ABSTRACT

This paper examines how higher education researchers approach writing the rationale and justification for their work published in journal articles. A common way for establishing this justification is through claiming a gap, but the problem is that it is often hard to find a research gap, and if it is included, there is too often no explanation for why the gap is worthwhile in terms of its contribution to knowledge. What we do not know is how this task is approached across the field, what different approaches are taken, and what the implications might be for the quality of research and the advancement of knowledge. Therefore, we examined the gap statements from 124 articles from five top-ranked higher education journals. What we found is that the majority of articles do have a gap statement, but these are mostly implicit rather than explicit, and located somewhere in the introductory text. However, 20% of articles had no gap statement and 27% of all articles had no justification for the importance of the research. Based on the data and drawing on theory, we present a tool to assist with writing gap statements and comment on current practice in relation to knowledge contribution.

Introduction

The authors of this paper teach research methods for the study of higher education. We supervise postgraduate students and work with academic colleagues who research into their teaching practices, or who take part in our formal postgraduate higher-education courses. Our students and colleagues new to higher education are aware that they need to address an original question of interest, but for the novice, it is not always intuitive that they should justify why their question should be answered and not another. We suggest that the ‘why’ relies on identifying a research gap, but an explanation of why it is meaningful can turn it into a ‘worthwhile gap’ or may lead to changes in the question or even encourage the researcher to seek a new direction if necessary. By stating the contribution to knowledge it will make, such a gap statement conveys to others in the field the research rationale and the reason they should take an interest in the work. These ideas are well established across many different disciplines (Chatterjee and Davison Citation2021; Daniel and Harland Citation2018; Nyanchoka et al. Citation2020; Rojon and Saunders Citation2012). However, when we read higher education articles, or referee for journals, we often find that the research gap is not clear, or if it is, then the contribution to knowledge is not claimed. We find ourselves having to read the whole paper to try and discover these points and, on many occasions, have ended up disappointed. In refereeing, we would ask for this justification if it was missing in an early draft.

We are also aware that although claiming a gap is an effective and widely used rhetorical device for both situating the research in the literature and conveying its importance, it may not be the only way to do so. In this paper, we conduct an empirical study to find out how published authors establish a rationale for their work and what the ramifications might be for the quality of higher education research. What we presently do not know is the proportion of refereed published articles that provide a clearly justified research gap. If it is possible to publish without a gap statement, then we might question the link between research methods training and the realities of publishing, and in addition, the implications for the field and the quality of its scholarship. We will argue that more attention should be devoted to how gaps are claimed with the expectation that authors articulate a ‘worthwhile gap’ as a rationale for a study. We propose that this will require self-reflection on the part of authors, which includes us, greater scrutiny in the peer review process, and explicit training for those new to this field of inquiry.

Roles and purposes of claiming gaps in research

The main purpose of conducting academic research in any field is to advance and improve collective knowledge. To be worthy of publication, a research paper should make a sufficient contribution to this. Research is commonly evaluated by other experts in the field and while this process is not without flaws (e.g. subjective and prone to bias), peer review has for a long time been foundational in higher education (Tight Citation2022) and is deemed crucial for improving the quality of knowledge (Forsberg et al. Citation2022). It is therefore imperative for peer reviewers to evaluate whether a study’s topic is of importance or significance, and whether it adds to existing knowledge in a way that warrants its publication (Barczak and Griffin Citation2021). In this context, authors should clearly communicate the rationale for their research, and a common rhetorical device has been a claim for a ‘gap’ in the literature or in knowledge.

Research, however, may not begin with the gap; it may begin with something else: an interest, a hunch, an intuition. There are many questions related to the starting point for a project: What is the motivation for doing this research? Where does the idea come from? An initial idea could be anywhere between vague and broad to clear and specific, but it is usually the start and ‘great ideas are the scarcest resource in academia’ (Kock, Assaf, and Tsionas Citation2020, 1140). Early on in the research process it is sometimes difficult to know whether a particular idea is a good one, especially if levels of knowledge or expertise are limited. However, a critical review of the published literature is the usual way to validate, develop, refine and, on some occasions, abandon ideas.

In our experience, we rarely, if ever, naively search for, collate and read publications in order to find a gap. Rather, we do those things following an idea for new research. We then thoroughly examine the literature with respect to what is already well known, little known, and unknown, but we also draw on our experiences and observations for problem identification. Establishing that an idea is a good one inherently means there is a research gap, but whether or not it is worthwhile ‘filling’ this gap is a different yet crucial matter. Kock and colleagues (Citation2020) note that while it is challenging to come up with original research ideas, researchers seldom disclose how their ideas have been generated, and there is little guidance for those new to research on how to create ideas. There is, however, clear guidance from the research methods literature about gap statements (these are sometimes called problem statements).

