ABSTRACT

In second language (L2) academic writing, being able to think in the L2 as opposed to thinking in the L1 and then translating into an L2 utterance may contribute to greater success in foreign-language writing. It reduces cognitive load, frees up more time and cognitive capacity to focus on syntactic structures in the target language and achieve synthesis of meaning using target-language vocabulary. The results reported here suggest that L2 learners may perform better in their writing if they avoid generating ideas in or calling upon resources from their native language (L1) to avoid splitting their attention, thus adding to working memory. These findings have implications for the relationship between cognitive load and L1 interference when writing in a second language.

Introduction

Writing in a second language (L2) is a complex exercise, requiring a robust framework and precise execution in order to produce text that is linguistically accurate. The writing process requires great cognitive effort on the part of L2 learners, necessitating their full attention and concentration. Indeed, Dixon and Nessel (Citation1983) believe that writing is more difficult than listening, speaking, or reading.

Evidence suggests that L2 learners seldom consider their thought processes while writing, as their cognitive abilities are overwhelmed and overloaded by the task at hand. It may be that the L2 learner’s translation of his/her original thoughts in his/her native language (L1) into the target language is partly to blame for this cognitive overload when writing. For example, a number of studies have shown that students resort to their L1 in order to produce texts in their L2. According to Veerappan et al. (Citation2013, p. 14), ‘findings show that in reviewing the text, writers for whom English is a foreign language tend to switch more to L1. They review and evaluate their text quality over again in L1. This shows that although the final product is a L2 text, the process of producing the text was orchestrated by using L1’.

Bhela (as cited in Derakhshan & Karimi, Citation2015, p. 2114) points out that learners usually use syntactical structures of their first language if they feel gaps in their L2 syntactical structures for writing in L2. A number of earlier L2 writing studies have also confirmed that L2 students use L1 while writing in L2 (Beare, Citation2000; Beare & Bourdages, Citation2007; Jones & Tetroe, Citation1987; Krapels, Citation1990; Woodall, Citation2002).The use of translation in L2 students’ thinking procedures during L2 writing was also conducted by Cohen and Brook-Carson (Citation2001). Similarly, according to Khuwaileh and Shoumali (Citation2000, p. 174), Arab students ‘usually think and prepare their ideas in their L1 and then translate them into English’. During the writing process, it appears that L2 learners focus their attention and thinking on the translation of words, as a result possibly sacrificing form, leading to poor writing.

Certainly, L2 learners may benefit by working within the target language mode while writing, as translating from native to target language can lead to awkwardness and unnecessary errors. Furthermore, previous research has shown that the time L2 learners spend on mental translation adds to their cognitive load. For example, Sasaki and Hirose (Citation1996) found that good L2 writers can write fluently with little pausing or mental translation. In follow-up research, Sasaki (Citation2002, Citation2004) found that novice writers translated more often from L1 to L2 than did expert writers.

The act of mentally shifting between languages may by itself lead to excessively high cognitive load. As Schoonen et al. (Citation2003, p. 8) have argued, ‘difficulties in fluent retrieval of words or grammatical structures in L2 writing will burden the working memory and thus hinder the writing process as such, not just with respect to writing fluency, but also with consequences for the quality of the text’. In addition, Garner (Citation2009, p. 27) has stated: ‘Good writing results from good, disciplined thinking. To work on your writing is to improve your analytical skills. Grammar and punctuation and citation form are to writing what dribbling is to basketball’. Therefore, the chance of such good writing in an L2 context may be increased by encouraging learners to think progressively more and more in the target language, thus avoiding the issue of disruptive discrepancy between the breadth of ideas that they can express in their L1 and their limited target language lexicon. The large amount of information requiring simultaneous attention during translation overtaxes the processing capacity of the human working memory, which is limited. Accordingly, the increased cognitive load incurred by translating in the face of this discrepancy leads to poor writing that contains fewer grammatically and semantically correct sentences. As Kalyuga et al. (Citation1999, p. 351) pointed out, ‘(o)nly a few elements of information can be processed in working memory at any time. Too many elements may overburden working memory, decreasing the effectiveness of processing’.

The purpose of the present study is to explore the relationship between cognitive load and L1 interference when writing in a target (second) language. According to Lott (Citation1983, p. 256), interference involves ‘errors in the learner’s use of the foreign language that can be traced back to the mother tongue’. Such errors of interference may be avoided if L2 learners think in the target language, thereby limiting the load on their cognitive processing abilities.

For the purposes of this paper, cognitive load is defined as the ‘total amount of mental energy imposed on working memory at an instance in time’ (Cooper, Citation1998, p. 10). The greater the working memory consumed by an L2 writing task, the less mental capacity remains for additional cognitive activities. Given this definition of cognitive load, the application of cognitive load theory (CLT) in the L2 writing context may have potential to inform the extent to which thinking in a target language may improve learners’ writing by reducing the load on working memory resources caused by L1 interference with the target language (by reducing that interference). A number of studies have been conducted to investigate how the L1 is used by L2 learners writing in the target language. Some such studies have focused on the extent to which particular conceptual activities are conducted in the L1 during L2 writing (Weijan, Bergh, Rijlaarsdam, & Sanders, Citation2009). Others have focused on comparisons between overt translation of supplied passages and direct L2 writing (Cohen & Brooks-Carson, Citation2001; Kobayashi & Rinnert, Citation1992). Further studies have compared L1 and L2 usage during writing (Uzawa & Cumming, Citation1989; Wang, Citation2003; Woodall, Citation2002). Previous studies did not provide information regarding the effect of L1 interference in L2 writing on human cognitive abilities.

Furthermore, while CLT has been applied in a range of educational fields, often as a framework for empirical research in learning and instruction (Kirschner, Citation2002; Mayer & Moreno, Citation2003; Paas, Renkl, & Sweller, Citation2004), relatively little of this research has focused on language practice. The present study explores the application and effectiveness of CLT in reducing load on working memory as a result of L1 interference in L2 writing with the ultimate goal of improving L2 writing proficiency if the time is limited.

CLT

According to Clark, Nguyen and Sweller (Citation2011, p. 7), CLT refers to ‘a universal set of learning principles that are proven to result in efficient instructional environments as a consequence of leveraging human cognitive learning processes’. Plass et al. (Citation2010, p. 1) have stated furthermore that ‘(t)he objective of CLT is to predict learning outcomes by taking into consideration the capabilities and limitations of the human cognitive architecture’. From such a perspective, it seems sensible to apply CLT in the context of L2 writing, as writing is a mental process and thinking in an L1 and translating what is thought into an L2 may well overload a learner’s limited working memory capacity, thereby impeding the writing process and leading to poor writing with relatively high frequency of errors. This overload is caused by the time and mental capacity required for an L2 learner to find the L2 words needed to express ideas already existing in his/her mind in the L1. Specifically, according to Miller (Citation1956), short-term memory has a limited capacity of 7 ± 2 ‘chunks’ of information.

Furthermore, Kirschner, Sweller and Clark (Citation2006, in Artino, Citation2008, p. 427) stated that ‘when processing information (i.e. organizing, contrasting, and comparing), rather than just storing it, humans are probably only able to manage two or three items of information simultaneously, depending on the type of processing required’.

Types of cognitive load

In the CLT framework, there are three types of cognitive load: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane (Clark, Nguyen, & Sweller, Citation2006, p. 9). Consideration of these three types and how they might affect each other could offer indications as to how to best avoid problems that can impair the writing process.

Intrinsic cognitive load is defined as ‘a specific number of interacting elements found in a particular task or concept that a person must keep active in working memory and process at the same time in order to understand or know that task fully and completely’ (Paas, Renkl, & Sweller, Citation2003, p. 1). Extraneous cognitive load, on the other hand, is a product of the design or format in which the information is presented (Mayer, Citation2003, p. 50). Finally, Sweller (Citation2010, p. 126) described germane cognitive load as ‘the working memory resources that the learner devotes to dealing with the intrinsic cognitive load associated with the information’. Therefore, intrinsic load depends on the difficulty of the information and content, extraneous load depends on the way of this information or content is presented, and germane load is related to the way in which the information is analyzed. As these concepts clearly show, CLT has implications for the writing process, and specifically for learners’ mental process while writing in the target language. The greater the degree to which learners think in their L1 and translate while writing instead of thinking in the target language, the greater their cognitive load is.

Furthermore, as Cooper (Citation1998) stated, a learner should be able to successfully learn material when the content is simple (low intrinsic cognitive load), even if the extraneous cognitive load is high. However, if the content is difficult (high intrinsic cognitive load), and the extraneous cognitive load is also high, learning will be prevented, because the cognitive load exceeds the mental resources. He believes that intrinsic cognitive load entails a number of elements that must be processed simultaneously in working memory. Note in this regard that Sweller, Sweller and Sweller (Citation1994, p. 304) defined an element ‘as any material that needs to be learned…. When the elements of a task can be learned in isolation, they will be described as having low element interactivity’.

Measurement of cognitive load

Generally, measurement of the cognitive load could be conducted subjectively or objectively. Subjective methods (Paas, Citation1992) include self-report ratings of cognitive load by asking learners to rate their experience of cognitive load on a Likert-type scale. The participants can rate their mental effort on a 9-point rating scale and this measure depends on the monitoring of a participant’s own mental efforts. Kalyuga et al. (Citation1999) introduced another subjective mental effort rating scale which consists of a seven-point scale, ranging from ‘extremely easy’ to ‘extremely difficult’. This method has been used in recent studies by some researchers such as Ayres (Citation2006) and DeLeeuw and Mayer (Citation2008). These methods have proven to be highly reliable and have had the most use.

Objective methods include performance data from dual-task methods and physiological data such as eye- tracking which has been used by (Duchowski, Citation2002) and pupil dilation by (Minassian, Granholm, Verney, & Perry, Citation2004).

Many studies demonstrate the utility of subjective rating scales. According to Sweller, Ayres and Kalyuga, (Citation2011, p. 75) ‘Subjective measures have had a profound influence and provided a useful tool in providing evidence in support of cognitive load theory’.

In this study, subjective scales have been used. Participants were asked to provide a rating of mental effort after completing two essay-writing activities. The rating scale was a 7-point Likert-type scale labeled from 1 as extremely low to 7 as extremely high.

Cognitive load and writing in a target language

Against the background given above, we can see that the overload caused by L2 learners thinking in their L1 while writing in their L2 will involve high element interactivity, which in turn, will raise working memory load and thus intrinsic cognitive load. Moreover, according to Waddill and Marquardt (Citation2011), knowledge retrieval can be viewed as either ‘controlled’ or ‘automatic’. For instance, when learners write in their L1, they do not require much explicit focus on sentence construction, as such writing involves automatic knowledge retrieval. In contrast, when learners write in their L2, they need to think about how to construct sentences correctly, and this requires controlled knowledge retrieval. Such controlled retrieving of knowledge is limited in capacity and requires a lot of effort. Indeed, as Ransdell & Barbier (Citation2002, p. 105) have stressed, ‘(w)hen engaged too much in knowledge retrieval processes, they (students) may not have sufficient cognitive resources left to deal with “higher level” aspects of writing’. For example, during L2 writing, a learner’s tendency to switch back and forth between the native and target languages may interfere with schema acquisition, defined by van Merriënboer (Citation1997, p. 16) as a ‘consciously controlled process that involves mindful abstraction’.

Thus, cognitive resources should be used on direct writing by L2 learners rather than on thinking through the first language (L1) in order to avoid increasing extraneous cognitive load on learners and so facilitate schema acquisition.

As has been suggested above, while writing in their L2, learners have reduced control over their writing quality, because they

first think in their native language,

translate the meanings of words into the target language,

retain this information in their working memory, and

use these words to write sentences.

This complex process of L2 writing imposes a heavy cognitive load on working memory, which has limited storage and simultaneous processing capacity. This high cognitive load is caused by the phenomenon of split attention, which ‘occurs when two or more sources of information must be processed together in order to understand the information being presented’ (Sweller et al., Citation2011, p. 114).

To avoid such split attention, successful L2 writing may need to use L2 linguistic knowledge and successful L2 writers may need to think in the L2. One way this addresses the split attention issue is by avoiding distraction by multiple sources of information needed in the L1 translation method. For example, frequent dictionary searches and translation of words from the L1 to the L2 during the writing process may interfere with schema acquisition (i.e. the learning process). Such use of valuable cognitive resources – finding the meanings of words and translating from the L1 to the L2 – may quickly use up those resources and distract a learner’s attention, precluding concentration on the syntactic and lexical quality of the text. This was the reason for the negative relationship found by Weijan et al. (Citation2009) between the use of the L1 while writing in the L2 and the quality of the L2 text. Moreover, examining the students’ Ll and L2 composing processes and strategies to perform the written tasks, Rashid (Citation1996) observed that less proficient writers switched to L1 more frequently than advanced writers.

CLT is based on the interaction between information and human cognitive abilities applied to process the information. Indeed, the focus in the present context needs to encompass all of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load, as all are related to working memory. As stated by Plass et al. (Citation2010, p. 4), ‘(a)ccording to CLT’s additivity hypothesis, learning is compromised when the sum of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane loads exceeds available working memory capacity and any cognitive load effect is caused by various interactions among these sources of cognitive load’. Note further that these three types of cognitive load all affect each other; according to Sweller et al. (Citation1998, p. 126):

If intrinsic cognitive load is high and extraneous low, germane cognitive load will be high because the learner must devote a large proportion of working memory resources to dealing with the essential learning materials. If extraneous cognitive load is increased, germane cognitive load is reduced and learning is reduced because the learner is using working memory resources to deal with the extraneous elements imposed by the instructional procedure rather than the essential, intrinsic material. Thus, germane cognitive load is purely a function of the working memory resources devoted to the interacting elements that determine intrinsic cognitive load…. Germane cognitive load does not constitute an independent source of cognitive load. It merely refers to the working memory resources available to deal with the element interactivity associated with intrinsic cognitive load.

This study will focus on the possibility that L2 learners can reduce their extraneous cognitive load by thinking in the L2, thereby achieving improved L2 writing proficiency.

Research questions

The objective stated above was addressed through the following research questions:

To what extent does L1 interference in L2 writing generate a heavy cognitive load?

To what extent does L2 writing performance correlate with the level of cognitive load?

Does the time taken to translate mentally from L1 to L2 lead to poorly constructed sentences in L2 writing?

Method

This study used a sample of language-learner essays and a survey questionnaire administered to the same learners to examine the relationship between perceived cognitive load and L1 interference during L2 writing. These samples of essays and the survey questionnaire helped the researcher obtain both quantitative and qualitative data. ‘Combining these methods introduces both testability and context into the research’ (Kaplan, B. & Duchon, D., Citation1988 p. 575).

They were deemed to be the most appropriate data collection methods since they seemed suitable for this study. Although there is no concrete evidence to know in depth what goes on in the L2 composing process, these different types of data enabled the researcher collecting data about cognitive processes.

The purpose of the two writing activities was to collect data on participants’ cognitive processes while composing essays in their L2 with and without using dictionaries. For the survey questionnaire, it enabled the researcher directly obtain from the participants pertinent and precise information concerning their perceptions of the level of cognitive load based on their personal writing experience. According to Bonoma (Citation1985), ‘Collecting different kinds of data by different methods from different sources provides a wider range of coverage that may result in a fuller picture of the unit under study than would have been achieved otherwise’ (as cited in Kaplan, B. & Duchon, D. P.575)

Data were collected among 77 randomly selected college students as part of their final examination following an English L2 writing course, ensuring that the tasks would be taken seriously. The essay activities and questionnaires are described in detail below. The essay and questionnaire data were compared to determine whether cognitive load and translation time correlated with L2 writing performance.

Participants

The 77 participants were college female students at the end of their third year of an undergraduate program at a Saudi university, completing the last in a series of English writing courses. All were native speakers of Arabic with an intermediate level of English proficiency based on their institutional proficiency records and their writing mid-term and final exams results in previous courses. Their passing grades for the previous writing courses ranged from A (highest) to D (lowest). 3.9% obtained an A, 25.97% obtained a B, 64.93% obtained a C, and 5.20% obtained a D. They had passed three writing courses, and at the time of data collection, they were on a writing course in the English department called ‘Advanced Writing’. The qualitative and quantitative data were conducted shortly after their completion of this course at the end of the semester. No participant had ever lived or studied in an English-speaking country.

Procedures

Participants completed two essay-writing activities, which were under timed and proctored conditions by their instructor. First, they were asked by their instructor to write an argumentative essay on a common topic (Why do you think people attend colleges or universities?) within 1 H during class, without using a dictionary of any kind.

Four weeks later, participants were required to write another essay on the same topic, but with an Arabic-English dictionary at their disposal. The use of these two writing activities was aimed at gaining a better understanding of participants’ cognitive processes while composing an essay in their L2. During the writing process for the second essay on the same topic, frequent reference to dictionaries distracted the participants’ attention and hindered the natural flow of their writing. Thus, split attention was required, increasing the cognitive load. Following these two writing activities, participants were required to complete the questionnaire described below; then, the qualitative data from the essay-writing activities were compared with the quantitative questionnaire data.

The researcher corrected the students’ compositions with the help from their teacher. In order to verify the reliability of rating, the researcher compared the results of the two essay-writing activities with their result of writing course in the mid-term and final exam. The results indicated that there were no significant differences between their results in the first task and their results in the mid-term and final exam because their teacher does not allow them to use dictionaries during exams. In contrast, there was clearly a great gap between the results of the second task and their results in the mid-term and final exam.

Questionnaire

After completing the second writing task, the participants were asked to answer the questionnaire according to the experience they had during each of the writing tasks. The questionnaire items aimed to gather information on participants’ perceptions of the level of cognitive load and time taken to translate mentally from L1 to L2 during L2 writing. The questionnaire used in this study consisted of three main parts (see Appendix 1). The first part contained items focusing on participants’ personal information. The second part required participants to rate on a scale of 1 to 7 the mental effort they invested during the L2 writing task (i) when constructing sentences in the L1 and then translating them into the L2 and (ii) when thinking directly in the L2 without relying on the L1. The third part of the questionnaire was divided into two sections. The items in the first section investigated participants’ degree of focus on the target language during the L2 writing task. The items in the second section required participants to indicate on a four-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree–agree–disagree–strongly disagree) their level of agreement with a series of statements about their writing process.

Results

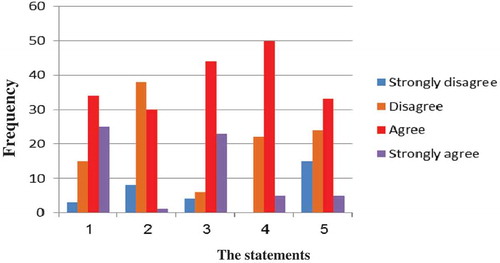

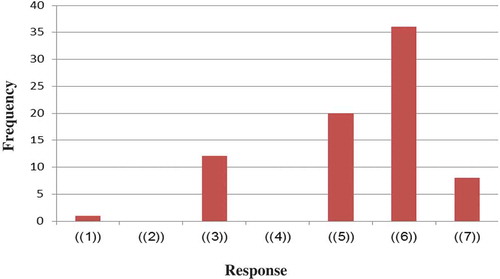

Significant differences were found in the questionnaire responses following the writing activities, indicating that L2 writing performance correlates with level of cognitive load and that L1 interference with the target language contributes to heavy cognitive load. Specifically, the results indicated that during the L2 writing process, participants were tapping a range of different sources of information, which imposed a high cognitive load. In particular, participants reported that they wrote in English by constructing sentences in Arabic and then translating them into English, expending considerable effort. These results suggest that the students invested more mental effort when writing in the target language by constructing the sentences in their L1 and then translating them into the target language. The mean response was 6 and these findings are given in and in .

Table 1. Mental effort invested when constructing the sentences in native language and then translating them into the target language.

Figure 1. Frequency of agreement ratings for mental effort invested when constructing the sentences in the native language and then translating them into the target language.

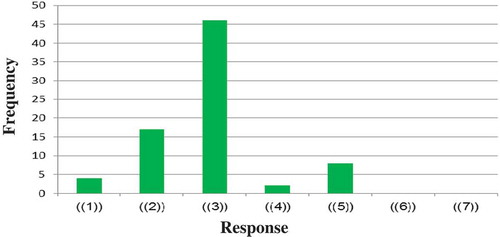

Responses of the questionnaire indicated a positive correlation between participants’ writing performance in L2 English and cognitive load. This item focused on the mental effort expended when directly thinking in English to compose one’s writing in English, without relying on Arabic. The mean response was 3, as can be seen in , and the responses to this item are presented in .

Table 2. Mental effort invested when writing directly in the target language.

Figure 2. Frequency of agreement ratings for mental effort invested when writing directly in the target language.

According to the responses to the items in section 1 of part 3 of the questionnaire following the writing tasks, presented in and , the majority of the participants (54.5%) reported sometimes thinking in Arabic when writing in English. Only (23.4%) reported never thinking in Arabic and then translating into English. Also note that (22.1%) of the participants reported never using a bilingual dictionary, whereas (41.6%) reported sometimes and (36.4%) reported always using a bilingual dictionary. For an English–English dictionary, (19.5%) reported never using an English–English dictionary when writing in English whereas (70.1%) reported sometimes. Furthermore, the majority of the participants (77.9%) reported sometimes their ideas and words usually flow smoothly when writing in the target language whereas (3.9%) reported never. The most common responses on these items are given in the final column of .

Table 3. Responses for degree of focus on the target language during writing activities.

summarizes the findings and shows that the most common responses are (sometimes) and there was a significant difference of frequency of responses on the degree of focus on the target language during writing activities.

Figure 3. Frequency of responses on degree of focus on the target language during writing activities.

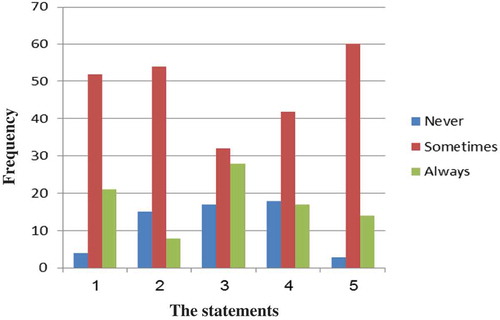

represents the complete list of items for the percentage of those who agree and disagree with each of the five statements. Although the majority of the participants (54.5%) reported sometimes thinking in Arabic when writing in English, the vast majority disagree with relying on their L1 when writing in the target language (49.4%). Also, 57.1% of the participants agree with the statement that thinking in the target language helps them to produce meaningful sentences which are syntactically and semantically correct. Moreover, 64.9% of the participants agree on the idea that the constant comparison of one language to another may hinder the natural flow of writing.

Table 4. Overall responses of the statements.

They indicated a certain amount of disagreement on the statements in section 2 of part 3, the Likert-type responses, as shown in and .

summarizes the findings and shows the frequency of the sample according to the statements.

The analysis of the essays themselves further suggested that the time participants took to conduct mental translation from Arabic to English led to poorly constructed sentences. It appeared that the participants’ performance during the second writing activity, using bilingual dictionaries, was poorer, possibly due to the split-attention effect. The results supporting these assertions are discussed in the following two subsections, respectively focusing on the first and second writing activities.

Performance in the first writing task

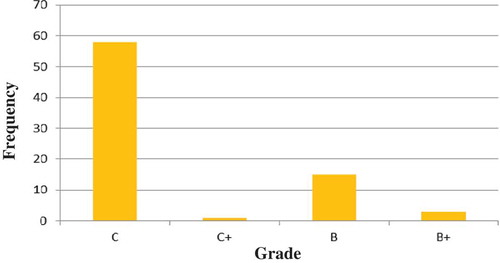

The grades awarded to the essays written during the first activity, when no dictionaries were available, are given in

Table 5. Frequency of grades awarded for the first writing task.

As is clear from , the average grade awarded to essays written without the use of any dictionary was a C. These results are presented in .

The grades awarded to the essays written in the second writing task, when a range of dictionaries was available to the participants, are given in .

Table 6. Frequency of grades awarded for the second writing task.

As can be seen in , the essays written with the use of a range of dictionaries were considerably poorer than those written without. The average grade for these second essays was a Fail.

Comparison of the essay grades in activities 1 and 2

To compare the grades for essays written with and without the use of dictionaries, we used a sign test for paired data (grade differences for each individual). These differences may be positive, negative, or zero. We eliminated ‘zero’ differences (ties) from the sample size because it has no sign. The test statistic is based on the number of positive differences. If S is the sum of positive differences, then the test statistic is as follows:

This follows a standard normal distribution. We calculated the Z-value and the significance (p-value) in order to test the hypotheses:

Ho: There is no significant difference between activity 2 and activity 1 data.

H1: There is a significant difference between activity 2 and activity 1 data.

The results are given in .

Table 7. Significance of the paired essay data.

As is clear from , the p-value is below 0.05, and so we reject Ho. There is a significant difference at level 0.001 between essay grades in activity 1 and those in activity 2, in favor of those in activity 1. The overall response of activity 1 is “c” while the overall response of activity 2 is “f”.

Discussion and implications

There was an overall significant difference between the two writing activities in the present study. The use of two writing activities, one with and one without the use of Arabic dictionaries, allowed for reliable data on participants’ performance in the two conditions. Data were also collected on their perceptions of the mental effort expended when writing in L2 English.

In response to the first question to what extent L1 interference in L2 writing generates a heavy cognitive load, the results showed that the use of an Arabic-English dictionary while writing appeared to have a negative influence on participants’ L2 writing performance, possibly because it acted as a distraction. On the second writing task, more extraneous cognitive load occurs in the working memory because of a split-attention effect produced by constant switching between using the dictionary and writing. Using the dictionary acted as a cognitive load during writing and thus worked to reduce writing performance as it decreased writing fluidity compared to the first task. This would imply that their performance was impaired by the heavy cognitive load caused by such split attention. Statistically significant differences emerged between participants’ performance on the two writing tasks, both overall and across individual participants. On the first writing task, essays were longer and assigned grades were significantly higher than on the second writing task, indicating that the participants wrote significantly better without the use of Arabic-English dictionaries than they did with them. They could avoid losing time and overloading working memory capacity because they kept focused on writing.

In addition, in terms of participants’ self-evaluation of the mental effort expended when directly thinking in English to compose one’s writing in English, without relying on Arabic., the survey findings revealed that the participants’ responses to the survey showed a positive correlation between their writing performance in L2 English and cognitive load. Whereas they invested more mental effort when writing in the target language by constructing the sentences in their L1 and then translating them into the target language.

Moving on to the second and third questions to what extent L2 writing performance correlates with level of cognitive load and whether the time taken to translate mentally from L1 to L2 leads to poorly constructed sentences in L2 writing, the results of the essay task and the questionnaire appear to offer evidence that there is a relationship between cognitive load and L2 learners’ writing performance. Using dictionaries put heavy cognitive burdens on students and resulted in poor writing performance. These findings are consistent with the assertion that the time taken for L2 learners to translate mentally may contribute to poorly constructed sentences, because frequent dictionary use and L1–L2 translation during the writing process may interfere with schema acquisition and impose a heavy cognitive load on working memory, leaving less capacity for the writing task itself.

Moreover, in terms of participants’ self-perceptions of their own L2 writing process, the survey findings revealed that a high percentage of the participants disagreed with constructing sentences in Arabic and then translating them into English. Furthermore, a high percentage of the participants agreed that thinking in English rather than Arabic helped them to produce syntactically and semantically correct sentences in their L2 English writing.

In the studies that have looked and compared direct and translated writing (Cohen & Brooks-Carson, Citation2001; Kobayashi & Rinnert, Citation1994), it was concluded that the lower proficiency writers benefited from composing in the L1 and then translating into the L2 if the time of the task is not limited. Furthermore, Cohen and Brooks-Carson (Citation2001) found in their study of 39 intermediate learners of French who performed two essay writing tasks that two thirds of the students did better on the direct-writing task across all rating scales, and one third did better on the translated task. Similarly, Wang. and Wen (Citation2002) and Beare and Bourdages (Citation2007) found that highly proficient writers hardly used L1 during L2 writing. By the same token, Weijen, Bergh, Rijlaarsdam and Sanders (Citation2009), concluded that using L1 during L2 writing has a negative impact on L2 text quality for Metacomments.

The findings do not support the use of dictionaries and translation from the L1 while writing in the target language when L2 learners are under time pressure. According to Jong, T.D. (Citation2010) ‘when there is no time pressure persons who perform a task can perform different parts of it sequentially, thus avoiding overload at a particular moment’ (123).

Limitations

Although the study has achieved the main objectives and yielded clear results, there are some limitations which can be considered as opportunities for future research. Participants in this study were all third-year university students, and findings are not necessarily generalizable to other L2 learner groups; thus, further research is required across a wider range of L2 proficiency levels. It could be beneficial to conduct interviews alongside the questionnaire to get the qualitative data in order to provide much deeper insights. Also, a possible limitation is that the data collection was limited to female students.

Conclusion

This study set out to investigate the relationship between cognitive load and L1 interference with writing in a target language. A secondary aim was to provide L2 teachers with research-based evidence on the basis of which they might improve the quality and quantity of their students’ L2 writing by reducing extraneous cognitive load. A questionnaire and a sample of essays were used as data upon the basis of which to investigate the actual effect of focusing attention on multiple sources of information as a cause of potential cognitive overload. The study showed that CLT may be usefully applied in the L2 writing context to find ways of minimizing split attention and increasing writing proficiency. The present findings did suggest that writing performance was improved by the reduction of unnecessary cognitive load, in this case by removing the use of dictionaries while writing. It would appear that the use of dictionaries while writing in an L2 causes interference and adds to the load on working memory, causing extraneous cognitive load and impeding the flow of writing.

This study provides teachers with evidence that there is a relation between cognitive load and L2 writing quality. Also, CLT is appropriate for providing some guidance in the writing process because it guides teachers to avoid provoking the split-attention effect in the composing process of L2 learners especially in exams when time is limited. This suggests that the students’ cognitive processing abilities should be taken into consideration by teachers when students are under time pressure.

With regard to further research, it appears that the relationship between cognitive load and L2 writing performance deserves further study because the students’ cognitive abilities are neglected and have not received much attention in previous L2 writing research. Future studies should also investigate its relationships with other variables such as translation and speaking.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Artino, A.R., Jr. (2008). Cognitive load theory and the role of learner experience: An abbreviated review for educational practitioners. AACE Journal, 16(4), 425–439.

- Ayres, P. (2006). Using subjective measures to detect variations of intrinsic cognitive load within problems. Learning and Instruction, 16, 389–400.

- Beare, S. (2000). Differences in Content Generating and Planning Processes of Adult L1 and L2 Proficient Writers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ottawa, Canada.

- Beare, S., & Bourdages, J.S. (2007). Skilled writers‘ generating strategies in L1 and L2: An exploratory study. In G. Rijlaarsdam, M. Torrance., L. Van Waes, & D. Galbraith (Eds.), Studies in writing, vol.20.Writing and cognition: research and applications Amsterdam (pp. 151–161). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Bonoma, T.V. (1985). Case research in marketing: Opportunities, problems, and a process. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(2), 199–208.

- Clark, C.R., Nguyen, F., & Sweller, J. (2006). Efficiency in learning: Evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

- Clark, C.R, Nguyen, F., & Sweller, J. (2011). Efficiency in learning: Evidence based guidelines to manage cognitive load. New York: Wiley & Sons.

- Cohen, A.D., & Brooks-Carson, A. (2001). Research on direct versus translated writing: Students’ strategies and their results. The Modern Language Journal, 85(2), 169–188.

- Cooper, G. (1998, December). Research into cognitive load theory and instructional design at UNSW. Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales.

- DeLeeuw, K.E., & Mayer, R.E. (2008). A comparison of three measures of cognitive load: Evidence for separable measures of intrinsic, extraneous, and germane load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(1), 223–234.

- Derakhshan, A., & Karimi, E. (2015). The interference of first language and second language acquisition. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 10, 2112–2117.

- Dixon, C.N., & Nessel, D.D. (1983). Language experience approach to reading and writing: Language experience reading for second language learners. Hayward, CA: Alemany Press.

- Duchowski, A.T. (2002). A breadth-first survey of eye-tracking applications. Behavior Research Methods, 34, 455–470.

- Garner, B.A. (2009). Garner on language and writing. USA: American Bar Association.

- Jones, S., & Tetroe, J. (1987). Composing in a second language. In A. Matsuhashi (Ed.), Writing in real time: Modelling production processes (pp. 34–57). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Jong, T.D. (2010). Cognitive load theory educational research and instructional design some food for thought. Instructional Science, 38(2), 105–134.

- Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1999). Managing split-attention and redundancy in multimedia instruction. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 13, 351–371.

- Kaplan, B., & Duchon, D. (1988). Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in information systems research: A case study. MIS Quarterly, 12, 571–586.

- Khuwaileh, A.A., & Shoumali, A.A. (2000). Writing errors: A study in writing ability of Arabic learners of academic English and Arabic at university. Language. Culture and Curriculum, 13(2), 174–183.

- Kirschner, P. (2002). Cognitive load theory: Implications of cognitive load theory on the design of learning. Learning and Instruction, 12(1), 1–10.

