ABSTRACT

The principle-based approach is at the heart of the inspection philosophy of the Netherlands Inspectorate of Education. In this paper, we present the results of complementary qualitative and quantitative studies analysing the impact of this approach. In the first study, we apply a system dynamics approach to provide insight on the impact of the principle-based approach in schools. The second study builds on these findings and uses quantitative survey data to “test” the various ways and mechanisms by which the respondents perceived principle-based approach affects schools. Together, these complementary studies provide a deeper understanding of the impact of the principle-based inspection approach on educational quality and beyond. Overall, we find positive effects of the principle-based approach. The qualitative study reveals variation in mechanisms within schools that affect educational quality. These findings appear to be robust in our quantitative analyses; the effect sizes are small and curvilinear.

Introduction

From 1 August 2017, the inspectors of the Netherlands Inspectorate of Education in primary, secondary, and senior secondary vocational education work in accordance with a renewed inspection framework. This framework builds on the legal responsibility that school boards have for the educational quality in the schools they govern. To do justice to the responsibilities of school boards, the inspectorate’s new working approach provides instruments to hold boards accountable. This also means that school boards have become the direct point of contact for inspectors. This shift reveals a stronger focus on board capacity, while simultaneously trying to balance this with a focus on processes and performance in individual schools.

The policy theory underlying the renewed inspection approach includes assumptions about the means and mechanisms to achieve the intended ambitions in schools to strengthen educational quality. As a result, the nature of the Inspectorate’s approach has shifted to a principle-based one. This implies a reframing of the regulatory relationship from one of directing and controlling to one based on responsibility, mutuality, and trust (Black, Citation2008). Mechanisms like providing feedback to the board and its schools are expected to lead to quality improvement of the board and its schools. These ambitions of stimulating and encouraging further improvements require inspectors to attune to school boards and to start from guidelines instead of imposing a rigid framework. The inspectorate is also expected to attune to the school’s board and to offer it room to present its own vision. This reflects a different style of working, and it challenges the theories and practices traditionally used by school boards to increase the educational quality in the schools they govern. How this works in practice is not yet clear, however, because so far we lack solid evidence about the relation between school boards and educational quality (Honingh et al., Citation2020).

In this paper, we study school boards’, school leaders’, and teachers’ experiences with the renewed working approach of the Inspectorate of Education in primary and secondary schools, to determine and evaluate whether and how this approach affects educational quality. Our main question is: What is the impact of the principle-based inspection approach on educational quality and beyond?

Policy theory

Dutch national educational policy explicitly identifies school boards as ultimately responsible for guaranteeing educational quality (Staatsblad, Citation2010). To ensure that school boards play their part, legal requirements, codes of conduct, and inspection frameworks stress the responsibility that boards have for educational quality, quality assurance, and financial management. Although this responsibility is relatively easy to understand from a legal point of view, it raises questions about the direct, indirect, and sometimes distant contribution that boards could make to educational quality. Here, it is important to realize that most schools are governed in multiple-school arrangements, particularly at primary and secondary level (Hooge & Honingh, Citation2014; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2016). Despite these questions, the renewed inspection approach builds on the idea that school boards are themselves motivated and able to improve the quality of education in their schools (self-regulation). The inspectorate has to encourage boards and schools to continuously improve and perform beyond the standards. Central to the policy underlying the renewed inspection approach is a set of assumptions about the means and mechanisms to achieve the intended ambitions to strengthen educational quality (Inspectie van het Onderwijs [IvhO], Citation2017).

To offer school boards enough room to develop their own strategy and quality assurance structure, the inspectorate’s detailed indicators have been replaced by a list of key points. In addition to enforcement, the inspectorate must focus explicitly on quality improvement and school self-reflection. This entails a principle-based approach and therefore a reframing of the regulatory relationship, changing the inspection practice considerably for supervisors, school boards, school leaders, and teachers. In contrast to previous approaches, the inspectorate now explicitly acknowledges that boards and their capacities differ from each other in many respects and that they operate in different contexts. The inspectorate assesses the aggregated school data and asks the board executives how they assess their own quality, and whether and how they achieve their goals. These expectations are crucial in the inspectorate’s research framework (IvhO, Citation2017). Given local and administrative contingencies, inspectors have to give boards enough space to attune their activities to their own regional context, while taking into account the differences between the schools they govern. The renewed inspection approach is designed to attune to “the current state of competence of the board, the board’s ambitions, visions and the risks in schools given the results of internal quality assurance instruments and school development” (IvhO, Citation2017, p. 9).

Another key mechanism in this renewed inspection approach is the feedback given to the board and schools, consisting of an assessment of the quality assurance and financial continuity at board level. Feedback to boards and schools is expected to strengthen their reflective capacity and enhance their quality improvement.

Looking at the presented mechanisms and underlying assumptions, we notice a clear ambition of the inspectorate to actively contribute to a culture of quality in the schools and their boards, in order to encourage them to raise educational quality and continuously invest in quality improvement. These ambitions of stimulating and encouraging further improvements require inspectors to attune to school boards and to start from guidelines instead of imposing a rigid framework.

