?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The objective of this study is to determine the overall effectiveness of omnichannel warehouses, with a focus on the fashion industry, which has demonstrated resilience during the pandemic by utilizing both offline and online sales techniques. This study essentially develops a generic technique for evaluating omnichannel warehouse productivity based on the design of Karim et al., adjusting some of its indicators to suit Indonesia’s medium-sized fashion industry. The observational study’s results indicate that the workforce and space categories’ Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for the fashion sector are still deficient. Based on discussions with various management entities, it is suggested that KPIs be extended into four categories by including measures related to space and information systems. Moreover, four indicators—product receiving, identification, and picking (offline) in the labor category, and transportation utilization in the space category—are highlighted using the Traffic Light System (TLS) method as the highest priority areas for improvement. The fundamental reasons for these issues are found through fishbone diagram analysis, and they include a deficient fleet of vehicles, imprecise transportation plans, inaccurate demand projections, insufficient employee training about new products, and inadequate mechanisms for communication between the sales, warehouse, and vendors. The limitation of this study is that it solely looked at the fashion industry’s productivity. It is recommended that future studies use omnichannel principles across many businesses to measure other industry variables like time, cost, and quality.

Impact statement

The coronavirus disease (Covid-19) pandemic has caused significant changes in several industries, including the fashion sector. New habits are entering the market as a result of people’s trends changing quickly and dynamically. One such habit is the move to online apparel buying, which provides a range of practical features at reasonably low costs. Since many of them would rather spend their time doing other things than shopping in real stores, the younger generation prefers to use internet programs to make apparel purchases. Fashion has adopted a new way of life as a result of the pandemic. This study essentially uses the research of Karim et al., who created a generic technique to gauge warehouse productivity and modified a few variables to make them relevant to the fashion sector in Indonesia. The measurement results indicate that there is a need to enhance the following areas: employee awareness of new items, accuracy of demand projections, appropriate transport vehicles, and reliable, timely transportation planning.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

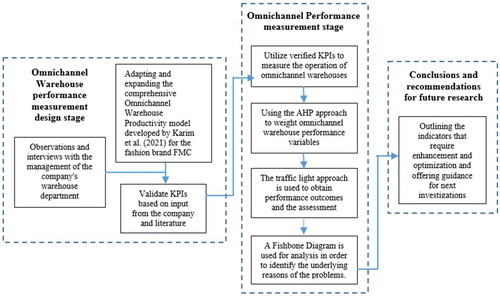

The global halal industry market is not only experiencing growth in the food and beverage sector but also extends to the clothing sector, which is fundamentally a basic human need. The global Muslim population’s expenditure on clothing amounts to USD 295 billion. Despite the negative impact of the pandemic on growth, this figure is projected to continue rising to $311 billion in 2024 and is estimated to reach USD 375 billion in 2025, making it the second-highest sector after the halal food and beverage industry (State of The Global Islamic Economy Report, Citation2022). According to Cognitive Market Research, the global Islamic clothing market’s size is expected to grow at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 5.50% from 2023 to 2030 (Pradana et al., Citation2023). The growth of the Islamic clothing market can be attributed to the global increase in the Muslim population, rising disposable income, and an enhanced consumer awareness of Islamic fashion. The projection of global Muslim expenditure on clothing, compared to all halal products and the lifestyle sector, has increased from 1% in 2019–2020 to 6.3% in 2024–2025 () (State of The Global Islamic Economy Report, Citation2022).

Figure 1. Projection of global Muslim expenditure on clothing compared to all halal products and the lifestyle sector.

Source: State of The Global Islamic Economy Report (Citation2022).

Strong indicators of fashion demand volume and major markets can be obtained by measuring trade flows. In 2020, countries in the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) exported fashion products worth US$83 billion. With a trade surplus of US$56 billion, OIC countries demonstrated a leadership position in the global fashion trade, comprising 16% of global exports ().

Table 1. Top exporters to OIC and top fashion importers in OIC.

In , Indonesia is ranked 9th globally as the highest exporter to OIC countries and holds the 6th position as an importer from OIC countries. The fashion sector contributes 3.5% to the total non-oil and gas export value of Indonesia. Domestically, the Muslim fashion industry shows significant development, growing by 18.2% in 2021 with a total consumption reaching IDR 300 trillion. Indonesia continues its efforts to become a global center for Muslim fashion (Indriya et al., Citation2021). The growth of the Indonesian fashion industry is evident with a total of 1,107,955 fashion companies, comprising 10% large enterprises, 20% medium-sized businesses, and 70% small businesses (Kusumawati et al., Citation2019).

However, in this era of digitalization, there has been a significant shift in consumer shopping patterns. Consumers who used to shop directly in stores are now transitioning to online shopping (Redjeki & Affandi, Citation2021; Wardana & Darma, Citation2020). The increasing trend of online shopping has led to a higher demand for warehousing and logistics services in Indonesia (Chen & Chi, Citation2021). This presents both opportunities and challenges for warehousing in Indonesia to become more cost and time-efficient (Hanum et al., Citation2020). The relationship between products and storage location poses a challenge in optimizing order fulfillment for both individual consumers and retail store networks (Alishah et al., Citation2017).

Several factors contribute to the inefficiency of warehouse management in Indonesia, including high warehouse rental costs and underutilized warehouse capacity (Demirbas & Ertem, Citation2021; Mahroof, Citation2019). Inefficiency is also caused by warehouse leasing typically being annual with only 10–20% of the total building capacity being utilized (Hu, Citation2022). To address increasing demand and warehouse inefficiencies, various innovations have been implemented, one of which is omnichannel (Choi, Citation2014; Do Vale et al., Citation2021).

