Abstract

Ineffective interprofessional collaboration between healthcare workers can negatively impact patient care. At a time when people are living longer with chronic health conditions, it is becoming increasingly important that university programs incorporate interprofessional education into student training. Despite this urgency, a disconnect remains between current training programs and healthcare workforce needs. The purpose of this study was to examine the effect inclusion of nursing (NSG) students and simulation experiences into a graduate-level speech-language pathology (SLP) course had on increasing the knowledge and skill level preparedness of SLP students entering their hospital externships. Students participated in a series of four classes that incorporated interprofessional education (IPE)-simulation experiences. A quasi-experimental pretest-posttest experimental design was selected to collect SLP student responses. Results suggest SLP graduate students felt significantly more knowledgeable as a result of the simulation experiences regarding the roles and responsibilities of NSG and SLPs in patient care and significantly more prepared in their skills for entering a hospital as a medical SLP intern.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), people are now living longer with multiple chronic conditions. As a result, patient care facilities are facing an increasing shortage of healthcare workers armed with the interprofessional collaboration skills needed to provide quality patient-centered care. In an effort to help bolster the health workforce, the WHO encouraged universities to move away from a discipline-specific training model to an interdisciplinary team approach to practice. However, despite this recommendation, a disconnect remains between current university programs and current workforce needs. While incorporating interprofessional education into training programs has gained momentum, programs are often unsure how to incorporate such training. The current study provides a flexible framework for universities to follow who wish to incorporate IPE and simulation into curriculum. Results contributed to the growing body of literature that finds inclusion of IPE and simulation experiences beneficial to students in healthcare training programs.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, Citation2010), people are now living longer with multiple chronic conditions. As a result, patient care facilities are facing an increasing shortage of healthcare workers armed with the interprofessional collaboration skills needed to face the changing landscape of health care In response, the WHO has identified the need for innovative strategies that can help clinicians, associations, and institutions of higher learning bolster the global health workforce. Moving away from a discipline-specific training model to a collaborative, patient-centered approach to practice, has the potential to meet these growing demands (Rogers & Nunez, Citation2013; World Health Organization, Citation2010). However, in spite of this recommendation, the Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century (Bhutta et al., Citation2010) reports that a disconnect remains between current university training programs and current healthcare workforce needs, with courses being provided in silos, which limits exposure to other disciplines commonly found on collaborative healthcare teams (Gilligan et al., Citation2014).

In an effort to move healthcare training models away from having students learn discipline-specific skills isolated in their various departments, the World Health Organization (Citation2010) and Center for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education, Citation2002) joined forces to encourage academic programs to implement elements of inter-professional education (IPE) into student training. IPE occurs when students from two or more professions work together to learn with, from, and about each other to facilitate effective collaboration, integrated service provision, and improved outcomes for people who need care (Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education, Citation2002; World Health Organization, Citation2010). For example, rather than having physical therapy students learning about patient positioning, speech-language pathology (SLP) students learning about swallowing disorders, and nursing (NSG) students learning about patient nutrition and hydration levels, all of whom are isolated in their departments, students should come together as a team to understand the importance of patient positioning, that aids in safe swallowing of food and liquid, which results in the patient being able to maintain adequate nutrition and hydration levels. When such patient-centered, IPE training is successfully implemented at the university level, clinicians will have the knowledge and collaboration skills necessary to be successful in a team approach to patient care as they enter the healthcare workforce. Thus, moving from a discipline-centric approach to a more inter-discipline academic model will help students build the necessary skills to meet the challenges of a more medically complex patient in a healthcare system facing a shortage of practitioners (Reeves et al., Citation2010).

Fortunately, over the past several years, incorporating IPE into healthcare training programs has been gaining momentum across all disciplines given the ongoing endorsement of the Institute of Medicine (Citation2001, Citation2003, Citation2010)), the World Health Organization (Citation2010) and the IPEC Expert Panel (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, Citation2011a, Citation2011b). Recognizing the growing importance of IPE, the American Speech-Language Hearing Association’s (ASHA) Ad Hoc Committee on IPE developed in 2013 stated, “We need to immediately begin educating the academic arm of our professions so they can begin educating and training other educators, practicing professionals, and future practitioners in IPE and Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC).” Although ASHA’s joining the long list of organizations, institutions, and philanthropist endorsing an IPE approach to academic training is an encouraging step forward (Goldberg et al., Citation2012; Johnson, Citation2013), programs in communication sciences and disorders (CSD) are at times unsure how to incorporate such training into their graduate-level coursework. Luckily, emerging IPE research within the field of CSD is helping guide the way towards a new future of academic training models (Benadom & Potter, Citation2011; Estis et al., Citation2015; Friberg et al., Citation2013; Goldberg, Citation2015; Goodman et al., Citation2016; Potter & Allen, Citation2013; Theodoros et al., Citation2010; Thompson et al., Citation2016; Zook et al., Citation2018; Zraick et al., Citation2003).

Over the years, one common theme emerging from the literature that seems to foster a successful IPE training experience is one that helps students understand not only their own professional identity, but understand the role and responsibilities played by other healthcare team members (Bridges et al., Citation2011). “Roles and Responsibilities” is one of the four IPE collaborative competency domains established by the IPEC Expert Panel (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, Citation2011a, Citation2011b), with the others being “Values and Ethics, Interprofessional Communication, and Teams and Teamwork.” The learning objective for “Roles and Responsibilities” is for students to gain a clearer understanding of their own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of patients. One approach to achieving this goal is by combining IPE with simulation experiences. Simulation environments and activities can take many forms, for example, simulation labs designed to replicate an intensive care unit (ICU) or hospital floor, high-tech/high-fidelity mannequins called “Human Patient Simulators” (HPS) designed to simulate real patient impairments, standardized patients (e.g., trained actors), task trainers, computer-based virtual reality, and roleplaying activities (Brown et al., Citation2018; Dudding & Nottingham, Citation2018; Hill et al., Citation2013; Interprofessional Curriculum Renewal Consortium, Australia, Citation2013; Maran & Glavin, Citation2003; McGaghie et al., Citation2016). Combining IPE and simulation can provide many benefits to healthcare academic training programs. For instance, according to Engum and Jeffries (Citation2012), IPE, combined with the use of simulation in a setting closely resembling a real hospital, creates an environment in which IPC, problem-solving, and decision-making skills are developed and nurtured in a safe environment. Burnes et al. (Citation2012), found pairing SLP students with medical students in patient care simulation experiences with actors portraying the role of an aphasic patient can foster effective patient–provider communication and shared decision-making skills. With the potential benefits of incorporating IPE and simulation into graduate training for CSD, more programs are becoming increasingly interested in infusing such experiences into their current curriculum (Dudding & Nottingham, Citation2018).

While the benefits of incorporating simulation experiences are well documented in other disciplines (Alinier, Hunt & Gordon, Citation2004; C. Cook et al., Citation2000; D. A. Cook et al., Citation2011; Estis et al., Citation2015), the effectiveness of simulation use in CSD remains uncertain. While emerging evidence in CSD supports its use in training clinical skills such as nasal endoscopy and speech evaluation on tracheostomized patients (Benadom & Potter, Citation2011; Estis et al., Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2013; Potter & Allen, Citation2013; Syder, Citation1996; Ward et al., Citation2014, Citation2015; R. Zraick, Citation2002; Zraick et al., Citation2003), curriculum guidelines regarding the use of simulation remain unestablished (Nelson et al., Citation2017). This may be due in part to challenges such as the cost and maintenance required to operate a simulation center, lack of faculty interest, and limited resources for departments that are sharing a simulation center with others on campus (Goldberg, Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2013; Reeves et al., Citation2017). In 2018, Dudding and colleagues investigated these challenges through the use of a web-based questionnaire sent to 309 SLP and audiology programs in the United States. Out of 309 programs surveyed, only 69 schools reported the use of simulation experiences, with standardized patients or computer-based simulations being the most common. In general, the majority of respondents felt the use of simulation would enhance their clinical training programs (i.e. increased student confidence, reduced anxiety, repeated practice in a safe environment, increased preparedness for externships, and access to a broader range of client types); however, significant barriers to implementing such activities were revealed, including a lack of knowledge, limited financial resources, undertrained faculty, and little guidance from accrediting bodies. In the end, results of this study suggested that schools are growing to accept the use of simulation more readily, however, the authors emphasized that challenges identified must be met in order to promote widespread use of simulation activities across CSD programs.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect inclusion of NSG students and simulation experiences into a graduate-level SLP course has on increasing the knowledge and skill level preparedness of SLP students entering their hospital externships. First, authors present a theoretical background for their experimental design and basis for their survey development. Second, the experiment’s methodology and results of data analysis will be presented. Third, a discussion will unfold regarding student learning outcomes. Finally, limitations and considerations for future studies will be provided.

1.1. Background

In an effort to better understand ways to implement IPE and the use of simulation experiences into graduate student curriculum, the current project used campus resources available and a graduate course in SLP to implement a series of IPE-simulation experiences. Kolb’s experiential learning theory was the framework employed to guide the current project (Kolb, Citation1984; Kolb & Kolb, Citation2009). Kolb’s theory was selected given that it offers both a foundation and process for knowledge acquisition based on the needs of each individual learner. While adult learning theory and contact hypothesis are often cited as a guiding framework for IPE, a recent literature review by Abu-Rish et al. (Citation2012) revealed only 3.6% explicitly mention contact hypothesis as a guiding framework. Additionally, in adult learning theory, learning outcomes and goals are directed by the individual learner. Given that IPE is a group-learning experience, learning styles of all students need to be considered; the responsibility of learning in IPE is shared among all members of the group, not just one individual (Barr, Citation2013; Poore et al., Citation2014). Thus, Kolb’s theory applied to IPE incorporates four learning styles into simulation activities where students participate in: 1) concrete experiences and reflective observation (Diverging Learner); 2) reflective observation and abstract conceptualization (Assimilating Learner); 3) active experimentation and problem solving (Converging Learner); and 4) active, hands-on experiences and experimentation (Accommodating Learner). To capture effectiveness of the IPE-simulation experiences, the current study partially replicated the survey format of Hill et al. (Citation2013). The Hill et al. (Citation2013) survey was designed to capture undergraduate and graduate SLP student’s levels of anxiety and confidence following simulation experiences that included case history interview practice with a standardized patient (actor portraying a parent of a child with language delay), clinical teaching workshops, and role-playing. Students were asked to complete the survey pre- and post-experience. Results revealed all participants had decreased anxiety levels following the experience, with those of the undergraduate students at a significant level. Participants also reported significantly increased confidence in a range of clinical skills and evaluated the program positively.

