Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that human security is just as important as state security. The public health emergency unleashed by the pandemic has affected all sectors of human lives and has become a ‘human rights crisis’ affecting human dignity. From the broad human security architecture perspective, this research seeks to understand how Covid-19 has impacted human security in Ghana. The study used the mixed method approach to collect and analyse data from 163 household heads and six key informants. The interview schedule and guide were used to collect information from the household head and the key informants. In the end, it was evident that the pandemic seriously affected households’ disposable incomes, access to healthcare, and livelihoods. In addition, it was evident that the pandemic affected their civic liberties concerning freedom of movement, association and religion. The study also revealed little support was offered to people with disabilities and older people. Financial constraints and the harsh effects of the lockdown reduced their disposable income and made spending on PPEs very difficult. It is recommended that governments should implement policies to reduce disparities and improve access to essential services, including healthcare, education, and social support, particularly for marginalized communities. However, these policy interventions should be done to benefit all and not only political party members.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us valuable lessons that must direct our future efforts to enhance human security. The pandemic has affected not only our health systems but also the very essence of our lives and dignity as humans. This study examines how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the multifaceted nature of human security, a phenomenon that goes beyond the lack of conflict to include the defence of fundamental liberties and rights that uphold people’s dignity and well-being as individuals and as a community. Our study sheds light on how the pandemic has affected our healthcare system, social cohesion, educational system, human rights principles, and economic security. Our study goes beyond the contribution to human security discourse to influence the understanding of policymakers in building a society in which each person can live in safety and dignity and to withstand current difficulties and unforeseen events in the future.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

The unexpected outbreak of the Corona Virus Disease, popularly called COVID-19, has reminded the world’s leaders that ‘infectious diseases could be significantly and substantially more damaging and ravaging irrespective of a country’s economic resources’ (Ismahene, Citation2021). This coronavirus outbreak remains a historical challenge and has resulted in a drastic change in human history that will forever be remembered across the globe (Aduhene & Osei-Assibey, Citation2021). Among the most significant worldwide health emergencies of the twenty-first century is, without a doubt, the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus began in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and quickly spread across national borders to impact communities and countries worldwide. As of 19th March 2023, the number of reported cases of COVID-19 globally was over 760 million, with over 6.8 million deaths (WHO, Citation2023). More of these recorded cases and deaths came from the United States of America (USA) and China. In Africa, more than 900,000 cases have been reported, with about 3,000 deaths (Kenu, Frimpong & Koram, Citation2020).

Ghana has also been affected by the pandemic and is listed as the fifth country in Africa with the highest reported number of coronavirus cases, behind South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria and Morocco. Ghana confirmed its first two cases of COVID-19 on 12 March 2020. Although these cases were all imported, the disease quickly spread through the communities in the country and within a week of the first cases, the country confirmed cases. As of 29th March 2023, the total confirmed COVID-19 cases in Ghana was over 171,000, with 1,462 deaths (WHO, Citation2023). Although most confirmed cases were in the two most populated cities of Accra and Kumasi, the other cities were not isolated from its spread, consequences and effects. This is primarily due to the nature of the virus. The virus is spread mainly through contact with small droplets produced by an infected person coughing, sneezing, or talking. The most common symptoms in clinical cases include fever, cough, acute respiratory distress, fatigue, and failure to resolve over 3 to 5 days of antibiotic treatment.

In order to curtail the wide and fast spread of the virus in the communities in Ghana, the government, through its executive power by the constitution, instituted some stringent measures aimed at detecting, containing and preventing the spread of the virus. These measures included: ‘a ban on all public gatherings, closure of schools, churches, mosques and other places of worship, a ban on entry for travellers coming from a country with more than 200 confirmed COVID-19 cases within the previous 14 days, a mandatory quarantine of all travellers arriving in the country, a partial lockdown of Accra including Kasoa in the Central region and Kumasi and compulsory wearing of face masks’ (Kenu, Frimpong & Koram, Citation2020). In short, because the virus spread through contact with infected persons, the government thought it right to take away some fundamental freedoms and rights enjoyed by its citizens to save the country and the rest of the population. Although the aim of implementing these measures was to prevent the spread of the virus and protect the citizens’ lives, the replica effect and consequences of these measures were somehow outrageous. As a result, the basic fundamental rights and freedom from fear and want which are essential in achieving human security as envisaged by the United Nations Framework on Human Security (2017), were abused and curtailed.

Human security has been a topical issue of concern to most policymakers and researchers due to its ability to achieve sustainable development. According to Vaughan-Williams (Citation2014), human security is necessary for development. Therefore, any threat to human security may lead to undesirable consequences on the individual’s well-being, which can adversely impact development. Buzan et al. (Citation1998) argue that human security is about survival, and any existential threat to the surviving state of humans will render them insecure. According to the Commission on Human Security (Citation2003, p4), human security could be seen as ‘… protecting the vital core of all human lives in ways that enhance human freedoms and human fulfilment. Human security means protecting people from critical (severe) and pervasive (widespread) threats and situations. It means using processes that build on people’s strengths and aspirations. It means creating political, social, environmental, economic, military and cultural systems that give people the building blocks of survival, livelihood and dignity together’. Drawing conclusions from these definitions will mean anything that will take away an individual’s freedom, livelihood, and dignity will undermine human security. Today, given the statistics on COVID-19, there is a great debate in the literature as to whether infectious diseases should be considered a threat to human, national or international security (Albert et al., Citation2021). This is because, as argued by Singh (Citation2019), infectious disease has contributed more (34%) to all deaths worldwide as compared to deaths due to war and terrorism (0.64%).

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, people’s sense of security worldwide has been challenged because of the ‘uncertainties’ posed by the rapid spread of the disease and the lack of treatment in the early days (Human Rights Centre, Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of human security, which refers to protecting individuals and communities from various threats such as disease, poverty, and violence (Duygulu, Citation2022). Globally, the pandemic has caused havoc on social and educational institutions, sparked economic downturns, increased food shortages, strained healthcare systems, and escalated personal and societal vulnerabilities. This is primarily due to the various measures that were implemented to limit the spread of the virus. These restrictions heightened loneliness and strained social relations, especially among the aged, who were deemed highly at risk (D’cruz & Banerjee, Citation2020). The pandemic did not spare employment opportunities and individuals’ livelihoods, with many people losing their jobs. This directly impacts the economic aspect of human security. For instance, over 3000 workers in Ghana lost their jobs due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions (Botchwey, Citation2021). Also, about 770,000 workers (25.7% of the total workforce) had their wages reduced, and approximately 42,000 employees were laid off during the country’s COVID-19 partial lockdown, this is according to the World Bank (Citation2020) labor report. The category of employees who were hardly hit by the COVID-19 pandemic were the daily wage earners, self-employed individuals, migrant workers and refugees across the globe. Also, the manufacturing and service industries’ jobs that have been massively affected include tourism, aviation and the hotel industry.

The untold story of the Komenda-Edina-Eguafo-Abrem (KEEA) Municipality of Ghana is like in many other parts of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and made worse several issues when it comes to human security. Although the KEEA municipality did not experience a lockdown, it was not immune to the consequences of the measures imposed by the government to fight the virus. The public health emergency unleashed by the pandemic has affected all sectors of human lives and has become a ‘human rights crisis’ affecting human dignity. The KEEA Municipality, with its distinct socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic characteristics, offers a particular framework that makes it possible to understand the effects of the pandemic in great detail. Drawing insights from KEEA allows for an in-depth evaluation of how the various dimensions of human security have been affected, especially within these communities. Also, using KEEA as a case provides insights that may be missed in more general research. It is on this score that this study was conducted. From the broad human security architecture perspective, this study examines the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on human security in Ghana, drawing inspiration from the KEEA municipality. The underlying argument is that the coronavirus pandemic is not only a health crisis but a human security crisis. Therefore, by analysing how the pandemic has affected the various aspects of human security and considering the consequences for practice and policy, this study aims to deepen our understanding of the pandemic’s overall effects and provide guidance for plans that would bolster human security in the face of any unforeseen global health emergencies.

Literature review

Before the coming to force the concept of human security in the early 1990s, nations were very concerned about the security of their territories and their sovereignty from external armed oppressions. Thus, national security was viewed in a narrow and state-centric manner, where the absence of war was seen as a secure nation (Attuquayefio, Citation2015). The primary goal of ensuring national security was to protect a country from foreign military invasions. It included maintaining a robust military posture to ward off any aggressors and protect the country from attack. However, these pedagogies are more state-centred and have little or no role in the welfare of the individuals who live within these states (Attuquayefio, Citation2015). In view of this, several researchers (Kaldor et al., Citation2007; Albert et al., Citation2021; Evans, Citation2010), including the United Nations (UN), have argued that there is a need for a new paradigm shift in the definition of national security. According to these scholars, threats to national security may not always be military in nature, but sometimes non-military threats like diseases, poverty, economic hardship and environmental degradations could pose substantial threats to the national security architecture of any country. Therefore, there is a need to see national security as human security, where state security is integrated into people’s survival and dignity. Since then, the phrase ‘human security’ has come to refer to critical security theories that challenge the state-centric security paradigm by including citizens in the process of identifying the referent objects of security (Attuquayefio, Citation2015).

Defining human security

The concept of human security became a topical issue of concern after the Cold War, with its primary goal of protecting and improving the functions of the state for the security of its citizens (Kodra, Citation2020). Human security goes beyond protecting individuals from external threats such as war, but it encompasses protecting and promoting the dignity of individuals through eradicating hunger, diseases, and the ability to meet one’s basic needs. Thus, human security takes a holistic approach to security, recognizing that traditional military and state-centric approaches are insufficient to address the complex challenges facing individuals and communities in today’s world. It emphasizes the need for a more people-centred approach to security, which places the individual at the centre of security policies and strategies. Thus protecting people from a wide range of threats, including poverty, hunger, disease, environmental degradation, political repression, and armed conflict. This is because more people have died from hunger, disease, and natural disasters than from war, genocide, and terrorism combined (Mack, Citation2005). However, despite its importance, defining human security seems problematic for policymakers and researchers. Farer (Citation2011) argues that the content of the phrase ‘human security’ varies with its users. Kaldor et al. (Citation2007) argues that the concept of human security is much contested and highly fragmented. Thus, there is no one definition of human security because different definitions may reflect diverse perspectives.

However, the Commission on Human Security in 2003 provided the initial definition of Human Security. They argue that ‘human security means protecting the vital core of all human lives in ways that enhance human freedoms and human fulfilment. Human security means protecting people from critical (severe) and pervasive (widespread) threats and situations. It means using processes that build on people’s strengths and aspirations. It means creating political, social, environmental, economic, military and cultural systems that together give people the building blocks of survival, livelihood and dignity’. The UNDP (1994) report on human development argued that ‘human security is not a concern with weapons, it is a concern with human life and dignity’. Shifting the argument and discussion from the sovereignty of nations to people-centred. According to Japanese foreign policy, ‘human security comprehensively covers all the menaces that threaten human survival, daily life and dignity-for example, environmental degradation, violations of human rights, transnational organized crime, illicit drugs, refugees, poverty, anti-personnel landmines and other infectious diseases such as AIDS-and strengthens efforts to confront these threats’.

Kaldor et al. (Citation2007) argues that human security combines human rights and human development to achieve individual and community security rather than the conventional security of states. Human security focuses more on the individual’s or group’s well-being and welfare (Iqbal, Citation2006). Gasper (Citation2005) argues that the human security discourse has three main elements: a focus on individuals’ lives, an insistence on basic rights for all, and an explanatory agenda that stresses the nexus between freedom from want and indignity and freedom from fear. The conceptual definition of human security in this study has to do with ensuring the safety and well-being of individuals, communities, and societies by addressing their various needs and vulnerabilities through the protection of physical violence, promoting economic and social development, ensuring access to basic necessities such as food and shelter, and fostering respect for human rights and dignity. Also, promoting human security will mean individuals have access to basic services such as healthcare, education, clean water, and economic and social development opportunities. Therefore, any threats that undermine these domains will mean a breach of human security.

COVID-19 pandemic and human security

Public health is a top priority for human security. Consequently, in academic literature and policy circles, pandemics and infectious diseases that threaten public health have taken on a securitized nature by describing them as a threat to security (Elbe, Citation2006, p. 126). Studies like Albert et al. (Citation2021) argue that infectious diseases like the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted the importance of human security, which refers to protecting individuals and communities from various threats such as disease, poverty, and violence. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a threat to public health and the economy of countries and posed a danger to democracy, human rights and governance. It has altered nearly every aspect of our lives affecting not just our health but also our work, food, safety, and interpersonal relationships. Umukoro (Citation2021) has opined that the coronavirus disease that emanated from China in 2019 has had devastating consequences and negative implications for human security. According to the UNDP, human security has seven dimensions: economic security, food security, health security, environmental security, personal security, community security, and political security. These dimensions are embedded in the achievements of basic human needs such as access to food, water, healthcare, and education, and all these were affected by the outbreak of the Covid 19 virus (Upoalkpajor & Upoalkpajor, Citation2020). This is primarily due to the restrictions imposed on citizens by various governments. The aim and objectives of these restrictions were to restrain the movement of individuals as they were the major carriers of the virus and, in doing so, reduce the spread of the virus. However, the consequence, as eluded earlier from these restrictions, affected many aspects of our daily lives regardless of borders or sovereignty (Boone & Batsell, Citation2001).

This viewpoint has also been buttressed by Tuffuor and Awuah (Citation2022), who opined that the coronavirus pandemic has affected humanity in all facets of life, be it social, economic, political, educational and health. For example, lockdowns and other restrictions disrupted supply chains and made it more difficult for some people to access food and other basic necessities. In Ghana, for instance, some people within restricted areas during the pandemic received food packages and free hot meals to minimize their vulnerability (Dadzie, Citation2022). This was because these individuals were forced to stay home and abandoned their daily jobs and livelihoods.

COVID-19 pandemic and healthcare system

The pandemic has also strained healthcare systems worldwide, making it more difficult for people to access medical care when needed. Menendez et al. (Citation2020) argued that COVID-19 is feared to disrupt health services and programmes and deepen the already weak health infrastructure in many developing countries. The pandemic had a significant impact on healthcare delivery in Ghana. Due to the fear of contracting the disease, most people resorted to self-medication rather than visiting the hospitals for checks and medications. In Ghana, for instance, according to Ayisi-Boateng et al. (Citation2020), there was almost a 50 per cent drop in hospital attendance during the imposition of the partial lockdown in Kumasi. According to Menendez et al. (Citation2020), during six months of the pandemic, 12,200 maternal deaths and 253,500 child deaths may occur in most developing countries. Available data suggest that during January and May 2020, Ghana experienced about a 25 to 65 per cent decline in maternity service usage (Menendez et al., Citation2020). Also, most hospital wards were full of COVID-19 patients, with increasing health workers’ exposure to the virus leading to stress and staff deficiency (Ayisi-Boateng et al., Citation2020). Thus, not only did the pandemic affect the customers of the healthcare delivery system, but it also had a significant psychological impact on the service providers who found themselves at the frontline of attempts to quell the outbreak (Tsamakis et al., Citation2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in adverse mental health outcomes throughout the world by increasing anxiety, depression, and stress levels among the general public and health care (Kindred & Bates, Citation2023). According to WHO (Citation2022), ‘COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25 percent increase in the prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide’. It is believed that most people died during the height of the pandemic out of fear of the unknown rather than contracting the virus itself (WHO, Citation2022). Due to this fear of the unknown and anxiety faced by most health professionals, their attitudes towards work and patients took a negative turn, eventually affecting healthcare delivery in most countries. Also, most pharmaceutical industries had their attention shifted from the production of the usual chronic drugs to finding vaccines to curb the spread of the virus, this eventually increased the price of most of these drugs (Gupta et al., Citation2020). Empirically, Gupta et al. (Citation2020) argues that prices of lifesaving drugs increased due to shortages in raw materials from China as a result of the disruption that occurred in most of the pharmaceutical industry. The pandemic has also placed a huge financial burden on most healthcare facilities. This is because most hospitals had their revenues reduced drastically due to low attendance (Ayisi-Boateng et al., Citation2020). Also, a significant proportion of the hospital budget has been expended on purchasing PPEs and other COVID-19-related activities.

COVID-19 pandemic and social cohesion

The pandemic may have highlighted the importance of meeting basic physiological needs to achieve human security. The disruptions caused by the pandemic may have made it more difficult for some people to meet these needs, leading to increased insecurity and instability. At the same time, however, the pandemic has also highlighted the importance of social connections and relationships (which are part of Maslow’s love and belonging needs), as people had to rely on each other for support during this challenging time. This may suggest that higher-level needs, such as social connections, are also important for achieving human security. Confirmed cases who were managed at home faced stigmatisation from neighbours as hospital-branded vehicles and PPE-wearing health workers paid visits to them. Thus, anyone who had contracted the virus or had come into touch with someone who had tested positive had to self-isolate or be forced to quarantine for fourteen days. Due to their inability to leave their homes or interact freely with others, they were socially isolated (Jain et al., Citation2020).

Social inequality and prejudice have increased as a result of the pandemic, especially targeting underprivileged communities. Subsequently, the pandemic has brought attention to societal divisions and existing fault lines, such as political polarization and economic inequality. These issues have endangered societal cohesiveness and could have long-term social and political repercussions. For instance, people’s social behaviour changed due to the anxiety and fear that came with the pandemic (Kindred and Bates, Citation2023). Thus, the fear of contracting the virus made most people withdraw from social programs and family ties. The imposition of restrictions on public gatherings affected social interactions, leading to increased social isolation and other societal problems such as domestic violence. For instance, Boserup et al. (Citation2020) found that domestic violence cases, especially against women, increased by 25 to 33 per cent globally due to the imposition of lockdowns during the pandemic.

COVID-19 pandemic and human rights

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has largely impacted the inalienable rights of humans across the globe. Thus, the measures implemented by governments, such as travel restrictions, compulsory wearing of masks and a ban on public gatherings, contributed significantly to reducing the spread of the virus, however, there has been a major concern about the possible violations of certain human rights issues. Bethke and Wolff (Citation2020) have intimated that, due to the pandemic, countries worldwide have imposed restrictions that have constrained their fundamental human rights, such as ‘freedom of assembly, association, and movement. It is within every human to have freedom of movement and association, however, due to the nature and spread of the virus, most individuals were forced to stay indoors, therefore taking away from these individuals the basic rights of movement and association. In addition, quarantine measures impacted how freely people might protest and express their opinions.

The right to work and job access was another concern to most human rights activists during the pandemic. Most individuals lost their jobs due to the imposed restrictions, which eventually affected their livelihoods and rights to survive and live from fear and want (Khowa et al., Citation2022). Moreover, to meet the social distancing directives, many businesses were forced to reduce their employees by either laying off workers or running a shift system with half or no pay. Another angle of a possible violation of human rights is the use of surveillance technologies and contact tracing to track possible infected individuals. This method, however, has sparked worries about possible violations of privacy rights as personal data are gathered and used without the individual’s consent. Bhanot et al. (Citation2021) also postulated that the devastating effects of the pandemic led to the stigmatization of those who had been exposed to the virus, which interfered with their right to privacy, equality and dignity.

The educational sector was one of the most affected sectors by the pandemic. Access to education is a human rights issue. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stipulates that ‘everyone has a right to education’. Therefore, anything that will take the child or pupil out of school violates their inherent and fundamental human rights. However, the coronavirus disease led to the closure of schools and other educational facilities, causing disruptions in global education at all levels (ACCORD Citation2020). This measure was against the backdrop of curtailing the spread of the virus infections; however, this disrupted the right to education for many students. In Ghana, for instance, the academic calendar was thrown off due to the long period of closure of educational facilities. This eventually affected the initial timelines designated for some students to complete their studies. Although most schools implemented online teaching and learning strategies to mitigate the possible effects that came along with the closure of the schools, some children were left out of these strategies due to no fault of theirs (Özüdoğru, Citation2021). Thus, students who lacked access to resources such as devices, internet connectivity, or the technical skills required for online learning could not continue their education. This further increased the inequality gap as pupils from wealthy households were more likely to have access to these resources to continue their education as compared to pupils from poorer households.

Chetail (Citation2020) has also stated that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted all segments of society, and those heavily affected are the vulnerable and marginalized, including women, children and people with disabilities. Joseph (Citation2020) reinforced this when she intimated that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused ‘a global public health emergency, a global economic emergency and a global human rights emergency’. According to Good Governance Africa, the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to other security threats such as armed conflict, placed a constraint on the respect for fundamental human rights. The Vienna World Conference in 1993 placed enormous emphasis on ‘human rights’ by stipulating that ‘states must protect and promote all human rights and the fundamental freedoms regardless of their background (OHCHR, Citation1993). The public health emergency unleashed by the pandemic has affected all sectors of human lives and has become a ‘human rights crisis’.

COVID-19 pandemic and economic security

The public health emergency brought by the COVID-19 virus has posed a serious challenge to human security worldwide by affecting economic security the most (Agunyai & Ojakorotu, Citation2021). Most economic structures and roadmaps were disrupted due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, which eventually led to many people losing jobs and income (Ahmad et al., Citation2020). According to the Congressional Research Service (CRSI) (Congressional Research Service Citation2020), the coronavirus pandemic has had a detrimental effect on people worldwide, and the impact on the economies of countries has been dire and challenging beyond all other public health emergencies faced in the century. The World Bank (Citation2020) has intimated that the African continent has slid into recession, with the economy of countries reducing by 5.1 percent in 2020, the largest comparatively in the last 25 years.

According to Ahmad et al. (Citation2020), countries like China, the UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan have experienced some significant drops in their GDP. They are projected to drop further due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because most businesses had to close down or be forced to lay off workers either due to loss in revenue or to meet the social distancing rule (Jackson, Citation2021). The consequence of this led to further hardship for individuals. The category of employees who were hardly hit by the COVID-19 pandemic are daily wage earners, self-employed individuals, migrant workers and refugees across the globe. Also, the manufacturing and service industries’ jobs that have been massively affected include tourism, aviation and the hotel industry. The pandemic also poses a significant threat to the United Nations’ sustainable development goal due to the loss of jobs and livelihood opportunities for many people who engage in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Not only has the pandemic affected the livelihoods and income of citizens, but the financial market has also received its fair share of the devasting effect of the pandemic. Thus, the pandemic has resulted in severe stock market volatility and economic instability. Moreover, Hong, Bian and Lee (Citation2021) argue that ‘the pandemic crisis was associated with market inefficiency, creating profitable opportunities for traders and speculators’. They further suggested that it has induced income and wealth inequality between market participants with plenty of liquidity at hand and those short of funds. The value of many people’s retirement savings and investments has decreased, and there is concern over the pandemic’s long-term effects on the world economy. According to Jackson (Citation2021), ‘the COVID-19 pandemic has potentially increased liquidity constraints and credit market tightening in global financial markets as firms hoarded cash, with negative fallout effects on economic growth’.

The African Development Bank (ADB) in April 2020 stipulated a reduction in GDP between 0.7 and 2.8 percentage points (African Development Bank Citation2020). Also, data from the World Bank in June 2020 indicated that sub-Sahara Africa’s economy would shrink by 2.8 percent, one of the most severe contractions to be recorded in the continent (World Bank, Citation2020). UNECA has also projected a dip in GDP growth of 1.4 percentage points for the African region, from 3.2 percent to 1.8 percent (World Bank, Citation2020). According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the world economy is projected to decrease by 4.3 percent in 2020 (UN, Citation2020). Hafez-Ghanem, Vice President of the World Bank representing Africa, has also stated that the pandemic will lead to economic, social and political challenges in most countries, and the African region will be the one to suffer the greatest (Hafez-Ghanem, Citation2020).

Campbell et al. (Citation2021) have also stated that those who have lost their livelihoods will fall prey to social vices, further worsening the insecurity in the African region. According to Aljazeera (Citation2020), this has the potential to heighten regional and sub-regional insecurity in the continent. According to the World Food Programme (WFP) (2020), food insecurity has risen to about 70%, affecting about 21 million people in the West African block. This was even before the pandemic struck due mainly to drought, intractable conflicts, and instability in the Sahel. With the pandemic’s uncertainties, an extra 22 million will be added to this number (WFP, Citation2021).

Theoretical review

The human needs theory and human rights principles underpin this study. This is because the concept of human security is rooted in the human needs theory (Suslov, Citation2022). The human needs theory is a framework that suggests certain universal needs are paramount to all humans. These needs may include food, shelter, safety, love and self-esteem. The attainment of these needs is paramount in ensuring the development of all persons. Maslow (Citation1943) as cited in Mathes (Citation1981) posits that human needs can be arranged in a hierarchy of importance and priority. Thus, Maslow identified five sets of human needs, starting with basic physiological needs like food and shelter, followed by safety needs, social needs, esteem needs, and finally, self-actualization needs. According to the theory, when one set of needs is attained, it ceases to be a motivating factor, and the individual next goal is shifted to the set of needs in the hierarchy (Maslow, Citation1943). The theory emphasizes the importance of meeting basic needs before moving on to higher-level needs in the quest to achieve their full potential. Therefore, when Mary Robinson (Citation2007) now talks of human security, she refers primarily to the ability to secure basics: health, safety and education.

Although all five steps are crucial in explaining human security and development, the first two levels are important to a person’s physical survival (Mathes, Citation1981). Therefore, the survival and security of every person are paramount to that individual before anything else (Mitchell & Moudgill, Citation1976). Hence, any threat to any of these level needs will pose severe challenges to the development and well-being of the individual, and hence they will fearlessly be resisted. Once physical needs are satisfied, individual safety and security take precedence. Safety and security needs encompass personal security, financial security, health and well-being, which, according to the UNDP, are the major dimensions and determinates in measuring human security. Meeting basic physiological needs is a prerequisite to achieving human security (Newman, Citation2020). Thus, once individuals have basic nutrition, shelter, and safety, they seek to fulfil higher-level needs. For instance, if someone is hungry or homeless, they will likely feel insecure in any other aspect of their life.

Similarly, meeting safety needs such as job security or protection from physical harm may be necessary before someone can focus on higher-level needs such as personal growth or creativity. Safety needs are connected with the psychological fear of loss of job or property, natural calamities or hazards such as the pandemic. Individuals cannot get to the topmost part of the hierarchy, self-actualization, when they live in fear or have no freedom from wants or fear. Thus, when a threat to lives and livelihoods, such as one posed by the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, is imminent, self-esteem and personal growth become irrelevant. Therefore, human needs are transformed into human security when basic needs are met, and individuals are protected from harm. Suh et al. (Citation2021) argue that the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected human needs, with the lockdown affecting higher-level aspirations and social and emotional needs. Individuals were very concerned about their safety and basic needs (Foli & Ohemeng, Citation2022).

Subsequently, the disclosure surrounding human security has moved beyond a single concept of basic human needs to incorporate human rights in the human security architecture (Gasper, Citation2005). Mahbub ul Haq and Amartya Sen were the main proponents of this argument. According to them, the role of human rights as a way of achieving human security and dignity cannot be ignored in any human security framework because they are interconnected (Alkire, Citation2003). Human beings have rights and freedom, which are fundamental to human dignity and the advancement of human capabilities. According to Sen (Citation1999) freedom from fear and wants is essential in achieving human development. However, the freedom from fear and the freedom from want, as humanistic concepts, are rooted in the definition of human rights and human security. This is why Oberleitner (Citation2002) defines human security as human rights itself. This is because human security is a broader concept comprising fundamental rights as well as basic capabilities and absolute needs. Sen (Citation1999), in its theoretical stand on development as freedom, argue that human rights should aim to increase people’s freedom of choice and ability to lead meaningful lives, which is fundamental to human development and security.

Freedom from diseases is a key component when it comes to human security. Protecting citizens amid diseases is a way for them to enjoy their freedom and rights, such as rights to live, liberty and security. Human security, as argued earlier, is about survival, is about state protecting its citizens from threat, is about ensuring that all people have the freedom and capacity to live with dignity and from free and want, and fully realize their potential (Commission on Human Security Citation2003). This definition aligns with the fundamentals of human rights, which are primarily about the respect, protection, and fulfilment of basic human rights and freedoms. The rights ascribed to every individual are inherent, and states must ensure everything possible to protect these rights. The violation of any of the fundamental human rights is a major threat to human security.

Methodology

Study area

Komenda-Edina-Eguafo-Abrem (KEEA) Municipality was selected for the study because of its unique characteristics within the region. The municipality is made up of four traditional areas or states, which have been put together to constitute a political district. The Municipality is largely made up of rural communities with few urban areas. This is worth unearthing because rural communities are predominately faced with challenges, especially when accessing essential services like healthcare, economic opportunities, and infrastructure. Therefore, there is a tendency for the COVID-19 pandemic to increase the vulnerabilities within communities. Although the majority of the people live in rural areas, 70.1 percent are literate and can read and write with understanding (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2010). According to the 2010 Population and Housing Census report, the age dependency ratio in the municipality is very high, constituting 86.8 persons per 100 people. Within the Municipality, there are more females than males, according to the Ghana Statistical Service. Given the disparate effects of the pandemic on various population segments, this demographic makeup raises important considerations regarding the vulnerabilities of certain age groups.

About 70 percent of the population is economically active, of which 93.6 percent are employed. The economically active category had 93.5 percent and 93.7 percent as the proportion of employed males and females, respectively. The occupation with the highest (42.2%) population is the skilled agricultural forestry and fishery workers. This is because fishing, farming, and salt winning are the major economic activities engaged in mainly by the residents of the Municipality. And mostly these people are self-employed without employees. The municipality also has one of Ghana’s most attractive tourist sites, the Elmina Castle. Therefore, the closure of borders may pose a significant challenge to the households whose daily survival depends on the trading activities in and around the site. In the context of human security, economic stability is a crucial component, and this demographic distribution highlights the need to analyze the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on lives, employment patterns, and overall economic resilience in KEEA.

Research design

The study adopted a descriptive type of research design, and the study’s philosophy was pragmatism. The convergent parallel mixed method was used to obtain information from respondents due to its advantages of leveraging both qualitative and quantitative data to analyse the research problem. Many researchers point out the importance of mixed methods and their advantages compared to mono-methods (Jick, Citation1979 & Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004). Mixed methods research is a methodology for conducting research that involves collecting, analyzing and integrating quantitative (e.g. surveys) and qualitative (e.g. interviews) research. This research approach is used when this integration provides a better understanding of the research problem than either of each alone. The quantitative method was used to examine the effect of the pandemic on human security, whereas the qualitative part focuses on the live experiences, perspectives and some coping strategies employed by individuals and community members as they navigate through the pandemic phases. The aim of using the mixed method was to provide a holistic understanding of the effects of the pandemic on human security.

Population and sampling procedure

The study population comprised all individuals within the study area who are above 18 years old, regardless of their political or socioeconomic characteristics. The study adopted both the non-probability and probability sampling techniques. Under the non-probability sampling technique, the study used the purposive sampling method to select key informants: the assembly members, market leaders, some core staff of the municipal assemblies, and traditional authorities. These individuals were selected because they possess reliable information on the subject matter and serve as community and opinion leaders within the municipality. A stratified sampling method was employed under the probability sampling technique. Thus, the population was divided into the four traditional states and based on that, a convenience sampling method was used to select household heads to be part of the study. In this case, respondents were approached at various locations within the jurisdiction to be a part of the sample. This is primarily due to the absence of a sampling frame. Thus, it was nearly impossible for the study to obtain the full contact list of all the household heads residing in the study area, therefore, the convenient sampling method was appropriate. In the end, 200 household heads were selected for the study across the four traditional towns. However, 163 responses were consistent.

Data collection Instrument

Interview guides were used to collect qualitative data, while an interview schedule was used to collect quantitative data from household heads. The interview guides were used to conduct in-depth interviews with the key informants, whilst the interview schedule was used to collect data from the household heads. The instrument was constructed in the English language. Thus, interviewing was the method of data collection, and the information from the respondents was recorded by the researchers. The interview schedule was appropriate because not all the respondents had formal education, so the items on the instruments were translated into their local language (Fanti and Twi), and the responses were recorded without losing the content. The interviews were conducted following the strict structure of the instrument and best practices from conventions available in the literature to obtain information from the respondents. All interviews lasted for 45 minutes on average.

Method of data analysis

The units of analysis were the key informants and household heads whose views and perspectives were needed to corroborate or contrast the literature. Using the household as the unit of analysis will allow for an extensive understanding of the phenomenon since the household is seen as a social unit where individuals within these units live and share daily experiences. Content analysis for the qualitative data followed similar themes used for the households and linked findings to literature and theory. As pertains in grounded theory, the emerging themes that had a strong base from the data were those analyzed and reported on. The interview schedule was put to the reliability test using the Cronbach Alpha coefficient. The data obtained from the field was checked for consistency of the responses, some of which were inconsistent. The consistent responses were coded and fed into a computer software known as Statistical Package for Service Solution (SPSS version 23) for the analysis. The data were analyzed with the aid of percentages and frequencies. Also, the chi-square method was also used to assess the relationship between most variables.

Ethical considerations

Ethical matters or considerations are very important for every research adventure or study. This is important for studies that involve the use of human subjects. All participants involved in the study were informed through the instruments of the purpose of the research and that information and data collected would be handled and treated with high confidentiality. Respondents were also advised that they could withdraw from the study even during the process. Specifically, the significant ethical issues that were considered in the research process included consent and confidentiality. To secure the consent of selected participants, the researcher relayed all important details of the study, including its aims and purpose, while the confidentiality of the participants was also ensured by not disclosing their names or personal information in the research. Only relevant details that helped in answering the research questions were included. Ethical clearance was sought from the University of Cape Coast Institutional Review Board. The respondents and their responses were protected using pseudonyms to ensure anonymity, confidentiality and privacy.

Results and discussion

In order to examine the effect of the pandemic on human security, the study sorted demographic information such as sex, age category, occupation, religion, educational level, ethnicity and marital status from the respondents. The results are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

presents the demographic characteristics of respondents from the study area on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their human security. From the table, we realized that 80 percent of the household heads used in the study were males, while the remaining 20 percent were females. This is so because, in the geographical location under study, males are commonly considered the head of the household (Oraro et al., Citation2018). The average age was 45 years (44, 0.431) with a standard deviation of 13 years. It is evident from that most household heads had an occupation at the elementary level, which included traders and hawkers. Also, those in the Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers were many because the study area is a fishing community. The average income for the respondents was GH₵500 (801.62, 2.685) with a deviation of GH₵250. Out of the total households used for the study 42.9 percent of them, they had their level of education up to the primary level. In comparison, 24.2 percent of the household heads have up to the secondary level in terms of education. Very few people (14%) had any form of tertiary education, whereas 2.5 percent of the household heads do not have any formal education.

COVID-19 pandemic and economic security

The study’s first objective is to examine the economic security and overall living standards that the households experienced in the pre-pandemic period. Economic security was seen as the extent to which the households have a stable and adequate income to cover their basic needs and other essentials of life, like housing and utilities (Tang, Citation2015). Respondents were given a series of items to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement regarding their socio-economic conditions before the pandemic. The results are presented in .

Table 2. Socio-Economic Situation in the pre-pandemic period.

From , the study revealed that 48.4 percent of the respondents believed that their income from employment could take care of the household better before the COVID-19 pandemic, while 2.5 percent strongly disagreed with the statement. also showed that 52.8 perecnt of the respondents believed that they could afford the basic necessities of life before the COVID-19 pandemic. This is suggestive of the fact that, before the pandemic, the households did not have any difficulty catering for the basic necessities of life such as food, shelter, clothing, and medication. Only one respondent strongly disagreed with this statement. Again, 34.3 percent of the respondents indicated that they could pay for their rent and utilities every month before the pandemic struck.

depicts the economic conditions of the households during the pandemic. Varied responses were received from the household heads. The majority (45.4%) of the respondents strongly agreed that their disposable income had been affected due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This confirms the assertion of Ahmad et al. (Citation2020) when they argue that the pandemic has had a significant impact on households’ businesses and income due to the restrictions imposed on them by the government. This reduction in disposable income may potentially increase poverty levels for individuals and families. Again, 50.3 percent of the respondents also indicated that their expenditure pattern had been affected due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3. Socio-Economic Situation in the midst of the pandemic.

Table 4. Median test.

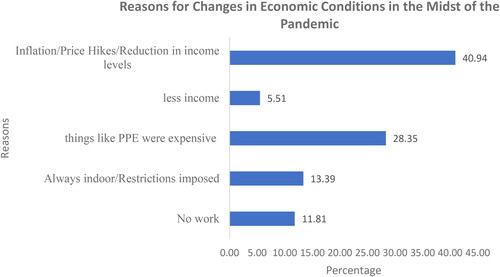

The study found the possible reasons for changes in the economic conditions during the pandemic. The result is presented in

Figure 1. Reasons for changes in economic conditions in the midst of the pandemic.

Source: Field data, 2022.

It was evident from that most (40.9%) of the respondents believed that their economic conditions were affected by the pandemic due to the reduction in income coupled with the inflations. This confirms the findings of Ikeh (Citation2019), who concluded that the pandemic’s effects on lowered income and inflationary pressures have led to several difficulties. Due to company closures, layoffs, and reduced work hours, many people and families have seen their incomes decline or completely lose their means of support. Due to the financial burden caused by this, it is now challenging to meet necessities, including food, shelter, healthcare, and education. This claim was supported by an opinion leader, according to her:

… enough financial support should have come down to the ordinary Ghanaian worker who was affected by the pandemic. Most women had to stay at home because here at the marketplace, our space is too small, so we could not adhere to the social distancing rules, so we had to run shifts, but still, some decided to stay at home because even when you come to the market, there are no people to buy. The market was very slow as most businesses (Abrem Market Leader – Female).

Moreover, more workers have been forced to stay at home due to lockdown measures, according to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (Citation2020). The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) (Citation2020) has also predicted that between 5 and 29 million people will be added to the number of people in the abject poverty bracket due to the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, while a further 17.1 percent of households will experience short-term poverty. This will be due mainly to lockdown measures that have negatively impacted employment and livelihoods with dire implications for human security (OECD, Citation2020). A study by the African Union estimates that the African continent would lose over $500 billion due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This will result in the majority of countries in the continent looking for resources to feed their growing and youthful population (Cohen, Citation2020). In fact, this prediction has come true with more than a hundred (100) countries running to the International Monetary Fund, including Ghana. This confirms the respondents’ responses that the pandemic has affected their disposable incomes. Laborde et al. (Citation2020) have also stated that poverty and food insecurity will grow exponentially across countries due to COVID-19. Save the Children (Citation2020) has stated that with the pandemic negatively affecting the economies of developed countries, its consequences on developing countries will be worse, resulting in a significant increase in poverty.

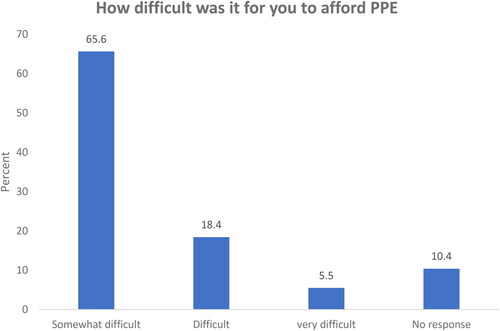

Also, shows that some (28%) household heads argue that things like PPEs that were added to the household expenditure stream imposed some financial difficulty on them compared to the pre-pandemic stage. These compounding effects have contributed significantly to changing the economic conditions of most individuals and families. PEEs became necessary logistics in combating the COVID-19 virus. PPEs were used to mitigate the risk of exposure to the virus and prevent the spread of infection from one person to another. Therefore, it became mandatory and a prerequisite for accessing some public spaces. shows the extent of difficulty for the household when it comes to the purchase of these PPEs.

shows that the majority (65.6%) of the households stated that it was somewhat difficult to afford PPEs, while about 5.5 percent indicated it was very difficult for them to purchase the PPE. Moreover, 18.4 percent stated that it was difficult to afford PPEs. Again, this reinforces earlier discussions about the pandemic negatively affecting people’s livelihoods due to lockdown effects and recession in the country’s economy. Of course, with the reduction in disposable income and extra burden being imposed by purchasing PPEs, it was obvious that some households would be highly affected. Also, because most of these households are fisher folks and are found within the informal sector without any proper savings and regular source of income that they could fall on, affording anything extra aside from food, shelter, and clothing would be difficult.

The study also highlighted household expenditure on PPEs. It was evident from the study that a household, on average, spends GH₵50 (93.60, 5.833) (8 dollars) on PPEs monthly. The spending on PPE among households ranges from GH₵50 as the minimum to GH₵1,500 as the maximum. The study further revealed a positive relationship between the amount the household spent on PPEs and their income, such that those with higher incomes tend to spend more on PPE compared to those with lower incomes, as revealed by Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.143. However, this relationship was insignificant, with a significance value of 0.127. Also, there is a weak and positive significant relationship between the amount the household spends on PPEs and the household size. Due to the growing number of people residing in larger families, there may be a higher demand for PPE. To make sure that each member of the household has a sufficient supply, this resulted in higher spending on PPE. This is because PPEs were made mandatory.

Further analysis revealed that households in the urban communities tend to spend more on PPEs than those in the rural communities. This conclusion was based on the Mann-Whitney U Test statistic of 841 and a significant p-value of 0.008. The study compared whether the amount spent on PPEs differs significantly across the various localities. The results are presented in .

It is evident from that there is a significant difference in the amount spent on PPEs in terms of the various communities. It was apparent that while the majority of the households in Edina and Komenda were spending above the average of GH₵50 a month on PPEs, the majority of the households in Abrem and Eguafo were spending below the average of GH₵50 a month on PPEs because it is rural.

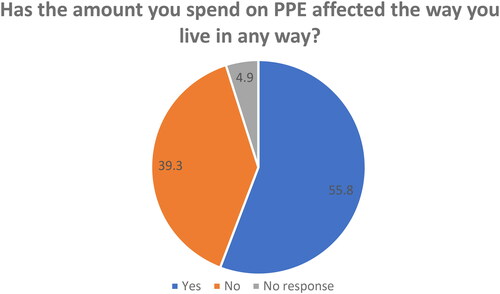

The respondents were asked if, in any way, the amount they spent on PPEs had a way of affecting the way they lived. The result from this is presented in .

Figure 3. Has the amount you spend on PPE affected the way you live in any way?.

Source: Field data, 2022.

The study revealed in that most households, representing 55.8 percent responded that the cost of purchasing PPEs has affected their income and how they live. This is trite since even before the pandemic, wages and salaries in Africa and Ghana were already low, about $1.90 per day (GH₵15), according to OECD (Citation2020). This was already low before the pandemic as compared to other regions of the world. So, to have another expenditure which was unforeseen and not budgeted for was consequently going to lead to further hardships for the family.

COVID-19 pandemic and health security

As argued earlier, the pandemic has also strained healthcare systems worldwide, making it more difficult for people to access medical care when needed. Menendez et al. (Citation2020) argued that COVID-19 is feared to disrupt health services and programmes and deepen the already weak health infrastructure in many developing countries. In view of this, the study examines the issue of whether household access to healthcare services has been affected by the pandemic. It was realized that the majority (31.3%) of the respondents indicated that they had been strongly affected due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because the fear of contracting the disease made most people resort to self-medication rather than visiting the hospitals for checks and medications. This confirms the findings of Ayisi-Boateng et al. (Citation2020), with the conclusion that in Ghana, there was almost a 50 per cent drop in hospital attendance during the imposition of the partial lockdown in Kumasi. These responses are to be expected since, according to the OECD (Citation2020), about 81 percent of the world’s workforce has currently been affected by the impositions of restrictions implemented by various governments to check the transmission of the coronavirus.

A response from the Municipal Health Directorate confirms these findings of Covid-19 disrupting health services and programmes. According to this worker

The number of maternal and antenatal visits decreased significantly due to the fact that parents were afraid to come to visit the hospital because of the fear of contracting the diseases (Municipal Health Directorate Worker - Female).

This finding confirms the study of Ayisi-Boateng et al. (Citation2020) and Menendez et al. (Citation2020), as they argue that during January and May 2020, Ghana experienced about a 25 to 65 per cent decline in maternity service usage. This is because most people resorted to self-medication rather than visiting the hospitals for checks and medications due to the fear of contracting the disease.

COVID-19 pandemic and education

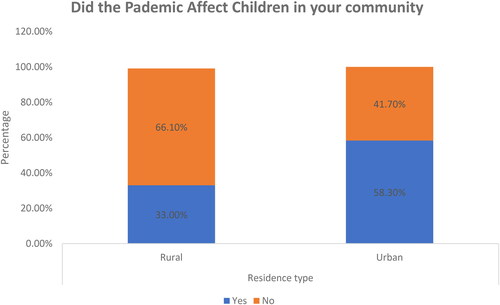

Further, the study sought to find out the impact of the pandemic on education. The result is presented in

shows that most children in urban areas were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic compared to their colleagues in the rural community. The study again revealed that most children, regardless of their residence type, did not participate in online studies when schools were asked to close down during the pandemic. Thus, from the study, 60 percent of the household heads stated that their children could not participate in any of the online teaching and learning. When asked about the impact of the pandemic on education, one community leader, being an Assembly member, said,

… this COVID-19 pandemic has placed a huge devasting effect not only to our economic lives, as we all know, but also on the lives of our young ones in terms of their education. The majority of the children within my community had to stay away from school and books for a year simply because schools were closed down. This closer of schools added to the problems we are already facing here with the children not attending schools. And because the schools here, too, could not organize online studies for the kids because most of the children did not have the means to have those online classes. So, they had no choice but to be roaming about from morning to evening, and some had to resort to fishing (Komenda Assemblyman - Male).

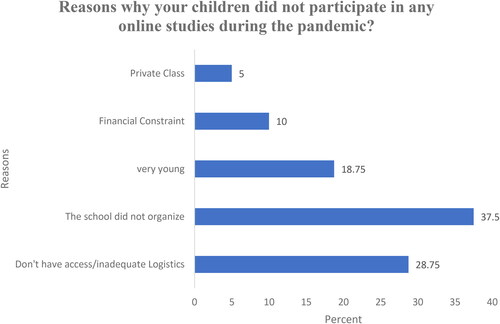

As indicated in previous discussions, the pandemic has affected all sectors, including education. School-going children in the urban centres are affected more since most children use the internet and computers to study in these areas, and not being able to go to school and not having these facilities at home means their learning abilities will be hampered. Moreover, because most economies had slid into recession, as predicted by the World Bank (Citation2020) and the OECD (Citation2020), most parents were experiencing financial challenges due to some restrictions that were introduced. Lockdowns also meant teachers could not go to work for any classes to be organized. These children could not participate fully in any of the online teaching and learning platforms provided by the Ministry of Education or other stakeholders, and the reasons that were ascertained from the respondents are presented in below.

Figure 5. Reasons why your children did not participate in any online studies during the Pandemic?.

Source: Field data, 2022.

The study revealed that most (37.5%) of the students did not participate in any online study because their schools did not organize it for them. Furthermore, 28.75 percent of the households interviewed did not allow their children to participate in online classes due to inadequate logistics such as tablets and mobile phones. These findings are consistent with Özüdoğru’s (Citation2021), where it was evident that some children were left out of the online strategies due to no fault of theirs but because they lacked logistics. Thus, students who lacked access to resources such as devices, internet connectivity, or the technical skills required for online learning could not continue their education. This further increased the inequality gap as pupils from wealthy households were more likely to have access to these resources to continue their education as compared to pupils from poorer households. Also, 18.75 percent of the respondents claimed their children were young, thus explains why they could not participate, while 10 percent could not participate due to financial constraints like the cost of data. The view of an opinion leader in the community supported these findings. According to the opinion leader;

not all parents in this community have the means to purchase a laptop, mobile phone or tablet for their wards to partake in online studies. Therefore, the major constraints were financial problems. Even though some had to use other means to learn like engaging private teachers at home and the e-learning platform on the television, very few people participated in that (Edina Assemblyman – Male).

COVID-19 pandemic and social cohesion

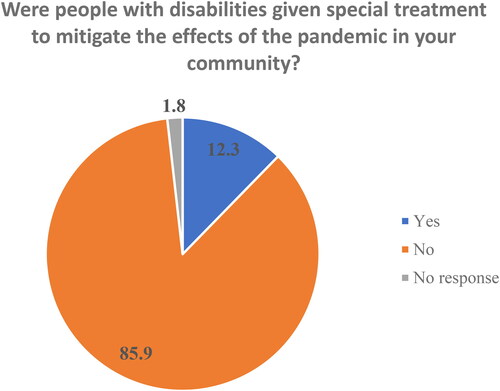

Social inequality and prejudice have increased as a result of the pandemic, especially targeting underprivileged communities. Some vulnerable groups, like disabilities and older people within the communities, were heavily affected (Chetail, Citation2020). depicts responses from interviewees on whether people with disabilities were given any special treatment to mitigate the effects of the pandemic in the community.

Figure 6. Were people with disabilities given special treatment in your community to mitigate the effects of the pandemic?.

Source: Field data, 2022.

shows that the majority of the respondents, constituting 85.9 percent said that people with disability, although affected by the pandemic, were not given any special treatment. However, 12.3 percent indicated that people with disabilities were given special treatment. Again, this does not deviate much from global trends since, as economies were heavily affected, resources to the needy, marginalized and vulnerable groups also dwindled. Also, most individuals with disabilities have some health complications which may require constant or frequent health care, however, without any extra support or medical assistance, coupled with the fear of even contracting the virus, poses further health complications for these individuals. Poor community support systems have made more people with disability feel more alone and vulnerable due to unattended special needs (Choruma, Citation2007).

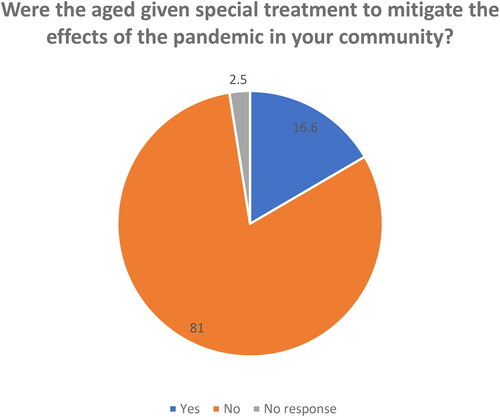

also shows the responses on whether any assistance was extended to older people. The results presented do not differ from the story of the disabilities.

Figure 7. Were older people given special treatment to mitigate the effects of the pandemic in your community?.

Source: Field data, 2022.

In , it is realized that the majority of the respondents, constituting 81 percent stated that no support was extended to the aged. A slightly higher number of household heads, 16.6 percent, indicated that the government extended some support for older people. During the initial stages of the pandemic, the government directed the various Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) to take steps to mitigate the hardships of vulnerable groups in society. This is because many people, including older people, are financially insecure. However, these initiatives were not reflected in the responses provided by the respondents. These findings are also consistent with Chetail (Citation2020) argument that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on all sections of society, with those significantly affected being the vulnerable and marginalized, such as the aged, women, children and people with disabilities. This is why Joseph (Citation2020) summed up the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic as ‘a global public health emergency, a global economic emergency and a global human rights emergency’. Restrictions imposed by countries due to COVID-19 brought about loneliness, which affected social relations with the aged being affected most (D’cruz & Banerjee, Citation2020). The disease also prompted the isolation of elderly individuals from their loved ones, leading to loneliness and loss of affection (Gyasi, Citation2020). In the view of the UN (Citation2020), the COVID-19 pandemic intensified the plight of the already bad situation of the vulnerable, marginalized, and excluded in society.

Covid-19 pandemic and human rights

Bennoune (Citation2020) believes that the uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic have made it a ‘cataclysm for human rights and a foundational challenge to international human rights law’. The author has again intimated that the widespread transmission of the disease and the measures introduced by governments to stem the spread have been ‘a threat to all the rights guaranteed by international law nearly everywhere’ (Bennoune, Citation2020). In Ghana, Parliament passed the Imposition of Restriction Act, 2020 (Act 1012), which was assented to by the President, as well as the Imposition of Restrictions (COVID-19) Instrument, 2020 (E.I. 64) adopted as a mitigating measure to curb the spread of the virus (Republic of Ghana Citation2020a). Added to the above, public and private places of work were directed to operate on a shift system and adopt a virtual mode for organizing meetings. All protocols given by the Ministry of Health were to be strictly adhered to. In responding to the Public Health Emergency on hand, Ghana’s government invoked the derogation clause under Article 31 (10) of the 1992 Constitution to curtail the enjoyment of the civic liberties of the citizenry. Therefore, the imposition of restrictions laws limited the enjoyment of some fundamental freedoms. The ban on the free movement of persons, ‘temporary quarantine, public gatherings, demonstrations and protests, the closure of schools and places of worship’, although it was for public health and safety, affected some human rights principles.

