Abstract

Pedagogical leadership has been widely recognized as an essential factor in improving educational quality. Different studies point to it as the second most influential element in student performance and outcomes after teaching practice. Although the evaluation of principal leadership is an important tool that could help to find ways to improve the effectiveness of principal leadership, the design of such evaluation tools has always been a challenge. On the other hand, when we refer to pedagogical leadership in the context of Higher Education, we find that the limited number of studies suggests that research is still insufficient. Therefore there is a need to continue to deepen this field of research, which will allow us to further explore pedagogical leadership in Higher Education, providing results that will have an impact on the effectiveness of organizational development and its improvement in all dimensions of the institution, as well as on the performance and results of the students. This study aims to translate the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED) into Spanish and adapt it to the context of Higher Education so that we can have a reliable and effective evaluation instrument that not only allows us to continue to study pedagogical leadership in this educational stage, but also to be able to find areas for improvement, to improve both the results of the students and the Higher Education educational institutions themselves.

1. Introduction

Pedagogical leadership oriented to the improvement of the student’s performance and results, is widely recognized as an important factor in the improvement of educational quality. Indeed, if on the one hand the teaching staff is the principle factor related to student learning, leadership emerges as another factor that will greatly influence the performance of students, since it can create a series of conditions and contexts in which the faculty can better execute their work and students can improve their learning (Anderson, Citation2010).

In this sense, it is worth noting how numerous investigations have been developed that have studied the relationship between pedagogical leadership and an improvement in the student’s performance and results.

Pedagogical or educational leadership will relate its exercise to the academic achievements of students and the results of educational institutions. In this sense, this leadership will influence or move the different educational agents to articulate and achieve the shared objectives and goals of the educational institutions.

We can highlight different studies that have pointed to pedagogical leadership as one of the most important factors that causes a positive impact on student learning (Jaime-Cuadros et al., Citation2016). Not only that, but in the same way it will increase the success of educational centers (Lorenzo- Delgado, Citation1994). Leithwood et al. (Citation2006) in their study propose a review of both the theoretical proposals and the evidence found on the nature, causes, and consequences for students and educational centers of effective pedagogical leadership. V. Robinson et al. (Citation2009) found how when educational leaders engage in teacher professional learning, a great impact on student outcomes is greater than any other leadership activity. Day et al. (Citation2008), as well as Day et al. (Citation2009), also affirm that there is an empirical and significant relationship between the values and qualities of educational leaders as well as the strategic improvement actions they put in place, with the improvement in school conditions that lead to improvements in student outcomes. And V. M. J. Robinson (Citation2007), starts from the premise that politicians have the perception that principals can make a difference in the progress of the students of their centers with their decision-making.

Akhtar et al. (Citation2019), highlight the importance of leadership in stimulating both faculty and students, as well as in creating a collaborative environment. Alward and Phelps (Citation2019), have established a direct relationship between leadership and student outcomes as well as quality of education; Banker and Bhal (Citation2020) and Fernández González et al. (Citation2020), have also established a direct relationship between leadership and educational quality; Hong et al. (Citation2021), highlight the relationship between leadership and educational quality and results, while Latif and Marimon (Citation2019), have established a direct relationship between leadership and goal achievement. Meghji et al. (Citation2020), in their research, emphasize the inclusion of leadership and knowledge practices and relate them with institutional management and institutional performance, and Orozco et al. (Citation2020), state the importance of internal management to reach the educational quality and the achievement of higher standards commensurate with the needs of learners.

Indeed, pedagogical leadership will focus the leader’s activity on both organizational and professional aspects that have an impact on the teaching staff and the organization, so that this has an impact on student learning. In this way, we can affirm how educational leadership will focus on the quality of teaching and student outcomes.

For decades, research in education has focused on finding ways to improve the effectiveness of the school’s administrative team, valuing the evaluation of administrators as an important tool that could shed light on to finding these improvements. However, the design of these assessment tools has always been a challenge due to the different perspectives on the behaviours associated with leadership, as well as the fact that the different evaluation tools vary greatly in terms of content and methodology.

When assessing pedagogical leadership, taking into account that it focuses on student learning, it is necessary to establish the variables that will facilitate the influence of leaders’ actions on the improvement of student results.

Obviously, it is necessary to take into account, in the first place, those dimensions that make classroom improvement possible by supporting and stimulating the work of teachers in the classroom, without forgetting other dimensions such as leadership practices and professional development.

As we found in Polikoff et al. (Citation2009), to respond to this need, a team of researchers from Vanderbilt University and the University of Pennsylvania in 2005 designed the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED), a theoretically grounded, reliable and valid evaluation model of the director’s educational leadership. In the first phase they studied the literature on the effective leadership of directors to build a conceptual framework based on it, so that they could design the tool. Then, they conducted a series of small-scale psychometric studies to test the validity and reliability of the instrument as well as to improve it (Porter et al., Citation2010a). Finally, a nationwide study was conducted in the United States in elementary schools, middle schools and high schools (Educational centers with levels equivalent to Primary, Secondary and Baccalaureate in Spain) achieving important support to the conceptual framework (Porter et al., Citation2011). Subsequently, there have been numerous studies in which the tool has also been validated.

Different research has reviewed the different instruments for assessing the work of school leaders, with the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED) standing out as an instrument that has the potential not only to measure educational leadership, but also to detect areas for improvement and measure the effectiveness of the measures implemented.

2. The Vanderbilt Education Leadership Assessment (VAL-ED)

The Vanderbilt Education Leadership Assessment (VAL-ED) is a multiple assessment tool, with a rating scale based on a series of evidences, which evaluates the behaviours of managers that are known to directly influence the performance of the teaching team and, through them, the learning of Vanderbilt University students (Citation2011a, 2011b).

Since leadership focused on effective learning is at the intersection of two dimensions: the main components created through key processes, the VAL-ED has been designed to evaluate both the main components and the key processes. The core components refer to the characteristics of educational institutions that support student learning and improve the ability of the teaching team to teach their students. On the other hand, key processes refer to how leaders create and manage those core components.

2.1. Core components

As we have already highlighted, and as we find in Porter et al. (Citation2008), the VAL-ED framework includes six main components that represent the constructs of Learning-Centered Leadership:

High standards for student learning. These are defined as the degree to which leadership ensures that individuals, teams, and academic goals are aligned to achieve both academically and socially rigorous learning. In the proposed framework, not only the existence of goals for student learning is evaluated, but the quality of academic objectives is specifically emphasized, the extent to which there are high standards and rigorous learning objectives.

Rigorous Curriculum is understood as the content of the instruction, along with the need to be ambitious. In this regard, educational leaders will play a crucial role in setting standards for high student performance in their institutions, which will involve ambitious academic content represented in the curriculum students follow.

Quality Instructions. As Porter et al. (Citation2011) point out, a rigorous curriculum by itself is insufficient to ensure optimal student learning. Quality Instruction is also required, i.e. effective instructional practice that maximizes students’ academic performance and social learning. Effective education leaders must find ways to ensure that all students can receive that quality teaching by providing support and feedback to the cloister, so that it can improve its instruction.

Culture of learning and professional behaviour. Another major component of the assessment framework is leadership that ensures that the institution is organized, rather than from a bureaucratic point of view, as a learning community, in which student development from both an academic and social point of view is at the center.

Connections to external community. Leading an institution with high expectations and academic achievement on the part of all students equally requires strong connections with the community.

Performance accountability. There is an individual and collective responsibility among the leader, faculty, students, and community to achieve rigorous academic and social learning goals. Learning-focused leaders integrate internal and external accountability systems by holding their team accountable for implementing strategies that align teaching and learning with performance, set goals and objectives.

2.2. Key processes

Similarly, the conceptual framework presents six key processes which, although interconnected, and are recursive and reactive among them, for the purposes of descriptive evaluation and analysis, are each reviewed individually.

Planning, understood as the articulation of a shared direction, as well as the implementation of coherent policies, practices and procedures, which helps to focus resources, tasks and people.

Implementing, which consists of putting into practice the necessary activities to achieve high standards of performance by students.

Supporting. Leaders must create enabling conditions; ensure and use the financial, political, technological and human resources necessary to promote academic and social learning. Support is a key process that ensures the resources needed to ensure that the main components are available and well used.

Advocating, understood as addressing the diverse needs of students, ensuring that policies in the educational institution do not pose or create barriers for certain students, as well as that students with special educational needs receive content-rich instruction.

Communicating, which consists of the development, use and maintenance of information exchange systems between members of educational institutions and with their external communities. This communication should inform, promote and link institutions being key in supporting the academic and social learning of students.

Monitoring, which involves the collection and analysis of data in a systematic way to make judgments that guide decisions and actions for continuous improvement.

It is important to note that the VAL-ED has been designed to evaluate critical leadership behaviours in order to perform diagnostic analysis, performance feedback, progress tracking, professional development planning, and summative evaluation. In this sense, the results of the evaluation include interpretable behavioural profiles, both from the reference of the norms, and from the perspective of the standards, and different accumulations of behaviours suggested for improvement (Vanderbilt University, Citation2011b).

