Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the mediating role of organizational structure in the relationship between organizational culture and good sport governance in selected Ethiopian Olympic sports federations. The cross-sectional survey design was employed to collect data through a structured questionnaire from 265 respondents randomly selected from six sports federations. The validity and reliability of the involved measures were examined through confirmatory factor, Cronbach’s alpha, and correlation analyses. A structural equation modeling analysis with maximum likelihood estimation was conducted to test the relationships among the research variables using SPSS AMOS 23.0. The results indicate that (1) organizational structure significantly mediates the influence of organizational culture on good sport governance (B=.16, P<.01, CI [.072-.297]); (2) organizational culture unexpectedly has a non-significant direct effect on good sport governance (B =.07, t-value =1.33, p >.05), and (3) organizational structure also has a significant direct effect on good sport governance (B =.20, t-value =4.30, p <.001). Hence, the findings of this study signify the need for a fit between culture and structure to tailor the beliefs, values, and attitudes of organizational members through the optimally framed organizational structure to good sport governance implementation in the surveyed sports federations.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Many sports federations, since the last few decades, have been characterized by a hybrid nature (hybridity in goals, resource acquisition, and governance model) (Lucassen & Bakker, Citation2016; Lucassen & von Heijden, Citation2013) in that they behave like corporations and tend to be under ‘the scope of prescriptive approaches of democratic governance and corporate governance’ (Chappelet, 2013, as cited in Chappelet & Mirkonjic, Citation2013).

This scholars’ argument also works in sports federations in our national (Ethiopian) context, where sport governance and policies have been built on the principle of ‘sport for all’, (Federal Negarit Gazette of FDRE, Citation2010) where collaboration between business, labor, and civil society is expected to promote national integration and cohesion through sporting excellence, hence have multiple stakeholders accompanied by hybrid goals.

Despite this critical need for good governance in the sports sectors, they have lagged in inculcating it into organizational management (Pielke Jr., 2016). However, in the last few years, the issue of good governance has moved toward the top of the agenda by non-governmental organizations and sports organizations (Geeraert, Citation2022). Henceforth, ‘‘good governance in sport’ is a dominantly used concept by many scholars(e.g. Mirkonjic, Citation2016; Pielke et al., Citation2019) and governmental, non-governmental, and sports organizations (e.g. ASOIF, Citation2016; EC, Citation2013; IOC, Citation2022) and interchangeably used as ‘good sport governance’ by some scholars (e.g. Lam, Citation2014; Parent et al., Citation2022) in their studies with all the similarities in the conceptualization (meaning, theorization, and dimensions) of the two concepts. Similarly, with full cognizance of the similarities of the concepts which revolves around the sports governance, we used the concept ‘good sport governance’ consistently in our manuscript. Hence, Good sport governance is interpreted as the framework in which policies, bylaws, rules, and procedures are implemented by sports organizations so as to bring about a positive impact on legitimacy, effectiveness, and resistance to unethical practices (Geeraert, Citation2018).

This advocacy for good sport governance is due to factors such as (1) the commercialization and professionalization of sports events and competitions (Geeraert, Citation2016; Hoye et al., Citation2015; O’Boyle, Citation2012) and (2) a wide range of governance scandals being experienced by sports governing organizations under the authority of the Olympic movement, which has brought the autonomy of sport to cross-roads recently (Chappelet et al., Citation2008; O’Boyle, Citation2012; Pielke et al., Citation2019).

Scholars also argue that the successful implementation of good sport governance can be affected by various organizational or situational factors (Burger & Goslin, Citation2005; Geeraert, Citation2018; Mirkonjic, Citation2016) that sports organizations and public authorities should further evaluate and understand them in a more ‘holistic’ approach. This notion is also argued by Aguilera et al.(Citation2015) as the effectiveness of governance practice relies on factors of the wider institutional context in which organizations are set.

However, thus far, only a few studies have explored the causes that explain whether and to what extent sports organizations implement good governance practices (Mirkonjic, Citation2019). For instance, Mirkonjic (Citation2019) found commitment and personal motivation (at the micro-level), competencies and responsibilities of the internal body (at the meso level), and the role of the state and the umbrella organization (at the macro-level) as determinants of good sport governance. O’Boyle and Shilbury (Citation2016) also found out the extant level of trust, transparent decision-making, trust-building, and leadership as determinants, and the same authors again in 2018 qualitatively identified board structure at the national level, financial resources, leadership, and the potential for the strategic planning processes as determinants. In an African context, Mrindoko and Issa (Citation2023) found that openness and accountability, financial transparency and control, human resource competency, and policy execution are key predictors of effective governance for Tanzanian football federations and organizations.

In addition, some of the existing studies engaged in determinants were focused on specific dimensions of good governance, hence lacking the comprehensiveness needed to fully understand the causes that explain the implementation of multi-faceted good sport governance. For instance, Král and Cuskelly (Citation2017) found structural (membership, capacity of the staff), attitudinal, and knowledge-based determinants of transparency. Some studies (Babiak & Wolfe, Citation2009; Zeimers et al., Citation2020) found innovation capacity, financial autonomy, knowledge management, and human resources to be determinants of corporate social responsibility. In an African context still, Moyo et al. (Citation2020) found that internal factors (the organizations’ internal objectives, funds, people, and resources), external factors (external uncontrollable factors, economy, and community awareness), and stakeholder involvement to be factors influencing the engagement of South African professional sports organizations in sustainable corporate social responsibility.

In general, determinants of good sport governance in the aforementioned studies can be broadly summarized as the micro-level, meso-level, and macro-level, of which strategic management and organizational structure constitute the meso-level competencies of sports organizations.

However, except these few studies including those focused on specific dimensions, determinants of good sport governance have not yet been widely studied globally (Mirkonjic, Citation2019) and have not yet been thoroughly investigated in Africa, where the continent remains stunted by a combination of talent drain, a lack of government investment and policy guidelines, corruption, and gross mismanagement, as Tsuma (2016) argues. More specifically, the influence of organizational culture on good sport governance and the mediation role of the organizational structure in their relationship have not yet been empirically studied.

