Abstract

Tumor staging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) system is currently regarded as the standard for staging of patients with colorectal cancer. This system provides the strongest prognostic information for patients with early stage disease and those with advanced disease. For patients with intermediate levels of disease, it is less able to predict disease outcome. Therefore, additional prognostic markers are needed to improve the management of affected patients. Ideal markers are readily assessable on hematoxylin and eosin-stained tumor slides, and in this way are easily applicable worldwide. This review summarizes the histological features of colorectal cancer that can be used for prognostic stratification. Specifically, we refer to the different histological variants of colorectal cancer that have been identified, each of these variants carrying distinct prognostic significance. Established markers of adverse outcomes are lymphatic and venous invasion, as well as perineural invasion, but underreporting still occurs in the routine setting. Tumor budding and tumor necrosis are recent advances that may help to identify patients at high risk for recurrence. The prognostic significance of the antitumor inflammatory response has been known for quite a long time, but a lack of standardization prevented its application in routine pathology. However, scales to assess intra- and peritumoral inflammation have recently emerged, and can be expected to strengthen the prognostic significance of the pathology report.

Introduction

Tumor staging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) system is currently regarded as the standard for staging of colorectal cancer (CRC). The TNM classification provides the strongest prognostic information for patients with early stage disease and those with advanced disease. For patients with intermediate levels of disease, it is less able to predict disease outcome.Citation1

In particular, patients with tumors of the same pathologic stage may experience considerably different clinical outcomes.Citation1–Citation3 Therefore, in patients with stage II CRC (pT3–pT4, N0, M0), supplemental risk estimation is crucial, because some patients may experience outcome inferior to stage III patients. Identification of these patients is important, as they might benefit from adjuvant therapy.Citation4 Ideal histopathological prognostic markers are readily assessable on routine examination, ie, hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides. These markers could facilitate patient counseling and clinical decision making with respect to follow-up scheduling and administration of adjuvant therapy.

In this review, we summarize the value of established and novel histopathological markers for the prognostication of patients with CRC (). Data for this review were compiled using Medline/PubMed and Thomson Reuters Web of Science, assessing articles published before April 2014. Search terms included colorectal cancer, histology, outcome, and prognostic factor. Only articles published in English were considered.

Table 1 Established and novel histopathological markers for the prognostication of patients with colorectal cancer

Histopathological variants of colorectal cancer

More than 90% of CRCs are adenocarcinomas. The World Health Organization classification of carcinomas of the colon and rectum lists several distinct histomorphological variant forms with a potential impact on prognosis.Citation5

Mucinous adenocarcinoma

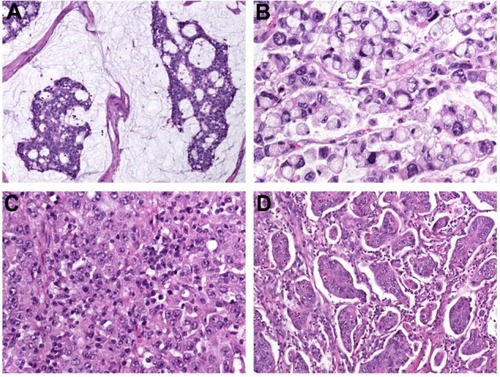

Mucinous adenocarcinoma constitutes 4%–19% of CRC worldwide.Citation6–Citation10 The designation is used when >50% of the lesion is composed of pools of extracellular mucin that contain malignant epithelium as acinar structures, layers of tumor cells, or individual tumor cells including signet ring cells (). Carcinomas with mucinous areas of <50% are categorized as having a mucinous component.Citation5

Figure 1 (A–D) Histopathological variants of colorectal cancer. (A) Mucinous adenocarcinoma characterized by abundant extracellular mucin production; (B) signet ring-cell carcinoma with prominent intracytoplasmic mucin deposition, causing displacement and molding of tumor-cell nuclei; (C) medullary carcinoma characterized by sheets of malignant cells with vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (note prominent lymphocytic infiltration of the tumor tissue); (D) micropapillary adenocarcinoma with characteristic small papillary and trabecular tumor-cell clusters within stromal spaces mimicking vascular channels.

The prognostic value of a mucinous histology in CRC remains controversial. Some studies have identified a significant association between mucinous histology and poor prognosis,Citation6,Citation9,Citation11–Citation13 while we and others could not confirm this observation.Citation10,Citation14 In a recent meta-analysis of 44 studies with a total of 222,256 patients, mucinous cancers more commonly originated from the right colon and were less frequent in male subjects. Mucinous differentiation resulted in a 2%–8% increased hazard of death, which persisted after correction for stage.Citation15

In a large cohort comprising only patients with metastatic disease, patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma showed worse overall survival, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall response rate to chemotherapy compared to patients with conventional adenocarcinoma.Citation11 Furthermore, patients with mucinous cancers were older and had larger tumor diameters, higher T classification, and increased likelihood of extrahepatic localization of metastases.Citation11

Gao et alCitation13 analyzed two independent databases and investigated the potential impact of primary tumor site on outcome. It is of interest that mucinous differentiation exhibited opposed prognostic effects depending on tumor location: mucinous histology was associated independently with poorer outcome for rectal cancer, and was an independent protective survival indicator in right-sided colon cancer. This may be due to the fact that right-sided mucinous adenocarcinomas are often microsatellite-unstable.Citation16 Although the level of maturation of the epithelium determines differentiation, grading of mucinous cancers is (if at all) done mainly by molecular analysis: mucinous cancers that show high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H) are considered low-grade, while those that are microsatellite-stable or show low-level MSI (MSI-L) are considered high-grade.Citation5,Citation15

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one study available that investigated the potential prognostic impact of a minor (<50%) mucinous component.Citation10 In this study, we hypothesized that cancers with a small amount of extracellular mucin may show differentiation arrest and behave as poorly differentiated mucinous cancers. However, no prognostic influence was seen in a retrospective analysis of 381 CRCs.