On the other hand, as these authors point out, according to empirical research (Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996), this evaluation model does not foresee the direct effects of leadership behaviors on student success, but those leadership behaviours that will lead to changes in school performance, which in turn will lead to student success. This leadership model also postulates that there are aspects of the context within which leadership takes place that influence the evaluation of leadership (Murphy & Meyers, Citation2008).

Finally, the fact that it is a 360-degree evaluation tool implies that the different key people who surround the manager (that is, the faculty, the manager himself and the supervisors of the latter) will be the ones who answer the questionnaire to be able to evaluate the leadership.

2.3. Validity of the VAL-ED

Apart from the studies mentioned above to test the validity and reliability of this instrument, subsequently, there have been others in which the validity and reliability of the VAL-ED have been tested.

Porter et al. (Citation2010b), studied the validity and reliability of VAL-ED through a nationwide study in the United States. In their work they used data from more than 270 schools in different settings, and the results show that the instrument is valid to measure leadership focused on the learning of principals. In addition, it also follows that the VAL-ED made it possible to distinguish different performance subscales. Together with findings from the development phase of VAL-ED, these results support the conclusion that K-12 schools can use VAL-ED to assess learning-focused leadership.

Polikoff et al. (Citation2009), evaluated the differential operation of VAL-ED elements. Based on data obtained at the national level (United States), they sought evidence of the differential functioning of its different elements at the school, local and regional levels. They found evidence to conclude that the items on The Vanderbilt Education Leadership Assessment are not biased based on these school characteristics, reinforcing their use in schools across the country.

Minor et al. (Citation2014), also wanted to check the validity of VAL-ED in primary and secondary schools in the United States. To do this, they carried out a study in which they analyzed the accuracy with which the VAL-ED scores can identify the belonging to the two groups previously selected by the superintendents, (directors whose performance of their functions were in the top 20% and the bottom 20%). Using a discriminant analysis, the VAL-ED placed principals in the established groups, with a 70% correlation, for both primary and secondary schools. The accuracy was higher for the upper group than for the lower group.

Goldring et al. (Citation2015), investigated the psychometric characteristics of the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education, analysing its convergent and divergent validity. The authors hypothesized that VAL-ED is highly correlated with other measures of instructional leadership, but will be weakly correlated with more general measures of leadership that have their roots in personality theories. The sample of centers in this study included 63 educational centers: 47 elementary schools, 7 middle schools and 9 high schools, of eight districts in six states in the United States. As for the results, the three sets of correlations of teachers’ responses about their principals between the three measures of VAL-ED, TEIQue and PIMRS are similar in size and all quite high. However, the picture is different for directors’ self-assessments. VAL-ED is more strongly correlated with PIMRS than with TEIQue, providing some evidence of convergent validity between learning-focused leadership and educational management, and divergent validity when compared to traits of emotional intelligence.

Likewise, in their study, Goff et al. (Citation2015) highlight how numerous researchers have conducted several studies to validate VAL-ED, proving to be a reliable instrument that can be used in multiple contexts.

Subsequently, Minor et al. (Citation2017) evaluated the test-retest validity of the VAL-ED for a sample of seven school districts as part of a series of multiple validity and reliability assessments based on several samples from real VAL-ED users. They administered VAL-ED at two different times and examined correlations and mean differences between the first and second moments. They found that the principal and teacher grades of moment 1 and moment 2 have large, positive, and meaningful correlations.

With these results, we can conclude that the Vanderbilt Evaluation of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED) instrument is, therefore, a reliable and valid instrument to measure the effectiveness of the educational leadership of principals.

On the other hand, since the creation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), the development of new teaching models in which the student is responsible for his or her own learning, has been favoured. In this educational context, pedagogical leadership is presented as a response capable of promoting and improving both the quality of Higher Education and the teaching-learning processes (Palomino-Fernández et al., Citation2021, p. 67).

However, the results of the systematic analysis of the literature studied on the relationship between pedagogical leadership, student outcomes, and quality of Higher Education, shows that, despite the demonstrated importance of the influence of leadership on the performance of students in these institutions (Yokuş, Citation2022), their integration is not yet sufficiently widespread.

It is convenient to start from the premise that “Higher Education Institutions are complex organizations in which their management is a challenge for leaders” (Smith, Citation2020, p. 39). In fact, universities are expected to not only create knowledge, improve equity and respond to the needs of students, but to do so more efficiently and effectively.

Indeed, Alward and Phelps (Citation2019) point to the existence of increased pressure when it comes to attributing not only to faculty, but also to administrators, responsibility for student learning outcomes. Meghji et al. (Citation2020) underline the importance of the challenge of building efficient practices for knowledge management and quality, establishing a direct relationship between them and leadership.

In this same line, Hong et al. (Citation2021) also manifest themselves, stating that “the sum of the purpose of educational institutions and leadership actions are those that generate the achievement of effective results collaborating in the creation of a social reputation” (p. 1004). We must also bear in mind that in order to raise the educational quality in a higher education institution, an external evaluation and the consequent classification are not enough, by themselves, to raise the educational quality, but it is necessary to start from the leadership of the management positions and have the commitment and participation of the rest of the staff (Orozco et al., Citation2020).

Similarly, it highlights how the perception of a team’s transformational leadership has a positive effect on both communication and team trust. In addition, communication has a positive effect on trust and this, a significant effect on the creativity of the team, which translates into an improvement in performance (Akhtar et al., Citation2019).

This review also allowed us to observe a tendency to report and publish mainly novel interventions, especially with the intention of discovering the leadership models that are most effective in improving the quality and results of Higher Education Institutions. We found how Kantabutra (Citation2010), based on a critical review of existing theoretical concepts and empirical evidence, developed a new research model for future research. For their part, Vu et al. (Citation2020) set out to determine the appropriate leadership style in higher education institutions and the role of the leader in promoting academic research in Vietnamese universities, highlighting how transformational leadership is actually effective when autonomy is facilitated in organizations as well as in the budget.

That is why leadership is presented “as a fundamental element for institutional success in achieving this transformation as well as a critical factor for the improvement of Universities” (Delener, Citation2013, pp. 19–20).

However, as already pointed out above, the small number of works in this line suggests that the research is still insufficient, so there is a clear need to further enhance this area of research, where it reverses the effectiveness of an organizational development and its improvement in all dimensions of the institution. Consequently, it is necessary to continue working in compliance with the necessary scientific standards that guarantee the quality of knowledge, in order to be able to know, if the effects of pedagogical leadership that have been observed in the performance and performance of students in compulsory education centers, are equally evident in the context of Higher Education, as well as its influence on improving the quality of them.

At this point, the general objective of this paper is to translate, adapt and validate the VAL-ED questionnaire to the Spanish university context, so that an evaluation tool can be available that allows us to continue deepening pedagogical leadership in the context of Higher Education.

3. Translation and adaptation of VAL-ED to the context of higher education

3.1. Literature review

A bibliographic review of the different documents published on the VAL-Ed has been carried out in response to the need to:

Know the bank of questions from which the questionnaires are nourished.

Select criteria for the questions included in the questionnaires.

Interpret the results once the questionnaires are answered.

Prepare the final report once the different responses provided by each of the “agents” participating in it have been analysed.

3.2. Translation of the questionnaire

The first step consisted of the translation from English into Spanish of the different questions that we found in the question bank (FRAMEWORK) at Vanderbilt University (Citation2011a) used for the elaboration of the questionnaires.

After the translation of these, a team of experts formed by: a graduate in translation and interpretation, and a graduate in English Philology and a graduate in Hispanic Philology. They participated in the revision of the translation carried out to ensure, on the one hand, that the translation carried out was as faithful as possible and did not deviate from the original questions as well as that the translation of them was understandable and coherent in Spanish.

3.3. Adaptation of the questionnaire to the university context

Since the Val-Ed was originally designed to assess the leadership of school principals (Porter et al., Citation2008), the next step was to adapt the questionnaire to the university context. To this end, all those questions that made exclusive reference to areas of Compulsory Education were eliminated, and could not be contextualized in Higher Education.

This version of the questionnaire was reviewed through a content validation by several experts in management and leadership of the Faculty of Education of the International University of La Rioja and the University of Granada.

A questionnaire was sent in which it was explained that the purpose of the questionnaire was to validate the adaptation of the VAL-ED questionnaire to the university context to evaluate the pedagogical leadership.

In this questionnaire, the different experts were asked to validate the relevance of the different questions of the “question bank” in relation to the aspects of leadership that were intended to be evaluated by marking “yes” or “no.” In the event of a negative assessment, they were asked to justify their reply. The questionnaire also included the questions that were eliminated from it as they were considered inappropriate in a higher education context. They were also asked to consider whether the removals made were relevant by answering “yes” or “no,” and in case of a negative answer, they were asked to justify why.

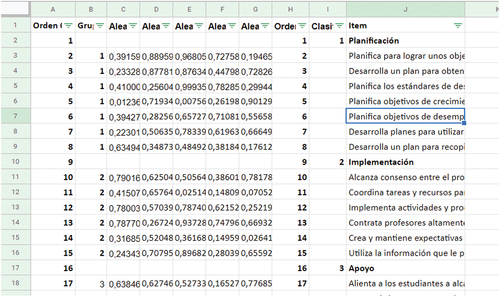

Based on the suggestions and points they provided, the final version of the question bank of the questionnaire was elaborated (Table ):

Table 1. Conceptual model including the main components and key processes

3.4. Generation of questionnaires from the question bank

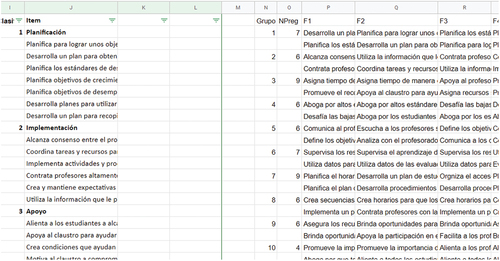

To assess principal behaviours at the intersection of core components and key processes, the VAL-ED develops a multi-respondent rating scale (supervisors of degree directors, degree directors, and professors teaching in the degree), which requires respondents to make judgments about a manager’s leadership behaviours that influence teacher performance and teacher learning students. Thus, as found at Vanderbilt University (Citation2011b), and the six-by-six, 36-cell conceptual leadership model will provide the framework for selecting elements that describe the behaviours of the leaders represented by the cell. Each group of elements in each cell serves as an indicator of the leadership construct (see figure ).

Figure 1. Outline of the translation process, adaptation and design of the questionnaires.

As stated by Porter et al. (Citation2008), the VAL-ED 360 evaluation (see table ) will consist of 72 elements in each of questionnaires 1, 2 and 3. Items were randomly assigned to a form within each of the 36 cells. For each group of respondents (manager, supervisor, faculty), The questionnaires were generated by randomly including, in each of them, the questions from the question bank. For each of the 72 items, the respondent rates the effectiveness of the director’s behaviour. The effectiveness scale has five options, (1) ineffective, (2) minimally effective, (3) satisfactorily effective, (4) highly effective, and (5) Outstandingly effective.

Table 2. VAL-ED 360 evaluation

On the other hand, when rating the effectiveness of each pair of items in each of the cells that make up the 72 main behavioural items, the respondent must verify the sources of evidence on which the effectiveness rating will be based. There are five options for sources of evidence: official documentation, internal documentation, other documentation, personal observation, or no source of evidence.

To create the different questionnaire models, the following were used:

A spreadsheet to generate the question pairs for each form.

A Google Scripts to create the forms.

3.4.1. Random order generation

In column J of the spreadsheet (see Figure ) all the questions were arranged grouped by blocks. In columns C through G, random numbers were generated using a formula. The spreadsheet was refreshed a non-fixed number of times with each insertion of new formulas and several refreshments.

3.4.2. Selection of questions

In columns P to T (see Figure ) formulas were written to randomly retrieve two questions from each group. As an example, in cell P2, to obtain the two questions of group 1, the formula was used =query(A$3:J;“select J where B=”&N2&“order by C desc limit 2”)

In this way, we retrieve the statements of the two highest random numbers, which on the one hand ensures that the questions are chosen randomly and on the other hand avoids a possible repetition of the same statement in a couple of questions.

3.4.3. Construction of form models

For the creation of the different form models with the random question pairs for each model and group, an automation was created with Google Apps Script. This automation reads the question pairs of each model and creates the different forms from scratch. The script code is shown below.

function CrearFormulario1_36(){

var FormanityNumber = 1//Form number

varFormName=“Form”+NumberForm

var Titleform=“e-leadership VAL-ED”+NumberForm

var Description =“Select the answer that best defines the performance of the director/coordinator of the degree for each of the questions”

var StatementQuestion=“”

const form=FormApp.create(FormName)

form.setTitle(Titleform)

form.setDescription(Description)

Create initial questions

var item=form.addTextItem();

item.setTitle(“University”)

item.setRequired(true)

item=form.addTextItem();

item.setTitle(“Faculty”)

item.setRequired(true)

item=form.addTextItem();

item.setTitle(“Degree/Studies”)

item.setRequired(true)

Create36Questions

var form = form

var ss = SpreadsheetApp.openById(“Google Sheet Id”);

var PtjName = ss.getSheetByName(“Generated”);

for (var i = 1;i ≤ 36;i++)

{

var item = form.addGridItem();

var RowValues = PtjName.getRange(2*i, 15+FormandialNumber,2).getValues();

var ValuesRow = [];

ValuesRow[0] = RowValues[0]

ValuesRow[1] = RowValues[1]

item.setTitle(StatementQuestion)

item.setRows(ValuesRow)

item.setRequired(true)

item.setColumns([“Non-cash”, “Minimally effective”, “Reasonably effective”, “Cash”, “Very effective”]);

}

}

The questions for each of the questionnaires would have the following structure (Table ):

Table 3. VAL-ED 360 structure with numbered questions

In this way, 3 questionnaires were obtained:

A first questionnaire for the supervisors of the degree directors (Area Directors, Dean, Vice-Dean…)

A second questionnaire for degree directors.

A third questionnaire for teachers who teach in the degree.

3.4.4. Psychometric characteristics of the questionnaires

As noted above, after the translation of the questionnaire, a questionnaire was sent to a group of experts with a degree in English philology and in translation and interpretation, who analysed the translation of the questions that made up the question bank from which the questionnaires would be formed. To do this, they were asked to be content with “yes” or “no,” if they considered that each of the translations was correct, as well as that they were easy to understand, not giving rise to confusion or equivocation when interpreting them. They were also offered the possibility of justifying their reply, in the event that the translation did not seem appropriate to them.

At the time of validating the content of the questions that were included in the question bank from which the questionnaires would be carried out, a pilot of the instruments has been carried out where six experts in leadership and Higher Education from the universities of Granada and the International University of La Rioja have participated, in which the questions of the questionnaires were related to the characteristics of the Spanish university context. There was an agreement between the group of experts who analysed the definitive questions of the question bank from which the matrix of intersection between the Main Components and the Key Processes is nourished, affirming that these represent the dimensions of educational leadership that are to be analysed.

A questionnaire was sent in which it was explained that the purpose of the questionnaire was to validate the adaptation of the VAL-ED questionnaire to the university context to evaluate the pedagogical leadership of the directors/coordinators of the degree. It was also highlighted that the validated VAL-ED questionnaire has been taken as a base, proceeding in the first place to its translation into Spanish and the elimination of certain items for its adaptation to the environment and the group to which it is addressed in a second step.

In this questionnaire, the different experts were asked to validate the relevance of the different questions in relation to the aspects of leadership that were intended to be evaluated by marking “yes” or “no.” In the event of a negative assessment, they were asked to justify their reply. The questionnaire also included the questions that were eliminated from it as they were considered inappropriate in a higher education context. They were also asked to consider whether the removals made were relevant by answering “yes” or “no,” and in case of a negative answer, they were asked to justify why.

In order to verify the reliability of the questionnaires, the Cronbach’s alpha value was calculated for each of them, obtaining the following values: 0.896 for the Supervisors questionnaire. 0.948 for the Directors/Coordinators questionnaire, and 0.938 for the teachers’ questionnaire. Since all the values obtained are very close to 1, we can conclude that the three questionnaires obtained are reliable.

4. Conclusions

The main objective of this study was the translation and subsequent adaptation to the Higher Education context of the Educational Leadership Assessment tool Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED). We can affirm that the questionnaire includes different items that collect the main components of educational leadership. The translation and adaptation to the context of Spanish Higher Education of the questionnaire for Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED) is a valid and reliable instrument to evaluate the leadership of directors/coordinators of degrees in Higher Education.

We can affirm that the questionnaire generated is a valid questionnaire that will allow us to evaluate the pedagogical leadership of directors in the context of Higher Education, allowing us not only to assess the extent to which leadership in universities is focused on student performance and achievement, but also on possible areas of improvement that will undoubtedly improve not only the results of students, but also the results of Higher Education educational institutions.

Among the limitations of the study, it is worth noting the lack of representativeness of the sample. Given that the recruitment of participants was conditioned voluntarily at the time of participating in the study, it has not been possible to guarantee the representativeness of the entire Higher Education as a whole. It should also be noted that the sample size of respondents was not significant enough to statistically validate the questionnaires.

As already pointed out above, the small number of works that analyse the influence of educational leadership in Higher Education on the performance of students and the quality of institutions, suggests that the research is still insufficient, being manifested the need to further enhance this area of research, where it reverses the effectiveness of organizational development and its improvement in all dimensions of the institution. The translation and adaptation of the VAL-ED to the context of Higher Education is, therefore, a useful tool to analyse the leadership of managers in Higher Education, as well as when it comes to helping to focus on where to direct future areas of improvement in leadership in Higher Education. Consequently, being able to count on this tool will allow us to continue working in compliance with the necessary scientific standards that guarantee the quality of knowledge, in order to be able to know, if the effects of pedagogical leadership that have been observed in the performance and performance of students in compulsory education centers, are also evident in the context of Higher Education, as well as its influence on improving the quality of them.

This study comes from a broader research, derived from a doctoral thesis work in execution entitled: “Analysis of pedagogical e-Leadership in Distance University Education. Implications for educational improvement”.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: FLL,JMPF, MPCR and IAD; Data curation:JMPF and MPCR; Formal analysis:JMPFand IAD; Funding acquisition: MPCR and MPCR; Investigation:FLL,JMPF,MPCR and IAD; Methodology:MPCR and IAD; Project administration: FLL and MPCR; Resources: MPCR and IAD; Software: JMPF and IAD; Supervision:FLL and MPCR; Visualization: JMPF, MPCR and IAD ; Writing - original draft: FLL,JMPF, MPCR and IAD; Writing - review & editing: FLL,JMPF, MPCR and IAD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

José Manuel Palomino Fernández

José Manuel Palomino Fernández PhD student at the University of Granada. Faculty of Education. Line of research: Curriculum, organisation and training for equity in the knowledge society.Thesis: Analysis of pedagogical e-leadership in Distance University Education. Implications for educational improvement.https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9753-1470

María del Pilar Cáceres Reche

María del Pilar Cáceres Reche Professor in the Department of Didactics and School Organisation at the University of Granada (Spain) and director of the Research Group “Leadership, Development and Educational Research” (LEADER Group, SEJ-604). Her research interests focus on teaching innovation and ICT, leadership and organisational development. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6323-8054

Inmaculada Aznar Díaz

Inmaculada Aznar Díaz Professor in the Department of Didactics and School Organisation at the University of Granada. She works in the field of school organisation, digital competence in education, training for employment and active methodologies for learning with ICT. Director of the Research, Innovation & Technology in Education (RITE) research group (SEJ-607).http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0018-1150

Fernando Lara Lara

Fernando Lara Lara Professor in the Department of Didactics and School Organisation at the University of Granada (Spain) and research group member “Analysis of the Reality of Education” (HUM672). http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1545-9132

References

- Akhtar, S., Khan, K., Hassan, S., Irfan, M., & Atlas, F. (2019). Antecedents of task performance: An examination of transformation leadership, team communication, team creativity, and team trust. Journal of Public Affairs, 19(2), e1927. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1927

- Alward, E., & Phelps, Y. (2019). Impactful leadership traits of Virtual Leaders in Higher Education. Online Learning, 23(3). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i3.2113

- Anderson, S. (2010). Liderazgo Directivo: Claves para una mejor escuela. Psicoperspectivas Individuo y Sociedad, 9(2), 34–17. https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol9-Issue2-fulltext-127

- Banker, D. V., & Bhal, K. T. (2020, 05, 01). Creating world class universities: Roles and responsibilities for academic leaders in India. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 48(3), 570–590. ISSN 1741-1432, ISSN 1741-1440. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143218822776

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Hopkins, D., Harris, A., Leithwood, K., Gu, Q., Brown, E., Ahtaridou, E., & Kington, A. (2009). The impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes. Department for children, school and families, DCSF final report. Department for Children, Schools and Families, DCSF, University of Nottingham & The National College for School Leadership. www.e-liderar.org/documents/RS/pdfs/The-impact-of-school-leadershipFinal.pdf

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Hopkins, D., Leithwood, K., & Kington, A. (2008). Research into the impact of school leadership on pupil outcomes: Policy and research contexts. School Leadership & Management, 28(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430701800045

- Delener, N. (2013). Leadership excellence in Higher Education: Present and future. Journal of Contempraroy Issues in Bussiness and Government, 19(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.7790/CIBG.V19I1.6

- Fernández González, M. J., Pīgozne, T., Surikova, S., & Vasečko, Ļ. (2020). Students’ and staff perceptions of vocational education institution heads’ virtues. Quality Assurance in Education, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-11-2018-0124

- Goff, P., Salisbury, J., & Blitz, M. (2015). Comparing CALL and VAL-ED: An illustrative application of a decision matrix for selecting among leadership feedback instruments (WCER Working Paper No. 2015-5). Wisconsin Center for Education Research.