- Kirschner, P.A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R.E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: an analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41, 75–86. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

- Kobayashi, H., & Rinnert, C. (1992). Effects of first language on second language writing: Translation versus direct composition. Language Learning, 42, 183–215.

- Kobayashi, H, & Rinnert, C. (1994). Effects of first language on second language writing: translation versus direct composition. Language Learning, 42, 183-215. doi:10.1111/lang.1992.42.issue-2

- Krapels, A.R. (1990). An overview of second language writing process research. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Second language writing: Research insights for the classroom (pp. 37–56). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lott, D. (1983). Analysing and counteracting interference errors. ELT Journal, 37(3), 256–261.

- Mayer, R.E. (2003). Elements of a science of e-learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 29(3), 297–313.

- Mayer, R.E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43–52.

- Miller, G.A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81–97.

- Minassian, A., Granholm, E., Verney, S., & Perry, W. (2004). Pupillary dilation to simple vs. complex tasks and its relationship to thought disturbance in schizophrenia patients. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 52, 53–62.

- Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 1–4.

- Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (Eds.). (2004). Advances in cognitive load theory: Methodology and instructional design. Instructional Science, 32(1–2), 1–8.

- Paas, F.G.C. (1992). Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: a cognitive-load approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 429–434. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.429

- Plass, J.L., Moreno, R., & Brünken, R. (2010). Cognitive load theory. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ransdell, S., & Barbier, M.L. (2002). New directions for research in L2 Writing. Netherlands: Springer.

- Rashid, R. (1996). The Composing Processes and Strategies of Four Adult Undergraduate Level Native Malay Speakers of ESL/EFL: Composing, English as a Second Language. Unpublished PhD thesis, Ohio State University.

- Sasaki, M. (2002). Building an empirically-based model of EFL learners’ writing processes. In G. Rijlaarsdam, S. Ransdell, & M. Barbier (Eds.), Studies in writing volume 11: New directions for research in L2 Writing (pp. 49–80). Amsterdam: Springer.

- Sasaki, M. (2004). A multiple-data analysis of the 3.5-year development of EFL student writers. Language Learning, 54(3), 525–582.

- Sasaki, M., & Hirose, K. (1996). Explanatory variables for ESL students’ expository writing. Language Learning, 46(1), 137–174.

- Schoonen, R., van Gelderen, A., de Glopper, K., Hulstijn, J., Simis, A., Snellings, P., & Stevenson, M. (2003). First language and second language writing: The role of linguistic knowledge, speed of processing, and metacognitive knowledge. Language Learning, 53, 165–202.

- Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Educational Psychology Review, 22, 123–138.

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P.L., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. New York: Springer.

- Sweller, J, Sweller, J, & Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4(4), 295-312. doi:10.1016/0959-4752(94)90003-5

- Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J., & Paas, F.G.W.C. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10(3), 251–296.

- Uzawa, K., & Cumming, A. (1989). Writing strategies in Japanese as a foreign language: Lowering or keeping up the standards. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 46, 178–194.

- Van Merriënboer, J.J.G. (1997). Training complex cognitive skills: A four-component instructional design model for technical training. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology.

- Veerappan, V., Yusof, D.S., & Aris, A. (2013). Language-switching in L2 composition among ESL and EFL undergraduate writers. Linguistics Journal, 7(1), 209–228.

- Waddill, D.D., & Marquardt, M.J. (2011). The E-HR advantage: The complete handbook for technology-enabled human resources. Boston & London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Wang, L. (2003). Switching to first language among writers with differing second-language proficiency. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12, 347–375.

- Wang., W., & Wen, Q. (2002). L1 use in the L2 composing process: An exploratory study of 16 Chinese EFL writers. Journal of Second Language Writing Online, 11(3), 225–246.

- Weijan, D.V., Bergh, H.V.D., Rijlaarsdam, G., & Sanders, G. (2009). L1 use during L2 writing: An empirical study of a complex phenomenon. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18, 235–250.

- Woodall, B.R. (2002). Language-switching: Using the first language while writing in a second. Journal of Second Language Writing, 11, 7–28.

Appendix 1.

The Questionnaire

Part I: Personal information

1. Gender: □ Male □ Female

2. Age: ...........................................years old

Part II

1. How would you rate your academic writing in English?

Poor ◸ Satisfactory ◸ Very good ◸ Excellent ◸

2. On a scale of 1 to 7, with one being extremely low and 7 being extremely high, please estimate how much mental effort you invest when you write in the target language by constructing the sentences in your L1 and then translating them into the target language.

3. On a scale of 1 to 7, with one being extremely low and 7 being extremely high, please estimate how much mental effort you invest when you write in the target language by directly thinking in the target language without relying on your L1.

Part III

1. How often do you focus on the following aspects in your writing in the target language?

2. Answer these questions by indicating whether you strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree.