ABSTRACT

In this paper, we theorize on local school governance through a multi-method case study of a large-sized Swedish municipality by drawing on neo-institutional theory. In light of a changing governing landscape in Sweden in terms of a ‘re-centralization’, new conditions between the state, the local education authorities (LEA) and the schools have emerged. The aim of this study is to examine what policy actions the LEA employ for governing the school and in what ways that principals respond and handle these policy actions. The results point to the fact that the LEA uses a bench-marking strategy through its quality assurance system and intervene if results are poor. Principals seek support from the LEA, but are anxious that their autonomy will be diminished and therefore function as ‘gate-. The system for quality assurance is appreciated by principals, but standards aimed at framing discursive communication on quality are criticized. Principals turn to managers below the superintendent, which creates a tension between managers. The study shows that different levels and actors must be taken into account in order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the multi-layered field of local policy enactment.

In recent decades, there has been a growing body of research that highlights local education authorities (LEAs) and school districts as key players in education reforms (Anderson & Daly, Citation2013; Rorrer et al., Citation2008; Seashore Louis, Citation2013; Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2017), but there is a need of further research on education governance and policy actions at the intermediate local level within national education systems. Policy researchers have emphasized how national and local policy is influenced by transnational policy through supra-national organizations, such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) or the European Union (Grek et al., Citation2009; Lawn & Lingard, Citation2002), and called for a perspective on the local space in which globalization takes place within a sub-national domain (Robertson & Dale, Citation2015; Sassen, Citation2006). In this respect, global trends towards stronger state regulation in terms of input and output on curriculum policy (Alvunger, Citation2018; Leat et al., Citation2013; Nieveen & Kuiper, Citation2012) and the expansion of accountability and performance-based systems (Leat, Citation2014; Hamilton et al., Citation2008; Yates & Collins, Citation2010) have come to shape conditions for local school governance.

While there traditionally has been a focus on national level and school level regarding the impact of reforms, the expanding research field has helped to increase our understanding of education governance and policy actions at the intermediate local level within national education systems. In a Swedish context, the trends of increased input and output regulation and the growing importance of accountability systems have had a particular influence on the relationship between the state and the LEAs since the dawn of the new millenia. Even if ideas of a decentralized school system grew strong already in the 1970 s, it was not until the end of the 1980 s that reforms reshaping the centralized school system were put into play. In a matter of years, reforms led to a decentralization with municipal authority over the schools and the introduction of a new goal- and outcome-based quality system to ensure equality in education. The introduction of a competency-based curriculum in 1994 reinforced the local professional autonomy of the schools in the municipalities (Lindensjö & Lundgren, Citation2014; Nordholm, Citation2016). Declining student achievement after 2000 led to policymakers becoming more informed about policy solutions provided by the OECD (Forsberg & Lundahl, Citation2012; Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2017), and the notion of a school system in a state of crisis grew. This triggered a trend of recentralization, where the state seeks to control the schools’ outcomes at the expense of the local authorities’ room for action (Adolfsson, Citation2013; Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2017).

During the first decades of the new millennium, the government introduced several reforms and incentives that involved the local management of schools: the Swedish School Inspectorate in 2008 to audit and monitor schools, a reformed Education Act in 2010 emphasizing the local authority’s responsibility for equity and student achievement and strengthening the principals’ authority, professional development programmes, a new national curriculum in 2011 for compulsory and upper secondary schooling, and new specialist functions (e.g. expert teachers) in schools in 2013 (Adolfsson & Alvunger, Citation2017; Alvunger, Citation2015). An important aspect of the trend of recentralization is how national policy is communicated. Wahlström and Sundberg (Citation2017) argued that the Swedish National Agency for Education (NAE) was very active in informing schools how the reform should be implemented. The LEAs were efficient in coordinating policy messages from the government in terms of equality of assessment and grading, the focus on the subject matter and the importance of systematic quality assurance. In this respect, rather than merely interpreting the reform, the LEAs enacted it. However, LEAs did not seem to understand the main pedagogical aims of the reform and how resource distribution should be resolved (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2017).

Due to its decentralized structure, the Swedish school system is characterized by both horizontal and vertical structures of responsibility, depending on the size of the local school organization. According to the Education Act (SFS, Citation2010:800), a school must be managed and coordinated by the principal. The principal acts as an educational leader and is responsible for working in accordance with and evaluating results in line with national goals. The LEA is held accountable for ensuring that education is aligned with the national goals as well as legal requirements and ordinances involving the schools. The superintendent has the operational responsibility for leading principals and for resource distribution to provide equity and the achievement of the national goals of education.

Against the backdrop of recentralization, new governing conditions between the LEA and principals have emerged. In this paper, we use this dynamic – with its tensions, pressures, and frictions – as our vantage point and direct our focus towards LEAs and principals as local policy actors within the context of a large Swedish municipality. The aim is to explore and theorize on local school governance by drawing from Scott’s (Citation2008) three institutional pillars for explaining the relationships between the school as institution and the social organizations comprising this system – the regulative, the normative and the cultural-cognitive pillars – and Powell and DiMaggio (Citation1991) concept of isomorphism to answer the following research questions:

What policy actions does the LEA employ for governing the schools in the municipality?

In what ways do principals respond to policy actions from the state and from the LEA?

How can a theoretical understanding of the dynamic interplay of policy actions between the LEA and principals in the complex and multi-layered field of local policy enactment be advanced through concepts of institutional change, legitimacy, and isomorphism?

LEAs as policy actors

From a historical perspective, research on districts and LEAs has been sparse compared to the interest given to large-scale national reforms or how reforms and interventions are played out at the local school level (Finnigan et al., Citation2013; Rorrer et al., Citation2008). However, previous research on systemic reform at the district level (Smith & O’Day, Citation1991; Spillane, Citation1996) showed that the particularities of local contexts are important for understanding the implementation of national education policy and school development programs (Adolfsson & Alvunger, Citation2017; Cuban, Citation1998; Dumont et al., Citation2010; Fullan, Citation2000; Hopkins et al., Citation2014; Resnick, Citation2010).

In their research review on districts, Rorrer et al. (Citation2008) identified four major and interdependent roles and processes that districts play in educational reform. First, district authorities offer instructional leadership (e.g. through capacity building) and help to build commitment for pursuing change in the organization. Related to this is the second role: to model and align interventions and initiatives for changing the direction of the organization. This includes both structural and cultural elements to ‘refine organizational structures and processes and alter district culture to align with their educational reform goals’ (Rorrer et al., Citation2008, p. 318). Thirdly, districts take on a brokering role in intermediating and communicating state-level policy, ensuring policy coherence through different layers of the organization. Resource distribution is an important aspect of this intermittent role and constitutes the backbone of the fourth role, namely to help maintain a focus on equity. According to Rorrer et al. (Citation2008), districts emphasize increased equity as a future mission, and they take responsibility for dealing with past inequalities.

