Abstract

In most developing nations, Zimbabwe in particular, the value of diaspora-based tourist marketing (DBTM) in igniting socio-economic aspects toward a destination remains underutilized. The theoretical framework for diaspora-based tourist marketing (DBTM), which serves as the foundation upon which DBTM study is formed, is highlighted in this paper. In this paper, a theoretical framework consisting of four theoretical perspectives, namely General Systems Theory (GST), Social Exchange Theory (SET), Stakeholder Theory (ST), and Expectancy Theory (VIE), has been adopted in order to develop a DBTM framework that harnesses the diaspora to improve tourism traffic. Using content analysis, the theoretical analysis paper explores related theories that enrich the appreciation of DBTM’s potential and in the process identify an overarching theory or theories in relation to DBTM. Theoretical framework contributions will aid in guiding the study that will shed light on the advantages of using the diaspora as destination marketers and the improvement of tourism traffic to Zimbabwe. The theoretical framework results will also be incorporated into the development of a DBTM framework that will harness the diaspora to improve tourism traffic to Zimbabwe.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The use of the diaspora as tourism marketers to improve tourism traffic factors has remained an understudied phenomenon. Strategies for harnessing the diaspora as tourism marketers to enhance the flow of socio-economic factors to tourism destinations have not been fully explored. Zimbabwe also suffers the same fate where there is a paucity of mechanisms and lack of a framework on how to optimize the use of the diaspora to improve tourism traffic factors to tourism destinations. Practical contribution of the study will come from the diaspora-based tourism marketing framework which is going to be developed to improve tourism traffic factors to Zimbabwe.

1. Background

The majority of developing nations have not yet realized the benefits of using the diaspora to sell to tourists and boost the socioeconomic benefits of a tourism destination (Zengeya et al., Citation2023). Tourist destinations in developing countries are always competing with other well-known and renowned locations throughout the world, and they are frequently pushed to adopt new tourism marketing strategies to stay competitive (Mensah, Citation2022). There is a significant shift in tourist marketing techniques that include diaspora engagement in various ways that contribute to the tourism economy (Eplerwood et al., Citation2019). As a result, this growing need as lead to the exploration of new strategies that will engage the diaspora as home of origin tourism marketers to improve tourism traffic factors to the tourism destination country of origin (Zengeya et al., Citation2023). This theoretical framework is the blueprint for diaspora-based tourism marketing (DBTM) which acts as an underpinning upon which DBTM study is built (Çepni, Citation2021). The significance of diaspora-based tourism marketing (DBTM) in galvanizing socio-economic factors to a destination remains untapped in most developing countries, Zimbabwe being a case in particular (Zengeya et al., Citation2023). A theoretical framework consequently involves the application of related theories to bring to light on the phenomenon under study and in social research, however there is no one theory that adequately answers the research questions (Hughes et al., Citation2019). In this study, to come up with a diaspora-based tourism marketing framework that harnesses the diaspora to improve tourism traffic, a theoretical framework which comprises four theoretical perspectives which are General Systems Theory (GST), Social Exchange Theory (SET), Stakeholder Theory (ST) and Expectancy Theory (VIE) has been adopted. The use of multiple related theories enriches the researcher’s appreciation of the phenomenon under study and assists to increase the validity of the outcomes (Çepni, Citation2021). These theories possess characteristics that can help picture diaspora-based tourism marketing and the improvement of tourist traffic. However, many of these theories lack scope and the necessary accuracy to do so (Sandberg & Alvesson, Citation2021). The theories suffer from one or so paucities in their formidable forecasts to strengthen the link diaspora-based tourism marketing and an improvement in tourism traffic. Thus, this paper presents theories that have the potential to explain the connection between diaspora-based tourism marketing and an improvement in tourism traffic and in the process identify an overarching theory or theories. The theory proponent, basic tenets of the theory and the relevance to the paper are briefly explained in Table .

Table 1. The main theories underpinning Diaspora-Based Tourism Marketing (DBTM)

2. DTBM Theoretical framework

The four theoretical viewpoints that make up the theoretical framework are conceptualized below: Expectancy Theory, Social Exchange Theory, Stakeholder Theory, and General Systems Theory (VIE). This identifies an overarching theory or theories in the process of presenting hypotheses that have the potential to explain the relationship between diaspora-based tourist marketing and an improvement in tourism traffic.

2.1. General System Theory (GST)

The main theory that anchors DBTM is the GST, which gives a basis for the Leiper's tourism systems model and the Mills and Morris tourism marketing systems model from where the conceptual framework of DBTM will be derived. Although it is impossible to pinpoint a single author as the originator of general systems theory (GST), academic circles agree that biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901–1972) was one of the pioneers in this field. A “system” can be characterized as a complex of elements standing in interaction (Bertalanffy, Citation1968). Regardless of the nature of the component elements or the relationships or pressures between them, there are general principles that apply to systems. The general principal of GTS includes a collection of parts that interact to achieve a given end. GTS should be logically ordered and sufficiently coherent to describe, explain, or direct the functioning of a whole (Beni, Citation2001, p. 23). Although systems theory is holistic, the holistic approach is also important in tourism because it encompasses all of tourism’s key characteristics, such as people movement, transportation, lodging, and activities at the destination; the holistic approach encompasses all of tourism’s elements, regardless of whether tourism is considered a business sector or a research field (Leslie, Citation2000). All these aspects are all important in coming up with a viable diaspora-based tourism marketing (DBTM) framework (Zengeya et al., Citation2023). It is from GTS that Leiper developed the tourism systems model, this model is a basis in which some of the elements of diaspora-based tourism marketing framework are taken from.

Leiper (Citation1995, p. 22) argues that Bertalanffy concluded, that in order to learn more about living things, he needed to move beyond biology and combine knowledge from other sciences. Although the general systems theory which is the basis of the Leiper’s tourism system is a key part of the foundation literature in travel and tourism by providing a good representation of the way that the many parts of the tourism industry work together as a system, rather than individually. However, it fails to account for many of the marketing complexities of the industry and its ties with associated industries. Nonetheless, the general systems theory in terms of tourism system is an interesting theory in that is widely applicable both in an academic and practical sense (Postma & Yeoman, Citation2021). After examining Leiper’s model’s flaws, Mill and Morrison (Citation1985) offered a model of the tourism industry that was also based on general systems theory (GST). The notion incorporated a marketing component into the tourism system (Mill & Morrison, Citation1985). Marketing is the crucial link in the chain. The link between the GDS, Leiper's tourism model and Mills and Morris’s tourism marketing model in relation to DBTM is then analysed in detail in the methodology.

