Abstract

Motoric eating difficulties affecting the ability to eat according to established norms may result in loss of autonomy, reduced food intake and decreased social interaction. Finger food meals may affect the ability to eat independently and were therefore compared to regular meals for older adults >65 years with major motoric eating difficulties. In this pilot study the screening instrument MEOF-II, including additional questions about use of cutlery and fingers, was used to collect data regarding autonomy, food intake and social interaction through observations. Five women and one man participated in the study. Results showed that finger food meals facilitated autonomous eating since the participants were able to eat independently without relying on help from others. Less energy was spent on eating, which allowed for social interaction. However, finger food meals entail unfamiliar norms and culinary rules which may hinder eating; this is an important factor to consider in the implementation of such meals. Further studies on finger foods for older adults may consider larger and diverse cohorts, including healthy older adults, those with motoric difficulties and those with early stages of cognitive decline. Also, a wider variety of finger foods for specific cultural preferences and situations may be considered.

Introduction

Mealtimes can become a struggle when the ability to eat according to established norms and manners is impaired.Citation1–3 Paresis, weakness, pain, tremor, rigidity and slow movements are common symptoms of diseases such as stroke, Parkinsons disease and dementia, more prevalent among older adults.Citation4–8 These symptoms may lead to “motoric eating difficulties” i.e. difficulties with manipulation of food on the plate and transport to the mouth that influence the ability to manage cutlery.Citation4–9 This may in turn result in a loss of autonomy leading to withdrawal from mealtimes, assisted eating, reduced food intake, and malnutrition, all of which can impact quality of life.Citation2,Citation10–13

There is a range of eating aids available, such as modified mugs, plates and cutlery, that are specifically designed to support those with motoric eating difficulties. However, these types of aids may be difficult to use for those with severe motor symptoms such as tremor.Citation14 Another strategy that can facilitate eating is offering finger food meals.

The term “finger foods” refers to small, easily manageable food items that can be eaten without cutlery and are typically consumed by hand. These foods are designed to be easy to handle and transport to the mouth.Citation15 In the literature, finger foods are described as sandwiches, fruits and vegetables as well as breaded and fried strips of chicken and fish, quiches and cakes, and pieces of reconstituted pureed foods and cubes of solid foods.Citation15–19

Finger foods are recommended by The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN).Citation20 Finger foods can be used as an intervention to increase food intake and revert or prevent malnutrition.Citation20 In the American study by Cluskey et alCitation21, finger foods was perceived as a usually effective feeding enhancement strategy according to registered dietitians and directors of nursing service at long-term care facilities. However, finger foods were seldom or sometimes recommended and served. Additional labor costs and difficulties implementing or maintaining the strategy were reported as barriers for providing finger foods.Citation21

Other, personal, barriers to finger foods that have been reported are related to the social context. Several studies have highlighted social barriers related to the cultural context, emphasizing how cultural norms and traditions impact individuals’ food engagement.Citation12,Citation22 These norms define acceptable mealtime behavior and are driven by the desire for social acceptance and conformity. Finger food meals comprising components that are easy and acceptable for older adults with major eating difficulties to eat with the fingers may improve the ability to eat independently and, in turn, promote social interaction and result in increased food intake.

This study builds on four previous studies focusing on the development of attractive, functional and nutritionally-adapted finger food components to be used as part of a complete meal.Citation14,Citation23–25 These components comprised flatbreads, beef rolls, brown sauce and vegetables. They were developed and evaluated based on their acceptability and the sensory preferences and requirements of older adults with motoric eating difficulties.Citation14,Citation23 The finger food components, combined into a complete meal, need, however, to be pilot tested in terms of functionality and potential benefits for older adults.

The aim of this pilot study is to describe and analyze mealtime performance with regard to autonomy, food intake and social interaction when consuming finger food meals compared to regular meals among older adults >65 years of age with major motoric eating difficulties.

Material and method

Recruitment

Recruitment was carried out in cooperation with the Network for Eating and Nutrition (NEN) and the Parkinson coalition. NEN is a platform for cooperation over organizational borders in healthcare sectors in the northeast of the Swedish province of Scania.Citation26 An information letter was sent to the unit managers of four nursing homes describing the nature of the study and the need to recruit older adults >65 years with motoric eating difficulties for meal observations. The inclusion criteria were that participants were 65 years or older and had some type of advanced motoric eating difficulty. The assistant nurses and care unit managers at the nursing homes selected older adults who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and informed the older adults and their closest relatives about the study. Oral consent was obtained from the older adults and written consent was obtained from their relatives prior to the observations.

Participants and setting

In this pilot study we aimed to include older adults with a variety of diseases and functional difficulties, across diverse settings and contexts, e.g. living in their own home as well as in nursing homes. This was done to explore the feasibility of finger food meals in relation to various circumstances. In total, six older adults participated in the observations (). Five of these were females aged between 80 and 90 years, one female was diagnosed with stroke and vascular dementia and four females were diagnosed with some type of dementia. They were all living in publicly funded nursing homes in southern Sweden. The sixth participant was a male aged 89 years, diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at an advanced stage and living with his wife in their own home in southern Sweden.

Table 1. Description of the participating older adults.

Data collection

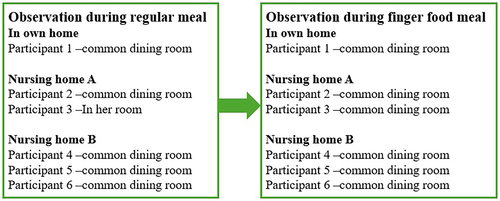

The observations were conducted at two nursing homes and, for one of the participants, in his own home. The observations were performed at lunch on two separate occasions, a regular meal was served on the first occasion and a finger food meal on the second ().

Figure 1. Presents the participant scenarios during the observations, both regular meals and finger food meals.

During the regular meal at nursing home A, participant 2 was seated at a table in the common dining room together with another resident, while participant 3, who had suffered a hip fracture, was served the meal in her own room. During the finger food meal, participants 2 and 3 were seated at the same table in the common dining room together with another resident. At nursing home B, participants 4, 5 and 6 were seated together at a table in the common dining room for both the regular and the finger food meal. Participant 1 ate his meals at the dining room table in his own home where he was served a regular meal by his wife and a finger food meal by the first author.

To facilitate the observations, an observation guide was created () based on the Minimal Eating Observation Form-Version II (MEOF-II).Citation9 MEOF-II is a validated screening instrument used to assess eating difficulties among older adults and includes the components ingestion, deglutition, and energy and appetite.Citation9,Citation27 Aspects regarding atmosphere, handling of cutlery and finger foods, and social interaction with other care recipients, professional caregivers and spouses, were added to the observation guide for the purposes of this study.

Table 2. Observation guide used to facilitate the observations.

The regular meals were prepared and served by the wife of the participant living at home and by the staff at the nursing homes. Participant 1 living at home was served porkchops with boiled potatoes, brown sauce and jam. At nursing home A, participants 2 and 3 were served a gratin with vegetables, groats and pieces of chicken. For dessert they had blueberry soup. Nursing home B offered 3 alternative dishes for the participants to choose from. Participant 4 was served spiral macaroni with a pork ragu, participant 5 was served meat and vegetable soup with a sandwich, and participant 6 only had a nutritional drink. For the dessert participants 3, 4 and 5 had plum puree with milk.

The first author prepared and served the finger foods in the common dining room at the nursing homes and in own home of participant 1. The finger food meal consisted of 2 braised beef rolls filled with plums, oven baked potato and carrot wedges and oven baked broccoli and cauliflower florets, deep-fried broccoli and cauliflower florets, a mayonnaise based brown sauce and a protein-enriched flatbread (). The first author observed the meal from a seat near the table in the common dining room. Data was collected using the observation guide and was recorded on a computer (Microsoft Office Word). Each observation lasted approximately 20–40 minutes.

Content analysis

Content analysis with a deductive approach was used to analyze the data.Citation28 The deductive procedure was divided into three phases: preparation, organization and reporting. The preparation phase involved writing a short summary of the main reflections after each observation. The organization phase involved sorting the observation notes for each participant into a template based on the main components in the observation guide: ingestion, deglutition, energy and appetite, and social interaction. The templates were first printed out and read through several times by the first author, to gain an understanding of the overall meaning of the data. The reporting phase involved describing the findings by contrasting regular meals and finger food meals based on the components in the observation guide. Rich descriptions of the mealtimes from the field notes were used to visualize the meal situation, including eating events and functional procedures. These descriptions were used to describe the observations and inform interpretations in order to incorporate an increased level of detail and authenticity.Citation29 The first author sorted the data and wrote the descriptions; all authors then discussed and revised the structure and content together.

Ethical considerations

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.Citation30 The Helsinki Declaration of Ethical Principles was considered important since the participants had both functional and cognitive impairments and were therefore considered vulnerable. Five of the older adults were unable to give written consent due to having dementia. According to the World Medical Association (2013), family members can give consent in cases where the participants themselves are unable to provide informed written consent. Family members were therefore contacted and gave their consent. In addition, data was collected in a manner that did not cause harm and protected the health, well-being, and rights of the participants.Citation30 Ethical approval was received by an advisory statement from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr: 2019-01691).

Results

Ingestion

Regular meals

Eating a regular meal was associated with a variety of difficulties and strategies for the participants. The difficulties observed were mainly related to slow movements, poor balance, stiffness and tremors. However, cognitive difficulties were also manifested through apathy and messiness. Most of the participants ate from a deep plate with a spoon and used their fingers to push the food up, or to poke the food down onto the spoon. The deep plate served as a substitute for the knife helping to lock the food in place. By lifting and tilting the plate up and down and back and forth, the food would run down and collect on the edge of the plate. The edges of the plate were then used to force the food onto the spoon, something that would have been impossible with a flat plate or if the plate had been lying flat on the table.

