ABSTRACT

The aim is to describe special education teacher students’ learning in the field of tension between informal learning during day-to-day work and formal university education. From the theoretical framework of Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, we perceive the students as moving on a learning trajectory through a landscape of practice. The students visit some of the landscapes of practice and others they ignore. The students are rejected in some landscapes and in others they are welcomed. The students are experiences of identification as well as dis-identification. Quantitative data were generated from surveys with students at the beginning of their training, at the end of their studies, or after graduation. The results of the questionnaire indicate that the length of time the students spent at the university, affected their assessment of their learning during their training. To a small extent the students sought advice from their university teachers concerning teaching issues. The teachers played an important role in their formal learning, whilst their fellow-students and principals influenced the formal and informal learning. This generated a contextual learning highly important to the professional formation of the special education teachers. In the field of tension between formal and informal learning a community of practice appeared.

Introduction

In 2007, the Swedish government decided to reform special education teacher training at university level. Since then, there have been two parallel programmes in this area: special education teacher training (speciallärarutbildning), and special educators’ programme (specialpedagogutbildning).Footnote1 Since the reforms both are graduate education programmes, which means that they involve studies at an advanced level. Admission to both programmes requires an undergraduate qualification in education (mostly as teachers) and a certain amount of professional experience. Moreover, both programmes are supposed to secure students’ development in two ways, i.e. they are expected to guide students towards further development in academic and professional capacities. This is called a ‘dual progression’ (den dubbla progressionen) (Giota & Emanuelsson, Citation2011; Högskoleverkets rapportserie Citation2012:11 R, 2012; SOU Citation2008:109, 2008).

Table 1. Students’ attitudes towards the relations between formal and informal learning. The arithmetic value and standard deviation of statements with the highest approval.

This reform and the establishment of such programmes at graduate level raises several issues that require urgent investigation – at least from the perspective of those learning and teaching in such programmes, and the prospective clients of children at risk.Footnote2 The reform is still so recent that there is almost no research on this new form of teacher training, particularly regarding special education teacher training. Such research could, however, guide the further development of these advanced and complex programmes, which are unique in relation to our Nordic neighbours and most European countries, which provide all special education teacher/educator training as undergraduate education programmes.

Since 2010, there have been only 500–700 new special education teacher training students each year in Sweden (SCBFootnote3 2018). A state-financed professional development programme, to boost special education competences (speciallärarlyftet), has invested 100 million SEK in the education of a hoped-for 1000 extra new teachers between 2016 and 2019 across the country.Footnote4 However, state reports forecast a saturation of demand for special education teachers not before 2030 (SOU Citation2013:30).

Regarding the training of special education teachers, two interesting phenomena are apparent that complicate understanding of the development of this group even more: (1) Due to the expectations for the state to increase special educational support in schools the vast majority of these teachers are already working with children at risk. In short, it could be said that they already working as special education teachers, although they lack formal training or certification as such. Regarding UKÄ (2015), 50% of all working special education students are not graduates.Footnote5 (2) In order to be allowed to participate in the graduate programme, students need to have a prior education in a school/preschool-related field. Most of them have a subject teacher education at undergraduate level and at least three years’ work experience as teachers. Consequently, special education teacher students often have a developed teacher identity when they start their education.Footnote6

In Swedish schools, there is a large shortfall of teachers – particularly special education teachers. (SOU Citation2013:30, 2013).Footnote7 To address this recruitment of students for teacher education, particularly special education, has to increase at universities across the country. The tremendous need for special education teachers relates to the government’s desire to create an inclusive school for all – regardless of different levels and needs. Special educators are expected to create learning environments that make this possible.

Malmgren Hansen (Citation2002) draws attention to research on students transitions from the special educators’ programme to professional special educators in Sweden. According to the research special educators experience obvious difficulties in maintaining their new professional position in the dominant school-culture. According to Malmgren Hansen (Citation2002) ‘Often they feel that teachers tell them what to do with pupils, pupils that these teachers themselves cannot or do not want to deal with in an educational situation. The schools often demand that the 13Footnote8 act as emergency personnel even if the task to be dealt with does not require a special educator’ (p. 173). The opinion of the teachers, in Malmgren Hansen (Citation2002), exposes the gap between inclusion policy and implementation. Lindqvist (Citation2013) confirms this result asserting that the gap is caused by school leaders’ different interpretations of and ambivalence to inclusion and their expectations of special educators to become coordinators rather than teachers who teach.

