Abstract

Mindfulness is a concept that has been studied both in the East and in the West, which can be understood simply as a state of attention and response to stimuli. In the particular context of the travelling industry, mindfulness will raise customer-focused attention (FAT) and involvement in activities they participate in or in the services they receive. This research was conducted to test a model of mindfulness affecting loyalty (return intention and word of mouth) with the mediating role of customer experience. Quantitative analysis was performed with questionnaires from 388 respondents who are experiencing adventure tourism in Vietnam with 15 travel agents. The result shows that (1) Novelty producing (NOP), novelty seeking (NOS) and FAT have significant contributions to Mindfulness (2) Mindfulness has a positive effect on customer experience, return intention and word of mouth (3) Customer experience both has a direct impact and acts as an intermediary factor affecting return intention and word of mouth. The findings contribute academically to testing the mindfulness scale and the causal relationship between this factor and customer loyalty. It also allows the managers to improve overall customer loyalty through a better understanding of its dimensions.

1. Introduction

There are some definitions of adventure tourism. The most common given by United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO World Tourism Organization, Citation2019) is a type of tourism which usually takes place in destinations with specific geographic features and landscape and tends to be associated with a physical activity, cultural exchange, interaction and engagement with nature. This experience may involve some kind of real or perceived risk and may require significant physical and/or mental effort.

Adventure tourism with characteristics associated with specific geographic features and landscape and tends to be associated with physical activity, cultural exchange, interaction and engagement with nature. These factors create an environment consistent with the components of mindfulness developed by Langer (Citation1989) which are novelty seeking (NOS), novelty producing (NOP) and focused attention (FAT).

Adventure tourism is considered a tool for economic growth. In its simplest terms, it can be described as the expansion of economic activity in a particular area with the aim of raising the average income of the people in the area (Carvache-Franco et al., Citation2022). This activity creates stable employment opportunities for the local population, contributes additional income and helps develop the infrastructure of the area which is often considered underdeveloped (usually remote areas with special topographical and geographical features such as limestone mountains with caves in the central region, ethnic minority areas in northern Vietnam). Furthermore, adventure tourism refers to a broader concept that, in addition to economic benefits, also refers to creating appropriate changes in the structure of economic activities while ensuring income and wealth distribution (Rojo-Ramos et al., Citation2023).

Along with the excited development to an experience behaviour and its specific relevance to the tourist activities, tourism is on the rising tendency to produce an exclusive experience for the guest to increase their satisfaction and loyalty (Klaus, Citation2014). Although in travel research, mindfulness has been measured as a valuable instrument for handling customer experience (Barber & Deale, Citation2014). Ndubisi (Citation2012) brought up results from the absence of comprehension of how mindfulness works out in the customer decision processes, and its suggestions for consumer behaviour theory and practice research, because of the lack of empirical study, and called for additional investigations. Even though some research has used the mindfulness concept in tourism papers such as Chen et al. (Citation2017), Barber and Deale (Citation2014); no studies of mindfulness are found in the adventure tourism industry. Also, no former research emphasis on recognizing the primary components and sub-components of mindfulness via a multidimensional and hierarchical model in the adventure tourism context.

Mindfulness has shown up in academic writing for more than decades from clinics, stretching out to the areas of psychology, marketing and education (Campos Sousa & Freire, Citation2022; Taylor & Norman, Citation2019). In consumer behaviour, mindfulness is considered a significant component for grasping buyer conduct (Ben Haobin et al., Citation2021; Ndubisi, Citation2014). Research on the topic of mindfulness in the field of tourism is approached in two directions: meditative mindfulness (Buddhist philosophy) and socio-cognitive mindfulness (Western social psychology). Its effects are mainly psychological and physical benefits, and behavioural changes (Chen et al., Citation2017). Mindfulness is utilised to evaluate the profundity of voyagers’ behaviour and its impact on their experience there (Frauman & Norman, Citation2004; Van Winkle & Backman, Citation2008), ; including the positive influences on confidence, satisfaction, loyalty (Şehirli, Citation2022; Taylor & Norman, Citation2019). In the study of Taylor and Norman (Citation2019) loyalty factor is divided into attitudinal and behavioural loyalty.

The fundamental targets of this research is to validate the measurement of mindfulness and to test Mindfulness affecting loyalty (return intention and word of mouth) with mediating role of customer experience in the context of adventure tourism in Vietnam. Research results contribute academically in testing mindfulness scale and the causal relationship between this factor and customer loyalty. The two main contributions of this study are: (1) this study employs a multidimensional and hierarchical approach to conceptualise and measure mindfulness; (2) it contributes to the marketing literature by providing an empirical investigation of relationship between and mindfulness, customer experience, loyalty – return intention and loyalty – word of mouth. Many studies on mindfulness have focused on its mechanisms to help people relax, eliminate negative emotions, overcome stress, etc. Therefore, studying the relationship between mindfulness and customer loyalty (return intention and word of mouth) is still a new research direction, especially in the context of adventure tourism.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Mindfulness

Langer (Citation1989) and Kabat-Zinn (Citation2005) have dominated approaches to mindfulness research and practice in two different approaches corresponding to the Eastern meditation-based and the Western socio-cognitive. Even though mindfulness is not a religious or spiritual idea in and of itself, the first approach has its roots in Buddhist traditions, where meditation training and practice lead to the experience of mindfulness (Chen et al., Citation2017). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), which was established by Kabat-Zinn and Delta Trade pbk. Reissue (Citation2009), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), which was developed by Segal et al. (Citation2002) in medical facilities. Some other authors also developed in this direction, including: Campos Sousa and Freire (Citation2022), Taylor and Norman (Citation2019). The first type of mindfulness, based on an Eastern meditation tradition, defines mindfulness as a state of ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the here and now, and without judging others’ (Chen et al., Citation2017; Kabat-Zinn, Citation2005).

Based entirely on the cognitive information-processing foundation, the second line of research investigates mindfulness (Sauer et al., Citation2013). According to Haigh et al. (Citation2011) and Langer (Citation1989), the mindfulness concept is derived from Western socio-cognitive literature and cognitive psychology. They define mindfulness as a mindset of NOS, NOP, FAT and engagement. This point of view is closely related to the work of Ellen Langer, who referred to mindfulness as ‘a general style or mode of functioning through which the individual actively engages in reconstructing the environment through creating new categories or distinctions, thus directing attention to new contextual cues that may be consciously controlled or manipulated as appropriate’ (Langer, Citation1989). Langer defined mindfulness as ‘a general style or mode of functioning’ in her work. A mindfulness perspective that emphasises creativity is reflected in this socio-cognitive approach (Bercovitz et al., Citation2017; Chan, Citation2019; Hart et al., Citation2013), which is a concept that is related to but different from the contemplative way. Precisely, the Eastern-Buddhist perspective focuses on the present inner experience, whereas the Western socio-cognitive perspective typically theories mindfulness by including the individual’s material, external, and social context (Chan, Citation2019; Kabat-Zinn, Citation2005; Pirson et al., Citation2012). For instance, there is no important association between the dimensions from the two different methods to mindfulness or ‘every mindfulness’ as it is expressed in everyday life and mindfulness achieved through meditation practice (Kaplan et al., Citation2018; Thompson & Waltz, Citation2007).

From the perspective of behavioural psychology, the elements of mindfulness are regarded as potentially effective antidotes against common forms of psychological distress such as rumination, anxiety, worry, fear, anger and so on (Hayes et al. Citation2005; Suthatorn & Charoensukmongkol, Citation2023). Bishop et al. (Citation2004) propose a two-component model of mindfulness and specify each component in terms of specific behaviours, experiential manifestations and implicated psychological processes, including (1) self-regulation of attention and (2) adopting a specific orientation toward one’s experience. Self-regulated attention refers to the non-elaborative observation and awareness of sensations, thoughts or feelings from moment to moment. Experience orientation refers to the type of attitude a person has toward his or her experiences, especially attitudes of curiosity, openness, and acceptance (Şehirli, Citation2022; Taylor & Norman, Citation2019).

In some studies on the role of mindfulness in eliminating stress at work or under the pressure of adverse situational factors such as the Covid 19 pandemic, mindfulness is an important individual characteristic that enables people to use adaptive coping responses to deal with stress unpleasant emotional states that have a negative impact on mental health (Bostock et al., Citation2019; Brown & Ryan, Citation2003; Campos Sousa & Freire, Citation2022; Taylor & Norman, Citation2019). Two mechanisms may explain why mindfulness can exert such a moderating function: decentering and reappraisal and value clarification (Montani et al., Citation2020, Ben Haobin et al., Citation2021; Shapiro et al., Citation2011). Decentering is the process by which mindful individuals are able to observe rather than identify with the content of consciousness and external events. Through decentering, mindfulness disrupts automatic conditioned reactions and enables a conscious reflection of the assessed stressor. Therefore, mindfulness clears working memory and provides opportunities for perspective taking and cognitive flexibility, thereby laying the foundation for reappraisal as an important secondary mechanism (Garland et al., Citation2009).

2.2. Customer experience and loyalty

According to previous research (Holbrook & Hirschman, Citation1982), consumers buying behaviour is not only for practical reasons but also for emotional motives like pleasure, fun or enjoyment based on their experiences. Marketers contend that clients are both rational and emotional and that they also care about having enjoyable experiences. Experiential marketing prioritises customer experiences rather than focusing on benefits and functional features (Schmitt, Citation1999). Otto and Ritchie (Citation1995) argue that customer experience cannot be objectively measured; Customer experience is typically holistic or gestalt rather than attribute-based, and evaluation focuses on the self (internal) rather than the service environment (external). The nature of benefit is experiential/hedonic/symbolic rather than functional/utilitarian, the scope of experience is found to be more general than specific, and the psychological representation is affective rather than cognitive/attitudinal. Customer experience primarily corresponds to hedonic utility-related experiential or emotional aspects (Batra & Ahtola, Citation1990; Tontini et al., Citation2013). Some researchers (Ladhari et al., Citation2017; Otto & Richie, Citation1995; Vasconcelos et al., Citation2015) studied customer experience combined with service quality; these two factors are measured simultaneously. They are indistinguishable from one another, but they work well together. Both are the results of customers’ evaluations of service quality.

Traditional and modern marketing often view consumer loyalty as a key success factor for a business especially in service sector; recent empirical studies indicate that customer loyalty is composed of two sub-factors, repurchase intention and word of mouth (Karim et al., Citation2022; Ngoc Quang & Thuy, Citation2023). Some other authors add sub-factor: recommend it to friends and other people, pay more money to purchase products (Lee et al., Citation2019; Lee & Chang, Citation2012).

The relationship between customer experience and loyalty is of interest to several researchers. summarises their research findings.

Table 1. Summary of previous studies of the relationship between customer experience and loyalty in hospitality Industry.

2.3. The impact of mindfulness on customer experience and loyalty

The most common explanation for mindfulness is attention and awareness. The first idea is a response to external incentives, while the second is the first sign of a powerful incentive (Brown et al., Citation2007). According to Grossman et al. (Citation2004), a person’s capacity to concentrate on the present situation varies. A Mindfulness situation, that enables persons to pay attention to the current situation, mainly the experience within an explicit situation, is a result of this ability. Mindful customers are able to absorb and understand news, discover substitute or inventive perspectives, and are thus more likely to be open to new context and to control their behaviour positively, according to a number of researchers (Fiol & O’Connor, Citation2003; Langer, Citation1989; Moscardo et al., Citation2004).

Langer and Moldoveanu (Citation2000) demonstrate that mindfulness enables individuals to become more involved in the various tasks in front of them. According to the authors, mindfulness’s subjective ‘feel’ is a more involved and awakened state, or being in the moment. This subjective state serves as the inherent link between the numerous observable moments for the viewer. Mindfulness is not an unemotional process of thinking. The whole person is involved when new distinctions are actively drawn. As a result, it is reasonable to anticipate that mindfulness in a hedonic service setting like adventure tourism will grow customer assignation and involvement in events they participate in or in the services they receive. According to Fiol and O’Connor (Citation2003), persons who are mindfully involved in a task are also inspired and able to discover broader perspectives. They are also able to make distinctions about phenomena in their environments that are more relevant and precise, allowing them to adapt to changes in those environments.

Moscardo (Citation1996) theories that will occur as a result of a particular cognitive state in the mindfulness of tourist behaviour and cognition. While visiting a heritage attraction, mindlessness would result in slight learning, little satisfaction and little understanding, mindfulness is thought to result in more learning, higher levels of satisfaction and greater understanding. According to McIntosh (Citation1999), mindfulness could lead to insight into the experience. Mindful people pay attention to the world, react to new information, and develop new habits, behaviours and perspectives. Therefore, mindfulness is a necessary but not sufficient condition for learning. Mindfulness has been linked to better educational outcomes by a number of authors (Langer, Citation1989). According to Leary and Tate (Citation2007), a mindful person has better self-control and self-regulatory capacity, as well as a greater capacity for understanding and repairing negative moods, and a stronger sense of compassion for other people (Beitel et al., Citation2005). Mindlessness is related to sensations of control, interest and happiness, while thoughtlessness is related to misguided thinking, sensations of fragmented and fatigue (Moscardo, Citation1999). Chen et al. (Citation2017) examine the relationship between meditative mindfulness (Buddhist Perspective) and tourist experience and explore the role of mindful mental states in producing experiential outcomes. In the research of Ling et al. (Citation2019), NOS appeared as the communication aspect most related with the state of mindfulness, and mindfulness factor is influenced by the linking created by visitors between self and the heritage setting. Chan’s research confirms that mindfulness can create sustainable behaviours in a tourism context (Chan, Citation2019).

There is very little current research on the connection between mindfulness and customer loyalty. Ben Haobin et al. (Citation2021) state that, customers’ mindfulness mediated the relationship between perceived hotel servicescape and brand experience in the hotel industry, as servicescape encourages customers’ mindfulness (focused awareness of the present moment). According to Campos Sousa and Freire (Citation2022), a mindfulness-based solution to the problem of long wait times, particularly in healthcare facilities, has the potential to improve customers’ waiting experience. They also showed that modifying a 5-min mindfulness-based intervention resulted in more favourable perceptions and intentions to remain loyal to the service.

The relationship between mindfulness and repurchase intention has not been widely studied. Şehirli (Citation2022) suggested that there is an impact of mindfulness on job satisfaction of employees, customer satisfaction and their repurchase intentions. There is no research on the relationship of mindfulness and word of mouth. Close to this topic, Kiken and Shook (Citation2011) confirmed that mindfulness grows positive judgments and reduces negativity prejudice.

2.4. Hypothesis development

From the conversation above, it is instigated that expanded mindfulness is probably going to have a positive impact on Customers’ service experience and loyalty (repurchase intention and word of mouth), in this way the accompanying hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Mindfulness has a positive influence Customers’ service experience

H2: Mindfulness has a positive influence loyalty – repurchase intention

H3: Mindfulness has a positive influence loyalty – word of mouth

H4: Customers’ service experience has a positive influence loyalty – repurchase intention

H5: Customers’ service experience has a positive influence loyalty – word of mouth

H6: Loyalty – repurchase intention has a positive influence loyalty – word of mouth

H7: Customers’ service experience mediates the relationship between Mindfulness on loyalty – repurchase intention

H8: Customers’ service experience mediates the relationship between Mindfulness on loyalty – word of mouth

H9: Loyalty – repurchase intention mediates the relationship between Mindfulness on loyalty – word of mouth

H10: Loyalty – repurchase intention mediates the relationship between Customers’ service experience on loyalty – word of mouth

3. Research methodology

3.1. Conceptual framework

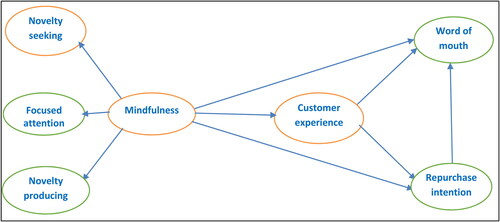

The purpose of the research is to develop and test a model of mindfulness, applied to the adventure tourism, outlining relevant dimensions and outcomes (independent factor: mindfulness, mediating factor: customers’ service experience, dependent factor: repurchase intention and word of mouth. The research framework models mindfulness as a second-order dimension, determined by the three sub-factors and relevant factors presented in .

3.2. Measurement instrument

The measurement instruments for this study were established scales from previous studies, adapted to fit the study setting. The 18 items measuring mindfulness were modified from Langer (Citation1989), including three domains: NOS (6 items), FAT (6 items) and NOP (6 items). Customers’ service experience was measured with 6 items modified from Otto and Ritchie (Citation1996), including three domains: hedonics, peace of mind and symbolic. Loyalty repurchase intention and word of mouth were modified from Ngoc Quang and Thuy (Citation2023) with 8 items. The details are presented in . With the exception of the questions regarding consumer characteristics, all items employed seven-point Likert scales, with 1 equalling ‘strongly disagree’ and 7 equalling ‘strongly agree’. A list of the initially generated items for the survey questionnaire was given to the six experts in order to achieve face validity. This procedure led to removal of some unclear items, modifying and rewording others for the travel context of the study to ensure consistency.

Table 2. Measurement scale.

3.3. Sample, data collection procedures and data analysis

Data were collected via questionnaire-based survey in 15 travel agents in Vietnam using a Google form survey approach. This study uses a quota sampling method and the sampling frame of the survey was the adventure tourism customers of 15 travel agents selected; they have had adventure travel experiences in the last 12 months. Since this study intends to target adults who are experiencing adventure tourism in Vietnam. Travel agents were responsible for sending survey questionnaires and their collection after being filled for their respective agents. The travel agent managers’ involvement in the process of data collection also ensured the overall external validity and reliability of this study. The questionnaire was designed in bilingual English and Vietnamese, so it is suitable for both foreigners and Vietnamese people.

There were 32 variables in the questionnaire; in this way, with somewhere around 5 observations for every variable (Bentler & Chou, Citation1987), the base example size is 32 × 5 = 160 observations. However, 388 valid questionnaires have been collected to improve the research’s quality. To verify the reliability and validity of scales, as well as to test the relationships between factors and conduct structural equation modelling (SEM) analysis, data were analysed using SPSS 22 and AMOS 24 software. The higher-order construct of mindfulness was modelled by using the hierarchical components or repeated indicators approach, where the indicators of the three lower-order dimensions are repeated to measure the higher-order construct. The reliability and validity test, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and SEM are the primary analytical tools utilised.

4. Research findings

4.1. Sample characteristics

The survey respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics are as follows: Approximately 58.5% of respondents were male, with 36.8% being between the ages of 26 and 35, 29.4% being between the ages of 36 and 50, 25.1% being under the age of 26, and 8.7% being over the age of 50. The vast majority of the respondents were married (48.2%) trailed by the individuals who were living with an accomplice (25.3%), single (16.2%), while the excess was divorced/separated (10.3%). About 55.7% of respondents had higher education degrees, 41.4% had completed their secondary education, and 2.9% had completed their primary education. 44.6% of respondents worked as professionals, while 32.5% were employed. Of the respondents, 52.3% reported that they have adventure tourism once a year, the number of the respondents going twice or more accounts for 37.1%, the rest (10.6%) go on some special occasions.

4.2. Measuring the validity of scales and reliability

The measurement model of mindfulness and marketing outcomes (customer experience, loyalty – repurchase intention and loyalty – word of mouth) was tested/assessed, including reliability (Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability [CR]), convergent validity (factor loadings, average variance extracted [AVE]) and discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2017). These 32 variables were analysed for EFA and consequent CFA to assess unidimensionality, the convergent and discriminant of factor and variable. The maximum likelihood assessment was used for validation (Arbuckle, Citation2011). The following values were calculated: Chi squared, Chi Square adjusted to degrees of freedom (CMIN/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker & Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), root mean square error approximation (RMSEA). The model is suitable with data collected when CMIN/df < 5; GFI, TLI, CFI > 0.9; RMSEA < 0.08, RMSEA < 0.5 is considered very good (Byrne, Citation1994; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The results are offered in .

Table 3. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

The results in show that the construction suits the assessment data. We are therefore, able to state that the NOS, NOP, FAT, customer experience, loyalty repurchase intention and loyalty word-of-mouth factors all achieve convergent validity. In conclusion, both theoretically and empirically, measurement models perform well. We used SEM to examine the complete model fit in the following section.

To get a comprehensive picture of the scale’s reliability, we also looked at the CR and the AVE. As indicated by Hair et al. (Citation2006), at the point when CR > 0.7 and AVE > 0.5, the scale is viewed as a convergent value, and the observed variable is not correlated with other observed variables in the same factor. displays the CR and AVE outcomes.

Table 4. Results of CR and AVE of scales.

As a result, the introduction of the CR and AVE results suggests that the scale obtained from the formal quantitative examination is suitable for testing the established research hypotheses and model. Discriminant validity was evaluated by the square root of the AVE for each specified factor. shows the square root of AVE (the bold number diagonal) for each factor was greater than its correlation with all other factors. This result further confirms the discriminant validity amongst all dimensions in the measurement model (Hair et al., Citation2017).

Table 5. Correlations and the square root of AVE.

4.3. Structural measurement model

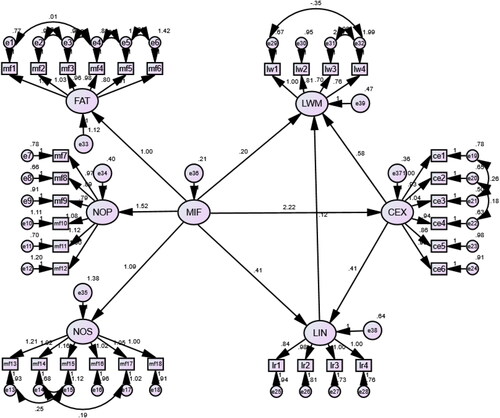

The structural model is designed with an independent factor, mindfulness, with three sub-factors (NOS, FAT, NOP) that generate second order constructs, and with the customer experience as an intermediate factor, and two dependent factors, the loyalty word-of-mouth and loyalty repurchase intention. The last one is also used as an intermediate factor. Essentially all results at fit records in this structural equation model produce positive outcomes. The fit of the models was assessed using chi-square statistics and various fit indices such as RMSEA, Chi-square/Df (CFA), CFI, the GFI, TLI, non-normed fit index (NFI). The predictable calculations of this SEM are shown in as follows: 2.456 Chi-square/Df <5; GFI = 0.902 > 0.9; CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.905 > 0.9; RMSEA = 0.061 < 0.08. Furthermore, and show the hypothesis results. So, the structural equation model is suitable with data collected.

Table 6. Direct hypothesis results.

Table 7. Direct – indirect – total effect hypothesis results.

Research results in show that the mindfulness factor is made up of 3 sub-factors: NOS), NOP and FAT. In which, NOP has the strongest contribution to Mindfulness, with the regression weight reaching 1.52. The remaining two sub-factors NOS, FAT have respective contributions of 1.09 and 1 to mindfulness. This result proves that tourists value NOP in their travel. This factor has a direct impact on customer experience with the highest regression weight reaching 2.22. Next, its direct impact on loyalty – repurchase intention and loyalty – word of mouth factor with regression weights of 0.41 and 0.2, respectively. The direct hypothesis results in show that hypothesis H1, H2 and H3 are accepted. Customer experience factor has a direct impact on loyalty – repurchase intention and loyalty – word of mouth factor with regression weights of 0.41 and 0.58, respectively. The direct hypothesis results in show that hypothesis H4, H5 is accepted. Hypothesis H6. The effect of loyalty – repurchase intention factor on loyalty – word of mouth factor is rejected because it has a p value of 0.084 > 0.05. This result is also similar to some research results of Ben Haobin et al. (Citation2021) and Şehirli (Citation2022).

Calculation results of direct, indirect and total effect in show that: the hypothesis H7 included in the total effect regression reached 1.322, with a direct effect of 0.412 and an indirect effect of 0.910; hypothesis H8 and H9 are integrated into a result where the total effect reaches 1.645. This result is generated mainly through indirect effect with regression weight of 1.448, while the direct effect only reaches 0.196. Hypothesis H10 has a total effect regression weight of 0.630, in which the impact mainly comes from direct effect with the result of 0.581, indirect effect only has a very small regression value at 0.049.

5. Conclusion and implications for marketers, limitations and future research

5.1. Conclusion

This research has recognised the Mindfulness structure as multidimensional and second-order dimensions. It backs up the idea that the Mindfulness dimensionality is dependent on the specific situation under study (Moafian et al., Citation2017; Van Winkle & Backman, Citation2008;). Mindfulness application in marketing and consumer behaviour have begun to show up, while the matter of measurement model misspecification is shared in study (Ndubisi, Citation2014). Hence, this is the first research in adventure tourism creating and validating Mindfulness as a second-order dimension that supports the discovery of more thoughtful Mindfulness. This study also quantifies the relationship of mindfulness with loyalty for the first time with two sub-factors, return intention and word of mouth. More specifically, the theoretical contributions of this study are: complete and validate the mindfulness questionnaire with 3 sub-factors (NOS, FAT, NOP); customers’ service experience and loyalty factor with 2 sub-factors (return intentions and word of mouth) that applied in research on adventure tourism in Vietnam. The proposed model and its testing results have confirmed the position of these factors in the causal relationship or its mediating role. This model is the main theoretical contribution of this study. Previously, the work of Şehirli (Citation2022) suggested that there is an impact of mindfulness on job satisfaction of employees, customer satisfaction and repurchase intention. Mindfulness (NOS motivation and mindful oriented information services) indirectly affects loyalty destination through emotional factor (Rubin et al., Citation2016). However, both of these studies found that mindfulness only had an indirect effect on loyalty. So, the research results contribute to opening up a new research direction, which is the direct impact of mindfulness on tourist experience and behaviour, especially the behaviour of returning to tourist destinations in adventure tourism. It is also important to add that adventure travel has diverse activities related to physical activity, cultural exchange, interaction, and engagement with nature; Therefore, there needs to be specific research in each of these areas to evaluate the impact of mindfulness in each specific situation.

The examination has experimentally affirmed the current mindfulness models proposed by Moafian et al. (Citation2017), in which mindfulness is one of the impacting dimensions, related with clients’ experience and their assessments (Barber & Deale, Citation2014) or insightfulness (Frauman & Norman, Citation2004; McIntosh, Citation1999). The study also reinforced the other experimental results that mindfulness reason positive consequences, such as cultivating benefits pursued (Frauman & Norman, Citation2004) or in hotel stay (Barber & Deale, Citation2014; Ndubisi, Citation2014), influencing customer experience perception and assessment of client experience (client satisfaction and loyalty intentions) in exhibition activity (Choe et al., Citation2014); relating with relation between customer and service provider in health care service (Guan et al., Citation2021; Ndubisi, Citation2014). In the adventure tourism situation of this research, guest mindfulness helps receive and reply more positively to services provided and interaction in the adventure trip. It also enables guests to enjoy their discovery trip better, creating a more outstanding experience, having return intention and having positive word of mouth.

5.2. Implications for marketers

The results of the CFA study show that the strongest contributing factor to mindfulness is NOP with weight gain 1.52, the other two factors with similar value are NOS and FAT with corresponding weights 1.09 and 1.0. These results show that the main concern of adventure tourism guests is to experience new things and create new things for them during the trip. This suggests marketers focus more on creating new experiences, and providing products and services that create new discoveries for customers during the trip. Besides, it is also necessary to maintain the elements that create NOS and FAT so that customers always have a positive mindfulness, thereby motivating them to have positive experiences and loyalty expressed through return intention and positive word of mouth about their discovery.

The results of the SEM model study show that mindfulness has the strongest impact on customer experience with a regression weight of 2.22, followed by loyalty return intention and the lowest to loyalty word of mouth with corresponding weights of 0.412 and 0.196. This result is similar to the study of Lee et al. (Citation2019). This suggests to marketers that it is necessary to promote customer mindfulness in adventure tourism, thereby positively impacting customer experience and return intention. Specifically, the factors that need attention are NOP, NOS and FAT. Besides, customer experience also has a positive effect on word of mouth and return intention, the regression weights are 0.581 and 0.408, respectively. This relationship is widely recognized in studies of consumer behaviour. In the field of adventure tourism, the suggestion for marketers is to always create new experiences for visitors, it can come from employees, services, destinations, processes, novel situations, visitors’ discoveries.

Besides the direct effects, mindfulness and customer experience also have indirect effects on return intention and word of mouth. The total effect of mindfulness on word of mouth reached a regression weight of 1322 (direct 0.412; indirect 0.910). The total effect of mindfulness on return intention has a regression weight of 1645 (direct 0.196; indirect 1.448). This result shows that the indirect effect has a much larger influence than the direct one. This suggests that marketers need to focus their resources on the intermediary variable, customer experience. The total effect of customer experience on word of mouth has a regression weight of 0.630 (direct 0.581; indirect 0.049). Thus, the indirect impact is small, mainly the direct impact. This result shows that visitors only have a positive word of mouth when they have a good experience, and return intention does not generate a word of mouth. In managerial terms, marketers could improve customer experience through providing better service experience in discovery trips such as escapism, pleasure, happiness, relaxation, and peace. Marketers can also determine which experience dimensions are most strongly associated with customer loyalty outcomes and, thus, improve the effectiveness of marketing investments.

5.3. Limitations and future research

The limitation of this study is that it has not been able to clarify the causal factors that form visitor mindfulness, so the recommendations for marketers are only suggestions according to the structure of mindfulness (NOS, NOP, FAT). The field of adventure tourism is highly specific, consumer behaviour is very different, so the use of these recommendations in other areas should be cautious. Customer loyalty is affected by many factors, in this model only mentions mindfulness and customer experience factors, so the model ignores many important factors such as the brand reputation of the tour operator, the characteristics of discovered destinations, and the customer satisfaction.

Stemming from the limitations of this study, future studies may develop the causal factors of customer mindfulness, then it is only an intermediate variable in the model. Thereby answering the question of why customers are mindful of the products and services of the business. These studies can also integrate into the model new factors affecting loyalty, such as brand reputation of tour operators, characteristics of discovered destinations, and visitor satisfaction. Thus, the research results will create a more complete structure of the factors affecting customer loyalty.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nguyen Ngoc Quang

Nguyen Ngoc Quang is a lecturer of Marketing at Marketing Faculty – National Economics University (Vietnam). His research interests focus on consumer behavior and marketing management; recent studies related to customer behavioral psychology in retail banking, telecommunications services and mindfulness in hotel services. He is co-author of several books on marketing management and papers in Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, Cogent Business & Management, International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology.

Dao Cam Thuy

Dao Cam Thuy is a lecturer of marketing and branding at Marketing Department – School of Business and Administration, VNU University of Economics & Business (Vietnam). Dr. Dao Cam Thuy has many years of experience working for banks and big corporations in Vietnam and owns an education business. Her research has focused on customer behavior in the digital age, brand management and marketing management for small and medium enterprises. She is a co-author of papers in Cogent Business & Management, International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and so on. In addition, she also has experience in training and consulting for many businesses in Vietnam in micro-market assessment, brand development and leadership’s personal brand.

References

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2011). Amos 20 user’s guide. SPSS Inc.

- Barber, N. A., & Deale, C. (2014). Tapping mindfulness to shape hotel guests’ sustainable behavior. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 55(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513496315

- Batra, R., & Ahtola, O. T. (1990). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Marketing Letters, 2(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00436035

- Beitel, M., Ferrer, E., & Cecero, J. J. (2005). Psychological mindedness and awareness of self and others. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20095

- Ben Haobin, Y., Huiyue, Y., Peng, L., & Fong, L. H. N. (2021). The impact of hotel servicescape on customer mindfulness and brand experience: The moderating role of length of stay. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(5), 592–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2021.1870186

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16(1), 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004

- Bercovitz, K., Pagnini, F., Phillips, D., & Langer, E. (2017). Utilizing a creative task to assess Langerian mindfulness. Creativity Research Journal, 29(2), 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2017.1304080

- Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

- Bostock, S., Crosswell, A. D., Prather, A. A., & Steptoe, A. (2019). Mindfulness on-the-go: Effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000118

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

- Brown, K. W., Ryan, R., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598298

- Byrne, B. M. (1994). Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applicatins, and programming. Sage.

- Campos Sousa, E., & Freire, L. (2022). The effect of brief mindfulness‐based intervention on patient satisfaction & loyalty after waiting. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57(2), 906–942. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12488

- Carvache-Franco, M., Contreras-Moscol, D., Orden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Vera-Holguin, H., & Carvache-Franco, O. (2022). Motivations and loyalty of the demand for adventure tourism as sustainable travel. Sustainability, 14(14), 8472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148472

- Cetin, G. (2020). Experience vs. quality: Predicting satisfaction and loyalty in services. The Service Industries Journal, 40(15–16), 1167–1182. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2020.1807005

- Chan, E. Y. (2019). Mindfulness promotes sustainable tourism: The case of Uluru. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(13), 1526–1530. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1455647

- Chen, L. L., Scott, N., & Benckendorff, P. (2017). Mindful tourist experiences: A Buddhist perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.01.013

- Choe, Y., Lee, S. M., & Kim, D. K. (2014). Understanding the exhibition attendees’ evaluation of their experiences: A comparison between high versus low mindful visitors. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 31(7), 899–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2014.890157

- Dong Xuan, D. (2017). Factors affecting tourist destination choice: A survey of international travelers to Hanoi, Vietnam. Journal of Economics and Development, 9(11), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.33301/2017.19.01.06

- Fiol, C. M., & O’Connor, E. J. (2003). Waking up! Mindfulness in the face of bandwagons. Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 54–70. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040689

- Frauman, E., & Norman, W. C. (2004). Mindfulness as a tool for managing visitors to tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 42(4), 381–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504263033

- Garland, E., Gaylord, S., & Park, J. (2009). The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore (New York, NY), 5(1), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2008.10.001

- Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits-A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

- Guan, J., Wang, W., Guo, Z., Chan, J. H., & Qi, X. (2021). Customer experience and brand loyalty in the full-service hotel sector: The role of brand affect customer experience and brand loyalty. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(5), 1620–1645. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2020-1177

- Haigh, E. A. P., Moore, M. T., Kashdan, T. B., & Fresco, D. M. (2011). Examination of the factor structure and concurrent validity of the langer mindfulness/mindlessness scale. Assessment, 18(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110386342

- Hair, B., Babin., & Tatha, A. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hart, R., Ivtzan, I., & Hart, D. (2013). Mind the gap in mindfulness research: A comparative account of the leading schools of thought. Review of General Psychology, 17(4), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035212

- Hayes, A. M., Beevers, C. G., Feldman, G. C., Laurenceau, J. P., & Perlman, C. (2005). Avoidance and processing as predictors of symptom change and positive growth in an integrative therapy for depression. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_9

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.1086/208906

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Ittamalla, R., & Srinivas Kumar, D. V. (2021). Determinants of holistic passenger experience in public transportation: Scale development and validation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102564

- Kabat-Zinn, J, Delta Trade pbk. Reissue. (2009). Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delta Trade Paperbacks.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

- Kaplan, D. M., Raison, C. L., Milek, A., Tackman, A. M., Pace, T. W., & Mehl, M. R. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness in daily life: A naturalistic observation study. PLoS One, 13(11), e0206029. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206029

- Karim, R. A., Sobhani, F. A., Rabiul, M. K., Lepee, N. J., Kabir, M. R., & Chowdhury, M. A. M. (2022). Linking fintech payment services and customer loyalty intention in the hospitality industry: The mediating role of customer experience and attitude. Sustainability, 14(24), 16481. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416481

- Kiken, L. G., & Shook, N. J. (2011). Looking up: Mindfulness increases positive judgments and reduces negativity bias. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(4), 425–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550610396585

- Klaus, P. (2014). Measuring customer experience: How to develop and execute the most profitable customer experience strategies. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ladhari, R., Souiden, N., & Dufour, B. (2017). The role of emotions in utilitarian service settings: The effects of emotional satisfaction on product perception and behavioral intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.09.005

- Langer, E. J. (1989). Mindfulness. Addison-Wesley.

- Langer, E., & Moldoveanu, M. (2000). The construct of mindfulness. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00148

- Leary, M. R., & Tate, E. B. (2007). The multi-faceted nature of mindfulness. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701598355

- Lee, T. H., & Chang, Y. S. (2012). The influence of experiential marketing and activity involvement on the loyalty intentions of wine tourists in Taiwan. Leisure Studies, 31(1), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.568067

- Lee, T., Fu, C. J., & Tsai, L. F. (2019). How servicescape and service experience affect loyalty: evidence from attendees at the Taipei International Travel Fair. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 20(5), 398–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/15470148.2019.1658002

- Ling, T. P., Noor, S. M., Mustafa, H., & Kiumarsi, S. (2019). Mindfulness: Exploring visitor and communication factors at Penang heritage sites. SEARCH Malaysia, 11(1), 137–152.

- McIntosh, A. J. (1999). Into the tourist’s mind: Understanding the value of the heritage experience. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 8(1), 41–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v08n01_03

- Moafian, F., Pagnini, F., & Khoshsima, H. (2017). Validation of the Persian version of the langer mindfulness scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00468

- Montani, F., Vandenberghe, C., Khedhaouria, A., & Courcy, F. (2020). Examining the inverted U-shaped relationship between workload and innovative work behavior: The role of work engagement and mindfulness. Human Relations, 73(1), 59–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718819055

- Moscardo, G. (1996). Mindful visitors: Heritage and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(2), 376–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00068–2

- Moscardo, G. (1999). Making visitors mindful: Principles for creating sustainable visitor experiences through effective communication. Sagamore Publishing.

- Moscardo, G. (2009). Understanding tourist experience through mindfulness theory. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203881804-17

- Moscardo, G., Woods, B., & Saltzer, R. (2004). The role of interpretation in wildlife tourism. In K. Higginbottom (Ed.), Wildlife tourism: Impacts, management and planning (pp. 231–240). Common Ground Publishing.

- Ndubisi, N. O. (2012). Mindfulness, reliability, pre-emptive conflict handling, customer orientation and outcomes in Malaysia’s healthcare sector. Journal of Business Research, 65(4), 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.02.019

- Ndubisi, N. O. (2014). Consumer mindfulness and marketing implications. Psychology & Marketing, 31(4), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20691

- Ngoc Quang, N., & Thuy, D. C. (2023). Justice and trustworthiness factors affecting customer loyalty with mediating role of satisfaction with complaint handling: Zalo OTT Vietnamese customer case. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2211821. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2211821

- Otto, J. E., & Richie, J. R. B. (1995). Exploring the quality of the service experience: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Advances in services marketing and management (Vol. 4). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Otto, J. E., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (1996). The service experience in tourism. Tourism Management, 17(3), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(96)00003-9

- Pirson, M., Langer, E., Bodner, T., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2012). The development and validation ofthe langer mindfulness scale-enabling a socio-cognitive perspective of mindfulness in organizational contexts. Fordham University Schools of Business Research Paper.

- Rojo-Ramos, J., Gómez-Paniagua, S., Guevara-Pérez, J. C., & García-Unanue, J. (2023). Gender differences in adventure tourists who practice kayaking in extremadura. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(5), 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20053889

- Rubin, S. D., Lee, W., Morris Paris, C., Teye, V., & Morris, C. (2016). The influence of mindfulness on tourists’ emotions, satisfaction and destination loyalty in fiji. Travel and tourism research association: Advancing tourism research globally (Vol. 54). University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://scholarworks. umass.edu/ttra/2011/Visual/54

- Sauer, S., Walach, H., Schmidt, S., Hinterberger, T., Lynch, S., Büssing, A., & Kohls, N. (2013). Assessment_of_mindfulness_review_on state_of_the_art. Mindfulness, 4(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0122-5

- Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1–3), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870496

- Segal, Z. V., Teasdale, J. D., & Williams, J. M. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. A new approach to preventing relapse. The Guilford Press. ISBN 1-57230-706-4.

- Şehirli, M. (2022). An empirical study on the effects of mindfulness, embodied cognition, behavioral intention, and altruism on job satisfaction of employees, customer satisfaction and their repurchase intentions. Current Research in Social Sciences, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.30613/curesosc.1094142

- Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., Thoresen, C., & Plante, T. G. (2011). The moderation of mindfulness‐based stress reduction effects by trait mindfulness: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20761

- Suthatorn, P., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2023). Effects of trust in organizations and trait mindfulness on optimism and perceived stress of flight attendants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personnel Review, 52(3), 882–899. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-06-2021-0396

- Taylor, L. L., & Norman, W. C. (2019). The influence of mindfulness during the travel anticipation phase. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2018.1513627

- Thompson, B. L., & Waltz, J. (2007). Everyday mindfulness and mindfulness meditation: Overlapping constructs or not? Personality and Individual Differences, 43(7), 1875–1885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.017

- Tontini, G., Søilen, K. S., & Silveira, A. (2013). How do interactions of Kano model attributes affect customer satisfaction? An analysis based on psychological foundations. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 24(11–12), 1253–1271. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2013.836790

- UNWTO World Tourism Organization. (2019). UNWTO Tourism Definitions. UNWTO. (Accessed on 5 March 2023). https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420858

- Van Winkle, C. M., & Backman, K. (2008). Examining visitor mindfulness at a cultural event. Event Management, 12(3), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599509789659731

- Vasconcelos, A. M. d., Barichello, R., Lezana, Á., Forcellini, F. A., Ferreira, M. G. G., & Cauchick Miguel, P. A. (2015). Conceptualisation of the service experience by means of a literature review. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 22(7), 1301–1314. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-08-2013-0078