2.1.1. Proposed DTBTM conceptual framework

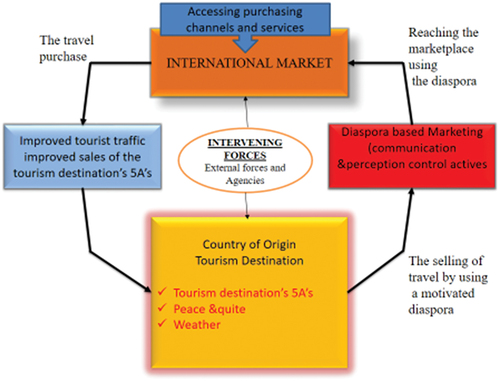

Figure is a presentation of the conceptual framework which will be used to guide the study. The content of the framework for harnessing the diaspora as tourism marketers to improve tourism traffic to Zimbabwe does not differ much from Leiper’s tourism systems model (Leiper, Citation1990), but adding the use of diaspora as tourism marketers to improve tourism traffic to the diaspora’s home destination. Limited knowledge, however, is about the actual concept for the use of the diaspora to improve tourism traffic which is seen as posing a market penetration threat to developing countries. Therefore, a conceptual framework projected in Figure attempts to enlighten the connection between the diaspora and tourist traffic and tourism marketing.

A conceptual framework is a running theory that will guide the study. If concepts are interwoven, they create a conceptual framework. Hence, the framework above will illustrate a multilateral relationship of concepts. In this study, the process begins with an identification of the destination area and the procedure a destination should follow to research, plan, regulate, develop, and service tourism activity. Leiper (Citation1990) solidifies that it is at the destination where the most noticeable and dramatic consequences of the system occur. Since, it is the destination where the utmost impact of tourism is felt, therefore the planning and management strategies should be implemented in this region. Most tourism activities take place at destinations. Not surprisingly then, destinations have emerged as the fundamental unit of analysis in tourism and this forms a pillar in any modelling of the tourism system. There is need of selling of travel to the intended market by harnessing a motivated diaspora since travellers are now spoilt for choice of destinations, which must compete for attention in markets cluttered with the messages of substitute products as well as rival places. Thus, when the concept of harnessing the diaspora is exploited, the procedures, practices and selling of travel become the means to which tourism marketing and tourist traffic improve is achieved.

The tourism destination area reaches the marketplace by making use of the diaspora to convince potential customers to purchase their tourism products and services. The diaspora acts as breeding tourism marketers for tourism, and practically turns as the push force to motivate and stimulate and encourage tourist travel. During tourism marketing, the diaspora as marketers tries to encourage the tourist to travel to the diaspora’s home of origin for tourism activities. Thus, encouraging the tourist to find information relating to reservations and travelling arrangements to the tourism destination region and finally purchasing the travel. This intern improves tourist traffic and sales of the (5 A’s) Accommodation, Activities, Amenities, Availability of transport and Ancillary services in the destination.

The international market is the actual tourist that purchases the travel. However, it is not an evident case that harnessing the diaspora as tourism marketers will lead to an improved tourist traffic to a destination because of the external and internal influences on travel including the alternatives to travel, the market inputs of tourism suppliers, and the process by which a buying decision is reached. Thus, the purchase of travel only becomes possible when the market through the help of the diaspora marketer acquires a positive mindset, related beliefs, positive perceptions, a desirable existence and relevant knowledge about the destination in question. However, the idea shown in the framework above is that if the diaspora is motivated with something they can be able to convince the international market to purchase a travel, the more they are motivated the more they encourage purchase of travel by tourists in order to improve tourist traffic. The repeated purchase of travel by tourist flanked by the diaspora results in an improvement in tourist traffic in Figure . The success is either supported or hindered by external factors and agencies. Therefore, the external environment in which destination operates in is key in bringing out its success. The conceptual framework above assumes that the diaspora plus tourism marketing process minus intervening forces equals an improved tourist traffic flow. Given the above background, the major question for this study will be: How can the use of diaspora be harnessed through DBTM to improve tourism traffic to Zimbabwe?

2.2. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

SET, in relation to tourism, is a tourism interaction-based theory built from sociology and social psychology. Emerson (Citation1962) designed it as a framework for studying tourism connections, interactions, and transactions. It is concerned with understanding the exchange of means between individuals or groups in an interaction setting. Individuals’ decisions to participate in an interaction process, according to the idea, are based on a cost–benefit analysis and an evaluation of alternatives. One of its foundational assumptions is that people engage in a logical way that maximizes their benefits while minimizing their costs (Ahn, Citation2022). The idea as noted by Ozel and Kozak (Citation2017) attempts to understand people’s social behaviour in terms of resource exchange, assuming that the diaspora will engage in social trade by marketing the home destination to gain an incentive in return from the Country of Origin (CoO). Thus, individuals like international tourists must interact with the diaspora and gain the information so that the CoO can obtain resources through the increase in tourist traffic (Zengeya et al., Citation2023). As a result, the trading process is driven by self-interest, individualism, and reliance, and the actors are assumed to have the same culture in terms of wanting to experience tourism (Adongo et al., Citation2019). Residents’ that is the diaspora opinions of tourist impacts are key components of tourism development.

The concept posits that social trade takes place in a social framework where those with more wealth, the international tourist has more power to travel and create wealth to the CoC. When all of the economic benefits of tourism are seen positive, a countries diaspora is more inclined to support it (Zhang et al., Citation2021a). That is if the diaspora believes the benefits of diaspora-based tourism marketing outweigh the expenses, they will support tourism development in their country of origin (CoO). This implies that stakeholder support is based on an assessment of the advantages and costs associated with the exchange process (Cao et al., Citation2022). This means that people’s opinions of the transaction can differ; for example, someone who experiences a positive outcome will judge the exchange differently than someone who perceives a negative outcome. A person will only engage in a social exchange transaction if he believes the transaction will be successful. As a result, if the perceived benefits outweigh the perceived costs, people will engage in and support. As a result, one of the most important factors in defining the diaspora’s attitudes toward tourism is the perceived value of the social exchange outcome. In this regard, SET has helped to explain the diaspora’ behavior in connection to tourism impacts by providing a conceptual foundation for the investigation of interrelationships among perceptions (Kang & Lee, Citation2018). It also aims to determine the diaspora's opinions and proposes a fresh approach to measuring their behavior and explaining why they behave the way they do, as well as the elements that influence them. This is crucial because stakeholder views affect the long-term viability of diaspora-based tourism marketing development.

