Abstract

Among the many verticals in India’s rich kaleidoscope of tourism services, agritourism offers a vivid rural experience to tourists. National and state-level tourism policies focused on agritourism play a pivotal role in its performance enhancement. Despite its potential, the country needs a foundational framework through a National Tourism Policy. This missing link encouraged us to conduct a scoping review to synthesize and understand policy interventions in India aimed at promoting agritourism by following the guidelines espoused by Arksey and O’Malley. Individual policies of India’s states and union territories were synthesized to understand the significance of agritourism in the region. We also searched for scientific articles on Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar that focused on agritourism development through policy dimensions and regulatory frameworks. The results are presented through the lens of Carol Bacchi's framework. In the final review, 23 documents were included. Our findings reflect an urgent need to develop and implement policies that define strategic and financial support to encourage farmers to take up agritourism on their land. In addition, the development of agritourism policies must be followed by implementation and monitoring through definitive institutional mechanisms.

1. Introduction

India’s landscape is decoratively dotted with diversity in topography, traditions, culture, languages, and most importantly, people. Home to world-class tourism services ranging from medical to adventure and agriculture to coastal, various stakeholders of the travel and tourism industry in India are investing time and energy to amplify the sector’s potential to the world. This would not only increase tourist footfall, but also boost the economy through increased revenue and employment (Sanjeev & Birdie, Citation2019). Being one of the oldest civilizations in the world, India offers copious tourism verticals that are age old, modern, and contemporary. Even as a modern nation equipped with state-of-the-art technology and scientific prowess, India is deeply embedded in its culture, history, and spirituality, as it continues to exude a mystic appeal to attract tourists from all over the world.

With an incredible count of 981 protected areas, including Wildlife Sanctuaries, National Parks, Community Reserves and Conservation Reserves, India also has 40 UNESCO World Heritage sites as of 2022. There is visible evidence of infrastructure development in terms of connectivity through prolific railways, modern roads, avant-garde airports, and improved technology through the Internet by creating a virtual space for tourists (Kumar et al., Citation2021). While the Picturesque Himalayan stretch covers five lakh square kilometres, the breathtaking coastline is 7500 km long. India has set the stage for the emergence of tourists as a significant driver that will take the country’s economy to a great height. The contribution of the travel and tourism Industry to India’s GDP was 6.9% in 2019, and the year 2021 saw an 11% increase in tourists’ footfalls in India with $8.797 billion in forex earnings compared to 2020 (Ministry of Tourism Government of India, Citation2022). With a roadmap and strategically designed vision, India has the potential to witness a surge in tourist movement in terms of international arrivals and domestic tourists.

The effect-recovery theory developed by Meijman and Mulder (Citation2013) and the conservation of resources theory developed by Hobfoll prove that traveling for leisure opens the gateway to relaxation, control thoughts and emotions, and detach from everyday work. Consequently, tourism recreation has gained momentum. Today, the tourism industry offers services beyond clichés. For instance, Dark Tourism promotes places associated with tragedy, grief, death, or a dark history. Polar tourism encourages vloggers, photographers, and leisure travellers to visit the Arctic and Antarctic regions to experience their surrealistic landscapes. Additionally, wellness tourism offers wellness enhancement services, film tourism promotes popular movie and series’ destinations, slum tourism or “ghetto tourism” encourages visits to impoverished areas, medical tourism aligned with medical treatment, ecotourism to explore the undisturbed areas, adventure tourism for the adrenaline seekers, coastal tourism that lays out the picturesque beaches, enotourism or wine tourism to take a nice walk in the vineyards alongside wine-tasting, sleep tourism that offers sleep-enhancing amenities in the place of stay, cultural tourism that highlights the diverse culture of the place, business tourism that involves traveling for work, culinary tourism for the food enthusiasts, fashion tourism to enjoy, experiment, discover, study, trade and buy fashion, music tourism to experience musical festivals or music performances, religious tourism to visit the holy sites and agri-tourism for those who want to experience life on a farm and take part in agricultural activities, are a few among a range of tourism services.

Parallelly, the government encourages farmers and promoters to practice agritourism—one of the pivotal verticals of the tourism industry—on their farms by offering subsidies and schemes at the state level that benefit agritourism promoters. Given the role played by policymakers in transforming the rural tourism landscape to become resilient (Augustyn, Citation1998; Brune et al., Citation2023), the aim is also to encourage tourists to become acquainted not only with agricultural activities but also immerse themselves in various aspects of rural life, such as local cuisine, traditions and culture, arts, and sports (Dsouza et al., Citation2022; Shah et al., Citation2023). This will improve destination image (Alderighi et al., Citation2016; Choe & Kim, Citation2018), help farmers earn beyond farming activities, and connect tourists to the authenticity of the local region (Sims, Citation2009; Zhanget al., Citation2019). To further encourage this, the Government of India is taking bold steps to make India a world leader in tourism by 2047. The state of Maharashtra launched the Agritourism Development Corporation (ATDC) to encourage farmers to take up agritourism by offering training and conducting skill development programs. Kerala launched Sustainable, Tangible, Responsible, Ethnic Tourism (STREET) in May 2022, a project that pioneered the offering of tourists a taste of experiential tourism in the unexplored rural lands of the state. Today, many states are incorporating similar models to gently push farmers in India to indulge in agritourism and boost tourist footfall in rural areas.

