ABSTRACT

The research sought the views of basic school teachers in Ghana regarding the forms of professional learning (PL) activities that they engaged in, the challenges in accessing them and how they wanted to be empowered in their PL. A simple random sampling technique was used to select six regions in which 19 teachers were selected across the regions participated. Data were collected through a questionnaire comprising both open-ended and closed-ended questions. The closed-ended questions were analysed and presented in the form of diagrams, while the open-ended questions were analysed thematically. The findings showed that all respondents engaged in some form of PL activities. However, they were confronted with challenges such as inadequate and inappropriate PL resources, poor support and lack of motivation. Hence, they wanted to be empowered through motivation and support with resources to enable them to have control over their own PL and make the needed impact in pupils’ learning.

Introduction

The concepts teacher ‘professional development’ (PD) and ‘professional learning’ (PL) often mean the same and are sometimes used interchangeably in the literature. However, in this research, the term ‘PL’ is preferred as ‘PD’ suggests a deficit in teachers’ knowledge, skills and experiences and needs to be ‘developed’ to enable them to improve in their practice (Van Schalkwyk et al. Citation2015, p. 5). Arguably, when teachers are positioned as professionals who need to be developed, it fails to acknowledge their contextual knowledge about their work (Smith Citation2017) and their agency in their own learning (Tran and Le Citation2018). On the other hand, viewing teachers as professionals who need to learn positions them as active players within their own learning. The right to education has been globally acknowledged to be fundamental for individual and national development. This right includes the right to quality learning (UNCRC, Citation1989). Yet, existing evidence indicates that many children do not enjoy this right. It is estimated that 420 million children world-wide will not learn the fundamental skills expected of them in school by 2030 (UNICEF Citation2019). The SDG 4 on education appears to agree with this claim as contained in its 2019 monitoring report that the disparity between the learning that education systems are providing and what children actually learn in schools is widening as ‘not all who do attend [school] are learning’ (UNESCO Citation2019, p. 30). This implies that many children may not have access to the knowledge and skills they need to discover their potentials.

If all children are to have access to quality learning, then efforts should be made to transform the education system. Such a transformation needs to focus on improving teachers’ classroom practices through continuous PL (Guskey Citation2002). As Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011, p. 376) also note, ‘the importance of … increasing teacher quality and improving the quality of student learning has led to a concentrated concern with professional development of teachers as one important way of achieving these goals’. Yet, teacher continuous professional learning remains one of the challenges facing education systems in many countries. In Ghana, the Ministry of Education appears to recognise this challenge as it points out, in its policy framework document, that the ‘demands of education for the 21st Century Ghana requires a teacher that is adequately prepared’ to be able to assure quality education (Ministry of Education and Ghana Education Service (MOE/GES) Citation2012, p. 5). It is the quality of their continuous professional learning that would guarantee that their contribution to quality education for children is fully realised (Asare et al. Citation2012). In line with this acknowledgement, it has in-service programmes to support teachers in their learning. These programmes take place at three levels: the school, district and national. At the school level, in-service training programmes are determined and organised by headteachers for teachers in their schools based on their determination of areas in need of improvement. The district level programmes are often targeted at equipping headteachers with skills to manage their schools and organise school-based in-service trainings for their teachers, while the national level programmes target education authorities at the district and regional levels. The aim is to equip them with knowledge of national education policies and leadership skills to manage and implement policies.

However, available research evidence in the country suggests that these professional learning programmes are institutionalised and ‘structurally traditional’ where teachers upgrade their knowledge and skills through short courses organised by authorities outside of teachers’ classroom environments (Atta and Mensah Citation2015, p. 48). On other occasions, PL takes the form of workshops where external resource persons or experts are invited to disseminate information to teachers. As these experts are usually not teachers, they are not able to relate realities in teachers’ classrooms and/or schools in order to facilitate teachers’ understanding of their trainings. The challenge with such forms of PL for teachers in the country, as observed by Atta and Mensah (Citation2015), is that they tend to be ineffective in improving teachers’ instructional practices and thus, students’ learning. This is because the impact of such forms of in-service education and training on teachers’ practices is usually transient due to the limited ongoing collegial support for teachers after such trainings (Steward Citation2009). Besides, as ideas presented do not often align with practical realities in teachers’ classrooms, there is usually little or no opportunity for teachers to reflect in their learning and modify already existing practices. Broadening this claim, Asare et al. (Citation2012) argue that many basic school teachers in Ghana participate in these programmes because they have been authorised to do so. This may explain why Hargreaves and Fink (Citation2006) argue that when teachers’ professional learning is based on agendas decided for them, the result is a decline in teachers’ commitment to implementing in their classrooms new knowledge and ideas acquired. Hoban (Citation2002) appears to share in these views as he indicates that changes in teachers’ practices are not an easy and a straightforward process. Therefore, participating in professional learning by means of short programmes or workshops is not enough to make any significant impact in what teachers already do or know.

However, it is important to mention that this is not to say that learning does not occur during short programmes or workshops. But, as Wallace and Loughran (Citation2003) argue, teachers are more likely to reinforce existing practices rather than exploring innovative and new ideas because such sessions contribute little to changing their beliefs about what they already know. What is more promising is a PL that is ongoing and long-term (Lee Citation2005, Steward Citation2009) and situated within the classroom or school context as doing so promotes practical and deep learning based on teachers’ day-to-day experiences and practices (Putnam and Borko Citation2000).

Clearly, a reconsideration is needed regarding teachers’ professional learning in the Ghana Education Service. Contemporary approaches to teachers’ learning suggest that teachers’ learning needs to be contextualised. Hence, PL has to be led by teachers themselves based on their own experiences (Smith Citation2017). There is evidence that when this is done, teachers are more likely to implement reforms that emanate from their own viewpoint. Put differently, teachers’ readiness to apply new learning in their practice relates to their own beliefs about how to improve their knowledge (Brand and Moore Citation2011).

It is against this backdrop that this research focuses on exploring teachers’ own perspectives about their professional learning. It is expected that findings can serve as a tool for managing teachers to improve pupils’ learning. Thus, the research will be guided by the following questions:

What form of professional learning do basic school teachers in Ghana engage in?

What challenges confront teachers in their bid to fulfil their mandate?

How do teachers think they can be empowered to take control of their own professional learning needs?

Review of Related Concepts

The concept of teacher professional learning

We are made to understand that ‘teaching is a complex intellectual and emotional task’ (Whitcomb et al. Citation2009, p. 207). Thus, learning to teach effectively is an evolving process that occurs when teachers have opportunities to continually learn in their profession. According to Craft (Citation2000), PL encompasses all kinds of learning that teachers engage in. Considering that teaching is a lifetime learning job, pre-service training alone may not be enough to completely equip them with all the knowledge and skills that they need for their work. Opportunities for continuous learning are one important way of making them effective.

Professional learning takes different forms, broadly categorised into formal and informal learning. The formal is top-down in nature where learning programmes are decided by policymakers (Tran and Le Citation2018). The learning content focuses on equipping teachers with strategies to enable them to deliver specific curriculum content (Darling-Hammond and Richardson Citation2009). This approach assumes that teachers lack knowledge in their subject matter and current trends in their field. As such, they need in-service training to equip them with specific skills (Day Citation2002). Scholars in favour of this form of learning argue that providing teachers with technical knowledge helps them to improve in their practices (Kennedy Citation2014, Tran and Le Citation2018). According to Smith (Citation2017, p. 6), this form of learning is ‘a one-size-fits-all intention’, which focuses on the most cost-effective ways of providing opportunities for teachers to learn while also attaining the ‘greatest outreach’. However, critics of formal professional learning claim that it relies on ‘tried and true’ ideas and practices (Sachs and Logan Citation1990, p. 479); which are externally developed independent of teachers’ daily experiences (Timperley Citation2008). In his review of existing literature, Alexandrou (Citation2014) found that there were often mismatches between top-down designed teacher professional learning programmes and the kinds of learning that teachers preferred, leading to disengagement in programmes. In Tanzania, Swai and Glanfield (Citation2018) also found that formal approaches did not address teachers’ learning needs as they took place far from the schools and under the control of education officials who had little interactions with teachers after in-service training. There is also evidence that such form of learning undermines teachers’ professional identity and autonomy (Alexandrou, Citation2014, Smith Citation2017, Tran and Le Citation2018); what Bullock, et al. (Citation2010) refer to as deprofessionalisation of teachers. Under such circumstances, teachers may establish a dependency upon outside expertise (Smith Citation2017). This limits their capacity to engage in effective learning and gain the confidence needed to contribute their knowledge to the wider educational discourse.

Professional learning can also be informal also referred to as the ‘growth approach’ to learning. Some argue that teachers have the capacity to identify and focus their own learning around what matters to them (Timperley Citation2008, Van Schalkwyk et al. Citation2015). This form of learning, therefore, shifts from top-down to one where teachers continually learn from their own experiences. Yet, it is observed that the formal form of PL has been promoted at the expense of the informal (Day Citation2002).

Teacher professional learning in the Ghana Education Service

Over the last two decades, one of the key challenges confronting the education sector in Ghana is the effort to enhance the quality of education for children in basic schools (Tamanja Citation2016). Although about 35% of the national budget and 10–12% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product are channelled into the education sector annually, learning outcomes of children are major concerns (Ministry of Education and Ghana Education Service (MOE/GES) Citation2012; Tamanja Citation2016). A major factor contributing to this is ‘poor instructional quality’ (Mensah Citation2016, p. 34). Some scholars attribute this to basic school teachers’ lack of knowledge and skills, particularly in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to augment their instruction (Peprah Citation2016). In their study on teachers’ ICT skills and ICT usage in the classroom, Enu et al. (Citation2018) found that basic school teachers in Ghana rarely used technology to enhance teaching and learning in basic schools because they lacked the ‘skills to integrate ICT in their teaching’. They, therefore, recommended capacity building for teachers through regular in-service education and training on ICT literacy. Making a strong case for teachers to embrace technology in their practice, Amanortsu et al. (Citation2013) argue that children are growing up in a technologically driven society. Therefore, there is the need for teachers to keep themselves abreast with demands of the 21st century in order to deliver the required teaching strategies that are considered relevant to children.

Following these calls, the Ministry of Education and other relevant bodies in the provision of basic education for children in the country have been challenged to support basic school teachers to improve their content and pedagogical knowledge and skills to enable them catch up with the rapid advancement in technology. Hence, in-service education and training for teachers should be such that they produce good quality teachers who are well informed and well equipped with the disposition to learn and acquire new skills and knowledge, so they would be able to guide children to achieve the learning outcomes of the curriculum. In view of this, there is an ongoing national attempt to transform and upgrade teacher continuous professional development programmes through the establishment of the National Teaching Council (NTC) which is mandated under the Education Regulatory Bodies Act, 2020, Act 1023 to ensure improvement in the quality of teachers in the country (National Teaching Council, (NTC)). To achieve this, a new Teachers’ Continuous Professional Development (TCPD) framework has been developed by the NTC to establish a structure for teachers’ education and development in order to make teachers become professionally competent. The framework is based on the new National Teachers’ Standards (NTS) guidelines with the hope that teachers would build their professional competencies and improve their knowledge and practices as they access the relevant TCPD programmes (National Teaching Council (NTC)).

Although it is early days to determine the impact of the ongoing reforms, Allotey-Pappoe (Citation2021) thinks that the ongoing National Teaching Council’s sensitisation workshops for in-service teachers across the country and the disbursement of 354 million Ghana Cedis to teachers in 2020 as continuous professional development allowance signal a good beginning to prioritising continuous professional learning for teachers in the Ghana Education Service.

Conceptualising teacher professional learning for this research

Drawing from the literature, it can be understood that PL is about ‘situatedness’ (Opfer and Pedder Citation2011, p. 397). Therefore, the learning needs of teachers will vary. This implies that PL should move from the ‘technical’ form to a more agentic one. This move unavoidably requires empowering teachers to exercise control over important decisions about what is relevant for their own learning (Easton, Citation2008).

Whitcomb et al. (Citation2009) argue that PL experiences become effective when improvement is placed directly in the hands of teachers themselves. This may explain why Smith (Citation2017, p. 19) claims that ‘professional learning is about noticing’. That is, it is about acknowledging the values and beliefs that teachers hold about their learning. There is evidence that doing this is critical in helping teachers to develop new thinking about their practice in contextually relevant situations (Whitcomb et al. Citation2009). In a similar manner, teachers would be encouraged to promote learner-centred activities in their classrooms (Carpenter and Green Citation2018). A study by the Association for the Development of Education in Africa revealed that where the contexts of teachers’ work were ignored in the design of in-service training programmes, reforms benefitted little from teachers, leading to poor students’ learning outcomes (Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) Citation2016). This research aligns itself with these perspectives and explores teachers’ own thinking about their PL and how they can be empowered in it in order to improve pupils’ learning.