1.2. Purpose

The purpose of the current project was to 1) increase the knowledge of students regarding the roles and responsibilities of NSG and speech-language pathologists (SLPs) in the assessment and intervention of patient care; and 2) increase SLP graduate student skill level preparedness for entering a hospital externship placement. In particular, the current study addresses the following research questions:

How does a series of IPE-simulation experiences impact SLP graduate students’ knowledge of the role and responsibility of NSG and their involvement in patient care as it pertains to an SLP caseload, as measured by a pretest-posttest survey using a 5-point Likert scale?

How does a series of IPE-simulation experiences prepare SLP graduate students for the clinical skills required of a medical SLP intern, as measured by a pretest-posttest survey using a 5-point Likert scale?

It was hypothesized that 1) SLP graduate students would be significantly more knowledgeable regarding the roles and responsibilities of NSG and SLPs in the assessment and intervention of patient care and 2) significantly more prepared regarding their skills for entering a hospital externship placement analogous to the growing body of research supporting the use of IPE and simulation in allied healthcare academic training programs.

2. Methods

Our study was a quasi-experimental pretest-posttest experimental design (Shadish et al., Citation2002). Participants were consented before study participation in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at California State University Fullerton. Participants were second and third-year graduate SLP students enrolled in an M.A. CSD program (n = 18), and fourth-year undergraduate NSG students enrolled in a BSN-RN program (n = 7). SLP students included 1 male and 17 female students. NSG students included 1 male student and 6 female students. All SLP students had completed one graduate-level course in adult neurogenic communication disorders, one semester of on-campus clinic, had yet to take or were currently enrolled in a graduate dysphagia course, and none had completed their advanced clinic/off-campus hospital placement. SLP students were required to attend the IPE-simulation experiences as part of an advanced neuro/medical SLP course instructed by the Principle Investigator of this project. NSG students volunteered to participate and had a history of working in the Nursing Simulation Lab.

2.1. Procedures

Students were sent an email with directions to access an online consent form and survey using Qualtrics (Citation2017). Class time was set aside immediately before the first simulation experience allowing SLP students time to take the survey together using their personal laptops. Immediately following all four IPE-simulation experiences, class time was again set aside for all SLP students to complete the posttest survey together on their personal laptops. NSG students did not participate in the pretest-posttest survey as they were not the focus of this particular investigation. SLP students answered a total of 32 randomized survey questions (7 IPE, 25 SLP skill based) using a 5-point Likert scale. Two of the IPE questions addressed SLP students’ level of confidence and preparedness in collaborating with NSG and five questions addressed their knowledge of NSG’s role and responsibilities in patient care. The 25 remaining SLP skill level preparedness questions assessed SLP students’ confidence, preparedness, knowledge, clinical competence, and anxiety given various scenarios within a hospital setting (completing a speech-language evaluation on an aphasic patient, completing a bedside swallow evaluation, completing a Passy Muir Valve (PMV) speech evaluation, working in a hospital setting, and providing patient care in the ICU). Demographic questions were presented last which include gender, program year, and prior level of exposure to an SLP and/or nurse in an inpatient hospital setting.

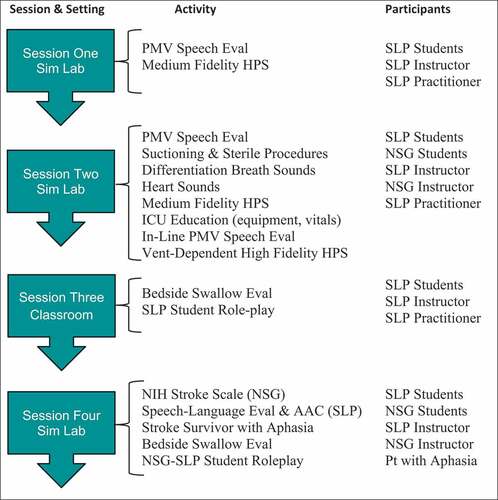

The series of IPE-simulation experiences took place over four class sessions early in the semester and involved a variety of simulation activities (see Figure for a summary). While the third session took place in an SLP classroom, the remaining three sessions took place at the simulation lab.

The first session focused on conducting a PMV speech evaluation and allowed SLP students to practice this skill using tracheostomized (trached) medium-fidelity HPSs in the simulation lab without NSG students present. Prior to practicing with the HPS, SLP students received a short lecture reviewing tracheostomies and PMV speech evaluation procedures. The SLP students then practiced placement of the PMV and performing a PMV speech evaluation using the HPS via role-play with their classmates, the instructor, and a practicing Medical SLP from the community.

The second session combined SLP students with NSG students in the simulation lab to conduct a PMV speech evaluation using trached medium HPSs. SLP students explained how the PMV speaking valve works while NSG students explained how to safely suction secretions from a trached patient. Throughout the session, SLP students discussed the procedures related to completing a PMV speech evaluation while NSG students helped SLP students better understand suctioning and sterile procedures. SLP students were then given the opportunity to practice suctioning the HPSs and use a stethoscope to listen to various lung/breath sounds and heartbeat. This session also included an ICU patient “Room of Horrors” in which the NSG instructor set up a high-fidelity HPS in the ICU with several errors (e.g., IV dislodged, spilled blood, exposed needles, vomit on the floor, alarming monitors, dangerous monitor readings, etc.). In small groups, SLP and NSG students took time to identify all the many hazards present. This allowed opportunities for SLP students to ask questions and NSG students to educate the SLP students regarding what to look for in an ICU patient’s room and understand vital signs displayed on patient monitors. SLP students were also given the opportunity to practice positioning the HPS in an effort to become more familiar with how to move an ICU patient connected to a variety of monitors, drains, etc. A practicing Medical SLP from the community with expertise in ventilator-dependent patients was present to demonstrate the evaluation process of an in-line PMV on the ventilator dependent, high-fidelity HPS. This allowed SLP and NSG students the opportunity to practice PMV and suctioning skills on a ventilator-dependent patient and ask questions.

The third session took place in the SLP classroom. For this session, NSG students were not present given that the skill trained was discipline-specific for SLPs. The class began with a short lecture on dysphagia and review of procedures for conducting a bedside swallow evaluation. The lecture and review were provided by a practicing Medical SLP from a large medical center in the community who has expertise in dysphagia. Following the short lecture and review, SLP students practiced performing bedside swallow evaluations on their fellow classmates via roleplaying patient-clinician scenarios (e.g., one student portrayed the role of patient while the other portrayed the role of SLP). The class instructor and community SLP supervised and answered questions as needed.

During the fourth session, NSG and SLP students were combined in the simulation lab with an aphasic, stroke survivor present portraying the role of patient. The session started with NSG students completing the National Institute of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale screening on the stroke survivor at bedside while educating the SLP students as to what they are specifically looking for and why. NSG students then made a referral for a “Speech-Language Evaluation.” A smaller group of SLP students demonstrated a speech-language screening at bedside while educating the NSG students about normal and impaired speech and language skills. This was followed by another small group of SLP students who provided a general overview of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) methods and techniques for communicating with speech and/or language-impaired patients. Afterward, a transition was made to focus on bedside swallow evaluations. NSG students got into the hospital beds and SLP students performed a bedside swallow evaluation on the NSG students. Along the way, SLP students provided education and answered questions regarding the purpose of a bedside swallow evaluation, reasons for trying various liquid thicknesses and food textures, demonstrated feeding and swallowing techniques, and explained when an instrumental examination (MBSS or FEES) of swallow function is indicated. NSG students were also given the opportunity to ask questions and practice thickening liquids. Overall, the IPE-simulation lab experiences totaled 11 hours, with each session lasting approximately 2 hours and 45 minutes.

2.2. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics provided the means and standard deviations of SLP students’ responses. NSG students did not participate in the survey. Responses to the 32 randomized survey statements (7 IPE, 25 SLP skills based) were analyzed quantitatively using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all _____) to 5 (extremely ______) where the blank contained the target outcome (e.g., confident, prepared, knowledgeable, competent, anxious). For the ease of interpreting “Anxiety” similar to the other positive traits, “Anxiety” was reverse-coded so that higher values indicated less anxiety. We would expect students to be less anxious after the IPE-simulation experiences. Cronbach’s alpha was assessed to determine the level of internal consistency for each of the 25 targeted SLP skill sets. All scales fell within the acceptable range (.80—.99). Unique identifiers were not used to identify the participants and thus student responses were analyzed using a series of independent sample t-tests. All statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Qualitative data were collected from the SLP student participants after completion of their advanced clinical internship (hospital or medical setting), one-year post IPE-simulation experience, but not analyzed for this part of the study. Some general feedback responses from SLP graduate students are provided in the “Discussion” section.

3. Results

3.1. Prior level of experience

To obtain a clearer picture of student learning based solely on the IPE-simulation experiences, SLP students were asked to provide their prior level of experience. Experience was defined as the length of time spent engaged in direct observation of or participation in the role of an SLP or nurse in an inpatient hospital setting resulting in an enhanced practical knowledge of the skill or practice. More than half had no experience with SLP or NSG within an inpatient hospital setting (see Table ).

Table 1. Prior level of experience of SLP students observing or participating in the role of an SLP or nurse in an inpatient hospital setting

3.2. Confidence and preparedness collaborating with nursing

Independent sample t-tests compared student’s pretest to posttest survey responses on two questions related to their level of confidence and preparedness in collaborating with nursing (Table ). Definitions for all targeted items were provided within the Qualtrics survey (see Table ). All pretest-posttest response differences were highly significant (ps <.001). These results indicate that following the IPE-simulation experiences, students felt significantly more confident and prepared to work alongside nurses in their hospital externship placements.

Table 2. Results comparing pre-test to post-test responses of SLP students

Table 3. Definitions of terms provided to participants on the Qualtrics survey

3.3. Knowledge of nursing roles and responsibilities

A series of independent sample t-tests compared student’s pretest to posttest survey responses on five questions related to SLP student’s level of knowledge regarding nurses’ roles and responsibilities in patient care (Table ). Patient care scenarios included questions related to nursing’s role and responsibilities: 1) in the inpatient hospital setting, 2) in assessing a stroke patient, 3) in assessing communication skills, 4) in assessing the swallow function, and 5) in care management of a trach patient.

Table 4. Graduate SLP Students’ Mean Pre-Post Test Results for the IPE-Simulation Experiences

Again, all pretest-posttest response differences were highly significant (ps < .001). These results indicate that following the IPE-simulation experiences, students felt significantly more knowledgeable regarding nurses’ roles and responsibilities in patient care. Moreover, perceptions of knowledge increases span multiple contexts (e.g., hospitals, besides), as well as different competencies (e.g., bedside swallow, trachea care), suggesting that the simulation experiences contributed to self-perceptions across a broad knowledge base.

3.4. Skill level preparedness

A questionnaire measured the domains of 1) confidence, 2) preparedness, 3) knowledge, 4) competence, and 5) anxiety, which consisted of five questions per domain. Patient care scenario questions per domain were related to working as an SLP in an inpatient hospital setting: 1) performing a speech-language evaluation on an aphasic patient, 2) performing a bedside swallow evaluation, 3) performing a PMV speech evaluation, 4) working as an SLP in an inpatient hospital, and 5) working in the ICU. The scale used had a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alphas between .80—.99). See Table for results.

Table 5. Cronbach’s Alphas of Patient Care Scenario Questions

A series of independent sample t-tests were conducted comparing student’s pretest to posttest survey responses for the five targeted skill sets in various patient care scenarios (see Table ). All pretest-posttest response differences were highly significant (ps < .001). These results indicate that following the IPE-simulation experiences, SLP students felt significantly more confident, prepared, knowledgeable, competent, and less anxious to enter their medical externships and perform skills required of a graduate student Intern. Thus, in addition to increasing perceptions of self-knowledge, the IPE-Simulation experiences also seem to genialize to more global perceptions of preparedness and competence. Likewise, the IPE-Simulation shaped perceptions of confidence and reduced task-based anxiety.

Table 6. Graduate SLP Students’ Mean Pre-Post Test Results for the IPE-Simulation Experiences

4. Discussion

Through a series of IPE-simulation experiences, the goal of this study was to 1) increase the knowledge of SLP students regarding the roles and responsibilities of NSG and SLPs in the assessment and intervention of patient care; and 2) increase SLP graduate student skill level preparedness for entering their hospital externship. IPE and simulation activities included skill practice in the simulation lab using high and medium fidelity HPS, roleplay, and evaluation of an adult stroke patient with aphasia. Results of a quasi-experimental pretest-posttest Qualtrics survey suggest SLP graduate students felt more knowledgeable regarding the roles and responsibilities of NSG and SLPs in the assessment and intervention of patient care and significantly more prepared in their skills for entering a hospital as a medical SLP intern. Results of this study are consistent with previous studies that show students find IPE and simulation experiences of value, improves their comfort level in communicating with other disciplines, and aids in their understanding of each discipline’s roles and responsibilities. Bringing NSG and SLP students together, away from traditional training isolated within their departments, moves our disciplines closer to the WHO’s goal to bolster the health workforce with students better equipped with the communication skills needed to work on interprofessional, collaborative teams in order to meet the needs of a more medically complex patient (Estis et al., Citation2015; Goldberg, Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2013; Potter & Allen, Citation2013; Reeves et al., Citation2010; Thompson et al., Citation2016; Ward et al., Citation2015; World Health Organization, Citation2010; Zook et al., Citation2018).

4.1. Confidence and preparedness collaborating with nursing

Graduate SLP students felt significantly more confident and prepared to collaborate with nurses during their hospital rotation following the IPE-simulation experience. These findings are similar to findings from other studies in which SLP students reported a higher degree of preparedness and confidence following the use of standardized patients and IPE experiences (Hill et al., Citation2013; Potter & Allen, Citation2013; Thompson et al., Citation2016; Zook et al., Citation2018). In the current study, students’ ratings increased from 2.69 to 4.26 for confidence and from 2.08 to 4.21 for preparedness. After completing their hospital rotation, one SLP student commented, “The IPE-simulation experiences helped me to feel more comfortable talking to nurses.” This statement is consistent with Thompson et al. (Citation2016) and Zook et al. (Citation2018) who found students felt significantly more comfortable talking to and working with other healthcare professionals following IPE experiences during their training programs. While our findings, and those of previous studies, appear to have fostered students’ level of comfort when talking to other care providers, as well as their level of confidence and preparedness, it does not guarantee the effectiveness of the IPE experience. Eva and Regehr (Citation2005), encourage researchers and instructors to be mindful that a student’s self-assessment of confidence and/or preparedness may be overinflated. Infusing self-assessment with formal assessments conducted by an instructor and/or licensed SLP may provide a more objective means by which the student can truly see their improvements. Over time, such assessments may help to improve the students’ ability to self-reflect and more accurately judge their true level of performance. In the end, confidence in communicating with nurses is key for a Medical SLP in order to get clearance to see patients, relay assessment results, etc. Role-playing a patient handoff scenario, for example, may have been a helpful formal assessment to include. Future studies and current instructors should consider adding an additional measure of assessment.

4.2. Knowledge of nursing roles and responsibilities

Graduate SLP students felt significantly more knowledgeable of NSG’s role and responsibilities during their hospital placement having participated in the IPE-simulation experiences. These findings are consistent with Potter and Allen (Citation2013) who reported SLP and NSG students acknowledged the unique and complementary roles each discipline contributed to patient care. Potter and Allen (Citation2013) explain that while SLP students were not experienced in the care of a tracheostomized patient, they were able to successfully complete a bedside swallow evaluation while learning about the care provided by NSG. In the current project, one student commented, “The IPE-simulation experiences helped me to become more familiarized with medical terms and procedures used by nurses in caring for patients.” Data analysis from the current project revealed SLP student scores collectively increased on average from 1.29 to 4.08, indicating the IPE-simulation experiences helped SLP students to gain a clearer understanding of their own role and responsibilities in working with patients as well as NSG’s role and responsibilities. One student reported, “Having completed the IPE experiences prior to my hospital placement provided me with the knowledge needed to better explain and integrate my training with that of nurses.” Learning through experience is key to Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory; when students have the opportunity to apply their textbook knowledge and classroom training into a simulation experience, it allows for the integration of theory into practice (Kolb, Citation1984). Thus, it appears the IPE-simulation experiences provided the opportunity for students to learn about each other’s profession, their specific contribution to patient care, practice their skills, and appreciate the importance of collaboration between team members (Potter & Allen, Citation2013; Reeves et al., Citation2010). When developing a plan to incorporate IPE into a CSD graduate program, instructors should consider including students from NSG and/or other allied health programs. Doing so may aid in students understanding not only their role, but the role of others when providing patient-centered care.

4.3. Skill level preparedness

In 2018, Dubbing and Nottingham discuss how health-care simulations in other disciplines improve patient safety, provides the opportunity for students to practice skills in a safe environment, and improves student confidence (see Alinier et al., Citation2004; C. Cook et al., Citation2000; D. A. Cook et al., Citation2011; Estis et al., Citation2015; Ward et al., Citation2015). Similar benefits are beginning to emerge in the field of CSD (Hill et al., Citation2013; Syder, Citation1996; Zraick, Citation2002; R. I. Zraick, Citation2012; Zraick et al., Citation2003). In the current project, graduate SLP students were able to practice performing a speech-language evaluation at bedside on an aphasic patient, perform bedside swallowing evaluations on nursing students and their fellow classmates, perform PMV speech evaluations on medium-fidelity HPSs, and work with a high-fidelity HPS in the ICU alongside NSG students giving SLP students the opportunity to learn about various equipment, common sounds/alarms, and understand vital signs displayed on patient monitors. On average, SLP student skill level improved from 1.20 to 3.84 collectively. These results suggest the IPE-simulation experiences helped SLP graduate students feel more prepared in their skills for entering a hospital as a medical SLP intern. Some SLP student comments included, “The IPE-simulation experiences increased my knowledge about working with tracheostomized patients and performing PMV speech evaluations”; “It was great having the opportunity to practice skills prior to my hospital placement.” These comments suggest providing SLP students the opportunity to practice skills required of them as medical SLP interns can be beneficial, adding to the growing support for such experiences in clinical training programs. Programs in CSD should consider adding simulation experiences into current curriculum, allowing for skill development through experience rather than solely textbooks and lecture (Kolb, Citation1984; Poore et al., Citation2014). Additionally, instructors should be mindful to include a formal assessment of student skill levels (Eva & Regehr, Citation2005)

4.4. Limitations of this study

The greatest limitation of this study is not providing participants with unique identifiers. This would have allowed us the opportunity to establish a baseline and do additional statistical analysis. The study conducted was exploratory/preliminary in nature, allowing the researchers to gain a clearer picture of procedures, scheduling, equipment, and survey administration. Thus, it is recommended that future researchers take time to gather information about IPE-simulation opportunities specific to their campus and design projects that include unique identifiers for student participants.

Although our survey was a partial replication of Hill et al. (Citation2013) which was based on a survey used in a previous study by Wilson et al. (Citation2010), and went through an external review process by a researcher and statistician with expertise in survey research, replicating a previously used survey more closely may strengthen internal validity. While data from non-validated questionnaires and self-reflection commentary can be valuable (Goldberg et al., Citation2015), future studies may want to consider some currently available scales that have stronger validity and reliability, for example, the 19-item Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS: McFayden et al., Citation2006), or the 37-item Assessment of Interprofessional Team Collaboration Scale (AITCS; Orchard et al., Citation2012)

Disproportionate group size is also a limitation. SLP students were registered for the course in which the IPE-simulation experience took place and therefore required to attend. Nursing students volunteered to participate and thus were smaller in number and inconsistent across class sessions. Scheduling time to meet across academic disciplines is a major challenge in IPE (Dudding & Nottingham, Citation2018; Guraya & Barr, Citation2018). Future studies should consider working closely with their allied health programs and schedule the experiences as part of a class or required series of workshops.

Finally, having a second post-test survey given after students complete their hospital externships and/or after having worked professional would confirm the changes in knowledge and skills over time. A post-test survey is currently being developed and will be included in future studies. Researchers should consider including a post-test survey as an additional measure of student learning for their IPE-simulation experiences.

5. Conclusion

This study has contributed to the growing body of literature that finds inclusion of IPE and simulation experiences beneficial to graduate students in the field of CSD. Results suggest that including a series of IPE-simulation experiences into a CSD graduate-level course helped to foster a higher level of preparedness of students to work with NSG and perform skills required of a Medical SLP graduate student intern. Despite the heterogeneity of the experiences, this study demonstrated a means by which to better prepare students to work on collaborative healthcare teams. University programs who wish to incorporate IPE-simulation experiences should consider the skill(s) to be trained, type of simulations, and their available resources (e.g., nursing simulation lab, physical therapy gym, etc.). In an effort to better understand the influence IPE and simulation activities have on SLP graduate students, future studies should consider incorporating additional allied health programs (e.g., Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, etc.). Overall, this study provides a flexible framework for universities to follow who wish to incorporate IPE and simulation into curriculum and provides researchers direction for future studies.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Nursing at California State University Fullerton and Barbara Doyer, MS, BSN, RN, who is the Nursing Simulation Lab instructor and present for all lab sessions. The authors would also like to thank the Medical SLPs from the community who volunteered their time.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Phil Weir-Mayta

Phil Weir-Mayta is an Assistant Professor at California State University - Fullerton. His research interests include examining frameworks for adding interprofessional education and simulation experiences into training programs for Speech-Language Pathology students. The goal of his research is to enhance students’ interprofessional collaboration skills in an effort to better equip them with the communication techniques, knowledge, and confidence needed to participate successfully on interprofessional healthcare teams providing patient-centered care. The research reported in this paper is part of a larger line of research exploring frameworks for universities to follow when incorporating interprofessional education and simulation experiences into training programs for students in communicative disorders.

References

- Abu-Rish, E., Kim, S., Choe, L., Varpio, L., Malik, E., White, A., & Zierler, B. (2012). Current trends in interprofessional education of health sciences students: A literature review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(6), 444–16. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.715604.

- Alinier, G., Hunt, W. B., & Gordon, R. (2004). Determining the value of simulation in nurse education: Study design and initial results. Nurse Education in Practice, 4(3), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-5953(03)00066-0

- Barr, H. (2013). Toward a theoretical framework for interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1(27), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.698328.

- Benadom, E. M., & Potter, N. L. (2011). The use of simulation in training graduate students to perform transnasal endoscopy. Dysphagia, 26(4), 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-010-9316-y

- Bhutta, Z., Chen, L., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Frenk, J., Garcia, P., Horton, R., Ke, Y., & Kelley, P. (2010). Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century: A Global Independent Commission. The Lancet, 375(9721), 1137–1138. Web. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60450-3

- Bridges, D. R., Davidson, R. A., Odegard, P. S., Maki, I. V., & Tomkowiak, J. (2011). Interprofessional collaboration: Three best practice models of interprofessional education. Medical Education Online, 16. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/doi:10.3402/meo.v16i0.6035

- Brown, D., Estis, J., Szymanski, C., & Zraik, R. (2018). Best practices in healthcare simulations in communication sciences and disorders: A task force of the council of academic programs in communication sciences and disorders. http://www.capcsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Simulation-Guide-Published-May-18-2018.pdf

- Burnes, M. I., Baylor, M. A., McNalley, T. E., & Yorkston, K. M. (2012). Training healthcare providers in patient-provider communication: What speech-language pathology and medical education can learn from each other. Aphaisiology, 26(5), 673–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2012.676864

- Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. (2002). Defining interprofessional education. http://caipe.org.uk/about-us/defining-ipe/

- Cook, C., Heath, F., & Thompson, R. L. (2000). A meta-analysis of response rates in web- or Internet-based surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(6), 821–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640021970934

- Cook, D. A., Hatala, R., Brydges, R., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hamstra, S. J. (2011). Technology-enhanced simulation for health progressions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(9), 978–988. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1234

- Dudding, C., & Nottingham, E. (2018). A national survey of simulation use in university programs in communication sciences and disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJSLP-17-0015

- Engum, S. A., & Jeffries, P. R. (2012). Interdisciplinary collisions: Bringing healthcare professionals together. Collegian, 19(3), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2012.05.005

- Estis, J. M., Rudd, A. B., Pruitt, B., & Wright, T. (2015). Interprofessional simulation-based education enhances student knowledge of health professional roles and care of patients with tracheostomies and Passy-Muir® valves. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 5(6), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v5n6p123

- Eva, K., & Regehr, G. (2005). Self-assessment in the health professions: A reformulation and research agenda. Academic Medicine, 80(Suppl.), S46–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510001-00015

- Friberg, J., Ginsberg, S., Visconti, C., & Schober-Peterson, D. (2013). Academic Edge: This Isn’t the Same Old Book Learning. The ASHA Leader, 18(6), 6. https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.AE.18062013.32

- Gilligan, C., Outram, S., & Levett-Jones, T. Recommendations from recent graduates in medicine, nursing and pharmacy on improving interprofessional education in university programs: A qualitative study. (2014). BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 52. Web. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-52

- Goldberg, L. R. (2015). The importance of interprofessional education for students in communication sciences and disorders. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 36(2), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740114544701

- Goldberg, L. R., Koontz, J. S., Rogers, N., & Brickell, J. (2012). Considering accreditation in gerontology: The importance of interprofessional collaborative competencies to ensure quality health care for older adults. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 33(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2012.639101

- Goodman, M., Wegner, J., Storkel, H. L., Daniels, D., Frey, B., & Horn, E. (2016). Interprofessional education in undergraduate & graduate communication science disorders programs: A national exploratory investigation [ProQuest Dissertations and Theses]. Web.

- Guraya, S., & Barr, H. (2018). The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 34(3), 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjms.2017.12.009

- Health Information Center. (2002). Healthy People 2010 Publications and Other Documents. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Print.

- Hill, A., Davidson, B., & Theodoros, D. (2013). The performance of standardized patients in portraying clinical scenarios in speech–language therapy. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(6), 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12034

- Hill, A., Davidson, B. J., & Theodoros, D. G. (2010). A review of standardized patients in clinical education: Implications for speech-language pathology programs. International Journal of Speech-language Pathology, 12(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549500903082445

- IBM Corp. (Released 2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0.

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the twenty-first century. National Academies Press.

- Institute of Medicine. (2003). Health professions education: A bridge to quality. National Academies Press.

- Institute of Medicine. (2010). The healthcare imperative: Lowering costs and improving outcomes—Workshop series summary. National Academies Press.

- Interprofessional Curriculum Renewal Consortium, Australia. (2013). Curriculum renewal for interprofessional education in health. Centre for Research in Learning and Change, University of Technology.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011a, May). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011b, February). Team-based competencies: Building a shared foundation for education and clinical practice. Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

- Johnson, A. (2013). Realizing our educational future - Now: Graduate programs need to realign curricula with a fast-shifting health care environment. The ASHA Leader, February, 37. https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.AE.18022013.37

- King, G., Shaw, L., Orchard, C., & Miller, S. (2010). The interprofessional socialization and valuing scale: A tool for evaluating the shift toward collaborative care approaches in health care settings. Work, 35(1), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-0959

- Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2009). Experiential learning theory: A dynamic approach to management learning, education, and development. In S. J. Armstrong & C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of management learning, education, and development (Ch. 3), 193-197. SAGE.

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

- Maran, N. J., & Glavin, R. J. (2003). Low to high-fidelity simulation - a continuum of medical education? Medical Education, 37(S1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.37.s1.9.x

- McFayden, A. K., Webster, V. S., & Maclaren, W. M. (2006). The test-retest reliability of a revised version of the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 20(6), 633–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820600991181

- McGaghie, W. C., Issenberg, B., Petrusa, E., & Scalese, R. (2016). Revisiting ‘A Critical Review of Simulation‐based Medical Education Research: 2003–2009ʹ. Medical Education, 50(10), 986–991. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12795

- Nelson, S., White, C., Hodges, B. D., & Tassone, M. (2017). Interprofessional team training at the pre-licensure level: A review of the literature. Academic Medicine, 92(5), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001435

- Orchard, C. A., King, G. A., Khalili, H., & Bezzina, M. B. (2012). Assessment of Interprofessional Team Collaboration Scale (AITCS): Development and testing of the instrument. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 32(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21123

- Poore, J., Cullen, D., & Schaar, J. (2014). Simulation-based interprofessional education guided by Kolb’s experiential learning theory. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 10(5), E241–E247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2014.01.004

- Potter, N. L., & Allen, M. (2013). Clinical swallow exam for dysphagia: A speech pathology and nursing simulation experience. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 9(10), e461–e464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2012.08.001

- Qualtrics. (2017). [Computer software]. https://www.qualtrics.com/

- Reeves, S., Palaganas, J., & Zierler, B. (2017). An updated synthesis of review evidence of interprofessional education. Journal of Allied Health, 46(1), 56–61. PMID: 28255597

- Reeves, S., Perrier, L., Goldman, J., Freeth, D., & Zwarenstein, M. (2013). Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), 28. Article CD002213. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3

- Reeves, S., Zwarenstein, M., Goldman, J., Barr, H., Freeth, D., Koppel, I., & Hammick, M. (2010). The effectiveness of interprofessional education: Key findings from a new systematic review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820903163405

- Rogers, M., & Nunez, L. (2013). From my perspective: How do we make interprofessional collaboration happen? The ASHA Leader, 18(6), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.FMP.18062013.7

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin.

- Syder, D. (1996). The use of simulated clients to develop the clinical skills of speech and language therapy students. European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 31(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.3109/13682829609042220

- Theodoros, D., Davidson, B., Hill, A., & MacBean, N. (2010). Integration of simulated learning environments into speech pathology clinical education curricula: A national approach. Health Workforce Australia Simulated Learning Environments Project: Final Report. University of Queensland. Retrieved September 4, 2012, from https://www.hwa.gov.au/sites/uploads/sles-in-speech-pathology-curricula-201108.pdf

- Thompson, B., Bratzler, D., Fisher, M., Torres, A., Faculty, E., & Sparks, R. (2016). Working together: Using a unique approach to evaluate an interactive and clinic-based longitudinal interprofessional education experience with 13 professions. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(6), 754–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1227962

- Wallace, S. E. (2017). Speech-language pathology students’ perceptions of an IPE stroke workshop: A one-year follow up. Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders, 1(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.30707/TLCSD1.1Wallace

- Ward, E. C., Baker, S. C., Wall, L. R., Duggan, B. L. J., Hancock, K. L., Bassett, L. V., & Hyde, T. J. (2014). Can human mannequin-based simulation provide a feasible and clinically acceptable method for training tracheostomy management. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(3), 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJSLP-13-0050.

- Ward, E. C., Hill, A. E., Nund, R. L., Rumbach, A. F., Walker-Smith, K., Wright, S. E., & Dodrill, P. (2015). Developing clinical skills in pediatric dysphagia management using human patient simulation (HPS). International Journal of Speech-language Pathology, 17(3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2015.1025846

- Wilson, W., Hill, A., & Hughes, J. (2010). Student audiologists’ impressions of a simulation training program. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Audiology, 32(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1375/audi.32.1.19

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice.

- Zook, S., Hulton, L., Dudding, C., Stewart, A., & Graham, A. (2018). Scaffolding interprofessional education: Unfolding case studies. Virtual World Simulations, and Patient-Centered Care. Nurse Educator, 43(2), 87–91.DOI: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000430

- Zraick, R. (2002). The use of standardized patients in speech-language pathology. SIG 10. Perspectives on Issues in Higher Education, 5, 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1044/ihe5.1.14

- Zraick, R., Allen, R., & Johnson, S. (2003). The use of standardized patients to teach and test interpersonal and communication skills with students in speech-language pathology. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 8(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026015430376

- Zraick, R. I. (2012). A review of the use of standardized patients in speech pathology clinical education. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 19(2), 112–118. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2012.19.2.112