Abstract

This study conducted a quantitative study analysis of teacher competence in linguistically responsive teaching (LRT). To assess performance-oriented competence, we used a test instrument with video vignettes and corresponding items based on situation-specific skills perception (What do you perceive?) and decision-making (How would you act if you were teacher in this situation?). Participants were required to respond orally. The research questions focused on LRT competence and the connection between (pre-service and in-service) teachers’ LRT competence and individual characteristics (subjects of study and LRT-relevant teaching experience), LRT-relevant learning opportunities, and beliefs about multilingualism in school and teaching. We found that experienced teachers and those who studied English as a foreign language had higher test scores, and participants with positive beliefs were more likely to perform better on the test. Positive beliefs appear to play a fundamental role in teachers’ identities as linguistically responsive professionals. Also, findings indicate a valid innovative performance-oriented LRT measurement. We suggest a learning environment should be implemented with opportunities to reflect on (pre-service) teachers’ beliefs and creating sufficient space for reflecting on experiences, as professionalization succeeds with self-reflection to raise awareness of blind spots. Future research should focus on the relation of teachers’ actual classroom performance and situation-specific skills. Furthermore, LRT-relevant learning opportunities should be evaluated in detail to learn more about teacher professionalization in this field.

The increasing number of multilingual learners (MLLs) in Germany (Berkel-Otto et al., Citation2021) and many other countries (Wernicke et al., Citation2021) has led to culturally and linguistically diverse student populations (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013; Wernicke et al., Citation2021). Teachers need to be prepared to incorporate this diversity into the curriculum and teach MLLs in a linguistically responsive manner (Cho et al., Citation2020).

Various programs and concepts have been established in teacher education to prepare future teachers to work with MLLs (Wernicke et al., Citation2021). One project that focuses on teachers’ competence in teaching MLLs is DaZKom-Video, which is the first study that focuses on performance-oriented measurement of teacher competence in linguistically responsive teaching (LRT), which we refer to as LRT competence. LRT is a concept (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013) that defines the types of pedagogical knowledge, and skills teachers need to instruct MLLs in mainstream classrooms. These skills include linguistic knowledge, principles of second language learning, and understanding of academic language. LRT also includes fundamental teaching orientations, that is, the linguistic diversity that linguistically responsive teachers focus on and value (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013).

The novel contribution of this study to the literature is the assessment of teachers’ LRT-relevant performance rather than assessing their declarative knowledge. We also aimed to learn more about action-related learning opportunities and about teachers’ need to develop expertise in teaching MLLs. To reach these goals, we elicited spontaneous oral responses from teachers in reaction to video stimuli and assessed the decisions and actions they described in their responses (Lemmrich et al., Citation2020a). In this study, we analyzed the results of the video-based LRT-competence test as well as the results of instruments we used to (1) validate our competence test and (2) evaluate the (correlative) relationships between teachers’ LRT competence and the (a) learning opportunities about LRT, (b) teachers’ beliefs, and (c) their academic background. To validate the innovative oral response format, we also assessed participants’ personality factors (d) to identify whether certain personality types have advantages or disadvantages in taking the LRT competence test. This study was conducted with pre- and in-service teachers across Germany.

To achieve our aims, we divided the rest of the paper into three sections. First, we provide an overview of the theoretical background, the state of the research with a focus on the construct of LRT competence and performance-oriented measurement of competence and introduce our research questions. Second, we introduce our innovative video-based test instrument, the additional scales we use to evaluate learning opportunities and beliefs, and our methods such as scaling the data according to Rasch and running a latent regression analysis. Third, we present and discuss our analysis results, including the relevance of our research on teacher education and training.

State of research and theoretical framework

This theoretical framework introduces our understanding of LRT competence and defines competence and performance.

German as a second language and LRT

Over the past two decades, multilingualism and linguistic and cultural diversity in educational settings have become prominent areas of research (Wernicke et al., Citation2021). Two main research changes have recently occurred in the field of multilingual education.

First, multilingual education now goes beyond a particular type or model (e.g. English as a foreign language, EFL, or German as a second language) and focuses on all students’ individual linguistic repertoires—how they ‘overlap and intersect and develop in different ways with respect to languages, dialects and registers’ (Choi & Ollerhead, Citation2018, p. 1). This inclusive understanding of multilingualism (Schroedler, Citation2021) considers different language registers, regional dialects, and other varieties or accents. Hence, we refer to second language learners as MLLs to reflect linguistically diverse student populations. In this study, we investigate the concept of LRT and how it is applied to all language learners in mainstream classrooms (Lucas et al., Citation2008).

Second, regarding teacher competencies in multilingual education, the emphasis is now ‘on the theoretical and pedagogical understandings of how language is acquired, the instructional strategies that support linguistically diverse students and the integration of language and content’ (Wernicke et al., Citation2021, p. 1), rather than on teachers’ competence in classroom language (Wernicke et al., Citation2021).

LRT can be explained as a concrete set of knowledge and skills that prepares teachers to teach in a linguistically responsive way (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2011). According to Lucas and Villegas (Citation2013), teachers not only need to acquire linguistic knowledge but also need to reflect on their beliefs and be able to assess language in their classrooms. As content in teaching is acquired and expressed through language (Berkel-Otto et al., Citation2021; Woerfel & Giesau, Citation2018), teachers need the ability to identify the language demands of their tasks and know their linguistic expectations. Therefore, they also need to know, where their students are at in terms of language level and/or the subject-specific register, and which activities in the classroom are likely to pose challenges regarding vocabulary or syntactic/semantic features (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013).

LRT emerged from the concept of culturally responsive teaching (CRT) (Villegas & Lucas, Citation2002), which addresses the importance of creating a meaningful learning environment for all students in a classroom. Teachers should have cultural consciousness and affirmative views on (cultural) diversity to address the cultural knowledge and experiences of their students. Consequently, students are able to engage not only content-wise but also socially and emotionally (Acquah et al., Citation2016). LRT extends this conceptual framework and focuses on linguistic aspects to suggest a framework for fields of expertise that teachers need to teach MLLs (Lucas & Villegas, Citation2011). Although we focus on LRT, we are aware that LRT and CRT are linked (culturally and linguistically responsive teaching, Yoon, Citation2023) and teachers with such competence can improve their students’ academic performance (Gay, Citation2010; Ladson-Billings, Citation2009; Lucas & Villegas, Citation2013). Höfler et al. (Citation2023) recently showed in a systematic review that linguistically responsive content teaching can generally support the academic success of primary and secondary school pupils better than content lessons without a language-sensitive focus.

Measuring teachers’ professional competences

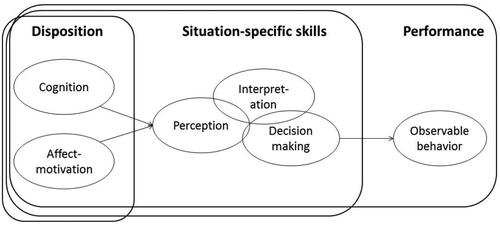

In this study, we follow the idea of competence as a continuum (Blömeke et al., Citation2015; ). According to this approach, professional knowledge (e.g. content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge, Shulman, Citation1986) is considered part of a teacher’s individual disposition, in addition to affec-motivation and beliefs. Teachers’ beliefs are the understanding and assumptions regarding school- and class-related phenomena that teachers consciously or unconsciously believe to be true (Borg, Citation2001; Buehl & Beck, Citation2014; Richardson, Citation1996). Situation-specific skills, such as perception or decision-making, mediate between teachers’ dispositions and performance (Blömeke et al., Citation2015): teachers’ dispositions influence their situation-specific skills (perception, interpretation, and decision-making) and affect their performance.

Figure 1. Competence as a continuum (Blömeke et al., Citation2015, S.9).

We assume LRT competence as a generic competence that all teachers need as part of their professional competencies as content and language are linked. In the context of this study, teachers’ individual dispositions include professional LRT-relevant knowledge (e.g. knowledge about second language acquisition, knowledge about major elements of MLLs’ first languages, Yoon, Citation2023) and beliefs about multilingualism in school and teaching. Situation-specific skills include the ability to perceive LRT-relevant situations in teaching and, as a result, make LRT-relevant decisions in the classroom (e.g. observe when activities in the classroom pose challenges regarding vocabulary or syntactic/semantic features and decide on LRT – relevant support accordingly, Hecker et al., Citation2023). Teacher performance (observable behavior) allows conclusions to be drawn regarding their level of LRT competence (Blömeke et al., Citation2015). The idea of competence as a continuum applies bi-directionally: Teaching experience can serve as a starting point for new knowledge, which is processed by situation-specific skills (deliberate reflection) and transformed into known beliefs and knowledge (Kramer et al., Citation2020; Meschede et al., Citation2017; Santagata & Yeh, Citation2016).

Educational research as well as research on cognition and expertise have focused on perception (referred to as professional vision (Goodwin, Citation1994) in teacher education) as a key link between disposition (e.g. knowledge) and performance (Star & Strickland, Citation2008). Only the perception of relevant teaching situations enables teachers to perform in the classroom (van Es & Sherin, Citation2002). Novice teachers often only describe what they observe and focus primarily on the teacher, whereas experienced teachers identify a relevant event in a complex teaching situation with different events and perspectives and relate what they observed to concepts and theories they know. Furthermore, they give more attention to students’ actions than novice teachers. Therefore, they decide what actions to take more quickly and accurately (Blömeke et al., Citation2015; Santagata & Yeh, Citation2016; Star & Strickland, Citation2008; van Es & Sherin, Citation2002).

We aim to measure LRT-relevant performance to enhance our understanding of teachers’ LRT competence. To capture competence close to performance rather than declarative knowledge, holistic approaches have been used in research on competence and professionalization. Simulated situations that require participants to make spontaneous decisions under time pressure are typical performance assessments (Albu & Lindmeier, Citation2023). We use video vignettes, which appropriately illustrate the complexity of teaching, as existing studies on teacher performance have shown (Blömeke et al., Citation2015; Casale et al., Citation2016). The test items are based on the situation-specific skills of perception and decision-making, and participants were required to give spontaneous oral responses (Lemmrich et al., Citation2020a; see Methods).

Research questions

This study examines the relationship between the results of the LRT-competence test and various other participant characteristics and validation features. Accordingly, we focus on three questions.

What is the relationship between teachers’ LRT competence and their individual and academic characteristics, such as their LRT-relevant learning opportunities?

Previous studies using the DaZKom paper–pencil test have shown that participants with German as their first language scored higher on the test. This is justified by the results of other studies such as the PISA 2012 and the PIAAC, 2013, OECD, Citation2013, Citation2014). Therefore, we expect similar results for this video-based LRT competence test, even though it is envisaged that participants with German as their second language are able to perceive LRT-relevant teaching situations easily.

Based on the results of the two referenced studies, female participants are expected to achieve higher results on the LRT competence test than male participants. This is because there are fundamental differences in the development of comprehension between girls and boys that continue or reoccur beyond infancy (Halpern, Citation2013, Chipere, Citation2014; Maccoby & Jacklin, Citation1978). Female respondents are also more likely to have positive beliefs about linguistic and cultural heterogeneity in school and teaching (Fischer & Ehmke, Citation2019). Moreover, positive beliefs about multilingualism in schools and teaching are associated with high levels of LRT competence (Hammer et al., Citation2016).

Participants who study German (pre-service teachers) or teach German (in-service teachers) are expected to achieve higher LRT competence test scores than other participants because they are offered more LRT-relevant learning opportunities and experience in the field of language education/teaching MLLs (e.g. linguistic skills). The same applies to other language subjects such as EFL. Participants studying EFL are likely to have more learning opportunities in the field of intercultural competence and therefore are more sensitive to LRT, as CRT and LRT are closely connected (see section on German as a Second Language and LRT). We assume that LRT-relevant learning opportunities for participants, such as in specific seminars on LRT, lead to higher test scores, as does specific teaching experience in the field of LRT.

Are there correlations between LRT competence test results and participants’ personality factors?

In the LRT competence test, participants watch a video vignette showing an LRT-relevant teaching situation as a stimulus, after which they are required to respond orally to questions. Participants have to answer spontaneously. This creates time pressure; the participants are deprived of time to structure their thoughts and think of what they know. Personality traits, such as a higher degree of extraversion or openness, might affect their response behavior, which in turn could interfere with the assessment of their LRT competence. However, participants who are more open or extroverted could find it easier to answer orally and to be audiotaped and, therefore, might perform better in the test compared than introverted participants.

To what extent are participants’ beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching predict their LRT-competence test results?

Beliefs are fundamental to professional development (Blömeke et al., Citation2015), and beliefs about multilingualism in the classroom influence future teachers’ actions (Fischer & Lahmann, Citation2020; Pajares, Citation1992). Therefore, in this study, we assess beliefs about multilingualism in school and teaching. This will also help validate the instrument. We expect that positive beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching (Fischer & Ehmke, Citation2020) are linked to high levels of LRT competence. Other studies have arrived at similar conclusions, finding a mediation effect between LRT-relevant learning opportunities and beliefs (Hammer et al., Citation2016, Fischer & Ehmke, Citation2019). Additionally, studies on beliefs have shown that ‘(preservice) teachers may only pay attention to those classroom events that correspond with their existing beliefs about teaching, subject matter and students’ learning’ (Meschede et al., Citation2017, p. 161). Belief is a fundamental factor in knowledge acquisition and processing (Pajares, Citation1992; Ricart Brede, Citation2019). These assumptions suggest that participants with positive beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching are more likely to have greater knowledge and perception and may perform better in the test.

Methods

This section presents our design and provides information on participants, independent and dependent variables, and on the statistical procedure.

Design

We used a cross-sectional design to validate our performance-oriented test instrument. The performance-oriented measurement of LRT competence was conducted using the video vignettes and oral responses.

Besides testing LRT competence, we assayed to get a wide variety of responses to implement these responses into our standard-setting procedure (Hecker et al., Citation2023), as this study was part of a test development process. Validation is a process that checks the plausibility, consistency, and completeness of the assumptions underlying the test instrument and interpretations based on the test results (Kane, Citation2013). In this study, we focused on extrapolation (argument-based-approach, Kane, Citation2013) to explain the test results. Extrapolation refers to the interpretation of test results related to the future performance of participants in real life (in our case, as a teacher in subject-specific instruction). Therefore, we assumed that the performance of participants on the LRT competence test can be used as an indicator of their actual performance as teachers in content classrooms. We examined the discriminant validity (as part of construct validity) to ensure that measurements of one characteristic of this test instrument do not allow conclusions to be drawn about another independent characteristic (Michalos, Citation2014).

During the data collection, the test instrument was supervised by the project staff, and the test leader’s instructions ensured a standardized test procedure. As the video items were answered orally, the participants were placed in different parts of the room (each test run contained a maximum of 30 participants) to ensure sufficient distance between them. All participants worked on all the test parts. First, the video-based LRT competence test was conducted. The video items were presented in a randomly changing order to avoid sequence effects. All other question blocks followed the same order: individual and academic characteristics, LRT-relevant learning opportunities, personality traits (big five), and beliefs about multilingualism in school and teaching.

Participant assignment

Data were collectedFootnote1 between April and July 2019 from 16 locations in every region in Germany—east, west, north, and south—and in the urban and rural areas to ensure that there were no location-related effects on the findings. Data were collected at pre-service teacher trainings at universities, in-service teacher trainings at universities, and in-house teacher training for in-service teachers at schools (public elementary and secondary schools). In addition, teachers or teacher groups who agreed to participate were tested independently. All participants provided their consent for data collection. All data were extracted anonymized.Footnote2

The sample (N = 295) comprised 57% pre-service teachers, 39% in-service teachers, and 4% teacher educators and researchers in the field. shows the distribution of other characteristics within the sample, such as sex, first language, and subject taught or teaching experience.

Table 1. Study sample.

Independent variables

Independent variables in this study are participants’ individual and academic characteristics and LRT-relevant learning opportunities, participants’ personality traits, and participants beliefs regarding multilingualism in school and teaching. All questionnaires were presented in a multiple-choice format and were designed in such a way that every question had to be answered to move on to the next.

Individual and academic characteristics and LRT-relevant learning opportunities

The questions on individual and academic characteristics covered information on sex, first language, subjects of study and/or teaching, and additional qualifications. The scale of LRT-relevant learning opportunities (22 items, α = 0.90) contained LRT-relevant topics (e.g. linguistics and scaffolding) that might have already been addressed in participants’ coursework/training. The scale was based on existing, reliable scales from Ehmke and Lemmrich (Citation2018). The items were developed according to the three dimensions of structural model for LRT competence and its sub-dimensions, such as language-specific register (corresponding topics such as areas of linguistics, German grammar, and differences between oral and written language), multilingualism (e.g. phenomena of second language acquisition, milestones in language development, and linguistic diversity at school), and didactics (e.g. diagnostics of language levels, language support and language training, and support of the language learning process through scaffolding). Respondents answered using a five-point Likert scale (1: not at all to 5: in several courses). The descriptive statistics are provided in and .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Personality traits (Big Five)

Personality factors are included as covariates in this study to test whether certain types of personality have advantages in responding orally. If so, this would distort the measurement of competence. An existing test instrument is used for this purpose (Schupp & Gerlitz, Citation2014), which focuses on the big five personality factors (Rammstedt & Danner, Citation2017): extraversion (outgoing, assertive, active), agreeableness (kind, gentle, trusting), conscientiousness (thorough, responsible, hardworking), neuroticism (anxious, fearful, moody), and openness (imaginative, adventurous, creative) (Goldberg, Citation1990; Rammstedt & Danner, Citation2017). These factors are considered reliable predictors in numerous studies of different objectives and research fields and are used in educational research studies, such as the German National Education Panel (NEPS) (Rammstedt & Danner, Citation2017). With the big five, a broad spectrum of human experience and behavior can be described in a few dimensions (Rammstedt & Danner, Citation2017).

Different tests have been designed to capture these personality dimensions. The difference typically lies in the number of items. In general, more questions on personality traits lead to a more precise depiction of the personality structure. A test version with five items has been shown to achieve appropriate levels, but 10 or 15 items lead to psychometrically better results. This study used the Big Five Inventory-SOEP (Schupp & Gerlitz, Citation2014) in the questionnaire (15 items). It contains three items for each of the five characteristics, which are rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1: does not apply at all to 7: applies fully). The five subscales have the following reliabilities: cautiousness α = 0.66, extraversion α = 0.79, compatibility α = 0.53, openness α = 0.64, and neuroticism α = 0.71. The means and standard deviations of the total scores for the subscales are provided in .

Beliefs regarding multilingualism in school and teaching

Two scales were used to measure the participants’ beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching (Fischer & Ehmke, Citation2020). The instrument was developed based on the literature (Fischer & Ehmke, Citation2019). It has been extensively validated (Fischer, Citation2020) and has good psychometric quality (Fischer & Ehmke, Citation2019). Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale (1: do not agree at all to 4: agree completely). The scales are as follows: (1) multilingualism in the content classroom (7 items, α = 0.83) and (2) responsibility for language support in the content classroom (9 items, α = 0.72). The descriptive statistics are provided in .

Dependent variable

The impact of the independent variables was assessed on the participants’ LRT competence. Given that oral responses are used in this test instrument for performance-related measurements, a distinction in mean test scores should be ensured between competent and non-competent participants.

The video vignettes are 1–3 min long and show LRT-relevant teaching situations. One example is a vignette showing a group of students working together. They need to describe the procedure of an experiment in physics they observed and then discuss it. The teacher does not provide rich and supportive linguistic inputs that help the students articulate their ideas and therefore does not adequately stimulate precise descriptions. The conception of the instrument follows the structural model for LRT competence (DaZKom model; Köker et al., Citation2015) to which dimensions the video situations were assigned. Some of the videos were natural, and some were staged. However, all the staged videos were based on natural teaching situations in school that we (a) had as natural videos but were not allowed to use, or (b) were only available as audio files. The video vignettes were carefully selected during the project and validated using expert ratings (Hecker et al., Citation2020b; Lemmrich et al., Citation2019). In this expert rating (N = 3), the videos were also tested for authenticity, relevance, and fit to the theoretical framework of LRT (Hecker et al., Citation2020a; Lemmrich et al., Citation2019, Citation2020b).

The test items connected to the video vignettes were tested in two successive pilot studies (Lemmrich et al., Citation2019). The items were also divided into three subscales that corresponded to the dimensions of the model: subject-specific register (15 items), multilingualism (4 items), and didactics (5 items) (Lemmrich et al., Citation2020b). However, we combined all items in a one-dimensional measurement scale in this study. The reason is a better model fit in a one-dimensional model. Additionally, the reliabilities of the individual subscales were no longer satisfactory (Lemmrich et al., Citation2019, Citation2020b).

The test was conducted in a computer-based setting on tablet computersFootnote3 (using the Limesurvey application) with shielding headsetsFootnote4 with built-in microphones. The duration of the test was approximately 60 minutes. The LRT competence test contained 12 video vignettes with two corresponding items each (24 items in total) and had a reliability of α = 0.76. The items are based on two situation-specific skills: perception and decision-making, reflecting (a) what do you perceive? and (b) how would you act if you were a teacher in this situation? The test participants gave oral responses, based on the assumption that oral responses increase spontaneity and authenticity and, therefore, enable a measurement close to real performance (Lindmeier, Citation2011, Citation2013). Further details on the response format can be found in Lemmrich et al. (Citation2020a).

The corresponding coding manual for the video test was developed with the help of expert interviews and qualitative content analysis and finalized in elaborate revision loops (Hecker & Nimz, Citation2020). The experts completed the LRT competence test under the same conditions as the later participants. Their responses were evaluated qualitatively and analytically, which formed the basis of the coding manual. For each score, a detailed description, including anchor examples from prior pilot studies, could be found in the manual (Hecker et al., Citation2020b; Lemmrich et al., Citation2020b). On average, satisfactory inter-rater agreement was achieved (Cohen’s kappa κ = 0.76) (Hecker et al., Citation2020b).

Statistical procedure

SPSS 26 and ConQuest (Adams et al., Citation2015) were used for item and scale analyses in this study. SPSS was used to evaluate the frequencies and correlations of the following scales: the results of the LRT competence test, individual and academic data, LRT-relevant learning opportunities, personality traits, and beliefs. The data were scaled according to the Rasch model (Rost, Citation2004), and further analyses, such as latent regression analysis, were conducted using ConQuest, default settings (converge = 0.001, nodes = 50). Pearson’s measurement values were determined using the participants ability estimators (weighted likelihood estimates [WLE]) calculated from the LRT test data. The participants’ answers were based on their ability (LRT competence) and the level of item difficulty (Wilson, Citation2004); the ability estimators considered both. WLEs, therefore, were not about actual response scores but related to the probability of achieving a correct response based on the participant’s ability and item difficulty (Wilson, Citation2004).

From the sample of 302 participants, 7 finished the test without filling in any response and were excluded from all analyses, leaving N = 295 for the analyses. In the analysis of the LRT competence test results, all cases that did not contain evaluable responses, such as audio files with only breathing or fragmentary expressions, were coded as incorrect responses.

To conclude the report on the design, provides an overview of the descriptive results of the instruments used with the LRT competence test. On average, participants in this sample had a medium amount of learning opportunities. The personality factor of compatibility was more prominent among the participants than the rest, whereas neuroticism was the least represented factor within the sample. The participants had positive beliefs about multilingualism in school and teaching, especially regarding responsibility for language support. The participants’ average LRT competence was rather low.

Results

We now present the results of the data analysis. shows the manifest correlations of the LRT scores (WLE) and individual variables, such as individual and academic characteristics, personality traits, and beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching.

Table 3. Manifest correlations and latent regressions of LRT scores in relation to personal characteristics.

RQ1: Relationship between LRT competence and individual and academic characteristics

The manifest correlations between the LRT competence of the participants and their individual and academic characteristics are presented in column 3 of . The results showed that female respondents achieved statistically significantly higher results than male respondents (r = 0.16), and higher LRT competence was statistically significantly correlated with higher LRT teaching experience (r = 0.12) and higher LRT research experience (r = 0.25). No significant associations with LRT proficiency were found for the other variables of individual and academic background. This non-significant relationship was unexpected, especially for the indicator of LRT learning opportunities in university and nonuniversity teacher training. Therefore, we conducted an additional analysis (presented at the end of this section) to determine the extent to which learning opportunities in the different topics are predictive of LRT competence.

The results of the latent regression analysis include all variables at once and report the specific predictions of each variable under the control of the other variables (Model M1, column 4, ). In line with the bivariate correlations, sex and LRT research experience are statistically significant predictors of LRT competence. However, when all other predictors are controlled, LRT teaching experience had no statistically significant effect. Again, we found a significant predictive effect for the language background of the participants. Pre-service teachers with a non-German language background received lower LRT scores than those whose first language was German. The regression analysis indicates that approximately 25% of the variance in LRT scores could be explained by the participants’ individual and academic backgrounds (R2 = 25.0%).

LRT-relevant learning opportunities, single items

As the scale of LRT-relevant learning opportunities did not show any significant effect, we conducted further analysis on the individual topics surveyed (). The results show that respondents who had a higher amount of learning experience on the topic of ‘support of the language learning process through scaffolding’ performed significantly better (r = 0.12) in the LRT competence test. For all other indicators, for example, ‘(sub) areas of linguistics (e.g. syntax, semantics, morphology)’ the regression coefficients were not statistically significant.

Table 4. Bivariate correlations between LRT competence and LRT-relevant learning opportunities.

RQ2: LRT competence and personality factors

RQ 2 asked about the relationship between LRT competence and personality factors. The results reveal that the five scale scores for the main personality factors (openness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extraversion) show no statistically significant correlations with the results of the LRT competence test and no significant predictors in Model 2 of the latent regression analysis (Model M2, column 6, ). These results disprove our assumptions. We assumed that participants who were more open and extroverted might respond better in the oral response format. The regression analysis indicates that only a small portion of the variance can be explained by the personality factors (R2 = 8.0%).

RQ3: LRT competence and beliefs

Regarding beliefs, two scales were evaluated in the analysis: multilingualism in content classroom and responsibility for language support in content classroom. Positive beliefs toward multilingualism in subject-specific teaching (r = 0.21) and positive beliefs concerning responsibility for language support (r = 0.25) correlate highly with measured LRT competence. The results of the latent regression model (M3, column 8, ) also indicate a significant prediction of LRT competence by both indicators of beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching. The explained variance is about R2 = 17.0%, higher than for the personality factors and lower than for individual and academic backgrounds.

Finally, in latent regression Model 4 (, column 10), all the predictors of the three blocks were simultaneously included in the analysis. The pattern of the results is relatively consistent. The results show no effects for personality factors, meaning that LRT competence is independent of the differences in teachers’ big-five personality test scores. The most predictive factors are individual and academic background and pre-service teachers’ LRT-related beliefs. The model explains 26% of the variance in LRT competence (R2 = 26, 0%).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed performance-oriented LRT-competence measurements for pre-service and in-service teachers to evaluate possible predictors of competence. The measures investigated were (1) individual and academic background and LRT-learning opportunities, (2) personality factors, and (3) participants’ beliefs about multilingualism in school and teaching. The analysis yielded the following results.

There is a connection between LRT competence test results and individual characteristics, such as teaching and research experience. Both variables showed statistically significant correlations. Female participants and those who study or teach English achieved higher test scores. The scale of LRT-relevant learning opportunities did not show any significant results, whereas one single item of the scale of learning opportunities did: Support of the language learning process through scaffolding.

Regarding the response format, the analysis of personality factors did not show statistically significant results.

Participants with positive beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching performed significantly better in the LRT competence test than participants with less positive beliefs.

Regarding RQ1, which explores the connection between LRT competence test results and individual and academic characteristics, some results were in line with our theory and assumptions (sex, German as a first language, and teaching experience). However, some results were unexpected. German as a subject of study or teaching did not affect test results, whereas English (EFL) did. We assumed that participants who study or teach German would achieve higher scores in the LRT competence test because of their linguistic education and knowledge of linguistic didactics. Compared with other respondents, participants who study or teach English (EFL teachers) had more LRT experience (personally or in teaching contexts), which confirmed the fundamental role of positive beliefs concerning multilingualism in school and teaching. Germany’s official guidelines for teaching EFL in schools, published by the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs, state that communicative and intercultural competences in other languages are fundamental for participation in a cosmopolitan and mobile society. Furthermore, the guidelines explicitly focus on teaching EFL as a chance for all students to develop language awareness (Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium, Citation2018). Hence, future EFL teachers should be prepared for teaching intercultural competence and raising language awareness and be more aware of linguistic diversity in classrooms than other teachers.

Participants with research experience in this field also had higher test scores than those who did not. Although researchers may not have any teaching experience, they engage with the subject matter more intensively than any other group. They examine actual teaching (e.g. by collecting data through tests or observation) and then propose and apply theories. This fits the theoretical assumptions concerning competence as a bi-directional continuum between dispositions (LRT-relevant knowledge and beliefs), via professional vision and decision-making to performance and via processes of reflection to transform knowledge and beliefs (Blömeke et al., Citation2015; Kramer et al., Citation2020; Santagata & Yeh, Citation2016).

The results indicate what several other studies have suggested: in addition to personal teaching experience, observing teaching and theory-based reflection contribute to teachers’ professionalization (Seidel & Stürmer, Citation2014; Weber et al., Citation2020). No connection was found between the scale of LRT-relevant learning opportunities and LRT competence test scores. Considering the competence model described in the theoretical framework, LRT-relevant learning opportunities should promote professional knowledge. However, weaknesses in situation-specific skills may cause participants to perform poorly on the LRT competence test. Professional (LRT-relevant) knowledge and (LRT-relevant) teaching performance develop as teachers go through the stages of education. However, achievements in the different dimensions of competence do not occur equally (Blömeke & Kaiser, Citation2017). In additional analyses of LRT-relevant learning opportunities based on single items on the scale, only one topic showed a significant correlation with LRT competence: support of the language learning process through scaffolding. Scaffolding is a concrete strategy for organizing the learning process in a lesson and combines many facets of LRT competence, such as diagnostics, language support, and differences between conversational and academic language (Gibbons, Citation2002). Thus, participants who know about scaffolding may have a better and practical understanding of what LRT involves.

The results for RQ2 show no statistically significant relationships between LRT-competence test scores and personality factors. We hypothesized that shy participants would perform worse on the test than extroverted or more open participants, which was not confirmed. The findings indicate that certain personality traits (e.g. openness or extraversion) are either not preferred or disadvantaged in the response format, confirming the fairness of the test. Therefore, the measurement of LRT competence is independent of personality factors, which is an indicator of an innovative and promising test format.

The results regarding the connection between participants’ beliefs and LRT competence (RQ 3) confirm our theory-based expectations. We conclude that beliefs are a fundamental element in the education of linguistically responsive teachers. Studies on beliefs confirm that beliefs are a filter for what we learn and how we perceive our environment (Ricart Brede, Citation2019; Wischmeier, Citation2012). People form beliefs through experience. These beliefs are converted into firm opinions over time. Therefore, beliefs lead to the actions of teachers in their everyday lives (Reusser et al., Citation2011). In the research on teacher competence and professional development, beliefs are considered an element of teacher disposition on the competence continuum, that is, beliefs are part of the bidirectional processes described earlier. Research on beliefs also assumes a direct connection between beliefs and actions and performance (Ricart Brede, Citation2019). Beliefs impact teachers’ actions in the classroom, both in the competence model (perception and decision-making) and performance; in turn, reflection on action affects beliefs (Ricart Brede, Citation2019).

We consider the findings to be an indication of a valid performance-oriented measurement of LRT competence. However, they also show that the acquisition of performance-oriented LRT competence requires specific learning opportunities.

Practical implications

Scholars agree on the need for linguistically responsive teachers, and this study offers insights into how teacher training can incorporate LRT into the curricula. First, videos provide an opportunity for future teachers to develop professional knowledge and vision, further improving competent performance (Gaudin & Chaliès, Citation2015; Seidel & Stürmer, Citation2014). Observing videos on LRT-relevant situations and reflecting on them aids professionalization. In particular, strengthening professional vision seems fundamental because of its central role in competent decision-making and, therefore, performance in the classroom (Blömeke et al., Citation2015). Second, this study provides support for implementing a learning environment with opportunities to reflect on pre-service teachers’ beliefs. Although the connection between beliefs and competence remains unclear (Ricart Brede, Citation2019), studies indicate that beliefs have an impact on teacher performance and education (Fischer & Lahmann, Citation2020; Pettit, Citation2014). The test results yield similar conclusions. In addition to educating (future) teachers in LRT, a greater focus on teachers’ beliefs and how they are developed and shaped is necessary. This can be done, for instance, by evaluating beliefs (Fischer & Lahmann, Citation2020) and creating sufficient space for reflecting on experiences (Ricart Brede, Citation2019). According to Sieland and Jordaan (Citation2019), professionalization succeeds only when one has the ability to self-reflect to raise awareness of blind spots. Third, referring to individual characteristics, such as the subjects of study/teaching, we understand that teacher education must not focus only on linguistic/language knowledge. Test results of (pre-service) teachers who study English as a subject of teaching show that raising language awareness and intercultural competencies among (future) teachers is equally important (Gage, Citation2020; Hu & Gao, Citation2020).

Limitations

We identify three main scientific implications. First, this study assumes that LRT competence is a continuum between disposition and performance, with situation-specific skills in between. We analyzed performance-oriented measurements by evaluating situation-specific skills (perception and decision-making). However, it remains unclear how actual classroom performance is related to situation-specific skills. In expertise research, knowledge is transformed from a conscious, declarative disposition into an unconscious, more intuitive state. Therefore, it is unclear whether the actual performance of expert teachers is congruent with what they verbally express regarding how they would perform (Hecker et al., Citation2020a; Herzog, Citation2018).

Second, further research is required on LRT-relevant learning opportunities. We measured the scale of possible topics/activities that participants may have encountered during teacher training. However, what these LRT-relevant learning opportunities look like (e.g. structure, didactics, methods) remains unclear. Third, from a theoretical and technical point of view, further research on measuring performance or performance-oriented measurement is necessary, because the oral format is time-consuming and more complicated in coding the responses from large samples.

Conclusion and implications for future research

This study suggests that an innovative response format is independent of participants’ personality factors and promises for performance-oriented testing. The results enhances our understanding of factors that foster LRT competence among pre-service teachers. In addition to linguistic knowledge, concrete strategies such as scaffolding and reflection on teachers’ beliefs play a key role in the professional development of linguistically responsive teachers.

Future research should focus on the relation of actual classroom performance and situation-specific skills. As knowledge is transformed into a more intuitive state, actual performance of expert teachers is difficult to capture and is the subject of current research (Hecker et al., Citation2023).

We suggest that research aims should evaluate LRT-relevant learning opportunities for teachers (pre-/post-service) at different teacher education programs at universities across Germany to identify LRT-relevant learning opportunities. A pre-/post-study could evaluate the extent to which video vignettes can be used in teacher education to improve LRT performance. Because teacher education programs in Germany are developed and regulated by federal states’ legislation, teacher education programs in the field of LRT are different in all federal states andeven at the universities (Berkel-Otto et al., Citation2021). Research in Germany should evaluate LRT competence at different locations in relation to the LRT-relevant teacher education programs. Future research should employ a different response format (written and multiple-choice) to facilitate the assessment procedure.

Acknowledgments

This study was developed as part of the DaZKom-Video project. We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Barbara Koch-Priewe, Prof. Dr. Udo Ohm, Dr. Anne Köker, Dr. Sarah-Larissa Hecker, and Stefanie Falkenstern for their cooperation and support.

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Svenja Lemmrich

Svenja Lemmrich is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Leuphana University of Lüneburg. She works at Institute of Mathematics and its Didactics. Her research focuses on multilin gualism/multilingual learners, German as a second language, teachers’ professional competencies and recently on adaptive teaching as a concept to meet the needs of the diverse classroom.

Timo Ehmke

Timo Ehmke is professor for educational research at the faculty of education at Leuphana University of Lüneburg, Germany. His research interests are in the fields of teacher education, culturally responsive teaching, social background, and large-scale assessments.

Notes

1 The German Research Foundation (DFG) states that a study requires ethical approval whenever the participants (1) must endure high emotional or physical strains, (2) cannot be fully informed about the purpose of the study, and/or (3) are patients, who undergo functional magnetic resonance imaging or transcranial magnetic stimulation during the course of the study (https://www.dfg.de/foerderung/faq/geistes_sozialwissenschaften/).

Our study did not affect any of these conditions and therefore did not require ethical approval. However, the participants signed a declaration of consent that contained information about the purpose of our study, handling and processing of data, and data protection.

2 Owing to the sensitive nature of the questions asked in this study, survey respondents were assured that raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared.

3 Samsung Galaxy Tab A (6) 10.1 WiFi Schwarz.

4 Hama 135504 TAB-PF XPAND 10.1 black.

References

- Acquah, E. O., Commins, N. L., & Niemi, T. (2016). Preparing teachers for linguistic and cultural diversity: Experiences of Finnish teacher trainees. In B. Koch-Priewe & M. Krüger-Potratz (Eds.), Die deutsche Schule Beiheft: Qualifizierung für sprachliche Bildung: Programme und Projekte zur Professionalisierung von Lehrkräften und pädagogischen Fachkräften (Vol. 13, pp. 111–129). Waxmann.

- Adams, R. J., M. L. Wu., & M. R., Wilson. (2015). ACER ConQuest: Generalised item response modelling software [computer software]. ACER Press.

- Albu, C., & Lindmeier, A. (2023). Performance assessment in teacher education research-A scoping review of characteristics of assessment instruments in the DACH region. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 26(3), 751–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-023-01167-7

- Berkel-Otto, L., Hansen, A., Hammer, S., Lemmrich, S., Schroedler, T., & Uribe, Á. (2021). Multilingualism in teacher education in Germany: Differences in approaching linguistic diversity in three federal states. In M. Wernicke, S. Hammer, A. Hansen, & T. Schroedler (Eds.), Preparing teachers to work with multilingual learners (pp. 82–103). Multilingual Matters.

- Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J. ‑E., & Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Beyond dichotomies. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 223(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000194

- Blömeke, S., & Kaiser, G. (2017). Understanding the development of teachers’ professional competencies as personally, situationally and socially determined. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 783–812). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Blömeke, S., König, J., Suhl, U., Hoth, J., & Döhrmann, M. (2015). Wie situationsbezogen ist die Kompetenz von Lehrkräften? Zur Generalisierbarkeit der Ergebnisse von videobasierten Performanztests. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik, 61(3), 310–327.

- Borg, M. (2001). Teachers’ beliefs. ELT Journal, 55(2), 186–188. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.2.18

- Buehl, M. M., & Beck, J. S. (2014). The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and teachers’ practices. In H. Fives & M. Gregoire Gill (Eds.), Handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs. Routledge.

- Casale, G., Strauß, S., Hennemann, T., & König, J. (2016). Wie lässt sich Klassenführungsexpertise messen? Überprüfung eines videobasierten Erhebungsinstruments für Lehrkräfte unter Anwendung der Generalisierbarkeitstheorie. Empirische Sonderpädagogik, 8(2), 119–139.

- Chipere, N. (2014). Sex differences in phonological awareness and reading ability. Language Awareness, 23(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.774007

- Cho, S., Lee, H. ‑J., & Herner-Patnode, L. (2020). Factors influencing preservice teachers’ self-efficacy in addressing cultural and linguistic needs of diverse learners. The Teacher Educator, 55(4), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2020.1805835

- Choi, J., & Ollerhead, S. (2018). Plurilingualism in teaching and learning: Complexities across contexts. Routledge.

- Ehmke, T., & Lemmrich, S. (2018). Bedeutung von Lerngelegenheiten für den Erwerb von DaZ-Kompetenz. In T. Ehmke, S. Hammer, A. Köker, U. Ohm, & B. Koch-Priewe (Eds.), Professionelle Kompetenzen angehender Lehrkräfte im Bereich Deutsch als Zweitsprache (pp. 201–220). Waxmann.

- Fischer, N. (2020). Überzeugungen angehender Lehrkräfte zu sprachlich-kultureller Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht: theoretische Struktur, empirische Operationalisierung und Untersuchung der Veränderbarkeit. Leuphana Universität Lüneburg.

- Fischer, N., & Ehmke, T. (2019). Empirische Erfassung eines messy constructs: Überzeugungen angehender Lehrkräfte zu sprachlich-kultureller Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 22(2), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-018-0859-2

- Fischer, N., & Ehmke, T. (2020). Theoretische Abbildung und empirische Erfassung der Überzeugungen angehender Lehrkräfte zu sprachlich-kultureller Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht. DIPF | Leibniz Institute for Research and Information in Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.7477/395:246:1

- Fischer, N., & Lahmann, C. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in school: An evaluation of a course concept for introducing linguistically responsive teaching. Language Awareness, 29(2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1737706

- Gage, O. (2020). Urgently needed: A praxis of language awareness among pre-service primary teachers. Language Awareness, 29(3-4), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1786102

- Gaudin, C., & Chaliès, S. (2015). Video viewing in teacher education and professional development: A literature review. Educational Research Review, 16, 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.06.001

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Multicultural education series (2nd ed.). Teachers College.

- Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning. Heinemann.

- Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216–1229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1216

- Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

- Halpern, D. F. (2013). Sex differences in cognitive abilities. Psychology Press.

- Hammer, S., Fischer, N., & Koch-Priewe, B. (2016). Überzeugungen von Lehramtsstudierenden zu Mehrsprachigkeit in der Schule. In: Koch-Priewe, B., Krüger-Potratz, M (eds.), Qualifizierung für sprachliche Bildung. Programme und Projekte zur Professionalisierung von Lehrkräften und pädagogischen Fachkräften. 147–171. Münster; New York: Waxmann (Die deutsche Schule, Beiheft 13).

- Hecker, S.-L., Falkenstern, S., Lemmrich, S., Ehmke, T., Koch-Priewe, B., Köker, A., & Ohm, U. (2023). Mit Kollaboration zum Standard: Empirisch basierte Bestimmung von Lehrkräfte-Expertise im Bereich Deutsch als Zweitsprache (DaZ). Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 26(1), 161–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-022-01139-3

- Hecker, S.‑L., Falkenstern, S., & Lemmrich, S. (2020a). Zwischen DaZ-Kompetenz und Performanz: Zur Relevanz situationsspezifischer Fähigkeiten und zum Stand ihrer Ausbildung bei Lehrkräften aller Fächer in der Domäne DaZ. HLZ -/Herausforderung Lehrer*innenbildung, 3 (1), 565–584. https://doi.org/10.4119/hlz-3374

- Hecker, S.‑L., Falkenstern, S., Lemmrich, S., & Ehmke, T. (2020b). Zum Verbalisierungsdilemma bei der Erfassung der situationsspezifischen Fähigkeiten von Lehrkräften. Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung, 10(2), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35834-020-00268-1

- Hecker, S.‑L., & Nimz, K. (2020). Expertinnenratings zur Deutsch-als-Zweitsprache-Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. In J. Stiller, C. Laschke, T. Nesyba, & U. Salaschek (Eds.). Berlin-Brandenburger Beiträge zur Bildungsforschung.

- Herzog, W. (2018). Die ältere Schwester der Theorie: Eine Neubetrachtung des Theorie-Praxis-Problems. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 64(6), 812–830.

- Höfler, M., Woerfel, T., Vasylyeva, T., & Twente, L. (2023). Wirkung sprachsensibler Unterrichtsansätze – Ergebnisse eines systematischen Reviews. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 27(2), 449–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-023-01214-3

- Hu, J., & Gao, X. (. (2020). Understanding subject teachers’ language-related pedagogical practices in content and language integrated learning classrooms. Language Awareness, 30(1), 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1768265

- Kane, M. T. (2013). Validating the interpretations and uses of test scores. Journal of Educational Measurement, 50(1), 1–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12000

- Köker, A., Rosenbrock, S., Ohm, U., Ehmke, T., Hammer, S., Koch-Priewe, B., & Schulze, N. (2015). DaZKom-Ein Modell von Lehrerkompetenz im Bereich Deutsch als Zweitsprache. In B. Koch-Priewe, A. Köker, J. Seifried & E. Wuttke (Eds.), Kompetenzerwerb an Hochschulen: Modellierung und Messung: Zur Professionalisierung angehender Lehrerinnen und Lehrer sowie frühpädagogischer Fachkräfte. Verlag.

- Kramer, M., Förtsch, C., Stürmer, J., Förtsch, S., Seidel, T., Neuhaus, B. J. (2020). Measuring biology teachers’ professional vision: Development and validation of a video-based assessment tool. Cogent Education, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1823155

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lemmrich, S., Bahls, A., & Ehmke, T. (2020a). Effekte von mündlichen versus schriftlichen Antwortformaten bei der performanznahen Messung von Deutsch-als-Zweitsprache (DaZ)-Kompetenz – eine experimentelle Studie mit angehenden Lehrkräften. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 36(1–2), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000282

- Lemmrich, S., Hecker, S.-L., Klein, S., Ehmke, T., Koch-Priewe, B., Köker, A., & Ohm, U. (2020b). Linguistically responsive teaching in multilingual classrooms. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, H. A. Pant, M. Toepper, & C. Lautenbach (Eds.), Student learning in German higher education (1st ed., vol. 2020, pp. 125–140). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Lemmrich, S., Hecker, S.-L., Klein, S., Ehmke, T., Köker, A., Koch-Priewe, B., & Ohm, U. (2019). Performanznahe und videobasierte Messung von DaZ-Kompetenz bei Lehrkräften: Skalierung und dimensionale Struktur des Testinstruments. In T. Ehmke, P. Kuhl, & M. Pietsch (Eds.), Lehrer. Bildung. Gestalten: Beiträge zur empirischen Forschung in der Lehrerbildung (1st ed., pp. 190–204). Beltz.

- Lindmeier, A. (2011). Modeling and measuring knowledge and competencies of teachers: A threefold domain-specific structure model for mathematics [München Technical University, Dissertation]; (2010). Empirische Studien zur Didaktik der Mathematik (vol. 7). Waxmann.

- Lindmeier, A. (2013). Video-vignettenbasierte standardisierte Erhebung von Lehrerkognitionen. In U. Riegel & K. Macha (Eds.), Videobasierte Kompetenzforschung in den Fachdidaktiken (pp. 45–61). Waxmann.

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2011). A framework for preparing linguistically responsive teachers. In T. Lucas (Ed.), Teacher preparation for linguistically diverse classrooms: A resource for teacher educators (pp. 55–72). Routledge.

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: Laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory into Practice, 52(2), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2013.770327

- Lucas, T., Villegas, A. M., & Freedson-Gonzalez, M. (2008). Linguistically responsive teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108322110

- Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1978). The psychology of sex differences. Stanford University Press.

- Meschede, N., Fiebranz, A., Möller, K., & Steffensky, M. (2017). Teachers’ professional vision, pedagogical content knowledge and beliefs: On its relation and differences between pre-service and in-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.04.010

- Michalos, A. C. (2014). Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer.

- Niedersächsisches Kultusministerium. (2018). Kerncurriculum für die Grundschule, Schuljahrgänge 3-4, Englisch. https://www.cuvo.nibis.de/cuvo.php?skey_lev0_0=Dokumentenart&svalue_lev0_0=Kerncurriculum&skey_lev0_1=Schulbereich&svalue_lev0_1=Primarbereich&skey_lev0_2=Fach&svalue_lev0_2=Englisch&docid=1153&p=detail_view.

- OECD. (2013). OECD skills outlook 2013: First results from the survey of adult skills. OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2014). What students know and can do: Student performance in mathematics, reading and science PISA 2012 results:/Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Programme for International Student Assessment ((Rev. ed., February 2014, vol. I). OECD.

- Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

- Pettit, S. (2014). Middle school mathematics teachers’ beliefs about ELLs in mainstream classrooms. Sunshine State TESOL Journal 11(1), 25–34.

- Rammstedt, B., & Danner, D. (2017). Die Facettenstruktur des Big Five Inventory (BFI). Diagnostica, 63(1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1026/0012-1924/a000161

- Reusser, K., Pauli, C., & Elmer, A. (2011). Berufsbezogene Überzeugungen von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern (pp. 2). Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf.

- Ricart Brede, J. (2019). Einstellungen – beliefs – Überzeugungen – Orientierungen: Zum theoretischen Konstrukt des Projektes "Einstellungen angehender LehrerInnen zu Deutsch als Zweitsprache in Ausbildung und Unterricht”. In D. Maak & J. Ricart Brede (Eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit: Band 46. Wissen, Können, Wollen - sollen?! (angehende) LehrerInnen und äußere Mehrsprachigkeit (pp. 29–38). Waxmann.

- Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. Handbook of Research on Teacher Education, 2(102–119), 273–290.

- Rost, J. (2004). Lehrbuch Testtheorie - Testkonstruktion. (2., vollst. überarb. und erw. Aufl.). Psychologie Lehrbuch. Huber.

- Santagata, R., & Yeh, C. (2016). The role of perception, interpretation, and decision making in the development of beginning teachers’ competence. ZDM, 48(1–2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-015-0737-9

- Schroedler, T. (2021). What is multilingualism? Towards an inclusive understanding. In M. Wernicke, S. Hammer, A. Hansen, & T. Schroedler (Eds.), Preparing teachers to work with multilingual learners (pp. 17–37). Multilingual Matters.

- Schupp, J., & Gerlitz, J.‑Y. (Eds.) (2014). Big five inventory-SOEP (BFI-S). ZIS - GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences.

- Seidel, T., & Stürmer, K. (2014). Modeling and measuring the structure of professional vision in preservice teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 51(4), 739–771. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531321

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1175860

- Sieland, B., & Jordaan, L. (2019). Kommentar: Lehrerinnen-und Lehrerbildung im Umbruch zwischen Auftrag, alten Schwächen und neuen Chancen (vol. 7, p. 19). Kompetenzentwicklung im Lehramtsstudium durch professionelles Training,

- Star, J. R., & Strickland, S. K. (2008). Learning to observe: Using video to improve preservice mathematics teachers’ ability to notice. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 11(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-007-9063-7

- van Es, E. A., & Sherin, M. G. (2002). Learning to notice: Scaffolding new teachers’ interpretations of classroom interactions. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 10(4), 571–596.

- Villegas, A. M., & Lucas, T. (2002). Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053001003

- Weber, K. E., Prilop, C. N., Viehoff, S., Gold, B., & Kleinknecht, M. (2020). Fördert eine videobasierte Intervention im Praktikum die professionelle Wahrnehmung von Klassenführung? – Eine quantitativ-inhaltsanalytische Messung von Subprozessen professioneller Wahrnehmung. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 23(2), 343–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-020-00939-9

- Wernicke, M., Hammer, S., Hansen, A., & Schroedler, T. (2021). (Eds.). Preparing teachers to work with multilingual learners. Multilingual Matters.

- Wernicke, M., Hansen, A., Hammer, S., & Schroedler, T. (2021). Multilingualism and teacher education: Introducing the MultiTEd project. In M. Wernicke, S. Hammer, A. Hansen, & T. Schroedler (Eds.), Preparing teachers to work with multilingual learners (pp. 1–16). Multilingual Matters.

- Wilson, M. (2004). Constructing measures. Routledge.

- Wischmeier, I. (2012). Teachers’ beliefs: Überzeugungen von (Grundschul-) Lehrkräften über Schüler und Schülerinnen mit Migrationshintergrund–Theoretische Konzeption und empirische Überprüfung. In W. Wiater & D. Manschke (Eds.), Verstehen und Kultur: Mentale Modelle und kulturelle Prägungen (pp. 167–189). Springer; Springer VS.

- Woerfel, T., & Giesau, M. (2018). Sprachsensibler Unterricht. Mercator-Institut für prachförderung und Deutsch als Zweitsprache (Basiswissen sprachliche Bildung).

- Yoon, B. (2023). Research synthesis on culturally and linguistically responsive teaching for multilingual learners. Education Sciences, 13(6), 557. S https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060557