ABSTRACT

This article addresses teacher autonomy in different models of educational governance using quantitative data from the OECD TALIS 2018 and qualitative data from a study on teacher autonomy conducted in Norway and Brazil. In this article, teacher autonomy is seen as a multidimensional concept referring to decision-making and control in relation to state governance. Further, the different degrees of implementation of accountability measures across countries determine the models of educational governance. The quantitative data reveals no clear pattern between teacher autonomy and models of educational governance. In general, teachers perceive that they have good control over teaching and planning at the classroom level. However, teachers report that they participate to a lesser degree in professional collaboration in schools, which could allow for collegial teacher autonomy. Teachers also report low perceived social value and policy influence, which may provide insight into professional teacher autonomy at the policy level. This article also shows the relevance of a detailed description of the country cases to gain a better understanding of the multiple dimensions of teacher autonomy.

Introduction

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and its Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) have triggered lively public debates, often facilitated by the media, on the quality and effectiveness of education systems. Several countries have implemented significant changes in their education systems in connection with PISA (Grek, Citation2009; Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2003). In addition to PISA, the OECD produces other publications and surveys, such as the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS).

Since its first cycle in 2008, TALIS has collected information on teachers and teaching at the teacher, school, and education-system levels every five years (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2019, Citation2020). The most recent cycle of TALIS in 2018 covered about 260,000 teachers in 15,000 schools across 48 countries. According to the OECD, TALIS provides data on teacher characteristics, pedagogical practices, and working environments with the aim of facilitating the comparison of practices and policies between countries and, consequently, the improvement of educational quality and effectiveness (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2019, Citation2020).

In fact, the OECD provides countries not only with comparable data, but also with a global discourse concerning the role of teachers in raising performance standards (Pettersson & Mølstad, Citation2016; Sørensen, Citation2017). Research literature on educational governance has addressed the influence of the OECD and PISA, finding that national governments have implemented large-scale accountability instruments ‘to monitor teachers’ performance and promote competitive pressures among schools’ (Verger et al., Citation2019, p. 249). In this educational governance environment, teacher autonomy is challenged by accountability instruments, such as national standards, high-stakes testing, league tables, indicators, inspections, incentives, and sanctions resulting from performance data (Högberg & Lindgren, Citation2020; Verger et al., Citation2019).

In addition to the OECD’s discourse on teachers and teaching, national and local actors and contexts also frame the teaching profession, which brings national, regional, and local variations that often characterize the field of comparative education (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2014). For example, teachers may perceive constrained autonomy in countries with extensive production of standardized performance data, several forms of evaluation, and high incentives and sanctions resulting from this evaluation (Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019). In contrast, teachers may perceive extended autonomy in countries featuring low or absent production of standardized performance data, few or uneven forms of evaluation, and no incentives and sanctions resulting from this evaluation (Mausethagen, Citation2013; Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019).

In this vein, this article aims to compare teachers’ perceptions of their autonomy in different models of educational governance using quantitative data from TALIS 2018 and qualitative data from a study on teacher autonomy conducted in lower secondary education in Norway and Brazil in 2018. This study asks whether a high degree of educational accountability correlates with a low degree of teacher perceived autonomy, and vice versa.

The 2018 survey marked the first time TALIS measured teacher autonomy (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2019). Moreover, the larger amount of collected data, which is publicly available, allows researchers to compare teachers’ perceptions of their autonomy across several countries.

Alongside the TALIS data, this study includes qualitative data from Norway and Brazil. The countries are interesting to compare more deeply because of recent education reforms. Both countries have adopted test-based accountability systems in the 2000s in response to PISA, as indicated by research literature on Norway (Camphuijsen et al., Citation2020; Imsen & Volckmar, Citation2014; Karseth & Sivesind, Citation2011; Mausethagen & Mølstad, Citation2015) and Brazil (Barreto, Citation2012; Therrien & Loiola, Citation2001; Villani & Oliveira, Citation2018). However, these countries show differences in their test-based accountability systems. Brazil can be classified as a high-stakes accountability system (Högberg & Lindgren, Citation2020; Verger et al., Citation2019) based on its strict accountability measures, such as target setting with bonus payments for schools and teachers that achieve performance targets. Norway can be classified as a low-stakes accountability system (Högberg & Lindgren, Citation2020; Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019), mainly because testing results are not connected to monetary incentives and sanction mechanisms in relation to teachers’ work (Mausethagen, Citation2013). These countries also represent different cultural and economic positions. Accordingly, while Norway can be placed within the scope of European and rich countries, Brazil can be placed within Latin-American and developing countries.

This article is structured in the following way. The next section presents the theoretical background for this study and examines (a) teacher autonomy as a complex and multidimensional phenomenon referring to decision-making and control in relation to state governance and (b) different models of educational governance reflecting different spaces for teacher autonomy. Building on the theoretical background, the next section describes the quantitative and qualitative data approaches and sources. Then, the results of the quantitative and qualitative data are presented, followed by a discussion of the study’s results, and concluding remarks.

Theoretical background

The multidimensionality of teacher autonomy

This article approaches teacher autonomy regarding decision-making and control in relation to educational governance, without ignoring the wide variety of definitions of teacher autonomy (cf. Wilches, Citation2007) and perspectives from which to examine this concept (e.g. Aoki & Hamakawa, Citation2003; Cohen, Citation2016). Teacher autonomy within a governance perspective refers to the capacity of teachers to make informed judgements and decisions that affect their work and roles within a frame of regulations and resources provided by the state (Frostenson, Citation2015; Mausethagen & Mølstad, Citation2015; Wermke & Forsberg, Citation2017; Wermke & Höstfält, Citation2014; Wermke et al., Citation2019).

From a governance perspective, studies investigate decision-making at different levels, such as individual, collegial, and professional levels. According to Frostenson (Citation2015), general professional autonomy of the teaching profession consists of teachers acting as a professional group or organization to decide on the framing of their work, for example, through influencing the general organization of the school system, legislation, entry requirements, teacher education, curricula, procedures, and ideologies of control (p. 22). In contrast, Frostenson (Citation2015) defines collegial professional autonomy in the teaching profession as teachers’ collective freedom to influence and decide on practice at the school level, while individual autonomy is the individual’s opportunity to influence the contents, frames, and controls of the teaching practice (pp. 23–24).

Bergh (Citation2015) and Frostenson (Citation2015) note that teacher autonomy at the collegial level can influence teacher autonomy at the individual level. For example, school administration may require teachers to collaborate, or teachers may choose to collaborate based on circumstances, which can result in increased collegial autonomy in shaping the contents and forms of the teaching practice (Frostenson, Citation2015, p. 23). Moreover, collegial autonomy may coexist with individual autonomy, particularly when collegial work is a result of the preferences and pedagogical ideals of individual teachers (Frostenson, Citation2015, p. 24). Vangrieken and Kyndt (Citation2019) observe that younger teachers perceive professional collaboration as meaningful and contributing to their individual autonomy in classrooms, which indicates a collaborative autonomy in which teacher autonomy is combined with a collaborative attitude (p. 196).

