Abstract

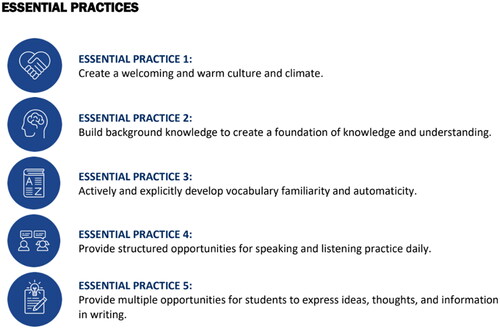

This brief highlights a toolkit resource to support multilingual learners (MLLs) with literacy in STEM. Bridging Language and Learning: Empowering Multilingual Learners in STEM was created for the Department of Defense and its collaborative network of STEM-focused organizations called the Defense STEM Education Consortium. These partners work together to create opportunities for learning and leadership to ensure all students thrive in rigorous STEM classrooms. The resource provides formal and informal STEM practitioners with five essential practices to empower students’ language development and literacy skills in a STEM context: (1) creating a welcoming and warm culture and climate; (2) building background knowledge to create a foundation of knowledge and understanding; (3) actively and explicitly developing vocabulary familiarity and automaticity; (4) providing structured opportunities for speaking and listening practice daily; (5) providing multiple opportunities for students to express ideas, thoughts, and information in writing. The toolkit offers 142 strategies for practitioners categorized into these five essential practices and 135 live links to templates and resources for educators to address the specific language needs of their students, including MLLs. These literacy practices for STEM content can be embedded within pre-existing instructional practices in classrooms, outdoor spaces, or wherever learning takes place.

In a rapidly growing global society, careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) are increasingly vital to the economic and social well-being of all. The need for a diverse, highly skilled STEM workforce will significantly increase within the next decade (Krutsch and Roderick Citation2022), at which point it is projected that more than 80% of jobs will require STEM skills. To thrive in STEM careers, individuals must build the necessary background knowledge and vocabulary to “apply, question, collaborate, appreciate, engage, persist, and understand” how STEM concepts can be used to approach challenges from a personal, societal, or global perspective (Mohr-Schroeder et al. Citation2020).

For multilingual learners (MLLs)—particularly those in a learning environment where the spoken language is not their primary language—the ability to communicate complex STEM content and develop key literacy skills is critical, yet educators may feel underprepared to support those learning efforts (The APA Presidential Task Force on Immigration Citation2013; Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2016; Ee and Gándara Citation2020; Rubinstein-Avila and Lee Citation2014).

Recognizing this accessibility hurdle, the Bridging Language and Learning: Empowering Multilingual Learners in STEM toolkit was developed to support the Department of Defense (DoD) and its Defense STEM Education Consortium (DSEC) partners, a collaborative network of STEM-focused organizations that work together to create opportunities for learning and leadership to ensure all students thrive in rigorous and effective STEM classrooms. This toolkit provides formal and informal STEM practitioners with five essential practices (see ) to empower students’ language development and literacy skills in the context of STEM, with a focus on MLLs.

These essential practices were developed based on key strands from Scarborough’s Reading Rope (Scarborough Citation2001), the four language domains of language acquisition (WIDA Consortium Citation2020), culturally sustaining pedagogy (Paris and Alim Citation2017), and authors’ practitioner experiences. The essential practices are research-based components of effective instruction for all students and, in particular, MLLs. The targeted resources and strategies in the toolkit equip educators to support students’ language development and literacy skills in a STEM context, with specific considerations for MLLs. These literacy practices for STEM content can be embedded within pre-existing instructional practices in classrooms, outdoor spaces, or wherever learning takes place.

Essential Practice 1: Create a welcoming and warm culture and climate

Cultivating a positive classroom culture and environment involves fostering a sense of belonging, promoting open communication, building positive relationships, and recognizing the value of each student’s unique contributions to the learning community. This is essential for creating a supportive learning environment where all students, particularly MLLs, can thrive academically and emotionally (Herrera et al. Citation2022). Educators can facilitate a positive culture by encouraging students to ask questions freely and promoting peer-to-peer discussions that provide low-stakes opportunities for MLLs to express their thoughts and ideas.

Essential Practice 2: Build background knowledge to create a foundation of knowledge and understanding

Background knowledge provides a framework for making connections, being exposed to new academic vocabulary, interpreting new information, and engaging in deeper levels of thinking and comprehension (Herrera et al. Citation2022; Recht and Leslie Citation1988). By actively acquiring and expanding their knowledge base, MLLs are exposed to a wider range of vocabulary, concepts, and cultural references that provide a strong foundation for language development.

Incorporating authentic texts and real-world applications offers a tangible connection between language and practical knowledge. Engaging and exposing students to hands-on experiments, research, and inquiry-based learning deepens their background knowledge and facilitates language comprehension by providing students with a solid foundation to interpret data, comprehend complex texts and concepts, and engage in scientific discourse. Through encountering a wide range of texts, such as scientific articles, data sets, technical manuals, and engineering designs, students can see the distinctive ways of reading and writing in each STEM discipline.

Essential Practice 3: Actively and explicitly develop vocabulary familiarity and automaticity

Research shows that vocabulary accounts for 50–60% of the variance in reading comprehension and that students must understand 90–95% of the words in a text to understand the context (Adlof and Perfetti Citation2014; Stahl and Nagy Citation2006; Nagy and Scott Citation2000). As a result, it is important that educators use a deliberate and systematic approach to helping students become highly skilled and comfortable in their use of a wide range of specialized and technical words and terms (August and Shanahan Citation2017; Marulis and Neuman Citation2013). A strong STEM vocabulary empowers students to precisely depict phenomena, interpret data, and express their insights and discoveries. Use visual supports such as labeled diagrams, illustrations, or real-life images to reinforce the meaning of STEM vocabulary and incorporate visual labels for objects, equipment, or materials to allow MLLs to associate the terms with visual representations.

Essential Practice 4: Provide structured opportunities for speaking and listening practice daily

Educators should intentionally create organized activities and experiences in which students can practice and enhance their speaking and listening skills on a daily basis (Fisher and Frey Citation2014). Strong speaking skills enable students to effectively express their thoughts, share their knowledge, and engage in meaningful scientific discourse (National Research Council Citation2012). Engaging in low-stakes discussions, presentations, and collaborative activities allows students to develop social and academic language skills and empowers them to communicate their knowledge effectively, advocate for their ideas, and contribute to scientific conversations with clarity and conviction.

Essential Practice 5: Provide multiple opportunities for students to express ideas, thoughts, and information in writing

Writing in STEM immerses students in writing tasks that mirror real-world STEM scenarios where they can deepen their understanding of complex concepts and apply their language skills in meaningful ways (Lefever-Davis and Pearman Citation2015). As students articulate their knowledge and reasoning through writing, they engage in a process of reflection and organization to communicate their ideas, findings, and solutions clearly and concisely, which strengthens overall reading comprehension (Graham and Hebert Citation2010). Furthermore, writing tasks allow students to practice and develop their language skills, including vocabulary, grammar, and sentence structure (Conrad Citation2008), which is especially important for MLLs.

Conclusion

Implementing the essential practices detailed in the toolkit provides educators with the opportunity to enhance instructional approaches and foster inclusive learning environments wherever learning occurs. We encourage readers to reflect on how they can integrate these practices into their teaching methodologies and reflect on the potential positive impacts on student engagement, understanding, and achievement.

We invite you to contemplate how these practices can be tailored to increase inclusivity and meet the diverse needs of multilingual learners in your classroom. How might pre-existing instructional materials be adapted? What additional support structures could be implemented to facilitate comprehension and participation for students with varying language proficiencies?

For a comprehensive guide on integrating these essential practices and fostering inclusivity in your instruction, we recommend accessing the full toolkit online and exploring the strategies and live links within each of the five essential practices. The toolkit provides practical resources, examples, and further insights to support your journey in implementing these strategies effectively.

The authors welcome continued communication and any questions, insights, or shared experiences from your implementation of these practices. Feel free to reach out for additional guidance or to share your success stories. Together, we can create learning environments that prioritize inclusivity and empower all students to thrive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adlof, S. M., and C. A. Perfetti. 2014. “Individual Differences in Word Learning and Reading Ability.” In Handbook of Language and Literacy: Development and Disorders, edited by C. A. Stone, E. R. Silliman, B. J. Ehren, and G. P. Wallach, 246–264. Guilford Press.

- August, D., and T. Shanahan. 2017. Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Conrad, N. J. 2008. “From Reading to Spelling and Spelling to Reading: Transfer Goes Both Ways.” Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (4): 869–878.

- Darling-Hammond, L., S. Bae, C. M. Cook-Harvey, L. Lam, C. Mercer, A. Podolsky, and E. L. Stosich. 2016. “Pathways to New Accountability through the Every Student Succeeds Act.” Learning Policy Institute. https://oese.ed.gov/files/2020/10/pathways_to_new_accountability_through_every_student_succeeds_act_0.pdf

- Ee, J., and P. Gándara. 2020. “The Impact of Immigration Enforcement on the Nation’s Schools.” American Educational Research Journal 57 (2): 840–871.

- Fisher, D., and N. Frey. 2014. “Speaking and Listening in Content Area Learning.” The Reading Teacher 68 (1): 64–69.

- Graham, S., and M. A. Hebert. 2010. Writing to Read: Evidence for How Writing Can Improve Reading. A Carnegie Corporation Time to Act Report. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

- Herrera, S. G., M. I. Martinez, L. Olsen, and S. Soltero. 2022. Early Literacy Development and Instruction for Dual Language Learners in Early Childhood Education. National Committee for Effective Literacy for Emergent Bilingual Students. https://multilingualliteracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/NCEL_ECE_White_Paper.pdf

- Krutsch, E., and V. Roderick. 2022. STEM Day: Explore Growing Careers. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor Blogs.

- Lefever-Davis, S., and C. Pearman. 2015. “Reading, Writing and Relevancy: Integrating 3R's into STEM.” The Open Communication Journal 9 (1): 61–64.

- Marulis, L. M., and S. B. Neuman. 2013. “How Vocabulary Interventions Affect Young Children at Risk: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 6 (3): 223–262.

- Mohr-Schroeder, M., S. B. Bush, C. Maiorca, and M. Nickels. 2020. “Moving toward an Equity-Based Approach for STEM Literacy.” In Handbook of Research on STEM Education, edited by C. Johnson, M. J. Mohr-Schroeder, T. Moore, and L. English, 29–38. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Nagy, W., and J. A. Scott. 2000. “Vocabulary Processing.” In Handbook of Reading Research, edited by M. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, and R. Barr, 269–284. New York, NY: Erlbaum.

- National Research Council. 2012. A Framework for K–12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. Committee on Conceptual Framework for New K–12 Science Education Standards. Board on Science Education, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Paris, D., and H. S. Alim, eds. 2017. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Recht, D. R., and L. Leslie. 1988. “Effect of Prior Knowledge on Good and Poor Readers’ Memory of Text.” Journal of Educational Psychology 80 (1): 16–20.

- Rubinstein-Avila, E., and E. H. Lee. 2014. “Secondary Teachers and English Language Learners (ELLs): Attitudes, Preparation and Implications.” The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 87 (5): 187–191.

- Scarborough, H. S. 2001. “Connecting Early Language and Literacy to Later Reading (Dis)Abilities: Evidence, Theory, and Practice.” In Handbook for Research in Early Literacy, edited by S. Neuman and D. Dickinson, 97–110. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Stahl, S. A., and W. E. Nagy. 2006. Teaching Word Meanings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- The APA Presidential Task Force on Immigration. 2013. “Crossroads: The Psychology of Immigration in the New Century.” Journal of Latina/o Psychology 1 (3): 133–148.

- WIDA Consortium. 2020. WIDA English Language Development Standards Framework, 2020 Edition. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/WIDA-ELD-Standards-Framework-2020.pdf