Participant 1 uses only one hand during the meal and therefore has difficulty getting the food up onto the spoon even if he presses the spoon against the edge. He puts the plate down so that one side is raised. The brown sauce then runs down from the top of the plate and on the way down it collects the food which then settles on the edge. Then he pokes food from the edge onto the spoon by gently using his index finger.

Participant 2’s hands shake, which makes it difficult for her to get the last bits of food off the plate. She leans over the plate, lifts up one edge, moves the plate back and forth with her hand so that the food collects on the edge and the food is then pushed onto the spoon by pressing it against the plate.

Participant 3 leans over with her mouth against the plate and tries to shovel the food into her mouth.

The participants spent a lot of time and energy consuming food while also trying to avoid spilling it. Slow movements and balance problems, above all, made it difficult for the participants to bring the food up to their mouths once they had managed to get the food onto the spoon. One scenario was that the food fell off the spoon or fork, often just when the spoon reached the mouth. Another was that they had difficulties getting the spoon into their mouth; some inserted the spoon obliquely into their mouth and others did not manage to open their mouth wide enough to get the spoon and the food in. As a result, the food fell from the mouth and the sauce ran from the corners of the participant’s mouth and chin.

Participant 4 struggles to get a piece of spiral macaroni onto her fork, three pieces of macaroni lie on the fork but two fall off onto the table and the floor on the way up to her mouth, only one piece of macaroni ends up in her mouth.

Participant 3 eats blueberry soup with a spoon, the spoon goes obliquely into her mouth each time and half the soup on the spoon runs down over her chin and bib, she tries to lift the plate up to her mouth to avoid spilling.

Not being able to get the food up onto the spoon and into the mouth led to frustration. The participants used their fingers to catch food that was spilled, picking it up and pushing it back into their mouth, or helping the spoon into their mouth by opening their mouth with their fingers and pushing the spoon in. Some of the participants even lifted the plate up to their mouth to take a bite of something, for example a piece of meat. Another disadvantage of not being able to manipulate the food properly on the plate was that it was difficult to get some of every component onto the spoon. Instead, participants had to settle for one spoonful of each component at a time.

Participant 4 tries to balance a large piece of meat on the fork, she slowly and shakily moves the fork to her mouth but the piece of meat is too large and she has trouble getting it into her mouth.

Participant 3 has difficulty finding her mouth and getting the spoon in straight. She pushes the spoon forcefully into her mouth using her hand. She fills the spoon to the brim, with high piles of food, and then takes two smaller bites from it.

Participant 2 has difficulties in getting larger pieces onto the spoon. She leans over the plate and lifts one edge of the plate to help scoop the food up onto the spoon. A little frustrated, she lifts the plate up to her mouth and takes a piece of chicken with her mouth instead.

Finger food meals

None of the participants reacted noticeably to being served a meal in which they were encouraged to eat with their fingers. Some began to eat immediately, without any hesitation about what to do, and expressed themselves in a way that indicated that it was not at all strange for them to eat with their fingers.

Participant 1 does not react noticeably to his wife telling him to eat with his fingers, but he starts by feeling the whole plate with his fingers and feeling the components.

Participant 2 expresses no discomfort or reaction to eating with her fingers. When the plate is placed in front of her, she asks for a spoon, whereupon the staff tell her that it is a meal you can eat with your fingers. “I’m glad I washed my fingers,” she said.

Participant 4 receives the food served on the plate at the table. She does not hesitate before starting the task of eating with her fingers and neither does she show any reaction.

Other participants sat and looked at the plate and did not really seem to understand what to do or what was expected of them.

Participant 5 is not sure what to do with the food. She sits and looks at the plate and takes the food, twisting and turning it. Then wipes her fingers on the bib.

Participant 3 seems to have difficulty understanding how the meal should be eaten, she sits and looks at the meal, touching the pieces gently with her fingers. She doesn’t express any discomfort from touching the food with her fingers but says several times that she’s not hungry.

Different ways of approaching the finger food meal were observed. Some of the participants ate one component at a time while some ate a little of each component in turn. Some dipped the components in the sauce while others did not touch the sauce at all.

Participant 2 lifts the sauce bowl up with her right hand and puts it in her left hand, then she uses her right hand to hold the components and dip them in the sauce. She eats a little of all the components, varying the intake. Picks up, dips, bites and puts back.

Participant 1 starts by breaking off the bread and dipping it into the sauce and then eats one component at a time, he has no problem bringing the food up to and into his mouth.

Participant 3 lifts up the bread and eats it as it is, then she continues with the deep-fried vegetables, potatoes, carrot and vegetables without dipping them in the sauce. She starts eating a beef roll but doesn’t seem to understand what the bowl of sauce is for.

Participant 4 eats with both hands, meat in one hand and carrot in the other. She holds the bread with both hands as if it’s a hamburger, dipping it in the sauce, biting off a bit and putting it back on the plate.

Participant 5 picks up a beef roll and dips it around on the plate, then she holds the ends in each hand like a rib and bites the beef roll in the middle. Next, she eats some oven-baked vegetables and deep-fried vegetables. She puts the glass on the plate and pushes the plate away. She pulls the plate out again and doesn’t seem to understand that it’s food.

Participant 6 feels the meat with her fingers and squeezes it a little, eats the bread and the deep-fried vegetables, but is very reluctant to eat.

Although the participants in the nursing homes were diagnosed with dementia and were partly oblivious of the requirements for table manners, there were times when it was possible to glimpse attempts to maintain normative eating during the meal.

Participant 4 first eats with her fingers without any problems, then she uses the bib to lift a piece of potato into her mouth to avoid touching it with her fingers. She also tries holding two pieces of carrot and uses them to lift a piece of potato into her mouth only to then start eating with her fingers again.

Participant 2 states that her fingers are sticky after the meal and is given a napkin to wipe them on.

The finger food meal was appreciated; several of the participants thought it tasted good and the finger food components worked well in that they could be held and brought up to the mouth. The bread, oven-baked vegetables and deep-fried vegetables worked for all the participants; however, pieces of oven-baked broccoli and cauliflower that were too large were difficult to handle and bring to the mouth without spilling. The bread was not used to hold the meat as intended but no one expressed discomfort at taking hold of the meat with their fingers. Participants ate several pieces of bread, some dipped it in the sauce, others did not.

Participant 1 starts by breaking off the bread and dipping it into the sauce. His wife encourages him to take the meat with the help of the bread, but he grabs the meat with his fingers and dips it in the sauce without thinking about it.

Participant 2 states that the food is good and that the meat tastes good.

Participant 2 picks up a piece of cauliflower that falls apart when it is brought to the mouth.

Participant 3 lifts up the bread and eats it as it is.

The sauce was served in a sauce bowl so that it would not become sticky on the plate. The sauce was enjoyed by the participants who had different approaches to eating it.

Participant 1 feels for the sauce bowl on the plate and tries to dip the components into it, a little here and there on the plate. His wife takes his hand and brings it to the sauce bowl. He dips the meat into the sauce that sticks to the components without running off. He asks for more sauce.

Participant 2 holds the sauce bowl in her left hand and brings it up to her mouth and she sucks the sauce up with her lips and then places the sauce bowl at the side of the plate next to the drink.

Participant 4 lifts up the sauce bowl with her left hand and asks if she is allowed to dip her finger in the sauce. The staff say yes encouragingly and then she dips her finger in the bowl and lifts a large dollop of sauce up to her mouth.

At one of the nursing homes, the staff poured the sauce onto the plate to make it easier for the participants. This meant that there was sauce on the vegetables and then on their fingers. One of the participants did not seem to understand that it was food and started to mess with the components on the plate.

Participant 5 fills the sauce bowl with potatoes, carrot, meat and bread and presses everything down with her hands. She picks up and eats some oven-baked vegetables and deep-fried vegetables then she presses the food with a piece of bread and pushes away the plate. She gets sauce on her hands which she wipes away with a napkin which she then puts on the plate.

The participant at home was able to grasp, hold and eat the components independently. However, his impaired vision made it difficult for him to identify the components on the plate.

Participant 1 tries to grab an engraved flower bouquet on the chinaware, thinking it is deep-fried broccoli or cauliflower.

Deglutition, energy and appetite

Regular meals

Despite the difficulties of manipulating the food and bringing it to their mouth, most participants in the nursing homes were able to consume a whole meal, including both main course and dessert. Only one of the participants was unable to consume a whole meal and fell asleep during the meal. None of the participants asked for or accepted an extra portion of food. Chewing and swallowing difficulties were also considered; there were some participants who mainly had difficulty chewing, with meat being especially difficult. The participant in his own home ate well and took an extra portion with the encouragement of his wife.

Participant 4 has no pronounced problems chewing and swallowing, but the ragu meat in the regular meal is dry and hard. She has difficulty chewing a large piece of meat and takes it out of her mouth with the help of her hand and puts it back on the plate again.

Participant 5 puts her finger in her mouth to show the nurse feeding her that the food has collected in her cheek and she repeatedly expresses her concern about it getting stuck in her throat.

Participant 1 has a little difficulty chewing and swallowing according to his wife, so the food is adapted to his needs. He is given soft food and avoids foods that can get stuck in his throat. He chews for a long time, but no food accumulates in his mouth or in his throat.

Finger food meals

There were no major differences between a regular meal and a finger food meal in terms of the time required to consume an entire meal. However, less energy was required for eating finger foods which was of benefit to those who struggled with using cutlery during the regular meal. One participant who received help with feeding because she was unable to consume a meal on her own was also unable to eat a finger food meal. The participant who received partial feeding help was able to eat a whole finger food meal on her own and also took more food on two occasions. One participant who had previously eaten a whole regular meal did not complete the finger food meal, saying several times that she was not hungry. Another participant who had previously consumed a liquid diet when she did not want to eat proper food ate oven-baked and deep-fried vegetables and the bread.

The professional caregivers refill the plate with bread and deep-fried vegetables for participant 6 because these seem easier for her to eat.

Only one of the participants expressed difficulty chewing the beef roll but was encouraged by his wife to use the sauce.

Participant 1 says that the meat is a little dry and is then reminded by his wife to dip the meat in the sauce so that it becomes easier to chew. He dips the beef roll in the sauce before putting it into his mouth.

When the participants were asked if they wanted more food they declined but then took extra helpings when the finger foods were placed on the table.

Social interaction

Regular meals

Whether eating at a nursing home or in one’s own home, there was not much time for social interaction. Instead, the conversation conducted at the table revolved mostly around the meal and the best way for it to be eaten. At one nursing home, professional caregivers regularly encouraged and reminded participants to eat, and helped them put food onto the spoon. Some of the participants needed full or partial help with feeding to be able to eat anything at all. One of the participants was difficult to communicate with, and the staff struggled to get her to eat the food.

Participant 6 is sitting and dozing throughout the whole meal, the staff remind her to eat. She takes a sip of her soup served in a mug and dozes off again. After more encouragement, she takes another sip before dozing off again.

Even the participant consuming meals in his own home was coached by his wife about the best way to eat the food. She portioned out and divided the food up on the plate, and then served the food at the table, encouraging her husband to focus on eating the meal instead of on the food being spilled.

The wife of participant 1 encourages him not to care about what he spills: “We’ll sort it out later, it can be washed.” She says the most important thing is that he eats the food, and she encourages him to use his fingers to help.

The social interaction between the residents at the nursing homes varied between the different tables. At one table some of the residents sat together and talked, they stayed there for a long time after the meal and had a good time together. During the observations the participants were scattered throughout the dining room; they sat quietly and focused entirely on eating their meals. After the meal they stayed and talked, even if they talked somewhat incoherently. The other table guests did not seem bothered but, on a couple of occasions, commented when food was spilled.

Participant 2 talks to the others at the table even though none of them talk about the same things. They also comment when there is food on the table and floor. She looks around and cuddles herself a little, dries and wipes around her mouth with the bib, and cleans up after herself, pushing a piece of chicken that is on the floor with her foot before asking for help from the staff.

Finger food meals

At the nursing home, even the finger food meal revolved around making the meal easier for the residents to eat. The professional caregivers encouraged the participants to eat with their fingers. They helped those who they perceived to be unsure and confused about what to do by showing them, and by putting the food in their fingers and helping them dip it in the sauce.

Participant 5 is reminded by the staff that it is food and that she should taste it. They try to help her by putting a piece of potato, a piece of meat and some bread in her hand and encouraging her to dip them in the sauce and put them into her mouth.

Participant 3 is encouraged to take more food and the staff show her how the sauce bowl should be used. The staff encourage her to eat with her fingers and show her how she can hold, dip and bring the food up to her mouth.

For the participant living at home, the social interaction demanded less coaching as he was able to eat the finger foods independently, which facilitated the possibility of conversation about other subjects. The social interaction between the participants in the dining room of the nursing home was no different from that at regular meals. No one reacted to the participants being served different food because they were used to many residents being prescribed other food for various reasons. However, during the meals at one of the nursing homes, one of the residents at another table reacted to the participants sitting and eating with their fingers. She wondered several times why they were eating with their fingers, which also directed the attention of others to the table where the participants were eating.

One of the residents at another table asks them why they are doing that? She and the other residents are also watching. Then she turns her chair around and sits and follows the meal, displaying skepticism in her body language.

After the meal, the woman then looked for the staff in the kitchen to ask them why the residents had eaten with their fingers. The staff explained that they had been testing finger foods because they have difficulty eating independently with cutlery. The woman immediately softened and said that she wished the staff had informed her so that she knew what it was about.

Discussion

Result discussion

From a functional perspective the finger food meals facilitated autonomous eating. Most participants were able to eat independently and did not have to rely on professional caregivers or relatives to cut their food. The finger food components made it easier for most of the participants to grab and bring the food from the plate to their mouth without spilling it. Medin et alCitation2 reported that assisted eating resulted in feelings of forced feeding and loss of control when they are unable to determine the pace and rhythm of the feeding themselves. By serving finger foods, the participants in the current study regained control of their eating situation, regulating the pace and amount of food themselves, which demanded less energy.

The meals in the nursing homes give an opportunity for social interaction with other residents.Citation3 However, those with motoric eating difficulties focus all their energy on eating the meal, which does not leave much opportunity for engaging in social interaction. Serving a finger food meal allowed social interaction between one participant and his wife in their own home. When less focus was placed on the meal itself, they were able to talk about other things. In the study by Forsberg et alCitation14 one of the spouses described how she was unable to share a meal together with her partner who had Lewy Body dementia. She always had to assist him first, which resulted in her meal going cold. WallinCitation12 described in her thesis how spouses would maintain ordinariness by preparing and modifying meals so that they could share mealtimes. A finger food meal may therefore facilitate them being able to share a meal together again.