Therefore, the relation between collegial and individual teacher autonomy is an interesting avenue of research, as the exercise of collegial teacher autonomy can either extend or work against individual teacher autonomy (Elo & Nygren‑Landgärds, Citation2020; Frostenson, Citation2015; Kelchtermans, Citation2006). The exercise of collegial teacher autonomy can also be teacher-driven or mandated by the school leadership, which relates to the concept of contrived collegiality. This concept refers to administratively contrived interactions among teachers where they meet and work to implement the curricula and strategies developed by others, enhancing administrative control while constraining individual teacher autonomy (Hargreaves, Citation1994; Hargreaves & Dawe, Citation1990).

In a comparative study between Norwegian and Swedish teachers, Helgøy and Homme (Citation2007) show that Norwegian teachers adopt a more collaborative attitude than their Swedish counterparts. According to Helgøy and Homme (Citation2007), the Swedish teachers persist with traditional classroom teaching. Recent studies on teacher autonomy in Sweden also describe school leadership as being the ones to set goals, allocate resources, and create timetables, while teachers choose individually how to reach these goals (Wermke & Forsberg, Citation2017; Wermke et al., Citation2019).

This finding also applies to other countries where teacher autonomy often denotes the autonomy of an actor to determine how to reach specified goals or standards that the actor is held accountable for, which is a very narrow and instrumental understanding of teacher autonomy (see Ball, Citation2003). For example, Dias (Citation2018) observes that Brazilian teachers perceive collegial work not as a form of collective reflection and collaboration but as a form of mutual vigilance and control that pushes them to comply with performance demands.

In a comparative study of interviews in Estonia, Finland, and Germany (Bavaria), Erss et al. (Citation2016) argue that curriculum policy has promised increased autonomy to teachers. However, as the cases of Bavarian and Estonian curricula show, the autonomy-stressing rhetoric of the curriculum is accompanied by teachers’ perceived lack of autonomy. Bavarian and Estonian teachers perceive low social status and lack of involvement in educational decision-making as negatively affecting their sense of autonomy. By contrast, the Finnish teachers refer to their high sense of professionalism to take control over decision-making regarding instruction and curriculum content.

The different levels of teacher autonomy – individual, collegial, and professional – will assist in the presentation of the study’s quantitative and qualitative results.

Models of educational governance

This section presents countries with different models of educational governance related to the implementation of test-based accountability systems. Studies have addressed educational governance from different perspectives.

For example, Wermke and Prøitz (Citation2019) present a framework based on approaches to education in terms of emphasis on input or output and/or variations in long-standing traditions in curriculum development. These traditions are characterized by a dichotomous division between an Anglo-American curriculum tradition and a German/European continental tradition of Didaktik. The former approach focuses on the governing of education by results or outcomes, as seen in countries like the USA and England (UK). The latter focuses on the governing of education by its processes or inputs, such as the implementation of a centralized standardized curriculum and state-regulated entrance into the teaching profession, as represented by countries such as Germany, Norway, and Finland.

Hopmann (Citation2015) highlights the points of contact between the continental European tradition of Didaktik and the Anglo-American tradition of curriculum. He argues that continental European education systems have adopted the test culture of Anglo-American countries and that, in turn, Anglo-American countries have adopted quality control strategies such as state-based curricular formats of European countries. According to Hopmann (Citation2015), these encounters have increased accountability and pressure on schools, teachers, and students in European and Anglo-American countries.

In a literature review, Verger et al. (Citation2019) confirm the adoption of test-based accountability systems in European countries. Verger et al. (Citation2019) examine the rationales and trajectories of the adoption of national large-scale assessments and test-based accountability systems in countries with different governance traditions. In their division, Liberal states have a liberal organization of the state and high-stakes accountability instruments; Neo-Weberian states have a welfare state model of organization and low-stakes accountability instruments; and Napoleonic states have centralized, hierarchical, and uniform bureaucracies alongside uneven and highly contested accountability instruments.

Similarly, Högberg and Lindgren (Citation2020) explore the diffusion of accountability across OECD countries by using PISA data. They categorize the countries as those with ‘thick horizontal’, ‘thick vertical’, and ‘thin accountability’. Countries with ‘thick accountability’ have high production of standardized performance data, several forms of evaluation by external parties, and high incentives and sanctions resulting from this evaluation. Countries with ‘thick horizontal accountability’ feature decentralized decision-making, with the involvement of multiple stakeholders (e.g. parents and the public). By ‘thick vertical accountability’, they refer to educational authorities as the main actors controlling teachers’ work. In contrast, countries with ‘thin accountability’ have low production of standardized performance data, few forms of evaluation by external parties, and no incentives and sanctions resulting from this evaluation.

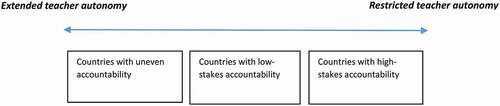

This article uses the terms high-stakes, low-stakes, and uneven accountability to adequately capture the study’s data. High-stakes accountability countries have high production of standardized performance data, several forms of evaluation by external parties, and high incentives and sanctions resulting from this evaluation (Högberg & Lindgren, Citation2020; Verger et al., Citation2019). Low-stakes accountability countries have almost the same features as high-stakes countries, but they do not have incentives and sanctions resulting from evaluation by external parties (Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019). Countries with uneven accountability have irregularly implemented accountability due to political contestation and economic junctures (Verger et al., Citation2019). The following paragraphs present the categories and countries described by Verger et al. (Citation2019) and, when possible, include empirical studies connected to other countries.

According to Verger et al. (Citation2019), the first model of educational governance includes countries with a liberal organization of the state, such as the one prevailing in most Anglo-Saxon countries (e.g. USA, UK, New Zealand), in which there is a great participation of the private sector in public services and intense forms of competition between providers. These countries generally adopt accountability measures to expand market competition and choice. Wermke and Prøitz (Citation2019) explain that, in this group of countries, the state governs education by focusing on results or outcomes.

Verger et al. (Citation2019) observe that these liberal countries can be divided into early and late adopters. The former category introduced governance reforms with accountability measures in the context of the global economic crisis of the 1970s (e.g. UK and Chile), while the latter (e.g. USA) strategically combined discourses on competitiveness and choice with discourses about ethnic and socioeconomic equity and the reduction of achievement gaps to pass educational reforms based on accountability in the 2000s. According to Verger et al. (Citation2019), the states in this group have justified educational reforms based on mistrust in teachers and teachers’ unions and a discourse on public schooling failures and low-quality education in the public sector. Accordingly, national large-scale assessments and test-based accountability instruments appear as policy instruments with the aim of increasing state control over schools and teachers, thus constraining teacher autonomy.

Brazil is included in this category because this country has adopted open-market and privatization measures in education to reduce costs and increase the efficiency of education (Dias, Citation2018; Lennert da Silva & Mølstad, Citation2020). These changes have resulted from discourse on reducing inequalities and ensuring quality education for all (Lennert da Silva & Parish, Citation2020). The Slovak Republic (Tesar et al., Citation2017) and Estonia (Keskula et al., Citation2012) are also in this group since these countries show high production of standardized performance data, several forms of evaluation by external parties, and high incentives and sanctions resulting from this evaluation. Sweden, despite being a Northern European country with a welfare state governance model, is also included in this group. This country has embraced more openly the marketization of education, with the introduction of private schools, school choice, and school autonomy, while implementing strong externally regulated standards and measurements (Frostenson, Citation2015; Wermke et al., Citation2019).