The question about equity at the local level is closely connected to how LEAs respond to and operate from test-based accountability systems and performance measures for increased achievement. An illustrative example is how districts in the USA changed their practices for measurement and testing when adopting new systems for accountability after the passing of the No Child Left Behind Act (Hamilton et al., Citation2013). Hamilton et al. (Citation2008) and Hamilton et al. (Citation2013) claimed that traditional forms of governance in the districts were challenged and that tensions arose between the districts and the local schools resulting in unclear accountability and authority for interventions. Similar tensions in the Swiss local school governance system were reported by Huber (Citation2011) when principals were introduced as operative heads over schools. The professionalization of instructional leadership and a system of school inspections put the former governing bodies of local politicians under pressure.

In a Swedish context, Nordholm (Citation2016) has analysed the relationship between the NAE and LEAs during the enactment of the national curriculum for compulsory schooling, introduced in 2011. By using Scott’s three institutional pillars as a theoretical lens, the analytical focus is on the directives of NAE and in what ways the LEAs responded to these directives. Nordholm argues that the communication from NAE foremost is characterized by normative and cultural-cognitive elements. A general observation is that this hampered the LEAs room for action regarding local implementation. Another problem for the LEAs as intermediaries of reform implementation was the lack of support and resources from the national level. In a similar study focusing on the same curriculum reform but from the perspective of both transnational and national policy pressures on the LEAs, Höstfält et al. (Citation2017) have shown several ways in which the LEAs react on policy messages: the importance of previous patterns of practices, especially in relation to goal achievement, equity and equivalence; the adaption of a coordinating role, communicating the policy discourse to school and classroom levels; a focus on systematic quality assurance but with little connection to teachers’ assessment practices and, embracing a combination of normative and regulative pressures that entails a strong commitment to intentions embedded in the national curriculum reform.

Both Nordholm’s (Citation2016) and Höstfält et al.’s (Citation2017) studies significantly contribute to our understanding of local school governance in the wake of national education reforms, while they at the same time do not specifically highlight the relationship between the LEA and the principals as heads of the school organizations. The school organizations on the local level may be comprised of different actors, such as superintendents, managers of departments/units, development managers, principals with certain responsibilities, and sometimes teachers, who may participate in school development groups at the district level. In this study, our focus is on representatives of the LEA, which in a Swedish context refers to superintendents and development managers as the main actors with principals representing the school level. In a study of the Israeli context, Addi-Raccah (Citation2015) examined the relationships between principals, superintendents, and the LEA. The author analysed how principals navigate and seek to balance their relationships with the superintendent and the LEA in the wake of increasing external pressures and a toggle of power between central and local authorities. Addi-Raccah’s argument is that principals play a double role towards the LEA. On the one hand, they may refuse interventions from the LEA if they do not acknowledge their value for the school in terms of professional development. On the other hand, principals collaborate with the LEA regarding support and extra resources. In this respect, the role of superintendents is important because they become an intermediator between the school and the LEA. By seeking support from the superintendent to negotiate with and advocate the specific needs of the school to the LEA, principals find room for action (Addi-Raccah, Citation2015).

Addi-Raccah’s (Citation2015) study provides several clues regarding the relationship between principals and the LEA that are significant for our study. In particular, the different approaches to the LEA and the role of the superintendent as committed to educational concerns and merely not administrative and financial matters are important observations. In a study on Finnish superintendents, Risku et al. (Citation2014) claimed that the role of the superintendent has transformed from being an official bureaucrat to an involved and informed executive manager of education. Similar results were presented by the Finnish researchers Pyhältö et al. (Citation2011), who identified different emphases regarding which factors were important to school development. Superintendents and local school officials generally stressed financial and technical questions as the most important in school reform, while principals underlined pedagogy and collaborative learning as being at the heart of sustainable educational reforms. However, they shared a common understanding of the general ideas that ought to underpin school development (Pyhältö et al., Citation2011).

Like Finland, Sweden’s education governance system is characterized by a decentralized structure, but as the above examples clearly illustrate, it is necessary to bear in mind that the local level may look very different between countries due to political and cultural factors. The LEA's relationship to the national level can also be characterized in various ways. Nonetheless, there are lessons to be learned from previous research when it concerns the role of LEAs and the relationships between superintendents and principals. In the following section, we present the theoretical framework that guided the analysis of our study, followed by our methodological considerations and analysis of the data.

Theoretical points of departure

As national school agencies, LEAs and schools constitute central parts of what is usually referred to as the school system. Within the organizational theory, the relationship between the different parts and layers of the system is of great interest. In this paper, we apply a neo-institutional theoretical and conceptual framework for analysing the employed policy actions from the LEA as well as how principals respond to such policy actions. The education system constitutes an institution in which schools are to be regarded as social organizations, which implies that they are rational, consist of formal bodies with the aim of attaining specific objectives, and are characterized by norms and values. From this point of view, ‘Institutions promote some organizational decisions and behavior, and they constrain others, through various, path dependent processes’ (Campbell, Citation2004, p. 65). In addition, schools often interact with other institutions and organizations and are therefore often described as open systems (Scott, Citation2008, Citation2014). Being an open system implies both opportunities and challenges (e.g. schools often face external pressure to change and conform to prevailing established rules and belief systems).

Neo-institutional theory is concerned with questions of institutional change, and processes of conformance and legitimation within and between social organizations (such as schools) in relation to surrounding institutions (Scott, Citation2008). In this study, the analytical focus is directed towards how the LEA, with its different functions and agencies, through different policy actions tries to control and support the local schools in a desirable direction. Scott (Citation2008) stresses that traditional regulatory aspects such as laws and mandatory directives only constitute one aspect of how institutions seek to control and affect social organizations. Besides the regulative elements of control and legitimacy, Scott (Citation2008) points to the normative and the cultural-cognitive aspects (see below) of the institution. Accordingly, this perspective can explain how quite deregulated and decentralized system, such as the local school system, although can be controlled and work stable over time (Nordholm, Citation2016).

Institutional change and legitimacy

To understand institutions and social organizations, their constitution and how they change and to strive to obtain legitimacy in relation to external and internal pressure, Scott (Citation2008) distinguished between three different institutional dimensions or pillars: the regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive/discursive pillars.