2.3. Stakeholder Theory (ST)

The Stakeholder Theory (ST) was conceptualised by Freeman (Citation1984) as an organisational management and business ethics heuristic and serves to determine who and what really matters. ST is primarily a theory of management of organisations with a normative core at its centre, hence there is no sharp distinction in the theory between business and ethical issues (Freeman et al., Citation2021). One of ST’s key concepts is that when an organization functions, it enters into a social contract with its stakeholders, necessitating the need to value all stakeholders in the diaspora-based tourism marketing operations. In this sense, ST takes a ground-breaking move by explicitly referring to an organization’s responsibility to constituencies other than shareholders (Freeman et al., 202). ST is based on the idea above argues that diaspora-based tourism marketing will affect a large number of stakeholder groups that it affects and is affected by. ST is concerned with the type of relationships that exist between the CoO and its stakeholders. ST considers all stakeholder groups’ interests to be intrinsically valuable, and no one set of interests is considered to trump the others (Eskerod, Citation2020).

The idea assumes that stakeholders and their ties with the organization are recognized and that this recognition leads to implicitly value- and moral-laden outcomes. The primary goal of ST is to assist CoO and the diaspora in better understanding their stakeholder environments and managing more effectively within the terms of the relationships that exist for their CoO, thereby increasing the value of the outcomes of their activities and reducing the harm to stakeholders. The ability of the diaspora or the CoO to enforce its will in a relationship is referred to as power, whereas legitimacy refers to the idea that an entity’s actions are consistent with norms and values. The degree to which stakeholder demands require quick action is referred to as urgency. stakeholders can be split into primary stakeholders (the diaspora whom the CoO destination would need) and secondary stakeholders (no direct transactional engagement but have influence). The diaspora, on the other hand, are the most important stakeholders in this paper, and CoO would need to effectively implement diaspora-based tourism marketing that will improve tourist traffic to a CoO tourism destination (Zengeya et al., Citation2023).

2.4. The Expectancy Theory (VIE)

Expectancy theory is more interested in the cognitive factors that influence motivation and how they interact (Wang et al., Citation2021). That is, expectancy theory is a cognitive process explanation of motivation based on the belief that there are correlations between the effort people put in at work, the performance they obtain as a result of that effort, and the rewards they receive as a result of their effort and performance. In other words, the diaspora will be motivated if they believe that putting forth a significant effort will result in good results, and that good results will result in the desired rewards. Victor Vroom in 1964 was the first to establish an expectancy theory that could be applied directly to the workplace, and Porter and Lawler in 1968 and others later expanded and refined it (Pinder, Citation1987). Vroom believed that motivation to behave in a certain way is based on the expectation that the effort put in would result in a desired objective (expectancy), or that the work will be rewarded (instrumentality), or that the effort will be worthwhile (valance) (Badubi, Citation2017). Valance-Instrumentality-Expectancy Theory is another name for the theory (VIE). The theory is more of a decision-making process that explains why an individual chooses to engage in one behavior over another.

The Expectancy Theory assesses the motivational potential of various behavioral options as a method of achieving a desired outcome. VIE’s theory of motivation can be applied to develop diaspora-based tourist marketing strategies that will increase tourism traffic. Four assumptions underpin expectation theory (Vroom, Citation1964). One assumption is that the diaspora will help advertise the CoO tourism destination, based on their needs, motivations, and previous experiences. These factors have an impact on how the diaspora reacts to diaspora-based tourist marketing. The diaspora’s action, according to a second assumption, is the consequence of deliberate decision. That is, the diaspora has the freedom to pick the actions that their own expectancy computations indicate. The diaspora, according to a third assumption, demands various things from the CoO. (e.g., good incentives, security, advancement, and challenge). A fourth assumption is that the diaspora will pick among options in order to maximize personal outcomes. The calculation of advantages vs costs is used to motivate people to engage in particular behaviors (Wang et al., Citation2021). As a result, it is possible to conclude that the diaspora can participate in diaspora-based tourism marketing, which will improve tourism marketing with the idea that it will improve his or her chances of being aesthetically appealing, emotionally stable, healthy, and living longer (Zengeya et al., Citation2023).

3. Methodology

There is a general dearth of theoretical capital to understand diaspora-based tourism marketing and tourism marketing improvement. While the hypotheses described have the ability to explain diaspora-based tourist marketing that boosts tourism traffic, a closer examination reveals that they all share one or more traits. To some extent, any of the following hypotheses can be used to explain diaspora behavior. Micro theories such as SET, ST, and VIE are considered micro theories, whereas the fundamental GST is considered a macro and overarching theory. The combination of theories is needed for theoretical triangulation. Thus, this paper sought to highlight a theoretical frame work that will highlight the impact of harnessing the diaspora as tourism marketers to improve tourism traffic factors to Zimbabwe. The theoretical framework will try to ring out according to Zengeya et al. (Citation2023) the potential of DBTM to anchor diaspora-based tourism marketing development, and the knowledge gap on diaspora-based tourism marketing knowledge and how socio-economic factors can be improved through it, using qualitative content analysis of several published empirical information on the subject.