Finger food meals inherently involve unfamiliar eating norms and culinary rules which can either facilitate or hinder food intake. One participant barely touched her finger food meal and stared at the plate for an extended period of time before picking up the flatbread. This may be because she was confused and did not know where to start or which components should go together. Starting with the bread may have been easier because it was familiar to her. The bowl with sauce was also handled in various ways, including leaving it on the plate, holding it in the hand, or placing it next to the drink or the plate. Serving sauce and condiments separately in a bowl is common nowadays when eating out in restaurants, but may not be familiar to older adults. However, the study by Kimura et alCitation31 showed that basic sensory factors such as taste and food texture have a positive influence on the food intake of older adults with dementia when sauce is introduced. They suggest that this effect is more significant than the influence of complex mental factors like memory and (un)familiarity with eating habits, like sauce dipping.

Food has been described by anthropologists as a system of communication.Citation32 For example DouglasCitation33 compared eating to talking, suggesting that there is an encoded message in the foods that we eat and this message is expressed in the pattern of social relations. The message is about inclusion and exclusion, as well as boundaries and transactions across these boundaries.Citation33 Unlike linguistics, the concept of culinary grammar entails information about ingredients, preparation methods, and how foods are served within a given culinary culture.Citation34

To obtain familiarity and acceptability, the whole culinary “language,” with its grammar and syntax, has to make sense.Citation35 It may, therefore, take a while before eating finger food meals is perceived as normative. However, Nyberg et alCitation22 found that eating and drinking was part of a re-learning process among those with motoric eating difficulties, including finding new ways of performing previously well-known activities. Serving familiar dishes may therefore be helpful when implementing finger food meals. It also takes time and encouragement from professional caregivers, spouses and relatives to adjust and adapt to this new way of eating. This can be stimulated by creating a permissive and inclusive atmosphere and by openly communicating the purpose of finger foods. Residents with different levels of eating dependence can be seated at the same table so that either residents or professional caregivers can mirror the movements of finger food eating. Moreover, serving finger food meals to all residents may normalize eating with the fingers.

In the present study, cognitive decline impeded eating. Although previous studies have reported that finger foods are optimal for those with dementia, this study showed that finger foods may not be so for those with severe cognitive decline.Citation15–17 One participant was unable to recognize the finger food components as food and therefore could not eat a meal independently. According to Kai et alCitation36, the inability to recognize food and eating utensils, difficulties in maintaining attention, and changes in eating routine are common among persons with dementia and may be due to apraxia or agnosia. This suggests that an individual assessment may need to be performed before introducing finger foods to persons with severe dementia.

Overall, the participants in the current study did not react negatively, nor did they object to eating the finger food meal. Several studies have described how older adults with motoric eating difficulties avoid eating with others because of changes in their appearance and behavior.Citation7,Citation14,Citation22 In particular, formal meals, such as those in restaurants, were avoided since plated tables, tablecloths, candle lights and flowers were associated with proper table manners, which include eating with a knife and fork.Citation14 In this study the participants ate the finger food components with their fingers without hesitation and they did not seem to be aware of, or feel uncomfortable about, the presence of other residents in the dining room. This may indicate that the participants were oblivious to social norms and expectations regarding eating behavior due to their cognitive difficulties. However, finger food meals may not be so well accepted by older adults with mild cognitive impairment.

Methodological considerations

This pilot study involved vulnerable older adults with both functional and cognitive impairments who were unable to give their written consent for participation. In accordance with the Declaration of HelsinkiCitation30, consent was obtained from relatives before the observations took place. Data was collected in a manner that did not cause harm and protected the health, well-being, and rights of the participants.Citation30

Since this was a pilot study, the sample was small and not representative since it included mostly older adults with eating difficulties related to dementia. The initial intention was to include multiple older adults with eating difficulties related to various diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Parkinsonism, stroke and Alzheimer’s disease. However, this was not feasible since the study took place during the Covid-19 pandemic which made it difficult to recruit older adults living in their own homes. Only two nursing homes were able to admit us to their facilities where the residents mainly suffered from dementia. A larger sample of participants with a variety of diseases would have allowed us to evaluate the use of finger foods in relation to a greater diversity of conditions and functional difficulties. However, since this is a pilot study designed to test the procedure, it still provided valuable insights into aspects such as inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as opportunities for improving the observation procedure.

A larger and more diverse sample would also have allowed the evaluation of how cognitive differences can affect the acceptability of finger foods and eating with the fingers in a social environment. Understanding eating norms, such as socially and culturally accepted behaviors, practices, and beliefs surrounding mealtimes, is important when developing and implementing finger food meals. The participants in the current pilot study ate with their fingers without objections, showing no signs of indignity or discomfort. However, this experience may vary among participants with different diseases and less severe cognitive difficulties. This pilot study therefore needs to be replicated with a larger sample, including participants experiencing motoric eating difficulties due to various diseases with minor, moderate, and major eating difficulties.