Once a project is completed and ready for submission to a journal for review, the research idea, gap, questions and hypotheses should have been figured out, but the process in which these were generated and developed usually remains hidden. Once a paper is in its final form, it is also possible that there were changes to a gap statement, research question or claims for contribution to knowledge following comments from reviewers. The initial idea that led to the research, however, will not change. Chatterjee and Davison (Citation2021, 227) refer to this as the authors’ ‘positioning and motivation’, namely the reason for undertaking the research.

Instead of providing the motivation for a study or explaining the idea that led to it, it is common across most disciplines to flag gaps in the literature as the research rationale. However, Chatterjee and Davison (Citation2021, 227) note that ‘While librarians might care about gaps on the shelf and dentists may be troubled by gaps in your teeth, we suggest that researchers should tread warily where gaps are concerned’, and warn against the limitations of gap-spotting research (Alvesson and Sandberg Citation2011). This warning is against the fallacious suggestion that there is an inherent value in doing something that has not yet been done.

Working within the field of organisational studies, Alvesson and Sandberg provide a critical view of the phenomenon they derogatively call ‘gap-spotting’ (Alvesson and Sandberg Citation2013; Sandberg and Alvesson Citation2011). They suggest that this practice leads to incremental and often esoteric contributions to knowledge, which are also often not critical of existing knowledge. They argue that researchers’ preference for gap-spotting as a strategy for formulating research questions is a result of their ‘long and extended socialization into the scientific field’ in which ‘most researchers internalize those norms and develop what can be called a gap-spotting habitus (to borrow a term from Bourdieu)’ (Sandberg and Alvesson Citation2011, 37, emphasis in original). These authors maintain that research questions stemming from gap-spotting are not likely to meaningfully contribute to theory development because they do not critically contest existing theories, a claim that we will question.

Sandberg and Alvesson (Citation2011) examined how researchers use the literature to formulate research questions, using a sample of 52 papers from eight randomly selected issues from leading management journals. Three types of gap-spotting were identified. ‘Confusion spotting’ is used when contradictory evidence or claims exist in the literature and the aim of the research – the gap it addresses – explains or attempts to solve competing claims. The second type, which was also the most common in their sample, is ‘neglect spotting’, referring to when a lack of existing research is claimed. Three types of neglect spotting were identified: something was (a) overlooked, (b) under-researched, or (c) lacked empirical support. The third type of gap spotting is ‘application spotting’, which captures claims for a need to extend or complement a specific body of literature. These authors also found that combinations of these gap-spotting types were used.

We share with Alvesson and Sandberg (Citation2011) an interest in the contribution to knowledge that a particular research project may make. They noted the following advice from experienced journal editors in their field:

For inductive studies, articulating one’s motivation not only involves reviewing the literature to illustrate some ‘gap’ in prior research, but also explaining why it is important to fill this gap. The latter is often forgotten. Simply ‘doing what no one else has done’ is not sufficient. To my knowledge, no one has studied leaders’ sock preferences, but it isn’t clear why anyone should. Rationales are necessary. Remember: What might be compelling or obvious to you may not be compelling or obvious to your audience. (Pratt Citation2009, 858–859)

If you can’t make a convincing argument that you are filling an important gap in the literature, you will have a hard time establishing that you have a contribution to make to that literature. (Johanson Citation2007, 292)

In health sciences research, it has been suggested that ‘Research should answer questions that matter’ (Robinson, Saldanha, and Mckoy Citation2011, 1325). In this field, theoretical problematisation does not seem to be of concern and much attention is devoted to systematic reviews of the literature, which is a common process used to identify and prioritise gaps (Hempel, Gore, and Belsher Citation2019; Nyanchoka et al. Citation2020, Citation2019; Robinson, Saldanha, and Mckoy Citation2011). These researchers note that despite gaps being the foundation for research questions and suggestions for future research, there is no well-defined or agreed upon process for identifying them.

For Robinson and colleagues (Citation2011), a research gap exists when only limited conclusions can be drawn from a systematic review. For Scott et al. (Citation2008) this is the definition of an ‘evidence gap’, whereas a ‘research gap’ reflects the further research required for bridging the evidence gap. These researchers developed a framework for research gap identification that includes four main reasons for why a conclusion cannot be reached: insufficient or imprecise information, biased information, inconsistency or unknown consistency, and not the right information. Similarly, Nyanchoka et al. (Citation2020) identified five types of research gaps in health research: information gaps, knowledge/evidence gaps, quality gaps, uncertainties, and patient perspectives gaps. Snilstveit et al. (Citation2016) differentiate between ‘absolute gaps’ where there are no or few studies, and ‘synthesis gaps’ where a considerable amount of primary evidence has not been systematically synthesised. Of course, there could be a range of other research shortcomings, for example around quality and relevance of evidence, but those gaps were not conceptually categorised by these authors.

