Abstract

Two types of land are found in West Sumatra Province—private land known as state land and collective land known as communal land. In West Sumatra, this type of land is regulated by three strands of law: national law, regional law, and customary law that is upheld by Nagari, the smallest unit of government in West Sumatra. Despite the predominance of tanah ulayat throughout the province of West Sumatra, inconsistent and ineffective government policies and regulations have made its legal status and certification ambiguous. This study discusses customary right policies and their impact on the Minangkabau society. This study aims to address the issue of whether customary rights certification can guarantee the legal protection for communal land in West Sumatra, especially in Lima puluh Kota District, and whether communal land can return to its original status after it has been exploited as a state land (private land) by an investor under West Sumatra Regional Regulation No. 6/2008 on Communal Land Use. This is a socio-legal research drawing on both empirical and normative data analyzed qualitatively and presented in a descriptive evaluative form. The study reveals that the inconsistency between the central, regional, and Nagari governments in regulating customary rights has not only created ambiguity in the registration and certification of communal land, but it has weakened the legal protection of the customary law communities. This is exacerbated when in implementing norms, the authorities fail to capture the spirit of the constitution and/or customary norms, which makes it difficult for communal land to return to its original status once turned into a state land for business purposes. The study also reveals that the management of communal land is hindered by kinship structures in a matrilineal society, especially in the uncle- nephew/niece relationship.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper entitled ‘Legal Protection of Customary Rights under Legal Pluralism and its Impact on the Minangkabau Society: An Empirical Study in the District of Lima Puluh Kota, West Sumatra, is the result of a long collaboration between the author and the traditional community in one of West Sumatra culturally-rich districts. It explores the legislation surrounding the rights over communal land or tanah ulayat in West Sumatra in general and in the District of Lima Puluh Kota. The paper argues that inconsistencies and the lack of harmony between the central government and West Sumatra local government and the relationship between clans prevents/weakens the implementation of strong and coherent regulations and policies to protect rights over communal land in West Sumatra.

1. Introduction

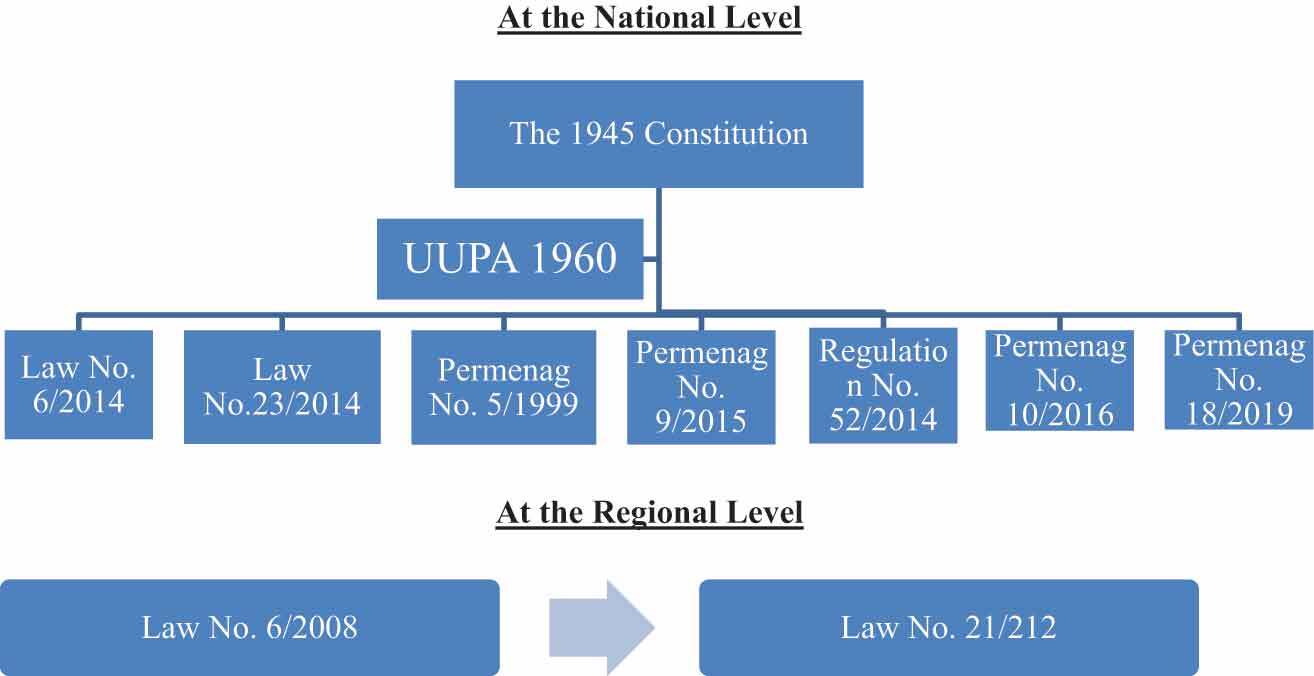

In an agrarian country such as Indonesia, the land is used as both a material and immaterial asset. As a material asset, land is viewed as a strategic economic value not only because of its fertility or the commodities therein but also because of the perpetual rise in its value. As an immaterial asset, land can determine the social status of its owner within the community as pointed out by Achmad Rubaie who claims that land can be a social asset and a capital asset. Land as a social asset is a means of binding social unity between the communities in Indonesia, while as a capital asset, land can be used as an important source of income.Footnote1 As argued at the outset of this paper, two types of land are found in West Sumatra Province—privately owned land known as state land and collectively-owned land known as tanah ulayat or communal land, which belongs to the community as a whole and can not be sold or owned privately. The people of Minangkabau, the major ethnic group in West Sumatra, adhere to a matrilineal kinship system whereby the family relationship pattern goes beyond the parent-child relationship to include the uncle-nephew/nice relationship. It is mainly this relationship that determines land tenure under customary law (hukum adat) in the province of West Sumatra. In addition to customary law, customary rights in West Sumatra are also regulated by national law and regional law. At the national level, these laws include Article 18 B (2) of the 1945 Constitution, articles 3 and 5 of the Basic Agrarian Law (known as Undang-undang Pokoh Agraria (UUPA)) No. 5/1960, Regulation of the Minister of Home Affairs No. 52/2014, Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency No. 10/2016, Article 103 of Law No. 6/2014 on Villages and the Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency No. 18/2019 on Procedures for the Administration of Ulayat Land for the Customary Law Community Unit. Regional regulations, on the other hand, include West Sumatra Provincial Regulation No. 6/2008 on Ulayat Land Use and West Sumatra Governor Regulation No. 21/2012 on the Guidelines and Procedures for Ulayat Land Use for Investments.

In the Minangkabau perspective, a property is an immovable object that includes land, rice fields, plantations, and houses. The possession of these assets confers prestige and earns one respect, dignity from the community. One is considered a migrant or urang malakok for not having any land inheritance (pusaka).Footnote2 Land ownership legitimates one’s status as a native (urang asa).Footnote3 In line with this, Azmi Fendri (Citation2002) observes that under the Minangkabau customary law, there is no such thing as absolute individual land ownership and that land ownership and use are collective in nature. Therefore, there is hardly a transfer of land rights from one individual to another, from one clan to another, or even from one tribe to another.Footnote4 Echoing Soroyo Wignyodipuro (Citation1983) believes that in the socio-cultural context, communal land is a determinant of kinship ties as to whether or not a person is in the customary lineage (keturunan). This shows that in West Sumatra, customary rights are not just economic assets but they also contribute to social stratification and reveal kinship. This is the reason why these rights can not be transferred or certificated.Footnote5

These crucial customary provisions have not been interfered with by positive law until the enactment of Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/Head of BPN No. 9/2015 on the Procedures for Establishing Communal Rights on the Land of Indigenous People and Communities in Certain Areas (abbreviated as Permenag no. 9/2015) which was later repealed and replaced by the Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency No. 10/2016 on the same matter (abbreviated as Permenag 2016). Under these two regulations, the long-existing term ulayat rights (hak ulayat) was replaced by the term communal rights and became the object of certification as communal property rights. Even though such certification is intended for legal certainty, some certification requirements threaten the legal status of communal land as they allow for the transfer of rights. In an attempt to remediate the situation, Permenag 10/2016 was repealed and placed by the Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency No. 18/2019 on Procedures for the Administration of Communal Land for Customary Law Community Units. The main achievement of this latest regulation is that it reinstates the term ulayat rights and the tenure relationship. As a result, customary rights are no longer the object of certification, but must simply be recorded in a land book. Prior to this ministerial regulation, Article 21 of West Sumatra Governor Regulation No. 21/2012 on Guidelines and Procedures for Utilizing Ulayat Land for Investment regulates the restoration of customary rights to their original status after the use of customary rights by investors. Based on the provisions of the Basic Agrarian Law, Business Use Rights or Hak Guna Usaha (HGU) can only be granted on land directly controlled by the State, not communal land. Meanwhile, under West Sumatra Provincial Regulation No. 6/2008 on Ulayat Land Use, customary rights are still the object of certification. In fact, this provincial regulation specifies that communal land can be certificated under three strands of rights i.e., Business Use Rights, Use/Management Rights or Hak Pakai (HP), or Management Rights or Hak Pengelolaan (HP). This shows a lack of harmony and inconsistency between the national and regional governments over the regulation of ulayat land in West Sumatra.

1.1. Research methods

This is a socio-legal research conducted in the District of 50 Kota, West Sumatra Province from Juin to July 2019. It is a descriptive evaluative research. The legal materials consist of primary, secondary, and tertiary legal materials. To collect primary data, a field study was conducted on 5 Nagari (villages) sampled through a purposive sampling technique. Primary data collection techniques include surveys and face-to-face interviews with relevant government officials, business individuals, and adat community leaders such as ninik mamak, penghulu, and Nagari leaders (Wali Nagari) at Kantor Kerapatan Nagari (the smallest unit of government in West Sumatra).Footnote6 Secondary data consist of both regional and national legislation, court observations, questionnaires, and interviews. Data validity was checked by triangulating data sources. Editing and coding were used for data processing, while for data analysis, qualitative analysis was used with inductive and comparative patterns.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Ulayat lands: more than just rights over land

Based on the Minangkabau Customary Law, there are three types of ulayat rights namely Nagari Customary Rights or Hak Ulayat Nagari, Clan/tribe Customary Rights, or Hak Ulayat Suku, and Customary Rights of the People or Hak Ulayat Kaum. Hak Ulayat Nagari is a series of rights and obligations that a Nagari has as the largest alliance over certain communal lands with all its objects, the control of which rests with all ninik mamak as clan leaders in the nagari or the elder leaders or penghulu pucuk. The customary rights of the clan/tribe are a series of rights and obligations of all members of the clan/tribe over certain ulayat lands under the control of their respective tribal leaders. Meanwhile, Customary Rights of the People is owned by a smaller number of groups who jointly control certain ulayat lands under the leadership of the head of inheritance or mamak as the oldest male in the clan from the mother’s side given that the Minangkabau society is founded on the matrilineal kinship principle, as argued at the outset of this paper. Because the number of members in the group/alliance is smaller does not mean that the amount of land is small. Empirically, this is the most predominant type of ulayat rights in West Sumatra.

All of the ulayat lands are a part of inheritance land (pusako) used by the ninik mamak to support the socio-economic needs of their nephews/nieces (kamanakan). According to the Minangkabau tradition, a child receives love and support from two sides: their biological parents and their maternal uncles (ninik mamak). This is illustrated by the maxim “anak digadangkan jo harato pancaharian” (a child is brought up with livelihood assets), but for the ninik mamak, a nephew/niece is brought up with inheritance assets’ (pusako) as translated in the following maxim: “kamanakan digadangkan jo pusako”.Footnote7 If the father does not carry out his economic responsibilities, for various reasons, it is hoped that the mamak can take up this role with the capital of pusako assets.Footnote8 Ninik mamak are not only responsible for the economic well-being of their nephews/nices but they are also the ones whose approval should be sought when the nephew/niece is planning to get married. The parent-child relationship pattern is very common in many countries around the world but the pattern of the uncle-nephew/niece relationship is what sets the Minangkabau society apart. This mamak-kemenakan relationship is so important and powerful in the matrilineal customary order that it impacts the transfer of communal land. Such an order is established based on the custom made by the ancestors who laid the foundations for the Minangkabau tradition. It is referred to as “the custom with dead knots’ (babuhua mati adat), which means that it cannot be changed, and it is meant to protect the customary rights of the Minangkabau people.

Hakimy and Penghulu (Citation1997) claims that based on Minangkabau custom or adat, the highest right to land is ulayat rights, which cannot be sold and may be owned jointly but cannot be owned by private individuals. Therefore, those who own ulayat rights are nagari, an association of nagari, villages (kampuang), tribes, clans, and so on.Footnote9 Similarly, Kurnia Warman (Citation2006) argues that ulayat lands in West Sumatra are inherited from the founders of Nagari. They belong to current and future generations.Footnote10 Although ulayat rights cannot be transferred through the selling of the land or any such asset, they can be pawned due to the following circumstances:

Organizing funerals (maik tabujua tangah rumah);

Holding the wedding of adult nephew/nice (madih gadang ndak balaki);

Renovating a damaged family traditional house (rumah gadang katirisan).Footnote11

Lifting a submerged sterm (mambangkik batang tarandam).

All of the above situations indicate emergencies that require immediate treatment to prevent any prolonged shame that could destroy the family relationship. Maik tabujua tangah rumah (corpse lying in the middle of the house) is a symbolic expression of an emergency related to the death of a member of a family in an indebted state that needs assistance. In such a situation, the inheritance can be transferred. The term Gadih gadang ndak balaki (an unmarried adult girl) refers to the fact that one of the women of the family has not been able to find a husband despite her advanced age and so the ulayat asset is transferred to arrange her marriage. The term mambangkik batang tarandam derives from an ancient Minangkabau tradition of preparing building materials such as wood that is immersed for a long time for house construction. It is believed that soaking the wood for a long time would make it more solid and resistant. The meaning of this symbolic expression refers to the appointment of a penghulu (community leader). When a qualified leader has emerged, funds are required for the traditional inauguration of their appointment and if no other funds are available then the ulayat asset would be pawned.

If the ulayat right is transferred for reasons other than the above, then there is a violation of not only rights but the Minangkabau tradition. As a consequence, the perpetrator would be subject to an ancestral punishment (curse) known as sumpah pasatiran (pasatiran oath) that says: “ka ateh indak bapucuak, ka bawah indak baurek, di tangah digiriak kumbang”, which implies that the offender would live languishingly and useless like a stick of wood that is upwards without a tip, downward without root, and a hollowed trunk.Footnote12 It is believed that the oath of pasatiran will gradually fall upon those who dare to transfer inheritance/ulayat land rights as they violate custom. Every ninik mamak, as a customary leader, must accept and uphold such provisions from generation to generation. Their task is to “stand at the custom door” to protect the customary order from being destroyed or distorted. So strong is the bond of unity in each group or between groups of matrilineal alliances, which ties are based on the principle of high solidarity between citizens, especially in the pattern of mamak-kemenakan relationships. The principle of solidarity is the legal basis for customary provisions in general for the determination of customary violations.

2.2. Legal protection and the certification of ulayat land

Thanks to the advent of the political era known as Era Reformasi (reformation era) that began after the fall of President Sukarto, which led to the birth of decentralization in Indonesia, important steps have been taken at both the national and regional levels to protect customary communities (masyarakat adat) along with their customary rights (hak adat). These steps range from constitutional provisions to national and regional laws, regulations and policies. Although this was meant to bring positive changes to regions/provinces, it has rather weakened and endangered the existence of ulayat rights and adat community (masyarakat adat) in West Sumatra Province. Since the 2000 amendment of the constitution, customary rights have become constitutional rights under Article 18 B (2) of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, which stipulates that the state recognizes and respects indigenous peoples and their traditional rights as long as these rights are still alive and are in accordance with community development and the principles of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia or Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia (NKRI). This constitutional provision is in line with the Basic Agrarian Law No. 5/1960 mentioned earlier. Article 3 of this law says that customary rights shall be guaranteed as long as they are alive and are in accordance with the national and state interests, and do not conflict with laws and other higher regulations.

As promising as these provisions may seem, they do not explain the requirements for the recognition of the existence of customary rights. The criteria for the existence of a customary right were only explained after the enactment of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs/Head of the National Land Agency Regulation No 5/1999 on the Guidelines for Solving Problems of Customary Rights for Indigenous Peoples (Permenag 5/99), which was followed by the Minister of Home Affairs Regulation No. 52/2014 on the Guidelines for the Recognition and Protection of Indigenous Law Communities, which says that the recognition and protection of customary law communities shall be handed over to the Provincial, Regency, and City governments by forming a special committee known as the Customary Law Community Committee or Panitia Masyarakat Hukum Adat (PMHA). In 2015, Permenag 5/99 was revoked following the enactment of Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/Head of BPN No. 9/2015 on the Procedures for Establishing Communal Rights to Land for Indigenous People and Communities in Certain Areas (abbreviated as Permenag No. 9/2015) which was then replaced again by the Minister of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency Regulation No. 10/2016 regarding the same matter (abbreviated as Permenag 2016), as shown in .

Table 1. Illustration of the communal rights over land legislation in West Sumatra

The provisions of these two regulations contradict the provisions of Article 33 section 3 of the 1945 Constitution as well as the Basic Agrarian Law (UUPA) regarding the state’s rights over land. Agrarian reform canceled the State Ownership Rights (Eigendom Staats) based on Domein Verklaring (Domain Declaration) passed during the Dutch colonial administration and replaced it with only the state’s right to control as contained in the above Article 33 section 3 of the 1945 Constitution. The idea of the right to control by the state arises based on customary law that rules out any ownership over ulayat assets including ulayat land, as argued earlier. Similarly, Point II section 1 of the Explanations in the Basic Agrarian Law (UUPA) stipulates that the relationship between the state and land is a kind of customary rights relationship. This applies not only to West Sumatra but also to other provinces throughout Indonesia. Making this same observation is Boedi Harsono (Citation1970) who argues that in Indonesia, the relationship between the state and land is based on a customary rights relationship enhanced at the highest level that affects the entire territory of the state.Footnote13 If such is the regulation of the relationship between the land and the state, then land control rights should not object to certification. However, under the provisions of Permenag 2016, land ownership rights are classified as primary land rights and may be certificated, and for this purpose, the Inventory Team of land control, land ownership, and land use or Inventarisasi Penguasaan, Pemilikan, Penggunaan dan Pemanfaatan Tanah (Tim-IP4T) was formed, that was tasked with inventorying and identifying ulayat lands. One of the remarkable conclusions made by Tim-IP4T after an evaluation is that ulayat lands do exist and that their certification process must stop.

There are advantages and disadvantages to the certification of customary rights. On the one hand, land title certificates provide legal certainty over land tenure. Without certification, it will be difficult if not impossible for customary communities to transfer their ulayat lands because buyers would worry about the legal certainty. But on the other hand, land title certification opens the door for land grab, agrarian conflicts, and more importantly cultural identity destruction. Basically, customary rights are not meant to be transferred, but as a guarantee of life for future generations. The prohibition for the transfer of customary rights is stricter in West Sumatra than in other Indonesian regions. However, it is important to note that certificating land including ulayat land does not necessarily guarantee legal certainty in land tenure. For generations, ulayat lands have existed without title certificates and they will continue to exist as long as they remain guarded and protected by the whole community. They have never been under major threats than they are right now due to ambiguous laws and regulations as explained above. Ulayat land can be exploited for the common good through collective or joint control and the government should only intervene when there is a disturbance of social order and peace.

Agrarian reform does not only concern state land but covers all areas that are under the authority of the state. We believe that the existence of traditional community land rights is not an obstacle to agrarian reform. It is precisely the customary rules in the agrarian sector that are protected by Article 5 of the Basic Agrarian Law. National development should be in line with the preservation of cultural identity and should be intended for the prosperity of all the citizens, including, traditional communities, not the prosperity of those in power or investors. Any policy that does not promote this idea is no policy at all. Laksanto Utomo (Citation2016) argues that marginalizing traditional communities through policies and regulations over the management of natural resources has generated a cultural resistance movement led by traditional communities against persistent assaults on their rights. Echoeing Utomo, Pradana and Dan Yance (Citation2019) claim that there are irregularities in the implementation of the law dealing with customary rights. They observe that although Article 18 of the Constitution claims to recognize the existence of customary communities and their right as long as there are alive and in line with the vision of the unitary state of the Republic of Indonesia, it sounds more like an empty statement as it does not provide any guarantee as to how these right can be guarded and protect again infringements.Footnote14 Ahyar Arigayo (Citation2018) goes further to label such violations as a form of human rights violation by the government.Footnote15

The West Sumatra Provincial Government has tried to provide legal protection to customary rights long before the enactment of the Permenag/head of the BPN mentioned above by enacting two special regulations directly related to ulayat land, namely Regulation No. 6/2008 on Ulayat Land and Its Utilization and Governor Regulation No. 21/2012 on the Guidelines and Procedures for Utilizing Ulayat Land for Investment. These two regulations are a response to various regulations related to agrarian resources that were previously passed by the central government and aim to provide legal protection to customary land. But what is disappointing is the lack of harmony and the contradictions between these regulations. As argued earlier, these two regulations ironically create three categories of rights over ulayat land i.e., Business Use Rights, (Hak Guna Usaha) Use Rights (Hak Pakai), and Management Rights (Hak Pengelolaan). Article 8 Letter A of the West Sumatra Regional Regulation No. 6/2008 says that Nagari Ulayat Land can be registered on behalf of ninik mamak as the rightful person to hold the following rights: Business Use Rights, Use Rights, or Management Rights.

However, according to the Basic Agrarian Law, Business Use Right certificate can only be issued for state land, while Use Rights titles can be given to land owned by private individuals or the state. This implies that for an ulayat land to bear any of these three rights titles, traditional communities must first give up their rights, which is not only in contradiction with the Minangkabau tradition but more importantly, it is a culture denial. With the granting of these rights, ulayat land becomes land directly the propriety of the state or any other individuals. Thus, it is fair to assert that the certification required by Regional Regulation No. 6/2008 and the Permenag 2016 is not beneficial to the matrilineal customary law community in West Sumatra.Footnote16

Fortunately, in 2019, Permenag 2016 was revoked with the enactment of the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency Regulation No. 18/2019 on the Procedures for the Administration of Ulayat Land for Customary Law Community Units (abbreviated as Permenag 2019), which supports the return to the original situation whereby ulayat land was not subject to certification. And for legal certainty purposes, which has long been the argument of many critics, the regulation stipulates that it suffices just to register ulayat land at the local National Land Agency for measuring, mapping and recording. It is important to note this administrative process is only intended for the state recognition of customary land for legal protection, it is not meant for the certification of the land. As discussed above there has been several attempts to regulate and protect communal land rights in West Sumatra at both the national and regional levels as illutrated in the following table:

Amid the ongoing legal pluralism related management of natural resources, and to preserve the idea of regional autonomy, the government should recognize, protect and integrate the values, and rights of every social layer including those of traditional communities. One best way to do so is by accepting and respecting the tradition and local wisdom of these communities. Rules that favor these communities that generally have a low bargaining position must be formulated and implemented with good intentions, not as a collection of words containing empty slogans that are more of a paper tiger.

2.3. Restoration of customary rights

Since the enactment of Law No. 6/2014 on Villages and Law No. 23/2014 on Regional Government, land tenure has become a regional autonomy issue. These laws give more authority to customary communities to restore their customary rights within their territory. Article 76 of Law No. 6/2014 says that ulayat lands are village assets and that should they be seized or under the control of the local governments, they must be returned to the village authorities, except for those that have been used for public facilities. It is worth noting that in West Sumatra, thousands of hectares of land originate from ulayat lands are used by investors for palm oil plantations (outside public interest/public facilities) based on the Business use Rights title. The granting of this right to investors begins with the transfer of rights by the ulayat leadership to the state by obtaining compensation. Without an HGU title, investors engaged in the plantation/fishery sectors cannot obtain business permits. Whether or not customary authorities fully understand the underlining principles of these business activities remains questionable because the terms of the handover contracts are not always discussed openly. It started off as a lease contract but ended up as a state property when the lease expired. This unfortunately offers no guarantee for the restoration of customary rights to their original form. Even Article 4 of the 2019 Minister of Religion explicitly states that the implementation of ulayat rights does not apply to ulayat land that is already owned by individuals or legal entities with a land title.

When asked about the restoration of customary rights as proposed by the 2008 West Sumatra regional regulation during a national webinar on 21 July 2020 the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning Syofyan Jalil avoid answering by arguing that the issue was not as simple as intended in the regional regulation. The minister wants customary rights in Minangkabau to be allocated to individuals to facilitate coordination with the Land Bank which is being planned by the government through the Job Creation Law and the Land Law. This minister’s proposal seems to be contrary to the substance of the 2019 Minister of Religion which he signed himself. Allocating customary rights to individuals to further coordinate with the land bank as proposed by the minister, means that ulayat land would bear land title certificates. As discussed above, this is inconsistent with the Minangkabau matrilineal tradition. No wonder why this proposal was immediately rejected by the Minangkabau public officials in Jakarta during a meeting with the minister.