The regulative pillar emphasizes rule-setting, laws, sanctioning activities, inspections, monitoring, etc. Such regulative elements give institutions legal legitimacy. Through this institutional approach, different forms of regulative mechanisms of control and changes become crucial. Such mechanisms are characterized as mandatory and therefore often stem from formal and authoritative offices and agencies. Linked to the school system, such regulative aspects could, for example, comprise the national Education Act, the national curriculum with its prescribed knowledge standards, auditing systems (e.g. the Swedish School Inspectorate) and so on. Altogether, such regulative elements will both constrain and enable specific organizational behaviours and actions.

The normative element of the institution centres on the values and norms that provide the basis for dominating prescriptions, obligations, evaluations, goals, and means (Scott, Citation2014, Citation2008). This includes questions of control, change processes, and legitimacy, that is, acknowledged social agreements of expectations and conventions that anticipate its members to act in a specific way. Such pressure may arise from work norms, expectations, and attitudes towards how schools should work and take appropriate action, even in the absence of legal obligations. This means that the normative aspect often operates through ‘soft’ regulations with no formal legal sanctions attached. This may, for example, include different forms of national and local guidelines and recommendation for teachers’ assessment and grading or school leaders’ organization of school improvement and so on. Other examples of normative elements of control can be different types of national or local school improvement programmes or work-based training programmes for teachers.

The cultural-cognitive element can also be defined as a more softly regulated element of control. Compared to the normative aspect, this element primarily is linked to shared conceptions and frameworks, providing an orientation to different meanings. That is, within and between institutions and social organizations, common sense or what is taken for granted is formed around what can be regarded as ‘correct’ and legitimate opinions, beliefs, and modes of behaviour (Scott, Citation2008). This ‘common sense’ thus will constrain and enable a certain thinking, decision-making and action linked to, for example, teaching, school improvement, pupils with special needs and so on.

Even if Scott’s theory on the three institutional pillars contributes to an analytical perspective on institutions and organizations, it has been criticized for focusing too much on the ways in which institutions maintain stability and continuity, rather than on change. Nordholm (Citation2016) has, for instance, emphasized that ‘ … Scott’s framework stands out as a rather broad and somewhat blunt instrument for analysing processes in organizations at the local municipal level’ (p. 396). To understand the mechanisms behind institutional and organizational change and efforts to obtain legitimacy, inspiration can, therefore, be brought from Powell and DiMaggio (Citation1991) and the concept isomorphism. They distinguish between three different external processes or pressures that can be seen operating in close relation to the three pillars of institutions.

The first process they called coercive isomorphism, which comprises external pressure in terms of formal and informal requirements and directives addressed from authoritative actors and organizations that an institution is dependent on, for example, the NAE or the Swedish School Inspectorate. Included in this kind of coercive pressure are different forms of evaluation and sanction systems. The second pressure, mimetic isomorphism, comes from institutions’ uncertainty, instability and fear of losing legitimacy, which tend to activate processes of imitation and adaption to other more stable, successful, and legitimate institutions. Finally, when pressure originates from cultural and social norms, expectations, and truths, Powell and DiMaggio (Citation1991) referred to this as normative isomorphism. These kinds of processes are often driven by professionalism. Actors within a profession have developed a common knowledge base, experiences, and ethical approaches, which tend to create normative pressure on institutions to change and conform in a certain direction.

The neo-institutional theoretical and conceptual framework described above enables us to distinguish and elucidate the characteristics of the local policy actions which the LEA initiates with the aim to control and exercise influence over the schools as well as how actors within the schools respond to these policy actions. Notably, the three institutional elements (Scott, Citation2008), and its linked processes (Powell & DiMaggio, Citation1991), operate and interact, sometimes in mutually reinforcing and sometimes in mutually conflicting ways. What becomes interesting in this study is how the LEA and the local schools and principals cope with and navigate in relation to national regulative elements and how the same element in some ways constrains and some ways obtains a certain action.

Methodology and analytical framework

This study is interested in the dynamic interplay of policy actions between the LEA and principals in relation to a changed governing and policy landscape in Sweden. The research questions were answered through a case study (Yin, Citation2018). The data used in this study were collected within the scope of an ongoing evaluation research project. During the 1.5-year project, we thoroughly studied and analysed the local educational organization’s capacity to support schools and preschools in terms of improvement work and resource distribution. Based on the answers to a number of questions that were formulated together with the representatives from the LEA, a large amount of data was collected, analysed, and continually communicated to the LEA. A select part of these data is used in this study.

The methodological design of the case study was based on a mixed-methods approach (Creswell, Citation2010) in which both quantitative and qualitative data were collected and sampled, with each phase of the process serving as an important analytical framework for modelling and formulating questions in the next step. This design allowed us to apply an explorative approach and to obtain different but complementary types of data on the same phenomenon (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2007). In each step, we applied the neo-institutional theoretical and conceptual framework, focusing on the regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive/discursive aspects with particular reference to control, influence and legitimacy. The design and the three integrated phases of data collection are illustrated in .

Based on the results of the document analysis (Phase 1), we provide an overall description of the case in the next section, with particular focus on the infrastructure and general characteristics of the local educational organization and also what implications for governance this kind of system generates. In Phase 2, the respondents were encouraged to write comments and clarify their answers to the survey. This resulted in textual material that provided extensive qualitative empirical data.

The collected data were analysed in relation to our theoretical points of departure, which elucidated the LEA’s policy actions for governing schools and the principals’ actions for responding to such control. Although these institutional elements in practice often are intertwined, they can be analytically separated from each other in the analytical process. In accordance with this, the empirical data were coded from the regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive institutional pillars and the corresponding aspects of isomorphism. In the coding process, national laws and regulations together with local directives were defined as regulative pressures and processes of legitimacy. The normative elements were in the coding process linked to processes and contexts where normative values and expectations were formulated, recommended and highlighted by the LEA as something desirable. For example, this could comprise highlighting a school, a principal or a teacher as a kind of role-model or good example, which aimed to activate processes of imitation in the organization. When it comes to distinguishing the cultural-cognitive elements, the focus was directed to the dominating ideas, concepts and discourses linked to the activities of the school organizations. These ideas and concepts are to a great extent taken for granted and therefore they shape the understanding of what is considered appropriate and desirable actions.

