Abstract

This paper aimed to investigate destination selection determinants and revisit intentions of international leisure tourists to southern Ghana. It tested the direct paths between destination selection determinants and revisit intention, and investigated the moderating role of satisfaction in the link between the destination selection determinants and revisit intentions. The paper used a structured questionnaire to gather data from 284 respondents. Tourist sites were purposively selected for the survey to collect data from international leisure tourists. The study’s results revealed a significant and positive relationship between destination selection determinants and revisit intentions. However, the dissection of the destination selection determinants’ constructs into individual components revealed that education/learning and ego enhancement are significant predictors of tourist revisit intentions. Overall, the study contributes to the tourism literature by demonstrating how the destination selection determinants are strengthened by the moderating effect of satisfaction. The study’s implications are pertinent as it reinforces the importance of destination marketing and economic variables as determinants of destination choice. Theoretical contributions arise for scholars, and practical implications are presented for service providers and stakeholders within the tourism sector, particularly, those in southern Ghana.

SUBJECTS:

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Globally, the travel and tourism industry has been described as one of the most vibrant economic generators (Guri et al., Citation2021), making the industry the fastest-growing sector over the last six decades (Fourie & Santana-Gallego, Citation2013). In 2014, for example, the industry influenced employment, exports, and taxes contributed to GDP [US$7.6 (9.8 percent of global GDP)] and created 277 million jobs (1 in 11 jobs) directly or indirectly (Subhajit & Rohit, Citation2017). International tourist arrivals across destinations worldwide were 1.4 billion in 2018, indicating a growth of 6.0% from 2017 (UNWTO., Citation2019). This was the second-highest annual increase since 2010 (UNWTO., Citation2019).

Transitioning economies like Ghana have seen the economic impact of tourism on their economies and have awakened to this new phenomenon (Guri et al., Citation2021). As far back, Erbes (1973) had argued that these transitioning economies see tourism development as a means of providing for all their foreign settlement difficulties. Many African countries have embraced travel and tourism as a panacea to generate foreign income, expand their export frontiers, create employment, and improve economic growth and development (Soliman, Citation2021).

Ghana’s tourism sector has witnessed a commendable increase since 1982, and the country is now the third-leading destination for international tourist arrivals in West Africa after Senegal and The Gambia (World Economic Forum, Citation2019). With its tropical climate and overall low elevation due to the Volta Basin covering almost half of the country’s land area, Ghana attracts many international leisure tourists. Tourism statistics for 2019, for example, was 1,490,000,000, a 49.6% increase from 2018 (GTA, Citation2019). However, tourism in Ghana, as was the case in the rest of the world, was negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (Crossley, Citation2020), which has caused a decline. According to GTA (Citation2019), tourism statistics in 2020 was 191,000,000, an 87.81% decline from 2019. However, with the industry projected to generate $8.3 billion annually with international tourist arrivals of 4.3 million by the end of 2027 (Mohammed et al., Citation2021), it is essential to precisely understand what informs tourists’ decision to choose Ghana as the destination of choice and their revisit intentions.

Destination marketing literature indicates no generally accepted agreement on what influences tourists’ destination choice (Littrell et al., Citation2004). Although there is an assortment of works on the factors that motivate tourists in choosing a destination (Jang et al.,Citation2009; Johann et al.,Citation2016; Perovic et al., Citation2018), there seems to be no known work on the relationship between destination selection determinants and revisit intentions. Furthermore, many travel demand studies have mainly focused on measuring destination image and what motivates consumers to look for different travel options or purchases, rather than the impact of satisfaction on their revisit intention (Wei et al. (Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Academic work in this area has mainly focused on subjects relating to tour memory, warm experience (Gallarza et al., Citation2017), homestay experience (Jamal et al., Citation2011), heritage setting experience (Laing et al., Citation2014), hotel experience (Sørensen & Jensen, Citation2015) tour adventure experience (Prebensen & Xie, Citation2017) all of which collectively enhance the tourist’s intention to revisit (Manosuthi et al., Citation2020). However, how these factors help predict international travelers’ revisit intentions has rarely been studied.

Furthermore, few studies have examined the relationship between domestic holidaymakers’ perceived trust and their intention to revisit a destination (Hassan & Soliman, Citation2021). Still, most of these studies have failed to look at the mediating impact of satisfaction on the destination selection determinants and revisit intention. Therefore, it is hard to find tourism marketing and management researchers that systematically analyze the interrelationships between destination selection determinants, satisfaction, and revisit intentions (Bayih & Singh, Citation2020). As a result, this paper aims to fill these gaps by examining destination selection determinants and revisit intentions of international leisure tourists to Ghana. More specifically, the current research aims to: First, “establish the relationship between the Destination Selection Determinants (DSDs) and Revisit Intentions (RIs)”; Second, “it will examine the extent to which tourists’ motivations influence satisfaction”, and third, “assess the mediating role of satisfaction on destination selection determinants and revisit intentions”.

The study will make a relevant contribution by: first, offering a clear picture of what influences leisure tourists’ visit to southern Ghana and exploring theoretical approaches and empirical evidence on the underlying relationship among the destination selection determinants, satisfaction, and revisit intention. Second, despite the growing body of work on tourists’ motivation in choosing a destination, little is known about the extent to which tourists’ motivation influence satisfaction leading to revisit intention in Ghana. Hence, this study takes a novel step to bridge this gap through a mediation effect in the conceptual model developed. The insights obtained will help service providers elevate tourists’ satisfaction thereby influencing their repeat visit intentions. Third, it develops a structural framework to address the question of whether or not and how the destination selection determinants influence the revisit intentions of international leisure tourists to southern Ghana. Fourth, the destination loyalty model by Yoon and Uysal (Citation2005) will be validated in the context of a transitioning economy compared to Northern Cyprus, the Mediterranean region where the original model was developed.

For a destination like Ghana seeking to attract more tourists, this study will be important to the travel and hospitality industry for several reasons: Firstly, Ghana has positioned tourism to be part of government policy. The sector has received much support for economic expansion at the regional, national, and international levels (Amissah, Citation2013). Secondly, tourism development in Ghana since 1989 has been at the centre stage of the government’s policy framework, including the 15-year National Tourism Development plan, among others (Amissah, Citation2013); hence this study will provide a framework for tour operators and other Destination Marketing Organizations to develop tour programs that specifically meet the needs of these international leisure tourists.

2. Literature review

2.1. Travel motivation

Travel motivation in academic literature has been a central focus of tourism research, as it is perceived as one of the key ways of understanding travel needs and tourist behaviour at a destination (Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005, Prayag, Citation2012). Various disciplines explain motivation from different perspectives (Çelik & Dedeoğlu, Citation2019). Psychology and sociology, for example, define motivation through emotional and cognitive or internal/external motives. In contrast, anthropology defines it as “going away from the routine environment and seeking authentic experiences” (Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005, p. 46). Make (Citation2014) defined it as one of psychological factors that govern consumers’ buying behaviour. They believe that motivation is key in reaching the highest intensity, creates tension, and can propel a person to either minimise or avoid tension.

On the other hand, Pearce et al. (Citation1998 cited in Malviya, Citation2005, p. 48) defined tourist motivation as “the global integrating network of biological and cultural forces which gives value and direction to travel choices, behavior, and experience”. As motivation can be a driver to revisit intentions and influence the buying choices of tourists with regard to their preferences, there is a need to research the motives of travellers (Bayih & Singh, Citation2020). Several studies conducted on travel motivation suggest that understanding the travel’s motive is central to destination expansion and growth. According to Bayih and Singh (Citation2020), there have been different research conducted in this area such as Pearce (Citation2005) and Um and Crompton (Citation1990) who generally agree with the fact that tourists’ visit patterns are the results of a destinations choice process influenced by tourists motives

Travel motivation essentially attempts to understand why tourists travel to certain places or destinations (Wijaya et al., Citation2018). It acts as the basis for understanding why tourists behave in certain ways, as it reflects the intrinsic needs of each individual and how they arrive at a destination to visit. A review of the literature on tourist motivations for visiting destinations presents several common broad factors including novelty seeking (Rittichainuwat et al., Citation2008; Ooi & Laing, Citation2010), search for cultural experience (Amuquandoh, Citation2011; Kim et al., Citation2009), ego enhancement (MacCannell, Citation2002; Wheeller, Citation1993, Citation1994; Citation2007), escape from routine environments (Mak et al., Citation2009; Niggel & Benson, Citation2007; Prayag & Ryan, Citation2010), rest and relaxation (Hsu et al., Citation2010; Jonsson & Devonish, 2008) and education/learning (Dayour, Citation2013; Grimm & Needham, Citation2012; Park & Yoon, Citation2009; Yoo et al., Citation2018). Dann (Citation1977) has concisely captured these motivational factors as push-pull factors.

For tourism destination marketers, it is important to know what major motivators drive tourists to travel. Since the paradigm of tourism is always related to human beings and human nature, it is a complex proposition to investigate why people travel and what they want to enjoy (Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005). Research in tourism marketing has identified a wide variety of motivators ranging from the physical characteristics of the desired destination areas, such as natural landscape, and local people and culture, to psychologically-based motivations like an escape from routine and rest and relaxation (Chiang & Jogaratnam, Citation2006).

2.2. Push & pull travel motivation theory

In tourism research, the travel motivation concept can be classified into two forces, which indicate that people travel because they are pushed and pulled to do so by “some forces” or factors (Dann, Citation1977, Citation1981). Uysal and Hagan (Citation1993) posit that these forces lucidly describe how individuals are pushed by motivation variables into making travel decisions and are pulled or attracted by destination offerings.

Several theories have been developed and research works carried out to explain travel motivation since tourists are from different countries, cultures, and characteristics. Maslow’s hierarchy of motivation is widely acknowledged as one of the most commonly applied theories to explain tourist motivation to travel. It was modelled as a pyramid consisting of the physiological needs as the most basic need, existing at the bottom ladder of the hierarchy. This was followed by higher levels of psychological needs and topped by the need for self-actualization (Wijaya et al., Citation2018). The theory was critiqued because of the prepotency assumption. Unless lower-level needs are satisfied, the inquiry to satisfy higher-level needs would not exist. Human needs will not necessarily follow the order of the pyramid (Hsu et al., Citation2007). The seminal work of Iso-Ahola (Citation1980, Citation1982, Citation1983) also proposed that seeking (intrinsic rewards) and escaping (free from routine) are two major reasons explaining why people travel or take leisure activities. The two factors are broken down into four: personal escape, personal seeking, interpersonal escape, and interpersonal seeking. The critique of Iso-Ahola is the ignorance of the biological aspect of tourists where some segments, for instance, the older people, a biological factor may become a determinant in shaping an individual motivation to travel (Hsu et al., Citation2007).

Dann’s (Citation1977) push and pull motivation theory is the most widely adopted theory in many studies examining traveller motivation (Baniya et al., Citation2017; Prayag, Citation2012). Push factors are defined by Jang et al. (Citation2009) as the socio-psychological needs that predispose a person to travel and pull factors are the ones that attract the person to a specific destination after push motivation has been initiated. Push factors relate to travellers internal needs and preferences such as ego-enhancement, self-esteem, knowledge-seeking, relaxation, and socialization (Jang & Wu, Citation2006).

According to Bayih and Singh (Citation2020), the push factors are used to explain the desire to travel for vacation, while pull factors are essential for explaining the choice of destination by travellers. It is worth noting that, Dann (Citation1977) explained the integration of both factors as push factors are the antecedents to that pull factors. Albughuli (Citation2011) further explained that the push factors are widely understood as internal factors whereas, the pull factors are features of the destination that appeal to a tourist to choose a particular destination. As the nature of this study is exploratory and undertaken within the context of a developing country of Ghana with a specific focus on some selected tour sites, Dann’s (Citation1977) push and pull motivation constructs were therefore considered the most relevant motivational theory for accomplishing this empirical work.

2.3. Tourists satisfaction

Tourism literature posits that tourists’ assessment of their travelling experience begins from the cognitive evaluation of their encounter with the attributes at a destination (Sharma & Nayak, Citation2019). Hence, the role of destination management organizations (DMOs) is to provide attributes that speak to the specific needs of tourists to make their tours memorable (Jing & Rashid, Citation2018) and to attract repeat visits or purchases. In the tourism context, satisfaction basically stands for the function of pre-visit expectations and post-visit encounters Asmelash & Kumar, Citation2019). Pizam, Neumann, and Reichel (Citation1978, p. 317) define tourist satisfaction as “a collection of tourists’ attitudes about specific domains in their vacation experience”. Oliver (Citation1997) defines tourist satisfaction as a judgment that a product or service feature, or the product or service itself, provided a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfilment, including over and under-fulfillment.

In a study conducted by Ragavan et al. (Citation2014) and Valduga et al. (Citation2020), they determined tourist perception and satisfaction towards a tourist destination by assessing numerous destination attributes involving accommodations and foods, attractions, climate and image, products, accessibility, culture, communities, and price. Vengesayi et al. (2010) also argued that destinations rely on attractiveness to satisfy tourists. According to Asmelash & Kumar (Citation2019), tourist satisfaction levels are significantly affected by destination attributes. In other words, if tourists are pleased with the attributes of the destination and meet their expectations, it can be expected that their satisfaction levels will be high. On the other hand, if the destination’s performance and attributes do not meet the needs or expectations of the tourist, will be dissatisfied.

Similarly, Liu et al. (Citation2016) found that tourists’ dissatisfaction at a destination or an attraction may attract tourists negative emotions which will cause them to complain, switch and give negative word-of-mouth (WOM) communication about the destination. Thus, tourists’ positive emotions significantly impact tourist satisfaction, and negative emotions directly affect the search for alternatives (Asmelash & Kumar, Citation2019). A study conducted by Bigne et al. (2001) revealed that when tourists are willing to share their experience about a destination with their friends and family, their intention to revisit is an indication of their satisfaction with the destination. In most cases, destination attributes like the quality of the accommodation, accessibility of the destination, beautiful scenery, weather conditions or climate, and neatness are considered important attributes for a tourist’s overall satisfaction (Som et al., Citation2012). If the general service provided to tourists that visit goes beyond or meets their expectations, then tourists will be satisfied. If not, the tourist will be dissatisfied and may not return to the destination or recommend it to others. Therefore, tourists’ revisit intention is influenced by satisfaction with the attributes of the destination.

2.4. Revisit intentions

Tourists’ perception of a holiday destination can either facilitate its success or failure (Formica, Citation2002; Kozak & Rimmington, Citation2000). It is worth noting that loyal tourists indirectly play the role of ‘‘information channels that informally link networks of friends, relatives, and other potential travellers to a destination’’ (Reid & Reid, Citation1993, p. 3). There exists, therefore, a clear distinction between first-time and repeat visitors (Oppermann, Citation1997), as a result, there is a need for research to focus on modelling a repeat destination choice process with the same robustness as modelling a first-time destination choice process (Um et al., Citation2006).

According to Chen and Tsai (Citation2007), revisit intentions are the assessment of a visitor about the possibility of revisiting the same destination or the willingness of recommending the destination to others. McKercher and Wong (Citation2004) believe that repeat visitors are tourists whose expectations are based on previous experiences. Previous research suggests that tourists less satisfied with the offerings are the destination repeaters (McKercher & Wong, Citation2004), and have a stronger intention not to revisit in the future (Petrick & Backman, Citation2002; Sönmez & Graefe, Citation1998).

