ABSTRACT

In order to increase the consumption of lamb meat, new products, such as burgers, were elaborated using leg meat. Since meat products are perishable foods, it is necessary to extend its shelf-life. For this reason, this study examined the combined effect of powdered spices (rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic; a control group non-spiced was used) and a packaging method (vacuum [VP] and two gases mixtures [30% CO2 + 70% O2 (AA); 30% CO2 + 69.3% N2 + 0.7% CO (AB)]) on colour coordinates, microbial counts (total viable count, Pseudomonas spp., Enterobacteriaceae, lactic acid bacteria) and lipid oxidation (LO) over 13 days of storage. Rosemary, thyme and sage stabilized LO values and maintained colour in all packaging tested over time. AA-garlic and AA-control burgers showed the highest discoloration and rancidity levels (p < 0.001). No significant differences were found among batches on microbial quality (except in LAB).

RESUMEN

Con objeto de incrementar el consumo de carne de cordero, nuevos productos, tales como hamburguesas, fueron elaborados con carne de pierna. Ya que los productos cárnicos son muy perecederos, es preciso extender su vida útil. Por ello, este trabajo examinó el efecto combinado de especias molidas (romero, tomillo, salvia o ajo; un grupo control no especiado fue usado) con un método de envasado [vacío (VP) y dos mezclas de gases: 30% CO2 +70% O2 (AA); 30% CO2 + 69,3% N2+0,7% CO (AB)] sobre las coordenadas de color, el crecimiento microbiano [recuento total de aerobios (TVC), Pseudomonas spp., Enterobacteriaceae y bacterias ácido lácticas (LAB)] y la oxidación lipídica (LO) durante 13 días de almacenamiento. El romero, tomillo y salvia estabilizaron los valores de LO y mantuvieron el color en todos los métodos de envasado testados. Sin embargo, las decoloraciones y enranciamiento más acusadas se observaron en las muestras control o con ajo y envasadas con la atmósfera AA (p < 0,001). No hubo diferencias significativas entre los lotes comparados en la calidad microbiológica (excepto en LAB).

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

In spite of lamb meat is considered a traditional-natural food (Fortuny, Citation2017) with a high quality (Vergara & Gallego, Citation2001), its consumption rate is very low, 1.61 kg per capita (MAPAMA, Citation2016), contrasting with processed meat, such as burger, whose consumption has increased by up to 65% in last 5 years (Lavaca, Citation2016). This proclivity could be an opportunity for sheep meat sector to enhance the consumption rate of lamb meat, especially among young people, through new lamb meat products, such as lamb burgers.

Burgers quality can be spoiled by the chemical and enzymatic activities, bacteria growth and fat oxidation (Maas-Van Berkel, Van Den Boogaard, & Heijnen, Citation2004), with colour variations, off flavour, rancidity and slim formation. This deterioration makes inadmissible the consumption of these products (Dave & Ghaly, Citation2011). Moreover, these processes take place quickly in the manufactured products with minced meats, owing to the mincing process (Honikel, Citation2014). In order to delay this spoilage, physical methods (such as the vacuum packaging [VP] or modified atmospheres systems) or substances, with different properties, are acceptable alternatives to maintain both shelf-life and quality in meat products (Vergara & Cózar, Citation2015).

Spices have been added to foodstuffs since ancient times, their characteristics improve flavour, colour, aroma of food and possess nutritional, antioxidant, antimicrobial and medicinal properties. Besides, their use allows to reduce the addition of salt and sugar, to enhance the texture of some food and to replace the use of synthetic additives (Raghavan, Citation2007). Nevertheless, the effectiveness of spices is conditioned by many factors, such as, the moment of harvest, the geographic origin, the variety and quantity of components, the concentration added and the type of meat matrix in which are used (Raghavan, Citation2007; Yanishlieva, Marinova, & Pokorný, Citation2006).

The addition of natural substances along with a packaging method (VP or modified atmosphere packaging [MAP]) would help preserve the meat products (Mastromatteo, Conte, & Del Nobile, Citation2010), especially in the case of fresh meat products (burgers, sausages etc.). There are relatively few published data about the combined effects of spices and packaging-systems on lamb meat products quality, which were also added as extracts in the matrix of minced meat (Andrés, O’Grady, Gutierrez, and Kerry, Citation2010 [in lamb products]; Fernandes, Trindade, Lorenzo, Munekata, and De Melo, Citation2016 [in sheep products]) but there are no studies with added ground spices in manufacturing.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyse the combined effect of powdered spices (rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic) with a specific packaging method (vacuum or a gases mixture [AA: 30% CO2 + 70% O2 or AB: 30% CO2 + 69.3% N2 + 0.7% CO]) on the shelf-life lamb burgers (assessed by colour, microbial count and lipid oxidation [LO]) for 13 days of storage.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Burgers preparation and packaging