A description of the case

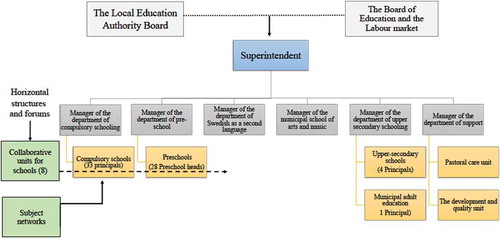

The case used for this study is an LEA in a large municipality (about 140,000 inhabitants) in southern Sweden. To put this in perspective on a national scale, the municipality in question is among the 10 largest municipalities in the country. As has been described previously, it is up to the Swedish municipalities to decide how the local school system will be organized to conform to the ideas behind the decentralized school system. This means that there are numerous variations in local Swedish school organizations. The result from the document analysis of the municipality shows that the current educational organization is characterized as having far-reaching decentralization. Decisions, responsibilities, and authorizations are generally placed on the principals at the different schools, which is in alignment with LEAs’ intentions to strengthen principals’ autonomy and responsibility over their schools. presents a schematic illustration of the organization and its different parts.

The figure above illustrates the local school organization that is the central focus of this study. At the same time, it is illustrative of the complexity that characterizes the local governance of many Swedish schools. In this case study, two different bodies (political boards) exercise political control over the schools. These are responsible for ensuring that the municipality fulfils the legal requirements from the Education Act, the national curriculum, and other ordinances. The LEA is responsible for the operational work in the school organization, with the superintendent leading the education authority together with a number of managers (who are responsible for different educational sectors or departments within the organization). Together, they constitute the overall management structure of the organization. On the lower level, principals manage preschools, compulsory schools, and upper secondary schools. One of the departments serves as a support unit with pastoral care services, school development, and quality assurance and monitoring.

In line with Davis et al.’s (Citation2012) characterization of a decentralized organization model, the results of the document analysis revealed a number of organizational challenges. We distinguished difficulties regarding vertical communication between the central administration and the schools. It was difficult for the LEA to implement common goals and visions for the whole organization while also identifying and handling quality issues at the schools. Another problem was the horizontal cooperation between the schools in terms of low knowledge mobility. That is, teachers with specific expert knowledge were oftentimes ‘captive’ to their specific school; their expertise could not be used in other parts of the organization. In order to solve this, the LEA formed collaborative units for schools and subject networks. The main purpose of these functions was to build a horizontal infrastructure between schools and thereby create better conditions for collaboration and communication.

Results: policy actions for development and control

As was discussed initially, the recentralization trend in terms of a more state-regulated governance of the school system has changed the conditions for Swedish municipalities regarding their abilities to govern and control the schools. This means that the traditional regulative methods of governing the schools have been circumscribed. Still, the Swedish Education Act emphasizes that municipalities have a far-reaching responsibility regarding schools’ quality and equality between schools. Based on these changed policy conditions, we were interested in what different policy actions the LEA employed to control the schools. Overall, our analysis points to that more cultural-cognitive and especially normative-oriented policy action seemed to have a prominent position in relation to more regulative-oriented policy actions. The particularities of this are what will be in focus for the following part.

The LEA: benchmarking and standardization of the school improvement system

An example of a policy action that was identified in the collected data was a clear benchmarking strategy. That is, the LEA continuously compared schools in relation to specific quality standards – for example, instructional practices, school leadership, and school improvement – as a way to put pressure on schools to ensure greater coherence and compliance between them. Within this benchmarking action, the LEA highlighted successful schools and used them as role models and examples of best practices in communication with other schools. Due to this best practices-oriented system, it also became important to make the schools’ results more transparent:

Comparisons are continuously made between schools … some schools are elevated and vice versa. The focus is on flaws and shortcomings, and some schools are highlighted as ‘good examples’. However, this is sometimes incorrect … the analyses are inadequate” (LEA Employee 2, Development and quality unit).

Although the current local school organization could be defined as a relatively decentralized system, this focus on specific quality standards in combination with highlighting successful schools puts pressure on schools to change in a desirable and a more uniform direction.

Moreover, to reinforce the comparisons between schools and make them more effective, the LEA was in the middle of implementing a new social technology system at the time of this study. According to the manager for the development and quality unit, this system would enable the LEA to collect statistical data linked to the schools’ performance, economy, and competences and make them more transparent and visible, not only to the LEA, but to all schools in the municipality:

We will implement a monitoring system. The improvement work will then be more systematic and structured and give us better control. Different types of objects and results indicators will enable us, but also the principals, to have better control over the schools’ outcomes. (LEA Manager, Development and quality unit)

Through the analytical lens of the theoretical framework of this article, this benchmarking strategy is characterized by a clear normative-oriented structure.

Alongside our examination of the LEA’s benchmarking policy action, we distinguished clear processes of standardization of schools’ quality communication. That is, the LEA had formalized and systematized important routines and processes linked to schools’ improvement work. Based on the regulative directive in the Swedish Education Act that all schools in Sweden must conduct a local quality assurance work, the LEA had decided that each school in the municipality was obligated to write a quality report every year to present and discuss the school’s results, prioritized improvement strategies, and identified development needs. This quality report had to be written using a central standardized template with a number of prescribed questions and issues. This standardization process also included an ambition to adopt more uniform language in the form of selected concepts with a specific definition and crucial elements of the school practice. The aim of this was to obtain a higher quality of the discussions between the school actors within and between Schools and the LEA. Accordingly, linked to the quality reports, the LEA arranged a number of seminars in which the principals presented and discussed the schools’ results and their school improvement work. These seminars were followed up with an individual quality dialogue in which each principal met officials from the LEA for deeper discussion:

The principals write a quality report, which they send to the LEA. In the next step, the LEA organizes so called ‘quality dialogues’ between principals and representatives from the LEA. Every principal also has an individual dialogue with a representative from the LEA [heads of school units]. The data that is discussed is different kinds of statistical data but also, of course, the schools’ quality reports. (LEA Manager)

These meetings had an official purpose of creating learning opportunities for the participating principals. That is, in many of these meetings, the principals had the opportunity to share experiences and knowledge related to their leadership and school improvement.

To conclude, the obligation of writing a quality report can be connected to the regulative pillar, while the seminars, dialogues and implementation of a standardized language for making the schools’ internal processes can be characterized as normative and cultural-cognitive elements of control.