According to Verger et al. (Citation2019), the second model of educational governance is most prevalent in continental and Northern Europe (e.g. Denmark, Norway, Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands). Wermke and Prøitz (Citation2019) observe this group of countries control education through processes or inputs centrally defined by the state. In this model, the state acts as ‘a facilitator of solutions to social problems and is eager to preserve the ideas of civil service and professionalism in public services’ (Verger et al., Citation2019, p. 251). Some countries initially chose national large-scale assessments as a way for the central state to guarantee quality standards in the context of highly decentralized education systems and make services more responsive to citizens’ demands. However, unexpectedly low PISA results reinforced the need for increasing accountability measures as a way to improve students’ learning outcomes in a scenario of international competition, as in the case of Norway (Karseth & Sivesind, Citation2011) and Germany (Erss, Citation2018; Grek, Citation2009; Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2003). Despite the emphasis on accountability as a consequence of the PISA, the accountability systems adopted in these countries were predominantly low stakes (Mausethagen, Citation2013; Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019).

This article adds some more countries to the review by Verger et al. (Citation2019). Despite its outstanding PISA results, Finland is included in this second group. Finnish teachers are held accountable for final examinations at the upper secondary level and have a great sense of responsibility related to their professional belonging (Elo & Nygren‑Landgärds, Citation2020; Erss, Citation2018; Wermke & Höstfält, Citation2014). This article also includes Japan (Bjork, Citation2009) and Turkey (Hammersley-Fletcher et al., Citation2020) in this group since these countries have fewer forms of evaluation by external parties in comparison with high-stakes accountability countries; in addition, these countries offer no incentives or sanctions resulting from this evaluation.

Finally, the third model presented by Verger et al. (Citation2019) includes mostly Southern European countries, characterized by centralized, hierarchical, and uniform bureaucracies (e.g. Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain). In these countries, the implementation of accountability measures has been uneven and highly conditioned by political contestation and economic junctures (Day et al., Citation2007; Verger et al., Citation2019). Verger et al. (Citation2019) explain that these countries have a long legacy of democratic and horizontal educational governance as a reaction to decades of authoritarian regimes. Teachers’ unions are combative and participative in educational debates. Therefore, most teachers have civil servant status and enjoy high levels of autonomy. South Africa is included in this group since teachers contest accountability policies due to a troubled history of the apartheid inspection system that provoked deep-rooted suspicions of state surveillance even under the terms of a new democracy (Jansen, Citation2004; Shalem et al., Citation2018). In this case, teachers are still fighting for their autonomy (Jansen, Citation2004).

In summary, this article borrows the categories for educational governance models from Verger et al. (Citation2019). Accordingly, high-stakes accountability countries have high production of standardized performance data, several forms of evaluation by external parties, and high incentives and sanctions resulting from this evaluation (Högberg & Lindgren, Citation2020; Verger et al., Citation2019). Low-stakes accountability countries have almost the same features as high-stakes countries, but they do not have incentives and sanctions resulting from evaluation by external parties (Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019). Countries with uneven accountability have irregularly implemented accountability because of political contestation and economic junctures (Verger et al., Citation2019). These three categories related to the models of educational governance (i.e. high-stakes, low-stakes, and uneven accountability) assisted in the selection of the sample of countries for the quantitative analysis.

Methods

As advocated by comparative education researchers, quantitative studies can benefit from qualitative studies that investigate the rich diversity at the lower levels of the state, district/county, school, classroom, and individual, thereby giving balance, depth, and completeness to these studies. Similarly, micro-level qualitative work can be informed by the quantitative contributions from large-scale cross-national comparative studies (Manzon, Citation2014). In this article, the quantitative data sources enable an examination of teachers’ perceptions of their autonomy from a bird’s-eye view encompassing many countries. Moreover, the qualitative data sources privilege the detailed description of teachers’ contexts and perceptions of their autonomy. The next sections describe in more detail the quantitative and qualitative approaches used in this article.

Quantitative approach

This article works with the sampling, sources of data, operationalization, and measurement of variables of the OECD’s TALIS 2018. The secondary data sources are as follows:

TALIS 2018 Database. http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis-2018-data.htm. This database contains files in SAS, SPSS, and STATA formats.

OECD (Citation2019). TALIS 2018 Technical Report. OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS_2018_Technical_Report.pdf. This technical report details the steps, procedures, methodologies, standards, and rules that TALIS 2018 used to collect data. The primary purpose of the report is to support its readers and users of the public international database when interpreting results, contextualizing information, and utilizing the data.

According to Cohen et al. (Citation2018), some advantages of using secondary data are that the scale, scope, and amount of data are usually much larger and more representative than a single researcher could gather. The researcher does not face the challenges of collecting a larger amount of data, such as financing the data collection, spending time to collect data, gaining access to people, and obtaining permission from gatekeepers. Secondary data is often low-cost or even free to access and immediately accessible, typically without following many rigid procedures (pp. 587–588). This is the case for this article since TALIS data is publicly available and free of charge.

However, Cohen et al. (Citation2018) point out some challenges in using secondary data. For instance, the data may not be a perfect fit to the conceptual framework of a specific study (Cohen et al., Citation2018, p. 588), as is the case for this article. TALIS 2018 works mainly with the concept of individual teacher autonomy measured by the scale ‘satisfaction with classroom autonomy’. With the aim of including the other levels of teacher autonomy, this article has borrowed from TALIS 2018 the scale ‘professional collaboration in lessons among teachers’ to measure collegial teacher autonomy and the scale ‘perceptions of value and policy influence’ to measure professional teacher autonomy. Although these scales measure central elements of each level of teacher autonomy, they do present limitations. Before describing these limitations, this article presents the questions and items that comprise the scales representing the three levels of teacher autonomy:

Scale satisfaction with classroom autonomy: TALIS asked teachers to use a four-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) to rate the extent to which they agree they have autonomy in addressing the following items: ‘determining course content,’ ‘selecting teaching methods,’ ‘assessing students’ learning,’ ‘disciplining students,’ and ‘determining the amount of homework to be assigned.’

Scale professional collaboration in lessons among teachers: TALIS asked teachers about their perceptions of the frequency of professional collaboration in lessons among teachers. Each item required teachers to respond using a six-point Likert scale (1 = never, 6 = once a week or more). The items were ‘teach jointly as a team in the same class,’ ‘provide feedback to other teachers about their practice,’ ‘engage in joint activities across different classes and age groups (e.g. projects),’ and ‘participate in collaborative professional learning.’

Scale perceptions of value and policy influence: This scale from TALIS measured to what extent teachers agreed with the following items according to a four-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). These were ‘teachers’ views are valued by policymakers in this country/region,’ ‘teachers can influence educational policy in this country/region,’ and ‘teachers are valued by the media in this country/region.’

Regarding the scale ‘satisfaction with classroom autonomy’, this scale assessed mainly teachers’ decision-making and control over the educational and social domains. It did not include questions related to the professional development of school staff or administrative questions about how the school is run (Salokangas & Wermke, Citation2020; Wermke et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Salokangas, Citation2021).

The scale ‘professional collaboration in lessons among teachers’ measured forms of collaboration that reflect a deeper level of interdependence in comparison with superficial types of collaboration, such as exchanging ideas and instructional materials (see Vangrieken & Kyndt, Citation2019). These forms of collaboration may allow for collective decision-making at the school level, but they do not automatically translate into collegial teacher autonomy. In this regard, the items of this scale did not measure teachers having control over plans of action and decisions related to the professional development of school staff or teachers having the autonomy to collegially decide on administrative issues (Salokangas & Wermke, Citation2020; Wermke et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Salokangas, Citation2021). Therefore, the results regarding collegial autonomy may be interpreted with caution since professional collaboration does not automatically imply collegial teacher autonomy.

