Abstract

Students from different cultures and first languages act differently in developing argumentative essays. This study aimed to compare the rhetorical models followed by the Iranian and Chinese EFL university students in writing argumentative essays. The research aimed to investigate the effect of first language on the use of rhetorical patterns in two different cultural settings. Hyland’s model was used in order to compare students‘ writing. Hyland’s model for interactional-source subtypes includes: hedges, boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, self-mentions. The required data were collected from 80 EFL learners in Iran and China. Mann–Whitney U test was run to clarify the differences in using the metadiscourse markers. The results indicated there were significant differences between Iranian and Chinese EFL students in the use of all, but one, of the mentioned metadiscourse markers. The findings can provide a better perspective toward culture-specific variations in writing skill.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Kaplan’s (Citation1966) proposal concerning the differences between writing mindset of the students from different cultures was a turning point in the study of writing in a second language. To this end, he coined the term “contrastive rhetoric”. This article falls within this framework and contrasts five paragraph essays written in English by learners from Iran and China to see how their different cultures and first languages might affect their writing in terms of a number of features such as how they express doubt (hedges) and certainty (boosters) in their academic writing. It was found that the participants from the two different cultures did, in fact, write differently. Part of the differences was attributable to the effect of their first language and culture. The findings of this study can be helpful in diagnosing the reasons for the inappropriate features in academic writings and providing drills to improve language learners’ academic writings.

1. Introduction

The study of rhetorical pattern in written discourse is an important part of researches in the field of writing. From 1966, when Kaplan (Citation1966) talked about contrastive rhetoric for the first time, till today, a great number of publications in the field of contrastive rhetoric can be found (e.g. Connor, Citation1996; Kaplan, Citation1966; Ying, Citation2000). Moreover, there are many studies done in this field to define and compare the characteristics of texts written by people from different cultures to describe the effect of these characteristics on EFL and ESL (e.g. Khodabandeh, Jafarigohar, Soleimani, & Hemmati, Citation2013; Liu, Citation2007; Rashidi & Dastkhezr, Citation2009).

There are many developments in contrastive rhetoric in the past 30 years and many studies are done in this field; meanwhile, the issue of contrast still deserves more scrutiny. To date, the literature has offered valuable findings which support the fact that students with different cultural backgrounds and different first languages are different in using rhetorical strategies in their writing (e.g. Connor, Citation1996; Grabe & Kaplan 1989; Kaplan, Citation1966). There are numerous researches through which the writings of Iranian or Chinese students have been contrasted with those of the English native speakers (e.g. Biria & Yakhabi, Citation2013; Faghih & Rahimpour, Citation2009; Khodabandeh et al., Citation2013; Liu, Citation2007; Noorin & Biria, 2010; Sabzevari & Sadeghi, Citation2013). However, none of these studies focused on finding out the rhetorical differences between Iranian and Chinese students’ writing, having learned English in two different EFL contexts in Asia with different cultural backgrounds. Therefore, the major purpose of this study was to explore whether there were any statistically significant differences among the types of interactional metadiscourse resources employed by Iranian and Chinese EFL students in their argumentative essay writings in English. To this end, the current study contrasted the use of metadiscourse-markers as determined in Hyland’s 2004 model, in terms of interactional resources, by the Iranian and Chinese EFL university students’ argumentative essays.

2. Literature review

Rhetoric is “the capacity to persuade others; or a practical realization of this ability; or an attempt at persuasion, successful or not“ (Wardy, Citation1996, p. 1). In other words, rhetoric is “the art of persuasion; it concerns arguments on matters about which there can be no formal proof“ (Hyland, Citation2005). We can say that rhetoric is ”the art which search for the capture in opportune moments that which is appropriate and attempts to recommend that which is possible” (Lucaites, Condit, & Caudill, Citation1999). ”Communication and rhetoric are related in small and large ways, communication has had a bit part in rhetoric as communicatio, a technique whereby the rheto figuratively deliberates with the audience” (Sloane, Citation2001).

Contrastive rhetoric (CR) treats the features of each community as motivated by their unique linguistic and cultural traditions that cannot be generalized as superior over others (Canagarajah, Citation2002). Kaplan (Citation1966) first claimed that the reasoning of a text written by an English speaker is different from those written by other language speakers (e.g. an Arab speaker or a Chinese). Zamel (Citation1997) strongly believed that students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds give educators insight. That is to say, the students’ backgrounds make educators sensitive to their struggles with language and writing. This leads to a deterministic stance and deficit orientation as to what students can accomplish in English and what their writing instruction should be. In this way, CR helps to “create and maintain an atmosphere of tolerance for differences in L2 writing” (Leki, Citation1997: 244).