Theoretical background

From a theoretical stance, the renewed working approach of the inspectorate reveals aspects of a full principle-based approach (PBR; Black, Citation2008). Full PBR means that regulators set standards using “general, broadly stated rules or ‘principles’” (Black, Citation2008, p. 435) and requires particular behaviour or practices of both regulator and regulatee (Black, Citation2008, p. 439). In the inspectorate’s new working approach, we discern two sets of regulatory practices: a persuasion-based enforcement approach and reliance on meta-regulation. A persuasion-based enforcement approach assumes that regulatees (here, school boards) are intrinsically motivated to comply with the rules and improve themselves. In this approach, a regulator (inspector) takes a preventive approach through collaboration and negotiation with the regulatee, rather than a repressive approach of controlling and sanctioning (Hawkins, Citation1983). Compliance occurs when a regulatee agrees with the rules (Kagan & Scholz, Citation1984). The regulator may encourage this in a variety of ways. First, by providing tailor-made or case-by-case solutions, which means that the application of rules is determined by first investigating the regulatee’s individual situation (Hickman & Hill, Citation2010; Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012). Second, by ensuring that the regulatee feels recognized by having an open conversation and giving constructive feedback (Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012).

However, when this approach does not lead to compliance, a regulator may take a responsive enforcement approach and still sanction the regulatee (Ayres & Braithwaite, Citation1992; Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012). The importance of both giving relevant, specific, and useful feedback and differentiating in regulation has been corroborated in studies on the relationship between educational supervision and educational quality (Ehren, Citation2016).

A persuasion-based enforcement approach, however, is not always effective. First of all, there is a risk of a too-close relationship between regulator and regulatee (Gunningham, Citation2010; Hawkins, Citation1983; Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012). This can result in lax compliance by the regulatee (Bardach & Kagan, Citation1982; Gunningham, Citation1987) or in “negotiated non-compliance” (Gunningham, Citation1987, p. 91). The latter means that a regulator may withdraw completely from enforcement activities in order to maintain a good relationship with the regulatee. Calculating regulatees may take advantage of this (Kagan & Scholz, Citation1984). Second, the credibility problem may occur, as the discretionary room of the regulator may lead to unpredictability in the behaviour of the regulator and uncertainty among regulatees (Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012). This may undermine compliance.

The second regulatory practice is meta-regulation. This strategy means that regulators focus on “regulating at a distance” (Gunningham, Citation2010) by encouraging and ensuring regulatees to have their own rules, systems, and processes in place (Black, Citation2008; Gunningham, Citation2010). In the case of schools and in the new working approach of the inspectorate, this relates to the responsibility that school boards have for quality assurance systems and financial management. Meta-regulation relies on the idea of self-regulation and organization learning (Argyris & Schön, Citation1978). It encourages regulatees to reflect on their own performance and compliance with the rules, and to demonstrate that their systems and processes work (Gunningham, Citation2010). This approach may be an effective way forward for complex organizations like schools, but it has limitations as well. For example, there is the risk of having a sound system and processes on paper but not in reality (Gunningham, Citation2010). Helderman and Honingh (Citation2009) point to complexity in the external environment and a long chain of interdependencies that may reduce the motivation for self-regulation.

So far, the extant literature clearly indicates that the effects of full PBR are not straightforward; this approach can therefore not be seen as a panacea (Black, Citation2008). Its impact depends on the characteristics of the regulator as well as those of the regulatee. Regulators have to deal with information asymmetry, relational distance, and issues of measurability and enforceability (Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012). They need adequate resources, competencies, and expertise to regulate effectively (Black, Citation2008; Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012; Reiman & Norros, Citation2002). Compliance of regulatees depends on organization size (i.e., organizations’ resources, capabilities, and capacities) and on their motivation (i.e., whether they are rational, reluctant, recalcitrant or incompetent) (Baldwin & Black, Citation2008; Braithwaite, Citation1995; Gunningham, Citation2010). Those who are differently motivated are likely to respond very differently to regulation (Gunningham, Citation2010). This means that regulation should be carefully targeted – there is no single approach (Baldwin & Black, Citation2008; Gunningham, Citation2010; Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2012) – and that it can prove counterproductive, due to a culture of regulatory resistance and a defensive stand of regulatees, and to withholding information.

Study overview

The remainder of this paper presents the results of two complementary studies, in which we analyse the impact of the renewed inspection approach in Dutch schools for primary and secondary education. In Study 1, the aim was to identify the mechanisms through which PBR affects schools by using a qualitative inductive systems dynamic approach. In Study 2, building on the findings from Study 1, the aim was to test the mechanisms using quantitative survey data. Taken together, the two studies provide empirical evidence of how PBR has an impact in primary and secondary schools.

Study 1: group model building

Method

Principle-based inspection is a new phenomenon in Dutch primary and secondary education. To avoid overlooking its (unintended) effects, we decided to start with an inductive study. Instead of jumping to a research design that tests whether expectations from the existing literature hold in our case, we wanted to hear from practitioners which variables they deem relevant to understand the impact of principle-based inspection. This allows us to find unexpected and unintended effects of the renewed inspection approach that are not yet covered by earlier studies.

