Abstract

This study investigated the influence of experiential learning (EL) on entrepreneurial intention (EI) of the students through the lens of perceived behavioural control (PBC). To present a comprehensive perspective, we have explored the direct influence of the antecedents associated with the theory of planned behavior (TPB). The data for were collected via a structured questionnaire from 1,250 final-year management science students. The study employed the partial least squares structural equation modelling method approach for data analysis. The results confirm positive relationships between EL and EI (β = 0.266). In addition, PBC mediates and enhances the relationship between EL and EI (β = 0.30). The result also showed that the TPB antecedents, namely entrepreneurial attitude, subjective norms, and PBC, significantly and positively influence students’ EIs. The proposed model explains a 64% variance in EIs. Moreover, the influence of EL on EI gets stronger when PBC acts as a mediator. Therefore, it is necessary to concentrate on PBC and EL.The study has valuable insights and practical and theoretical implications forhigher education institutions, and policymakers on making more informed resource allocations and fostering an environment conducive to entrepreneurship.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship has been crucial in driving regions’ economic and social development (Cui & Bell, Citation2022). To increase the number of entrepreneurship activities, policymakers have established and implemented entrepreneurial education (EE) programs. These programmes have been designed toimprove experiential learning (EL) and develop the required skills to establish successful businesses. According to Liao et al. (Citation2022), EE is a formal teaching approach designed to instil an entrepreneurial mindset in students. Bandura (Citation1984) defines perceived behavioural control (PBC) as an individual’s belief in their own abilities and skills to undertake a specific task or pursue entrepreneurship. PBC is a significant construct in strengthening the connection between EE and intention (Uddin et al., Citation2022). In addition to PBC, Salamzadeh et al. (Citation2022) found a positive relationship between entrepreneurial knowledge, education, personal attitude, and intention. Previous studies have examined and found that EE, PBC, entrepreneurial attitude (EA) and subjective norms (SN) are the key factors that influence entrepreneurial intention (EI) and performance. Therefore, examining the effects of these important factors and ultimate outcomes may assist policymakers in allocating resources more efficiently and thereby fostering a supportive environment for entrepreneurial activities.

The relationship between EE and EI is a topic of academic debate, predominantly because earlier studies have obtained contradictory findings (Sampeneet al., Citation2022). The majority of previous studies conducted within the context of Western culture demonstrated a significant relationship between EE and EI (Colombelliet al., Citation2022; Demetris et al., Citation2022; Soomro & Shah, Citation2021, Taneja et al., Citation2023a). In contrast, there were several studies found that EE had no or negligible effect on students’ EIs (Kayed et al., Citation2022; Mahendra et al., Citation2017). As a result, outcomes from the existing studies on the impact of EE have yielded inconsistent outcomes, resulting in diverse conclusions. Although EE has the potential to inspire students by equipping them with essential entrepreneurship knowledge, skills, and abilities, it can also discourage them by increasing their awareness of the difficulties inherent in the entrepreneurial process (Ratten & Jones, Citation2020). Bae et al. (Citation2014) highlighted the concern of self-selection bias in the realm of EE. This bias comes from the students who are enrolled in entrepreneurship courses/programs and are having strong EI, and thereby, EE may not significantly affect their choices. In contrast to educating ‘for’ entrepreneurship, it has been noted that EE programs place a greater emphasis on teaching ‘about’ it (Cho & Lee, Citation2018). Learning basically is the process of acquiring or creating new knowledge, and the main objective of any educational program is to enhance learning (Mayer, Citation2011). So for adding depth, EL has been considered for the current study (Gibb, Citation2002). Based on the discussion, the objective of the current study is to investigate the link between EL, PBC, EA, SN, and EIs.

The Ratten and Jones (Citation2020) study revealed that EE significantly impacts EI through the mediating role of PBC. Also, Hoang et al. (Citation2020) emphasized that an individual’s ability to execute a plan of action in various situations is influenced by their PBC. In the context of EI, Nowiński et al. (Citation2017) further highlight the important role of PBC in shaping an individual’s intention to become an entrepreneur. However, it is important to note that EE plays a crucial role in initially influencing PBC. Therefore, it can be concluded that PBC acts as a mediator between EE and EI. However, in previous research, this link has only been studied within the Western context, resulting in limited geographical and cultural coverage. Therefore, the current study aims to address this gap by explicitly investigating the mediation role of PBC in the relationship between EL and EI within the context of Indian entrepreneurship culture. By doing so, the study seeks to provide valuable insights into how these variables are interconnected within the unique cultural and geographical context of Indian entrepreneurship.

Previous studies found that an individual’s EA and SN influence their EI. According to Palalic et al., an individual’s attitude plays a significant role in determining whether or not that person would enter a certain profession or carry out a particular task. In addition, Valencia-Arias et al. (Citation2022) argues that an individual’s attitude is made up of a person’s beliefs, values, and feelings that may not remain constant over time but can still serve as predictors of their actions. The previous studies hasreveledthat attitude and subjective norms play a significant role in determining individual’s intentions (Del Giudice et al., Citation2021; Verplanken & Orbell, Citation2021). The current research aims to investigate the connection between the antecedents of TPB, namely EA, SN, and PBC, on students’ EI. Additionally, it examines the direct and indirect link between EL and EI, considering the mediating role of PBC.

Ajzen (Citation1991) theory of planned behaviour framework suggests that attitude is one of the three antecedents in determining actual behaviour, mediated by intention. Yan et al. (Citation2022) argued that EE could positively affect the EA and SN of students and that students could benefit from the learning experience. In addition, it also states that an individual’s expected behaviour depends on their attitude towards that behaviour. This was previously hypothesised by Dou et al. (Citation2019) that there is a significant relationshipbetween EA and EI. Hence, it is crucial to investigate the direct link between EA and EI among the higher education students. Moreover, PBC has been considered an essential component of becoming an entrepreneur (Wardana et al., Citation2020) and it also is a significant factor in making career decisions (Hoang et al., Citation2020). Previous studies have indicated that the impact of PBC on EI heightened when guided by EE (Nowiński et al., Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2015). According to Wardana et al. (Citation2020), EE develops entrepreneurial ability and enhances self-confidence in engaging in entrepreneurial-related activities. Even though many nations are working towards using the experiential learning technique in entrepreneurship (through business incubation centres/facilities and other means), there currently needs to be more articles that have conducted empirical research on experiential learning. Motta and Galina (Citation2023) report a total of 89 studies on EL in the field of entrepreneurship. As a result, this research aimed to investigate the link between EL, PBC, and EI in less explored countries like India in South Asia (Uddin et al., Citation2022).

The majority of the past studies have paid attention mainly to constructs like EE, PBC, and EI (Pihie & Bagheri, Citation2013; Schultz, Citation2021), and construct entrepreneurial education (EE) was considered in general (Soomro et al., Citation2022; Yeh et al. Citation2021). Nevertheless, the present article emphasises EL over EE, usually by considering Kolb’s ELT.The current study addresses the limitations pointed out by Schultz (Citation2021), which include a small sample size and a low rate of response (22.95%). Moreover, earlier literature has considered EE as a one-dimensional construct while examining its link with EI (Bae et al., Citation2014; Nowiński et al., Citation2017). Hence, in the current research, Kolb’s ELT, known for its multifaceted nature, is employed to examine the context of EE. According to Taneja et al. (Citation2023b), the multidimensional construct of EL has yet to be studied extensively with EL, PBC, and EI. Thus, to provide a more comprehensive understanding, this study takes a more profound perspective by considering EL as a multidimensional construct with multiple dimensions. In this study, EI is a dependent variable, influenced not only by factors such as EL but also by the three antecedents of TPB, namely, attitude, SN and PBC. However, in the context of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education can be examined through EL (Taneja et al., Citation2023b).

Thus, this study integrates Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) with Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to offer a comprehensive perspective on entrepreneurial development.

2. Conceptual framework

Behaviourism, cognitivism, and constructivism are the three important theories in the field of learning (Ferreira, Citation2020). John Watson’s behaviourist theory initially conceptualized learning as the process of observation leading to a lasting transformation in individuals. This theory posits that learning is influenced by the environment in which a person interacts, considering people’s behaviour. However, in the realm of entrepreneurial literature, behaviourism has received relatively less recognition due to its lesser emphasis on experiences, reflection, and its focus on how learning impacts situations (Ferreira, Citation2020). In contrast, in the cognitive framework, learning is seen as a cognitive phenomenon entailing the acquisition and processing of information (Bélanger et al., Citation2022). The widespread adoption of constructivism in the field of entrepreneurship can be attributed to its recognition of the crucial aspects of learning and the significance of self-awareness and reflective capacity among individuals (Cui et al., Citation2019). The concept of learning evolved further and became closely linked to experiential learning. This approach to learning integrates cognitive elements and also emphasizes the importance of reflection (Liao et al., Citation2022).

Although Lewin, Dewey, and Piaget’s model served as the framework for EL, Kolb’s ELT is distinct from these in that it emphasises learning goals, career choices, personal attributes, and social pressure (McCarthy et al., Citation2016). Kolb’s framework (2007, p. 41) has explained that Learning is the outcome of awareness developed via experiences.Moreover, Kolb (Citation2007) proposed that for effective interactive learning and hands-on experience, a student is required to go through the complete cycle to engage in effective interactive learning and learning by doing.The learning cycle consists of four stages: (i) Concrete experience (CE), where students actively engage in tasks or activities to gain new experiences. (ii) Reflective observation (RO) where learners reflect on the tasks and experiences they have engaged in, (iii) Abstract conceptualization (AC) where learners connect their experiences to their existing knowledge and draw conclusions and (iv) Active experimentation (AE), where learners test their conclusions in real-life situations and generate ideas for future actions. By considering the framework of Kolb’s (Citation2007) ELT, the purpose of this study is to examine the direct and indirect effects of EL on EI among students through the mediating influence of PBC. Furthermore, the study also explored the direct impact of antecedents of the TPB, namely, EA, SN and PBC on EI.

Based on Kolb’s framework (2007), it can be deduced that EL in entrepreneurship, coupled with PBC, may significantly influence the EI of students. Considering that actual behaviour is the ultimate outcome, this study investigates the role of education in relation to self-confidence and external factors as mediators. Earlier scholars (Bae et al., Citation2014; Yeh et al., Citation2021) have extensively examined the significant role of education and learning in the context of entrepreneurship. Conversely, Gibb (Citation2002) emphasized that EE must incorporate experiential elements, as education without reflection holds little value (Ferreira, Citation2020). Therefore, this study has adopted Kolb’s ELT framework, considering EL as the primary focus. EL, as highlighted by Dewey (Citation1938), surpasses other forms of education, yet its connection to PBC and EI remains unexplored, thus warranting further investigation in the present paper.

Ajzen’s (Citation1991) TPB model provides a theoretical foundation to explore the impact of EA, SN, and PBC on the EIs. Numerous scholars have utilized this framework in entrepreneurship to examine the actual behaviour of individuals (Uddin et al., Citation2022). The current study used the TPB framework to examine the influence of antecedents namely EA, SN, and PBC, on students’ EI. The TPB provides valuable insights into how individuals’ intentions are translated into actual behaviour (Mir et al., Citation2022). TPB is considered one of the critical theories in psychology, and this expands upon the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1975). While TRA emphasized that attitude is a determinant of intentions, TPB introduces three additional determinants: attitude, SN, and PBC, which collectively shape an individual’s actions. According to Saptono et al. (Citation2021), PBC is a crucial factor because it is a prerequisite for individual behaviour. Based on support from existing literature, EA, SN, and PBC have been included in the present study as determinants of entrepreneurial intention.

3. Literature review and hypothesis

Entrepreneurial education (EE) is defined as ‘any educational programme aimed at developing the mindset and skills necessary for venture creation’ (Fayolle et al., Citation2006, 702). The primary focus of EE is to provide students with entrepreneurial awareness and encourage them to navigate the risks involved in the entrepreneurial process (Paray & Kumar, Citation2020). EE not only cultivates entrepreneurial-related skills, it also enhances the effectiveness of start-ups, but also exerts a positive influence on the management of entrepreneurial activities. (Santos et al., Citation2021). Hence, PBC has been recognized as a crucial variable in investigations related to EE (Elnadi & Gheith, Citation2021).

According to Bandura (Citation1977), PBC refers to an individual’s belief in their ability and skills to perform a task successfully. According to Alferaih (Citation2022), PBC is a relevant concept for entrepreneurship because it is task-oriented and domain-specific, asses the belief that individuals hold, and refers to the process of turning those beliefs into intentions. Like PBC, entrepreneurial PBC is defined as an individual’s self-belief in his/her skills and capabilities to become an entrepreneur (Izquierdo & Buelens, Citation2011). In this study, PBC is considered as entrepreneurial PBC. In their study, Nowiński et al. (Citation2017) found that PBC significantly mediated the relationship between EE and intention. As mentioned earlier, most previous studies have focused on EE, particularly examining its relationship with PBC and entrepreneurial intention (Hockerts, Citation2018; Yeh et al., Citation2021). Ahmed et al. (Citation2020) emphasize that learning is a vital outcome of EE. However, whether it is viable to impart EE within a classroom setting remains unanswered (Jiatong et al., Citation2021). Traditional teaching methods often struggle to adequately equip individuals with the skills and mindset necessary for engaging in entrepreneurial activities. As a dynamic process of transformation, entrepreneurship demands an environment that fosters the development and application of creative ideas. In the realm of entrepreneurship, motivation and skills play a crucial role in navigating uncertain environments, encompassing activities such as risk-taking, resource organization, and implementation (Motta & Galina, Citation2023). Numerous researchers have highlighted the ineffectiveness of traditional approaches in EE for cultivating the necessary skills (Paliwal et al., Citation2022; Seyoum et al., Citation2021). Moreover, Khokhar et al. (Citation2022) and Motta & Galina (Citation2023) propose the development of curricular activities that adopt a practical approach and actively engage students in solving real-world problems. Nabi et al. (Citation2017) suggested that EE should embrace EL, as it influences students’ intentions through the development of PBC. Abd Rahim et al. (Citation2022) also propose that EL can effectively enhance students’ PBC toward entrepreneurship. Anwar & Abdullah (Citation2021) further indicate that EL has been underexplored in relation to PBC, as evident from earlier literature. Given these insights, it becomes crucial to consider EL instead of traditional EE and investigate its impact on PBC and EI.

H1: EL significantly influences PBC.

Anwar and Abdullah (Citation2021) state that EL in entrepreneurial education (EE) is a reliable indicator of students’ intention to participate in entrepreneurial activities. Therefore, consideration must be given to EL instead of EE (Badghish et al., Citation2022).

Approaches to EE have faced criticism for teaching theoretical knowledge ‘about’ entrepreneurship rather than preparing students ‘for’ it (Mukhtar et al., Citation2021). Additionally, EE courses do not focus on EI related problems. Scholars have favoured EL over traditional EE approaches (Otache et al., Citation2019). EL involves the creation of knowledge through transformative experiences (Ferreira, Citation2020). EL is essential in entrepreneurship because most entrepreneurs learn by doing the work themselves (Munoz et al., Citation2015; Taneja et al., Citation2023b). Furthermore, EL allows failure, which is more critical in entrepreneurial activity (Cope, Citation2003). According to Fischer et al. (Citation1993), little is known about how people learn from formative experiences. It has been demonstrated that EL must be understood and implemented in order to improve higher education (Taneja et al., Citation2023b).

Scholars suggest that EI is crucial to entrepreneurship and venture formation (Hockerts, Citation2018). Therefore, neglecting this step will disrupt the entire entrepreneurial process. According to Alammari et al., EI is a commitment and willingness to exert essential effort in the entrepreneurial process. This study hypothesises that EI is the belief among students that they will establish businesses in the future. Literature supports that EI is crucial in determining entrepreneurial behaviour (Rauch & Hulsink, Citation2015).

According to Abd Rahim et al. (Citation2022) and Uddin et al. (Citation2022) students’ EI is influenced by PBC, EE, familial background, entrepreneurial culture, and passion. Several researchers have researched EI in different parts of the world, revealing a significant link between EE and EI (Hoang et al., Citation2020; Otache et al., Citation2019; Taneja et al., Citation2023b). Farrukh et al. (Citation2017) and Jena (Citation2020) have demonstrated that familial background, university culture, EE, and other aspects positively impact EI. These factors are essential if EE supports them because future behaviour is a product of education (Paray & Kumar, Citation2020).

Based on the literature, EE influences university students’ EIs, and the two have a positive connection (Walter & Block, Citation2016). In addition, EE instils in students the self-determination to pursue entrepreneurial careers (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2011). A successful venture can be formed by increasing students’ EI through EE (Zhang et al., Citation2013). Especially, students participated in various entrepreneurial programs likely have entrepreneurial mindsets. Nevertheless, Nabi et al. (Citation2017) reviewed 153 studies and discovered inconsistent results regarding the relationship between EE and intention. Even though the literature on the relationship between EE and intention is available, it is generally rare in South Asia and India in particular. Numerous scholars confirm that EE, directly and indirectly, impacts EI through PBC (Motta & Galina, Citation2023; Nabi et al., Citation2017; Wilson, Citation2008). Nabi et al. (Citation2017) argue that EL may be a more effective method for contributing to the enhancement of self-belief in one’s abilities; thus, evaluating the impact of EL in entrepreneurship on EI and PBC may be useful. Based on this, the authors have organised this paper in such a way that it investigates the effect of EE, in general, and EL, in specific, on students’ EIs. Thereby, the findings of this research lend support to the study conducted by Motta and Galina (Citation2023), which suggests that learning about entrepreneurship must be experiential rather than traditional, i.e. restricted to the classroom.

H2: EL significantly influences EI.

Perceived behavioural control (PBC) has been recognized as a significant factor influencing EI (Elnadi & Gheith, Citation2021). According to Boyd and Vozikis and Krueger (Citation1993), PBC is essential for EIs. The two most widely used EI models, the TPB proposed by Ajzen and the entrepreneurial event model proposed by Shapero and Krueger, considered PBC a significant factor in EI (Uddin et al., Citation2022). Thus, scholars such as Chen et al. (Citation1998); Krueger et al. (Citation2021) have validated this relationship. Several previous investigations (Maresch et al., Citation2016) have examined the relationship between PBA and EI in the context of EE. For instance, the research conducted by Puni et al. (Citation2018) revealed the relationships between EE, PBC, and EI in Ghana, and the results demonstrated a significant direct relationship between EE and EI and an indirect relationship through the mediation of PBC. Similarly, Ciptono et al. (Citation2022) examined the impact of entrepreneurial training and PBC on the EI of prisoners and found a significant relationship between the two. Furthermore, Uddin et al. (Citation2022) investigated the moderating effect of PBC in Bangladesh and found a significant relationship between EE and EI moderated by PBC. This study investigates the direct influence of EL on EI and the indirect impact of EL on EI through the mediation effect of PBC, thereby adding new insights to previous research. The following hypotheses are developed based on the discussion.

H3: PBC significantly influences EI.

H4: EL significantly influences EI through the mediation of PBC.

Ajzen’s (Citation1991) TPB indeed emphasizes that an individual’s intention and subsequent actions to perform a specific task that are influenced by one’s own attitude. The positive attitude towards a particular behaviour leads to a higher intention to engage in that behaviour. Attitude has been found to play a significant role in determining EI in entrepreneurship (Dou et al., Citation2019). By recognizing the significance of attitude, EA has been identified as a critical construct influencing students’ EIs.

H5: EA significantly influences EI.

Subjective norms (SN) encompass the social factor that shapes an individual’s perceived social pressure to either undertake or refrain from a specific behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). In entrepreneurship, SN represent an individual’s perception of how his/her decision to become an entrepreneur is viewed by significant others, such as family and friends (Kautonen et al., Citation2015; Liñán & Chen, Citation2009). The previous studies on entrepreneurial intentions have shown mixed results regarding the SN dimension of TPB, with some studies reporting inconsistent results (Lortie & Castogiovanni, Citation2015; Munir et al., Citation2019). However, research has shown that the opinions of individuals in close relationships are significant factors for university students (Agu, Citation2021; Romero-Colmenares & Reyes-Rodríguez, Citation2022; Tiwari et al., Citation2017; Yasir et al., Citation2021). In certain studies, SN has been identified as the most influential dimension of TPB. Therefore, it is important to consider these cultural and contextual factors when examining the role of SN in understanding the relationship to EI.

H6: SN significantly influences EI.

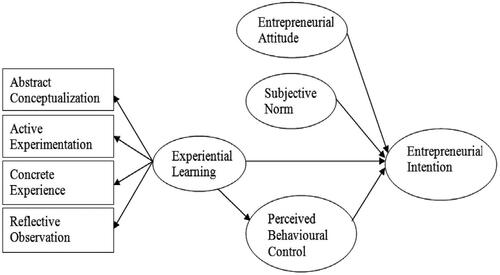

Based on the study’s objectives and the proposed hypotheses, the conceptual framework is depicted in .

4. Methodology

4.1. Data collection and sample

This study employs a quantitative and hypothesis-deductive approach to investigate the correlation between variables. To select the sample for the current study, authors followed Krueger’s (Citation1993) suggestion that to measure entrepreneurial intentions (EIs) accurately, the sample should be selected from the population of those who are currently facing major career decisions (Krueger, Citation1993). Final-year management science students were targeted based on the assumption that they would be more likely to start a business (Chaudhary, Citation2017) and, because they were in their last years of college, it was assumed that they would have a fairly clear vision of their plans for the future and imminent career decisions (Krueger, Citation2000).

Male students participated at a higher rate than female students, as illustrated in . The female percentage is roughly 42% and is not particularly low. We attempted to gather information both from public and private institutions, but the students from the private institutions showed greater enthusiasm and willingness to complete the questionnaire, thereby reflecting a larger proportion.