- Goldring, E., Cravens, X., Porter, A., Murphy, J., & Elliott, S. (2015). The convergent and divergent validity of the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED): Instructional leadership and emotional intelligence. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(2), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-06-2013-0067

- Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1996). Reassessing the principal’s role in school effectiveness: A review of empirical research, 1980-1995. Educational Administration Quarterly, EAQ, 32(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X96032001002

- Hong, P. C., Chennattuserry, J. C., Deng, X., & Hopkins, M. M. (2021). Purpose-driven leadership and organizational success: A case of higher educational institutions. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(7), 1004–1017. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-02-2021-0054

- Jaime-Cuadros, M. P., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., & Hinojo- Lucena, F. J. (2016). Analysis of leadership styles developed by teachers and administrators in technical-technological programs: The case of the cooperative University of Colombia. International Journal of Leadership in Education Theory and Practice, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2016.1172734

- Kantabutra, S. (2010). Vision effects: A critical gap in educational leadership research. International Journal of Educational Management, 24(5), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541080000451

- Latif, K. F., & Marimon, F. (2019). Development and validation of servant leadership scale in Spanish higher education. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40(4), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-01-2019-0041

- Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2006). Successful school leadership: What it is and how it influences pupil learning (Research Report 800). DfES.

- Lorenzo- Delgado, M. (1994). El liderazgo educativo en los centros docentes. La Muralla.

- Meghji, A., Mahoto, N., Unar, M., & Shaikh, A. (2020). The role of knowledge management and data mining in improving educational practices and the learning infrastructure. Mehran University Research Journal of Engineering & Technology, 39(2), 310–323. https://doi.org/10.22581/muet1982.2002.08

- Minor, E. C., Porter, A. C., Murphy, J., Goldring, E. B., Cravens, X., Stephen, N., & Elloitt, S. N. (2014). A known group analysis validity study of the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education in US elementary and secondary schools. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 26(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9180-z

- Minor, E. C., Porter, A. C., Murphy, J., Goldring, E. B., & Elloitt, S. N. (2017). A test-retest analysis of the Vanderbilt Assessment for Leadership in Education in the USA. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 29(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-016-9254-9

- Murphy, J., & Meyers, C. (2008). Turning around failing schools: Leadership lessons from the organizational sciences. Corwin Press, National Staff Devlopment Council and American Association of School Administrators.

- Orozco, I., Edgar, E., Jaya, E., Aida, I., Ramos, A., Fridel, J., Guerra, B., & Rosa, M. (2020). Retos a la gestión de la calidad en las instituciones de educación superior en Ecuador. Educación Médica Superior, 34(2), 1–14.

- Palomino-Fernández, J. M., Cáceres- Reche, M. P., & Ramos, M. (2021). E-Liderazgo y enseñanza a distancia en Educación Superior. Principales claves. In J. A. Marín-Marín, J. C. Cruz-Campos, S. Pozo-Sánchez, & G. Gómez-García (Eds.), Investigación e innovación educativa frente a los retos para el desarrollo sostenible (pp. 67–77). Dykinson.

- Porter, A. C., Murphy, J., Goldring, E., Elliot, S. N., Polikoff, M. S., & May, H. (2011). Vanderbilt assesement of leadership in education:Technical manual. Discovery Education Assessment.

- Porter, A. C., Murphy, J., Goldring, E. B., Elliott, S. N., Polikoff, M. S., & May, H. (2008). Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED) [Database record]. APA PsycTests.

- Porter, A. C., Polikoff, M. S., Goldring, E., Murphy, J., Elliot, S. N., & May, H. (2010a). Developing a psychometrically sound assessment of school leadership: The VAL-ED as a case study. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(2), 135–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510361747

- Porter, A. C., Polikoff, M. S., Goldring, E., Murphy, J., Elliot, S. N., & May, H. (2010b). Investigating the validity and reliability of the Vanderbilt assessment of leadership in education. The Elementary School Journal, 111(2), 282–313. https://doi.org/10.1086/656301

- Robinson, V. M. J. (2007). School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why. Australian Council for Educational Leaders.

- Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., & Lloyd, C. (2009). School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why: Best evidence synthesis iteration (BES). Ministry of Education.

- Smith, M. L. (2020). Transformational leadership in Higher Education in Panama. Latitude, 2(13), 38–75. https://doi.org/10.55946/LATITUDE.V2I13.96

- Vanderbilt University. (2011a) . VAL-ED framework. Vanderbilt assessment of Leadership in Education. Discovery Education Assessment.

- Vanderbilt University. (2011b) . VAL-ED handbook. Vanderbilt assessment of Leadership in Education. Discovery Education Assessment.

- Vu, T., Vu, M., & Ngoc, H. (2020). The impact of transformational leadership on promoting academic research in higher educational system in Vietnam. Management Science Letters, 10(3), 585–592. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.9.022

- Yokuş, G. (2022). Developing a guiding model of educational leadership in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A grounded theory study. Participatory Educational Research (PER), 9(1), 362–387. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.22.20.9.1