Therefore, in the first study, we chose participative modelling as our research strategy, which revolves around open and divergent group discussions with practitioners (Richardson & Andersen, Citation1995; Vennix, Citation1999). We adopted a group model building approach, where group discussions are structured in terms of the process (details are described later in this section), but where the content of the discussion can diverge based on the input of participating practitioners. We organized 10 workshops, lasting about 3 hours each, carried out by the same team of three researchers (three of the authors of this paper). One facilitator led the group discussion, one modeller changed the model presented on a screen based on the group discussion, and one recorder made notes (https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Scriptapedia/Roles_in_Group_Model_Building). Workshop participants – 79 in total – all worked in the same organization (see ). Depending on the scale of the school, participants were members of the board, board secretaries, directors, team leaders, teachers, and quality managers.

Table 1. Group model building workshop participants.

School boards were randomly selected. On the basis of the inspectorate’s planning file, it was clear which school boards had experience with the principle-based inspection method. From that group, random school boards were approached with the request to participate in our study. Usually, contact was made by telephone with one of the board members or quality managers. During the conversations, an explanation was given about the intention and set-up of the group model building workshops. The workshops (W1–W11) took place in two rounds between January 2018 and February 2020. The workshop process consisted of three steps (based on Hovmand et al., Citation2012):

| (1) | Reference mode of behaviour. In the first step, participants described the development of educational quality over the past 5 years and developments they would expect in the future. | ||||

| (2) | Building the educational quality model. The second step involved building a causal loop diagram (de Gooyert, Citation2019): a diagram showing the various causal relationships between variables, including their polarity, using a plus sign for a positive causal relationship and a minus sign for a negative one. Closed circles of causal relationships are identified as either a balancing feedback loop (a mechanism where an initial increase of a variable will lead, via the other variables, to a decrease of that same variable) or a reinforcing feedback loop (a mechanism where an initial increase of a variable will lead, via the other variables, to a further increase of that same variable). In the first round (Workshops W1, and W2), this causal model was built on the basis of a very small seed model (https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Scriptapedia/Causal_Mapping_with_Seed_Structure) comprising three factors (teaching quality, quality assurance, and financial management) derived from the inspectorate’s framework. Each of the participants was then asked to write down variables they consider relevant in the context of educational quality, followed by eliciting these variables in a round-robin fashion, resembling the “Nominal Group Technique” script (https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Scriptapedia/Nominal_Group_Technique). This stage can be seen as the construction of a dynamic hypothesis for the reference mode behaviour as identified in the first stage. In the second round (W4–W11), we started with the summarizing model of the first round of workshops. | ||||

| (3) | Adding the impact of inspection. Only after a satisfactory model of the education quality system had been finished, in the third step (which was the same in both rounds of workshops), did we go to our follow-up question: How does the inspectorate affect the system of school quality? The facilitator led a group discussion guided by this question. The modeller translated the discussion into an extension of the educational quality model. | ||||

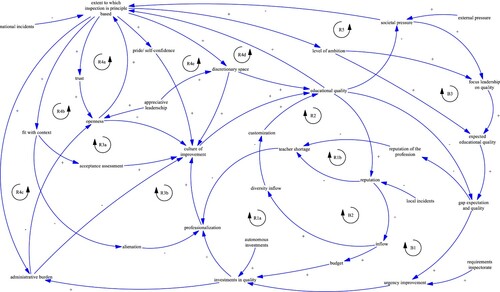

In this study, we aimed for general insights into the impact of the inspectorate, not for idiosyncrasies of individual cases. Accordingly, the summarizing model only shows those mechanisms that were reported in at least two workshops (de Gooyert & Größler, Citation2018). Anonymous versions of the models that resulted from the individual workshops can be obtained from the authors. The summarizing model shows (a) the system behaviour of schools to achieve educational quality, and (b) to what extent and how the inspectorate and its working methods affect that system.

Results

In the group model building sessions, respondents said that educational quality is mainly driven by the diversity of pupils, the discretionary space to work on educational quality, and the extent to which there is a culture of improvement. A change in educational quality (positive or negative) can easily result in further change in the same direction through the reinforcing effect of reputation: the better the educational quality, the better the reputation, the more inflow of pupils and budget to further improve quality. Or the same mechanism in the opposite direction: the worse the educational quality, the worse the reputation, the less inflow of pupils and budget, leading to even lower quality. The respondents identified several mechanisms by which the inspection affects the educational quality system. It became clear that respondents differ in the extent to which they perceive a principle-based approach. The essence of principle-based working and the examples given by respondents show that they feel they are given space to tell their own story, and the inspector relies on a tailored approach during the visit: “Yes, I did experience a different attitude. Not just a question and answer, but a true exchange of ideas. This differed from previous visits.” The summarizing model in shows the mechanisms of how educational quality is achieved in schools and the loops that offer information about how schools experience the work of the inspectorate and how it affects educational quality. In the model, we distinguish four balancing loops (B1/ B1’, B2, B3 [B for balancing]) and eight reinforcing loops (R1a, R1b, R2, R3a, R3b, R4, R5, R6 [R for reinforcing]). As this paper focuses on the impact of the new working method of the inspectorate, here we will discuss in more detail only the loops about the inspectorate (R4 and R5).

Continuous improvement culture (R4)

The respondents indicated that the extent to which the inspectorate works in a principle-based way has several points of leverage. We therefore identify several routes from principle-based inspection to a continuous improvement culture.

Trust, connection, and acceptance (R4a and R4b)

When we look at the “trust” part of the loop R4, we observe that the more principle-based the inspectorate’s work, the more the school trusts the inspectorate’s working approach. Trust relates to how school board members are treated and expect to be treated by the inspectorate. If there is trust, this leads to more openness in contact with the inspectorate. The workshops show that openness is also relevant to a culture of continuous improvement:

But now you could indicate in advance in your presentation what your strong/weak points are. So you are more open. And a point of criticism was not an attack on what we did. (W5:210)

So the more transparent you are, the more insight the inspectorate gets into your own points of improvement of the school and schools. (W5: 233)

A principle-based inspection can also lead to a negative judgement, but then it is more constructive in tone and you also receive concrete suggestions for how things can be improved. Whereas with a rule-based style you have to deal with protocols and you only hear that something is not right. Principle-based has a kind of growth mindset, and you can do a lot more with it. (W7:159)

Respondents expressed the expectation that, if the school is doing well, the inspectorate is more inclined to carry out inspection in a principle-based manner. In the group model building sessions, this was expressed as follows: “I wonder whether they will fall back on rule-based working if the quality of education is not high enough” (W4:50).

Respondents see trust as a key aspect. Based on a relationship of mutual trust, the idea is that the inspectorate and the board engage in a dialogue on key topics. Paradoxically, however, respondents indicated that inspectors easily fall back into traditional routines, when they attempt to build trust by doing detailed assessments of long lists of indicators – which principle-based regulation was supposed to avoid. Apparently, regulation in a relationship of mutual trust requires substantial trust to be there in the first place, and when inspectorates only trust those boards that can show detailed descriptions of indicators, the principle-based approach can only be applied in those settings where educational quality was not problematic, while the culture of improvement that is needed to improve educational quality would benefit from a more open, principle-based approach. The paradox is that principle-based regulation ends up being applied only to those schools that do not need it.

Administrative burden (R4c)

Here we need to point at the fact that when it comes to administrative burden, respondents mainly elaborate on the consequences of a less principle-based approach. When the approach of the inspectorate is less principle-based, the respondents experience greater administrative burden, in the form of protocols and checklists. Following the loop, this ultimately contributes to their experiencing less space and does not improve the quality of education. Respondents describe a decrease of reflection in schools as a consequence of a less principle-based approach:

For example, making a test mould, that simply needs to be in place. Sure, you try to make the most of it to enhance educational quality. However, because of these requirements, our focus on educational quality tends to shift to the background. (W4:58)

Looking at some school boards, it looks like they try to map it out completely by filling one Excel after another. Expecting these documents to enhance their conversation with the inspectorate. I wonder whether these boards already expect a less principle-based approach and reduce openness. (W9:268)

Room to manoeuvre and pride (R4d and R4e)

The respondents indicated that if the working method of the inspectorate is more principle-based, then school members experience more room to manoeuvre. This affects educational quality directly and indirectly via a culture of continuous improvement: “I think that principle-based inspection leads to room for substantive discussions and then to quality improvement. And also insight into points for improvement” (W5:239).

Another chain is via pride or self-confidence. A principle-based approach leads to pride or self-confidence among school members, which in turn leads to a culture of continuous improvement, and from there to quality of education:

Yes, I just saw it happen. Schools receive direct feedback from the inspectors and they are simply very enthusiastic. They say, for example, that they can become an excellent school, and you just see teachers grow. So the next day, they are teaching even better. That’s a spiral upwards. (W10:179)

[…] schools have been told for years that their education was not good. Now we have a different form of inspection, and we have heard a lot more about what went well. That has really contributed to the quality of education, because now people have finally heard about what they are doing is good. There’s pride in that. (W10:181)

Ambition (R5)

At the top of the causal model in , we identify the “ambition” loop. This loop illustrates that there are also situations where, as a result of complaints about the quality of education or a lower quality of education, the inspectorate is perceived to a lesser extent as working in a principle-based way. The mechanism then is as follows, according to the workshop participants: the lower the quality of education, the more societal pressure (incidents), the less principle-based the inspectorate’s approach. This means they perceive an increase in the use of protocols, which leads to a greater administrative burden and less openness, which ultimately has negative consequences for the quality of education. This loop illustrates a self-reinforcing effect of poor educational quality in which the inspectorate is not succeeding at reversing this course of events.