For this study, Spanish Manchega breed lambs leg meat was used, belonging to the official label “Manchego Lamb PGI”, slaughtered with 25 kg live weight (70 days old). After slaughtering and dressing by standard commercial procedures, all carcases were chilled at 4°C for 24 h. Then, the legs were deboned and meat was minced. The ground meat was distributed into five batches, mixed by hand, for 5 min, with salt (1% w/w) and a powdered spice (0.1% w/w). All of spices [rosemary, thyme (Artemis, Alicante, Spain), sage (Soria Natural, Soria, Spain), garlic (Ducros, Barcelona, Spain)] were purchased at supermarket and then ground in the laboratory. A non-spiced control batch (only with salt) was used. Afterwards, lamb burgers of 100 g and 10 cm diameter were formed using a manual burger marker (model 2R, BECAM, Jose Bernad S. L., Albacete, Spain). The final concentration (0.1% w/w) of powdered spices was chosen taking into account the bibliography (Shahidi, Pegg, and Saleemi Citation1995, Yanishlieva et al. Citation2006; Viuda-Martos, Ruiz-Navajas, Fernández-López, and Pérez-Álvarez Citation2010) and a previous sensorial analysis by members of the university community.

In each batch, burgers were preserved under different packaging systems:

VP: Burgers were placed into vacuum bag made with coextruded polyamide/polyethylene film with an O2 permeability of <40 cm3/m2 24 h 1 atm, 23°C and 75% HR, a CO2 permeability of 130 cm3/m2 24 h 1 atm and 23°C and 150 µm of thickness (Ind. Pargon, José Bernard S.L., Albacete, Spain). The bags were vacuum sealed using a vacuum machine Selecta Vacuum saler model “Sealcom-V” (Abrera, Barcelona).

MAP: Burgers were situated into each white expanded polystyrene barrier trays, with an O2 permeability of 0.5 cm3/m2 24 h 1 atm and 23°C, a CO2 permeability of 20 cm3/m2 24 h 1 atm and 23°C (Aerpack, model B3-55, Coopbox Hispania S.L.U., Lorca, Murcia, Spain) and a transparent cover barrier film, with an O2 permeability of 1 cm3/m2 24 h 1 atm, 23°C and 50% HR, a CO2 permeability of 5.5 cm3/m2 24 h 1 atm, 23°C and 0% HR (Aertop, 60 µm of thickness, Coopbox Hispania S.L.U., Lorca, Murcia, Spain). An ILPRA packaging machine (model FB Basic, Vigenano, Italia) was used. Two gas mixtures were compared, AA: 30% CO2 + 70% O2 and AB: 30% CO2 + 69.3% N2 + 0.7% CO supplied by Abelló Linde S.A. (Barcelona, Spain) and Carburos Metálicos S.A. (Barcelona, Spain), respectively.

After packaging, burgers were kept at 2°C in the dark until analysis. A total of eight lamb burgers for each condition (spice, packaging and time of storage) were used. For each batch, three replicates were made.

2.2. Analysis of lamb burgers quality

Colour coordinates, microbiological count and LO were assessed in all burgers at 0, 6, 9 and 13 days post-manufacture. Before the opening the trays for the analysis, gas composition was checked for packs under atmosphere AA and AB using a CheckMate PBI Dansensor (Ringsted, Denmark) gas analyser.

2.3. Colour coordinates

Lightness (L*), redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) were evaluated using a Minolta CR400 chromameter (Osaka, Japan) with a D65 illuminate and a 10° standard observer angle, calibrated against a standard white tile on the surface of the raw samples, 15 min after pack opening. The final value was the mean of three determinations.

2.4. Microbiological analysis

Samples (approximately 5 g) were transferred to a sterile bag with 45 ml of peptone water (Scharlau Chemie, Barcelona, Spain) and blended for 60 s in a Stomacher (Masticator, IUL Instruments, Barcelona, Spain). Serial dilutions were prepared and duplicate 1 ml inoculums from decimal solution were spread into Petrifilm™ total viable count (TVC) and Enterobacteriaceae Count Plate (3M™, Madrid, Spain) and were incubated at 32°C during 48 and 24 h, respectively. Duplicate 100 µl inocula of decimal solution were spread on Petri dishes, using a spiral system (Eddy-Jet, IUL-Instruments, Barcelona, Spain), to count Pseudomonas spp. on Pseudomonas Agar Base with a cetrimid, fucidin, cephaloridin supplement (Pseudomonas CFC, Oxoid LTD; Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) on Man, Rogosa and Sharpe agar (MRS, Scharlau Chemie S.L.). Plates Petri were incubated during 48 h at 32°C or at 25°C for LAB and Pseudomonas spp., respectively. An automatic colony counter (Countermat-Flash, IUL-Instrument, Barcelona, Spain) was used for counting plate Petri. The results were expressed as log CFU/g.

2.5. Lipid oxidation

Rancidity levels were determined according to Tarladgis, Pearson and Dugan (Citation1964). Five grams of sample was homogenised with 25 ml of distillate water with an Ultraturrax T25 digital (Ika Works, Inc.) for 2 min at 10,000 rpm to room temperature. After that, 25 ml of trichloroacetic acid (10%) was added. The 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances were measured by absorbance in duplicate and read with a Helios α-spectrophotometer (THERMO, Electron Corporation, England) at 532 nm. The results were expressed as mg malondialdehyde (MDA)/kg meat.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the SPSS 22.0 version statistical package (Corp, Citation2013). First, a Shapiro–Wilk test was carried out to check the normality and homogeneity of variance of all variables. A two-way ANOVA was carried out, using the SPSS Statistics general lineal model procedure, in order to assess the significance of the spice (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic), the type of packaging (VP, AA or AB) and the interaction between both factors on the parameters analysed, at 6, 9 and 13 days post-manufacture. In each batch an ANOVA was used for checking the effect of time (0, 6, 9 and 13 days) on parameters studied. When the differences were significant (p < 0.05), a Tukey’s test at a significant level of p < 0.05 was carried out to check the differences between pairs of groups.

3. Results

3.1. Colour coordinates

shows the effect of the system of packaged (VP, AA or AB), the spice added (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic), the interaction of both factors on chromatic coordinates (L*, a* and b*) and the evolution of colour during period of storage of lamb burgers. The packaging method significantly affected (p < 0.001) a* and b* coordinates in all times of study; by contrast, L* only showed differences at 13 days of storage (p < 0.05). The powdered spice type caused significant differences in L*, a* (at 9 and 13 days) and b* values (at 13 days of storage). There was a significant interaction between the factors studied in L* (at 13 days; p < 0.001), a* (p < 0.001) and b* (at 9 and 13 days; p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively). In AA burgers, the colour coordinates values changed during the period of analysis (), with a significant (p < 0.001) decline of redness (in all batches), an increase of both b* (except in burgers with sage) and L* (except in samples with thyme or sage). There was a high stability in L* values during all time of storage and after 6 days of manufacture in a* and b* coordinates in VP and AB burgers.

Table 1. Effect of packaging method (VP: vacuum, AA: 30% CO2 + 70% O2 or AB: 30% CO2 + 69.3% N2 + 0.7% CO), powdered spiced used (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic) and the interaction between both factors on colour coordinates (L*, a* and b*; mean ± SE) of lamb burgers.

Tabla 1. Efecto del método de envasado (VP: vacío, AA: 30%CO2 + 70%O2 ó AB: 30%CO2 + 69,3%N2 + 0,7%CO), la especia molida añadida (control, romero, tomillo, salvia o ajo) y la interacción entre ambos factores en las coordenadas de color (L*, a* y b*; Media ± E.S.) de hamburguesas de cordero.

3.2. Microbiology

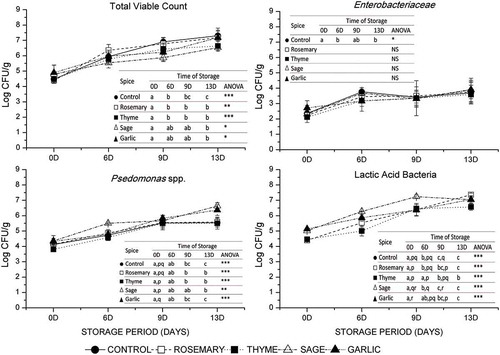

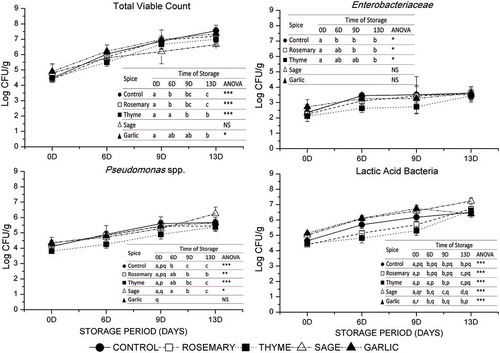

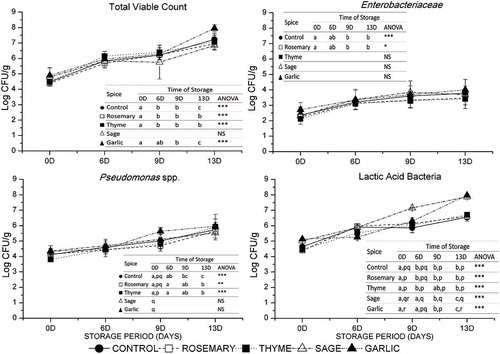

In general, the packaging method or the spice added did not affect microorganisms count (). VP samples () presented an increase in all microorganisms analysed (except in Enterobacteriaceae), without influence of the added spice. Curiously, in burgers with sage and in both AA and AB packaging methods ( and , respectively), TVC, Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. count did not change with the time of storage. Only the LAB values were significantly affected by the studied factors. Burgers spiced with rosemary or thyme and packaged under AA or AB, showed lower LAB counts than the other batches analysed.

Table 2. Effect of packaging method (VP: vacuum, AA: 30% CO2 + 70% O2 or AB: 30% CO2 + 69.3% N2 + 0.7% CO), powdered spiced used (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic) and the interaction between both factors on microorganisms (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp. and LAB) of lamb burgers.

Tabla 2. Efecto del método de envasado (VP: vacío, AA: 30%CO2 + 70%O2 ó AB: 30%CO2 + 69,3%N2 + 0,7%CO), la especia molida añadida (control, romero, tomillo, salvia o ajo) y la interacción entre ambos factores en la microbiología (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp. y LAB) de hamburguesas de cordero.

Figure 1. Evolution of microbial growth (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., LAB) in lamb burgers manufactured with different powdered spices and packaged under vacuum (mean ± SE). Not significant. *,**,***Indicate significances levels at 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. a–cDifferent letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) due to the effect of storage period. p–rDifferent letters, in the same time of storage, indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) due to the powdered spice added (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic).

Figura 1. Evolución del crecimiento microbiano (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., LAB) en hamburguesas de cordero elaboradas con diferentes especias molidas y envasadas en vacío (Media±E.S.). NS: No significativo. *, **, ***: Indica niveles de significancia de 0,05, 0,01 y 0,001, respectivamente. a, b, c: Diferentes letras indicas diferencias significativas (p < 0,05) debidas al efecto del periodo de almacenamiento. p, q, r: Diferentes letras, en el mismo tiempo de almacenamiento, indica diferencias significativas (p < 0,05) debido a la especia molida añadida (control, romero, tomillo, salvia ó ajo).

Figure 2. Evolution of microbial growth (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., LAB) in lamb burgers with different powdered spices and packaged under AA (30% CO2 + 70% O2) (mean ± SE). Not significant. *,**,***Indicate significance levels at 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. a–cDifferent letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) due to the effect of storage period. p–rDifferent letters, in the same time of storage, indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) due to the powdered spice added (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic).

Figura 2. Evolución del crecimiento microbiano (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., LAB) en hamburguesas de cordero elaboradas con diferentes especias molidas y envasadas en AA (30%CO2 + 70%O2) (Media±E.S.). NS: No significativo. *, **, ***: Indica niveles de significancia de 0,05, 0,01 y 0,001, respectivamente. a, b, c: Diferentes letras indicas diferencias significativas (p < 0,05) debidas al efecto del periodo de almacenamiento. p, q, r: Diferentes letras, en el mismo tiempo de almacenamiento, indica diferencias significativas (p < 0,05) debido a la especia molida añadida (control, romero, tomillo, salvia ó ajo).

Figure 3. Evolution of microbial growth (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., LAB) in lamb burgers with different powdered spices and packaged under AB (30% CO2 + 69.3% N2 + 0.7% CO) (mean ± SE). Not significant. *,**,***Indicate significances levels at 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively. a–cDifferent letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) due to the effect of storage period. p–rDifferent letters, in the same time of storage, indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) due to the powdered spice added (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic).

Figura 3. Evolución del crecimiento microbiano (TVC, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas spp., LAB) en hamburguesas de cordero elaboradas con diferentes especias molidas y envasadas en AB (30%CO2 + 69,3%N2 + 0,7%CO) (Media ± E.S). NS: No significativo. *, **, ***: Indica niveles de significancia de 0,05, 0,01 y 0,001, respectivamente. a, b, c: Diferentes letras indicas diferencias significativas (p < 0,05) debidas al efecto del periodo de almacenamiento. p, q, r: Diferentes letras, en el mismo tiempo de almacenamiento, indica diferencias significativas (p < 0,05) debido a la especia molida añadida (control, romero, tomillo, salvia ó ajo).

3.3. Lipid oxidation

The factors analysed significantly affected (p < 0.001) the LO values () in all times of analysis:

Samples with rosemary, thyme or sage showed a high lipid stability in all packaging methods, with values ranged between 0.22 and 1.04 mg MDA/kg meat, and without significant differences due to the time of storage ().

In samples with garlic or control, LO values developed differently depending upon the packaging method. Under VP or AB, LO increased until 6 days of storage, reaching values higher than 2 mg MDA/kg meat. However, when AA system was used, rancidity rose gradually throughout of study, reaching values around 6 mg MDA/kg meat at the end of the study.

Table 3. Effect of packaging method (VP: vacuum, AA: 30% CO2 + 70% O2 or AB: 30% CO2 + 69.3% N2 + 0.7% CO), powdered spiced used (control, rosemary, thyme, sage or garlic) and the interaction between both factors on lipid oxidation (mean ± SE) of lamb burgers.

Tabla 3. Efecto del método de envasado (VP: Vacío, AA: 30%CO2 + 70%O2 ó AB: 30%CO2 + 69,3%N2 + 0,7%CO), la especia molida añadida (control, romero, tomillo, salvia o ajo) y la interacción entre ambos factores en la oxidación lipídica (Media ± E.S.) de hamburguesas de cordero.

4. Discussion

4.1. Colour coordinates

Due to the importance of meat colour at the purchase time, changes on coordinates chromatics have been widely studied in different minced meat products (Andrés et al., Citation2010; Degirmencioglu, Esmer, Irkin, & Degirmencioglu, Citation2012; Fernandes et al., Citation2016; Jeong & Claus, Citation2011; Karpińska-Tymoszczyk, Citation2010; Kerry, O’Sullivan, Buckley, Lynch, & Morrissey, Citation2000; Martínez, Djenane, Cilla, Beltrán, & Roncalés, Citation2005; Sánchez-Escalante, Djenane, Torrescano, Beltrán, & Roncalés, Citation2001). The modifications on colour coordinates have been associated with the lipid and myoglobin oxidation (Andrés et al., Citation2010), Pseudomonas spp. and Enterobacteriaceae growth (Feiner, Citation2006; Mills, Donnison, & Brightwell, Citation2014) and a decrease on moisture retention of meat products (Fernandes et al., Citation2016). Moreover, this loss of colour in meat products is principally associated to a decrease of a* coordinate, which is the principal parameter that influences at the purchase moment (Walsh & Kerry, Citation2002).

The differences of colour among batches of burgers could be explained by the significant interaction between type of packaging and powdered spice:

Burgers under AA method and spiced with rosemary, thyme or sage showed a red index higher than control or garlic samples, especially at 13 days of storage. Raghavan (Citation2007) associated the effectiveness of rosemary, sage and thyme for maintaining the red colour of processed meats to their antioxidant properties. Sánchez-Escalante et al. (Citation2001) also presented an improvement in a* values in beef patties with powdered rosemary under MAP with 70% O2. The depletion in the values of a* in control burgers or spiced with garlic could be explained by a negative combined effect of both, the high level of O2 (70%) which favours the LO (Kerry et al., Citation2000; Sørheim, Nissen, & Nesbakken, Citation1999) and the pro-oxidant effect of garlic (Mariutti, Nogueira, & Bragagnolo, Citation2011; Wong & Kitts, Citation2002) and salt (Faustman, Yin, & Tatiyaborworntham, Citation2010; Feiner, Citation2006).

In burgers packaged under VP or AB, no differences were found in the colour coordinates due to the addition of powdered spices. The stability of both packaging system, after 6 days of storage until the end of the study, is in concordance with the results of Jeong and Claus (Citation2011) in ground beef meat under VP and with Martínez et al. (Citation2005) in pork-sausages packaged with 0.3% CO. In agreement with Rogers et al. (Citation2014), the absence of O2 in VP or atmosphere with CO improves colour stability.

4.2. Microbiology

For TVC, a 7 log CFU/g of meat is the value considered as the beginning of deterioration of the meat and meat products (Feiner, Citation2006). In general, this limit was reached at 13 days in all samples. Degirmencioglu et al. (Citation2012) also noted an increase in microbial counts in ground beef under VP and MAP, but with values lower than 7 log CFU/g. Fernandes et al. (Citation2016) reported a shelf-life up to 10 days in sheep burgers packed under 80% O2 + 20% CO2, with oregano extract and BHT (butylated hydroxytoluene).

There are several reasons to explain the increase of aerobic microorganisms during storage time in each packaging conditions studied:

First, a low level of O2 (0.5%) permits the growth of some aerobic microorganism (Nowak, Sammet, Klein, & Mueffling, Citation2006). This O2 content is easy to reach in packaging such as AA (70% O2), or due to the oxygen permeability of packaging films in VP or MAP (AA and AB) and this permeability has been inversely associated to the shelf-life of packaged product (Newton & Rigg, Citation1979).

Second, a high initial microbial value affects the shelf-life and the effectiveness of the packaging methods (Mastromatteo, Lucera, Sinigaglia, & Corbo, Citation2009). Our results showed initial counts of TVC slightly higher than 4 log CFU/g meat, which, according to Feiner (Citation2006), should be the limit for the bacteria counts in raw meat. Fernandes et al. (Citation2016) observed initial values around 5 log CFU/g of meat in sheep burgers.

Finally, the process of manufacture (ground, mixed) of the fresh meat products is associated to an increase of microorganism counts (Martínez et al., Citation2005).

As regard to Pseudomonas spp. and Enterobacteriaceae, the limit of 7 log CFU/g was not reached during storage, which could be explained since these microorganisms (Gram negative) are more sensitive to CO2 (Feiner, Citation2006). Our results were similar to that found by Fernandes et al. (Citation2016), in sheep burger meat at 20 days, in Enterobacteriaceae count but slightly higher in Pseudomonas spp.