Signet ring-cell carcinoma

This variant is defined by the presence of >50% of tumor cells with prominent intracytoplasmic mucin, typically with displacement and molding of the nucleus (). Signet-ring cells can occur within pools of mucinous adenocarcinoma or in a diffusely infiltrative process with minimal extracellular mucin in a linitis plastica pattern. Carcinomas with signet ring-cell areas of <50% are categorized as adenocarcinoma with a signet ring-cell component.Citation5

Overall, about 1% of CRCs are signet ring-cell carcinomas upon histology.Citation12,Citation17–Citation19 In most studies, the prognostic value of signet ring-cell differentiation is evaluated in comparison to mucinous differentiation. Signet ring-cell carcinomas are more common on the right side, present at a higher tumor stage, and show a higher rate of lymphatic invasion and poorer differentiation.Citation18–Citation20

Signet ring-cell differentiation in CRC has been identified as an independent predictor of poor survival.Citation17–Citation19 Of note, tumors with signet ring-cell differentiation (and to a lesser extent also cancers with mucinous differentiation) have a propensity to cavitary metastatic spread with metastases to the peritoneum and ovaries. This is in contrast to conventional colorectal adenocarcinomas that metastasize predominantly to the liver and lungs.Citation21

Medullary carcinoma

This rare variant is characterized by sheets of malignant cells with vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm () exhibiting prominent infiltration by intraepithelial lymphocytes.Citation5 Medullary carcinomas arise frequently in the proximal colon, with an incidence increasing with age and a female predominance.Citation22,Citation23

Patients usually present at stage II (without nodal metastasis). Medullary differentiation is an indicator of favorable prognosis: follow-up data showed 1- and 2- year survival rates of 92.7% and 73.8%, respectively.Citation23 On the molecular level, the majority of medullary carcinomas are MSI-H cancers.Citation24

Micropapillary adenocarcinoma

Micropapillary adenocarcinoma is a rare tumor, and is defined by small papillary tumor cell clusters within stromal spaces mimicking vascular channels (). The pattern is mainly seen as a minor component of conventional adenocarcinoma.Citation5 Upon immunohistochemistry, micropapillary adenocarcinoma shows a characteristic “inside-out” staining-pattern (reversed polarity, staining pointing toward the surrounding stroma) for MUC1 (EMA) and villin.Citation25

Adenocarcinomas with a micropapillary component bear a high malignancy potential, with higher frequency of infiltrative pattern, lymphovascular and perineural invasion (PNI), deeper penetration into the bowel wall (ulcerated and/or stenosing tumors), and increased likelihood of positive lymph nodes compared to conventional adenocarcinomas. It is of note that already a small micropapillary component, such as 5%–10% of the tumor area, may significantly increase the risk of local (40%–74%) and distant (8%–16%) metastatic spread.Citation25 Lino-Silva et alCitation26 identified a micropapillary component in 10% of all colonic adenocarcinomas. Subserosal tissue invasion was present in every case, 60% was accompanied by poorly differentiated conventional adenocarcinoma, and 60% had more than four positive lymph nodes. In a study by Lee et al,Citation27 micropapillary carcinomas were characterized by more frequent lymphovascular invasion (P<0.001) and lymph-node metastasis (P<0.001) and higher T classification and TNM stage (P=0.047 and P=0.001, respectively), as well as more frequent expression of stem cell markers, such as SOX2 (P=0.038) and NOTCH3 (P=0.005). The overall 5-year survival rate for patients with micropapillary carcinoma (37%) was significantly lower than for patients with MSI-H and microsatellite-stable cancers lacking a micropapillary component (92% and 72%, P<0.001, respectively). The presence of a micropapillary carcinoma component was associated with poor survival in univariate (P<0.001) and multivariate (P=0.003, Cox hazard ratio [HR] 2.402) analyses.

Further histopathological variants

Serrated adenocarcinoma has architectural similarity to a sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, and characteristically shows glandular serration that may be accompanied by mucinous, cribriform, and trabecular areas, as well as an absence of necrosis. The neoplastic cells have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, the condensed nuclei showing preserved polarity and low nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio.Citation5,Citation28

Serrated adenocarcinoma accounts for about 7.5%–9% of all CRCs, particularly those developing through the “serrated pathway”, which is characterized by BRAF mutations, cytosine–phosphate–guanine island methylation, and subsequent low- or high-level MSI.Citation29,Citation30 Serrated morphology has been associated with poor prognosis, particularly when occurring in left-sided tumors.Citation30,Citation31 Adenosquamous carcinoma has features of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, either mixed or separate.Citation5,Citation32,Citation33 This variant has been associated with a higher rate of metastasis at the time of operation (37% versus 14% in conventional adenocarcinomas), and with high histological grade. Median overall survival time is significantly shorter compared to conventional adenocarcinoma (35.3 versus 82.4 months). In multivariate analysis, adenosquamous differentiation has been shown to be independently associated with increased overall and cancer-specific mortality.Citation33