Moreover, in our national (Ethiopian) context, it is in line with the decentralized federated system that sport has been governed centrally by the jurisdiction of ministerial offices, the Ethiopian Sports Commission (governmental or state), the Ethiopian National Olympic Committee, and national federations or associations under it (non-governmental), and regionally by twelve sports commissions or the like and regional sports federations. In this regard, the ministry in charge of sports is the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (Federal Negarit Gazette of FDRE, Citation2018). However, despite the framing of sport governance and policies on the basis of ‘sport for all’ principle and the lengthened public experience in participating and governing sports and respecting sports instrumental role in societal development (Getahun, Citation2009), nowadays there is a disparity between the rhetoric and the current status of good governance in sport in Ethiopia, as studies indicate that there are quests for good governance. For instance, Athletics sport seems to face a lack of genuineness as youth projects are deprived of any coaching staff, sports facilities, and adequate support for athletes (Wolde & Gaudin, Citation2017); public wrangles for power, peer pressure, and widespread mismanagement have typified football, leaving many industrious players and the public disillusioned (Gebremariam, Citation2014).

Besides, the newly reframed national reform document boldly underlines that there are public questions about the representativeness of general councils and the electoral processes of executive bodies for being dominated by government, politicians, and ethnic influences regardless of the principle of ‘Olympism’ (Ethiopian Sport Commission [ESC], 2020). The national sports reform document also pinpointed that sports sectors in Ethiopia lack a strategic plan, and to some extent, even in the presence of a strategic plan, the insufficiency of the allocated budget hinders the implementation of the plan (ESC, Citation2020). Besides, Garmamo et al. (Citation2024) have found that the surveyed Olympic sports federations scored below the moderate level in good sport governance with a severely weak level of implementing transparency and public communication, and solidarity. Hence, these findings signify the need to further scrutinize what influences good sport governance practices in the surveyed sports federations.

In summary, despite all these drawbacks that call for the investigation, the relationship between organizational culture, organizational structure, and good sport governance has not yet been empirically studied in Ethiopian Olympic sports federations. Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of organizational culture on good sport governance through the mediation role of organizational structure in selected Ethiopian Olympic sports federations.

2. Conceptual framework and hypothesis development

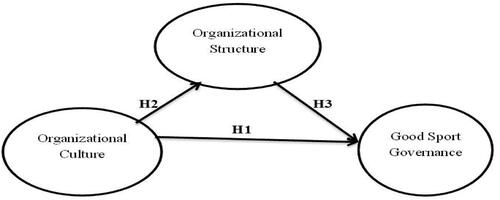

The conceptual model in this study focuses on the relationships between organizational culture, organizational structure, and good sport governance in the surveyed sports federations (see ), as the findings of this relationship will have paramount importance for strategic managers and practitioners to holistically understand the contexts of national sports organizations specifically the culture and structure fit for full-sized good governance practices.

2.1. Organizational culture and its influence on good governance

Organizational culture consists of a set of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that enable an organization to work effectively and achieve competitive results, which implies a set of attitudes such as the commitment of the participants, the forms of work, respect, professionalism, and ethics (García et al., Citation2012); hence, it provides a means by which a sports organization’s members interpret how things are done and what happens in daily working life (Hoye et al., Citation2015).

Previous studies in public organizations indicate that organizational culture affects organizational commitment (Neelam et al., Citation2015; Silverthorne, Citation2004); organizational effectiveness (Gregory et al., Citation2009); organizational efficiency (Aktaş et al., Citation2011); organizational performance (Sokro, Citation2012; Valmohammadi & Roshanzamir, Citation2014; Zehir et al., Citation2011); total quality management (Baird et al., Citation2011; Valmohammadi & Roshanzamir, Citation2014); and good governance performance (Dwi Ermayanti et al., Citation2019; Yuliastuti & Tandio, Citation2020).

Organizational culture, in the context of sport, is also found to have significant impacts on organizational success variables such as organizational effectiveness (Heris, Citation2014; Ramazaninejad et al., Citation2018; Seifari & Amoozadeh, Citation2014; Tojari et al., Citation2011); organizational performance (Bayle & Robinson, Citation2007); job satisfaction (Choi et al., Citation2008; MacIntosh & Doherty, Citation2010); organizational Innovation (Eskiler et al., Citation2016); empowerment and organization citizenship behavior (Jeong et al., Citation2019); knowledge management (Ramazaninejad et al., Citation2018); etc.

However, empirical studies in the areas of good governance overlook the significant impact organizational culture could have on it (Girginov, Citation2022). This author, in this regard, reveals the tendency of most studies to overlook the place of a change in the value system that underpins the culture of the organization as a requirement for ‘the implementation of any conception of good governance’ (p. 86). This indicates that there has not been a thorough investigation of empirical studies on the impact of positive organizational culture on public governance, and to be more specific, its impact on good sport governance has not yet been thoroughly investigated in the context of Ethiopian sports federations. Hence, this study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 1: Organizational culture significantly and positively influences good sport governance.

2.2. Organizational culture and organizational structure relationship

Organizational structure refers to the framework of relationships on jobs, systems, people, and operating processes where organizational tasks are divided in to determined duties for decision making that policies, procedures and rules are undertaken for organizational success (Bradish, Citation2003; Cunningham & Rivera, Citation2001). Organizational culture and structure have the highest explanatory and predictive power for the other organizational success variables. In this regard, Janićijević (Citation2013) posits that they are ‘the concepts with the highest explanatory and predictive power in understanding the causes and forms of people’s behaviours in organizations’ (p. 36).

Regarding their relationship, Král and Králová (Citation2016), citing Senior and Swailes (2010), indicated that organizational culture is one of the determinants of organizational structure, along with environment, strategy, technology, size, creativity, politics, and leadership. In national sports organizations, Hinings et al. (Citation1996) found that there is a link between values and structure.

Studies have also indicated that there is a mutual relationship between culture and structure. This mutual interdependence, as to Janićijević (Citation2013), is weaved in the manner that culture intrinsically directs the way people behave in everyday actions of an organization by operating from within and by determining assumptions, values, norms, and attitudes, and structure extrinsically influences people’s behavior from the outside, through formal limitations set by division of labor, authority distribution, grouping of units, and coordination.

Similarly, Alisa and Senija (Citation2010) argue that the interdependence is manifested in two ways phrased as ‘culture institutionalizes’ and ‘structure legitimizes. As to the authors, culture institutionalization is ‘a process in which cultural elements such as assumptions, beliefs, and values are entailed in the structure’, whereas structure legitimizing is ‘a process in which the structure is accepted by the employees, because it conforms to their cultural assumptions, beliefs, and values’. UKEssays (November 2018) also supports this notion and states that ‘organizational culture in some way defines the organizational structure of an organization, but the structure also partially defines the culture of an organization.

Notwithstanding their mutual interdependence in public sector’s governance performance, this study proposes that organizational culture influences organizational structure in the governance of national sports federations. Hence, based on these premises, this study hypothesizes the following:

H2. Organizational culture significantly and positively influences organizational structure.