Qualitative content analysis is used to group unstructured material into categories or topics based on reliable deduction and interpretation (Tunison, Citation2023). Through the application of inductive reasoning, themes and categories are extracted from the data by the researcher after rigorous inspection and continuous comparison. The qualitative part of content analysis establishes linguistic units of analysis (such as words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs) and categories for those units, starting with the text body. Any activity that takes a substantial amount of qualitative data reduces it, and attempts to make sense of it while attempting to find its fundamental coherence and meaning is referred to as qualitative content analysis. This approach is typically appropriate when there is a dearth of recent theory or research on a particular topic. Content analysis, in the opinion of Matović and Ovesni (Citation2023) reveals crucial trends, themes, and divisions in social reality. The method analyzes social phenomena in an unobtrusive manner as opposed to simulating social interactions or collecting survey data. The study’s data was compiled from a review of journals, books, papers, and other relevant sources (Diaspora based tourism marketing General Systems Theory (GST)), Leiper’s theory, Social Exchange Theory (SET), Stakeholder Theory (ST), Expectancy Theory (VIE) looked at an infinite amount of materials on the subject, with the majority of them coming from 2019 to 2022. Additionally, classical literature was looked at, with an emphasis on the authenticity part. Themes were employed by the researcher as a basis for analysis. The results and an explanation of the conclusions based on the specified unit of analysis are presented in the following sections (themes).

3.1. Ensuring validity and reliability

Qualitative researches as opposed to quantitative ones use a different measuring scales to ensure reliability and validity of a study. To ensure quality findings, credibility, transferability, dependability and conformability of results were considered. Credibility reflects accuracy in measuring or observing a social phenomenon such as diaspora-based tourism marketing. The researcher made sure that the instruments measured what they intended to measure which is the influence of DBTM to harness the diaspora to improve tourism marketing. Thus, this study sought to gather credible theoretical knowledge on the influence of diaspora-based tourism marketing to improve tourism traffic to Zimbabwe by roping in triangulation of data sources, methods and theoretical perspectives including the verification of how raw data were interpreted (Coleman, 2022). The extent to which the researcher’s assumptions were applied to other context, setting or situation were used as a yard stick for measuring transferability. Creswell (2013p57) is of the opinion that prior to conducting a study it is necessary to gather college or university approval from the institution’s review board for data collection involved in the study. This was observed in this research as the study passed through the Ethics Committee of Chinhoyi University of Technology and was given an ethical number and approval to proceed as the study did not contain information which could harm individuals. However, good ethical practice means that one should think through the appropriateness of each ethical principle to the precise context of one’s research.

Therefore, categorization process was trustworthy in the sense of being consistent: even if different persons would be used to code, the same text will appear in the same way. This is necessary to draw accurate conclusions from the text. Over the course of a lengthy DBTM research process, intensive methodological research efforts are made on the validity, inter-coder reliability, and intra-coder reliability. The degree of agreement or correspondence between two or more coders was frequently used to assess the reliability of human coding.

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions of the General System Theory (GST), Leiper's model, Mills & Morris to DBTM

Results show that the core theories of Bertalanffy can be applied to a variety of systems, including the human body, a country’s economy, a municipality’s political organization, and tourism in any location. With regard to tourism, the distinction between systems thinking and tourism systems theory was made by Leiper (Citation2000). Each of these systems can be analyzed as a whole the united system or broken down into sections to make them easier to understand and research using general systems theory. An environment, units, relationships, attributes, input, output, feedback, and a model are all required for a system to be complete. The major benefit of generic systems theory, permitting to Leiper (Citation1995), is that it clarifies something that would otherwise be complicated.

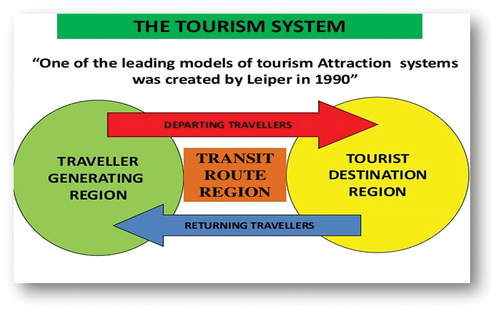

These findings, as highlighted above, are in line with the DBTM theoretical frameworks which focus on understanding the drivers of diaspora-based tourism marketing as the general systems theory (GTS). It is from this that Leiper build his tourism systems model which is highly influential in bring out this discourse as shown Figure Convincing the tourist to travel to a particular tourist destination in this case that is the country of origin needs a push by the diaspora. Also the diaspora will facilitate in the pull factors by manipulating these tourists to the country of origin (CoO) or exposing the destination to the tourist. Figure shows the origins of this model can be traced years back to be developed in the late 1970s by Leiper (Citation1990).

The system involves the discretionary travel and temporary stay of persons away from their usual place of residence for one or more nights that is visitation of the CoO tourism destination by the tourist that is pushed by the diaspora. The arising tours are made for the primary purpose of earning remuneration and an improvement of the tourist traffic in the home country. The elements of the system as shown in Figure are tourists, generating regions, transit routes, destination regions and a tourist industry (Postma & Yeoman, Citation2021). Diaspora-Based tourism marketing has applied these five elements are arranged in a spatial and functional connection that will improve tourism traffic. Having the characteristics of an open system taken from the general systems theory (GTS), the organization of five elements operates within broader environments: physical, cultural, social, economic, political, technological with which it interacts (Jane, Citation2020). Although it has been frequently cited since being first proposed in the late 1970s, no previous studies have considered the applicability of Neil Leiper’s theory of whole tourism systems (Leiper, Citation2004) when it is applied to less conventional forms of travel, such as Diaspora-Based Tourism.

Results show that in the diagram above you can see the way in which Leiper depicted tourism as being a system borrowing from general systems theory (GST) (Postma & Yeoman, Citation2021). The basic elements of Leiper’s tourism system purport that there are three major elements in Leiper’s tourism system: the tourists, the geographical features and the tourism industry (Sandberg & Alvesson, Citation2021). The tourist is the actor in Leiper’s tourism system and they move around the tourism system, consuming various elements along the way. Jane (Citation2020) explains the tourism industry as, of course, at the heart of the tourism system. All of the parts that make up the structure of tourism are found within the tourism system. While the geographical features of Leiper’s tourism system, Leiper identifies three main geographical regions in his tourism system. These are visually depicted in the diagram 4.1.1 above. The traveler generating region is the destination in which the international tourist comes from and it is the same place where the diaspora who will market is located. If, for example, a person is taking an international holiday, where the diaspora is then the town or place where the diaspora is who has persuaded an international tourist to purchase a sale will almost certainly be classified as the “traveler generating region”. However, in the case of diaspora-based tourism marketing, the precise details of our home locations become less important. Thus in this case, the generating region may refer instead to the country or district in which the diaspora is living in instead of the home country. Within the traveler generating region there are many components of tourism information about the place the international tourism would want to visit. Hence, the need for different stakeholders in tourism such as travel agents, tourism marketers (diaspora) and tour operators, who promote outbound tourism.

