Abstract

Literature reveals that cultural appropriation (CA) involves taking over another group’s cultural belongings without consultation, informed consent and compensation, and without proper recognition or respect for that culture which has potential to distort the indigenous cultures. The purpose of this study is to examine the effect of CA on the cultural garment weaving industry in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The research adopted mixed methods approach with concurrent convergent research design. Data were gathered from weavers (292), consumers (200) and concerned officials by using questionnaires, KIIs (8), FGDs (3) and observation. Purposive, simple random and availability sampling method were used to determine resourceful interviewees from the weavers’ association and government agencies, respondents’ from the weaving community and consumers from the population, respectively. The study utilized descriptive and inferential statistics (Pearson correlation and multiple regression) to investigate the quantitative and narrative analysis for qualitative data. Results showed that there is CA which was driven by money making rather than respect; there is no legal and institutional framework that enable preservation, protection and commercialization of the authentic cultural designs, CA negatively impacts income and cultural identity of the owners and distorted the cultural values embedded in these designs. Thus, in order to ensure legal protection of the cultural clothes designs and rights of the weaving community, the society, weavers, weavers’ association and the responsible government authorities should work together before such sporadic wisdom and skills get vanished.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The authors believe that communities residing in different parts of the World have their own unique philosophies and beliefs about space, time and truth. These philosophies and beliefs are reflected in the artifacts such communities use in their day-to-day activities in life and maintained through generations. Cultural diversity is the spice of life, the base for tourism and the cause for interaction among the World population. Therefore, assigning legal protection to cultural intellectual properties (CIPs) benefits both insiders and outsiders of the culture in question. Because, it enables insiders to get recognition for their cultural wisdom and feel valued for what they have. On top of that the compensation outsiders pay enable insiders maintain their livelihoods. It could also encourage communities disclose other beliefs they have and develop artifacts. In that manner, cultures could evolve from within.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the study

Culture is reflection of a groups’ identity (Tan, Citation2009; Schein, Citation2004). The human world is filled with diverse cultures that dictate acceptable styles of behavior, such as dressing, singing and greeting, feeding and communicating with people. Cultural elements are not creations of the existing generation at any given period of time and space, rather they are inherited from ancestors (Memon et al., Citation2022; Tan, Citation2009). Cultural intellectual properties (CIPs) are part of the spiritual and cultural identity of the Indigenous people and intrinsic element of their cultural heritages (Moody, Citation2019; Tan, Citation2009). The unique motifs and arts of cultural clothes are one of the cultural heritages that call for legal protection from getting appropriated by outsiders (Vézina, Citation2019; Disele et al., Citation2011; Young, Citation2005).

Currently, there is a growing research interest and debates on vitality of assigning intellectual property (IP) rights to cultural innovations. Article 31(1) of the United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples (2007) provided that ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage,…. as well as the manifestations of their cultures, including designs,……and protect and develop their IP over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions’

Similarly, the African regional intellectual property office (ARIPO) enacted the Swakopmund protocol on Protection of TK and Expressions of Folklore within framework of ARIPO (Citation2010). In its preamble, the protocol justified the need to assign legal ownership of communities on their cultural intellectual properties (CIPs), importance of these CIPs for scientific development, the drawbacks of cultural appropriation (CA) and the need to develop a sui generise law that fits to the special nature of CIPs.

In many countries, intellectual properties are protected through formal legal mechanisms and institutions. However, CIPs do not assume such privilege due to their special features that do not fulfill the legal requirements of authenticity, fixation, reproducibility, authorship and originality (Shand, Citation2002). As a result, they are mostly being considered as parts of the public domain to which everyone has free access (Fredriksson, Citation2019). The CIPs status as public domain properties is criticized based on the principle of tragedy of the commons (Hardin, Citation1968). As a result, there are arguments for provision of intellectual property (IP) protection to CIPs (Vézina, Citation2019; Zhao, Citation2018; Tan, Citation2009). Based on this claim, some nations have already protected their CIPs by enacting relevant laws and establishing concerned institutions (Memon et al., Citation2022; Fredrikson, Citation2019). To release the tension between the arguments for and against CA, Young (Citation2005) proposed that unless it causes profound offense on the members of the appropriated culture, CA should not become immoral just because outsiders have appropriated CIPs from insiders.

Ethiopia is one of the culturally diversified countries in the world. The cloth type and vestume is one of the ways diversity is manifested in the country. Article 41(9) of the FDRE constitution provides that ‘the state has responsibility to protect and preserve historical and cultural legacies and to contribute to the promotion of the arts and sports.’ The art of weaving has been practiced in Ethiopia for thousands of years. Ethiopians, especially women, in both the rural and the urban areas, wear hand-woven cotton clothes with decorated edges ‘Tibeb,’ especially for private ceremonies, public and religious holidays. These clothes are venerated as inextricably connected icons of nations and nationalities (Alhayat et al., Citation2018).

According to Debeli et al. (Citation2023), the Ethiopian Government gave special attention to the textile sector as a potential area for investment and education. To that end, policies and strategies are designed, institutions are established, mechanisms are set in place and cooperative agreements are signed with other countries (Yan et al., Citation2023). Despite this fact, imported imitations of the Ethiopian cultural clothing designs are flooding over the local market since 2018. The researchers observed women wearing these imitations for various celebrations, just as if they are the fashions of the day. Belete (Citation2018) explained that weavers of traditional clothes are innovating intricate design patterns but the benefit from their innovation is only within the lead time; until it gets copied by others. This is so because their creations are not protected by the formal IP system of the country. The reason for this lack of IP protection is the lengthy process for examination and unaffordable costs of registration. Abiyot (Citation2020) also conducted a detail review on the availability of legal protection for CIPs in Ethiopia. The researcher found out that legal frameworks are already set at the international and regional levels. But, in Ethiopia, the CIPs are left unprotected.

However, the aforementioned researchers do not address how absence of IP protection for CIPs could expose them to CA and the repercussions it may have on cultural authenticity of the imitated clothes and income of the Weaving community. Therefore, this study attempted to bridge this research gap by assessing the manner CA took place on the cultural weaving industry, the weavers’ reaction toward CA, the current legal topography of the nation as well as the perception of users toward the AUCCs and the imitated cultural clothes (IMCCs). Further, the study analyzed the effect of CA on authenticity of the IMCCs and income of Weavers.

Scope of this study is delimited to the Gullele sub-city of Addis Ababa, where most of the traditional cotton garment Weavers, the Dorze community, are concentrated (Belete, Citation2018). Particularly it covers Shiromeda, which is the largest traditional clothes market in the city. Conceptually, this study dealt with the issues of CIPs legal protection, CA, and users’ behavior. It employed descriptive and explanatory research designs with a mixed methods approach. Time wise, this study is a cross-sectional one whereby data were gathered and analyzed at a single point in time, in the year 2022.

The researchers’ believed that findings and recommendations of this study will benefit people engaged in traditional garment weaving in particular and all Ethiopians in general by proposing how legal protection could be assigned to CIPs and ensure perpetuation of communities’ cultural identity and unique creativity. Tourists will also benefit from this study because, legal protection of CIPs could enable preservation of diverse cultural heritages that could attract tourists to purchase them as a unique resources of the place they have visited. Moreover, it also benefits government agencies engaged in job creation for sustainable livelihoods. If CIPs get legally protected and secured, the youth could get formally trained on how to weave traditional cotton garments and supply them to the market. Besides, findings of this study will help other countries with such unique CIPs understand the value and mechanisms of assigning legal protection to their CIPs.

1.2. Research hypothesis

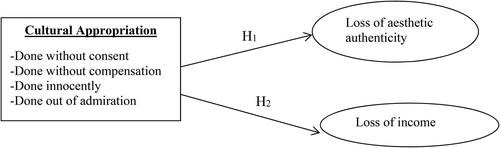

The following hypothetical propositions were made in order to analyze the effect of CA on authenticity of cultural clothes and the level of income of Weavers.

H1: Cultural appropriation distorts authenticity of the cultural clothes at a statistically significant level.

When CA takes place, the appropriators reproduce the cultural artifacts in a distorted manner. Appropriators replicated the traditional ‘Tibeb’ designs and the fabric in a totally different context, with a power-loomed technology. Such distortion in texture, feel and appearance of an IMCCs affects the feeling and sense of cultural identity of subscribers to the culture in question.

H2: Cultural appropriation reduces the level of income of Weavers at a statistically significant level.

Weaving is an artful, slow process of making unique cultural clothes. Handmade cultural products deserve to be expensive for two basic reasons: the emotional-cultural attachment of people toward their cultural clothes and the high level of time, energy and price of the threads used for their production. When the power loomed textile factories came up with mass-produced imitations of such revered clothes; users may prefer the imitations for their lower price and their similarity with the AUCCs. As a result, the market share for AUCCs will get reduced compared to that of the IMCCs; which automatically results in reducing the income of Weavers.

2. Review of related literature

2.1. The concept and theory of cultural appropriation

CA is said to have been practiced by Europeans at the time of colonization in the 16th and 17th centuries (Fredriksson, Citation2019, Vézina, Citation2019; Tan, Citation2009). Rogers (Citation2006:474) defined CA as ‘the use of a culture’s symbols, artefacts, genres, rituals, or technologies by members of another culture.’ Furthermore, Sharoni (2017:10) as cited in Vézina (Citation2019:5) stated CA as ‘the act by a member of a dominant culture of taking a CIP whose holders belong to a minority culture and repurposing it in a different context, without the authorization, acknowledgement and/or compensation of the CIP holder(s).’

Nonetheless, scholars in the area do not have consensus on whether CA should be allowed or prohibited in the textile and fashion industry. Proponents of CA view the act as an intrinsic element of the fashion and textile industry (Heyd, Citation2011:38; Cox & Jenkins, Citation2005; Matthes et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, authors who argue against CA firmly reflect the idea that taking a CIP of another without consent of its owner is equated with theft which is an act both morally wrong and legally punishable (Fredriksson, Citation2019, Vézina, Citation2019; Tan, Citation2009). Those authors who consider CA as morally offensive and harmful summarized its consequences as loss of potential income, loss of authenticity and loss of cultural identity (Heyd, Citation2011).

However, Young (Citation2005:141), took a qualifying stand by asserting that, ‘artists who appropriate the culture of another, not for the sake of self-realization and inquiry but purely for pecuniary purposes commit an offensive and morally wrongful act; particularly, when an un-offensive ways of creating the art are available.’ According to Young’s perspective, there is nothing wrong with taking CIPs of others so far as the intention is for scientific inquiry and self realization. When it comes to taking CIPs of others for peculiary benefits, it is still ok if it is done in an un-offensive way. The un-offensive way of taking CIPs of others could be represented by reaching consensus and getting formal consent of the owners. Therefore, CA done for pecuniary benefits in the absence of consent of the owners may result in misrepresentation and distorted appearance of cultural artifacts as well as violation of sacred values of the community in question. It is in this case that CA should be legally prohibited. There are three popular theories that explain the consequences of CA on the Owners of CIPs.

2.2. Theories of cultural appropriation

2.2.1. The aesthetic handicap theory

Aesthetics in this sense refers to the assumptions, values and principles guiding production of a certain traditional artwork. When outsiders appropriate a cultural art from another culture and re-produce it in a different context, they obviously produce some sorts of aesthetic failures (Vézina, Citation2019; Young, Citation2006). Artistic cultural works are composed of contents of the culture within which they are produced. This scenario guides the observer how to see and interpret that artwork (Tan, Citation2009). However, loss of authenticity occurs when the appropriators engage in reproducing CIPs with out caring for the cultural philosophies, values and meanings embedded within and attached to those works of cultural arts (Vézina, Citation2019; Tan, Citation2009). Thus, the replicated works of CIPs will have distorted appearances which misrepresent subscribers of that culture.

2.2.2. The cultural harm theory

Cultural properties that could be subject of appropriation are diverse. They could be categorized into five as material, non-material, stylistic, motif and subject appropriation (Young, Citation2000). Heyd (Citation2011) explained the harm that could be caused by CA on the cultural group as it goes to the extent of questioning their survival as a distinct group with unique philosophies and values regarding reality, truth, time and space (Schein, Citation2004). Shand (Citation2002) believes that CA has ability to silence voices of the Indigenous groups. A typical example could be the case of the Swastika symbol. Before Hitler used it, the Swastika has been used as a symbol of good fortune in almost all cultures of the world. Coca Cola was highly attracted to this symbol and adopted it as a benign symbol of good luck and fortune (Campion et al., Citation2014). However, today the symbol lacks its original cultural meaning. That is why, Heyd (Citation2011) emphasized that ‘misappropriation and misuse [is] not simply a violation of moral rights leading to a collective offense, but a matter of cultural survival for many Indigenous peoples’. In other words, CA harms members of the appropriated culture because they are systematically detached from the meaning, they placed on their work of art. Moral rights allow the Indigenous people the right to disseminate, to be considered as collective authors or creators and to keep integrity of their creations (Harms, Citation2018; Memon et al., Citation2022).

2.2.3. The diamond theory of competitiveness

Porter (Citation1990) proposed that competitiveness of a particular industry mainly depends on the joint effects production factors, demand conditions, related and supporting industries, corporate strategies, structure and competition and government and chance. The production factors used in the traditional weaving industry are the Weaver’s skill and cultural knowledge, limited finance and traditional weaving tools. Hence, it is hard for Weavers to compete with the power-loomed textile industries who appropriate their cultural products and reproduce them in mass. Eventhough people may have sentimental attachment to the AUCCs, they may shift their preferences to the IMCCs due to low price, better quality, peer pressure and availability in various colors and sizes (Ogbonnaya & Ogwo, Citation2016; Eze & Bello, Citation2016; Rani, Citation2014).

The supply and value chain interactions among industries require them to support each other (Yan et al. (Citation2023). However, if this interaction is weak among industries related to weaving, the Weavers’ competitiveness will be affected due to lack of adequate production factors. Further, Weavers need to understand the capacity and behavior of competitors so as to design appropriate strategies and structures that enable them stay competitive. Since, the main focus of weaving cultural clothes is preservation, promotion and commercialization of culture, government has an exceptional role to play by enacting relevant policies, strategies and laws that guard the industry from fierce market competition. On top of that, government needs to be agile to respond to technological changes and the attributes of globalized markets that may affect competitiveness of the weaving industry. Otherwise, due to their better position in all the aforementioned dimensions of the diamond theory, appropriators may control the market and make Weavers’ lose income and affect the source of their livelihoods. This may force Weavers quit their weaving business and shift to other activities.

2.3. Factors that affect users’ behavior

The concept ‘user behavior’ refers to users’ buying characteristics reflected in their decisions and actions in purchasing products and services (Eze & Bello, Citation2016). Rani (Citation2014:52) defined user behavior as it refers to ‘selection, purchase and consumption of goods and services for the satisfaction of their wants.’