Understanding the attributes that make a destination attractive can assist destination management organizations (DMOs) in identifying what attracts tourists to return to a holiday destination (Um et al., Citation2006). Tourists appear willing to spend more if they perceive the service quality to be high and are more likely to make a repeat visit if their expectations are fulfilled (Yang et al., Citation2022). The high value that tourists place on their experience of a holiday destination can also influence their return to the destination (Capon et al., Citation1990). It is likely that repeat visitors enjoy a holiday destination for either (or both) aesthetic reasons (sentimentality, memory, a sense of belonging) or utilitarian reasons (better knowledge of the geographic area for selected activities) (Li et al., Citation2008).

In terms of destination management and development, the aim of DMOs is to understand the factors that influence tourists to revisit, as it is cost-effective to retain existing tourists in comparison with attracting new ones (Rajput & Gahfoor, Citation2020). According to Bayih and Singh (Citation2020), destination managers measure their success based on tourists’ ability to share positive word of mouth about their experience during their visit and their willingness to recommend the destination to others. Their intention to revisit and recommend it to others reflects the behavioral intention of tourists and tourist loyalty (Quintal & Polczynski, Citation2010).

Willingness to recommend, also known as word-of-mouth communication refers to customers’ intention to share their experiences with their friends and relatives (Maxham, Citation2001). Tourist behavioural intention (revisits and recommendations) may often be affected by several variables ranging from the perceived attractiveness of the destination (Um et al., Citation2006) to the real destination attributes (Ngoc & Trinh, Citation2015). Moreover, the destination’s offering, perceived quality, motivation, and visitor satisfaction may predict future tourist behavior (Elgammal & Ghanem, Citation2016).

2.5. Relationships between the destination selection determinants and revisit intentions

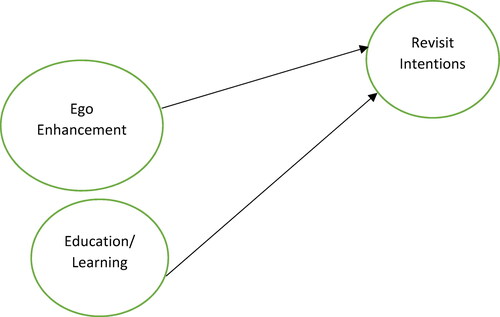

In the process of reviewing past studies, six (6) hypothesized relationships were developed. The Destination Selection Determinants (DSDs) had six constructs (novelty seeking, cultural experience, ego enhancement, escape, education/learning, rest and relaxation) which were tested with revisit intentions. The path relationships connect the constructs in the DSDs to revisit intentions. Tourist motivation to choose a destination to visit, whether pushed or pulled by the attributes of the destination are antecedents of tourist’s satisfaction and revisit intentions (Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005). More specifically, the DSDs have a positive relationship with and tourists revisit intentions (Khuong & Ha, Citation2014). Nevertheless, the study revealed that the direct relationships between novelty seeking and revisit intentions, cultural experience and revisit intentions, escape and revisit intentions, and rest and relaxation and revisit intentions were all left unsupported. Contrary to this, both the direct relationship between ego enhancement and revisit intention and education/learning and revisit intentions were supported.

Moreover, some empirical findings on the DSDs and tourist revisit intentions are highly paradoxical (Bayih & Singh, Citation2020). For instance, a study by Khuong and Ha (Citation2014) revealed that DSDs have a positive direct and indirect relationship with revisit intention. Conversely, the findings of Huang and Hsu (2009) did not exhibit significant relations between satisfaction and tourist revisit intentions. Therefore, literature has no consensus regarding the direct and indirect relationships between DSDs, satisfaction, and tourist revisit intentions (Bayih & Singh, Citation2020). Such inconsistent results of prior studies and the absence of structural investigations on the aforementioned constructs in the perspectives of a transitioning economy like Ghana are the motivations for this current research.

2.6. Conceptual framework

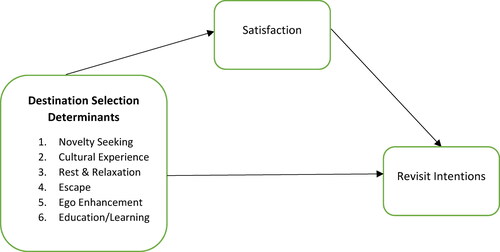

A conceptual framework by Yoon and Uysal (Citation2005) was adapted to guide this study (). The framework was found appropriate because it provides some key variables relevant to the study. The basic argument advanced by the proponents is that tourist visitation to a destination is a function of the push and pull factors. Accordingly, the push forces constitute the internal emotional desires of the tourist including novelty seeking, cultural experience, escape, and relaxation, among others, whereas the pull factors are those forces that define the tourist choice of a destination (e.g. scenery, cities, climate, wildlife, and historical and local cultural attractions). They are largely destination-specific enticing elements. Therefore, the two generic factors collectively explain why a person would want to embark on a trip, and where he or she would go to satisfy this need. Consequently, just like a product, whenever tourists are satisfied with the travel experience in a particular destination, it has both short-run and the-run behavioural effects, such as revisit intentions (Hutchinson et al., Citation2009; Santouridis & Trivellas, Citation2010).

Figure 1. Framework on tourists’ motivations and revisit intentions. Source: Adapted from Yoon and Uysal (Citation2005).

3. Research methods

3.1. Study setting

The survey was conducted on international leisure tourists who visited Accra, Cape Coast, Elmina, Assin Manso, and Manhyia Palace Museum. The area in which the study was conducted is made up of three (3) regions (Greater Accra Region, the Ashanti Region, and the Central Region all within southern Ghana) which are part of the sixteen (16) administrative regions of Ghana.

Ghana, formerly the Gold Coast, made history in 1957 when it became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to be liberated from British dominance and has since espoused a decentralized planning system influenced by the British Colonial model. It is located in West Africa, bordered to the north by Burkina Faso, east by Togo, west by Cote d’Ivoire, and south by the Gulf of Guinea. The climatic condition in Ghana is tropical with a temperature between 21-32 °C (70-90 °F). There are two main seasons in Ghana – the rainy season and the dry season.

Ghana is a destination known for cultural, heritage, and historical tourism. The two regions selected for the study are home to an array of ecological, cultural, and historical attractions, such as the Kakum National Park, the Cape Coast and Elmina castles, the Dutch Cemetery, Posuban Shrines, Fort St. Jago, Assin Manso Slave River, Manhyia Palace, and Military Museums, Kejetia Market, Okomfo Anokye Sword, Kumasi Cultural Centre, and Adanwomase Kente Weaving Village among others.

The Greater Accra Region is the smallest of all Ghana’s sixteen (16) administrative regions in terms of size, and the second most densely populated region after the Ashanti Region. It is the most urbanized region in the country, with 87.4% of its total population living in an urban centre, Accra is both the capital town of the region and Ghana (visitghana.com). The region has two metropolitan areas, Accra and Tema (Port City). The Ashanti Region on the other hand occupies a central portion of Ghana and is a hub of Asante history and culture. It is the largest city and Kumasi is the capital. The region is well known for its opulence in Gold and cocoa production. The Central Region of Ghana features two monstrous slave castles in Elmina and Cape Coast and is known for its higher education institutions and an economy sustained by abundant industrial minerals and fishing (visitghana.com). Cape Coast is the region’s capital and was Ghana’s first capital city till 1877 when the British moved it to Accra.

These regions are noted for heritage, historical and cultural tourism. It is heavily endowed with unique cultural attributes such as traditional cultural drumming and dancing, festivals, and architecture, which are different from Northern Ghana. To a large extent the destination attracts considerably high numbers of tourist arrivals each year (GTA, 2013).