According to Colombo (Citation2012), when students “discover” that their rhetorical choices are not just individual mistakes or errors, but can be related to culturally based preferences, they can validate their own rhetoric. This prevents students from feeling that they are lacking something when producing texts in their second language. Colombo emphasized that CR findings can facilitate students’ access to language norms by drawing their attention to certain text features and structure.

In addition, the textual-linguistic descriptions offered by CR could also improve second-language writing instruction in two regards. First, teachers could use the empirical findings that CR provided to “anticipate some of the challenges” (Canagarajah, Citation2002, p. 42; cited in Colombo, Citation2012). Second, CR findings can facilitate students’ access to language norms by drawing their attention to certain text features and structure (Colombo, Citation2012).

The basic assumption that convinces researchers to do various kinds of studies and compare the discourse of students of different social groups is that there are some differences between the groups of students with different first languages and cultures. Meanwhile, it is important to identify the main causes of differences between EFLer’s writing. Yang (Citation2003) identified three main causes of different organizational patterns in ESL texts: linguistic, cultural, and educational.

Brief as it is, Yang (Citation2003) explained the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relativity as a basic source of linguistic differences. Some researchers such as Ying (Citation2000) and Connor (Citation2012) and many other researchers, such as Leki (Citation1997), claimed that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relatively is the basis of principles of contrastive rhetoric. Both Ying and Connor expressed the view that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis of linguistic relatively is the basis of contrastive rhetoric because it suggests a great relation between languages, thoughts, and cultures. Sapir-Whorf hypothesis refers to a strong relationship between languages and the society or, in other words, cultural boundaries, which is exactly the main idea of rhetoric.

The next important cause of differences is cultural and logical characteristics of EFLers. The cultural background of the writer influences his/her writing strongly. Among the Western rhetorical values, the importance of “originality and individuality” and “self-expression and logical argument” in writing is emphasized (Matalene, Citation1985, p. 790). However, as Chen (Citation2007) argued, under the influence of Confucian traditions, Chinese teachers have always superiority. They have deep knowledge and they are superior to students, as an authority and expert. Teachers transfer their knowledge to students, and students follow them. Chen (Citation2007) continued: as in an apprenticeship, Chinese students may feel that they do not know enough to express their ideas or do something original; consequently, they usually quote past masters and authorities. Hence, when Chinese students come to write in English, argumentative discourse might be problematic for them to construct their own ideas in order to persuade readers.

Gu (Citation2008) explained that rhetoric is intertwined with and attached to philosophy, religion, ethics, psychology, politics, and social relations. He claimed that the heritage of Western rhetoric owes a great deal to the doctrines of Aristotle and Cicero. However, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism strongly affected the heritage of Chinese rhetoric. Gu (Citation2008) tried to convince the readers of his article that Chinese rhetoric, due to its unique culture, is like a puzzle for western readers.

Gu (Citation2008) continues that “Chinese students and scholars feel equally alien to the Western rhetorical tradition when they are challenged to speak in class in a Western institution of higher learning. Some of them even find such a practice frustrating, especially when they are first exposed to the Western culture and the clash between Western and Chinese rhetorical traditions are most apparent.” This claim is proved by Chinese students themselves in their diaries and expressions. For example, the personal experience of Fan Shen (Citation1989) which is quoted in many articles (McClanahan & Davis, Citation2005; Saito, Citation2009; Yang, Citation2003) as an evidence of the effect of culture on L2 writing. is

The third cause of differences between EFLers’ writing, according to Yang (Citation2003), is education. Yang (Citation2003) argued that the focus of teachers and educational settings in China is on grammatical structure and at the sentence level; however, in western countries, the focus is on the organization at the discourse level.

Mohan and Lo (Citation1985) suggested that developmental factors may be relevant to organizational problems in academic writing by second language learners. In order to support this claim, they compared the composition practices in Hong Kong and British Columbia. They found out that Chinese school experience with English composition was oriented more toward accuracy at the sentence level than toward the development of appropriate discourse organization. Mohan and Lo (Citation1985) realized that students also see their writing problems as sentence-level problems.