This loop explicitly shows that national incidents may lead to a less principle-based approach. We notice a rule-and-control reflex as a result of an incident. Respondents refer in this context to the current focus on the PTA (Programme of Review and Conclusion). Compliance with rules and control seems to replace guidelines and therefore a principle-based approach. The following is an illustrative quote: “The political agenda. (… Then inspectors, their approach and the schools become rigid)” (W7:622).

Conclusion Study 1

In summary, previous description of the loops about the inspectorate, R4 and R5, points to multiple impact patterns that may vary. We often see positive effects of a principle-based inspection approach on school culture that subsequently seems to influence the quality of education. The question is, of course, to what extent the perceptions of the respondents are robust.

Study 2

The findings from Study 1 indicate that the inspectorate’s approach has an impact on schools in a variety of ways. In particular, its principle-based inspection approach is expected to work through various mechanisms: (I) perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact, (II) outcomes related to educational quality, and (III) outcomes related to school culture. The aim in Study 2 is to investigate to what degree the qualitative findings from Study 1 are corroborated by quantitative findings. We test the various mechanisms identified among a sample of primary and secondary schools. As these mechanisms may not be straightforward, we test both linear and curvilinear effects of principle-based inspection.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of school principals and teachers from Dutch primary and secondary schools who recently had experienced inspection based on the renewed inspection framework. As the Dutch inspectorate started applying the renewed inspection framework in August 2017, we distributed identical surveys in two rounds during September–December 2018 and September–December 2019 to increase the number of respondents. At the time of distributing the survey, each respondent had experienced the renewed inspection once and within 1 year of filling out the survey. In total, 901 people responded, although the number of cases used in the analyses is smaller, due to unanswered survey questions. Of the total cases, 68% worked in primary schools, 58.3% as a teacher, and 53.4% responded in the second round.

Measures

All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree); see Appendix 1. The items and scales used in this study are based on the policy theory described earlier and the first few workshop sessions of Study 1. While our items lack usage in previous research, this approach allowed us to develop items that are closely in line with the practical reality of the respondents, which, in turn, improves comparability across Studies 1 and 2. To validate our scales, we performed maximum likelihood exploratory factor analyses with direct oblimin rotation for the items that reflected one of the three outcomes perceptions of inspectorate’s impact, educational quality outcomes, or school culture outcomes. Appendix 2 shows the factor loadings from these analyses.

Perceptions of inspectorate’s impact

Three dependent variables were used that reflect the respondents’ perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact. First, effective feedback reflected the degree to which feedback from the inspectorate was perceived as effective. It was measured using four items (α = 0.84). Second, bureaucracy reflected the degree to which inspection leads to administrative burdens. It was measured using four items (α = 0.73). Third, use of inspectorate’s directions reflects the degree to which directions from the inspectorate were used in school. It was measured using two items (Spearman-Brown coefficient ρ = 0.87).

Educational quality outcomes

Four dependent variables were used that reflect outcomes related to educational quality. Attention for quality was measured using a single item. Ambitions to improve quality was measured using seven items that focused on student performance and development (α = 0.87). Urgency to improve quality was measured using seven items that focused on school climate and quality assurance (α = 0.89). Finally, investments in quality was measured using seven items parallel to those of urgency to improve quality (α = 0.88).

School culture outcomes

Four dependent variables were used that reflect outcomes related to school culture. Culture of continuous improvement was measured using four items (α = 0.71). Openness was measured using three items (α = 0.70). Pride was measured using two items (ρ = 0.74). Professionalization was measured using three items (α = 0.76).

Principle-based inspection

The variable principle-based inspection measured the perceptions of principals and teachers of the degree to which they experienced principle-based inspection using a single item: “I got enough room during the inspection to show how things are done around here”.

Control variables

We included several control variables in the analyses. First, a dummy variable for job type indicated whether the respondent was working as a school principal or teacher. Second, a dummy variable for sector indicated whether the respondent was working in a primary or secondary school. Third, a dummy variable indicated whether the respondent filled out the survey during the first round in September–December 2018 or during the second round in September–December 2019. Finally, the school’s average final exam scores in the year preceding inspection were included. Using scores from all primary and secondary schools in the Netherlands, we calculated standardized scores for the school in our sample. Thus, school performance in this study resembles the relative performance of the school compared to the whole population of schools in the same sector.

Analytical procedure

To test the effects of principle-based inspection, we took several analytical steps. First, because the respondents are nested in schools, multilevel models using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) were estimated for each dependent variable to account for within-school variance (McNeish, Citation2017; Musca et al., Citation2011). Intercept-only models were estimated, to determine the amount of variance that is attributed to the individual and school level. The proportion of variance attributable to the school level was calculated using the intra-class correlation (ICC). The ICC reflects the proportion of variance at the organizational level in relation to the total variance and always has a value between 0 and 1. As it has been argued that even very low values of ICC can represent meaningful variance (Musca et al., Citation2011), we proceeded with multilevel analyses even in the case of near-zero ICC values.