Soft interventions and bypassing by the LEA

A general but central question related to the local governance of schools is how the LEA should handle schools that do not obtain desirable results, such as failing to meet national curriculum objectives. If the LEA or the Swedish School Inspectorate identified problems at a specific school, the LEA offered what they refer to as a special intervention. This intervention is comprised of help and support from the central development and quality unit with the aim of addressing the issues identified at that school. Officially, this kind of intervention is voluntary, but according to one development manager, principals could not turn down these offers because the pressure to accept was too intense: ‘These interventions are based on some kind of volunteerism. However, no principal has ever declined such an offer’ (LEA Employee 4). Thus, this kind of soft policy interventions can be related to normative pressure and expectations. However, with the exception of these interventions, several employees at the central development and quality unit expressed that they had difficulty accessing the schools. Based on the ideas behind decentralized school organization, the managers of the departments for compulsory and upper secondary school argued that it is important to respect the principals’ autonomy. In other words, these school managers could be described as having a gatekeeper function by protecting principals from external pressure:

The managers try to “protect” the schools from us … they mean that the schools have competence to run their own local improvement work … But schools and principals don’t want to highlight and talk about the schools’ shortcomings … that is why they don’t ask for support from us. (LEA Employee 3)

The quote above highlights a tension between two different functions within the LEA organization. One tension is linked to an overall governing question concerning how the national and district levels should be constituted and handled in relation to school principals’ autonomy. In this case, the central development and quality unit claims it had to by-pass the manager for compulsory or upper secondary school and find other ways to gain access to strategically important persons and contexts at the schools.

Accordingly, development managers at the central development and quality unit described how personal contacts and networks of teacher leaders (for example, expert teachers) at the schools are crucial to being involved in and affecting teachers’ professional development and schools’ improvement strategies. In this respect, they informally asked teachers if they were interested in a certain kind of improvement effort or project and used the teachers’ support to put pressure on the principals. Similarly, development managers claimed that the pastoral care unit was useful for gaining access to the internal organization of the schools. Employees at the central development and quality unit described how they often used pastoral care units’ communicative structures to get in touch with schools and how they linked central improvement strategies for increased student achievement to pastoral care units’ efforts: ‘we have to use the backdoor … we use the pastoral unit to get access’ (LEA Employee 1). Altogether, these so-called bypassing strategies by the employees at the central development and quality unit served a common purpose by establishing contacts within the schools, which can result in the schools’ employees themselves asking the development and quality unit for support or initiating school improvement efforts. Consequently, this more normatively based strategy serves as a legitimate method for the development and quality unit to influence schools’ improvement work.

Principals coping with the system: caught between defiance and compliance

The strategies and examples of how the LEA seeks to govern the schools illustrate the different challenges that may emerge within a highly decentralized school organization. The standardized monitoring system for systematic quality assurance and the benchmarking strategy form a powerful agenda-setting tool from both a normative and discursive perspective. It is against this backdrop that the various responses and policy actions from principals should be examined.

A general view among the principals was that a transparent and coherent systematic quality assurance system is very important in order to ensure equal conditions and to help create a common framework for specific assignments, resource distribution, and professional development. In brief, principals did not question a standardized evaluation system as long as it helped them to gain support from the LEA to fulfil their mission (e.g. the school budget is in balance and students’ results are in alignment with national goals). However, the principals were critical towards how the LEA has arranged the quality system in relation to their daily practice. In the survey, about 80% agreed with the statement: ‘I wish there was a clearer connection between the vision and goals of the central education authority and my unit’ ().

The main critique towards the LEA’s systematic quality assurance system is that it was too instrumental, unprecise, and lacking in a clear purpose. The principals claimed that they were not given guidance on how to interpret local policy documents and guidelines: ‘[the goals are] very vague from the LEA. The LEA, what do they really want to achieve? There are no clear goals and we own that process as principals’ (Principal 3). To some extent, this allows for a certain degree of autonomy, but the principals’ views from the interviews also hinted at the frustration they sometimes experienced when being evaluated on what they regarded as unclear grounds. The principals played along with the system, complying with the requirements of gathering data on student results and well-being.

At the same time, defiance was expressed through principals bending the rules. Sometimes this was done by avoiding aspects critical for capacity building and school development:

We never get to the bottom of things. In the quality report, the aims are so general that you can pick whatever you like and do not have to expose what is genuinely “bad.” It will never show in our documents, because it is not asked for by the LEA. How was, for instance, the Mathematics Lift [government initiative to improve Mathematics teaching] followed up? Not at all. It would have been really interesting to follow up from the perspective of the LEA. (Principal 6)

While principals knew that they were accountable for the students’ results according to the Education Act, they were also well aware of what was expected of them. In this respect, the benchmarking strategy of the LEA as a normative pressure had an impact on their autonomy. Principals admitted that there to some extent existed a culture of competitiveness between school units and in relation to the central municipal authority. In one of the interviews, a principal expressed her views on how their autonomy is conditioned by the performance of the school and in what ways the constant monitoring of school results might lead to a takeover by the central authority:

Today, it is the numbers that govern. If you have a school that achieves well, they say: “Well, fine, mind your own business.” The schools which today have very low results, well, there you intervene with a lot of support … A clear governing of the school. You assign staff from the LEA to monitor and audit, to look at the professional development, and to work with the school management. (Principal 2)

As the quote above suggests, a school with declining student achievement would be offered resources and support, which meant that the principals must also surrender some of their influence. A principal leading a well-performing school, however, tended to be left alone. This could make principals reluctant and anxious to openly admit shortcomings and to ask for support, which in turn could result in resources and support schemes being implemented too late. This has led to a reactive rather than proactive approach according to the principals. Together with the suggestion that a school take-over could be related to some sense of ‘shame’ or at least failure, underlines the normative pressure created by comparisons between schools and units.

The lack of guidance together with the implicit element of competition was considered by many of the principals to be a threat to the idea of creating a team and collaboration. The importance of ticking the boxes and delivering in accordance with the system became even more important than what was required for capacity building:

Principal 4: Some of the bosses in the development and quality unit have pushed this systematic quality assurance far, and the unit hasn’t really managed to get their acts together on professional development. It simply doesn’t add up. And then we have to take care of our own business. We run our internal organizations.

Principal 1: So it becomes even more individualistic, because if not the group [the development and quality unit] is strong and can communicate in a way that makes us feel safe, then it results in this sprawling, and everybody works in their own direction from their own visions and ideas.

There was a kind of ambivalence in the views of the principals in terms of how they positioned themselves. Compliance might come with a price in terms of decreased autonomy, or – as suggested in the recently quoted passage – the absence of conceptual and discursive coherence could result in individualism that fuel competition.