Discussions show that the tourist destination region can largely be described in the same vain in this case becomes the tourism country of home origin for the diaspora. In Leiper’s tourism system, the tourism destination region is the area that the tourist is visiting (Postma & Yeoman, Citation2021). Thus, the tourist destination is the home country of origin from which the diaspora comes from, the international tourist that the diaspora would have persuaded to purchase a sale to their home country would then visit this diaspora tourism home country destination region. The tourist destination region could be an entire Country. For example, Zimbabwe. Likewise, it could be a just a Province which has tourism activities in it, such as the eastern highlands. Or it could even be a town, such as Victoria Falls. In the tourist destination region you will find many components of tourism. Here you will likely find hotels, tourist attractions, tourist information centres, etc. (Leiper, Citation2004). The last geographical region identified in Leiper’s tourism system is the tourist transit region. The tourist transit region is the space between when the tourist leaves the traveller generating region and when they arrive at the tourist destination region. This is effectively the time that they are in transit. The tourist transit region is largely made up of transport infrastructure. This could be by road, rail, air or sea. It involves a large number of transport operators as well as the organisations that work within them, such as catering establishments (think the shape of great Zimbabwe at the Robert Mugabe airport in Zimbabwe). The tourist transit region is an integral part of Leiper’s Tourism System (Glanz, Citation2017).

Discoveries show that there are many benefits of Leiper’s tourism system which also could be drawn from the general systems theory (GST). Leiper’s model allows for a visual depiction of the tourism system (Lohmann & Panosso Netto, Citation2017). Like the general systems theory (GST), the model is relatively simple, enabling the many to comprehend and use this model. Leiper’s tourism system model has been widely cited within the academic literature and widely taught within tourism-based programmes at universities and colleges for many years. The way in which this model demonstrates that the different parts of the tourism industry are interrelated and dependent upon each other provides scope for better planning and development of tourism (Sandberg & Alvesson, Citation2021). There are, however, also some disadvantages to the general systems theory (GST) that also apply to Leiper’s tourism system model. Whilst the simplicity of the general systems theory can be seen as advantageous, as it means that it can be understood by the many rather than the few, it can be argued that it is too simple. These disadvantages also are seen in the tourism systems model, because the model is so simple, it is subject to interpretation, which could result in different people understanding it in different ways. Leiper developed this theory back in 1979 and a lot has changed in travel and tourism since then (Glanz, Citation2017). Take, for example, the use of the Internet and the element of marketing. This is why this research does not use the general systems theory only but supports this theory with other theories that will help in the building of the whole diaspora tourism-based framework. In the tourism systems model the marketing agent in this case the diaspora does not fit, because they have little place in either the traveler generating region or the tourist destination region. The post-modern tourism marketing industry is not haccounted for in this model, thus it can be argued that it is limited in scope because it is outdated. Likewise, this model fails to address the way in which the tourism system is actually part of a network of interrelated systems (Jane, Citation2020).

4.1.1. Adding tourism marketing to the General System Theory (GST)

Results demonstrated that Mill and Morrison (Citation1985) provided a model of the tourism sector that was also based on general systems theory after examining Leiper’s model’s inadequacies (GST). The idea included marketing as part of the tourism system (Mill & Morrison, Citation1985). The chain’s most important link is marketing. There should be a referee (the diaspora) who starts the game where the activity takes place (country of origin tourism destination). Marketing raises public awareness of a product and a service. Tourism marketing done by the diaspora will result in a win–win situation for the diaspora, the traveler, and the home country. Mill and Morrison (Citation1985) saw tourism as a system made up of four elements: destination, market, and marketing, as well as their interrelationships: travel purchase, travel demand shape, travel demand selling, and reaching the market place (Postma & Yeoman, Citation2021).

Results show that the majority of tourism activity occurs in tourist locations. Destinations, not surprisingly, have emerged as the core unit of study in tourism, and they are a pillar in any tourism system modeling. Because travellers are now spoilt for choice of destinations, they must compete for attention in markets cluttered with messages of substitute products as well as rival places, it is necessary to sell travel to the intended market through a motivated diaspora marketing agent (Zengeya et al., Citation2023). As a result, when the concept of harnessing the diaspora is used, travel procedures, practices, and sales become the means by which tourism marketing and tourist traffic improve. The tourism destination region as shown in Figure uses the diaspora to reach out to potential clients and persuade them to buy their tourism products and services. The diaspora serves as a breeding ground for tourism marketing, effectively acting as a driving force to motivate, stimulate, and encourage tourist travel. The diaspora as marketers strives to attract tourists to visit the diaspora’s home of origin for tourism activities during tourism marketing. As a result, the tourist is encouraged to seek out information on bookings and travel arrangements to the tourism destination zone, as well as to purchase the trip. This approach increases tourist traffic and sales of the destination’s (5 A’s) accommodations, activities, amenities, transportation availability, and ancillary services.

4.2. The Social Exchange Theory (SET) in DBTM

However, just like any other theory, SET contains flaws (Cao et al., Citation2022). It has a tendency to oversimplify human relationships by defining them solely in terms of costs and benefits, leaving out important elements such as power, trust, culture, and equity, all of which can influence stakeholders’ perspectives. Because of differences in cultural contexts, race and diaspora location, which SET tends to overlook, what a diasporas’ views as a benefit to international tourist may differ. Furthermore, the value of a reward changes over time. The social exchange theory was first summarized as cost and benefit, which is useful for quantitative study (Zhang et al., Citation2021b). With more investigation, it has become clear that there are some phenomena in the sphere of tourism that the social exchange theory cannot explain and that the social exchange theory cannot adequately describe some complex difficulties. In other words, individuals’ expectations of behavior reward can influence the likelihood of activity. As a result, users’ opinions and action intentions can be predicted. This has been used to explore trust (Dewi et al., Citation2020). For example, convincing by the diaspora to an international tourist that has built trust purchase of a travel to the home country can be seen by an improvement in tourist traffic continuously coming.

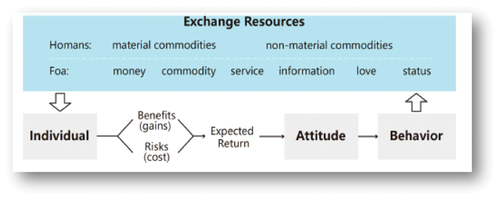

Deliberations show that social exchange resources are divided into six categories: love, status, service, information, commodity, and money (James et al., Citation2021). For example, it is easier to exchange money for products than for a diaspora to convince a purchase to the international tourist. Thus, in the context of diaspora-based tourism marketing, the interactive forms and exchange contents between the diaspora and the tourist a mutual understanding is required. Pallant et al. (Citation2022) pointed out that social exchange theory is a useful framework to understand toward any exchange that is diaspora, international tourist and country of origin exchange. Yang et al. (Citation2015) adapted their research and identified six features, including visual beauty, navigation, entertainment, community-driven, security, and visitation-friendliness, as driving factors for international tourist to participate in diaspora-based tourism marketing. The social exchange behavior and resource classification are summarized in Figure based on the aforementioned theoretical research.

Figure explains that individuals like the diaspora and the international tourist both evaluate behavioral incentives, measure the benefits (gains) and hazards (costs) of exchanging information and resources, and then generate exchange willingness and conduct the purchase of a sell to improve tourist traffic. The degree of an individual’s propensity to exchange is directly related to the level of expected return, which impacts the potential and sustainability of exchange behavior (Pallant et al., Citation2022). Human success, stimulation, and value propositions are summed up in the possibility of conduct between the diaspora and the international tourist is equal to the value of an improvement of a sale to the tourist destination CoO multiplied by the probability. Aiding in the explanation and comprehension of international tourists’ perspectives, attitudes, and support for diaspora-based tourism marketing and traffic improvement.

4.3. Stakeholder’s theory in DBTM

Findings show that stakeholder definitions can change over time and from author to author as argued by Freeman et al. (Citation2021), a stakeholder is any individual or group that can affect or be influenced by the CoO’s activities. As a result, ST highlights the perceptions and interests of many stakeholders that must be recognized in order to boost tourism traffic through diaspora-based tourism marketing. Agreeing to the Stakeholder Theory, the site’s value must be shared by all stakeholders in society who may have an interest in the CoO. However, the diaspora support and participation in diaspora-based tourism marketing will vary because of their heterogeneity in perceptions of tourism of CoO. Stakeholder theory is divided into three dimensions: normative, instrumental, and descriptive. The normative dimension, which is at the heart of ST, demands CoO to act in a fair and morally acceptable manner toward stakeholders. From this perspective, all stakeholders having an interest in tourism should be fully appreciated, regardless of their level of interest or authority (Keremidchiev, Citation2021). The descriptive viewpoint examines, among other things, what the CoO will actually do in terms of managing various stakeholders. ST can articulate the many elements of tourism found in a CoO tourist location, as well as the policy framework in diaspora-based tourism marketing that will increase tourism marketing, depending on this aspect. Most successful destination tourism countries that involve the diaspora have aligned themselves with guidelines and principles of ST.

Stakeholder theorists suggest that individuals who are affected by the diaspora’s decisions and activities should regulate it. They propose that decision-making frameworks be put in place that allow individuals who will be affected by the decisions to participate. The ST is founded on basic legal ideas and concepts that promote social welfare and accountability in general (Sheehy, Citation2005). Because the theory has greater commitments to the diasporic society than only receiving remittances and compassion, the rights and interests of all parties should be decided exogenously. Before the circle spreads to include the diaspora around the world, the diaspora closest to the CoO should usually be prioritized. On the other hand, the theory has been criticized. Breaking down a theory into normative, instrumental, and descriptive theoretical worlds is a type of reductionism that is not just ineffective but also ineffective. Even critics of the theory have acknowledged its potential to tap into most diaspora members’ profound emotional devotion to their family and tribe, as well as their engagement in diaspora-based tourist marketing that will increase tourism traffic to their CoO.

4.4. Expectancy theory (VIE) in DBTM

Results show that expectancy is concerned with the effort–performance relationship, whereas Instrumentality is concerned with the performance–reward relationship, and Valance is the value associated with the outcome (reward) (Vroom, Citation1964). Expectancy Instrumentality Valancy is the Motivation Force (MF) in this situation. As a result, if any of these criteria is zero (0), the person will be unmotivated to act. Figure depicts the three major aspects of the expectancy theory based on these assumptions: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. The diaspora is motivated if he or she believes that (a) effort will result in acceptable performance (expectancy), (b) performance will be rewarded (instrumentality), and (c) the value of the benefits will be high (valence).

Figure explains that a person’s estimate of the likelihood that job-related effort will result in a specific level of performance is known as expectation. Expectancy is a scale that spans from 0 to 1 and is based on probabilities (Wang et al., Citation2021). The expectancy is zero if the diaspora believes that no amount of effort will result in the expected level of performance. The expectancy, on the other hand, has a value of 1 if the diaspora is absolutely positive that the task will be accomplished. Generally, employee expectations for the future are somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. The diaspora’s estimation of the likelihood that a specific level of task performance will lead to various job outcomes is referred to as instrumentality. Instrumentality, like expectation, ranges from 0 to 1. The instrumentality has a value of 1 if the diaspora believes that a good performance rating will always result in an incentive. The instrumentality is 0 if there is no apparent association between a positive performance rating and an incentive (Badubi, Citation2017).

Findings display that the strength of the diaspora’s preference for a particular reward is known as valence. As a result, incentives, tourism destination marketing, peer approval, CoO recognition, or any other reward may have different levels of value for the diaspora. Valences, unlike anticipation and instrumentality, can be positive or negative. Valence is positive if the individual has a strong preference for obtaining a reward. Valence is negative at the other end of the spectrum. If the diaspora is uninterested in a reward, the valence is zero. The overall range is −1 to + 1. A reward has valence in theory because it is tied to the wants of the diaspora. As a result, valence provides a link to motivational need theories (Alderfer, Herzberg, Maslow, and McClelland). Motivation = Expectation x Instrumentality x Valence, according to Vroom, is a relationship between motivation, expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. In the equation, the multiplier impact is considerable. When anticipation, instrumentality, and valence are all high, it leads to higher levels of motivation than when they are all low. Because of the multiplier assumption, if any one of the three elements is zero, the overall degree of motivation is likewise zero. Even if the diaspora believes that his or her work will result in performance, which will result in a reward, motivation will be zero if the valence of the reward he or she expects to receive is zero that is if the reward he or she will receive for his or her effort has no worth to him or her.

Considerations display that it is critical for the diaspora to understand the reward system at work. Statements of intent must be accompanied by concrete actions. When it comes to relating performance to incentives, compensation mechanisms can be a potent motivator. These incentive systems will allow diaspora members to choose their fringe benefits from a menu of options. Another difficulty that may arise as a result of expectancy theory is the necessity for CoC to reduce the appearance of countervalent rewards, or performance incentives with negative valences. Meanwhile, rewards may be determined by a variety of different factors unrelated to DBTM. As a result, this theory fails to account for the impact of diaspora-based tourism marketing on tourism marketing and the interconnection between the diaspora, foreign tourists, and the CoO tourism destination.

4.5. Insights from the theories discussed

The findings reveal that while the fundamental GST is regarded as a macro and overarching theory, micro theories like SET, ST, and VIE are micro theories. For theoretical triangulation, the combination of theories is required. However, the challenge of combining theories is complicated by the concept of the incommensurability of theories. That is there is no basis for comparing and understanding theoretical perspectives. The researcher therefore adopts this theoretical framework with an element of pragmatism to suit the study. These four theories closely complement each other and the decision to arrive at the four theories is informed by the link between the theories and DTBM. The researcher assumes that the impact of SET’s shortcomings can be reduced by ST which complements by further explaining cost–benefit relationships and examining the interconnectedness of stakeholders within diaspora-based tourism marketing (DBTM). ST also complements the SET in explaining the diaspora's perceptions and attitudes and managing diverse perspectives and interests of other stakeholders. Apart from that, ST incorporates fundamental concept of power which is excluded in the SET and SLF. The holistic perspective inherent in the SLF to capture the complexity of development problems and rural poor livelihoods will also go a long way in compensating the shortcomings of SET.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, using a study of general systems theory, the subject of determining the present tourism marketing methods used to direct tourism traffic to Zimbabwe is addressed (GST). Using stakeholders theory, the subject of identifying vulnerabilities in existing tourist marketing techniques in DBTM was discussed, this then contributed to the formulation of the interview guides. Using the social exchange theory (SET) and the Expectancy theory, in-country residents and diaspora opinions on how the diaspora community might be organized to boost tourism traffic to Zimbabwe are revealed (VIE). Finally, all of the theories are applied to determine how the diaspora’s role as tourist marketers might be integrated into a framework that improves tourism traffic to Zimbabwe.

6. Implications for the theory

Findings showed that to come up with a diaspora-based tourism marketing framework that harnesses the diaspora to improve tourism traffic, a theoretical framework which comprises four theoretical perspectives which are General Systems Theory (GST), Social Exchange Theory (SET), Stakeholder Theory (ST) and Expectancy Theory (VIE) can been adopted. General System Theory (GST): The main theory that anchor DBTM is the GST, which gives a bases for the Leiper’s tourism systems model and the Mills and Morris tourism marketing systems model from where the conceptual framework of DBTM was derived. It is from GTS that Leiper developed the tourism systems model and this model is a basis in which some of the elements of diaspora-based tourism marketing framework are taken from. After examining Leiper’s model’s flaws, Mill and Morrison (Citation1985) offered a model of the tourism industry that was also based on general systems theory (GST). The notion incorporated a marketing component into the tourism system (Mill & Morrison, Citation1985). Marketing is the crucial link in the chain. The link between the GDS, Leiper’s tourism model and Mills and Morris’s tourism marketing model in relation to DBTM was then analysed in detail in the methodology. As stated above, these theories built a base for the framework and findings on the strategies that could be adopted involving the diaspora in marketing Zimbabwe as a tourism destination. In order to gain insights on the Strategies that may be adopted involving the diaspora in marketing Zimbabwe as a tourism destination. The specifically addressing the main theories that may be adopted involving the diaspora in marketing Zimbabwe as a tourism destination. Thereby giving birth to a diaspora-based tourism marketing framework.

6.1. Implications for research

The theories will anchor the study, which aims to develop a diaspora-based tourism marketing theoretical framework that would be adopted by the diaspora to increase tourism traffic. Therefore, it would be prudent to test the theoretical framework for feasibility and applicability. A similar study using quantitative research approaches is worth proposing. This would assign numerical value to the actual contribution of the theories to diaspora based tourism marketing that improves tourism traffic. For instance, it would yield quantitative data on the number of diaspora that would patronize the idea of the theories used to build diaspora-based marketing. There is also a need for further studies testing scientifically the participant’s claims the possibility of theorizing them.

Disclosure statement

I Rudo Zengeya and my coauthors state that we have no interests to declare,

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rudo Zengeya

Rudo Zengeya Nyandima is a Doctor of Philosophy student at Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe. My research topic includes Diaspora based tourism marketing DBTM, improvement of tpurism traffic and socio-economic factors. My DPhil thesis being prepared with the assistance of my two supervisors Professor Patrick Walter Mamimine and Dr Molline Chiedza Mwando is about creating a diaspora based tourism marketing (DBTM) framework .

Patrick Walter Mamimine

Prof Patrick Walter Mamimine holds a PhD in Sociology of Tourism from University of Zimbabwe. He lectured in Tourism and other social science For the past 20 years and is a renowned researcher in the areas of tourism.

Molline Chiedza Mwando

Molline Chiedza Mwando- GuI‹ushu holds a PhD in Tourism Management from North-West University in South Africa and an MSc in Tourism and Hospitality Management from the University of Zimbabwe.. She has spent over eighteen years working in the Tourism field with fifteen of the years practising as an academician.

References

- Adongo, R., Kim, S., & Elliot, S. (2019). “Give and take”: A social exchange perspective on festival stakeholder relations. Annals of Tourism Research, 75(75), 42–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.005

- Ahn, Y. J. (2022). City branding and sustainable destination management. Sustainability, 14(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010009

- Badubi, R. M. (2017, August). Theories of motivation and their application in organizations: A risk analysis. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development, 3(3), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.18775/ijied.1849-7551-7020.2015.33.2004

- Beni, M. C. (2001). Análise Estrutural do Turismo (4th ed.). Senac-São Paulo.

- Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General system theory. George Braziller.

- Cao, E., Jiang, J., Duan, Y., & Peng, H. (2022). A data-driven expectation prediction framework based on social exchange theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783116

- Çepni, S. (2021). How to structure the conceptual and theoretical framework of projects, thesis and research articles? Journal of Science, Mathematics, Entrepreneurship and Technology Education.

- Dewi, S. N., Riani, A. L., Harsono, M., & Setiawan, A. I. (2020). Building customer satisfaction through perceived usefulness. Quarterly Access Success, 21, 128–132.

- Emerson, R. M. (1962). Social exchange theory.

- Eplerwood, M., Milstein, M., & Ahamed-Broadhurst, K. (2019). Destinations at risk: The invisible burden of tourism. The Travel Foundation.

- Eskerod, P. (2020). A stakeholder perspective: Origins and core concepts. Business and Management. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.013.3

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman.

- Freeman, R. E., Dmytriyev, S. D., & Phillips, R. A. (2021). Stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1757–1770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206321993576

- Glanz, K. (2017). Social and behavioral theories. Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. www.esourceresearch.

- Hughes, S., Davis, T. E., & Imenda, S. N. (2019). Demystifying theoretical and conceptual frameworks: A guide for students and advisors of educational research. Journal of the Social Sciences, 58(1–3). https://doi.org/10.31901/24566756.2019/58.1-3.2188

- James, T. L., Shen, W., Townsend, D. M., Junkunc, M., & Wallace, L. (2021). Love cannot buy you money: Resource exchange on reward-based crowdfunding platforms. Information Systems Journal, 31(4), 579–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12321

- Jane, T. (2020), Fact checking trump’s comments on COVID-19 virus. NBC News. www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/fact-checking-trump-s-comments-COVID-19virus-n1143856

- Kang, S. K., & Lee, J. (2018). Support of marijuana tourism in Colorado: A residents’ perspective using social exchange theory. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.03.003

- Keremidchiev, S. (2021). Theoretical foundations of stakeholder theory. Икономически изследвания, 30, 70–88.

- Leiper, N. (1990). Tourism systems: An interdisciplinary perspective. Department of Management Systems, Massey University.

- Leiper, N. (1995). Tourism Management. RMIT Press.

- Leiper, N. (2000). Systems theory. In J. Jafari (Ed.), Encyclopedia of tourism (pp. 571). Routledge.

- Leiper, N. (2004). Tourism management (3rd ed.). Pearson Education Australia.

- Leslie, D. (2000). Holistic approach. In J. Jafari (Ed.), Encyclopedia of tourism (pp. 281). Routledge.

- Lohmann, G., & Panosso Netto, A. (2017). Tourism theory: Concepts, models and systems. Griffith University. Australia. ISBN :9781780647159. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780647159.0000

- Matović, N., & Ovesni, K. (2023). Interaction of quantitative and qualitative methodology in mixed methods research: Integration and/or combination. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 26(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1964857

- Mensah, I. (2022). Homecoming events and diaspora tourism promotion in emerging economies: The case of the year of return 2019 campaign in Ghana. In Marketing tourist destinations in emerging economies (pp. 211–229). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83711-2_10

- Mill, R., & Morrison, A. (1985). The TourismSystem. Prenctice Hall.

- Ozel, C. H., & Kozak, N. (2017). An exploration study of resident perceptions toward the tourism industry in Cappadocia: A social exchange theory approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(3), 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2016.1236826

- Pallant, J. I., Pallant, J. L., Sands, S. J., Ferraro, C. R., & Afifi, E. (2022). When and how consumers are willing to exchange data with retailers: An exploratory segmentation. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 64, 102774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102774

- Pinder, C. C. (1987). Valence-instrumentality-expectancy theory. In R. M. Steers & L. W. Porter (Eds.), Motivation and work behavior (4th ed., pp. 69–89). McGraw-Hill.

- Postma, A., & Yeoman, I. S. (2021) A systems perspective as a tool to understand disruption in travel and tourism. 7 1 2021, pp. 67–77, Emerald Publishing Limited, ISSN 2055-5911.

- Sandberg, J., & Alvesson, M. (2021). Meanings of theory: Clarifying theory through typification. Journal of Management, 58(2), 487–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12587

- Sheehy, B. (2005). Scrooge-the reluctant stakeholder: Theoretical problems in the shareholder –stakeholder debate, 14U. Miami Business Language Review, (193), 193–239.

- Tunison, S. (2023). Content analysis. In J. M. Okoko, S. Tunison, & K. D. Walker (Eds.), Varieties of qualitative research methods Springer texts in education (pp. 85–90). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_14

- Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. Jossey-Bass.

- Wang, H., Gui, H., Ren, C., & Liu, G. (2021). Factors influencing Urban residents’ intention of garbage sorting in China: An extended TPB by integrating expectancy theory and norm activation model. Sustainability, 13(23), 12985. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132312985

- Yang, K., Li, X., Kim, H., & Kim, Y. H. (2015). Social shopping website quality attributes increasing consumer participation, positive eWOM, and coshopping: The reciprocating role of participation. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 24, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.01.008

- Zengeya, R., Mamimine, P. W., & Mwando, M. C. (2023). Diaspora based tourism marketing conceptual paper: A conceptual analysis of the potential of harnessing the diaspora to improve tourism traffic in Zimbabwe. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2164994. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2164994

- Zhang, C., Dong, X., Zhang, S., & Guan, J. (2021a) The application of social exchange theory in tourism research: A critical thinking. In The 2021 12th International Conference on E-business, Management and EconomicsJuly 2021 (pp. 683–687). https://doi.org/10.1145/3481127.3481242

- Zhang, C., Dong, X., Zhang, S., & Guan, J. (2021b) The application of social exchange theory in tourism research: A critical thinking. The 2021 12th International Conference on E-business, Management and EconomicsJuly 2021 (pp. 683–687). https://doi.org/10.1145/3481127.348124s2