ABSTRACT

Despite a high prevalence of special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) in primary school children in Vietnam, initial teacher training (ITT) and continuous professional development (CPD) for SEND is underdeveloped and largely inaccessible. This paper reports on a UK–Vietnam collaborative project that aimed to explore the views, perceptions and experiences of primary school teachers in Vietnam regarding ITT and CPD for SEND. We present findings from an online survey with 96 primary school teachers at different stages of their careers, from a diversity of schools and locations across Vietnam. Findings draw attention to the challenges of inclusive practice and opportunities for development in this area of professional practice. A surprising finding from the analysis of qualitative open questions was the notion of professional love from teachers towards children and families. Drawing on ecological systems theory, this paper establishes an ecological model of inclusive practice for SEND in primary schools in Vietnam and makes recommendations for the development of international SEND practice more broadly.

Introduction

This paper reports on a study into inclusion, diversity and SEND in primary initial teacher training (ITT) and continuous professional development (CPD) in Vietnam. According to UNICEF (Citation2017), the number of people with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) globally lies somewhere between 180 and 220 million, this represents about 15% of the world’s population. Estimates of the number of children aged 14 years and below who have SEND range from 93 million (Unicef Citation2014) to 150 million children globally (UNICEF Citation2018).

Various studies show that the incidence of disabilities among children is significantly higher in developing countries (Clampit et al. Citation2004, Waitoller and Artiles Citation2013). Currently, statistics on children with disabilities in Vietnam are not up to date. The most recent statistics according to UNICEF (Citation2018: 3) indicate there are 2.79% of Vietnamese children aged 2–17 with disabilities, of which 2.74% are between the ages of 2–4 and 2.81% of children aged 5–17. About 2.94% of children in rural areas and 2.42% of children in urban areas, 2.62% of Kinh children and 3.48% of children of other ethnic groups have disabilities. Regarding gender, about 3.0% of boys and 2.57% of girls have disabilities. The difficulties experienced by children with disabilities are mainly hearing, vision, upper-body mobility, lower-body mobility, communication and cognition. However, only 55.5% of people with disabilities aged 5–24 who are attending school are exempted from tuition fees; schooling opportunities for children with disabilities aged 5–14 years old living in multi-dimensionally poor households are about 21% lower than that of children without disabilities (multi-dimensionally poverty includes for example living with conditions such as poor health, lack of education, inadequate living standards, disempowerment, poor quality of work, the threat of violence, and living in areas that are environmentally hazardous) The attendance rate of children with disabilities is higher in primary school (81.7%) than secondary school (67.4%) or high school (33.6%). There is some contemporary data from the Vietnamese General Statistics Office (Hai et al., Citation2020) from the first, large scale, detailed survey ‘the Vietnam Survey on People with Disabilities’ between late 2016 and early 2017. The survey covered all 63 provinces of Vietnam and included 35, 422 households with results indicating a total of 7.06% of the population (aged 2 and above) as having a disability, and within this 2.83% of children aged 2–17 (Hai et al., Citation2020). In discussing the statistics, Hai et al. (Citation2020) specify that the figures focus solely on those individuals with what can be considered moderate-to-severe learning disabilities, with those with mild disabilities, such as learning disabilities, omitted due to a lack of recognition at State-level of such conditions as a disability. Despite this high prevalence of SEND, teacher education to support inclusive practice is limited, as discussed later in this paper and illuminated in the findings from this study.

The study reported on in this paper is one of six collaborative research projects that were part of the research development and innovation strand of a wider project funded by the World Bank, ‘Enhancing Teacher Education Programme’ in Vietnam. The project involved collaboration between a group of experienced teacher education researchers from (third and fourth authors) in the UK and a group of teacher educators and post-doctoral researchers from a range of universities across Vietnam. The underpinning ethos of the programme was to create an open and collegiate space for sharing practices that recognised and valued contributions across different cultures, diverse traditions and experiences. It offered its participants the opportunity to explore these and the contributions they make to the production of knowledge and practices in teacher education in both Vietnam and the UK, addressing key challenges and areas of common interest in the professional lives of both groups of participants that emerged from collaborative discussion at the start of the programme. Methods for this study included an online survey for practising primary school teachers and in-depth interviews with a sample of the survey respondents. In this paper, we focus solely on the results of the online survey in which close to 100 primary school teachers participated.

In working towards the aim of this paper, namely to develop an ecological model of inclusive primary school practice for children with SEND in Vietnam, we have framed our literature review around some of the key issues in developing inclusive pedagogies and educational provision more widely. We begin with an overview of the international literature, before exploring more closely the context of SEND and inclusive education in Vietnam.

Inclusive practices and SEND provision in mainstream schools from international studies

Research in the area of SEND provision in mainstream schools points to challenges faced by teachers related to the responsibility placed on them to meet the individual learning needs of all students, and uncertainties around the need for special pedagogical approaches for children with SEND (Thomas and Loxley Citation2001). Rix et al.’s (Citation2009) systematic literature review raised questions from teachers regarding the lack of in-depth and practical evidence for effective pedagogical approaches to use with children with SEND. Some practical recommendations for teachers were suggested by Rix et al. (Citation2009) including: reconsidering pedagogical approaches with children with SEND in terms of a wider learning community in which all children and other practitioners are part, rather than the teacher as a sole actor. Additionally, the community learning approach should comprise flexible groupings and roles, have participation at their core, and have a teacher who is adaptable in their teaching strategies and curriculum. Added to this, Rix et al. highlight the way that the reviews support:

The importance of social engagement in enhancing the academic and social inclusion of children with special educational needs and highlight a social constructivist perspective as being significant. Teachers need opportunities to explore and reflect upon this view of learning and to develop pedagogies which use, monitor and develop pupils’ social engagement, both as an end in itself, and as a way of facilitating the development of knowledge (Rix et al. Citation2009: 94).

Such pedagogical aspects are supported by another synthesis of literature concerning the social inclusion of children with SEND in mainstream classrooms by Sheehy et al. (Citation2009: 2) that identifies five emerging themes, including: the ‘pedagogic community’; ‘social engagement’ as being ‘intrinsic to pedagogy’ and ‘the means through which student knowledge is developed’; ‘flexible modes of representing activities’ that make learning accessible to a diverse community of students; ‘progressive scaffolding of classroom activities’ and the ‘authenticity of classroom activities’. Sheehy et al. (Citation2009) emphasise an integral community aspect to teaching, with the teacher part of a wider teaching and learning community that informs a shared model of how children learn, underpinned by meaningful activities for the student, and a clear understanding by the teacher of why and how they teach particular curricula subjects.

Drawing examples of inclusive education in mainstream schools from a Portuguese context, Alves et al. (Citation2020: 281) highlight three necessary pillars for the development of inclusive educational approaches including ‘access to, participation in, and achievement in education for all children and young people’. Alves et al. (Citation2020) also critique the challenges in the development of inclusivity for children with SEND in mainstream schools: including issues of monitoring achievement at the student and system levels, and wider challenges related to investment in schools, such as learning resources and teacher education and development. Regarding the latter aspect of effective inclusive teacher education for students with SEND in mainstream schools, Robinson’s study identified that ‘where practitioner development involves critical-theoretical, reflexive, research-oriented collaborations among a professional learning community, practitioners become more confident and skilful in enacting inclusive practice’ (Citation2017: 1). Robinson (Citation2017) found that the most effective teacher development in this context was rooted within school-Higher Education partnerships as opposed to ‘on the job’ training models preferred by policy makers in England and more widely.

Whilst in the studies critiqued above, inclusive education and special education are considered together in the context of mainstream schooling, Hornby argues that they are based on different philosophies and are ‘increasingly regarded as diametrically opposed in their approaches’ (Citation2015: 237) and considers the need to be aware of their alternative views of education for children with SEND. Hornby’s study presents a theory of inclusive special education ‘that comprises a synthesis of the philosophy, values and practices of inclusive education with the interventions, strategies and procedures of special education’ (Citation2015: 238). Hornby Citation2015) concludes that the development of inclusive special education needs to make transparent the vision and guidelines for policies, procedures and teaching strategies that will facilitate the provision of effective education for all children with SEND.

Rix et al.’s (Citation2013) systematic international literature review, combined with empirical research including a detailed analysis through a survey of policy and practice in ten countries, and a series of interviews in four countries, found a lack of coherence internationally in approaches to supporting students with SEND. Rix et al.’s study foregrounds opportunities in developing this coherence including ‘a reconceptualisation of the class and the management of class resources, and the role that key personnel can play in creating links between diverse services’ (Citation2013: 1).

Vietnam SEND policy: historical context

Vietnam is guided by international legislation to ensure the right to go to school for children in general and children with disabilities in particular (Haia et. al, Citation2020; Le Citation2013) for example, the World Declaration on Education for All (1990), The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), The Dakar Framework for Action (2000), Biwako Millennium Framework for Action (Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabilities Persons 2003–2012), United Nations on the Conventions of the Rights of the Childre (UNCRC) (UNICEF, Citation2014).

Education for people with disabilities in Vietnam may be said to have started in the second half of the 19th century with the creation of a specialised school for deaf children (Hai et al., 2019). Since then, Vietnam has created a range of opportunities for children with a wide range of disabilities to receive an education. Since the 1990s, the focus has been on the adoption of inclusive education models for children with disabilities. Indeed, Hai et al. state that ‘Vietnam also is the most inclusive, in terms of the education of children and youth with disabilities, of all the Asian countries’ (2020: 257).

At a national level, The National Law on Disability (6/2010) ensures persons with disabilities have the same opportunities as other citizens. However, there is further protection of the rights of people with disabilities. For example, a Law on Children (2016) and the Education Law (2019) which protects children against bias and discrimination and provide education rights respectively.

Although Vietnam’s legal documents have paid great attention to children with SEND, there is still not enough information and implementation guidelines to ensure the above mentioned rights. The Government of Vietnam has also issued relevant legal documents. In 1995, in Decree 26/CP, the Vietnamese Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) became responsible for managing schools for disabled children. Then, in 2002, MOET established a steering committee responsible for advising the Ministry on implementing specific initiatives concerning children with disabilities in Vietnam (UNICEF Citation2017). Eight priorities were identified:

1. Continue to encourage and support school attendance by children with disabilities;

2. Investigate the educational needs of children with disabilities;

3. Plan and implement measures to foster and train special education teachers;

4. Guide and direct the provision of education for children with different kinds of disability, and unify the provision of special education teaching services across different types of schools and classes nationally;

5. Managing programme content and the evaluation of relevant books and educational materials for children with disabilities;

6. Propose policies regarding the education for children with disabilities;

7. Develop regulations on the management and direction of inclusive education; and

8. Enlisting international support for educating children with disabilities.

More recently MOET’s comprehensive January 2018 Decision 338 Education Plan for People With Disabilities (see Hai et al, Citation2020: 260) builds upon the previously cited goals and increases inclusive education targets for 2020 to:

1. Seventy percent of preschool and school-age (i.e. elementary and secondary) students with disabilities accessing quality equitable education,

2. Fifty percent of all educators and administrators having received professional learning experiences to successfully educate students with disabilities,

3. Forty percent of the 63 provinces having an operational Center for Inclusive Education Development resource centre providing schools with technical assistance and training, and

4. One hundred percent of provincial governments fully aware of and initiating implementation of national guidelines and regulations on the education for persons with disabilities

Challenges for special education in Vietnam

Lack of professional identification of disabilities, appropriate interventions, and support in the early years has hindered the chances of children with disabilities to access to education in mainstream schools. Nearly 70 per cent of primary school-age children with disabilities in Vietnam do not attend school. Most pre-primary, primary and lower secondary schools do not have appropriate facilities for children with disabilities. Teachers have not been trained to ensure inclusive teaching environment and they do not have adequate skills to identify and provide necessary interventions to address the needs of children with disabilities (Nguyen Thi Thanh Huong Citation2016). A new general education programme has been implemented. However, the development of a special education programme for children with disabilities and a supportive education programme for children with disabilities has not yet begun to develop. Only 1 in 7 teachers have been trained in teaching pupils with disabilities. Textbooks and teaching materials for children with disabilities have not been prepared simultaneously with the new general education curriculum issued in 2018. Furthermore, schools having suitable facilities and toilets for children with disabilities are only 2.9% and 9.9%, respectively (UNICEF Citation2018: 16).

Training about inclusive education and the education of children with disabilities is a critical factor in promoting career-oriented education for children with disabilities in particular (Brown, Citation2016; UNESCO, Citation2009). Teachers need to be fully conversant about the range of disabilities students may have, and about the ways in which they should adjust their teaching and the curriculum to meet the needs of children with disabilities (Brownell et al., Citation2010). A UNICEF report in 2015 addressing eight provinces in Vietnam showed that most teachers reported were not being permitted to attend training courses on inclusive education, special education, or childhood disabilities (UNICEF, Citation2015). Over two-thirds of the teachers surveyed had no access to inclusive education training and 73% of them reported that they received no help to improve their skills and abilities. In contrast, education administrators were permitted to attend inclusive education training programmes, though about one-third of them reported that they had not done so.

Hai et al (2019: 263) proposed six principles to sustain development of inclusive education in Vietnam:

Principle 1: People with disabilities are the centre of sustainable development

Principle 2: Policies supportive of inclusive education underpin inclusive practice

Principle 3: Human resource development is essential for sustainable development

Principle 4: The overall quality of school environments must be examined and improved

Principle 5: A system of support services is essential for sustainable development

Principle 6: Collaboration and coordination is needed among internal and external organisations.

Interestingly within these principles, the characteristics and skills/resources of teachers are not mentioned, although they do mention human resource development. These principles are presented by Hai et al., (2020) in a star configuration which places people with disabilities at the centre of the star. This is consistent with an ecological system approach to inclusive education.

Our theoretical framework: Ecological systems theory – making human beings human

The context (or environment) in which children grow, develop, and learn is a useful analytical framework for contextualising this paper. Children grow and develop in a social and cultural context influenced by the bi-directional interactions and relationships within and between the environments they inhabit. Their learning and development is therefore socially and culturally constructed through interactions and relationships with others in environments where meanings and languages are shared, as summarised by Bronfenbrenner (Citation2001: 6965):

Over the life course, human development takes place through processes of progressively more complex reciprocal interaction between an active, evolving bio-psychological human organism and the persons, objects, and symbols in its immediate external environments. To be effective the interactions must occur on a fairly regular basis over extended periods of time.

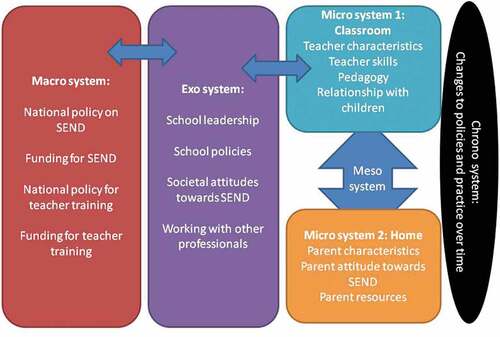

This suggests the concept of the engagement of an active child with their environment and a view that the application of inclusive education environments can improve the course and context of development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1974; Lerner, Citation2002) allowing the study of what is development to what could be development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1993). Through an examination of the characteristics of environments most proximal to a child (microsystems) and linkages between them (mesosytems) as well as those most distal (macrosystems), the environments that influence but do not directly involve the child and linkages between them (exosystems), such as a parent’s workplace over time (chronosystems) the Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) model has been utilised as a tool of analysis for the findings in this paper.

This study

Aims and questions

The project reported on in this paper explored the views and experiences of teachers in primary schools in Vietnam in relation to inclusion, diversity and special educational needs content in ITT and CPD programmes.

Research questions

What are the experiences of teachers in urban and rural primary schools of initial teacher training and continuing professional development to support inclusion, diversity and special educational needs in Vietnam?

What does SEND and inclusive practice look like in primary schools in Vietnam?

How can practicing primary school teachers be better supported in the classroom to develop more inclusive provision for children with SEND?

What should be included about inclusion, diversity and special educational needs in ALL teacher education programmes in Vietnam?

Research methods

A qualitative, interpretive approach was adopted using mixed methods of an online survey and semi-structured interviews. Using mixed methods allows for the benefits of quantitative approaches to gathering demographic contextual data whilst also drawing on individual experiences through qualitative data. An online survey was designed and circulated to primary school teachers in one area of Vietnam. The survey was designed and written in Vietnamese and answers later translated into English using project partners and online translation tools. Although online translation tools can impede the nuances of answers to complex questions, colleagues in Vietnam reflected on these and discussions with English partners were ongoing to enhance the use of online tools. The online survey was practical in view of distance and the pandemic and helpful in capturing a relatively large number of responses that were used in qualitative ways. This was strengthened with six semi-structured interviews from a small sample of survey respondents who provided consent to participate in interviews via the survey. The survey comprised a combination of closed questions related to teaching experiences as well as open questions designed to elicit more information. This paper reports on survey findings only

Ethics

Guidelines of the British Educational Research Association (BERA, Citation2018) informed day-to-day conduct and ethical standards. Approval was sought from Birmingham City University Faculty of Health, Education and Life Sciences Ethics Committee) for review of ethical issues related to the study as a whole. All data collection tools were co-written by colleagues from Vietnam and the UK and translated into Vietnamese by colleagues in Vietnam. Data were collected by colleagues in Vietnam then translated into English to allow co-analysis and co-writing for papers. The survey questions were guided by a review of the literature and previous knowledge of colleagues in Vietnam of matters of concern to teacher educators in Vietnam in relation to inclusive practice.

Participants were briefed and provided with an information sheet prior to completing the survey explaining the nature, purpose and planned dissemination of the study. Participants’ right to refuse to participate or to withdraw was explicitly stated and at all times respected. A guarantee of confidentiality was provided and anonymity maintained at all times. No links between participants and locations are made in this paper to further secure anonymity. Pseudonyms have replaced names and establishments where necessary.

All research participants were treated equally regardless of gender, colour, ethnic or national origin, (dis)ability, socio-economic background, religious or political beliefs, trades union membership, family circumstances, sexual orientation or other irrelevant distinction.

Findings

Demographics

Responses were received from 96 primary teachers (more than 91% female) from all over Vietnam, of which 71 (74%) came from public school and 25 (26%) from private school contexts. Respondents were mostly from urban and rural areas (89, more than 92%), with only a small amount from semi-rural (4, 4.2%) and mountain areas (3, 3.1%). The respondents were from a wide age range, from less than 30 to over 51 years old. 72 (75%) of respondents had trained in primary school and their teaching experience extended from less than 2 years to more than 20 years.

ITT and CPD for inclusion, diversity and SEND

Related to inclusion, diversity, and SEND, only 4 (4.2%) of respondents were trained in SEND and 14 (15%) attended related courses after their initial training. However, it was notable from the survey results that a large number of respondents appeared to not clearly understand what inclusion, diversity and SEND are as 55 (57%) affirmatively answered the question of whether they had attended additional courses related to issues of inclusion, diversity and SEND and 17 (18%) appeared to misunderstand the question regarding the diverse learning environment as their responses related to course on topics other than SEND. This may indicate a lack of proper initial training as well insufficient opportunities to attend teacher training related to these aspects.

Courses attended by participants

The courses attended by participants have been grouped together under the following categories:

Curriculum topics

Pedagogy

Teaching Standards

Inclusive/special education/diversity

Teacher wellbeing

Child development topics

Working with parents

National defence and security training (compulsory training in Vietnam)

Masters programme

The results are presented in below and have been presented in order of frequency counts with the most frequently reported first. There is some overlap between categories, for example, pedagogy and curriculum, and most participants had attended courses in more than one category:

Table 1. Summary of courses attended by survey participants.

As can be seen, the strongest category was courses related to curriculum (78 participants) followed by courses related to pedagogy (30) and teaching standards (28). Participants who had attended training for special/inclusive education/diversity were few in number (15) as were participants who had attended training related to child development (6) or working with parents (4). Interestingly, some participants (8) had attended training related to teacher wellbeing. Although the training for national defence and security is not relevant directly to teacher training, we have included it as an interesting aspect of what was reported by teachers.

Below, we discuss further aspects of the survey themes, bringing to the fore their interconnections, within our bio-ecological systems framework (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). For the purposes of analysis of this survey question, we focus particularly on the micro, meso, and macrosystems.

Support available teachers to facilitate inclusive education

With the increasing numbers of students with special educational needs (as highlighted in the review part) the teachers responded that they had faced the need to support students in diverse ways, such as: students with specific impairments (sensory, intellectual, speech, language, communication, movement); autism spectrum disorders (33.3%); Down Syndrome (14.6%); and learning difficulties (about 60%). Teachers received support from their school manager, head teacher, teacher assistant within the micro system of school, but mostly they cited support as coming from students’ parents at the meso level. However, from their point of view, only 19.8% of parents are viewed as being extremely helpful, and 15.6% as slightly indifferent to support.

The main challenges raised by teachers in terms of their own professional support included: a shortage of specific knowledge and skills (81.3%); a lack of adaptable programmes of learning (75.0%); insufficient equipment (66.7%); insufficient textbooks/reference books (59.4%); discrimination amongst students (52.1%); and time pressures to adequately prepare for teaching (51.0%) all of which are challenges that need to be addressed by national policy at the macro level.

The specific support mentioned by participants is further analysed below. It was evident from the responses that inclusive education requires a fine balance between funding at a national (macro) level, leadership from school directors and governing bodies (exo level) and clear and effective communication with and guidance/support from families at the meso level.

Macrosystem

Money/funding for resources and training (5)

Training provision (4)

Four participants mentioned the value of training in special educational needs and a further four mentioned budgetary requirements for resources and training that needed national policy support

Exosystem

Working with other professionals to support children/families (3)

Training providers (2)

Three participants mentioned working with other professionals (psychologists) and two mentioned the role of training providers in upskilling the teaching workforce:

The school has a psychologist. Many parents give their children extra emotional control classes (for hyperactive autistic children).

Mesosystem

Working with families/support from families (27)

Twenty-seven participants indicated that clear communication with families and support from parents in terms of guiding teachers and supporting children at home was crucial. There was evidence of an understanding that teachers need to work with the child’s family and apply family-centred pedagogical approaches:

Find out about family circumstances and take measures to coordinate with family and school appropriately

Should learn and be flexible in teaching, coordinate with families to educate together

Know how to coordinate with educational forces: family, school, society.

Microsystem

School leadership (23)

Care and support (3)

Twenty-three participants indicated that school leadership need to provide a conducive environment for teaching children with special educational needs and disabilities:

The school in particular, the Board of Directors of my school, is very interested in special students. However, in my teaching process, there are students I have received enthusiastic support, coordination and sympathy from parents, so that students also make good progress. However, there are parents whose understanding is still limited, or they themselves are still stigmatized and cannot accept their children’s defects, so they still put a lot of pressure on the school and teachers.

My school is a special school, so the school always creates conditions and supports for teachers and students.

Three participants mentioned the necessary care and support for teachers that must come from school leaders and governors.

Recommendations to support ITT trainee-teachers in developing an inclusive and diverse education/environment

Themes that emerged from this question included training and external support:

Macrosystem

Training (14)

There were a few comments about training for teachers that included an increase in the amount of time that teachers spent ‘in training’ as well as teachers seeking out new knowledge independently:

In my opinion, to support students and develop an inclusive and diverse environment requires a lot of both competence and ethics of teachers. Surely, when training, the University/college will also pay lots of attention. However, when studying, everything is almost theoretical, even pedagogical situations are given for students to practice, sometimes still not catching up with current reality, making new teachers when approaching reality is very confusing. Besides, as a teacher at school, the job is not only teaching and homeroom, but also includes many other jobs. Therefore, I recommend to increase the internship time at school for new teachers so that teachers have practical exposure to the environment.

Increase knowledge about special education and inclusive education …

Need to learn more courses on self-development to improve themselves beyond expertise.

Exosystem

External support (2)

A couple of participants mentioned the need for teachers to be supported by external agencies:

Need to create a comfortable mentality for teachers

Teachers need to receive more support and cooperation from the school board and parents

Microsytem

Teacher skills (2)

Teacher characteristics (33)

Relationship with students (13)

Pedagogy (14)

Teacher skills

There were a few comments related to teacher skills (as distinct from teacher characteristics) such as creativity, flexibility, perseverance, ability to develop students’ inherent capacity, need to understand psychology:

[Teachers should] have good professional skills, have the skills to ensure the good implementation of the set educational goals

Need to pay more attention to students’ feelings. Treat students equally. Flexible use of soft skills in dealing with discriminatory situations. Enhance the learning of IT skills suitable for each type of student.

Need to be supplemented with knowledge about Inclusive Education, early education for children with disabilities in the teacher training programme; have the opportunity to participate, exchange and share knowledge and skills with training institutions on education for children with disabilities

Teacher characteristics

This was a strong theme with 33 participants describing particular teacher characteristics that were important for inclusion of children with special educational needs and disabilities. The characteristics described were diverse and included patience, empathy, understanding, enthusiasm, gentle, soft, caring. This was exemplified by comments such as:

Need enthusiasm and passion for work, love, empathy and sharing

Teachers need to be patient and creative

[Teachers need] Enthusiasm, discovery, creativity

Relationship with students

This was a surprising theme that portrayed a strong emotional and empathetic stance from respondents and was demonstrated by the mention of ‘love’ for students from 13 participants as shown in the comments below:

Love students; actively learn teaching methods for each student.