Second, we estimated models that included principle-based inspection and the control variables for each dependent variable to analyse the linear effect of principle-based inspection. Finally, we compared the linear-only models to models that also included the quadratic and cubic terms of principle-based inspection using a chi-square test. All analyses were performed in R using the lmer function in the lme4 package (Bates et al., Citation2015).

Results

Linear effects of principle-based inspection

shows the results from the multilevel analyses for outcomes related to the perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact. Principle-based inspection is significantly related to perceived effectiveness of the inspectorate’s feedback (β = 0.24, p < 0.001), to perceptions that the inspectorate’s inspection leads to bureaucracy (β = −0.23, p < 0.001), and to the use of the inspectorate’s directions (β = 0.15, p = 0.004). In general, schools that experience a principle-based inspection approach are more positive about the inspectorate’s impact on their school.

Table 2. Effects of principle-based (PB) inspection on perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact.

shows the results from the multilevel regression analyses for outcomes related to educational quality. Principle-based inspection is significantly related to a school’s ambition to improve quality (β = 0.11, p < 0.001) and to a school’s investments in quality (β = 0.12, p = 0.005). In other words, schools that experience a principle-based inspection are more likely to have higher ambitions towards and investments in quality. In contrast, principle-based inspection is not significantly related to a school’s attention for quality and urgency to improve quality.

Table 3. Effects of principle-based (PB) inspection on outcomes related to educational quality.

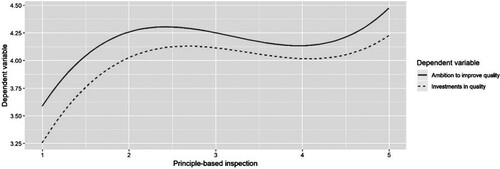

Finally, shows the results from the multilevel analyses for outcomes related to school culture. Principle-based inspection is significantly related to the presence of a culture of continuous improvement (β = 0.08, p = 0.016), the level of openness (β = 0.08, p = 0.048), the level of pride of personnel (β = 0.14, p < 0.001), and the level of professionalization of personnel (β = 0.13, p < 0.001). In other words, schools that experience a principle-based inspection style are more likely to have a culture of improvement, openness, pride, and professionalization.

Table 4. Effects of principle-based (PB) inspection on outcomes related to school culture.

Curvilinear effects of principle-based inspection

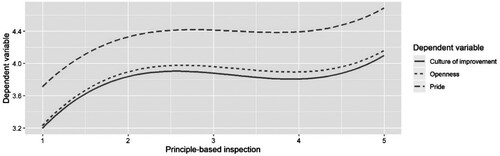

In addition to testing linear effects, we also tested for curvilinear effects of principle-based inspection. In particular, we analysed models including quadratic and cubic terms. As shown in and , principle-based inspection has, in addition to a linear effect, a cubic effect on various outcomes. We found significant cubic effects on ambition to improve and investments in educational quality, illustrated in . While there is some variation between dependent variables, the cubic effects demonstrate that the effect of principle-based inspection is stronger at the extremes. In other words, the gain from experiencing principle-based inspection is largest going from no to some principle-based inspection and from much to very much principle-based inspection. Similarly, it does not seem to matter much if schools experience some or much principle-based inspection.

Figure 2. Curvilinear effects of principle-based inspection on outcomes related to educational quality.

We also found significant cubic effects for culture of continuous improvement, openness, and pride, which we illustrate in . Similar to , the cubic effects here demonstrate that principle-based inspection has a stronger effect towards the extremes. This effect is more pronounced for pride than for openness and culture of improvement.

Conclusion Study 2

The aim of Study 2 was to build on the findings from Study 1 by using survey data to examine the various ways that a principle-based supervisory style of the inspectorate affects schools. Following Study 1, we identified three broad mechanisms through which a principle-based inspection has an impact: (I) perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact, (II) outcomes related to educational quality, and (III) outcomes related to school culture. The analyses revealed three main findings.

First, the results, in general, corroborate the notion that a principle-based inspection has a positive impact through the mechanisms we identified. Apart from attention for educational quality and the urgency to improve quality, principle-based inspection is positively related to perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact and to outcomes related to educational quality and school outcomes. However, given the relatively small effect sizes, the impact of principle-based inspection should not be overstated.

Second, the findings indicate that principle-based inspection is most strongly related to how school principals and teachers perceive the inspectorate’s impact, compared to outcomes related to educational quality and school culture. In particular, respondents who experience principle-based inspection report a higher effectiveness of the inspectorate’s feedback and lower levels of bureaucracy. A possible explanation for these stronger effect sizes is that perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact are more proximal outcomes than the other outcomes we examined.

Third, the findings reveal that for several outcomes, the impact of principle-based inspection is curvilinear. The effect of principle-based inspection is not similar across all schools. In other words, experiencing more principle-based inspection is not always associated with an equal increase in the outcomes. For example, the results show that experiencing some instead of no principle-based inspection matters much more for investments in quality than experiencing a high degree instead of some principle-based inspection.