Gatekeeping and principals seeking room for action

It has been shown that the LEA would conduct specific interventions in schools based on reports from the Swedish School Inspectorate, observations made through quality reports, recurring dialogues between principals and the school manager (who act upon delegation by the superintendent), or targeted audits by development managers. The representatives from the LEA sometimes described their strategy as a kind of bypassing of the principals in order to get access to teams of teachers. The response from principals was to attempt to stop LEA development managers from side-stepping them when it concerned matters at the local school. From the results of the survey, it is also clear that a majority of the principals were critical towards the organization of the school improvement work ().

Notably, one out of four principals answered that they actually did not know if there should be a different organization. Based on the other statements in the survey regarding the LEA, the principals generally favoured horizontal structures and arenas for collaboration (). shows the principals’ answers regarding the statement: ‘The collaborative units serve as a good foundation for co-operation between schools’.

The principals claimed that, with support from the LEA, the collaborative units have the potential to become vessels and support structures for professional development and school improvement initiatives from below. In the interviews, the principals were also asked about why such a considerable number of them were uncertain about the creation of a different organization for school improvement. A general point was that the principals simply wanted to maintain control over the professional development of the schools and that they needed to protect teachers from the extra workload that might follow from an LEA intervention. In such cases, they referred to the Education Act – that is, the regulative pillar of the institution – which states that the principal is solely responsible and held accountable for decisions concerning the school.

The principals’ actions – and based on how they describe their situation – can be labelled as a type of gatekeeping, meaning that they want to prevent the LEA from accessing and using their staff. An example is that principals point out participation in national professional development programs as an argument for gaining and maintaining autonomy. By referring to the fact that their teachers are enrolled in programs issued by the state authority, principals sought to bar initiatives by development managers based on local evaluations or stall school development ideas by the LEA. In this respect, we identified a tension between the principals and the LEA concerning recruitment. Related to recruitment, principals were also critical of how the LEA tended to attract competences that are considered to be more useful in the schools. In the interviews, the principals claimed that there was a tendency for the central administration, and in particular the quality and development unit, to grow on the expense of the local schools’ needs, and that this created imbalance between the school units and the LEA. Expert competences and functions, such as special needs teachers, would be recruited for central assignments. The following sequence from a discussion during one of the interviews illustrates the principals’ views:

Principal 1: maybe they should consider the size of the office

Principal 3: It is pretty large here [referring to the LEA administration building]. For example, there are a lot of special needs education teachers that are employed, and we have a shortage of special needs education teachers because there is no one who wants to be out in the schools but rather enter this building within its four closed doors and work instead. That is, work with what does not show. On the other hand, it is very nice for us to have a life of our own and to be independent, but then again, you might not need such a large overhead.

Principal 5: New functions just keep on emerging all the time. You wonder, what is this function supposed to do?

Principal 3: Many of the best are recruited to this place, and we do not get any outputs back to us but stand without competence and specialists.

Principal 5: And yet, this whole place and we are supposed to be there for the sake of our pupils. If there is no purpose, well, then you might have to consider if the function in question actually should exist?

Strongly related to the question of the establishment of different functions were the problems that principals experienced regarding equality between schools. There were too many variations between the schools for a number of important aspects, such as students’ results, leadership capacity, teacher competence, instructional quality, etc. In one of the interviews, a principal argued that schools definitely needed the freedom to work in different ways, but a more clear and transparent strategy of how the LEA is supposed to close achievement gaps and create equal conditions between schools was required. An apparent risk, according to the principal, was that it in the end would depend on the authority, and legitimacy of the principal:

There is no clear principle for how we should work for equal conditions. Equality is compromised. There has to be ideas about this … The schools just keep on pushing on their own work and move on. A lot of unit-based work but no support from the top. (Principal 8)

To some extent, there was ambivalence among the principals. For instance, it was common for principals to emphasize the LEAs’ lack of vision and guidance; yet, at the same time, they did not want increased central control regarding the schools’ internal work. In the survey, about 80% of the principals disagreed with the statement ‘The school improvement work should, to a greater extent, be managed by the central education authority’, and this is illustrated in .

During the interviews, the principals repeatedly stressed that the LEA should keep its hands off school improvement work and especially the professional development of the teachers. This critique mainly concerned the quality and development unit. When asked about why they thought so many of the principals were critical towards a more centralized school improvement organization, one of the principals answered: ‘I do not think they should control us more … it is important that every school is free to decide over what they need to improve and how to organize and carry out the improvement work’ (Principal 7).

It is evident that principals appreciated and wished to safeguard their autonomy, but they also requested a more structured and coordinated central organization based on conceptual clarification and equal conditions. This included a more effective use of competences within the organization, centrally defined assignments regarding different educational functions, a more transparent and efficient resource allocation, and centralized support for school improvement.

To conclude how principals respond to policy actions, the principals were willing to reach out to the LEA for support, but this was paired with an ambivalence and anxiety that their room for action would be diminished and that different agendas with systems and concepts for quality assurance would be put into play, which would create internal competition and result in more normative pressure being put on the principals. A related aspect was the concern that the LEA did not present clear aims and a transparent resource distribution system. This seems to suggest that principals lack a common conceptual foundation for guidance and interpretation regarding decision-making, actions linked to classroom practices and school improvement, that is, aspects related to the cultural-cognitive pillar.

Conclusion of policy actions of the LEA and principals in relation to institutional pillars

In our analysis of the empirical data, we have observed several examples of policy actions from the LEA and responses from the principals. In order to present the general results from our case of local school governance, gives an overview of the policy actions identified by the LEA and the principals and how these relate to our theoretical and analytical framework.

Figure 7. Overview of policy actions of the LEA and principals in relation to institutional pillars.

In the next concluding section, we highlight and discuss the main findings from the perspective of the neo-institutional theoretical concepts of legitimacy and isomorphism and also how our results add new insights to previous research in the field.

Discussion

The different faces of local school governance

This paper has explored and theorized on the dynamics of local school governance through a case study of a local school organization in a large Swedish municipality. We have focused on questions regarding employed policy actions from the LEA employ for governing the schools in the municipality, principals’ responses to policy actions and used a theoretical lens of neo-institutional concepts such as institutional change, legitimacy, and isomorphism for understanding the dynamic interplay of policy actions between the LEA and principals.

