ABSTRACT

Global reforming driven by neoliberal ideas is today reshaping educational systems. This study explores how a national policy incentive, aimed at changing teacher education in Sweden, is transformed and realized into educational practice and how pedagogic discourses are operating in and through the primary teachers’ examination practice in Sweden. The aim is also to explore which competencies are legitimized and thus form the knowledge base for primary teachers. The study is conducted through a qualitative and quantitative, theoretically based, analysis of all examination tasks (n = 322) in the primary teacher education at a teacher education department located at one of Sweden’s largest universities. The qualitative software package Nvivo was used for the qualitative analysis and the statistical software SPSS was used for the quantitative analysis. The result shows that most examinations involve the examination of methodological/didactical knowledge related to teachers work in the classroom (out of horizontal knowledge structures) and that students lack opportunities to practice and show analytical skills, with vertical knowledge structures, in their examinations.

Introduction

Neo-liberal notions and discourses such as market-based leadership principles now drive national educational systems, in what has been described as a conservative ‘modernization’ of schooling and instruction. This article has an interest in particular reforms that have been directed at teacher education in Sweden (SOU Citation2008:109; Prop Citation2010/10: 89). The aim with the present study is to explore how this latest teacher education reform has been acted on at a teacher education institution in Sweden, through an analysis of primary teacher education’s examination practice.

Teacher education has been involved in the neoliberal reforming in two ways: firstly, in terms of itself being subject to far reaching conservative modernization, or what Beach and Bagley (Citation2012, Citation2013) refer to as re-traditionalizing, and secondly in terms of its role in preparing future teachers for future professional work in the now decentralized, flexible, competitive and quasi-market national educational context (Börjesson, Citation2016; Nilsson Lindström & Beach, Citation2015). This is as it seems also an international tendency. Hargreaves (Citation1994), Garm and Karlsen (Citation2004), Young (Citation2009). Goldstein (Citation2014) and others, have shown how teacher education programs have become more ideologically and politically important to governments in recent decades, not only for national purposes, but also for European/global purposes, often in relation to the discourse of knowledge-based economies. Furthermore, there has been an introduction of teacher standards and teacher certification all over the world (Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2016; Darling Hammond, Citation2017) as part of an emergence of a worldwide discourse of teacher quality, teacher effectiveness and pupil achievement (Alvunger, Citation2016; Goldstein, Citation2014; Klette & Hammerness, Citation2016). Changes have thus been made to the organization of teacher education, to the rhetoric that describes the way teachers and pupils are expected to behave, and to the kind of knowledge that is considered legitimate and valuable for both the individual and society, with huge consequences for the people who work in educational institutions and the societies in which we live (Singh, Thomas, & Harris, Citation2013).

This study focuses on the way the changes described above have come into practice in the latest round of reform directed at teacher education in Sweden, introduced in 2011 (SOU Citation2008:109; Prop Citation2009/10: 89). This teacher education reform can in many ways be seen as a change in the policy that was all-pervasive for Swedish teacher education reforms between 1947 and 2007: the ambition to develop a unified single teacher education program with a common scientific knowledge base (Beach, Bagley, Eriksson, & Player-Koro, Citation2014). In this most recent reform, these efforts have been abandoned for a return to a structurally divided teacher education program that is grounded in the argument that teachers require different types of knowledge and abilities depending upon their pupils’ age group.

The research behind the article has been conducted at a teacher education department located at one of Sweden’s largest universities. The overall aim is to explore how the policy ideas that are expressed in reform texts, the Teacher Education Commission’s report entitled ‘A Sustainable Teacher Education’ (SOU Citation2008:109) and the subsequent parliamentary White Paper that was based on it (Prop Citation2009/10:89), have been transformed into local teacher education practice. The aim is to examine the possible implications of the changed policy, particularly in relation to the professional knowledge that is communicated to the category of students who study the program for prospective primary teachers and identify how the national policy has been transformed, distributed and translated in local policy documents that regulate the program and its outcome. We will seek to identify the characteristic pedagogic discourses that occur in these documents. We will also examine how these discourses are operating through the teacher education examination practices and how they thereby construct the legitimate, professional knowledge base and professional identity for prospective primary teachers. The following research questions will be addressed:

What pedagogic discourses operate in the examination practices?

What skills and competencies are legitimized through these discourses?

For this article, we have carried out a qualitative, theoretically based, analysis of all the 322 examination tasks that are part of the teacher education program for future teachers who are qualified to teach in the pre-school class (K) and compulsory school grades 1–3 as well as primary school grades 4–6. The qualitative analysis and subsequent coding of the documents have been further analysed quantitatively using descriptive methods and exploratory factor analysis. The purpose of these analyses is to identify the various pedagogic discourses found in the material as well as the skills and competencies that these discourses carry, which in this way could be defined as the legitimate knowledge base for teachers working in primary school. The analysis is grounded in theoretical assumptions borrowed from Basil Bernstein’s (Citation2000) sociology of education. This means that education practices, here exemplified with the primary teacher education, are seen as complex public practices that are controlled by actors at different levels who sometimes make various and even contradictory demands that the organization is expected to meet.

Theorising policy interpretation, translation and enactment: a Bernsteinian perspective

The teacher education program is a complex organization that is controlled through political processes, where actors at different levels of society create frameworks and shape the program’s purpose, content and expectations through policy. Teacher education policies are thus policies that are to be interpreted and translated into practical teaching situations within the framework of teacher education practices. In this study, the outcome of the process of interpretation and translation of the latest teacher education policy has been put into action and studied from a theoretical standpoint through Bernstein’s conceptual model about the pedagogical device. The pedagogic device describes the processes by which policy knowledge is selectively translated into what is taught and how it is evaluated as acquired, i.e. the pedagogic discourse. The pedagogical device is in other words a description of the processes of creating policy that forms a pedagogic discourse.

In this study, we adopt Bernstein’s (Citation2000) suggestion to interrogate the pedagogic discourse as the embedding of two discourses (p 32), the instructional discourse (the what) that represents a discourse of transmission and acquisition of specific competences, skills and theoretical knowledge and their relation to each other, embedded in the regulative discourse (the how) of social order that in this case is conceptualized as forms of examination. We also adopt Ensor’s (Citation2004) notion that the teacher education has a third embedded discourse that could be thought of as teaching repertoires that constitutes a notion of ‘best practice’ for implementation in classroom teaching.