Challenges confronting teacher professional learning

Depending on the context, teachers may experience different challenges regarding their participation in PL. However, within the broader literature, Tran and Le (Citation2018) identify the following challenges: financial limitations, conflicting agendas, lack of teachers’ interest and lack of appropriate PL opportunities. In sub-Saharan Africa, Kelani and Khourey-Bowers (Citation2012) identify teacher motivation, inadequate funding, lack of resources, time constraints and experts’ lack of awareness. They argue that effective PL requires compensations to motivate teachers to participate. Yet, in many countries, there are no extrinsic recompenses for participating in PL programmes. Tied to this are limited funding and resources, which has resulted in the inability of many countries to provide training opportunities. In Ghana, it is often claimed that many teachers cannot access the study leave with pay because of budgetary constraints (Kuuyelleh et al. Citation2014). The Ghana Education Service has placed a quota for granting a study leave with pay to teachers due to financial constraints. In Tanzania, teachers sometimes teach for more than a decade without any opportunity for in-service training due to various challenges including financial and resource constraints (Koda Citation2008).

The use of external experts to provide training to teachers is another major challenge to effective PL. In many countries, trainers lack awareness of the cultural realities of teachers’ work, leading to either failures or poor outcomes of learning programmes (Kelani and Khourey-Bowers Citation2012). Following their study involving teachers in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, Bennell and Akyeampong (Citation2007) identified that in-service training programmes, for instance, were often top-down, unrelated to teachers’ work and not aimed at teachers who needed them most.

It is also claimed that in many countries, teachers are paid poorly. This compels many of them to engage in additional income earning businesses to supplement their salaries (Bennell and Akyeampong Citation2007). Thus, they often have limited time to take part in PL programmes (Kelani and Khourey-Bowers Citation2012). It is widely acknowledged that the challenges confronting teachers in their PL can be demotivating for them and heighten their feeling of neglect.

Methodology

This research explored the views of public basic school teachers in Ghana. Basic schools in the country comprise Kindergarten for children at age four, Primary School for children at age six and Junior High School for children at age thirteen. Participants were therefore teachers selected from these three different levels. This research had the intention of reflecting the national characteristics of basic school teachers in the country. In view of this, the regions in the country were categorised into three main zones for the selection of participants: the Northern Zone that consists of the Upper West, Upper East, North East, Savannah and Northern regions; the Middle Zone made up of Oti, Bono, Bono East, Ahafo and Ashanti regions and the Southern Zone comprising Eastern, Volta, Western-North, Western, Central and Greater Accra regions. Using a simple random technique, the following regions were selected:

Northern zone: Savannah and Upper West regions

Middle zone: Ahafo and Ashanti regions

Southern zone: Western-North and Greater-Accra regions

The original intention of this research was to adopt a qualitative design where data would be gathered through a one-to-one face interview. However, in view of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to strictly observe all laid down protocols in the country, data were collected through a questionnaire, which was designed in two forms. The first, which sought respondents’ background information, comprised closed-ended questions, while the second part, which sought answers to the main research questions, was open-ended to allow respondents to share their views without limitations. The questionnaire was designed in google form and distributed through online to respondents. Respondents were selected through the snowball technique where initial contacts were made to some teachers known to the researchers. These teachers then connected the researchers to their colleagues who were eligible to participate in the research.

A period of 2 months was allowed for respondents to respond. Reminders were sent to those who had not responded after the first month. Nineteen responses were received and the distribution was as follows in :

Table 1. Distribution of respondents

Data from the closed-ended questions were analysed and presented in figure form, while those for the open-ended were analysed thematically by looking for patterns or themes across the data.

Ethical considerations were followed. Informed consent was sought from respondents. It was explained to them that participation in the research was voluntary. Information shared by respondents was also handled confidentially through the use of pseudonyms to represent respondents in the findings in relation to the open-ended responses.

The findings

The research explored three key questions: What form of professional learning do teachers engage in? What challenges confront teachers in their bid to fulfil their mandate? How do teachers think they can be empowered to take control of their own professional learning needs?

The findings presented here address the research questions as derived from the questionnaire.

Demographic information

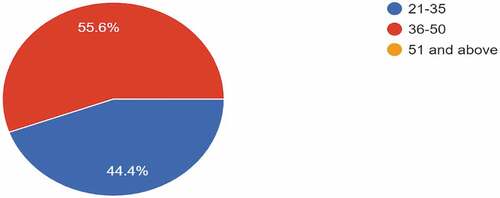

In total, 19 responses were received. However, one respondent chose not to indicate his or her age and sex, hence only 18 were captured under respondents’ demographic information. Out of the 18, eight respondents representing 44.4% were between 21 and 35 years, while 10, representing 55.6%, were between the ages of 36 and 50 as shown in . This implies that, overall, respondents were young and reasonably would be open to new learning and ideas in their practice.

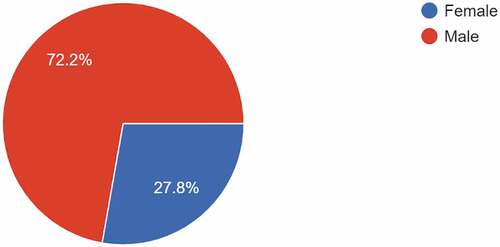

With respect to sex, 13 out of the 18 representing 72.2% were males, whereas five respondents representing 27.8% were females as shown in . Thus, there was not a good representation of respondents in terms of gender in the research. However, this imbalance was technical and not deliberate. It could be an indication of the broader gender imbalances in the teaching field in the Ghana Education Service.

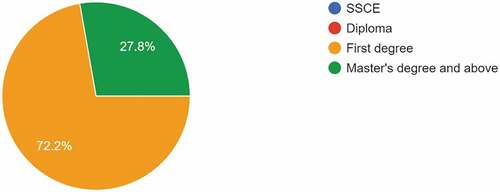

Respondents were also asked to indicate their level of qualification. As seen in , 13 representing 72.2% of the respondents had a first-degree qualification, while five representing 27.8% possessed a master’s qualification and above. This implies that all respondents had the requisite qualification to teach at the basic level as the entry point into the Ghana Education Service is a diploma. It also means that all respondents were professional teachers and therefore were expected to be knowledgeable about their PL needs, the relevance of their PL to their practice and the challenges confronting them.

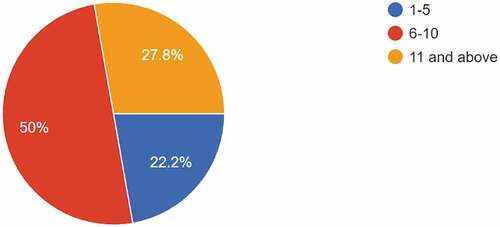

Another demographic information that this research sought from respondents was their teaching experience. The data as presented in show that nine of the respondents representing 50% had taught for 6–10 years, whereas four respondents representing 22.2% and five respondents representing 27.8% had taught for 1–5 years and 11 years and above, respectively. This suggests that respondents had the requisite experience to share with regard to PL for teachers.

Forms of professional learning teachers engage in

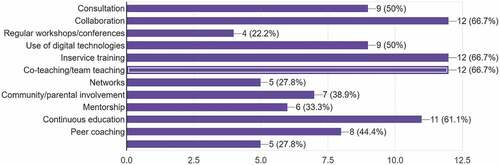

Respondents in this research were asked to select the PL activities that they had engaged in, in the course of their practice as teachers. shows that all respondents had engaged in some form of PL activities in their schools. Majority of respondents 12, representing 66.7% engaged in collaboration, in-service training and co-teaching/team teaching, followed by 11 respondents representing 61.1%, who engaged in continuous education. The least activities were regular workshops/conferences where four respondents representing 23.5% engaged in them.

The professional learning activities had a positive impact on respondents’ work. When asked a follow-up question about how these PL activities influenced their practice, Kyire expressed that she was ‘happy that I am acquiring much knowledge and experience … [because] it has made teaching and learning easy and thus students are able to understand, pass exams and apply it to their daily lives’. For Yatta, these activities ‘help equip me with the necessary content and pedagogical knowledge to enhance my practice … therefore I am confident in my practice’. Vandal made similar claims that ‘they help develop and sharpen one’s abilities and skills with the requisite knowledge for effective delivery’. Therefore, ‘I go about my work with much confidence and better approaches’. Through a workshop on mentorship that Sirem attended, he was able to discover new things which he shared with and used them to guide other teachers on internship training in his school, an experience which seemed to be shared by Pusooni as he claimed that he has used his experience in PL to model other new and inexperienced teachers. Given the ‘varying knowledge’ teachers can derive from participating in PL, Fran encourages ‘professionals [teachers] to consciously and continually update themselves’. According to Stevo, PL has enhanced his scope of understanding in the educational pedagogy, which has ‘improved my teaching methodology’. This may also be the view of Bobaban as he claimed that PL activities ‘are good [because] these programmes help me deliver my lessons effectively without much stress’.

Not only were these activities relevant to their classroom teaching, but also they offered opportunities for some respondents to do further research as claimed by Jagye that ‘it gives me the opportunity to do more research and learn more things’. Jagye reiterated that through PL activities, she was able to ‘electronically prepare my lesson notes and during some lessons, I do make use of technology’. By engaging in PL activities, she also ‘learn to collaborate with others and build communication skills’ through the knowledge and skills acquired. Dapy expressed similar feelings that ‘they [professional learning activities] are good because they help broaden my knowledge about teaching and learning’ through the research that he was engaging in as part of his professional learning.

Challenges confronting teachers in their professional learning

Respondents in this research also identified some challenges they face in their PL. Four themes emerged from the analysis of the data. These were

Inadequate professional learning resources

Inappropriate professional learning resources

Poor support

Lack of motivation

Inadequate professional learning resources

Analysis of the data showed that inadequate resources for teachers to engage in PL were a challenge for teachers in this research as expressed by Kyire that ‘inadequate text books and computers for further research’ were a major problem for teachers in his school. Yattah indicated that the ‘lack of logistics’ in her school militated against teachers’ ability to access information for their PL. This claim was also made by Vandal that ‘insufficient resources’ was a major hindrance for effective upgrading of their knowledge. For some respondents, access to institutions and organisations accredited for providing continuous professional upgrading to teachers was difficult as most of them are located far away from his district. Hence, most teachers in the district were not able to engage in activities to upgrade their knowledge. Pusooni also indicates that there has been inadequate teaching and learning materials for teachers to engage in their PL. It appeared Sabuka did not want teachers to feel helpless about their situation. Rather, ‘I will encourage my colleague teachers to do our best and always try to make good use of the small resources [that] government has given to support us’, she appealed.

Inappropriate professional learning resources

Not only were teachers concerned about inadequate resources, but also about the inappropriateness of the resources for their learning as expressed by Pong that there were inappropriate teaching and learning materials in many schools. Bobaban was teaching one of the technical subjects in his school. This subject involved ‘more practical than theory’ work. He had engaged in some form of PL, including regular workshops and other in-service training. However, his major challenge was that he was not able to apply what was learnt in the classroom due to the lack of appropriate materials to teach students the practical aspects of the subject. This has become a disincentive to him and his colleagues from engaging in any PL activities. In his view, ‘the provision of the appropriate teaching and learning materials’. This claim is shared by Oseima that the teaching and learning materials in his subject area ‘are not the right ones’, which is posing a challenge to him as most of the teaching tends to be theoretical rather than practical because of the lack of the appropriate TLMs. Pusooni in his determination ‘to make teaching become real’ improvised the learning materials.

Poor support

Regarding the ‘support’ theme, respondents were discontented with the kind of support they received in their continuous PL. According to Yattah, ‘workshops are rarely organised’ to support teachers in their PL. She felt that this challenge was attributable to ‘inadequate funds’ at both the school and district levels. This situation was similar in Bobaban’s district as there were ‘inadequate workshops’ and ‘conferences where teachers can learn new methods and how to apply them are virtually absent’.