Discussion

Before we turn to our findings, we first address the limitations of our two studies. The first study might have suffered from hierarchical relations between respondents during the group model building workshops. Since we were aware of this potential risk, we took some measures in advance to reduce this risk. To involve all respondents equally, the sessions were moderated by a neutral facilitator who actively invited each of the respondents to contribute to the session. As such, they contributed in a balanced way to the discussed list of relevant variables and the development of the causal model. We also invited multiple teachers and school leaders to reach a well-balanced input from all of the schools. While these measures are not a guarantee that power distortion did not occur during the workshops, it helped us to minimize its potential negative impact on the group discussion. In the second study, we measured perceptions of principle-based inspection using a single item. While this item grasps a core aspect of the concept and allowed us to focus on the graduality of a principle-based approach during the inspection visits, future research on other aspects is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the interactions during inspection visits.

Answering our main question, we have shown in two methodologically complementary studies that principle-based inspection has an effect, although not always straightforward or substantial. The first study, which has a high internal validity, shows loops of causal relationships between educational quality and principle-based inspection. Within these loops, there is a degree of variation in the mechanisms and effects (see ). Within the continuous improvement culture loop, trust – more precisely a lack of trust – is exemplary. A lack of trust may, through diverse routes, have a negative impact on the potential effect of the reports and feedback of the inspectorate. At the same time, a lack of trust may lead to a stronger focus on administrative burden, a control reflex, and accountability. Once a certain trend is set in motion, the reinforcing feedback loops we found will lead to further increases of that same development: A school that is performing well in terms of educational quality will get more room from the inspectorate to work on quality as it deems appropriate, which further improves quality. For schools that do not perform well in the eyes of the inspectorate, this may work out detrimentally: The perceived lack of educational quality is sanctioned by less room to work on quality as the school deems appropriate, and to an increased administrative burden of monitoring, which results in even lower educational quality. Paradoxically, principle-based inspection appears to work in the places where it is not needed, and it is not applied in those places where the potential benefits of the principle-based approach are most needed.

The second study validates the various ways the inspectorate has an impact in schools as we identified in the first study, and adds two important nuances. First, while many of the expected effects of principle-based inspection were confirmed, the findings reveal that these effects are relatively small. Thus, the impact of using a principle-based inspection should not be overstated, especially for more distal outcomes such as school culture. Second, findings from Study 2 indicate that the effects on various outcomes are curvilinear. That is, experiencing more principle-based inspection is not always equally beneficial. Most of the time, it does not seem to be relevant at all. Only schools that experience an increase from no to some and from a high degree to a very high degree of principle-based inspection seem to benefit.

The inspectorate’s renewed inspection approach builds on two theoretical regulatory practices of full PBR: a persuasion-based enforcement approach and meta-regulation. By looking at persuasion-based enforcement, our study reveals that there is a clear need to stress the idea of contingency and therefore a clear need for a tailored approach to inspection. As such, the theoretical notions of a persuasion-based enforcement approach are reconfirmed and show once more that such an approach is not a panacea. Evaluating the impact of meta-regulation seems too early, as the impact of the inspectorate’s new approach via school boards is not clear to respondents and not yet fully understood.

Moreover, respondents seem to perceive principle-based inspection as a reward rather than a deliberate attitude of the inspectorate. This is less of a surprise, since the inspectorate speaks about earned trust. This approach does not match with theoretical assumptions about the effects and use of full PBR. Methodologically, this study provides a promising new avenue to better understand the interactions and dynamics in schools and between the inspectorate and school boards. The most important finding is that patterns and mechanisms are all but straightforward.

NSES-2021-0017.R2_Honingh_et_al._figures.docx

Download MS Word (204.9 KB)NSES-2021-0017.R2_Honingh_et_al._appendices.docx

Download MS Word (26.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marlies Honingh

Marlies Honingh is an associate professor at the Public Administration department at Radboud University in Nijmegen. She has been leading commissioned research and NOW- and NRO-granted projects in primary, secondary, and vocational education. The theme of educational governance has been central to her research since she started her PhD. Her methodological experience stretches from inductive qualitative methods to quantitative advanced research methods. https://nl.linkedin.com/in/marlies-honingh-654869

Marieke van Genugten

Marieke van Genugten is an associate professor at the Public Administration department at Radboud University in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. She holds a PhD in Public Administration from the University of Twente. She has conducted extensive (commissioned) research on public service delivery at arm’s length of government, in particular local government, and related topics such as regulation, steering, and accountability.

Vincent de Gooyert

Vincent de Gooyert is an associate professor of Research Methodology at the Nijmegen School of Management, Radboud University. He is trained both as an engineer and as a sociologist, and his work often aims to transcend disciplines, using and contributing to methods on stakeholder engagement, system dynamics, and socio-technical transitions. Vincent was a visiting scholar at the MIT Sloan School of Management and Schulich School of Business, York University. https://www.linkedin.com/in/degooyert/

Rutger Blom

Rutger Blom is a postdoctoral researcher at the Public Administration department, Radboud University, Nijmegen. His current research focuses on competencies of civil servants. In addition, he is interested in research on strategic HRM in government organizations and the influence of the public sector context on (the work of) civil servants.