Jacobs (Citation2011) uses the term ‘problem statement’ and argues that writing this presents a particular intellectual challenge for many, especially new academics. Such difficulties may partially explain why we find the full and clear articulation of a gap statement often overlooked in manuscripts submitted to journals. According to Jacobs a problem statement should consist of four interrelated statements that provide:

the context to the topic (‘principal proposition’);

the issue of concern within this topic (‘interacting proposition’);

the gap between these two propositions (‘speculative proposition’); and

the purpose of study in terms of how it addresses the gap (‘explicative statement’).

In short, problem statements ‘represent a series of statements that should form a logical flow of understanding’ (Jacobs Citation2011, 136). However, a couple of related issues arise. First, the view whereby both the principal and interacting propositions are true but somehow contradictory – which is where the gap is found – is rather restrictive, as a gap can be claimed in other ways. Second, the distinction between the interacting and the speculative propositions is not clear. An alternative option is that these two are combined to form a well-argued gap statement. While this model seems to lack empirical validation or testing, it still offers a useful direction for communicating a study’s importance and merit.

Jacobs (Citation2011) also suggested six interrelated ways to analyse and synthesise information in order to identify, claim and substantiate research problems. Müller-Bloch and Kranz (Citation2015) were interested in characterising research gaps and used an adapted version of Jacobs’s six categories for this purpose. They argued that using such a strategy ‘deepens the understanding of how research gaps may be constituted’ (4). We have further modified this typology for use in our analysis of the empirical data from our present study (see ).

Table 1. A typology of research gaps (adapted from Jacobs [Citation2011] and Müller-Bloch and Kranz [Citation2015]).

Müller-Bloch and Kranz provide a brief definition of each gap type but do not explain how they use their categorisations to identify gaps. These researchers only analysed systematic literature reviews, in which gap identification is key, but their finding of 14 gaps per paper on average raises an epistemological concern regarding the application of this typology. For example, in one extreme case (Mbarika et al. Citation2005) they found 49 gaps, whereas when we examined this paper, we only identified three (all other gaps were effectively explanations and expansions of these three gaps). Nevertheless, even with this important caveat, the theoretical basis, as well as the comprehensiveness of the typology, seem convincing enough for using it as a framework for analysing and categorising gap statements in the higher education literature.

While the categorisation of gaps in published articles may provide some indication in how knowledge progresses in a field of inquiry, determining what might be a worthwhile gap is a more subjective and contested affair, and may differ between disciplines. Thus, of concern is not only identifying gaps but also how to prioritise them. In other words, the feasibility and importance associated with a research gap should be considered. In health care research there is gap prioritisation through a stakeholder approach which takes into account the needs of patients, health care professionals and policy makers (Hempel, Gore, and Belsher Citation2019). This approach to gap prioritisation might be common in healthcare literature, but putting it into practice in a coherent and systematic way still remains a challenge (Nyanchoka et al. Citation2020). There is the option of a parallel path in higher education research as this field also has a number of stakeholder groups: students, academics, managers, research funders, government and the public. Yet we seldom see this approach and it still raises the question about who decides which research proposals are being prioritised for publication or funding, and on what basis?

The more challenging issue then is how to evaluate a gap’s absolute and relative importance rather than what constitutes a gap. Kearney (Citation2017, 394) asked ‘how small can a gap be and still be significant?’ The ostensibly simple dichotomy categorisations of gaps as ‘small’ or ‘large’ seems to involve how much is already known about a particular thing and how important that thing is. Kearney believes a gap can be quite small, but the smaller it is, the more rigorous the research needs to be in order to produce definitive conclusions. In contrast, exploratory studies with tentative conclusions may be acceptable when addressing large gaps in the literature (Kearney Citation2017). Making a significant contribution to the literature is always essential, but according to this view the research design required for filling a gap should be appropriately aligned with the size of the gap. Furthermore, a certain gap may be of much importance, but the research methods for addressing it may be limited. For example, measuring quite abstract ideas, such as ‘teaching effectiveness’ is a case in point. Quantifying social and subjective constructs may be appealing and even potentially useful, but the feasibility of doing so is often limited.

A gap needs to be established logically and convincingly (Jacobs Citation2011) and for that its importance in terms of contribution to knowledge is key. This is more acute and challenging in higher education studies because this is an ‘open-access discipline’ where many who research and publish have academic positions in other fields (Harland Citation2009; Citation2012). While this openness and diversity are seen as positive, much published research is essentially descriptive of practice (Daniel and Harland Citation2018) rather than an attempt to answer something worthwhile to the field. Writing about the research process in higher education, Daniel and Harland acknowledge that it is common to advise novice researchers to search for gaps in knowledge. However, there is an endless number of gaps, especially when seeking to understand human experiences, but not all ‘gaps are equal and good research progresses through choosing the “right” gap’ (Daniel and Harland Citation2018, 123). These authors suggest effective researchers are those able to identify and articulate what is important and what will contribute to knowledge. Following Jones (Citation2003), Daniel and Harland (Citation2018) encourage researchers to test their chosen gap by asking ‘who cares?’ in order to establish relevance and interest, and ‘so what?’ to identify its implication and contribution. Another questions that could be asked is ‘why bother?’ (Rojon and Saunders Citation2012).

