?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Mapping the roles of various actors involved in handling a pandemic is significant for effective policy integration. It helps clarify each actor’s authority, the coordination level and the interaction patterns formed. This emergence of COVID-19 as a cross-sectoral issue necessitates involvement from numerous actors, given its impact produces trade-offs in the health, social and economic sectors, thereby rendering a balance in its implementation imperative. In the context of the pandemic, swift and appropriate policy integration and collaboration between industries are essential to address its broad and complex impact. This study aims to identify prominent actors in handling the pandemic by employing social network analysis (SNA) supported by the Socio-Technogram Network to map the actor centrality in the network structure for handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City. The findings reveal that policy actors in the health sector had the highest centrality in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City, mainly due to the significant involvement of non-human factors regulated mostly by the Health Agency. Therefore, ensuring stability in the health system is pivotal to successfully handling COVID-19 in Bandung City.

Impact Statement

Every government faces a health crisis due to the trade-off between the health system and the economy to prevent COVID-19 transmission. The cross-sectoral COVID-19 pandemic requires a dynamic, integrated and effective policy response involving diverse central and local government actors. The policy actors involved in overcoming it also establish communication and coordination networks to carry out their duties.

Policymakers in the healthcare sector play the most central role. They have the most extensive network and influence over other policymakers in handling the COVID-19 Pandemic in local-level government, such as in the City of Bandung, West Java, Indonesia. The results of this study are pertinent to policymakers, healthcare professionals, and the general audience. Enhancing comprehension of the interactions of policy players in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic is anticipated to offer assessment and feedback for pertinent stakeholders in managing non-natural disasters in the future.

Introduction

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, health systems are struggling to promptly deploy, manage and employ resources in order to minimize societal damage (Gomes Chaves et al., Citation2023). The healthcare plan for dealing with pandemics adopts a model for responding to outbreaks that occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in larger casualties in excess of those previously anticipated (Coccolini et al., Citation2020; Thapa, Citation2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that even a strong healthcare system is not immune to the complexities of this pandemic (Gomes Chaves et al., Citation2023).

The focus of handling the COVID-19 pandemic is not merely on the health sector but has also penetrated other sectors, such as social and economy, and has shown an impact on the sustainability of sustainable development (Haleem et al., Citation2020; Ristić et al., Citation2020). Interaction among stakeholders, such as the government, the business sector and society, is critical to ensuring long-term economic development through good governance practices (Buchari et al., Citation2024). Primarily, due to the wide-ranging effects of the COVID-19 pandemic beyond healthcare system, neglecting to address these impacts may eventually lead to cascading failures in the social, political and economic sectors (Wernli et al., Citation2021). The phenomenon shows that COVID-19 is a zoonosis, a disease that may be transmitted from animals to people or vice versa, with the potential to significantly disrupt the normal structure of life (Hynes et al., Citation2020). For the purpose of preventing the virus from spreading, the government has put in place a number of social interaction restrictions, which have drastically changed people’s routines on a daily basis (Ristić et al., Citation2020). We can choose to maximize social and environmental factors and meaningful work, and it requires cooperation and protection of more vulnerable groups while implementing social distancing (J. McIntyre-Mills, Citation2020; J. J. McIntyre-Mills, Citation2022).

The speed of virus transmission has encouraged governments in various countries to take appropriate and immediate policies in controlling population mobilization, accompanied by efforts to develop an adequate health system (OECD, Citation2020; Yeo, Citation2020). Despite the fact that handling social, economic and health sectors due to pandemics is fragmented based on the responsibilities of each government agency, it must be conducted in an integrated way and find the right balance because it generates trade-offs when applied (Aminullah et al., Citation2023; Miftah et al., Citation2023b; Suwarno & Rahayu, Citation2021). The complexity of handling the COVID-19 pandemic, which is cross-sectoral and multi-stakeholder, is a challenge requiring a dynamic and effective policy response from the government in dealing with crises to minimize the impact (Han et al., Citation2020; Mei, Citation2020; Su & Han, Citation2020).

To suppress COVID-19 transmission, the Chinese Government, with its centralized authority and supported by a quick response (QR) from the local government, implemented a regional quarantine policy in Wuhan City as the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. They also implemented the use of technology through the QR health code to get community participation and other actors, such as NGOs (Han et al., Citation2020; Mei, Citation2020; Sharifi & Khavarian-Garmsir, Citation2020). Meanwhile, the Vietnamese Government, which was called one of the ‘safest countries’ from COVID-19, intervened by quickly closing the accessibility of areas affected by the pandemic and forming the National Steering Committee for the Prevention and Control of the COVID-19 Outbreak. At the grassroots level, Vietnam formed a kind of Rapid Action Team based on the principle of the ‘four on-spot’ policy or local plans in preparing for disasters that could occur at any time (Hoang et al., Citation2020).

Unlike China and Vietnam, the South Korean government was considered quite successful in controlling COVID-19 transmission without implementing strict regional quarantine measures (Kim, Citation2020; Moon, Citation2020). Collaborations between central and local governments in mobilizing resources, technology, human resources (manpower), health facilities, armed forces support, cooperation development schemes between academics and experts, strengthening the role of the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), and Central Disaster Management Headquarters (CDMH), and the learning process in identifying problems and public trust in the government were important points in controlling the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea (Kim, Citation2020; S. Lee et al., Citation2020; X. Wang et al., Citation2020). Meanwhile, several Western countries, such as France, England, Spain, Italy and the United States, were facing difficulties in handling the COVID-19 pandemic since they had a fairly high rate of positive COVID-19 confirmed cases (Thu et al., Citation2020).

This pandemic attack became a reflection for governments worldwide; that developed countries with high incomes are not necessarily more resilient than developing countries (Freed et al., Citation2020; (Hamiduzzaman et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, socio-cultural elements, such as trust in government, culture, group mentality and shared previous experiences dealing with epidemics are significant (Binte Aamir et al., Citation2022; Chowdhury & Jomo, Citation2020). Social solidarity and collective beliefs drive local wisdom rooted in community culture and become a space for negotiation when confronted with an unexpected crisis, resulting in solutions implemented during COVID-19, for instance, Jogo Tonggo and Pager Mangkok in Indonesia (Harini et al., Citation2022). Similarly, when the government adopts program titles embrace social inclusivity and community-centered approaches, which fostering the sense of social solidarity. Moreover, the government also adopted the name of a program that prioritizes social inclusivity and community-centeredness based on the principles of social solidarity, which goes beyond mere ‘social separation’ or ‘physical distancing’ (Chowdhury & Jomo, Citation2020).

In line with global practices for pandemic handling, Indonesia is also formulating policies to address the COVID-19 pandemic. The Indonesian government has intensively handled the pandemic through central and regional government coordination (Putera et al., Citation2022). An ad hoc team, known as the COVID-19 Task Force, was formed, with each regional head assigned specific responsibilities mandated in Presidential Decree Number 7 of 2020 concerning the COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force. This team implemented strategic policies, allowing each region the flexibility to tailor their approach based on the overarching direction provided by central government policy.

Each regional government must tailor their approach to policy integration in handling a pandemic emergency to align with the unique values and characteristics of their respective region (B. Wang, Citation2021). In Indonesia, the practice of social solidarity serves a way to protect each other and strengthen mitigation programs for families during the COVID-19 pandemic (Harini et al., Citation2022). Local governments are tasked not only with adapting and fulfilling their duties but also with cultivating organizational resilience characterized by ‘immune’ or ‘strong’ characters in crisis management (Duchek, Citation2020). Furthermore, relationships between communities, universities, NGOs and the commercial sector support the community in dealing with the pandemic to the best of each actor’s capacity (J. J. McIntyre-Mills et al., Citation2023; Wirawan et al., Citation2023).

Seen from a more local scale, management policies were also carried out by each district/city government, including in Bandung City. The policy for handling the COVID-19 pandemic was not only carried out by the Bandung City Government but was also delegated to other actors as collaboration and integration forms in handling the COVID-19 pandemic as mandated in the Decree of Mayor Bandung City Number 443 of 2020 concerning the Task Force for the Rapid Response to COVID-19 in Bandung City (Miftah et al., Citation2023a).

In response to this unprecedented challenge, the government is developing integrated policies involving various actors to build resilience and readiness for recovery (Miftah et al., Citation2023b). Within the context of policy integration, mapping out the involved actors and the involved actors is essentials to facilitate planning for integration and collaboration (Tosun & Lang, Citation2017). Analyzing the interactions between actors and their interorganizational networks at different levels of analysis in a global pandemic can provide a holistic picture of how such networks evolve over time (Federo & Bustamante, Citation2022). Additionally, mapping is also quite helpful in clarifying the authority of each policy actor and the interaction pattern carried out. Moreover, it is also another effort to develop responsive crisis management by involving the role of actors at the local level (Djalante et al., Citation2020). Undoubtedly, the private sector plays a pivotal role. Previous study by Miftah et al. (Citation2023b) highlighted that the private and health sectors were the main drivers of economic recovery, with other sectors also contributing to the effort.

Policy integration refers to a policy process examining cross-sectoral issues managed by various fields and enacted by policy actors in a governance system that combines policy objectives and instruments to comprehensively and cohesively address cross-sectoral problems (Biesbroek & Candel, Citation2020; Candel, Citation2019; Candel & Biesbroek, Citation2016; Capano et al., Citation2015; Head, Citation2019; Lo, Citation2018; Mickwitz & Kivimaa, Citation2007; Peters, Citation2014; Tosun & Lang, Citation2017; Trein et al., Citation2021; Waldt, Citation2017). The literature studies indicate that the term policy integration has been widely used in environmental and energy policy issues discussing regulatory instruments and interactions between actors (Candel & Biesbroek, Citation2016; Meijers & Stead, Citation2004; Tosun & Lang, Citation2017). In addition, policy integration extends beyond fostering cooperation aspect among policy actors, but it also addresses issues related to response accuracy. As a process, policy integration can be adopted in every policy cycle. Therefore, apart from explaining the dimensions of the policy frame, subsystem involvement, policy goal and policy instruments (Biesbroek & Candel, Citation2020; Candel, Citation2019; Candel & Biesbroek, Citation2016), it will also explore policy instruments and strategy (Mickwitz & Kivimaa, Citation2007).

Policy integration is required to regulate policies involving the economy, health, social and education sectors in handling the COVID-19 pandemic (Maggetti & Trein, Citation2022). Although it cannot be denied that there are challenges in coordinating and integrating various policies from various fields (Saguin & Howlett, Citation2022), there is a need to examine a different scope to reorient the perspective of existing policies, which aim at providing a better perspective by the practitioners or policy actors that will be integrated into policies (Trein et al., Citation2021). An analysis of each decision-making actor’s capacity is necessary due to the pandemic’s extensive effects (Nanda et al., Citation2023).

Based on the aforementioned explanation, a research question is constructed: How is the centrality of the actors involved in the network structure for handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City? Thus, this study aims to map the actors’ centrality involved in the network structure for handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City. This is to facilitate planning and collaboration in the context of policy integration. Additionally, mapping helps clarify the authority of each policy actor, the coordination efforts undertaken and the formation of interaction patterns. This study might provide new insights into the interconnections and interactions between actors in the local system and how they affect the government’s response to the pandemic.

Materials and method

Data collection sources and techniques

The primary data for this study were obtained from direct interviews with parties deemed relevant to the required data. With current technological advances, interviews were also conducted via teleconference. Additionally, secondary data were obtained from a literature study on several supporting documents that can help map actors’ centrality in handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City. Data related to the actors involved in the COVID-19 Task Force in Bandung City were obtained through the appropriate data in the Decree of the Mayor of Bandung City No. 440 of 2020 concerning the Establishment of a Policy Committee, the COVID-19 Task Force, and Economic Recovery Task Force in Bandung City. For central data regarding the actors involved in the circle of actors handling COVID-19 in Bandung City, data were obtained from interviews with several key informants, such as the Head of Data and Information of the Communication and Information Office (Diskominfo, Dinas Komunikasi dan Informatika). Then, with the Head of Diskominfo of Bandung City, the Head of Research and Development of City Planning, Research and Development Office (Bappelitbang, Badan Perencanaan, Penelitian, dan Pengembangan), and employees with functional positions as researchers at Bappelitbang. More information from several Zoom meetings related to data synchronization with the Diskominfo of West Java Province and the Health Agency of Bandung City was successfully used to identify coordination between actors in handling the pandemic in Bandung City. The following are the interview guidelines:

What is your role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City?

Who are the key actors involved in policies and actions related to COVID-19 in Bandung and in contact with you?

What is the relationship between these actors when making decisions and implementing policies?

Are there differences in social networks based on their sector in response to COVID-19?

How do collaboration and communication between policy actors influence the effectiveness of the COVID-19 response in Bandung City?

This study employs social network analysis (SNA) (Borgatti et al., Citation2013) and Socio-Technogram Networks (Latour, Citation2005; Law & Callon, Citation1998) to describe the relationship network between actors in organizations involved in handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City.

Social network analysis (SNA)

SNA is a method developed in social sciences fields, such as sociology and communication sciences, focusing on patterns of relationships between people and groups such as organizations and governments (Vaughan, Citation2005; Kusuma et al., Citation2021). Studies using the SNA method have been widely employed to describe social networks in organizational or community networks (Borgatti et al., Citation2013).

This method operates by examining the structure of social networks formed between actors in a social environment that are interconnected, either directly or indirectly (Kapucu et al., Citation2017). Edges of the directed type have an arrow symbol at the end and represent an asymmetric relationship, whereas edges of the undirected type have regular lines and depict a symmetric relationship (Borgatti et al., Citation2013). Moreover, this analysis is developed based on assumptions about the importance of the relationship between actors or nodes through network links (edges) (Borgatti et al., Citation2013). Subsequently, the number of edges connected to a particular actor node is called the degree (Scott, Citation2012).

Centrality within a network reflects the significance of different actors to the network structure (Frank, Citation2002). It denotes how crucial a node is in the network and can be identified in three ways: the number of relationships with other nodes (degree), how quickly a node can reach all other nodes in the network (closeness), and how frequently a node is on the shortest path between two other nodes (betweenness) (Kolli & Khajeheian, Citation2020). Centrality in interaction graphs can be measured in a simple way through the degree of the node, which is how many connections the node has (Merrer & Trédan, Citation2009). The method relies on the strength of the relationship between the actors and the accuracy of the reputation of the established social relations information, which increases the reputation of the information provided (J. Y. Lee & Oh, Citation2015). This method relies on the use of depiction/visualization tools to portray the relationship(s) between actors. Centrality calculations in this study utilize degree centrality and closeness. The formula used for calculation is as follows.

Degree Centrality

Description:d(ni) is the number of interactions or relationships that one node has with other nodes in the same network.

Closeness Centrality

Description:N = the total number of nodes in a network.d(ni, nj) = the number of shortest paths connecting nodes ni and nj.

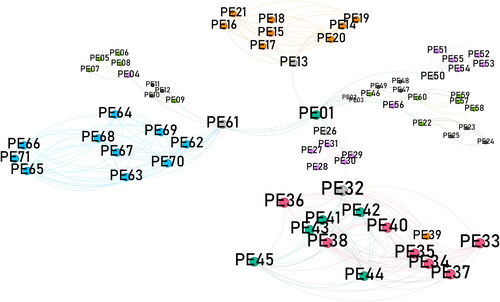

This study seeks to describe the actor centrality in the network structure for handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City, which processed the centrality value and modularity class calculations automatically to generate maps using network mapping software, namely Gephi version 0.101. Gephi is an open-source software for network research and visualization developed by academics at the University of Technology of Compiègne in Compiègne, France. The modularity class that the Gephi program established after analyzing the data determines which clusters appear in the SNA visualization map. In employing this method, there are several approaches to visualize the occurring relationships between actors. It is not merely useful for visualizing relationships but also to determine the central figure or node and the most influential ones in the relationship to be visualized. In this research context, the focus is on visualizing the actors’ centrality in the network structure for handling COVID-19 in Bandung City (Setatama & Tricahyono, Citation2017).

This approach was carried out by calculating several centrality values that had a strong influence on how visualization can be formed. Centrality is a characteristic of a prominent, influential, or powerful node position in the network (Borgatti et al., Citation2013). In addition to centrality calculation, other factors influence data presentation, one of which is choosing a layout algorithm for the data presentation. There are several common layout options that can be used to present policy actor data using Gephi software (Khokhar, Citation2015). The choice of layout depends on how the data retrieval and its appearance characteristics. The amount and method of data presentation are done in an informative manner to select the layout algorithms.

First, the Force Atlas layout algorithm is a spatial layout algorithm used for real-world networks, including web networks, which are small and scale-free world networks. This type of algorithm is force-directed. For better network mapping, the Force Atlas algorithm is optimized for small networks with a focus on quality over speed. Second, the Fruchterman Reingold layout algorithm, also belonging to the force-directed algorithms class in Gephi. It is favored for its ability to present data presentation in a clear and informative manner, contributing to neat and visually appealing network representations.

In this study, nodes in the visualization are labeled with certain codes, and can be found in the Appendices section. The use of codes for enhances the navigability and comprehensibility of the visualizations in Gephi. By assigning codes to nodes and providing corresponding explanations, it becomes straightforward to identify each node without the need for lengthy descriptions. Several previous scholars who also implemented this method, including Koromila et al. (Citation2022), Chen et al. (Citation2022) and Ekasari et al. (Citation2020), have used Gephi to conduct SNA. Koromila et al. (Citation2022) assigned numbers that run from 1 to 45 based on the number of existing nodes. Meanwhile, Chen et al. (Citation2022) used the phrase ‘commodity code’ to refer to the code assigned to nodes, which consists of 10-digit numbers. Then, Ekasari et al. (Citation2020) employed the ‘#’ symbol, followed by a series of numbers from 1 to 27. All three scholars additionally included a table with an explanation for each code used.

Socio-technogram network

Michel Callon, Bruno Latour and John Law introduced the term actor-network in the 1980s, whereby all the entities involved were considered as ‘actors’ (Latour, Citation2005; Law & Callon, Citation1998). This concept focuses on the process of network creation, the actors listed in the network, the parts that make up the network and the development of the network (Gosselin & Journeault, Citation2022). There are several aspects to this concept. First, networks include both human actors and non-human actors, assuming they have equal weight in social analysis (Henttu-Aho et al., Citation2023; Shmargad, Citation2017). Second, connections can be interpreted as how at least two entities influence each other directly or through the intermediary of another entity (Kolli & Khajeheian, Citation2020; Vicsek et al., Citation2016). Third, human and non-human actors are part of and have interests that mutually shape and influence each other in the network (Vicsek et al., Citation2016).

Within the socio-technographic network, factors and interactions between actors have fluctuating relationships among people, objects, ideas and processes (Latour, Citation2005). The connection lines between the research actors were arranged based on how COVID-19 was handled in Bandung City. In selecting actors, the researchers have the authority to include or exclude certain actors in the network according to the interests attached to each actor. The function of the socio-technogram network in this study is to observe the non-human factors strengthening the centrality of human actors produced by the previous SNA analysis. The socio-technographic network in this study was created using existing research data and policies related to responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in Bandung City. These sources contain data on both human and non-human actors. The authors utilized Microsoft Visio to map out the actors. The findings of this mapping may identify and show the relationships between actors in handling the pandemic.

Results and discussion

Based on the obtained data, the actors involved in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City were mapped into two main maps. First, a circle map of actors involved in coordination flows within the COVID-19 Task Force based on the official structure in accordance with the Decree of the Mayor of Bandung City Number: 443/Kep.239-Dinkes/2020 concerning COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force in Bandung City as the initial product of the formation of a COVID-19 handling unit.

Second, a circle map of actors involved under the Decree of the Mayor of Bandung City No. 440 of 2020 concerning the Establishment of a Policy Committee, COVID-19 Task Force and Economic Recovery Task Force in Bandung City that replaced the previous mayor’s decree regarding the COVID-19 Task Force. This regulation is a result of the issuance of Presidential Regulation Number 82 of 2020 concerning the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee (KPC-PEN, Komite Penanganan COVID-19 dan Pemulihan Ekonomi Nasional) which changed the structure and function of COVID-19 Handling.

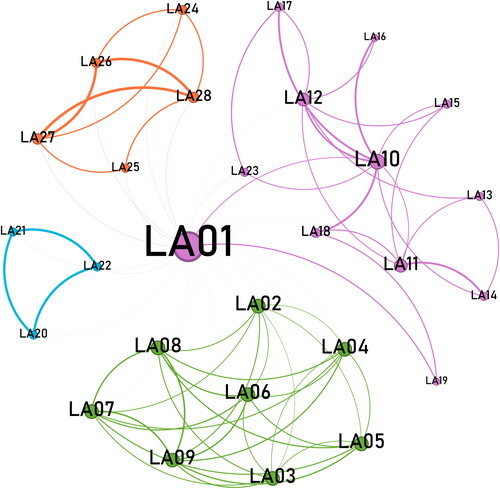

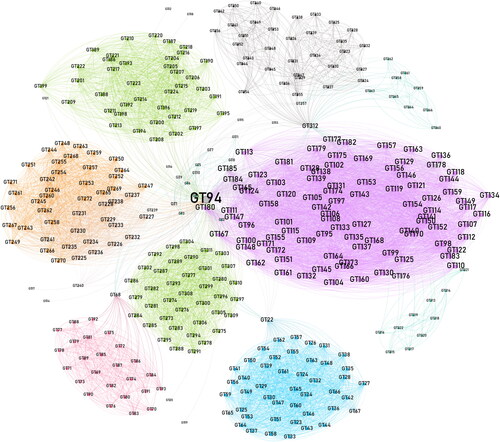

The replacement of the COVID-19 Task Force\at the regional level is a consequence of the enactment of related regulations at the national level. It is imperative to separate the handling of the economic impact of COVID-19 handled by the COVID-19 Task Force from handling COVID-19 in general. Through data processing activities on SNA using Gephi, the results of network visualization of actors involved in accordance with each Mayor’s Decree were obtained. Based on these regulations and interviews, there are 366 policy actors, with several informants coming from the same agency, or 366 nodes in the visualization, which are connected to one another both directly and indirectly, resulting in 8811 edges. In the visualization, only a few nodes that have labels based on filters based on degree range. Following is a visualization of the actor network involved in the COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force in Bandung City.

As per Presidential Regulation Number 82 of 2020 concerning the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee, a new institution within the COVID-19 Task Force handling unit in Bandung City has changed to the Task Force for COVID-19 handling in Bandung. This change occurred due to the separation of handling COVID-19 in general compared to handling the impact of COVID-19 on the economic sector and its recovery. For visualization, the second map of policy actors involved in the Task Force for COVID-19 Handling in Bandung City is presented below:

The visualization result illustrates the actors involved in the organizational structure for handling COVID-19 at the Bandung City level and their role in coordinating with each other to produce a complex network of actors in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic problem in Bandung City. Initially, the organization for handling COVID-19 in Bandung City was originally a Task Force for the Acceleration of handling COVID-19, which in its development turned into a COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force with the issuance of Presidential Decree No. 82 of 2020 concerning the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee, accompanied by the issuance of Decree of the Mayor of Bandung No. 440 of 2020 concerning the Establishment of a Policy Committee, COVID-19 Task Force and the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee in Bandung City. The two visualization results, each representing the organizational structures for handling COVID-19 in Bandung City, were obtained using the degree criteria for each actor involved. These variations were presented using the Fruchterman-Reingold layout through the Gephi data presentation software. In total, there are 292 policy actors or 292 nodes who are linked to each other both directly and indirectly, creating 4619 edges in the above visualization. Particularly, the network map uses closeness centrality.

The aforementioned data revealed that there were seven main actors who played a major role in the network between actors within the organizational structure of the COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force in Bandung City. Among them, the most dominant group of actors was the operational section headed by the Head of Health Agency (Kadinkes/Kepala Dinas Kesehatan) of Bandung City, since the networks of actors seen as the largest due to its four sub-sections as the front line in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City. This dominance can be attributed to the fact that its four sub-sections are part of the front line in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City.

Broadly speaking, the mapping of these two actors looks similar; however, the visualization results shown in the COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force were quite different. Kadinkes of Bandung City was the actor that had the most influence from the other actors involved because of the wider network of functions in the subdivisions that must be coordinated. In addition, Kadinkes directly supervised several sub-sectors with considerable significance. The number of actors under their supervision was greater, which can be seen from the size of the policy actor that appears.

Among the total number of existing nodes, 20 are related to the health industry, with 8 of them being posts in the Bandung City Health Agency. The Head of the Bandung City Health Service, as the most influential node, has 222 vertical and horizontal edges with other nodes. These edges are multi-sectoral in character, connecting diverse nodes, such as the military, police and services in charge of certain domains relating to COVID-19. Aside from that, relationships are formed with various commercial sectors, non-governmental groups and communities (Roosmini et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, the second visualization includes 21 nodes that are directly tied to the health industry. Apart from that, 11 of the nodes are part of the Bandung City Health Service. The difference in coordination between this task force and the previous one is that it includes members of the Indonesian Doctors Association (IDI/Ikatan Dokter Indonesia), which is one of the health professional associations with undirected relationships with parts of the Health Service and military.

With the establishment of the new organizational structure, there were several separations and simplifications of authority in the structure for the COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force in Bandung City. Implicitly, this can make the existing coordination network more effective, as the new structure showed a simpler and clearer flow of coordination.

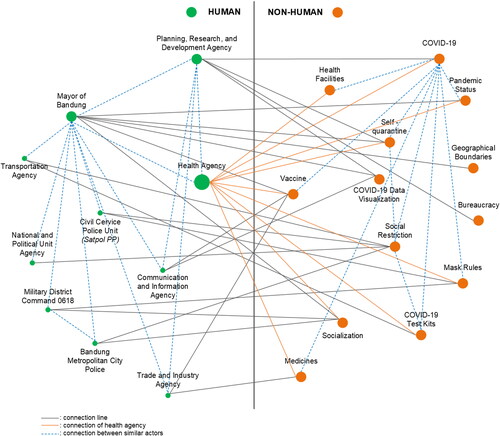

In addition to the organizational structure of the COVID-19 Response Acceleration Task Force in Bandung, the researchers sought to map the real actors’ circles involved in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City. This aims to see how the coordination circle occurred outside of the Task Force activities as previously mapped. Data regarding these actor circles were obtained through a series of interviews with actors involved in handling COVID-19. The visualization of the actor circle results is presented below.

The visualization result above depicts that the involved actors are related to each other through coordination bonds as a form of their role in coordination. This visualization utilized a Force Atlas type layout with degree centrality ranking criteria. The processing results revealed that the Health Agency of Bandung City emerged A the most influential actor in the entire actors’ circle involved. This condition is a consequence of the many coordination networks that have been carried out as the vanguard in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City.

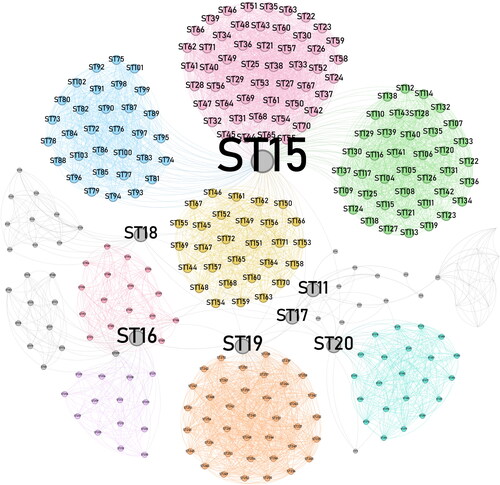

In addition to the collaboration carried out by elements of government and law enforcement, there were also contributions from third parties sectors, especially in the field of economic recovery. This contribution was also mapped and carried out based on the structure of the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee as stated in the Decree of the Mayor of Bandung City Number 440 of 2020 concerning the Establishment of a Policy Committee, COVID-19 Task Force and COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee in Bandung City. It focused on visualizing the collaboration between actors of government elements and third parties/private sector. Following is the policy actor-formed visualization by Gephi.

The above visualization results of the Force Atlas layout with the degree ranking criteria showed that a network had emerged in the coordination structure of the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee actors in Bandung City. In the mapped structure, there was collaboration between local government elements and private elements. It appeared that the Assistant of the Regional Secretariat for Economic Affairs and Development was the actor who had the highest influence in the Bandung City economic recovery policy actor who collaborated with the private sector.

Each party was observed to have networked according to the coordination circle based on each related working group. In each group, government and private elements influenced each other, which was evidenced by the Food Security and Logistics Distribution Working Group coordinated by the Head of City Food and Agriculture Service of Bandung City, with the vice coordinator position held by the Sub-Division Regional Head of State Logistics Agency of Bandung City from the private sector. These two actors coordinated the work groups consisting of government and private parties such as the Head of Distribution and E-Commerce of the Commerce and Industry Office of Bandung City, Food Security Council of Bandung City, the President Director of Dignified Market Regional Company in Bandung (Perusahaan Daerah Pasar Bermartabat Kota Bandung), the Head of HISWANA MIGAS (Oil and Gas Entrepreneurs Association) of Bandung City, Bandung City Urban Farming Forum and academic elements, such as the Head of the Agribusiness Study Program of Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung.

These collaborations aimed at formulating technology-based best policy materials and fostering collaboration in economic recovery with a scheme to strengthen food security and streamline the distribution of community food logistics, and to drive the development of strengthening food security and logistics, with a focus on leveraging local potential. Through this collaborative effort, it was expected that the output of this working group would capture the aspirations of the parties directly affected by economic recovery in the field of food security and logistics distribution.

After visualizing using the SNA tools above, the researchers identified the factors leading to actor centrality. In socio-technogram network theory, all human and non-human elements played a role in maintaining network integrity. All human groups tasked with handling COVID-19 in Bandung City had accompanying non-human artifacts that played a role in determining the role of humans as policymakers in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City. The following is the socio-technographic network for handling COVID-19 in Bandung City:

As depicted in , it was increasingly evident that the Health Agency was the most central actor compared to all the actors involved, as shown in the SNA results that have been carried out previously. In the socio-technogram network, it was illustrated that the factors causing the centrality of the health sector occurred because non-human actors that were vital in handling COVID-19 were mostly handled and acted upon by the Health Agency itself. These non-human factors include the regulation of medicines, vaccines, COVID-19 test kits, self-quarantine, health facilities, pandemic status and social restrictions.

Based on the aforementioned mapping results, it was illustrated that the actors involved in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City interacted and networked closely in carrying out their respective roles. The actors who had the major role would naturally become the central actor in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City. The policy actor and the actor circle showed similar central actors, namely actors in the health sector, namely the Head of Health Agency and the Health Agency of Bandung City, who played a significant role in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City. Even though they were not actors in inter-sectoral coordination, the authority and influence of these actors made them have the highest level of centrality when compared to other actors in the circle or structure of COVID-19 handling in Bandung City.

Conclusions

The findings from the SNA using Gephi software showed that policy actors in the health sector had the highest centrality in handling COVID-19 in Bandung City, both in terms of the organizational structure of the COVID-19 Task Force and the circle of actors handling COVID-19. The main actors in the health sector included the Head of Health Agency of Bandung City, who was seen to play a central role in the structure of the COVID-19 Task Force in Bandung City based on the analysis of closeness centrality. This indicates that despite various fields in the policy for handling COVID-19, the health sector still held high centrality. Additionally, within the actors’ circle handling COVID-19 in Bandung City, the Health Agency, based on degree centrality analysis, still played a central role in handling the pandemic. This is linked to the crucial need for handling a pandemic and is closely related to the success of controlling the spread and handling of the disease. Meanwhile, from the analysis of the Socio-technogram Network, the centrality of the Health Agency occurred because most important non-human factors were managed by the Health Agency. Therefore, as seen from the SNA mapping, the success in handling the pandemic in Bandung City depends on the success of health sector policies.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the inability to benchmark the patterns and structures of COVID-19 management in other regions restricts the ability to make comprehensive comparisons. Additionally, reliance on secondary data sources, such as the structure of the COVID-19 Task Force in Bandung City, may introduce biases or overlook certain aspects of the situation. Future research endeavors should aim to address these limitations by exploring data collection from diverse sources, including social media platforms beyond Twitter and YouTube. Furthermore, there is a need for further exploration of SNA models to enhance the depth and breadth of similar studies in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran; along with all researchers from Quadran Energi Rekayasa, Management and Policy Studies Research Group; and the Bandung City Planning, Research and Development Agency for their valuable contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

Non applicable.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ahmad Zaini Miftah

Ahmad Zaini Miftah SCOPUS ID: 6504016449.

Ahmad Zaini Miftah is affiliated with the Public Administration Department of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran (Unpad). He is also a researcher at the Center for Decentralization and Participatory Development Research (CDPD), Unpad, and the Quadran Energi Rekayasa, AP Research Group in Bandung, Indonesia. His research interests include policy integration, development studies, health policy and data visualization.

Ida Widianingsih

Ida Widianingsih SCOPUS ID: 15924634700

Ida Widianingsih is a professor of international development administration at the Public Administration Department, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Padjadjaran (Unpad), Indonesia and holds a PhD from Flinders Institute of Public Policy and Management, Flinders University, Australia.

She is a senior researcher and executive director of the Center for Decentralization and Participatory Development Research (CDPD) at Unpad. She is also a contract-based consultant and trainer for various institutions, including the World Bank, ADB, AusAID, CIDES, CIRDAP Bangladesh, CSSTC NAM Center and the UNSSC, Turin, Italy. Her research interests relate to public administration and development issues, inclusive development policy and participatory governance.

Entang Adhy Muhtar

Entang Adhy Muhtar SCOPUS ID: 57201469469

Entang Adhy Muhtar is a Professor in Development Administration at the Public Administration Department, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Padjadjaran University (Unpad), Indonesia. He is also a senior lecturer and researcher at the same faculty and holds a doctoral degree from the same department. His main research interest is the Village Development Administration.

Ridwan Sutriadi

Ridwan Sutriadi SCOPUS ID: 57193734442

Ridwan Sutriadi is an urban planner and professor of sustainable smart city at the School of Architecture, Planning, and Policy Development, Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB), and holds a PhD from the University of Florida, USA. His main research interests include urban planning, land use, communicative city, smart city and urban governance.

References

- Aminullah, E., Erman, E., & Soesilo, T. E. B. (2023). Simulation of the COVID-19 handling policy in Indonesia. Journal of Public Health in Africa, 14(5), 1. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2023.2233

- Biesbroek, R., & Candel, J. J. L. (2020). Mechanisms for policy (dis)integration: Explaining food policy and climate change adaptation policy in the Netherlands. Policy Sciences, 53(1), 61–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-019-09354-2

- Binte Aamir, F., Ahmad Zaidi, S. M., Abbas, S., Aamir, S. R., Ahmad Zaidi, S. N., Kanhya Lal, K., & Fatima, S. S. (2022). Non-compliance to social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative cross-sectional study between the developed and developing countries. Journal of Public Health Research, 11(1), jphr.2021.2614. jphr.2021.2614. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2614

- Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2013). Research Design. In J. Seaman (Ed.), Analyzing social networks (pp. 24–44). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Buchari, R. A., Abdillah, A., Widianingsih, I., & Nurasa, H. (2024). Creativity development of tourism villages in Bandung Regency, Indonesia: Co-creating sustainability and urban resilience. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49094-1

- Candel, J. J. L. (2019). The expediency of policy integration. Policy Studies, 42(4), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2019.1634191

- Candel, J. J. L., & Biesbroek, R. (2016). Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sciences, 49(3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9248-y

- Capano, G., Howlett, M., & Ramesh, M. (2015). Bringing governments back in: Governance and governing in comparative policy analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(4), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2015.1031977

- Chen, C. W., Huang, N. T., & Hsiao, H. S. (2022). The construction and application of e-learning curricula evaluation metrics for competency-based teacher professional development. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(14), 8538. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148538

- Chowdhury, A. Z., & Jomo, K. S. (2020). Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries: Lessons from selected countries of the global south. Development (Society for International Development), 63(2–4), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-020-00256-y

- Coccolini, F., Sartelli, M., Kluger, Y., Pikoulis, E., Karamagioli, E., Moore, E. E., Biffl, W. L., Peitzman, A., Hecker, A., Chirica, M., Damaskos, D., Ordonez, C., Vega, F., Fraga, G. P., Chiarugi, M., Di Saverio, S., Kirkpatrick, A. W., Abu-Zidan, F., Mefire, A. C., … Catena, F. (2020). COVID-19 the showdown for mass casualty preparedness and management: The Cassandra Syndrome. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 15(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-020-00304-5

- Djalante, R., Lassa, J., Setiamarga, D., Sudjatma, A., Indrawan, M., Haryanto, B., Mahfud, C., Sinapoy, M. S., Djalante, S., Rafliana, I., Gunawan, L. A., Surtiari, G. A. K., & Warsilah, H. (2020). Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Progress in Disaster Science, 6, 100091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091

- Duchek, S. (2020). Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Business Research, 13(1), 215–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7

- Ekasari, I., Sadono, R., Marsono, D., & Witono, J. R. (2020). Mapping multi stakeholder roles on fire management in conservation areas of Kuningan regency. Jurnal Manajemen Hutan Tropika (Journal of Tropical Forest Management), 26(3), 254–267. https://doi.org/10.7226/jtfm.26.3.254

- Federo, R., & Bustamante, X. (2022). The ties that bind global governance: Using media-reported events to disentangle the global interorganizational network in a global pandemic. Social Networks, 70, 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2022.02.012

- Frank, O. (2002). Using centrality modeling in network surveys. Social Networks, 24(4), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(02)00014-X

- Freed, J. S., Kwon, S. Y., El, H. J., Gottlieb, M., & Roth, R. (2020). Which country is truly developed? COVID-19 has answered the question. Annals of Global Health, 86(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2894

- Gomes Chaves, B., Alami, H., Sonier-Ferguson, B., & Dugas, E. N. (2023). Assessing healthcare capacity crisis preparedness: Development of an evaluation tool by a Canadian health authority. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1231738. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1231738

- Gosselin, M., & Journeault, M. (2022). The implementation of activity-based costing by a local government: An actor-network theory and trial of strength perspective. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 19(1), 18–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-05-2020-0073

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., & Vaishya, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Current Medicine Research and Practice, 10(2), 78–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.03.011

- Hamiduzzaman, M., Siddiquee, N., McLaren, H., & Tareque, M. I. (2022). The COVID-19 risk perceptions, health precautions, and emergency preparedness in older CALD adults in South Australia: A cross-sectional study. Infection, Disease & Health, 27(3), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2022.04.001

- Han, E., Tan, M. M. J., Turk, E., Sridhar, D., Leung, G. M., Shibuya, K., Asgari, N., Oh, J., García-Basteiro, A. L., Hanefeld, J., Cook, A. R., Hsu, L. Y., Teo, Y. Y., Heymann, D., Clark, H., McKee, M., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2020). Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: An analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. Lancet (London, England), 396(10261), 1525–1534. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32007-9

- Harini, Setyasih., Paskarina, Caroline., Rachman, Junita Budi, & Widianingsih, Ida. (2022). Jogo Tonggo and pager mangkok: Synergy of government and public participation in the face of COVID-19. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 24(8), 5. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol24/iss8/5

- Head, B. W. (2019). Forty years of wicked problems literature: Forging closer links to policy studies. Policy and Society, 38(2), 180–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2018.1488797

- Henttu-Aho, T., Järvinen, J. T., & Lassila, E. M. (2023). Constructing the accurate forecast: An actor-network theory approach. Meditari Accountancy Research, 31(7), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-03-2022-1613

- Hoang, V. M., Hoang, H. H., Khuong, Q. L., La, N. Q., & Tran, T. T. H. (2020). Describing the pattern of the COVID-19 epidemic in Vietnam. Global Health Action, 13(1), 1776526. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1776526

- Hynes, W., Trump, B., Love, P., & Linkov, I. (2020). Bouncing forward: A resilience approach to dealing with COVID-19 and future systemic shocks. Environment Systems & Decisions, 40(2), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-020-09776-x

- Kapucu, N., Hu, Q., & Khosa, S. (2017). The state of network research in public administration. Administration & Society, 49(8), 1087–1120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399714555752

- Khokhar, D. (2015). Gephi cookbook: Over 90 hands-on recipes to master the art of network analysis and visualization with Gephi. Packt Publishing.

- Kim, P. S. (2020). South Korea’s fast response to coronavirus disease: Implications on public policy and public management theory. Public Management Review, 23(12), 1736–1747. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1766266

- Kolli, S., & Khajeheian, D. (2020). How actors of social networks affect differently on the others? Addressing the critique of equal importance on actor-network theory by use of social network analysis. In I. Williams (Ed.), Contemporary applications of actor network theory (pp. 211–266). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7066-7

- Koromila, I., Aneziris, O., Nivolianitou, Z., Deligianni, A., & Bellos, E. (2022). Stakeholder analysis for safe LNG handling at ports. Safety Science, 146, 105565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105565

- Kusuma, R. R., Widianingsih, I., Ningrum, S., & Myrna, R. (2021). Five clusters of flood management articles in Scopus from 2000 to 2019 using social network analysis. Science Editing, 8(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.6087/kcse.234

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor network theory. Oxford University Press Inc.

- Law, J., & Callon, M. (1998). Engineering and sociology in a military aircraft project: A network analysis of technological change. Social Problems, 35(3), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/800623

- Lee, J. Y., & Oh, J. C. (2015). A node-centric reputation computation algorithm on online social networks. In P. Kazienko & N. Chawla (Eds.), Applications of social media and social network analysis (pp. 1–22). Springer.

- Lee, S., Hwang, C., & Moon, M. J. (2020). Policy learning and crisis policy-making: Quadruple-loop learning and COVID-19 responses in South Korea. Policy & Society, 39(3), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1785195

- Lo, C. (2018). Between government and governance: Opening the black box of the transformation thesis. International Journal of Public Administration, 41(8), 650–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2017.1295261

- Maggetti, M., & Trein, P. (2022). Policy integration, problem-solving, and the coronavirus disease crisis: Lessons for policy design. Policy and Society, 41(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puab010

- McIntyre-Mills, J. (2020). The COVID-19 era: No longer business as usual. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 37(5), 827–838. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2745

- McIntyre-Mills, J. J. (2022). The importance of relationality: A note on co-determinism, multispecies relationships and implications for COVID-19. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 39(2), 339–353. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2817

- McIntyre-Mills, J. J., Lethole, P., Makaulule, M., Wirawan, R., Widianingsih, I., & Romm, N. (2023). Towards eco-systemic living: Learning with Indigenous leaders in Africa and Indonesia through a community of practice: Implications for climate change and pandemics. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 40(5), 779–786. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2976

- Mei, C. (2020). Policy style, consistency and the effectiveness of the policy mix in China’s fight against COVID-19. Policy & Society, 39(3), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1787627

- Meijers, E., & Stead, D. (2004). Policy integration: What does it mean and how can it be achieved ? A multi-disciplinary review [Paper presentation]. 2004 Berlin Confrerence on the Human Dimensions of Global Environment Change: Greening of Policies - Interlinkages and Policy Integration (pp. 1–15). Freie Universität Berlin.

- Merrer, E. L., & Trédan, G. (2009). Centralities: Capturing the fuzzy notion of importance in social graphs Erwan. Proceedings of the 2nd ACM EuroSys Workshop on Social Network Systems (pp. 33–38). https://doi.org/10.1145/1578002.1578008

- Mickwitz, P., & Kivimaa, P. (2007). Evaluating policy integration: The case of policies for environmentally friendlier technological innovations. Evaluation, 13(1), 68–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389007073682

- Miftah, A. Z., Widianingsih, I., Muhtar, E. A., & Sutriadi, R. (2023a). Mapping netizen perception on COVID-19 pandemic: A preliminary study of policy integration for pandemic response in bandung city. KnE Social Sciences, 2023, 463–473. https://doi.org/10.18502/kss.v8i5.13017

- Miftah, A. Z., Widianingsih, I., Muhtar, E. A., & Sutriadi, R. (2023b). Reviving a city’s economic engine: The COVID-19 pandemic impact and the private sector’s engagement in bandung city. Sustainability, 15(12), 9279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129279

- Moon, M. J. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 with agility, transparency, and participation: Wicked policy problems and new governance challenges. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13214

- Nanda, W. D., Widianingsih, I., & Miftah, A. Z. (2023). The linkage of digital transformation and tourism development policies in Indonesia from 1879–2022: Trends and implications for the future. Sustainability, 15(13), 10201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310201

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). April 28). A systemic resilience approach to dealing with Covid-19 and future shocks: New Approaches to Economic Challenges (NAEC). OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/a-systemic-resilience-approach-to-dealing-with-covid-19-and-future-shocks-36a5bdfb/

- Peters, B. G. (2014). Is governance for everybody? Policy and Society, 33(4), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2014.10.005

- Putera, P. B., Widianingsih, I., Ningrum, S., Suryanto, S., & Rianto, Y. (2022). Overcoming the COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia: A Science, technology, and innovation (STI) policy perspective. Health Policy and Technology, 11(3), 100650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2022.100650

- Ristić, D., Pajvančić-Cizelj, A., & Čikić, J. (2020). Covid-19 in everyday life: Contextualizing the pandemic. Sociologija, 62(4), 524–548. https://doi.org/10.2298/SOC2004524R

- Roosmini, D., Kanisha, T. F., Nastiti, A., Kusumah, S. W., & Salami, I. R. S. (2022). Preliminary studies of bandung city health system resilience (case study: Covid-19 pandemic). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1065(1), 012065. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1065/1/012065

- Saguin, K., & Howlett, M. (2022). Enhancing policy capacity for better policy integration: Achieving the sustainable development goals in a post COVID-19 world. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(18), 11600. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811600

- Scott, J. (2012). What is social network analysis. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781849668187

- Sharifi, A., & Khavarian-Garmsir, A. R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. The Science of the Total Environment, 749, 142391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142391

- Setatama, M. S., & Tricahyono, D. (2017). Implementasi social network analysis dalam Penyebaran country branding “wonderful Indonesia.” Indonesia Journal on Computing (Indo-JC), 2(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.21108/indojc.2017.22.183

- Shmargad, Y. (2017). Network perspectives on privacy and security in the internet of things: From actor-network theory to social network analysis. AAAI Spring Symposium - Technical Report, SS-17-01, (pp. 351–353).

- Su, S. F., & Han, Y. Y. (2020). How Taiwan, a non-WHO member, takes actions in response to COVID-19. Journal of Global Health, 10(1), 010380. https://doi.org/10.7189/JOGH.10.010380

- Suwarno, Y., & Rahayu, N. S. (2021). Ls policy integration real in policy practice? Critical review on how government of Indonesia respond to covid-19 pandemic. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 717(1), 012041. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/717/1/012041

- Thapa, B. B. (2021). Hospital Preparedness and Response Framework during Infection Pandemic, MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.28.21259630

- Thu, T. P. B., Ngoc, P. N. H., Hai, N. M., & Tuan, L. A. (2020). Effect of the social distancing measures on the spread of COVID-19 in 10 highly infected countries. The Science of the Total Environment, 742, 140430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140430

- Tosun, J., & Lang, A. (2017). Policy integration: Mapping the different concepts. Policy Studies, 38(6), 553–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2017.1339239

- Trein, P., Biesbroek, R., Bolognesi, T., Cejudo, G. M., Duffy, R., Hustedt, T., & Meyer, I. (2021). Policy coordination and integration: A research agenda. Public Administration Review, 81(5), 973–977. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13180

- Vaughan, L. (2005). Web hyperlink analysis. In K. Kempf-Leonard (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social measurement (Vol. 1, pp. 949–954). Elsevier.

- Vicsek, L., Király, G., & Kónya, H. (2016). Networks in the social sciences: Comparing actor-network theory and social network analysis. Corvinus Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 7(2), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.14267/CJSSP.2016.02.04

- Waldt, G. V. D. (2017). Theories and research in public administration. African Journal of Public Affairs - Theories for Research in Public Administration, 9(9), 183–202.

- Wang, B. (2021). Political meritocracy and policy integration: How Chinese government combats the COVID-19? Asian Politics & Policy, 13(3), 426–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12595

- Wang, X., Xiao, H., Yan, B., & Xu, J. (2020). New development: Administrative accountability and early responses during public health crises—lessons from Covid-19 in China. Public Money & Management, 41(1), 73–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2020.1819012

- Wernli, D., Tediosi, F., Blanchet, K., Lee, K., Morel, C., Pittet, D., Levrat, N., & Young, O. (2021). A complexity lens on the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 11(11), 2769–2772. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2021.55

- Wirawan, R., McIntyre-Mills, J. J., Riswanda, R., Widianingsih, I., & Gunawan, I. (2023). Pathways to well-being in Tarumajaya, West Java: Post-COVID 19 supporting better access to the commons through engagement and a critical systemic reflection on stories. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2983

- Yeo, L. H. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 pandemic on Asia-Europe relations. Asia Europe Journal, 18(2), 235–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-020-00575-2

Appendices

Figure 1. First map of policy actor visualization results of Task Force for COVID-19 handling in Bandung City.

Figure 2. Second map of policy actor visualization results of Task Force for COVID-19 handling in Bandung City.

Figure 4. Visualization results of the policy actor of the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee in Bandung City.

Appendix 1. First map of policy actor visualization results of Task Force for COVID-19 handling in Bandung City (Figure 1).

Appendix 2. Second map of policy actor visualization results of Task Force for COVID-19 handling in Bandung City (Figure 2).

Appendix 3. Actor circle of COVID-19 handling in Bandung City (Figure 3).

Appendix 4. Visualization results of the policy actor of the COVID-19 Economic Recovery Committee in Bandung City (Figure 4).