Table 1. Demography.

We narrowed the field of higher educational institutes using the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) approved by the government of India and the Ministry of Education. Students in the top 100 ranked higher educational institutes of India were the subjects of a primary data collection technique. The institutions taken into consideration provided EL and had either an entrepreneurial development cell or a business incubation facility. Students at these institutions were the subjects of data collection using the simple random sampling technique. The simple random sampling technique was used to ensure that every sample had an equal probability of being chosen, frequently used in entrepreneurship research (De Jorge-Moreno et al., Citation2012; Karimi et al., Citation2013; Krueger, Citation2000; Liñánet al., Citation2011). A structured questionnaire was used for collecting the data. A questionnaire was distributed during class, and the students were given 30 minutes to complete it. Consent was obtained verbally, and students were informed that participation in the survey was purely on a volunteer basis, and they were also assured that their response would be used only for academic purposes and kept confidential. The students were given a small gift for completion of the questionnaire. Ethics approval was obtained on 04 June 2021 from the Kasturba Medical College and Kasturba Hospital Institutional Ethical Committee (Registration number, IEC 235/2021). Verbal consent has been obtained for participation in the study. Participants were provided with a clear explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. A total of 1300 questionnaires were returned, representing a response rate of 83.33 per cent. When the questionnaires were subsequently screened for missing data and outliers (Hair et al., Citation2021), 1250 useful questionnaires were obtained.

4.2. Measures

This study used a survey questionnaire as the research instrument. All the items used to measure the constructs were adopted from previous studies. The entrepreneurial intention and attitude were measured using a 9-item and 3-item scale developed and adapted from Liñán and Chen’s (Citation2009). This study considered experiential learning as a multi-dimensional construct containing four sub-sections (abstract conceptualization, active experimentation, concrete experience, and reflective observation) and was measured using a 29-item scale adapted from Kolb (Citation1976, Citation2007) and Honey and Mumford (Citation1982). Perceived behavioural control was measured using a 6-item scale developed and adapted from Dohse and Walter (Citation2010); Liñán and Chen (Citation2009), and do Paço et al. (Citation2011). Subjective norms were measured using a 5-item scale adapted from Leong (Citation2008); and Liñán and Chen (Citation2009). Each item was evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

4.3 Data analysis

The data were statistically analysed using structural equation modelling (SEM) through partial least squares (PLS) (Hair et al., Citation2021). Previous studies on entrepreneurship have widely used PLS-SEM (Ali et al., Citation2019), which is seen as a suitable analytical technique in several disciplines (Manley et al., Citation2020). This study conducted a two-step approach, including measurement and structural models. In the measurement model, the latent variables’ reliability and validity were established, whereas the hypothetical relationships were checked in the structural model.

5. Results

5.1 Measurement model

Initially, multicollinearity was assessed through variance inflation factor (VIF) calculations to mitigate potential biases in path coefficient estimations. The results presented in indicate that VIF values for all constructs were below 3.3, suggesting the absence of collinearity between predictor variables in the model (Hair et al., Citation2021).

Table 2. Results of reliability and validity test using CFA.

To evaluate the individual reliabilities of items, standardized factor loadings (SFL) were employed. According to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), an SFL equal to or exceeding 0.707 is considered acceptable for an item, while an SFL of 0.50 or higher is generally acceptable in the early stages of research (Hair et al., Citation2021). In , the SFLs range from 0.72 to 0.93 and are statistically significant at the 1% level in two-tailed test analyses, indicating strong statistical significance. Consequently, all multi-item constructs demonstrate good individual reliability at the item level.

We evaluated reliability at the construct level by analysing construct reliability. Hair et al. recommend a value of 0.70 or above as a minimum threshold value for reliability. show that the values of Cronbach’s alpha (α) range between 0.70 and 0.89, and the composite reliability (CR) values range between 0.78 and 0.92, indicating suitable convergence. Furthermore, convergent validity was assessed by analysing average variance extracted (AVE) values. An AVE value equal to or greater than 0.50 is acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). All multi-item constructs have an acceptable range of AVE values exceeding 0.50, as shown in .

Discriminant validity indicates the extent to which one construct truly differs from another construct (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). According to Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), if the square root of the AVE estimate for each construct is greater than the correlation between that construct and all other constructs in the model, then discriminant validity is demonstrated. shows that the squares of the AVEs on the diagonal are significantly greater than the correlation values below the diagonal (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). This means that the indicators have more in common with the target construct than with the other constructs in the measurement model (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981) and that the model has been found to have sufficient discriminant validity.

Table 3. Results of Fornel Larcker criteria.

5.2. Common method bais (CMB)

Common method bias (CMB) needs to be assessed when both independent and dependent variables are assessed using the same survey instrument. CMB was assessed using Harman’s single factor analysis (Lee et al., Citation2014). The result of this test shows that a single factor explains 27.3% of the total variance. As this value is significantly less than 50%, it is safe to assume that there does not exist any one dominant factor in the data set. Hence, it is proved that CMB issue does not exist with the collected samples.

5.3. Structural model analysis

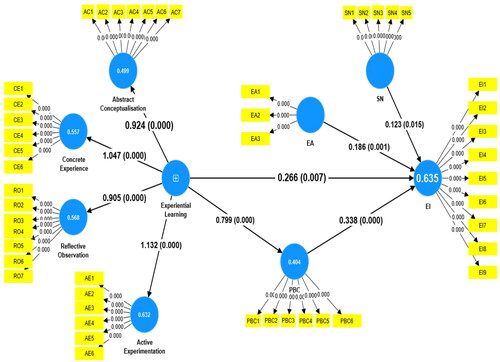

The structural model evaluation was conducted to assess the suitability of a proposed model for predicting EI (). The assessment was done using the R-squared value, and the results showed that the model explained 63.5% of the variance in EI. () shows the results of the hypotheses testing. The results show that EL (β = 0.266, p < .01), PBC (β = 0.338, p < .001), EA (β = 0.187, p < .001), and SN (β = 0.128, p < .05) have a significant influence on EI. Hence hypotheses H2, H3, H5, and H6 are supported. Furthermore, the result also shows that EL (β = 0.799, p < .001) significantly influences PBC. Hence hypothesis H1 is supported.

Table 4. Hypothesis testing results.

The results confirm that both hypotheses H1 and H2 are supported; it is clear that a significant relationship exists between EL and EI with the mediation effect of PBA. However, given the empirical support for H2, comparing the direct and indirect influences of EL on EI becomes essential. The study’s findings reveal that the direct influence of EL on EI has a β-value of 0.266, while the indirect influence through the mediation of PBC is 0.30. These results suggest that EL directly impacts EI; however, the relationship between EL and EI is significantly enhanced when mediated by PBC. Hence hypothesis H4 is supported.

6. Discussion

Although the existing literature was available on the relationship between EE and EI, there is still a need for an in-depth investigation of the relationship between EL, EA, SN, PBC and EI in South Asian countries (Hassan et al., Citation2020; Qudsia Yousaf et al., Citation2022; Yan et al., Citation2022). This is crucial because entrepreneurship development manifests differently across the world (Nayak et al., Citation2023; Uddin et al., Citation2022). This paper contributes to the existing literature using Kolb’s (Citation2007) Experiential Learning Theory framework to examine the connection between EL and EI. Another contribution of this study is exploring the indirect relationship between EL and EI, mediated by PBC. Furthermore, the study investigates the influence of antecedents of TPB, namely EA, SN, and PBC, on EI. Additionally, the study enriches existing theories by developing the proposed model () by integrating Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory with Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour. This integration of theories provides a valuable contribution to expanding their applicability and relevance within the context of entrepreneurship study.

The current study reveals a significant positive link between students’ EL and EI. This emphasizes that engaging in EL develops the students’ self-belief, enabling them to overcome difficulties and fostering the confidence required to pursue entrepreneurial activities (Naktiyok et al., Citation2009). These findings are consistent with the previous studies by Uddin et al. (Citation2022) and Ahmed et al. (Citation2020). Moreover, this study reveals that EL directly impacts EI, which differs from the findings of Nowiński et al. (Citation2017). Nowiński et al. (Citation2017) found no direct link between EL and EI, but they found that there is an indirect link through PBC.

According to Ajzen (Citation1991), PBC is an essential factor influencing an individual’s behaviour. Similarly, PBC is a crucial determinant of individuals’ intentions and behaviour. The results displayed in indicate that the direct effect of EL on EI (β = 0.26) is smaller compared to the indirect effect (β = 0.30). Based on these findings, it can be concluded that PBC mediates the relationship between EL and EI and directly influences students’ EIs.

Another important finding of this study is to identify the significance of cultivating an entrepreneurial attitude in shaping students’ entrepreneurial intention; the study’s findings suggest a positive connection between entrepreneurial attitude and entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.187). In contrast to the study conducted by Dou et al. (Citation2019), which examined the mediating effect of entrepreneurial attitude on the relationship between entrepreneurial attitudes and intention, the current research examined the direct influence of entrepreneurial attitude on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted in diverse cultural and contextual settings, suggesting that the relationship between EA and EI is likely to hold true across various populations (Al-Mamary et al., Citation2020; Maheshwari, Citation2021). Bandura (Citation1977) argues that an individual’s attitude plays a key role in forming the individual’s actual behaviours. The study results suggest that students have a desire to become their own bosses in the future and are more self-reliant. Promoting a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship may be an effective strategy for encouraging more students to consider entrepreneurship, which could have significant economic and social implications in the long run.

The study found that subjective norm (SN) (β = 0.128) was the determinant of EI among students in India, which contrasts with previous research conducted in individualistic societies (Bazkiaei et al., Citation2021; Boutaky & Sahib Eddine, Citation2022). These earlier studies have shown that SN is a weak predictor of EI. However, the study suggests that in collectivistic cultures like India, students may be more susceptible to external influences, such as peer pressure, societal expectations, and guidance from relatives and teachers, when it comes to pursuing entrepreneurship (Shrivastava & Acharya, Citation2020). This is because Indian culture significantly emphasises family, friends, and society in shaping an individual’s beliefs and behaviours (Marmat, Citation2021).

This study contributes to the findings of Nowiński et al. (Citation2017) by demonstrating a positive relationship between experiential learning (EL) and perceived behavioural control (PBC). The entrepreneurial intention has become more accepted in the research on entrepreneurship. In contrast to previous research that primarily focused on entrepreneurial education (Bae et al., Citation2014; Rauch & Hulsink, Citation2015), the present study considered the EL through the lens of Kolb’s model. Therefore, the study contributes to the literature on entrepreneurship by investigating the four dimensions of EL (abstract conceptualization, active experimentation, concrete experience, and reflective observation) and empirically validating the impact of EL on EI, mediated by PBC. Additionally, the results of this study support previous research (Dou et al., Citation2019; Liñán & Chen, Citation2009) by demonstrating a significant relationship between EA and EI. Therefore, experiential learning (EL) is needed right now, and entrepreneurial education needs to focus on EL.

This study integrates Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory with Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour; this integration of theories provides a valuable contribution to expanding their applicability and relevance within the context of entrepreneurship study. The results of the study by Hamid and Mohamad (Citation2020) showed that EL has a positive effect on the intention to be an entrepreneur; the authors also pointed out the theoretical implications that Azjen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour and Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory could be helpful for the development of entrepreneurship. The results of this study could help create an environment that encourages students to learn, and the government can take the lead by setting up start-up incubators, research facilities, and laboratories to support EL in higher education institutions.

7. Practical implications

Numerous scholars specializing in entrepreneurship have extensively studied and advocated for the significant role of EE in improving an individual’s PBC (McGee et al., Citation2009; Yeh et al., Citation2021). This article specifically focuses on the crucial aspects of EL on students’ EI. It explores how this influence operates both directly and indirectly, mediated by PBC. The study’s findings can be utilized to determine the relative importance of different dimensions within this context. McGee et al. (Citation2009) emphasize the significance of customizing policies considering the multi-dimensional and sequential nature of entrepreneurship. The present study offers valuable insights and suggestions for formulating policies related to entrepreneurship and its ecosystem. To enhance awareness and interest at a national level, the Indian government can play a pivotal role in promoting EL by establishing a supportive framework for fostering an EL culture. As part of this endeavour, the government has taken a proactive step by introducing the Atal Innovation Mission (AIM), a flagship program aimed at fostering entrepreneurship through the provision of world-class incubation facilities to start-ups.

Secondly, the study emphasizes the importance of the pre-university stage in shaping students’ objectives, as it significantly influences their future endeavours suggesting that they should have exposure to fundamental entrepreneurial principles before entering the higher education institutions. In line with this recommendation, the Atal Innovation Mission aims to establish tinkering labs at the middle and secondary school level, providing students from classes 6th to 12th with real problem-solving experiences. Such initiatives play a crucial role in promoting EL in entrepreneurship and contribute to the development of cognitive and creative skills among students. Ultimately, these efforts can help alleviate the pressure of creating employment opportunities on the public sector employment for educated youth by promoting self-employment and fostering entrepreneurial endeavours.

Third, it suggests that to increase EI among students, higher education institutions must design entrepreneurship courses and develop EL programs. These courses should include research and practical training, such as students-driven clubs, business competition, business proposals, webinars, seminars, corporate consultancy and networking events. These activities would facilitate students’ interest in developing entrepreneurial engagement. The development of EI among higher education students pursuing may relieve pressure on the industrial enterprises and the government to create employment opportunities for educated youths while simultaneously encouraging them to select self-employment or entrepreneurship as a viable career path.

The study’s findings revealed that the link between EL and EI was strengthened by the mediating role of PBC. This suggests that when formulating entrepreneurial policies, academicians should also consider the importance of fostering PBC alongside with EL. Moreover, the study indicates that EA might have a more significant influence on EI. Hence, public policymakers should design EE frameworks that effectively shape students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship, fostering a positive mindset and encouraging and promoting entrepreneurial aspirations among students.

8. Theoretical implication

Numerous studies have examined the impact of EE on students’ intentions to start their own ventures or engage in start-up activities (Badri & Hachicha, Citation2019). However, there is a limited research on the role of EE in shaping the intentions of students in private institutes within South Asian Pacific nations, as highlighted by Uddin et al. (Citation2022). This study aims to investigate the relationship between EL, PBC, EA, SN and EI while contributing to the renowned theories such as Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) (Kolb, Citation2007) and Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991). Among these theories, Kolb’s ELT framework is widely accepted by scholars due to its student-centric nature (Fewster-Thuente & Tamzin Batteson, Citation2018), making it a suitable approach for this study (Fewster-Thuente &Tamzin Batteson, 2018). By linking ELT with PBC and EI, this paper offers a holistic perspective within the Kolb framework. Additionally, the study incorporates PBC to explore its role in the context of entrepreneurship and EL. The findings suggest that, similar to the TPB framework, self-efficacy acts as a significant mediator between EE and EI.