Prognostic variables in colorectal cancer

Lymph and blood-vessel invasion

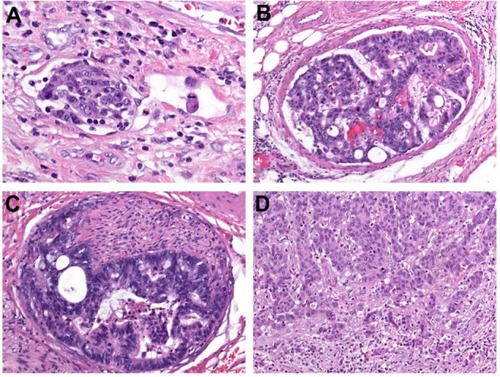

The invasion of tumor cells into lymph or blood vessels plays a crucial role in the metastatic process. Lymphatic invasion is diagnosed when tumor cells are present in vessels with an unequivocal endothelial lining, yet lacking a thick (muscular) wall (). Blood-vessel invasion refers to the involvement of veins, and is characterized histologically by the presence of tumor cells in vessels with a thick (muscular) wall or in vessels containing red blood cells (). Intramural vessel invasion, which is limited to vessels in the submucosal and/or muscular layer, has to be differentiated from extramural vessel invasion, which includes vessels located beyond the muscularis propria, ie, within the pericolic or perirectal adipose tissue.

Figure 2 (A–D) Major prognostic variables in colorectal cancer. (A) Lymphatic invasion is diagnosed when tumor cells are present in vessels with an unequivocal endothelial lining, yet lacking a thick (muscular) wall; (B) blood vessel invasion refers to the involvement of veins, and is characterized histologically by the presence of tumor cells in vessels with a thick (muscular) wall or in vessels containing red blood cells; (C) perineural invasion is defined by tumor-cell invasion of nerves and/or spread along nerve sheaths; (D) tumor budding is characterized by the presence of isolated single cells or small clusters of cells composed of less than five cells scattered in the stroma at the invasive tumor margin.

In some studies, both lymph and blood-vessel invasion have been lumped together and referred to as “lymphovascular invasion” or simply as “vascular invasion”, which is problematic, since the term “lymphovascular invasion” in other studies refers only to lymphatic invasion and the term “vascular invasion” only to venous invasion.Citation34 All pathologists are well aware of the fact that discrimination between lymphatic channels and thin-walled postcapillary venules may be difficult. For this reason, the use of the terms “small vessels” instead of lymph vessels and “large vessels” instead of blood vessels has been suggested.Citation34,Citation35

Despite these problems, both lymph and blood-vessel invasion have emerged as major prognostic variables in patients with CRC, with significance in early and advanced lesions.Citation1,Citation36,Citation37 Consequently, both the Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical PathologyCitation38 and the College of American PathologistsCitation39 emphasize the recording of vascular invasion during routine pathological work-up of cancer specimens. These bodies stress that invasion of extramural veins is an independent predictor of unfavorable outcome and increased risk of hepatic metastasis, while the significance of intramural venous (as well as lymphatic) invasion is less clear. It is of note that in the most recent College of American Pathologists’ cancer-reporting protocol,Citation39 venous invasion is not recorded separately from lymphovascular or “small vessel” invasion, which may not be appropriate, because these features confer differing prognostic information.Citation40

In our own retrospective investigation of 381 CRCs, patients with and without venous invasion had actuarial 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) rates of 30% and 75%, respectively. Regarding vessel location, 46% of patients with intramural venous invasion and 77% with extramural venous invasion died of disease progression (P<0.001). Comparable results were noted for intramural and extramural lymphatic invasion (35% versus 64%, P<0.001). In multivariate analysis, the prognostic impact of venous invasion was comparable to that of T classification, stronger than that of tumor grade and lymphatic invasion, yet inferior to that of lymph-node metastasis. When analysis was restricted to patients with AJCC/UICC stage II tumors, venous invasion proved to be the only prognostic variable with respect to both PFS (P=0.011) and CSS (P=0.006).Citation41 In node-positive tumors, lymphatic invasion can be identified in only about 50% of cases. The prognostic significance of lymphatic invasion is however limited in this subgroup: T and N classification, as well as tumor differentiation, are the major variables for prognostication, and merit special attention in patient counseling and decision making.Citation42

Venous invasion is widely believed to be an underreported finding, with significant variability in its reported incidence.Citation40 However, accurate assessment is crucial and of particular importance in stage II disease, because it may influence the decision to administer adjuvant therapy. In our study, prognostication by review pathology was superior to routine pathology, and both false-positive (mainly due to the overestimation of retraction artifacts) and false-negative diagnoses may occur.Citation41 Some authors stressed that the diagnosis of vascular involvement may be improved by applying ancillary techniques, such as Elastica van Gieson and immunostaining for cluster of differentiation (CD)31 and D2-40 for the detection of endothelial cells, as well as α-smooth-muscle actin for the detection of vessel walls.Citation35,Citation43

Perineural invasion

PNI is defined by tumor-cell invasion of nervous structures, as illustrated by neoplastic invasion of nerves and/or spread along nerve sheaths ().Citation44,Citation45 In some neoplasms, in particular pancreatic and prostate adenocarcinomas, PNI has been recognized as a characteristic histological feature.Citation5,Citation46 Its presence constitutes a process for neoplastic invasion and cancer spread independent of blood and lymphatic vessels. In the pathogenesis of PNI, neurotropic factors and matrix metalloproteinases seem to be involved.Citation45

The prognostic significance of PNI in CRC has been investigated by several groups. Liebig et alCitation46 reported fourfold-greater 5-year disease-free survival rates for patients with PNI-negative cancers compared to patients with PNI-positive cancers (65% versus 16%, P<0.001). Our own investigation brought similar results: the presence of PNI was associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype, as shown by significant associations with lymph and blood-vessel invasion, tumor-growth pattern, and budding, as well as poor tumor differentiation.Citation47 Multivariate analysis identified PNI as a prognostic variable in both tumor locations, ie, for the colon (PFS HR 3.11, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.72–5.63, P<0.001; CSS HR 3.03, 95% CI 1.51–6.05, P=0.002) and rectum (PFS HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.00–3.37, P=0.05; CSS HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.02–3.65, P=0.04) cancers.Citation47

PNI seems to have an independent influence on local tumor recurrence in rectal cancer. In a study by Peng et al,Citation48 patients with PNI-positive node-negative tumors (T3 N0) had a 2.5-fold higher 5-year local recurrence rate than PNI-negative tumors (22.7% versus 7.9%). We demonstrated that in rectal cancers with tumor-free resection margins (R0 resection), PNI was the only independent predictor of local tumor progression (HR 5.62, 95% CI 1.97–15.99; P=0.001).Citation47

Recently, Ueno et alCitation49 introduced a three-tiered grading system for PNI (no PNI, intramural PNI, extramural PNI) with 5-year disease-free survival rates of 88%, 70%, and 48%, respectively. In multivariate analysis, the site of PNI was shown to be a significant prognostic variable, independent of T and N classification. Future studies are warranted to validate these findings.

Tumor budding

Tumor budding has been defined as the presence of isolated single cells or small clusters of cells composed of fewer than five cells. These tumor buds are scattered in the stroma at the invasive tumor margin (), with a tendency to lose coherence and detach as single cells, thereby representing tumor aggressiveness.Citation50–Citation52 Biologically, tumor budding is closely related to the process of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. During this transition, epithelial cells lose intercellular and cell-matrix contacts mediated by E-cadherin, and the tumor-cell complexes dissociate, promoting invasion and ultimately metastatic cancer spread.Citation53 But cancer cells do not only lose epithelial properties during this process they may modify their epithelial phenotype by aberrant (de novo) expression of epithelial markers such as keratin 7. The term “epithelial-epithelial transition” has been suggested by our group for this hitherto unrecognized basic principle of invasion.Citation54

In several studies, tumor budding has been presented as a prognostic variable in CRC, independently predicting poor survivalCitation51,Citation55–Citation58 and high risk of recurrence.Citation59–Citation61 Nakamura et alCitation62 analyzed 200 patients with colon cancer, and identified tumor budding as the strongest independent predictor of cancer-related death, while venous and lymphatic invasion did not have independent prognostic influence.

Although budding currently appears to be the most interesting prognostic variable in CRC, it has often been criticized, because of nonstandardized criteria for evaluation and unclear reproducibility of the numerous methods for tumor-budding measurement.Citation63 Recently, Karamitopoulou et alCitation64 presented a promising 10-high-power field method for assessment of tumor budding. This method showed excellent interobserver agreement and proved independent prognostic value. According to this proposal, high-grade budding can be defined as an average of ten or more buds across 10-high-power fields, and was associated with higher tumor grade (P<0.0001), vascular invasion (P<0.0001), infiltrating tumor-border configuration (P<0.0001), higher TNM stage (P=0.0003), and reduced survival (P<0.0001). Multivariate analysis confirmed an independent prognostic effect of tumor budding (P=0.007) when adjusted for TNM stage and adjuvant therapy.Citation64

Tumor budding is of interest also in distinct subgroups of CRC. In early lesions, it appears to be one of the strongest parameters associated with the presence of regional lymph-node spread.Citation36,Citation37 In patients with AJCC/UICC stage II disease, the extent of tumor budding could be used to select patients with node-negative cancers for adjuvant therapyCitation50,Citation65–Citation67

Very recently, Rogers et alCitation68 presented data from patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant chemoradiation. In these patients, intratumoral budding assessed on pretherapeutic biopsies predicted poor pathological response to neoadjuvant treatment and poor prognosis.

In 2012, Ueno et alCitation69 proposed a new grading system for CRC based upon the quantification of “poorly differentiated clusters”. These are defined as clusters of five or more cancer cells infiltrating the stroma at the invasive tumor margin, lacking gland-like structures. Poorly differentiated clusters affected survival outcome independent of T and N classification. The prognostic value of poorly differentiated clusters was confirmed by two additional publications by the same group of authorsCitation70,Citation71 and also by another group.Citation72,Citation73

Morphologically, poorly differentiated clusters are closely related to tumor budding (the nests are slightly larger) and also to the micropapillary variant of CRC, as can easily be extracted from the images provided in the respective publication.Citation69 Future studies are needed to prove the originality of poorly differentiated clusters as a histological feature as well as a prognostic variable.

Tumor necrosis

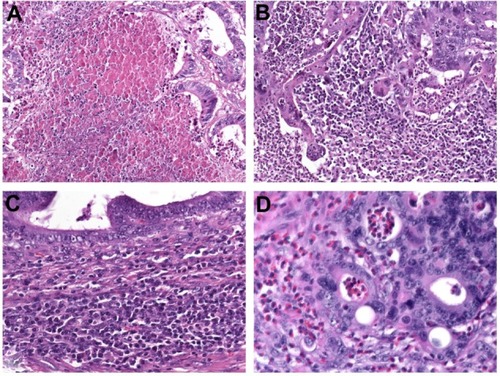

Coagulative tumor necrosis () is a common feature in multiple solid tumors, especially in lungCitation74 and renal cell carcinoma,Citation75 as well as upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma,Citation76,Citation77 but studies assessing the prognostic value of tumor necrosis in CRC are rare. Tumor necrosis is believed to be a consequence of chronic ischemic injury, due to rapid tumor growth and thereby reflecting the level of intratumoral hypoxia.Citation74,Citation76 Increased cellular hypoxia correlates with increased metastatic potential and worse prognosis, as well as resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy.Citation74–Citation77

Figure 3 (A–D) Additional prognostic variables in colorectal cancer. (A) Coagulative tumor necrosis reflecting chronic ischemic injury due to rapid tumor growth. Assessing the anti-tumoral inflammatory response is another novel prognostic tool which commonly indicates favorable outcome. (B) Marked overall inflammation at the tumor margin, characterized by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with destruction of cancer-cell islets. (C) Antitumor immune response, characterized by dense peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration; (D) Eosinophilic infiltration of the tumor area (tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia).

