Abstract

In recent decades, bold steps taken by the government of Nepal to liberalise its abortion law and increase the affordability and accessibility of safe abortion and family planning have contributed to significant improvements in maternal mortality and other sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes. The Trump administration’s Global Gag Rule (GGR) – which prohibits foreign non-governmental organisations (NGOs) from receiving US global health assistance unless they certify that they will not use funding from any source to engage in service delivery, counselling, referral, or advocacy related to abortion – threatens this progress. This paper examines the impact of the GGR on civil society, NGOs, and SRH service delivery in Nepal. We conducted 205 semi-structured in-depth interviews in 2 phases (August–September 2018, and June–September 2019), and across 22 districts. Interview participants included NGO programme managers, government employees, facility managers and service providers in the NGO and private sectors, and service providers in public sector facilities. This large, two-phased study complements existing anecdotal research by capturing impacts of the GGR as they evolved over the course of a year, and by surfacing pathways through which this policy affects SRH outcomes. We found that low policy awareness and a considerable chilling effect cut across levels of the Nepali health system and exacerbated impacts caused by routine implementation of the GGR, undermining the ecology of SRH service delivery in Nepal as well as national sovereignty.

Résumé

Ces dernières décennies, les mesures courageuses prises par le Gouvernement népalais pour libéraliser la loi sur l’avortement et élargir l’accès à l’avortement sûr et la planification familiale à un coût abordable ont produit d’importantes améliorations dans la mortalité maternelle et d’autres résultats de santé sexuelle et reproductive (SSR). La « règle du bâillon mondial » (Global Gag Rule) de l’administration Trump, qui interdit aux organisations non gouvernementales (ONG) étrangères de recevoir une aide sanitaire internationale des États-Unis à moins qu’elles ne certifient qu’elles n’utiliseront pas ce financement pour entreprendre des activités de prestation de services, de conseil, d’aiguillage ou de plaidoyer relatives à l’avortement, compromet ces progrès. Cet article examine l’impact de la règle sur la société civile, les ONG et les services de SSR au Népal. Nous avons mené 205 entretiens approfondis semi-structurés en deux phases (août-septembre 2018 et juin-septembre 2019) dans 22 districts. Des responsables de programmes d’ONG, des fonctionnaires, des directeurs d’établissements de santé et des prestataires de services dans les secteurs privés et des ONG, ainsi que des prestataires de services dans les centres du secteur public ont participé aux entretiens. Cette vaste étude en deux phases complète la recherche anecdotique existante en montrant les conséquences de la règle du bâillon mondial et leur évolution sur une année, et les voies émergentes par lesquelles cette politique influe sur les résultats de SSR. Nous avons constaté que la faible connaissance de la règle du bâillon et un effet dissuasif considérable ont touché tous les niveaux du système de santé népalais et exacerbé les répercussions de la mise en œuvre systématique de la politique, minant l’écologie de la prestation de services de SSR au Népal, de même que la souveraineté nationale.

Resumen

En las últimas décadas, audaces medidas adoptadas por el gobierno de Nepal para liberalizar su ley sobre aborto y aumentar la asequibilidad y accesibilidad de los servicios de aborto seguro y de planificación familiar han contribuido a considerables mejoras en mortalidad materna y otros resultados de salud sexual y reproductiva (SSR). Estos avances corren peligro a causa de la Ley Mordaza del gobierno de Trump, que prohíbe que organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG) extranjeras reciban ayuda de EE. UU. para la salud mundial a menos que certifiquen que no utilizarán los fondos de ninguna fuente para participar en la prestación de servicios, brindar consejería, proporcionar referencias o realizar actividades de promoción y defensa con relación al aborto. Este artículo examina el impacto de la Ley Mordaza en la sociedad civil, en las ONG y en la prestación de servicios de SSR en Nepal. Realizamos 205 entrevistas a profundidad semiestructuradas, en dos fases (de agosto a septiembre de 2018 y de junio a septiembre de 2019), en 22 distritos. Las personas entrevistadas eran gestores de programas de ONG, empleados del gobierno, administradores de establecimientos de salud, y prestadores de servicios en los sectores de ONG y privado y en establecimientos de salud del sector público. Este importante estudio realizado en dos fases suplementa las investigaciones anecdóticas al capturar los impactos de la Ley Mordaza a medida que evolucionaron a lo largo de un año, así como las vías emergentes por las cuales esta política afecta los resultados de SSR. Encontramos que el escaso conocimiento de la Ley Mordaza y un considerable efecto paralizador en diferentes niveles del sistema de salud nepalés exacerbaron los impactos causados por la aplicación rutinaria de la política, socavando la ecología de la prestación de servicios de SSR en Nepal y la soberanía nacional.

Introduction

In 2002, the government of Nepal legalised abortion under certain conditions in order to reduce the country’s high maternal mortality and promote the reproductive rights of Nepali women. The move followed years of concerted advocacy by public health experts, advocates, government officials, and NGOs.Citation1 Since then, continued advocacy has led to further expansions of reproductive rights, culminating in the 2018 Safe Motherhood and Reproductive Health Rights (SMRHR) Act, which unequivocally recognises women’s and girls’ right to abortion, and requires that abortion services be offered by all government health facilities free of cost. Under the SMRHR Act, abortion is permitted upon request through 12 weeks gestational age, and up to 28 weeks in cases of rape and incest, fetal anomaly, and/or if the pregnancy poses a threat to the life or health of the woman. To date, the law remains one of the most permissive abortion laws in South Asia.Citation2

Since 2002, Nepali NGOs have worked hand-in-hand with the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), to develop a coherent system for safe abortion and post-abortion care according to evolving laws and policies.Citation3 Expanded access to safe abortion and post-abortion care, in conjunction with concerted efforts to increase access to contraception, have contributed to meaningful improvements to a host of women’s health outcomes. Nepal’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) dropped from 539 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 1995 to 239 in 2015;Citation4 use of modern contraception increased from 26% of married women in 1996 to 43% in 2016; and the national total fertility rate has steadily declined from 4.1 children per woman in 2001 to 2.3 in 2016.Citation5 However, use of modern contraceptive methods has stagnated in recent years.Citation6

The Mexico City Policy, or Global Gag Rule (GGR), which was reinstated and expanded by US President Donald Trump in January 2017,Footnote* threatens nearly two decades of progress in women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) in Nepal. In earlier iterations, the policy required foreign (meaning non-US based) NGOs to certify that they would not use funding from any source to provide information, referrals or services for abortion as a method of family planning (FP), or to advocate for the liberalisation of abortion laws, as a condition of receiving US government (USG) FP assistance. In contrast, the 2017 expanded GGR applies to nearly all of USG global health assistance, not just to FP assistance.Citation7 Foreign NGOs must choose whether to certify the policy at the outset of a new prime or sub-grant agreement, or when changes are made to an existing grant or sub-grant. NGOs that do not certify may engage in activities prohibited by the GGR but are rendered ineligible for USG global health assistance. US-based NGOs are not subject to the policy, but they must ensure that their foreign NGO sub-grantees comply.