Basically, two theories namely the distinctiveness theory and the social interaction theory dictate how users’ decision-making on purchase runs out (Rajagopal, Citation2011). According to these theories, the individual purchaser strives to strike balance between two seemingly conflicting interests. On one side, there is a need to get assimilated to a group by adhering to its norms including the dressing code whereas on the other hand the individual has an urge to feel unique and distinct from the group. The social interaction theory also emphasizes on the point that clothing is a mode of aesthetically presenting oneself to a group. But this is highly influenced by prevailing cultural values that guide peer evaluations (Yin et al., Citation2019).

Various empirical studies were conducted to figure out practical applicability of these theories on the ground. A study carried out by Rajagopal (Citation2011) on consumer culture and purchase intentions toward fashion apparel in Mexico concluded that brand value, brand reputation, price, simulation facilities, personalization possibilities, store attractiveness and interpersonal influences are factors that affect consumers’ preference in buying fashion apparel. Based on these findings, Rajagopal recommended that the basic assumptions of apparel retailing should be transformed from individual referenced indicators to value and lifestyle perceptions driven by peer influence and socio-cultural forces.

Rani (Citation2014) also stated that there are wide arrays of factors that intervene in the buyer’s decision-making process. These are cultural, social, personal and psychological factors. Specifically, Islam et al. (Citation2014) conducted a descriptive study to identify factors that influence female consumers’ fashion apparel buying behavior in Bangladesh. Findings indicated that brand status, attitude, popularity, image, premium, self-respect and influence of reference groups are factors that determine female consumers’ choice in the apparel industry.

Ogbonnaya and Ogwo (Citation2016) study revealed that product quality, distribution and promotion are determinant factors of customer preference to foreign textile materials. They concluded that the predictor variables have positive relationship with customer satisfaction. Likewise, Eze and Bello (Citation2016) found that age, quality and level of income are factors that affect consumer choice in the clothing market.

2.4. International conventions and legal frameworks for protection of CIPs

According to Yu (Citation2012), protection of cultural creations is high on the agenda of the United Nations’ World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO). This is reflected in WIPO’s efforts in establishing an inter-governmental committee and conducting various negotiations on how to come up with a legal framework on the protection of CIPs (Vézina, Citation2019; Schuler, Citation2013). At the international level, UN’s (Citation2007) declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples is the basic legal framework that provides for the need of legal protection for CIPs of Indigenous peoples of member states. Moreover, the 2018 WIPO’s article on the protection of traditional knowledge (TK) and traditional cultural expressions (TCEs) gave choice to nations to protect their CIPs either under their general IP law or by promulgating a sui-generis law (Vézina, Citation2019; Asri, Citation2018).

The general IP law requires fulfillment of materiality or fixation, originality, authorship, reproducibility and authenticity in order to assign IP protection to a certain IP work for which legal protection is sought (Shand, Citation2002). Besides, protections given under the general IP laws are time bounded, and they get lapsed at the end of the given period of time. However, the sui-generis protection of CIPs was crafted in a way that makes it compatable with the special nature of CIPs. Among others, it provides for a perpetual legal protection to CIPs so far as the group claiming right over a certain CIP exists. In some cases, the CIP work remains protected even when such a group gets extinct from the surface for different reasons. For instance, Taiwan’s law on CIPs assigns that right to all existing Indigenous people of Taiwan (Karjala & Paterson, Citation2017). An other example of such suigeneris protection could be the case of the Navajo nation in the USA and the Mexi community in the Southwestern part of Mexico. These communities got sui generis legal protection for their unique clothing designs and patterns in which their identity, philosophies and values are embedded (Fredriksson, Citation2019; Vézina, Citation2019).

In Africa, an ARIPO was established since the 1970s. Membership to the ARIPO is open to member states of the African Union or the economic commission for Africa (ECA). Initially, the purpose of this regional body was to avoid wastage of resources by separately dealing with IP issues in each country and to capacitate the continent with its own IP system. However, gradually, it was learned that the CIPs of the continent’s diversified communities are at risk of being misappropriated by outsiders. As a result, ARIPO enacted the Swakopmund protocol (2010) on the protection of TK and expressions of folklore as a guideline for ARIPO member states on how to protect their CIPs. As a member of ARIPO, Kenya took the lead by enacting a comprehensive CIPs law to protect her CIPs and sustainably maintain the economic and socio-cultural benefits of her people (Abiyot, Citation2020).

2.5. Empirical cases of CA

These days, the fashion and textile industry is getting inspired by contents of cultures of ethnic groups found in different parts of the World (Vézina, Citation2019; Cox & Jenkins, Citation2005, Young, Citation2005). Due to absence of legal protection, CIPs they are considered as part of the public domain to which everyone has free access to use, dispose and abuse (Vézina, Citation2019; Karjala & Paterson, Citation2017). As a result, there are many cases of appropriation of CIPs in different countries. The following cases are typical examples on how nations respond to the act of CA.

2.5.1. Japan’s Kimono

Japanese women were wearing kimono with its entrenched cultural meaning for years. But later, from 1982 to 2012, the demand for high-end kimono market gets collapsed due to introduction of western fashion styles that attract the majority. When French designers came up with new lines of fashion inspired by the Japanese kimono, Japanese textile industries welcomed it happily. They reciprocate by showing their fascination and accreditation of the western styles (Hall, Citation2015).

2.5.2. The Metis people

Valentino, the Italian well-known brand collection, was criticized for appropriating the Metis peoples’ of Canada beaded and embroidery flower designs in its resort 2016 collection, without allowing the Metis people a chance to work for it. Since the artistic legacy of these people is inseparable from their economic lives, the act of Valentino contains both moral and economic harm. When these embroidered or beaded designs are imitated and get mechanically printed on textiles, they lose the meaning and identity, hence this scenario creates disassociation between the design and the making, the creator and the wearer. It is plagiarism, meaning distortion and humiliation to the originators (Vézina, Citation2019; Zhao, Citation2018).

2.5.3. The Navajo case

The Urban Outfitters have used the Navajo nation (living in Arizona, Utah and New Mexico) name without asking for the community’s permission. The court decided that urban outfitters should pay monetary compensation to the Navajo nation based on the size of sale accruals from the Navajo themed products dating back to 2008. It also gives injunctive order that prohibit urban outfitters from using the Navajo name in any products thereafter. Finally, in 2016, the Navajo nation and urban outfitters reached an agreement.

2.5.4. The caribou skin parka case

An Australian designer KokonToZai created a caribou skin parka for the 2015 runway. The designer has appropriated a former style designed in 1920 by a shaman named Ava. Relatives of the shaman have the story and photograph of that design and they know that it was designed by their ancestor. The shaman tried to contact the designer on different occasions. But it was not possible. The final resort they found was to air the issue on the media. Consequently, retailers began to take it off their shelves which they were selling for about $925 Canadian dollars. Finally, the designer issued public apology for his act of appropriation.

2.5.5. The Maori people’s case

A New Zeeland swimwear manufacturer named Moontide came up with a new line of women’s swimming suit with curvilinear designs taken from the traditional Koru art of the Maori people. The designing process was done in consultation with elder representative of the Maori people. Series of negotiations were conducted regarding the use of the motif. Accordingly, the manufacturer was bind by the obligation to ensure commercial viability and cultural respect. This agreement was realized via the manufacturer’s act of providing royalty based on the sale accruals from that product. When the fashion gets debuted in the Sydney fashion week of 1998, it attracted considerable press attention due to its ethical and exemplary act of apparently proper handling of the rights and interests of Indigenous peoples (Shand, Citation2002).

2.5.6. The Maasai people

It is said that more than 1000 companies have used Maasai imagery and iconography without getting permission of the people including well-known fashion brands Diane von Furstenberg, Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein, have allegedly each made more than US$100 million in annual sales using the Maasai name and visual culture (Rosati, 2017, cited in Vézina, Citation2019). This is an economically significant loss of benefit to holders of the designs. The Maasai, an Indigenous group living in Kenya and Tanzania, own trademarks whose licensing revenue was, by 2013, as high as US$10 million a year within a decade. Using a trademark in connection with CIP-based fashion creations, for instance, can enhance the creation’s reputation as part of a marketing strategy to promote its distinctiveness and authenticity and to prevent others from using the trademark in connection with competing products. Except in the case of Japanese Kimono, the above cases indicate the culture consciousness of Indigenous people and the moral response of the appropriators as well as the media.

To sum up, appropriating CIPs of others, for pecuniary benefits, with out their consent is a morally wrong and a legally publishable act. In such cases, nations have the right and obligation to protect their CIPs either by extending the general IP law or by enacting special suigeneris laws. Such laws should place requirements and guidelines on how outsiders could use CIPs of communities for economic benefits. The empirical literature on cases of CA shows that, nations and communities have already began implementing such laws and getting recognition for their cultural products. Thus, the only way to legally use CIPs in the fashion industry is based on negotiations and consensus reached between owners of the CIPs and the fashion and textile industry.

2.6. Historical background of weaving in Ethiopia

Eventhough weaving is said to have been practiced in Ethiopia for thousands of years, the exact time and location when and where weaving was started is not known (Biruk & Dereje, Citation2021). Rather, there are two contradicting propositions made by senior weavers. These propositions are highly related with the territorial expansion undertaken by Emperor Minilik-II (1889–1913). On one side, it is stated that ‘the Emperor took professional weavers from Shewa along with his troops to different newly integrated parts of the country and let them teach the skill to residents of those areas.’

The second argument is that ‘once the Emperor arrived around the Gamo area, Southern part of the country, he observed the weaving skill and how important it is to the nation’s civilization. Then, he brought professional weavers from Gamo to Shewa and made them teach weaving to residents of different localities.’ Further, weavers around Axum are said to have learned the skill from Gamo personalities who went there as troops during the war of Adwa in 1896.

Senior weavers from the Gamo community explained that, after the war of Adwa, some of the Gamo soldiers settled in Ankober, North Shewa and commenced weaving there. After certain years, many weavers came from Gamo to Addis Ababa and settled on foots of the Entoto mountain, which is known as Shiromeda, located in the Northeastern part of Gullele sub-city.

There is another proposition that weaving was started around Wollo. Due to draught and famine, people from Wollo migrated to the southern part of the country, especially Gamo and began producing Buluko and Gabi. At that time, weavers from Wollo did not know about motif or ‘Tibeb’, their work was simply a plain fabric. Looking at their weaving, the Gamo people learned how to weave and innovated the decorated edges ‘Tibeb’ by mixing colors. Hence, the current beautifully decorated ‘Tibeb’ is result of gradual modifications of that Gamo peoples’ wisdom. Even though there is no tangible proof to these propositions, the Gamo people are highly recognized for their refined quality motifs of traditional clothes (Mathiszig, Citation2015, Gibson, Citation1998).

Cotton, the basic input for weaving Ethiopian traditional clothes is said to be cultivated on the Ethiopian soil and hand spun by Ethiopians for thousands of years (Alhayat et al., Citation2018). According to Belete (Citation2018), the traditional weaving material was made up of locally available woods such as the eucalyptus and bamboo. These days, it is getting replaced with modern weaving materials with similar basic structure but made up of metal which is easy to be dismantled, move from place to place and re-assembled.

Weavers produce various traditional clothes namely netela, wraps of various sizes known as Kuta, Gabi and Buluko; Qemis (dress), Meqent (waist band), Yeangetlibse (scarf) and men’s traditional clothes. Except the Qemis (dress), others are stoles that vary in size and thickness in a descending order from Buluko to the scarf and waist band (Alhayat et al., Citation2018; Belete, Citation2018) ().

These clothing items are made up of pure cotton and they are white in color. Normally, the edges of these traditional clothes are decorated with colorful bands of jacquard design, often made from silk, rayon, acrylic, wool and metallic threads like silver and gold. This decorated design is traditionally known as ‘Tibeb.’ The Tibebe is made up of three-dimensional forms and the two-dimensional features, such as lines and colors and it is designed in a way it reflects philosophies, values and culture-oriented aesthetics of the community (Kashim, 2013, cited in Alhayat et al., Citation2018).

There are two types of fabrics produced by traditional weavers namely ‘menen’ and ‘saba.’ These fabrics vary in texture. The saba could be produced in various colors and it has relatively thick texture whereas menen is light textured and white in color. Saba is mostly used to make scarfs, dresses as well as men’s traditional suits.

Cultural clothes are mostly used during special occasions, such as religious and national festivals and private ceremonies. As per the nature of the occasion, the way traditional clothes are worn transmit messages that are understandable to the community whose members have subscribed to that collective meaning (Schein, Citation2004). Belete (Citation2018, p.93) provided a typical example of how the vesteme of the netela (shawl) conveys different messages to the spectators who should be subscribers to that meaning either as member of that group or as an outsider who has experienced those cultural beliefs (Young, Citation2006). Belete’s statement runs as. When a woman is going to church, the netela is opened and the pattern lies on both shoulders. For funerals, as a sign of mourning, the netela is worn with the patterned end to the face. In casual contexts, the pattern is worn over the left shoulder. (p.11). Thus, these cultural clothes are CIPs of all Ethiopians since time immemorial and, as cultural artifacts, serve to express their philosophies and beliefs about different events in life ().

2.7. Conceptual framework of the study

When CA is done without consultation with the owners of CIPs, in the absence of their informed consent and without compensating them, it constitutes an illegitimate act even though it was done innocently and out of admiration and inspiration by the unique features of those cultural artifacts. If the market gets overwhelmingly flooded by IMCCs, it will have two detrimental repercussions on members of the culture from whom those works of art are appropriated. These are loss of authenticity of their artistic cultural works and loss of potential income. Loss of authenticity happens due to the appropriators’ lack of concern to incorporation of all cultural features in the imitated products; their focus lies on how to reproduce these clothes in mass and in a cost saving manner. That was why the final products come up with a different look, feel and texture. These scenario distorts the cultural meaning embedded within the AUCCs and causes cultural harm. On the other hand, mass presence of such IMCCs in the market affects competitiveness of the Weaving industry. Because, Users’ demand may shift to the imitations due to lower prices, color diversity, ease to care for, durability, wearability and availability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research approach and design

This study employed a mixed methods research approach (both quantitative and qualitative data). The reason for employing a mixed methods approach in this study was the objective of the study and the nature of the questions demand the implementation of both methods. In addition, in our quest, it is more effective and compatible than a single method to capture the views and experiences of weavers, users/customers and law enforcers (Creswell, Citation2009, Gray, Citation2004). Regarding the research design we employed convergent parallel design in which both qualitative and quantitative data are collected at a roughly the same time (Creswell, Citation2009). It is an efficient design, in which both types of data are collected during one phase of the research at roughly the same time. Each type of data can be collected and analyzed separately and independently, using the techniques traditionally associated with each data type. This lends itself to team research, in which the team can include individuals with both quantitative and qualitative expertise (Pallant, Citation2011; Fraenkel & Wallen, Citation2005: 443; Creswell, Citation2009).

3.2. Population of the study

There are 52 MSEs which has 20–25 members. All are engaged in weaving cultural garments. Most of these weavers are found concentrated in the government provided working premises located in a particular place known as Shiromeda. The total number of weavers in 52 MSEs is 1219 (1117 male and 102 female). Thus, the target population of this study was weavers, users of cultural clothes, the weavers’ association and government authorities whose missions are related with culture, heritage and IP rights.