The observation guide was easy to understand and follow, and it made it easy to focus on what was relevant for the study. However, the overall procedure was difficult to standardize due to the various settings, different routines at the nursing homes, and the number of participants being observed at the same time. Although they were seated at the same table, it was difficult to focus attention on two or three participants during the meal. Important events may therefore have been missed. Observing just one participant at a time would be preferable.

MEOF-II has demonstrated a logical structure which supports good validity.Citation9,Citation27 Significant associations between the dimensions of eating difficulties and outcome, as well as interventions, further support good validity of MEOF-II.Citation9,Citation27 In addition, MEOF-II has shown good inter-observer reliability (exact agreement 0.89, Kappa 0–70).Citation9 For this study, additional aspects were added concerning handling cutlery and finger foods, and social interaction; these have not been tested for validity or reliability. It can be considered a strength that the same person (the first author) conducted all the observations. However, the observation guide needs further testing and evaluation.

There were no differences in the way the finger food components were prepared in the different observations. The first author prepared the components the day before the observations according to the recipes and preparation routine described in the study Forsberg et alCitation24 and vegetables reported in Forsberg et alCitation25. The components were heated before serving. All participants were served the same amount of food and they were all able to receive a second and third serving if they wanted. However, the size and color of the chinaware varied between locations.

For future research, it is also important to replicate the observations on multiple occasions, including various types of meals, both regular meals and finger food meals. Replications help determine the generalizability of research findings beyond specific conditions or populations. By replicating the study across diverse settings (at home and nursing home) or with diverse samples (different diseases), it is possible to assess the extent to which the results hold true in different contexts. Future studies should also include a formal screening and assessment of dysphagia since dysphagia may need to be an exclusion criterion. For persons with dysphagia, mechanically altered diets addressing safety and tolerance is of priority. However, it should be noted that pureed and reconstituted foods can be served as finger foods for those in need of texture modified foods.Citation15

Conclusion

This pilot study showed that finger food meals may have the potential to improve mealtimes for older adults with severe motoric eating difficulties. Finger food meals can increase autonomy and food intake, and promote social interaction. However, finger food meals may not be optimal for some older adults with severe dementia as they may not recognize the food items. Likewise, finger food meals may not be optimal for persons with dysphagia, since they might need a mechanically altered diet to assure swallowing safety. When recruiting participants, it can be beneficial to conduct an individual assessment beforehand to ensure that they can eat with their fingers. Additionally, the texture of the food also needs to be modified according to the participants’ needs. Finger food meals also involve unfamiliar norms and culinary rules, which should be considered in the implementation of such foods. Thus, it may take time and encouragement from professional caregivers, spouses and relatives to adjust and adapt to this new way of eating.

Take away points

This study describes and analyzes regular meals and finger food meals with regard to autonomy, food intake and social interaction.

Finger foods have the potential to improve mealtimes for older adults with severe motoric eating difficulties.

Finger food meals entail unfamiliar norms and culinary rules which can either facilitate or hinder eating.

Finger food meals may not be optimal for some older adults with severe dementia who may not recognize the food items.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Scanian Parkinson coalition and the Network for Eating and Nutrition for all their help with recruitment. We would also like to thank all the participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gustafsson K, Andersson I, Andersson J, Fjellström C, Sidenvall B. Older women’s perceptions of independence versus dependence in food‐related work. Public Health Nurs. 2003;20(3):237–247. doi:10.1046/j.0737-1209.2003.20311.x.

- Medin J, Larson J, Von Arbin M, Wredling R, Tham K. Striving for control in eating situations after stroke. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(4):772–780. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00775.x.

- Blomberg K, Wallin A-M, Odencrants S. An appealing meal: Creating conditions for older persons’ mealtimes – a focus group study with healthcare professionals. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(17–18):2646–2653. doi:10.1111/jocn.15643.

- Jacobsson C, Axelsson K, Osterlind PO, Norberg A. How people with stroke and healthy older people experience the eating process. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9(2):255–264. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00355.x.

- Westergren A, Unosson M, Ohlsson O, Lorefält B, Hallberg IR. Eating difficulties, assisted eating and nutritional status in elderly (> or = 65 years) patients in hospital rehabilitation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39(3):341–351. doi:10.1016/s0020-7489(01)00025-6.

- Medin J, Windahl J, von Arbin M, Tham K, Wredling R. Eating difficulties among stroke patients in the acute state: a descriptive, cross‐sectional, comparative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(17–18):2563–2572. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03812.x.

- Westergren A, Hagell P, Wendin K, Hammarlund K. Conceptual relationships between the ICF and experiences of mealtimes and related tasks among persons with Parkinson’s disease. Nor J Nurs Res. 2016;36(4):201–208. doi:10.1177/2057158516642386.

- Jung D, Lee K, De Gagne JC, et al. Eating difficulties among older adults with dementia in long-term care facilities: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10109. doi:10.3390/ijerph181910109.

- Westergren A, Lindholm C, Mattsson A, Ulander K. Minimal eating observation form: reliability and validity. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(1):6–12. doi:10.1007/s12603-009-0002-4.

- Carlsson E, Ehrenberg A, Ehnfors M. Stroke and eating difficulties: long-term experiences. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(7):825–834. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01023.x.

- Wikby K, Fägerskiöld A. The willingness to eat. An investigation of appetite among elderly people. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18(2):120–127. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00259.x.

- Wallin V. Mealtimes in Palliative Care contexts -Perspectives of Patients, Partners, and Registered Nurses [Dissertation]. Marie Cederschiöld University; 2021.

- Nyberg M, Olsson V, Pajalic Z, et al. Eating difficulties, nutrition, meal preferences and experiences among elderly: a literature overview from a Scandinavian context. JFR. 2015;4(1):22–37. doi:10.5539/jfr.v4n1p22.

- Forsberg S, Westergren A, Wendin K, Rothenberg E, Bredie WLP, Nyberg M. Perceptions and attitudes about eating with the fingers - an explorative study among older adults with motoric eating difficulties, relatives and professional caregivers. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;41(1):65–91. doi:10.1080/21551197.2022.2025970.

- Pouyet V, Giboreau A, Benattar L, Juveler G. Attractiveness and consumption of finger foods in elderly Alzheimer’s disease patients. Food Qual Prefer. 2014;34:62–69. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2013.12.011.

- Soltesz KS, Dayton JH. The effects of menu modification to increase dietary intake and maintain the weight of Alzheimer residents. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Dement. 1995;10(6):20–23. doi:10.1177/153331759501000604.

- Jean LA. “Finger food menu” restores independence in dining. Health Care Food Nutr Focus. 1997;14(1):4–6.

- Visscher A, Battjes-Fries MCE, van de Rest O, et al. Fingerfoods: a feasibility study to enhance fruit and vegetable consumption in Dutch patients with dementia in a nursing home. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):423. doi:10.1186/s12877-020-01792-5.

- Carrette J, Chrusciel J, Ecarnot F, Sanchez S. Prospective, observational study of the impact of finger food on the quality of nutrition evaluated by the simple evaluation of food intake (SEFI) in nursing home residents. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2023;35(8):1661–1669. doi:10.1007/s40520-023-02444-5.

- Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):10–47. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.024.

- Cluskey M, Kim Y. Use and perceived effectiveness of strategies for enhancing food and nutrient intakes among elderly persons in long-term care. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(1):111–114. doi:10.1016/s0002-8223(01)00025-6.

- Nyberg M, Olsson V, Örtman G, et al. The meal as a performance: food and meal practices beyond health and nutrition. Ageing Soc. 2018;38(1):83–107. doi:10.1017/S0144686X16000945.

- Forsberg S, Bredie WLP, Wendin K. Development of finger foods - sensory preferences and requirements among Swedish older adults with motoric eating difficulties. Food Nutri Res. 2022;66:8269. doi:10.29219/fnr.v66.8269.

- Forsberg S, Olsson V, Verstraelen E, Krona A, Bredie WLP, Wendin K. Proposal of development of finger foods for older adults with motoric eating difficulties - a study based on creative design. Int J Gastron Food Sci. 2022;28:100516. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2022.100516.

- Forsberg S, Olsson V, Bredie WLP, Wendin K. Vegetable finger foods - preferences among older adults with motoric eating difficulties. Int J Gastron Food Sci. 2022;28:100528. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2022.100528.

- Pajalic Z, Westergren A. A Network for eating and nutrition as a platform for cooperation over the organizational borders between healthcare sectors in Sweden. J Health Sci. 2014;4(3):169–175. doi:10.17532/jhsci.2014.225.

- Westergren A, Melgaard D. The minimal eating observation form – version II (MEOF-II) Danish version – psychometric and metrological aspects. J Nurs Meas. 2020;28(1):168–184. doi:10.1891/jnm-d-18-00084.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Kostova I. Thick description. In: Turner BS, Kyung-Sup C, Epstein CF, Kivisto P, Ryan M, Outhwaite W, eds. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Theory. New Jersey, NY: Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. doi:10.1002/9781118430873.est0774.

- World Medical Association. Medical association declaration of Helsinki, ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053.

- Kimura A, Yamaguchi K, Tohara H, et al. Addition of sauce enhances finger-snack intake among Japanese elderly people with dementia. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14(14):2031–2040. doi:10.2147/CIA.S225815.

- Ekström M. Kost, klass och kön [Dissertation]. Umeå University; 1990. [In Swedish].

- Douglas M. Deciphering a meal. In: Counihan C, van Esterik P, Julier A, eds. Food and Culture -a Reader. New York, NY: Routledge; 2017:249–275.

- Buccini AF. Defining ′cuisiné: communication, culinary grammar and the typology of cuisine. In: McWilliams M, ed. Food and Communication -Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery. London: Prospekt Books; 2015.

- Fischler C. Commensality, society and culture. Soc Sci Inform. 2011;50(3–4):528–548. doi:10.1177/0539018411413963.

- Kai K, Hashimoto M, Amano K, Tanaka H, Fukuhara R, Ikeda M. Relationship between eating disturbance and dementia severity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0133666. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133666.