ABSTRACT

This study follows a group of modern foreign languages (MFL) teachers in the Netherlands during a nine-month professional development project around the theme of ‘Content in MFL’. The project was initiated following proposals to refocus the MFL curriculum on the basis of integrated learning outcomes for both language proficiency and areas of language-related content in the areas of Language Awareness and Cultural Awareness. The aims of the study were to explore the areas of content that teachers viewed as relevant to their MFL teaching, as well as the extent to which the introduction of MFL-specific content addressed teachers’ concerns regarding their practice. Perceived obstacles to the refocused curriculum were also addressed. Findings suggest that cultural content was a more relatable concept than language-related content for teachers in this study but also that language proficiency remained their central concern. Implications for the further development of the proposed content-focused curriculum are discussed.

Following repeated blows to the status of languages in secondary and higher education in the Netherlands (Graus & Coppen, Citation2016), it has been proposed that the school curriculum for modern foreign languages (MFL) should be reconceptualised, placing language-related content alongside language proficiency in centralised curriculum outcomes (Meesterschapsteam mvt, Citation2018). According to this proposal, a content-centred approach would help to support language learning by integrating content objectives with meaningful communication in the target language (TL), as in content and language integrated learning (CLIL). The content at the centre of MFL teaching would not be borrowed from other subject areas but be related to language as a discipline in its own right, for example in the form of literature, (inter)cultural knowledge, skills and understanding, and linguistics.

As with any educational reform, however, change can only be effected if not only policy-makers, but also teachers, support it (van Driel et al., Citation2001). A recent survey of MFL teachers and teacher educators in the Netherlands revealed that, while teacher educators were critical of the current MFL curriculum, teachers were largely satisfied with it and the freedom it offered them to explore their own approaches (Kaal, Citation2018). The question begs asking, therefore, as to whether support can be generated for a reconceptualisation of what it means to learn a language.

The purpose of the current study is to explore teachers’ responses to the idea of ‘content’ in MFL, the extent to which this aligns with their concerns regarding their own teaching and the perceived practical implications of an MFL curriculum that integrates content and language. Data were collected during a nine-month professional development project for MFL teachers on the theme of ‘Content in MFL teaching’.

Content in MFL

A number of schools of thought exist in which the learning of language and content are intended to support one another. In the Dutch context, the most prominent of these is CLIL, in which subject content teaching in the target language (TL) aims to support language use and language learning in a naturalistic context (Coyle et al., Citation2010). In the Netherlands, the position of CLIL aligns with Dalton-Puffer et al.’s (Citation2014) definition as being the domain of the TL-medium teacher of non-language subjects in that it is the preferred approach for teachers of English-medium subjects (e.g. Chemistry, Geography) in bilingual education (Mearns & de Graaff, Citation2018).

In Anglophone settings, however, CLIL is often the initiative of MFL teachers who want to bring more meaningful context to their lessons. In this case, they work together with colleagues from other departments or ‘borrow’ content from other subjects in order to feed meaningful communication and raise motivation within their own classroom (e.g. Mearns, Citation2012).

In spite of extensive literature on the benefits of CLIL and other content-based approaches to language learning (e.g. Hüttner et al., Citation2013; Lasagabaster & Sierra, Citation2009; Mearns, Citation2012; Mearns et al., Citation2017; Ruiz de Zarobe, Citation2013; Sylvén, Citation2007; Ting, Citation2010) and on the pedagogical practices involved (for a review, see van Kampen et al., Citation2018), the question of which content is placed at the centre of the approach has rarely been raised.

The Dutch context and a proposal for reform

There is no national curriculum in the Netherlands, although final curriculum outcomes attached to the school leaving certificates are stipulated on a national level. The current centralised curriculum outcomes for MFL in the Netherlands focus almost exclusively on communicative skills (reading, listening/watching, speaking, spoken interaction, writing), with reference to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, Citation2018). Literature receives some attention in the two most academic streams (Stichting Leerplanontwikkeling, Citation2013) and is assessed internally, as are listening, writing, speaking and spoken interaction in all streams. The final external examination for MFL, which accounts for 50% of the final grade, takes the form of a reading test consisting largely of multiple-choice questions. Research into beliefs and practices of student teachers has suggested that traditional grammar-based instruction and examination training still prevail in practice due to ingrained curricular practices and school culture, as well as students’ own experience as language learners (Graus & Coppen, Citation2016) and a washback effect of the weight of the final reading examination (Westhoff, Citation2012).