LAB are facultative anaerobic, can grow in systems without O2 or with high concentration of CO2 (Karabagias, Badeka, & Kontominas, Citation2011) and, thus, are the predominant bacteria in meat products under VP or MAP (Mastromatteo et al., Citation2009). This fact could explain the increase of LAB counts during storage in all the batches and the absence of differences among packaging systems. On the other hand, although LAB are less sensitive to use of antimicrobial substances (Shelef, Citation1983), the addition of rosemary or thyme in the elaboration of lamb burgers had a slight antimicrobial effect. However, this effect only kept the count of LAB below 7 log CFU/g of meat (limit of spoilage, Feiner, Citation2006) until 9 days of storage.

Thus, the addition of these powdered spices in the elaboration of lamb burgers showed a low antimicrobial effectiveness in the microorganisms tested, which could be explained by the concentration added (0.1%) and type of format (powdered) used. The antimicrobial effect of spices is conditioned by various factors such as format of spice (ground, extract, oil etc.), concentration of substances, meat matrix or type of microorganisms (Shelef, Citation1983; Zaika, Citation1988).

4.3. Lipid oxidation

After 13 days of storage, LO levels ranged from 0.22 to 2.61 mg MDA/kg meat in VP, 0.67 to 6.27 mg MDA/kg meat in AA and 0.42 to 3.03 mg MDA/kg meat in AB. Several authors have found similar results over time. Degirmencioglu et al. (Citation2012) found values of LO around 5.16 under a gas mixture of 70% O2 + 30% CO2 and 1.45 mg MDA/kg of meat in minced beef meat at 7 days under vacuum packaged. Martínez et al. (Citation2005) noted values of 1.25 mg MDA/kg meat in fresh pork sausages under 0.3% CO + 30% CO2 + 69.7% Ar at 20 days of storage. Andrés et al. (Citation2010) obtained levels of LO between 0.12 and 0.78 mg MDA/kg meat on day 8 of storage in lamb burgers with resveratrol, citoflavan-3-ol, olive leaf extract or Echinacea purpurea under 75% O2 + 25% CO2. Our study showed a higher increase of rancidity on control or garlic burgers under AA than under VP or AB over time. In agreement with Martínez et al. (Citation2005), a high percentage of O2 (such as in AA) rose the LO values rapidly.

According to the results obtained in the present study, the effectiveness of the packaging systems for controlling LO could be listed as VP > AB > AA. Other studies also indicated that VP was the most effective system to regulate the rancidity (Kerry et al., Citation2000; Suman et al., Citation2010). Rosemary, thyme or sage showed a large antioxidant effect irrespective of the packaged method used. These results are in accord with other reports that showed the antioxidant effect of these spices in different meat matrix under different systems of packaged (VP or MAP), in beef patties (Sánchez-Escalante et al., Citation2001), in cooked turkey meatballs (Karpińska-Tymoszczyk, Citation2010), in mortadella (Viuda-Martos, Ruiz-Navajas, Fernández-López, & Pérez-Álvarez, Citation2011) and in pork sausages (Martínez, Cilla, Beltrán, & Roncalés, Citation2006).

In contrast, control burgers or spiced with garlic showed the highest rancidity values. This could be associated to the pro-oxidant effect of garlic and the salt in control burgers. Some authors (Feiner, Citation2006) have found an increment of LO due to the addition of salt in the formulation of the meat products. This pro-oxidant effect of salt is not well known, but the presence of trace metal impurities present in salt could be a possible reason (Faustman et al., Citation2010). In relation to use of garlic, Mariutti et al. (Citation2011) in chicken meat and Wong and Kitts (Citation2002) in irradiated beef steaks also observed a pro-oxidative effect of this spice. However, Yin and Cheng (Citation2003) in spiced ground beef meat and Sallam, Ishioroshi and Samejima (Citation2004) in chicken sausages [manufactured with different format (fresh, powder and oil) and proportions] described an antioxidant effect of garlic which contrast with our study. The concentration used (0.1% w/w) in our study could possibly explain the pro-oxidant effect showed for the garlic. In addition and according to Sallam et al. (Citation2004), the antioxidant effect of garlic could be dependent on the concentration added to meat products.

Finally, there was a marked interaction between the system of packaging and the added spice in LO values. Burgers with rosemary, thyme or sage regardless of the packaged system did not reach the value of 2 mg MDA/kg meat, which have been associated with off odours in lamb meat (Camo, Beltrán, & Roncalés, Citation2008). However, the use of garlic or only salt (control burgers) favoured the LO and consequently causing a short shelf-life, especially when samples were preserved under high O2 concentration (AA).

5. Conclusions

Our study showed the differences on lamb burgers shelf-life due to the combined effect of spice and the packaging system. (1) Samples spiced with rosemary, thyme or sage showed a high stability on colour coordinates and LO values, regardless of the packaging system; microbiology count was the limiting factor. (2) In contrast, as in the samples spiced with garlic as in control ones, shelf-life depended on packaging method and LO values were extremely high when AA was used. More studies are needed to find the right format and concentration of garlic to solve this disadvantage.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible through finance from The Consejería de Educación de la Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha: [Grant Number PII-2014-002-P] and A. Cózar was supported by a pre-doctoral grant from Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha and European Social Fund. We are also grateful to P. K. Walsh for assistance with the preparation of this manuscript in English.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrés, A. I., O’Grady, M. N., Gutierrez, J. I., & Kerry, J. P. (2010). Screening of phytochemicals in fresh lamb meat patties stored in modified atmosphere packs: Influence on selected meat quality characteristics. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 45(2), 289–294.

- Camo, J., Beltrán, J. A., & Roncalés, P. (2008). Extension of the display life of lamb with an antioxidant active packaging. Meat Science, 80(4), 1086–1091.

- Corp, I. B. M. (2013). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Dave, D., & Ghaly, A. E. (2011). Meat spoilage mechanisms and preservation techniques: A critical review. American Journal of Agricultural and Biological Science, 6(4), 486–510.

- Degirmencioglu, N., Esmer, O. K., Irkin, R., & Degirmencioglu, A. (2012). Effects of vacuum and modified atmosphere packaging on shelf life extension of minced meat chemical and microbiological changes. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances, 11(7), 898–911.

- Faustman, C., Yin, S., & Tatiyaborworntham, N. (2010). Oxidation and protection of red meat. In E. A. Decker, R. J. Elias, & D. J. McClements (Eds.), Oxidation in foods and beverages and antioxidant applications (Vol. 2, pp. 3–49). Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing Limited.

- Feiner, G. (2006). Meat products handbook. Practical science and technology. Cambridge, UK: CRC Press and Woodhead Publishing Limited.

- Fernandes, R. P. P., Trindade, M. A., Lorenzo, J. M., Munekata, P. E. S., & De Melo, M. P. (2016). Effects of oregano extract on oxidative, microbiological and sensory stability of sheep burgers packed in modified atmosphere. Food Control, 63, 65–75.

- Fortuny, R. (2017). La campaña de promoción de la carne de cordero y lechal frena la caída el consumo. Distribución Y Consumo, 2, 36–46.

- Honikel, K. O. (2014). Minced Meats. In M. Dikeman & C. Devine (Eds.), Encyclopedia of meat science (Vol. 2, 2nd ed. ed., pp. 422–424). London, UK: Academic Press.

- Jeong, J. Y., & Claus, J. R. (2011). Color stability of ground beef packaged in a low carbon monoxide atmosphere or vacuum. Meat Science, 87(1), 1–6.

- Karabagias, I., Badeka, A., & Kontominas, M. G. (2011). Shelf life extension of lamb meat using thyme or oregano essential oils and modified atmosphere packaging. Meat Science, 88(1), 109–116.

- Karpińska-Tymoszczyk, M. (2010). The effect of sage, sodium erythorbate and a mixture of sage and sodium erythorbate on the quality of turkey meatballs stored under vacuum and modified atmosphere conditions. British Poultry Science, 51(6), 745–759.

- Kerry, J. P., O’Sullivan, M. G., Buckley, D. J., Lynch, P. B., & Morrissey, P. A. (2000). The effects of dietary α-tocopheryl acetate supplementation and modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) on the quality of lamb patties. Meat Science, 56(1), 61–66.

- Lavaca. (2016). Tendencias y nuevos hábitos en el consumo de carne y Hamburguesa: La revolución gastronómica. La hamburguesa gourmet se cuela en la alta cocina. Retrieved from http://www.abc.es/cultura/abci-hamburguesa-gourmet-cuela-alta-4783250952001-20160302070000_video.html

- Maas-Van Berkel, B., Van Den Boogaard, C., & Heijnen, C. (2004). Preservation of fish and meat (3rd ed. ed.). Wageningen: Agromisa Foundation, Agrodock.

- MAPAMA. (2016). La Alimentación Mes a Mes. Madrid. España: Catalogo de Publicaciones de la Administración General del Estado. Retrieved from http://www.mapama.gob.es/es/ganaderia/temas/produccion-y-mercados-ganaderos/indicadoreseconomicosdelsectorovinoycaprino2015_tcm7-270866.pdf.

- Mariutti, L. R. B., Nogueira, G. C., & Bragagnolo, N. (2011). Lipid and cholesterol oxidation in chicken meat are inhibited by sage but not by garlic. Journal of Food Science, 76(6), 909–915.

- Martínez, L., Cilla, I., Beltrán, J. A., & Roncalés, P. (2006). Antioxidant effect of rosemary, borage, green tea, pu-erh tea and ascorbic acid on fresh pork sausages packaged in a modified atmosphere: Influence of the presence of sodium chloride. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 86, 1298–1307.