Focusing on writing research proposals in education, Mckenney and Reeves (Citation2012) are not concerned with how a gap or a problem is initially identified. Instead, they suggest the research topic needs to be evaluated in terms of its legitimacy (is it addressing a gap in the literature?), ‘researchability’ (are there suitable methods available?), and research-worthiness (will it make a contribution to a recognised concern so that stakeholders would want to invest resources in it?). This conceptualisation of research-worthiness somewhat resonates with the ‘who cares?’ and ‘so what?’ questions. However, it is not clear, and rather restrictive, why the issue at hand must be a recognised concern, as research can be worthy even if recognition of the problem is limited. In this case, however, it might be a challenge to convince others in the research community, or funders, that the issue should be of wider concern.

Taken together, and despite the wide use of gap identification as a rhetorical device across disciplines, the literature on gap identification as a rationale for research and its publication is fairly limited and seems to be of most concern to a few theorists and journal editors. In their role, editors see submissions at a range of qualities and thus have a vantage position for useful insight into how gap claims are made. They also have an inherent responsibility for the quality of the papers they publish and to the discipline, so whether a paper makes a meaningful contribution is key. Of course, quality and contribution are also of importance to all researchers who publish and review papers, as well as to those who teach research methods.

In summary, the literature indicates it is widely expected that a gap will not be merely stated but argued for and substantiated as important and worthy. There are also several types of gaps and different expectations regarding what these entail. While useful, it is still difficult to evaluate the quality of a gap statement and the contribution that may occur from addressing it. In other words, how can we tell strong from weak gaps? While we should be cautious and suspicious towards the fallacy of the exaggerated gap (‘nothing is known’) (Daniel and Harland Citation2018), is a gap justification such as ‘we need a better understanding’ good enough? There may not be definitive answers to these questions, as these depend on particular contexts and topics. However, it is relatively straightforward to examine articles to ascertain how gap statement writing is approached and how these gaps are represented. In the present study, we sought to find out what we could learn from analysing published papers in the top-ranked higher education journals in terms of how they address research gaps.

Methods

This study uses document analysis (Daniel and Harland Citation2018) involving a comparative analysis of outputs from leading higher education journals and focusing on the particular topic of gap identification and substantiation. It can also be characterised as a single topic review (Tight Citation2019). All full-length original research papers were considered for analysis, and these were sought from five top-ranked (according to Google Scholar), specialist, English-language higher education journals as representative of research in the field. While journal selection presents challenges and limitations (see Tight Citation2012), these journals are recognised as influential in the field and have a low acceptance rate of submissions (5–19% according to journals’ webpages), which is an indication of quality. To enhance the study’s validity, two issues from each journal from a period of three years (2019–2021) were randomly selected (using the website random.org). In total, ten issues constituting 124 research articles were examined (see ).

Table 2. Selected journals and issues for analysis.

Initial data analysis was conducted by one researcher, with challenging papers discussed by all three researchers during regular weekly meetings, where consensus over categorisation was sought. Because the justification for the study should appear early on in the paper (Johanson Citation2007), only abstracts and all the text before the methods/study section were reviewed (typically called abstract, introduction and literature review). Data analysis was done using NVivo (Release 1.6) by means of codes and case classifications, which were all predetermined. Codes were divided into two groups: ‘gap statement’ and ‘gap substantiation’. The first group consisted of ‘explicit’ and ‘implicit’ statements, each containing the six gap categories adapted from Jacobs (Citation2011) and Müller-Bloch and Kranz (Citation2015) (see ). One of these categories was assigned to each identified gap in the reviewed papers. The second group addressed the basis on which gaps were claimed by the authors: ‘synthesis of the literature’ (i.e. gap was identified by the authors based on their review of the literature), ‘identified by another researcher’ (i.e. authors cited another publication as the source of the identified gap), or ‘unclear’ (i.e. we could not determine the basis on which a gap was claimed). ‘No gap substantiation’ was captured in the case classifications, which were used to characterise the articles for future comparison. Case classifications included items such as the type of the article (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods, conceptual), gap statement (explicit, implicit, none), location of gap statement (abstract, introduction/literature review). NVivo was then used to cross tabulate codes and classifications.

Data analysis and the assignment of codes presented challenges. Whereas explicit gap statements are those where the term ‘gap’ is used, what constitutes an implicit gap statement was not always obvious. Therefore, identifying implicit statements required a shared understanding of what a gap is. While definitions vary, we conceptualised a ‘gap’ as a rhetorical device to justify research in the form of a claim to some difference or lack in relation to what is and what is deemed to be required. Put simply, a gap is where a claim is made that something of importance is missing.

