms of governance in research organisations (pp. 137–152). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Böttger-Beer, M., & Koch, E. (2008). Externe Schulevaluation in Sachsen. In W. Böttcher, W. Bos, H. Döbert, & H. G. Holtappels (Eds.), Bildungsmonitoring und Bildungscontrolling in nationaler und internationaler Perspektive (pp. 253–264). Münster: Waxmann.

- Breit, S., Friedl-Lucyshyn, G., Furlan, N., Kuhn, J.-T., Laimer, G., Längauer-Hohengaßner, H., … Siller, K. (2012). Bildungsstandards in Österreich. Überprüfung und Rückmeldung. 4. Aktualisierte Auflage. Salzburg: BIFIE.

- Coburn, C. E., & Turner, E. O. (2011a). Research on data use: A framework and analysis. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives, 9(4), 173–206.

- Coburn, C., & Turner, E. (2011b). Putting the “use” back in data use: An outsider’s contribution to the measurement community’s conversation about data. Measurement, 9(4), 227–234.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The New institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 63–82). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Dinges, S., & Egger, M. (2015). Rezeption und Nutzung von Ergebnissen der Bildungsstandardüberprüfung in Mathematik auf der 4. Schulstufe unter Berücksichtigung der Rückmeldemoderation im Bundesland Oberösterreich. Salzburg: BIFIE.

- Dubs, R. (2006). Bildungsstandards: Das Problem der schulpraktischen Umsetzung. Netzwerk – Die Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftsbildung, 1, 18–29.

- EBIS. (2012). EBIS-Kompetenzprofil - Erster Bewerbungsaufruf zur Eintragung in die EBIS-Liste. Retrieved November 14, 2016, from http://www.sqa.at/pluginfile.php/976/course/section/446/20120625_EBIS_Kompetenzprofil_1st_CALL.pdf

- Edelman, M. J. (1985). The symbolic uses of politics. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Eder, F., Neuweg, G. H., & Thonhauser, J. (2009). Leistungsfeststellung und Leistungsbeurteilung. In W. Specht (Eds.), Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2009, Bd. 2: Fokussierte Analysen bildungspolitischer Schwerpunktthemen (pp. 247–269). Graz: Leykam.

- Eder, F., Posch, P., Schratz, M., Specht, W., & Thonhauser, J. (Eds.). (2002). Qualitätsentwicklung und Qualitätssicherung im Österreichischen Schulwesen. Innsbruck: StudienVerlag.

- Ehren, M. C. M., Altrichter, H., McNamara, G., & O’Hara, J. (2013). Impact of school inspections on improvement of schools – describing assumptions on causal mechanisms in six European countries. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 25(1), 3–43. doi:10.1007/s11092-012-9156-4

- Ehren, M. C. M., Gustafsson, J. E., Altrichter, H., Skedsmo, G., Kemethofer, D., & Huber, S. G. (2015). Comparing effects and side effects of different school inspection systems across Europe. Comparative Education, 51(3), 375–400. doi:10.1080/03050068.2015.1045769

- Ehren, M. C. M., Leeuw, F. L., & Scheerens, J. (2005). On the impact of the dutch educational supervision act; Analyzing assumptions concerning the inspection of primary education. American Journal of Evaluation, 26(1), 60–76. doi:10.1177/1098214004273182

- Erläuterungen zur SchUG-Novelle. (2008). Vorblatt und Erläuterungen zum BGBl. I Nr. 117/2008. Retrieved November, 14, 2016, from http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/Begut/BEGUT_COO_2026_100_2_434752/COO_2026_100_2_434762.html

- Fend, H. (2006). Neue Theorie der Schule. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Freudenthaler, H. H., & Specht, W. (2005). Bildungsstandards aus Sicht der Anwender. Evaluation der Pilotphase I zur Umsetzung nationaler Bildungsstandards in der Sekundarstufe I (ZSE-Report Nr. 69). Graz: ZSE.

- Freudenthaler, H. H., & Specht, W. (2006). Bildungsstandards: Der Implementationsprozess aus der Sicht der Praxis. Graz: ZSE.

- Grabensberger, E., Freudenthaler, H. H., & Specht, W. (2008). Bildungsstandards: Testungen und Ergebnisrückmeldungen auf der achten Schulstufe aus der Sicht der Praxis. Graz: BIFIE.

- Grillitsch, M. (2010). Bildungsstandards auf dem Weg in die Praxis (BIFIE-Report 6/2010). Graz: Leykam.

- Grillitsch, M., & Amtmann, E. (2012). Rezeption der Bildungsstandards und Erfahrungen mit der Ergebnisrückmeldung. Befunde der Begleitforschung zur Baseline-Testung auf der 4. Schulstufe. Salzburg: BIFIE.

- Gross Ophoff, J. (2013). Lernstandserhebungen. Reflexion und Nutzung. Münster: Waxmann.

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Ehren, M. C. M., Conyngham, G., McNamara, G., Altrichter, H., & O’Hara, J. (2015). From inspection to quality: Ways in which school inspection influences change in schools. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 47, 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.07.002

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Lander, R., & Myrberg, E. (2014). Inspection of Swedish schools: A critical reflection on intended effects, causal mechanisms and methods. Education Inquiry, 5(4), 461–479. doi:10.3402/edui.v5.23862

- Haider, G., Eder, F., Specht, W., & Spiel, C. (2003). Zukunft: Schule. Strategien und Maßnahmen zur Qualitätsentwicklung. Wien: bmbwk.

- Haider, G., Eder, F., Specht, W., Spiel, C., & Wimmer, M. (2005). Abschlussbericht der Zukunftskommission an Frau Bundesministerin Elisabeth Gehrer. Wien: bmbwk.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487

- Husfeldt, V. (2011). Wirkungen und Wirksamkeit der externen Schulevaluation. Überblick zum Stand der Forschung. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 14(2), 259–282. doi:10.1007/s11618-011-0204-5

- Jones, K., & Tymms, P. (2014). Ofsted’s role in promoting school improvement: The mechanisms of the school inspection system in England. Oxford Review of Education, 40(3), 315–330. doi:10.1080/03054985.2014.911726

- Klieme, E., Avenarius, H., Blum, W., Döbrich, P., Gruber, H., Prenzel, M., … Vollmer, H. J. (2003). Expertise: Zur Entwicklung nationaler Bildungsstandards. Bonn: BMBF.

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254

- Kuper, H. (2005). Evaluation im Bildungssystem. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Leeuw, F. L. (2003). Reconstructing program theories: Methods available and problems to be solved. American Journal of Evaluation, 24(1), 5–20. doi:10.1177/109821400302400102

- Maag Merki, K. (2016). Theoretische und empirische Analysen der Effektivität von Bildungsstandards, standardbezogenen Lernstandserhebungen und zentralen Abschlussprüfungen. In H. Altrichter & K. Maag Merki (Eds.), Handbuch Neue Steuerung im Schulsystem (pp. 151–181). Wiesbaden: VS.

- Maier, U. (2010). Effekte von testbasiertem Rechenschaftsdruck auf Schülerleistungen: Ein Literaturüberblick zu quasi-experimentellen Ländervergleichsstudien. Journal of Educational Research Online, 2(2), 125–152.

- Maier, U., & Kuper, H. (2012). Vergleichsarbeiten als Instrumente der Qualitätsentwicklung. Die Deutsche Schule, 104(1), 88–99.

- Mayntz, R. (2009). Über Governance. Institutionen und Prozesse politischer Regelung. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. doi:10.1086/226550

- O’Day, J. A. (2004). Complexity, Accountability, and school improvement. In S. H. Fuhrman & R. F. Elmore (Eds.), Redesigning accountability systems for education (pp. 12–43). New York: Teachers College Press.

- Ozga, J., & Jones, R. (2006). Travelling and embedded policy: The case of knowledge transfer. Journal of Education Policy, 21(1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/02680930500391462

- Patton, M. Q. (1998). Die Entdeckung des Prozessnutzens. Erwünschtes und unerwünschtes Lernen durch Evaluation. In M. Heiner (Eds.), Experimentierende Evaluation (pp. 55–66). Weinheim: Juventa.

- Perryman, J. (2006). Panoptic performativity and school inspection regimes: Disciplinary mechanisms and life under special measures. Journal of Education Policy, 21(2), 147–161. doi:10.1080/02680930500500138

- Resnick, L. B., Besterfield-Sacre, M., Mehalik, M. M., Sherer, J. Z., & Halverson, E. R. (2007). A framework for effective management of school system performance. In P. A. Moss (Ed.), Evidence and decision making. The 106th yearbook of the national society for the study of education (NSS), part 1 (pp. 155–185). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Rieß, C., & Zuber, J. (2014). Rezeption und Nutzung von Ergebnissen der Bildungsstandardüberprüfung in Mathematik auf der 8. Schulstufe unter Berücksichtigung der Rückmeldemoderation. Salzburg: BIFIE.

- Rürup, M. (2007). Innovationswege im deutschen Bildungssystem. Wiesbaden: VS.

- Schimank, U. (2002). Handeln und Strukturen. Einführung in die akteurtheoretische Soziologie. Weinheim: Juventa.

- Schimank, U. (2007). Die Governance-Perspektive: Analytisches Potenzial und anstehende konzeptionelle Fragen. In H. Altrichter, T. Brüsemeister, & J. Wissinger (Eds.), Educational Governance (pp. 231–260). Wiesbaden: VS.

- SchOG. (2012). Bundesgesetz vom 25. Juli 1962 über die Schulorganisation (Schulorganisationsgesetz). BGBl. Nr. 242/1962, zuletzt geändert durch BGBl. I Nr. 36/2012. Retrieved November 16 2016, from http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=10009265

- SchUG. (2012). Bundesgesetz über die Ordnung von Unterricht und Erziehung in den im Schulorganisationsgesetz geregelten Schulen (Schulunterrichtsgesetz - SchUG). BGBl. Nr. 472/1986, zuletzt geändert durch BGBl. I Nr. 36/2012. Retrieved November 14, 2016, from http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung/Bundesnormen/10009600/SchUG%2c%20Fassung%20vom%2025.05.2012.pdf

- SchUG-Novelle. (2008). Änderung des Schulunterrichtsgesetzes vom 8. August 2008. BGBl. Nr. 472/1986, geändert durch BGBl. I Nr. 117/2008. Retrieved November 14, 2016, from http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2008_I_117/BGBLA_2008_I_117.html

- SchUG-Novelle. (2009). Verordnung der Bundesministerin für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur über Bildungsstandards im Schulwesen vom 2. Jänner 2009. BGBl. II Nr 1/2009. Retrieved November 14, 2016, from http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2009_II_1/BGBLA_2009_II_1.pdf

- SchUG-Novelle. (2011). Änderung der Verordnung über Bildungsstandards im Schulwesen vom 24. August 2011. BGBl. Nr. 472/1986, geändert durch BGBl. II Nr. 282/2011. Retrieved November 14, 2016, from http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2011_II_282/BGBLA_2011_II_282.pdf

- Scott, W. R. (2001). Institutions and organizations. London: Sage.

- Specht, W. (2006). Von den Mühen der Ebene. Entwicklung und Implementation von Bildungsstandards in Österreich. In F. Eder, A. Gastager, & F. Hofmann (Eds.), Qualität durch Standards? (pp. 13–37). Münster: Waxmann.

- SQA. (2012). Webpage “Schulqualität Allgemeinbildung“. Retrieved November 16 2016, from. http://www.sqa.at/

- Tillmann, K.-J., Dedering, K., Kneuper, D., Kuhlmann, C., & Nessel, I. (2008). PISA als bildungspolitisches Ereignis. Wiesbaden: VS.

- Visscher, A. J., & Coe, R. (2002). School improvement through performance feedback. London: Routledge.

- Weiss, C. H. (1977). Research for policy’s sake. The enlightenment function of social science research. Policy Analysis, 3(4), 531–545.

- Wiesner, C., Schreiner, C., & Breit, S. (2016). Die Bedeutsamkeit der professionellen Reflexion und Rückmeldekultur für eine evidenzorientierte Schulentwicklung durch Bildungsstandardüberprüfungen. Journal für Schulentwicklung, 20(4), 18–26.

- Windzio, M., Sackmann, R., & Martens, K. (2005). Types of governance in education – A quantitative analysis (TranState Working Papers No. 25). Bremen: University.