The GGR does not apply to post-abortion care (PAC) or emergency contraception, and it allows exceptions for abortion provision, counselling and referral in cases of pregnancies resulting from rape or incest, or which endanger a woman’s life.Citation8 Additionally, the policy permits health care providers to give “passive referrals” to women seeking legal abortion when the following four conditions are met: (1) the client is pregnant; (2) she states that she has already decided to obtain a legal abortion; (3) she asks where she can receive a safe, legal, abortion; and (4) the provider believes that medical ethics in their country necessitate a response to this question.Citation8

In March 2019, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced a further expansion of the GGR (henceforth referred to as the Pompeo Expansion). Foreign NGOs that certify the GGR must now pass down the stipulations of the policy to all sub-grantees, irrespective of funding source. In other words, an NGO that is a prime recipient of USG global health assistance must now attach the GGR to sub-grants that it issues to its foreign NGO partners on non-USG-funded projects.Citation7 As a result, many foreign NGOs are forced to comply with the rule despite receiving no USG funds; and non-USG funders to whom the GGR does not apply directly, such as private foundations and multilateral agencies, could now see the policy attached to sub-grant agreements made with their funding.

The GGR is likely to affect SRH and health more broadly in Nepal for several reasons. First, a substantial amount of Nepal’s global health funding comes from the USG and is therefore subject to the policy. In 2016, the USG appropriated roughly $42 million in bilateral global health funding to Nepal.Citation9 In 2017, 65% of official development assistance received by Nepal for population policies /programs & reproductive health came from the USG.Citation10,Citation11

Second, despite a liberal abortion law and public sector support and infrastructure for safe abortion provision, barriers to legal abortion persist. These include lack of knowledge among women about the legality of abortion and where to access legal abortion services; stigma; cost of obtaining legal abortion; and lack of access to facilities that have the guidelines, equipment, commodities and staff training necessary to provide these services.Citation12,Citation13 In 2014, only 42% of the induced abortions performed in Nepal were legal.Citation14 Furthermore, the majority of legal abortions in Nepal are performed outside of the public sector.Citation14 In 2014, 34% of legal abortions were performed in NGO facilities, 37% were in public-sector facilities, and 29% were in private-sector facilities.Citation14 The GGR could exacerbate high rates of unsafe abortion in Nepal if foreign NGOs that provide, counsel on, or refer for safe, legal abortion decide to certify the policy and are thus no longer able to provide those services; or if NGOs decide not to certify the policy, lose USG funding for other activities as a result, and subsequently have to scale back operations in multiple areas, including those related to safe, legal abortion.

Third, as mandated in the Constitution adopted in 2015, the Government of Nepal has undergone a process of devolution. This includes shifting responsibility for health provision from the central government to 7 newly formed provinces, 77 districts, and 753 municipalities.Citation15 The government apparatus for providing free abortion services as well as other reproductive health services has been disrupted by devolution. The concurrence of the shift to federalism and the GGR may leave government actors with little capacity to bolster public sector abortion service provision, and may complicate civil society efforts to mitigate the harms of the policy.Citation16

Past research shows that the GGR impacts SRH service delivery and outcomes. Several large-scale quantitative studies have found associations between the 2001–2009 iteration of the GGR, reduced contraceptive use and increased induced abortions in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean.Citation17–19 GGR-driven reductions in service coverage and availability have been documented in several countries across multiple policy iterations.Citation20–25 For example, after declining to certify the policy in 2001, the organisation Marie Stopes International lost significant funding. In Nepal, the organisation subsequently closed mobile reproductive health clinics serving clients in hard-to-reach rural areas, and reduced the number of community-based volunteers providing family planning counselling and supplies.Citation26 Research on the GGR has also detected the chilling effect, a phenomenon whereby individuals and organisations over-restrict their activities in an effort to remain in compliance with the policy or regulation and/or in the good graces of an important donor. The chilling effect accompanying the GGR has resulted in unnecessary limitations on referrals and services, as well as self-censorship in coalition and advocacy spaces.Citation23,Citation27,Citation28

This paper describes a qualitative study that assesses how the Trump administration’s GGR affects sexual and reproductive health service access and provision in Nepal. This study is intended to complement existing grey literature, assessments of the GGR’s impact in Nepal that were undertaken primarily through interviews in Kathmandu, and multi-country quantitative studies from earlier iterations of the GGR that found associations between exposure to the policy and health coverage and outcome indicators, but that did not explore causal pathways.Citation17–19 To do this, the current study qualitatively assesses impact in Nepal’s seven provinces at two points in time. It elucidates pathways of impacts and includes findings that can inform harm mitigation efforts.

Methodology

Qualitative sample

The research comprised 205 semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted in two phases with NGO programme managers, government employees, NGO and private sector facility managers and SRH service providers, and public sector SRH service providers. provides a description of participant categories across the two phases.

Table 1. Summary of qualitative interviews (n = number of interviews)

We chose to conduct two phases of qualitative data collection in order to examine impacts of the GGR on the Nepali health system over the course of a year, and capture any changes in the policy’s reach and associated impacts on civil society and health facilities at two time points. The first phase of data collection occurred between August and September of 2018. We chose this time after consulting with several international NGOs who informed us that SRH programmes were beginning to be affected by the current iteration of the GGR around that time. The second phase occurred nine months later, between June and September of 2019. Not all individual participants interviewed during Phase 1 were necessarily interviewed in Phase 2, though there was significant overlap in the NGOs and facilities represented in both phases.

Site selection and participant recruitment

We conducted interviews in 22 districts across Nepal’s seven provinces. Districts selected contained high concentrations of NGOs operating global health programmes, including programmes supporting public sector facilities. provides a breakdown of the number of districts where interviews with each participant category took place. We selected all interview participants through a mix of purposive and snowball sampling.

Table 2. Number of districts represented across participant categories

Prior to data collection, the research team held round-table meetings in each provincial capital to share background on the research objectives and design. These meetings included stakeholders such as SRH service providers and facility managers from public, NGO, and private facilities; government officials; and heads and programme managers of NGOs who worked on safe abortion and/or health topics that may be funded via US global health assistance, such as: adolescent SRH, FP, HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), menstrual hygiene management, nutrition, malaria, tuberculosis, water, sanitation and hygiene (WaSH), cervical cancer, and women’s empowerment. After each meeting, we requested interviews with meeting attendees or willing representatives from their organisations. These participants then aided us in identifying other organisations working in the aforementioned health topics in an additional nine districts. Interviewers contacted representatives of these organisations and local government via email or phone to request interviews.

The study included participants from US-based NGOs and foreign NGOs, some of whom certified the GGR and some of whom did not. We chose to include US-based NGOs because the GGR applies to their foreign NGO sub-grantees on USG-funded projects; further, US-based NGOs working on safe abortion could be impacted by the GGR if their foreign NGO partners on those projects certify the GGR and subsequently halt their participation. Most of the foreign NGO interview participants were from organisations that implemented projects as sub-grantees, a few represented organisations that were prime grantees, and some represented organisations that operated as both. We do not provide a numerical breakdown or further information, in order to protect the confidentiality of the respondents and their employers.

We also identified and recruited participants from NGO and private health facilities, many of whom were affiliated with two foreign NGOs in our sample that did not certify the GGR. In Phase 1, the research team worked with NGO staff and employed snowball sampling to connect with health facility managers at 21 clinics that operated in 14 districts. Interviewers travelled to each facility and conducted 33 interviews with facility managers and service providers who delivered abortion, FP, and/or PAC services. In Phase 2, interviewers conducted 28 interviews at 22 facilities with as many of the same participants as possible.

In Phase 2 only, we identified and recruited service providers (n = 27) from government health facilities in 10 districts. All but one of these participants provided FP or abortion services at sites that had previously received support from a large-scale USAID-funded FP programme called Support for International Family Planning Organisations 2, or SIFPO2. Two foreign NGOs implemented SIFPO2, but in 2018, each had to halt implementation prematurely (three months early for one NGO and six months early for the other) because they did not certify the GGR.

and describe the NGOs represented in our sample as well as facility-level participants.

Table 3. NGOs represented across two phases of data collection

Table 4. Breakdown of facility-level interviews by facility type and data collection phase

Interview procedures

Researchers at CREHPA and Columbia University worked collaboratively to develop consent forms and semi-structured paper-based interview guides (in English and Nepali) for each of the following participant categories: NGO/government stakeholder, facility manager, and service provider. The interview guides were based on our hypothesis about health system impacts,Citation20 past research on the GGR in Nepal,Citation26,Citation29 and discussions with NGOs about their expectations and concerns. Prior to data collection, a team of nine research assistants received training on the study protocol and procedures, and pilot tested the interview guides in the field. Before each interview, research assistants provided participants with information about the study, answered participants’ questions, and obtained written and verbal consent indicating willingness to participate in an audio-recorded interview. All interviews were conducted in a private setting and in Nepali. Participants did not receive any form of compensation.

Data analysis

Interview recordings were transcribed and translated into English following the completion of each data collection phase. Two members of the CREHPA research team reviewed the transcripts to ensure that they did not contain any identifying information and to confirm the quality of the translations, and then uploaded them into Nvivo12 for coding and analysis. Four members of the study team from CREHPA and Columbia University used a hybrid of inductive and deductive approaches to develop a codebook. The team created an initial list of codes based on the questions included in the interview guides. Two CREHPA team members continued to refine the codebook iteratively by coding the same selection of five transcripts from each participant category, discussing their application of the codes, and generating new codes inductively. The coders discussed any coding inconsistencies until they reached consensus on the application and/or interpretation of the codes in question. When they developed new codes, the coders re-coded the applicable transcripts, and met to discuss and compare their application of the new code(s). Once these team members established inter-coder reliability, they divided the transcripts evenly and coded them independently. Throughout the coding process, the coders regularly met to compare and resolve questions about coding and data interpretation. After completing coding, the researchers performed a thematic content analysis and triangulated data across the two data collection phases and between affiliated NGO and facility-level participants.

This study received ethical approval from the Nepal Health Research Council, the national ethical body of Nepal (Regd. No 119 of July 27, 2018), as well as from Columbia University (AAAR6802).

Results

We start by describing participants’ knowledge of the GGR, and then describe three domains of impact: (1) on settings for civil society collaborations, (2) on organisations, and (3) on SRH service delivery.

Knowledge about Global Gag Rule

We sought to assess knowledge of the GGR among interviewees, as this was essential to determining attribution (i.e. whether it was plausible that changes interviewees noticed but did not attribute to the GGR were in fact stemming from the GGR), as well as to our understanding of NGO efforts to implement the policy and to mitigate harm stemming from the policy.

Knowledge about the GGR varied within and among categories of participants. Overall, roughly half of all participants had ever heard of the GGR. Of those who had heard of it, many could not provide a description of the policy, or demonstrated a misunderstanding of its provisions. Knowledge about the policy was greatest among NGO participants, the majority of whom had heard of the GGR and were able to provide some details about it. NGO representatives interviewed in districts outside of the capital city of Kathmandu, as well as NGO facility-based participants, were comparatively less familiar with the policy. Generally, representatives of certifying NGOs were more knowledgeable about the policy than representatives of non-certifying NGOs.

Many participants from NGOs that certified the policy learned about it through communication with their donor or prime partner on a grant, or in required policy orientations. However, some participants from certifying organisations reported that they received no information about the policy from donors or prime partners and several participants that had received orientation stated that they did not understand the policy in detail. Relatedly, a representative from an NGO explained that their organisation did not provide detailed training on the GGR to sub-recipients because they felt that it was unnecessary:

“We do not work on abortion and we also do not work with many NGOs. Due to these reasons, we don’t need to know about the policy clauses in detail … Rather than providing detailed understanding of the rule, we keep it simple and ask our colleagues not to be involved in abortion-related activities. Providing more information might not be helpful sometimes.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

When this representative was interviewed again in Phase 2, they reported that their organisation had received clarification on the policy from USAID and then passed this information to sub-recipients. The participant expressed frustration that USAID had not provided details sooner:

“Now we have prepared a document outlining where the GGR is applicable to the work of our organisation, and where it is not. USAID should have done this earlier with us … They never explained to us and we did not understand the gravity of the issue earlier.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 2)

We found that, even in Phase 2, which occurred approximately two and a half years after the policy’s reinstatement, a few participants from certifying organisations remained ignorant of the policy and its provisions. When asked about the GGR, one representative of a certifying NGO revealed that they were unaware that their organisation had signed the policy, and explained that they found their USAID contract indecipherable:

“We have a 60-page contract … We cannot understand the contract from our level … It is too thick to read or understand.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 2)

Lack of awareness or understanding of the GGR caused some certifying NGOs to plan activities that, if implemented, would violate the policy unintentionally. Participants reported three instances in which certifying NGOs made the mistake of entering into new grant agreements with non-certifying organisations to carry out safe abortion activities prohibited by the policy. When these grant agreements were discovered by their prime partners on USG-funded projects, the NGOs had already invested considerable time and effort into initiating the new projects. One participant explained that they learned about the GGR while in the process of recruiting staff for the new project:

“My organisation has been implementing USG funded projects for several years. We were accepted by another organisation to implement their abortion related program in the district. When we advertised for staff vacancy in a local printed media, the manager of the prime organisation [granting us USAID funds] issued us a strong letter saying that [we had to choose between the two projects].” (Certifying NGO representative Phase 1)

After being informed that they could not work on safe abortion–even with non-USG funds–while receiving USG funding, all three of these NGOs chose to withdraw from their funding agreements with the non-certifying organisations and preserve their larger USAID-funded projects.

The data suggest frequent over-interpretation of the policy. Comments from representatives of several certifying organisations – many of whom had received an orientation to the policy – indicated that confusion and fear of violating the policy led individuals and organisations to apply even more stringent anti-abortion restrictions than required. Common areas of misunderstanding included the policy’s provisions regarding discussion of abortion in stakeholder meetings, allowable abortion referrals, and family planning activities. Participants from both certifying and non-certifying NGOs reported that some people working within certifying NGOs believed they were forbidden to speak the word “abortion.” One extreme example of over-interpretation came from a representative of a certifying NGO, who believed that the policy barred their organisation from hiring someone who had previously had an abortion:

“Yes, it is written and we were informed as well. No office staffs, member, chairperson can be hired if they have received abortion service.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

Awareness of the GGR was particularly low among participants from the public sector. The majority of public officials interviewed did not have any knowledge about the GGR, and none of the service providers at public health facilities had heard of the policy. While a few government officials felt that the GGR would not have significant impacts on the health system in Nepal, others expressed concern upon learning about the policy. One district health official wished they had known about the policy earlier, in order to take action to mitigate its effects:

“We were unaware of the GGR policy; for this year the Ministry of Finance has already finalized the budget. If only we had known about the GGR earlier, we could have appealed for some alternatives at the central [level of government].” (Government employee, Phase 1)

Impact: splitting of spaces for SRH coordination

Interview participants from NGOs that did and did not certify the GGR reported that their participation in SRH technical groups, programme coordination meetings, trainings, and policy discussions had changed since the policy’s re-instatement. Several participants from certifying organisations described a reluctance to join meetings that would include abortion-related discussions. Some chose not to attend meetings or trainings that included abortion on the agenda, while others explained that they continued to attend, but self-censored – taking care not to speak during conversations regarding abortion. A few participants described fear that their presence or absence in these fora sent a message to other stakeholders about their compliance with the policy, and could easily be misinterpreted:

“We avoid most of the discussion sessions on abortion due to the policy. Sometimes, I show my presence for few minutes in these meetings and leave the venue. We never know in what way social media interprets our presence. Overall we stay isolated and focus on our objective.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

At the same time, participants from GGR-certifying NGOs lamented lost opportunities to coordinate activities with non-certifying NGOs. As one pointed out, these losses also undermine government priorities and directives:

“Yes, there have been changes in partnership with other partner NGOs. Before we worked together, we had discussion but now we cannot support those who advocate on safe abortion, we cannot be the part of discussion sessions. The Government suggests that we work in coordination with other partner NGOs, but we are not able to do that.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

We found several examples of how the bifurcation of participation in meetings and trainings extended to government offices and discussions. One participant from a GGR-certifying NGO explained that they self-censored in government meetings to develop national clinical guidelines and protocols, or information, education, and communication (IEC) materials, remaining silent if abortion came up. Another described feeling conflicted about attending SRH meetings convened by a District Public Health Office (DPHO) because their organisation certified the policy; again, self-censorship was perceived to be necessary in order to participate:

“The DPHO invites us to district committee sessions on SRH and we are [in a difficult position]. Being a part of Nepal government health system, we try [to be present] but do not share any word.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

Participants from a few non-certifying NGOs shared experiences in which they were excluded from government settings and collaborations that were relevant to their work as a result of over-interpretation of the GGR. In one instance, a USAID-funded programme manager incorrectly censored what a non-certifying NGO could present in a ten-minute information session for government service providers:

“About two months ago, there was a training in one of the municipalities. The DPHO had informed us that we could hold a ten-minute session after the training or before the training, as most service providers from Government health facilities would be present. The training was USAID funded. When we reached the venue, the program manager of the USG funded program told us not to talk about abortion and only to talk about family planning although our organisation works on both issues.” (Non-certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

Lastly, a participant described witnessing a recurring phenomenon whereby organisations that worked on abortion and did not certify the GGR were excluded from national policy discussions – even those that did not involve abortion. The participant attributed this shift in NGO–Government collaboration to a chilling within the Government of Nepal, possibly in the perceived interest of maintaining a high calibre bilateral relationship with USAID.

Impact: on organisations’ sustainability and partnerships

Foregoing funding opportunities

Results indicated that for both certifying and non-certifying NGOs, the GGR limited the pool of donor-funded projects for which organisations could compete. Participants from non-certifying NGOs explained that their organisations had stopped applying for large USG grants that they would otherwise have sought. Similarly, participants from certifying NGOs lamented that the policy blocked their organisations from seeking certain grants through non-USG donors. For example, an NGO working with adolescent girls to raise awareness of HIV/AIDS, sexual education, and trafficking prevention, turned down an offer to implement a safe abortion programme in order to protect their USG funding, which was a greater sum:

“We were once approached by an INGO for safe abortion program … and as we were interested to do the program, we sent an email to [USG-funded prime partner] to inform our interest on safe abortion program. As a response, we were given two options, either to choose USAID support or the safe abortion program.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 2)

Several participants pointed out that these missed opportunities for new partnerships, projects, and grants undermine the financial sustainability of NGOs, as well as their ability to provide evidence-based, comprehensive SRH care. A facility manager employed by an NGO facility that lost USAID funding support because of the GGR expressed concern about the ability of NGO facilities providing safe abortion to remain financially viable without the ability to secure funding for their work:

“Any organisation working in SRH cannot sustain only by doing abortion services. As a whole, if organisations are providing comprehensive services along with abortion like us, then they will be affected a lot.” (Facility manager, non-certifying NGO, Phase 1)

Similarly, a representative of a certifying NGO expressed frustration at having all of their funding streams impacted by just one donor:

“But it is difficult, working in this scenario. It is ok if they do not allow us to use their funds in safe abortion, but they restrict the use of non-USG fund as well … From an organisational perspective that’s not justifiable … Just because of a single donor we can miss support and opportunities from other donors. This [policy] can be problematic for organisational progress and sustainability.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

Partnership disruption

In addition to missed funding opportunities, NGO participants reported that the policy barred them from collaborating with qualified organisations to implement programmes. US-based NGOs noted that their partnerships with foreign NGOs could be affected by the policy. Representatives of several certifying NGOs talked about their newfound inability to work on SRH projects alongside partner organisations with whom they had prior working relationships and/or would like to collaborate.

A few participants suggested that limited funding and partnership opportunities caused by the GGR reduced geographic programme coverage, particularly for projects related to abortion. They described a dearth of qualified NGOs who are not bound by the GGR in some areas of the country. One participant recounted a relevant experience:

“We raised the issue that there was no organisation that worked on safe abortion in the district. We told [the district development committee] that the services need to be expanded in the district. We had also applied to X organisation for abortion-related funding. But in Trump’s policy the person or organisation that works on safe abortion cannot receive fund from the USG. The application was pending for about 5–6 months but then we decided that we would not work on it, [because] If [the donors] say we cannot work on it then we could not go ahead. We did not have any power.” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 1)

Further, as one participant from a US-based NGO that worked on SRH described, replacing partners who decided to certify the policy was an arduous process that caused project delays. This NGO lost three community partners who certified the GGR in order to maintain their USG funding. While the US-based NGO was able to replace partners in two of the districts, project activities stopped in one district.

“As a manager, I have to manage unnecessary burden in the recruitment process if such an incident [the need to replace a GGR-certifying partner organisation] takes place. This creates disturbance in our work schedule.” (US-based NGO representative, Phase 1)

Unnecessary disruptions caused by chilling/over-interpretation

Our results also indicate that over-interpretation of the GGR influenced partnerships between NGOs and health facilities. A handful of NGO participants, from certifying and non-certifying organisations, described witnessing or experiencing changes to partnerships that they attributed to a single, yet significant instance of over-interpretation by USAID and two GGR-certifying NGOs. Some of the participants who referenced this initial event were not employed by the organisations directly involved, illustrating the power of the chilling effect to reverberate throughout civil society.

The initial event reportedly occurred after providers from a network of facilities received training unrelated to SRH, organised by two GGR-certifying NGOs and paid for with USG project funds. During a series of follow-up site visits shortly after the training, the NGO monitoring team (including representatives from both NGOs that organised the training) learned that one of the participating facilities – a community hospital run by a non-certifying NGO – also provided safe abortion services and stored the equipment distributed at the training in the same area where abortion services were provided. USAID headquarters sent four individuals to Nepal to investigate the situation and found that the facility’s participation in the training was not a violation of the GGR. However, additional trainings for the facility network did not include that facility.

A representative of one of the certifying NGOs involved expressed frustration with the chilled environment engendered by this experience, and with their perceived obligation to sever their organisation’s relationship with the facility in question, even though doing so was not required by the policy. This representative went on to express concern about how the severing of this partnership would create barriers for women seeking health care for themselves and their families.

“The women in that particular community will have to travel more for the service that would have been available in [facility name],[if we continued to provide trainings and equipment].” (Certifying NGO representative, Phase 2)

Following the investigation, other actors in the NGO and private health sectors reported secondary chilling effects. One participant from a certifying NGO described increased scrutiny from a prime partner. Additionally, a private clinic was reportedly told that it could not receive safe abortion training from a non-certifying NGO and also maintain its relationship with a certifying NGO, even though it did not have grant agreements with either entity and thus was not subject to the policy.

Early impact of Pompeo Expansion on partnerships

The Pompeo Expansion was announced several months before we began our second round of interviews. Data from Phase 2 indicated that the Pompeo Expansion was beginning to affect NGO partnerships on non-USG-funded projects. Two NGO participants described receiving communications about the GGR from a prime partner who sub-granted Global Fund (a multilateral agency) funding to them. The prime partner was a foreign NGO that received USG funding as well as Global Fund funding and had therefore certified the GGR.

One of the NGO participants described receiving a letter from the Global Fund prime partner that asked for confirmation that the organisation did not conduct activities prohibited by the GGR. The second NGO participant, whose organisation did work on safe abortion, reported being told informally by the Global Fund prime partner that their organisation would soon have to choose between continuing to receive Global Fund funding and implementing safe abortion activities.

Impact: service delivery

Impacts on non-certifying organisations/facilities

Interviews with all participant categories revealed how the GGR had cascading negative effects on programme activities, health facilities, and ultimately, communities. Representatives from two non-certifying NGOs in our sample described extensive staff layoffs of project administrators and managers, health workers, and community volunteers when the policy rendered them ineligible for USG funding. One explained that their organisation was only able to retain a small number of the 250 staff across 11 districts whose salaries had previously been fully funded by the USAID project SIFPO2; the other stated that their organisation terminated 80 staff for the same reason. Relatedly, one of the NGOs was forced to close seven community FP clinics. In 2017–2018, these seven clinics provided five different planning methods, including emergency contraception, and served almost 4000 unique clients.

According to a participant from one of these NGOs, future facility closures and additional staff layoffs were expected. As one government official described, NGO funding cuts and attendant service delivery impacts harm already marginalised communities in Nepal, who have limited health care options:

“But in remote areas, women who are poor, Dalit, marginalized will be affected and most of the NGO clinics are located in the periphery where the communities are poorer. So if the funding is cut … then women in these periphery areas will be affected.” (Government employee, Phase 1)

According to multiple participants at the facility-level, outreach and community-based programming was scaled back or cut when organisations opted not to certify the GGR. These activities included those previously supported with USG funds, such as delivering information and support to mothers and other women at the community level through female community health volunteers (FCHVs), as well as NGOs’ wider activities, such as providing health information in schools and liaising with pharmacies to ensure that communities had access to medical abortion.

Impacts on referral networks

A number of NGO and facility-level participants described changes to their referral practices. Similar to the fracturing of SRH coordination spaces, our data indicate that referral networks no longer connect certifying and non-certifying entities. A handful of participants from certifying NGOs and affiliated facilities stated that they no longer provide abortion referrals to non-certifying NGO facilities, as instructed by the policy. However, interviews surfaced how the chilling effect caused referral changes beyond the requirements of the policy. For example, representatives of three GGR-certifying NGOs stated that their organisations do not make any abortion referrals – including in cases of rape or incest, or if the life of the pregnant person is in danger, which are exceptions allowed by the policy – as they feared that in doing so, they would be found to be out of compliance and stripped of USG global health funding and projects. It is unclear whether this over-interpretation was a deliberate choice made to err on the side of caution, or whether it stemmed from incomplete knowledge about the policy’s provisions.

At the same time, service providers and facility mangers interviewed in four non-certifying NGO facilities reported that they no longer receive any referrals from NGOs that certified the GGR, or from clinics affiliated with those organisations, including for FP. According to one service provider, their facility’s years-long FP referral relationship with a certifying organisation was severed without explanation:

“We have 3–4 years of referral linkage with [certifying NGO]. They used to send family planning clients to us and we used to collect their referral card in the box that they had given us. However, I am unaware of actual reason for the breakage in the referral linkage with them … It has been about a year since they referred their clients to us. We haven’t even met any representatives of [certifying NGO] after this. They haven’t even made any personal contact with us.” (Service provider, non-certifying NGO facility, Phase 2)

Relatedly, several NGO participants from organisations that certified the GGR described restricting FP and other referrals to facilities not bound by the policy. One explained that their organisation removed a non-certifying organisation from their referral pamphlets to remain compliant. Another revealed that their organisation purposefully over-restricts FP activities, and gave the impression that this was done to avoid policy-related scrutiny:

“We do not touch any part of SRH even though we are allowed to talk or refer for family planning, but we prefer not to do that.” (Certifying organisation representative, Phase 1)

Lastly, our data show that some certifying organisations and facilities did not provide passive referrals, another policy exception.Citation23 A handful of participants who understood the term incorrectly stated that the policy prohibited these referrals, while very few correctly stated that they could provide them. Notably, one NGO representative who accurately described passive referrals in their Phase 1 interview, and stated that their organisation could provide them, conceded in their Phase 2 interview, “passive referrals can be problematic to use hence we don’t [do] that,” indicating a change in confidence over time, and possible influence of the chilling effect.

Impacts on the public sector

In theory, since the GGR applies only to foreign NGO grantees, it should not impact the public sector. Our data contradict this assertion and found that the GGR affected NGOs’ ability to provide crucial support to the public sector. The most commonly discussed example of the GGR’s impact on services at public health facilities involved the early end of the aforementioned USAID-funded SIFPO2 project, a four-year US$10 million project intended to help the MoHP in Nepal achieve MDG 5Footnote† by increasing access to quality family planning.Citation30 The two NGOs implementing this project were unwilling to comply with the terms of the GGR, so the project ended three months earlier than scheduled in some districts and six months earlier than scheduled in others. The early closure unexpectedly cut off training and material support for FP services in public facilities in 22 districts, to FP mobile outreach that served 16,039 people from October to December of 2017, and to FP behaviour change communication activities in communities.

As a public sector strengthening project, SIFPO2 was meant to build FP capacity in the government health system, with all activities gradually transitioning to government control. However, several NGO and government representatives felt that the early closure of the project had a negative impact on this transition process. They mentioned that sustainability planning with the Government and the hand over process was insufficient. One government official explained that they were caught off guard by the early end of SIFPO2:

“For example, we had SIFPO2 working in coordination with us but suddenly they are about to break this coordination saying that they are out of budget and they have to turn over the programs to us, so they cannot keep up with all the activities. We have a contract with them till 2019, but 6 months early they are at wrap-up stage.” (Government employee, Phase 1)

Many participants discussed the need for the government to fill the gap in SRH services left by programmes and NGOs impacted by the GGR, as well as the weaknesses in public sector service delivery that made it difficult for the government to achieve this goal. Some government employees spoke enthusiastically about the GGR as an opportunity for the government to “take the lead” and “speed up activities” in strengthening its health services. However, others recognised that the public sector was currently unable to fully meet the need for SRH services. When asked about the impact of the GGR, one government official said:

“Government will be empowered in family planning services. When private organizations lose their support from US, the government will be obliged to be responsible and people will start to use government facilities. For that however, the service provision from the government facility is not enough, there are issues regarding the quality of infrastructure.” (Government employee, Phase 1)

In many of the districts that had received SIFPO2 support, local governments were unable to organise FP mobile outreach in 2018. These efforts – which enabled the provision of long-acting, reversible contraceptives (LARC) and permanent methods to remote populations – had been successful in previous years, and local government officials felt there was demand for them. However, many stated that, without the support of SIFPO2, they lacked the budget and capacity to conduct mobile outreach in remote areas.

In Phase 2 interviews, many participants explained that some providers lacked confidence to provide LARC services (insertion and removal of intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants) due to absence of continued, on-the-job training following the end of SIFPO2. As a result, clients were referred to another facility or asked to reschedule their visit for a time when a trained provider was available.

“Services have been affected because we do not have the confidence to provide the implant removal service alone due to lack of training. Only one provider is IUCD trained, so if she goes somewhere then the service is halted.” (Service provider, government facility, Phase 2)

Public sector participants frequently mentioned challenges associated with the recent federalisation process, which shifted responsibility for health care provision from the central government to local governments. Staff transfers related to federalisation occurred at the same time as the closure of the SIFPO2 project. Several participants explained situations in which LARC-trained providers were transferred to other districts, leaving no staff able to replace the services they had provided. In addition, federalisation was accompanied by a change in the process by which facilities requested and received FP commodities. According to many public sector providers and facility managers, these changes resulted in delays and disruptions in the FP supply chain, thus compounding the difficulties faced by former SIFPO2 sites. Participants explained that additional handover time, as provided in the original project timeline, would have enabled a smoother project transition, mitigating the local service gaps resulting from the federalisation process, rather than exacerbating them.

Discussion

Overall, results indicate that the activity prohibitions imposed by the GGR, as well as the fear it engenders, disrupt the health system in Nepal by undermining SRH coordination, NGO partnerships, referral relationships, and service provision. These negative impacts risk undoing some of the gains realised through USAID’s long-term investment and partnership with foreign NGOs and the MoHP to increase FP access and utilisation in Nepal.Citation30

Widespread lack of knowledge about the policy’s stipulations further undermines current and past investments. NGO participants in our sample often did not comprehend that the GGR restricts the ways that non-USG funding can be used. As such, many participant NGOs planned SRH partnerships that later had to be abandoned, often after time and resources were expended.

The Pompeo Expansion fragments the NGO funding ecosystem further. We found that the policy began to affect foreign NGO sub-recipients of Global Fund money, at least one of whom also worked on safe abortion, shortly after the introduction of the Pompeo Expansion. The foreign NGO that has been the Global Fund's prime recipient in Nepal since 2015 is gagged, which means that all foreign sub-recipients of Global Fund money in Nepal will be gagged, irrespective of whether they currently or have ever received US Global Health Assistance.Citation31 According to a 2019 retrospective analysis of Global Fund grants, Nepal is one of five countries that would have over 60% of their Global Fund funding restricted by the GGR were it applied to 2017 and 2018 funding levels (64.1% or $28 million).Citation32 Because our second round of data collection occurred in the months immediately following the announcement of the Pompeo Expansion, further research to document its impact in Nepal is warranted.

The GGR has weakened FP service provision and reduced access to modern contraception in Nepal, impeding progress in meeting national and international commitments to ensure equitable access to voluntary FP and improve FP method mix.Citation33,Citation34 Our data show that the early closure of the SIFPO2 project, necessitated by the GGR, led to NGO staffing losses and clinic closures, as well as reduced LARC training and FP outreach support to government facilities supported by the project. These effects were further exacerbated by the federalisation process. While we cannot say with certainty that these findings would not have occurred eventually without the GGR, we can say that they occurred at the time they did because of the GGR. Existing anecdotal evidence from Nepal corroborates our results.Citation16,Citation35

We also found disruptions to FP referral networks affecting women seeking services at both certifying and non-certifying NGO facilities. The existing evidence base on the impacts of the GGR in Nepal does not include data on FP referral.Citation16,Citation26,Citation35–37 We found that some certifying NGOs/facilities have stopped referring women seeking contraception to non-certifying facilities, and others have stopped all FP referrals, even though the GGR does not restrict FP referral. Relatedly, highly qualified SRH referral points that are not bound by the policy reported reduced client flow for FP, including from long-time partners who are now gagged.

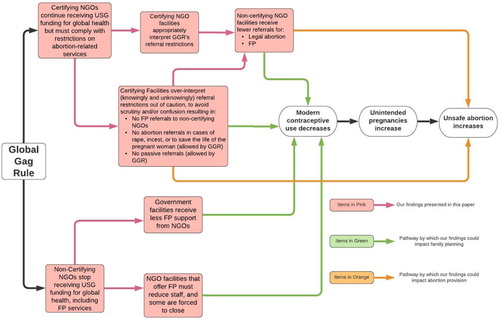

These changes will likely increase unmet need for modern contraception, which is associated with increased unintended pregnancy and negative health outcomes such as unsafe abortion and maternal mortality.Citation38,Citation39 Indeed, quantitative studies conducted to assess earlier iterations of the GGR found that the GGR was associated with decreased access to family planning and increased induced abortions in a number of countries.Citation17–19,Citation21,Citation22 Our research highlights the causal pathway by which this occurs, as shown in .

While the GGR restricts the activities of foreign NGOs, our findings shed light on avenues through which the policy also infringes upon national sovereignty at multiple levels. Research on the current and prior iterations of the GGR from Nepal and other countries shows that the GGR chilled deliberation between lawmakers and civil society related to national abortion law and policy change.Citation26,Citation27,Citation40–42 Our findings elucidate specific pathways through which the GGR permeates other activities and settings governed by the MoHP at national and district-levels, such as abortion-related information sessions for public-sector providers, and government-led health strategy and planning meetings. The barring of information and participation in these settings, via (self) censorship and the exclusion of non-certifying NGOs, reveals the potential for the GGR to stymie national priority setting, SRH service delivery and health systems strengthening in Nepal.

Relatedly, gagged NGOs and facilities expressed confusion about and reluctance to provide safe abortion referrals under the conditions allowed for by the policy. Since 2002, Nepal’s abortion law has been substantially more liberal than the abortion exceptions included in the GGR,Citation43 and in 2018, the grounds for legal abortion were extended further.Citation44 In this context, passive referral is an important mechanism for mitigating harm caused by the policy and preserving the integrity of national law. Years of peer-reviewed research in Nepal shows that women who do not know where to access safe abortion services are significantly more likely to have unsafe abortions.Citation45–47 NGO referral networks are critical for curbing this outcome, particularly given the limited availability of abortion services at public sector sites.Citation14 By restricting speech and collaboration and creating confusion about permissible activities, the GGR strips Nepal’s abortion law of its meaning and power to safeguard women’s SRHR.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Understanding that areas with greater NGO presence and NGO support to the public sector are particularly affected by the GGR, we strove to include a variety of sites by conducting interviews in select districts within each of Nepal’s seven provinces. However, our sample includes participants from 22 of 77 districts; we cannot be sure that our results represent the full range of impacts experienced by NGOs, government, and public and private sector providers working in sexual and reproductive health and other areas of global health. In addition, a few certifying NGOs refused to be interviewed which could be indicative of the chilling effect.

Throughout data collection and analysis, we encountered challenges in attributing changes reported by participants to the GGR. This was due in part to low levels of knowledge regarding the GGR among some study participants; as well as to the confluence of several US and national policies influencing SRHR service delivery in Nepal, such as the US Helms Amendment, US funding cuts to UNFPA beginning in 2017, and decentralisation of the Government of Nepal. In order to parse the various issues affecting changes in participants’ experiences and to ensure validity of our results, the research team frequently made follow-up calls to participants to clarify information captured in interviews, and compared accounts of GGR impacts across participants working in the same organisation, position, and geographic region.

Both rounds of data collection occurred within the first year of many organisations’ decisions to certify the policy or not. Moreover, as previously described, our results do not capture the full effects of the Pompeo Expansion.

Conclusion and recommendations

While US Foreign Assistance to Nepal has historically helped to improve the country’s health infrastructure, the GGR reverses strides made in the health system to improve SRH. Our research helps elucidate components of a previously hypothesised causal pathway that explains how the policy permeates civil society and health systems, ultimately influencing women’s health outcomes. We found that the policy engenders confusion and a pervasive chilling effect, as well as diminished funding and partnership opportunities. The confluence of these factors fractures SRH collaboration at multiple levels, including facility referral networks, which constricts access to FP, and safe, legal abortion care. Not only are these effects contrary to Nepali policy priorities, they undercut governmental provision of priority FP and other SRH services. Our findings underscore the need for researchers, policy makers, government officials and advocates to prioritise harm mitigation measures. Government actors at national and sub-national levels should allocate increased funding for LARC and safe abortion training and provision in public facilities to limit the extent to which the GGR exacerbates public sector weaknesses. To defuse the chilling effect, NGOs and advocates in Nepal should disseminate accurate information about the policy in lay language, tailored to actors at government, facility, and grassroots levels; and pay particular attention to educating providers and women about the passive referral exception to the GGR across the public, private, and NGO health sectors. Researchers should study the longer-term effects of the policy in Nepal, particularly for SRH clients and for NGO sub-recipients of Global Fund and other non-USG funding. Finally, US policy makers should leverage this and others’ research to permanently end this harmful policy.

Acknowledgements

The research team would like to acknowledge the hard work and dedication of the interviewers (Sarina Lama, Usha Bhandari, Dikshya Sharma, Ishwari Shrestha, Nishu Ratna Baskoti, Smriti Neupane, Alpha Puri, Hemu Khadka, Punam Shrestha), as well as the time the participants spent with our team. The team also thanks the organisations who provided interviewers with access to their facilities for interviews.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

* The expanded policy was renamed “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance.” We use “GGR” throughout the paper.

† Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 consists of two targets to improve maternal health: MDG 5A: reduce maternal mortality by three quarters between 1995 and 2015; and MDG 5B: achieve universal access to reproductive health by 2015.Citation4

References

- Shakya G, Kishore S, Bird C, et al. Abortion law reform in Nepal: women’s right to life and health. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24007-1

- Fact Sheet: Abortion in Asia [Internet]. Guttmacher Institute; 2018. [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/abortion-asia

- Samandari G, Wolf M, Basnett I, et al. Implementation of legal abortion in Nepal: a model for rapid scale-up of high-quality care. Reprod Health. 2012;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-7

- Millennium Development Goals [Internet]. UNDP Nepal. [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.np.undp.org/content/nepal/en/home/post-2015/mdgoverview.html

- Ministry of Health Nepal, New Era, ICF. Nepal demographic and health survey 2016. Ministry of Health Nepal; 2017.

- Målqvist M, Hultstrand J, Larsson M, et al. High levels of unmet need for family planning in Nepal. Sex Reprod Healthc Off J Swed Assoc Midwives. 2018;17:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.04.012

- Population Action International (PAI). The interpretation that vastly extended the harm of the global gag rule [Internet]. PAI; 2019. [cited 2020 Mar 11]. Available from: https://pai.org/data-and-maps/the-interpretation-that-vastly-extended-the-harm-of-the-global-gag-rule/

- Health and Human Services – Standard Provision. Protecting life in global health assistance [Internet]; 2017. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/sites/default/files/HHS%20Standard%20%20Provision_ProtectingLifeinGlobalAssistance_HHS_May%202017.pdf

- Kates J, Moss K. What is the scope of the Mexico City policy: assessing abortion laws in countries that receive U.S. global health assistance [Internet]. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/what-is-the-scope-of-the-mexico-city-policy-assessing-abortion-laws-in-countries-that-receive-u-s-global-health-assistance/

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Creditor reporting system (CRS) [Internet]. OECD.Stat. Available from: https://stats.oecd.org/

- Explore View U.S. Foreign Assistance on a Global Map [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://foreignassistance.gov/explore

- Wu W-J, Maru S, Regmi K, et al. Abortion care in Nepal, 15 years after legalization. Health Hum Rights. 2017;19:221–230.

- Bell SO, Zimmerman L, Choi Y, et al. Legal but limited? Abortion service availability and readiness assessment in Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33:99–106. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx149

- Puri M, Singh S, Sundaram A, et al. Abortion Incidence and unintended pregnancy in Nepal. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2016;42:197–209. doi: 10.1363/42e2116

- Chaudhary D. The decentralization, devolution and local governance practices in Nepal: the emerging challenges and concerns. J Polit Sci. 2019;19:43–64. doi: 10.3126/jps.v19i0.26698

- Population Action International. Access denied: Nepal – preliminary impacts of Trump’s expanded Global Gag Rule. PAI; 2018.

- Brooks N, Bendavid E, Miller G. USA aid policy and induced abortion in Sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of the Mexico City policy. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1046–e1053. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30267-0

- Bendavid E, Avila P, Miller G. United States aid policy and induced abortion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:873–880C. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091660

- Rodgers Y. The Global Gag Rule and women’s reproductive health: rhetoric versus reality [Internet]. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GM90DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=2OzRkvVwPB&sig=3yw1FDi0wYKb3fZEQ9Stn1ZmuhA

- Schaaf M, Maistrellis E, Thomas H, et al. ‘Protecting life in global health assistance’? Towards a framework for assessing the health systems impact of the expanded Global Gag Rule. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001786. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001786

- Jones KM. Evaluating the Mexico City policy: how US foreign policy affects fertility outcomes and child health in Ghana [Internet]. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2011. [cited 2020 Jul 24]. Report No.: 1147. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/p/fpr/ifprid/1147.html

- Jones KM. Contraceptive supply and fertility outcomes: evidence from Ghana. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2015;64:31–69. doi: 10.1086/682981

- Center for Health and Gender Equity. Prescribing chaos in global health: the Global Gag Rule from 1984–2018; 2018.

- amfAR The Foundation for AIDS Research. The effect of the expanded Mexico City policy on HIV/AIDS programming: evidence from the PEPFAR implementing partners survey [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2020 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.amfar.org/issue-brief-the-effect-of-the-expanded-mexico-city-policy/

- Giorgio M, Makumbi F, Kibira SPS, et al. Investigating the early impact of the Trump administration’s Global Gag Rule on sexual and reproductive health service delivery in Uganda. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231960

- Population Action International (PAI). Access denied: the impact of the Global Gag Rule in Nepal 2006 updates [Internet]. PAI; 2006. Available from: http://pai.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Access-Denied-The-Impact-of-the-Global-Gag-Rule-in-Nepal.pdf

- The Center for Reproductive Rights. Breaking the silence: the Global Gag Rule’s impact on unsafe abortion. The Center for Reproductive Rights; 2003.

- International Women’s Health Coalition. Crisis in care: year two impact of Trump’s Global Gag Rule [Internet]. Available from: https://iwhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/IWHC_GGR_Report_2019-WEB_single_pg.pdf

- International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF). Policy briefing: the GGR and its impacts [Internet]. IPPF; 2017. Available from: https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/2017-08/IPPF%20GGR%20Policy%20Briefing%20No.1%20-%20August%202017_3.pdf

- Fact Sheet: Family Planning Service Strengthening Program (FPSSP) [Internet]. USAID; 2015. [cited 2020 Mar 24]. Available from: https://2012-2017.usaid.gov/nepal/fact-sheets/family-planning-service-strengthening-program-fpssp

- The Global Fund Office of the Inspector General. Global fund grants in Nepal [Internet]. The Global Fund; 2019. Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/8680/oig_gf-oig-19-015_report_en.pdf?u=637278310860000000

- amfAR:: Issue Brief. The expanded Mexico City policy – implications for the global Fund. The Foundation for AIDS Research:: HIV/AIDS Research [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jan 13]. Available from: https://www.amfar.org/emcp/

- Family Planning 2020 (FP2020). Nepal FP2020 core indicator summary sheet: 2018–2019 annual progress report [Internet]; 2019. Available from: http://www.familyplanning2020.org/sites/default/files/Data-Hub/2019CI/Nepal_2019_CI_Handout.pdf

- Family Planning 2020 (FP2020), Kabita Aryal. FP2020 commitment update questionnaire 2018–2019 Nepal; 2019.

- Puri M, Wagle K, Rios V, et al. Impacts of protecting life in global health assistance policy in Nepal in its third year of implementation [Internet]. CREHPA; 2020. Available from: http://crehpa.org.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GGR-Impact_Report_May-2020.pdf

- Puri M, Wagle K, Rios V, et al. Early impacts of the expanded Global Gag Rule in Nepal [Internet]. Kathmandu: CREHPA; 2019. Available from: http://crehpa.org.np/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Report_GGR-Early-Impacts-Nepal_March-08-2019.pdf

- Rios V. Reality check: year one impact of Trump’s Global Gag Rule. International Women’s Health Coalition; 2018.

- Guttmacher Institute. Adding it up: investing in contraception and maternal and newborn health for adolescents in Kenya, 2018 [Internet]; 2018. [cited 2020 Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/adding-it-up-contraception-mnh-adolescents-kenya

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO | preventing unsafe abortion [Internet]. WHO. [cited 2020 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/unsafe_abortion/hrpwork/en/

- Center for Health and Gender Equity. A powerful force: U.S. global health assistance and reproductive health and rights in Malawi [Internet]; 2020. Available from: http://www.genderhealth.org/files/uploads/change/publications/CHANGE_A_Powerful_Force_Malawi_February_2020.pdf

- Population Action International (PAI). Access denied: Senegal – preliminary impacts of Trump’s expanded Global Gag Rule [Internet]. PAI; 2018. Available from: https://pai.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Access-Denied-Senegal.pdf

- Seevers RE. The politics of gagging: the effects of the Global Gag Rule on democratic participation and political advocacy in Peru. Brook J Int’l L. 2005;31:38.

- Thapa S. Abortion law in Nepal: the road to reform. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24006-X

- Center for Reproductive Rights. Forum for women, law and development (FWLD). Safe motherhood and reproductive health rights act [Internet]; 2018. Available from: https://reproductiverights.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Safe%20Motherhood%20and%20Reproductive%20Health%20Rights%20Act%20in%20English.pdf

- Khatri RB, Poudel S, Ghimire PR. Factors associated with unsafe abortion practices in Nepal: pooled analysis of the 2011 and 2016 Nepal demographic and health surveys. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0223385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223385

- Rogers C, Sapkota S, Paudel R, et al. Medical abortion in Nepal: a qualitative study on women’s experiences at safe abortion services and pharmacies. Reprod Health. 2019;16:105. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0755-0

- Yogi A, Prakash KC, Neupane S. Prevalence and factors associated with abortion and unsafe abortion in Nepal: a nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:376. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2011-y