The application of the gap typology for categorising gap statements was also challenging. While some types of gaps were noticeably different, such as evidence and theoretical gaps, others overlapped and were not easily or decisively distinguishable. Evidence and evaluation gaps are an example of this, but even more challenging was the nexus between knowledge gaps and all others, since there is an underlying element of knowledge in all gaps. Therefore, compared to all other categories, we found the knowledge gap category was less specific and included gaps that did not clearly fit under the other categories. While we did not set out to test the typology itself, overall, we found it sufficiently robust and comprehensive for a meaningful analysis of gap statements in the published literature.

Findings

The dataset of 124 papers consisted of predominately empirical studies (113, 91%), encompassing both primary and secondary data collection and analyses, and a small minority of conceptual studies (11, 9%). One hundred papers (80%) from the sample included explicit or implicit gap statements, of which all but two papers claimed a single gap type (hence the higher total gaps identified – 104). The remaining 24 articles (20%) did not contain a gap statement (see ). Of the articles without a gap statement there were 4 conceptual papers (36% of conceptual papers) compared with 20 empirical papers (18% of empirical papers).

Table 3. Explicit and implicit gap statements for types of higher education articles.

An implicit gap statement was much more common, with 89 papers (72% of total) claiming a gap in this way, when compared with only 15 papers (12% of total) with an explicit gap statement. A theoretical gap was the only type not found in the dataset while knowledge gaps were the most prevalent, accounting for nearly two-thirds of all those claimed. Implicit knowledge statements alone accounted for 57 per cent of all gaps. A typical example from a qualitative paper was:

Student perceptions of teaching quality, as measured through the proxy of the National Student Survey, are core metrics used in the TEF, although there is a lack of research on student perceptions of teaching excellence …

(Lubicz-Nawrocka and Bunting Citation2019, 63)

Inconsistent findings are due to differences in the conceptualization of rigor and in methodological approaches. Thus, further examination of the linkage between academic rigor and students’ intellectual development is warranted.

(Culver, Braxton, and Pascarella Citation2019, 612)

Discussion

Claiming a gap in the literature is the preferred rhetorical device for articulating a rationale for a study in higher education research. Explicit gap statements, which are easier to identify in the text, were a minority, and thus a careful reading was required for identifying implicit gap statements. While in many instances they were easy to find, in some they were not, and we needed long discussions and careful debate as to whether a passage of text was indeed a gap statement. This challenge was exacerbated because only a small minority of authors included the gap in the abstract. As authors, reviewers, or supervisors we never want to see uncertainty around the rationale for and the importance of a study, and so it should not matter whether a gap statement is explicit or implicit as long as it is obvious, and we suggest that it also be included in the abstract.

Table 4. Basis for claiming gaps in the literature.

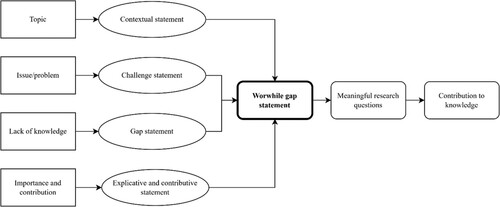

It is easy to understand the intellectual challenge Jacobs (Citation2011) attributes to constructing such statements, but gaps are rarely articulated as a ‘speculative proposition’ positioned between the context (‘principal proposition’) and the issue of concern (‘interacting proposition’). Having such a neatly structured problem statement may be useful for reviewers and readers in terms of clearly identifying the issue at hand, but in practice we found authors used many ways to articulate gaps. Still, we argue that effective communication of research benefits from a clearly stated gap statement. These should be clearly written, and learning how to do this well can be helped by following a series of logical steps. From what we have learned about how gap statements are made in journal articles, we have adapted Jacobs’s (Citation2011) ‘problem statement’ model and propose a more flexible set of ideas for constructing a ‘worthwhile gap statement’, consisting of four sequential statements:

the context to the topic (‘contextual statement’);

the issue of concern within this topic (‘challenge statement’);

what is not or insufficiently known about that concern (‘gap statement’); and

the importance of the gap in terms of the benefit to arise from addressing it (‘explicative and contributive statement’).

The first two steps are identical to Jacobs’s, but their designation is changed to reflect a different relationship to the following statements. Step 3 in both models is the gap statement, but now it is only directly addressing the ‘challenge statement’. The fourth step is more noticeably different. The purpose of the study should be clearly based on the first three statements, and so the last statement should explain the importance of the gap in relation to the issue of concern and claim what contribution addressing the gap would make. These ideas are extended by differentiating a gap statement from a worthwhile gap statement. provides a tool that summarises these arguments:

Assessing the merit of gap claims requires specific subject knowledge, which is a key task for authors, editors and peer reviewers. The breadth and depth of the higher education field meant we could not provide this kind of quality assessment, so instead we examined the approaches taken by authors to substantiate gaps. Perhaps expectedly, synthesis of the literature was the main approach to supporting claims, and reviewing relevant literature is a well-recognised pillar of research. Therefore, not being able to identify any basis for a study in 10 per cent of papers with a gap statement is of some concern.