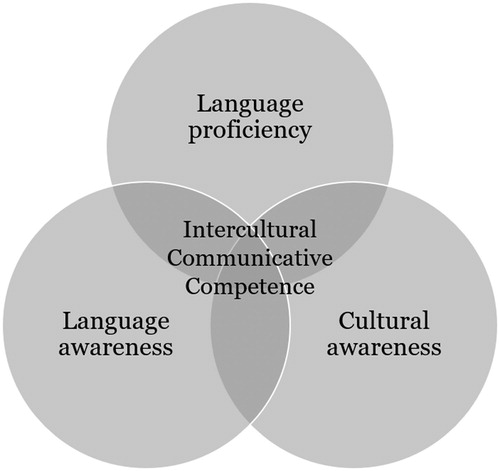

Against this backdrop, an inter-university group of specialists in foreign languages and foreign language literature, language acquisition and language education has proposed a reconceptualisation of the MFL curriculum (Meesterschapsteam mvt, Citation2018). The proposed Integrated Curriculum for MFL consists of three domains, as illustrated in . Development of intercultural communicative competence (ICC) would lie at the heart of MFL. According to Byram (Citation1997), ICC is achieved through a combination of knowledge, skills and attitudes that make it possible to understand, learn about and from, and interact across cultures, including taking a critical standpoint on one’s own culture. The Integrated Curriculum proposes that this can be achieved through increasing language proficiency while also engaging in meaningful content-learning related to the phenomenon of ‘language’ through both linguistic and cultural subject-matter. Using a CLIL-type approach in which both language and content aims are central to the curriculum, content-learning and development of language proficiency would support and strengthen one another.

Figure 1. The Integrated Curriculum for MFL (Meesterschapsteam mvt, Citation2018).

According to the proposal that accompanies the model in , language can be viewed from different perspectives: structural (e.g. phonology, discourse), cognitive (e.g. processing, language acquisition, bilingualism), social (e.g. dialects, language and power) and cultural (e.g. stereotyping, literature, knowledge and understanding of peoples, customs and traditions, visual texts). These perspectives relate to the overlapping domains of Language Awareness and Cultural Awareness, and to the central goal of ICC. Like the three domains of the model, these perspectives on language interrelate and overlap with each other. For example, while the cognitive perspective might relate largely to Language Awareness in terms of learning about the development of bilingualism in children, related questions around cultural integration or plurilingualism in society might fall more under Cultural Awareness. Learning in both of these areas might also support the language learning process, as learners grow more aware of what it means to acquire a language and to be plurilingual themselves. Critical exploration of the topic from multiple cultural and subject-specific perspectives can further support development of ICC (Meesterschapsteam mvt, Citation2018).

A number of individual research projects have been published in the Netherlands on teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding MFL content similar to those proposed in the Integrated Curriculum (e.g. Bloemert et al., Citation2016; Schat et al., Citation2018; van den Broek et al., Citation2018). Teachers’ responses to the suggestion to incorporate specific MFL content in centralised curriculum outcomes, however, have not yet been investigated.

The current study

The current study was carried out during a professional development programme aimed at encouraging MFL teachers to explore applications of ‘content’ in their own teaching. The purpose of the study was to investigate the extent to which the proposal to integrate content in MFL as suggested by the Integrated Curriculum could generate support among practitioners in the field. On one level, it was hoped that the study would provide insight into the extent to which the areas of content proposed in the Integrated Curriculum aligned with teachers’ ideas of ‘MFL content’ and provide concrete examples of linguistic and cultural content as used in practice. The first research question (RQ) was therefore:

Which forms does language-related content take in the eyes of this group of MFL teachers?

We also wished to explore the extent to which the introduction of a content-driven MFL curriculum appeared to be a feasible and desirable development in the eyes of teachers. RQ2 and RQ3, therefore, related to the concept of MFL content more broadly rather than to the specific content areas proposed in the Integrated Curriculum:

What is the relationship between language-related content and the real concerns of teachers?

Which problems do teachers perceive with regard to the introduction of language-related content in the MFL curriculum?

Method

Data for the current study were collected during a nine-month professional development project aimed at teachers and teacher educators in MFL, which ran from November 2017 to July 2018 and was subsidised by the Meesterschapsteam mvt.

Participants and data sources

Participants for the professional development project were recruited through advertising in the Meesterschapsteam’s professional network. The project began with seven participants in addition to two facilitators. Participants were informed during the first project meetings about the intention to collect data and provided written consent to use these data for research purposes.

Emma found it valuable to participate in meetings but not to explore the role of content in her own teaching. Her contribution to discussions during the first two meetings has been included in the data analysis but her teaching was not. Tracy was actively present in the first few meetings but had to leave the project early due to illness. Her contributions to discussions during the first meetings have been included in the data analysis. Neither Patty nor Eelco handed in any written documents, with the exception of Eelco’s conference presentation, although their teaching was discussed at length during meetings.

displays the details of each project participant, alongside the data sources provided by each of them. The data sources are elaborated on below.

Table 1. Overview of participants and contributed data sources.

By means of data sources, the project meetings were audio recorded and transcribed. These are referred to in as ‘Discussions during meetings’. In addition, participants were invited to contribute additional sources of written data that they considered relevant. These materials were collected by email or on paper during or directly following the project and took the following forms:

abstracts, notes and presentations from the conference

teaching materials

written reflections produced on the basis of prompts prior to the final meeting

We exercised communicative freedom (Kemmis, Citation2007) to let the participants develop communicative power and a sense of solidarity with each other. This form of cooperative inquiry ensured that each person’s agency was fundamentally honoured in the exchange of ideas in and outside of the meetings (Ponte & Smit, Citation2007). This resulted in different sources of data for the different participants, in reflection of the story that each of them wished to share.

Participant meetings and written reflections

The group met for five four-hour afternoon sessions throughout the academic year, facilitated by the authors of this paper, both of whom are teacher educators. During the meetings, participants discussed their teaching and ideas, and provided each other with feedback and suggestions. Early meetings began with a question from the facilitators regarding the concept of content in MFL, which sparked discussion. These discussions were followed by updates on each participant’s teaching and their progress or concerns so far. The facilitators and other participants responded with questions, comments and feedback aimed at helping their colleague to reflect on their experiences from different perspectives or to consider different approaches. The facilitators added to this discussion from their position as experts in CLIL and MFL teaching (first author) or teacher collaborative learning (second author). In later meetings, the initial discussions around content were no longer included, but the topic was returned to repeatedly during the discussions.

Between meetings, participants and facilitators communicated via email. In June 2018, the group attended a national conference on applied linguistics, where four of the participants presented their work in a symposium on the project.

Participants’ written reflections formed the basis for discussion during the final meeting. They were based on a series of propositions regarding content in MFL (e.g. The goal of content in MFL is to support language proficiency), and on reflection on their own practice and concerns using the 5 Whys analysis method (Mulder, Citation2012). The latter involved participants’ returning to the concerns they had originally hoped to address through embarking on the professional development project, and asking themselves why these concerns were important to them (for details of what these concerns involved, see the Results and Discussion section, in particular ). Through a series of four more ‘why’ questions, each in reference to the previous answer, it was hoped that participants and researchers would come closer to understanding participants’ motives in wanting to include a stronger content-focus in their practice. This exercise was discussed by the participants present during the final meeting in order to expand on the individual written reflections.

Table 2. Overview of the content areas included in participants’ teaching, and the core concerns expressed in their conference presentations and/or final reflections. Areas where content objectives are leading are marked in bold.

Data analysis

Data were analysed in Atlas ti 8.2, using a top-down coding method to identify answers to RQ1 and RQ2. RQ1 was addressed by identifying how the participants defined MFL ‘content’ and which content they employed in their teaching as part of the project. Part of this analysis involved identifying examples of whether and how these teachers’ ‘content’ related to the areas of Cultural Awareness and Language Awareness as proposed in the Integrated Curriculum displayed in . For RQ2, analysis focused on the core concerns or ‘problems’ that participants sought to address and the extent to which content-driven teaching helped them to do so.

During coding, it became apparent that the obstacles to or complications of a content-driven approach were of particular importance to teachers. This led to the formulation of RQ3. For the purpose of this RQ, data were coded for problems anticipated by participants prior to introducing content into their teaching and challenges actually encountered during the project.

Results and discussion

Due to the highly qualitative nature of this study, the results will be presented and discussed in one section, with regard to each research question in turn.

RQ1. How did participants understand ‘content’ in MFL?

Data related to participants’ responses to the idea of content in MFL were the beliefs and ideas expressed in group discussions, conference presentations and written reflections, and teachers’ reported use of content in their practice as a result of the project. Evidence of the latter was drawn from recordings of meetings, conference presentations, lesson materials and written reflections from the final meeting. These data were analysed with two sub-questions in mind:

Which content did teachers view as relevant to their subject?

How did teachers’ ideas and practices with regard to content relate to the areas of content proposed in the Integrated Curriculum?

Ideas on MFL-content

The concept of ‘content’ in MFL was discussed at length in the early project meetings. The purpose of these discussions was not to convince participants of the value of MFL content as described in the literature review but to explore what they considered to be relevant content for their subject and the form they saw this taking in their teaching. Concrete areas of content mentioned by participants in initial discussions (Meetings 1 and 2) were:

Culture, in terms of how people in a specific TL society live

Cross-curricular projects in collaboration with colleagues in other departments (e.g. History)

Content relating to learners’ daily lives

More often, ideas about which content might be covered remained broad, addressing general principles rather than concrete topics or learning outcomes. Examples of these principles are:

Content should be relatable to the experiences of pupils

Content should contribute to encouraging authentic communication

Knowledge on appropriate language use is also a form of content

‘All communication has content’ (Eelco) and can be used as a vehicle for communication in the language learning context

In a similar vein to Eelco’s comment, Tracy mentioned drawing content from the level descriptors in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), which refer to the areas about which a language user should be able to communicate:

So what is my subject about? It definitely depends on the CEFR level. So, ehm, A2 is describing a house and that can go in a lot of directions. But B1 or B2 levels, that’s of course looking a bit further afield. (Tracy, Meeting 2)

The idea that all communication contains content contradicts the Integrated Curriculum proposal discussed in the literature review, which advocates meaningful content learning centred around concrete learning objectives (Meesterschapsteam mvt, Citation2018). Teachers involved in the current project were not all convinced that objectives for content-learning were necessary, some of them viewing content more as a vessel for language learning than a focus of learning in itself. The same view was echoed at the end of the project:

Can you always attach a learning objective to everything you do in a lesson? (Paul, final reflection)

It is interesting to note in this comment echoes of CLIL subject teachers cited elsewhere, who teach through the TL but do not deliberately include learning objectives for language (e.g. van Kampen et al., Citation2017; van Kampen et al., Citation2018). In the current study, however, the language focus is explicit while content learning is viewed as incidental.

Reported practices and reflections

The content employed by the teachers in their teaching, summarised in , largely reflected the ideas discussed at the beginning of the project. While not included in the research questions, it is interesting to observe this lack of change, which could suggest that their beliefs are deeply ingrained. also includes the core concerns regarding their teaching that participants felt they addressed through participation in the project. The core concerns will be discussed in relation to RQ2.

Areas highlighted in bold in are those that relate to content objectives: in other words, learning objectives that focus on the learning of specific content. For Eelco and Els, content was closely connected with the Cultural Awareness aspect of the Integrated Curriculum in the sense of learning about a specific TL cultural group (German or Italian) beyond learning facts from a textbook. They wanted to address this content because they felt that knowledge of the TL culture was essential to language learning and its ultimate goal of ICC. Both of them expressed an interest in the importance of ICC. Some of Denise’s content areas also related to a specific TL culture (French-speaking France) and she, like Eelco and Els, included content areas in her learning objectives (e.g. Les objectifs de contenu: Tus connais les habitudes alimentaires des Français, exam-training lesson materials, Denise). She explained the process of identifying learning objectives in her final reflections:

For every lesson, I think of content goals and language goals. The content goals often lead into the language goals automatically. How can you talk about ‘the greatest Frenchman of all time’ if you can’t use comparatives?

Unlike Eelco and Els, however, her main goal in including content objectives (see ) was to engage learners in the language-learning process by offering them interesting content to communicate about while becoming familiar with aspects of the culture (as can be seen through the use of the verb connaître – to be acquainted with – rather than a can-do statement in the objective cited above). In this regard, content was a means rather than an end in itself.

In all three of the above cases, there appeared to be an implicit assumption regarding which culture should be the focus of the content: for Eelco, the focus was on Germany (adopting a second identity with an address in a German city), for Els, on Italy (e.g. Italian coffee culture), and for Denise, on France (e.g. proposed abolition of the Bac). As Els explained to the group following a needs analysis survey of her adult learners of Italian, travelling to Italy was their reason for following the course. For her, it was, therefore, logical to focus on the culture of Italy. The reasoning behind Eelco and Denise’s decision to focus on a particular TL culture was less clear, and the fact that it was not discussed might suggest that the choice of target culture was considered a ‘given’. The element of Cultural Awareness proposed in the Integrated Curriculum is positioned broadly, and does not refer specifically to a single TL culture for any language. This leaves scope to address culture as a broader, more global concept that contributes to learners’ development as plurilingual and interculturally competent citizens (Meesterschapsteam mvt, Citation2018).

Eelco’s approach to content, in particular, appeared to focus on the contribution of Cultural Awareness to ICC. His objectives went beyond cultural knowledge, thinking also in terms of attitudes and skills, and of understanding another perspective. His lessons involved learners adopting a ‘second identity’ based on research into ways of life in Germany, and approaching tasks from the perspective of this German alter-ego. His conclusion at the end of the project was:

There is always content, but perspectives on content vary. (Eelco, final meeting)

In the final project meeting, Eelco expressed a plan to continue his exploration the following school year by encouraging learners to engage on a deeper level with their second identity:

They didn’t go deep enough. So I have made some improvements and I think I can force them to go deeper. But gently. (Eelco, final meeting)

This year his lessons had focused largely on elements of daily life, although the following year he hoped to address questions of beliefs and values, for example through encouraging learners to discuss issues or moral questions from the perspective of their second identity.

While Eelco’s approach aligns with the Integrated Curriculum in positioning ICC as the central goal of MFL, in Eelco’s view, it appeared that development of new perspectives was not an aspect of content in itself. This leads to the question of whether content in MFL refers only to knowledge or also to attitudes, skills and values.

As the bold markings in highlight, while the presence of content in some form played an important role in Paul and Patty’s teaching, specific content or content objectives beyond ‘expanding their general knowledge’ (Peter, final reflections) did not appear to inform the planning of their lessons:

you have a language and […] you want to give it some substance in the lesson. (Patty, first project meeting)

In this sense, it is possible that the change to these teachers’ practice was to provide stimulus for learners to engage with content that they found appealing and about which they wanted to communicate, rather than positioning content as a learning goal in itself.

Furthermore, as evidenced by the question driving Paul’s participation in the project (‘How can I make sure that a presentation in French is connected to the everyday lives of leaners?’ – Paul’s conference presentation), it can be noted that the interests of learners were of central importance to him, whereas this is not explicitly mentioned in the Integrated Curriculum as presented in .

Forms of content present in the Integrated Curriculum but not represented in the data beyond brief comments were cultural artefacts such as literature and film (suggested under Cultural Awareness), and any areas related to Language Awareness, such as linguistics, language acquisition or language in society. It was not clear whether lack of attention to these areas was due to their not being considered appropriate content for MFL, not being considered interesting, or not being the teachers’ areas of expertise.

RQ2. What is the relationship between language-related content and the real concerns of teachers?

The second research question was addressed in two ways. Firstly, recordings of meetings, conference presentations and written reflections were analysed to identify reasons given by teachers for joining the project, and their concerns and preoccupations regarding their practice. Secondly, discussions and written reflections regarding the role of content in MFL were analysed in order to identify the extent to which teachers appeared to engage with the idea of a content-driven MFL curriculum. Unlike RQ1, the latter did not focus on the roles of the specific content areas proposed in the Integrated Curriculum in , but on the idea of the integration of any content into the MFL curriculum.

Teachers’ concerns

Throughout the course of the project, and on the basis of discussion and reflection regarding their teaching, teachers’ concerns regarding their practice became more clearly defined. During the early meetings, reasons given by participants for joining the project were varied and overlapping. Prominent themes included:

An assignment given by school to investigate ways to implement formative assessment (Denise)

Engage pupils/Escape boring curriculum, while also meeting the requirements of the final examination (Paul, Denise, Patty, Tracy)

Establish a more authentic context for communication in the TL (all)

Lower pupils’ inhibitions when speaking or writing in the TL (Tracy, Patty)

Improve teaching without becoming overworked (Patty)

Encourage pupils to take more responsibility for their own learning (Patty, Paul)

Make cultural content more meaningful (Eelco, also echoed implicitly by others)

Increase learners’ cultural awareness with the aim of making them more effective communicators in the TL (Eelco, Els)

Several of these areas echo commonly claimed advantages of CLIL and other content-based approaches to language teaching (Mearns, Citation2015). It, therefore, seems logical that these teachers were drawn to a content-focused approach.

As highlighted in , many of the above goals were still prominent by the end of the project and some, namely Eelco’s and Els’s, related directly to the approach to content employed by the teacher. While Denise’s core concerns did not appear directly related to content, they were connected to the washback effect prominent in the current curriculum’s emphasis on a centralised reading examination based largely on multiple-choice questions. Her use of learning objectives for content to make compulsory exam training more meaningful appeared to have the desired effect of increasing not only her learners’ engagement but also her own:

What I found most refreshing was that I began to find preparing my lessons fun once again and that I had active students in the class. (Denise, final reflections)

Paul and Patty also succeeded in developing their practice in the areas they identified as their core concerns, as illustrated by Paul in his conference presentation:

Pupils enjoyed being able to choose their own topic for the presentations, and the presentations they gave were very varied. I am happy with the process up to this point.