Love the job, love children

Pedagogy

Comments that referred to some aspect of pedagogy were left by nearly half (42) of the participants. Comments in this theme were diverse and related to pedagogical interactions between teachers and students as well aspects of the teaching environment. There was some overlap between this theme and the theme of ‘relationship with students’:

Create a friendly environment

Create a friendly classroom environment, students love and empathize with each other

Create a friendly, sociable, equal class and help each other, say no discrimination

Teachers must regularly hone their pedagogical knowledge and skills to meet the requirements; regularly motivate and encourage students; Provide opportunities for students to help each other. Diversify teaching and learning activities to stimulate students’

Looking to the future: aspects of inclusion, diversity and SEND that should be included in initial teacher training and CPD

In our final section of the survey ‘looking to the future’, we posed an open question to participants regarding the conditions that are needed to develop an inclusive and diverse education/environment. We had 141 suggestions from participants, with some participants sharing multiple contributions and some contributions crossing multiple themes.

The themes that emerged from this question, and in brackets the number of suggestions/contributions towards the theme, are described below. As can be seen, the strongest themes were those related to financial investment, such as resources and facilities (40 contributions) and teachers, in terms of both pedagogical skills as well as personal characteristics (39 contributions). Additional prominent themes are those concerning school leadership and the school environment (30 contributions) and parental-family support (18 contributions).

Macrosystem

Policy changes (3)

Financial investment: facilities and resources (40)

Policy changes

The microsystem of the school environment was reflected also in participants expressing the need for change on a much broader scale in terms of societal attitudes, such as ‘addressing discrimination’ and making changes at policy level in order to support long-term national developments in teacher training:

Participation requires support and care from many sides: school, family, society. A general awareness needs to be developed amongst the whole of society about an inclusive and diverse educational environment.

Policies [are needed] to support children and families of children with disabilities to attend school.

Exosystem

Societal attitudes (11)

The need for societal change was mentioned by 11 participants:

Society needs to have a more open and positive view of this type of educational environment.

Microsystem

School leadership/environment (30)

Teachers: skills and characteristics (39)

School leadership: changes, environment, and investment

Future thinking in terms of the relationship of children with SEND and their school emerged in suggestions around school leadership and the school environment more generally. Two participants talked about the need for school leaders to ‘guide changes’ in practical ways to support children, teachers, and parents. A number of participants gave suggestions about what practical changes could look like for this, including accommodating smaller class sizes in order to provide more specialised support for children with SEND, and opening up more regular opportunities for school staff to access CPD activities.

Suggestions also alluded to the role of school leaders in cultivating an ‘integrative’ and ‘accepting’ environment that would in turn have a positive impact on the perspectives of parents and their relationships with the school, an environment described as:

Knowledge connection, community connection, an educational environment that meets diversity.

Create an active environment for learners, an atmosphere of mutual respect and trust. A self-exploring environment. A safe, open atmosphere. An environment that respects and encourages differences.

It is necessary for the school to organise seminars to invite parents to participate (like parent meetings) so that parents with special children will understand more about their children and have a more open and positive view, other parents no longer look discriminating, alienated from the students to integrate.

Whilst the examples above demonstrate what participants’ viewed as an investment by school leadership in human, affective dimensions, investment was also evident in material, financial terms:

More research and investment is needed to develop learning support conditions: learning materials, teaching equipment.

Suggested investments included human resources in the form of teaching assistants, and additional support staff such as medically trained staff such as pharmacists and teachers who were specialised in psychological counselling to support students who are ‘beyond the expertise of the homeroom teacher’. Investment was also considered in the form of training and CPD, as a way of ‘fostering professional knowledge’. Resources in the form of physical equipment included digital software, toys, and spatial considerations, for example ‘play places suitable for children’s wishes’, with one participant summarising as the ‘need for the right resources, the right infrastructure’.

Teachers: skills and characteristics

A key agent within the microsystem of the child and the school, and an interconnected part of the inclusive and accepting environment discussed above, is the teacher. Distinct suggestions were made regarding teachers’ skills and characteristics, with connections also made to their relationships with parents: as such merging also into the mesosystem:

Teachers need to have good professional and specialised skills, be creative and flexible, and need the companionship of parents.

It is necessary to change the teacher’s mindset, support cooperation between colleagues, create a relationship between family-school-society.

A teacher who tries alone will not have high results without everyone’s participation.

Participants referred to characteristics of ‘enthusiasm’ and ‘dedication’, as well as affective and emotional aspects of ‘love’; the latter aligned to the results in question F1 of the survey:

Need to love, empathise with children, always be enthusiastic about the profession.

Teacher’s love and understanding.

Teachers’ heart and student’s morality.

Mesosystem

Parental/family support (18)

Parental/family support

The theme of parental/family support within the mesosystem has been demonstrated so far in terms of parents’ relationship with the teachers and the school as a whole, and in terms of their role within the inclusive environment with the school. Additional suggestions were made regarding developing parents’ ‘perceptions of inclusive education’ and in their general understanding of the needs of their children and how this informs their development:

Teachers and parents must have a basic understanding of children with special needs. Can’t be vague. Raise children naturally.

Discussion

This paper reports on findings from an online survey that was responded to by 96 primary school teachers working in Vietnam during 2021. The limited diversity of respondents (mainly women) is acknowledged as a limitation. The findings have been analysed thematically using an ecological systems framework to map the findings enabling an ecological model of inclusive practice in Vietnam to be proposed as discussed below and shown in .

