Abstract

This case study examines how social media accounts use memes and on-the-ground content to create a “real-time” and historical record of the events happening in Ukraine during the 2022 invasion of their country by Russian forces and their allies. Artifacts from the Ukrainian Memes Forces’ Twitter account (among others) provides the memetic artifacts of examination. The grounding of this case study is based on Stuart Hall’s “Readings” to assess how audiences would interpret these messages the memetic artifacts via Twitter and TikTok and using an analysis of the layers within the memes that pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian content creators are producing. The general theme is that pro-Russian content creators are focusing their content on an internal audience under a theme of nationalistic pride, while pro-Ukraine content creators are focusing their content on external audiences under the themes of satire of Russian propaganda and global awareness of the war.

There is something about how a date distills the significance of an event into a data point that people can easily share. The 11th of September in 2001, the 7th of December in 1941, and the 22nd of November in 1963, are three such dates that transmit a collective trauma that U.S. citizens endured in their history. The world added one more such date this year when on the 24th of February in 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine for the second time in a decade. The conventional wisdom was that Ukraine would surrender to Russian forces within 72 hours (Ioanes, Citation2022). However, the “outmanned and outgunned” Ukraine’s military and civil defense forces managed to hold off the “demoralized and disorganized” Russian invasion forces not just for hours, or even days, but months on end (Treisman, Citation2022). One of the by-products of this surprise defense of Ukraine has been the memes developed internally by the Ukrainian government, media, and social organizations as well as externally by those following the conflict.

Typically, conflicts involving Russia are marked by well-trained and well-coordinated disinformation campaigns designed to “muddy the waters” to the point that an accurate conflict narrative is hard to construct (Erlich & Garner, Citation2021; Mejias & Vokuev, Citation2017). This Russian conflict was different because the global audience could see the action on the ground. Real-time reporting from journalists and open-source organizations got their stories out to the public who could access this information through various social media platforms, websites that archive the day-to-day losses, and maps that mark the changing battlefield (Mittal, Citation2022; Sherman, Citation2022). Communication technologies have certainly made relaying this information back much more accessible. Information that was sometimes restricted because reporting on ground was prohibited or frankly too dangerous can now be done by those with access to a mobile device or social media platforms. The radical shift in the emergence of digital online content allows those communicating to do so in real-time to engage with content with an immediacy that was unthinkable only a few decades ago. Furthermore, the traditional control of information and propaganda that was evident in the Russia of old no longer works as people are able to see through the fog of war.

Journalists who report content from war zones attempt to do so with fairness and impartiality. Yet, even with the best intentions and focusing only on the facts, internal bias still exists with each individual’s accumulated experience (Bell, Citation1997). Even with the innate bias, the content presented is valuable information, verified and vetted by those who can see and hear it. This awareness of potential bias helps to maintain credibility of the reporter, while helping those who consume it to be protected by misinformation and propaganda (Christensen & Khalil, Citation2023). Even with the transparent nature of this wartime reporting, the question worth discussing is how can the general public keep track of the complex nature of this conflict while understanding that war can not be reduced to simple slogans.

According to Feldstein (Citation2022), “Technological innovation has helped Ukraine to offset Russia’s conventional military advantage, particularly by increasing the participation of ordinary citizens” (para. 2). Feldstein goes on to explain how the Ukrainians knowledge and use of social media, particularly through memes, videos, and photos have held the attention of the West—and in many cases enlisting support. This online content from those in the war zone is important to study in order to explain what’s happening on the ground, moving beyond the confines of traditional military and government actors. Individual citizen journalism through this online content is giving means to provide critical information from military movement to digital data that could be used post war to prosecute war crimes (Feldstein, Citation2022).

In the current study, memes are explored in order to deeper understand wartime narratives. Memes seem to partly address why the general public can concentrate on the conflict during an era when the public’s focus shifts quickly with each news cycle (Collingwood et al., Citation2018). The compelling nature of memetic content is central to our understanding of how stories in this region go beyond the confines of the battlefield and is worth our time scrutinizing. The power of memes as a future source of sharing war stories is helpful for communication scholars to consider. These foundational units of media became the legacy of a time when the general public could use humor to disrupt the dark nature of war. Discussing the communicative power of memes can enhance our knowledge of how information and understanding of warfare are shared in the social media era. This analysis will use memetic artifacts and social media postings as a case study for examining how future military professionals, war correspondents, and historical scholars could describe and analyze the day-to-day reality of life during wartime (Byrne et al., Citation2017).

1. Memes as messaging

The complexity and fluidity of this topic require a few operational definitions for clarity and concreteness. The first of these concepts is that of memes as a construct. For the purpose of this article, memes will be defined as:

active, multilayered communication constructions that are influenced by social factors and represent a mode of individual expression, in which meaning-making is controlled by both a community that understands that the whole of the work is greater than the sum of its parts and a collective that places that creative content into some part of the broader cultural industry embedded in society (Tilton, Citation2022, p. 31).