2.1. Organizational structure and good sport governance

Organizational structure is considered to have the highest explanatory and predictive power for other organizational success variables (Janićijević, Citation2013). Hence, researchers in the area of public management have conducted many studies on the influence of organizational structure on organizational success.

Some of these empirical studies, for instance, examine the influence of organizational structure on organizational readiness for change (Benzer et al., Citation2017), organizational performance in relation to hybrid competitive strategies (Claver-cortés et al., Citation2012), managerial role expectations and managers’ work activities (Hales & Tamangani, Citation1996), organizational effectiveness through knowledge management (Zheng et al., Citation2010), organizational innovation (administrative and technological innovation) (Jaskyte, Citation2011), the effectiveness of communication (Renani et al., Citation2017), and organizational effectiveness in software companies (Basol & Dogerlioglu, Citation2014).

In the area of sport management, Cunningham and Rivera (Citation2001) studied the effect of organizational structure on organizational effectiveness (athletic achievements and student graduation rates) of NCAA Division I intercollegiate athletic departments and found a significant effect on athletic achievements but no significant effect on students’ graduation rates.

Though the aforementioned studies were conducted on the impact of organizational structure on organizational success variables (organizational innovation, organizational effectiveness, organizational performance, knowledge management etc. that are related to good governance in one way or another), researchers in the areas of public management and sports management have not yet investigated the influence of organizational structure on good sport governance, and more specifically no study has been conducted in Ethiopian Olympic sports federations. Hence, this study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 3: Organizational structure significantly and positively influences good sport governance.

This indicates that there are few empirical studies on the mediation effect of organizational structure, even in the public sector, and no studies have been conducted on the mediating role of organizational structure in the relationship between organizational variables in sports organizations. Hence, this study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 4: Organizational structure mediates the influence of organizational culture on good sport governance

3. Methods and materials

3.1. Research design

A descriptive cross-sectional survey was used in conducting this study, as a survey design provides a quantitative or numeric description of trends or opinions of a population by studying a sample of that population (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). Specifically, the cross-sectional survey design was best suited for this study, as Skinner et al. (Citation2015) argue; it is a design to identify the study population, select a sample, and contact the respondents to find out the required information from representatives of a given population at one point in time so that the results can be generalized.

3.2. Sampling and procedures

From the total of 16 Olympic sports federations, we purposively selected six federations (Ethiopian Football Federation (EFF), Ethiopian Athletics Federation (EAF), Ethiopian Basketball Federation (EBF), Ethiopian Volleyball Federation (EVBF), Ethiopian Handball Federation (EHF), and Ethiopian Cycling Federation (ECF)) for their being dominant throughout the country as they have a long history (more than half a century) of establishment with an average age of 66.98 (SD = 8.09), have a number of member clubs, are with the most popular sports events, and have the highest public focus on them.

Then, we selected 265 respondents from the sampled Olympic sports federations (based on Soper (Citation2021)’s a priori sample size calculator for SEM to determine the minimum sample size and in consideration of 20% attrition rates (for the main thesis) by proportionate stratified random sampling. The respondents were composed of executive committee members, staff, officials and coaches of the sampled sports federations as these are key internal stakeholders to judge the objective reality of good sport governance practice and its key determinants.

Prior to the data collection, the instruments were checked and approved by the institutional review board committee (IRBC No. IRB/04/14/22), and then the sampled Olympic sports federations were contacted to assist in the recruitment process. The participants were verbally informed to read and sign informed consent containing the rights to voluntary participation and withdrawal.

3.3. Instruments

Organizational culture was assessed using Cameron and Quinn’s (Citation2006, Citation2011) Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument, which is based on the Competing Value Framework (CVF) with four dimensions or scales: clan culture, adhocracy culture, market culture, and hierarchical culture, each containing six items, so that it has 24 items with a 5-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). This instrument was found to be internally consistent in the pilot study, with alpha values for clan culture (.81), adhocracy culture (.75), market culture (.83), and hierarchical culture (.74). Organizational structure was measured using the modified two dimensions of the Cunningham and Rivera (Citation2001) instrument. Formalization and specialization each contained eight and four items, respectively, on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), where respondents were asked to rate the level of agreement on the current status of these dimensions in their respective organizational structures. This instrument was found to be internally consistent in the pilot study, as it fulfills the suggested cut-off Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014) with alpha values for formalization (.87) and specialization (.79).

Good sport governance was assessed using the slightly modified and contextualized version of the Action for Good Governance in International Sports Organizations (AGGIS) sports governance observer tool (Geeraert, Citation2015). The original 36 indicators were extended to 38, as the four dimensions were kept the same: transparency and public communication (12 items), democratic processes (10 items), checks and balances (7 items), and solidarity (9 items). The modification and contextualization here included two items regarding the welfare of athletes into the solidarity dimension: (1) the federation implements rules and regulations aimed at helping athletes combine their sporting career with education or work, and (2) the federation implements the use of minimum requirements for standard athlete contracts, including minimum wages between athletes and clubs, athletes and managers, managers, and the organization itself, as these are likely to be the most ignored aspects in the governance of sport in our context.

Besides, the initial five-point Likert scale (not fulfilled at all (1), weak (2), moderate (3), good (4), and state-of-the-art (5)) was modified in a range from ‘not fulfilled at all’ (1) to ‘fulfilled at all’ (5) on the assumption that it should reflect measures of perceived level of implementation of good sport governance with some meaning and value to all stakeholders participating in the study and found internally consistent in the pilot of this study, as it fulfills the suggested cut-off Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014) with the values of transparency and public communication (.87), democratic processes (.84), checks and balances (.82), and solidarity (.83).

3.4. Method of data analysis

The data were analyzed by IBM SPSS 26 and Amos 23.0, and the level of statistical significance was set at ɑ <.05. Descriptive statistics (e.g. means and standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, socio-demographic characteristics, etc.) were calculated by IBM SPSS 26.

The constructs involved in this study were all superordinate (manifested by their dimensions) (Edwards, Citation2001) with multidimensional interactions, and they are themselves constructs that function as specific manifestations of the more general constructs. However, in the SEM of this study, the multidimensional superordinate constructs, both exogenous (organizational culture) and endogenous (organizational structure and good sport governance), were operationalized as first-order constructs by calculating the mean response of each dimension and treating the dimensions as direct observations (Li et al., Citation2008).