The scale ‘perceptions of value and policy influence’ comprised only three items that captured fractions of professional teacher autonomy. These items can give an indication of the status of teachers and their influence on decision-making at the policy level regarding the framings of their work, but teachers’ perceptions of value and policy influence cannot be seen as equivalent to professional teacher autonomy; rather, they are only indications of such autonomy.

This study used the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics 26 to analyse the data. Descriptive analysis of the scales was conducted. In addition, information provided by the OECD is expanded by calculating the frequencies of the answers ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ for each item of the scales ‘satisfaction with classroom autonomy’ and ‘perceptions of value and policy influence’ in the selected countries. Frequencies for each item of the scale ‘professional collaboration in lessons among teachers’ regarding the answers ‘1–3 times a month’ and ‘once a week or more’ have also been calculated. The countries are divided into different categories of educational governance related to the implementation of large-scale accountability instruments to examine the relationship between models of educational governance and teacher autonomy, as illustrated in below.

The hypothesis is that teachers in countries with strong accountability instruments (i.e. independent variable) report low perceived teacher autonomy (i.e. dependent variable). This article works with a sample size of 59790 lower secondary teachers in 19 countries from TALIS 2018 data ().

Table 1. Sample sizes in the selected countries

The selected countries represent the different accountability divisions. The selected high-stakes accountability countries are the Anglo-American countries of England (UK), New Zealand, and the USA; the Latin-American countries of Brazil and Chile; and the European countries of Estonia, the Slovak Republic, and Sweden. The selected low-stakes accountability countries include the European countries of Austria, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, and Norway; one Middle Eastern country, Turkey; and one Asian country, Japan. The selected uneven and contested accountability countries are the Southern European countries of Italy, Portugal, and Spain, as well as one African country, South Africa.

Qualitative approach

The qualitative material is from the low-stakes accountability country of Norway and the high-stakes accountability country of Brazil. The two country cases provide in-depth qualitative information about national particularities related to the implementation of policy instruments to monitor teachers’ work and students’ performance. Teachers’ perceptions on these issues are expressed through semi-structured interviews with lower secondary teachers working in public schools in Norway and Brazil in 2018.

The sample for the interviews included 20 participants, 11 Brazilian and 9 Norwegian. The participants worked in three public schools in one municipality of São Paulo Federal State (Brazil), one school in one municipality of Oppland County (Norway), and one school in one municipality of Hedmark County (Norway). The teachers had different backgrounds (e.g. gender, age, years of work experience, and subjects taught), enabling the capture of different perspectives of teacher autonomy.

According to Bryman (Citation2012), the advantage of using semi-structured interviews is that the researcher can keep the focus of the study while allowing space for the emerging views of the participants and, thereby, new ideas on the issues under investigation. Moreover, in the case of comparative studies, semi-structured interviews have ‘some structure in order to ensure cross-case comparability’ (Bryman, Citation2012, p. 472).

The interview questions approached the concept of teacher autonomy by asking teachers about their perceptions of control and decision-making regarding different aspects of teaching practices (e.g. definition of educational goals, content of lessons, learning material, teaching methods, and students’ assessment) as well as how they perceived the influence of external actors (e.g. people, institutions, and policies) in the definition of their work. The interview guide also asked teachers about their opinion of the meanings of teacher autonomy, the positive and negative sides of it, and how they perceived the degree of autonomy they had in their work. Other questions included teachers’ relationships with colleagues, including their perceptions and experiences with collegial work, and teachers’ relationships with the school leadership, including their perceptions and experiences with decision-making within school. Teachers were also asked about their satisfaction with their working conditions and the level of decision-making and engagement in relation to professional development activities. Another topic explored was their participation in teachers’ unions and their opinions about the work of teachers’ unions at the policy level.

This study addressed ethical issues by asking for the consent of all participants and explained the background and purpose of the study as well as what participation in the research implied. The informants were also notified that they could withdraw from the study at any time without the need to provide a reason. This study has also addressed privacy and protection from harm by keeping the anonymity of the participants (Cohen et al., Citation2018). In this article, the participants are presented as Norwegian and Brazilian teachers, without reference to any personal attributes or school. Finally, this study received ethical clearance from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, which is a national centre and archive for research data that aims to ensure that data about people and society can be collected, stored, and shared safely and legally.

In this article, the analysis consisted of finding examples in the interviews of the three levels of teacher autonomy (i.e. individual, collegial, and professional) and classifying them from restricted to extended. According to Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005), in this type of analysis, known as direct content analysis, the themes emerge from existing theory and research in a deductive process. The findings offer supporting and non-supporting evidence for a theory, presented by showing themes with examples and by offering descriptions. The author transcribed the interviews in their original languages (i.e. Norwegian and Portuguese) and translated the quotations used in this article into English.

Results

The presentation of the study’s quantitative and qualitative results is organized according to the different levels of teacher autonomy (i.e. individual, collegial, and professional), as described by Frostenson (Citation2015).

Individual teacher autonomy

This section presents the TALIS 2018 data and the interview data from Norway and Brazil related to the dimension of individual teacher autonomy.

TALIS 2018

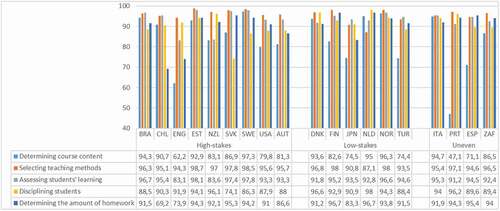

below examines each item of the scale satisfaction with classroom autonomy in the selected countries. As previously described, the selected countries are divided into three categories according to models of educational governance related to the implementation of accountability measures: countries with high-stakes, low-stakes, and uneven accountability measures. At the bottom of the figure, a frequency table is presented so that the reader can verify the corresponding scores for each country. The scores refer to the percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agreed or strongly agreed with the following statements about teachers’ satisfaction with classroom autonomy: having control over determining course content, selecting teaching methods, assessing students’ learning, disciplining students, and determining the amount of homework to be assigned.

Figure 2. Teachers’ satisfaction with classroom autonomy by country – TALIS 2018. Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agree or strongly agree with the following statements about teachers’ satisfaction with classroom autonomy

The results show no clear pattern between teachers’ satisfaction with their classroom autonomy and countries with different models of educational governance. Moreover, the cross-national variation in the items of the scale satisfaction with classroom autonomy was quite limited. For example, regarding selecting teaching methods, the average was 96.7% in high-stakes accountability countries, 94.3% in low-stakes accountability countries, and 95.9% in countries with uneven accountability. When asked about assessing students’ learning, an average of 93.2% (high-stakes), 94% (low-stakes), and 93.3% (uneven) of teachers agreed, respectively. Regarding disciplining students, the averages were 88.7% (high-stakes), 92.7% (low-stakes), and 92.3% (uneven). Regarding the amount of homework, the averages were 87.7% (high-stakes), 91.4% (low-stakes), and 93.9% (uneven).

The item determining course content displays the widest range of scores. For example, more than 95% of teachers reported that they had control in this area in Norway and Sweden, while only 47% of teachers in Portugal made the same claim. The averages for determining course content were 85.9% for high-stakes accountability countries, 85.4% for low-stakes accountability countries, and 74.8% for countries with uneven accountability.