References

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- Ayres, I., & Braithwaite, J. (1992). Responsive regulation: Transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford University Press.

- Baldwin, R., & Black, J. (2008). Really responsive regulation. Modern Law Review, 71(1), 59–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.2008.00681.x

- Bardach, E., & Kagan, R. A. (1982). Going by the book: The problem of regulatory unreasonableness. Temple University Press.

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Black, J. (2008). Forms and paradoxes of principles-based regulation. Capital Markets Law Journal, 3(4), 425–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cmlj/kmn026

- Braithwaite, V. (1995). Games of engagement: Postures within the regulatory community. Law & Policy, 17(3), 225–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.1995.tb00149.x

- de Gooyert, V. (2019). Developing dynamic organizational theories: Three system dynamics based research strategies. Quality & Quantity, 53(2), 653–666. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0781-y

- de Gooyert, V., & Größler, A. (2018). On the differences between theoretical and applied system dynamics modeling. System Dynamics Review, 34(4), 575–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.1617

- Ehren, M. C. M. (Ed.). (2016). Methods and modalities of effective school inspections. Springer.

- Gunningham, N. (1987). Negotiated non-compliance: A case study of regulatory failure. Law & Policy, 9(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.1987.tb00398.x

- Gunningham, N. (2010). Enforcement and compliance strategies. In R. Baldwin, M. Cave, & M. Lodge (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of regulation (pp. 120–145). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199560219.003.0007

- Hawkins, K. (1983). Bargain and bluff: Compliance strategy and deterrence in the enforcement of regulation. Law & Policy, 5(1), 35–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.1983.tb00289.x

- Helderman, J. K., & Honingh, M. E. (with Thewissen, S.). (2009). Systeemtoezicht: Een onderzoek naar de condities en werking van systeemtoezicht in zes sectoren [A study of the conditions and functioning of systems-based regulation in six sectors]. Boom Juridische uitgevers.

- Hickman, K., & Hill, C. (2010). Concepts, categories, and compliance in the regulatory state. Minnesota Law Review, 94, 1151–1201. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/faculty_articles/60

- Honingh, M., Ruiter, M., & van Thiel, S. (2020). Are school boards and educational quality related? Results of an international literature review. Educational Review, 72(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1487387

- Hooge, E., & Honingh, M. (2014). Are school boards aware of the educational quality of their schools? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(4_suppl), 139–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213510509

- Hovmand, P. S., Andersen, D. F., Rouwette, E., Richardson, G. P., Rux, K., & Calhoun, A. (2012). Group model-building “scripts” as a collaborative planning tool. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 29(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2105

- Inspectie van het Onderwijs. (2017). Onderzoekskader 2017 voor het toezicht op het voortgezet onderwijs [Research framework 2017 for the supervision of secondary education].

- Kagan, R. A., & Scholz, J. T. (1984). The “criminology of the corporation” and regulatory enforcement strategies. In K. Hawkins & J. M. Thomas (Eds.), Enforcing regulation (pp. 67–96). Kluwer-Nijhoff.

- Lodge, M., & Wegrich, K. (2012). Managing regulation: Regulatory analysis, politics and policy. Macmillan International Higher Education.

- McNeish, D. (2017). Small sample methods for multilevel modeling: A colloquial elucidation of REML and the Kenward-Roger correction. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 52(5), 661–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2017.1344538

- Musca, S. C., Kamiejski, R., Nugier, A., Meot, A., Er-Rafiy, A., & Brauer, M. (2011). Data with hierarchical structure: Impact of intraclass correlation and sample size on type-I error. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, Article 74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00074

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2016). Netherlands 2016: Foundations for the future: Reviews of national policies for education. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257658-en

- Reiman, T., & Norros, L. (2002). Regulatory culture: Balancing the different demands of regulatory practice in the nuclear industry. In B. Kirwan, A. Hale, & A. Hopkins (Eds.), Changing regulation: Controlling risks in society (pp. 175–192). Elsevier Science.

- Richardson, G. P., & Andersen, D. F. (1995). Teamwork in group model building. System Dynamics Review, 11(2), 113–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.4260110203

- Staatsblad. (2010). Wet goed onderwijs, goed bestuur [Good education, good governance act]. (Staatsblad No. 80 en 282). Sdu Uitgevers.

- Vennix, J. A. M. (1999). Group model-building: Tackling messy problems. System Dynamics Review, 15(4), 379–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1727(199924)15:4<379::AID-SDR179>3.0.CO;2-E

1

Survey items

| I. | Perceptions of inspectorate’s impact

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| II. | Educational quality outcomes

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| III. | School culture outcomes

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IV. | Principle-based inspection

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2

Factor loadings from maximum likelihood exploratory factor analyses

Table A1. Factor loadings for items related to perceptions of the inspectorate’s impact.

Table A2. Factor loadings for items related to educational quality outcomes.

Table A3. Factor loadings for items related to school culture outcomes.