Also interesting, in only two papers (Danvers, Hinton-Smith, and Webb Citation2019; Hanesworth, Bracken, and Elkington Citation2019) did the authors attribute the gap to other researchers. This is a valid way to substantiate research with the caveat that the work cited as the source for those gaps is sufficiently recent since the gap might have been addressed in the interim. Recommendations for future research can be found in published literature reviews and, increasingly in recent years, in bibliometric analyses that use information technology tools to map publications on a given topic according to different keywords and characteristics (de Oliveira et al. Citation2019). Many empirical articles also include such recommendations. Yet, the worth of doing this must be questioned if these ideas are not used to inform subsequent research. However, it is possible that recommendations are taken up by researchers without an acknowledgment of the source of the idea. This finding also calls into question the common practice of labelling a study ‘exploratory’ and then concluding that more and larger studies are required. We found little evidence for such follow-on research, and while our sample was limited, at the very least it would be safe to argue that this practice is uncommon. This is not a critique of exploratory studies per se, but of what seems to be a deliberate strategy to justify a study by suggesting more research is needed. Be as it may, greater scrutiny and wariness are necessary when evaluating such recommendations in such studies. This situation could also be a reminder for researchers to take advantage of recommendations for future research as a strategy for claiming a worthwhile gap. It should not matter where an idea originated, as long as it is a good idea (and credited to its source).

Although the existing literature addressing research gaps is very limited in scope, it comes from different disciplines, which is an indication of the widespread use of this method of research justification. Throughout the present study we asked what other ways exist for justifying research. Can a study be convincingly justified without the authors claiming something was missing? We do not have a definitive answer to these questions, but the 24 papers in which we could not identify a gap statement could provide a clue. Overall, these papers can be divided into two groups. The first includes those papers without any form of justification. Such articles did not contain any answers to the questions of ‘who cares?’, ‘so what?’, and ‘why bother’? (Daniel and Harland Citation2018; Rojon and Saunders Citation2012). The other group of articles did not contain a justification specific to them, but a problem, an issue, or a debate were presented as a background for the study. We conceptualise this practice as ‘justification by association’; the importance of the topic or problem is mentioned – e.g. the article is about ‘access to higher education’ or ‘student wellbeing’ – rather than stating exactly what it is about these areas that is important to know. As such the study appears to be claiming some significance because it is about a worthy issue, but the latter is merely implied. This practice, in our view, provides insufficient justification since the study contribution remains unknown and it is left solely for the readers to establish what is known and what is not on that topic. Furthermore, justification by association does not demonstrate ownership of the research field by the author because there is no clear demonstration of knowledge in the area of inquiry.

Findings from this study also reflect a focus on empirical research. Conceptual papers account for the smallest group by article type, and no theoretical gap was claimed in any of the 124 papers. This resonates with the notion that while the level of engagement with theory in higher education research has been gradually improving, research in the field remains strongly connected to practice (Tight Citation2015). Theory in education research takes different forms and may serve different purposes. One is informing and improving the translation of empirical research in practice, so having a practice-oriented research agenda need not exclude theorisation (Biesta, Allan, and Edwards Citation2011). We did not examine whether theory was used in the literature review of individual papers, but we can say that theory, in development or critique, was never the rationale given by researchers for their study. Sandberg and Alvesson (Citation2011) argue that research questions based on gap-spotting are likely to be deficient in terms of leading to theory development, but the present study provides an alternative explanation. It is not the use of a gap statement as a rhetorical device that is limiting a contribution to theory building; rather, it is the rarity of seeking and claiming a worthwhile theoretical gap as the basis for research.

Conclusion

Good research requires a clear and convincing rationale (Rojon and Saunders Citation2012), and identifying and claiming a gap has been a widely used approach to justify and prioritise research (Chatterjee and Davison Citation2021; Nyanchoka et al. Citation2020). In this paper we also argued for the importance of ‘worthwhile gap statements’ and provided a model for working towards this. All 124 papers analysed in this study were published in peer-reviewed top-ranked higher education journals. This means they were all evaluated and judged to make a worthy contribution. Accordingly, a high proportion of the papers (80%) claimed a gap in the literature, although it remains unknown how many could be judged as ‘worthwhile’. Such an evaluation would be highly subjective and rather challenging to do. Yet, we did find 10 papers in which it was not clear on what basis a gap was claimed and a further 24 papers in which no gaps were claimed and no other justification beyond ‘importance by association’ was given. As such, we can confidently say that 34 (27%) papers could not possibly have claimed a ‘worthwhile gap’. This is sizable proportion of research published in leading journals.