Law needs to return to its basic philosophy, namely law for humans. He claims that under such a philosophy, humans become the determinant and point of legal orientation. He goes on to say that the law serves humans, not the other way around. The quality of law is determined by its ability to serve human welfare. This causes progressive law to embrace ideology; Law that is pro-justice and pro-people. Government policies and regulations regarding ulayat land in West Sumatra should be more oriented toward prioritizing the collective interests of customary communities and the preservation of cultural identity. Law is only a byproduct of the socio-economic and cultural conditions of society. Law is not a tool for social change. It is merely a means of affirming social reality. In other words, it is inappropriate for matrilineal kinship structures to be forced to change by and for the law.

3. Conclusion

In Indonesia, especially in West Sumatra province, home to the Minangkabau ethnic group, land is used as a strategic economic value as well as an indicator of the social status of its owner in the community. But more importantly, land is used as a cultural identity, a unique family bond between the maternal uncle (ninik mamak) and their nephews/nieces (kaponakan) given the fact that the Minangkabau society adheres to the matrilineal kinship system. It is mainly this relationship that determines land tenure under customary law. Two types of land are found in West Sumatra Province—privately owned land known as state land and collectively owned land known as tanah ulayat or communal land, which belongs to the community as a whole and can not be sold and owned privately. To better protect and regulate these lands, laws, and regulations were passed that include Article 18 B (2) of the 1945 Constitution, articles 3 and 5 of the Basic Agrarian Law (known as Undang-undang Pokoh Agraria (UUPA)) No. 5/1960, Regulation of the Minister of Home Affairs No. 52/2014, Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency No. 10/2016, Article 103 of Law No. 6/2014 on Villages and the Regulation of the Minister of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/Head of the National Land Agency No. 18/2019 on Procedures for the Administration of Ulayat Land for the Customary Law Community Unit. Regional regulations, on the other hand, include West Sumatra Provincial Regulation No. 6/2008 on Ulayat Land Use and West Sumatra Governor Regulation No. 21/2012 on the Guidelines and Procedures for Ulayat Land Use for Investments. These laws have failed to meet the expectation. The vertical/horizontal desynchronization of the statutory regulations regarding customary land management concerning land certification weakens the legal protection of the Minangkabau customary law communities in West Sumatra Province. the inconsistency between the central, regional, and Nagari governments in regulating customary rights has not only created ambiguity in the registration and certification of communal land, but it has weakened the legal protection of the customary law communities in Minangkabau. This is exacerbated when in implementing norms, the authorities fail to understand customary norms and the constitutional provision dealing with customary rights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zefrizal Nurdin

Dr. Zefrizal Nurdin earned his Doctoral Degree in Law from the Faculty of Law of Andalas University, Padang, Indonesia, where he has been teaching agrarian law and many other related subjects for over three decades. His dissertation deals with the legal arrangements for the use of customary land for investment to empower Nagari, the lowest administrative level in the Province of West Sumatra, Indonesia. He has written several scientific papers of which the latest is entitled “Legal certainty in the management of agricultural land pawning in the matrilineal Minangkabau society, West Sumatra”, which explains how the law interacts with the use of agricultural land in the province of West Sumatra. In addition to teaching, Dr. Zefrizal Nurdin also plays in his community as a religious and traditional leader by helping improve agricultural land legislation.

Notes

1. See Achmad (Rubaie, Citation2007). Hukum Pengadaan Tanah Untuk Kepentingan Umum. Malang; Bayumedia Publishing, p. 1–2

2. See Sofyan (Thalib, Citation1978), BPHN, Simposium UUPA dan Kedudukan Tanah-Tanah Adat di Indonesia, Bina Cipta, Jakarta, p. 213

3. See Dt. B. (Nurdin Yakub, Citation1989), Minangkabau Tanah Pusaka Buku kedua, Pustaka Indonesia, Buklittinggi, p. 55–57.

4. See, Azmi (Fendri, Citation2002), Pemanfaatan Tanah Ulayat (Kajian terhadap Perjanjian antara Masyarakat Nagari Sungai Puar dengan Koperasi Agam Timur), Tesis pada Program Magister Kenotariatan Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang, p. 14.

5. See Soroyo (Wignyodipuro, Citation1983), Pengantar dan asas-asas hukum Adat, Gunung Agung, Jakarta, pp. 228–229.

6. See Hilaire Tegnan (Citation2015). Legal pluralism and land administration in west Sumatra: The implementation of the regulations of both local and Nagari governments on communal land tenure. Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. Volume 47, Issue 2.