By analysing professional development and course delivery, field experience and mentoring induction, and performance-based assessment, Dukes et al. (Citation2014) and Darling et al. (Citation2016) try to identify a core principle of special education. The education of special educators needs to be continually adapted to changes in the real world. To make this possible, there has to be a coherent idea that can be implemented. It is necessary to understand special education teachers and special educators as professionals who develop practices and arguments about the inclusion of students at risk (Bartonek et al. Citation2018; Vetenskapsrådet, Citation2017). The special educators’ profession develops in the field of tension between academic special education and professional decision-making in a day-to-day professional work. Here emerge an ongoing sharing of experiences and knowledge between university and workplace. There is a sharing of individuals’ previous and present teaching experiences. To some extent special education teacher training appears to be an arena for sharing research, knowledge, skills and practices. By comparing the experiences of this tension of students at the beginning and at the end of their training or after graduation, this paper aims to describe these students’ learning in the field of tension between informal learning and formal graduate education at university. To understand the professional formation of a special education teacher, the field of tension of the academic special education and professional decision making needs to be investigated.

Swedish special education teachers: a back and forth exchange

The first programme of education for special education teachers in Sweden was established in 1960s. It was a one-year supplementary special education teacher training at Stockholm university and university of Gothenburg (Högskoleverkets rapportserie 2012:11 R, Citation2012). Several political decisions since the 1980s have had implications for special education teachers and their professional identity. In the late 1980s the Swedish parliament decided to phase out special education training (prop.Footnote9 1988/1989:4; 1988/89 UbUFootnote107). In the 1990s it was replaced by a special educators’ programme, which included 2–3 semesters with the possibility of continual training. The aim was to develop the teachers understanding of students in complicated learning situations, deaf students, visually impaired students and students with intellectual disabilities (Regeringens proposition 1988/89:4).

The so-called learnification wave, during the reforms in the 90s, shifted the focus from instruction and teaching to learning and learning environments (Biesta, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Following the discourse of this time, special education teachers where replaced by special educators whose focus was not instruction but collegial guidance focussing on the development of the learning environments for children at risk (Giota & Emanuelsson, Citation2011; Högskoleverkets rapportserie 2012:11 R, Citation2012; SOU Citation2008:109, 2008).

In 2006 The Swedish National Agency for Higher Education sharply criticized the special educators’ programme (Högskoleverkets rapportserie 2006:10 R, Citation2006) citing a lack of professional competence and supervisory capacity. In 2007, the Swedish government decided to replace the special education teacher training resulting in a new advanced level education programme in 2008 (SOU Citation2013:30, 2013). With the recent reforms, the role of the teaching and instruction as the core of schooling has been strengthened again.

This historical oscillation between special education teachers and special educators is not surprisingly because both have the same function that constitutes the existence of the profession as such. It is inclusion, either from a holistic organizational perspective (special educators) or instructional perspective (special education teachers). However, the differing terminology have probably contributed to practical insecurities of what the tasks of both of the special education groups are (Lindqvist, Citation2013). Consequently, we might even assume that what is ‘practice’ for special education teachers might differ in the schools.

Supplementary special teacher training as a community of practice

Teachers have the opportunity to engage in open sharing with one another. A supplementary education focuses on learning – both in and from practice. It concentrates on the combination of knowledge of teaching, knowledge of subject and knowledge of particular groups of students. The education provides possibilities to improve student learning and enhance professional learning among teachers. Within supplementary education, a collective consciousness can also be generated. There are several reasons to argue for supplementary education as a Community of Practice (CoP), which relates to teachers as professionals oriented towards teachers’ professional development and learning. The CoP enables teachers to work from an inquiry stance and allows them to solve problems, construct knowledge and possibly form and re-form frameworks for understanding their teaching practice.

In a CoP, students have the possibility to negotiate meanings and implications of, for example, their supplementary training. Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) stress that the CoP does not primarily refer to a limited group of people but to a negotiating process. In such a process there is formal education and informal learning. Thus, there are possibilities to create a CoP including university education, employers and students.

Theoretical perspective

In order to understand the professional formation of a special education teacher, we employ the theoretical perspective of Etienne and Beverly Wenger-Trainer (Wenger-Trayner et al., Citation2015) regarding learning landscapes of practice. This perspective further develops Wenger’s (Citation1998) concept of community of practice in which professional learning take place in a social practice.

Professional learning in a community of practice

The central theme of Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) is the understanding of learning as the ‘trajectory into a community’. In contrast to formalized learning, getting involved in the CoP facilitates and makes learning possible. People who share interests and challenges, who learn with and from each other may belong to a CoP – a self-governing learning partnership. To quote Wenger et al. (Citation2002): ‘Community of practice are groups of people who share a concern, set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis’ (p. 4). Wenger (Citation1998) stresses that a CoP exists when mutually engaged individuals over time and in a joint enterprise, develop a shared repertoire of ways of doing things. The CoP can also be a useful framework in guiding teachers’ professional development.

Initially, the domain is a motivation for people sharing concerns and a knowledge base from which they make choices to work. The domain ensures the relevance of the CoP and keeps it focused. From their shared engagement in the domain arises the members’ commitment to learn together (Wenger, Citation2006). According to Wenger (Citation1998) while the domain is the CoP’s establishment, the community is the sustainment of the CoP. The community is intended to ensure the members’ participation and cooperation. From the concerns that participants have for their domain arises the community’s commitments to share and learn. Whilst a team can work on a task and then disperse, the community will still remain and its learning experiences can deepen over time. Whereas a domain brings the members together and the community sustains their learning, the practice crystallizes their shared knowledge and experiences. The CoP develops a collective identity and an individual practice. Members develop ‘a shared repertoire of resources: experiences, stories, tools, ways of addressing recurring problems – in short a shared practice’ (Wenger, Citation2012b, p. 2).

The defining characteristics of domain, community and practice are linked in the creation of a dynamic learning community. If anyone characteristic is not in balance, there is a risk the overall function of CoP will be threatened. If a domain is too ill defined or too broad, members might not share enough to create the engagement they need.

Learning in landscapes of practice

Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) discern our learning experiences as a journey through a landscape which creates how we experience ourselves. ‘If a body of knowledge is a landscape of practice (LoP), then our personal experience of learning can be thought of as a journey through this landscape’ (Wenger-Trayner et al., Citation2015, p. 19).

According to Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) the LoP establishes ‘a social body of knowledge’ (p. 15). To understand how it occurs it is important to consider some features. The landscape is political. ‘A landscape consists of competing voices and competing claims to knowledge, including voices that are silenced by the claim to knowledge of others’ (p. 16). There also is a locality in a landscape where the practices also have their own regimes of competence and internal logic. Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) explain that it depends on the creation of a community that engages in it. The landscape thus constitutes the experiences of ourselves, through the journey we do. It constitutes the experiences of people, regimes of competence, communities and boundaries. Created by the journey the identities embody the landscape through the different experiences we get.

To describe how we build our identities in a LoP, we need to distinguish between some identifications. Engagement make possible an immediate relation to the LoP – we talk, do things and work on issues. We create images when we journey through the landscape we inhabit and the images are necessary to our interpretation of the participation. However, without some degree of alignment our engagement is rarely effective. Alignment with the context is important, otherwise the engagement in practice is uncommon. Engagement, imagination and alignment are possibilities to make sense of the landscape as well as our position in it.

It is possible to actively belong to a few practices. Boundaries of practice are unavoidable but in different ways the boundaries challenge practice-based education. The boundaries between educational settings and work is a first expression. Secondly, there are boundaries within the academic disciplines. Finally, there are boundaries in the students’ landscape, among workplaces and the practices of the students’ clients. The journey shapes different relationships and position in the landscape of practices. We do not fully enter all the practices some of them we visit, others we ignore. We identify with a few in a strong way. In some communities we are rejected, in others we are welcomed. Along the journey, there are experiences of identification as well as disidentification. It is a changeable and dynamic landscape we take part in. New communities arise while others disappear. Occasionally they merge or split. Sometimes CoP complement each other and sometimes they compete. In the landscape of competition, claims to knowledge sometimes are silenced. Consequently, there emerge knowledge hierarchies among practices. Following Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) ‘there is no guarantee that a successful claim to competence inside a community will translate into a claim to “knowledge” beyond the community where it is effective’ (p. 16). The position in the politics of the landscape decides if the competence of will be recognized as knowledge.

In contrast to the competence that describes a dimension of knowing which is negotiated in the single CoP, the knowledgeability accounts for a complicated relationship constituted across the landscape of practice. It seems impossible to be competent in all practices within a landscape but according to Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) we can be knowledgeable about their importance to our own practice and location in the broader landscape. To become a practitioner, we develop an identity of competence and knowledgeability whereas we use competence to describe the dimension of knowing negotiated and defined within a single CoP, knowledgeability manifests in a person’s relations to a multiplicity of practices across the landscape. According to Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) it is not possible for anyone to be competent in all the practices in the landscape, but it is possible to be knowledgeable about ‘their relevance to our practice, and thus our location in the broader landscape. When considering an entire landscape, claims to knowledgeability are an important aspect of learning as a social process’ (Wenger-Trayner et al., Citation2015, p. 19).

Taking knowledgeability seriously suggests new possibilities for conceptualization employability. If we move from focusing solely on producing discipline-specific competence to supporting students in developing competence and knowledgeability across the landscape of practice, different concerns and challenges emerge. These include reflecting on the location of academic practices in the landscape, a focus on the development of workplace identities, the appropriate modulation of identity between settings, and sensitivity to differences in the ways in which competence is judged in different settings. Such a perspective also suggests the value of approaches to employability that develop the relationship of engagement, imagination and alignment with key practices in relevant landscape of practice.

Regarding the analytical perspective we understand the future of special education teachers as learning trajectories within a landscape of practice. The trajectory is characterized by boundary crossing and identity work between different CoP that constitute the landscape.

For the students, significant CoP are teachers, special education teachers and the universities – the latter mostly meaning the academic discipline of special education, which due to its multi-disciplinarity might consist of several CoP. Different communities are characterized by particular regimes of knowledge, which have different values. The prospective special education teacher, being a traveller through such a LoP, is differently accountable to various CoP. Moreover, one community might be left behind, another only passed by the student (E.g. it might be argued that the students only ‘pass by’ a virtual university CoP, but never become a member in it.).

Research design

The special education teachers’ graduate programme is three full terms or 1 1/2 years (advanced level). In the first and third full terms of the training students attend courses together, learning about research within the field of special education and about scientific methods. In the second full term, the students attend courses tailor-made to their specialization such as professional competences in ‘language, reading and writing development’, ‘deafness or hearing impairment’ ‘students with intellectual disability’, ‘specialization in visual impairment’ and in ‘mathematical development’. At Stockholm University the special education teacher training is given as part-time, expect the course on language, reading and writing development, which is given as part-time and full-time.

Johanna Dahlberg Larsson designed the questionnaire using a deductive approach and collected and processed the quantitative data (Dahlberg Larsson, Citation2018). The survey was delivered by email to all special education teacher training students (188 in total) at Stockholm University during spring 2018. Due to the web-based nature of survey the participants had the possibility to choose where and when they wanted to answer the questionnaire. The reason for addressing the questionnaire to all students, regardless of how far they were from graduation was the effects the time aspect has to the students’ learning. Some of the students were studying full-time and others part-time. Thus, the final term was the sixth for part-time students and the third for full-time students. Eighty-nine students (47%) completed the questionnaire with the internal loss reaching a peak of over 6% (N = 83). The quantitative data were described by univariate analyses (included alpha) – some of which considered that some of the respondents were at the beginning of their education and others that they were at the end. The majority of questions were pre-determined and multiple choice. A Likert scale was used with four answer options.

It is not possible to generalize from the data collection, in a broader sense but generalization is not a primary concern. In comparison with universal interests intended to predict, the particular here plays a major role.

Results

According to the results the more time the students spend in the special education teacher training, the more their assessment of their own learning is influenced by the time they spent in the education. Consequently, there are differences between students in term 1–3 in comparison to term 4–6. The questionnaire questions were about formal education and informal learning, learning and the importance of time, and at least the importance of other people to their own learning.

Formal education and informal learning

According to the students attitudes in , special education teacher training taking seriously students’ experiences from the teaching practice (mean 3,13). To a large extent the teacher students agree that the education made it possible to learn from theories (mean 3,19) and to anchor them into practice (mean 3,7). The standard deviation indicates the students had a similar response rate and the results express rather high mean values revealing students’ way of talking about learning as meaningful. It proceeds from meaning – one of the components of learning Wenger (Citation1998) defines. Following Wenger (Citation1998) negotiation is a core aspect and a process where meaning is located. The process is constituted by different elements which it also affects. One effect will be a changeable situation in which negotiation creates meaning. The ongoing process constantly generates circumstances for more negotiations and further meanings. The meaningful learning among the students changes all the time by negotiation of meaning of their experiences from teaching practice, learning theories and the anchoring of theories in teaching practice.

Learning and the importance of time

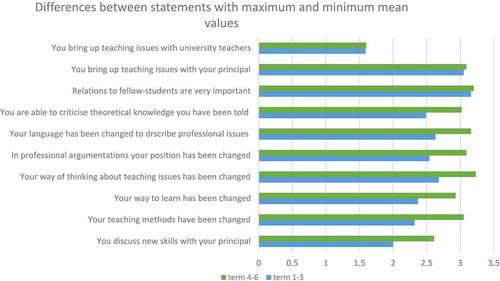

The survey indicates that the students’ learning is highly influenced by the length of time they participated in the special education teacher training. The comparisons below detail the differences between term 1–3 and 4–6. The final term is either the third or sixth depending on whether the student is a full-time or part-time student. The standard deviation indicates that the student groups are homogeneous in the response rate, on account of low standard deviations. illustrates the differences between statements with maximum and minimum mean values. The students estimated statements about their own learning in relation to surrounding people. Further, the students made decisions about statements in term of how their learning had changed during their university studies. Finally, the students were asked how they acted when failing to help pupils in their learning development. When comparing students in terms 1–3 with those in terms 4–6, the latter group agreed more often with all statements in .

Figure 1. Differences between statements with maximum and minimum mean values. A comparison between students following the special education teacher training term 1–3 and 4–6.

As mentioned before, the questionnaire indicates that the length of time at university affects the students’ way of answering the questions – the more time they spend in the training, the more they agree to the statements in the survey. The most significant difference between mean values relates to the statement ‘Your learning methods have been changed’ (dif. mean,73). It indicates the students’ requisites of time to change their teaching. This result agrees with Wenger (Citation1998) who assert that the adaption of teaching design is necessary to get involved in a teacher community sharing teaching experiences, solving problems and sharing conceptions of the world. This kind of change was expressed when the part-time students (term 4–6) agreed with all statements to a higher extent than the full-time students (term 1–3). The big differences in mean values also reflect the changes., i.e. relating to the statements ‘your way to learn has been changed’ (dif. mean,57), ‘your way of thinking about teaching issues has been changed’ (dif. mean,55), and ‘your language has been changed to describe professional issues’ (dif. mean,53).

The time-aspect seems not to be important in statements with small differences between mean values such as ‘You bring up teaching issues with the school-leaders’ (dif. mean,4), ‘Relations with fellow-students are very important’ (dif. mean, 4), and ‘You bring up teaching issues with your university teachers’ (dif. mean,1).

Learning and the importance of others

In the section ‘formal and informal learning’ the students indicated teacher training paid attention to their experiences from the teaching practice, and they stressed the importance of the education in learning from theories and anchor them into practice. They also emphasized the importance of principals and fellow-students over university teachers when addressing concerns about their teaching practice.

The students created learning in interplay with others bringing up teaching issues with principals and in discussions with fellow-students. The students shared educational problems and found solutions of them in cooperation with each other. It was acceptable to fail and they felt comfortable with each other. These characteristics were crucial in their learning. According to Wenger et al. (Citation2002) this is an expression of an informal hub for the participants in a CoP. The importance of fellowship is not just in solving problems but is a question of sharing perspectives and meeting equals.

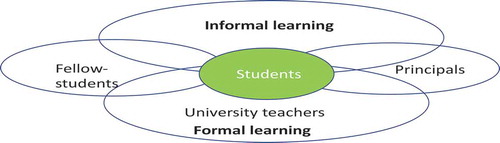

Figure 2. Special education teacher students in the landscape of practice. The students belong to different communities of practice: fellow-students in informal and formal learning, principals in informal and formal learning, university teachers in formal learning in education.

A further aspect Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) highlight is that individuals can belong to several CoP at the same time (cf. ). The fact that students learned from each other, indicates that they are participating in a network of CoP. Thus, fellow-students contributed to development of professional knowledge which made the gap between formal learning in education and informal learning in practice possible to bridge. The relationship between the prospective teachers and other students were neither formal nor informal but generated a contextual learning. According to Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) such a learning is highly important to professional development. Students in CoP benefit from the boundaries between them to develop the special education teachers’ learning and profession.