3.3. Sample size determination and sampling technique

Based on the mathematical sample size determination formulae set by Kothari (Citation2004), 292 weavers and by applying Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007:123) formulae N > 50 + 8 m, 200 users were selected from the population. Therefore, the sample size of this study for survey questionnaire was 292 weavers and 200 users of cultural clothes.

Simple random sampling technique was employed to select actual weaver respondents and availability sampling was used to identify users’ of cultural clothes.

Simple random sampling was used because it gives each person to have an equal chance of being included in the sample and to use the advantage that the research data can be generalized to other populations (Bryman, Citation2012). Convenience sampling was employed because the readily availability of the respondents and using it reduces researchers time investment and selection cost.

In addition to the survey, the study utilized Key Informant Interviews and Focus Group Discussions to gather qualitative data, including interviews with members of wavers’ association, Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Heritage Protection Authority, and IP Office. Similarly, in order to get rich data, three (3) FGDs which comprise 24 participants were conducted with senior weavers. KIIs participants from aforementioned organizations were purposively selected because their experience and knowledge regarding the legal and policy matters toward the cultural heritages. FGD participants were also selected purposively because of their role as coordinators at work premises level. Regarding data collection, 492 questionnaires were distributed by the researchers. Participants were given the questionnaire with the introductory cover letter and before they decided to be a participant in the research, they were told that the survey was anonymous, voluntary and confidential. The researchers also interviewed eight participants at their office and conducted focus group discussions with 24 senior weavers. They had not participated in the quantitative data gathering. Both the interview and FGDs were recorded by voice recorder and interview led for 50 min while FGS took two hours. The researchers emphasized informed consent before starting the interview as well as focus group discussions and each participant signed a consent form.

Furthermore, the researchers understand that in the interview process, the researchers must not have any bias toward any of the participants. Hence, in this study, we have been open and honest with interpretations of the data of both the interviews and the survey research. Especially when interpreting the data from the interviews and FGDs, we stayed in the middle and not pay more attention to any one of the participants.

Two types of questionnaires, filled by weavers and users were prepared in English language. Both instruments were translated from English to Amharic language and from Amharic to English by professional who was proficient in both languages. Questionnaires were distributed to sampled respondents by personally visiting and then collected after a week going physically. Responses for all variables were measured using 5-point Likert scale (5) Strongly Agree, (4) Agree, (3) Slightly agree, (2) Disagree and (1) Strongly Disagree.

3.4. Reliability and validity of the instruments

The Cronbach’s alpha, which calculates the average of all possible split-half reliability coefficients, was used to systematically test reliability of the instruments. The standard figure for reliability test is 0.70. However, there are instances in which lower figures up to 0.60 are taken as acceptable for reliability (Bryman, Citation2012; Field, Citation2009).

The study evaluated the reliability of CA and users’ perception questionnaires through a pilot test with fifteen weavers and 10 users, and all comments were considered before the actual data collection. As presented in , all items of the questionnaires have beyond the minimum threshold alpha coefficient values, hence, they are reliable. At the questionnaire preparation stage, validity was also checked by repeated scrutiny of the contents of the questionnaire against the theoretical and conceptual underlining of CA, consequences of CA and users perception.

Table 1. The reliability test of the items.

3.5. Data analysis

The study applied the mixed methods ways of data analysis. Regarding the quantitative data analysis, the collected questionnaire was checked for its completeness, edited and analyzed using SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The quantitative data was analyzed and interpreted by using both descriptive (percentages, frequencies, means and standard deviations) and inferential methods of data analysis. Descriptive statistics used to assess the CA of the hand-woven cultural designs, weavers’ reaction toward CA, the influence of CA on the AUCCS, users’ perception and the demographic data of respondents while the inferential statistics (Pearson correlation and standard linear regression) were used to test and analyze the relationship between CA and level of weavers’ income and authenticity of the IMCCs, effects of CA on overall income and authenticity and perception of cultural clothes users.

Qualitative information from FGDs, KIIs and document review were analyzed and themes were identified. Then interpretation was done with reference to the objectives of the study. Then, the findings were presented textually using the narrative technique. Both data were mixed or integrated at the interpretation and discussion part of the study.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Response rate and demographic data

Besides the interview and focus group discussions, a total of 292 questionnaires were distributed to weavers with the return rate of 80% (235). To this study, sex, age, level of education, family size, acquaintance with weaving and years of experience in weaving were considered as relevant demographic characteristics of respondents. Majority 198 (84%) of the respondents were male and the age category of the majority is 114 (49%), 120 (51%) were grades 1–8 while 78 (33%) were grades 9–12 completed. While, the family size of majority 160 (68%) of the respondents is 1–4 members, followed by 63 (27%) of 5–8 members.

Regarding cultural clothes users’, among 200 questionnaires distributed, 86% (172) were returned and utilized. While the whole respondents were female, majority (89%) of the respondents are aged between 18 and 42, and 62% had their first and second degree, and majority of the respondents earn less than 5000 birr, while 34% earn 5001–1000 birr per month.

Weaving as an industry requires the right knowledge, skill, and attitude. Majority of the respondents, 220 (94%) learned the skill from their ancestors through experience. Whereas, the remaining few 15 (6%) learned weaving because of education and training they got from technical and vocational education and training (TVET) institutions. Majority of the respondents 99(42%) have experience of 16 years and above followed by 55 (24%) of 11–15 years of experience. Therefore, respondents of this study were well experienced in the job and know the internal and external environments of the weaving industry.

4.2. Effect of CA on the cultural garment weaving industry

4.2.1. CA of the hand-woven cultural designs

A questionnaire composed of ten items on manner of CA, weavers’ reaction and authenticity of the IMCCs was administered to weavers. The responses on these issues are presented in and the analysis is done using both descriptive and inferential statistics.

Table 2. The manner of CA.

The data revealed that the process of CA did not (220, 94%) begin by recognizing the weavers’ right over the designs and securing their willingness to the act, and 227 (97%) of the respondents also disagreed whether the appropriators gave formal recognition to Ethiopian weavers during the act of appropriation. This shows that the appropriators have simply duplicated the designs without placing any mark on the fabrics that declare sources of the designs. Moreover, 225 (96%) of the respondents declared that the appropriators do not paid compensation which portrays that CA took place without compensating the owners.

While 196 (83%) of the respondents showed their disagreement that CA was done due to admiration and respect for the designs, 205 (87%) confirmed their disagreement whether the cultural appropriators committed the act innocently. Thus, majority of the respondents believe that the foreign companies have done the appropriation intentionally to get undue enrichment at the expense of Ethiopian weavers and the community who used to produce and guard the designs starting from an unmemorable period.

Similarly, the interviewees and FGD participants revealed that to appropriators, CA is a lucrative business. They said that ‘had it been out of admiration, they would have used it themselves in its authentic form’. However, during the FGD, some participants raised the idea that ‘the appropriators might be innocent; they may have no information on whether these traditional designs have owners. Instead, it could be some greedy Ethiopian merchants who have sold the traditional designs to foreigners for industrial printing and duplication.’

The official from the Ministry of Culture and Sports (MoCS) stated that ‘there is a rumor that it is not the foreign companies who have copied and reproduced the authentic cultural designs. Instead, they were given the designs and a business order by Ethiopian merchants engaged in importing textile products from the foreign markets to Ethiopia.’

Furthermore, the FGD participants elaborated that there is no legal and institutional framework that enable preservation, protection and commercialization of the authentic cultural designs. This scenario makes them highly exposed to imitation by any interested party. People come to the Weaver’s workshop and buy the AUCCs and copy the design.

Hence, whether the AUCCs designs were copied by Ethiopian merchants or the foreign textile companies, what matters here is that the act of CA was done without securing informed consent of the weavers, without giving them formal recognition and paying compensation. Moreover, it was done to get profit by distorting the cultural values embed within the AUCCs and in violation of the rights of the weaving community.

In their response to the open-ended items, respondents stated that weavers oppose the act because; it unlawfully took their intellectual creations and heritages away. The act could aggravate joblessness and poverty. Many weavers are leaving their profession and getting employed as security guards for different organizations.

The weaving industry uses threads of various types for production of the AUCCs. FGD participants emphasized that lack of adequate thread of various types is the main challenge they face in the weaving process. Even though we know that threads named Saba, Mennen, Suuf and Werqezebo are imported from India, China, and Taiwan; weavers do not know who the importer is. Instead, weavers get market access to these materials at the fifth stage (Importer-whole seller-Retailer-Brokers-weavers). Involvement of multiple actors in the thread provision makes unnecessary delay and increase in the price of the materials without adding value. They added that they do not have direct contact with the main suppliers of inputs and buyers of their woven fabrics. A great role is played by brokers who benefit from the unnecessary price increase.

There are also domestic factories producing the thread types known as Salayish, Asmera and Weldeyes. However, weavers do not have direct access to these domestically produced threads for basically two reasons. The first one is presence of shortage of cotton as row material for production of the threads. These days, it is said that pure cotton is being exported in huge volumes to abroad. The other reason is that the thread supply chain is occupied by merchants/firms who are also the importers of the foreign made threads. Hence, they sell these inputs via the long value chain where prices increase due to change of hands; without adding value.

The official from the MoCS stated that lack of cotton and other yarns required for production of cultural clothes is another great challenge for the weaving business. Only 35% of the industry’s demand for cotton is supplied from domestic sources whereas the rest 65% is imported. On top of that, the other decorative threads ‘Tibeb and Werqezebo’ are imported from China, India, Taiwan and South Africa. This increases the price of cotton and hence the price of the finished cultural clothes.

The value chain of the inputs is also unreasonably elongated and complicated. At every step in the value chain there is price increment without adding value.

Since, weaving is a labour-intensive industry; it could serve as an occupation for many people. In that sense, it could also contribute to minimization of the rural-urban migration. Despite that, adequate attention is not given to this sector. For instance, there is no tax exemption or deduction on imported inputs used by the weaving industry compared to treatments and support given to other investment options. The MoCS has a special agency named Heritage Preservation Authority, but the emphasis this agency gives to cultural clothing designs is almost null. They did not clearly determine which aspects of the weaving products needs preservation, and which aspects could be commercialized.

One of the FGD participants explained that:

I spent the past 40 years in this profession. In Shero-Meda approximately more than 300, 000 people are engaged in weaving and related jobs. But the government overlooked us. The government does not facilitate the market. We have no right even to sell what we produced. If you come to Sunday market, you will see how police chase us not to sell our products. We are not getting protection from concerned bodies. Besides, the weaving profession is not culturally respected. Even spouses who choose to wear the authentic cultural attires for their wedding and feels fulfilled and decorated may; when they sow a Weaver say “…. that archaic Shemane….

For instance, AUCCs of a fine quality standard could be sold by weavers for 2000–2500 birr to merchants. The merchant sales that fabric for 5000–6000 birr to users, then, the tailors and embroiders also, adding value costs the user on average, especially up to 4000 birrs (depending on complexity of the sewing and the embroidered design). Finally, the user gets the AUCC for about 10,000 birrs.

In conclusion, the FGD participants stated that:

This special weaving skill is naturally given to Ethiopian weavers. The appropriators mass produced the authentic cultural cloth designs in a distorted manner, and they provided it to the market for a lower price. We try to voice our claims to responsible bodies of the government, but there was no positive response. Our intention is not to stop sharing the knowledge and skill we have, but we want recognition and compensation from everyone who uses the designs for commercial purpose. If it is going to happen, CA should be done by giving due recognition to the weavers and respect to protection of cultural values and ownership right of the community.

4.2.2. Reaction of weavers to appropriation of the cultural designs

When CA took place, a positive, neutral, or negative reaction is expected from the weaving community. The cases of the Navaho community in the USA and the Sharma in Australia are good examples whereby the privileged communities get re-instated to their rights through court order. On the other hand, the Japanese were not that much sensitive about appropriation of their Kimono by the western fashion industry. On this regard, weavers were asked to state their feelings toward the act of CA and their responses are presented in .

Table 3. Reaction of weavers to appropriation of the cultural designs.

According to , 175 (75%) of the respondents stated that they feel irritated when they see the appropriated designs displayed in the cultural clothes’ market. Likewise, 158 (67%) respondents confirmed that they feel irritated when they see the IMCCs worn during holidays. This shows that the public’s act of wearing IMCCs during holidays creates resentment in the weavers. This was further explained by one of the FGD participants who underlined that ‘the Ethiopian AUCCs are normed as clothes of honour and pride and holiday celebrations should be accompanied by wearing these clothes; not the ordinary machine-made fabrics.’

In addition to considering CA as a morally wrong and legally punishable act; Vézina (Citation2019), Fredriksson (Citation2019), Heyd (Citation2011) and Tan (Citation2009) identified grounded factors that trigger owners/stewards of those CIPs resentment about the act of CA. These were affecting their cultural heritages, religious values and the means of their livelihoods. In relation to these implications, weavers were asked about what makes them feel irritated on the act of CA.

While 187 (80%) feel irritated because these designs are cultural heritages that require legal protection, 174 (74%) do not feel good because the designs have religious contents, and 223 (95%) revealed that the CA’s effect on their income is the cause of their irritation. In their response to the open-ended items, respondents stated that weavers oppose the act because; it unlawfully took their intellectual creations and heritages away. The act could aggravate joblessness and poverty. Many weavers are leaving their profession and getting employed as security guards for different organizations.

In conclusion, the FGD participants stated that:

This special weaving skill is naturally given to Ethiopian weavers. The appropriators mass produced the authentic cultural cloth designs in a distorted manner, and they provided it to the market for a lower price. We try to voice our claims to responsible bodies of the government, but there was no positive response. Our intention is not to stop sharing the knowledge and skill we have, but we want recognition and compensation from everyone who uses the designs for commercial purpose. If it is going to happen, CA should be done by giving due recognition to the weavers and respect to protection of cultural values and ownership right of the community.

4.2.3. Effect of CA on the weaving industry

Since this study adheres to the conservative approach toward preservation, protection and promotion of culture; effect of appropriation of the AUCCs from the weaving industry was measured from the perspectives of income, authenticity and distortion of cultural identity. Respondents’ response toward this issue is presented in .

Table 4. The effect of CA on the AUCCS.

According to , 193 (82%) respondents agreed that CA has reduced their earning from the weaving business. While 177 (75%), 201 (85%), 187(80%) and 189 (81%) of the respondents perceive that CA has created unfair competition in the market, resulted in cultural identity distortion, resulted in distortion of the original values and the appropriators’ lack of concern toward preservation of the values is the cause of distortion, respectively.

Hence, it could be concluded that the practice of CA influenced the weavers’ life in different ways. It has reduced their income, created unfair competition, distorting cultural identity and above all the appropriators’ have no care whether the cultural property is preserved or not.

4.2.4. The relationship between CA and weavers’ level of income and authenticity of the IMCCs

As a preliminary stage to inferential analysis, all the assumptions are met without violations. To ground the descriptive findings, an inferential analysis was done using correlation in order to scrutinize the direction and strength of relationship that exists between CA and level of weavers’ income and the level of authenticity of the IMCCs. Results of the correlation analysis are displayed in .

Table 5. Correlation analysis between overall CA, income and overall authenticity.