Despite India’s tremendous tourism potential and developmental initiatives at the state level, the government has been unable to develop or provide a concrete National Tourism Policy. Moreover, Tourism in India is not listed in either the Union, State, or Concurrent list. The dire need for a guiding National Policy is the need of the hour. Of the 28 states and eight Union Territories (Government of India, Citationn.d.), Arunachal Pradesh is the only state that does not have a tourism policy, while Andaman Nicobar Islands, Jammu & Kashmir, and Lakshadweep are the only UTs that do. In addition, fewer states and UTs promote agritourism as a revolutionary tourism vertical. Based on the gaps in the current landscape of tourism policies, this review attempts to synthesize and understand the policy interventions aimed at promoting agritourism in India.

2. Methodology

With the surge in primary research, there has been a continuous growth and evolution of reviews. Tricco and Colleagues (Tricco et al., Citation2016) identified 25 different types of knowledge synthesis methods and one among these is scoping reviews, sometimes called scoping studies or mapping reviews (Anderson et al., Citation2008). Scoping review explores the vastness of the literature in the area, maps and summarizes the evidence, and paves the way for future research (Gudi et al., Citation2022; Tricco et al., Citation2016). It is a widely used tool to develop “policy maps” by finding and mapping evidence extracted from reports and policy documents that act as a beacon for various stakeholders in a field (Anderson et al., Citation2008). In the process of mapping policies, it is fundamental to define what policy means. Policies are “government statements that include laws, orders, decisions, or regulatory frameworks, formulated to achieve predefined goals, and solve societal problems by touching upon the core function of democratic politics through agenda setting, policy formulation, policy adoption, policy implementation, and evaluation” (Knill & Tosun, Citation2008; Newton & Van Deth, Citation2021). Policy is also defined as a “law, regulation, procedure, administrative action, incentive or voluntary practice of governments and other institutions” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC, Citation2013). It is additionally defined as a “set of discourses, decisions, and practices driven by governments, sometimes in collaboration with private or social actors, with the intention to achieve diverse objectives related to tourism” (Velasco, Citation2016). We put together these three definitions and defined Tourism Policy as a “government statement that includes laws, orders, decisions, regulations, procedures, administrative actions, and incentives driven by governments, private organizations, and social actors either individually or as a combined force with the intention to achieve diverse tourism objectives”.

To conduct a scoping review and understand emerging evidence (Peterson et al., Citation2017), we followed the JBI methodology framework for scoping studies. The JBI methodology has six fundamental steps that act as a guide to conduct a rigorous and transparent scoping review that includes identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selection of study, charting the data, collating, summarizing, and reporting the results, and consulting with consultations (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

2.1. Step 1: Identify the research question

In the first step, we identify the research question, as our goal is to synthesize India’s state-wise tourism policies carefully. The Context, Interventions, Mechanisms and Outcomes (CIMO) framework is often considered while framing management and policy-related questions in the context of scoping reviews (Tranfield et al., Citation2003). The CIMO framework details the different elements of our research question by extracting the details of the approach, as shown in Table .

Table 1. Description of CIMO Framework

Following are the research questions:

What are the various policy interventions in India to promote Agritourism?

How many tourism policies in the state and union territories promote agritourism in the region?

2.2. Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

In the second step, we identified relevant studies by following a two-pronged approach so that we would not omit any information on various tourism policies. The two-pronged approach involves 1) government websites dedicated to publishing tourism policies, and 2) searching for articles in scientific journals. Given that tourism policies formulated in various states across India are predominantly available on government-regulated websites, we ran extensive searches using Google Search and Google to ensure that all state-wise tourism policies were included in the review process. Authors KD and NG developed a clear and comprehensive search strategy to identify relevant studies in the domain. Through this, we looked for supporting evidence on SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google Scholar using the Boolean Operators “AND,” “OR” between keywords as depicted in Table .

Table 2. Search strategy

Articles from the first 10 pages on Google Scholar were considered for the study, and we found that relevant authors such as Galluzzo (Galluzzo, Citation2017a; Galluzzo, Citation2017b, Citation2021), Zhao et al (Zhao et al., Citation2022), Carla Barbieri (Barbieri, Citation2019; Santeramo & Barbieri, Citation2016) and a few others have extensively conducted research that calls for the development of robust agritourism policies. The search for articles was independently carried out by the primary author (KJD) in consultation with the subject experts.