Macro system

At the macrosytem level the development of national policies to include children with SEND in public and private school has been welcomed by teachers and school leaders. However, this is not matched by proportionate funding that would enable and empower teachers to implement the requirements of policies and policy changes sufficiently well. This, combined with inadequate initial teacher training and continuous professional development, has resulted in a policy-to-practice divide as emphasised by one teacher who described this as an ‘invisible impact’ on teachers which she felt contributed to teacher burden. As can be seen from more than four times as many teachers attended training courses related to curriculum topics than those related to inclusive or special education/diversity and even fewer attended courses related to child development. Changes to national policy are called for by teachers in this study to address discrimination and support children and families. This lack of teacher education was described by Alves et al. (Citation2020) as a familiar challenge in the development of inclusivity for children with SEND. As noted by Robinson (Citation2017:1) teachers who receive training that involves critical-theoretical, reflexive and research-oriented training rooted in Higher Education professional learning communities are more confident and skilful in enacting inclusive practice.

Exo sytem

At the exosystem level respondents to this survey have described the negative societal attitudes and perceptions towards disability which they feel needs to be challenged at a national policy level in order to promote change. Working with other professionals is valuable but more support is needed for teachers from school boards to enable teachers to perform their roles.

Micro system

Microsystem 1 – school

The school environment is a key enabler or inhibitor of inclusive practice according to the participants in this study. School leaders and governors must ‘create the right conditions and supports for teachers and students’ including promoting an integrative and accepting environment. Teachers in this study have called for additional resources such as teaching assistants, play spaces and inclusive software as well as smaller class sizes to enable them to deliver policy initiatives with the necessary flexibility and adaptability suggested by Rix et al. (Citation2009) and Sheehy et al. (Citation2009)

Further to this more training for teachers and knowledge exchange sessions for parents are suggested by participants in this study. Most significantly though, participants emphasised the personal characteristics and skills of teachers as well as relationships with students (and families) and pedagogy as important factors in inclusive education. With regard to teacher characteristics and skills participants have stressed the importance of relational and social characteristics and skills of teachers such as ‘empathy’, ‘kindness’ and even ‘love’ echoing the concepts of professional love (Page, Citation2018) and social engagement (Rix et al. Citation2009, Sheehy et al. Citation2009). Indeed some of the pedagogical approaches mentioned have reflected relational approaches to teaching such as ‘creating a friendly, sociable, equal class’.

Microsystem 2 – home

Within the home environment parents acceptance of their child’s SEND mirrors to some extent societal attitudes, which emphasises policy-to-practice issues already mentioned earlier. This has an impact on parents’ communication and relationships with teachers at the mesosystem level and interestingly teachers have stressed the importance of guidance from and communication with parents in this study alluding to the concept of family-centred inclusive practice.

Mesosystem

At the meso-level participants have suggested that societal perceptions cause parental denial which affects school/home relationships. They have stressed the need to familiarise themselves with family patterns and practices and co-ordinate and communicate with families reinforcing the relational approach to teaching mentioned above and echoed by Rix et al. (Citation2009) and Sheehy et al. (Citation2009)

Chronosystem

Although this study did not adopt a longitudinal approach which might have provided some insight into changes over time, Bronfenbrenner (Citation2001) envisaged that the active and sustained participation of individuals within their environments directly influenced their potential and capacity for change. The role of the teacher in special and inclusive education in enacting Bronfenbrenners (Citation2001) vision of changing what is human development to what could be human development when all of the integrative nested systems work in harmony cannot be underestimated. We might therefore deduce that if teachers were well prepared with training and resources to enact inclusive education policies, then more children with SEND would reach their full potential as envisaged by Bronfenbrenner and Morris (Citation2006) in their mature biological systems model.

The principles for inclusive practice recommended by Hai et. al., 2020 are echoed by the participants in this study, however we the authors of this article note the focus from participants on relationships and ‘professional love’ (Page Citation2018) as a potential bridge for the policy to practice gap that might develop when training and resources are insufficient.

Implications for wider SEND policy and practice

In conclusion, the findings of this study urge the following recommendations for inclusive policy and practice in Vietnam

Improved ITT and CPD for teachers in SEND and inclusive practice combined with mentoring and practice-based training.

Increased representation of people with disabilities in prominent and visible positions generally and specifically in ITT and teacher CPD to reduce societal deficit perceptions of SEND.

Improved provision for children with SEND drawing on exemplars from Vietnam and international provision across the country.

At the same time enhance the provision and resources in all schools to support children with SEND to provide choice for families in the type of provision their child attends.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a larger project funded by The World Bank

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Dinh Nguyen Trang Thu

Dr Dinh Nguyen Trang Thu is a lecturer and Vice Dean of the Faculty of Special Education, Ha Noi National University of Education. Her specialized research field is elementary education and special education.

Luong Thi Thu Thuy

Dr. Lương Thị Thu Thủy is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Chemistry, Ha Noi National University of Education. Her specialised area of research is physical chemistry and she is interested in special education.

Carolyn Blackburn

Dr. Carolyn Blackburn is a Reader in Interdisciplinary Practice and Research with Families, CSPACE, Birmingham City University. She is interested in social justice, inclusion and participation.