In Ajzen’s TPB, attitude is a crucial factor influencing intention formation. Building upon the TPB framework, the present article explores the role of EA and SN in shaping the EI of higher education students. The findings of this study align with those of Jena (Citation2020), indicating that EA positively influences students’ EI. Consequently, future research can be conducted to examine the combined influence of EA and other variables, such as EL. Additionally, it would be interesting to explore the significance of all the constructs by integrating the approaches of Ajzen (Citation1991) and Kolb (Citation2007). This integrated approach will provide valuable insights into understanding the complex dynamics between attitude, SN, EL, and EI.

Furthermore, the study advances EL and EI related literature by providing insights into the role of EL in developing EI among students in the context of higher education institutions (HEIs). This study contributes to EL in the context of emerging economies. Even though prior studies have been conducted on the subject they are more related in the context of developed nations, leaving room for more studies in the context of emerging nations such as India (Singh & Mehdi, Citation2022). Evidence obtained in the context of an emerging economy may not have implications for HEIs in the developed countries. However, it addresses the scarcity of findings in developing economy countries.

Findings here significantly contribute to the literature on entrepreneurship and theories such as Kolb’s ELT and Ajzen’s TPB. This study contributes to the current literature on EL and EI by revealing the interaction of variables of TPB. In addition to adding to the current literature, this study examines the mediating effect of PBC on EI. Findings further testify to the importance of EA, SN and PBC in enhancing EIs.

9. Limitations and future direction

The current research acknowledges certain limitations associated with the sample data and the survey method employed. Furthermore, it is important to note that the data gathering process was limited to Online/Offline mode. Future studies should aim to expand the other geographical scope for a more comprehensive understanding. Furthermore, it is important to consider additional factors such as family support, the presence of role models, and entrepreneurial success when examining the aforementioned relationships. Lastly, it would be valuable to analyze global entrepreneurial policies and learn from the experiences of developed countries in addressing challenges related to entrepreneurship. By considering these factors, future research can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics and implications of entrepreneurship in different contexts.

Although this study aims to contribute new insights into EI, it has some limitations that offer promising opportunities for further research. Researchers can further investigate the relationship between EL and PBC by including variables such as gender, cultural impact, and business performance. It is worth noting that the manner in which items are framed within each sub-construct may have influenced respondents’ answers, potentially introducing an acquiescence bias. To address this, future studies can modify questionnaires to reflect necessary adjustments and mitigate such biases. Moreover, to bridge the information gap, a comparative research study encompassing developed and developing countries can be conducted, focusing on the subject. This comparative approach can offer valuable insights into the similarities and differences in entrepreneurial dynamics across different socio-economic contexts.

Author contributions

Conceptionand design: Madhukara Nayak, Pushparaj M Nayak, Harish Joshi.

Analysisand interpretation of the data: Madhukara Nayak, Pushparaj M Nayak.

Draftingof the paper: Madhukara Nayak, Pushparaj M Nayak, Harish Joshi.

Revisingit critically for intellectual content: Madhukara Nayak, Pushparaj M Nayak.

Finalapproval of the version to be published: Madhukara Nayak, Pushparaj M Nayak, Harish Joshi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pushparaj M. Nayak

Pushparaj M. Nayak is working as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Commerce, Manipal Academy of Higher Education Manipal, Karnataka, India. He is pursuing a PhD in Entrepreneurship Education at Manipal cademy of Higher Education, India. His research interest is in entrepreneurship education and innovation. Email: [email protected]

Madhukara Nayak

Madhukara Nayak is working as an Assistant Professor (SG.) in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Shri Madhwa Vadiraja Institute of Technology and Management, Udupi, Karnataka, India. He is the institutional coordinator of the entrepreneurship development cell. His research interests are women’s entrepreneurship, innovation and technology, and knowledge management. Email ID: [email protected]

Harisha G. Joshi

Harisha G. Joshi is working as a Professor at Department of Commerce, Manipal Academy of Higher Education Manipal, Karnataka, India. He is a coordinator of the center for social entrepreneurship, Manipal University. His research interest is in entrepreneurship and innovation. Email ID: [email protected]

References

- Abd Rahim, N., Mohamed, Z., Tasir, Z., & Shariff, S. A. (2022). Impact of experiential learning and case study immersion on the development of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and opportunity recognition among engineering students. Higher Education Pedagogies, 7(1), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2022.2109500

- Agu, A. G. (2021). A survey of business and science students’ intentions to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. Small Enterprise Research, 28(2), 206–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2021.1919914

- Ahmed, I., Islam, T., & Usman, A. (2020). Predicting entrepreneurial intentions through self-efficacy, family support, and regret. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-07-2019-0093

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1975). A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychological Bulletin, 82(2), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076477

- Al-Mamary, Y. H. S., Abdulrab, M., Alwaheeb, M. A., & Alshammari, N. G. M. (2020). Factors impacting entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Saudi Arabia: testing an integrated model of TPB and EO. Education + Training, 62(7/8), 779–803. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-04-2020-0096

- Alferaih, A. (2022). Starting a new business? Assessing university students’ intentions towards digital entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(2), 100087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2022.100087

- Ali, I., Ali, M., & Badghish, S. (2019). Symmetric and asymmetric modeling of entrepreneurial ecosystem in developing entrepreneurial intentions among female university students in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(4), 435–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-02-2019-0039

- Anwar, G., & Abdullah, N. N. (2021, March 12). Inspiring future entrepreneurs: The effect of experiential learning on the entrepreneurial intention at higher education. Social Science Research Network. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3824693.

- Badghish, S., Ali, I., Ali, M., Yaqub, M. Z., & Dhir, A. (2022). How socio-cultural transition helps to improve entrepreneurial intentions among women? Journal of Intellectual Capital, 24(4), 900–928. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-06-2021-0158

- Badri, R., & Hachicha, N. (2019). Entrepreneurship education and its impact on students’ intention to start up: A sample case study of students from two Tunisian universities. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(2), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.02.004

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta-analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12095

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Bandura, A. (1984). Recycling misconceptions of perceived self-efficacy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 8(3), 231–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01172995

- Bazkiaei, H. A., Khan, N. U., Irshad, A. R., & Ahmed, A. (2021). Pathways toward entrepreneurial intention among Malaysian universities’ students. Business Process Management Journal, 27(4), 1009–1032. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-01-2021-0021

- Bélanger, F., Maier, J., & Maier, M. (2022). A longitudinal study on improving employee information protective knowledge and behaviors. Computers & Security, 116, 102641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2022.102641

- Boutaky, S., & Sahib Eddine, A. (2022). Determinants of entrepreneurial intention among scientific students: A social cognitive theory perspective. Industry and Higher Education, 37(2), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/09504222221120750

- Chaudhary, R. (2017). Demographic factors, personality and entrepreneurial inclination. Education + Training, 59(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-02-2016-0024

- Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-9026(97)00029-3

- Cho, Y. H., & Lee, J.-H. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education and performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-05-2018-0028

- Ciptono, W. S., Anggadwita, G., & Indarti, N. (2022). Examining prison entrepreneurship programs, self-efficacy and entrepreneurial resilience as drivers for prisoners’ entrepreneurial intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 29(2), 408–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2022-0550

- Colombelli, A., Loccisano, S., Panelli, A., Pennisi, O. A. M., & Serraino, F. (2022). Entrepreneurship education: The effects of challenge-based learning on the entrepreneurial mindset of university students. Administrative Sciences, 12(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12010010

- Cope, J. (2003). Entrepreneurial learning and critical reflection. Management Learning, 34(4), 429–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507603039067

- Cui, J., & Bell, R. (2022). Behavioural entrepreneurial mindset: How entrepreneurial education activity impacts entrepreneurial intention and behaviour. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100639

- Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.04.001

- De Jorge-Moreno, J., Laborda Castillo, L., & Sanz Triguero, M. (2012). The effect of business and economics education programs on students’ entrepreneurial intention. European Journal of Training and Development, 36(4), 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591211220339

- Del Giudice, M., Scuotto, V., Papa, A., Tarba, S. Y., Bresciani, S., & Warkentin, M. (2021). A self-tuning model for smart manufacturing SMEs: Effects on digital innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(1), 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12560

- Demetris, V., Thrassou, A., Efthymiou, L., Uzunboylu, N., Weber, Y., Riad, M., & Tsoukatos, E. (2022). Editorial introduction: Business under crisis – Avenues for innovation, entrepreneurship and sustainability. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-76583-5_1

- Dewey, J. (1938). The determination of ultimate values or aims through antecedent or a priori speculation or through pragmatic or empirical inquiry. Teachers College Record, 39(10), 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146813803901038

- do Paço, A. M. F., Ferreira, J. M., Raposo, M., Rodrigues, R. G., & Dinis, A. (2011). Behaviours and entrepreneurial intention: Empirical findings about secondary students. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-010-0071-9

- Dohse, D., & Walter, S. G. (2010). The role of entrepreneurship education and regional context in forming entrepreneurial intentions. www.econstor.eu. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/59753.

- Dou, X., Zhu, X., Zhang, J. Q., & Wang, J. (2019). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education in China: A customer experience management perspective. Journal of Business Research, 103, 338–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.058

- Elnadi, M., & Gheith, M. H. (2021). Entrepreneurial ecosystem, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in higher education: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100458

- Farrukh, M., Khan, A. A., Shahid Khan, M., Ravan Ramzani, S., & Soladoye, B. S. A. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions: The role of family factors, personality traits and self-efficacy. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 13(4), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1108/WJEMSD-03-2017-0018

- Fayolle, A., Gailly, B., & Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: A new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30(9), 701–720. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590610715022

- Ferreira, C. C. (2020). Experiential learning theory and hybrid entrepreneurship: Factors influencing the transition to full-time entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(8), 1845–1863. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2019-0668

- Fewster-Thuente, L., & Tamzin Batteson, J. (2018). Kolb’s experiential learning theory as a theoretical underpinning for interprofessional education. Association of Schools Advancing Health Professions, 47(1), 3–8.

- Fischer, E. M., Reuber, A. R., & Dyke, L. S. (1993). A theoretical overview and extension of research on sex, gender, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90017-y

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and changing behavior. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203838020

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gibb, A. (2002). In pursuit of a new ‘enterprise’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ paradigm for learning: creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge. International Journal of Management Reviews, 4(3), 233–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2370.00086

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. In Classroom Companion: Business. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

- Hamid, A. H. A., & Mohamad, M. R. (2020). Validating theory of planned behavior with formative affective attitude to understand tourist revisit intention. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, 4(2), 594–598.

- Hassan, A., Saleem, I., Anwar, I., & Hussain, S. A. (2020). Entrepreneurial intention of Indian university students: The role of opportunity recognition and entrepreneurship education. Education + Training, 62(7/8), 843–861. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-02-2020-0033

- Hoang, G., Le, T. T. T., Tran, A. K. T., & Du, T. (2020). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning orientation. Education + Training, 63(1), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2020-0142

- Hockerts, K. (2018). The effect of experiential social entrepreneurship education on intention formation in students. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1498377

- Honey, P., & Mumford, A. (1982). Learning Styles Questionnaire. Organization Design and Development, Incorporated. ISBN-13: 978-1-902899-27-5.

- Izquierdo, E., & Buelens, M. (2011). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions: The influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 13(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2011.040417

- Jena, R. K. (2020). Measuring the impact of business management Student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106275

- Jiatong, W., Murad, M., Bajun, F., Tufail, M. S., Mirza, F., & Rafiq, M. (2021). Impact of entrepreneurial education, Mindset, and creativity on entrepreneurial intention: Mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 724440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724440

- Karimi, S., Biemans, H. J. A., Lans, T., Chizari, M., Mulder, M., & Mahdei, K. N. (2013). Understanding role Models and Gender Influences on Entrepreneurial Intentions Among College Students. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.09.179

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12056

- Kayed, H., Al-Madadha, A., & Abualbasal, A. (2022). The effect of entrepreneurial education and culture on entrepreneurial intention. Organizacija, 55(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2022-0002

- Khokhar, M., Zia, S., Islam, T., Sharma, A., Iqbal, W., & Irshad, M. (2022). Going green supply chain management during COVID-19, assessing the best supplier selection criteria: A Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Approach. Problemy Ekorozwoju, 17(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.35784/pe.2022.1.04

- Kolb, D. A. (1976). Management and the learning process. California Management Review, 18(3), 21–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/41164649

- Kolb, D. A. (2007). The Kolb learning style inventory. Hay Resources Direct.

- Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879301800101

- Krueger, N. F. (2000). The cognitive infrastructure of opportunity emergence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(3), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870002400301

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2021). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Lee, V.-H., Ooi, K.-B., Chong, A. Y.-L., & Seow, C. (2014). Creating technological innovation via green supply chain management: An empirical analysis. Expert Systems with Applications, 41(16), 6983–6994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2014.05.022

- Leong, C. K. (2008). Entrepreneurial intention: An empirical study among open university Malaysia Students [Dissertation]. Open University Malaysia Center for Graduate Studies.

- Liao, Y., Nguyen, V. H. A., Chi, H., & Nguyen, H. H. (2022). Unraveling the direct and indirect effects of entrepreneurial education and mindset on entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of entrepreneurial passion. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 41(3), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22151

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y.-W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Liñán, F., Urbano, D., & Guerrero, M. (2011). Regional variations in entrepreneurial cognitions: Start-up intentions of university students in Spain. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(3-4), 187–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620903233929

- Lortie, J., & Castogiovanni, G. (2015). The theory of planned behavior in entrepreneurship research: What we know and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 935–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0358-3

- Mahendra, A. M., Djatmika, E. T., & Hermawan, A. (2017). The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention mediated by motivation and attitude among management students, State University of Malang, Indonesia. International Education Studies, 10(9), 61. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v10n9p61

- Maheshwari, G. (2021). Factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions the most for university students in Vietnam: educational support, personality traits or TPB components? Education + Training, 63(7/8), 1138–1153. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-02-2021-0074

- Manley, S. C., Hair, J. F., Williams, R. I., & McDowell, W. C. (2020). Essential new PLS-SEM analysis methods for your entrepreneurship analytical toolbox. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(4), 1805–1825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00687-6

- Maresch, D., Harms, R., Kailer, N., & Wimmer-Wurm, B. (2016). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 104, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.11.006

- Marmat, G. (2021). Predicting intention of business students to behave ethically in the Indian context: From the perspective of Theory of Planned Behaviour. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 12(3), 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-05-2021-0090

- Mayer, R. E. (2011). Does styles research have useful implications for educational practice? Learning and Individual Differences, 21(3), 319–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.016

- McCarthy, S. T., Barnes, A., Giovanetti, K. L., Briggs, F. N., Ludwig, P. M., Robinson, K., & Swayne, N. (2016 Undergraduate social entrepreneurship education and communication design [Paper presentation]. https://doi.org/10.1145/2987592.2987625

- McGee, J. E., Peterson, M., Mueller, S. L., & Sequeira, J. M. (2009). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Refining the measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(4), 965–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00304.x

- Mir, A. A., Hassan, S., & Khan, S. J. (2022). Understanding digital entrepreneurial intentions: A capital theory perspective. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(12), 6165–6191. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-05-2021-0687

- Motta, V. F., & Galina, S. V. R. (2023). Experiential learning in entrepreneurship education: A systematic literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 121, 103919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103919

- Mukhtar, S., Wardana, L. W., Wibowo, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2021). Does entrepreneurship education and culture promote students’ entrepreneurial intention? The mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1918849. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.1918849

- Munir, H., Jianfeng, C., & Ramzan, S. (2019). Personality traits and theory of planned behavior comparison of entrepreneurial intentions between an emerging economy and a developing country. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(3), 554–580. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-05-2018-0336

- Munoz, L., Miller, R., & Poole, S. M. (2015). Professional student organizations and experiential learning activities: What drives student intentions to participate? Journal of Education for Business, 91(1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1110553

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research Agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026

- Naktiyok, A., Nur Karabey, C., & Caglar Gulluce, A. (2009). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The Turkish case. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 6(4), 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0123-6

- Nayak, P. M., Joshi, H. G., Nayak, M., & Gil, M. T. (2023). The moderating effect of entrepreneurial motivation on the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and behaviour: An extension of the theory of planned behaviour on emerging economy. F1000Research, 12, 1585–1585. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.140675.1

- Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Otache, I., Umar, K., Audu, Y., & Onalo, U. (2019). The effects of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Education + Training, 63(7/8), 967–991. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2019-0005

- Paliwal, M., Rajak, B. K., Kumar, V., & Singh, S. (2022). Assessing the role of creativity and motivation to measure entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(5), 854–874. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-05-2021-0178

- Paray, Z. A., & Kumar, S. (2020). Does entrepreneurship education influence entrepreneurial intention among students in HEI’s? Journal of International Education in Business, 13(1), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIEB-02-2019-0009

- Pihie, Z. A. L., & Bagheri, A. (2013). Self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: The mediation effect of self-regulation. Vocations and Learning, 6(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-013-9101-9

- Puni, A., Anlesinya, A., & Korsorku, P. D. A. (2018). Entrepreneurial education, self-efficacy and intentions in Sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 9(4), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-09-2017-0211

- Qudsia Yousaf, H., Munawar, S., Ahmed, M., & Rehman, S. (2022). The effect of entrepreneurial education on entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of culture. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100712

- Ratten, V., & Jones, P. (2020). Covid-19 and entrepreneurship education: Implications for advancing research and practice. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100432

- Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship education where the intention to act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293

- Romero-Colmenares, L. M., & Reyes-Rodríguez, J. F. (2022). Sustainable entrepreneurial intentions: Exploration of a model based on the theory of planned behaviour among university students in north-east Colombia. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100627

- Salamzadeh, Y., Sangosanya, T. A., Salamzadeh, A., & Braga, V. (2022). Entrepreneurial universities and social capital: The moderating role of entrepreneurial intention in the Malaysian context. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(1), 100609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100609

- Sampene, A. K., Li, C., Khan, A., Agyeman, F. O., & Opoku, R. K. (2022). Yes! I want to be an entrepreneur: A study on university students’ entrepreneurship intentions through the theory of planned behavior. Current Psychology, 42(25), 21578–21596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03161-4

- Santos, S. C., Nikou, S., Brännback, M., & Liguori, E. W. (2021). Are social and traditional entrepreneurial intentions really that different? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(7), 1891–1911. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-01-2021-0072

- Saptono, A., Wibowo, A., Widyastuti, U., Narmaditya, B. S., & Yanto, H. (2021). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy among elementary students: The role of entrepreneurship education. Heliyon, 7(9), e07995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07995

- Schultz, C. (2021). Does Technology Scouting Impact Spin-Out Generation? An Action Research Study in the Context of an Entrepreneurial University, 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61477-5_7

- Seyoum, B., Chinta, R., & Mujtaba, B. G. (2021). Social support as a driver of social entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating roles of entrepreneurial education and proximity to the US small business administration. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(3), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-08-2020-0306

- Shrivastava, U., & Acharya, S. R. (2020). Entrepreneurship education intention and entrepreneurial intention amongst disadvantaged students: An empirical study. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 15(3), 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-04-2020-0072

- Singh, L. B., & Mehdi, S. A. (2022). Entrepreneurial orientation & entrepreneurial intention: Role of openness to experience as a moderator. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100691

- Soomro, B. A., Abdelwahed, N. A. A., & Shah, N. (2022). Entrepreneurship barriers faced by Pakistani female students in relation to their entrepreneurial inclinations and entrepreneurial success. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 15(3), 569–590. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-12-2021-0188

- Soomro, B. A., & Shah, N. (2021). Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, need for achievement and entrepreneurial intention among commerce students in Pakistan. Education + Training, 64(1), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2021-0023

- Taneja, M., Kiran, R., & Bose, S. C. (2023a). Assessing entrepreneurial intentions through experiential learning, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial attitude. Studies in Higher Education, 49(1), 98–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2223219

- Taneja, M., Kiran, R., & Bose, S. C. (2023b). Understanding the relevance of experiential learning for entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A gender-wise perspective. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(1), 100760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100760

- Tiwari, P., Bhat, A. K., & Tikoria, J. (2017). The role of emotional intelligence and self-efficacy on social entrepreneurial attitudes and social entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2017.1371628

- Uddin, M., Chowdhury, R. A., Hoque, N., Ahmad, A., Mamun, A., & Uddin, M. N. (2022). Developing entrepreneurial intentions among business graduates of higher educational institutions through entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial passion: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100647

- Valencia-Arias, A., Rodríguez-Correa, P. A., Cárdenas-Ruiz, J. A., Gómez-Molina, S., Valencia-Arias, A., Rodríguez-Correa, P. A., Cárdenas-Ruiz, J. A., & Gómez-Molina, S. (2022). Factores que influyen en la intención emprendedora de estudiantes de psicología de la modalidad virtual. Retos, 12(23), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.17163/ret.n23.2022.01

- Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2021). Attitudes, habits, and behavior change. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(1), 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-011744

- Walter, S. G., & Block, J. H. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.10.003

- Wang, J.-H., Chang, C.-C., Yao, S.-N., & Liang, C. (2015). The contribution of self-efficacy to the relationship between personality traits and entrepreneurial intention. Higher Education, 72(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9946-y