Metadiscourse, which is also called metatext or metalanguage in many researches (e.g. Bunton, Citation1999; Farrokhi & Ashrafi, Citation2009; Mauranen, Citation1993; Rahman, Citation2004), is “self-reflective linguistic expressions referring to the evolving text, to the writer, and to the imagined readers of that text. According to Sultan (Citation2011), the term ‘metadiscourse’ was first coined by Zellig S. Harris in 1959. Harris tried to describe text elements which comment on the main information of a text, but which themselves contain only unessential information (Sultan, Citation2011). It is based on a view of writing as a social engagement and, in academic contexts, reveals the ways writers project themselves into their discourse to signal their attitudes and commitments” (Hyland, Citation2004).

Because metadiscourse analysis involves taking a functional approach to texts, writers in this area have tended to look to the Systemic Functional theory of language for insights and theoretical support (Hyland, Citation2005). According to Halliday, there are three main language functions (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2014). These three functions are considered as the underlying issue of metadiscourse. Halliday believed that when people produce a message, their speech involved three different kinds of meaning; which is ideational, interpersonal, and textual. For Halliday, language communication is the product or the result of the process of interplay between the ideational, interpersonal, and textual functions of language. Through this interplay, the meaning potential of language is realized. Then, Learning a language entails “learning to mean” (Kumaravadivelu, Citation2006).

Halliday, unlike metadiscourse theorists, believed that textual, interpersonal and propositional (ideational) elements of the texts are not discrete and separable. Writers should simultaneously create propositional content, interpersonal engagement, and the flow of text as they write a discourse. However, the creation of a text is a means of creating both interpersonal and ideational meanings, and textual features cannot be considered as ends. We have to recognize that it is an interaction in a text if metadiscourse is the way writers engage their readers and create convincing and coherent text. It expresses the interpersonal dimension and how both interactional and textual resources are used to produce and continue relations with readers (Hyland, Citation2005, p. 27).

There are different frameworks and classifications of metadiscourse presented by different scholars. A brief overview of the most famous ones is presented in the following.

Williams (Citation1981) classified the written metadiscourse into three types:

hedges and emphatics;

sequencers and topicalizers;

Narrators and attributors.

Beauvais (Citation1986) summarized Williams’ three broad categories of metadiscourse with their examples. The first category which includes hedges and emphatics express the certainty with which a writer presents the material. Hedges are words such as “possibly,“ “apparently,“ “might,“ etc. Emphatics include terms like ”it is obvious that,” ”of course,” and ”invariably”.

The second category includes sequencers and topicalizers. Sequencers and topicalizers denote words that lead a reader through a text. This class includes causal connecting words like “therefore,“ and connectors such as “however“, and illustration markers like “for example“. Temporal sequencers like “next“ and “after,“ and numerical sequencers like “in the first place,” ”second,” and ”my third point is.” Topicalizers focus on a particular phrase as the main topic, paragraph, or the whole section. For example, ”in regard to,” ”in the matter of,” and ”turning now to”.

Narrators and attributors as the third category of Williams’ model tell a reader the resources of ideas, facts, or opinions. The examples of narrators include “I was concerned,“ “I have concluded,“ and ”I think”. Attributors use third person subjects, for examples, ”high divorce rates have been observed to occur in parts of the Northeast that have been determined to have especially low population densities”.

Crismore (Citation1983) presented a new model in which he used a typology of the metadiscourse system based on Williams’ and Meyer’s classifications. His typology includes two general categories, the informational and attitudinal, with subtypes for each.

Informational metadiscourse, based on Crismore (Citation1983), implies that an author can explicitly or implicitly give several types of information about the primary discourse to readers. The informative discourse can be in the form of preliminary or review statements. The author can also give information about the relationship of ideas in the primary discourse–the connective signals–on a global or local level. Crismore (Citation1983) used four subtypes of informative metadiscourse:

Global goal statements (both preliminary and review) which is called goals,

Global preliminary statements about content and structure, which is called pre-plans,

Global review statements about content and structure, which is called post plans, and

Local shifts of a topic which is called topicalizers.

Attitudinal metadiscourse, according to Crismore (Citation1983), refers to this point that an author can also explicitly or implicitly signal his attitude toward the content or structure of the preliminary discourse and toward the reader in order to give directives to readers about the importance or salience of certain points, about the degree of certainty he has, about how he feels, and about the distance he wishes to put between himself and the reader. Crismore (Citation1983) used four subtypes of attitudinal metadiscourse:

Importance of idea, which is called saliency,

Degree of certainty of assertion, which is called emphatics,

Degree of uncertainty, which is called hedges,

Attitude toward a fact or idea, which is called evaluative.

VandeKopple (Citation1985) classification of metadiscourse was influenced by truth conditional semantics. VandeKopple (Citation1985, cited in Quintana-Toledo, 2009) categorized and classified metadiscourse into seven types:

text connectives (e.g. however);

code glosses (e.g. this means that);

illocution markers (to conclude);

narrators;

validity markers (hedges, emphatics, and attributors);

attitude markers (surprisingly);

commentaries (you might not agree with that).

In this classification, the first four are textual and the remaining three are interpersonal.

Hyland (Citation2004) provided a new model of metadiscourse as the interpersonal resources required to present propositional material appropriately in different disciplinary and contexts in his article “Disciplinary interactions: metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing”. He tried to explore how advanced second language writers deploy the ways writers’ project themselves into their discourse to signal their attitudes and commitments in a high stakes research genre. As Table suggests Hyland (Citation2004) developed a new taxonomy which mainly consists of two parts: Interactive Resources and Interactional resources.

Table 1. Hyland’s model for interactional resources

In Hyland’s model, the Interactional Resources focus on the participants’ interaction. They include:

Interactional resources display the writer’s persona and a tenor consistent with the norms of the disciplinary community.

Hedges show the writer’s reluctance to present propositional information.

Boosters express certainty and emphasize the force of propositions.

Attitude markers express the writer’s judgment of propositional information, conveying surprise obligation, agreement, importance, and so on.

Engagement markers address readers by focusing their attention selectively or by including them as participants in the text through second person pronouns, imperatives, question forms and asides.

Self-mentions include explicit reference to the writer(s) through such pronouns as: I, we, my, our, etc.

In recent years, many researchers and linguists in Iran have been interested in doing contrastive rhetorical studies. Most of them compared the organization of students’ composition in Iran and the United States. We can hardly find a contrastive study of the composition of Persian native speakers and the natives of other languages except for English. The results of these studies have shown that the use of metadiscourse is different among different social groups. Some studies indicated that a particular group of metadiscourse is more frequent in students’ writing.

In Iran, for example, Simin and Tavangar (Citation2009) found out that textual MD used more than interpersonal MD by all groups. Noorian and Biria (Citation2010), who used Dafouz’s (2003) classification system in their study, realized that the use of hedges, boosters, and attitude markers are similar in both groups. However, there were significant differences between the two groups regarding the occurrences of interpersonal markers, for example, commentaries and personal markers. Estaji and Vafaeimehr (Citation2015) compared the use of metadiscourse in mechanical and electrical engineering research papers. The results of their finding suggested that there is no significant difference between these two fields of study in the use of metadiscourse. Zarei and Mansoori (Citation2007) did a quantitative analysis of metadiscourse differences between English and Persian. They concluded in their article that “metadiscourse provides a link between texts and community culture, defining the rhetorical context which is created to conform to the expectations of the audience for whom the text is written.” The results of their study suggested that Persian writers employed more metadiscourse elements.

In the Chinese context, Li (Citation2011) collected a corpus of article abstracts and indicated that abstracts display differences in the writers’ disciplinary and linguistic background. Li and Wharton (Citation2012) found out that in a similar discipline, context is a more powerful factor that influences the use of metadiscourse by students. They argued that UK students employ metadiscourse more frequently than Chinese writers. Uk students use smaller account of transition markers than Chinese students. They explained that self-mentions are almost absent in Chinese writings corpus, but are frequent in the essays of UK students. The results of this study also showed that Chinese writers use strong assertions in their rhetoric, and use expressions such as “we must“ and ”you should” to engage with readers. UK students use more hedges, indicating a preference to diminish their commitment to propositions. UK writers show slightly less use of unquoted evidentials than do Chinese. Furthermore, Mu, Zhang, Ehrich, and Hong (Citation2015) in their research article identified that English RAs differed in the employment of metadiscourse features from Chinese RAs. Hedges were Preferred in English RAs to qualify the claims when making the inferences. Chinese RAs tended to use more evidential, Chinese RAs paid much attention to citing resources in academic writing. Also, Chinese RAs were found to prefer using Boosters and self-mentions.

As it is evident, there are very few comparative studies between two nonnative groups of EFL students. Most of the researchers have compared a group of nonnative students with native speakers of English. The present study tries to address this gap and compare the use of metadiscourse markers by two groups of Iranian and Chinese students.

3. Method

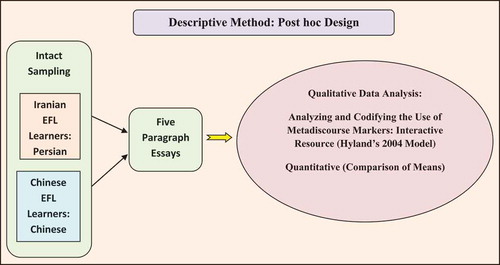

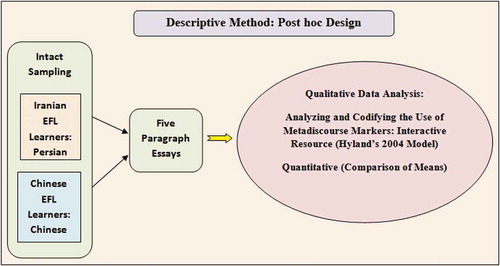

This study followed a descriptive method of research and proceeded through sampling, extracting writing without any treatment, analyzing, codifying, and classifying rhetorical features in argumentative writings of the Iranian and Chinese university students. The procedure has been graphically illustrated in Figure below:

Figure 1. Illustrative methodology of studying the use of metadiscourse markers in argumentative essays by Iranian and Chinese EFL students.

3.1. Participants

Since the study included participants from two countries and the researchers did not afford random sampling from a pool of participants, they followed a non-random and availability sampling method. Therefore, the sampling method applied in this study was intact group sampling from two universities in Iran and one university in China (which was reached through a personal contact that the researchers had in China). A total of 80 students studying at universities located in Qom in Iran and An Hui in China participated in this study. The required data were collected from 40 Iranian students in Islamic Azad University (Qom branch) and Hazrat-e-Masoumeh University in Qom, Iran and 40 Chinese students in An Hui University, School of Foreign Studies, China. The participants were adult university students whose field of study was English. Both groups of students in Iran and China used English as their foreign language. The age of the students ranged from 19 to 35. The only differences between these two groups were their L1 (first language) and C1 (first culture). The L1 of the students in Iran was Persian, and the L1 of Chinese students was Chinese. Iranian and Chinese students were living in two completely different cultural backgrounds in West and East Asia. Both male and female students were under investigation.

The participants from these universities were accessed by means of personal contacts that the researchers had with professors working in the universities in Qom and An Hui. The teachers helped on a volunteer basis. Moreover, students voluntarily participated in the study. The teachers asked their students to take part in this study and write an argumentative essay. Based on the students’ age and cognitive maturation, it was supposed that all participants are mentally able to compose an argumentative essay.

3.2. Materials and instrumentation

The material which provided the data for this study were 80 argumentative essays collected from Iranian and Chinese EFL learners. The materials were the expository essays written by university students in about 90 minutes. In order to have the students produce these essays their teachers had provided them with a topic and had asked them to write an expository essay on that topic. To compare and analyze the differences between metadiscoursal characteristics of the essays, it was vital to have an appropriate model. To this end, the research focused on the interactional resources determined in Hyland (Citation2004) model, consisting of: hedges, boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, and self-mentions. A scale was developed based on Hyland (Citation2004) model and was used as a guideline for scoring the collected essays. The scale guided the raters to identify hedges, boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, and self-mentions in the participants’ argumentative essays.

3.3. Procedure

The following steps were taken in the contexts which were under investigation:

Eighty argumentative essays were collected from two groups of writers: Iranian speakers of English and Chinese speakers of English. The students were advanced university students whose field of study was English. The researchers collected the required data personally with the help of two university teachers in Iran. The data from Chinese students were collected by a Chinese university professor in China, where the professor was teaching English. The Chinese essays were sent to the researchers via E-mail.

Every student wrote a five paragraph argumentative essay. The researchers suggested four different topics to be chosen by students based on their background knowledge and interests. This ensured that in the process of writing students did not have any restriction in accessing information. The writing instruction with its translation into Persian and Chinese were sent to the teachers, and they delivered it to the students. The students wrote the argumentative essays as an assignment after the teachers‘ presentation and instruction. The topics were presented to students and the teachers provided some prompts orally. Students were given one week time to develop their writing.

In order to be sure about the reliability of analysis, a corpus of 20 (10 from each group) essays were analyzed by two experts who were familiar with metadiscourse analysis. Accordingly, the inter-rater reliability of the judgments was measured (0.88) by the researchers implying an acceptable reliability. There were a few occasions where the raters had coded the interactional resources differently from each other.

Finally, the collected data were statistically analyzed by means of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Since the scores were not distributed normally, a parametric test could not be used; therefore, the obtained data were analyzed using Mann–Whitney U Test, which is an appropriate nonparametric statistical test, to examine and determine the differences between the means of the performance of two independent groups.

4. Results

4.1. Test of normality

In order to choose the appropriate statistical test for comparing the means of the performance of two independent groups of Iranian and Chinese argumentative-essay writer, a test of normality was run. The results are presented below:

In Table , the significant values suggest the violation of the assumption of normality. The results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test show that the sig. value is less than 0.05 for all of the interactional resources except transitions. Therefore, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U Test was used to compare the means of the two groups.

Table 2. Test of normality distribution of scores of Iranian and Chinese students in writing argumentative essays

4.2. The comparison of interactional resources

Table presents the result of Mann–Whitney U Test for the mean of six interactional metadiscourse resources in the performance of Iranian and Chinese students in their English argumentative essays.

Table 3. Mann–Whitney U test for interactional resources

Table shows a significance value of 0.000 for interactionals. The probability value (p) is less than 0.05, so the result is significant. The detailed differences included: an insignificant difference in the use of hedges (p > .05); and significant differences in employing attitude markers (sig. = .000); boosters (sig. = .000); engagement (sig. = .000), and self-mention (sig. = .004). As these results show, it can be observed that there were significant differences between the Iranian and Chinese students in writing argumentative essays in terms of “Interactional Resources” by means of boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, and self-mentions; however, no significant difference was found in the use of hedges.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The major purpose of this study was to explore whether there were any statistically significant differences among the types of interactional metadiscourse resources employed by Iranian and Chinese EFL students in their argumentative essay writings in English. Based on the results the Iranian and Chinese students performed differently in their argumentative essays through the use of boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, and self-mentions; however, they performed similarly in the use of hedges.

An initial conclusion based on the quantitative analysis in the current research indicates that both Iranian and Chinese groups used all subtypes of metadiscourse in their writings, although the use of metadiscourse has different functions depending on the cultural context. This finding demonstrates the universal application of metadiscourse. Different applications of metadiscourse markers by Iranian and Chinese students proves the claim about the noticeable influence of local culture on writers’ use of metadiscourse.

More careful scrutiny of the results reveals that the findings of the present research about the hedges are in line with the results of both Chinese and Iranian Contrastive research like and Liu and Huang (Citation2017). Each of these studies separately compared the use of hedges in Iranian and English native speakers’ writings and Chinese and English native speakers’ writings, respectively. Their analysis indicated that Iranian and Chinese authors harmonize with English counterparts by capitalizing on more hedges.

In terms of the other interactive resources (i.e. boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers and self-mentions), the findings of this article are the same as the results of Zarei and Mansoori (Citation2007), which supported the inter-lingual rhetorical differences in the use of metadiscourse resources in English and Persian articles. Li and Wharton (Citation2012) also found out that in similar discipline, context is a powerful factor that influences the use of metadiscourse by students. Yun Li (Citation2011) who collected a corpus of article abstracts is another researcher who firmly indicated that abstracts display differences in the writers’ disciplinary and linguistic background.

The present study aimed to add to the body of literature on the topic of contrastive rhetoric. This study covers the research on this topic in a comparative way into two different cultural settings in the East and West of Asia. This can be the feature which distinguishes this study from similar studies, all of which have compared the non-native EFL learners with English native writers. In addition, the results of the present research provide additional support for the validity of Hyland (Citation2004) analytic tool used in the study.

Like any other study, this study had several limitations. Gender balance was ignored in this study because the number of male and female students who participated in this research was not equal. In each group, we had less than 10 male students.

To conclude, the present study revealed that there were significant differences between Iranian and Chinese EFL students in the use of the majority, though not all, of interactional metadiscourse markers. This being the case, the researchers agree with Kaplan (Citation1966) who first claimed that texts written by people from different L1s and C1s are supposed to be different. This kind of investigation helps to see the effect of students’ first language and culture on the use of metadiscourse markers. Such knowledge then can be used to adapt language teaching methodology to the needs of learners of different countries which can benefit learners in acquiring a foreign language.