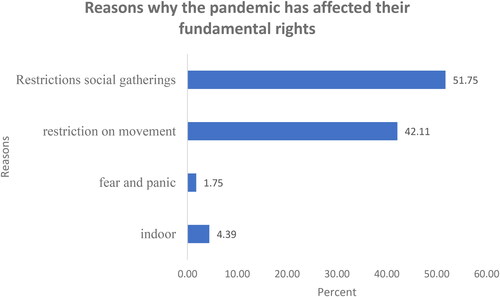

A critical objective of the study was to determine the pandemic’s impact on fundamental human rights. This is because human rights play a crucial role in achieving human security and dignity. Human security can be seen as a human right because of its interconnectedness (Alkire, 2003; Oberleitner, Citation2002). The study revealed that the majority (76.1%) of the households concluded that the pandemic had affected their fundamental human rights and freedom, especially regarding the freedom of movement, association, and even participation in social and religious gatherings. The reasons are presented in below.

It was evident from the study that most (51.75%) of the households’ rights were curtailed due to the imposition of the lockdown and the ban on social gatherings. This ban on social gatherings led to social isolation, which affected the well-being and security of many people. This is because the absence of social connections that resulted in physical isolation and loneliness led to the development of several mental and emotional health issues like depression and anxiety (Loades et al., Citation2020 & Agunyai & Ojakorotu, Citation2021). Also, some (42.11%) households were of the view that restrictions on movement were against their fundamental human rights. General fundamental freedoms guaranteed under both international laws, as well as enshrined under Article 21 of the 1992 Republican Constitution regarding taking part in processions, freedom of movement, and religious gatherings, were all curtailed to check the spread of the disease. Some participants stated that the fear of contracting the disease affected their rights to movement and association with others. For example, one community opinion leader stated as follows:

… we were not able to go to work regularly. We had to stay indoors always, which always caused emotional trauma to the majority of us (Abrem Traditional Leader – Male)

During the imposition of lockdown measures globally, the Human Rights Committee intimated that countries could derogate from their obligation to protect human rights by adhering to the Siracusa Principles regarding emergencies and even this should be the last resort when all avenues are exhausted (Human Rights Committee Citation2020). Joseph (Citation2020) has opined that ‘respecting the enjoyment of human rights is an end in itself, as compared to being a means to an end and also not inherently utilitarian’. Erasmus (Citation1994) has also indicated that anytime a limitation is placed on a right, the significant features of the said right should be ‘maintained and not extinguished’. Moreover, the limitation must be construed narrowly or strictly in favour of the rights bearer (Erasmus, Citation1994). Addadzi-Koom (Citation2020) has emphasized ‘the need for a rights-based approach’ to the COVID-19 pandemic, where states and non-governmental actors must take urgent steps to empower the people and not criminalize people who violate lockdown measures.

According to OHCHR (Citation2020), COVID-19 Response:

Emergency powers should be used within the parameters provided by international human rights law, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which acknowledges that States may need additional powers to address exceptional situations. Such powers should be time-bound and only exercised temporarily to restore a state of normalcy as soon as possible.

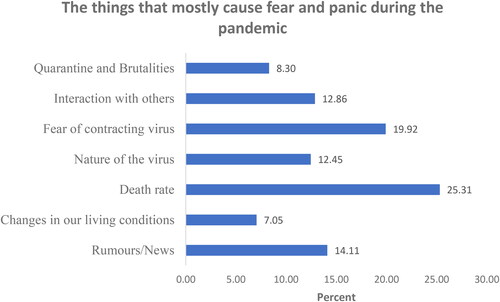

presents what caused the respondents to fear and panic during the pandemic.

From , it became evident that the rising death toll due to the pandemic was the major contributor to fear and panic in the citizenry, as the majority (25.31%) of the households indicated. Further, the fear of contracting the virus was another significant factor that caused fear and panic in people. Because there were no vaccines during the initial stages, these brought about uncertainties that heightened their fears and caused panic due to deaths from other parts of the world. These findings reveal a significant threat to human security because the individual’s health security has been challenged. Kaldor et al. (Citation2007) argued that the health dimension of human security is not just the absence of diseases or sickness, but it encompasses strong healthcare systems and the psychological well-being of the individual. Therefore, the fear and panic emanating from the rising death toll have the propensity to undermine the individual’s sense when it comes to security and stability. This can lead to several psychological problems, which could affect the mental health and overall well-being of the individual in the long term (Commission on Human Security, Citation2003). Other identifiable factors that caused fear and panic during the pandemic were rumours, fake news, and the high cost of living (Loades et al., Citation2020).

It was also evident from the study that although the majority (80%) of the households claimed they were not involved or did not know any member in the community who suffered from any brutalities by security personnel during the pandemic, some (20%) of the households one way or the other experienced or know a member who suffered brutalities from the security personals. This is important to unearth because several studies (Alindogan, Citation2020; Human Rights Watch, Citation2020) have argued that police brutalities and abuses in some parts of the world, including Ghana, increased significantly during the pandemic. This is because, during the pandemic, some people were forced to go on mandatory quarantine after contracting the virus for the safety of others, but those who refused were brutalised or assaulted by security agencies Studies (Alindogan, Citation2020; Human Rights Watch, Citation2020). Also, during the partial lockdowns in Ghana, some people were brutalised and assaulted by state security for disobeying the restrictions imposed. Wurth (Citation2020) has stressed that the destructive and complex nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to threats posed to public health, has also become a significant challenge to the guarantee of international human rights as stipulated in most international instruments. This is due to the ‘instability and fear’ unleashed by the pandemic, which has ostensibly led to human rights abuse ‘such as–sexual and gender-based violence’ and brutalities (GANHRI et al., 2021). Although the majority (94.5%) of the households or members of the communities never experienced any form of abuse domestically during the pandemic, about 4.3 percent of the households either experienced abuse or know a member of the community who had experienced abuse and this form of abuse are mostly marital and financial issues.

According to Anderson et al. (Citation2021), while the COVID-19 inspired legislations are legitimate as mandated by the Constitution, Public Health Act, 2012 (Act 851), the Imposition of Restriction Act, 2020 (Act 1012) and the Imposition of Restrictions (COVID-19) Instrument, 2020 (E.I. 64) are justified in the protection of public health, its application has constrained privacy rights, freedom of movement, peaceful assembly, expression and association which invariably has negated civic space (Republic of Ghana Citation2020a; Republic of Ghana Citation2020b; Republic of Ghana Citation2020c).

Conclusion

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the weakness of most economies and the unprepared nature of disaster by most countries. The COVID-19 pandemic was not only a health crisis but also a human security crisis affecting economic stability, social cohesion, and fundamental rights and freedoms. The pandemic has reshaped our understanding of human security discourse, highlighting the interconnectedness between infectious diseases and human well-being and dignity. The growing number of deaths toll and the fear associated with contracting the virus brought an atmosphere of uncertainty and anxiety among many individuals, challenging the very essence of personal and health security. Also, movement restrictions, such as the ban on social gatherings, affected community ties and social bounds, which eventually heightened the anxiety and depression levels of most households. This situation re-echo the fact that as we navigate our way out of the pandemic, there is the need to consider emotional and mental health in our healthcare priorities and not only physical health.