7. See Idrus Hakimy. Dt. Rajo Penghulu, 1997, Rangkaian Mustika Adat Basandi Syarak di Minangkabau, Rosda karya, Bandung, p. 207.

8. See Zefrizal Nurdin, et al, 2020, Hak ulayat dalam Dinamika Masyarakat Matrilineal Minangkabau, Andalas University Press.

9. See Idrus Hakimy. Dt. Rajo Penghulu, op cit, p. 208.

10. See Kurnia (Warman, Citation2006), Ganggam Bauntuak menjadi Hak Milik, Penyimpangan Konversi Hak Tanah di Sumatera Barat, Andalas University Press, Padang, p. 57

11. See Dt. B. Nurdin Yakub, Minangkabau Tanah Pusako 3, p. 23 and Chairul (Anwar, Citation1997). Hukum Adat Indonesia, Meninjau Hukum Adat minangkabau, Rineka Cipta, Jakarta, p. 94.

12. See Dt. B. Nurdin Yakub 2, op cit, p. 41

13. See Boedi (Harsono, Citation1970), Undang-Undang Pokok Agraria, Sejarah Penyusunan, Isi dan Pelaksanaannya, Djambatan, Jilid 1, Jakarta, p. 149.

14. See Arasy Pradana dan Yance Arizona, 2019, Afirmasi MK Terhadap Juktaposisi Masyarakat Adat sebagai Subyek Hak Berserikat di Indonesia, Jurnal Rehtsvinding, Vol 8. No. 1, p. 264

15. See Ahyar (Arigayo, Citation2018), Perlindungan Hukum Hak atas tanah Adat (Studi Kasus di Prov. Aceh, Kabupaten Bener Meriah), Jurnal De Jure, Vol 18 No. 3, p. 10

16. See Nurdin, Zefrizal & Tegnan, Hilaire. 2019. “Legal Certainty in the Management of Agricultural Land Pawning in the Matrilineal Minangkabau Society, West Sumatra” Land 8, no. 8: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8080117

References

- Anwar, C. (1997). Hukum Adat Indonesia, Meninjau Hukum Adat minangkabau. Rineka Cipta.

- Arigayo, A. (2018). Perlindungan Hukum Hak atas tanah Adat (Studi Kasus di Prov. Aceh, Kabupaten Bener Meriah), Jurnal De Jure, 18(3), 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.30641/dejure.2018.V18.289-304

- Fendri, A. (2002). Pemanfaatan Tanah Ulayat (Kajian terhadap Perjanjian antara Masyarakat Nagari Sungai Puar dengan Koperasi Agam Timur). Tesis pada Program Magister Kenotariatan Universitas Diponegoro.

- Hakimy, I., & Penghulu, D. R. (1997). Rangkaian Mustika Adat Basandi Syarak di Minangkabau, Pt. Remaja Rosdakarya. ed, (pp. 10–22). Rosda karya.

- Harsono, B. (1970). Undang-Undang Pokok Agraria, Sejarah Penyusunan ( pp. 1). Isi dan Pelaksanaannya,Djambatan, Jilid.

- Nurdin Yakub, D. B. (1989). Minangkabau Tanah Pusaka Buku kedua. Pustaka Indonesia.

- Pradana, A., & Dan Yance, A. (2019). Afirmasi MK Terhadap Juktaposisi Masyarakat Adat sebagai Subyek Hak Berserikat di Indonesia. Jurnal Rehtsvinding, 8(1), 1. http://rechtsvinding.bphn.go.id/artikel/2.%20Arasy%20Pradana.pdf

- Rubaie, A. (2007). Hukum Pengadaan Tanah Untuk Kepentingan Umum. Bayumedia Publishing.

- Tegnan, H. (2015). Legal pluralism and land administration in West Sumatra: The implementation of the regulations of both local and nagari governments on communal land tenure. Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 47(2), 312–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2015.1072386

- Thalib, S. (1978). BPHN, Simposium UUPA dan Kedudukan Tanah-Tanah Adat di Indonesia. Bina Cipta.

- Utomo, L. (2016). Hukum Adat. Raja Grafindo Persada.

- Warman, K. (2006). Ganggam Bauntuak menjadi Hak Milik, Penyimpangan Konversi Hak Tanah di Sumatera Barat. Andalas University Press.

- Wignyodipuro, S. (1983). Pengantar dan Azas-Azas Hukum Adat. Gunung Agung.