Therefore, the results indicate that teachers’ perceptions of their autonomy at the classroom level are quite similar in the selected countries. However, even though teachers may perceive extended individual autonomy through the freedom to choose the contents, methods, assessments, and procedures for students’ behaviour, this perception does not necessarily imply that they can decide on which professional development activities to undertake or how the school is run.

Norway

Focusing on the country cases, Norwegian teachers reported being satisfied with their individual autonomy at the classroom level, as seen here:

I experience that I have a lot of autonomy. I experience that they trust that I am a professional. I experience that the competence goals are open and very much is left to the teacher. It is a starting point. The curriculum does not control my method. I choose it completely myself, more or less research-based, I think. Sometimes experience-based, on what has gone well before, but I experience that my freedom is big. I have a lot.

This teacher talked about autonomy in terms of being able to choose the methods of her teaching based on the competence goals of the curriculum. As shown in , Norwegian teachers expressed satisfaction with determining course content (96.3%) and selecting teaching methods (98%). Further, the Norwegian informants reported that they used national tests as a tool to map students’ learning needs and adapt their teaching, as in the following:

It works for me as a way to map how they are, so that I can use the results in the teaching or in a dialog with the students. And, if the results are very bad, this can put pressure on the leadership in relation to additional resources to raise those who need in the classroom.

The statement above indicates that the teaching work is shaped by national tests. At the same time, teachers can shape the conditions of their work (such as getting additional resources) by resorting to the national tests’ results. This finding points to the exercise of individual teacher autonomy regarding planning, instruction, and use of resources. Conversely, individual teacher autonomy may also be contrived by education authorities. For example, informants reported that they did not have the autonomy to decide on the use of digital tools in the classroom, as seen below:

There was no one who talked to teachers about the use of iPads; it was just “now it’s coming in, done.” Many teachers like the iPad and they use it a lot, and there are many who see the downsides of it, but no matter what, nobody asked me and talked to me first, so we do not like this so well.

Another informant explained that he was not allowed to choose which professional development activities to undertake. The decisions regarding these activities came from the municipal education authority and were passed on to teachers by the school leadership, as described in the following:

There are directives at the county level, among other things, the digitalization pressure. It pushes me a bit since the county wants to have control over this (…) and the developmental work in the school will always be influencing me as well. Now we spend a lot of time talking about coaching, which will be influencing my teaching.

In summary, the results indicate that Norwegian teachers are satisfied with their classroom autonomy, which is in line with TALIS 2018 data. However, they do perceive control over their work as a result of the implementation of accountability measures.

Brazil

Like their Norwegian counterparts, Brazilian teachers reported being satisfied with their individual autonomy at the classroom level, as this informant explained:

I have limited autonomy within what the government structures. So, I have the content that is planned and that I have to pass, and I have to account for that content to be applied at school. Now inside my classroom, I have extended autonomy to use what I want, prepare my lessons as I want, and use the resources I want. That is fine. So, this is interesting, I like it, this autonomy of methods, that I can diversify a lot of what I have to pass. I do not need to just stay on the blackboard and chalk.

Brazilian teachers discussed autonomy within limits; in other words, they expressed that they can choose the topics to teach that are within the scope of the curriculum. They also perceived having freedom to select teaching methods. indicates that Brazilian teachers expressed satisfaction with their control over determining course content (94.3%) and selecting teaching methods (96.3%). Further, some informants explained how they were expected to use the digital platform implemented by the Department of Education:

So, there are the results, and then, for example, they ask me to make a timeline with the skills and competences according to this here. So, here on top of the results, I plan the activities that I want to develop with them, focusing on the skills that I need to deepen with them, right?

The informants explained that the Department of Education expects them to use the digital platform with test results to plan and develop teaching strategies, thus indicating the influence of policy instruments on their teaching practices. Moreover, teachers talked about the need to constantly report on teaching plans and strategies to the school leadership, as one informant explained:

The school leadership is very concerned with administrative work. If the supervisor comes and looks at our diary, and the date of the lecture is missing (laughing). Having or not the date does not improve the teaching work. I have to make lesson plans with the skills and competencies to develop with the students and deliver them to the leadership. But this plan is not meant for the leadership to provide me with some help (…) She has to hand this paper over to the supervisor … .

The statement above points to strong control over teachers’ work, constraining their individual autonomy. In summary, the results indicate that Brazilian teachers are also satisfied with their classroom autonomy, which is aligned with TALIS 2018 data. However, they do perceive strong forms of external control over their work, which can be related to a high-stakes accountability system.

Collegial teacher autonomy

This section presents the quantitative and qualitative results related to the dimension of collegial teacher autonomy.

TALIS 2018

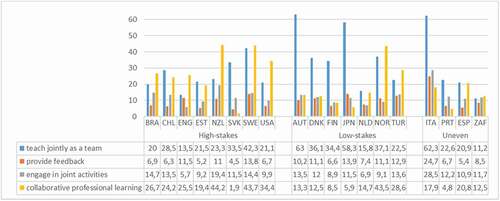

below shows teachers’ perceptions of their professional collaboration in lessons among teachers in the selected countries. The scores refer to the percentage of lower secondary education teachers who reported engaging at least once a month in the following items: teaching jointly as a team in the same class, providing feedback to other teachers about their practice, engaging in joint activities across different classes and age groups (e.g. projects), and participating in collaborative professional learning.

Figure 3. Teachers’ perceptions of their professional collaboration by country – TALIS 2018. Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who report engaging at least once a month with the following statements about teachers’ perceptions of their professional collaboration

The results show that countries with low-stakes accountability had higher scores in the item teach jointly as a team in comparison with countries with other models of educational governance. For this item, the averages were 25.5% (high-stakes), 38.2% (low-stakes), and 29.3% (uneven). Austria (63%) and Japan (58.3%) had the highest scores on this item, together with Italy (62.3%), which is classified as a country with uneven accountability measures.

Regarding providing feedback, 8.24% (high-stakes), 10.5% (low-stakes), and 11.3% (uneven) of teachers reported engaging at least once a month in this type of activity. The question of engaging in joint activities had quite low scores of 12.3% (high-stakes), 10.8% (low-stakes), and 15.8% (uneven), respectively.

Comparatively, collaborative professional learning was higher in countries with high-stakes accountability than in countries with other educational governance models. The scores in this item were 27.5% (high-stakes), 18.1% (low-stakes), and 14% (uneven). New Zealand (44.2%) and Sweden (43.7%) showed the highest scores in this item in comparison with other countries.

One important observation to make is that professional collaboration may facilitate collegial autonomy, but they are not synonymous. The fact that teachers collaborate does not necessarily mean that they are doing so by their own choice or that this collaboration concerns topics related to decision-making at the school level. Professional collaboration can very well be a form of contrived collegiality, focusing on instrumental implementation of school leadership dictates (Hargreaves, Citation1994; Hargreaves & Dawe, Citation1990), as can be the case in high-stakes accountability countries. The next sections focus on the country cases to explore the relationship between professional collaboration and collegial teacher autonomy.

Norway

Regarding the possibility for the exercise of collegial teacher autonomy, the Norwegian informants reported that the school leadership organized teachers’ work and facilitated meetings by school grade and subject, so teachers could take part in weekly meetings to discuss and plan pedagogical activities together. Collegial work can both constrain and enable teachers’ individual autonomy, as one informant explained:

In this school, students have five weeks to work with a theme. This applies to all subjects. This thematic work puts some guidelines for what you should do that I am not completely used to (laughs). And, then, I have another teacher colleague to relate to, but this is very good because we have opportunities to work together and share teaching plans and ideas. So, next year I am considering taking up more elaboration of these themes because they should be as relevant as possible.

Teachers, especially younger teachers, described their experience of collegial work as positive because it allows them to plan and share practices, as described above. According to the TALIS 2018 data, 43.5% of Norwegian teachers reported engaging often in collaborative activities in schools, which is a comparatively high score in relation to other countries (). However, this number still represents less than 50% of the Norwegian lower secondary teachers.

In summary, the data about Norway shows that collegial work does not necessarily mean collegial autonomy since teachers do not report that this increases their decision-making at the school level. However, the Norwegian informants perceive that professional collaboration can both constrain and promote their individual teacher autonomy. The positive sides of professional collaboration are perceived mainly by the younger informants.

Brazil

Regarding the possibility for the exercise of collegial autonomy, the Brazilian informants reported that school meetings are mainly used to pass on orders from the educational authority, as seen here:

These meetings are not used for pedagogical work. They are used to complaining about students, to passing on messages, and then the teacher is already tired of going there. (…) So, it is often a place of complaining about students, of grievances, and it is not used pedagogically. For example, for pedagogical purposes, you could study a text, have a dialogue with your colleagues, exchange experiences, make partnerships, and engage in interdisciplinary work. I often use the school corridor, the time I arrive, the break time, to talk to my colleagues.

Complementarily, TALIS 2018 data () shows that only 26.7% of the Brazilian teachers reported that they engage often in collaborative activities in schools. The Brazilian informants perceived collective meetings as not meant for professional collaboration. Instead, they reported that these meetings are initiated by the school leadership to implement external mandates, which can indicate a contrived collegiality (Hargreaves, Citation1994; Hargreaves & Dawe, Citation1990). As a result, not all collaborative activities benefit teachers’ work (cf. Dias, Citation2018).

Professional teacher autonomy

The following section presents the study’s results related to the dimension of professional teacher autonomy.

TALIS 2018

In the following, this article presents teachers’ perceptions of their social value and policy influence in the selected countries, which can give some indications of their perceived professional teacher autonomy.

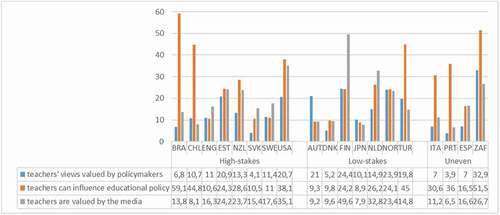

shows the percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agreed or strongly agreed with the following statements about teachers’ perceptions of their social value and policy influence: teachers’ views are valued by policymakers in this country, teachers can influence educational policy in this country, and teachers are valued by the media in this country.

Figure 4. Teachers’ perceptions of their social value and policy influence by country – TALIS 2018. Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agree or strongly agree with the following statements about teachers’ perceptions of their social value and policy influence

Regarding teachers’ views being valued by policymakers, the averages were 12.4% (high-stakes), 17% (low-stakes), and 12.7% (uneven). Low-stakes accountability countries showed a small comparative advantage in this item in comparison with countries with other educational governance models.

Low-stakes accountability countries also showed comparatively higher scores to the statement assessing whether teachers are valued by the media. The averages in this item were 19.3% (high-stakes), 21% (low-stakes), and 15.3% (uneven). Finland (49.6%) and the Netherlands (32.8%) showed the highest scores in this item, together with the USA (35.1%), which is classified as a high-stakes accountability country.

Regarding teachers’ perceptions that they can influence educational policy, 28.4% (high-stakes), 21% (low-stakes), and 33.7% (uneven) reported that they agreed or strongly agreed with this statement. The comparatively higher scores of countries with uneven accountability may relate to the role of teachers’ unions as combative and participative in educational debates in these countries (cf. Verger et al., Citation2019). The next sections address these different items of the scale in the country cases.

Norway

In addition to the opportunities for professional collaboration, Norway is known for an active teachers’ unionism that has resisted accountability measures by promoting discourses related to teacher autonomy, research-based practice, and professional development as core features of teacher professionalism (Mausethagen & Granlund, Citation2012; Nerland & Karseth, Citation2015). One informant stated:

I am a member of the teacher union. We have two representatives here, and they do a fantastic job, very good job. When there are important issues to bring up, we have meetings where we talk. They organize the meeting, and we talk and discuss things. These meetings are very informative and good. I really think they do a good job and fight for us so that we have good working relations. So, I am quite happy with them.

The Norwegian informants knew who their union representatives at school were, and some of them described situations where they asked their intermediation to solve workload and salary issues. This finding could indicate that the Norwegian teachers perceive being able to decide on the framing of their work at the policy level through their engagement with teachers’ unions. However, the interview guide did not include applicable questions to discuss teachers’ perceptions of their value by policymakers and the media. These two aspects can affect teachers’ perceptions of their professional autonomy (e.g. Erss et al., Citation2016).

However, TALIS 2018 data () showed relatively low scores for Norwegian teachers’ perceptions of being valued by policymakers (23.9%) and influencing educational policy (24.1%). One possible explanation is that the central state in Norway is responsible for curriculum design and implementation, national tests, and examinations, assuming a powerful position in the definition of policy instruments that frame the teaching profession, which may affect teachers’ views of their capacity to influence policy. Further studies are needed to explore these findings regarding professional teacher autonomy.

Brazil

Regarding the role of teachers’ unions in influencing the framings of the teaching work through policy, the Brazilian informants expressed distrust in their professional organizations. They also reported that they do not actively engage in teachers’ unions. One informant stated:

I do not participate in union meetings. I cannot do it because my workload is very intense. I am affiliated, but I do not participate. (…) So, I do not see big changes. The union is not strong (…) the union goes on a salary strike, but it is not able to bring the class together. Its claims are hardly met. Sometimes there are some gains, such as salary increases, but these are not great achievements in the improvement of education. The union’s participation in the school is very small. I do not even know who the school’s union representative is.

This statement may indicate that teachers perceive a restricted professional autonomy in which they are not able to act as a professional group to decide on the framings of their work at the policy level. As explained in the section on Norway, the qualitative data does not give elements to discuss teachers’ perceptions of their value by policymakers and the media.

Despite the lack of qualitative data, TALIS 2018 data showed that only 6.8% of the Brazilian teachers reported that policymakers value them. However, 59.1% reported that they can influence educational policy (). This finding may indicate that teachers perceive that they can act individually at the classroom level to influence policy. Alternatively, they may perceive that this is the only space for resistance left to them. These hypotheses could be explored in further studies.

Discussion

This article asked whether a high degree of educational accountability correlates with a low degree of teacher perceived autonomy and, conversely, whether a low degree of educational accountability correlates with a high degree of teacher perceived autonomy. It explored the hypothesis that teachers in countries with strong large-scale accountability instruments report low perceived autonomy, and vice versa.

The quantitative results based on the TALIS 2018 data challenged this hypothesis. Teachers are generally satisfied with their classroom autonomy (). However, as presented earlier, far fewer teachers report engaging in professional collaboration (), which could give them possibilities for exercising collegial teacher autonomy. The percentage of teachers who report influencing educational policy and being valued by policymakers and the media is even lower (). Teachers’ perceptions of their value and policy influence can affect teachers’ perceptions of their professional autonomy (cf. Erss et al., Citation2016). Having presented the quantitative results, it might be productive to gain a deeper insight into how teacher autonomy unfolds in the two country contexts.

While Brazil can be placed within a high-stakes accountability system because of the use of economic incentives related to student performance data (Lennert da Silva & Mølstad, Citation2020), Norway is characterized by a low-stakes accountability system due to a lack of such incentives (Mausethagen, Citation2013; Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019). However, despite differences in models of educational governance, Brazilian and Norwegian teachers are satisfied with their classroom autonomy. The Brazilian informants perceive having autonomy in terms of being able to choose the teaching methods based on the competences and skills of the prescribed curriculum. The Norwegian teachers also perceive having autonomy in the same domains as their Brazilian counterparts.

However, these responses do not mean that neither group of teachers perceives a lack of control being exercised over their work in the classrooms. For example, Norwegian teachers talk about the imposition of digital tools in the development of their teaching practices and the inability to choose which professional development activities to undertake in the professional developmental domain. The Brazilian informants describe the pressure to use test results and to write teaching plans and strategies to improve students’ performance data, which can be linked to economic incentives for schools and teachers that achieve performance targets. This article argues that Brazilian teachers are held more individually accountable for improving students’ outcomes than their Norwegian counterparts because of the system of economic incentives related to students’ performance, which is characteristic of high-stakes accountability countries (Verger et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Prøitz, Citation2019).

Moreover, the qualitative data describes particularities regarding the other levels of teacher autonomy. In Norway, teachers describe school leadership as playing a key role in promoting collegial work, which could allow for collegial teacher autonomy. However, the Norwegian informants do not talk about professional collaboration enabling collective decision-making at the school level. In comparison, the Brazilian informants describe the school leadership using staff meetings to implement external dictates.

Regarding the connections between teacher collaboration and collegial autonomy, contrived collegiality means an instrumental form of collaboration mandated by the school leadership with the aim of implementing agendas determined by others (Hargreaves, Citation1994; Hargreaves & Dawe, Citation1990), while extended collegial autonomy can be professional collaboration emanating from the subjective needs of the teachers who themselves set the agenda and participate in decision-making (Elo & Nygren‑Landgärds, Citation2020; Frostenson, Citation2015; Kelchtermans, Citation2006).

However, the qualitative data about professional collaboration in the country cases does not indicate that teachers perceive having collegial teacher autonomy. In the Brazilian case, contrived collegiality is hardly a sign of collegial teacher autonomy, whereas in the Norwegian case, professional collaboration facilitated by the school leadership does not imply that teachers perceive being able to collectively decide on different topics of their work within the school setting.

Regarding professional teacher autonomy, the Norwegian informants describe the role of teachers’ unions as supportive of their rights, which can indicate that they perceive being able to influence decision-making at the policy level through their participation in teachers’ unions. However, TALIS 2018 data shows relatively low scores for Norwegian teachers’ perceptions of being valued by policymakers (23.9%) and influencing educational policy (24.1%). Further studies are needed to explore these findings. Comparatively, Brazilian teachers perceive teachers’ unions as not defending their rights and beliefs, which can give some indication of teachers’ perceptions of restricted professional autonomy. TALIS 2018 data shows that only 6.8% of the Brazilian teachers report that policymakers value them. However, 59.1% report that they can influence educational policy. These contradictory findings could be explored in further studies.

In summary, even though teachers are satisfied with their autonomy at the classroom level, reporting a relative freedom to choose the contents and methods of their teaching, these findings do not necessarily imply that they perceive having extended collegial and professional teacher autonomy (Frostenson, Citation2015). Accordingly, the TALIS 2018 data shows quite low scores in items that can indicate possibilities for collegial and professional teacher autonomy.

This study shows that no clear pattern exists between teacher perceived autonomy and models of educational governance. Hence, the study’s hypothesis that teachers in countries with strong accountability instruments report low perceived autonomy and vice versa cannot be verified.

Concluding remarks

By employing quantitative and qualitative data, this article has contributed to the understanding of teacher autonomy through the eyes of the teachers across different models of educational governance. As such, the quantitative data enables an examination of teachers’ perceptions of their autonomy from a high-level perspective encompassing several countries. Complementarily, the qualitative data privileges the detailed description of teachers’ contexts and perceptions of their autonomy in two countries, highlighting country differences. In this regard, this paper hopes to have contributed to the teacher autonomy debate by using theoretical and methodological tools that allow for comparisons of the multiple levels of teacher autonomy in different country contexts.

However, it is important to mention that teacher autonomy is a multidimensional and complex phenomenon. Therefore, TALIS 2018 scales and teachers’ interviews have captured only a few aspects of it, specifically in the cases of collegial and professional teacher autonomy, where the research instruments were not able to capture the multiple aspects of each level (Frostenson, Citation2015). This is a significant validity-related question that shows the limitations of the data and points to possibilities for further research.

In addition, this paper has not addressed the domains of teachers’ work (e.g. educational, social) since it was not possible to fit such a level of detail in the scope of this paper. Recent studies on teacher autonomy have combined the levels and domains of teacher autonomy, and some of them also use TALIS data (e.g. Salokangas & Wermke, Citation2020; Wermke et al., Citation2019; Wermke & Salokangas, Citation2021).

This article also calls attention to the fact that teacher autonomy was measured for the first time in TALIS 2018. In this regard, it would be useful to follow the development of teacher autonomy in future editions of the TALIS. Moreover, by pairing TALIS 2018 data with interview data, this paper goes into granular detail that either dataset on its own could not do. As such, this study sets an example for future studies on teacher autonomy as a potential methodological approach for comparing different country contexts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainley, J., & Carstens, R. (2018). Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 conceptual framework (OECD Education Working Paper No. 187). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/799337c2-en

- Aoki, N., & Hamakawa, Y. (2003). Asserting our culture: Teacher autonomy from a feminist perspective. In D. Palfreyman & R. C. Smith (Eds.), Learner autonomy across cultures (pp. 240–253). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

- Barreto, E. S. S. (2012). Curriculum and evaluation policies and teaching policies. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 42(147), 738–753.

- Bergh, A. (2015). Local educational actors doing of education: A study of how local autonomy meets international and national quality policy rhetoric. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 1(2), 42–50.

- Bjork, C. (2009). Local implementation of Japan’s integrated studies reform: A preliminary analysis of efforts to decentralise the curriculum. Comparative Education, 45(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060802661386

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Camphuijsen, M. K., Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2020). Test-based accountability in the Norwegian context: Exploring drivers, expectations and strategies. Journal of Education Policy, 1–19.

- Cohen, E. H. (2016). Teacher autonomy within a flexible national curriculum: Development of Shoah (holocaust) education in Israeli state schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 48(2), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2015.1033464

- Cohen, L., Lawrence, M., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- Day, C., Flores, M. A., & Viana, I. (2007). Effects of national policies on teachers’ sense of professionalism: Findings from an empirical study in Portugal and in England. European Journal of Teacher Education, 30(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760701486092

- Dias, V. C. (2018). Integral education program of São Paulo: Problematizations about the teaching work. Educação E Pesquisa, 44(e180303), 1–17.