Mary-Rose Puttick

Dr. Mary-Rose is a Research Fellow for the Institute for Community Research and Development at Wolverhampton University. Her research interests include the third sector, families from refugee backgrounds, and the practices of visual and sensory literacies

References

- Alves, I., Pinto, P.C., and Pinto, T.J., 2020. Developing inclusive education in Portugal: evidence and challenges. Prospects, 49 (3), 281–296. doi:10.1007/s11125-020-09504-y

- British Educational Research Association (BERA) (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research. 4th edn. Available at: www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Bronfenbrenner, U., 1974. Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood Child Development. 45, 1–5.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., 1993. The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In: R.H. Wozniak and K.W. Fisher, eds. Development in context: Acting and thinking in specific environments. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 3–44.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., 2001. The bioecology theory of human development. In: N.J. Smelser and P.B. Baltes eds. International encyclopedia of the social and behavioural sciences, vol. 10. Oxford: Pergamon, 6963–6970.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. and Morris, P.A., 2006. The bioecological model of human development. In: R.M. Lerner, ed. Handbook of child psychology, vol. 1, theoretical models of human development. New York: Wiley, 793–828.

- Brown, Z., 2016. Inclusive Education: Perspectives on pedagogy, policy and practice (The routledge Education Studies Series). London: Routledge.

- Brownell, M.T., et al., 2010. Special education teacher quality and preparation: Exposing foundations, constructing a new model. Exceptional children, 76, 357–377. doi:10.1177/001440291007600307

- Clampit, B., Holifield, M., and Nichols, J., 2004. Inclusion rates as impacted by the perceptions of teachers’ attitudes, SES, and district enrollment. National forum of special education, 14 (3), 1–14.

- Global Education Monitoring Report (2020), Global Education Meeting 2018 working documents https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718/PDF/373718eng.pdf.multihttps://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/more-efforts-needed-give-children-disabilities-equal-rights-education

- Hai, N.X., et al., 2020. Inclusion in Vietnam: More than a Quarter Century of Implementation. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 12 (3), 257–264.

- Haia, X.N.X., et al., 2020. Policies on inclusive education for children with disabilities in Vietnam. Merican scientific research journal for engineering, technology, and sciences, 72 (1), 162–180.

- Hornby, G., 2015. Inclusive special education: development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 42 (3), 234–256. doi:10.1111/1467-8578.12101

- Le, H.M. (2013) Opening the gates for children with disabilities an introduction to inclusive education in Vietnam aspen institute Online 2013-10-20_Le_Minh_Hang-Inclusive_Education_for_CWD_in_Vietnam-EN.pdf (aspeninstitute.org) [Accessed 01 Dec 2021]

- Lerner, R.M., 2002. Concepts and theories of human development (third edition). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Page, J., 2018. Characterising the principles of professional love in early childhood care and education. International journal of early years education, 26 (2), 125–141.

- Rix, J., et al., 2009. What pedagogical approaches can effectively include children with special educational needs in mainstream classrooms? A systematic literature review. Support for Learning, 24 (2), 86–94. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9604.2009.01404.x

- Rix, J., et al., 2013. Exploring provision for children identified with special educational needs: an international review of policy and practice. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 28 (4), 375–391. doi:10.1080/08856257.2013.812403

- Robinson, D., 2017. Effective inclusive teacher education for special educational needs and disabilities: some more thoughts on the way forward. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 164–178. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.09.007

- Sheehy, K., et al. (2009). A systematic review of whole class, subject based, pedagogies with reported outcomes for the academic and social inclusion of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream classrooms. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, UK.

- Thi Thanh Huong, N. (2016) Inclusive education resource centre in ninh thuan helps preparing children with disabilities to integrate regular school [ Online Inclusive Education Resource Centre in Ninh Thuan | UNICEF Viet Nam accessed 22.02.2022]

- Thomas, G. and Loxley, A., 2001. Deconstructing special education and constructing inclusion. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- UNESCO (2009) UNESCO Policy Brief on Early Childhood. Inclusion of Children with Disabilities: The Early Childhood Imperative. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183156

- Unicef (2014) 2013 Supply Annual Report 2013 [Online Supply Annual Report 2013 | UNICEF Supply Division accessed 05.04.2022]

- UNICEF (2015) Readiness for education of children with disabilities in eight provinces of Viet Nam 2015. https://www.unicef.org/vietnam/reports/readiness-education-children-disabilities-eight-provinces-viet-nam-2015

- UNICEF (2017) Readiness for education of children with disabilities studied in 8 provinces in Vietnam, Research within the framework of the national program signed between Unicef and the Ministry of Education and Training for the period 2012-2016. Report of Unicef, 2017. [Online Sự sãn sàng cho giáo dục trẻ khuyết tật nghiên cứu tại 8 tỉnh ở Việt Nam | Liên Hợp Quốc tại Việt Nam (un.org) accessed 05.04.2022]

- UNICEF (2018) Children with disabilities in Vietnam [Online children with disabilities survey findings.pdf (unicef.org) accessed 28.10.2021

- Waitoller, F. and Artiles, A.J., 2013. A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: a literature review and notes for a sociocultural research program. Review of educational research, 83, 319–356. doi:10.3102/0034654313483905