Paul had identified engaging learners as one of his main priorities. Based on this statement, his intervention appeared to help him meet this goal. Likewise, Patty, who had aimed to reduce anxiety and rote-learning around oral examinations, reported precisely these effects. In these cases, however, it is questionable whether the MFL content was really the solution to the problem. For Paul, it appeared to be the act of listening to learners and taking their views on board that helped to improve their enjoyment of French. In Patty’s case, relinquishing the textbook in favour of authentic materials appeared to have the greatest effect.

Engagement with content

Throughout the project, it appeared that there was some discrepancy between the facilitators’ and participants’ concerns regarding the role of MFL content. The Integrated Curriculum focuses on identifying appropriate content for the curriculum and provides as yet little indication of how the integration of content and language might practically be achieved. Initial discussions between participants, however, rarely rested on the question of which content might become the focus of lessons but returned frequently to questions around promotion of language proficiency or grammar. Furthermore, in general, there was more discussion around the ‘how’ aspect of content-language integration than around the ‘what’. For example, two teachers (Els and Denise) decided by the end of the project to delve deeper into the integration of content by reading or seeking professional development about CLIL. Their enthusiasm had been sparked but, again, the question of which content was less important to them than that of how it could be used. This could suggest a mismatch between the priorities of academics and policy-makers, and those of these teachers.

RQ3. What were the perceived obstacles to MFL content?

This question was not originally included in the research design but was added during coding due to the frequent references to areas of uncertainty or apprehension and, in later meetings, difficulties encountered in implementing changes. Results are drawn from discussions from both the beginning and end of the project, conference materials and written reflections.

summarises the challenges anticipated by participants during initial discussions regarding a content-focused approach to MFL as well as the challenges they actually experienced and the questions that participation in the project raised regarding the introduction of a content-rich MFL curriculum. The majority of these challenges focused on the micro (classroom) level, although some of the anticipated challenges and the questions raised referred to factors on meso (school/departmental) and macro (societal/policy) levels.

Table 3. Anticipated and experienced challenges, and questions raised regarding the prospect of content-rich MFL, classified as micro (classroom), meso (department/school) or macro (societal/political) level.

The micro-level challenges were largely issues that are well-known in CLIL contexts, such as teacher workload, TL use and assessment and balancing cognitive and language levels (Coyle et al., Citation2010). This could indicate that professional development in CLIL would align with the challenges faced by MFL teachers integrating content and language for the first time. Other micro-level concerns, however, such as familiarity with content areas and with content-specific discourse are issues that are specific to the MFL CLIL classroom, in which specific content knowledge has until now not been a priority.

Most meso-level reservations voiced early in the project did not return in discussions at the end. Several teachers appeared to have found a way to work around the anticipated limitations posed by department policy. For example, Paul transformed the scheduled assessment (a presentation) into an opportunity for learners to engage with the language and content that was important to them. Els, tied to a textbook that her adult students had been required to buy for their evening course, opted to set textbook activities as homework, leaving more room to address cultural content during lessons. Denise, who felt demotivated at having to train learners for their final reading exam, transformed past exam texts into content by grouping them thematically and integrating them with explicit content-learning based on learning objectives.

The first of the macro-level challenges highlights that the concept of content and language integrated MFL remained vague to participants at the end of the project. Furthermore, teachers were wary of the idea that MFL content might be prescribed on a national level. This reservation took into account not only the question of public support but also the effect that this would have on the role of the teacher and on the learner’s interest in the subject. Like the teachers in Kaal’s (Citation2018) study, participants in this project enjoyed the freedom offered by the existing curriculum. With curriculum outcomes focused largely on language proficiency, teachers are free to select the content that is most appealing to them and their learners, and to use this content as a vehicle for language learning without concern for content learning. For these teachers, this was partly what they enjoyed about engaging in this project. They appeared to see little need to assign MFL content a stronger position.

Limitations of this study

A goal of the current project was to allow teachers to form their own views and experiment with their own practices regarding MFL content, rather than to test a theory or model of what this should look like in practice, or of its effectiveness. Research that aims to do the latter would be better served by a more directive approach.

Conclusions and implications for research, policy and practice

This study sought to investigate MFL teachers’ response to the proposal to refocus the curriculum outcomes for MFL towards the integration of language learning and the learning of meaningful language-specific content. It explored teachers’ own understandings of which content was most relevant to their subject teaching, and the relationship between these ideas and the areas of MFL-specific content suggested in the Integrated Curriculum model (see ) under the broad categories of Cultural Awareness and Language Awareness. While this was a highly localised and small-scale study, which grew out of local needs and political developments in the Dutch context, the delicate status of modern languages in the curriculum is a Europe-wide problem (Rádai et al., Citation2003). It is hoped that the conclusions presented here, while undoubtedly context-bound, might also serve as inspiration in international contexts faced with similar issues.

In terms of the forms of content that might be addressed in MFL, teachers’ views did not consistently align with the domains of Cultural Awareness and Language Awareness as proposed in the Integrated Curriculum. Language Awareness was not considered at all. This could imply that this is not considered appropriate content by teachers or that they are not aware of what it might entail. Cultural Awareness – in the sense of familiarity with customs from the TL-culture – held a prominent position for some teachers, although other elements of culture, such as media or the arts, did not feature. ICC, which the Integrated Curriculum positions at the heart of MFL, featured prominently for one of the teachers, although he did not appear to see this as an area of content-learning in itself. In this respect, the question was raised as to whether ‘content’ refers only to knowledge and understanding or also to the development of skills, attitudes and values. Furthermore, it appears that the concept of cultural awareness was associated with learning about dominant TL cultures (of Germany, France and Italy) and not with exploration of culture as a global phenomenon.

In terms of teachers’ priorities, it seemed that the central goal of content was that learners had something to communicate about. They did not always feel that there was a distinction between language skills and content, nor that this mattered, and were more concerned with execution than with content itself. This study also provided insight into some of the obstacles that might be perceived or experienced by teachers regarding the implementation of a content-rich MFL curriculum, on macro, meso and micro levels. An important finding in this regard was that teachers, although enthusiastic about incorporating content into their lessons, were wary that assigning content an official role in the curriculum would stifle both their freedom and that of pupils.

Together, these findings could indicate that major curriculum reform in the direction of a content and language integrated MFL curriculum in the Netherlands, as suggested in the Integrated Curriculum, could struggle to gain support from teachers. It will be important for such proposals to be explicit with regard to the proposed MFL content areas while also leaving space for teachers – and pupils – to cover content in ways appropriate to their needs and their contexts. In light of the apparent mismatch between the focus of practitioners on how to teach effectively and of policy-makers on what to include in the curriculum, clear vision with regard to the implementation of the Integrated Curriculum on a classroom level, clear practical examples and tailored training in approaches such as CLIL as well as with regard to the content itself will be required in order for the proposed reforms to succeed. It will also be important to emphasise that a content-driven approach to MFL does not aim to displace the communicative element of the subject, but rather to support it.

As highlighted by these teachers’ uncertainties regarding how effective content and language integration can be achieved, and potential gaps in their content knowledge, further research is required in order to identify teachers’ needs in terms of professional development as well as the most appropriate ways in which to implement such changes in line with the existing knowledge, skills and priorities of teachers. While CLIL training as provided for non-language teachers in bilingual education might suffice in some respects, MFL CLIL teachers may require additional training more tailored to their needs. Inspiration for pedagogical training might be drawn from models in Anglophone contexts such as Australia and the UK, where CLIL is often led by MFL teachers in classes with lower levels of proficiency (e.g. Cross, Citation2016; Mearns, Citation2012), while content-focused training may need to be developed specifically for the context of MFL content. Language Awareness as a potential curricular focus may require particular attention as it appears to be furthest from teachers’ consciousness. Furthermore, exploration of teachers’ interpretations of cultural awareness in both local and global terms would be beneficial to the further development of the Integrated Curriculum model and to its implementation. Finally, while the current study focused on teachers’ voices, the voice of learners should not be forgotten. As Paul wrote in his final reflection:

As a teacher, if you have access to the way in which the learner experiences the world, you can make sure that the content hits home.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible with funding from Vakdidactiek Geesteswetenschappen and the inspiring contributions from the participating teachers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bloemert, J., Jansen, E., & van de Grift, W. (2016). Exploring EFL literature approaches in Dutch secondary education. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2015.1136324

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters.

- Council of Europe. (2018). The common European framework of reference for languages (CEFR). https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/table-1-cefr-3.3-common-reference-levels-global-scale

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge University Press.

- Cross, R. (2016). Language and content ‘integration’: The affordances of additional languages as a tool within a single curriculum space. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 48(3), 388–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2015.1125528

- Dalton-Puffer, C., Llinares, A., Lorenzo, F., & Nikula, T. (2014). “You can stand under my umbrella”: Immersion, CLIL and bilingual education. A response to Cenoz, Genesee & Gorter (2013). Applied Linguistics, 35(2), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu010

- Graus, J., & Coppen, P.-A. (2016). Student teacher beliefs on grammar instruction. Language Teaching Research, 20(5), 571–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168815603237

- Hüttner, J., Dalton-Puffer, C., & Smit, U. (2013). The power of beliefs: Lay theories and their influence on the implementation of CLIL programmes. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2013.777385

- Kaal, A. (2018). Mvt-onderwijs nu en in de toekomst. Opvattingen van docenten en vakdidactici. https://modernevreemdetalen.vakdidactiekgw.nl/mvt-onderwijs-nu-en-in-de-toekomst/

- Kemmis, S. (2007). Participatory action research and the public sphere. In P. Ponte & B. H. J. Smit (Eds.), The quality of practitioners research. Reflections on the positions of the researcher and the researched (pp. 9–27). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789087903190_003.

- Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J. M. (2009). Language attitudes in CLIL and traditional EFL classes. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(2), 4–17. http://www.icrj.eu/index.php?vol=12&page=73

- Mearns, T. (2012). Using CLIL to enhance pupils’ experience of learning and raise attainment in German and health education: A teacher research project. The Language Learning Journal, 40(2), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2011.621212

- Mearns, T. (2015). Chicken, egg or a bit of both? Motivation in bilingual education (TTO) in the Netherlands [Unpublished PhD thesis]. University of Aberdeen. http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.646095?

- Mearns, T., & de Graaff, R. (2018). Bilingual education and CLIL in the Netherlands. The paradigm and the pedagogy. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1075/dujal.00002.int

- Mearns, T., de Graaff, R., & Coyle, D. (2017). Motivation for or from bilingual education? A comparative study of learner views in the Netherlands. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1405906

- Meesterschapsteam mvt. (2018). Visie op de toekomst van het curriculum Moderne Vreemde Talen (Vakdidactiek Geesteswetenschappen Ed.). Vakdidactiek Geesteswetenschappen.

- Mulder, P. (2012). 5 whys analysis. https://www.toolshero.com/problem-solving/5-whys-analysis/

- Ponte, P., & Smit, B. H. J. (2007). Introduction. Doing research and being researched? In P. Ponte & B. H. J. Smit (Eds.), The quality of practitioners research. Reflections on the positions of the researcher and the researched (pp. 1–8). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789087903190_002.

- Rádai, P., Bernaus, M., Matei, G., Sassen, D., & Heyworth, F. (2003). The status of language educators.

- Ruiz de Zarobe, Y. (2013). CLIL implementation: From policy-makers to individual initiatives. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2013.777383

- Schat, E., de Graaff, R., & van der Knaap, E. (2018). Intercultureel en taalgericht literatuuronderwijs bij de moderne vreemde talen; Een enquête onder docenten Duits, Frans en Spaans in Nederland. Levende Talen Tijdschrift, 19(3), 13–25. http://www.lt-tijdschriften.nl/ojs/index.php/ltt/article/view/1841

- Stichting Leerplanontwikkeling. (2013). Examenprogramma moderne vreemde talen en literatuur havo/vwo.

- Sylvén, L. K. (2007). Are the Simpsons welcome in the CLIL classroom? Vienna English Working Papers, 16(3), 53–59. https://anglistik.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/i_anglistik/Department/Views/Uploads/Views_0703_specissue.pdf

- Ting, Y. L. T. (2010). CLIL appeals to how the brain likes its information: Examples from CLIL-(neuro)science. International CLIL Research Journal, 1(3), 3–18. http://www.icrj.eu/13/article1.html

- van den Broek, E., Oolbekkink-Marchand, H. W., Unsworth, S., van Kemenade, A. M. C., & Meijer, P. C. (2018). Unravelling upper-secondary school teachers’ beliefs about language awareness: From conflicts to challenges in the EFL context. Language Awareness, 27(4), 331–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2018.1523910

- van Driel, J., Beijaard, D., & Verloop, N. (2001). Professional development and reform in science education: The role of teachers’ practical knowledge. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(2), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2736(200102)38:2<137::AID-TEA1001>3.0.CO;2-U

- van Kampen, E., Mearns, T., Meirink, J., Admiraal, W., & Berry, A. (2018). How do we measure up? A review of Dutch CLIL subject pedagogies against an international backdrop. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 129–155. https://doi.org/10.1075/dujal.18004.kam

- van Kampen, E., Meirink, J., Admiraal, W., & Berry, A. (2017). Do we all share the same goals for content and language integrated learning (CLIL)? Specialist and practitioner perceptions of ‘ideal’ CLIL pedagogies in the Netherlands. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism . Online first. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1411332

- Westhoff, G. (2012). Mesten en meten in leesvaardigheidstraining. Leesvaardigheidsonderwijs en examentraining zijn twee verschillende dingen. Levende Talen Magazine, 4, 17–21. http://www.lt-tijdschriften.nl/ojs/index.php/ltm/article/view/421