In our investigation, the extent of necrosis was significantly associated with T classification (P<0.001), N classification (P=0.005), TNM stage (P<0.001), poor tumor differentiation (P<0.001), large tumor size (P<0.001), and presence of blood-vessel invasion (P=0.01).Citation78 CRC patients with tumors with moderate (10%–30% of the tumor area) or extensive (>30% of the tumor area) necrosis were more likely to develop disease progression (P<0.001), and actuarial 5-year CSS rates for patients with tumors lacking necrosis and those showing focal (<10% of the tumor area) necrosis, moderate necrosis, or extensive necrosis were 93%, 74%, 60%, and 42%, respectively. Tumor necrosis was identified as an independent predictor of PFS and CSS in multivariate analysis.Citation78

Our findings were validated by other groups.Citation79–Citation81 It is of interest that Richards et alCitation79,Citation80 noted a relationship between tumor necrosis and the host systemic and local inflammatory response (intra/peritumoral inflammatory infiltrate). In a subsequent publication, the authors provided supportive evidence for the hypothesis that tumor necrosis is associated with elevated circulating interleukin (IL)-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentrations, thereby modulating both local and systemic inflammatory responses, as well as angiogenesis, which in turn may promote tumor progression and metastasis.Citation82

Inflammatory response

The antitumoral inflammatory response is a distinct histological feature and promising prognostic tool in CRC pathology. Several topics need to be addressed: the overall inflammatory response at the tumor margin, the antitumor immune response, characterized by lymphocytic infiltration, and the infiltration of the tumor stroma by eosinophils and macrophages.

The predictive value of the inflammatory cell reaction is already part of the Jass and Morson classification,Citation83 dating from 1987. Today, Klintrup’s criteriaCitation84 are widely used for scoring the intensity of inflammation at the invasive margin. This is done using a four-degree scale that takes into consideration the numbers of neutrophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes, lymphoid cells, and macrophages and their relation to the invading tumor (with or without destruction of cancer-cell islets) (). Klintrup et alCitation84 demonstrated that high-grade inflammation at the invasive margin in node-negative CRC is associated with better 5-year-survival compared to low-grade inflammation (87.6% versus 47.0%, P<0.0001). The beneficial effect of high peritumoral inflammation according to Klintrup’s criteria was confirmed in several studies.Citation79,Citation85,Citation86

Ogino et alCitation87 developed a scoring system for the antitumor immune response, based upon the evaluation of four distinct features: tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, lymphocytic infiltration of the intra- and peritumoral stroma, and Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction (). The lymphocytic antitumor immune response has been associated with an MSI-H phenotypeCitation88,Citation89 and favorable prognosis in several studies.Citation90–Citation93 Recent data suggest that specific immunotyping of the lymphocytic infiltrate (“immunoscore”) may be of additional prognostic value,Citation94,Citation95 in particular if assessed together with tumor budding.Citation96

Eosinophilic infiltration in the tumor area, which is also called tumor-associated tissue eosinophilia, is an easily assessable parameter in routine pathology (). Increased numbers of eosinophils have been favorably associated with disease recurrence and survival in patients with CRC.Citation90,Citation97,Citation98

The role of macrophages seems to be more complex, because they have been attributed both pro- and antitumor properties.Citation99 However, a high number of CD68-positive tumor-associated macrophages have been identified as a favorable morphological feature.Citation100,Citation101

Conclusion

Although tumor staging according to the AJCC/UICC TNM system is currently regarded as the standard for staging of patients with CRC, this system seems not to be suitable to predict outcome in patients with intermediate levels of disease. Ideal prognostic markers are readily assessable on hematoxylin and eosin-stained tumor slides, and are in this way easily applicable worldwide. Markers that can be used to identify patients at high risk for recurrence who might benefit from adjuvant therapy include distinct histological variants, in particular signet ring-cell carcinoma and micropapillary adenocarcinoma, but also lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, perineural invasion, and a high degree of tumor budding and tumor necrosis. Markers that have been associated with favorable outcome include the medullary variant of CRC, a high degree of antitumor host response (overall inflammation at the invasion margin, lymphocytic infiltration, and tumor-associated eosinophils), as well as the documented absence of markers indicating poor outcome. Currently, many of these markers are underreported, but pathologists need to address them in their routine reports, as they may be used for prognostication of affected individuals and are relevant for clinical decision making in the multidisciplinary team.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ComptonCCOptimal pathologic staging: defining stage II diseaseClin Cancer Res20071322 Pt 26862s6870s18006791

- McLeodHLMurrayGITumour markers of prognosis in colorectal cancerBr J Cancer19997921912039888457

- LyallMSDundasSRCurranSMurrayGIProfiling markers of prognosis in colorectal cancerClin Cancer Res20061241184119116489072

- O’ConnellJBMaggardMAKoCYColon cancer survival rates with the new American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition stagingJ Natl Cancer Inst200496191420142515467030

- HamiltonSRBosmanFTBoffettaPCarcinoma of the colon and rectumBosmanFTCarneiroFHrubanRHTheiseNDWHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System4th edLyonIARC2010134146