Discussion

In this paper it has been shown that future special education teachers develop their learning in the field of tension between formal learning during the supplementary training and informal learning in practice. They share interests and challenges, learning with and from each other. The more time they spend in special education teacher training, the more their ways of learning change. According to the results there are few differences between term 1–3 and term 4–6 concerning the importance of university teachers and fellow-students. Throughout the education fellow-students are very important for the students’ learning. As regards practice-oriented issues it concerns fellow-students. In a small extent, students seek advice from their university teachers concerning teaching issues related to the teaching practice. And university teachers are crucial to the formal learning, whilst fellow-students and principals influence the formal as well as the informal learning. These relationships create a contextual learning central to the professional formation of special education teachers. In the field of tension between formal and informal learning a CoP emerges.

The tension between formal education and informal learning gives students to putting into words their changing ability to experience real life as meaningful. The participants in the study consider the most important of the education to be the combination of these two different areas. The supplementary education makes it possible to take part in the formal education at university as well as the informal learning in practice. During the education the students change how they discuss problems related to the profession. They attain a professional language and thereby they develop a community important for their teaching at school.

The special education teacher students’ learning indicates that they are getting involved in a CoP. They share concerns and challenges, learn with and from each other. In the CoP they develop their skills, knowledge and professional identity by interacting on an ongoing basis. In the CoP the future special education teachers are mutual engaged during their education.

As mentioned before, Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) discern our learning experiences as a journey through a landscape, which creates how we experience ourselves.

The landscape constitutes the experiences of the special education teacher students, through the journey they do. According to Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) in the landscape of practices the journey creates different relationships and positions. The special education teacher students seem not to reject any practices. They rather are visitors in different ones. And they give the impression of being strongly identified in the community of fellow-students, as well as the community of principals. They give the future special education teachers possibilities to cross boundaries between informal learning and formal education. The special education teacher students’ identification with the fellow-students and principals appears to be clear. There are no differences between the importance of fellow-students and principals during the education or after the graduation. Always they are crucial to the students’ way of talking about their abilities to experience the special education as meaningful.

In the community of university teachers, the special education teacher students seem to be welcomed. The students themselves, in some senses, they ignore the university teachers when it comes to issues related to the teaching practice. But they welcome the university teachers when it comes to the formal education.

As mentioned before, according to Wenger-Trayner et al. (Citation2015) it is not possible for anyone to be competent in all the practices in the landscape, but it is possible to be knowledgeable about them. For the students, significant CoP are fellow-students, principals and university teachers. For the students, the latter mostly means the academic discipline of special education, which due to its multi-disciplinarity might consist of several CoP. Different communities are characterized by particular regimes of knowledge, which have different values. The intended special education teachers, beeing travellers through such a landscape of practice, are differently accountable to various CoP. Moreover, one community might be left behind, another only passed by the student (E.g. it might be argued that the students only pass by a virtual university CoP, but never become members in it.) The trajectory of learning results in a particular shared identity of students, which is constituted by knowledgeability of the landscape, particular networks, professionalism and of kinship, building on shared knowledge and also emotions related to similar learning trajectories and boundary crossing.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the reserch, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1. For the English names of the programmes in focus, we will use the official English translations of Stockholm University. Regarding the difference between both programmes, the profession of ‘special education teachers’ was abolished in the 1990s with the introduction of the special educators’ programme. This meant a shift in focus from instruction and teaching to learning and learning environments. Special education teachers where replaced by special educators. The focus of the latter group was not instruction but collegial guidance focussing on the development of learning environments for children at risk. With the recent reforms, the role of the teacher and instruction as the core of schooling was strengthened again.

2. In this project we translate the Swedish phrase barn i behov av särskilt stöd (b.a.s.s.) as children at risk.

3. Statistics Sweden.

5. https://www.uka.se/om-oss/aktuellt/nyheter/2015-9-14-forandrad-utbildning-kan-losa-bristen-pa-speciallarare.html (26/3/2019).

6. This is common knowledge in programmes throughout the country. There is no systematic evidence for how these teachers are chosen to start the graduate prograamme.

7. Official Reports of the Swedish Government.

8. Thirteen special educators participated in the study.

9. proposition.