This research is a case study of a medium-scale Muslim fashion company (hereafter referred to as FMC) in Indonesia, operating in 120 locations and supported by 1068 agents and 200,000 active members. FMC expanded its distribution channels to boost sales, significantly impacting customer satisfaction and loyalty. In 2019, FMC became one of the Muslim fashion companies implementing omnichannel retail, with two daily ordering channels: direct marketing through the app and online services, and indirect ordering through the company’s marketing department. However, FMC faced several issues, including fulfillment problems related to product demand from both corporate and end-consumers. indicates unmet consumer demand targets in 2020, revealing that FMC’s omnichannel warehouse was unable to fulfill 100% of consumer orders. The tolerance for consumer order fulfillment targets was set at 90%, but in reality, most fulfillments fell below this tolerance level.

Table 2. The company’s omnichannel warehouse target in fulfilling customer orders in 2020.

shows order fulfillment ranging from a minimum of 40% to a maximum of 90%. Based on interviews and observations with FMC management, the suboptimal fulfillment of consumer product orders is attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a significant reduction in the workforce and misplaced product locations (average of 11.15%, where FMC’s standard is 3%). Each product has been assigned a storage place and location number, but several factors contribute to improper product placement. These include employee negligence, where products of the same color but different types are mixed (50% of cases). Another cause is massive brand discount days, involving over 23,000 transactions to be completed in three days, resulting in high work volumes making employees less attentive or prone to errors (30% of cases), such as misplacing location numbers (10% of cases) and inventory discrepancies (10% of cases). Additionally, unusual storage layouts or arrangements make it challenging for employees to determine the correct storage location. As a result, during inventory checks, many products are not in their designated storage locations.

The aim of this research is to find the overall performance of omnichannel warehouses, particularly in the Muslim fashion industry (FMC), compare the current measurements of omnichannel warehouse performance with proposed improvements, and identify the root causes of the failure to achieve performance targets significantly below the company’s standards. Essentially, this research develops omnichannel warehouse performance metrics based on overall productivity from Karim et al. (Citation2021), with the indicators then tailored to the context of a Muslim fashion company.

2. Theoretical literature review

2.1. Omnichannel warehouse

Multichannel warehousing is a relatively new concept in logistics and supply chains (Buldeo Rai et al., Citation2019; Heizer et al., Citation2020). According to Larke et al. (Citation2018), compared to other types of distribution warehouses, omnichannel warehouses must effectively integrate various flows, especially diverse orders, and material flows for restocking both in-store and online customers. Cai and Lo (Citation2020) and Luo et al. (Citation2019) reveal that omnichannel management handles multi-channel retail, providing products or services to consumers through various online and offline channels. Furthermore, a synergistic management of various channels and customer touchpoints is required to optimize customer experience across all channels and multichannel performance (Ding & Kaminsky, Citation2020; Shi et al., Citation2020).

Online orders come from individual consumers with small quantities but increasing over time, while offline orders have specific times and involve larger quantities. Both have distinct characteristics, and their fulfillment processes differ (Eriksson et al., Citation2019). The offline and online order fulfillment processes at FMC are handled differently in terms of storage, and the daily responsibilities assigned to staff members are split into two groups based on the type of order they are fulfilling. Consequently, FMC’s omnichannel warehouse presents several difficulties. The first obstacle is using digital platforms, e-commerce, or the company’s own app to meet client demands or orders. The second obstacle facing FMC is meeting client expectations via indirect channels, business-to-business clients, and joint venture partners that place large and scheduled purchases. This makes omnichannel warehouse management necessary to maximize all of FMC’s operational activities, such as cutting lead times, cutting expenses associated with material handling, maximizing space utilization, raising overall throughput, improving security, cutting travel times and distances, controlling traffic, cutting down on administrative work, and increasing flexibility.

Moreover, insufficient product knowledge frequently presents a challenge for warehouse operations (de Borba et al., Citation2020). FMC employees regularly make mistakes as a result of their lack of discipline regarding product storage areas and ignorance of new things. For example, when customers place orders, staff workers may select the incorrect product category, which may result in the item not being returned to the designated storage area. Workers who are not assigned to warehousing duties might also pick up goods for online sales. This shows that FMC’s omnichannel warehouse organization and standard operating procedures are not being adhered to regularly.

2.2. Performance measurement of omnichannel warehouse

The main difference between an omnichannel warehouse and other warehouse types lies in the warehouse configuration aspect. Warehouse operations generally include receiving, shipping, storage, picking, sorting, packing, and dispatching (Alawneh & Zhang, Citation2018). Meanwhile, warehouse design and resources encompass layout, storage equipment, handling equipment, information systems, human resources, and related activities (Slack & Brandon-Jones, Citation2018). Kembro and Norrman (Citation2019) and Kembro et al. (Citation2018) investigated warehouse configurations in different contexts as companies adapt to omnichannel, representing a combination of warehouse operations, design aspects, and resources. Kembro and Norrman (Citation2019) then analyzed five main dimensions of omnichannel warehousing: network and handling center types, automation and integration, product storage zones, product picking processes, and methods used in product picking. Various design and resource aspects must be considered to manage operations effectively and efficiently. Typically, design aspects, such as layout and automation are challenging to change and require significant time and investment (Lou et al., Citation2019). Essential resources in the FMC warehouse include equipment, space, information systems, and labor.

Furthermore, Kembro and Norrman (Citation2019) outline challenges in omnichannel warehousing. First of all, consumers ordering online anticipate faster turnaround times in the warehouse due to their shorter wait periods from order to delivery. To stay competitive, FMC wants to lower warehouse expenses by shortening wait times. Second, there is a greater volume of goods coming in and going out, and different types of orders for online and retail clients need to be coordinated and controlled. To increase customer satisfaction and loyalty, FMC must improve the coordination and administration of its warehouse. Last but not least, warehouse space is a major limitation that calls for a long-term balance between capacity and demand. To optimize production and optimize the movement of items into and out of the company, FMC needs additional space.

Several options in omnichannel warehousing include integrating or separating physical picking zones, processes, and resources for in-store restocking and online orders; picking methods (e.g. batch picking vs. single picking); decisions on when and how orders are sorted and packed; and the level of automation. All these configuration examples are highlighted as crucial in omnichannel warehousing He et al. (Citation2020). According to Kembro and Norrman (Citation2019), efficient storage in omnichannel warehousing often requires separate storage locations for each product and size, meaning every product in the omnichannel warehouse has a designated storage location. This minimizes order handling time since each product has a specific location (Millstein et al., Citation2022). Therefore, it can be concluded that the components of FMC’s omnichannel warehouse arrangement generally match the idea that has been discussed. These configuration aspects have been partially implemented in FMC for resources, warehouse design, and operational operations. However, limitations like inconsistencies in layout configurations and storage zones, as well as problems with reception and storage integration, make the implementation subpar. Positively, FMC can fulfill orders based on demand because the distribution and shipping procedures are already at their best.

3. Research method

Certain orders or requests cannot be fulfilled due to poor order fulfillment timeframes caused by the subpar storage methods used in FMC’s warehouse. First management interviews indicate that FMC loses 5% of its value or billions of rupiahs. FMC decided to review its omnichannel warehouse performance metrics in light of this loss. In 2019, the company performed performance measurements only once a year, which was deemed to be subpar. Furthermore, the shift from a traditional warehouse to an omnichannel warehouse creates additional difficulties in maintaining customer satisfaction and improving business performance, which enables the enterprise to flourish and compete. The need to measure warehouse performance indicators is crucial for managers to identify improvement areas and establish a foundation for corrective actions (Kusrini et al., Citation2018). With the advancements in the e-commerce world, FMC is seeking opportunities to enhance the productivity and accuracy of their warehouse to meet the demands of various Stock Keeping Units (SKU) and same-day fashion product delivery requirements for customers.

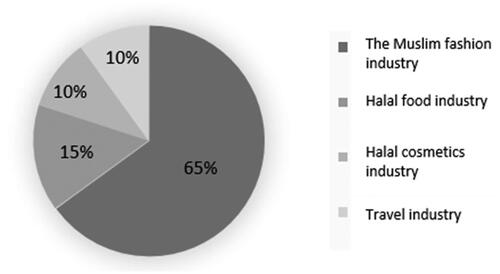

The steps on how this research is conducted can be seen in .

In , the research stages can be observed.

Initial research phase where the researcher conducts a literature study on measuring Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in omnichannel warehouses. The model to be developed is a general omnichannel warehouse model from Karim et al. (Citation2021), adjusted for a Muslim fashion company. These KPIs are essentially performance indicators compared to set targets or expected values (Kurniawan & Pratiwi, Citation2020).

Designing the omnichannel warehouse performance measurement using processed KPIs with the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) method, including:

Interviews with FMC, namely warehouse managers and supervisors, regarding the formulation of omnichannel warehouse KPIs.

Identification of KPIs covering labor productivity, space utilization, information systems, and warehouse equipment in the areas of receiving, identification, picking, and delivery.

Validation of KPIs together with FMC to ensure that the KPI indicators align with the needs.

Performance measurement phase, including:

Collection of actual and target data from FMC through questionnaires.

Weighting using the AHP method to determine which KPIs need improvement by FMC, those that are below standard, opening the way for future improvements (Qurtubi et al., Citation2022).

Implementation of a performance assessment system using the traffic light method.

Fishbone Diagram analysis to identify the root causes of issues.

Conclusion and recommendations for improving FMC’s performance and suggestions for future research.

4. Results and discussion

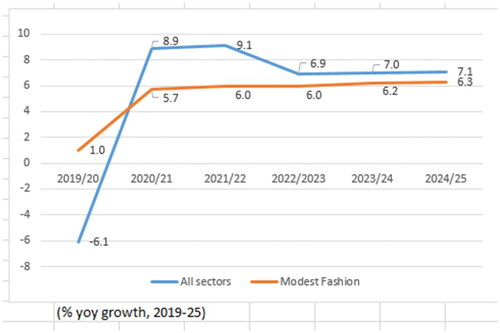

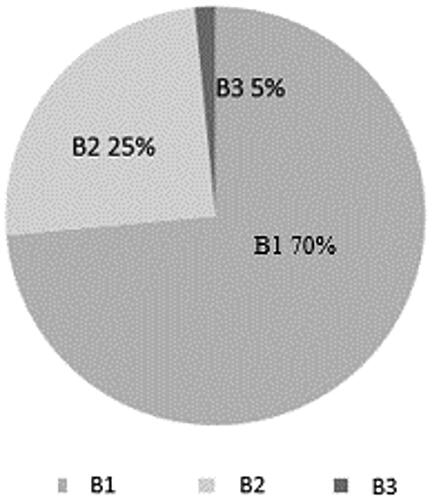

FMC’s business is split into four categories: tour and travel, cosmetics, halal cuisine, and fashion. According to , which shows the revenue from the four industries that FMC operates in, the fashion industry brings in the most money (65%), followed by halal food (15%), halal cosmetics (10%), and travel (10%). Additionally, the FMC omnichannel warehouse carries three Muslim fashion brands: B1, B2, and B3. shows the product composition of the FMC omnichannel warehouse.

Figure 3. Revenue percentage of the four industries in the FMC in 2019–2020.

Source: Unpublished Warehouse Inventory Records (Citation2021).

The distribution of products in the FMC warehouse according to brands is shown in . Brand B1 accounts for 70% of the distribution, brand B2 for 25%, and brand B3 for 5%. The following categories are additionally used by these fashion firms to group their products: dresses, scarves, abayas, tunics, accessories, and men’s clothes. Using Microsoft AX technology, every product in the FMC omnichannel warehouse is computerized and tracked in the warehouse management system.

Figure 4. Product distribution in the omnichannel warehouse by brand.

Source: Unpublished Warehouse Inventory Records (Citation2021).

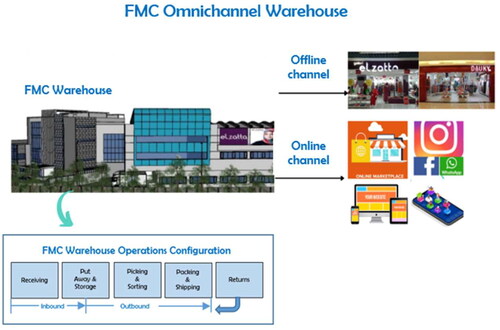

In addition, shows how FMC offers omnichannel retail, allowing customers to shop via a variety of platforms including social media, marketplaces, 200 physical stores located throughout Indonesia, and a specialized app. This illustrates how the organization has integrated all of its sales channels. From its beginnings as a raw material, semi-finished, and finished goods warehouse, the company’s warehouse function has changed throughout time. The company’s warehouse function, however, is reduced to a finished goods warehouse once vendors handle production tasks. Receiving, storing and warehousing, picking and sorting, packing and delivery, as well as returns, are all done within an omnichannel warehouse.

According to , FMC offers several direct and indirect ordering channels, such as:

Application: For all three brands—B1, B2, and B3—direct downloads from the app store or play store are possible. This app makes it very convenient for customers to browse products available in all Indonesian stores, choose delivery choices, finish purchases using easy payment ways, and get in touch with FMC customer service.

The Website: Website comprises features that facilitate customer transactions, provide an overview of all products, provide an overview of the company, and showcase FMC’s activities.

E-commerce: This allows clients to buy products online. Online merchants including Shopee, Tokopedia, Blibli.com, Zalora, Lazada, and Evermos are among the ones with whom FMC has partnered.

Social Media: All three FMC brands are represented on sites like Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter. FMC uses social media to market each of its products digitally, and it may also be used for user interactions and transactions.

Physical Stores: 200 physical stores are dispersed across Indonesia. Customers from different regions can transact with ease based on where they are thanks to this channel.

By creating an omnichannel warehouse or revamping its fashion warehouse, FMC enhanced its supply chain management in 2019. This was carried out to improve customer order fulfillment services. The shift resulted in FMC having to make operational adjustments to serve two distinct channels: the offline channel, which serves business customers and company stores with scheduled, high-volume orders, and the online channel, which serves a variety of end consumers with small order quantities. This aligns with Millstein et al. (Citation2022) assertion that an omnichannel warehouse differs from a regular warehouse, combining various types of flows, especially significantly different orders, including large and planned orders for stocking physical stores with high volumes and online orders with high variability in small quantities. The integration of resource design and warehouse operating activities is part of the FMC omnichannel warehouse. Handling customer returns of products is one of the operational operations, along with product reception, identification, selection, picking, packaging, and delivery ().

Based on , there are five main activities in the FMC omnichannel warehouse:

Product Receiving: Receiving goods that have been ordered from suppliers is part of this incoming activity. FMC receives items on a five-day basis, with an average of 20,000 products each day for three brands (B1, B2, and B3). Three employees handle product reception, order and product quantity adjustments, quality inspections, and product categorization according to brand, category, color, and size during the receiving process.

Product Identification (Putaway and Storage): This procedure comes before the goods is put in storage after receipt. Labeling, SKU checks, and location confirmation are all included. Products are placed in their proper places after being arranged according to brand, category, name, size, and color. FMC employs a tagging system to manage the location of product storage, especially for online channels, so that physical products and quantities on the online system match.

Picking and Sorting: Online and offline picking are also included in this important omnichannel warehousing procedure. While offline picking is focused on replenishing retailers all over Indonesia, online picking serves a variety of distribution channels and platforms.

Packing and Shipping: While offline packing is bulk storage in boxes or bags bearing the store’s name, online packing requires packaging each individual client. Every day at 4:00 pm, orders placed between 8:00 am and 2:00 pm WIB are shipped, both online and offline. Onward orders are dispatched the following day.

Returns: There are two types of returns: those from customers purchasing through online and offline channels. Integrated storage, according to Kembro and Norrman (Citation2019), facilitates quicker product retrieval, packing, and shipping. In omnichannel warehouses, configuration plays a crucial role, influenced by RFID implementation, storage system structure, mechanization level, workflow, including storage assignment policies and order accumulation, and resources, such as space capacity and workforce, as described by Kembro and Norrman (Citation2019).

4.1. Performance measurement of omnichannel warehouse with KPIs

Laosirihongthong et al. (Citation2018) explain that warehouses play a crucial connecting role in the supply chain, impacting costs, and have become complex entities to manage. Hence, it is important to investigate how their performance is continuously measured. Performance evaluation has been considered from various perspectives (Prabhuram et al., Citation2020), including warehouse design and operations. Improving warehouse operations, especially delay operations and the relationship between operational policies and performance, highlights characteristics—namely inclusivity, universality, measurability, and consistency—that make the performance measurement system effective (Hu et al., Citation2022). According to Kleinsmith et al. (Citation2018), Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are a measurement method referring to performance aspects significantly impacting a company’s success. KPIs are a core tool for measuring a company’s performance in specific areas, both in the present and the past (Braglia et al., Citation2021; Lorenzo-Romero et al., Citation2020). KPIs can depict how well a company’s performance aligns with expected targets or goals.

Here are the omnichannel warehouse KPIs based on the general productivity measurement model by Karim et al. (Citation2021), which has been developed and adapted for FMC ().

Table 3. KPIs for the FMC’s omnichannel warehouse.

displays the essential performance measures for warehousing, including labor, equipment, space, and information systems, along with the corresponding calculations and explanations, to quantify productivity. The FMC management and these metrics have had a lengthy discussion (). FMC may evaluate and incentivize the productivity of its workers by utilizing precise productivity performance metrics and integrating cutting-edge ideas and technology.

Table 4. Respondents for performance weighting questionnaire completion.

4.2. The weighting of omnichannel warehouse’s KPIs

This study uses the Analytical Hierarchy execute (AHP) approach for weighting, and AHP expert choice version 11 software is used to execute the calculations. FMC management, who are chosen based on their expertise and competence, length of service (7–15 years), and position as department warehouse managers, determine the weights for each category and performance indicator ().

The weighting results for each KPI can be seen in the following table.

demonstrates the importance of warehouse management systems in omnichannel warehousing by showing that the information system has the highest weight, totaling 0.325. Additionally, space, which has a weight of 0.265, represents FMC’s continuous attempts to maximize the use of warehouse space, with an emphasis on storage management, which is nevertheless beset by several difficulties. With a weight of 0.241, workforce factors come next, demonstrating their critical importance in reaching warehouse objectives. Before starting work, employees are given regular instructions, particularly when they are working on important company projects involving the warehouse. Finally, the weight of the equipment is 0.169, indicating that it has to be evaluated or its productivity improved for the workforce to be able to use it to its full potential.

Table 5. Weighting for each KPI of the company’s omnichannel warehouse.

4.3. Traffic light system of KPI

The traffic light system is closely related to the assessment system, serving as an indicator of whether KPI scores require improvement or not (Basumerda et al., Citation2019; Nathania & Desrianty, Citation2023). Indicators in the traffic light system are represented by various colors:

Green: The KPI has been achieved.

Yellow: The KPI is nearly achieved.

Red: The KPI needs immediate improvement as it is far from the target.

With four KPIs in the red category, six in the yellow category, and seven in the green category, shows the traffic light system in aggregate or comprehensive calculations.

Table 6. Result of traffic light system aggregation for the KPIs in the company’s omnichannel warehouse.

Three measurement outcomes are noted in :

Product receiving productivity, product identification productivity, offline channel product picking productivity in the workforce category, and transportation utilization productivity in the space category are examples of KPI indicators that fall into the red category if their gap value is >45% when compared to the target.

KPI indicators in the yellow category, which need attention to guarantee ongoing optimization, are nearly at the target with a gap value of <45%. Product placement area, building utilization, and product identification productivity fall under the space category; product receiving productivity, shipping productivity, and building utilization fall under the equipment category.

KPI indicators that are in the good category already—that is, they meet or surpass the target—and need to be maintained for sustainability. These indicators are designated as green. These include product turnover, time spent with products in the warehouse, online product picking productivity, workforce productivity, shipping productivity in the workforce category, and warehouse information management system in the information system category.

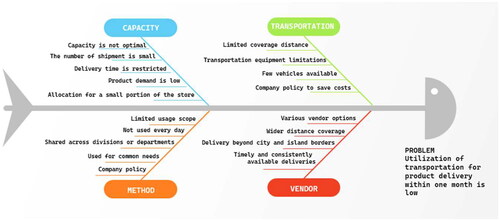

demonstrates that four KPIs fall into the red category, meaning that they urgently require improvement. One of these KPIs, transportation utilization, is in the space category, while the other three, product receiving productivity, product identification productivity, and offline channel product picking productivity, are related to the labor. The fishbone diagram that follows will provide further information on the underlying causes of problems with each KPI.

4.4. Fishbone diagram for red-labeled KPIs

The fishbone diagram is a tool for identifying various detailed causes and effects of a problem (Coccia, Citation2018; Jayswal et al., Citation2011). The following is a fishbone diagram for Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) categorized as red based on the traffic light method ().

Figure 6. Overview of FMC fashion omnichannel warehouse activities.

Source: The author’s analysis (2021).

Figure 7. Fishbone diagram for issues in the product receiving section of the omnichannel warehouse of the company (2021).

Source: Author’s analysis (2021).

Figure 8. Fishbone diagram for issues in the product identification section by warehouse workforce in the company’s omnichannel (2021).

Source: Author’s analysis (2021).

Figure 9. Fishbone diagram for issues in the offline order picking section of the company’s omnichannel warehouse (2021).

Source: Author’s analysis (2021).

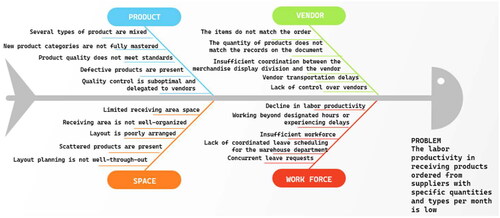

Low worker productivity in receiving monthly orders of precise types and quantities of products from suppliers is one of the problems shown in . Among the reasons are:

Because several employees took leave on the same day, worker capacity to manage the direct delivery of ordered products for processing during reception is not at its best.

The introduction of new products, for which the workforce’s proficiency in recognizing and handling them is inadequate.

Vendor errors are caused by the inadequate application of FMC quality control procedures, and they include things like differences between ordered and received items and the existence of defective products.

A backlog of work results from the product receiving area’s limited size, which disturbs product arrangement throughout the reception process.

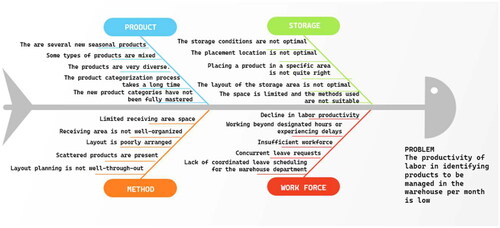

The problem shown in is the low productivity of the staff in determining which products need to be managed each month at the warehouse. Among the reasons are:

Employee data entry problems that call for additional verification.

Improper product organization and layout in storage.

Specialty or new products demand extra setup since they have to figure out where to put the stock storage unit and where to move the old one.

It is necessary to assess the product arrangement method used in the identifying process.

Based on monthly client orders, illustrates the challenges related to low staff productivity for offline order picking. This is brought about, among other things, by:

A subpar product was chosen to fill orders. In addition, long processing delays are caused by a labor scarcity.

FMC’s imprecise demand forecasting, which is based on basic techniques and gut feeling. For the marketing division’s large-scale initiatives, in particular, accurate forecasting techniques are essential to preventing overstock.

Inadequate communication between sales, the warehouse, and vendors results in inadequate management of storage space, particularly with regard to product classification, arrangement, and storage strategies.

Employees struggle with product categorization and understanding, which makes order choosing difficult.

The workforce is not routinely informed about standardized methods.

Inadequate upkeep of some functioning warehouse support equipment, which results in the loss and malfunction of specific tools.

Insufficient instruction on the warehouse information system to make tasks easier. The warehouse information system is essential for managing and controlling all aspects of warehouse operations, including receiving, storing, and shipping. Its application can lower expenses and increase operational efficiency.

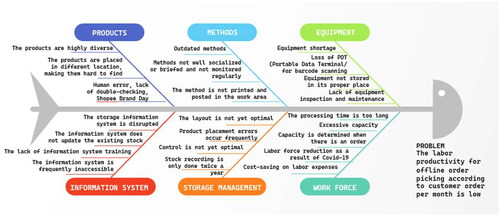

The problem with is that there is still a low use of transportation for product delivery within a month. This is caused, among other things:

Figure 10. Fishbone diagram for problems in the transport utilization section in the company’s omnichannel warehouse (2021).

Source: Author’s analysis (2021).

There aren’t enough transport vehicles to meet the needs of supply chain management in the warehouse due to their limited availability.

The current capacity is subpar since there are few retailers in need of product replenishment and the necessary supplies are only needed in certain areas with minimal transportation needs.

The business uses transportation providers to make it easier to deliver things outside of the island and even outside of the city. The company’s transportation utilization schedule is likewise constrained to accommodate operating requirements in other areas.

4.5. Comparison between current and proposed key performance indicators

The comparison between current and proposed omnichannel warehouse productivity measurements can be observed in . The current measurements comprise only two categories: labor and space, consisting of 7 KPIs. Meanwhile, the proposed measurements encompass four categories: labor, equipment, space, and information systems, comprising 16 KPIs, expanding on the omnichannel warehouse model by Karim et al. (Citation2021) in general.

The categories that need to be measured in the current omnichannel warehouse performance measurements are incomplete. It also depends on managers’ qualitative evaluations. FMC uses a qualitative assessment process that incorporates warehouse managers’ perspectives. Moreover, worker absenteeism serves as an example of how performance measurement is centered on workforce evaluation. In addition, the organization has created seven KPIs that fall within the labor and space categories ().

Table 7. Current performance measurement of omnichannel warehouse FMC.

shows that the warehouse has two performance measurement categories with seven KPIs each: labor and space. To calculate workforce productivity in warehouse operations—which include receiving, picking, and product management procedures—as well as the quantity of workplace accidents and damaged products in the warehouse, labor-related KPIs are measured. Measurements are made in relation to space to evaluate warehouse capacity and stocktaking procedures, which include tallying stored products before transportation or sale and detecting inaccuracies in product location.

According to the results of the warehouse performance measurement using the seven KPIs and based on interviews, the worst performance is linked to product location mistakes, meaning that certain things are not kept in the places where they are supposed to be kept. January and July are the other two times a year when stocktaking is done; for better accuracy, it is advised to do stocktaking every three months or even at the end of each month. One indicator of good performance in the warehouse is the lack of serious and mild workplace accidents.

In the proposal for omnichannel warehouse performance measurement, a comprehensive set of categories is measured using KPI calculation methods, AHP weighting, analysis using a traffic light system, and problem identification through fishbone analysis (Bressolles & Lang, Citation2019). compares the current omnichannel warehouse performance with the proposed performance measurement for the company.

Table 8. Comparison between current warehouse performance and proposed omnichannel warehouse performance for the company.

shows that the suggested omnichannel warehouse performance evaluation is more explicit, thorough, and includes more precise calculations; nonetheless, FMC’s staff will require specialized training to put it into practice.

4.6. Theoretical and practical contributions and their implications on policy implementation

This study’s theoretical contribution is the application of omnichannel warehouse measurement to labor, equipment, space, and information system productivity, particularly in the fashion industry—a field in which, to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, not much research has been done. This study’s practical contribution is to give businesses useful information about which Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) require quick improvement to continuously satisfy client demands for quantity and quality.

Additionally, this research has consequences for how policies are implemented, especially in the context of Indonesia’s fashion industry. From January to May 2022, the fashion sector in Indonesia had an export value of 2.85 billion US dollars (IDR 43.38 trillion), up 39% from the previous year’s 2.04 billion US dollars (IDR 31.05 trillion). Additionally, the fashion sub-sector, which contributes a significant 61.5% of Indonesia’s exports from the creative economy, remains a pillar of the country’s exports due to its track record of advancing economic development and overcoming obstacles brought on by the epidemic (Surodjo et al., Citation2022).

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

The warehouse of the fashion firm FMC, which served as the research’s case study, presently uses seven Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to assess its warehouse performance based on worker and space productivity. Based on the overall approach of Karim et al. (Citation2021), this is considered poor because two more categories—information system and equipment productivity—are not being measured. To be more thorough and maximize customer happiness, it is therefore suggested to improve the omnichannel warehouse performance measurement model of FMC into four areas, for a total of 16 KPIs.

Based on the study’s proposed approach for measuring FMC’s omnichannel warehouse performance, four key performance indicators (KPIs) were identified as high priority for improvement and placed in the red category. Product picking (offline channel), product identification, and product receiving productivity are the four KPIs in the workforce category; transportation utilization productivity is the KPI in the space category. The fishbone diagram analysis identified the following as the primary causes of the subpar omnichannel warehouse performance, which was substantially below the company’s targets: storage management, with only twice a year’s worth of inventory checks; poor communication between sales, the warehouse, and vendors; employee ignorance of new products; inaccurate demand forecasting by the company; and insufficient fleet and transportation scheduling.

These issues have led to recommendations for FMC that include: improving vendor, sales, and warehouse coordination, particularly during product orders; educating warehouse staff about new products and conducting inventories at least every three months to address storage location issues; putting accurate forecasting techniques into place to prevent overstock, particularly for large marketing division programs; and measuring omnichannel warehouse performance twice a year to improve the company’s competitiveness.

The creation of a general omnichannel warehouse assessment model from Karim et al. (Citation2021) with a narrow focus on productivity aspects and its application to a medium-sized Indonesian fashion company constitutes the research’s limitation. It is advised that measurements be extended to additional dimensions, such as time, cost, and quality, and that they be used for different kinds of businesses that are using omnichannel principles in future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vita Sarasi

Vita Sarasi joined the Faculty of Economics as a lecturer in the Management and Business Study Program, after completing her PhD program. Her areas of expertise include quantitative management approaches and operations. ‘Introduction to Systems Thinking and System Dynamics’ and ‘Excellent Project Management: On Time, On Budget, On Quality’ are two of the author’s textbooks. Among her works is the monograph ‘Optimization Model for Zakat Distribution’.

Iman Chaerudin

Iman Chaerudin completed his postgraduate studies at ITB, after completing his undergraduate studies at the University of Padjadjaran’s Faculty of Economics and Business. He is the author of multiple monographs, such as ‘Economics of Recycling’, ‘Quatro Model’, and ‘Prime Service 4.0’ for airports.

Fadila Nurfauzia

Fadila Nurfauzia is pursuing a master’s degree at Universitas Padjadjaran’s Faculty of Economics and Business.

References

- Alawneh, F., & Zhang, G. (2018). Dual-channel warehouse and inventory management with stochastic demand. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 112, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2017.12.012

- Alishah, E. J., Moinzadeh, K., & Zhou, Y. P. (2017). Store fulfillment strategy for an omni-channel retailer. Retrieved from https://faculty.washington.edu/yongpin/omnichannel%20inventory%20paper.pdf

- Basumerda, C., Rahmi, U., & Sulistio, J. (2019). Warehouse server productivity analysis with objective matrix (OMAX) method in passenger boarding bridge enterprise. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 673(1), 012106. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/673/1/012106

- Braglia, M., Marrazzini, L., Padellini, L., & Rinaldi, R. (2021). Managerial and Industry 4.0 solutions for fashion supply chains. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 25(1), 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-12-2019-0285

- Bressolles, G., & Lang, G. (2019). KPIs for performance measurement of e-fulfillment systems in multi-channel retailing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 48(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-10-2017-0259

- Buldeo Rai, H., Verlinde, S., Macharis, C., Schoutteet, P., & Vanhaverbeke, L. (2019). Logistics outsourcing in omnichannel retail. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 49(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2018-0092

- Cai, Y.-J., & Lo, C. K. Y. (2020). Omni-channel management in the new retailing era: A systematic review and future research agenda. International Journal of Production Economics, 229, 107729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107729

- Catatan inventarisasi gudang yang tidak dipublikasikan [Unpublished Warehouse Inventory Records] (2021). FMC.

- Chen, Y., & Chi, T. (2021). How does channel integration affect consumers’ selection of omni-channel shopping methods? An empirical study of U.S. consumers. Sustainability, 13(16), 8983. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168983

- Choi, T.-M. (2014). Fashion retail supply chain management. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b16811

- Coccia, M. (2018). The fishbone diagram to identify, systematize and analyze the sources of general purpose technologies. Journal of Social and Administrative Science, 4(4), 291–303. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3100011

- de Borba, J. L. G., Magalhães, M. R., Filgueiras, R. S., & Bouzon, M. (2020). Barriers in omnichannel retailing returns: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 49(1), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-04-2020-0140

- Demirbas, S., & Ertem, M. A. (2021). Determination of equivalent warehouses in humanitarian logistics by reallocation of multiple item type inventories. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 66, 102603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102603

- Ding, S., & Kaminsky, P. M. (2020). Centralized and decentralized warehouse logistics collaboration. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 22(4), 812–831. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2019.0774

- Do Vale, G., Collin-Lachaud, I., & Lecocq, X. (2021). Micro-level practices of bricolage during business model innovation process: The case of digital transformation towards omni-channel retailing. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 37(2), 101154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2021.101154

- Eriksson, E., Norrman, A., & Kembro, J. (2019). Contextual adaptation of omni-channel grocery retailers’ online fulfilment centres. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 47(12), 1232–1250. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-08-2018-0182

- Hanum, B., Haekal, J., & Prasetio, D. E. (2020). The analysis of implementation of enterprise resource planning in the warehouse division of trading and service companies, Indonesia. International Journal of Engineering Research and Advanced Technology, 6(7), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.31695/IJERAT.2020.3621

- He, R., Li, H., Zhang, B., & Chen, M. (2020). The multi-level warehouse layout problem with uncertain information: Uncertainty theory method. International Journal of General Systems, 49(5), 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/03081079.2020.1778681

- Heizer, J., Render, B., Munson, C. L., & Griffin, P. (2020). Operations management: Sustainability and supply chain management. Pearson.

- Hu, M. (2022). Influence of project design team characteristics on construction cost of sustainable buildings [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Maryland. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/2685497798

- Hu, M., Xu, X., Xue, W., & Yang, Y. (2022). Demand pooling in omnichannel operations. Management Science, 68(2), 883–894. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2021.3964

- Indriya, I., Maulana, R., Baihaqi, A., Vikanda, V., & Ramadhan, A. (2021). The urgency of Indonesian Islamic fashionpreneur as part of the world’s halal industry. BASKARA: Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.54268/baskara.4.1.21-28

- Jayswal, A., Li, X., Zanwar, A., Lou, H. H., & Huang, Y. (2011). A sustainability root cause analysis methodology and its application. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 35(12), 2786–2798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2011.05.004

- Karim, N. H., Abdul Rahman, N. S. F., Md Hanafiah, R., Abdul Hamid, S., Ismail, A., Abd Kader, A. S., & Muda, M. S. (2021). Revising the warehouse productivity measurement indicators: Ratio-based benchmark. Maritime Business Review, 6(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/MABR-03-2020-0018

- Kembro, J. H., & Norrman, A. (2019). Warehouse configuration in omni-channel retailing: A multiple case study. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 50(5), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-01-2019-0034

- Kembro, J. H., Norrman, A., & Eriksson, E. (2018). Adapting warehouse operations and design to omni-channel logistics. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 48(9), 890–912. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-01-2017-0052

- Kembro, J., & Norrman, A. (2019). Exploring trends, implications and challenges for logistics information systems in omni-channels. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 47(4), 384–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-07-2017-0141

- Kleinsmith, N., Koene, B., & Jaehrling, K. (2018). Fast frock fashion logistics: The impact of new technologies on warehouse workers. RSM Case Development Centre. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1765/120901

- Kurniawan, A., & Pratiwi, Y. D. (2020). Analisis Pengukuran Kinerja Gudang Kayu di CV. Karya Purabaya. Iteks, 12(1), 60–67. Retrieved from https://ejournal.stt-wiworotomo.ac.id/index.php/iteks/article/view/293/357

- Kusrini, E., Novendri, F., & Helia, V. N. (2018). Determining key performance indicators for warehouse performance measurement – A case study in construction materials warehouse. MATEC Web of Conferences, 154, 01058. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201815401058

- Kusumawati, A., Listyorini, S., Suharyono, S., & Yulianto, E. (2019). The impact of religiosity on fashion knowledge, consumer-perceived value and patronage intention. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel, 23(4), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/RJTA-04-2019-0014

- Laosirihongthong, T., Adebanjo, D., Samaranayake, P., Subramanian, N., & Boon-Itt, S. (2018). Prioritizing warehouse performance measures in contemporary supply chains. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67(9), 1703–1726. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2018-0105

- Larke, R., Kilgour, M., & O’Connor, H. (2018). Build touchpoints and they will come: transitioning to omnichannel retailing. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 48(4), 465–483. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-09-2016-0276

- Lorenzo-Romero, C., Andrés-Martínez, M.-E., & Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.-A. (2020). Omnichannel in the fashion industry: A qualitative analysis from a supply-side perspective. Heliyon, 6(6), e04198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04198

- Lou, L., Zheng, Y., Tian, Y., & Deng, Y. (2019). Establishment of electric power marketing system based on data warehouse technology. In J. Xu (Ed.), 9th International Conference on Information and Social Science (pp. 416–420). https://doi.org/10.25236/iciss.2019.077

- Luo, H., Yang, X., & Kong, X. T. R. (2019). A synchronized production-warehouse management solution for reengineering the online-offline integrated order fulfillment. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 122, 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2018.12.010

- Mahroof, K. (2019). A human-centric perspective exploring the readiness towards smart warehousing: The case of a large retail distribution warehouse. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.11.008

- Millstein, M. A., Bilir, C., & Campbell, J. F. (2022). The effect of optimizing warehouse locations on omnichannel designs. European Journal of Operational Research, 301(2), 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2021.10.061

- Nathania, G., & Desrianty, A. (2023). Improved company productivities based on supply chain management performance measurement using Objective Matrix (OMAX) method. 080008. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0115146

- Prabhuram, T., Rajmohan, M., Tan, Y., & Robert Johnson, R. (2020). Performance evaluation of omni channel distribution network configurations using multi criteria decision making techniques. Annals of Operations Research, 288(1), 435–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03533-8

- Pradana, M., Elisa, H. P., & Syarifuddin, S. (2023). The growing trend of Islamic fashion: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2184557. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2184557

- Qurtubi, Q., Yanti, R., & Maghfiroh, M. F. N. (2022). Supply chain performance measurement on small medium enterprise garment industry: application of supply chain operation reference. Jurnal Sistem Dan Manajemen Industri, 6(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.30656/jsmi.v6i1.4536

- Redjeki, F., & Affandi, A. (2021). Utilization of digital marketing for MSME players as value creation for customers during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Science and Society, 3(1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.54783/ijsoc.v3i1.264

- Shi, S., Wang, Y., Chen, X., & Zhang, Q. (2020). Conceptualization of omnichannel customer experience and its impact on shopping intention: A mixed-method approach. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.09.001

- Slack, N., & Brandon-Jones, A. (2018). Operations and process management: Principles and practice for strategic impact. Pearson.

- State of The Global Islamic Economy Report (2022). Retrieved from https://www.dinarstandard.com/post/state-of-the-global-islamic-economy-report-2022

- Surodjo, B., Astuty, P., & Lukman, L. (2022, April 16). Creative economic potential of the fashion, crafts and culinary sub sector in the new normal era [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Law, Social Science, Economics, and Education, ICLSSEE 2022, Semarang, Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.16-4-2022.2319729

- Wardana, I. M. A., & Darma, G. S. (2020). Garment industry competitive advantage strategy during Covid-19 pandemic. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology, 17(1), 5598–5610. Retrieved from https://archives.palarch.nl/index.php/jae/article/view/2732