Abstract

The recent expansion of the war in Ukraine calls for a better understanding of EU-Ukraine relations. This paper explicates the legitimation of EU foreign policy regarding Ukraine during and after the Orange Revolution. The aim of this paper is twofold. First, this research aims to uncover the intent behind the EU’s legitimation discourse vis-à-vis Ukraine following the Orange Revolution. An analysis of the EU’s legitimation discourse vis-à-vis Ukraine after the Orange Revolution fulfils the second aim of this paper: filling a gap in International Relations scholarship on EU-Ukraine relations. Following a formal- and content-related analysis of argumentation schemes, this paper argues that the EU perceived the Orange Revolution as an opportunity with which it could test its European Neighbourhood Policy in order to legitimise it taking action on the global stage. Since this paper helps to understand the legitimation of EU foreign policy towards Ukraine, it might provide a basis for the analysis of EU foreign policy regarding Ukraine in other timeframes and towards other states in the post-Soviet space.

1. Introduction

In 2004, the European Union (EU) experienced its biggest enlargement to date, which created the need for the Union to rethink its relations with its new neighbours. Ukraine was one of these new neighbours and it experienced an event called the Orange Revolution in 2004–2005. As this research will show, the EU perceived the Orange Revolution as an opportunity to strengthen itself. This paper poses the following question: how has the EU discursively legitimised its foreign policy action towards Ukraine during and after the Orange Revolution?

In particular, this paper will explicate which categories of legitimation strategies the EU has employed to justify its foreign policy actions regarding Ukraine in its discourse. The approach to legitimation will follow the example given by Wodak in her book The Politics of Fear. In her first chapter, Wodak follows a definition of legitimation created by Berger and Luckmann in order to create a framework for analysing the language of legitimation. The definition by Berger and Luckmann states that “ … Legitimation is the process of ‘explaining’ and justifying. Legitimation justifies the institutional order by giving a normative dignity to its practical imperatives. It is important to understand that legitimation has a cognitive as well as a normative element. In other words, legitimation is not just a matter of ‘values’. It always implies ‘knowledge’ as well.” (2015). This definition is key, as it shows that legitimation strategies focus on explaining and justifying. This links strategies of legitimation directly to argumentation as a discursive strategy, which focuses on a persuasion of claims of truth and normative rightness (Reisigl, Citation2017). Argumentation, like legitimation, entails explaining and justifying. Legitimation strategies may thus inherently contain argumentation schemes. This is the case when a legitimation belongs to the category of rationalisation legitimations, as rationalisation legitimations directly refer to argumentations and knowledge claims (Wodak, Citation2015). Argumentation schemes and legitimation strategies may, on the other hand, both contain discursive constructions of social actors. The discursive strategies of legitimation and argumentation are therefore the key variables in this research.

The analysis of these variables followed a formal- and content-related analysis of argumentation and led to the following conclusions. First, the EU’s legitimation of its foreign policy focused on justifying the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Action Plan, as it was the main basis for EU-Ukraine relations that was being discussed before and after the Orange Revolution.

Second, the dominant type of legitimation employed by the EU is the rationalisation legitimation. Particularly the means orientation was used most frequently. This can be explained by the fact that the EU’s policy towards Ukraine was very goal-oriented: it focused on the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Action Plan.

A third conclusion is that the moral evaluation legitimation was also frequently used by the EU.

A fourth conclusion is that the EU viewed the Orange Revolution as an opportunity to test its European Neighbourhood Policy, the successful application of which it then used to legitimise itself taking action on a global stage.

The methodology employed to reach these findings is the discourse historical approach (DHA) of critical discourse analysis. The DHA, as defined by Wodak, works with four levels of context: first, the immediate language or text internal co-text (which constitutes the distinct and unique utterances of politicians); second, the intertextual and interdiscursive relationship between utterances, texts, genres and discourses (which constitutes analysing the reformulations, recontextualisation and the mediatisation of these utterances by politicians); third, the language external social variables and institutional frames of a specific situational context (which constitutes the detailed chronology of events); and fourth, the broader socio-political and historical context in which the discursive practices are embedded and to which they are related (Rheindorf & Wodak, Citation2018).

Following the methodology of the DHA, this paper will be structured as follows. First, the socio-political historical context regarding EU-Ukraine relations up until the Orange Revolution will be given. The following section sets out the discursive strategies, which are the categories of analysis of this research. This section will also explicate argumentation schemes. A discussion of the results of the analysis will follow, after which the last section will provide a conclusion and recommendations for further research.

1.1. Literature review and relevance of the research

Critical discourse analysis is a relatively new field of studies: as a network of scholars emerged only in the early 1990s (Wodak, Citation2001). Influential scholars include Fairclough, Van Dijk, Wodak and Krzyżanowski.Footnote1 Within the scholarship of International Relations, discourse scholars have been represented as a community (Milliken, Citation1999). This representation has been constructed both from the outside and by discourse scholars themselves. Milliken however shows that “Discourse theorizing crosses over and mixes divisions between post-structuralists, postmodernists and some feminists and social constructivists.” (1999) Therefore, CDA is a critical and multifaceted approach that is used in a variety of ways. Fundamentally, the CDA is “concerned with analysing opaque as well as transparent structural relationships of dominance, discrimination, power and control as manifested in language” (Wodak, Citation2001). Indeed, the analysis of power relations are a fundamental aspect of CDA. As such, CDA can be applied to a wide arrange of issues in International Relations, including foreign policy, which is the subject of analysis of this paper.

Aydin-Düzgit has explored the potential of CDA in analysing foreign policy. Aydin-Düzgit shows that discourse analytical approaches to EU foreign policy have been particularly valuable in shedding light on the identities and subjects constructed through EU foreign policy discourse (albeit with certain shortcomings). (2014) CDA combines the macro and micro analyses of texts in the context of EU foreign policy by employing refined linguistic and argumentative tools (Aydin-Dügzit, Citation2014). One of those tools would be an analysis of predication and argumentation strategies, which is suited “to identifying the ‘type’ of foreign policy actor that the EU is, as well as the values that it is based on” (Aydin-Dügzit, Citation2014). Indeed, CDA is able to deconstruct the foreign policy of the EU. Therefore, applying a CDA to foreign policy could be used to analyse important notions in International Relations scholarship, one of which being the classical realist notion of nationalistic universalism. While investigating how Morgenthau employed his notion of tragedy to approach the nation state, (2014) Kostagiannis explains that nationalistic universalism was a new form of nationalism that emerged in the twentieth century. (2014) Nationalistic universalism makes nationalism almost a kind of religion with the purpose of imposing its own values and standards on other countries (Kostagiannis, Citation2014). Indeed, in Morgenthau’s own words: “While nationalism wants one nation in one state and nothing else, the nationalistic universalism of our age claims for one nation and one state the right to impose its own valuations and standards of action upon all other nations.” (Citation1948)

The notion of nationalistic universalism is of interest when it comes to the analysis presented in this paper. The moral and rational legitimations employed by the EU vis-à-vis Ukraine in relation to the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Action Plan show that the EU was intent on spreading its normative values in its neighbourhood, which can be linked to the notion of nationalistic universalism, which states that a nation wants to impose its own valuations and standards of action upon another nation. Indeed, the results of this paper explain why the EU wanted to spread its normative values to its neighbourhood. However, while this paper acknowledges that analysing the concept of nationalistic universalism in relation to the EU’s foreign policy vis-à-vis Ukraine is a worthy endeavour, an application of the concept to this paper does not fit the scope of this research. The focus of this paper is on uncovering the EU’s intent behind its legitimations. Future research should look into whether the EU’s intent relates to the notion of nationalistic universalism. It has to be kept in mind that the application of Morgenthau’s concept of nationalistic universalism might be problematic, since it focuses on states specifically and the prolific debate on the EU’s actorness shows that it is difficult to determine what the EU is exactlyFootnote2 and thus applying a state-centred approach to the EU is difficult as well. Nevertheless, nationalistic universalism is one way of contextualising this research and therefore the results of this paper can be seen as the fundamental building blocks for future research that could apply the results of this paper in relation to the notion of nationalistic universalism. In sum, this paper contributes to the scholarship in International Relations by applying the multifaceted approach of CDA, which (by deconstructing the EU’s foreign policy) can be related to other notions in IR scholarship like nationalistic universalism.

In addition, the relevancy of the results of this paper becomes especially clear when put in the context of current EU-Ukraine relations. With the expansion of the war in Ukraine on 24 February 2022 and the new candidacy status awarded to Ukraine by the EU, (Parker et al., Citation2022) discussions about EU-Ukraine relations and Ukrainian membership receive new attention. Since this paper shows that during the Orange Revolution the EU acted out of opportunism, a study into the legitimation behind the EU’s current actions is also highly relevant. In addition, a study on the reception of the legitimations employed by the EU by Russia and Ukraine would add significant insights as well. The scope of the current paper does not allow for such studies; however, this paper initiates the debate on this issue in the scholarship and recommends such research for the future.

While this paper does not delve into geopolitics per se, it is able to shed light on the development of EU-Ukraine relations. This is relevant especially as Ukraine recently submitted a formal application to join the Union (Brzozowski, Citation0000).

The literature on EU-Ukraine relations is widespread, but a discourse-historical approach to the legitimation of EU-specific policy is a novelty to the field. Hansen applied the theory of rhetorical entrapment to EU-Ukraine relations, showing that the EU placed itself in a difficult position because of its rhetoric. (2006) He argues that the EU portrays inconsistency towards former CIS countries: while it talks about enlargement, it seems unprepared to consider membership in reality. He also shows that while the EU is welcoming Ukraine’s European orientation, a recognition of membership options is absent from declarations. While Hansen’s article does portray the facts of EU-Ukraine relations in 2006, it falls short of explaining what is behind the EU’s rhetoric.

Yehorova, Prokopenko and Popova analyse the semantics of the concept of European integration in European and Ukrainian discourses. (Popova et al., Citation2019) The authors conclude that European integration is differently represented and verbalised by both the EU and Ukrainian citizens. This analysis contributes to our understanding of the concept European integration from both the EU and Ukrainian side and it points to the significance of language in understanding concepts and policies. The present paper tries to understand the justifications of the EU’s foreign policy by applying a methodology that will also highlight the importance of language.

It is important to note that the legitimation of discourse is something that has not been written about extensively in the broader field of International Relations (IR). Examples of research that applies critical discourse analysis (CDA) to analyse discursive strategies are few and none of these examples focus on EU-Ukraine relations.Footnote3 Therefore, this paper aims to fill that gap in the literature by providing a discourse-historical analysis into the legitimation of the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Action Plan.

1.2. Data collection—frontstage events

The data collected for this paper consists of frontstage events. Frontstage events are a specific genre in which discourse is produced (Ekström & Eriksson, Citation2018). What characterises frontstage events is the fact that this genre is thoroughly manufactured, as opposed to backstage events, which is a genre that is usually inaccessible for the wider public. (Wodak and Bernhard, 2018) The distinction between the two is explicated by Wodak and Forchtner: backstage is where the actors are present, but the audience is not. (2018)

This research choses to focus on frontstage events because backstage events are not accessible to outsiders. It is one of the limitations of this paper that the author is unable to go backstage and analyse what was being said in private meetings. While the EU does publish notes and minutes of the meetings of its various institutions, often the salient parts are left out.Footnote4 Therefore, while this paper acknowledges that it would be of value to analyse backstage events, this paper also acknowledges its limitations and will therefore focus on frontstage events for its immediate language or text internal co-text. Specifically, frontstage events that will be analysed are press conferences, press releases, speeches and interviews.

1.3. Time frame justification

The timeframe of the collected data is January 2005 – June 2005. This timeframe has been chosen because it is a significant period in EU-Ukraine relations. As Roth states, the EU-Ukraine Action Plan was negotiated before the Orange Revolution, (Roth, Citation2007) whereas it was implemented in February of 2005 (Solonenko, Citation2007), after the Orange Revolution. The period of January 2005 – June 2005 therefore gives a good overview of justifications of policy before and after the implementation of the Action Plan. As the collected data shows, speeches justifying the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Action Plan appear in April and June, which is why June has been chosen as the end-date of the timeframe.

2. Chronology, history, context

2.1. Socio-political and historical context—Ukrainian independence & a new neighbourhood for the EU

According to Semeniy, the EU’s attitude towards the newly independent states after the collapse of the Soviet Union consisted of two approaches: one towards the central and eastern European states that focused on membership of those countries into the European Union, and one towards the former Soviet states which focused on cooperation alone (Semeniy, Citation2007) Regarding Ukraine specifically, the EU was interested in disarmament and nuclear weapons, whereas Ukraine was interested in political and economic assistance and a legal framework for future relations. In 1994 a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement was signed between the EU and Ukraine.

Semeniy describes how Ukraine has, since the end of the 1990s, actively promoted the idea of future membership of the EU. (2007) Semeniy suggests that while periods of stagnation in this promotion were in the interests of most EU officials, the EU nevertheless continued to extend cooperation with Ukraine, which was exemplified with the 1999 Common Strategy policy document, which specifically “welcomed ‘Ukraine’s European choice’” (2007) and outlined several main objectives: support for democratic and economic reforms in Ukraine; a joint solution of European problems and mutual cooperation in the context of EU enlargement. Semeniy continues and states that the next step in the extension of EU-Ukrainian cooperation, the European Neighbourhood Policy, was criticized by Ukraine as it put the country in the same line with a group of Mediterranean countries with no mention of possible future membership. (2007) Semeniy does mention that this criticism, combined with the Orange Revolution and the adopted EU-Ukraine Action Plan, has led to more options for cooperation being on the table, but that membership was still off the table.

This account of the EU’s approach towards Ukraine directly after its independence shows that from the EU’s perspective, cooperation with and democratic reform in Ukraine were imperative. However, in contrast to the wishes of the Ukrainian government, the possibility of future membership has been ruled out by the EU from the start. The EU was acting pragmatically.

Another account of the EU’s approach towards Ukraine after its independence comes from Maresceau. He states that as his study was being finalised, new reflections on the neighbourhood relations of the enlarged EU were coming in. (2004) This shows that the EU was still processing what to do with its new neighbourhood. As Maresceau put it: “ … the issue of new proximity relations of the enlarged EU is something very concrete and real … The EU now starts to realise this.” (2004) About the Common Strategy document Maresceau states that it is difficult to define what the EU meant with the expression of strategic partnership. (2004) He even goes so far as to state the following: “Actually, it could be anything as long as it does not come too close to EU membership itself.” (2004) Maresceau goes on to describe the contents of the Common Strategy as hollow. While this account of the Common Strategy is very critical, it does show us what scholars at the time thought of the EU’s approach to Ukraine: as something not yet coherent yet.

Maresceau continues his explication of the EU’s approach towards Ukraine by stating that while it is clear that Ukraine aims ultimately at accessing the EU, the EU’s perception on Ukraine’s place in Europe is more complex. (2004) Maresceau states that this complexity was visible in the 1996 Action Plan for Ukraine. In it, the EU proposed support for a plethora of things (economic and social reform, integration in the European security architecture, support for regional cooperation, assistance in reforming the energy sector and the deepening of bilateral contractual relations), but the EU refused to include Ukraine in its enlargement strategy. (2004) What the EU did state was that “over the long term, it (was) a matter for the EU to take not of the request of the Ukraine authorities to secure a firmer anchorage in the European structures and possible membership in the EU” (Maresceau, Citation2004). While examining the Common Strategy, Maresceau suggests that the EU acted out of self-interest, since an understanding of the new neighbour (Ukraine) was indispensable if the EU wished to achieve a safe enlarged EU. (2004) Maresceau states that for the EU, Ukraine’s geographic location is pre-eminently strategic and that the Common Strategy did not take Ukraine’s European expectations into consideration.

The image that both Maresceau and Semeniy paint of the EU’s approach towards Ukraine before the Orange Revolution is one in which the EU acted out of pragmatism and self-interest.

2.2. The Orange Revolution

In 2004, presidential elections were held in Ukraine in which two candidates were the main contenders: Viktor Yanukovych and Viktor Yushchenko. (Zasenko, Citationn.d.) Yanukovych was supported by Russian president Vladimir Putin, who promoted Yanukovych in interviews and public meetings in the week before the first round of the election. (Karatnycky, Citation2005) Yushchenko, on the other hand, campaigned on anticorruption. (Zasenko, Citationn.d.)

The elections were contested. Exit polls had shown that Yushchenko occupied a leading position, with 52% of the votes, whereas Yanukovych was shown to have acquired 43% of the votes. (Karatnycky, Citation2005) Later, however, when the official results came in, Yanukovych had beaten Yushchenko by 2,5%. (Karatnycky, Citation2005) Allegations of fraud were made throughout the day of the elections and the poisoning of Yushchenko months before the election (Karatnycky, Citation2005) might be the most striking evidence that the elections were not conducted in a fair manner.

A day after the elections, amid nationwide protests, Yushchenko installed himself as president and called for a nationwide general strike. (Karatnycky, Citation2005) At that moment, Ukraine had three presidents: the outgoing but still incumbent Kuchma; Yushchenko and the official winner Yanukovych. After days of massive protests, the Ukrainian parliament declared the poll invalid and the supreme court annulled the results of the elections. (Karatnycky, Citation2005) New elections were held.

These new elections, conducted on 26 December 2004 saw Yushchenko win with 52%, whereas Yanukovych received 44% of the votes. (Karatnycky, Citation2005) Yushchenko was inaugurated as president of Ukraine on 23 January 2005. (Zasenko, Citationn.d.)

Taken together, these events (the massive protests, the poisoning of Yushchenko and the annulment of the election results and the subsequent win of Yushchenko) came to be known as the Orange Revolution.

2.3. Importance of the Orange Revolution as context

Understanding the Orange Revolution as context is important for understanding the upcoming analysis. The previous section noted that Yanukovych was supported by the Russian president Putin. Yushchenko, on the other hand, was a pro-Western candidate. Given Ukraine’s long-standing wish of integration with the EU (Maresceau, Citation2004), the victory of a pro-Western candidate intent on fighting corruption Ukraine (Zasenko, n.d.) seems to be a step in the good direction. Recalling Maresceau’s perspective that the EU was unwilling to accommodate Ukraine’s wishes of EU integration before the Orange Revolution, (2004) it is therefore interesting to see whether the EU’s perception of and its legitimation of policies towards Ukraine changed after the Orange Revolution.

3. Categories of analysis—argumentation analysis & discursive strategies

3.1. Argumentation schemes and topoi

In a book chapter, Reisigl provides an extensive overview of argumentation analysis in the DHA. He distinguishes between three types of argumentation analysis: functional, formal and content-related analysis. (2014) The formal analysis of argumentation relies on a reduced functional model of argumentation which integrates three basic elements: argument, conclusion rule, and claim. As Reisigl shows from Kienpointner: “ … the argument gives the reason for or against a controversial claim, the conclusion rule guarantees the connection of the argument to the claim, and the claim represents the disputed, contested statement that has to be justified or refuted.” (2014) In the formal analysis of argumentation, the conclusion rule is seen as central.

The conclusion rule is an argumentation scheme that is also known as topos (topoi plural) (Reisigl, Citation2014). Topoi are central parts of an argumentation that justify the transition from the argument to the conclusion. Reisigl shows that “Topoi are not always expressed explicitly, but can be made explicit as conditional or causal paraphrases such as ‘if x, then y’ or ‘y, because x’.” (2014)

Important to note here is that the formal analysis of argumentation views topoi as something abstract, which is what a content-related analysis of argumentation tries to surpass (Reisigl, Citation2014). A content-related analysis of argumentation views argumentation as being topic-related and field-dependent, which means that according to this perspective topoi are content-related and typical to specific fields of social action. According to Reisigl, content-related topoi tell us more about the specific character of discourse than a purely functional or formal analysis of argumentation would. (2014)

This paper will employ a combination of a formal analysis with a content-related analysis of argumentation. In other words, while a formal analysis of argumentation will form the basis of the analysis, content will be added to the topoi in order to be able to link the analysis to the macro-context of EU-Ukraine relations. Key to this paper is Reisigl’s note on the fact that topoi can be made explicit as conditional or causal paraphrases. This shows us that a formal argumentation analysis can elicit a conditional paraphrase as a specific topos. This allows us to pinpoint conditionality as a topos of a particular argumentation scheme.

3.2. Discursive strategies

Analysing an argumentation scheme is particularly useful since it can also be a specific discursive strategy. In their chapter, Reisigl and Wodak distinguish the following discursive strategies: nomination, predication, argumentation, perspectivisation and intensification and mitigation (Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2009). As Reisigl explains, discursive strategies are a type of category which help to categorise certain discursive features in a text. (2017) For example, the discursive strategy of nomination serves as a categorisation of a discursive construction of social actors, objects, phenomena, events, processes and actions. The discursive strategy of argumentation, on the other hand, serves to categorise arguments employed in discourse and to uncover the validity of specific claims of truth and normative rightness. (2017)

In this research, the concept and strategy of legitimation is particularly useful when analysing argumentation strategies. Since “ … Legitimation is the process of ‘explaining’ and justifying … ” (2015) argumentation schemes and legitimation are inherently connected.

Van Leeuwen and Wodak introduced a framework for analysing the language of legitimation that consists of four categories: authorisation, moral evaluation, rationalisation and mythopoesis (Rheindorf & Wodak, Citation2018). Authorisation legitimation occurs when there is a reference to authority, which can be divided into personal, impersonal, expert or role model authority. The second category, moral evaluation, means legitimation by reference to abstract moral values, for example religious value, human rights or justice. Furthermore, moral evaluations can also be based on evaluative claims, while an analogy to assumedly established moral cases is also possible. Third, rationalisation is legitimation by reference to the utility of the social practice (in other words: rationalisation by way of goals, means or outcomes) or by facts of life (in other words: rationalisation by way of definition, explanation or prediction). Last, mythopoesis is legitimation that is achieved by telling stories that may serve as exemplars or cautionary tales. A more detailed explication of legitimation categories can be found in Table .

Table 1. Legitimation categoriesFootnote5

3.3. Framework of analysis

The analysis of the data proceeded in the following way: first, legitimation schemes were located in the texts. Second, the argumentation schemes in these legitimation schemes were analysed using a formal and content-based argumentation analysis. This analysis deconstructs the EU’s foreign policy discourse on Ukraine and illuminates how it justified its actions regarding Ukraine.

4. Results

4.1. Coding the data

This section will explicate how the data has been coded. An example text from a press release on a statement given by the European Parliament (EP) on the 2005 Ukrainian elections will be provided. This example will show how a legitimation scheme can be located and how argumentation schemes and legitimation strategies can be uncovered. Coding these texts proceeded by answering the following leading questions:

Which action is legitimised?

Which argument is used to legitimise this action?

Which claim is made in this argument?

Which topos is used in this argumentation?

Which category of legitimation is it?

4.1.1. Example text

Example text “MEPs welcomed the ‘substantially fair elections held on 26 December’ in Ukraine, in a resolution adopted by 467 votes in favour, 19 against and 7 abstentions. They congratulated the Ukrainian people for resolving a political crisis and ‘setting their country firmly on the path towards democracy’ in a non-violent and mature way. They said it was now time to consider other forms of association with Ukraine besides the Neighbourhood Policy, giving the country a clear European perspective, possibly leading to EU membership.”Footnote6

Several actions are legitimised in this text.

First, the MEPs congratulated the Ukrainian people. The first argument that is made to legitimise this action is the fact that the Ukrainian people have resolved a political crisis. The second argument is that the Ukrainian people have set their country firmly on the path towards democracy in a non-violent and mature way. Both of these arguments are instrumental rationalisations with the “outcome” orientation, as the focus of this argumentation is on the outcome of the Ukrainian people having performed an action and the effects of that action. The second argument also refers to value systems (non-violence and maturity), which means that the second argument also belongs to the moralisation legitimation category, with the “abstraction” orientation, as the action of setting Ukraine on a path towards democracy is categorised with an abstract moral value. Both of these arguments lead to the claim that therefore, the MEPs congratulating the Ukrainian people is legitimised. The topos of this argumentation is one of explanation, as the argumentation focuses on explaining the action of the MEPs.

The second action that is legitimised is the MEP’s stating that it was now time to consider other forms of association with Ukraine besides the Neighbourhood Policy. This is legitimised by two arguments.

First, the MEPs invoke an earlier argument, namely the fact that the Ukrainian people have set their country on the path towards democracy in a non-violent and mature way. That this argument is employed, can be seen by the use of the word “now”: only now it is time to consider other forms of association with Ukraine besides the ENP. As this argument is the same as the one employed in the previous argumentation structure, it also belongs to the same categories: it is an instrumental rationalisation with the outcome orientation and it also belongs to the moralisation category, with the “abstraction” orientation. The topos for this first argument is one of conditionality: only now, when the Ukrainian people have performed this action, can the MEPs make this statement.

The second argument that the MEP’s use to legitimise their action, is that this considering of other forms of association should be done because doing so could lead to a certain outcome: giving the country a country a clear European perspective could possibly lead to EU membership. This is an instrumental rationalisation with the “means” orientation, as there is an aim embedded in the action of considering other forms of association: possible EU membership for Ukraine. The topos for this second argument is one of explanation, as the argument tries to explain why the action is legitimised.

Together, these two arguments lead to the claim that it is therefore legitimised that the MEPs state that it is now time to consider other forms of association for Ukraine.

4.2. Overview of results

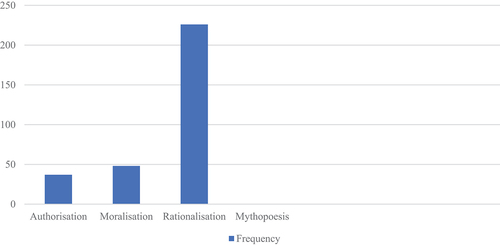

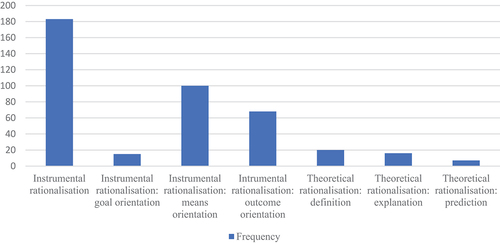

Following the example of coding given above, the following results have been collected from the total corpus. The total corpus of data can be found in Table . Table displays a detailed explication of the types of legitimations found in the texts. Graph further visualises the collection of data. The dominance of rationalisation legitimations clearly stands out. Graph further explicates the details of the dominant legitimation type (rationalisation legitimations).

Table 3. Corpus of data

Table 2. Types of legitimationFootnote7 and frequency found in conditionality legitimations

4.3. Discussion of results

The results highlight important aspects of the EU’s discourse towards Ukraine. When deconstructing the dominant legitimation category, rationalisation legitimation, we see that the means orientation was most frequently employed. This shows that the EU always tried to work towards a certain aim in its discourse. This means-orientation makes sense once the context is added: its discourse focuses on the implementation of the EU-Ukraine Action Plan, which is supposed to bring Ukraine closer towards the EU. However, as the detailed discussion of rationalisation legitimations will show below, the reason why the EU wanted to implement the Action Plan are even more interesting. This research shows that the EU cared mostly about justifying its own international standing and saw the Orange Revolution as a means to achieve this.

The moralisation legitimation, another frequently employed category, shows us that value systems like democracy were highly important for the EU in justifying its policy towards Ukraine. In particular, emphasis is placed on the fact that the implementation of the Action Plan only became possible after the Orange Revolution, when Ukraine’s government had become decidedly democratic. The conditionality aspect of the EU’s policy is hereby explained: democracy needed to be in place before substantive action from the EU’s side would be taken.

Perhaps most significantly, the moral evaluation and rationalisation legitimations show that the EU viewed the Orange Revolution in Ukraine as an opportunity with which it could test its ENP policy and legitimise itself as an actor capable of acting on the global stage. A more specific discussion of each legitimation category follows below.

4.3.1. Authorisation legitimations

An example of a personal authorisation legitimation can be found in Text 10.

“Before setting off to the region, Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner said: ‘I look forward to getting down to work with the new government to support Ukraine’s own ambitious programme of political and economic reforms. We have heard Ukraine’s calls for closer relations with the EU, and we are ready to answer, with an Action Plan designed to bring Ukraine and the EU much closer together’.”Footnote8

The action legitimised here is the EU having designed an Action Plan. This is legitimised by two arguments.

First, Ferrero-Waldner states that the EU has heard Ukraine’s calls for closer relations with the EU, and that the EU is ready to answer. This argumentation belongs to the authorisation category with a “personal authority” orientation, as the Ferrero-Waldner frames this action in a very personal manner: Ukraine has called, so we answer (by creating an Action Plan). This framing indicates a personal relationship between the two actors.

Second, the argument is legitimised by a goal: the Action Plan is designed to bring Ukraine and the EU much closer together. Therefore, this argument belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category, with the “goal” orientation.

Together, these arguments lead to the claim that the EU designing an Action Plan is legitimised. The topos of this argumentation is one of conditionality: Ukraine has shown an interest in better relations; thus the EU can act.

Text 16 contains an example of an impersonal authorisation legitimation.

“In the economic field, the focus of this afternoon’s discussions, the objectives of ENP are ambitious: enhanced preferential trade relations, increased financial and technical assistance, gradual participation in a number of EU policies and programmes and, the most novel and far-reaching feature of the ENP, a ‘stake’ in the EU’s internal market. This means gradual participation in our internal market through approximating legislation and gradual integration of transport, energy and telecommunication networks.”Footnote9

The action legitimised here is the EU giving ENP partner countries a stake in the EU’s internal market. The argument that is made to legitimise this action is the fact that this will happen, if partners will approximate legislation and gradually integrate transport, energy and telecommunication networks. The claim that is therefore made in this argumentation scheme is that the EU will give ENP countries a stake in the EU’s internal market. The topos of this argumentation is one of conditionality: if the ENP partner countries do x, then the EU will do y. The category of legitimation that this scheme belongs to is one of impersonal authorisation, as it originates from a policy framework and regulations.

This legitimation of EU ENP policy applies to Ukraine, since Ukraine is a participant of the ENP. Therefore, the legitimation EU ENP policy in this case also sheds light on how the EU views Ukraine.

4.3.2. Moralisation legitimations

Moralisation legitimations were the second most dominant type of legitimation employed by the EU. Interestingly, these were often combined with other types of legitimation. Let us start with an example from Text 1:

“Parliament urged all sides in Ukraine to accept the election results and called for a speedy transfer of power. It urged the new Ukrainian political leadership to consolidate the espousal of common European values and objectives by taking further steps to promote democracy. MEPs were concerned about the deep divisions within Ukraine and called on all political leaders to make efforts to heal those rifts. Threats of separatism were deemed unacceptable.”Footnote10

The action legitimised in this text is the urging by the MEPs to the new Ukrainian leadership to consolidate the espousal of common European values and objectives by taking further steps to promote democracy. The phrasing “urged” is noteworthy, since it implies that haste is needed. This is explained by asking why the action is needed: the MEPs are concerned about the deep divisions within Ukraine. This is one of the arguments used to legitimise this urging. This argument belongs to the moralisation category with the “abstraction” orientation, as it links the action to moral values of concern.

The second argument that is used to legitimise the urging of the MEPs is that threats of separatism were deemed unacceptable. This argument belongs to the moralisation category with the evaluation orientation, as an evaluative adjective (“unacceptable”) is used to denote the position of the MEPs.

Both arguments lead to the claim that the MEPs urging Ukraine to consolidate the espousal of common European values and objectives by taking further steps to promote democracy is legitimised. The topos that this argumentation belongs to is one of explanation, as the scheme explains why the action is legitimised.

A second action that is legitimised here is the MEPs calling on all political leaders to make efforts to heal those rifts. This is again legitimised by two actions.

First, MEPs are concerned about the deep divisions in Ukraine and second, threats of separatism were deemed unacceptable. These arguments are the same as the ones used to legitimise other actions and they therefore belong to the same categories, respectively those of moralisation with the “abstraction” and “evaluation” orientation. Both arguments lead to the claim that the MEPs calling on all political leaders to make efforts to heal those rifts is legitimised. The topos that this argumentation belongs to is one of explanation, as the scheme explains why the action is legitimised.

Text 2 also contains examples of a case where a moralisation legitimation was employed. One of these is the following:

“A new Action Plan negotiated with Ukraine was approved by the Commission and the Council last December. Now that democratic elections have taken place it will be possible to launch the implementation of that plan, as soon as the final procedural steps have been taken.”Footnote11

The action legitimised here is the implementation of the newly negotiated Action Plan. Two arguments legitimise this action.

First is the fact that democratic elections have now taken place in Ukraine. This argumentation scheme therefore has as its topos conditionality: now that Ukraine has had democratic elections, the EU can allow the implementation of the Action Plan. Since the EU references explicitly democratic elections, this legitimation refers to value systems, which makes it a moralisation legitimation with the “evaluation” orientation. As this argument also focuses on the outcome of a certain event, namely Ukraine having had democratic elections, this argument also belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category with the “outcome” orientation.

Second, the implementation of the Action Plan is legitimised by the condition that the final procedural steps have to have been taken first. This is an explicit reference to regulations, which makes this argument an authorisation legitimation with the “impersonal authority” orientation.

Both of these arguments lead to the claim that the implementation of the Action Plan is legitimised.

4.3.3. Rationalisation legitimations

Text 2 contains another interesting legitimation:

“On the eve of her visit, Benita Ferrero-Waldner said: ‘I congratulate President Yushchenko on his inauguration. Ukraine is a country of strategic importance for the EU, and the Presidential elections in Ukraine, with the events that surrounded them, have opened the way for a new beginning in the EU-Ukraine relationship.’”Footnote12

The action that is legitimised here is the EU opening up a new beginning in the EU-Ukraine relationship. Two arguments are used to legitimise this action.

The first argument states that Ukraine is a country of strategic importance to the EU. Therefore, the claim is, a new beginning in the EU-Ukraine relationship has opened up. The topos of this scheme is one of explanation, as it explains why a new beginning in EU-Ukraine relations has opened up. The category of legitimation that this scheme belongs to is a theoretical rationalisation with an explanation orientation, as it refers to a “fact of life” (Rheindorf & Wodak, Citation2018).

The second argument that is invoked to legitimise this action is the fact that presidential elections have taken place, “with the events that surrounded them”.Footnote13 “The events that surrounded them” are not explained by Ferrero-Waldner, but we know what is meant: the Orange Revolution. Therefore, this argument implies that the EU is willing to open up a new beginning in EU-Ukraine relations because the Orange Revolution has resulted in democratic elections taking place in Ukraine. The topos of this argumentation is therefore one of conditionality: if Ukraine has democratic elections, the EU is willing to open up a new beginning to the relationship. This is a moralisation legitimation with the “evaluation” orientation, as it refers to the value system of democracy, albeit implicit. Again, this argumentation belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category with the “outcome” orientation as well, since the effects of the outcome of the Orange Revolution are used in the argument.

A highly significant argumentation scheme can be found in Text 17. Early on in this text, Ferrero-Waldner uses a metaphor of a so-called “European Dream”Footnote14 in order to justify the EU acting in its neighbourhood and on a global scale. Of particular interest is the justification that Ferrero-Waldner employs in legitimising the EU’s role in the Orange Revolution. She specifically states the following:

“I believe that the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) played a significant role in the outcome of the Orange Revolution. Throughout the crisis, the EU showed exemplary coordination and coherence, and our message was clear – we wanted to offer Ukraine a closer relationship, but we could only do that if Ukraine shared our fundamental values. We needed Ukraine to demonstrate its respect for the rule of law and democratic principles.

To make it plain, we formally adopted the draft ENP Action Plan, but put its implementation on ice until the political situation was satisfactorily resolved. Yet we lost no opportunity to spell out the incentives on offer and to stress that we were ready to begin implementation as soon as possible.

That was the basis on which Presidents Kwasniewski and Adamkus and High Representative Solana negotiated. It was the ENP’s first test as the EU’s new political tool, and it passed with flying colours.”Footnote15

In this excerpt, one main claim is legitimised: the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy played a significant role in the outcome of the Orange Revolution. Five arguments are made here to legitimise this claim: first, the fact that the EU showed exemplary coordination and coherence throughout the crisis; second, the fact that the EU wanted to offer Ukraine a closer relationship, but could only do that if Ukraine shared its fundamental values; third, the fact that the EU formally adopted the draft ENP Action Plan but put its implementation on hold until the situation was satisfactorily resolved; fourth, the EU kept telling Ukraine about the incentives on offer; and fifth, the EU kept telling Ukraine that it was ready to begin implementation as soon as possible.

All five arguments lead to the claim that the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy played a significant role in the outcome of the Orange Revolution. The topos of this argumentation scheme is one of example: each argumentation is an example that backs up Ferrero-Waldner’s claim.

Each argument belongs to a specific category of legitimation. The first argument belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category with the “outcome” orientation, as the focus of the argument is on the effects of an outcome: the EU showed exemplary coordination and coherence throughout the crisis; therefore, the ENP played a significant role.

The second argument belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category with the “goal” orientation, as the EU specifically states that it wanted to offer Ukraine a closer relationship (therefore, the ENP played a significant role).

The third argument belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category with the “outcome” orientation, as the focus here is on the effect of the outcome of the action: the putting on hold of the Action Plan until the situation was satisfactorily resolved (therefore, the ENP played a significant role).

The fourth argument belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category with the “outcome” orientation, as the focus here is on the effect of the outcome of the action: the EU kept telling Ukraine about the incentives on offer (therefore, the ENP played a significant role).

The fifth argument belongs to the instrumental rationalisation category with the “outcome” orientation, as the focus here is on the effect of the outcome of the action: the EU kept telling Ukraine that it was ready to begin implementation as soon as possible (therefore, the ENP played a significant role).

The last part of the excerpt, in which Ferrero-Waldner mentions the ENP explicitly as a new political tool, has to be taken into account as well. The action legitimised here is the fact that the ENP passed the test as the EU’s new political tool. The argument that is made is that the EU’s draft Action Plan helped to solve the Orange Revolution satisfactory. The topos of this argumentation scheme is one of example, as the resolution of the Orange Revolution by the ENP draft Action Plan is used as an example of why the ENP passed the test. The category that this legitimation belongs to is again one of instrumental rationalisation with the “outcome” orientation.

Of interest here is the larger framing that is taking place in this text. Ferrero-Waldner frames the EU as being a decisive factor in solving the Orange Revolution by having been directly involved, using the draft ENP Action Plan to steer events to its liking. The reason that this framing is used, becomes clear by analysing the following excerpt:

“The ENP proved itself as a highly effective foreign policy tool which supports our long term goal of greater assertiveness and effectiveness on the global stage. I do not believe that ‘the EU contributed to the revolution simply by its attractiveness as a club that so many want to join’, as Mr Timothy Garton Ash has recently claimed. That would relegate us to a purely passive role and my point is that those days are gone.”Footnote16

Here, the action that is legitimised is the EU being an assertive actor on the global stage. The first argument that is made in order to legitimise this action is the fact that the ENP succeeded in Ukraine, leading to the claim that the ENP proved itself as an effective foreign policy tool that supports the EU’s claim of being an assertive actor on the global stage. The category that this legitimation belongs to is one of instrumental rationalisation with the “outcome” orientation.

The second argument that is made to support this claim is that Ferrero-Waldner does not believe what Mr. Timothy Garton Ash recently claimed, namely that the EU contributed to the revolution simply by its attractiveness as a club that so many want to join, since “that would relegate us to a purely passive role and my point is that those days are gone”.Footnote17 This argument is a moralisation legitimation with the “analogy” orientation, as Ferrero-Waldner relies on a contrasting force: she has previously claimed that the EU is effective (on the global stage) because its ENP Actions were effective in Ukraine; therefore, Ash’ statement is incorrect.

The displayed argumentation schemes found in Text 17 therefore illustrate the fact that the EU perceived the Orange Revolution in Ukraine as a test with which it could legitimise the use of the ENP, which in turn would legitimise the EU being assertive on the global stage. The Orange Revolution was therefore seen as an opportunity by the EU.

5. conclusion

This paper has shown that while legitimising its actions to Ukraine, the EU has focused on the justifying the implementation of the Action Plan. During those justifications, the EU most frequently made use of rationalisation legitimations which focus on the “means” orientation. The displayed argumentation schemes found in Text 17 illustrate the fact that the EU perceived the Orange Revolution in Ukraine as a test with which it could legitimise the use of the ENP, which in turn would legitimise the EU taking assertive action on the global stage. The Orange Revolution was therefore viewed as an opportunity for and by the EU.

Therefore, the conclusion of this research is that the analysis of legitimation strategies by the EU vis-à-vis Ukraine illustrates the fact that the EU was intent on spreading its normative values in its neighbourhood by testing out the European Neighbourhood Policy on Ukraine.

In a broader sense, this analysis can contribute to an understanding of the ambiguity displayed by the EU towards Ukraine noted by Hansen (Citation2006) This is especially relevant in the current context of EU-Ukraine relations in which Ukraine has been awarded candidacy status. Further research should determine whether this ambiguity is still present in the EU’s discourses and actions towards Ukraine, or whether the renewed Russian invasion is indeed the dealbreaker that the EU claims it to be. Future research should also determine of how actors like Ukraine and Russia interpreted the legitimations employed by the EU. This could increase our understanding of the views held by the elites of these countries, which, in turn could explain in more detail how the events of 2014 and 2022 unfolded. With the war in Ukraine ongoing, an understanding of these issues is of the utmost importance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. For influential contributions of these authors, see: Norman Fairclough, Discourse and Social Change (Polity Press: Citation1992); Teun A. Van Dijk, Discourse Studies—A Multidisciplinary Introduction (SAGE Publications Ltd, Citation2011); Ruth Wodak, Disorders of Discourse (London: Longman, Citation1996); and Michał Krzyżanowski, “Policy, policy communication and discursive shifts: Analysing EU policy discourses on climate change,” in: P. Cap and U. Okulska (eds) Analysing New Genres in Political Communication (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, Citation2013).

2. For an elaborate discussion on EU actorness, see Licínia Simão, “Unpacking the EU’s International Actorness: Debates, Theories and Concepts,” in: EU Global Actorness in a World of Contested Leadership: Policies, Instruments and Perceptions, ed. Maria Raquel Freire, Paula Duarte Lopes, Daniela Nascimento and Licínia Simão (Palgrave Macmillan: Citation2022): 13–32.

3. See, for example: Majid KhosraviNik, “Macro and micro legitimation in discourse on Iran’s nuclear programme: The case of Iranian national newspaper Kayhan,” Discourse & Society 26, no. 1 (2015); and Mariya Y. Omelicheva, “Authoritarian legitimation: assessing discourses of legitimacy in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan,” Central Asian Survey 35, no. 4 (2016).

4. For example, a Note from the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union to the Permanent Representatives Committee which contains draft “Council conclusions on Ukraine” (Citation6512/05) is only “partially accessible to the public” and specific reservations or introductions from member states are deleted from the document.

5. Based on: Rheindorf and Wodak (Citation2018), p. 123.

6. Press release on European Parliament vote on statement on Ukrainian elections, accessed August 29, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/dn_05_44.

7. Based on Wodak, “Chapter 1: Populism and Politics,” 6.

8. Press release on Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner’s visit to Ukraine, accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_05_186.

9. Speech by Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner: “Europe’s Neighbours—Towards Closer Integration”, accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_05_253.

10. Press release on European Parliament vote on statement on Ukrainian elections, accessed August 29, 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/dn_05_44.

11. Press release on Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner at the inauguration of new Ukrainian president Yushchenko, accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_05_81.

12. Press release on Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner at the inauguration of new Ukrainian president Yushchenko, accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_05_81.

13. Press release on Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner at the inauguration of new Ukrainian president Yushchenko, accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_05_81.

14. Speech by Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner: “The EU and Ukraine—What Lies Beyond the Horizon?” Accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_05_257.

15. Speech by Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner: “The EU and Ukraine—What Lies Beyond the Horizon?” Accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_05_257.

16. Speech by Commissioner Ferrero-Waldner: “The EU and Ukraine—What Lies Beyond the Horizon?” Accessed August 29, 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_05_257.

17. Ibid.

References

- 6512/05: Note from the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union to the Permanent Representatives Committee. Subject: Draft “Council conclusions on Ukraine”. 17 February. 2005.

- Aydin-Dügzit, S. (2014). Critical discourse analysis in analysing European Union foreign policy: Prospects and challenges. Cooperation and Conflict, 49(3), 354–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836713494999

- Brzozowski, A. Euractiv (Website). https://www.euractiv.com.

- Dijk, V., & Teun, A. (2011). Discourse Studies – a Multidisciplinary Introduction. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Ekström, M., & Eriksson, G. “Press conferences,” 342–354. In: The Routledge Handbook of Politics and Langauge, Eds. Ruth Wodak & Bernhard Forchtner. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

- Hansen, F. S. (2006, June). The EU and Ukraine: Rhetorical entrapment? European Security, 15(2), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662830600903561

- Karatnycky, A. (2005, March). Ukraine’s Orange Revolution. Foreign Affairs, 84(2).

- Kostagiannis, K. (2014). Hans Morgenthau and the tragedy of the nation-state. The International History Review, 36(3), 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.828639

- Krzyżanowski, M. (2013). Policy, policy communication and discursive shifts: Analysing EU policy discourses on climate change. In Piotr Cap & Urszula Okulska (Eds.), Analysing genres in political communication. Theory and practice (pp. 101–133). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Maresceau, M. (2004). EU enlargement and EU Common strategies on Russia and Ukraine. An ambiguous but yet unavoidable connection,” 181-219. In Christophe Hillion (Ed.), EU enlargement: A legal approach. Hart Publishing.

- Milliken, J. (1999). The study of discourse in International relations: A critique of research and Methods. European Journal of International Relations, 5(2), 225–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066199005002003

- Morgenthau, H. J. (1948). The new moral force of nationalistic universalism. In Knopf, A. (Eds.), Politics among nations: The struggle for power and peace (pp. 267–269).

- Parker, J. (2022). Joe Inwood and Steve Rosenberg. BBC News. website. https://www.bbc.com/news

- Popova, O., Prokopenko, A., & Yehorova, O. (2019). The concept of European integration in the EU-Ukraine perspective: Notional and interpretative aspects of language expression. On-Line Journal Modelling the New Europe, (29), 53–77. https://doi.org/10.24193/OJMNE.2019.29.03

- Reisigl, M. (2014). Argumentation analysis and the discourse-historical approach – a methodological framework. In Christopher Hart & Piotr Cap (Eds.), Contemporary critical discourse studies (pp. 67–96). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

- Reisigl, M. (2017, July). The discourse-historical approach.In In John Flowerdew & John. E Richardson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies (pp. 44–59). Routledge.

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2009). The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In Ruth Wodak & Michael Meyer (Eds.), Methods for critical discourse analysis (2nd revised ed., pp. 87–121). Sage.

- Rheindorf, M., & Wodak, R. (2018). Borders, fences, and limits – protecting Austria from refugees: Metadiscursive negotiation of meaning in the Current refugee crisis. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 16(1–2), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1302032

- Roth, M. (2007, December). EU-Ukraine relations after the Orange Revolution: The role of the new member states. Perspectives on European Politics & Society, 8(4), 505–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705850701641023

- Semeniy, O. (2007). Ukraine’s European policy as an alternative choice – achievements, mistakes and prospects. In Stephen Velychenko (Ed.), Ukraine, the EU and Russia – history, culture and international relations (pp. 123–137). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Simão, L. (2022). Unpacking the EU’s International Actorness: Debates, Theories and concepts. In Maria Raquel Freire & Paula Duarte Lopes (Eds.), EU global actorness in a world of contested leadership: Policies, instruments and perceptions (pp. 13–32). Daniela Nascimento and Licínia Simão.

- Solonenko, I. (2007). The EU’s impact on democratic transformation in Ukraine. In Stephen Velychenko (Ed.), Ukraine, the EU and Russia – history, culture and international relations (pp. 138–150). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wodak, R. (1996). Disorders of discourse. Longman.

- Wodak, R. (2001). What CDA is about – a summary of its history, important concepts and its developments. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 1–21). Sage.

- Wodak, R. (2015). Chapter 1: Populism and Politics: Transgressing norms and taboos eds. Mila Steele, Jamer Piper . In The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean (pp. 1–21). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Zasenko, O. E. Encyclopædia Britannica (Website). https://www.britannica.com.