10. The Committee on Education.

References

- Bartonek, F., Borg, A., Hammar, M., Berggren, S., & Bölte, S. (2018). Inkluderingsarbete fö r barn och ungdomar vid svenska skolor. Stockholm: Karolinska institutet. [KI – A Medical University: Inclusion efforts for children and youths in Swedish schools]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2015a). Freeing teaching from learning: Opening up existential possibilities in educational relationships. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 34(3), 229–243. doi:10.1007/s11217-014-9454-z

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2015b). What is education for? On good education, teacher judgement and educational professionalism. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12109

- Dahlberg Larsson, J. (2018). Lärande i påbyggnadsutbildning: Symbiosen mellan utbildning under längre tid och lärande i arbetslivet (Bach.) [Learning in supplementary education: Working life in symbiosis with learning for a long while]. Uppsala universitet.

- Darling, S. M., Dukes, C., & Hall, K. (2016). What unites us all: Establishing special education teacher education universals. Teacher Education and Special Education, 39(3), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406416650729

- Dukes, C., Darling, S. M., & Doan, K. (2014). Selection pressures on special education teacher preparation. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406413513273

- Giota, J., & Emanuelsson, I. (2011). Specialpedagogiskt stöd, till vem och hur? Rektorers hantering av policyfrågor kring stödet i kommunala och fristående skolor [Support strategies, for whom and how? Exploration of how headteachers in community ruled and free schools describe handling procedures of special education issues in their schools]. (RIPS: Rapporter från institutionen för pedagogik och specialpedagogik, nr 1). Göteborgs universitet.

- Högskoleverkets rapportserie 2006:10 R. (2006). Utvärdering av specialpedagogprogrammet vid svenska universitet och högskolor. [Swedish Council of Higher Education: Assessment of special educators’ program at Swedish universities and university collages]. https://gu.se/digitalAssets/1281/1281969_utvardering_specialpedagogprogrammet.pdf

- Högskoleverkets rapportserie 2012:11 R. (2012). Behovet av en särskild specialpedagogexamen och specialpedagogisk kompetens i den svenska skolan. [Swedish Council of Higher Education: The requirement of a graduate education programme and special education competence in the Swedish school system]. http://www.uka.se/download/18.12f25798156a345894e2b95/1487841883074/1211R-specialpedagogexamen-svenska-skolan.pdf

- Lindqvist, G. (2013). Who should do what to whom? Occupational groups’ views on special needs. Jönköping University.

- Malmgren Hansen, A. (2002). Specialpedagoger – Nybyggare i skolan [Special educators – pioneers in school]. Diss. Stockholm: Univ.

- Regeringens proposition 1988/89:4 (1989). Om skolans utveckling och styrning [Governmental proposition: School development and governance]. https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/6F74CCF7-C44B-475F-ADFA-6197D4BE7D8F

- SOU 2008:109 (2008). En hållbar lärarutbildning. Betänkande av utredningen om en ny lärarutbildning (HUT 7) [Official Report from the Swedish Government: Sustainable teacher education. Proposal from the commission of a new teacher education]. https://www.regeringen.se/49b71b/contentassets/d262d32331a54278b34861c44df8dbad/en-hallbar-lararutbildning-hela-dokumentet-sou-2008109

- SOU 2013:30. (2013). Det tar tid – om effekter av skolpolitiska reformer. Delbetänkande av utredningen om förbättrade resultat i grundskolan [Official Report from the Swedish Government: It will take time – effects of school political reforms]. http://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/5d0adf0f94d4bd3a6f0be062fdb6b08/det-tar-tid—om-effekter-av-skolpolitiska-reformer-sou-201330.

- Utbildningsutskottets betänkande: 1988/89:UbU7. 1988/1989. Skolans utveckling och styrning [Committee proposal: School development and governance]. https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/C03DAFB8-9D2A-493B-80F4-DB08FC87A79E

- Vetenskapsrådet. (2017). Tre forskningsöversikter inom området specialpedagogik/inkludering [Swedish Research Council: Special education/inclusion – Three research reviews].

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E. (2006). Communities of practice: A brief introduction. https://www.academia.edu/6189864/Communities_of_Practice_A_Brief_Introduction

- Wenger, E. (2012). Communities of Practice: A brief introduction. http://wenger-trayner.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/1/6-Brief-introduction-to-communities-of-practice.pdf

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard University Press.

- Wenger-Trayner, B., Wenger-Trayner, E., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Hutchinson, S., & Kubiak, C. (2015). Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity, and knowledgeability in practice-based learning. Routledge.