2.3. Step 3: Study Selection

The next step involved the selection of tourism policies, related reports, and studies that mentioned agritourism policies. This was performed independently by two reviewers (KD and PD), and discrepancies in the selection of articles were resolved through a consensus-building approach in the presence of the team. The evidence base guarantees accuracy and comprehensiveness with a high-quality search of resources and relevant information available in the electronic form (McGowan et al., Citation2016). We included tourism policies developed and implemented by state and union governments in India that had sections focusing on agritourism development. We restricted our studies to those published in English and included tourism policies beginning from 1982 to 2022 (previous and current policies), as the first tourism policy was introduced in 1982. From the point of view of the exclusion criteria, we excluded redundant and vague reports published on the Internet and did not include research articles that did not fall within the scope of our study, that is, agritourism policies. “Agritourism” OR “Agrotourism” OR “Farm tourism” OR “Farm-based tourism” AND “Policy Intervention” OR “Regulation” OR “Plans” OR “Strategy” OR “Scheme” OR “Guideline” AND “India” OR names of individual states and union territories in India. The final decision and reasons for inclusion and exclusion of articles at the full-text stage and those of tourism policies are attached to Multimedia Appendices 1, 2, and 3.

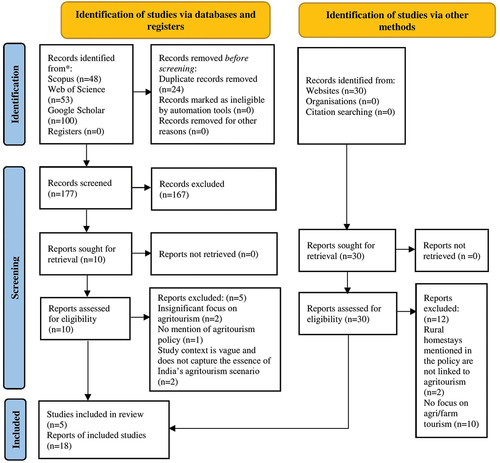

To ensure that the review process was transparent, the inclusion of records at every stage was presented using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 (BMJ 2021;372:n71) chart, along with clear reasons for inclusion and exclusion of the reports, as shown in Figure . We made three attempts to access the websites until the end of data extraction. If all three attempts fail to access the website(s), the same is/are considered as “not functional.”

2.4. Step 4: Charting the Data

This was followed by data coding. The template for data coding was finalized after consulting the reviewing team, and minor changes suggested by the team were incorporated into the final template. A similar approach has been advocated by Levac et al. (Citation2010) and Daudt et al. (Citation2013). The data were coded according to the characteristics of the policy documents based on the latest version, scope of the policy, policy timeline, relevance to agritourism, subsidies, and grants, as depicted in multimedia Appendices 4 and 5. Additionally, in case of information deficiency in policy documents, we referred to other relevant official government websites of the state to elicit more information.

2.5. Step 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Owing to the heterogeneity and vastness of tourism policies, we summarized the findings using narrative synthesis to offer a comprehensive outline of the implications of tourism policies on the agritourism sector.

Although the sixth and last step to be incorporated was stakeholder consultation, given that coding was done for tourism policies and research articles, consulting a stakeholder from the tourism sector for summarizing results was beyond the scope of the project.

3. Results

We present the findings of this scoping review based on evidence collected through a search for scientific articles and policies.

3.1. Results of scientific articles

Based on the search for scientific articles on Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, the initial search yielded a total record of 201 articles. We removed 24 articles as they were duplicates. Following this, titles, and abstracts of 177 articles were screened by two authors (KD and PD) independently, and we considered 10 articles for full-text screening that were included for data coding/abstraction, which was done independently by two authors (KD and PD) independently. Among these, we excluded five articles, of which two articles had insignificant focus on agritourism, one article did not address agritourism policy, and the study context of two articles was vague and did not capture the essence of India’s agritourism scenario.

3.2. Results of policies—identified via other methods

As the primary purpose of our scoping review revolved around agritourism policy analysis, we looked for the tourism policies of individual states and UTs published by governments on regulated websites. We found that India is yet to transition from the current draft National Tourism Policy (2002) to a fully functional National Tourism Policy that will further strengthen the bond between tourism and agriculture. We retrieved 30 tourism policies, including draft policies of 27 states and three UTs, given that one state and two UTs did not have a tourism policy, while three UTs had Tourism Perspective Plans that were not considered in our scoping review. We retrieved all 30 documents to look for the agritourism provisions made in them. Among the 30 policy documents, we excluded a total of 12, of which two policies mentioned rural homestays but not link them to agritourism, while 10 policies did not focus on agritourism or related aspects.

For the final analysis of agritourism provisions in the policies, we considered 23 documents, of which five were scientific articles and 18 were policy documents. A PRISMA chart representing the screening process for scientific articles and policies is presented in Figure .