Then, a two-step SEM approach was used, where the measurement model (CFA) was first evaluated to assess internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, as it is boldly cautioned to establish validity and reliability during data analysis when modifying an instrument or combining instruments in the study, as the original validity and reliability may not hold for the new instrument (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). The structural regression model was then used to test the proposed hypotheses. The model fit measures for both the measurement and the structural models were compared against threshold values for determining model fit (Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2010, p. 76).

4. Results

4.1. Background information of respondents and the response rate

A survey was conducted by distributing questionnaires to 265 respondents from February to June 2022, and upon serious follow-ups, 238 completed questionnaires were collected with an 89.8% response rate. When respondents were seen in their stakes, officials were nearly half (50.4%) of the respondents, followed by coaches, who covered 35.7% of the respondents. The remaining 2.9% and 10.9% portions were covered by executive committee members and paid staff, respectively.

Regarding the sex and age composition of the respondents, the vast majorities (87.4%) were male, and the remaining 12.6% were female. The age category above 30 comprised the large majority (83.6%). When the academic level of the study participants and years of work experience are seen, holders of BA/BSc degrees and MA/MSc degrees together took the highest share (68.5%) of the respondents, and nearly half of the respondents (52.1%) were found to have the work experience of 1–10, and 37.4% lie in the experience category of 11–20, which together form 89.5%.

4.2. Preliminary analyses

Before conducting SEM, preliminary checks were made. The data were examined for the presence of missing data, and hence no missing data was found. Besides, as this study used only a questionnaire as instrument to collect the data, it becomes imperative to confirm the absence of common method bias error. Hence, Harman’s single factor test was conducted by using SPSS. The factor analysis was performed without any rotation, and all items were loaded on an only factor. The results revealed that a single factor accounted for 21.35% of the variance which is far less than 50%, indicating that there is no threat of common method bias (Kock, Citation2021) (see Supplementary Table 1).

Multivariate normality was checked by using graphical analysis (normal probability plot) and statistical analysis (critical value of skewness and kurtosis) (Hair et al., Citation2014), as it is recommended to use both the graphical plots and any statistical tests to assess the actual degree of departure from normality. The normal probability plots of the study variables indicated the normal distribution (see Supplementary Figure 1), as the lines represent the actual data distribution closely following the diagonal line (Hair et al., Citation2014). Statistically, the values for skewness were found in the range from .030 to 1.92, and the values for kurtosis ranged from -4.107 to. 613, indicating that there is no extreme non-normality as they are found in the region of skewness less than 3, and kurtosis less than 8 for the level of significance (Hair et al., Citation2014) (see Supplementary Table 2). Multivariate outliers were also checked by Mahalanobi’s D2 measure, where the ratio of D2 to the degree of freedom (D2/df) was computed and judged, as observations with values exceeding 2.5 could be designated as possible outliers (Hair et al., Citation2014, pp. 64–65). Hence, no outliers were detected in this data, as the highest MD2 is 29.95 with a degree of freedom of 31(see Supplementary Table 3).

Moreover, multicollinearity was checked by using the tolerance value, VIF (variance inflation factor), and condition index for their cut-off points of >.10, <10, and <15, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2014). As the values of these parameters were at acceptable levels: tolerance (.89 both), VIF (1.12 both), and condition index (13.34), they indicate that there is no threat of multicollinearity that can easily lead to unstable regression coefficients. Hence, further multivariate analyses were conducted (see Supplementary Table 4).

Internal consistency-reliability was ensured by generating Cronbach’s alpha values for the fulfillment of the suggested cut-off value of 0.70 (Hair et al., Citation2014). The measurement model (CFA) for a satisfactory level of validity and reliability (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) was also computed (see Supplementary Figure 2). The model fit measures were compared against threshold values for determining model fit (Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2010, p. 76), and the outputs indicate that the Normed Chi-square (χ2 (70.25)/df(31) = 2.27, RMSEA =.073, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, SRMR = .049, and p-value <.001 which, according to the suggested characteristics of different fit indices, demonstrate the goodness of fit that the construct validity of the measurement model was established (see Supplementary Table 5).

The factor loadings, average variance extracted, discriminant validity and composite reliability of the constructs were computed (see ). In this regard, the factor loadings of each parceled indicator of the constructs in CFA were found to be significant, ranging from.43 (transparency and public communication in good governance in sport) to.95 (formalization in organizational structure), hence indicates the initial level of convergent validity is fulfilled. Here, it seems important to note that 0.4 factor loading is the recommended threshold (having practical significance) for sample sizes 200 and above (Hair et al., Citation2014).

Table 1. Descriptives, reliability and validity measures of the study constructs.

The average variance extracted approximately ranges between.4 (good sport governance) and.68 (organizational structure), meaning that all except the construct good sport governance meet the recommended level of .5 (Hair et al., Citation2014). However, as argued by some previous studies (e.g. Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981), the average variance extracted may be a more conservative estimate of the validity of the measurement model; hence, one can conclude the convergent validity on the basis of composite reliability. The composite reliability of the constructs in the model was well above the recommended level .70 (Hair et al., Citation2014). So, we concluded that the convergent validity of good sport governance is adequate on the basis of composite reliability (.71). Moreover, discriminant validity is fulfilled as the square root of AVE (DV) is higher than any of the correlation of the constructs.

4.3. Tests of Hypotheses

4.3.1. Hypotheses of direct paths

To address hypotheses 1–3, we developed a hypothesized structural model that specified 3 direct paths (see Supplementary Figure 3) and appeared to have an acceptable fit, i.e. the Normed Chi-square (χ2 (70.25)/df(31) = 2.27, RMSEA =.073, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, SRMR =.049, and p-value <.001. In the direct paths of the model (see ), the path coefficient from organizational culture to good sport governance was found to be statistically non-significant (B =.07, t-value =1.33, p >.05), thus doesn’t indicate support for hypothesis 1.

Table 2. Direct path analysis summary.

On the contrary, the coefficient of the path from organizational culture to organizational structure was found to be positive and statistically significant (B =.79, t-value = 5.45, p <.001), thus indicating support for hypothesis 2, as a unit increment in organizational culture can explain 0.79 increments in organizational structure.

Similarly, the coefficient of the path from organizational structure to good sport governance was found to be positive and statistically significant (B =.20, t-value =4.30, p <.001), thus indicating support for hypothesis 3, as a unit increment in organizational structure can explain 0.20 increments in good sport governance.

4.3.2. Hypotheses of mediation

Mediation analyses were performed to assess the mediation role of organizational structure in the relationship between organizational culture and good sport governance, by using the index approach (Igartua & Hayes, Citation2021; O’Rourke & MacKinnon, Citation2018) with the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence limit that provides the most accurate confidence limits and greatest statistical power (Mackinnon et al., Citation2004), where the sample size was bootstrapped to 1000 (Igartua & Hayes, Citation2021, p. 5).

The results (see ) revealed a significant indirect effect of organizational culture (B=.16, P<.01, CI [.072, .297]). The total effect of organizational culture on good sport governance was significant (B=.23, SE=.07, P<.001). With the inclusion of the mediator, the effect of organizational culture on good sport governance was insignificant (B=.072, SE = .064, P>.05). This finding, as there is a significant indirect effect, shows that there is a mediation effect (Igartua & Hayes, Citation2021) without considering direct and total effects. The bootstrap confidence interval as indicated above shows that zero is outside the confidence interval. Hence, this study supports Hypothesis 4a that organizational structure mediates the influence of organizational culture on good sport governance.

Table 3. Mediation analysis summary.

5. Discussion of the results

The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of organizational culture on good sport governance through the mediating role of organizational structure. In doing so, the findings of this study have provided empirical discussions.

Hence, our results revealed that organizational culture has non-significant direct impact on good sport governance. This finding contradicts previous studies in public organizations that indicate the influence of organizational culture on total quality management (Baird et al., Citation2011; Valmohammadi & Roshanzamir, Citation2014) and good governance performance (Dwi Ermayanti et al., Citation2019; Yuliastuti & Tandio, Citation2020). This unexpected finding on the direct impact of organizational culture on good sport governance triggered questions of why in the mind of the researchers and the desire to see the impact of each dimension of organizational culture on good sport governance explicitly, which initially was not intended in this study. Hence, it was found that all the cultural dimensions except adhocracy culture (B =.17, t-Value =2.89, P <.05) had non-significant impacts on good sport governance, with very non-significant impacts of clan (B =-.24, t-Value =-.49, P =.63) and hierarchy culture (B =-.01, t-Value =-.26, P =.79).

Hence, these findings of the effects of each culture dimension on good sport governance were in line with the findings of previous quantitative studies where the cultural dimensions (clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchical) were found to have different effects on organizational success variables. For instance, Xenikou and Simosi (Citation2006) found out that the achievement (market) culture was related to performance, whereas the humanistic orientation (clan) culture was not. Naranjo-Valencia et al. (Citation2016), in their study on the link between organizational culture, innovation, and performance in Spanish companies, concluded that the adhocracy and the clan cultures have positive effects on performance, whereas the hierarchy and the market (out of expectation) cultures have negative effects. Fatima (Citation2016) also found that employees working under clan and adhocracy cultures were satisfied with their jobs, whereas those working under hierarchy and market cultures were dissatisfied. In the same vein, the findings of Jeong et al. (Citation2019) revealed that all of the sub-factors of organizational culture except hierarchy culture were found to have a positive influences on perceived empowerment, which in turn has a positive effect on organizational citizenship behavior in the South Korean professional sport industry.

This is a context-dependent difference in the influence of cultural dimensions (factors) on good sport governance, especially the very non-significant impacts of clan and hierarchy cultures, which is believed to cumulatively result in an unexpectedly non-significant influence of organizational culture on good sport governance in the context of Ethiopian Olympic sports federations. On top of this, weak strategic direction, a lack of dedicated leadership, and a low focus on providing training support to enhance the employees’ capabilities in most national sports federations might have resulted in loosening the beliefs, values, and attitudes of the staff to be committed to the organizational goals and hence to good governance practices.

However, organizational culture was found to have a positive and significant effect on organizational structure. This finding is in congruence with the finding of Senior and Swailes (2010) cited in Král and Králová (Citation2016) where organizational culture is one of the determinants of organizational structure, along with environment, strategy, technology, size, creativity, politics, and leadership.

It also is supported in this study that organizational structure has a positive and significant influence on the good governance of national sports federations. This finding is consistent with the findings of previous studies in public management such as the findings of Basol and Dogerlioglu (Citation2014), who asserted the positive relationship of organizational structure (formalization and specialization) with organizational effectiveness, and Benzer et al. (Citation2017), who confirmed the influence of organizational structure (differentiation and integration) on the individual level readiness for change in the areas of public management.

This finding also bears resemblance to the findings of Amis et al.(Citation1995), in which the high level of formalization was demanded to act against conflict as the low level of formalization caused conflict in a voluntary sports organization, and Cunningham and Rivera’s (Citation2001) finding of the structure’s influence on the effectiveness of sports organizations. Moreover, Hoye (Citation2003) avowed role clarification within boards and between volunteers and staff as a determinant of good sport governance, along with other factors (p. 219). Furthermore, the finding is in corroboration with that of Breitbarth and Rieth’s (Citation2012) 3S model, where structure along with strategy and stakeholder, is found as a key driver of corporate social responsibility integration.

Finally, the findings reported in this paper support the mediating role of organizational structure in the relationship between organizational culture and good sport governance. Analysis of H4 shows that organizational structure mediates the influence of organizational culture on good sport governance significantly. The finding is consistent with the findings of previous studies in public management where organizational structure links the organizational variables (e.g. Abu Rassa & Emeagwali, Citation2020;Shoghi et al., Citation2013). This structure mediated-influence of organizational culture on good sport governance suggests that cultural beliefs, values and attitudes of organizational members are translated in to good governance of the national sport governing bodies through the well framed organizational structure and is in line with Alisa and Senija’s (Citation2010) argument on the interdependence between two variables that is manifested in two ways as phrased as ‘culture institutionalizes’ and ‘structure legitimizes.

In summary, the findings demonstrate the importance of the optimally framed organizational structure (formalization and specialization) to tailor the beliefs, values, and attitudes of organizational members to the attainment of optimal good governance in sports organizations.

6. Management implications

The current study has several theoretical and practical implications for sports managers. The findings carry theoretical implications for the literature on the relationship between organizational culture, organizational structure, and good sport governance, as the scope of this study is extended from merely examining its implementation to examining contextual mechanisms that determine the level of implementation in national sports federations. From a practical perspective, this study (a) signifies the two-fold importance of organizational structure (formalization and specialization) in implementing good sport governance and (c) pinpoints the need for a fit between culture and structure to tailor the beliefs, values, and attitudes of organizational members through the optimally framed organizational structure to good sport governance implementation in the surveyed sports federations.

7. Limitations and future directions

As with any research investigation, this study is not without limitations. First, despite the effort made to achieve the desirable internal consistency attributes for all of the subscales, the lack of universally agreed up on indicators of good governance in general, and inconsistency of SGO indicators and the limited application of it in national contexts specifically may shadow the findings of this study. Hence, the future studies using this tool should further engage in national contexts to validate the instrument. Second, the operationalization of multidimensional superordinate constructs (organizational culture, organizational structure, and good sport governance) as first-order constructs by calculating the mean response of each dimension and treating the dimensions as direct observations (Li et al., Citation2008, p. 53) might shadow the findings, as this approach confounds random measurement error with dimension specificity and disregards the relationship between each dimension and its measures (Edwards, Citation2001; Koufteros et al., Citation2009). Hence, future studies may further utilize higher-order modeling (Koufteros et al., Citation2009).

Third, national sports governing bodies have stakeholders internally and externally, which obviously can benefit or be benefited by the organizations. However, this study is limited only to internal stakeholders (executive members, paid staff, senior coaches, and senior officials) to gather data that may limit the comprehensiveness of the perceived state of the study variables. Hence, future studies should better include representatives of external stakeholders.

Fourth, the data for this study were gathered via a cross-sectional survey, so associations between variables are not sufficient to establish causal relationships. Future longitudinal analyses would be useful to study causality.

Finally, as this study is quantitative in methodology, it tends to provide a partial view as it fails to incorporate qualitatively in-depth perceptions of stakeholders to validate the findings of one strand with the other. Hence, future studies should better engage in a mixed-methods study, as the concepts of good governance and determinants such as organizational culture and organizational structure are social constructs that hold a debatable (and elusive) position in their definition and measurement.

8. Conclusion

The findings of this study shed light on the untested relationship between organizational culture, organizational structure, and good sport governance in Ethiopian Olympic sports federations. In this regard, first, the study revealed an unexpectedly non-significant direct influence of organizational culture on good sport governance.

Second, this study suggests that organizational structure, in addition to having a direct and positively significant influence on good sport governance, has a linking role in the relationship between organizational culture and good sport governance. This dual role of organizational structure signifies the critical importance of it in the implementation of good governance in the national sports federations, hence strengthening the call for attention to be given to optimal structural arrangements to fully implement the national demands accompanied by the multifaceted interests of sports actors. This also reminds us of the need for a fit between organizational culture and structure in Ethiopian Olympic sports federations to bring about the mutual intertwine where one (culture) institutionalizes and the other (structure) legitimizes good governance practices in Olympic sports federations.

Finally, this study indicated the major limitations and the future directions in further scrutiny of the relationships between the studied variables in similar contexts.

Authors’ contributions

Mengistu Galcho Garmamo: conception and design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, critical review and approval of the manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Tesfay Asgedom Haddera: conception and design, interpretation of the data, critical review and approval of the manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Zeru Bekele Tola: conception and design, interpretation of the data, critical review and approval of the manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Matiwos Ensermu Jaleta: conception and design, interpretation of the data, critical review and approval of the manuscript, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to publish the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (9.4 MB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all who contributed a lot during the data collection process. A deep gratitude also goes to the participants of the survey from all six selected Olympic sport federations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the materials supporting the findings of this study are available within the supplementary materials, and the data can be available upon reasonable request.

References

- Abu Rassa, H., & Emeagwali, L. (2020). Laissez fair leadership role in organizational innovation : The mediating effect of organization structure. Management Science Letters, 10, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.12.022

- Aguilera, R. V., Desender, K., Bednar, M. K., & Lee, J. H. (2015). Connecting the dots : Bringing external corporate governance into the corporate governance puzzle. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 483–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2015.1024503

- Aktaş, E., Çiçek, I., & Kıyak, M. (2011). The effect of organizational culture on organizational efficiency : The moderating role of organizational environment and CEO values. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24(1), 1560–1573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.092

- Alisa, D., & Senija, N. (2010). The organizational structure and organizational culture interdependence analysis with a special reference to Bosnian and Herzegovinian enterprises. Economic Analysis, 43(3–4), 70–86.

- Amis, J., Slack, T., & Berrett, T. (1995). The structural antecedents of conflict in voluntary sport organizations. Leisure Studies, 14(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614369500390011

- ASOIF. (2016). ASOIF governance task force (GTF) report approved by ASOIF general assembly 2016.

- Babiak, K., & Wolfe, R. (2009). Determinants of corporate social responsibility in professional sport : Internal and external factors. Journal of Sport Management, 23(6), 717–742. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.6.717

- Baird, K., Hu, K. J., Centre, Y., & Reeve, R. (2011). The relationships between organizational culture, total quality management practices and operational performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 31(7), 789–814. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571111144850

- Basol, E., & Dogerlioglu, O. (2014). Structural determinants of organizational effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Management Studies, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5171/2014.273364

- Bayle, E., & Robinson, L. (2007). A framework for understanding the performance of national governing bodies of sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 7(3), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740701511037

- Benzer, J. K., Charns, M. P., Hamdan, S., & Afable, M. (2017). The role of organizational structure in readiness for change: A conceptual integration. Health Services Management Research, 30(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951484816682396

- Bradish, C. L. (2003). An examination of the relationship between regional sport commissions and organizational structure [PhD dissertation, The Florida State University].

- Breitbarth, T., & Rieth, L. (2012). Strategy, stakeholder, structure: Key drivers for successful CSR Integration in German professional footbal. In C. Anangnostopoulos (Ed.), Contextualising research in sport: An international perspective (pp. 45–63). ATINER.

- Burger, S., & Goslin, A. (2005). Best practice governance principles in the sports industry: An overview. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation, 27(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajrs.v27i1.25904

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing value framework (Revised ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2011). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture based on the competing values framework (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Cetinkaya, S. A., & Rashid, M. (2018). The effect of social media on employees’ job performance : The mediating role of organizational structure. MPRA, 91354. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/91354/

- Chappelet, J., & Mirkonjic, M. (2013). Basic indicators for better governance in international sport (BIBGIS): An Assessment tool for international governing bodies (No. 1; January). www.idheap.ch%3EPublications %3EWorking Papers

- Chappelet, J.-L., Kübler., & Mabbott, B. (2008). The International Olympic Committee and the Olympic System: The governance of world sport (1st ed., and T. G. Weiss & R. Wilkinson, eds.). Routledge.