This conceptualization of a meme is vital as it reflects that memes do not simply spontaneously generate. Some human actors who observe what is happening in society, frame those observations through their psychological lenses, craft memes to reflect their view of the world, and share these works within their social networks (Shifman, Citation2013; Highfield & Leaver, Citation2016; Milner, Citation2018). Understanding how human nature impacts memetic content allows for a better deconstruction of these artifacts beyond the traditional superficial level of thought that lay audiences tend to approach these mediated works (Eschler & Menking, Citation2018). Scholars applying a rhetorical framing to these artifacts can see these works and attempt to pull back the layers to both fully analyze messaging and appreciate the crafting of memetic content. Pulling back layers from a meme is especially vital as it relates to the second concept that needs to be defined within this research.

Memetic layers of these artifacts are examined through the theoretical lens of wartime communication. The most dominant type of this type of communication would generally be described as persuasive communication. However, it is too easy and too restrictive to label all such communication as propaganda as it adds a simplified means to identify and control messaging within the battlefield that is meant for a public audience (Moran, Citation1979). Propaganda being broadly defined as the simple manipulation of information to narrow the actions conducted by political actors to the point of adding a hypercritical pathos and dehumanization to those actors also limits the more functional work that memes can do in this environment (Laskin, Citation2019).

Most of this type of wartime communication can generally be grounded as a massive information/disinformation campaign run by those nation-states engaged on the battlefield through their government’s communication organizations. Timothy Thomas (Citation2015), a Senior Analyst at the U.S. Army’s Foreign Military Studies Office in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, described these campaigns (especially those run by Russian operatives) as being a combination of:

unleashing Internet trolls who craft content using half-truths and deceptions as a form of pathos manipulation,

maintaining reflexive control in the form of rhetorical constructions that the nation-state knows will cause their enemy to act in a particular way,

using cognitive weapons in the form of false scientific theories, paradigms, concepts, and strategies that influence its state administration in the direction of weakening significant national defense potentials,

spreading outright lies in the form of conspiracies theories designed to weaken the general public’s ability to come together and create a “consensus truth” about the war,

creating a new “constructed” reality about the war that the enemy’s population is happier under direct control of the nation-state invading the country, and

responses to their own insecurity on the public stage designed to counter news stories of war crimes, military failures, and negative public opinion.

Disinformation campaigns as those described by Thomas often work as the counter-narrative to the reporting provided by neutral news agencies covering the war. The mission of a nation-state participating in these types of campaigns is to weaken the resolve of the enemy, confuse outsiders to the point of preventing them from acting against the nation-state, and consolidating support internally by removing protest and focusing on pro-nation-state messaging (Asmolov, Citation2018). Both memetic communication and disinformation campaigns can be best explored through the work of Stuart Hall.

2. Stuart Hall and messaging

Stuart Hall’s (Citation2001) groundbreaking communication and sociological research from the 1970s can point to ways to constructively interpret memes as wartime communication. We need to specifically examine Stuart Hall’s analysis of encoding and decoding communication processes to understand how people who are engaged with memetic communication, disinformation campaigns, and wartime reporting use Hall’s model of reading the media. Hall’s works highlight the role of the encoder (e.g., the meme creator) using meaningful symbols that allow the creator’s message to be clearly understood by the audience. Audience will receive these messages and decode them either:

as the content creator intended them to be received and the audience member accepts the message and its underlying premise (i.e., dominant-hegemonic code),

rejects the message and premises and accepts an alternative framework of reference to understand the message (i.e., oppositional code), or

the audience member has agency to accept and reject elements within the content based on their experiences, beliefs, and values (i.e., negotiated code).

Using Hall’s model of encoding and decoding as a theoretical framework, the case study will focus on the memetic content creation process. Specifically, the grounded research question for this case study is:

RQ1.) What are the fundamental differences between pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian memes that focus on the current Russian-Ukrainian war as it relates to the symbols that both groups use?

Specially, the composition of these visuals and text will be examined among the universe of memetic artifacts gathered throughout the course of the case study.

3. Scope and structure

The scope of this particular case study will focus primarily on both the memes posted by sources [e.g., the Ukrainian Memes Forces Twitter account (@uamemesforces), the Ukrainian Meme Squad (@ukrainian_memes), and various pro-Russian TikTok influencers] to provide a critical overview of the wartime narratives. Balancing the memes with the reality of what is happening on the battlefield means understanding the rhetorical impact of the individual postings and the accounts sending those messages. This rhetorical impact to the global audience is more than the hashtag(s) one uses to organize the narrative, but is part of limiting the effectiveness of disinformation campaigns through strategic media literacy (Daer et al., Citation2014; Huang, Citation2020; Keller et al., Citation2019).

As of 12:01 a.m. on the 1st of June in 2022 [the time writing this case study],Footnote1 the Ukrainian Memes Forces Twitter account has 975 tweets with 971 of those tweets being photos or videos and the Ukrainian Memes Squad Twitter account has 1,744 tweets with 1,137 of those tweets being photos or videos. The analysis of the Russian Tiktokers was made a little more difficult due to the language barrier, the limitations of critical access within the scope of the study (in the form of access of total TikTok postings and removing restrictions based on location), and a lack of some cultural capital of some of the posting. Therefore, the analysis of Russian TikTok influencers needed to be supplemented with works from journalists and other popular sources (Gilbert, Citation2022; Jaessing, Citation2022; Mellor, Citation2022; Millward, Citation2022; Shadijanova, Citation2022; Stokel-Waler, Citation2022).

Memetic artifacts selected within the pool of postings listed above for this case study will be analyzed via their memetic layers (Tilton, Citation2022) to develop some preliminary theory building using artifacts from Twitter (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Yue et al., Citation2018). Specifically, the researchers will be examining the textual and visual layers of the memetic artifacts to ground this content based on information about the war that is accessible to the general public. The rationale for using these artifacts in this study is that they can provide a snapshot of the day-to-day realities as experienced by those externally observing the conflict and those whose lives have been disrupted by the violence. Artifacts were coded using a two-cycle system that allowed for the formation of themes from those selected artifacts (Saldaña, Citation2015).

4. Pro-Ukraine content for external memetic audiences

A basic examination of the overwhelming amount of memes produced related to the war points to a common trend among the content. Memes supporting Ukraine during the conflict are more likely than not connecting with the broader global audience through the memes’ cultural and contextual layers. Content produced by those supporting Russia are more likely than not using cultural and contextual references within the memes that have a strong significance to Russians or pro-Russian supporters and have limited impact to the broader global audience.

There are a few artifacts to explain the broadening of memes that support Ukraine. One of the more popular templates used by accounts supporting Ukraine (especially the Ukrainian Memes Forces Twitter account) is the “This is Ultra Lord” memetic template. The cultural significance of this memetic template is how it highlights an object or idea in the first panel in an attempt to make it popular. This template comes from the Nickelodeon show “Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius,” where one of the characters attempts to share the same action figure over-and-over again during show-and-tell, thus boring the class and making the action figure less important in the audiences” (and his classmates’) mind. The online context of this template is “to mock groups that repeatedly made identical claims or presented the same object” (Star, Citation2022).

Denoting the textual and visual layers of the memes hits on a crucial theme of the “This is Ultra Lord” template and is a common theme of the most popular memes supporting Ukraine, which is that the memes are focused on a global audience as a means of gaining support for the Ukrainian cause. The text in the presented artifact follows the textual format of the meme with virtually no deviation from the most of the presentations of the “This is Ultra Lord” template. Therefore, a global audience (especially those familiar with “Jimmy Neutron” series and the motion picture based on the series) would know what the meme is saying and could determine a basic reading of the meme, even without the benefit of being familiar with the series in question. The visuals (independent from the cultural elements that “Jimmy Neutron” brings into the meme) can be simply understood as an elementary school student participating in a show and tell in their class with the teacher’s (Mrs. Fowl) exasperation of the student (Sheen or his proxy in the meme) showing the same item or idea week after week with no changes. As long as the person viewing the meme had childhood experiences with primary schooling being one of the main modes of socialization and having an understanding of children sharing important objects from the home to the rest of their class, the meme will resonate with the meme’s viewer.

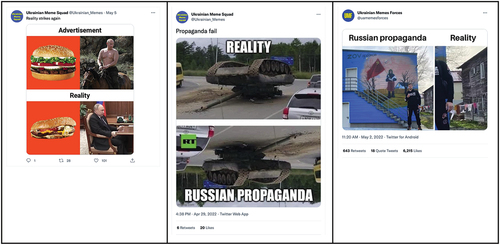

Another common theme among the meme accounts is how these accounts mock the Russian’s presentation of the “truth” and “reality” of what is happening in Ukraine during the invasion. For example, Ukrainian Memes Forces has 38 different postings related to the reality of the warFootnote2 and 191 postings related to truth.Footnote3 Ukrainian Meme Squad has 17 different postings related to the reality of the war.Footnote4 One of the mechanisms that meme creators use is the “reality” vs. “non-reality” (e.g., advertisements, Russian propaganda, etc.) comparisons to make a case that the Russian invasion is not going as smoothly as being claimed by Russian government figures and organizations. The “Presented vs. Reality” memetic template uses simple visuals to make the case in a clear manner to the viewer so that they understand what the central messaging is of the meme (i.e., Figure ).

Figure 2. Pro-Ukraine memes using the reality vs. non-reality comparison memetic template to mock the statements being made by Russia through its official and non-official social media channels.

The contextual layer of this type of meme follows the traditions of a compare and contrast memetic template, whereas the memetic format highlights the hypothetical nationalist strength of Russia in contrast with the result of their military operation in Ukraine (Paul & Vengattil, Citation2022). It is consistently used in a similar manner to the “This is Ultra Lord” memes. Instead of mocking an individual politician or groups, the “reality of the war” memes mock past narratives of both Russian military strength, economic stability, and tactical knowledge. The compositional layer of these memes is parallel to the 2 × 2/four-panel memetic template, designed to offer the viewer both a visual frame of reference for comparing two ideas (e.g., DrakePosting, “Ewww vs. Hmm”, Jeremy or Boris, or Clueless Padme) and the thematic means of thinking about the ideas present in the meme (e.g., Lost, Character Development, “Water, Earth, Fire, Air”, or “Things That Don’t Exist”) with the four panels providing structure for the meme (Dubey et al., Citation2018).