We have distinguished a number of strategies and policy actions that LEAs employ in accordance with their missions, as stated by the Education Act. These include interventions for changing and improving schools’ organization, mediating national-level policy, and helping to maintain an equity focus (Rorrer et al., Citation2008). These roles and processes are linked to different organizational functions, which are not always harmonized. Occasionally, they are in conflict because they are driven by different interests and ideas about how to achieve results, higher quality, and equity. In a decentralized organization such as the case used for this paper, it is evident that there are challenges in obtaining consensus and communication between the different branches of the organization. There is especially a need to reinforce the vertical relationship between the central level and the school units, for example, in terms of more efficient use of competence. However, at the same time, there is a desideratum for the creation of horizontal networks and arenas. The different policy actions identified in the analysis can be regarded as expressions and attempts to gain and maintain legitimacy and to create room to manoeuvre in the organization.

There are a number of observations from the empirical data that help us to better understand the complexity in the governance of the local school organization. One of the dimensions is the difficulty of combining the logics of the system of accountability with normative and discursive dimensions related to learning and development. This observation is also supported by Höstfält et al. (Citation2017) who have claimed that there is a decoupling between systematic quality assurance on LEA level and actual school and classroom practices regarding, for instance, teachers’ assessment. Our study expands the understanding of this detachment. There is a perceived tension between how LEAs seek to govern through a conceptual framework that in theory has positive connotations (i.e. quality and dialogue), but with the socio-technological system for accountability that requires results, it is in practice conceived as two separate processes. The language and concepts of the quality assurance system constitute a cultural-cognitive element of the institution in terms of how it prescribes and frames how the different actors should think and act (Scott, 1995; 2001). The standardized system serves as a representation of both the regulative and normative pillars. In the first case, the system falls back on legal requirements by the Education Act and regular inspections from the Swedish School Inspectorate. At the same time, the system is positioned within a context of normative expectations of raising student attainment that implicitly define how schools should work and take appropriate actions. Not being successful as a principal in this respect includes an element of shame and being offered help from the LEA.

To bring further clarity to the forces that are at work, the concept of coercive isomorphism can be applied to illustrate how formal requirements of evaluation from the NAE or the Swedish School Inspectorate create external pressure on both LEAs and principals. As Nordholm (Citation2016) has shown, the governance patterns from the NAE during the implementation of the curriculum for compulsory schooling were mainly characterized as normative and cultural-cognitive elements, which together with a lack of resource distribution had a negative impact on the LEAs. In order to deal with the legal responsibilities, LEAs have constructed support departments for evaluating and analysing results, intervening and monitoring school improvement work and providing professional development for teachers. A significant part of this monitoring system is the implementation of a standardized quality assurance system for accountability, which provides a foundation for LEAs to take legitimate action if a school does not reach desirable results. As has been shown, the principals complied with this system and considered it to be important for resource distribution and ensuring equity. In this respect, the policy actions of the principals can be characterized as mimetic isomorphism because they sought to imitate each other and comply with the system out of fear of losing legitimacy. If a principal was not able to deliver, there was a risk that the LEA would intervene, and this might inflict on the autonomy and legitimacy of the principal in the eyes of others.

The purpose of the standardized system for quality assurance is to ensure schools change and conform in a similar direction. As such, the system also tends to create a normative pressure on the principals because the results from their schools become subject to benchmarking and the elevation of successful schools as role models. Powell and DiMaggio (Citation1991) referred to this pressure that originates from expectations and cultural and social norms as normative isomorphism. This kind of isomorphism allows for the identification of how certain processes and routines for quality development are named and how forums are constructed for presenting school results and sharing experiences linked to school improvement systems. An example is the already mentioned quality dialogues and seminars. However, from the analysis of the empirical data, it became clear that the principals also stood up against this normative and cultural-cognitive pressure. Together with what is regarded as an absence of clear goals from the LEA and experiences of competitiveness and individualism spurred by comparisons between schools and units, the principals at times suspected there was a hidden agenda. They were also critical towards the instrumental character of the accountability system, and their suspicion and discontent were generally directed towards the development and quality unit of the LEA. Even if this unit has the mission to support the schools through different kinds of interventions, the principals were critical towards its interference in what they considered to be internal affairs of the school. In brief, the principals asked for resources but wanted to decide for themselves how they organized collaborative learning and professional development at their schools (cf. Pyhältö et al., Citation2011).

As illustrated in , benchmarking, interventions, and bypassing from the LEA are met with both compliance and gatekeeping from principals. This study shows that there seems to be a gap between the qualitative analyses aggregated at the school level and the resource distribution to call on these needs at the central level. From previous research on the relationship between the LEA and principals, we know that principals seek support from the superintendent concerning the needs of the school and to grapple with this gap (Addi-Raccah, Citation2015). However, according to our results, it seemed that principals did not seek support from the superintendent at all. On the contrary, they rarely referred to the superintendent, which might suggest that the superintendent is considered to be too far up the organizational ladder. Rather, it was the managers of compulsory and upper secondary education that were mentioned. An interesting observation is that these managers operate at the same level as the manager for the department of support. Regarding how the development managers felt about the compulsory school and upper secondary education managers, it became clear that there was tension between them.

This tension concerned to what extent the managers at the development and quality unit should have access to the schools. It reveals the significance of observing actors at intermediate levels within the local school organization. The managers of the two school departments safeguarded the principals’ autonomy when it came to the organization and management of school improvement efforts at individual schools, while the representatives from the development and quality unit emphasized that the principals needed external support and interventions to improve the schools. This can be understood in light of the changed landscape of school governance in Sweden, where the formal regulation from the Education Act actually allows for a mimetic and normative-oriented isomorphism (Powell & DiMaggio, Citation1991). On the one hand, the Swedish Education Act emphasizes the principals’ autonomy concerning the schools’ organization, economy, and school improvement initiatives. On the other hand, the same law underlines the LEAs’ responsibility for school results and providing equity. However, this creates a sense of ambiguity and illustrates how actors in the local school organization struggle to make sense of what is known as dual governance.

Limitations

As a final remark, this study was limited by the fact that it focused on a single case of a local school organization in a large municipality. Still, the results concerning the characteristics of local policy actions initiated by the LEA as well as how principals responded to these policy actions confirm what previous research has shown regarding the relationships between principals, superintendents, and LEAs. The application of neo-institutional theory has proven to be a fruitful perspective of identifying and analysing the complex relationships and multifarious aspects of local policy actors. In order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of local school governance, one must take into account all different levels and actors and their relationships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Addi-Raccah, A. (2015). School principals’ role in the interplay between the superintendents and local education authorities: The case of Israel. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(2), 287–306. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-10-2012-0107

- Adolfsson, C.-H. (2013). Kunskapsfrågan – En läroplansteoretisk studie om gymnasieskolans reformer mellan 1960-talet och 2010-talet [The question of knowledge – A curriculum study of the Swedish upper secondary school reforms between the 1960s and 2010s] [Doctoral dissertation], Linnaeus UNiversity Press, Växjö .