- Choi, Y. S., Martin, J., & Park, M. (2008). Organizational culture and job satisfaction in Korean professional baseball organizations. International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences, 20(2), 59–77. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/coe_khs/40

- Claver-Cortés, E., Pertusa-Ortega, E. M., & Molina-Azorín, J. F. (2012). Characteristics of organizational structure relating to hybrid competitive strategy: Implications for performance. Journal of Business Research, 65(7), 993–1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.04.012

- Creswell, J., & Creswell, J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Cunningham, G. B., & Rivera, C. A. (2001). Structural designs within American intercollegiate athletic departments. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 9(4), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb028941

- Dwi Ermayanti, S., Noer, S., Anasthasia, T. B., Djuwitawati, R., Ari, R., Wasis, W., & Fanlia Prima, J. (2019). The effect of employee commitment, culture, and leadership style on good governance performance of Jombang District government (Indonesia). Espacios, 40(27), 1–9.

- EC. (2013). Expert group “good governance” deliverable 2 principles of good governance in sport.

- Edwards, J. R. (2001). Multidimensional constructs in organizational behavior research : An integrative analytical framework. Organizational Research Methods, 4(2), 144–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810142004

- ESC. (2020). Study and program of national sports reform: Sports for national prosperity.

- Eskiler, E., Geri, S., Sertbas, K., & Calik, F. (2016). The effects of organizational culture on organizational creativity and innovativeness in the sports businesses. The Anthropologist, 23(3), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2014.11891978

- Fatima, M. (2016). The impact of organizational culture types on the job satisfaction of employees. Sukkur IBA Journal of Management and Business, 3(1), 13–32. https://doi.org/10.30537/sijmb.v3i1.135

- Federal Negarit Gazette of FDRE. (2010). A proclamation to provide for the establishment the sport commission. Proclamation No. 692/2010, 5664–5669.

- Federal Negarit Gazette of FDRE. (2018). A proclamation to provide for the definition of the powers and duties of the executive organs of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Proclamation No. 1097/2018, 58.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- García, L. E., Sanchez, M. G., Cuevas, H., Hernández, R., & Vargas, B. E. (2012). Organizational culture diagnostic in two Mexican technological universities case study. Innovacion Y Desarrolo Tecnologico Revista Digital, 4(4), 1–19.

- Garmamo, M. G., Haddera, T. A., Tola, Z. B., & Jaleta, M. E. (2024). Good sport governance in selected Ethiopian Olympic Sports Federations: A mixed-methods study. Journal of New Studies in Sport Management, 5(1), 987–1004. https://doi.org/10.22103/jnssm.2023.21248.1176

- Gebremariam, D. (2014). The status of club management in Ethiopian premier league football clubs [Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University].

- Geeraert, A. (2015). Sport Governance Observer 2015: The legitimacy crisis in international sports governance. http://www.playthegame.org/media/3968653/SGO_report_web.pdf

- Geeraert, A. (2016). The EU in international sports governance: A principal-agent perspective on EU control of FIFA and UEFA. In S. Oberthür, K. E. Jørgensen, A. Warleigh-Lack, S. Lavenex, & P. Murray (Eds.), The European Union in international affairs series (1st ed.). Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137517784

- Geeraert, A. (2018). National Sports Governance Observer: Final report.

- Geeraert, A. (2022). Introduction: The need for critical reflection on good governance in sport. In A. Geeraet & F. Van Eekeren (Eds.), Good governance in sport: Critical reflections (1st ed., pp. 1–12). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003172833

- Getahun, S. A. (2009). A history of sport in Ethiopia. In S. Ege, H. ASpen, B. Teferra, & B. Shiferaw (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies (pp. 409–418).

- Girginov, V. (2022). A relationship perspective on organisational culture and good governance in sport. In A. Geeraet & F. Van Eekeren (Eds.), Good governance in sport: Critical reflections (1st ed., pp. 86–98). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003172833-7

- Gregory, B. T., Harris, S. G., Armenakis, A. A., & Shook, C. L. (2009). Organizational culture and effectiveness : A study of values, attitudes, and organizational outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 62(7), 673–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.021

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson new International edition.

- Hales, C., & Tamangani, Z. (1996). An investigation of the relationship between organizational structure, managerial role expectations and managers’ work activities. Journal of Management Studies, 33(6), 731–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1996.tb00170.x

- Heris, M. S. (2014). Effects of organizational culture on organizational effectiveness in Islamic Azad universities of northwest Iran. Indian Journal of Fundemental Applied Life Siiences, 4(53), 250–256. www.cibtech.org/sp.ed/jls/2014/03/jls.htm

- Hinings, C. R., Thibault, L., Slack, T., & Kikulis, L. M. (1996). Values and organizational structure. Human Relations, 49(7), 885–916. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679604900702

- Hoye, R. (2003). The role of the state in sport governance : An analysis of Australian government policy. Annals of Leisure Research, 6(3), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2003.10600922

- Hoye, R., Smith, A. C. T., Nicholson, M., & Stewart, B. (2015). Sport management: Principles and applications (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Igartua, J. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2021). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: Concepts, computations, and some common confusions. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24(6), e49. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2021.46

- IOC. (2022). Basic universal principles of good governance within the Olympic movement. In IOC Code of Ethics. www.olympics.com/ioc

- Janićijević, N. (2013). The mutual impact of organizational culture and structure. Economic Annals, 58(198), 35–60. https://doi.org/10.2298/EKA1398035J

- Jaskyte, K. (2011). Predictors of administrative and technological innovations in nonprofit organizations. Public Administration Review, 71(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02308.x

- Jeong, Y., Kim, E., Kim, M., & Zhang, J. J. (2019). Exploring relationships among organizational culture, empowerment, and organizational citizenship behavior in the South Korean professional sport industry. Sustainability, 11(19), 5412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195412

- Kock, N. (2021). Harman’s single factor test in PLS-SEM: Checking for common method bias. Data Analysis Perspectives Journal, 2(2), 1–6.

- Koufteros, X., Babbar, S., & Kaighobadi, M. (2009). A paradigm for examining second-order factor models employing structural equation modeling. International Journal of Production Economics, 120(2), 633–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.04.010

- Král, P., & Cuskelly, G. (2017). A model of transparency: Determinants and implications of transparency for national sport organizations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(2), 237–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1376340

- Král, P., & Králová, V. (2016). Approaches to changing organizational structure: The effect of drivers and communication. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5169–5174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.099

- Lam, E. T. C. (2014). The roles of governance in sport organizations. Journal of Power, Politics & Governance, 2(2), 19–31. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272789182

- Li, X., Hess, T. J., & Valacich, J. S. (2008). Why do we trust new technology? A study of initial trust formation with organizational information systems. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 17(1), 39–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2008.01.001

- Lucassen, J. M. H., & Bakker, S. D. (2016). Variety in hybridity in sport organizations and their coping strategies. European Journal for Sport and Society, 13(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2016.1153880

- Lucassen, J., & von Heijden, A. (2013). Hybrid professions in the sport sector. In 21th EASM Conference, pp. 1–3.