Dapy indicated that the ‘negative attitude of parents and involvement in the education of their wards’ was a source of worry for her and colleagues in the school. Based on her experience, parents were not collaborating with teachers, and hence, teachers were not able to consult them for information that was useful for teachers in their practice. Lack of support from parents appeared to be widespread as both Richma and Sirem also claimed that parents in their schools were not collaborating with teachers in teaching and learning activities in schools. Hence, they were not able to get the needed support in their practice. Richma attributed this challenge to ‘language barrier’.

Lack of motivation

Concerning the issue of ‘motivation’, it emerged that respondents were dissatisfied as Vandal expressed that there was a ‘lack of motivation from the government, school authorities and parents’ for teachers to engage in learning activities to enable them update their knowledge. Ikea claimed that there was no ‘motivation’ for teachers to further their education, for instance, as part of their PL as acquiring new knowledge and qualification did not lead to any significant increase in their salary. Bobaban indicated that there was no motivation for him to participate in PL activities because there were little avenues for teachers to apply their knowledge and experience acquired from such activities due to the lack of resources. He claimed that as a technical subject teacher, ‘I do buy my own teaching and learning materials for lessons to enable students understand what is being taught’.

Empowerment for professional learning

The third research question sought to identify how teachers wanted to be empowered to have control over their own PL. Respondents expressed some concerns that were analysed and categorised into three key themes:

Resources

Support and collaboration

Motivation

Resources

One of the ways that respondents felt could contribute to empowering them in their PL was the provision of adequate and relevant resources. Vandal said that resources should both be made ‘readily available’ and ‘adequate’ for teachers. He claimed further that ‘equipping the teacher with the needed resources’ is key to their practice as it would help them keep abreast with happenings in their field. Kyire made similar demands that ‘every school should have a well-furnished computer lab’ since access to computers together with the internet was vital to teachers’ work. For Jagye, ‘the use of technology’ and ‘electronic systems’ in teaching and learning is useful for evaluating ‘the impact of strategies [learnt] and to determine what new learning is necessary to promote valued student outcome’. Yattah was not specific regarding the kinds of resources that were needed to empower teachers but expressed broadly that the ‘provision of logistics’ would help teachers in their PL, a view that Pusooni appeared to share in as he said that teachers should be given the appropriate and adequate teaching learning materials. For Richma, ‘professional learning will be effective if the needed materials are provided’. For Stevo, PL centres should be sited near the district for easy accessibility.

Teachers were concerned not only about material resources but also human resource as Oseima indicated that ‘more resource personnel are needed’ in his district. Amajaah also wanted teachers to be provided with digital resources. Schools should have access to internet resources in order to enhance their research and teaching. According to him, ‘teachers need ICT materials’ in order ‘to teach students the practical aspect’ and be effective in their practice.

Support and collaboration

Being provided with the needed support from the stakeholders was the demand of respondents. The excerpt below appears to capture the kind of support that respondents in this research wanted:

More and effective workshops should be organised. Teachers within the district should organise more peer teaching programmes to enable them learn from each other and improve upon their skills and methods of teaching The establishment of a district library to enable both teachers and students do research … The involvement of parents to help in getting the right materials for students which make teaching and learning easier (Bobaban).

The findings revealed that respondents wanted school authority to organise in-service training for teachers as also espoused by Dapy that ‘there should be more in-service training for teachers. He believed that ‘by attending lots of in-service training’, teachers will be equipped with new ideas and become abreast with happenings in their practice. However, for this to be possible, the GES [Ghana Education Service] must provide all that is needed in the schools for effective teaching and learning. According to him, it amounts to nothing if teachers attend in-service training and do not have access to the needed resources in their schools to apply what is learnt. Vandal shared similar views that ‘regular and effective in-service training’ for teachers was an important consideration for empowering them in their PL. He expressed that in addition to in-service training, there should be other ‘flexible means of professional development’ opportunities to allow many teachers participate. Both Pong and Yattah not only appeared to share similar views that there should be frequent PL activities, but more importantly, there should be monitoring and supervision by trainers to ensure that teachers actually apply what they learned in their pre-service training and also continue to receive support through in-service training. Doing this would offer opportunities for both teachers and trainers to engage in ‘reflective practice’, added Yattah.

Respondents also wanted authority to support teachers in the form of ‘scholarship for further studies’, claimed Kyire. This, in his view, will allow many teachers to upgrade themselves in their respective fields. Amajaah made similar demands that teachers should be supported with financial resources to further their education, do more research and attend workshops. Supporting teachers this way would equip them with ‘in-depth knowledge in both practical and theory’ aspects of their work. Sirem wanted opportunities to be created for teachers to embark on more field trips, so they can engage with and share experiences with colleagues in other districts and regions. Jagye suggested ‘creating a network between parents and teachers so information can be [shared] on timely basis’. For Dapy, ’parents must [also] be educated about the importance of their children’s education’. He believed that doing this could maximise parental support for and collaboration with teachers.

Motivation

It was also found that respondents were concerned about motivation to engage in PL activities. Sharing how he feels teachers can be empowered in their PL, Vandal said that teachers needed ‘motivation from all stakeholders’, a view also shared by Yattah. Kyire believed that one way of motivating teachers is by authority reducing ‘the number of years before promotion’ in order to motivate them to pursue further studies. Bobaban needed to be motivated in the form of scholarships to help teachers pursue courses that will improve their skills. For Stevo, there should be equal opportunities for members to benefit from study leave with pay, and the process for the application should not be cumbersome once a teacher qualifies. Fran appeared to agree with the views expressed by indicating that teachers needed some form of ‘incentive’ to engage in PL. He added that, as professionals, teachers ‘must have the freedom to determine what works best in the learning environment’ as this could motivate them to seek more knowledge in their practice.

Discussion

This research was interested in understanding the forms of PL activities that teachers engage in, and the challenges they encountered in accessing them and how teachers can be empowered in their learning. The findings indicate that all respondents had engaged in more than one PL activity in their schools and they felt that these activities were important to their practice in diverse ways. For instance, while some expressed that participating in PL activities enhanced their scope of understanding in the educational pedagogy, others indicated that it offered them opportunity to broaden their knowledge through research and collaboration with different stakeholders in their field. For others, it was fulfilling to be able to use their knowledge to help their pupils in their learning.Existing research advances reasons why, overall, effective PL opportunities matter a lot. It has been argued that when teachers have the opportunity to take part in PL activities, it is likely to reflect in their output (Ginsburg, Citation2009.); as some respondents in this research made similar claims. Other scholars assert that PL impacts, positively, on teachers’ job not only because it can enhance teachers’ delivery, but also gaining knowledge helps them to stay up to date with events happening in their field (Guskey Citation2002). The reason being that teachers work in a continuously changing environment, such that whatsoever knowledge they acquire in their pre-service training is likely to become stale as new ideas surface. That may explain why Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011) make the point that one important way of making teachers effective is to focus on improving the quality of their continuous PL. It is by doing this, that teachers would be able to contribute meaningfully to quality education for children.

This research has also found that although teachers considered PL activities significant to their work and had engaged in some form of PL, this was very little to yield the desired impact. As seen in the findings, teachers needed support with resources to make their participation in PL activities effective. Both human and material resources for their PL were not only inadequate but also inappropriate to allow them to effectively learn and utilise whatever knowledge and ideas they gained in their classrooms. Given that resources are critical for designing and implementing quality PL activities that will improve teaching and learning (Archibald et al. Citation2011), the unavailability of resources, both in quantity and appropriateness, therefore implies that teachers may not be able to effectively and efficiently fulfil their professional tasks, such as assessing the performances of their pupils and attending to their learning needs in the classroom. The views of teachers in this research and the situation of PL for basic school teachers, generally, in Ghana as discussed earlier, are not dissimilar to teachers in many other sub-Saharan African countries. Evidence in the literature reveals that opportunities to access and participate in quality PL progrmmes are either rare or not there at all for teachers in many countries in the sub-region. For instance, as noted earlier, many primary school teachers in Tanzania can teach for about 15 years without having access to in-service trainings due to the lack of resources (Koda Citation2008). Similarly, Ajani (Citation2018) observed that many teachers in primary and post-primary schools in Nigeria are not motivated to engage in in-service professional trainings due to financial constraints. In an earlier research by Bennell and Akyeampong (Citation2007), they found that although the importance of teachers’ continuous professional learning was broadly acknowledged, teachers in many countries in the sub region received little quality in-service training in the course of their careers. According to them, continuous professional learning activities for teachers were generally one-shot, scarce, top-down and unrelated to teachers’ needs. Respondents in the research who included teachers from Kenya, Zambia, Ghana, Malawi, Tanzania, Nigeria, Lesotho and Sierra Leone were generally dissatisfied with the opportunities available to them to access in-service education and training.

Drawing from the findings also, it is clear that enhancing basic school teachers’ sense of professional identity could have a major influence in securing their commitment to implementing knowledge and skills acquired in their PL because ‘the identities teachers develop shape their dispositions [and] where they place their effort’ (Hammerness et al. Citation2007, p. 383–384). This claim appears to be corroborated by Smit and Fritz (Citation2008, p. 100) as they argue that ‘education will not improve with … the provision of workshops addressing policies, teaching practice … unless teachers’ identity receives prominence’. As O’Sullivan (Citation2002) makes us understand further, acquiring and implementing new knowledge can challenge teachers’ existing professional identity which includes teachers’ personal attributes, such as their values and beliefs about teaching. Because of this, teachers are more likely to engage in PL activities that they perceive as presenting little risk to their identity and if they perceive that the proposed improvements in their knowledge and skills have benefits over already existing practices. This is not merely a philosophical argument but a practical one as our identities serve as major motivation forces driving our actions (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2009), whether we are cognisant of this or not (Steward Citation2009).

Moreover, there was little motivation for teachers to engage in PL activities. For some, acquiring new knowledge or higher qualification did not lead to corresponding increase in their remuneration, while others attributed theirs to the lack of the requisite resources to implement PL ideas in their schools as some had to spend their own money to purchase some of the materials. Motivation is a drive behind what a person chooses to do, how well he or she chooses it and for how long to engage in it (Sorinola et al. Citation2013); hence, it is largely believed to be the attribute that propels and directs one’s action (Reeve Citation2001). In the context of teachers PL, research has proven that motivation is crucial for teachers as it is linked to effective engagement in their PL. It is reasonable, therefore, to argue that without effective engagement, there can be no real PL; and by extension, effective teaching leading to meaningful pupils’ learning outcome cannot be guaranteed. In other words, PL activities that are detached from teachers’ context and formulated with little consideration to their needs are most likely to be less effective (Murray Citation2010).

Given the challenges that respondents in this research were confronted with, in their PL, they wanted to be empowered in their PL. Profoundly, they wanted to have the freedom to choose what was important for them. An expression like ‘we (teachers) must have the freedom to determine what works best in the learning environment’ implies that respondents in this research would like to be involved in determining their PL needs but did not have the opportunity to do so. The views of teachers here are similar to Ayinselya’s (Citation2020, p. 123) finding that, often, the role of basic school teachers in Ghana in policy making is passive where they become ‘just implementers’ of policy decisions. Durrant and Holden (Citation2006, p. 91) describe it as a ‘missed opportunity’ not to have the voices of teachers in their own PL programmes and formulating appropriate ways of meeting them. Whitcomb et al. (Citation2009) also argue that PL becomes effective when improvement is placed directly in the hands of teachers themselves to determine, what Balyer et al. (Citation2017, p. 1) term as ‘empowerment’ of teachers. By empowerment, they mean trusting and having confidence in teachers to possess the capacity to decide their own learning needs. They claim further that, if empowered, teachers can discover for themselves their potentials and limitations in their PL ‘informed by their professional judgment’. This may be the reason why Smith (Citation2017, p. 19) argued that ‘professional learning is about noticing’. That is, it is about valuing and trusting that teachers possess knowledge about their PL.

Britzman (Citation2003) makes us understand that empowering teachers results in a move from a culture of reliance on a centralised system of management to a culture of autonomy, where teachers become active agents in the creation and/or transformation of their own knowledge and skills (Grimmett Citation2014). That is, when teachers are empowered in their PL, it allows them to experience a greater sense of ownership because they are managing their own career development (Bredeson and Johansson Citation2000); rather than it being seen as something that is imposed on them by authority (Beatty Citation2000). This holds the potential of encouraging teachers to try innovative ideas. Being permitted ‘to try something new is, in itself, a learning process’ which could increase ‘the depth and breadth of experience and allows teachers to expand their repertoire of teaching skills’ (Day et al. Citation2000, p. 243). This research has revealed that if teachers are empowered they could experience a greater fulfilment with their role as expert witnesses, in relation to their awareness of their own professional needs (Hansen Citation2017). However, it is important to point out that this should not simply be interpreted to mean that teachers should be left entirely alone in their PL as there could be limits on their capacity to fully take control of their learning needs. What should be done is building their capacity to play leading roles, thereby exerting a significant influence on their PL and eventually on students’ learning outcomes.

More opportunities to interact and collaborate among themselves and with parents in both formal and informal settings within and outside their school environment was another aspiration for respondents regarding empowering them. They believed that doing so would allow them to learn from one another, exchange experiences and identify their fundamental professional needs and work together towards meeting them. With this also, new and relatively inexperienced teachers would benefit from the expertise and ideas of the experienced ones as some claimed that they were able to use their experiences to ‘model’ some teacher trainees in their schools. It is argued that effective collaborations among teachers is hinged on leadership (Schein Citation2004). That is, it is necessary for school authority to support and encourage interactions and exchange of ideas among teachers. However, it is important to stress that teachers should not be forced to take part in such activities, what Hargreaves and Dawe (Citation1990, p. 227) refer to as ‘contrived collegiality’. That is, PL activities need not at all times be administratively controlled. Instead, such activities should emanate from teachers’ own understanding of their needs in order that they do not think that such activities are imposed on them. This is important because when teachers notice that their learning needs are determined for them by authority it is likely to make them feel they are incapable of initiating their own learning activities (Osborn et al. Citation2000).

Conclusion and Recommendations

It is appropriate to conclude that respondents in this research were aware of the relevance of continuous PL in their practice and hence participated in some PL activities in their schools. However, these were not enough to make respondents effective in their practice. The reasons being limited support with both material and human resources. Others were the lack of motivation for them to engage in such activities and the opportunities to determine and lead their own learning needs. This is a major concern as the findings have implications for teaching and learning in the classroom including the outcome of pupils’ learning.

The researchers, therefore, recommend the following: First, the research has shown that teachers aspire to develop their skills, knowledge and experiences in their profession. Therefore, school leaders should come up with sustainable PL activities that can stimulate both informal and formal continuous PL practices that would motivate teachers to become more engaged and hence improve teaching and learning including learning outcomes for pupils. Secondly, given that teachers wanted to be actively involved in all phases of their PL, headteachers together with the relevant policy makers in the Ghana Education Service are called upon to develop better strategies to improve PL opportunities for all teachers. The best way could be empowering them by giving teachers themselves more opportunities to determine and control their own learning activities. It is important to have confidence in teachers to lead their own learning as PL activities for teachers are likely to be sustained if teachers themselves play a pivotal role from the design through implementation to the evaluation of such activities (Smith Citation2017)Citation2009.Citation2016Citation2008Citation2010Citation1990.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ajani, O.A., 2018. Needs for in-service professional development of teachers to improve students’ academic performance in sub-Saharan Africa. Arts and Social Sciences Journal, 9 (2), 1–7.

- Alexandrou, A., 2014. Professional development meeting the aspirations and needs of individuals: what is the reality in this policy-driven era? Professional Development in Education, 40 (2), 183–189. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.887910

- Allotey-Pappoe, D., 2021, May. Continuous teacher professional development: value and expectations. Ghanaweb. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/features/Continuous-teacher-professional-development-Value-and-Expectations-1248370

- Amanortsu, G., Dzandu, M.D., and Asabere, N.Y., 2013. Towards the access to and usage of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in polytechnic education. International Journal of Computer Applications, 66 (1), 23–33.

- Archibald, S., et al., 2011. High-quality professional development for all teachers: effectively allocating resources. Washington DC: National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED520732.pdf [Accessed 29 Apr 2021].

- Asare, E.O., et al., 2012. In-Service teacher education study in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Ghana. Accra,GES: Teacher Education Division.

- Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA), 2016. In-service teacher education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Policy brief. Abidjan: ADEA Publications.

- Atta, G. and Mensah, E., 2015. Exploring teachers’ perspectives on the availability of professional development programs: a case of one district in Ghana. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5 (1), 48–59.

- Ayinselya, R.A., 2020. Teachers’ sense of professional identity in Ghana: listening to selected teachers in rural Northern Ghana. PRACTICE, 2 (2), 110–127. doi:10.1080/25783858.2020.1831736

- Balyer, A., Özcan, K., and Yildiz, A., 2017. Teacher empowerment: school administrators’ roles. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 70 (70), 1–18. doi:10.14689/ejer.2017.70.1.

- Beatty, B., 2000. Teachers leading their own professional growth: self-directed reflection and collaboration and changes in perception of self and work in secondary school teachers. Journal of In-Service Education, 26 (1), 73–97. doi:10.1080/13674580000200102.

- Beauchamp, C. and Thomas, L., 2009. Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher educations. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39 (2), 175–189. doi:10.1080/03057640902902252

- Bennell, P. and Akyeampong, K., 2007. Teacher motivation in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. London: DFID.

- Brand, B.R. and Moore, S.J., 2011. Enhancing teachers’ application of inquiry‐based strategies using a constructivist sociocultural professional development model. International Journal of Science Education, 33 (7), 889–913. doi:10.1080/09500691003739374

- Bredeson, P.V. and Johansson, O., 2000. The school principal’s role in teacher professional development. Journal of In-Service Education, 26 (2), 385–401. doi:10.1080/13674580000200114

- Britzman, D.P., 2003. Practice makes practice: a critical study of learning to teach. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Bullock A., Firmstone V., Frame J., and Thomas H., 2010. Using dentistry as a case study to examine continuing education and its impact on practice. Oxford Review of Education, 36 (1), 79–95. doi:10.1080/03054981003593548

- Carpenter, J.P. and Green, T.D., 2018. Teacher-led learning: a key part of a balanced PD diet. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development(ASCD), 14 (7). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/teacher-led-learning-a-key-part-of-a-balanced-pd-diet [Accessed 05 May 2021].

- Craft, A., 2000. Continuing professional development: a practical guide for teachers and schools. 2nd. London: The Open University.

- Darling-Hammond, L. and Richardson, N., 2009. Teacher learning: what matters? Research Review, 66 (5), 46–53.

- Day, C., et al., 2000. The life and work of teachers: international perspectives in changing times. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Day, C., 2002. School reform and transitions in teacher professionalism and identity. International Journal of Educational Research, 37 (8), 677–692. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00065-X.

- Durrant, J. and Holden, G., 2006. Teachers leading change doing research for school improvement. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

- Easton, L. B., 2008. From professional development to professional learning. The Phi Delta Kappan, 89 (10), 755–761.

- Enu, J., et al., 2018. Teachers’ ICT skills and ICT usage in the classroom: the case of basic school teachers in Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice, 9 (20), 35–38.

- Ginsburg, M., 2009. Teacher professional development: a guide to education project design based on a comprehensive literature and project review. Washington, DC: FHI 360.

- Grimmett, H., 2014. The practice of teachers’ professional development: a cultural-historical approach. The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Guskey, T.R., 2002. Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 8 (3/4), 381–391. doi:10.1080/135406002100000512

- Hammerness, K.,et al., 2007. How teachers learn and develop. In L. Darling-Hammond and J. Bransford, eds. Preparing teachers for a changing world: what teachers should learn and be able to do. San Francisco, CA: Jossy-Bass, 358–389.

- Hansen, D.T., 2017. Among school teachers: bearing witness as an orientation in educational inquiry. Educational Theory, 67 (1), 9–30. doi:10.1111/edth.12222

- Hargreaves, A. and Dawe, R., 1990. Paths of professional development: contrived collegiality, collaborative culture, and the case of peer coaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6 (3), 227–241. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(90)90015-W

- Hargreaves, A. and Fink, D., 2006. Sustainable leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Hoban, G.F., 2002. Teacher learning for educational change. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Kelani, R.R. and Khourey-Bowers, C., 2012. Professional development in sub-Saharan Africa: what have we learned in Benin? Professional Development in Education, 38 (5), 705–723. doi:10.1080/19415257.2012.670128

- Kennedy, A., 2014. Understanding continuing professional development: the need for theory to impact on policy and practice. Professional Development in Education, 40 (5), 688–697. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.955122

- Koda, G.M., 2008. Professional development for science and mathematics teachers in Tanzanian secondary schools.

- Kuuyelleh, E.N., Ansoglaenang, G., and Nkuah, J.K., 2014. Financing human resource development in the Ghana education service: prospects and challenges of the study leave with pay scheme. Journal of Education and Practice, 5 (30), 75–94.

- Lee, H.J., 2005. Developing a professional development program model based on teachers’ needs. Professional Educator, 27 (1–2), 39–49.

- Mensah, D.K.D., 2016. Teacher professional development: keys to basic school teachers’ curriculum practice success in Ghana. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research Method, 3 (2), 33–41.

- Ministry of Education and Ghana Education Service (MOE/GES), 2012. Pre-Tertiary teacher professional development and management in Ghana. policy framework. Accra, Ghana: Ministry of Education.

- Murray, J., 2010. Towards a new language of scholarship in teacher educators’ professional learning? Professional Development in Education, 36 (1/2), 197–209. doi:10.1080/19415250903457125

- National Teaching Council (NTC), 2020b. A framework for professional development of teachers: guidelines for point based-system (inset and portfolio). Accra: Ministry of Education, Ghana.

- National Teaching Council (NTC), 2020a. Education Regulatory Bodies Act, 2020, Act 1023. Accra, Ghana: Ministry of Education

- O’Sullivan, M.C., 2002. Action research and the transfer of reflective approaches to in-service education and training (INSET) for unqualified and underqualified primary teachers in Namibia. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18 (5), 523–539. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00014-8

- Opfer, V.D. and Pedder, D., 2011. Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Review of Educational Research, 81 (3), 376–407. doi:10.3102/0034654311413609

- Osborn, M., et al., 2000. What teachers do: changing policy and practice in primary education. London: Continuum.

- Peprah, O.M., 2016. ICT education in Ghana: an evaluation of challenges associated with the teaching and learning of ICT in basic schools in Atwima Nwabiagya district in Ashanti Region. European Journal of Alternative Education Studies, 1 (2), 7–27.

- Putnam, R.T. and Borko, H., 2000. What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29 (1), 4–15. doi:10.3102/0013189X029001004

- Reeve, J., 2001. Understanding motivation and emotion. 3rd. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Sachs, J. and Logan L., 1990. Control or development? A study of inservice education. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 22 (5), 473–481. doi:10.1080/0022027900220505

- Schein, E.H., 2004. Organisational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Smit, B. and Fritz, E., 2008. Understanding teacher identity from a symbolic interactionist perspectives; two ethnographic narratives. South African Journal of Education, 28, 91–101.

- Smith, K., 2017. Teachers as self-directed learners active positioning through professional learning. Singapore: Springer.

- Sorinola, O., Thistlethwaite, J., and Davies, D.A., 2013. Motivation to engage in personal development of the educator. Education for Primary Care, 24 (4), 226–229. doi:10.1080/14739879.2013.11494178

- Steward, A., 2009. Continuing your professional development in lifelong learning. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Swai, C.Z. and Glanfield, F., 2018. Teacher-led professional learning in Tanzania: perspectives of mathematics teacher leaders. Global Education Review, 5 (3), 183–195.

- Tamanja, E.M.J., 2016. Teacher professional development through sandwich programmes and absenteeism in basic schools in Ghana. Journal of Education and Practice, 7 (18), 92–108.

- Timperley, H., 2008. Teacher professional learning and development. Perth, Australia: The International Academy of Education.

- Tran, L.T. and Le, T.T.T., 2018. Teacher professional learning in international education: practice and perspectives from the vocational education and training sector. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- UNESCO, 2019. Global education monitoring report. migration, displacement and education: building bridges, not walls. Paris: UNESCO Publications.

- UNICEF, 2019. Every child learns: UNICEF education strategy 2019-2030. New York: UNICEF Publishing.

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)1989. New York: UN Publishing

- Van Schalkwyk, S., et al., 2015. Reflections on professional learning: choices, context and culture. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 46, 4–10. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.03.002

- Wallace, J. and Loughran, J., 2003. Leadership and professional development in science education: new possibilities for enhancing teacher learning. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Whitcomb, J., Borko, H., and Liston, D., 2009. Growing talent: promising professional development models and practices. Journal of Teacher Education, 60 (3), 207–212. doi:10.1177/0022487109337280