Ultimately, the cultural layer hits on points that would resonate with viewers based on how they, to paraphrase Stuart Hall’s (Citation2001), read the memes. If the viewer supports Ukraine in the form of the dominant read that the rest of the world would see as the hegemonic view, the memes might be read in the cultural layer as a representation of Russian propaganda using Western ideology as the means to describe what is taking place in Ukraine (e.g., the leftmost artifact in Figure is a classic example of restaurants misrepresenting the quality of their food in advertisements). If the viewer supports Russia in the form of the oppositional read of the meme, the viewer might read the memes as the fake news that Western media is spreading about the special operation that is happening in Ukraine (Cushion, Citation2022).

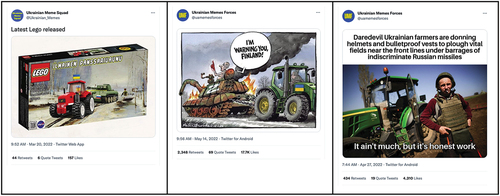

The final set of artifacts to note regarding pro-Ukrainian memes striking a chord with the global audience is a memetic element that is referenced specifically in 293 postsFootnote5 and more than 70,000 references generally.Footnote6 This element is the Ukraine’s Agricultural Division, which is a humorous reference to when Ukrainian farmers towed captured Russian tanks for the benefit of the Ukrainian armed forces (Brown, Citation2022). A common theme among this collective of memes is the conflict between the rural, low-tech nature of the Ukrainian farmers making headway against the model of the military-industrial complex that is Russia (Gershman et al., Citation2018). Most of the various memes that would fit with distinctive, diametric differences between the two countries (e.g., Figure ).

Figure 3. Pro-Ukraine memes presenting a version of the “Ukraine Agricultural Division” memetic element as a Lego set (left), a political cartoon (central), and using the “But It’s Honest Work” textual layer as an additional memetic element (right).

One of the main reasons this memetic template is worth noting in this case study is directly related to the amount of news coverage given to this particular meme. As reported by Matthew Gault (Citation2022) for Vice News, “Like St. Javelin and the Ghost of Kyiv before it, the humble tractor has become a symbol of Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s invasion. Videos and pictures of tractors hauling away Russian armor have gone viral on social media.” Chris Brown (Citation2022) in his story for CBC told the tale of the Ukraine farmers by stating “Ukraine’s farmers now have the fifth-largest army in Europe—or so goes a dark joke on the internet, a reference to all the captured Russian military equipment they’ve towed off the battlefield. In a country desperate to keep its spirits up in dire times, the near-daily social media posts featuring Ukrainian farm tractors recovering Russian tanks, trucks and missile launchers that got stuck in their muddy fields have certainly helped.” The cultural layer of this memetic collective reinforces the “resourcefulness and creativity” trope (Cooper, Citation2022) of the Ukrainian people. Ukrainian farmers using tractors to capture tanks and other Russian military vehicles is one of the iconic images from this war, along with a video of a citizen from the Zaporizhzhia Oblast region of Ukraine removing a landmine from a well-traveled road with his bare hands (Suciu, Citation2022).

5. Pro-Russia content for internal memetic audiences

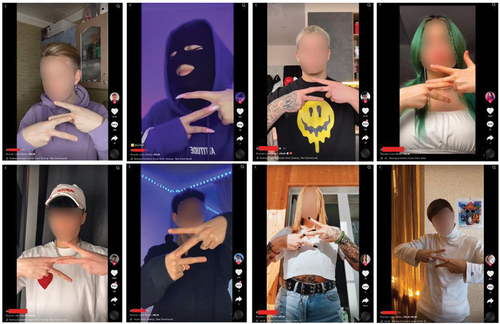

In contrast, the Russian memes have not come from Instagram (as that service is still blocked in Russia as of June 1) nor Twitter (as Russia has all but eliminated local use of the service), but rather TikTok (Ghaffary, Citation2022). TikTok is still active in the country as the company has followed its “anti-fake-news” mandates from the government, which allows the government to determine what is “fake news” and threatens the work that journalists are doing in the country (Benton, Citation2022). This vacuum of external news sources has led to the Russian people getting more of their information about the war from Russian influencers on TikTok.

Abbie Richards (Citation2022), a researcher for Media Matters, denoted the consolidation of Russian information about the war under the hashtag #RLM (Russian Lives Matter). The use of “identical captions and in-video text” led Richards to conclude “that they were the result of some degree of organization” with the likely source of the coordination coming from the Kremlin or other Russian government actors. Most of the influencers use the same phrases that would seem to be for an English speaking audience (e.g., Figure ), however most of the time is shown while the song “Katyusha” was being played. The use of this song represents an issue with the cultural layer, as it is a Russian folk song that would have no cultural significance to those not familiar with Russian culture. The song is one of the most famous melodies of Soviet-era musical propaganda, as it is directly connected to the weapons that the Russian army uses to this day (Geldern & Stites, Citation1995; Prenatt & Hook, Citation2016).

Figure 4. Pro-Russian TikTok influencers presenting their “Russian Lives Matters” with the same phrasing on the front of “Russophobia,” Donbas, “hate speech,” cancelling [sic] sanctions, Luhansk, Infowars, and nationalism.