- Martínez, L., Djenane, D., Cilla, I., Beltrán, J. A., & Roncalés, P. (2005). Effect of different concentrations of carbon dioxide and low concentration of carbon monoxide on the shelf-life of fresh pork sausages packaged in modified atmosphere. Meat Science, 71(3), 563–570.

- Mastromatteo, M., Conte, A., & Del Nobile, M. A. (2010). Combined use of modified atmosphere packaging and natural compounds for food preservation. Food Engineering Reviews, 2(1), 28–38.

- Mastromatteo, M., Lucera, A., Sinigaglia, M., & Corbo, M. R. (2009). Microbiological characteristics of poultry patties in relation to packaging atmospheres. International. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 44(12), 2620–2628.

- Mills, J., Donnison, A., & Brightwell, G. (2014). Factors affecting microbial spoilage and shelf-life of chilled vacuum-packed lamb transported to distant markets: A review. Meat Science, 98(1), 71–80.

- Newton, K. G., & Rigg, W. J. (1979). The effect of film permeability on the storage life and microbiology of vacuum-packed meat. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 47(3), 433–441.

- Nowak, B., Sammet, K., Klein, G., & Mueffling, T. V. (2006). Trends in the production and storage of fresh meat - The holistic approach to bacteriological meat quality. International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 41(3), 303–310.

- Raghavan, S. (2007). Handbook of spices, seasonings, and flavorings (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, USA: CRC Press-Taylor & Francis Group.

- Rogers, H. B., Brooks, J. C., Martin, J. N., Tittor, A., Miller, M. F., & Brashears, M. M. (2014). The impact of packaging system and temperature abuse on the shelf life characteristics of ground beef. Meat Science, 97(1), 1–10.

- Sallam, K. I., Ishioroshi, M., & Samejima, K. (2004). Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of garlic in chicken sausage. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 37(8), 849–855.

- Sánchez-Escalante, A., Djenane, D., Torrescano, G., Beltrán, J. A., & Roncalés, P. (2001). The effects of ascorbic acid, taurine, carnosine and rosemary powder on colour and lipid stability of beef patties packaged in modified atmosphere. Meat Science, 58(4), 421–429.

- Shahidi, F., Pegg, Z., & Saleemi, Z. O. (1995). Stabilization of meat lipids with ground spices. Journal of Food Lipids, 2, 145–153.

- Shelef, L. A. (1983). Antimicrobial effects of spices. Journal of Food Safety, 6, 29–44.

- Sørheim, O., Nissen, H., & Nesbakken, T. (1999). The storage life of beef and pork packaged in an atmosphere with low carbon monoxide and high carbon dioxide. Meat Science, 52(2), 157–164.

- Suman, S. P., Mancini, R. A., Joseph, P., Ramanathan, R., Konda, M. K. R., Dady, G., & Yin, S. (2010). Packaging-specific influence of chitosan on color stability and lipid oxidation in refrigerated ground beef. Meat Science, 86(4), 994–998.

- Tarladgis, B. G., Pearson, A. M., & Dugan, L. R. (1964). Chemistry of TBA acid test for determination oxidative rancidity in foods II formation TBA MDA complex without Acid-heat treatment. Journal of Science and Food Agriculture, 15(9), 602–607.

- Vergara, H., & Cózar, A. (2015). Aspectos básicos de la conservación de la carne. I. Métodos físicos. Eurocarne, 235, 140–148.

- Vergara, H., & Gallego, L. (2001). Effects of gas composition in modified atmosphere packaging on the meat quality of Spanish Manchega lamb. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 81(14), 1353–1357.

- Viuda-Martos, M., Ruiz-Navajas, Y., Fernández-López, J., & Pérez-Álvarez, J. A. (2010). Spices as functional foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 51(1), 13–28.

- Viuda-Martos, M., Ruiz-Navajas, Y., Fernández-López, J., & Pérez-Álvarez, J. A. (2011). Effect of packaging conditions on shelf-life of mortadella made with citrus fibre washing water and thyme or rosemary essential oil. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2, 1–10.

- Walsh, H. M., & Kerry, J. P. (2002). Meat packaging. In J. P. Kerry, J. F. Kerry, & D. A. Ledward (Eds.), Meat processing. Improving quality (pp. 417–451). Cambridge, UK: CRC Press LLC and Woodhead Publishing.

- Wong, P. Y. Y., & Kitts, D. D. (2002). The effects of herbal pre-seasoning on microbial and oxidative changes in irradiated beef steaks. Food Chemistry, 76(2), 197–205.

- Yanishlieva, N. V., Marinova, E., & Pokorný, J. (2006). Natural antioxidants from herbs and spices. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology, 108(9), 776–793.

- Yin, M., & Cheng, W. (2003). Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of four garlic-derived organosulfur compounds in ground beef. Meat Science, 63(1), 23–28.

- Zaika, L. L. (1988). Spices and herbs: Their antimicrobial activity and its determination. Journal of Food Safety, 9(2), 97–118.