3.3. Summary of scientific articles

Despite the Government of India launching flagship campaigns such as Incredible India and Bharat Parv, the tourism sector has not received the attention it deserves. As one of the very few sectors promoting rural entrepreneurial development, tourism has the potential to ensure social equity in a fast-growing economy such as India. This is possible with the implementation of right policies that reflect the nation’s aspirations and claims towards India’s copious resources. Over the years, India has worked towards expanding its tourism infrastructure, introducing private-public-partnerships, and developing new places of attractions to bring in more foreign as well as domestic tourists. Undoubtedly, tourism policy and development are interrelated, as one largely depends on the other. However, the need of the hour is to formulate and introduce strategic frameworks that promote a conducive environment of partnership between stakeholders of the tourism industry in India that will further enhance sociocultural relationships, revenue generation, resource sustainability, and foreign exchange. A summary of the scientific articles included in this review is presented in Table .

Table 3. Summary of scientific articles included for the review

3.4. Summary of policies identified via other methods

Upon careful analysis of tourism policies, we deduce that of the 28 states and eight union territories in India, two UTs (Dadra & Nagar Haveli & Daman & Diu and Ladakh) and one state (Arunachal Pradesh) do not have a tourism policy (draft/plan/policy). The State of Meghalaya and UT of Lakshadweep has draft tourism policies while three UTs (Chandigarh, Delhi, and Puducherry) have “Twenty years Tourism Perspective Plan.” The perspective plans were sanctioned by the Department of Tourism, Government of India, for the development of tourism in the given state of UT. The current agritourism policies curated and executed by the states and UTs across India target service providers and community partners as it encourages them to start or develop agritourism enterprises and centres in the region. The definition of subsidies, schemes, and monetary plans revolves around harnessing the incredible potential of promoting agritourism based on the regions’ rich traditions and culture. Moreover, these policies encourage modern agricultural practices with a blend of regions rich in cultural heritage that can be leveraged to promote tourism by encouraging community participation in parallel. In addition, these policies provide training and skill development to farm owners and service providers through relevant institutions and agencies. The existing facilities of the Department of Agriculture, Department of Horticulture, and district authorities may be leveraged to support the rollout of Agri Tourism programmes and training in the smoothest manner. A summary of the tourism policies included in the review is presented in Table .

Table 4. Summary of tourism policies included for the review

4. Discussion

Tourism in India casts both negative and positive effects on a wide array of stakeholders. Government, tourists, community, service providers, promoters, and employees experience different kinds of repercussions from tourism policies, schemes, subsidies, community perception, employee-employer relationships, their attitudes and behaviour, tourist footfalls, and their attitudes and behaviours towards various elements of the tourism industry. Among these, the government plays a key role in shaping the tourism sector and paving the way for its future development through thorough policy. In this context, a government is considered a technical, strategic, artful, and inventive assemblage created from elements that are diverse and distinctive in nature (Dean & Hindess, Citation1998, p. 8). In continuation of this and complimenting the definition, the WPR (“What’s the Problem Represented to be?”) approach looks at a government beyond how its entity is, and this significantly differentiates the approach from a majority of policy analysis methods. Therefore, we have discussed the findings of our study in light of the Carol Bacchi approach.

The WPR approach uses the concept of “problematization” in two ways. One way in which “particular issues are conceived as ‘problems,’ identifying the thinking behind particular forms of rule” and second as an “interrogation” of current policies. In other words, this approach encourages an entity to make the paradigm shift from “problem-solving” to “problem-questioning” that changes the whole narrative around the process of policy analysis.

Policies are framed by the notion and presumption that they address issues. This further underscores the assumption that problems do exist and that they need to be “identified” and “rectified” (Bacchi, Citation2009). The WPR approach offers an elaborate methodology to interrogate and evaluate “problematizations” by means of extraction and scrutiny of the problem representations that they comprise. The six-step methodology contains six questions that help ascertain, assess, and resolve the problems, as represented in Table . We attempt to address these questions by carefully assessing India’s National and State agritourism policies, as well as scientific articles that speak about agritourism policies in the country.

Table 5. Six-step questions of the WPR approach (Bacchi, Citation2009)

We set the parameters by focusing on all national, state, and UT tourism policies and scientific papers that propagated tourism policies in India. Given the vastness of tourism policy, we were aware that the policies and research papers selected for the analysis would carry reference to forms of tourism other than our context, that is, agritourism. This led us to conduct an extensive analysis of policies and research papers to look for texts that focused specifically on India’s agritourism sector through a scoping review through Carol Bacchi's WPR approach.

4.1. WPR Question 1: “What’s the problem represented to be in India’s tourism policies?”

The first question of the WPR approach is how to define the problem. Among the tourism policies of twenty-seven states and six UTs, 13 states and UTs had no provision or mention of agritourism or related aspects. Among the 20 documents that encouraged the development of agritourism, 17 policies were unclear on subsidies, loans, and state-funded investments, or had given minimal importance to agritourism. The process of creating a sustainable policy involves recent, relevant, and up-to-date knowledge of the matter at hand collected through analytical tools (Agarwal & Somanathan, Citation2005; Wu et al., Citation2021) which is evidently lacking in policies. In addition, given that the movement of international and domestic tourists carries a chain of effects on aspects related to logistics, the food and beverage industry, real estate, and banking, the role of agritourism and its impact on other sectors is a link that is missing from policies. Current agritourism policies have shortcomings due to the dearth of information on inter-sectoral effects and effects on the different stakeholders of the industry.