Accordingly, the correlation coefficient between CA and the level of weavers’ income is −0.299 and that of CA and authenticity of the IMCCs is −0.319. These results are statistically significant at p = 0.05. The negative (−) sign indicates that the variables are correlated in an opposite direction. That is, an increase in the level of CA results in decrease of the weavers’ level of income and level of authenticity of the IMCCs. The other essence of these correlation coefficients is that they tell us strength of the relationship between the variables. According to Cohen’s standardization of correlation coefficients (r) (Cohen, Citation1988, pp. 79–81) as r = 0.10–0.29 = small; r = 0.30–0.49 medium and r = 0.50–1.0 large; the strength of the relationship between CA and income of weavers (−0.299) and between CA and authenticity of the IMCCs (−0.319) is of a medium size.

4.3. Effect of CA on weavers’ income and authenticity of the IMCCs

A standard linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the effect of CA on Weavers’ level of income and the level of authenticity of the IMCCs. Results of this analysis are presented below in .

Table 6. Effect of CA on overall income and overall authenticity.

As it could be grasped from the data in , CA affects the level of Weaver’s income by 8.9%, F (1, 233) = 22.87, p < 0.005. The beta value of the analysis shows that a one-unit change in CA results in decrease of income by 0.367 with standard error of 0.077, which is significant at p < 0.05. Similarly, CA affects the level of authenticity of the IMCCs by 10.2%, F (1, 233) = 26.36, at p < 0.005. The unstandardized beta coefficient also shows that a one unit increase in CA decreases the level of the IMCCs authenticity by 0.295 with a standard error of 0.058.

According to Cohen (1988, p. 535) the validity of effect sizes varies based on the context in which the study is embedded. That is, an effect size of 1% could be as valid as the effect size of 50% depending on the nature of the variables and seriousness of the consequences of the variation caused on the dependent variable by the independent variable. Based on this proposition, even though it is statistically significant, the 8.9% effect size of CA on the weavers’ income could be trivial and insignificant. Because, weavers could get more income by weaving AUCCs that attract the economically well to do groups and sell those products for higher prices. However, the 10.2% effect size of CA on authenticity of the IMCCs will have serious consequence of distorting the cultural and religious values embedded within the AUCCs and washing them away from the public memory on a gradual basis ().

Table 7. Results of hypothesis testing.

4.4. Users’ perception toward authentic and imitated cultural clothes

The perception that users have toward a certain product or service determines their behavior in buying it. In this study, the users’ perception toward authentic and IMCCs comprises four dimensions (users’ sentimental view toward the AUCC, differences between the AUCCs and the IMCC, timeliness and nature and availability). presents the total mean values of the four dimensions of users’ perception.

Table 8. Users’ perception toward authentic and imitated cultural clothes.

Users’ sentiment toward the AUCCs include issues such as understanding the cultural values of cultural clothes, frequency of wearing it on holidays, how these embedded values enable the users’ to communicate their unique identity to the world, beauty of AUCCs, level of feeling satisfied when wearing the authentic cultural clothes, and its usability for a longer period of time. The average mean (M = 2.6; SD = 0.63) revealed that users have adequate knowledge about the values of cultural clothes, which helps to show their unique identity; mostly they use it for holydays and feel content whenever they wear AUCCs. Though they declare AUCCs are beautiful, they slightly agreed with the ability of cultural clothes to be used for a long period of time.

The second dimension of the users’ perception was focused on comparison between authentic and IMCCs designs in terms of understanding their difference in substance, quality and price. Accordingly, the average mean value (M = 2.63; SD = 0.69) shown that majority of users understand the deference between authentic and IMCCs, approve the quality of authentic and believe authentic clothes are more expensive than imitations. Therefore, the above findings tell us that users’ do not have problems regarding awareness and sentiment toward the values of AUCC and knowing the difference between AUCC and IMCC.

Timeliness and nature of cultural clothes are measured by forwarding items such as whether users believe that IMCCs are the fashion of the day, comfortable and wearable for both occasion and casual days, light in nature and could serve for longer time without losing its quality. According to , the average mean value regarding timeliness and nature of IMCCs (M = 1.9; SD = 0.88) shown that certain percent of the users believe that wearing IMCCs is the fashion of the day, they wear it both at occasion and casual days, and it is easy to manage. However, majority of the respondents do not feel comfort wearing the IMCCs and they do not believe that IMCCs could serve for long period of time without losing their quality.

The fourth dimension comprises availability in different body sizes, everywhere at all open markets, with different colors, and it is cheap compared to the authentic ones. The average mean value (M = 2.7; SD = 0.77) of this dimension revealed that availability of the IMCCs in different body sizes, accessibility at all open markets in different colors and their lower prices are attracting people to buy and use IMCCs. Particularly, the price for IMCCs recorded higher mean implying that price of imitated clothes is cheaper than the authentic ones. Thus, price could be the most determinant factor for users’ preference of the IMCCs over the authentic ones.

This claim is further strengthened by the finding that the income of majority (57%) of the respondents is less than 5000 birr per month. Hence, it could be concluded that the great price difference between AUCCs and the IMCCs is the main factor behind users’ preference for imitations over the authentic ones.

In the open-ended part of the questionnaire, respondents were asked about their views on the act of CA as well as the reason behind users’ preference for imitations over the authentic ones. Regarding CA, respondents have two contradicting views. One group said that ‘they feel sorry, because Ethiopian cultural dresses (Tibebs) reflect the long-standing tradition and customs of Ethiopians. Ethiopians should have detail understanding about their culture and be proud of what they have. CA has resulted in distorted images of the authentic clothes ‘which does not feel Ethiopian.’ Respondents in this group added that:

Hand-woven cultural clothes are next to none. However, majority of the users donot have awareness about the imitations of cultural clothes. Instead, they consider the imitations as having the same cultural value and meaning. On top of that, there are few people in society who considered wearing woven traditional clothes as backward and old fashioned. These groups deem the imitations as modern and fashionable. Besides, they have negative perception to the weaving profession. That is why they want to buy the machine-made imitations of cultural designs.

Most of us decided not to train our children in weaving. Why should they suffer? The toil and exploitation should stop on me. I am suffering; my father and my great grandfather have suffered too. I fear after few years the profession will vanish. As you know, there are more than 600,000 people earning from this industry. If we stop the weaving, hundreds will starve. Our life is bitter.

While the other group reflected the idea that:

We are in an era of globalization and the free market economy. Within this environment, only industries that cope up with the changing demands could sustain in the market. Instead of criticizing the act of CA, respondents in this group appreciate the competence of foreign companies in copying the intricate designs and availing the products for all income groups. They said that the act helped low-income groups get the feel of equality in wearing the cultural clothes. Literally, it enables them buy clothes with intricate cultural designs that are on average valued for 15, 000-25,000 birr in the authentic form for 1500 birr in the imitated form. Thus, CA should not be criticized.

People have already assigned religious and cultural vitality to cultural clothes. Hence, it is not lack of awareness or concern about the cultural values and meanings embedded within the AUCCs that force people buy the IMCCs, instead, it is the sentimental attachments they have towards the AUCCs that drive them buy the imitations. They buy it because, it resembles to the AUCCs, which is too unaffordable for them. CA enables them to satisfy their cultural urge to feel Ethiopian.

4.5. The legal topography of CIPs in Ethiopia

Symbolic cultural artifacts are intellectual creations of nations or communities of a certain nation; hence they deserve to get legal protection. At the international level, emphasis is given to protection of CIPs either by the general IP law such as copy rights and trademarks or by enacting a special law, suigeneris, that accommodates the specific features of CIPs. In Ethiopia, IP rights are protected by the copy right and neighboring rights protection proclamation No. 410/2004 and its amendment No. 872/2014. This law focuses on protecting artistic, literary, or scientific works that fulfill the requirements of originality, fixation and existence of an identifiable author as legal owner of that IP work.

On top of that, the copy right and neighboring rights protection is given for a specified period which is limited to life of the author plus fifty years only. However, the nature of CIP requires perpetual protection due to continuity of generations. This implies the necessity to enact a sui generis CIPs law. Otherwise, the government could not discharge its constitutional responsibilities regarding promotion of cultural rights of the diverse communities of the nation (FDREC, 1995).

An official from the Ethiopian IPO was interviewed on the current IP legal topography and explained that as a Western concept, the purpose of issuing IP-related documents is to ensure legal monopoly of the owner for a limited period. IP rights should be traded and add value to society. Starting from 2001 till date, 41 round discussions have been conducted regarding IP rights and cultural heritages. These discussions were organized by the WIPO. Based on these discussions, an inter-governmental committee mandated to take care of CIPs is established.

The interviewee concluded stating that ‘it is impossible to protect IP rights of the weavers unless they gain total monopoly over the inputs (weaving tools, yarn, and design). However, some attempts are being made to assign legal protection by applying the conventional IP law of copy rights and geographic indications’. Practical examples are ‘Yewello Gabi, and Yejiru Senga’ which get protected under provisions of the trademark and geographic indicators law. However, there is no special law that governs the case of CIPs in Ethiopia.

Moreover, an official in charge of the handcrafts’ development department of the MoCS was asked questions on ‘how the CA happens, measures being taken to curb the problem and the challenges they are facing’. The interviewee begins by classifying the hand-woven cultural clothes as purely cultural, mixed and purely modern. The CIPs issues are more related with the designs of cultural clothes which passed from generation-to-generation as they are. In fact, the act of mixing could also trigger questions on the products’ authenticity and alignment with cultural identity.

Further, the interviewee stated that the cultural designs were appropriated due to fraudulent acts of some greedy merchants who hand over photographs of the designs to foreigners. The imitation is not only conducted abroad but also, there is a rumor that the imitation is being done domestically either in Merkato or in some industry parks. But no one knows the exact place.

4.6. Discussion of the findings

Findings of this study indicated that the Appropriators took the cultural designs and get them replicated with the intention of getting economic benefit at the expense of the Weavers. Weavers came to know about the act only after they sow the IMCCs in the market. There was no consultation, informed consent or compensation. According to Vézina (Citation2019) and Young (Citation2005), this is an immoral and an offensive act that deserves to be condemned by society and punished by law.

The correlation analysis revealed that CA has a statistically significant and negative effect on cultural authenticity and income of Weavers. Which means that, increase in the extent of CA will reduce cultural authenticity of the imitated clothes and the amount of income Weavers could earn from their products. Similary, results of the regression analysis confirmed that CA has a statistically significant effect on authenticity of the IMCCs and Weavers’ income. The researchers’ observation also proved that the IMCCs have different texture, look and feel compared to the AUCCs. According to the aesthetic handicap theory, CA has distorted the cultural meaning, emotional resonance and poetic significance embedded within the hand-woven cultural clothes (Tan, Citation2009). Hence, caused cultural harm to the Ethiopian people in general and to the weaving community in particular (Heyd, Citation2011; Schein, Citation2004).

The diamond theory (Porter, Citation1990) explains how CA affects competitiveness of the cultural garment industry. Eventhough Users know the difference between AUCCs and the IMCCs; Weavers are not able to provide the AUCCs for affordable prices. This is due to shortage of production factors, especially threads. The threads market is already monopolized by few merchants who distribute these inputs via a long value chain that increases their price without adding value. This problem is compounded by the AUCCs demand for the old weaving technology which is too slow compared to the modern power-loomed technologies.

Weavers are forced to stick to this old technology because, the modern ones could not enable them weave cultural fabrics of such light, soft and fine texture. As a result, mass presence of the IMCCs with lower prices, color diversity, ease to care for, durability, wearability and availability shifted the Users’ demand from the AUCCs to the IMCCs and reduced the amount of income weavers could earn from their business (Ogbonnaya & Ogwo, Citation2016; Eze & Bello, Citation2016; Rani, Citation2014).

Considering such harms of CA on the owners of CIPs, international and regional conventions and legal frameworks are already in place. Nonetheless, the Ethiopian IP legal topography does not cover CIPs of the nation. There is no separate national policy, strategy or law that deals with preservation, protection and commercialization of CIPs (Abiyot, Citation2020). This scenario provided favorable ground for the modern textile industries to appropriate the designs, replicate them and flood the market with their imitated products. In fact, there are some recent attempts made by the IP office to extend the general IP law and protect some products, especially based on geographic indicators. Literature has shown that the conventions and legal frameworks on CIPs protection provided nations with two options: either to extend the general IP law or enact sui generis IP laws that specifically deal with the CIPs (Yu, Citation2012; Vézina, Citation2019). Obviously, the general IP law requires fulfillment of materiality or fixation, originality, authorship, reproducibility and authenticity in order to assign IP protection to a certain IP work for which legal protection is sought (Young, Citation2005; Shand, Citation2002). Thus, eventhough the attempts made by the Ethiopian IP office are appreciable, compatible and relayable protection of CIPs demand enactment of sui generis IP laws (Abiyot, Citation2020; Karjala & Paterson, Citation2017).

According to Debeli et al. (Citation2023), the Ethiopian textile sector is given special attention as a potential area for investment and education. On top of that, Yan et al. (Citation2023) emphasized that there is strong cooperation between China and East Africa on higher education. The lessons from Srilanka (Memon et al., Citation2022) revealed that the cultural weaving industry could be sustained by providing legal protection, establishing strong institutions and integrating the traditional art with modern technical and vocational education and training and higher education institutions. The Ethiopian government could use this opportunities and the practice of other countries to provide legal protection as well as capacitate the weaving industry staye competetive in the market.

Moreover, the highest responsibility to ensure competitiveness of cultural industries is placed on the government (Li et al., Citation2023; Eickelpasch et al., Citation2010). Therefore, due to the AUCCs socio-cultural implications, the Ethiopian government has to guard the weaving industry from CA by enacting relevant policies, laws and strategies.

Authors in the area, such as Vézina (Citation2019) and Tan (Citation2009) raise their concerns on the fashion designers’ act of appropriating cultural designs. They said that modifications and imitations of traditional clothing designs will result in distorting the cultural resonance that harmoniously flows between philosophies, beliefs and values of a specific community and the wearing members of that cultural dress. When economically powerful textile companies plagiarize cultural designs, they devoid the design of its original meaning and subject it to sale at the mass market.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

By integrating different theories this study shades light on the cultural appropriation in Ethiopian context and how CA can affect the aesthetic authenticity and income of weaving society. The finding revealed that in Addis Ababa more than 300,000 people are engaged in weaving. It is the source of income to hundreds and thousands. Weaving particularly the designing requires agility. The respondents obtained the weaving knowledge and skill from their own parents and the industry is male dominated. Currently, the cultural clothes weaving become victim of appropriation. CA is practiced without the cultural clothes designers’ consent and without moral and financial compensations. The weavers believe that the act of CA, the violation of the rights of the weaving community, is done not innocently but purposely for money making.

The act of CA is spoiling the honor and pride that weavers have with AUCCs and it is also disturbing the cultural heritage status and religious vitality of the designs. The practice of CA affected the income of weavers, hiked the income of the appropriators and eroding cultural identity and authenticity of the products. An increase in the CA deteriorates the level of the IMMCs and distorts the look and cultural values embedded within the AUCCs.