- Elo, J., & Nygren‑Landgärds, C. (2020). Teachers’ perceptions of autonomy in the tensions between a subject focus and a cross‑curricular school profile: A case study of a Finnish upper secondary school. Journal of Educational Change.

- Erss, M. (2018). “Complete freedom to choose within limits”—Teachers’ views of curricular autonomy, agency and control in Estonia, Finland and Germany. The Curriculum Journal, 29(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2018.1445514

- Erss, M., Kalmus, V., & Autio, T. H. (2016). “Walking a fine line”: Teachers’ perception of curricular autonomy in Estonia, Finland and Germany. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 48(5), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1167960

- Frostenson, M. (2015). Three forms of professional autonomy: De-professionalization of teachers in a new light. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 1(2), 20–29.

- Grek, S. (2009). Governing by numbers: The PISA “effect” in Europe. Journal of Education Policy, 24(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802412669

- Hammersley-Fletcher, L., Kılıçoğlu, D., & Kılıçoğlu, G. (2020). Does autonomy exist? Comparing the autonomy of teachers and senior leaders in England and Turkey. Oxford Review of Education, 1–18.

- Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times: Teachers’ work and culture in the postmodern age. Teachers College Press.

- Hargreaves, A., & Dawe, R. (1990). Paths of professional development: Contrived collegiality, collaborative culture, and the case of peer coaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(3), 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(90)90015-W

- Helgøy, I., & Homme, A. (2007). Towards a new professionalism in school? A comparative study of teacher autonomy in Norway and Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 6(3), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.3.232

- Högberg, B., & Lindgren, J. (2020). Outcome-based accountability regimes in OECD countries: A global policy model? Comparative Education.

- Hopmann, S. (2015). “Didaktik meets Curriculum” revisited: Historical encounters, systematic experience, empirical limits. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, (2015(1), 14–21.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Imsen, G., & Volckmar, N. (2014). The Norwegian school for all: Historical emergence and neoliberal confrontation. In V. Blossing, G. Imsen, & L. Moos (Eds.), The Nordic education model: “A school for all” encounters neo-liberal policy (pp. 33–55). Springer.

- Jansen, J. D. (2004). Autonomy and accountability in the regulation of the teaching profession: A South African case study. Research Papers in Education, 19(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267152032000176972

- Karseth, B., & Sivesind, K. (2011). Conceptualizing curriculum knowledge within and beyond the national context. In L. Yates & M. Grumet (Eds.), Curriculum in today’s world: Configuring knowledge, identities, work and politics (pp. 58–76). Routledge.

- Kelchtermans, G. (2006). Teacher collaboration and collegiality as workplace conditions: A literature review. Zeitschrift fü r Pä dagogik, 52(2), 220–237.

- Keskula, E., Loogma, K., Kolka, P., & Sau-Ek, K. (2012). Curriculum change in teachers’ experience: The social innovation perspective. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 20(3), 353–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2012.712051

- Lennert da Silva, A. L., & Mølstad, C. E. (2020). Teacher autonomy and teacher agency: A comparative study in Brazilian and Norwegian lower-secondary education. Curriculum Journal, 31(1), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.3

- Lennert da Silva, A. L., & Parish, K. (2020). National curriculum policy in Norway and Brazil. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 4(2), 64–83.

- Manzon, M. (2014). Comparing places. In M. Bray, B. Adamson, & M. Mason (Eds.), Comparative education research: Approaches and methods (2nd ed., Vol. 19, pp. 97–137). Springer.

- Mausethagen, S. (2013). Reshaping teacher professionalism: An analysis of how teachers construct and negotiate professionalism under increasing accountability. Centre for the Study of Professions, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences.

- Mausethagen, S., & Granlund, L. (2012). Contested discourses of teacher professionalism: Current tensions between education policy and teachers’ union. Journal of Education Policy, 27(6), 815–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.672656

- Mausethagen, S., & Mølstad, C. E. (2015). Shifts in curriculum control: Contesting ideas of teacher autonomy. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, (2015(2), 30–41.

- Nerland, M., & Karseth, B. (2015). The knowledge work of professional associations: Approaches to standardisation and forms of legitimization. Journal of Education and Work, 28(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2013.802833

- OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 technical report. https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/TALIS_2018_Technical_Report.pdf

- OECD. (2020). TALIS 2018 results (Vol. II): Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals. https://doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en

- Pettersson, D., & Mølstad, C. E. (2016). PISA teachers: The hope and the happening of educational development. Educação E Sociedade, 37(136), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1590/es0101-73302016165509

- Salokangas, M., & Wermke, W. (2020). Unpacking autonomy for empirical comparative investigation. Oxford Review of Education, 46(5), 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1733514

- Shalem, Y., De Clercq, F., Steinberg, C., & Koornhof, H. (2018). Teacher autonomy in times of standardised lesson plans: The case of a primary school language and mathematics intervention in South Africa. Journal of Educational Change, 19(2), 205–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-018-9318-3

- Sørensen, T. B. (2017). Work in progress: The political construction of the OECD Programme Teaching and Learning International Survey [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Bristol, EThOS. https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.723502

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2003). The politics of league tables. Journal of Social Science Education, 2(1), 1–6.

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2014). Cross-national policy borrowing: Understanding reception and translation. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 34(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2013.875649

- Tesar, M., Pupala, B., Kascak, O., & Arndt, S. (2017). Teachers’ voice, power and agency: (Un)professionalisation of the early years workforce. Early Years, 37(2), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1174671

- Therrien, J., & Loiola, F. (2001). Experiência e competência no ensino: Pistas de reflexões sobre a natureza do saber-ensinar na perspectiva da ergonomia do trabalho docente [Teaching experience and competence: Reflecting on the nature of knowledge of teaching in the ergonomics perspective of teacher’s work]. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, 12(73), 143–160.

- Vangrieken, K., & Kyndt, E. (2019). The teacher as an island? A mixed method study on the relationship between autonomy and collaboration. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 35(1), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-019-00420-0

- Verger, A., Fontdevila, C., & Parcerisa, L. (2019). Reforming governance through policy instruments: How and to what extent standards, tests and accountability in education spread worldwide. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(2), 248–270.

- Villani, M., & Oliveira, D. A. (2018). National and international assessment in Brazil: The link between PISA and IDEB. Educação & Realidade, 43(4), 1343–1362. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623684893

- Wermke, W., & Forsberg, E. (2017). The changing nature of autonomy: Transformations of the late Swedish teaching profession. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1119727

- Wermke, W., & Höstfält, G. (2014). Contextualizing teacher autonomy in time and space: A model for comparing various forms of governing the teaching profession. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.812681

- Wermke, W., & Prøitz, T. S. (2019). Discussing the curriculum-Didaktik dichotomy and comparative conceptualisations of the teaching profession. Education Inquiry, 10(4), 300–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2019.1618677

- Wermke, W., Rick, S. O., & Salokangas, M. (2019). Decision-making and control: Perceived autonomy of teachers in Germany and Sweden. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(3), 306–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1482960

- Wermke, W., & Salokangas, M. (2021). The autonomy paradox: Teachers’ perceptions of self-governance across Europe. Springer Nature.

- Wilches, J. U. (2007). Teacher autonomy: A critical review of the research and concept beyond applied linguistics. Íkala, revista de lenguaje y cultura, 12(18), 245–275.