There is a lack of a comprehensive definition of what the term “agritourism” entails in policies. Moreover, policies are framed in adherence to different attributes of the sector, while the measurement of the policies associated with pursuing its goals is done by using policy measurement instruments, such as cost-benefit analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis to name a few (Capano & Howlett, Citation2020). Our investigation showed that the policies did not include performance indicators or policy implementation plans (PIP), as shown in Table . As the policies are generally implemented for five years, suitable performance measurement instruments and policy indicators can be developed to gauge the success of these policies.

4.2. WPR Question 2: “What presuppositions or assumptions underlie this representation of the ‘problem’?”

As the 7th largest country in the world, India has a total land area of 3,287,263 square kilometres and a total population of 1.4 billion that is growing exponentially on a daily basis. The magnanimity of a country presents its own set of challenges for policymakers and governments. Over the years, India has been negotiating multiple socio-economic issues and challenges, such as population explosion, rapid urbanization, security threats, increasing demand for energy, growing consumption, and environmental degradation among others (Bhardwaj et al., Citation2021). India’s post-independence era has seen drastic changes in the way the economy functions. Reforms have been brought about in sectors related to education, health, banking and finance, trade, agriculture, logistics, tourism, hospitality, etc. Public policies have been characterized by anticipating needs, reactions, or impacts that can have a reasonably foreseeable effect on future economic development.

Policies associated with the tourism industry are being developed and implemented based on information, exogenous changes, and needs of the industry. However, policies in most states and UTs reflect obsolescence. This calls for more frequent changes in policies, which are not always a viable option for governments and policymakers. Agritourism, however, is a hybrid form of tourism that is at an early stage in India. Although the fusion of agriculture and tourism carries a plethora of potential, there are instances of setbacks from service providers and policymakers in improving agritourism as a pivotal vertical of India’s tourism sector. For instance, the cultural values that are deep-seated among service providers, that is, farmers being attached to their land and resources, prevent them from welcoming the thought of farm diversification through agritourism due to lack of awareness and information. Few policies have clear provisions set aside for the development of agritourism, but most policies reflect a structural absence on the roadmap to develop agritourism through clear subsidies, loans, and state-funded investment plans.

4.3. WPR Question 3: “How has this representation of the ‘problem’ come about?”

Over the years, sustainable rural development has been a topic of strategic and policy discussion worldwide. Agritourism in India has been growing as the pinnacle of sustainability in rural areas and has played a significant role in bringing India to the fore through its novel initiatives in some regions across the country. However, the trajectory of growth can be improved given the abundance of resources, such as culture, traditions, agricultural land, and historical ties. The problem underlying this slow growth is reflected in tourism policies, as states like Bihar, Kerala, Nagaland, and Tamil Nādu followed policies that were introduced over 15 years ago, despite states like Tamil Nādu and Kerala witnessing an influx of tourists (Kerala Tourism, Citation2019).

Travellers who wish to experience agritourism arrive with the aim of connecting with the authenticity of the local region. This thirst among travellers needs to be catered to by service providers, that is, owners and promoters of agritourism establishments. Tourism policies that entail the development of agritourism are seen as a foundation for service providers. Therefore, clarity on financial schemes, resource assistance, and initiatives requires more clarity and strength. Given that agriculture in India is taking short strides towards attaining success, the introduction of tourism means additional income and less gullibility for farmers who aim at income diversification through farm operations. Therefore, problems in current agritourism policies, such as a lack of definition, clarity, and direction, can be addressed and resolved by aiming for transparency and robustness.

4.4. WPR Question 4: “What is left unproblematic in this problem representation? Where are the silences? Can the ‘problem’ be thought about differently?”

While tourism policies are formulated and looked over by a committee of experts, strategists, and monitoring panels at the state and nodal levels, there is a need to introduce forward and backward linkages among stakeholders in the agritourism sector such as service providers, self-help groups, co-operatives, and other service providers. Information and technology associated with the policy reach are hindered as service providers and tourists are unaware of the benefits and services, respectively (Devasia & PV, Citation2022) while links between community groups and private—public players are absent to further the cause of the agritourism policy. These problems can be resolved swiftly, given the plethora of resources available to states. Public—private partnerships based on the Social-Equity model for the development of Agritourism have great potential to enhance the social and economic growth of farmers through a strategic approach (Ministry of Tourism Government of India, Citation2022) through organized farm groups and co-operatives in which farmers in a given area are registered members. One of the key points of the draft tourism policy is to introduce digitization through which entrepreneurs can make their business known to prospective tourists; tourists can look for an agritourism stay based on their requirements, while the government can keep tabs on the activities while also making new initiatives and schemes known to service providers (Government of India, M. of T, Citation2022).

Policies can be produced such that their execution is swift and successful. While most tourism policies are made with a vision for the next five years, there could be provisions to make the necessary changes based on need. This calls for close involvement of policymakers during the policy formulation phase (Agarwal & Somanathan, Citation2005). In addition, there needs to be a balance between centralized and decentralized controls so that the interests and priorities of the implementers do not supersede those of the public. Control can be revolved around but not limited to process and quality by ensuring that these agritourism policies are connected to reality and are made with conscious efforts to resolve issues and further the cause. Agritourism in India is growing at a considerable pace but needs policymaking that provides for an “appropriate separation between the policy and implementation functions,” as posited by Williams (Citation1998).

4.5. WPR Question 5: “What effects are produced by this representation of the ‘problem’?”

Given the talks revolving around sustainability and eco-friendliness, the policies encourage innovative agri-business activities related to tourism and agriculture, with a considerable focus on organic farming through rural tourism. Few policies call for identifying villages practicing unique forms of handicrafts, music, dance, art, cuisine, rural lifestyles, possessing unique ecological significance, or following distinct agricultural practices, thus promoting them in international and domestic markets as destinations for experiential tourism. Through this, villages with core strengths in handlooms, handicrafts, etc. can be developed with a view to facilitate income to producers, ensure continuance of the craft, and offer an offbeat experience to tourists. However, there is less focus on tourists, as fewer policies encourage schemes that can enable tourists to travel to rural locations and experience the daily activities of the village.

The current representation of the problem sheds light on the scattered focus on stakeholders. While few policies concentrate on tourists, some concentrate on service providers and the community. The success of agritourism can materialize through strong synergies between stakeholders. Communities, rural artisans, governments and policy makers, local offices, service providers, SHGs, and tourists need equal and unbiased importance in policies, while the dissemination of relevant information, follow-up, and reviews are prioritized.

4.6. WPR Question 6: “How/where has this representation of the ‘problem’ been produced, disseminated, and defended? How could it be questioned, disrupted, and replaced?”

In India, excessive structural fragmentation and a lack of objectivity are two of the primary problems associated with agritourism policymaking. This is underscored by the fact that there is no National Tourism policy despite regular changes and updates in the draft policy, and the tourism sector does not belong to the state, union, or concurrent list. The top administrative tourism agency at the national level is the Ministry of Tourism, which takes the lead in policy formulation, regulatory framework, and promotion (Incredible India Campaign). This organization is also the nodal point for coordination and communication between the centre, state/UTs, and private agencies that promote tourism. However, over the years, the ministry has focused more on international tourism and paid less attention to the coordination and development of tourism sub-sectors. On the other hand, the tourism ministry at the state and UTs are vested with the responsibility of developing state policies based on national policies and implementing both at the state level. Therefore, this gives states more leverage and flexibility to make necessary provisions for different verticals of tourism. Despite these provisions and the proven potential of the sector, the states have not been able to give the desired attention to the development of agritourism. Taking due cognizance of the complimenting roles of the states and centre in the development and implementation of a robust agritourism policy framework, there is certainly a need to improvise the provisions set down in these policies, but more freedom and flexibility if offered to the states and UTs can pave the way for better agritourism reforms and regulatory frameworks.

Agritourism enterprises are run by farmers and owners of farmlands, which means they carry expertise in the area of agriculture and partly tourism. Currently, agritourism policies are being formulated by experts and authorities at the bureaucratic level. Contrary to this, there can be an acknowledgement of the fact that expertise often lies beyond and outside the government. Inputs can be taken as potential suggestions from stakeholders affected by the policies. The impact of an agritourism policy is on service providers, tourists, local communities, and related groups. Such initiatives can not only offer multiple viewpoints for policy assessment, but also garner trust and confidence from stakeholders towards the implementation and success of the policy. Therefore, agritourism policies may be developed through stakeholder consultation, constructive debates, and pragmatic provisions with objectives that can be attained within the stipulated timeline.

In the context of Agritourism, the concept of “spillover economic development” takes place when visitors and tourists eat, stay, and shop local. More importantly, operations on each agritourism farm are unique to its resources and region that keeps the local business within the community. Achieving success in agritourism business comes with its own set of hurdles but a carefully devised policy frameworks can make the enterprise profiting, engaging, and successful. A dedicated committee in each state may be vested with the responsibility to oversee the development of agritourism with a sustainable approach. Tailor-made models for regional development in agritourism are also necessary for careful utilization of local resources that can be used to create experiential and essential services to visitors and tourists. The functioning of these models must be comprehensively explained to the farmers and service providers so that they can be encouraged to open their doors to the tourists. This can not only increase their income but also educate the tourists about agriculture and related aspects. Clearly defined regulations, coordination and support from local government bodies such as village panchayats, skill development workshops for farmers and youths to hone their competency in customer service and farm sustainability, organizing training programmes, introducing digitization, and establishing dedicated clearance windows for licensing and loans can contribute tremendously towards promoting the broad spectrum of India’s agritourism. Policy enabled backward and forward linkages between home cooks, farmer markets, rural artisans, and self-help groups can create a healthy environment for diversifying income, selling farm produce, marketing local commodities and improving ties respectively. Introducing agritourism service providers to strategic collaborations with online platforms and other travel traders in the area for the purpose of bookings and marketing can also be beneficial. Provisions can be made to foster the idea of entrepreneurship by exposing the youth and farmers to agritourism experts who can teach the villagers about crop diversity, cattle rearing, craftsmanship, organic food, handloom, handicrafts, and sustainable farm practices. A carefully curated agritourism policy has the potential to strengthen rural India’s ecological endurance, promote its culture and most importantly, make the farmers economically resilient. A rigorous agritourism policy can fuel the rural development through acquired benefits that will be shared among all the service providers within the rural economy.

5. Strengths and limitations

Our search was extensive for both scientific articles and government-formulated tourism policies to capture maximum information on the status of agritourism policies in Indian the states and UTs. A search for scientific articles—review and research articles—was conducted to identify relevant authors in the area and the extent of studies that focused on agritourism development in India. The search for tourism policies of individual states and UTs in India was conducted to understand and analyse the robustness of agritourism promotion in India. Although the search for scientific articles was thorough, with regard to policies, we did not include government funded “twenty-year tourism perspective plans” of UT of Puducherry, Delhi and Chandigarh as they focus on analysing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of tourism in the region. Including these documents would offer more information on the region, but given that our study focused on current policies, we did not include these documents in our review process.

6. Conclusion

This review underscores the emergent need to develop robust agritourism policies at the state and union territory levels that are pragmatic, achievable, stakeholder-centric, and transparent. There is a definite need to develop a National Tourism Policy with provisions for agritourism development that can act as a beacon to all states and UTs to develop suitable policies for their region to develop tourism, in our context, agritourism. The current situation necessitates the inclusion of clearly defined subsidies, loans, and investment plans to encourage promoters/owners of agricultural farms to diversify beyond farming and benefit from the copious amount of resources available on their lands. The policy makers can leverage the sustainably innovative attributes of agritourism to not only encourage the existing farmers to venture into tourism but also attract the youth to explore the various dimensions of agritourism. Promoting agritourism pushes for employment opportunities, economic upliftment of rural areas, community welfare, protection of art and culture and sustenance of agriculture in the long run. In parallel, the wheels of policy development, implementation, and monitoring must be put into motion through institutional mechanisms focused solely on the development of agritourism.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (44.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2283922

References

- Agarwal, O., & Somanathan, T. (2005). Public policy making in India: Issues and remedies. https://www.igntu.ac.in/eContent/IGNTU-eContent-353062467985-MA-PoliticalScience-4-Dr.GeorgeT.Haokip-Paper401PublicPolicyandDevelopmentinIndia-Unit2.pdf

- Ahamed, M. (2018). Indian tourism-the government endeavours resulting into tourism growth and development. International Journal on Recent Trends in Business and Tourism (IJRTBT), 2(1), 7–18.

- Alderighi, M., Bianchi, C., & Lorenzini, E. (2016). The impact of local food specialities on the decision to (re)visit a tourist destination: Market-expanding or business-stealing?. Tourism Management, 57, 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.016

- Anderson, S., Allen, P., Peckham, S., & Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-6-7

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Augustyn, M. (1998). National strategies for rural tourism development and sustainability: The Polish experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 6(3), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589808667311

- Bacchi, C. L. (2009). Analysing policy : What’s the problem represented to be?. Pearson.

- Barbieri, C. (2019). Agritourism research: a perspective article. Tourism Review, ahead-of-print(1), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/tr-05-2019-0152

- Bhardwaj, S., Dubash, N., Mukhopadhaya, G., & Aiyar, Y. (2021, December 21). Policy Challenges 2019-2024: The Big Policy Questions and Possible Pathways. CPR. https://cprindia.org/policy-challenges-2019-2024-the-big-policy-questions/

- Brune, S., Knollenberg, W., & Vilá, O. (2023). Agritourism resilience during the COVID-19 crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 99, 99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2023.103538

- Capano, G., & Howlett, M. (2020). The knowns and unknowns of policy instrument analysis: Policy tools and the Current research agenda on policy mixes. SAGE Open, 10(1), 215824401990056. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019900568

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). Step by Step – Evaluating Violence and Injury Prevention Policies 2 Figure 2. The Briefs in Relation to the Steps in the CDC Evaluation Framework. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/pdfs/policy/Brief%201-a.pdf

- Choe, J. Y. & Kim, S.(2018). Effects of tourists’ local food consumption value on attitude, food destination image, and behavioral intention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 71, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.11.007

- Daudt, H. M., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Dean, M., & Hindess, B. (1998). Governing Australia: Studies in contemporary rationalities of government. Cambridge Uk Cambridge University Press.

- Devasia, D., & PV, S. K. (2022). Promotion of tourism using digital technology: An analysis of Kerala tourism. In Handbook of technology application in tourism in Asia (pp. 403–422). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2210-6_19

- Dsouza, K. J., Shetty, A., Damodar, P., Shetty, A. D., & Dinesh, T. K. (2022). The assessment of locavorism through the lens of agritourism: The pursuit of tourist’s ethereal experience. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, (2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677x.2022.2147566

- Galluzzo, N. (2017a). The common agricultural policy and employment opportunities in Romanian rural areas: The role of agritourism. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 23(1), 14–21.

- Galluzzo, N. (2017b). The impact of the common agricultural policy on the agritourism growth in ital. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 23(5), 698–703.

- Galluzzo, N. (2021). A quantitative analysis on Romanian rural areas, agritourism and the impacts of European union’s financial subsidies. Journal of Rural Studies, 82, 458–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.025

- Government of India. (n.d.). States uts - know India: National portal of India. Knowindia.india.gov.in. https://knowindia.india.gov.in/states-uts/

- Government of India, M. of T. (2022, September). India tourism statistics 2022 | Ministry of tourism | government of India. Tourism.gov.in. https://tourism.gov.in/annual-reports/india-tourism-statistics-2022

- Gudi, N., Swain, A., Kulkarni, M. M., Pattanshetty, S., & Zodpey, S. (2022). Tobacco prevention and control interventions in humanitarian settings: a scoping review protocol. British Medical Journal Open, 12(7), e058225. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058225

- Knill, C., & Tosun, J. (2008). Policy making. In D. Caramani (Ed.), Comparative politics (pp. 495–519). Oxford University Press.

- Kumar, P., Mishra, J. M., & Rao, Y. V. (2021). Analysing tourism destination promotion through Facebook by destination marketing Organizations of India. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(9), 1416–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1921713

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- McGowan, J., Sampson, M., Salzwedel, D. M., Cogo, E., Foerster, V., & Lefebvre, C. (2016). PRESS Peer review of Electronic search strategies: 2015 Guideline statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75(1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

- Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (2013). Psychological aspects of workload. In A handbook of work and organizational psychology (pp. 5–33). Psychology press.

- Ministry of Tourism Government of India. (2022). https://tourism.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-09/Draft%20National%20Tourism%20Policy%202022%20Final%20July%2012.pdf

- Newton, K., & Van Deth, J. W. (2021). Foundations of Comparative politics. Second). Cambridge University Press.

- Pandey, T., & Joshi, P. (2016). Institutional frameworks in community-based tourism policy frameworks for an ‘inclusive India’ with emphasis on Farmer Producer organizations (FPOs). Amity Research Journal of Tourism, Aviation and Hospitality, 1(1), 55–70.

- Peterson, J., Pearce, P. F., Ferguson, L. A., & Langford, C. A. (2017). Understanding scoping reviews. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 29(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12380

- Sanjeev, G. M., & Birdie, A. K. (2019). The tourism and hospitality industry in India: Emerging issues for the next decade. Worldwide Hospitality & Tourism Themes, 11(4), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/whatt-05-2019-0030

- Santeramo, F. G., & Barbieri, C. (2016). On the demand for agritourism: A cursory review of methodologies and practice. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(1), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2015.1137968

- Shah, G. D., Gumaste, R., & Shende, K. (2023). Allied Farming-Agro tourism is the tool of revenue generation for rural economic and social development analyzed with the help of a case study in the region of Maharashtra. Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, 11, 1–15.

- Sharma, G. (2022). Evolution of tourism policy in India: An overview. International Research Journal of Engineering & Technology (IRJET), 9(5).

- Sharma, T. (2020). Tourism policy and implementation in India: A center versus State tug-of-war. In Advances in hospitality and leisure (Vol. 13, pp. 143–153). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1745-354220170000013008

- Sims, R. (2009). Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580802359293

- Singh, S. (2002). Tourism in India: Policy pitfalls. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 7(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660208722109

- Tourist Statistics | Kerala Tourism. (2019). Kerala tourism. https://www.keralatourism.org/touriststatistics/

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of Systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., Levac, D., Ng, C., Sharpe, J. P., Wilson, K., Kenny, M., Warren, R., Wilson, C., Stelfox, H. T., & Straus, S. E. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

- Velasco, M. (2016). Tourism policy. In Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance (pp. 1–6). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_2674-1

- Williams, W. (1998). Review of who’s in Control?; locked in the Cabinet, by R. Darman & R. Reich. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 17(2), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6688(199821)17:2<334:AID-PAM13>3.0.CO;2-I

- Wu, J. S., Barbrook-Johnson, P., & Font, X. (2021). Participatory complexity in tourism policy: Understanding sustainability programmes with participatory systems mapping. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103269

- Zhang, T., Chen, J., & Hu, B. (2019). Authenticity, quality, and loyalty: Local Food and sustainable tourism experience. Sustainability, 11(12), 3437. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123437

- Zhao, Z., Xue, Y., Geng, L., Xu, Y., & Meline, N. N. (2022). The Influence of Environmental values on consumer intentions to participate in agritourism—A model to extend TPB. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 35(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-022-09881-8