Abstract

In this study we adopt a critical perspective and explore different coaching styles in quality improvement (QI) work in the provision of healthcare. Coaching has gained attention as an effective way to enhance QI in healthcare. This study investigates how coaching is realised in terms of learning: What kinds of learning ideals pervade QI coaching, and how is support for learning realised, given the prevailing conditions in a contemporary healthcare system? For the purpose of this case study, a group of coaches exchanged experiences about their pedagogic roles and the strategies that they employed, on four occasions, over a period of 4 months. The conversations were filmed and then analysed, using critical discourse analysis as an analytic framework. Three parallel styles of coaching were identified, which were symbolised by (1) a pointing, (2) a bypassing and (3) a guiding discourse. No persistent dominance of any one of the discourses was found, which suggests that there exists an ever-present tension between the pointing and guiding pedagogies of coaching activities. The findings indicate that QI coaching in healthcare is more complex than previous conceptualisations of coaching. Additionally, the findings present a new, ‘bypassing’ coaching style which the coaches themselves were not fully aware of.

The presence of coaches to support quality improvement (QI) in healthcare has gained some attention the last 15 years. It has been noted that QI collaboratives that enjoy support from a coach have delivered steady gains over time (Gustafson et al., Citation2013). Coaching has also shown itself to be more cost-effective compared to other supporting initiatives, like, for instance, learning seminars (Gustafson et al., Citation2013). A specific team-coaching model has been developed and has been evaluated as providing frontline staff even more ability to effect improvement (Godfrey, Citation2013). It is the ‘tailoring’ function of coaching, whereby an idea of change can be adapted to a particular context, which is the most beneficial attribute of coaching QI in healthcare (Gustafson et al., Citation2013). However, the literature does not inform us exactly what is required of a ‘tailoring’ coach for QI in contemporary healthcare systems. We also note that the current research on QI coaching in healthcare does not conceptualise coaching, and neither does it link QI coaching in healthcare to more general coaching research from other service organisations. Even though one might follow a particular coaching model for QI, such a model will not inform one how to cope with the specific contextual conditions of QI practice. In the literature on improvement science, context is, furthermore, seen as ‘everything’ (Bate, Citation2014) and ‘problematic’ (Dixon-Woods, Citation2014) in the sense that context should be regarded as part of all QI work, and not perceived as a mere parallel phenomenon. In this study, we regard QI coaching as institutionally embedded and conditioned by the healthcare system in which it occurs.

To let someone else bear the burden of change is a well-known phenomenon in contemporary society. People seem to put their faith in ‘personal trainers’, who they rely on to break old, unhealthy patterns of behaviour, in favour of more positive behaviour patterns. But what happens if we start to rely too much on these ‘personal trainers of change’? The overarching QI mission should include the creation of a learning organisation through profound knowledge for improvement and interaction among the professionals (Deming, Citation1994). How does this fit in with the late modern idea of individualising knowledge of change in the work performed by coaches? One point of departure that this study takes is to note that the degree to which the individualisation takes place is dependent on how the coaches support learning whilst they simultaneously adapt to the prevailing conditions. This is the so-called ‘tailoring function’ from a pedagogicalFootnote1 perspective.

The aim of the present study is to investigate how coaches pedagogically approach QI coaching in contemporary healthcare systems. The study examines the following questions: (1) How do coaches describe the roles and strategies that they employ that guide learning in QI work? (2) Which discursiveFootnote2 patterns can be identified in light of the prevailing contextual conditions? (3) Why do the discourses that were identified occur in contemporary QI practices?

The paper is organised in the following way. First, we present a definition of what a pedagogical approach to QI coaching in healthcare is. This is followed by a description of the case study and an explication of how the data collection and the analytical process were theoretically informed and conducted. The findings are presented in terms of how they relate to the three questions of inquiry that are raised in this paper. The paper ends with a concluding discussion in which the present research findings are related to previous conceptualisations of coaching.

A pedagogical approach of coaching quality improvement in healthcare: definitions

Quality improvement and coaching

The field of QI in healthcare is characterised as a change management approach towards achieving an evidence-based, effective, high-quality, patient-centred, safe, accessible and equitable healthcare service (IOM [Institute of Medicine], Citation2001; National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2006). QI in healthcare is especially influenced by Edward Deming's (Citation1994) ideas concerning change management. Deming claims that staff members need to develop knowledge about how to both clarify customer processes and business aims, and measure variation and performance outcomes. They should be able to do this in order to make business decisions that are based on facts, rather than beliefs. Deming also focuses on a social system of change in which the interdependence of professionals, as well as the interdependence between specialised sub-units of care, is acknowledged.

Coaching QI in healthcare seems to be effective and the usefulness of coaching is explained in terms of a ‘tailoring’ function, whereby the point of change can be adapted to a particular context (Gustafson et al., Citation2013). Even though coaching seems to be effective, conceptually, it can be interpreted – and consequently, organised – in different ways. To develop a broad perception of how coaching can be conceptualised, we examine the more general literature on coaching (not only QI coaching in healthcare). Bond and Seneque (Citation2013) have tried to delimit what coaching includes by comparing it to other forms of change management approaches, including managing, consulting, mentoring and facilitating. The present case study explores pedagogical approaches of QI coaching in healthcare. The present study's findings can thus be related to Bond and Seneque's description of coaching, but also allows us to expand the present explication of ‘a tailoring function’ in our conceptualisation of QI coaching. In order to do this, we present a short discussion of how Bond and Seneque (Citation2013) characterise coaching in relation to other change management approaches:

Coaching emphasises goal-setting and self-reflection in an effort to build the capacity within a workforce to work relationally, socially and organisationally. The authors thus claim that ‘coaching’ includes both a social perspective and a managing perspective. Coaching is an approach that focuses on aspects of the work situation and context in which issues of power are addressed and negotiated as part of the relational process. Managing, in contrast, is based on unequal power dynamics, meaning that resourses, people and processes are controlled and directed by a manager. In this approach, strategic thinking is balanced with operational planning, in which the monitoring of actions is considered to be crucial. Consulting is also an approach in which power remains with the consultant, who is perceived as possessing the necessary technical and process expertise to effect change within the organisation. Consulting is characterised by the use of an external perspective in an effort to promote change. Mentoring (as explained by Bond and Seneque), is not appropriate as a change management approach for QI coaching in healthcare, because it merely consists of support for individual growth, and cannot be used for team or organisational development. Finally, facilitating is described as an empowering mode of change management that promotes reflection and frameworks for social interaction. Facilitating includes a focus on guiding the change process forward, in cases in which power generally remains within the group that is engaged by the change process.

The above conceptualisation of coaching echoes Deming's (Citation1994) twofold emphasis on social change and business aims. The tension between (1) facilitating social learning processes and (2) managing business aims is also a challenge that the QI coaches have to deal with. Thus far, research on QI in healthcare has mostly focused on the technical aspects of improvements, while the social aspects of change has been somewhat taken for granted (Bate, Mendel, & Robert, Citation2008; Dixon-Woods, Citation2014). Furthermore, QI research adopts either a micro- or a macro-system focus, but rarely are both system levels considered together (Bate et al., Citation2008). In our view, the lack of multi-level focus is a deficiency of investigations on coaching and social interactions. General coaching research emphasises the idea that coaching needs to be institutionally conceived (Bond & Seneque, Citation2013; Werr & Styhre, Citation2003). In this paper, we adopt the view of the coach–QI practice relationship as being institutionally embedded, emphasising the claim that it ceases to exist if detached from social norms, economic demands or ideologies. The term context is used to refer to both the internal conditions as well as the external conditions of the QI practice. Internal conditions include features such as power structures, social norms and loyalties that affect the coach's interaction within the staff group. External conditions include organisational economic demands, broader cultural norms and societal trends. Our aim with the present paper is to contribute to the improvement science field in healthcare by linking our findings with respect to a particular form of coaching to more general conceptualisations of coaching (Bond & Seneque, Citation2013). We do so by analysing and explaining how the coaches interact with QI practices, keeping the prevailing influence of the healthcare system in mind.

A pedagogical approach to coaching

The terms approach, method and tool are often used as synonyms. We will attempt (as did Werr, Stjernberg, and Docherty (Citation1997)) to assign diverse meanings to the terms so as to enable a thorough description of the context of the coaching that took place in this particular case study. We regard an approach as an overall perspective that can be associated with coaching QI. The term approach thus includes the underlying coaching values and beliefs, as well as the motive(s) behind the coaching and how one might bring a coaching program about. The term method is used to describe how QI is achieved. It refers to the operational guidance of how a successful change process is managed, including specific actions such as what should be done, when, how and by whom. In the present case study, the coaches used the team-coaching model that previous research has proven to be useful (Godfrey, Citation2013). To solve specific problems within the change process, one also needs to use tools such as questionnaires, checklists and other measurement tools. This study investigates an approach in coaching as defined above.

Note that we did not investigate any approach. For the purposes of this study, we investigated the pedagogical approach that was used by the QI coaches. During the course of improvement work, different professional perspectives are exchanged, so that each participant develops an understanding of others’ work, the practices that they have in common, and his or her individual contribution. Improvement work can thus be understood as a pedagogical practice, whereby the participants develop socially, as well as in terms of their knowledge, via communication, reflection and action (Johannessen, Citation1994). The learning that takes place in a QI practice can be regarded as a negotiation of change that is socially and institutionally conditioned (Dewey, Citation1916/1997; Norman, Citation2015; Wenger, Citation1998). As we take on a critically informed view of how a coaching practice is institutionally embedded, we are then able to investigate how contextual conditions (external and internal) influence learning in coaching QI in healthcare.

The case context

Case selection

To obtain insight into QI coaches’ pedagogical approaches, we asked a development unit in a county council in Sweden to participate in the study. This specific development unit was selected because of the county council's renowned use of QI as a strategy to improve its delivery of care. This specific case and its ‘circumstantiality’ (see Geertz, Citation1973), should thus be recognised as a healthcare system in which QI is part of its every-day practice in terms of culture, knowledge and access to coaches as facilitators of improvement work. The researcher (first author) presented the study to the development unit and, after this initial presentation, four QI coaches volunteered to participate in the study.

The literature on coaching research states that there is empirical support for the efficacy of internal as well as external coaching (Grant & Cavanagh, Citation2004). However, this claim depends on what one means by ‘internal or external coaching’. In the present study, we regard the participating coaches as internal in the light of the fact that they are employees of the county council and in light of where they primarilyFootnote3 perform their coaching activities. Accordingly, these coaches are fully aware of the conditions of the overall organisation in which their QI practices are embedded. However, the coaches are also external in the sense that they are not members of the particular QI practices that they coach. They are not part of the internal conditions of the QI practice, nor are they accountable for the QI practice's performance. The coaches can thus be regarded as internal (‘in-organisational’) consultants, despite being external to the QI practice.

Areas of coaching and legitimacy

The coaches’ work responsibility with respect to coaching includes two main areas: (1) to teach QI tools, including the Model for Improvement (Langley, Nolan, Nolan, Norman, & Provost, Citation1996), the Clinical Microsystem Model (Nelson, Batalden, & Godfrey, Citation2007), Statistical Process Control (Provost & Murray, Citation2011) and so forth, and (2) to coach QI projects, ranging from large-scale national projects to smaller local initiatives of change. Their coaching efforts concern initiatives with respect to patient safety, accessibility, capacity-demand projects, service-user involvement, and the implementation and use of quality registers. Coaches’ professional efforts also take into account different regional initiatives for improving the process of care for different subgroups of patients, including cancer patients for example. Their coaching is concerned with broad organisational perspectives, ranging from specialist care to nursing homes run by municipalities, and preventive healthcare. The participating coaches thus have a broad experience base of QI in healthcare, ranging from 3 to 18 years in duration, with a median of 12 years of experience across the group.

The coaches’ legitimacy to lead and to teach QI depends on how they were given their assignments. Sometimes, their services are asked for by different clinical managers because a local and (perhaps) well-known problem needs to be solved. In other projects, the coaches are commissioned to launch national QI projects, which the local QI practices do not necessarily regard as a problematic issue. The coaches’ expertise and knowledge are not in any doubt because the particular development unit, where the coaches are employed, is nationally, and internationally, renowned for being a QI development unit of excellence. Consequently, the mandate to coach QI is mostly due to a local need for change.

Data collection and ethical considerations

The researcher gathered the participating coaches into a group where they met, reflected on their work, and exchanged experiences. The researcher led and thematised the conversations, but it was the coaches who contributed with actual data in terms of their reflections on the pedagogical strategies that they employ in their professional work. The group met four times, starting on the 6th September and ending on the 18th December 2013. Each session was about an hour and a half in duration. The sessions were filmed using a stationary video camera so as to facilitate later transcriptions and the analysis of ‘who said what’. The films (315 min in total) were transcribed into text. The transcriptions and analysis were done in the original Swedish that was spoken by the coaches, and then the findings were translated into English (Nikander, Citation2008).

An initial assumption of the researchers was that the coaches possess tacit knowledge with respect to how they pedagogically approach different situations. To bring their experiences to the fore, a pedagogic method of dialogue seminar was used (Göranzon, Citation2001). As a preparatory activity for the first session, the coaches were requested to tell a story about a situation about which they had reflected on what took place in terms of learning. The coaches told their individual stories, while the others listened and reflected on each other's personal experiences. The researcher moderated the conversations with follow-up questions and other conversation techniques so as to deepen the coaches’ reflections and to clarify what the informants meant with their different utterances. The researcher also made video observations of how the coaches performed in their real-life practices, and then later showed some selected sequences of these video observations to the group, so as to enable a further deepening of the coaches’ reflections.

The study was designed according to an interactive research approach (Ellström, Citation2008). The researcher and the participating coaches met twice to plan the process, and twice to discuss and validate the findings together. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Linköping, SwedenFootnote4 .

Analytical framework and analytical process

Critical discourse analysis

Researchers in the field of organisation science emphasise the fact that there is a need for critically influenced studies with a discursive perspective, so that influences on learning and knowledge in organisations can be properly investigated (Contu & Willmott, Citation2003; Currie & Suhomlinova, Citation2006). Critical discourse analysis (CDA) (Fairclough, Citation1992) offers a multi-layered framework of scrutinising how coaches approach learning. In the present study, CDA is used to reveal how the conditions (both internal and external) of a QI practice make themselves manifest in the discursive patterns of coaching. CDA illuminates how discourses shape and limit the ways that the coaches think, speak and conduct themselves when they interact within a QI practice. The study thus includes a critical interest in providing QI coaches with an awareness of how their professional coaching is influenced by the healthcare system within which they work and its prevailing conditions.

The analytical process was performed according to Fairclough's (Citation1992) three-step analysis of (1) description, (2) interpretation and (3) explanation. The analytical framework is presented in detail in .

Table 1 The analytical framework and findings of each analytical phase

Metaphors of learning in the descriptive analytical phase

In the past 10 years, there has been increasing scientific interest in how CDA relates to metaphor studies, especially with respect to the dialogic function of metaphors in conversations (Musolff, Citation2012). In the descriptive analytical phase of the present study, the researcher used the coaches’ own metaphorical expressions as designations of their different pedagogical approaches. Notably, it has been claimed that the use of metaphors simultaneously enhances the creation and production of discourse (Gibbs & Lonergan, Citation2009). Metaphors are used because cognitively oriented theories of meaning claim that metaphors are important mediators of understanding our physical, social and inner world (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1980). It is also claimed that metaphors greatly influence how learning processes are expressed in organisations (Fritzén, Citation2007). This study has a practical knowledge interest and aims to provide support for future professional discussions between QI coaches. The ‘metaphor-labelling’ process can support recognition of, and further reflection on, how coaches can guide learning in QI work. In such future discussions, it is important to note that the metaphors that are used need to be interpreted in relation to the context in which they were invoked (Zinken & Musolff, Citation2009).

Empirical questions were used to scrutinise what kind of roles and strategies the coaches used when they interacted with the staff groups (see , the descriptive phase). Their roles and strategies were grouped into three main approaches, which were named according to the coaches’ own metaphorical expressions. The three pedagogical approaches provided the basis for the interpretive analysis, which, in turn, formed the basis for the explanatory analysis.

Strategic rationality and communicative rationality in the interpretive analytical phase

Habermas’ (Citation1987) concepts of ‘strategic rationality’ and ‘communicative rationality’ were used as an analytical interpretive lens as we examined how the coaches were influenced by the contextual conditionsFootnote5 . Habermas describes two types of human rationality: strategic rationality and communicative rationality. Strategic rationality is goal oriented, such that the individual objectifies others so as to achieve his or her own goals. In the context of QI, strategic rationality deals with questions such as: How can the staff optimise their production? How can the organisation be differentiated in order to control, measure and compare performance outcomes? In contrast with strategic rationality, communicative rationality is oriented towards the achievement of understanding, so that the individual sees others as subjects and desires to achieve mutual understanding via dialogue. Communicative rationality gives rise to questions such as: How can dialogue decrease the difference in status between participants so that a symmetrical relation may come to exist? Strategic rationality and communicative rationality are incompatible with each other, but, at the same time, together, they form an inevitable whole.

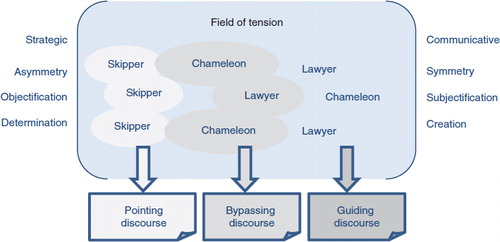

To interpret the conditioning influence of the healthcare system in the second analytical phase, we divided the concepts of ‘strategic rationality’ and ‘communicative rationality’ into three analytical pairs that characterise the tension between these rationalities. Strategic rationality is characterised by asymmetry, objectification and determination, while communicative rationality is characterised by symmetry, subjectification and creation (Fritzén, Citation1998). In relation to the object of study, the first analytical pair, asymmetry–symmetry, thus signifies the power relationship between the coach and the QI practice that is being coached. The second pair, objectification–subjectification, signifies the attitude that the coach addresses the QI practice. Finally, the third analytical pair, determination–creation, signifies what is already predetermined in relation to what can be created by the QI practice itself. These analytical pairs should be regarded as continuums that frame a field of tension between strategic rationality and communicative rationality (see ) and not mere categorical opposites of different characteristics. The researchers used the analytical pairs as an interpretive lens and situated the coaches’ pedagogical approaches in this field of tension, depending on whether the coaches’ arguments were based on strategic rationality or on communicative rationality. During this interpretative process, the discourse patterns gradually emerged.

Fig. 1. The identification of discourses.

A field of tension is constructed by three complementary pairs of characteristics that are found in strategic and communicative rationality (Fritzén, Citation1998; Habermas, Citation1987). The analysis situates each pedagogical approach in the continuum between the characteristics, which allows for the identification of three different discourse patterns: (1) a strategic pointing discourse, (2) a bypassing discourse that comprises of both strategic and communicative characteristics and (3) a communicative guiding discourse.

Profound knowledge of improvement as a QI pillar in the explanatory phase

To comprehend why certain discourses occur in a QI practice, we need to consider closely the ideas that are shared in the practice and the conditions under which the practice takes place. In Sweden, QI ideas are articulated in a national healthcare policy, God vård (‘Good care’) (The National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2006) and in this policy's emphasis on Profound Knowledge of Improvement (Deming, Citation1994). The overall aim of the policy is to develop evidence-based, safe, patient-centred, efficient, accessible and equal healthcare that is inspired by the IOM's (Citation2001) parameters of quality in healthcare. The QI coaches base their professional mission on the ideas contained in God vård and Profound Knowledge of Improvement, which they use as a professional compass when they navigate through the contextual conditions of their practice.

Findings

The coaches’ descriptions of how they guide learning in QI work

Three pedagogical approaches appear in the coaches’ discussions of the roles and strategies that they adopt in their interaction with the staff groups that they work with. The approaches are labelled (1) the chameleon approach, (2) the skipper approach and (3) the lawyer approach. It is important to note that each of the participating coaches do not solely represent a specific approach. The coaches contributed with their experiences to all of these approaches.

The chameleon approach

The coaches suggest that they see themselves as generalists who possess a broad arsenal of abilities that are sensitive to the staff's needs with respect to the choice of the particular pedagogical strategy they will use with the staffFootnote6 :

Coach 2 That's the thing about being a coach. You've got to find, of course … What does this particular team need? And you have to be a chameleon and be such a generalist so that you can go in … ok, we need to work on relations … umm … we need to work with the structures, or whatever they are. Umm, then you need many different tools in your toolbox.

It is thus important to establish a relationship with the staff group. Before they begin to coach, the coaches aim to blend in with the group's way of talking, and use and relate to the group members’ questions and examples so as to gain their confidence:

Coach 2 The goal here is to get them to feel that I am one of them.

This effort to become ‘one of them’ and to adapt to the group is not just done for convenience's sake; instead, it is a conscious strategy that is employed by the coach so that the staff will buy into the idea of QI work:

Coach 2 This first thing that I say to the group is that I am a [PROFFESSION] … So immediately they know that I know what's up, and that I am on their side … And this is a conscious strategy of course to win the group over … a completely conscious strategy, you know.

Even if the choice of the chameleon strategy is a conscious, tactical choice, the way it is employed by the coach is not as controlled and determined as one might think. Instead, we might consider that it is used to introduce oneself to the group, and interact with the group on its own level. Note that the coaches do not wish to be seen as being sent out into the field by management:

Coach 2 It's about coming over to their side and agreeing with them, instead of going against them.

The coaches, however, are of the opinion that there is one danger with the chameleon strategy, namely, nothing might happen. There is no push towards performing QI work, if the coach just listens to the group's needs all the time. Consequently, it is advantageous for the coach to be more goal oriented, like the skipper that is described in the following section. The coaches describe their situation as a constant balancing act between listening to the group and pushing the group forward.

The skipper approach

The skipper approach is invoked when the coaches report on a focus on goals and results, in situations in which they are the driving force and methodical in their pedagogical role:

Coach 3 Because I like to say now we will achieve this goal and I, you know, have a plan ready, so ‘Let's do it!’

In contrast to the chameleon approach, we note that this coach now takes control of the situation and, as authorised by the management, establishes the goals that the group are to achieve. In the skipper approach, the coach's relationship with the group is not in particular focus. Instead, the coach's strategy is to follow the QI methods, step by step, so as to increase the work tempo so that the group gets involved in the work that needs to be done:

Coach 3 But I am not really sensitive to how the group is, but more so if I notice that they are not straight with me. Then I have become better at trying out other ways so that I get … so we all … now we all are … now we are all in the same boat, you know what I mean.

The skipper strategy does not allow for the group to sit back and relax, and claim that they already produce good quality work. Evaluations and checks are important components which are used to verify their performance:

Coach 4 ‘Well, we already do that’, they say then. But where do I see it? ‘But we just know. We do!’ You might think that you do. But we must be able to verify what we do with some form of measurement.

Consequently, the skipper approach associates successful coaching with better performance, whilst the coaches put a great deal of responsibility on themselves to achieve the improvements.

One advantage with the skipper approach is that the groups are put into immediate action and things happen quickly. A disadvantage with this approach is that it can be somewhat forced and the group may fail to follow the coach or understand what they are striving for:

Coach 3 And I felt like … if I had waited and listened to the group, and instead let them do more on their own … that would have been better.

The lawyer approach

When the lawyer approach is employed, the coaches claim that their mission is to create more value for the patient. One of the coaches described a situation in which she had to initiate a group into thinking about broadening their QI work for the patients’ best so that the group did not only develop aspects of their operation where they made the most money on:

Coach 3 But they were so keen that new visits [which gives increased funding] be measured. But then you need to keep an eye on return visits too so that the cancer does not spread. ‘Are you keeping tabs on that?’ Well, not really. So I am motivated to really find the counterbalance to this thing with money. Things should be worth the value that they create for the patients. It shouldn't be the case that they get more money

Coach 4 You are kind of the patient's advocate in some way.

The advocate-coach needs to ‘defend’ that which creates value for the patients, so that the staff members do not reduce the patient to a mere economic variable that is part of a system of financial incitements. The coaches state that they have to address two central questions so that the staff will understand the value of QI. The first question is: Why should they accomplish improvements? The second question is: How can these improvements be enacted in practice? The question ‘Why?’ requires the group to identify and understand what creates additional value for the patients. If they are not able to do this, there will be no internal motivation in the group to act in a way that is best for the patient. The coaches’ strategy is based on the belief that internal motivation will lead to more sustainable improvements:

Coach 2 So my belief is, when you get the teams to start moving. Then they are incredibly motivated and mature … and receptive, and then you get better sustainability. If we get that movement started.

Similar to the chameleon approach, the lawyer approach connects successful coaching with the understanding of the ‘Why?’ question, for example, inspiring the staff groups to run their own improvement work:

Coach 3 Now I see that they themselves take the initiative. Then I feel that I have succeeded. When I see them do it by themselves and they know what they are doing.

The coaches even involve the patient in the QI work. But this is not without its problems, considering the asymmetrical relationship between the staff and the patient. The coaches use different methods to support a symmetrical participation in the dialogue, so as to allow for patient input into the process. However, success as a coach is not solely dependent on the strategies that are employed by the coach. Traditional habits, culture, norms and hierarchies present themselves as obstacles to QI work, since these conditions make it difficult for the coaches to establish legitimacy for that which creates additional value for the patients. The coaches are of the opinion that, as their experience increases, the easier it is for them to deal with opposition:

Coach 2 Ahem, I have used more guerrilla warfare methods than full-scale frontal attacks. If I come across any opposition, then I back off a bit and check if I can find a different way forward.

Identification of discursive patterns in the light of the prevailing contextual conditions

The coaches used three different pedagogical approaches when they interacted with the staff groups. Given this, we ask: What discursive patterns do these approaches reveal with respect to the healthcare system that they are part of? In the following section, the coaches’ approaches are examined through an analytical lens of three complementary pairs that characterise strategic rationality and communicative rationality.

Asymmetry and symmetry

The skipper approach invokes an asymmetric relationship between the coach and the staff, by setting the agenda and by using QI methods strictly, step by step, to gain results as fast as possible. The skipper approach moves the staff on to pre-established goals by virtue of the coach's power position. In contrast, the chameleon approach denies the coach's ‘manager’ role as the coach continuously adapts to the staff group by using their ‘native’ language and by adjusting examples and methods to the staff's common practice. This is done with the goal of becoming ‘one of them’. The coach wants to be accepted into the social community of the staff group. However, the chameleon's pursuit of symmetry is a deliberate and disguised strategy that is used to hide the real goal of enrolling the staff into performing QI work. The symmetric nature of the lawyer approach is more pronounced and obvious. Coaches who employ the lawyer approach feel obliged to defend patient values against asymmetrical hierarchies as well as economic allurements.

Objectification and subjectification

To achieve quick results, the skipper approach objectifies the staff and holds them accountable for their performance. It is an outcome-oriented approach, in which the staff's achievements are measured to evaluate whether they actually deliver better solutions for the patient. In contrast, the lawyer approach and the chameleon approach reveal a different perspective, since these approaches prioritise sustainable improvements by establishing QI work that is based on intrinsic motivation. These two approaches regard the staff as subjects who can set their own goals, take responsibility for their work and can ultimately perform the QI work themselves. The idea of empowerment that is included in the lawyer approach also includes the patient, who is seen as a member of a QI team and a co-creator of healthcare improvement. In contrast, the skipper approach seeks to deliver the patient a better solution that is solely contrived by the staff, without involvement by the patient. To empower patients, the lawyer approach has to fight against culturally determined norms and hierarchies that prevent patient values from coming to the fore. This struggle was described as ‘guerrilla warfare’ instead of a ‘full-scale frontal attack’ and provides us with a reason why the lawyer approach also contains a number of disguised strategic features when it comes to defending the patient.

Determination and creation

In the skipper approach, the responsibility is put on the coach to transfer the staff to predetermined goals that have been decided by management. The role of the coach within the chameleon approach and the lawyer approach is not that individualistic. Instead, the relationship between the staff group needs’ and the coach's guiding competence creates the conditions for achieving these goals. The coaches perceive themselves as generalists who can adapt their skills to what the staff group needs in different situations. If practices are going to improve in the long-term perspective, the staff members need to create their own planning on the basis of their own inner motivation and basic understanding of why QI is important. In such a scenario, coaching is considered to be successful when the staff group has taken over the initiative of change from the coach. The chameleon approach displays similar preferences with respect to creating and guiding the QI-work from the perspective of the staff group, although this approach employs more strategic thinking and certain features that are disguised by the coach.

The discursive patterns

By using the interpretive lens described above, we were able to place the pedagogical approaches in the field of tension that exists between strategic and communicative rationality (see ). During the interpretive process, the discursive patterns were gradually identified as (1) a pointing discourse, (2) a bypassing discourse and (3) a guiding discourse.

The pointing discourse is characterised by an orientation by the coach towards already predetermined outcomes. Consequently, the pedagogy that appears in this discourse can be described as ‘governing’ and aims at providing the patient with better solutions. The guiding discourse is characterised by a creative and step-by-step orientation towards sustainable results through the creation of greater understanding. This pedagogy is community-based and empowering, and thus includes the patient as a co-creator of improvement(s). The bypassing discourse is characterised by how structures and norms are ‘bypassed’ by concealing the real purpose of change. This discourse primarily employs the pedagogy that is seen in the guiding discourse, but with some manipulative elements added to avoid structures and norms that set obstacles for the realisation of patient-related values.

Explanation of why the discursive patterns occur in contemporary QI practices

The pointing discourse and the guiding discourse are easily recognised as basic QI ideas that can be found in the God vård policy. The pointing discourse coincides with the QI norm that mere talk about improvements is not enough; one has to act and measure one's performance so as to evaluate whether the changes that one has achieved actually have resulted in improvements. The pointing discourse relates to God vård by virtue of its expression of efficiency goals in the context of the healthcare system. The guiding discourse, on the other hand, relates to the patient-centeredness that is expressed in the God vård policy, and to the goal of establishing a self-supporting learning organisation. Deming (Citation1994) introduced the notion of ‘empowerment’ in association with efforts to implement improvements, on the basis of staff collaboration and their inner motivation.

The occurrence of the bypassing discourse does not primarily emanate from basic QI beliefs. Instead, its presence can be explained as the consequence of how these ideas challenge traditional structures in healthcare. Values such as efficiency and patient-centeredness give rise to a shift in legitimacy. The professionals lose a certain amount of power relative to managers and patients, which gives rise to a sense of suspicion towards QI work. This is the reason why the intention of the QI work has to be ‘camouflaged’ somewhat if the coaches are going to be accepted by the staff group. If the coaches adapt and become ‘one of them’, then they are seen as more trustworthy in the eyes of the professionals. The bypassing feature of the discourse entails that the coaches align themselves to these social expectations, simultaneously as they hold on to their ‘hidden’ professional mission, namely, to engage the staff in QI work. The coaches do not declare war in their campaign to protect patient values; instead, they adjust to existing structures and work ‘undercover’ as a way of bypassing dysfunctional structures.

The characteristics that the different discourses contain can thus be recognised as basic QI ideas or consequences of how these ideas challenge traditional structures in healthcare. However, the way in which the discourses may come to prevail within a practice depends on the contextual conditions. The guiding discourse, for example, dominates the others when economic incentives are implemented. This can be observed when the coaches prioritise the defence of patient values, instead of regarding financial incentives as a helpful push towards obtaining quicker results (as might be seen in the pointing discourse). The interpretive analysis did not show a persistent dominance of any one of the discourses that were found. On the contrary, the dominance between the different discourses identified above takes on a variable nature, depending on which condition comes to the fore within the practice and how this particular condition correlates with the legitimate ideas of each discourse. The occurrence of the discourses can be explained as an interaction between certain quality claims and the actual influence of the healthcare system.

Concluding discussion

In the following discussion, we return to the introductory questions of whether QI coaches act like ‘personal trainers of change’ who individualise knowledge of change, or whether they promote a social learning arena that empowers the QI practice. We have identified three parallel styles of coaching, which can be symbolised by the pointing, bypassing or guiding discourses. There is no evident persistent dominance of one discourse over the others. We thus claim that the tension between a pointing pedagogy and a guiding pedagogy is ever-present in the coaching activities. The coaches’ pedagogic values and beliefs are primarily part of the guiding style, as they connect successful coaching with the practice taking over the QI work themselves. A failure in coaching was mentioned in terms of a failure to involve the staff in the QI work to a sufficient degree. Simultaneously, the coaches value the pointing style because it enables them to avoid getting stuck in the process of doing QI work. The coaches expressed this challenge as a constant balancing act between listening to the group and pushing it forward.

If we relate the coaching approaches found in this study with the change management approaches described by Bond and Seneque (Citation2013), we find many similarities. What is obvious, however, is that their delimitation of coaching is not sufficient for a complete description of QI coaching in healthcare. The pointing style of coaching reported on in the present study more closely resembles ‘managing/consulting’ than ‘coaching’. It is also obvious that the guiding style that is reported on in the present study most closely resembles ‘facilitating’ and ‘coaching’. Accordingly, coaching QI in the context of healthcare provision includes broader perspectives and needs to be conceived in a more holistic manner than earlier descriptions of coaching (Bond & Seneque, Citation2013).

Perhaps of more interest is our observation that the bypassing style that was identified in the present study is absent in the description of coaching that is provided by Bond and Seneque. The coaches needed to bypass structures manipulatively to achieve progress. This raises the question: How can this be understood in the light of the challenges that face QI coaching in healthcare? Are professional structures in healthcare more orthodox and traditional compared to other organisations? Research on change management in IT, management and technical consulting organisations also show that professional identities are threatened, which consequently leads to resistance on behalf of the participants in the process of change (Schilling, Werr, Gand, & Sardas, Citation2012). Since research shows similar types of professional resistance in other service organisations, the identification of the bypassing style in the present study may instead be associated with the methodology that was used. When approaches (instead of methods and tools) are investigated, the intuitive and tacit knowledge of coaching comes to the fore. During the data collection sessions, the coaches became aware of how they strategically use examples, stories and language to be socially accepted. The coaches’ experiences were retold in the descriptive phase of the analysis. The CDA framework then offers two additional phases of analysis. In the interpretive phase of the analysis, we identified a bypassing discourse where the coaches adjust to existing structures and work ‘undercover’ as a way to avoid structures that pose obstacles for the realisation of patient-related values. Moreover, in the third phase of the analysis, we explained why the bypassing discourse occurs in a contemporary healthcare system in terms of it being a trans-boundary way of achieving progress in QI work. However, the coaches themselves were not aware of how their actions functioned as a way of feinting past dysfunctional structures. Consequently, the coaches did not engage in reflective discussions about whether it is ethical to bypass structures or the staff in practice with a concealed purpose. Again, this raises the question of whether it is even possible to go beyond dysfunctional structures without working ‘undercover’. These questions are important for QI coaches to reflect upon as they consider their pedagogic endeavours and training. The previously mentioned ‘tailoring function’ is not sufficient to describe all of the complexity of coaching. This is especially true when one considers the conditioning influence(s) extant within the healthcare system.

The design of the present study has subtly revealed the ‘practical wisdom’ that permeates QI coaching in healthcare. Dixon-Woods (Citation2014) claims that QI programmes that take local practical wisdom into account are more successful than programmes that blindly follow core theories of change. Dixon-Woods suggests that local, experienced-based contextual knowledge ‘is required to apprehend the significance of institutional context’ (p. 96). One practical implication that is made by the present study is to highlight the importance of ‘practical wisdom’ in QI coaching in healthcare. The coaching discourses that were identified in this study offer a relevant basis for future professional discussion, in which learning is not taken for granted, but preferably, learning is critically clarified in the light of existing circumstances. Or, as Carr and Kemmis (Citation1986/2006) express it: ‘Practices are changed by changing the ways in which they are understood’ (p. 91).

In terms of the pedagogy that was identified in this study, our findings also suggest that a number of benefits can be associated with being an external coach; that is to say ‘external’ in terms of the coach as not part of the specific practice and its governing system. Such a coach can guide the way forward towards the desired change(s) so that the staff can balance changes in values in a way that is congruent with the suggestions made in the God vård policy document. Previous pedagogical research shows that staff members experience difficulties in maintaining a balanced value perspective when financial incentives are deployed (Norman & Fritzén, Citation2012). In such circumstances, staff members learn more about how to gain money for the clinic than what creates value for the patient. In the present study, where external coaches support the QI practice, we note that the guiding discourse is found to be dominant when the QI practice is governed by extrinsic financial incentives. The degree to which an external coach versus an internal coach can support sustainable improvement has not been empirically explored or fully elaborated upon in the healthcare context. The examination and comparison of internal coaching versus external coaching is of future research interest, as well as a potential source of valuable knowledge for organisers of QI work in healthcare.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by The Vinnvård Research Program and the Department of Pedagogy, Linnaeus University. For other conflicts of interest, none were declared.

Notes

1 In the present study, we use the concept ‘pedagogy’ to place emphasis on the contextual conditions that influence learning processes in specific, and culturally situated, practices, as formulated by Fritzell (Citation1996).

2 In the present study, the term discourse refers to a particular way of speaking about, and understanding the world around us (Winther-Jørgensen & Phillips, Citation2000). Discourse includes language (written and spoken), symbols, non-verbal communication (gestures, movements, facial expressions) and visual images (Chouliaraki & Fairclough, Citation1999, p.38).

3 Note that if the coaches work on a regional or national arena, the coaches should rather be regarded as ‘external–external’ instead of being ‘internal–external’ as in the county council where they are employed.

4 Approval number: 2013/334-31.

5 Habermas’ theoretical framework has been used to explain how external conditions, as well as internal conditions, have to be considered in pedagogical practices (Fritzell, Citation1996).

6 All excerpts from the data material are marked with italics. Sometimes the authors have clarified the excerpts’ situational meaning by using uppercase words in brackets.

References

- Bate P. Context is everything, in perspectives on context. 2014; London: The Health Foundation.

- Bate P., Mendel P., Robert G. Organizing for quality. The improvement journeys of leading hospitals in Europe and the United States. 2008; Oxford: Radcliff.

- Bond C., Seneque M. Conceptualizing coaching as an approach to management and organizational development. Journal of Management Development. 2013; 32(1): 57–72.

- Carr W., Kemmis S. Becoming critical. Education, knowledge and action research. 1986/2006; Abingdon: Routledge Falmer.

- Chouliaraki L., Fairclough N. Discourse in late modernity. Rethinking critical discourse analysis. 1999; Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Contu A., Willmott H. Re-embedding situatedness: The importance of power relations in learning theory. Organization Science. 2003; 14(3): 283–296.

- Currie G., Suhomlinova O. The impact of institutional forces upon knowledge sharing in the UK NHS: The triumph of professional power and the inconsistency of policy. Public Administration. 2006; 84(1): 1–30.

- Deming W.E. The new economics: For industry, government, education. 1994; 2nd ed., Cambridge, MA: MIT, Center for Advanced Educational Services.

- Dewey J. Democracy and education. An introduction to the philosophy of education. 1916/1997; New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Dixon-Woods M. The problem of context in quality improvement, in perspectives on context. 2014; London: The Health Foundation.

- Ellström P.-E. Knowledge creation through interactive research: A learning approach. 2008. ECER Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, September, 2008.

- Fairclough N. Discourse and social change. 1992; Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fritzell C. Pedagogical split vision. Educational Theory. 1996; 46(2): 203–218.

- Fritzén L. Den pedagogiska praktikens janusansikte. Om det kommunikativa handlandets didaktiska villkor och konsekvenser [Pedagogical practice – The face of Janus: The didactic conditions and consequences of communicative action] (Doctoral thesis, Lund studies in education, No 8). 1998; Lund: Lund University Press.

- Fritzén L, Kostera M. Leading and learning through myth and metaphor. Mythical inspirations for organizational realities. 2007; Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Geertz C. The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. 1973; New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Gibbs R., Lonergan J, Zinken J., Musolff A. Studying metaphor in discourse: Some lessons, challenges and new data. Metaphor and discourse (pp. 251–261). 2009; London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Godfrey M. Improvement capability at the front lines of healthcare: Helping through leading and coaching. 2013; Jönköping: School of Health Sciences. (Doctoral thesis, Dissertation series No.46).

- Grant A., Cavanagh M. Toward a profession of coaching: Sixty-five years of progress and challenges for the future. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring. 2004; 2(1): 1–16.

- Gustafson D., Quanbeck A., Robinson J., Ford J., Pulvermacher A., French M., McCarty D. Which elements of improvement collaboratives are most effective? A cluster-randomized trial. Addiction. 2013; 108: 1145–1157. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Göranzon B. Spelregler – om gränsöverskridande. 2001; Stockholm: Dialoger. [Game rules – Transboundary stories].

- Habermas J. The theory of communicative action. The critique of functionalist reason. 1987; Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. 2001; Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Johannessen K. Tradisjoner og skoler i moderne vitenskapsfilosofi. 1994; Bergen: Sigma. [Traditions and schools in modern philosophy of science].

- Lakoff G., Johnson M. Metaphors we live by. 1980; Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Langley G., Nolan K., Nolan T., Norman C., Provost L. The improvement guide. A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. 1996; San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Musolff A. The study of metaphor as part of critical discourse analysis. Critical Discourse Studies. 2012; 9(3): 301–310.

- National Board of Health and Welfare. God vård – om ledningssystem för kvalitet och patientsäkerhet i hälso- och sjukvården [The provisions concerning the management system for quality and patient safety in health and medical care]. 2006; Stockholm: Publications from the National Board of Health and Welfare.

- Nelson E., Batalden P., Godfrey M. Quality by design – A clinical microsystems approach. 2007; San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Nikander P. Working with transcripts and translated data. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2008; 5: 225–231.

- Norman A. Towards the creation of learning improvement practices: Studies of pedagogical conditions when change is negotiated in contemporary healthcare practices. 2015; Växjö: Linnaeus University Press. (Doctoral thesis, Dissertation series No.221).

- Norman A., Fritzén L. Money talks: En kritisk diskursanalys av samtal om förbättringar i hälso- och sjukvård [Money talks: A critical discourse analysis of conversations about improvements in the provision of healthcare]. Utbildning & Demokrati. 2012; 21(2): 103–124.

- Provost L., Murray S. The healthcare data guide. Learning from data for improvement. 2011; San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Schilling A., Werr A., Gand S., Sardas J.-C. Understanding professionals’ reactions to strategic change: The role of threatened professional identities. The Service Industries Journal. 2012; 32(8): 1229–1245.

- Wenger E. Communities of practice, learning, meaning and identity. 1998; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Werr A., Stjenberg T., Docherty P. The functions of methods of change in management consulting. Journal of Organizational Change. 1997; 10(4): 288–307.

- Werr A., Styhre A. Management consultants- friend or foe. International Studies of Management & Organization. 2003; 32(4): 43–66.

- Winther-Jørgensen M., Phillips L. Diskursanalys som teori och metod. 2000; Malmö: Studentlitteratur.

- Zinken J., Musolff A, Zinken J., Musolff A. A discourse-centered perspective on metaphorical meaning and understanding. Metaphor and discourse. 2009; London: Palgrave Macmillan.