- MacIntosh, E. W., & Doherty, A. (2010). The influence of organizational culture on job satisfaction and intention to leave. Sport Management Review, 13(2), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2009.04.006

- Mackinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioural Research, 39(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901

- Mirkonjic, M. (2019). Determinants of sport governance: Evidence from Switzerland. In T. Breitbarth, G. Bodet, A. F. Luna, P. B. Naranjo, & G. Bielons (Eds.), The 27th European Sport Management Conference (pp. 749–751). European Association of Sport Management.

- Moyo, T., Duffett, R., & Knott, B. (2020). Environmental factors and stakeholders influence on professional sport organisations engagement in sustainable corporate social responsibility : A South African perspective. Sustainability, 12(11), 4504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114504

- Mrindoko, A., & Issa, F. H. (2023). Factors that influence good governance in The Tanzania Football Federation. Journal of Business and Management Review, 4(5), 340–362. https://doi.org/10.47153/jbmr45.6402023

- Mirkonjic, M. (2016). A review of good governance principles and indicators in sport. Enlarged Partial Agreement on Sport (EPAS).

- Naranjo-Valencia, J. C., Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2016). Studying the links between organizational culture, innovation, and performance in Spanish companies. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 48(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rlp.2015.09.009

- Neelam, N., Bhattacharya, S., Sinha, V., & Tanksale, D. (2015, February). Organizational culture as a determinant of organizational commitment : What drives IT employees in India ? Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 34(2), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe

- O’Boyle, I. (2012). Corporate governance applicability and theories within not-for-profit sport management. Corporate Ownership and Control, 9(2), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv9i2c3art3

- O’Boyle, I., & Shilbury, D. (2016). Exploring issues of trust in collaborative sport governance. Journal of Sport Management, 30(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2015-0175

- O’Rourke, H. P., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2018). Reasons for testing mediation in the absence of an intervention effect: A research imperative in prevention and intervention research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(2), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2018.79.171

- Parent, M. M., Hoye, R., Taks, M., Naraine, M. L., & Seguin, B. (2022). Good sport governance and design archetype: One size doesn’t fit all. In A. Geeraert & F. van Eekeren (Eds.), Good governance in sport: Critical reflections (1st ed., pp. 180–194). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003172833

- Pielke, R., Harris, S., Adler, J., Sutherland, S., Houser, R., & Mccabe, J. (2019). An evaluation of good governance in US Olympic sport National Governing Bodies. European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(4), 480–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2019.1632913

- Pielke, R., Jr. (2016). Obstacles to accountability in international sports governance. In G. Sweeney & K. McCarthy (Eds.), Global corruption report: Sport (1st ed., pp. 1–372). Transparency International.

- Ramazaninejad, R., Shafiee, S., & Asayesh, L. (2018). The effect of organizational culture on organizational effectiveness with meditating of knowledge management in the Directorate Office of Sport and Youth in East Azerbaijan Province. Applied Research of Sport Management, 7(2), 111–122.

- Renani, G. A., Ghaderi, B., & Mahmoudi, O. (2017). The impact of organizational structure on the effectiveness of communication from the perspective of employees in the department of education. International Journal of Management, Accounting and Economics, 4(10), 989–1001.

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Seifari, M. K., & Amoozadeh, Z. (2014). The relationship of organizational culture and entrepreneurship with effectiveness in sport organizations. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 2(3), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.aassjournal.2.3.51

- Shoghi, B., Asgarani, M., & Ashnagohar, N. (2013). Mediating effect of organizational structure on the relationship between managers ‘ leadership style and employees ‘ creativity. International Journal of Learning and Development, 3(3), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijld.v3i3.3736

- Silverthorne, C. (2004). The impact of organizational culture and person-organization fit on organizational commitment and job satisfaction in Taiwan. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(7), 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730410561477

- Skinner, J., Edwards, A., & Corbett, B. (2015). Research methods for sport management (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Sokro, E. (2012). Analysis of the relationship that exists between organizational culture, motivation and performance. Problems of Management in the 21st Century, 3(1), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.33225/pmc/12.03.106

- Soper, D. S. (2021). A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models [Software]. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

- Tojari, F., Heris, M. S., & Zarei, A. (2011). Structural equation modeling analysis of effects of leadership styles and organizational culture on effectiveness in sport organizations. African Journal of Business Management, 5(21), 8634–8641. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM11.1156

- Tsuma, C. (2016). Corruption in Africa. In Transparency International (Ed.), Global corruption report: Sport (pp. 1–372). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315695709

- UKEssays. (2018, November). Relationship between organizational structure and culture. https://www.ukessays.com/essays/business/relationship-between-organizational-structure-and-culture-business-essay.php?vref=1

- Valmohammadi, C., & Roshanzamir, S. (2014). The guidelines of improvement: Relations among organizational culture, TQM and performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 164, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.12.028

- Wolde, B., & Gaudin, B. (2017). Grass-root training : A challenge for Ethiopian athletics. In B. Guadin (Ed.), Kenyan and Ethiopian athletics - towards an alternative scientific approach (pp. 1–6). HAL. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01428791

- Xenikou, A., & Simosi, M. (2006). Organizational culture and transformational leadership as predictors of business unit performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(6), 566–579. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610684409

- Yuliastuti, I. A. N., & Tandio, D. R. (2020). Leadership style on organizational culture and good corporate governance. International Journal of Applied Business and International Management, 5(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.32535/ijabim.v5i1.764

- Zehir, C., Ertosun, Ö. G., Zehir, S., & Müceldili, B. (2011). The effects of leadership styles and organizational culture over firm performance: Multi-national companies in Istanbul. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 1460–1474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.032

- Zeimers, G., Lefebvre, A., Winand, M., Anagnostopoulos, C., Zintz, T., & Willem, A. (2020). Organisational factors for corporate social responsibility implementation in sport federations: A qualitative comparative analysis. European Sport Management Quarterly, 21(2), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1731838

- Zheng, W., Yang, B., & McLean, G. N. (2010). Linking organizational culture, structure, strategy, and organizational effectiveness: Mediating role of knowledge management. Journal of Business Research, 63(7), 763–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.06.005