- DuWMahJTLeeJSankilaRSankaranarayananRChiaKSIncidence and survival of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colorectum: a population-based study from an Asian countryDis Colon Rectum2004471788514719155

- StewartSLWikeJMKatoILewisDRMichaudFA population-based study of colorectal cancer histology in the United States, 1998–2001Cancer2006107Suppl 51128114116802325

- XieLVilleneuvePJShawASurvival of patients diagnosed with either colorectal mucinous or non-mucinous adenocarcinoma: a population-based study in CanadaInt J Oncol20093441109111519287969

- ChewMHYeoSANgZPCritical analysis of mucin and signet ring cell as prognostic factors in an Asian population of 2,764 sporadic colorectal cancersInt J Colorect Dis2010251012211229

- LangnerCHarbaumLPollheimerMJMucinous differentiation in colorectal cancer – indicator of poor prognosis?Histopathology20126071060107222348346

- MekenkampLJHeesterbeekKJKoopmanMMucinous adenocarcinomas: poor prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancerEur J Cancer201248450150922226571

- HyngstromJRHuCYXingYClinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the National Cancer Data BaseAnn Surg Oncol20121992814282122476818

- GaoPSongYXXuYYDoes the prognosis of colorectal mucinous carcinoma depend upon the primary tumour site? Results from two independent databasesHistopathology201363560361523991632

- ComptonCFenoglio-PreiserCMPettigrewNFieldingLPAmerican Joint Committee on Cancer Prognostic Factors Consensus Conference: Colorectal Working GroupCancer20008871739175710738234

- VerhulstJFerdinandeLDemetterPCeelenWMucinous subtype as prognostic factor in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Clin Pathol201265538138822259177

- MinooPZlobecIPetersonMTerraccianoLLugliACharacterization of rectal, proximal and distal colon cancers based on clinicopathological, molecular and protein profilesInt J Oncol201037370771820664940

- KangHO’ConnellJBMaggardMASackJKoCYA 10-year outcomes evaluation of mucinous and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectumDis Colon Rectum20054861161116815868237

- NitscheUZimmermannASpäthCMucinous and signet-ring cell colorectal cancers differ from classical adenocarcinomas in tumor biology and prognosisAnn Surg20132585775782 discussion 782–78323989057

- ThotaRFangXSubbiahSClinicopathological features and survival outcomes of primary signet ring cell and mucinous adenocarcinoma of colon: retrospective analysis of VACCR databaseJ Gastrointest Oncol201451182424490039

- SungCOSeoJWKimKMDoIGKimSWParkCKClinical significance of signet-ring cells in colorectal mucinous adenocarcinomaMod Pathol200821121533154118849918

- PandeRSungaALeveaCSignificance of signet-ring cells in patients with colorectal cancerDis Colon Rectum2008511505518030531

- WickMRVitskyJLRitterJHSwansonPEMillsSESporadic medullary carcinoma of the colon: a clinicopathologic comparison with nonhereditary poorly differentiated enteric-type adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine colorectal carcinomaAm J Clin Pathol20051231566515762280

- ThirunavukarasuPSathaiahMSinglaSMedullary carcinoma of the large intestine: a population based analysisInt J Oncol201037490190720811712

- ChettyRGastrointestinal cancers accompanied by a dense lymphoid component: an overview with special reference to gastric and colonic medullary and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomasJ Clin Pathol201265121062106522918886

- VerdúMRománRCalvoMClinicopathological and molecular characterization of colorectal micropapillary carcinomaMod Pathol201124572973821336262

- Lino-SilvaLSSalcedo-HernándezRACaro-SánchezCHColonic micropapillary carcinoma, a recently recognized subtype associated with histological adverse factors: clinicopathological analysis of 15 casesColorectal Dis2012149e567e57222390187

- LeeHJEomDWKangGHColorectal micropapillary carcinomas are associated with poor prognosis and enriched in markers of stem cellsMod Pathol20132681123113123060121

- TuppurainenKMäkinenJMJunttilaOMorphology and microsatellite instability in sporadic serrated and non-serrated colorectal cancerJ Pathol2005207328529416177963

- MäkinenMJColorectal serrated adenocarcinomaHistopathology200750113115017204027

- García-SolanoJPérez-GuillermoMConesa-ZamoraPClinicopathologic study of 85 colorectal serrated adenocarcinomas: further insights into the full recognition of a new subset of colorectal carcinomaHum Pathol201041101359136820594582

- ShidaYFujimoriTTanakaHClinicopathological features of serrated adenocarcinoma defined by Mäkinen in Dukes’ B colorectal carcinomaPathobiology201279416917422433973

- PetrelliNJValleAAWeberTKRodriguez-BigasMAdenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectumDis Colon Rectum19963911126512688918436

- MasoomiHZiogasALinBSPopulation-based evaluation of adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectumDis Colon Rectum201255550951422513428

- BetgeJLangnerCVascular invasion, perineural invasion, and tumour budding: predictors of outcome in colorectal cancerActa Gastroenterol Belg201174451652922319961

- van WykHCRoxburghCSHorganPGThe detection and role of lymphatic and blood vessel invasion in predicting survival in patients with node negative operable primary colorectal cancerCrit Rev Oncol Hematol2014901779024332522

- BeatonCTwineCPWilliamsGLSystematic review and meta-analysis of histopathological factors influencing the risk of lymph node metastasis in early colorectal cancerColorectal Dis201315778879723331927

- BoschSLTeerenstraSde WiltJHPredicting lymph node metastasis in pT1 colorectal cancer: a systematic review of risk factors providing rationale for therapy decisionsEndoscopy2013451082783423884793

- JassJRO’BrienJRiddellRHRecommendations for the reporting of surgically resected specimens of colorectal carcinoma: Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical PathologyAm J Clin Pathol20081291132318089485

- WashingtonMKBerlinJBrantonPProtocol for the examination of specimens from patients with primary carcinoma of the colon and rectumArch Pathol Lab Med2009133101539155119792043

- MessengerDEDrimanDKKirschRDevelopments in the assessment of venous invasion in colorectal cancer: implications for future practice and patient outcomeHum Pathol201243796597322406362

- BetgeJPollheimerMJLindtnerRAIntramural and extramural vascular invasion in colorectal cancer: prognostic significance and quality of pathology reportingCancer2012118362863821751188

- BetgeJSchneiderNIPollheimerMJIs there a rationale to record lymphatic invasion in node-positive colorectal cancer?J Clin Pathol201265984785022569541

- HarrisEILewinDNWangHLLymphovascular invasion in colorectal cancer: an interobserver variability studyAm J Surg Pathol200832121816182118779725

- BatsakisJGNerves and neurotropic carcinomasAnn Otoln Rhinol Laryngol1985944 Pt 1426427

- LiebigCAyalaGWilksJABergerDHAlboDPerineural invasion in cancer: a review of the literatureCancer2009115153379339119484787

- LiebigCAyalaGWilksJPerineural invasion is an independent predictor of outcome in colorectal cancerJ Clin Oncol200927315131513719738119

- PoeschlEMPollheimerMJKornpratPPerineural invasion: correlation with aggressive phenotype and independent prognostic variable in both colon and rectum cancerJ Clin Oncol20102821e358e360 author reply e361–e36220385977

- PengJShengWHuangDPerineural invasion in pT3N0 rectal cancer: the incidence and its prognostic effectCancer201111771415142121425141

- UenoHShirouzuKEishiYCharacterization of perineural invasion as a component of colorectal cancer stagingAm J Surg Pathol201337101542154924025524

- HaseKShatneyCJohnsonDTrollopeMVierraMPrognostic value of tumor “budding” in patients with colorectal cancerDis Colon Rectum19933676276358348847

- UenoHMurphyJJassJRMochizukiHTalbotICTumour ‘budding’ as an index to estimate the potential of aggressiveness in rectal cancerHistopathology200240212713211952856

- UenoHMochizukiHHashiguchiYRisk factors for an adverse outcome in early invasive colorectal carcinomaGastroenterology2004127238539415300569

- LugliAKaramitopoulouEZlobecITumour budding: a promising parameter in colorectal cancerBr J Cancer2012106111713171722531633

- HarbaumLPollheimerMJKornpratPLindtnerRASchlemmerARehakPLangnerCKeratin 7 expression in colorectal cancer–freak of nature or significant finding?Histopathology201159222523421884201

- OkuyamaTNakamuraTYamaguchiMBudding is useful to select high-risk patients in stage II well-differentiated or moderately differentiated colon adenocarcinomaDis Colon Rectum200346101400140614530682

- UenoHPriceABWilkinsonKHJassJRMochizukiHTalbotICA new prognostic staging system for rectal cancerAnn Surg2004240583283915492565

- KanazawaHMitomiHNishiyamaYTumour budding at invasive margins and outcome in colorectal cancerColorectal Dis2008101414718078460

- ZlobecITerraccianoLTornilloLRole of RHAMM within the hierarchy of well-established prognostic factors in colorectal cancerGut200857101413141918436576

- ParkKJChoiHJRohMSKwonHCKimCIntensity of tumor budding and its prognostic implications in invasive colon carcinomaDis Colon Rectum20054881597160215937624

- ChoiHJParkKJShinJSRohMSKwonHCLeeHSTumor budding as a prognostic marker in stage-III rectal carcinomaInt J Colorectal Dis200722886386817216219

- OhtsukiKKoyamaFTamuraTPrognostic value of immunohistochemical analysis of tumor budding in colorectal carcinomaAnticancer Res2008283B1831183618630467

- NakamuraTMitomiHKanazawaHOhkuraYWatanabeMTumor budding as an index to identify high-risk patients with stage II colon cancerDis Colon Rectum200851556857218286339

- QuirkePRisioMLambertRvon KarsaLViethMQuality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis – European recommendationsVirchows Arch2011458111921061133

- KaramitopoulouEZlobecIKölzerVProposal for a 10-high-power-fields scoring method for the assessment of tumor budding in colorectal cancerMod Pathol201326229530123018875

- BetgeJKornpratPPollheimerMJTumor budding is an independent predictor of outcome in AJCC/UICC stage II colorectal cancerAnn Surg Oncol201219123706371222669453

- MitrovicBSchaefferDFRiddellRHKirschRTumor budding in colorectal carcinoma: time to take noticeMod Pathol201225101315132522790014

- HorcicMKoelzerVHKaramitopoulouETumor budding score based on 10 high-power fields is a promising basis for a standardized prognostic scoring system in stage II colorectal cancerHum Pathol201344569770523159156

- RogersACGibbonsDHanlyAMPrognostic significance of tumor budding in rectal cancer biopsies before neoadjuvant therapyMod Pathol201427115616223887296

- UenoHKajiwaraYShimazakiHNew criteria for histologic grading of colorectal cancerAm J Surg Pathol201236219320122251938

- UenoHHaseKHashiguchiYNovel risk factors for lymph node metastasis in early invasive colorectal cancer: a multi-institution pathology reviewJ Gastroenterol Epub9252013

- UenoHHaseKHashiguchiYSite-specific tumor grading system in colorectal cancer: multicenter pathologic review of the value of quantifying poorly differentiated clustersAm J Surg Pathol201438219720424418853