It is therefore possible to publish without a gap statement or making a claim as to why the research is important, but we believe this is not best practice. Having a clear and good rationale for a study is important for developing a research question in the first place, and then predicting that addressing it will likely contribute substantially to knowledge or practice. Claiming worthwhile gaps is thus crucial for the whole research process and for the advancement of knowledge in a field. Ensuring published research is well justified and makes a contribution is a task for journal editors and peer reviewers (Barczak and Griffin Citation2021), but there is also a collective responsibility to uphold the quality of scholarship in the field more broadly. This may start through teaching and supervision of those new to research in the field, but also requires scholars to reflect on their own work. The data suggested that it is difficult to write an explicit and clearly articulated research rationale, and this resonates with the argument that Jacobs (Citation2011) makes about the intellectual challenge of constructing a problem statement.

In addition to paying more attention to substantiating gap statements, higher education journals could also consider the option of introducing structured abstracts where authors are asked to note the study justification and its contribution. A good abstract should contain the four statements required for indicating a worthwhile gap, namely context, challenge, gap, contribution () (but not necessarily in that order), as well as the study’s methodology and key findings. Doing so is likely to assist readers by communicating more clearly the content of the study and why the study is relevant (Mosteller, Nave, and Miech Citation2004) but more importantly, it would enhance the quality of scholarship in the higher education field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Navé Wald

Navé Wald is a Lecturer at the Higher Education Development Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand. His research focuses on critical thinking in assessment practice, doctoral co-supervision, and students peer review. His teaching interests include supporting those new to research in higher education as well as helping students at all levels to develop their critical skills.

Tony Harland

Tony Harland is Professor of Higher Education in the Higher Education Development Centre, University of Otago, Aotearoa New Zealand. His recent research projects have looked at the ways in which higher education is valued, how teaching values affect students’ education, how undergraduate students learn through doing research, and how assessment affects student behaviour and the quality of their education. Tony teaches research methods in higher education and other topics such as learning theory and peer review.

Chandima Daskon

Chandima Daskon is a Research Fellow at the Higher Education Development Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand. She is a multi-disciplinary researcher with particular interests in qualitative research and research methodologies.

References

- Alvesson, M., and J. Sandberg. 2011. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” The Academy of Management Review 36 (no 2): 247–271. doi:10.5465/amr.2009.0188.

- Alvesson, M., and J. Sandberg. 2013. Constructing Research Questions: Doing Interesting Research. London: Sage.

- Barczak, G., and A. Griffin. 2021. How to Conduct an Effective Peer Review. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Biesta, G., J. Allan, and R. Edwards. 2011. “The Theory Question in Research Capacity Building in Education: Towards an Agenda for Research and Practice.” British Journal of Educational Studies 59 (no 3): 225–239. doi:10.1080/00071005.2011.599793.

- Chatterjee, S., and R. M. Davison. 2021. “The Need for Compelling Problematisation in Research: The Prevalence of the gap-Spotting Approach and its Limitations.” Information Systems Journal 31 (no 2): 227–230. doi:10.1111/isj.12316.

- Culver, K. C., J. Braxton, and E. Pascarella. 2019. “Does Teaching Rigorously Really Enhance Undergraduates’ Intellectual Development? The Relationship of Academic Rigor with Critical Thinking Skills and Lifelong Learning Motivations.” Higher Education 78 (no 4): 611–627. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00361-z.

- Daniel, B. K., and T. Harland. 2018. Higher Education Research Methodology: A Step-by-Step Guide to the Research Process. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Danvers, E., T. Hinton-Smith, and R. Webb. 2019. “Power, Pedagogy and the Personal: Feminist Ethics in Facilitating a Doctoral Writing Group.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (no 1): 32–46. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1456423.

- de Oliveira, O. J., F. F. Da Silva, F. Juliani, L. C. F. M. Barbosa, and T. V. Nunhes. 2019. “Bibliometric Method for Mapping the State-of-the-art and Identifying Research Gaps and Trends in Literature: An Essential Instrument to Support the Development of Scientific Projects.” In In Scientometrics Recent Advances, edited by S. Kunosic and E. Zerem, 47–66. London: IntechOpen.

- Forsberg, E., L. Geschwind, S. Levander, and W. Wermke. 2022. “Peer Review in Academia.” In In Peer Review in an era of Evaluation, edited by E. Forsberg, L. Geschwind, S. Levander, and W. Wermke, 3–36. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hanesworth, P., S. Bracken, and S. Elkington. 2019. “A Typology for a Social Justice Approach to Assessment: Learning from Universal Design and Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (no 1): 98–114. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1465405.

- Harland, T. 2009. “People who Study Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 14 (no 5): 579–582. doi:10.1080/13562510903186824.

- Harland, T. 2012. “Higher Education as an Open-Access Discipline.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (no 5): 703–710. doi:10.1080/07294360.2012.689275.

- Hempel, S., K. Gore, and B. Belsher. 2019. “Identifying Research Gaps and Prioritizing Psychological Health Evidence Synthesis Needs.” Medical Care 57 (no 10): S259–S264. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001175.

- Jacobs, R. L. 2011. “Developing a Research Problem and Purpose Statement.” In In The Handbook of Scholarly Writing and Publishing, edited by T. S. Rocco and T. G. Hatcher, 125–142. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Johanson, L. M. 2007. “Sitting in Your Reader's Chair.” Journal of Management Inquiry 16 (no 3): 290–294. doi:10.1177/1056492607307167.

- Jones, R. 2003. “Choosing a Research Question.” Asia Pacific Family Medicine 2 (no 1): 42–44. doi:10.1046/j.1444-1683.2003.00050.x.

- Kearney, M. H. 2017. “Challenges of Finding and Filling a gap in the Literature.” Research in Nursing & Health 40 (no 5): 393–395. doi:10.1002/nur.21812.

- Kock, F., A. G. Assaf, and M. G. Tsionas. 2020. “Developing Courageous Research Ideas.” Journal of Travel Research 59 (no 6): 1140–1146. doi:10.1177/0047287519900807.

- Lubicz-Nawrocka, T., and K. Bunting. 2019. “Student Perceptions of Teaching Excellence: An Analysis of Student-led Teaching Award Nomination Data.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (no 1): 63–80. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1461620.

- Mbarika, V. W., C. Okoli, T. A. Byrd, and P. Datta. 2005. “The Neglected Continent of IS Research: A Research Agenda for Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of the Association for Information Systems 6 (no 5): 6. doi:10.17705/1jais.00067.

- Mckenney, S., and T. C. Reeves. 2012. Conducting Educational Design Research. New York: Routledge.

- Mosteller, F., B. Nave, and E. J. Miech. 2004. “Why we Need a Structured Abstract in Education Research.” Educational Researcher 33 (no 1): 29–34. doi:10.3102/0013189X033001029.

- Müller-Bloch, C., and J. Kranz. 2015. “A Framework for Rigorously Identifying Research Gaps in Qualitative Literature Reviews.” Paper Presented at the Thirty Sixth International Conference on Information Systems, in Fort Worth.

- Nyanchoka, L., C. Tudur-Smith, R. Porcher, and D. Hren. 2020. “Key Stakeholders’ Perspectives and Experiences with Defining, Identifying and Displaying Gaps in Health Research: A Qualitative Study.” BMJ Open 10 (no 11): e039932. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039932.

- Nyanchoka, L., C. Tudur-Smith, V. N. Thu, V. Iversen, A. C. Tricco, and R. Porcher. 2019. “A Scoping Review Describes Methods Used to Identify, Prioritize and Display Gaps in Health Research.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 109: 99–110. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.01.005.

- Pratt, M. G. 2009. “From the Editors: For the Lack of a Boilerplate: Tips on Writing Up (and Reviewing) Qualitative Research.” Academy of Management Journal 52 (no 5): 856–862. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.44632557.

- Robinson, K. A., I. J. Saldanha, and N. A. Mckoy. 2011. “Development of a Framework to Identify Research Gaps from Systematic Reviews.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64 (no 12): 1325–1330. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.009.

- Rojon, C., and M. N. K. Saunders. 2012. “Formulating a Convincing Rationale for a Research Study.” Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice 5 (no 1): 55–61. doi:10.1080/17521882.2011.648335.

- Sandberg, J., and M. Alvesson. 2011. “Ways of Constructing Research Questions: Gap-Spotting or Problematization?” Organization 18 (no 1): 23–44. doi:10.1177/1350508410372151.

- Scott, N. A., C. Moga, C. Harstall, and J. Magnan. 2008. “Using Health Technology Assessment to Identify Research Gaps: An Unexploited Resource for Increasing the Value of Clinical Research.” Healthcare Policy 3 (no 3): e109–ee27.

- Snilstveit, B., M. Vojtkova, A. Bhavsar, J. Stevenson, and M. Gaarder. 2016. “Evidence & gap Maps: A Tool for Promoting Evidence Informed Policy and Strategic Research Agendas.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 79: 120–129. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.05.015.

- Tight, M. 2012. “Higher Education Research 2000–2010: Changing Journal Publication Patterns.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (no 5): 723–740. doi:10.1080/07294360.2012.692361.

- Tight, M. 2015. “Theory Application in Higher Education Research: The Case of Communities of Practice.” European Journal of Higher Education 5 (no 2): 111–126. doi:10.1080/21568235.2014.997266.

- Tight, M. 2019. “Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Higher Education Research.” European Journal of Higher Education 9 (no 2): 133–152. doi:10.1080/21568235.2018.1541752.

- Tight, M. 2022. “Is Peer Review fit for Purpose?” In In Peer Review in an era of Evaluation, edited by E. Forsberg, L. Geschwind, S. Levander, and W. Wermke, 223–241. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.