3.2. Research population

The study was conducted on international tourists who visited Accra, Cape Coast, Elmina, and Kumasi (all within the southernmost part of Ghana). The justification for targeting international tourists is that they might be visiting the region for a special reason, given that they are nationals from other countries outside Ghana. According to Afro Tourism (Citation2019), many international tourists that visit southern Ghana, visit attractions in the Greater Accra Region, Central Region of Ghana, and the Ashanti Region. The sampling frame for the survey was described to include international leisure tourists that visited these regions. This frame restricts itself to the Greater Accra, Central and Ashanti Regions of Ghana, assuming that more than 50% of international tourists visit these regions. This argument is not meant to disregard domestic tourists’ motivations for visiting these areas, but non-citizens may have some peculiar reasons for visiting the unknown, which are worth exploring, hence the rationale for the choice. According to GTA (2014), international tourists’ arrivals to Ghana for business purposes, visiting family and friends, and for holidays was 66.7%. The 2014 accommodation data indicated that 41,331 rooms were booked from these regions (2,570 international tourists) accounting for 45,507 beds from tourists arriving in these three regions of Ghana (Ghana Tourism Authority, 2014)

3.3. Sampling and data collection

The data collection lasted for three (3) months at the eight (8) main attractions located within the three (3) selected regions of Ghana (between March and June 2019) using a convenient sampling method. This sampling method was chosen by the researchers as they do not have access to the sampling frame of these tourists visiting southern Ghana; hence questionnaires were administered to tourists who were available at these tourist sites and willing to participate in the study. The purpose of the study was explained to them and those willing to participate in the study were handed over the questionnaire. Measurement statements were prepared in survey format due to the literature review, and expert opinions were collected by the researchers. This is because it will allow the researchers to gain better and greater insight into the tourists and the subject of interest. Tourists can share or demonstrate their knowledge of perspectives about the topic.

The researchers completed the questionnaire face-to-face at the eight tour sites - Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum, Christiansborg Castle, James Town Boutique, Kakum National Park, Cape Coast Castle, Elmina Castle, Assin Manso Slave River, and Manhyia Palace Museum. These eight (8) tourist attractions, to a very large extent, are the most visited tourist attractions in these three regions (GTA, 2013). Tourists having joined a tour at these attractions were asked at the end of their tour to answer the questions included in the scale. Researchers were assisted by the onsite tour guide(s) in distributing the questionnaires to tourists. Questionnaires that were administered by tourists while the researchers were around were collected. There were tourist sites where questionnaires were left behind for tourists to administer, which were later collected by researchers.

The attractions were covered successively one month apart from each other. This was a control for double counting since tourists spend time in these cities or towns, and their average stay is 12 days or less. This is due to the different tour packages designed by key tour operators such as Apstar Tours Limited, Land Tours, Sun Seekers, Cool Trips & Tours, Continent Tours, and Ashanti Africa Tours, to mention a few for both solo travellers and those travelling in the environmental bubble. Moreover, tourists that visited these sites were asked if they had previously been interviewed on the same subject .

Table 1. Data collection process.

The adopted approach to data collection was a questionnaire. This was because the target audience was mostly literate and could read and write in English. The questionnaire was divided into two sections as follows: the first part captured the background characteristics of the respondents, such as sex, age, employment status, how tourists arrived in the country, where they heard about the destination, and whether this was their first visit to the destination. The second section examined tourists’ motivations (measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from agree to disagree) for travelling to the destination, using measurement items adapted from previous studies.

The instrument for data collection was pretested in Accra on 20 tourists to validate it. The goal of the pilot testing was to ensure that there was no problem with the questionnaire before implementing it. The essence was to examine the validity of each question as to whether the questions captured the information intended to be measured. This exercise resulted in the removal and rewording of some questions and statements that were irrelevant or ambiguous. Regarding the sample size, as proposed by Roscoe (Citation1975 cited in Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016), the rules of thumb for determining sample size are that sample sizes of more than 30 and less than 500 are appropriate. A total of 310 questionnaires were received, of which two hundred and eighty-five (285) were useable. Twenty-five (25) questionnaires (6%) are unusable due to incomplete responses.

3.4. Data analysis

The returned questionnaires were observed and checked for their appropriateness. Then the questionnaire was coded, and data entry was conducted using the Statistical Product for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 20). Data preparation was conducted before moving to the data analysis process. In this process, the entered data was screened for the availability of missing data, outliers, and erroneously filled data. The Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to explore the main factor solutions or dimensions that explain international tourists’ motivations for travelling to these tourist sites located in southern Ghana. The reliability of the scale was tested using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Furthermore, the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression technique was used to estimate the influence of tourists’ motivations on their overall satisfaction. Likewise, the Binary Logistic regression was used to test the influence of tourists’ satisfaction on their revisit intention to Ghana.

4. Results

4.1. Background characteristics of respondents

The study results indicated that most of the respondents (50.7%) were between the ages of 21–30 years. The second item on the demographic variable was gender. The survey outcome revealed that majority of the respondents were female, representing fifty-eight-point five per cent (58.5%).

The study intended to identify the respondents’ country of origin. The study’s outcome destination was from the USA, with a percentage of 67.3%, and the lowest, at 0.7% was from Nigeria. The rest of the tourists were from the UK, Germany, Spain, and other countries not mentioned above. This represented 15.5%, 12%, 2.8%, and 1.8%, respectively. The study indicated that 94% of the respondents arrived at the destination by air, with the remaining 6% by road. The tourists that visited got to know about the destination through various means. The outcome of the study revealed that 51.1% of the tourists got to know about the destination through the internet, tourists who already knew about the destination represented 34.9%, those that got to know about it through family and friends represented 9.3% of the total number of respondents, 2.8% knew about the destination through books and guides, while 2.1% represented a portion of the respondents that got to know about the destination through other means. This, therefore, represents a fair share of tourists’ knowledge about the destination.

4.2. Descriptive statistics and tests of normality

The table below shows the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the survey instrument. They indicate the extent to which the respondents disagreed or agreed with the questionnaire statements and indicate how each statement performed from the respondent’s point of view. The 33 variables displayed in below represented the components of the eight main constructs depicted in the conceptual framework for the study: Satisfaction (SS), Revisit Intentions (RI), Novelty Seeking (NS), Cultural Experience (CE), Escape (EP), Rest & Relaxation (RR), Ego Enhancement (EE), and Education/Learning (EL).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and test of normality of variables.

4.3. Exploratory factor analysis

The 33 items used for the scales on the conceptual constructs were factor analyzed and subjected to principal components analysis (PCA) using SPSS version 22. Before performing PCA, the suitability of data for factor analysis was assessed. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.957, exceeding the recommended value of 0.6 (Kaiser, Citation1970) and the Bartletts Test of Sphericity (Bartlett, Citation1954) reached statistical significance (Approx.: Chi-square= 7958.412, df. 528, sig. 0.000). This confirms that there was a significant correlation among the variables. Thus, factor analysis was appropriate.

4.4. Measurement model

An initial output generated from the AMOS software revealed some unfit indices (see below). As a result, there was a need for modifications and further purifications (Kline, Citation2015). It is strongly suggested that theory and content should always be considered in model modifications. In a parallel vein, Hair et al. (Citation2010, p. 713) stated that “the most common change would be the deletion of an item that does not perform well with respect to the model integrity, model fit, or construct validity”.

Table 3. Improvement in fit of measurement research model.

Consequently, the original measurement model was then subjected to modification according to the sizes of factor loadings, cross-loadings, measurement errors, and the correlation between measurement errors. With reference to this study, the AMOS software output suggested modification of some items via stage-by-stage deletion/re-specifications of some weak variables. However, the re-specifications were not theoretically coherent and could result in the danger of empirical modifications without theoretical justifications (Hair et al., Citation2014). As a result, scale items were dropped/deleted systematically to ensure that the deletion of each item was necessary.

During the modification (phase II) of the original unfitted model, two items were deleted from Novel Seeking, two items from Cultural Experience, one item from Ego Enhancement, one item from Escape, two items from Rest & Relaxation, two times from Satisfaction, two items from Education/Learning and one item from Revisit Intentions. Thus, thirteen (13) items were eliminated after the CFA, leaving the new purified constructs with 20 items that provided the best-fit indices. below presents the improvement of the goodness-of-fit indexes due to modifications to the measurement model.

4.5. Validity and reliability of final measurement model

The reliability measures in this study are above the acceptable satisfactory levels (Cronbach’s alphas > .70, Average Variance Extracted > .50, composite reliability > .70) as recommended by scholars (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Nunnally, Citation1978; Vandenbosch, Citation1996). Furthermore, the factor loadings showed good convergent validity. The final measurement model’s resulting validity and reliability indicators are displayed in below.

Table 4. Validity and reliability results for CFA final measurement model.

below shows that the squares of the correlations of the individual constructs were less than the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), indicating its support for discriminatory validity. Several studies have validated this approach and certified that, in the assessment of the discriminant validity, each construct’s AVE must be compared with the squared correlations between each pair of variables. Segars (Citation1997) and Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) indicate that AVE’s, greater than any squared correlation, suggests that discriminant validity has been achieved.

4.6. Influence of satisfaction on revisit intention

The study hypothesized a relationship between destination selection determinants and revisit intentions. Six hypotheses were set and all of them were analyzed. The first analysis looked at all the direct relationships between Destination Selection Determinants (DSDs) and revisit intentions (RIs), followed by individual dimensions of the determinants of Satisfaction.

The above table highlights the direct relationship between the conceptualized DSDs and RIs. The results suggest that the direct relationship between DSDs and RIs on tourist visits to Ghana is very strong, as indicated in .

Table 5. Hypothesized relationship.

H3 and H5 were all statistically significant in predicting that the ability to learn about a destination offering and the prestige that comes with visiting the destination are key determinants for why tourists visit Ghana. This suggests that the two conceptualized dimensions of DSDs can significantly influence RIs. The beta estimates of DSD constructs indicate Education/Learning (β = 0.84) as the most influential factor in predicting the revisit intentions of tourists to Ghana. The path diagram of the direct relationship between DSDs and RIs is represented in below:

4.7. Mediation effect of satisfaction on revisit intention

The study also sought to assess the mediating effect of satisfaction between DSDs and RIs. The table below presents the full details of the mediation effect of the proposed framework:

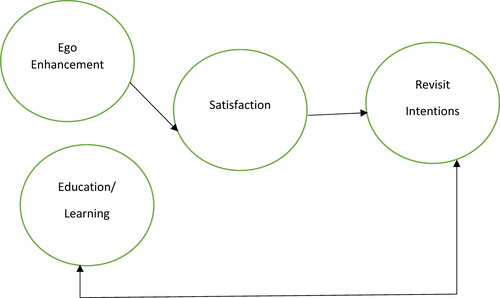

As indicated in , using bootstrapping, DSDs achieved no mediation with satisfaction to influence revisit intentions. The disentanglement of the DSDs into six dimensions also produced two mediation effects with satisfaction influencing revisit intentions. Education/Learning dimensions of the conceptualized DSDs model for this study achieved full mediation effect with satisfaction to influence DSDs on RIs by tourists that visit destination Ghana. On the other hand, ego enhancement achieved no mediation with satisfaction to influence DSDs on RIs. This is highlighted in .

Table 6. Mediation effect

5. Discussion

The study examined DSDs and RIs on international leisure tourists. We attempted to analyze key determinants of tourists’ visits to a tourism destination and tested the mediating role of satisfaction between the DSDs and RIs of international leisure tourists. The major results found from the study have been deliberated upon with regard to previous literature on the subject/themes under discussion.

The study showed a significant relationship between DSDs and RIs of tourists that selected Ghana as their preferred destination. The study’s result indicated that DSDs are the underlying factors that define tourist motivation to visit a destination. From this perspective, Çelik and Dedeoğlu (Citation2019) found that individuals visiting cultural destinations to experience the attributes of the destination have underlying factors that motivate them to embark on such trips. Therefore, it was indicated in their study that tourists that travel for relaxation for example may prefer rather calm and relaxing destinations or environments.

The study also assessed the mediating role of satisfaction on DSDs and RIs. The study pointed out that the dissection of the constructs of the DSDs into individual components revealed that education/learning and ego enhancement are major predictors of tourist revisit intentions. Education/Learning manifested as one of the predictors of tourist satisfaction due to the tangible and intangible manifestations of the destination demonstrating the ability to offer tourists the opportunity to explore and experience new things. According to Jarvis and Peel (Citation2008), tourists that travel for educational purposes fulfil their desire to travel through a socially legitimate travel motivation. An Australian study also found that this group of tourists, accounting for about 29% of the total nights spent in the destination, contributed an estimated $3 billion per year to the Australian economy (Jarvis & Peel, Citation2008). Evidence from the study revealed, most of the respondents who took part in the survey believed that education or visiting to learn about a new destination influences tourist selection of a destination and their revisit intentions. The partial nature of satisfaction mediating between DSDs and RIs concerning tourists that visit Ghana reinforced this assertion and can be considered a destination marketing strategy.

To further assess the significance of satisfaction mediating between DSDs and RIs, Chi and Qu (Citation2008) and Santouridis and Trivellas (Citation2010) believed that satisfaction is an important component of revisit intentions. Similarly, previous studies have also suggested that when tourists’ holiday expectations are met or exceeded at the destination visited, they are more likely to return in the future or recommend the destination to their friends and family (Chen & Tsai, Citation2007; Oliver, Citation2010). For instance, Chi and Qu (Citation2008) and Santouridis and Trivellas (Citation2010), observed that overall satisfaction with travel experience is a major antecedent of revisit intention. Based on these findings, this study suggests that satisfaction with trip experience would positively influence tourists’ revisit intention to Ghana.

6. Conclusion

This research examined DSDs and RIs on international leisure tourists’ visits to Ghana. Based on the literature reviewed, hypotheses were developed to test the effect of DSDs on RIs on international leisure tourists. Six constructs were tested - novelty seeking, cultural experience, ego enhancement, escape, education/learning, and rest & relaxation as a result of the literature reviewed. The study also sought to assess the mediating effect of satisfaction between DSDs and RIs. The disentanglement of the DSDs into six dimensions also produced two mediation effects with satisfaction influencing revisit intentions. Education/Learning dimensions of the conceptualized DSDs model for the study achieved full mediation effect with satisfaction to influence DSDs on RIs by tourists that chose Ghana as their preferred destination.

To summarise, this study suggests that the DSDs are the major antecedents of satisfaction, revisit intentions, and recommendation readiness of international leisure tourists to southern Ghana. In this study satisfaction positively significantly predicted revisit intention. On the other hand, the DSDs strongly and positively influenced willingness to recommend and revisit intentions. Therefore, it can be concluded that the attributes of destinations are the most important variables that influence international leisure tourists’ satisfaction with their travel experiences and destination revisit intentions. International leisure tourists’ revisit intentions were more strongly influenced by extrinsic motives than their intrinsic motives and overall satisfaction. This empirical finding is in harmony with a prior study (Um et al., Citation2006) in the cases of international pleasure tourists in Hong Kong.

This study adds to tourism destination marketing literature by elucidating international leisure tourists’ motivation in visiting an emerging economy like Ghana. This research found that DSDs have a positive and significant impact on tourists’ revisit intention which has a positive implication for the Ghanaian tourism industry. The study concluded that satisfied tourists are more likely to revisit. It is, therefore, imperative for service providers in whatever capacity, to ensure that tourists are satisfied with the destinations offering to generate repeat visits.

7. Theoretical implication

Tourists’ motivation is a concept that has been widely researched for decades. Most of these studies have focused on measuring destination image (Khan et al., 2017), ascertaining what motivates consumers in looking for different travel options or purchases (Dayour, Citation2013) with few of these studies addressing the travel demand factors from the perspective of international leisure tourists within the context of a transitioning economy. The study aims to contribute to the existing knowledge by ascertaining the travel motivation behind international leisure tourists’ choice of a destination and the impact on revisit intention.

In attempting to address the objectives of the study, previous literature on travel motivation, push and pull motivation theory, tourist satisfaction, revisit intention, and the relationship between the DSDs and RIs (Buhalis, Citation2000; Lam et al., Citation2004; Prayag, Citation2012; Santouridis & Trivellas, Citation2010; Sirakaya & Woodside, Citation2005; Weaver et al., Citation1994; Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005; Zeithaml et al., Citation1996) were extensively reviewed. From the critical review of literature, some major factors of DSDs and their impact on RIs and tourist satisfaction intents at a destination were drawn. As a result, the study’s primary contribution is as follows:

First, a conceptual framework was developed to address the question of whether or not and how the DSDs influence revisit intentions, and hypotheses were formulated and applicable to the study. Second, the study’s context was discussed with respect to the travel industry in Ghana and with a focus on international leisure tourists. Third, the study, in theory, contributed to the literature by shedding light on the motivation of tourists visiting southern Ghana, which previous studies seem to have overlooked, and extended the present literature on the outcomes of the DSDs on how they influence decisions of international leisure travels and revisit intentions.

The destination loyalty model coined by Yoon and Uysal (Citation2005) was very relevant to the study as it has been validated, especially in the context of a developing country. The model has been validated with a different attribute of another destination compared to Northern Cyprus and the Mediterranean region where the original model was developed. Owing to the above, the study concluded that education/learning and ego enhancement are the key factors out of the six constructs that were tested that motivate international leisure tourists visiting Ghana and their revisit intentions. These factors support the model by Dann (Citation1977) and Yoon and Usysal (2005), which explains that tourist motivation to travel is a function of push and pull factors. Therefore, destination marketing organizations and travel agents at the destination need to consider these key dimensions in their bid to market Ghana. Fourth, the study’s are therefore pertinent as it reinforces the importance of destination marketing and economic variables as determinants of destination choice with a specific highlight on international leisure tourists. Thus, it provides managerial guidelines for tourism policymakers and managers specifically those in southern Ghana. Fifth, the theory could lucidly explain international tourist’s motivation in choosing Ghana as a destination, and a framework was developed.

Furthermore, the findings provided empirical evidence which enhanced the understanding of tourist destination selection determinants as significant antecedents in the formation of revisit intentions. Again, through the dissection of the individual constructs that were tested, the study identified education/learning and ego enhancement as the key determinants or variables that motivate international leisure tourists to visit Ghana and influence their revisit intentions. The study has provided a better and deeper understanding of DSDs and what informs the revisit intentions of international leisure tourists to Ghana. These results could enhance destination marketing strategies, and brand equity theory in influencing tourists’ revisit to a destination as satisfaction was tested as a mediator which seems to have been neglected in previous studies (Boakye, Citation2012; Preko, et al., Citation2020).

8. Practical implication

The study has implications for businesses, destination marketers, DMOs, practitioners, Ghana’s Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture, and local tourism officials. The findings of this study appeared to suggest that tourist satisfaction is an important factor for the revisit intention of international leisure tourists. Hence, it is recommended that the elements of what is offered to tourists by tour operators, hoteliers, or organizations that provide ancillary services to cater to the needs of international leisure tourists at the destination must be given critical attention. This requires effective destination planning, marketing, and management.

Moreover, in the post-study conceptual framework for mediation, it has been clearly observed that these DSDs (education/learning and ego enhancements) were the major predictors of international leisure tourist’s overall satisfaction revisit intentions. Therefore, in order to improve the satisfaction of international leisure tourists with their visitation experiences and to advance their revisit intentions, destination managers must improve their storytelling skills by making the destination attractive for people to visit. They must also ensure that they conserve historical, cultural, and natural attractions as these are key attractions visited by these tourists. Tour packages developed by tour operators and other destination promoters must clearly meet the needs of the tourists and influence their revisit intentions. The Ghana Tourism Authority (GTA), which has the mandate of enforcing service quality in the industry should ensure that industry practitioners uphold basic service standards that would contribute positively to visitors’ experiences at the destination, thereby motivating tourists to return to the destination or recommend it to others.

9. Limitations

Like any other study, the current study was conducted under certain limitations. Firstly, the study had a geographical limitation. It only focused on some tourist sites in southern Ghana (Greater Accra, Central Region, and Ashanti Regions of Ghana). This does not give a true reflection of the outcome of the study. Therefore, future research could expand the study’s scope by conducting the study using other geographical locations or perhaps covering the entire country. The demographic factors of respondents were not considered for this study. Factors, such as respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics and travel experience could shape the relationship among DSDs, satisfaction, and revisit intentions, but these factors were considered. Perhaps, better and more reliable results could have been achieved by incorporating the above issues. Therefore, a future study could measure how socio-demographic characteristics and travel experience affect satisfaction. Finally, the study only focused on international leisure tourists. Future studies may look at the same constructs on domestic tourists visiting these sites to see if they will arrive at the same conclusion or influence policies on tourist satisfaction and revisit intentions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen Mahama Braimah

Dr Stephen Mahama Braimah is a senior lecturer at the University of Ghana Business School in the Department of Marketing and Entrepreneurship. Before joining academia, Stephen worked in various senior management capacities for different companies in different industries, such as the petroleum, automobile, shipping, and ICT sectors. Stephen is also an experienced speaker and human capital development consultant. Dr Braimah’s research interests are marketing, service, strategy, branding, tourism, and hospitality.

Emmanuel Nii-Ayi Solomon

Emmanuel Nii-Ayi Solomon is a tourism consultant, poet, and Ghanaian playwright with solid research background and industry experience in the tourism and hospitality space and the Ghanaian creative arts industry. He has developed a career that combines teaching and research while maintaining his interest in tourism destination marketing with a keen interest in telling stories about tourism in Africa. His recent focus is on how to use netnography to examine experiences told through blogs, photography, and social media portals by tourists while combining principles of storytelling. He is also a lecturer at Accra Technical University in the department of marketing.

Robert Ebo Hinson

Professor Robert Ebo Hinson is Pro Vice-Chancellor at the Ghana Communication Technology University and Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Johannesburg.

References

- Afro Tourism. (2019). http://afrotourism.com/travelogue/8-reasons-why-every-tourist-in-ghana-loves-cape-coast/ Accessed on 9th March 2019.

- Albughuli, M. (2011). Exploring motivations and values for domestic travel from an Islamic and Arab standpoint: The case of Saudi Arabia [Master’s thesis]. University of Waterloo

- Amissah, E. F. (2013). Tourist satisfaction with hotel services in Cape Coast and Elmina, Ghana. American Journal of Tourism Management, 2(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.5923/s.tourism.201304.03

- Amuquandoh, F. E. (2011). International tourists’ concerns about traditional foods in Ghana. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 18(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.18.1.1

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Asmelash, A. G., & Kumar, S. (2019). The structural relationship between tourist satisfaction and sustainable heritage tourism development in Tigrai, Ethiopia. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019

- Baniya, R., Ghimire, S., & Phuyal, S. (2017). Push and pull factors and their effects on international tourists’revisit intention to Nepal. The Gaze: Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 8(8), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.3126/gaze.v8i0.17830

- Bartlett, M. S. (1954). A note on the multiplying factors for various χ 2 approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 16(2), 296–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1954.tb00174.x

- Bayih, B. E., & Singh, A. (2020). Modeling domestic tourism: motivations, satisfaction and tourist behavioral intentions. Heliyon, 6(9), e04839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04839

- Boakye, K. A. (2012). Tourists’ views on safety and vulnerability. A study of some selected towns in Ghana. Tourism Management, 33(2), 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.013

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

- Capon, W., Farley, J., & Hoenig, S. (1990). Determinants of financial performance: a meta analysis. Management Science, 36(10), 1143–1159. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.36.10.1143

- Çelik, S., & Dedeoğlu, B. B. (2019). Psychological factors affecting the behavioral intention of the tourist visiting Southeastern Anatolia. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 2(4), 425–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-01-2019-0005

- Chen, C. F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.07.007

- Chi, C. G. Q., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationship of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: an integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

- Chiang, C.-Y., & Jogaratnam, G. (2006). Why do women travel solo for purposes of leisure? Journal of Vacation Marketing, 12(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766706059041

- Crossley, E. (2020). Ecological grief generates desire for environmental healing in tourism after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 536–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759133

- Dann, G. M. (1977). Anomie ego-enhancement and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4(4), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(77)90037-8

- Dann, G. M. (1981). Tourism motivations: An appraisal. Annals of Tourism Research, 8(2), 187–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(81)90082-7

- Dayour, F. (2013). Are backpackers a homogeneous Group? A study of backpackers’ motivations in the Cape Coast-Elmina conurbation, Ghana. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 4(3), 69–94.

- Elgammal, I., & Ghanem, M. M. (2016). Youth week of the Egyptian Universities: An opportunity for promoting domestic tourism. Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, 10(2), 2.

- Erbes, R. (1973). International tourism and the economy of developing countries. OECD.

- Formica, S. (2002). Measuring destination attractiveness: a proposed framework. Journal of American Academy of Business, 1(2), 350–355.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Fourie, J., & Santana-Gallego, M. (2013). The determinants of African tourism. Development Southern Africa, 30(3), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2013.817302

- Gallarza, M. G., Fayos Gardó, T., & Calderón García, H. (2017). Experiential tourist shopping value: adding causality to value dimensions and testing their subjectivity. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(6), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1661

- Ghana Tourism Authority. (2019). Tourist Statistical Fact Sheet on Ghana.

- Ghana Tourism. (2013). http://www.tourismghana.com (Retrieved November 25, 2020).

- Ghana Tourism. (2014). http://www.tourismghana.com.

- Grimm, K. E., & Needham, M. D. (2012). Moving beyond the “I” in motivation attributes and perceptions of conservation volunteer tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 51(4), 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287511418367

- Guri, E. A. I., Osumanu, I. K., & Bonye, S. Z. (2021). Eco-cultural tourism development in Ghana: potentials and expected benefits in the Lawra Municipality. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 19(4), 458–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2020.173709

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2010). SEM: An introduction. Multivariate data analysis. A Global Perspective, 5(6), 629–686.

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling. (PLS-SEM): Sage Publications.

- Hassan, S. B., & Soliman, M. (2021). COVID-19 and repeat visitation: Assessing the role of destination social responsibility, destination reputation, holidaymakers’ trust and fear arousal. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 19, 100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100495

- Hsu, C. H., Cai, L. A., and Li, M. (2010). Expectation, motivation and attitude: A tourist behavioral model. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 282–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509349266

- Hsu, C. H., Cai, L. A., & Wong, K. K. (2007). A model of senior tourism motivations: anecdotes from Beijing and Shanghai. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1262–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.09.015

- Hutchinson, J., Lai, F., & Wang, Y. (2009). Understanding the relationships of quality, value, equity, satisfaction, and behavioural intentions among golf travellers. Tourism Management, 30(2), 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.07.010

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1980). The social psychology of leisure and recreation. WC Brown Co. Publishers.

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1982). Toward a social psychological theory of tourism motivation: a rejoinder. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(2), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(82)90049-4

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1983). Towards a social psychology of recreational travel. Leisure Studies, 2(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614368300390041

- Jamal, S.A., Othman, N.A. and Muhammad, N.N. (2011), “Tourist perceived value in a community-based homestay visit: an investigation into the functional and experiential aspect of value”, Journal of Vacation Marketing, 17(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766710391130

- Jang, S., Bai, B., Hu, C., & Wu, C.-M. E. (2009). Affect, travel motivation, and travel intention: a senior market. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 33(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348008329666

- Jang, S. S., & Wu, C.-M. E. (2006). Seniors’ travel motivation and the influential factors: an examination of Taiwanese seniors. Tourism Management, 27(2), 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.11.006

- Jarvis, J., & Peel, V. (2008). Study Backpackers: Australia’s short-stay international student travelers. In K. I. Hannam, & Ateljevic (Eds.), Back packer tourism: Concepts and profiles (pp. 157–173). Channel View.

- Jing, C. J., & Rashid, B. (2018). Assessing the influence of destination perceived attributes performance on Chinese tourist emotional responses. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Environment Management, 3(11), 59–70.

- Johann, M., Johann, M., Padma, P., & Padma, P. (2016). Benchmarking holiday experience: the case of senior tourists, Benchmarking. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 23(7), 1860–1875. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-04-2015-0038

- Jönsson, C., & Devonish, D. (2008). Does nationality, gender, and age affect travel motivation? A case of visitors to the Caribbean Island of Barbados. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(3–4), 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548400802508499

- Kaiser, H. F. (1970). A second-generation little jiffy. Psychometrika, 35(4), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291817

- Khuong, M. N., & Ha, H. T. T. (2014). The influences of push and pull factors on the international leisure tourists’ return intention to Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam–A mediation analysis of destination satisfaction. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 5(6), 490–496. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJTEF.2014.V5.421

- Kim, Y. G., Eves, A., & Scarles, C. (2009). Building a model of local food consumption on trips and holidays: A grounded theory approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(3), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.11.005

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications.

- Kozak, M., & Rimmington, M. (2000). Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an off season holiday destination. Journal of Travel Research, 38(3), 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003800308

- Laing, J., Wheeler, F., Reeves, K., & Frost, W. (2014). Assessing the experiential value of heritage assets: a case study of a Chinese heritage precinct, Bendigo, Australia. Tourism Management, 40, 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.06.004

- Lam, S. Y., Shankar, V., Erramilli, M. K., & Murthy, B. (2004). Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty, and switching costs: an illustration from a business-to-business service context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070304263330

- Littrell, M. A., Paige, R. C., & Song, K. (2004). Senior travellers: Tourism activities and shopping behaviours. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 10(4), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/135676670401000406

- Li, X., Cheng, C.-K., Kim, H., & Petrick, J. (2008). A systematic comparison of first-time and repeat visitors via a two-phase survey. Tourism Management, 29, 278-93.

- Liu, C. H., Horng, J. S., Chou, S. F., Chen, Y. C., Lin, Y. C., & Zhu, Y. Q. (2016). An empirical examination of the form of relationship between sustainable tourism experiences and satisfaction. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(7), 717–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2015.1068196

- MacCannell, D. (2002). The ego factor in tourism. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(1), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1086/339927

- Mak, A. H., Wong, K. K., & Chang, R. C. (2009). Health or self-indulgence? The motivations and characteristics of Spa-Goers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 11(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.703

- Make, K. B. (2014). Marketing for hospitality and tourism. Pearson Education Limited.

- Malviya, S. (2005). Tourism: Tourism: Policies, Planning and Governance. Gyan Publishing House.

- Manosuthi, N., Lee, J., & Han, H. (2020). Predicting the revisit intention of volunteer tourists using the merged model between the theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(4), 510–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2020.1784364

- Maxham, J. G.III, (2001). Service recovery’s influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 54(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00114-4

- McKercher, B., & Wong, D. Y. (2004). Understanding tourism behavior: Examining the combined effects of prior visitation history and destination status. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268246

- Mohammed, I., Mahmoud, M. A., & Hinson, R. E. (2021). The effect of brand heritage in tourists’ intention to revisit. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(5), 886–904. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-03-2021-0070

- Ngoc, K. M., & Trinh, N. T. (2015). Factors affecting tourists’ return intention towards Vung Tau City, Vietnam-A mediation analysis of destination satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 3(4).

- Niggel, C., & Benson, A. (2007). Exploratory motivation of backpackers: The case of South Africa. Channel View.

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric methods. McGraw-Hill.

- Oliver, R. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. McGraw-Hill.

- Oliver, R. L. (2010). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer (2nd ed.). M.E. Sharpe.

- Ooi, N., & Laing, J. H. (2010). Backpacker tourism: Sustainable and purposeful? Investigating the overlap between backpacker tourism and volunteer tourism motivations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(2), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903395030

- Oppermann, M. (1997). First-time and repeat visitors to New Zealand. Tourism Management, 18(3), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(96)00119-7

- Park, D. B., & Yoon, Y. S. (2009). Segmentation by motivation in rural tourism: A Korean case study. Tourism Management, 30(1), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.03.011

- Pearce, P. L. (2005). Tourist behaviour themes and conceptual schemes. Channel view Publications.

- Pearce, P., Morrison, A. M., & Rutledge, J. L. (1998). Tourism: Bridges across continents. McGraw-Hill.

- Perovic, Ð., Moric, I., Pekovic, S., Stanovcic, T., Roblek, V., & Pejic Bach, M. (2018). The antecedents of tourist repeat visit intention: systemic approach. Kybernetes, 47(9), 1857–1871. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-12-2017-0480

- Petrick, J. F., & Backman, S. J. (2002). An examination of the construct of perceived value for the prediction of golf travelers’ intentions to revisit. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750204100106

- Pizam, A., Neumann, Y., & Reichel, A. (1978). Dimensions of tourist satisfaction with a destination. Annals of Tourism Research, 5(3), 314–322. ‘ https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(78)90115-9

- Prayag, G. (2012). Senior travelers’ motivations and future behavioral intentions: The case of nice. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(7), 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2012.720153

- Prayag, G., & Ryan, C. (2010). The relationship between the push and pull factors of a tourist destination: The role of nationality-an analytical qualitative research approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(2), 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683501003623802

- Prebensen, N., & Xie, J. (2017). Efficacy of co-creation and mastering on perceived value and satisfaction in tourists’ consumption. Tourism Management, 60(Supplement C), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.12.001

- Preko, A., Mohammed, I., & Ameyibor, L. E. K. (2020). Muslim tourist religiosity, perceived values, satisfaction, and loyalty. Tourism Review International, 24(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427220X15845838896341

- Quintal, V. A., & Polczynski, A. (2010). Factors influencing tourists’ revisit intentions. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22(4), 554–578. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851011090565

- Ragavan, N. A., Subramonian, H., & Sharif, S. P. (2014). Tourists’ perceptions of destination travel attributes: An application to international tourists to Kuala Lumpur. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 144, 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.07.309

- Rajput, A., & Gahfoor, R. Z. (2020). Satisfaction and revisit intentions at fast food restaurants. Future Business Journal, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00021-0

- Reid, L., & Reid, S. (1993). Communicating tourism supplier services: building repeat visitor relationships. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 2(2-3), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v02n02_02

- Rittichainuwat, B. N., Qu, H., and Mongkhonvanit, C. (2008). Understanding the motivation of travelers on repeat visits to Thailand. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 14(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766707084216

- Roscoe, J. T. (1975). Fundamental research statistics for the behavioral sciences. XXX.

- Santouridis, I., & Trivellas, P. (2010). Investigating the impact of service quality and customer satisfaction on customer loyalty in mobile telephony in Greece. The TQM Journal, 22(3), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542731011035550

- Segars, A. H. (1997). Assessing the unidimensionality of measurement: A paradigm and illustration within the context of information systems research. Omega, 25(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-0483(96)00051-5

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Printer Trento Srl.

- Sharma, P., & Nayak, J. K. (2019). Understanding memorable tourism experiences as the determinants of tourists’ behaviour. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 504–518. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2278

- Sirakaya, E., & Woodside, A. G. (2005). Building and testing theories of decision making by travellers. Tourism Management, 26(6), 815–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.05.004

- Soliman, M. (2021). Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict tourism destination revisit intention. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 22(5), 524–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2019.1692755

- Som, A. P. M., Marzuki, A., & Yousefi, M. (2012). Factors influencing visitors’ revisit behavioral intentions: A case study of Sabah, Malaysia. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 4(4), 39.

- Sönmez, S. F., & Graefe, A. R. (1998). Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Annals of tourism research, 25(1), 112-144.

- Sørensen, F., & Jensen, J. F. (2015). Value creation and knowledge development in tourism experience encounters. Tourism Management, 46, 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.07.009

- Subhajit, B., & Rohit, K. V. (2017). Modeling tourists’ opinions using RIDIT analysis. In Handbook of research on holistic optimization techniques in the hospitality, tourism, and travel industry (pp. 423-443). IGI Global.

- Um, S., Chon, K., & Ro, Y. H. (2006). Antecedents of revisit intention. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(4), 1141–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2006.06.003

- Um, S., & Crompton, J. L. (1990). Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(3), 432–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(90)90008-F

- UNWTO. (2019). International tourist arrivals reach 1.4 billion two years ahead of forecasts. Retrieved 16 June 2019, fromhttps://www2.unwto.org/press-release/2019-01-21/international-tourist-arrivals-reach-14-billion-two-years-ahead-forecasts.

- Uysal, M., & Hagan, L. R. (1993). Motivation of pleasure to travel and tourism. In M.A. Khan, M. D. Olsen, and T. Var (Eds.), VNR’S Encyclopedia of Hospitality and Tourism (pp. 798–810). Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Valduga, M. C., Breda, Z., & Costa, C. M. (2020). Perceptions of blended destination image: the case of Rio de Janeiro and Brazil. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 3(2), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-03-2019-0052

- Vandenbosch, M. B. (1996). Confirmatory compositional approaches to the development of product spaces. European Journal of Marketing, 30(3), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569610107418

- Weaver, P. A., McCleary, K. W., Lapisto, L., & Damonte, L. T. (1994). The relationship of destination selection attributes to psychological, behavioral and demographic variables. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 2(2), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1300/J150v02n02_07

- Wei, L., Qian, J., & Zhu, H. (2021a). Rethinking indigenous people as tourists: modernity, cosmopolitanism and the re-invention of indigeneity. Annals of Tourism Research, 89, 103200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103200

- Wei, W., Zheng, Y., Zhang, L., & Line, N. (2021b). Leveraging customer-to-customer interactions to create immersive and memorable theme park experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 5(3), 647–662. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-10-2020-0205

- Wheeller, B. (1993). Sustaining the ego. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589309450710

- Wheeller, B. (1994). Ego tourism, sustainable tourism and the environment: A symbiotic, symbolic or shambolic relationship?. In: Seaton, A.V. (Ed.), Tourism: The state of the art (pp. 647–654). Wiley.

- Wheeller, B. (2007). Sustainable mass tourism: more smudge than nudge. The canard continues. Tourism Recreation Research, 32(3), 73–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2007.11081543