- BarresiVReggiani BonettiLBrancaGDi GregorioCPonz de LeonMTuccariGColorectal carcinoma grading by quantifying poorly differentiated cell clusters is more reproducible and provides more robust prognostic information than conventional gradingVirchows Arch2012461662162823093109

- BarresiVBonettiLRIeniABrancaGBaronLTuccariGHistologic grading based on counting poorly differentiated clusters in preoperative biopsy predicts nodal involvement and pTNM stage in colorectal cancer patientsHum Pathol201445226827524289972

- SwinsonDEJonesJLRichardsonDCoxGEdwardsJGO’ByrneKJTumour necrosis is an independent prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer: correlation with biological variablesLung Cancer200237323524012234691

- FrankIBluteMLChevilleJCLohseCMWeaverALZinckeHAn outcome prediction model for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with radical nephrectomy based on tumor stage, size, grade and necrosis: the SSIGN scoreJ Urol200216862395240012441925

- LangnerCHuttererGChromeckiTLeiblSRehakPZigeunerRTumor necrosis as prognostic indicator in transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tractJ Urol20061763910913 discussion 913–91416890651

- ZigeunerRShariatSFMargulisVTumour necrosis is an indicator of aggressive biology in patients with urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tractEur Urol201057457558119959276

- PollheimerMJKornpratPLindtnerRATumor necrosis is a new promising prognostic factor in colorectal cancerHum Pathol201041121749175720869096

- RichardsCHFleggKMRoxburghCSThe relationships between cellular components of the peritumoural inflammatory response, clinicopathological characteristics and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancerBr J Cancer2012106122010201522596238

- RichardsCHRoxburghCSAndersonJHPrognostic value of tumour necrosis and host inflammatory responses in colorectal cancerBr J Surg201299228729422086662

- KomoriKKanemitsuYKimuraKTumor necrosis in patients with TNM stage IV colorectal cancer without residual disease (R0 status) is associated with a poor prognosisAnticancer Res20133331099110523482787

- GuthrieGJRoxburghCSRichardsCHHorganPGMcMillanDCCirculating IL-6 concentrations link tumour necrosis and systemic and local inflammatory responses in patients undergoing resection for colorectal cancerBr J Cancer2013109113113723756867

- JassJRMorsonBCReporting colorectal cancerJ Clin Pathol1987409101610233312296

- KlintrupKMäkinenJMKauppilaSInflammation and prognosis in colorectal cancerEur J Cancer200541172645265416239109

- RoxburghCSSalmondJMHorganPGOienKAMcMillanDCTumour inflammatory infiltrate predicts survival following curative resection for node-negative colorectal cancerEur J Cancer200945122138214519409772

- PowellAGFergusonJAl-MullaFThe relationship between genetic profiling, clinicopathological factors and survival in patients undergoing surgery for node-negative colorectal cancer: 10-year follow-upJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol2013139122013202024072233

- OginoSNoshoKIraharaNLymphocytic reaction to colorectal cancer is associated with longer survival, independent of lymph node count, microsatellite instability, and CpG island methylator phenotypeClin Cancer Res200915206412642019825961

- ShiaJEllisNAPatyPBValue of histopathology in predicting microsatellite instability in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and sporadic colorectal cancerAm J Surg Pathol200327111407141714576473

- GreensonJKHuangSCHerronCPathologic predictors of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancerAm J Surg Pathol200933112613318830122

- NagtegaalIDMarijnenCAKranenbargEKLocal and distant recurrences in rectal cancer patients are predicted by the nonspecific immune response; specific immune response has only a systemic effect – a histopathological and immunohistochemical studyBMC Cancer20011711481031

- DeschoolmeesterVBaayMVan MarckETumor infiltrating lymphocytes: an intriguing player in the survival of colorectal cancer patientsBMC Immunol2010111920385003

- KimYWJanKMJungDHChoMYKimNKHistological inflammatory cell infiltration is associated with the number of lymph nodes retrieved in colorectal cancerAnticancer Res201333115143515024222162

- RichardsCHRoxburghCSPowellAGFoulisAKHorganPGMcMillanDCThe clinical utility of the local inflammatory response in colorectal cancerEur J Cancer201450230931924103145

- GalonJCostesASanchez-CaboFType, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcomeScience200631357951960196417008531

- GalonJMlecnikBBindeaGTowards the introduction of the ‘Immunoscore’ in the classification of malignant tumoursJ Pathol2014232219920924122236

- LugliAKaramitopoulouEPanayiotidesICD8+ lymphocytes/tumour-budding index: an independent prognostic factor representing a ‘pro-/anti-tumour’ approach to tumour host interaction in colorectal cancerBr J Cancer200910181382139219755986

- NielsenHJHansenUChristensenIJReimertCMBrünnerNMoesgaardFIndependent prognostic value of eosinophil and mast cell infiltration in colorectal cancer tissueJ Pathol1999189448749510629548

- Fernandez-AceneroMJGalindo-GallegoMSanzJAljamaAPrognostic influence of tumor-associated eosinophilic infiltrate in colorectal carcinomaCancer20008871544154810738211

- GulubovaMAnanievJYovchevYJulianovAKarashmalakovAVlaykovaTThe density of macrophages in colorectal cancer is inversely correlated to TGF-β1 expression and patients’ survivalJ Mol Histol201344667969223801404

- ForssellJObergAHenrikssonMLStenlingRJungAPalmqvistRHigh macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlates with improved survival in colon cancerClin Cancer Res20071351472147917332291

- ChaputNSvrcekMAupérinATumour-infiltrating CD68+ and CD57+ cells predict patient outcome in stage II-III colorectal cancerBr J Cancer201310941013102223868006