- Adolfsson, C.-H., & Alvunger, D. (2017). The nested systems of local school development: Understanding improved interaction and capacities in the different sub-systems of schools. Improving Schools, 20(3), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480217710874

- Alvunger, D. (2015). Towards new forms of educational leadership? The local implementation of förstelärare in Swedish schools. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 1(3), 55–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.30103

- Alvunger, D. (2018). Teachers’ curriculum agency in teaching a standards-based curriculum. The Curriculum Journal, 29(4), 479–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2018.1486721

- Anderson, S. E., & Daly, A. J. (2013). Diversity in the middle: Broadening perspectives on intermediary levels of school system improvement. Journal of Educational Administration, 51 (4), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231311325703

- Campbell, J. (2004). Institutional change and globalization. Princeton University Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2010). Mapping the developing landscape of mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Sage handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 45–68). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods. SAGE.

- Cuban, L. (1998). How schools change reforms: Redefining reform success and failure. Teachers College Record, 99(3), 453–477.

- Davis, B., Sumara, D., & D’Amour, L. (2012). Understanding school districts as learning systems: Some lessons from three cases of complex transformation. Journal of Educational Change, 13(3), 373–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-012-9183-4

- Dumont, H., Istance, D., & Benavides, F. (2010). The nature of learning: Using research to inspire practice. OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.

- Finnigan, K. S., Daly, A. J., Che, J., & Daly, A. J. (2013). Systemwide reform in districts under pressure: The role of social networks in defining, acquiring, using, and diffusing research evidence. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(2), 476–497. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231311325668

- Forsberg, E., & Lundahl, C. (2012). Re/produktionen av kunskap i det svenska utbildningssystemet [Re/production of knowledge in the Swedish education system]. In T. Englund, E. Forsberg, & D. Sundberg (Eds.), Vad räknas som kunskap? Läroplansteoretiska utsikter och inblickar i lärarutbildning och skola [What counts as knowledge? Curriculum theory perspectives on teacher education and school] (pp. 200–224). Liber.

- Fullan, M. (2000). The return of large-scale reform. Journal of Educational Change, 1(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010068703786

- Grek, S., Lawn, M., Lingard, J., Ozga, J., Rinne, R., Segerholm, C., & Simola, H. (2009). National policy brokering and the construction of the European Education Space in England, Sweden, Finland and Scotland. Comparative Education, 45(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060802661378

- Hamilton, L. S., Schwartz, H. L., Stecher, B. M., & Steele, J. L. (2013). Improving accountability through expanded measures of performance. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(4), 453–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231311325659

- Hamilton, L. S., Stecher, B. M., Russell, J. L., Marsh, J. A., & Miles, J. (2008). Accountability and teaching practices: School-level actions and teacher responses. Research in Sociology of Education, 16(1), 31–66.

- Hopkins, D., Stringfield, S., Harris, A., Stoll, L. Y., & Mackay, T. (2014). School and system improvement: A narrative state-of-the-art review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.885452

- Höstfält, G., Sundberg, D., & Wahlström, N. (2017). The recontextualization of policy messages – The local authority as a policy actor. In N. Wahlström & D. Sundberg (Eds.), Transnational curriculum standards and classroom practices: The new meaning of teaching (pp. 66–82). Routledge.

- Huber, S. G. (2011). School Governance in Switzerland: Tensions between new roles and old traditions. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39(4), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143211405349

- Lawn, M., & Lingard, B. (2002). Constructing a European policy space in educational governance: The role of transnational policy actors. European Educational Research Journal, 1(2), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2002.1.2.6

- Leat, D. (2014). Curriculum regulation in England – Giving with one hand and taking away with the other. European Journal of Curriculum Studies, 1(1), 69–74.

- Leat, D., Livingston, K., & Priestley, M. (2013). Curriculum deregulation in England and Scotland: Different directions of travel? In K. Kuiper & J. Berkvens (Eds.), Balancing curriculum regulation and freedom across Europe (pp. 229–248). SLO.

- Lindensjö, B., & Lundgren, U. P. (2014). Utbildningsreformer och politisk styrning. [Education reforms and political governance]. Liber.

- Nieveen, N., & Kuiper, W. (2012). Balancing curriculum freedom and regulation in the Netherlands. European Educational Research Journal, 11(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2012.11.3.357

- Nordholm, D. (2016). State policy directives and middle-tier translation in a Swedish example. Journal of Educational Administration, 54(4), 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-05-2015-0036

- Powell, W., & DiMaggio, P. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. University of Chicago Press.

- Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Pietarinen, J. (2011). A systemic perspective on school reform: Principals’ and chief education officers’ perspectives on school development. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111102054

- Resnick, L. B. (2010). Nested system for the thinking curriculum. Educational Researcher, 39(3), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X10364671

- Risku, M., Kanervio, P., & Björk, L. G. (2014). Finnish superintendents: Leading in a changing education policy context. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 13(4), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2014.945653

- Robertson, S., & Dale, R. (2015). Towards a ‘critical cultural political economy’ account of the globalising of education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 13(1), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2014.967502

- Rorrer, A. K., Skrla, L., & Scheurich, J. J. (2008). Districts as institutional actors in educational reform. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(3), 307–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08318962

- Sassen, S. (2006). Territory, authority, rights: From medieval to global assemblages. Princeton University Press.

- Scott, W. (2008). Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory and Society, 37(5), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-008-9067-z

- Scott, W. (2014). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests and identities (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Seashore Louis, K. (2013). Districts, local education authorities, and the context of policy analysis. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(4), 550–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231311325695

- SFS (2010:800). Skollagen [The Swedish Education Act].

- Smith, M. S., & O’Day, J. (1991). Systemic school reform. In S. H. Fuhrman & B. Malen (Eds.), The politics of curriculum and testing: The 1990 yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (pp. 233–267). Falmer.

- Spillane, J. P. (1996). School districts matter: Local educational authorities and state instructional policy. Educational Policy, 10(1), 63–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904896010001004

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2017). Transnational curriculum standards and classroom practices: The new meaning of teaching. Routledge.

- Yates, L., & Collins, C. (2010). The absence of knowledge in Australian curriculum reforms. European Journal of Education, 45(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2009.01417.x

- Yin, R. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE.