ABSTRACT

A key concern in international educational policy during the 21st century has been the impact of teacher professionalism on outcomes of schooling. Sweden makes for an interesting case because of the country’s initiatives to improve the quality of education through an academization of the teachers. The aim of this study is to analyse how Swedish state policy of ‘education on a scientific foundation’ is constructed in a selection of texts and videos presented by the Swedish National Agency of Education, and how these policy texts construct discourses of teacher professionalism. The result shows how the formulation in the Education Act, prescribing that the education shall rest on a scientific foundation, is interpreted into ‘policy-as-text’ and a policy apparatus consisting of four central concepts. Here, the terms ‘research-based way of working’ and ‘evidence’ are added to the terms ‘scientific foundation’ and ‘proven experience’ from the Education Act. Furthermore, the result shows three policy discourses of teacher professionalism that are constructed in the analysed texts: the selectively critical and accountable teacher; the positive, flexible, responsible and effective teacher; and the semi-autonomous teacher.

Introduction

The Swedish Education Act of 2010 stipulates that Swedish education shall have a scientific foundation and be founded on proven experienceFootnote1 (SFS Citation2010:800, §5). Sweden was the first country in the world to include in its Education Act such clear stipulations to schools and their professionals. In the Education Bill (Prop Citation2009/10:165), the need for change was expressed in terms of new de-centralized forms of control, as for instance, criteria for management by objectives and results, equality as a consequence of the free school choice, and a clearer emphasis on the knowledge dimension in education.

Both in the Swedish Education Act and in the above Education Bill, the stipulation about scientific foundation and proven experience was relatively vaguely expressed, and the concepts of ‘scientific foundation’ and ‘proven experience’ can therefore be seen as ‘boundary objects’, i.e. non-definitive concepts, the interpretation of which may vary depending on context and time, but still be so robust that interpretative vagueness remains unproblematic (Star & Grieshemer, Citation1989). The definition and interpretation of the concept of scientific foundation have developed in different textual frameworks. The Education Bill (Prop Citation2009/10:165) described scientific foundation mainly in relationship to the teachers’ scientific attitude, whereas the National Agency of Education (NAE) expresses it in relationship to course content and teachers’ methods of developing their own teaching (content and form) (Adolfsson & Sundberg, Citation2018).

The NAE has the government mandate to support organizers and professionals in Swedish schools to handle their official assignments, e.g., by disseminating research through research surveys, initiating in-service training and issuing so-called ‘general advice’. Thus, the NAE is an important actor when it comes to clarifying how the Education Act should be interpreted and implemented by teachers, head teachers and other members of staff in Swedish educational practices. Therefore, in this study, we investigate how policy intended to implement ‘education on a scientific foundation’ has been discursively enacted by the NAE, and how teacher professionalism is constructed through such enactments.

Background and research review

The notions that school practice should be based on scientific knowledge, and that schools and academy should have a close relationship, are not new ideas in Sweden. These ideas also rest on a national and international assumption that science positively affects both schools and society (Levinsson, Citation2013; Nordin, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2005, Citation2015; Serder, Citation2015). Already in the 1948 Education Commission (SOU Citation1948:27), was described the need for teachers to have access to research-based professional knowledge in order to handle the political vision of ‘a school for all’. Likewise, the Education Drafting Committee report 1957 stressed the relationship to research in order to develop the internal practice of schools (SOU Citation1961:30). Also, the 1977 Higher Education Reform highlights the fact that teachers’ knowledge base needs clearer scientific underpinnings, and that teacher education henceforth is to be included within the realm of higher education (Högskoleförordningen (Citation1977:263). The same argumentation is broached in the preparatory work before the restructuring of the teacher education in 2001 (SOU Citation1999:63) and 2011 (SOU Citation2008:109). The political desire that teacher education should have impact on school development and goal attainment is clearly expressed, and the change focuses on teachers’ scientific competencies and approaches. This is also visible in the new subject of educational science within teacher education, also manifested as an area of research within The Swedish Research Council (SOU Citation2005:31). Other political incentives to strengthen teachers’ knowledge base are the founding of the Swedish Institute for Educational Research (Skolforskningsinstitutet), the launching of graduate schools for teachers, and the emergence of practice-based research (Prop Citation1989/90:41; SOU Citation2018:19), which for instance, today is expressed in the project ULF (Swedish acronym for Development, Learning, Research).Footnote2 Practice-based research is therefore also a way of strengthening the link between teachers’ and schools’ development, and the development of teacher education. Furthermore, since its inception in 1991, the NAE has had a government mandate to ascertain the qualitative development of Swedish schools. In contrast to previous authorities, the NAE’s strategy was to put the teachers themselves in charge of the development, aided by research and a scientific approach. (Aasen & Prøitz, Citation2004).

The strategy used in the Swedish context – to achieve increased quality in schools through academization and professionalization of the teaching staff – may, in line with Stigler and Hiebert’s reasoning (Citation1999), be expressed as a reform strategy where school development is expected to take place through implementation of centrally developed reforms (cf. Carlgren, Citation2010; Rapp et al., Citation2017). According to Adolfsson and Sundberg (Citation2018), this strategy has gathered momentum over the past few years. Earlier, incentives for educational research initiatives were driven by expectations, assumptions and indirect ambitions, and a trust in the profession. In comparison, today’s control operates more directly to create conditions for research with clearly stated ambitions to improve pupils’ learning and achievement through practices of teaching. One reason for this coercive strategy might be that historically, teachers have not had a strong epistemic culture where scientific foundation is seen as a natural point of departure, both in terms of everyday school practice and in methods of school development (Carlgren, Citation2010; Kroksmark, Citation2013). Rather, teachers have regarded their professional knowledge more in terms of practice-based proficiency acquired through personal experience (Åman & Kroksmark, Citation2018; Lindqvist & Nordänger, Citation2007). Thus, the teachers in Sweden have historically been regarded as a prerequisite for school quality, to handle or improve through professional development, rather than being considered the driving force of research-based knowledge development (Carlgren, Citation2018).

The urge to reform schools – e.g., through a more perspicuous science discourse and school development discourse has increased in connection with the school crisis discourse that developed in politics and in the media in the mid-2010s, when, in international comparisons like PISA and TIMSS, Swedish school results dropped below average for the first time (Nordin, Citation2014; Ringarp, Citation2016; Lundahl & Serder, Citation2020; cf. Grek, Citation2009). The school crisis discourse is connected to the discursive idea of schools as a major contributor to national competitiveness and economic growth and as a key factor in the knowledge economy. In line with this, the teachers – and their professional competence and quality – are important (Commission of the European Communities (CEC), Citation2000; OECD, Citation2005, OECD, Citation2015, OECD, Citation2018; Darling-Hammond, Citation2000; Ozga et al., Citation2006; Schleicher, Citation2016; Dovemark et al., Citation2018). This can be seen as a background for the political intention to both academize and professionalize the Swedish teacher profession.

The teachers’ approach to research has been described in terms of the concepts of producer, informed and consumer (Levinsson, Citation2013). When teachers are seen as producers of research, they actively create their own knowledge basis. This approach to research is unusual in Sweden as well as in the rest of the western world (Carlgren, Citation2010). In the research-informed approach, teachers are active and independent, and may influence the choice of research to use in relationship to their own practice. In the approach where teachers mainly are seen as consumers, research should be disseminated through other parties, for example, in the form of ‘best practice’ (Ensor, Citation2004). In the consumer approach, the evidence discourse becomes significant. The evidence discourse in education follows examples from other professional fields, e.g., the field of medicine, which compared to the educational field has a clearer epistemic culture and a discourse of evidence that has expanded within the profession as a bottom-up process (Krejsler, Citation2013). For teachers, on the other hand, it is the politicians and policy makers that are active in changing the approaches and methods of professionals (Persson & Persson, Citation2017).

The relationships between professionalism and professionalization are also essential here. Two different logics or objectives can be identified: (i) to professionalize, i.e. to raise the status and autonomy of teachers as professionals; and (ii) to strengthen teachers’ professionalism,Footnote3 i.e. teachers’ professional competence and knowledge (Ben-Peretz, Citation2011; Carlgren, Citation1999; Englund & Solbrekke, Citation2015; Frostenson, Citation2015; Lundström, Citation2015). The two objectives are often integrated or related to each other, for example, since raised professionalism is seen as a way to increase professionalization. Considering the changes in the political control over teachers, with a more marked top-down implementation of policies, Lindblad (Citation1997) argues that state efforts to professionalize Swedish teachers could be regarded as an imposed professionalization – a process that regards the academization and professionalization of teachers as means to reach other ends, e.g., increased effectiveness and increased control over the activities in Swedish classrooms (Persson & Persson, Citation2017). The clear connections between scientific foundation and systematic quality work (SQW) in Swedish educational policy can also be seen as an indication of this logic (Bergmark & Hansson, Citation2020).

Previous research on policy work to implement a scientific foundation in Swedish education is limited. However, Bergmark and Hansson (Citation2020) show that teachers and head teachers have found the purpose vague; also, they state that implementation of the intention to provide education on scientific foundation is a complicated and complex process. Their study shows, for example, that teachers and head teachers refer local enactment of education on a scientific foundation to school development and quality work. The results are in line with Rapp et al. (Citation2017), who also acknowledge the top-down character of the conceptualizations and ideological underpinnings of a scientific foundation to education (cf. Hansson & Erixon, Citation2020; Wennergren & Åman, Citation2011). Åman and Kroksmark’s (2018) study of teachers’ perception of scientific foundation shows that teachers do not see scientific foundation as particularly relevant for their profession. Instead, the results indicate that teachers are anchored to a praxis paradigm, and are rather reluctant to research. The probable reason for this, according to Åman and Kroksmark, is partly a lack of scientific tradition, but partly also that schools do not have clearly organized structures or models for research-based practice.

From previous research, little is known about how state policy promoting research-based education discursively affects the professionalism of teachers. Accordingly, the policy work to define and implement research-based teacher professionalism becomes an interesting object of inquiry (cf. Alvunger & Wahlström, Citation2018), not least because of the formally endorsed emphasis on research as a foundation for all educational practices. In the analysis of policy initiatives to implement the Education Act’s formulation of scientific foundation, this study proposes a shift in focus, from ‘problem solving’ to what Bacchi refers to as ‘problem questioning’, interrogating the ways in which proposals for change represent ‘problems’ (Bacchi, Citation2009, p. vii). Hence, we argue that an analysis of the problem representations articulated or implied in policy texts can reveal ideological standpoints and political agendas.

Aim and research questions

This study aims to analyse how education on a scientific foundation, as described in the Education Act (SFS Citation2010:800, §5), is enacted and constructed in policy texts by the National Agency of Education (NAE). We also investigate which problems (stated or implied) this policy work aims to solve, and how it constructs teacher professionalism.

The study revolves around the following questions

How is policy of education on a scientific foundation represented and constructed in the policy texts?

How is teacher professionalism constructed and regulated in relation to education on a scientific foundation?

Which representations of problems are described or implied, and what (if anything) is contradicted or neglected in this regard?

Theoretical framework

In the present study, we analyse enactments of the legal text of the Education Act into policy on the official website of the NAE. Following a social constructionist epistemology, we regard the use of language in the texts as discursive practices – i.e. ‘practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak’ (Foucault, Citation1986, p. 49). Thus, we regard descriptions, knowledge claims or representations of ‘problems to be solved’ in the texts as relative and situated, and as influenced by political and/or ideological discourses. We argue that an educational system is in itself ‘a political way of maintaining or modifying the appropriation of discourse’ (Foucault, Citation1981, p. 64) along with the certain knowledges and powers embedded in such discourse(s). Thus, in this paper discourse is understood as, on the one hand, the construction of certain constraints and possibilities for thought, speech and action and, on the other, a resource for the production of meaning.

Ball et al. (Citation2012) defines policy as ‘texts and “things” (legislation and national strategies) but also as discursive processes’ (p. 3). We follow this idea in the present paper by considering two parallel ways of interpreting policy in the analysis: policy-as-text and policy-as-discourse (cf. Bacchi, Citation2000; Ball, Citation1993). The idea of policy-as-text is used in the present study to investigate how the formulation regarding scientific foundation in the Education Act is interpreted into encoded representations of meaning in the analysed policy material. Such representations are a product of compromises which ‘shift and change their meanings in the arenas of politics’ (Ball, Citation1993, p. 11), and even if they rarely dictate teacher behaviour, they do ‘create circumstances in which the range of options available in deciding what to do are narrowed or changed’ (p. 12). In this way, the policy texts restructure, redistribute and disrupt power relations ‘so that different people can and cannot do different things’ (p. 13).

Regarding the conceptualization of policy-as-discourse, Ball (Citation1993) emphasizes the need to consider how collections of related policies ‘exercise power through a production of “truth” and “knowledge”, as discourses’ (p. 14) that regulate how people govern themselves and others. Policy as discourse constructs certain possibilities for thought, language and other actions, while inhibiting ways of thinking and speaking otherwise, thus limiting both the ways actors can respond to changes, and their understanding of policy and what it does. Ball (Citation1993) also points out that one effect of policy-as-discourse may be that possibilities of different actors to make themselves heard are redistributed in a way that silences or de-authorizes some voices while others come across as speakers worth listening to. The concept therefore serves well in examining how discursive actions – performed in and by the selected texts – structure, define, enable and/or delimit teacher professionalism in different ways.

In the present study, we also analyse notions of performativity in the data material – i.e. ‘a technology, a culture and a mode of regulation’ (Ball, Citation2003, p. 16) that creates ‘a set of pressures which work “downwards” through the education system’ creating expectations of teacher performance as ‘delivery’ (Ball et al., Citation2012, pp. 74–75). This concept is deployed to scrutinize discursive events where teacher professionalism is constructed in relation to desired aspects of performance that could be evaluated in different ways. Discourses of performativity provide new modes of description and new possibilities for action, which in turn create new social identities and redefine what it means to be a teacher – e.g., in relation to a meta-narrative of research-based education as a way to improve teachers’ performances. Here, the mandate different policy actors are attributed with – to decide what to value and how to evaluate it – plays a crucial role (Ball, Citation2000; Ball et al., Citation2012).

Furthermore, we are inspired by Bacchi’s (Citation2009) analytical approach expressed in the question ‘What’s the problem (represented to be)?’ Thus, we depart from the notion that all policy initiatives aim to solve perceived problems of some kind, e.g., to address a lack of quality among Swedish teachers through processes of academization. Like Bacchi, we also challenge the idea that proper definitions of such problems would automatically facilitate appropriate solutions. Rather, an inquiry of the ways problems are represented in the analysed policy texts can serve to problematize underpinning assumptions and the ways teachers are positioned as professional subjects. Hence, the present study takes an interest in expressed or implied problems that are represented in the descriptions of scientific foundation and research-based school teaching. What is contradictory in such policy work is another aspect of interest in the analysis.

Here, we need to acknowledge a paradoxical dilemma of post-structural ontology – i.e. that we as researchers also engage in discursive practice when scrutinizing the texts produced by the NAE in a text of our own. As Petersen (Citation2015) points out:

‘Scientific’ texts are textual performances, ‘reflexive’ texts are textual performances, ‘confessional’ texts are textual performances, and when placed alongside each other, may work to destabilise the presumed authenticity and authority of each. (p. 148)

Nevertheless, since the analysed texts depart from a legal reform intended to raise school quality, we argue for the value of a post-structural attempt to analyse how this intention is enacted through policy and how such enactments interact in the shaping of teachers as professional subjects. Although we, as policy researchers, also could be regarded as enactors of policy, a critical analysis of state policy can aid to ‘disrupt the singular authorial voice and call attention to the ways in which authority is sought achieved’ (Petersen, Citation2015, p. 148).

Methodology

The empirical material underlying the analysis in this study consists of texts, graphic models and video material collected from the official website of the NAE in the spring of 2019.Footnote4 The production of empirical data began by conducting a search for the term ‘scientific foundation’ (vetenskaplig grund in Swedish) using the internal search engine on the agency’s website. The retrieved web pages contained varied versions and combinations of either one or both words in the search string.Footnote5 A first read-through of the retrieved material, keeping only web pages that included ‘scientific’ (i.e. vetenskaplig) and its related forms (e.g., the noun ‘science’ or vetenskap), resulted in 56 unique web pages,Footnote6 37 of which contained the exact text string ‘scientific foundation’. Since the common denominator between the 56 texts was that the word ‘scientific’ appeared in some grammatical form, they dealt with a broad variety of topics. For example, a number of the web pages reported or described selected educational studies, while others displayed syllabi and grade criteria for certain school subjects (e.g., physics and chemistry) that included the word scientific (naturvetenskaplig) in various ways. Other texts referred to ‘scientific foundation’ to legitimize various organizational conditions, regulations or initiatives. However, due to the scope of the study, we decided to narrow the focus of the analysis to the smaller set of texts in the data material that were engaged in depicting and clarifying how ‘scientific foundation’, and related concepts, should be understood and deployed by teachers and school personnel in an educational setting.

Hence, the empirical material consists of the textual content of five web pages that display descriptive and explanatory texts addressed to teachers and school leaders (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019a, National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019b, National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019c, and National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d). Four videos embedded in the analysed webpages were transcribed, with a focus on spoken language, and added to the empirical material. One of the five webpages displayed the cover of a book with the title Research for the classroom – Scientific foundation and proven experience in the practice (Forskning för klassrummet – Vetenskaplig grund och beprövad erfarenhet i praktiken), as well as a web link to download the book in pdf format. Here, we made the decision to include the whole book in the data material (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013) due to its function, as expressed on the back of the book, to describe ‘scientific foundation’ and related concepts as well as to stimulate discussions in schools about the operationalization of these concepts.Footnote7

The ensuing phases of the analytic work focused on discursive constructions in the policy material through an abductive interplay between re-readings of the data material and analytical efforts to thematize the same by operationalizing concepts from the theoretical framework presented above. Through repeated (re)readings and (re)categorizations of the material, we arrived at the discursive constructions presented in the material. During this work, the following analytical questions have been guiding our analytical work:

How are ‘scientific foundation’ and other related concepts described and discursively constructed in the texts (including models and videos)?

How are teachers and their teaching practice described in the texts (including models and videos)?

What is at stake/what is made important for professional practice in the descriptions – and what relevant aspects (if any) are left unmentioned or unproblematized?

Which problems of teacher professionalism are articulated or implicated in the material to legitimize policy of scientific foundation?

Are there any internal contradictions in the analysed policy texts?

A policy-as-text aspect of this analytical work attempts to show how different discursive elements in the data material contribute to the interpretation of the Education Act into policy on the NAE website. A policy-as-discourse aspect of the analysis focuses on our interpretations of the discursive consequences for teachers’ professionalism and professionalization, i.e. ‘the ways in which policy discourses and technologies mobilise truth claims and constitute rather than reflect social reality’ (Ball, Citation2015, p. 307).

Result

The present study attempts to analyse the way policy of education on a scientific foundation is described and explained, and thereby enacted, at the NAE website, with a focus on the discursive effects for (ideals of) teacher professionalism. In the first section we describe the part of the result that focuses on how the formulation of the Swedish Education Act materializes into policy-as-text in the analysed texts. The following sections describe how teachers are discursively constructed and subjectified, as professionals, in and through the policy texts.

The Education Act enacted into policy

The formulation of scientific foundation in the Education Act itself (SFS Citation2010:800) is a ‘product of compromises at various stages’ (Ball, Citation1993, p. 11). Since the present study focuses on the NAE as a policy actor, we regard the formulation of the Act as a point of departure to analyse the processes of interpretation and translation in the analysed texts (Ball, Citation2015). The texts display a variety of articulations on how the concept of scientific foundation could be understood in Swedish schools. In the texts, several related concepts are presented, among which the following four appear to be the most central: scientific foundation (vetenskaplig grund); proven experience (beprövad erfarenhet); evidence (evidens); and research-based way of working (forskningsbaserat arbetssätt). The centrality of these four concepts is emphasized in different ways in the texts, for example, by the four videos (embedded in two of the web pages) that explain and contextualize one concept each (NAE, National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019a, National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d).

The first two concepts, scientific foundation and proven experience, mirror the terms used in the Education Act (SFSCitation2010:800, 5§). Regarding the concept of a research-based way of working, the analysed texts do not refer to any outside references to define or contextualize the concept. When it comes to evidence, different sources for further explanations and contextualization of the concept are referred to (c.f. Bohlin & Sager, Citation2011; Levinsson, Citation2013, SOU 2009:94). Drawing on one of these sources, one of the policy texts constructs the concept of evidence as a hybrid between a top-down driven reform perspective (the teacher as consumer) and a bottom-up perspective (the teacher as producer) (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, pp. 12–13). In the policy texts, evidence is primarily presented as a naturally occurring concept in the educational field, albeit with an emphasis on the context-dependent character of the concept when used in the educational field in contrast to how it is used, e.g., in the medical field.

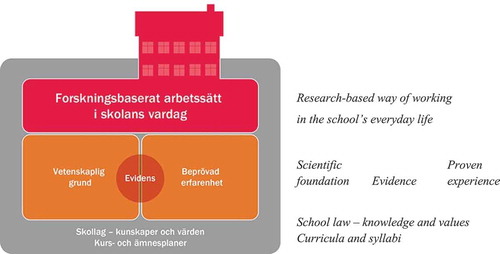

displays a graphic model that occurs in one of the texts. Here, the concept of research-based way of working is described as an overarching concept building on the other three concepts, while the concept of evidence is described as a combination of scientific foundation and proven experience (our translations on the right-hand side).

Figure 1 Model for a research-based way of working in everyday school life. (Source: NAE, Citation2019b.)

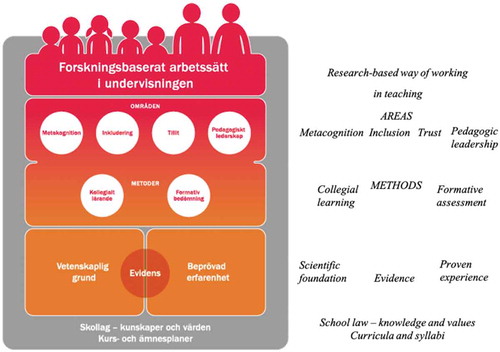

Figure 2 Model for a research-based way of working in teaching. (Source: NAE, Citation2019c.)

The model illustrates a policy-as-text interpretation where the Education Act’s formulation ‘the education shall rest on a scientific foundation and proven experience’ (SFS Citation2010:800) is materialized into a policy artefact (cf. Maguire et al., Citation2011). In the model, the policy concept research-based way of working appears to be an interpretation of the terms ‘the education’ in the Education Act – i.e. having the same function as the entity that rests on a scientific foundation and proven experience. In one of the videos, it is also explained that ‘through a research-based way of working it’s ensured that education rests on a scientific foundation and proven experience’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019a) which strengthens the impression of an equated meaning between the terms ‘the education’ from the Act and the policy concept research-based way of working in the analysed material. Furthermore, the brought-in policy concept of evidence is visualized and described – both in the model above and elsewhere in the analysed texts – as a concept that overlaps the terms ‘scientific foundation’ and ‘proven experience’. Thus, the Education Act’s dictum that the education shall rest on a scientific foundation and proven experience appears to be interpreted into policy-as-text prescribing that research-based way of working shall rest on evidence.

Discursive constructions of teacher professionalism in schools resting on a scientific foundation

In the following paragraphs, we take a policy-as-discourse perspective and present how teachers are constructed and positioned as professional subjects in and through the policy texts. Thus, we examine how the selected texts, rather than just describing how teachers could strive for a scientific foundation in their teaching, also mobilize claims of truth that shape the social reality of Swedish schools. Through discursive actions and technologies of performativity and accountability, the analysed texts enact different ideals of teacher professionalism, i.e. how teachers are constructed as professional subjects in schools that rests on a scientific foundation.

We will present three discursive policy constructions of teacher professionalism that we have thematized in and through the analysed policy texts. These discourses are not to be understood as isolated or independent of each other. On the contrary, the policy discourses overlap and interplay in the policy material, making teachers ‘what and who they are in the school and the classroom […] and what or who they can be’ (Ball et al., Citation2012, p. 92) – thereby enabling certain aspects of teacher professionalism while constraining others. The first discourse, titled the selectively critical and accountable teacher, has to do with teachers’ inward self-regulation, and constructs ideals of teacher beingness. A salient objective in this discourse is the affirmation of correct and effective practices outside individual intuition to avoid criticism and uncertainty. The second discursive construction of ideal teacher professionalism is the positive, flexible, responsible and effective teacher. This discourse constructs outward ideals of teacher doingness or performativity. This has to do with the actions teachers put forward and perform in their practice and how they enact local policy. Finally, the third discourse constructs ideals of the semi-autonomous teacher which reduces teachers’ individual agency by delegating teacher professionalism up the hierarchical chain and/or to organizational structures.

The selectively critical and accountable teacher

A professional ideal that emerges in the texts is the need for teachers to critically evaluate their own practice, exemplified in the following quote emphasizing that schools should honour ‘an approach that involves that the school personnel […] critically scrutinizes and evaluates their own work’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019c). In the same video, a teacher stresses that she and her colleagues ‘put greater demands on ourselves that we want to know what we really are doing – not just act on a feeling in the analysis, but cover our back and keep our feet dryFootnote8’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019a). A teacher in another video acknowledges that having a scientific foundation makes her more secure in her professional role: ‘I am not just standing there making something up, but I …, I do something and it’s a conscious choice – that I’m doing this’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d). In the same video, a head teacher emphasizes the importance for school personnel to ‘be able to feel secure that we don’t just do things – and we don’t do different things in every classroom either – rather we have a common base to stand on’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d). The excerpts construct teachers as self-critical professionals who avoid spontaneously acting on intuition. Instead, they are constructed as striving to affirm their didactic choices externally, e.g., by referring to research or other colleagues. In this way the discourse seems to undermine the legitimacy of individual teachers’ professional experience as a sufficient source for making didactic judgements.

As already illustrated above (when the head teacher highlights the benefits of having a similar practice in different classrooms) the texts also promote transparency among colleagues. Such transparency, i.e. that ‘you don’t just know what you are doing yourself, but also, what others are doing’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019a), comes across as both a resource for support and a technology of accountability in the policy material. Transparency between colleagues can inform teachers of the quality of their own teaching and facilitate professionally informed discussions about teaching practices that can serve to support, correct or improve teachers’ practice if needed. As illustrated in the following example, research and transparency between colleges can also aid as resources in dealing with professional uncertainty:

Now I know: it isn’t dangerous to reconsider and […] try new [things], while using something as a crutch that someone else has done. So, in that way I feel significantly safer as a teacher – and maybe therefore even a little better than I used to be. (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019a)

The texts emphasize in various ways that it is important that teachers ‘put it on the table and show other teachers’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d) – i.e. that they express and verbalize their individual tacit knowledge and contribute to a collegial experience – which adds to the notions of both accountability and performativity in the analysed texts (see also the second discourse).

In the data material, it is suggested that the implementation of a research-based approach in schools could help facilitate both teachers’ individual professionalism and the professionalization of teachers as a professional group. In these processes, the importance of a critical approach is argued for in different ways in the texts, as for example, when the meaning of science is explained:

To question and problematize is the engine of science. In the scientific approach, there is a desire to inspect and examine in a critical way, and to put individual facts into wider contexts. Problematizations of various kinds make room for discussion and open up new ways of looking upon reality. (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, p. 10)

The importance of scientific transparency in a research-based approach is highlighted in one of the videos, when an official at the NAE emphasizes how important it is that ‘another person can verify what [has been] said. Because that’s what is important with the scientific foundation, it is precisely that it is […] transparent’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d). In light of this statement in the material, it is contradictory that the analysed policy texts themselves often lack transparency or refer to eclectic sources in a non-transparent way. Throughout the analysed policy material, different claims and arguments are recurrently made without specifying supporting materials. In addition, when research or researchers are referenced in the policy texts, contesting or problematizing perspectives are usually absent, which makes it difficult for teachers to employ a critical attitude. Here, the descriptions of the concept of evidence in the data material serve as a good example. In one video, the speaker concludes that ‘In this context, there is also the concept of evidence’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d) while another text establishes that ‘[…] evidence-based practice is an increasingly common concept in the discussion of a scientific foundation and proven experience in the area of education’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, p. 12). Neither of these examples elaborates on the explanation further or gives any arguments for the applicability of the concept of evidence in educational contexts. Thus, the examples convey an impression of scientific consensus regarding the utility of evidence as a basic concept in research-based education, which does not disclose the fairly intense debate about the applicability of evidence as a concept in the educational field (cf. Alvunger & Wahlström, Citation2018; Hammersley, Citation1997; Biesta, Citation2010b; Levinsson, Citation2013; Liljestrand, Citation2014). That being said, in one of the videos, an uttering of an NAE official emphasizes:

Therefore, we can’t say that ‘the evidence-based doesn’t work, we will not use that […] in the area of education’. That we will never say! (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d).

This clarification of standpoint is one of the rare occasions that the texts reveal the existence of an epistemological debate concerning the concept of evidence and that its applicability is contested in the educational field.

The policy texts also recommend certain methods and approaches with little or no critical accounts. An example of this is the way that assessment for learning is presented as an evidence-based and effective method in the policy texts without addressing any critical perspectives. For example, when a researcher is drawn upon to justify assessment for learning as an effective evidence-based practice (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, p. 12), the parts of the referred research that problematize implementations of assessment for learning are left out except for a short passage commenting on teachers that expressed concerns about professional autonomy in the referred study. Another example, from the same policy text, is the way that inclusive teaching is described as a fairly universal concept, without discussing alternative perspectives in the complex body of knowledge that has been produced around this subject.

The analysed texts present few examples of teachers’ expressing a critical approach that expands beyond self-criticism or collegial criticism. Teachers and school leaders in the videos neither problematize nor critique the actual concepts of the policy apparatus, even if the challenges of implementing the different concepts are problematized to some extent. Although the analysed utterances and texts problematize and reflect upon how the concepts of the policy apparatus should be understood or implemented, the concepts themselves are not critically discussed – nor why they are brought in.

The positive, flexible, responsible and effective teacher

Policy excerpts clarifying that ‘an excellent teacher is a distinct leader of the learning taking place’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, p. 19) and that ‘the pupil should not be responsible for the actual learning’ (p. 68) illustrate the construction of a performative discourse of teacher professionalism in the material. By referring to well-known educational researchers, the policy material concludes that teachers’ ways of teaching determine successful learning outcomes to a higher degree than do economic or structural factors (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013). The material further underlines that teachers should ‘always bear the pupils’ goal attainment in mind’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, p. 32). The importance of not only knowing what works, but also knowing why it works is emphasized in the videos. For example, in one of the videos, a head teacher expresses the importance of becoming ‘more certain about what one is doing and what effects it has’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d). Furthermore, lessons that are spent on activities such as sharpening pencils or dealing with incidents during break time are referred to as representations of problems in the policy text, i.e. as distracting pupils from the necessary learning for goal attainment (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013). The examples serve to illustrate how the value of teachers’ ability to control and direct the learning of pupils towards goal attainment is emphasized throughout the analysed material.

The efforts to implement education resting on a scientific foundation are recurrently referred to with engagement and great enthusiasm by participating teachers and principals in the materials; in fact, three of the four videos end with some kind of enthusiastic exclamation or positive statement. The videos also construct teachers as professionals who constantly evaluate their teaching practice, striving to change it based on educational research. This is expressed, for example, when a teacher describes professional conduct:

It is structured and we document and we follow up and we … link research [to the teaching which] we critically … scrutinize [to identify which elements] there are based on the goals we have” (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d).

In another video, a research-based way of working is described as a tool for constantly changing practices in a systematized way:

We know what we do, we know why we do it, we know how we do [it] and we are incredibly good at following up; and if one follows up things then one can change [things] and be put in new “present-modes” and develop and constantly change (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019a).

In a similar argument in a third video, a head teacher expresses the value of having 'systematics in what you do, that is that we have a cycle' (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019d). The statements illustrate an ideal of cyclic quality management in Swedish education policy, constructing teachers and school leaders as professionals who regard the enactment of constant change as a prerequisite for qualitative teaching.

Taken together, the examples illustrate a discourse that promotes ideals of performativity (cf. Ball, Citation2003) – i.e. productivity, excellence and enthusiasm – for teachers striving to strengthen the scientific foundation in Swedish schools. This discourse constructs teachers as responsible for facilitating effective teaching that leads to effective learning and goal attainment for the pupils. Finally, the discourse subjectifies teachers as professionals who constantly evaluate their own teaching practices, adapting and changing them, while expressing a positive and enthusiastic attitude.

The semi-autonomous teacher

Although professional autonomy and a critical approach are emphasized as important parts of teacher professionalism, the texts also present contradicting formulations that construct a kind of professionalism that occasionally is appropriated from the individual teachers themselves and constructed as a form of delegated or outsourced professionalism. This is manifested in a number of ways, when the teachers’ latitude to make decisions solely based on their individual professional judgement is delimited. For example, in a section of one text specifying recommended methods or areas of teacher work that ‘are research-based, i.e. build on scientific foundation and proven experience’, six specifically important areas for a research-based way of working are described, with an added notion that the description should not be understood as the one and only correct answer (facit in Swedish)Footnote9 (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019c). Rather, the description in the text should be understood as ‘an illustration of areas that are important to relate to’ professionally. However, later in the same paragraph it is concluded that research-based teacher practice ‘must contain a combination of elements from these different areas’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019c), thereby prompting teachers to use the promoted methods or research in favour of other methods or epistemologies of their own choice. Contrary to this, other parts of the texts advocate a research-based teacher practice that combines didactic methods from a broad and flexible palette. Thus, the texts appear as somewhat ambivalent when it comes to autonomy and freedom of choice in teachers’ professional practices.

One of the listed areas of importance for a research-based approach is the area of pedagogical leadership.Footnote10 In one of the texts, this topic is described both in relation to teachers’ leadership in the classroom and in relation to school leadership and the management of teachers (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013). The text stresses the importance of teachers’ and pupils’ awareness of learning objectives and grading criteria, and suggests, by making reference to well-known researchers in the educational field, that head teachers need to prioritize the communication of policy documents to teachers and that ‘development plans are at least as important for the teachers as for the pupils’ (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2013, p. 74). By emphasizing the necessity for school leadership to steer teachers towards acknowledging their own professional responsibilities – at the same time as underlining the importance of monitoring teachers’ professional development – teachers are constructed as practitioners that need to be managed and professionalized by others. These examples of policy could be interpreted as expressing a lack of faith in teachers’ own professional judgement and expertise.

Another way in which the analysed texts contradict the notion of teachers as academic, independent and critically thinking professionals is by addressing the readers in a simplified way. Two examples of this are the previously shown graphic illustration of a research-based way of working in everyday school life (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019b) and a similar model of a research-based way of working in teaching (National Agency of Education (NAE), Citation2019c) shown below. The self-evident claims and the lack of problematizations in the data material (as mentioned earlier) also contribute to the discursive construction of teachers as an occupational group in need of simple explanations rather than as educated experts of a professional domain.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to analyse how education on a scientific foundation, as described in the Education Act (SFS Citation2010:800, §5), is enacted in policy texts by the Swedish National Agency of Education (NAE), and how teacher professionalism is discursively constructed in these texts. The result shows how the formulation concerning scientific foundation in the Education Act is interpreted and enacted into policy-as-text prescribing that a research-based way of working shall rest on evidence. Also, the policy texts construct three discursive constructions of teacher professionalism: the selectively critical and accountable teacher, the positive, flexible, responsible and effective teacher, and the semi-autonomous teacher.

The idea that educational practices can, and should, be strengthened by research has a long history and is well established both in Sweden and internationally (SOU Citation1948:27, Citation1999:63; OECD, Citation2005, Citation2015). Previous research shows how state policy initiatives during the last decade have recognized the need for educational research, with an emphasis on the need for practice-based research, as an important factor for the academization of Swedish teachers in the same way as, e.g., in the field of medicine. The purpose of the academization is to strengthen the quality of teaching and schooling, but also to strengthen the teacher profession (cf. SOU Citation1999:63; Carlgren, Citation1999; Darling-Hammond, Citation2000). However, research also shows that such processes, initiated by politicians and policy makers, position teachers mainly as consumers of research (Levinsson, Citation2013). Thus, without an epistemic culture of its own, the Swedish teacher profession risks becoming an object of research-based initiatives instead of a driving force behind research-based development of educational practices in Swedish schools (Carlgren, Citation2010, Citation2018).

Our result shows that the lack of transparency and alternative epistemic perspectives in the analysed policy texts regulates the scopes and directions of teachers’ critical thinking, rather than promoting critically informed educational experts with their own epistemic culture. In this way, the policy texts construct teachers as uncritical enactors of epistemic theories and methodologies devised elsewhere, i.e. as consumers of science and deliverers of educational services. Hence, the texts risk promoting a reduction of complexities and a top-down regulation of teachers’ epistemological agency and professional judgement, rather than facilitating an expansion of teachers’ professional expertise (cf. Biesta, Citation2010a, Citation2010b).

Although the analysed texts give some examples of research-based conduct in specific (albeit oftentimes PISA-related) subjects, research-based teacher professionalism is mostly enacted as independent of both the subject and the age group being taught. Thus, examples of research-based conduct that addresses specific pedagogic(al) challenges in e.g., vocational or practical-aesthetic subjects are not accounted for in the analysed policy texts. In this way a scientifically founded professionalism – or a research-based way of working – is constructed as a generic professionalism. Through such constructions in the texts, teachers’ professional judgement and knowledge become restructured as de-contextualized commodities, following neoliberal rationales to reduce uncertainty of outcomes (cf. Ball, Citation2007). Hence, the teachers themselves are positioned as replaceable deliverers of educational services rather than as academic experts with professional autonomy (Hansson & Erixon, Citation2020; Liljestrand, Citation2014; Stenlås, Citation2011).

Following our result and results from previous research, we finally argue that, unlike today’s practice, policy initiatives for a scientific foundation in education need to provide the time and organizational resources for every teacher to develop, refine and maintain an informed and autonomous scientific critique to relevant research (cf. Åman & Kroksmark, Citation2018; Bergmark & Hansson, Citation2020; Levinsson, Citation2013). Hence, the development of a research-based professionalism cannot be a top-down implemented endeavour, but rather differentiated bottom-up processes for teachers of particular subject areas or age groups (Carlgren, Citation2010, Citation2018). Furthermore, the professional agency of deploying such critique should also encompass research disseminated by educational policy actors. Moreover, for teachers to develop such epistemic cultures, an ongoing academic conversation needs to be facilitated among teachers in Swedish schools and teacher education needs to prepare teacher students for taking part in such conversation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. In Swedish: ”Utbildningen ska vila på vetenskaplig grund och beprövad erfarenhet.” This study focuses on the first part of the sentence, i.e. the intention to ensure that Swedish schools provide research-based education. (The English translation follows the example of Bergmark & Hansson, Citation2020.)

2. ULF is a project that facilitates collaborative educational research between Swedish Universities and local schools.

3. Professionality is another word that is used for the same purpose.

4. The graphic models displayed in the article were created in 2014 by the Swedish National Agency of Education (NAE). These models are no longer displayed on their website, as the NAE have made changes to their definitions of the concepts of scientific foundation and proven experience.

5. This was probably due to the non-use of Boolean operators such as ‘AND’ in the search string.

6. The search also yielded a few pages that were either identical (e.g., identical syllabi for courses given both in upper secondary and adult education) or did not include any variation of words in the search string.

7. All excerpts presented in the article are translated from Swedish.

8. The last part of the excerpt is a Swedish saying describing an attempt to ensure that everything is done according to what can be expected or has been demanded, in order to avoid the risk of criticism.

9. Facit is the Swedish term for an answer key, a list of correct answers that pupils/students can look up, e.g., in the back of their schoolbooks.

10. The other areas are metacognition and self-regulated learning; inclusion; trust; formative assessment; and peer learning (kollegialt lärande in Swedish). (See also the model for a research-based way of working in teaching (Fig. 2).)

References

- Aasen, P., & Prøitz, T. (2004). Initiering, finansiering och förvaltning av praxisnära forskning: Sektorsmyndighetens roll i svensk utbildningsforskning. NIFU.

- Adolfsson, C.-H., & Sundberg, D. (2018). Att forskningsbasera den svenska skolan: Policyinitiativ under 25 år. Pedagogisk Forskning I Sverige, 23(1–2), 39–63. https://open.lnu.se/index.php/PFS/article/view/1469

- Alvunger, D., & Wahlström, N. (Eds.). (2018). Den evidensbaserade skolan: Svensk skola i skärningspunkten mellan forskning och praktik. Natur & kultur.

- Åman, P., & Kroksmark, T. (2018). Lärares uppfattningar av begreppet vetenskaplig grund. Nordic Studies in Education, 38(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.18261/.1891-5949-2018-03-02

- Åman, P. & Kroksmark, T. (2018). Forskning i skolan – forskande lärare. Nordic Studies in Education 38(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-5949

- Bacchi, C. (2000). Policy as Discourse: What does it mean? Where does it get us? Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 21(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596300050005493

- Bacchi, C. (2009). Analysing policy: What’s the problem represented to be? Pearson.

- Ball, S. J. (1993). WHAT IS POLICY? TEXTS, TRAJECTORIES AND TOOLBOXES. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 13(2), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0159630930130203

- Ball, S. J. (2000). Performativities and fabrications in the education economy: Towards the performative society? The Australian Educational Researcher, 27(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03219719

- Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

- Ball, S. J. (2007). Education plc: Understanding private sector participation in public sector education. London. Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. (2015). What is policy? 21 years later: Reflections on the possibilities of policy research. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 36(3), 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1015279

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. Routledge.

- Ben-Peretz, M. (2011). Teacher knowledge: What is it? How do we uncover it? What are its implications for schooling? Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.015

- Bergmark, U., & Hansson, K. (2020). How teachers and principals enact the policy of building education in sweden on a scientific foundation and proven experience: Challenges and opportunities. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1713883

- Biesta, G. (2010a). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Paradigm Publishers.

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2010b). why ‘what works’ still won’t work: From evidence-based education to value-based education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 29(5), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-010-9191-x

- Bohlin, I., & Sager, M. (2011). Evidensens många ansikten: Evidensbaserad praktik i praktiken. (red.). Arkiv.

- Carlgren, I. (1999). Professionalism and teachers as designers. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/002202799183287

- Carlgren, I. (2010). Den felande länken. Om frånvaron och behovet av klinisk utbildningsvetenskaplig forskning. Pedagogisk Forskning I Sverige, 15(4), 295–306.

- Carlgren, I. (2018). Pedagogiken och lärarna. Pedagogisk Forskning I Sverige, 23(5), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.15626/pfs23.5.15

- Commission of the European Communities (CEC). (2000). The lisbon european council: an agenda for economic and social renewal in Europe. Brussels: Directorate General Education and Culture. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/summits/lis1_en.htm

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

- Dovemark, M., Kosunen, S., Kauko, J., Magnúsdóttir, B., Hansen, P., & Rasmussen, P. (2018). Deregulation, privatisation and marketisation of Nordic comprehensive education: Social changes reflected in schooling. Education Inquiry, 9(1), 122–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2018.1429768

- Englund, T., & Solbrekke, T. D. (2015). Om innebörder i lärarprofessionalism. Pedagogisk Forskning I Sverige, 20(3–4), 27.

- Ensor, P. (2004). Modalities of teacher education discourse and the education of effective practitioners. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 12(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360400200197

- Foucault, M. (1981). The order of discourse. In R. Young (Ed.), Untying the text: A post-structuralist reader, pp. 48-78. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Foucault, M. (1986). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Tavistock Publications.

- Frostenson, M. (2015). Three forms of professional autonomy: De-professionalisation of teachers in a new light. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, (2015(2). https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.28464

- Grek, S. (2009). Governing by numbers: The PISA ‘effect’ in Europe. Journal of Education Policy, 24(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802412669

- Hammersley, M. (1997). Educational research and teaching: A response to david hargreaves’ TTA lecture. British Educational Research Journal, 23(2), 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192970230203

- Hansson, K., & Erixon, P.-O. (2020). Academisation and teachers’ dilemmas. European Educational Research Journal, 19(4), 289–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904119872935

- Högskoleförordningen (HF 1977:263). Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet

- Krejsler, J. B. (2013). What works in education and social welfare? A mapping of the evidence discourse and reflections upon consequences for professionals. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.621141

- Kroksmark, T. (2013). De stora frågorna om skolan. Studentlitteratur.

- Levinsson, M. (2013). Evidens och existens evidensbaserad undervisning i ljuset av lärares erfarenheter. Göteborg: Acta universitatis Gothoburgensis. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/32807

- Liljestrand, J. (2014). Teacher education for democratic participation: the need for teacher judgement in times of evidence-based teaching. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 13(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.2304/csee.2014.13.3.175

- Lindblad, S. (1997). Imposed professionalization: on teacher´s work and experiences of deregulation of education in Sweden. In I. Nilsson & L. Lundahl (Eds.), Teachers, curriculum and policy : Critical perspectives in educational research, pp.133-148. Umeå: Umeå University Press.

- Lindqvist, P., & Nordänger, U.-K. (2007). ”Lost in translation?” Om relationen mellan lärares praktiska kunnande och professionella språk. Pedagogisk Forskning I Sverige, 12(3), 177–193.

- Lundahl, C., & Serder, M. (2020). Is PISA more important to school reforms than educational research? The selective use of authoritative references in media and in parliamentary debates. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1831306

- Lundström, U. (2015). Teacher autonomy in the era of new public management. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, (2015(2). https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.28144

- Maguire, M., Hoskins, K., Ball, S., & Braun, A. (2011). Policy discourses in school texts. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2011.601556

- National Agency of Education (NAE). (2013). Forskning för klassrummet: Vetenskaplig grund och beprövad erfarenhet i praktiken. Skolverket.

- National Agency of Education (NAE). (2019a). Att arbeta forskningsbaserat. Retrieved 06/April/2019 from https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-utvarderingar/forskningsbaserat-arbetssatt/att-arbeta-forskningsbaserat

- National Agency of Education (NAE). (2019b). Forskningsbaserat arbetssätt för ökad kvalitet i skolan. Retrieved 12/March/2019 from https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-utvarderingar/forskningsbaserat-arbetssatt/forskningsbaserat-arbetssatt-for-okad-kvalitet-i-skolan

- National Agency of Education (NAE). (2019c). Forskningsbaserat arbetssätt i undervisningen. Retrieved 06/April/2019 from https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-utvarderingar/forskningsbaserat-arbetssatt/forskningsbaserat-arbetssatt-i-undervisningen

- National Agency of Education (NAE) (2019d). Forskningsbaserat arbetssätt, några nyckelbegrepp. Retrieved 13/March/2019 from https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-utvarderingar/forskningsbaserat-arbetssatt/forskningsbaserat-arbetssatt-nagra-nyckelbegrepp

- Nordin, A. (2014). Crisis as a discursive legitimation strategy in educational reforms: A critical policy analysis. Education Inquiry, 5(1), 24047. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v5.24047

- OECD. (2005). Teachers matter: Attracting, developing and retaining effective teachers.

- OECD. (2015). Improving schools in sweden: An OECD-perspective. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/Improving-Schools-in-Sweden.pdf

- OECD. (2018). Teaching in Focus. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/teachinginfocus.htm

- Ozga, J., Seddon, T., & Popkewitz, T. S. (2006). Education research and policy: steering the knowledge-based economy. London. Routledge.

- Persson, A., & Persson, J. (2017). Vetenskaplig grund och beprövad erfarenhet i högre utbildning och skola. I Vetenskap och beprövad erfarenhet – skola. Lund University. https://www.vbe.lu.se/sites/vbe.lu.se.en/files/vbe_skola_for_webb.pdf

- Petersen, E. B. (2015). What crisis of representation? Challenging the realism of post-structuralist policy research in education. Critical Studies in Education, 56(1), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2015.983940

- Prop 1989/9041). Om kommunalt huvudmannaskap för lärare, skolledare, biträdande skolledare och syofunktionärer. regeringen.

- Prop 2009/10:165. Den nya skollagen – För kunskap, valfrihet och trygghet. Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Rapp, S., Segolsson, M., & Kroksmark, T. (2017). The education act : Conditions for a research-based school a frame-factor theoretical thinking. International Journal of Research and Education, 2(2), 1–13.

- Ringarp, J. (2016). PISA lends legitimacy: A study of education policy changes in Germany and Sweden after 2000. European Educational Research Journal, 15(4), 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116630754

- Schleicher, A. (2016). Teaching excellence through professional learning and policy reform: Lessons from around the world. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252059-en

- Serder, M. (2015). Möte med PISA. Malmö Högskola.

- SFS2010:800. Skollagen. Utbildningsdepartementet.

- SOU 1948:27. 1946 års skolkommissions betänkande med förslag på riktlinjer för det svenska skolväsendets utveckling. Ecklesiastikdepartementet.

- SOU 1961: 30. 1957 års skolberedning. Ecklesiastikdepartementet.

- SOU 1999:3. Att lära och leda. En lärarutbildning för samverkan och utveckling. Fritzes.

- SOU 2005:31. Stödet till utbildningsvetenskaplig forskning. Utbildningsdepartementet.

- SOU 2008:109. En hållbar lärarutbildning. Fritzes.

- SOU 2018:19. Forska tillsammans – Samverkan för lärande och förbättring. Fritzes.

- Star, S., & Grieshemer, J. R. (1989). Ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

- Stenlås, N. (2011). Läraryrket mellan autonomi och statliga reformideologier. Arbetsmarknad & Arbetsliv, 17(4), 11–27.

- Stigler, J., & Hiebert, J. (1999). The teaching gap. Best ideas from the world’s teachers for improving education in the classroom. The Free Press.

- Wennergren, A.-C., & Åman, P. (2011). Vägar till en skola på vetenskaplig grund. Didaktisk Tidskrift, 20(4), 207–230.