![Figure 4. Pro-Russian TikTok influencers presenting their “Russian Lives Matters” with the same phrasing on the front of “Russophobia,” Donbas, “hate speech,” cancelling [sic] sanctions, Luhansk, Infowars, and nationalism.](/cms/asset/d33d41cd-35dc-4cf3-8946-e5a5b6731de2/oass_a_2193440_f0004_oc.jpg)

Another theme of Russian influencers is the continuous use of “Z” in their postings (Shadijanova, Citation2022). The rationale for the use of Z is embedded in the rationale that Russian memes are for an internal audience. While the letter Z is not used in the Cyrillic alphabet, the symbol has some connection to the sense of Russian nationalism. In their article for the “Wall Street Journal,” Evan Gershkovich and Matthew Luxmoore (Citation2022) noted that “In Russian, the word ‘for’ is written as ‘za,’ and the Defense Ministry has flooded Instagram with posts saying ‘for peace,’ ‘for our guys,’ ‘for victory,’ all using the English letter Z.” Another internalized interpretation of the use of the letter Z came from NPR reporter Jeff Dean (Citation2022), “Some speculate that the ‘Z’ could stand for ‘zapad,’ which means west in Russian. Some have snidely suggested that the symbol stands for other words such as ‘zhopa,’ meaning ass in a reference to stiff Ukrainian resistance.”

Figure 5. Pro-Russian TikTok influencers forming the Latin Alphabet glyph Z while performing a TikTok dance to Rae Sremmurd’s song “Swang.”

Figure 6. Photos of Russian schoolchildren forming the letter Z.

Beyond being a simple icon that can represent the difference between the Russian and Ukrainian military to avoid confusion destroying the wrong tank or drone (as both countries use many of the same weapons on the battlefield) or even for easy visual for photojournalists to highlight when taking pictures of the destruction on the ground (Gershkovich & Luxmoore, Citation2022), the symbol has been a rallying cry that can easily be used by TikTok influencers (e.g., Figure ) and schoolchildren (e.g., Figure ) to show their support for the war and the Russian troops fighting in Ukraine (Beardsworth, Citation2022). Therefore, the cultural layer is grounded in the sense of Russian nationalism being the primary message that one is expected to show as a Russian citizen without criticizing the actions that the government is taking.

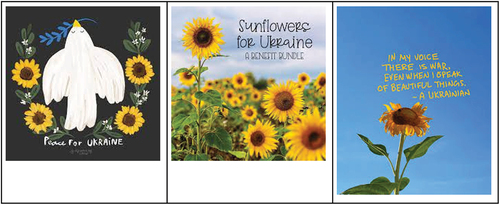

6. Russian oppositional content for hybrid memetic audiences

The work of Stuart Hall’s (Citation2001) is useful for framing the opposition to the war within Russia on Instagram. A clear example comes from an Russian “socialite and food blogger” (Sauer, Citation2022) Veronika Belotserkovskaya when she used her Instagram platform to mock a “Putin’s Army” propaganda video by noting “How good it is that both of my grandfathers, who have been through the war from and before, (Ukrainian and Russian) do not see this horror.Footnote7” Another of the counter-propaganda elements found in Belotserkovskaya’s account and others who oppose the war use sunflowers and the colors blue and yellow. Sunflowers are the national flower of Ukraine. They were made famous via a viral video in which an Ukrainian woman tells one of the occupying soldiers to “Take these seeds and put them in your pockets, so at least sunflowers will grow when you all lie down here.” (Sharma, Citation2022). The visual is a relatively easy element to add to memes and other forms of digital content, thus making it a simple way to support Ukraine on a social media platform (e.g., Figure ). Going back to Hall’s work, this memetic element, which references the woman standing up to the Russian soldier, acts as a guidepost to find others who support Ukraine and counters the Russian hegemonic narrative about the “special operations” that are happening (Kofman et al., Citation2022).

Figure 7. A few examples of the use of sunflowers in Instagram posting showing support for Ukraine.

Blue and yellow, beyond being the colors of the Ukrainian flag, acts as another key visual element within the counter-propaganda memes. These two primary colors give the memetic creator a clear representational point within the meme. The two colors can be applied to characters that would be recognized by a global audience, thus allowing the character’s traits, behaviors, and values to be attached to the country (Tilton, Citation2022). Yellow and blue can be combined with text for a simplistic meme or attached to characters from popular culture (e.g. Figure ). Meme creators who can implement this fundamental element of design in the form of color are more likely to tap into arguably one of the “most powerful communication tools in the designer’s toolbox” (Hagen & Golombisky, Citation2016, p. 47). The impact of using these two colors as an abstract representation of Ukrainian culture is powerful because it draws the attention of the viewer, while invoking an emotional response based on the viewer’s connection to Ukraine and its flag.

Figure 8. A few examples of the use of blue and yellow in memes to present support for Ukraine.

7. Reframing memes through Hall

Examining the perceived relationships between these memetic content creators and their audiences, as defined throughout this article, beyond the symbolic uses within memetic artifacts, comes back to Hall’s thoughtful critique of past communication models and conceptualizations. The use of memetic artifacts within this conflict is not exclusively under the control of the memetic content creator, but instead as part of a more critical conversation conducted by the community at large. The additional media references in this work show in some detail how the underlying understandings associated with this conflict have shifted when more content enters the public sphere of social media.

Another theme in Hall’s work relevant to this discussion is the denotation that whatever the embedded message in crafted memetic content can not always be declared as a transparent transmission with crystal-clear reception from the creator to the intended audience. The center message within a meme will have an abstract concept within it that the creator is trying to express, but the abstract idea is often shifted when it meets the concrete mode of expression as a digital artifact and the analysis of the community who will spread the message or ignores the content as being at the irrelevant relic of the noise that is found online (Tilton, Citation2022).

Finally, Hall’s scholarship is centered on the concept that the audience is not merely a passive recipient of whatever message is being transmitted, nor will they mindlessly accept the content as a realistic representation of the facts of a given event or issue. Instead, audience members (when they have the agency to choose a variety of sources to gather information about a topic) can judge the validity of the artifact and determine if the work is a reasonable representation of the truth and share it with limited critique, a falsehood that can act as the basis for a conversation about perceived misinformation about the topic, or should simply be ignored as a useless mediated work that does not need to go any further (Hall, Citation2001).

The memetic artifacts selected for this article reflect these three Hall’s thematics. Each meme began with a concept of expression related to the Ukraine-Russia war. Those expressions were framed with the intent of the memetic content creator based on an obvious position and potential conceived reactions from a targeted audience (Thomas, Citation2015). Crafting those expressions into the memes does make the messaging more abstract, but the use of mediated layers within the memes narrows the possible interpretations (e.g., the Ultra Lord mediated layers from Figure highlights a repeated rhetorical element by a public figure that “rings hollow” based on how it is presented in the meme). How the audience interprets the memes will impact if it is shared, be given a reaction, or scrolled past in the pursuit of more relevant information associated with the conflict.

Figure 1. Pro-Ukraine memes using the “This is Ultra Lord” memetic template to mock the rhetoric of Olaf Scholz (left), the Chancellor of Germany, not sending promised aid to Ukraine, and Vladimir Putin (center and right), President of Russia, for using war-like rhetoric in his speeches. Each posting has more than 8,000 likes and 500 retweets.

8. Conclusion

The nature of the difference between Ukrainian use of social media and the Russian response can be pinned down to the leadership of both countries when it comes to focusing their media on their given audience. Kyle Chayka (Citation2022) for the New Yorker highlights the main difference, “In a speech on February 24th, the Ukrainian President, Volodymyr Zelensky, a former actor and skilled social-media user, acknowledged as much, imploring Russian TikTok users along with ‘scientists, doctors, bloggers, standup comedians’ to step up and help stop the war. On TikTok, Ukrainians appear to viewers less as distant victims than as fellow Web denizens who know the same references, listen to the same music, and use the same social networks as they do.” There is a sense that Ukrainian meme creators are framing the war as Russia invading a Western country and the citizens are using the tools to get their experiences and messages out to a global audience (i.e., using elements from popular Western culture as the foundation for the memes that they create and resonate with the global audience), whereas pro-Russian military and government actors through the content they are creating or sharing are focusing on the theme that Russian citizens must support the war effort as it is their national duty as a citizen. Counter-propaganda meme creators are using satire (among other techniques) to expose flaws in the messaging and weaken the overall misinformation campaign via directly confront claims within the memes and other forms of digital content produced by those pro-Russian military and government actors online.

The influence of memetic content over the past decade has marked a new mode of community interaction and collective information sharing in society via online communication. This influence can be especially shown when nation-states enter into broad economic, military, or political conflicts. When future communication scholars look at the memes that focus on wars (like the one happening between Russia & Ukraine), memes will tell a small portion of the narrative. Scholars will need to take apart the various layers within memes and examine them using news stories, public accounts, and government dispatches to highlight what is an accepted truth, spotlight the propaganda for what it is, and present the real-life stories of those that survived the horror that is life during wartime. Memes, like other forms of media, act as snapshots during this period of time. Scholars must use the correct tools to determine if those snapshots are illustrations of an imagined/revisionist version of the conflict or clear and truthful photographs of the hard horrors of these brutal events.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shane Tilton

Shane Tilton, Ph.D., is the Irene Casteel Endowed Chair of Education, Professional, and Social Sciences and the Program Lead for the Writing and Multimedia Studies program at Ohio Northern University. His latest book, “Meme Life,” focuses on the social, cultural, and psychological aspects of memetic communication. He also serves as an advisor for Northern Review, WONB Radio, Geek Therapeutics, Ohio Northern Institute of Civic and Public Policy, the ONU chapter of the Society for Collegiate Journalists, and the Center for Society and Cyberstudies. In 2018, he was awarded the Young Stationers Award by the Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers for his service to the field of communication and media education. Tilton was the first American in the 600 year history of the Company to be awarded with such an honor

Alisa Agozzino

Alisa Agozzino, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Public Relations at Ohio Northern University. As the PR program head, she has taught over 16 different classes within the major and developed a social media minor for any major on campus. She has received numerous awards for teaching, including the international Pearson Award for Innovation in Teaching with Technology

Notes

1. All accounts were archived via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org/web/20220531201507/https://twitter.com/uamemesforces and https://web.archive.org/web/20220601175746/https://twitter.com/Ukrainian_Memes).

References

- Asmolov, G. (2018). The disconnective power of disinformation campaigns. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26508120

- Beardsworth, J. (2022, March 17). In Russia’s pro-military ‘Z’ campaign, Children are placed front and center. The Moscow Times, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/03/17/in-russias-pro-military-z-campaign-children-are-placed-front-and-center-a76976

- Bell, M. (1997). TV news: How far should we go? British Journalism Review, 8(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/095647489700800102

- Benton, J. (2022, March 7). “An information dark age”: Russia’s new “fake news” law has outlawed most independent journalism there. Nieman Lab. https://www.niemanlab.org/2022/03/an-information-dark-age-russias-new-fake-news-law-has-outlawed-most-independent-journalism-there/

- Brown, C. (2022, March 18). From capturing Russian tanks to humanitarian aid, Ukraine’s farmers step up for war effort. CBCnews. https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/ukraine-farmers-1.6387964

- Byrne, D., Frantz, C., Harrison, J., & Weymouth, T. (2017, April 8). Life during wartime (2003 remaster). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jLwZvg46jms

- Chayka, K. (2022, March 3). Ukraine becomes the world’s “first TikTok war”. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/watching-the-worlds-first-tiktok-war

- Christensen, B., & Khalil, A. (2023). Reporting conflict from afar: Journalists, social media, communication technologies, and war. Journalism Practice, 17(2), 300–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1908839

- Collingwood, L., Lajevardi, N., & Oskooii, K. A. (2018). A change of heart? Why individual-level public opinion shifted against Trump’s “Muslim ban. Political Behavior, 40(4), 1035–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9439-z

- Cooper, H. (2022, March 30). Ukrainian forces are using their home-turf knowledge to stymie Russia, the top U.S. general says. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/live/2022/03/03/world/russia-ukraine/ukraine-military-strategy-russia?smid=url-share

- Cushion, S. (2022, March 11). Russia: The west underestimates the power of state media. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/russia-the-west-underestimates-the-power-of-state-media-178582

- Daer, A. R., Hoffman, R., & Goodman, S. (2014). Rhetorical functions of hashtag forms across social media applications. Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on The Design of Communication CD-ROM, (16), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1145/2666216.2666231

- Dean, J. (2022, March 9). The letter Z is becoming a symbol of Russia’s war in Ukraine. But what does it mean? NPR. Retrieved June 14, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2022/03/09/1085471200/the-letter-z-russia-ukraine

- Dubey, A., Moro, E., Cebrian, M., & Rahwan, I. (2018). Memesequencer: Sparse matching for embedding image macros. Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference on World Wide Web - WWW ’18, 1225–1235. https://doi.org/10.1145/3178876.3186021

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Erlich, A., & Garner, C. (2021). Is pro-Kremlin disinformation effective? Evidence from Ukraine. The International Journal of Press/politics, 28(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211045221

- Eschler, J., & Menking, A. (2018). “No prejudice here”: Examining social identity work in starter pack memes. Social Media + Society, 4(2), 205630511876881. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118768811

- Feldstein, S. (2022, Dec. 7). Disentangling the digital battlefield: How the internet has changed war. Texas National Security Review. https://warontherocks.com/2022/12/disentangling-the-digital-battlefield-how-the-internet-has-changed-war/

- Gault, M. (2022, March 16). The tractor has become a symbol of Ukrainian resistance. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/n7n5ed/the-tractor-has-become-a-symbol-of-ukrainian-resistance

- Geldern, J., & Stites, R. (1995). Mass culture in Soviet Russia: Tales, poems, songs, movies, plays, and folklore, 1917-1953. Indiana University Press.

- Gershkovich, E., & Luxmoore, M. (2022, March 8). How the letter Z became a Russian pro-war symbol. The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-the-letter-z-became-a-russian-pro-war-symbol-11646675508

- Gershkovich, E., & Luxmoore, M. (2022, March 8). How the letter Z became a Russian pro-war symbol. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-the-letter-z-became-a-russian-pro-war-symbol-11646675508

- Gershman, M., Gokhberg, L., Kuznetsova, T., & Roud, V. (2018). Bridging S&T and innovation in Russia: A historical perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 133, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.03.014

- Ghaffary, S. (2022, March 4). Russia continues its online censorship spree by blocking Instagram. Vox. https://www.vox.com/recode/22962274/russia-block-instagram-facebook-restrict-twitter-putin-censorship-ukraine

- Gilbert, D. (2022, March 11). Russian Tiktok influencers are being paid to spread Kremlin propaganda. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/epxken/russian-tiktok-influencers-paid-propaganda

- Hagen, R., & Golombisky, K. (2016). White space is not your enemy: A beginner’s guide to communicating visually through graphic, web & multimedia design. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hall, S. (2001). Encoding/decoding. In M. G. Durham & D. Kellner (Eds.), Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks (pp. 163–173). essay, Blackwell Publishers.

- Highfield, T., & Leaver, T. (2016). Instagrammatics and digital methods: Studying visual social media, from selfies and gifs to memes and emoji. Communication Research and Practice, 2(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2016.1155332

- Huang, A. (2020). Combatting and defeating Chinese propaganda and disinformation: A case study of Taiwan’s 2020 elections. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/combatting-and-defeating-chinese-propaganda-and-disinformation-case-study-taiwans-2020

- Ioanes, E. (2022, February 27). Putin’s baffling war strategy. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2022/2/27/22953539/ukraine-invasion-putin-russia-baffling-war-strategy

- Jaessing, C. (2022, March 17). The ‘Tiktok war’: Social Media Influencers take over Russia-Ukraine news. globalEDGE Blog: The ‘Tiktok war’. https://globaledge.msu.edu/blog/post/57113/the-‘tiktok-war’–social-media-influencers-take-over-russia-ukraine-news

- Keller, F. B., Schoch, D., Stier, S., & Yang, J. H. (2019). Political astroturfing on Twitter: How to coordinate a disinformation campaign. Political Communication, 37(2), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1661888

- Kofman, M., Lennon, O., Minakov, M., & Tabarovsky, I. (2022, March 9). The Russian war in Ukraine: The situation after two weeks. Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/russian-war-ukraine-situation-after-two-weeks

- Laskin, A. V. (2019). Defining propaganda: A psychoanalytic perspective. Communication and the Public, 4(4), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047319896488

- Mejias, U. A., & Vokuev, N. E. (2017). Disinformation and the media: The case of Russia and Ukraine. Media, Culture, & Society, 39(7), 1027–1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716686672

- Mellor, S. (2022, March 7). Russian TikTok influencers promote the war in Ukraine with a hypnotically repetitive message. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2022/03/07/russian-tiktok-influencers-propaganda/

- Millward, D. (2022, March 11). White House turns to Tiktok influencers to counter Russian misinformation on Ukraine. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2022/03/11/white-house-turns-tiktok-influencers-counter-russian-misinformation/

- Milner, R. M. (2018). The world made meme: Public conversations and participatory media. MIT Press.

- Mittal, V. (2022, March 11). Military equipment losses provide insight into Russia-Ukraine War. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/vikrammittal/2022/03/10/military-equipment-losses-provide-insight-into-russia-ukraine-war/?sh=6c0630fe6f59

- Moran, T. P. (1979). Propaganda as pseudocommunication.ETC: A Review of General Semantics, 36(2), 181–197.

- Paul, K., & Vengattil, M. (2022, April 11). How Meta fumbled propaganda moderation during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/technology/how-meta-fumbled-propaganda-moderation-during-russias-invasion-ukraine-2022-04-11/

- Prenatt, J., & Hook, A. (2016). Katyusha: Russian multiple rocket launchers 1941-present. Osprey.

- Richards, A. (2022, March 11). A pro-Russia propaganda campaign is using over 180 TikTok influencers to promote the invasion of ukraine. Media Matters for America. https://www.mediamatters.org/tiktok/pro-russia-propaganda-campaign-using-over-180-tiktok-influencers-promote-invasion-ukraine

- Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

- Sauer, P. (2022, March 17). ‘It is not possible to stay quiet’: Putin’s first victim of ‘fake news’ law speaks out. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/17/veronika-belotserkovskaya-putin-fake-news-law-first-victim-russia-ukraine

- Shadijanova, D. (2022, April 23). Pro-war memes, Z symbols and blue and yellow flags: Russian influencers at war. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2022/apr/23/z-symbols-pro-war-memes-ukrainian-flags-russian-influencers-ukraine

- Sharma, S. (2022, February 25). Ukrainian woman tells Russian soldier to put sunflower seeds pocket so they bloom. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/ukraine-russia-soldier-woman-confrontation-b2022993.html

- Sherman, J. (2022, April 7). Russia’s war on Google and Apple Maps. Slate Magazine. https://slate.com/technology/2022/04/russia-apple-google-maps.html

- Shifman, L. (2013). Memes in Digital Culture. MIT Press.

- Star, P. (2022, May 3). This is Ultra Lord. Know Your Meme. https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/this-is-ultra-lord

- Stokel-Waler, C. (2022, February 27). The first Tiktok war: How are influencers in Russia and Ukraine responding? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2022/feb/26/social-media-influencers-russia-ukraine-tiktok-instagram

- Suciu, P. (2022, March 2). Real or fake: Video of farmer stealing Russian tank, landmine removed with bare hands, and comparisons of Putin to Hitler trending. https://www.forbes.com/sites/petersuciu/2022/03/02/real-or-fake-video-of-farmer-stealing-russian-tank-landmine-removed-with-bare-hands-and-comparisons-of-putin-to-hitler-trending/?sh=355647c843ec

- Thomas, T. (2015). Russia’s 21st century information war: Working to undermine and destabilize populations. Defence Strategic Communications, 1(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.30966/2018.riga.1.1

- Tilton, S. (2022). Meme life: The social, cultural, and psychological aspects of memetic communication. Leyline Publishing.

- Treisman, D. (2022, April 18). Putin unbound. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-04-06/putin-russia-ukraine-war-unbound

- Yue, L., Chen, W., Li, X., Zuo, W., & Yin, M. (2018). A survey of sentiment analysis in social media. Knowledge and Information Systems, 60(2), 617–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10115-018-1236-4