The findings of this research along with a number of relevant cross-cultural studies mentioned in this research support the consensus on the existence of cross-cultural differences in rhetorical terms between Persian and Chinese preferred styles. Along this line, the researchers have designed their works around genre analysis, error analysis, or experimental studies. These various designs have partly shed light on different aspects of the existing rhetorical differences, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Furthermore, they have attributed the existence of rhetorical difficulties in L2 writers’ essays mostly to un-proficiency in L2, lack of experience in L1/L2 writing and/or interference of L1.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seyyed Abdolmajid Tabatabaee Lotfi

Seyyed Abdolmajid Tabatabaee Lotfi is an assistant professor in TEFL and a faculty member at Islamic Azad University, Qom branch, Iran. He has his PhD in TEFL from Islamic Azad University, Khorasgan Branch, Isfahan, Iran in 2012. He has published and presented a number of papers in different international journals and conferences.

Seyyed Amir Hossein Sarkeshikian

Seyyed Amir Hossein Sarkeshikian is an assistant professor in TEFL at Islamic Azad University, Qom, Iran. He teaches undergraduate and postgraduate courses in TEFL and English Translation. His main areas of interest include language teaching methodologies, SLA theories, and L2 writing. He has also translated and published some articles and books.

Elaheh Saleh

Elaheh Saleh is a PhD candidate in TEFL. She received her MA degree in TEFL from Islamic Azad University, Qom, Iran. She has been teaching English in different language institutes. This article has been extracted out of Ms. Saleh’s M.A. thesis, supervised by Tabatabaee and Sarkeshikian.

References

- Beauvais, P. J. (1986). Metadiscourse in context: A speech act model of illocutionary content. Retrieved from http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/5470186

- Biria, R., & Yakhabi, M. (2013). Contrastive rhetorical analysis of argumentation techniques in the argumentative essays of English and Persian writers. Journal of Language, Culture, and Translation: (LCT), 2(1), 1–14.

- Bunton, D. (1999). The use of higher level metatext in PhD theses. English for Specific Purposes, 18, S41–S56. doi:10.1016/S0889-4906(98)00022-2

- Canagarajah, S. (2002). Multilingual writers and the academic community: Towards a critical relationship. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 1(1), 29–44. doi:10.1016/S1475-1585(02)00007-3

- Chen, W. C. (2007). Some literature review on the comparison of the Chinese Qi-Cheng-Zhuan-He writing model and the Western problem-solution schema. WHAMPOA-An Interdisciplinary Journal, 52, 137–148.

- Colombo, L. M. (2012). English language teacher education and contrastive rhetoric. Retrieved from http://www.elted.net/uploads/7/3/1/6/7316005/v15_1colombo.pdf doi:10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

- Connor, U. (1996). Contrastive rhetoric: Cross-cultural aspects of second-language writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Connor, U. (2012). New directions in contrastive rhetoric. TESOL Quarterly, 36(4), pages 493–510. doi:10.2307/3588238

- Crismore, A. (1983). Metadiscourse: what it is and how it is used in school and non-school social science texts. University of Illinois: Centre for the Study of Reading. Technical Report 273.

- Estaji, M., & Vafaeimehr, R. (2015). A comparative analysis of interactional metadiscourse markers in the introduction and conclusion sections of mechanical and electrical engineering research papers. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 3(1), 37–56.

- Faghih, E., & Rahimpour, S. (2009). Contrastive rhetoric of English and Persian written texts: Metadiscourse in applied linguistics research articles. Rice Working Papers in Linguistics, 1, 92–107.

- Farrokhi, F., & Ashrafi, S. (2009). Textual meta discourse resources in research articles. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 52(212), 39–75. Retrieved from http://coeweb.fiu.edu/research_conference/ Florida International University.

- Gu, J. Z. (2008). Rhetorical clash between Chinese and Westerners. Intercultural Communication Studies, XVII, 4.

- Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2postgraduate writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13(2), 133–151. doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2004.02.001

- Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing. London: Continuum.

- Kaplan, R. B. (1966). Cultural thought patterns in inter-cultural education. Language Learning, 16, 1–20. doi:10.1111/lang.1966.16.issue-1-2

- Khodabandeh, F., Jafarigohar, M., Soleimani, H., & Hemmati, F. (2013). Overall rhetorical structure of students’ English and Persian argumentative essays. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3, 4. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.4.684-690

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching: From method to post method. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Leki, I. (1997). Cross-talk: ESL issues and contrastive rhetoric. In C. Severino, J. Guerra, & J. Butler (Eds.), Writing in multicultural settings (pp. 234–245). New York: Modern Language Association of America.

- Li, T., & Wharton, S. (2012). Metadiscourse repertoire of L1 Mandarin undergraduates writing in English: A cross-contextual, cross-disciplinary study. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11, 345–356. doi:10.1016/j.jeap.2012.07.004

- Li, Y. (2011). A genre analysis of English and Chinese research article abstracts in linguistics and chemistry (master‘s thesis). Retrieved from http://scholarworks.calstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10211.10/1128/Li_Yun.pdf?sequence=1 doi:10.1094/PDIS-01-11-0064

- Liu, J. J. (2007). Placement of the thesis statement in English and Chinese argumentative essay: A study of contrastive rhetoric. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 4(1), 122–139.

- Liu, P., & Huang, X. (2017). A study of interactional metadiscourse in English abstracts of Chinese economics research articles. Higher Education Studies, 7(3), 25. doi:10.5539/hes.v7n3p25

- Lucaites, J. L., Condit, C. M., & Caudill, S. (1999). Contemporary rhetorical theory: A reader. New York: Guilford Press.

- Matalene, C. (1985). Contrastive rhetoric: an American writing teacher in China. College English, 47(8), 789–808. doi:10.2307/376613.

- Mauranen, A. (1993). Contrastive ESP rhetoric: Metatext in Finnish-English economics texts. English for Specific Purposes, 12, 3–22. doi:10.1016/0889-4906(93)90024-I

- McClanahan, K., & Davis, K. A. (2005). Drawing on Theories of Critical Academic Literacies in the ELI 83 Classroom.

- Mohan, B., & Lo, W. (1985). Academic writing and Chinese students: Transfer and developmental factors. TESOL Quarterly, 19(3), 515–534. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2307/3586276/epdf?r3_referer=wol&track

- Mu, C., Zhang, L. J., Ehrich, J., & Hong, H. (2015). The use of metadiscourse for knowledge construction in Chinese and English research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 20, 135–148. doi:10.1016/j.jeap.2015.09.003

- Noorian, M., & Biria, R. (2010). Interpersonal metadiscourse in persuasive journalism: A study of texts by American and Iranian EFL columnists. Journal of Modern Languages, 20, 64–79.

- Rahman, M. (2004). Aiding the reader: The use of metalinguistic devices in scientific discourse. Nottingham Linguistic Circular, 18, 30–48.

- Rashidi, N., & Dastkhezr, Z. (2009). A comparison of English and Persian organizational patterns in the argumentative writing of Iranian EFL students. Journal of Linguistic and Intercultural Education, 2(1), 131–152.

- Sabzevari, A., & Sadeghi, V. (2013). A contrastive rhetorical analysis of the news reports in Iranian and American case study of news reports in Tehran Times and New York Times. Iranian Journal of Research in English Language Teaching, 1(2), 12- 19.

- Saito, K. (2009). EFL learners and expression of voice: Response to `Ventriloquising the voice: Writing in the University‘. Record of Clinical-Philosophical Pedagogy, 10, 123-127.

- Shen, F. (1989). The classroom and the wider culture: Identity as a key to learning English composition. In L. Yang (Ed.), Contrastive rhetoric: A study of the rhetorical organization of Chinese and American students’ expository essays (pp. 459-466). Shanghai International Studies University. 2003. Reprinted in.

- Simin, S., & Tavangar, M. (2009). Metadiscourse knowledge and use in Iranian EFL writing. Asian EFL Journal, 11(1), 230–255.

- Sloane, T. O. (2001). Encyclopedia of rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sultan, A. H. J. (2011). A contrastive study of metadiscourse in English and Arabic linguistics research articles. Acta Linguistica Hungarica, 5(1), 28–41.

- VandeKopple, W. (1985). Some exploratory discourse on metadiscourse. College Composition and Communication, 36, 82–93. doi:10.2307/357609. Reprinted in Quintana-Toledo, E. (2009).

- Wardy, R. (1996). The birth of rhetoric: Gorgias, Plato, and their successors. London: Routledge.

- Williams, J. M. (1981). Style: Ten lessons in clarity and grace. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

- Yang, L. (2003). Contrastive Rhetoric: A Study of the Rhetorical Organization of Chinese and American Students’ Expository Essays. A Dissertation Presented to Shanghai International Studies University.

- Ying, H. G. (2000). The origin of contrastive rhetoric revisited. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 10(2), 259-268.

- Zamel, V. (1997). Toward a model of transculturation. TESOL Quarterly, 31(2), 341–352. doi:10.2307/3588050

- Zarei, G. H. R., & Mansoori, S. (2007). Metadiscourse in academic prose: A contrastive analysis of English and Persian research articles. The Asian ESP Journal, 3(2), 24–40.