Recontextualisation are, according to Bernstein, processes of interpretation and translation of policy that constitute specific pedagogic discourses. These processes take place in a range of different context of practices within the educational system, and theoretical knowledge is interpreted and re-shaped in relation to other discourses, such as political intentions, research, policy documents, school traditions and more. Recontextualisation takes place within both official and pedagogic fields. In terms of teacher education, policy production occurs at this level, firstly in the official recontextualising field (ORF) dominated by the state and its selected ministries and secondly in the pedagogic recontextualising field (PRF) – consisting of the institution offering teacher education, where syllabi and study programs are put together. This means that education policy is not the only constraint that influences upon and shape the pedagogical discourse, which implies that it is difficult to determine how and in what ways a change of policy will have on an educational practice, as also previous policy studies of teacher education have demonstrated (Cfr Beach & Bagley, Citation2013; Beach et al., Citation2014).

This study’s focus is on the processes, conceptualised as evaluative rules, in which the pedagogic discourse is transformed into pedagogic practices where teaching and learning take place (Bernstein, Citation2000; Singh, Citation2002). A central aspect of the evaluative rules is the fact that these rules make visible the shape and content of the pedagogic discourse. More specifically, this study’s analytical focus is directed at processes included in the evaluation rules, in the practices through which the results of the program are evaluated and assessed – in this case, in the documents that describe the content of the examination and the assessment criteria, i.e. in tasks and examinations that teacher education students are expected to pass. Evaluative rules and the theoretical concepts that describe pedagogic discourse are therefore central to the analysis of the empirical material for the study, which will be discussed in more detail in the section on methodology. However, it is important to point out that this study will focus on the pedagogic discourse as evidenced in the documents and what knowledge appears as legitimated through these. If these have a casual effect to the policy, change is not possible to determine through this research.

Teacher education policy and practice in Sweden

As part of the radical reform of the Swedish education system that was orchestrated by the ‘right wing’ Swedish government that was elected in 2006, several new teacher education programs were instituted in the autumn of 2011. This is not the first time Sweden’s teacher education program has been reformed. Major reforms also have been carried out in 1968, 1988 and 2001.

What the previous reforms of the teacher education programs had in common was a clear ambition to generate one unified teaching profession with a single knowledge base, grounded in research, for teachers in both primary and secondary education. This fifty-year effort to develop a unified teacher education program has been upended by the new teacher education reform. Instead, in the texts produced arguing for this new reform there appears to be an ambition to return to a teaching profession in which the teachers require specific knowledge depending upon the age of the pupils they teach; age groups, it is claimed, represent a certain mental maturity (Beach, Citation2011; Beach & Bagley, Citation2012). These notions, however, are not new. Indeed, they resemble thoughts that pervaded Swedish schools and teacher education programs before 1948 (SOU Citation1948:27; SOU Citation1952:33) and that reforms from 1968 and onward have struggled against, replacing them with a common knowledge base for all teachers (Beach & Bagley, Citation2012). The most recent reform of the teacher education program can thereby be viewed as a ‘conservative modernization’ since the teacher education program no longer offers the same degree to all teachers and is once again organized into different degrees, with specializations aimed at the school system’s different age groups. Furthermore, knowledge of one’s subject area is emphasized, for example, especially for teachers who work with pupils in the upper grades and a teacher’s basic knowledge now has a more specific specialization in methodology and knowledge of psychological stages of development and maturity (Government Bill Citation2009/10:89, 2010; SOU Citation2008:109). In other words, the reformed teacher education program amounts to an altered view of the teaching profession and of the various skills that a teacher needs to help pupils develop and gain knowledge, and hence also an altered view of the quality and outcome of the Swedish education system.

The present primary teacher education program is a four-year program. It is structured around explicit learning objectives and has a clear organizational structure. Every teacher education institution then makes choices about how they put together courses and examinations within the framework set out by the Swedish state. The program is organized into three parts: a core of educational science (UVK) where knowledge that is considered to be central to the teaching profession such as pedagogical studies, special needs education, youth development and psychology of learning together with primarily basic teaching skills must be given space (one year of study). Added to that are subject knowledge and didactic skills in the subject for a few established subjects (two and a half years of study) and student teacher placement (one term of study). The national policy is in other words moved, interpreted and translated into local policies and practices. This process of coding and recoding that has been described by Stephen Ball (Citation1993) as an iterative process of putting texts into action is a way of making sense of policy – what do the texts mean for us and what do we have to do? In this paper, our intention is to study how the national policy intentions (SOU Citation2008:109; Prop Citation2009/10:89) are transformed and expressed in policy documents aimed at regulating the program and its outcome in a specific teacher education institution in order to find out what knowledge and skills are expressed in and through these documents.

Previous research

Research done by Beach (Citation1995), Jedemark (Citation2007) and Player-Koro (Citation2012), in which the teacher education program’s pedagogic discourse has been the object of the studies, show how dominant traditions in teacher education institutions have a more obvious significance in teacher education practice than intentions and national policy statements.

But on the other hand, studies also show that policy statements have effects on what skills are identified as important for the teachers’ professional knowledge base. Beach and Bagley (Citation2013), for instance, have studied policy discursive changes in both a British and a Swedish context and they assert that several trends, which have reinvented teacher education as teacher training in particular subjects, have reduced the teacher’s knowledge base. They claim that the teaching profession is thus at risk of being de-professionalized.

Furthermore, Wågsås Afdal (Citation2012) and Wågsås Afdal and Nerland (Citation2014) have done research showing the differences between Nordic teacher education policies and practice. In these studies, the Finnish teacher education program, which is built from a policy statement that teacher education should be research-based, is compared with the Norwegian education program, which emphasizes a more professional-based teacher education both in relation to knowledge structures and knowledge relations, and in relation to the knowledge base of the teachers. The results show that on the one hand, these two countries’ teacher education programs have much in common – for example, that the pupils and their development are important. On the other hand, teacher education students in these two countries define and interpret what is going on in the classroom in different ways: the student teachers in the Finnish research-based teacher education program, use conceptual theories to understand what is taking place in the classroom, while the student teachers on the Norwegian profession-based teacher education program, mostly understand pedagogical occurrences in context. The conclusion according to Wågsås Afdal and Nerland (Citation2014) is that the premise for understanding pedagogical work leads to different pedagogical identities that are, in terms of profession, ‘weighted’ differently. The problem with a profession-based teacher education program, they argue, is the lack of an official, shared knowledge base and an explicit professional language. This in turn risks that the knowledge base becomes individualized and consequently invisible to the public eye.

The most recent Swedish teacher education program has also been in focus for many studies. A study done by Sjöberg (Citation2011) showed that between the middle of the 20th century up until the most recent teacher education reform, the teacher education program has been discursively altered and that discourses as well as governing technologies have interacted with policy both in European, national and in local contexts. This interaction has contributed to the current positions occupied by both teachers and pupils as entrepreneurs who are at the same time strictly regulated performative subjects. Beach et al. (Citation2014) also show that the new Swedish teacher education program is based upon out-dated dualistic rationalities and that the anxiety which was the basis for once again sub-dividing the teacher education program was unjustified, since the teacher education program was, in practice, always – even during the period between 1988–2010, when the ideal was one unified program – operated according to a principle of division or from strictly classified discourses (Bernstein, Citation2000). Like Beach and Bagley (Citation2013), Sjöberg (Citation2011) suggests that in this way the teaching profession is at risk of being de-professionalized.

The altered knowledge rationalism in relation to what is considered as teacher’s legitimate knowledge base in the new teacher education policy (SOU Citation2008:109) has been problematized in studies done by Beach (Citation2011), Beach and Bagley (Citation2012) as well as Nilsson Lindström and Beach (Citation2015). These studies make visible how the emphasize in studying subjects like pedagogics, psychology, sociology and philosophy (the teacher education Trivium, see below), which has traditionally been strong in the teacher education program has been down played in favour of a greater emphasis on subject knowledge (the teacher education Quadrivium) as well as subject methodology (didactics) (Bernstein, Citation2000). The authors claim that a shift has taken place, going from knowledge structures with a vertical knowledge base to knowledge structures with a horizontal knowledge base and a technical economic rationality (Bernstein, Citation1999). But there has also been a shift toward a preference for knowledge that has to do with how one works pedagogically – know-how – instead of knowledge of the basis for pedagogical questions and practice – know why (Beach, Citation2011; cf. Brante, Citation2010). This change can influence a teacher’s ability to reflect upon his or her own practice, and teachers can thus become less prepared to meet a changing educational practice. Further, this can make teachers more vulnerable for economic and ideological incentives.

Since learning and teaching have become a global means of creating competition for teacher quality, teacher effectiveness and student achievement have been accentuated in both the political and pedagogical agenda. According to, for example, Hattie (Citation2009) and Darling Hammond (Citation2010) teacher quality and teacher effectiveness are important factors for student achievement. Several countries have therefore developed standards that explicate the knowledge and competencies required to function as a teacher. In some countries, these standards are combined with different kinds of certification (Alvunger, Citation2016; Adoniou & Gallagher, Citation2016; Darling Hammond, Citation2017). Furthermore, standards are more often used in teacher education, and according to, for example Klette and Hammerness (Citation2016) and Darling Hammond (Citation2010, Citation2017), they are among several indicators used to construct high quality teacher education. Other important indicators, according to Kennedy (Citation1998), Kennedy (Citation2006) and Klette and Hammerness (Citation2016), among others, are clearly articulated and shared visions, strong inner coherence of the teacher education programs and the possibility for the students to enact practice.

In sum, current research shows that issues regarding teacher education are of primary political interest globally and that the content and organization of teacher education programs is functioning like a policy epidemic (Ball, Citation2008), rendering the content and organization of teacher education programs in Europe more and more similar (Beach & Bagley, Citation2012; Garm & Karlsen, Citation2004; Sarakinioti & Tsatsaroni, Citation2015). Teachers’ professionalism, identity and knowledge base are becoming important pedagogical as well as ideological issues (Goldstein, Citation2014; Klette & Hammerness, Citation2016). Previous studies also show that the most recent Swedish teacher education program differs discursively from the teacher education discourse that was prevalent in the middle of the 1980s and that the content of the new teacher education program shows evidence of a change in knowledge rationalism, where the need for knowledge in schools teaching subjects (such as mathematics, language, science, etc.) and in didactic skills in the subjects together have been given more weight, and where knowledge in educational science (stemming from psychology, sociology and pedagogy) has decreased. Knowledge structures in teacher education seem to have shifted from a vertical to a horizontal knowledge base. Yet another difference from the previous teacher education program is the way it is organized into a stricter classification between subject matter and educational science (Sjöberg, Citation2011).

The present study is thus based on these earlier findings, showing both a changing rationality in recent Swedish teacher education policy, but also that reforms are difficult to implement, since historical discourses and traditions have strong implications on the educational practice. Consequently, in this study we will show the pedagogic discourses that define the legitimate knowledge for primary teachers that appear in descriptions of tasks and examinations that teacher education students are expected to pass a few years after the implementation of the new reform and relate these to ideas and discourses present in the latest teacher education reform.

Methodology

This study was carried out in a large teacher education department in Sweden. The empirical material is comprised of all policy documents that regulate the program and its outcome, that is to say, program syllabuses, course plans, study guides and examination tasks, including criteria for assessment. The selection is based on Bernstein’s theoretical understanding of the construction of the pedagogic discourse and how this discourse is made visible through the rules that provide the criteria for evaluation and assessment (see above).

The courses that we have studied were offered during the school year 2014/2015. All of the courses needed for a major in primary teacher education, grades K-3 and for grades 4–6, were included in the study, with a few exceptions due to a lack of archived documentation and hence no documents to study.Footnote1 For the primary teacher education program, grades K-3, there were 22 courses included in the study, with a total of 149 examination tasks. For grades 4–6 were 25 courses and 173 examination tasks included. In both teacher education programs, the student follows 22 courses but since the primary education teachers for grades 4–6 choose a major, we have studied more courses and examination tasks than a student on the program would have taken ().

Table 1. Summary of the study’s empirical material.

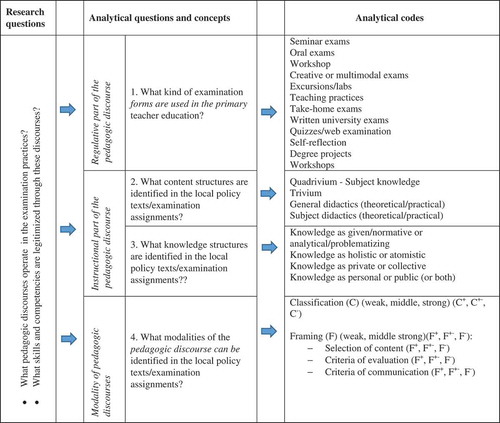

The empirical material was analyzed in several steps. First, in order to take stock of the material and identify patterns in its content and format, a theoretically informed qualitative analysis (see Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) of all the syllabi, study guides and examination tasks was undertaken. Theoretical-based qualitative analysis techniques were used in order to move from a broad reading of the data towards discovering patterns and the framing of specific research questions (see ). The qualitative data analysis software package – Nvivo – was used as an organizational and analytical tool in this process. The analysis is driven by Bernstein’s theoretical concept of the pedagogic discourse. The data were coded using analytical questions and concepts into codes (see ), where the instructional as well as the regulative aspect of pedagogic discourses became the main structuring categories (Bernstein, Citation2000). Concepts from Bernstein as well as from Berlak and Berlak (Citation1981) and Briant and Doherty (Citation2012) were used in this coding. The coding process is illustrated in and will be described in more detail in the following text.

Figure 1. The relationship between research questions, analytical questions/concepts and analytical codes in the study.

Through the qualitative analysis, content and knowledge structures were identified as well as which examination forms that were used. To each examination task are thus attached a set of codes that define their respective pedagogic discourse. However, the first step in the qualitative analysis was to read through all the documents with the aim of identifying which codes could be applied to the analytical process. In this phase, we alternated between the information that the empirical material provided and the theoretical premise (Berlak & Berlak, Citation1981; Bernstein, Citation1990, Citation1999, Citation2000, Citation2003; Briant & Doherty, Citation2012). The process used was thus abductive reasoning.

Next, the regulative, respectively the instructional part of the pedagogic discourse was identified and coded as follows:

The regulative part of the pedagogic discourse was conceptualized in what kind of examination forms were used in the courses examinations (see , analytical question 1). Every examination was coded with one of the examination forms: oral examinations, creative or multimodal exams, excursions/laboratory, teaching practices, take-home exams, written university exams, quizzes/web examinations, workshops, self-reflections, and degree projects.

The instructional part of the pedagogic discourse was coded in two steps (see , analytical question 2 and 3). First with, with what kind of content structure or which area of knowledge the task involved (see , analytical question 2). Here we used Bernstein’s description of teacher education programs in terms of Trivium and Quadrivium (see , column analytical codes), the two knowledge components that teacher education historically consisted (Bernstein, Citation2003). The teacher education Trivium refers in this description to general pedagogical knowledge, such as the problematizing of attitudes toward teaching and learning processes and their various outcomes. This kind of knowledge corresponds to the educational science part of the teacher education in Sweden (see above). Bernstein refers to this knowledge as ‘inner knowledge’, which means that Trivium according to this conceptualization is the foundation for the Quadrivium, which in turn is the other form of professional knowledge for teachers. Quadrivium is related to the subjects that teachers teach in the school and is correspondent to the subject studies part of the Swedish teacher education (Beach & Bagley, Citation2012). Due to the empirical nature of the material, we constructed codes for subject knowledge (Quadrivium), Trivium knowledge, and four different forms of didactic knowledge; theoretical versus practical perspectives of general didactics and theoretical versus practical perspectives of subject didactics. Since the content of the tasks could contain several content structures each task could be coded with more than one of these codes (see , column analytical codes).

In the second, the instructional discourse was coded based on the third analytical question (see ), knowledge structures in the examination tasks. Like the coding of examination forms, these codes were used as dichotomous variables. Here four codes were used: 1) if the examination task covered knowledge seen as being of a holistic character or if it was atomistic, 2) if the examination task was constructed in a way so that the students had to collaborate (collective knowledge) or if they were supposed to deal with the examination task individually (private knowledge), 3) if the knowledge was to be acquired primarily from established theories and knowledge (public) or from their own experience (personal) or both (personal and public), and finally, 4) if the examination task required the students to show analytical and/or problematizing skills or if the task had a given or normative character (see , column analytical codes).

The last analytical question is about identifying the modality of pedagogic discourse, which describes the character of the pedagogic discourse (see ). Theoretical concepts used for this description is classification (C) and framing (F), which describe the character in terms of relations between subjects, selection of subject content, and rules for transmission and acquisition (Bernstein, Citation1990). Every examination task was analyzed concerning whether the content of the course (including the examination tasks) was constructed as separate parts (strong classification, C+) or as integrated (weak classification, C−) or somewhere in between (middle classification, C+-). When focusing on framing aspects (F), three different aspects were in focus: selection of content, criteria of evaluation and criteria of communication. The first aspect, selection of content, focused on whether the educators or the students were the ones who decided which content knowledge was to be presented in the examination task. Strong selection of content (F+) implies that the content is determined by the educators, while a weak selection of content (F−) implies that the student can choose what kind of knowledge to demonstrate in the task. Due to the empirical material, a third code was constructed, where examination tasks included both aspects. The second framing aspect dealt with criteria of evaluation, looking for how explicitly the criteria of evaluation were presented in the task (strong (F+), middle (F+-), weak (F−). The third and last aspect regarded criteria of communication. Here the focus was on the formalities in the examination tasks, as for example on length of texts or presentations, or other regulations not concerning content knowledge aspects or knowledge structures.

After the material was coded, the next step was to go beyond the semantic content of the data and start to analyze these codes quantitatively and relate them to the aim of the research. The coding process of the data in Nvivo meant that each document was stored as a post in a database and the subsequent coding defined variables with numeric values. The database was in the next step exported to the statistical software SPSS for further quantitative analysis. In the following, we will describe the quantitative data analyses used.

In order to examine which pedagogic discourses are features of the primary education program syllabi and examination tasks, the empirical material was analyzed quantitatively through a descriptive compilation and through exploratory factor analysis. The purpose was to distinguish what sort of knowledge and competencies are characterized as legitimate for a teacher who is teaching in a primary school and thereby define the primary education teacher’s legitimate knowledge base.

Exploratory factor analysis is a form of factor analysis that emphasizes ‘exploration’ of a set of data, in this case the documents and their respective coding. The method is based upon the assumption that there are one or several underlying dimensions in the data – in this case that there are several different categories of examination tasks that are similar in character in terms of pedagogic discourse and hence represent different examination practices (Howitt & Cramer, Citation2005). The analysis thus examines the pattern of covariance between the analytical questions/concepts and the codes. Whether there are such underlying dimensions or not is hence an empirical question and is not based upon an a priori categorization of program syllabi, study guides and examination tasks. For this study, this means that the co-variance between the analytical questions/concepts and the codes places the analyzed documents into categories (factors) based on the same character of pedagogic discourse.

Reducing the variables to a lower number of factors in this way is a technique that has its roots in psychological measurement (Howitt & Cramer, Citation2005). The factors that stand out in an exploratory factor analysis can become the springboard for further analysis and studies. In this study factor analysis has been used to get an overall understanding of which pedagogic discourses stand out in the examination tasks used on the teacher education program and how these can be understood. That is to say, in studying the teacher education program syllabi and examination tasks, we were able to identify the kinds of knowledge, skills and teacher identities that stand out as legitimate in relation to the teacher’s professional knowledge base. Through these codes we can identify the current form of examination, the way the students are encouraged to account for their learning on examination tasks, what type of content structure the examination is focused on, and what type of knowledge structures are reflected in the task. Moreover, since the examination tasks can be traced to the part of teachereducation where they occur, it is also possible to determine how different examination practices appear in the different parts of the teacher education program.

Results

The following segment will be introduced by presenting the descriptive quantitative analysis the empirical material. Thereafter, we will present the factor analysis.

The main structuring categories of the qualitative coding process were, as described earlier, to identify the regulative, respectively the instructional part, of the pedagogic discourse. According to Bernstein (Citation2000), the regulative discourse is the dominant part of the pedagogic discourse because of its ‘moral’ character, which creates the direction for ‘what to do’ in a pedagogical situation. ‘The regular discourse produces the order in the instructional discourse’ (p. 34). shows the results from analysis of the regulative discourse conceptualized as forms of examination.

Table 2. The regulative discourse – examination forms.

The compilation in shows that certain aspects of the pedagogic discourse feature more frequently in the material. From the table, it is shown that in the regulative part of the discourse certain forms of examination and ways of accounting for one’s learning dominate. Seminars (39%) and take-home exams (26%) are the forms of examination that are most frequently used.

Embedded in the regulative discourse is the instructional discourse, which creates specialized skills and their relationship to each other. The result for the instructional part of the discourse is compiled in .

Table 3. The instructive discourse – content structures.

In the instructional part of the discourse, focusing on the content structure, it is subject didactics (theoretical and practical) that dominate (54%), where about a quarter (24%) of all the examination tasks focus on practical subject didactics. Tasks that examine subject knowledge (Quadrivium) are few (8%) and likewise the tasks in which the subject content can be defined as Trivium knowledge (14%).

Bernstein’s (Citation2003) analytical concepts of knowledge structures and the relating theoretical concepts of vertical and horizontal discourses have been employed to further analyze which form of knowledge is featured in the subject content of the pedagogic discourse. The results related to knowledge structures is presented in .

Table 4. The instructive discourse – knowledge structures.

With regard to the teacher education program, the two forms of knowledge (vertical and horizontal) can be seen as a dichotomy in which the horizontal knowledge structure is considered context dependent, based upon everyday concepts dealing with and rooted in practical classroom instruction. On the other hand, in order to develop a theoretically grounded knowledge base, vertical knowledge is needed, as it deals with scientifically generalized knowledge structures that can be used to develop in-depth knowledge of teaching and learning that reaches beyond the context of the classroom (Bernstein, Citation1999). In using Bernstein’s concept of instructional discourse to analyze the knowledge structures that are reflected in examination tasks, we find that tasks in which the re-contextualization principle used in the text is of a holistic character dominate substantially (93%). Moreover, these tasks are structured in a way that promotes the collective and brings about collaboration between students (66%). In half of the tasks (50%) students are required to relate established theories and knowledge (vertical knowledge) to their own experiences (personal and public). For a large number of tasks, however, the starting point is one’s own experiences only (40%) (personal), which can mean that the content becomes too closely tied to context and the individual student. Analytical abilities and/or the ability to problematize are not often part of the examinations (27%). Instead, the greater part of the tasks is normative or amounted to students describing their relation to the content. The normative starting point, together with the possibility of basing reflections upon one’s own experience and background, makes it difficult for teacher education students to gain knowledge and competencies with a vertical knowledge structure; instead we find horizontal, context-based knowledge and competencies dominating the examination practice.

The modality of the pedagogic discourse () is coded according to the concepts classification (C) and framing (F). In this case, classification refers to the distinction between different types of subject content where strong classification (C+) means that the examination task clearly articulates an aspect of the course or the subject that has delimited content. Framing, on the other hand, deals with the principle that controls processes of transmission and acquisition of knowledge. Framing relates to control over selection of subject content, the assessment criteria and communication criteria – that is to say, aspects not clearly related to the content of the tasks.

Based upon the compilation of the codes representing the modality of the pedagogic discourse, the result shows that most of the tasks (55%) have a weak (C−) or partially weak (C+-) classification (38%). This means that the tasks often test knowledge that integrates various subjects or content aspects. Framing (F) has been coded partly based upon the degree of control over subject content and the degree of clarity in the assessment criteria. Control over what subject content will comprise the basis for examination is often weak (F−) (45%) or relatively weak (F+-) (32%). This means that it is the student who decides what the content of the examination tasks will be. The degree of control over assessment criteria varies, however. More than half (53%) of the tasks have no, or very vague, assessment criteria (F−), while 39% of the tasks have clearly defined assessment criteria (F+). The control over principles of communication – that is to say, the format for the way the student accounts for his or her learning when doing the examination tasks – reveals that in many cases there is no, or a very weak, control of the format (F−) (49%), but approximately a quarter of the tasks (24%) contain control over principles of communication (F+), which can have to do with the length of the task and the way learning is accounted for, stipulations over font size, and other formalities ().

The factor analysis that was done using the statistics program SPSS was, as indicated above, an explorative factor analysis in which the extraction method, i.e. principal component analysis was used. Since there were ten factors with an eigenvalue of over 1.0, the number of factors was reduced to five, based partly on what the scree plot displayed regarding the factors’ eigenvalue, but also based upon the relevance of the factors and the dimensions that seemed plausible in relation to the empirical material. The five factors were rotated with the orthogonal rotation method Varimax, which resulted in a factor matrix that is presented in .

Table 5. Modality of the pedagogic discourse.

Table 6. Factor matrix.

In total, the five factors explain the 69.04% variance, Factor 1 explains 36.13%, Factor 2: 12.40%, Factor 3: 10.01%, Factor 4: 5.47% and Factor 5: 5.06% of variance. The five factors represent a pattern that can be seen in five dimensions, here described theoretically as different pedagogic discourses that are present in teacher education examination practice. These will be presented next.

Factor 1: general pedagogical knowledge – Trivium

The first factor represents a dimension that primarily focuses on the examination of Trivium knowledge. Examination tasks with this character are found almost only in educational science examinations and make up about 14% of the examinations. Despite the fact that these factors explain the greater part of the variance in the examination practice on the primary teacher education program, this practice is not dominant in terms of numbers.

The pedagogic discourse that this factor represents could be described as containing a regulative discourse that tells us that this is a form of examination that is conducted in seminars. In this form of examinations, language and linguistic skills are important tools for demonstrating knowledge, which means, using Bernstein’s analytical concepts, that this form of knowledge could be seen as a horizontal form of knowledge with a vertical structure.

The instructional discourse that represents the subject content examined belongs, as already mentioned above, to the Trivium. The knowledge structure asked for in the examinations is of an analysing problematizing character.

The way that the pedagogic discourse is transmitted through the analysis of examination tasks is described theoretically as the modality of discourse. To sum up this argument, one could say that classification reveals the relation between various aspects of content in the task and this factor combines tasks with different levels of classification. Framing, which indicates the degree of control, shows that the control over the content of the tasks is somewhat strong. Assessment criteria are also at times quite vague and at times clear and, finally, the criteria of communication are mostly vague.

Factor 2: teaching and self-reflection during placement

The second factor combines examinations that take place in connection with student teacher placement. These tasks made up about 6% of the examinations.

The instructional part of the pedagogic discourse, which the tasks in Factor 2 combine, is a content knowledge that is of a practical didactics or methodological nature – that is to say, a form of knowledge with a horizontal structure that is school-based and apprentice-like.

The regulative part of the discourse shows that knowledge is examined through students’ planning and carrying out classroom instruction within the framework of placement. The examined content is made up of student teaching (for example when a lecturer from the teacher education program visits and examines them) and often includes a self-reflection paper. The knowledge that is required to pass is often of a normative character and should be based upon the student’s own knowledge and experience. The tasks are therefore of a horizontal nature and are to a large degree context-dependent.

Normativity can in this case be viewed as the third component in the pedagogic discourse of the teacher education program, where an ideal view of teaching is communicated. The fact that students to a great extent can determine the content of the tasks gives the pedagogic discourse a weak framing while control of assessment criteria has strong framing, since it is clearly indicated what is to be achieved in order to pass the examination.

Factor 3: subject theory – Quadrivium

The third pedagogic discourse is characterized by a focus on Quadrivium-knowledge and is thus related to examination of subject knowledge that teachers are supposed to teach when they begin working as a teacher. This examination practice is not especially common; it only makes up less than a tenth (8%) of the total number of examination tasks.

The regulative part of the discourse shows that knowledge is examined, primarily in quizzes, web examinations and written university exams, but also by giving take-home exams. This type of examination is often carried out on an individual basis, which means that group tasks and other forms of group work are not common. In contrast to other categories, the knowledge that is tested is compartmentalized; that is to say, what is tested is atomized knowledge.

The instructional discourse is characterised by a focus on subject knowledge that teachers are supposed to teach when they begin working as a teacher. The tasks have a strong classification; that is to say, they deal with one delimited subject area at a time and thus with less content, and it is made very clear in which subject area the knowledge belongs. Framing is strong, in terms of communication criteria (form), selection of content and criteria of evaluation.

Factor 4: subject didactics

The fourth factors merge similar to Factor 3 aspects related to subject theory (Quadrivium), in this case to subject didactics that take place in the subject area and subject didactic parts of the program. This is the most common examination practice, 54% of the examination tasks were aimed for examinations of this subject area.

The regulative discourse evidenced written take-home exams as the most common form of examination. The instructional discourse contains both practical and theoretical knowledge, but also to a certain degree, subject knowledge.

Similar to Factor 2 this discourse contains knowledge that belongs in the third component of the pedagogic discourse of the teacher education program, a discourse that supports the didactic and methodological skills connected to the teaching profession. This form of knowledge can be seen as normative, where the student’s own views/skills are to be related to knowledge established in the literature (relatively normative and holistic in nature). Assessment criteria are weak; the tasks stretch across several areas of knowledge and have a low degree of framing, both in terms of communication criteria and subject content.

Factor 5: the unusual and vague tasks of Gestalt pedagogy

The last category reflects a pedagogic discourse that can be characterized as vague. Here we find tasks that deal with digital technology (ICT), Gestalt pedagogy and multimodality. The tasks are often in most cases holistic in nature and they have relatively weak classification, relatively clear assessment criteria, and strong formative control. The fifth factor cannot, be attributed to any particular part of the program.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to identify how the legitimate, professional knowledge base and professional identity are constructed in the most recent primary teacher education program, by analyzing what pedagogic discourses operate in the examination practice and what skills and competences are legitimized through these discourses. The result of our analysis of the primary teacher education program’s examination practice reveals that not only is there an increase in classification between the various teacher education programs, which the teacher education reform of 2011 implicated (Beach, Citation2011; Beach & Bagley, Citation2012; Sjöberg, Citation2011), but there are also practices that classify and separate content and practices within one and the same teacher education program, in this case, exemplified by the primary teacher education program.

The different parts of the primary teacher education program (educational science, subject knowledge and didactic skills and teacher placement) put a focus on various types of subject content. This is not so surprising. More interesting and startling is that the pedagogic discourses of examination practice in the different parts of the program differ so dramatically. Our study shows that certain examination practices are considerably more frequent than others, something that gives an increased legitimacy to the type of pedagogic discourse that those practices represent. The analysis reveals that the content of most examinations on the primary teacher program is testing subject didactic skills. The dominant examination practice participates in a pedagogic discourse that through factor analysis appears in Factors 2 and 4. This means that the knowledge that is assessed and that thereby forms a central part of what can be defined as the legitimate professional knowledge for primary school teachers is knowledge that is grounded in classroom practice and quite often in the student’s own experiences from the placement period, and which are described without any in-depth problematizing or analysis in the examination tasks. The pedagogic discourse is thus dominated by subject didactics and methods linked to the teacher’s work in the classroom. It is meant to provide a picture of the way an ideal classroom practice should be constructed (Ensor, Citation2004). The fact that students can many times choose what content will be examined is also problematic, since it is difficult to determine which subject didactic content the individual student has actually learnt. These parts of the program are also those that have the weakest content classification of the tasks, but also the weakest content control of all the skills and/or competencies that the students are supposed to present in their examination tasks. This examination practice is in this way similar to the Norwegian knowledge-based teacher education practice (Wågsås Afdal, Citation2012; Wågsås Afdal & Nerland, Citation2014) and displays a horizontal contextual knowledge structure (Bernstein, Citation1999).

In the educational science part of teacher education we find an entirely different examination practice that is not at all as dominant. This practice, represented by Factor 1, describes examinations in which vertical knowledge structures are tested and in which the students are expected to be able to analyze and problematize issues of the Trivium character. It is primarily in this examination culture that students learn about vertical research-based knowledge structures, giving future teachers the tools for questioning their own and others’ practices, but also to do a critical review and relate to policies/reforms that affect both the teacher’s teaching practice and their profession.

In the subject theory parts of the program (Factor 3), we observe yet another practice that differs dramatically from the other examination cultures and that is also an examination practice that is uncommon in the primary education program. The pedagogic discourse that we observe through this examination practice has content-based knowledge structures that can be seen as compartmentalized – in other words, examination tasks that require the student to atomize knowledge that is also strongly linked to the subject theory field in focus for examination. The discourse also has a strong classification of subject content. The modality of the pedagogic discourse further reveals a strong regulation of content and knowledge requirements as well as for form or aspects of communication (framing).

The reform of the teacher education program (SOU Citation2008:109; Prop Citation2009/10: 89) was grounded in harsh criticism of the teacher education program of the day and the changes to the program were driven by an ambition to lift the teaching profession, providing teachers with in-depth knowledge of their subject, but also more distinct subject didactics, method skills and competencies. The present teacher education program was also a clearly ideological reform (Beach & Bagley, Citation2012; Sjöberg, Citation2011). Based upon the results of this study, we assert that the fear that the teacher education program’s subject didactics and method content would be weakened was definitely not justified, since a large portion of the examination tasks on the teacher education program have a subject didactic character, in which methodological content are also common. The primary teacher students that pass the examinations at the university we have studied seem to be well prepared for handling everyday didactic classroom management. These skills are of course important for the teaching profession as well as for the single teacher. The results also indicate that students are prepared to meet and collaborate with colleagues at schools, since they have practiced their abilities to a large extent, often together with their fellow students, to discuss and formulate themselves on educational issues.

If this is the result of the most recent teacher education reform (SOU Citation2008:109) is impossible to know. Previous studies have shown how traditions and traditional discourses play a great role in pedagogic practice (Cf Beach et al., Citation2014). The pedagogic discourses, skills and competences found in this study are in any case, the legitimate professional knowledge in the primary teacher education examination practice under study.

In terms of content, knowledge and competencies that hereafter are in need of more focus, it is now subject theory knowledge, and primarily analytical skills that are needed to problematize phenomena, both in the classroom practice and outside of it. This means that the Swedish primary education program needs to develop and augment the Trivium-related parts of the program, but in addition it needs to change its focus with regard to subject didactic studies, from a normative approach to an analytical/problematizing one. In order to make this possible, what is required is not only changes made to the institutions that offer the teacher education program, but also an overview of the current national teacher education policy, which, as it is now constructed, forcefully locks in both the content and the organization of the teacher education program. We also need to further analyze and problematize the current teacher education policy’s underlying ideology. The developments that we see in our results otherwise risk augmenting the trend toward a teacher education program that is above all composed of teacher training (Beach & Bagley, Citation2013). This is something that we suggest should be in need for further studies. Without change, we argue that there is a risk that we face a future with teachers whose education has provided a horizontal knowledge base with practical skills, and worst of all: teachers who are incapable of problematizing, who know what to do in the classroom (know how), but do not have the ability to reflect upon why (know why) (Beach, Citation2011; cf Brante, Citation2010). This sort of teacher education program will not benefit the individual teacher and his or her professional identity, nor will it benefit the professionalization of teachers in general. Last but not least, and particularly in the long run, change would lead to a positive development in the outcomes of the Swedish school system, which was the most important goal of the teacher education reform.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The missing courses are the electives on the 4–6-programmme: physical education and art. For these courses, there were only syllabi and since the most important information for the content and results of the study is found in the other policy documents, these courses were left out of the study.

References

- Adoniou, M., & Gallagher, M. (2016). Professional standards for teachers – What are they good for? Oxford Review of Education, 43(1), 1–19.

- Alvunger, D. (2016). Vocational teachers taking the lead: VET teachers and the career services for teachers reform in Sweden. Nordic Journal Of Vocational Education And Training, 6, 32–52.

- Ball, S. J. (1993). What is policy? Texts, trajectories and toolboxes. Discourse Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 13(2), 10–17.

- Ball, S. J. (2008). The education debate. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Beach, D. (1995). Making sense of the problems of change: An ethnographic study of a teacher education reform. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothburgensis.

- Beach, D. (2011). Education science in Sweden: Promoting research for teacher education or weakening its scientific foundation? Education Inquiry, 2(2), 207–220.

- Beach, D., & Bagley, C. (2012). The weakening role of education studies and the re-traditionalisation of Swedish teacher education. Oxford Review of Education, 38(3), 287–303.

- Beach, D., & Bagley, C. (2013). Changing professional discourse in teacher education policy back towards a training paradigm: A comparative study. European Journal of Teacher Education, 36(4), 379–392.

- Beach, D., Bagley, C., Eriksson, A., & Player-Koro, C. (2014). Changing teacher education in Sweden: Using meta-ethnographic analysis to understand and describe policy making and educational changes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 44, 160–167.

- Berlak, A., & Berlak, H. (1981). Dilemmas of schooling: Teaching and social change. New York, NY: Methuen.

- Bernstein, B. (1999). Vertical and horizontal discourse: An essay. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2), 157–173.

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Bernstein, B. (2003). Class and pedagogies: Visible and invisible. In A. H. Halsey (Ed.), Education: Culture, economy and society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bernstein, B. (1990). Class, codes and control, vol. 4: The structuring of pedagogic discourse. London: Routledge.

- Börjesson, M. (2016). Från likvärdighet till marknad. En studie av offentligt och privat inflytande över skolans styrning i svensk utbildningspolitik 1969–1999 [From equity to markets: A study of public and private influence on school governance in Swedish education policy 1969–1999]. Örebro: Örebro studies in Education, Örebro university.

- Brante, T. (2010). Professional fields and truth regimes: In search of alternative approaches. Comparative Sociology, 9(6), 843–886.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Briant, E., & Doherty, C. (2012). Teacher educators mediating curricular reform: Anticipating the Australian curriculum. Teaching Education, 23(1), 51–69.

- Darling Hammond, L. (2010). Evaluating teacher effectiveness. Teacher performance assessments can measure and improve teaching. Center for American Progress.

- Darling Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world. What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 1–19.

- Ensor, P. (2004). Towards a sociology of teacher education. In J. Muller, B. Davies, & A. Morais (Eds.), Reading Bernstein, researching Bernstein. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Garm, N., & Karlsen, G. E. (2004). Teacher education reform in Europe: The case of Norway; trends and tensions in a global perspective. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(7), 731–744.

- Goldstein, D. (2014). The teacher wars: A history America’s most embattled profession. New York, NY: Random House.

- Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times: Teachers’ work and culture in the postmodern age. London: Cassel.

- Hattie, J. A. C. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Howitt, D., & Cramer, D. (2005). Introduction to statistics in psychology. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Jedemark, M. (2007). Lärarutbildningens olika undervisningspraktiker. En studie av lärarutbildares olika sätt att praktisera sitt professionella uppdrag. Lund: Lunds universitet.

- Kennedy, M. M. (1998). Learning to teach writing: Does teacher education make a difference? New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Kennedy, M. M. (2006). Knowledge and vision in teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 205–211.

- Klette, K., & Hammerness, K. (2016). Conceptual framework for analyzing qualities in teacher education: Looking at features of teacher education from an international perspective. Acta Didactica Norge, 10(2), 26–52.

- Nilsson Lindström, M., & Beach, D. (2015). Changes in teacher education in Sweden in the neo-liberal education age: Toward an occupation in itself or a profession for itself? Education Inquiry, 6(3), 241–258.

- Player-Koro, C. (2012). Reproducing traditional discourses of teaching and learning. Studies of mathematics and ICT in teaching and teacher education. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- Prop 2009/10:89. Bäst i klassen - en ny lärarutbildning [Top of the class - new teacher education programs]. Stockholm: Government offices of Sweden

- Sarakinioti, A., & Tsatsaroni, A. (2015). European education policy initiatives and teacher education curriculum reforms in Greece. Education Inquiry, 6(3), 259–288.

- Singh, P. (2002). Pedagogising knowledge: Bernstein’s theory of the pedagogic device. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23(4), 571–582.

- Singh, P., Thomas, S., & Harris, J. (2013). Recontextualising policy discourses: A Bernsteinian perspective on policy interpretation, translation, enactment. Journal of Education Policy, 28(4), 465–480.

- Sjöberg, L. (2011). Bäst i klassen? Lärare och elever i svenska och europeiska policytexter. [Top of the class? Teachers and students in Swedish and European policy texts.]. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothburgensis.

- SOU 1948:27. 1946 års skolkommissions betänkande med förslag till riktlinjer för det svenska skolväsendets utveckling. Stockholm: Ecklesiastikdepartementet.

- SOU 1952:33. Den första lärarhögskolan. Betänkande utgivet av 1946 års skolkommission. Stockholm: Ecklesiastikdepartementet.

- SOU 2008:109. En hållbar lärarutbildning. Betänkande av Utredningen om en ny lärarutbildning (HUT 07). Stockholm: Fritzes.

- Wågsås Afdal, H. (2012). Knowledge in teacher education curricula. Examining differences between a research-based program and a general professional program. Nordic Studies in Education, 3–4, 245–261.

- Wågsås Afdal, H., & Nerland, M. (2014). Does teacher education matter? An analysis of relations to knowledge among Norwegian and Finnish novice teachers. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(3), 281–299.

- Young, M. (2009). Education, globalisation and the ‘voice of knowledge’. Journal of Education and Work, 22(3), 193–204.