ABSTRACT

Understanding effective marketing decision-making is key to driving business performance. However, knowledge of marketing decision-making by microbusiness owners is limited. Moreover, little is known about how microbusiness owners make marketing decisions under crisis conditions. This article explores entrepreneurial marketing decision-making by women microbusiness owners during the COVID-19 pandemic, through qualitative interviews with providers of children’s activities, who migrated their services online during lockdown. Findings shed light on their marketing decision-making by highlighting transitions between causation and effectuation approaches and identifying key resources leveraged in effectuation decision-making. We also observe how distinct principles of effectuation may be combined to make effective marketing decisions. In addition, we discern interactions within networks and membership of communities of practice as collective influences on women microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making.

Introduction

Effective marketing decision-making is key to an organisation’s success (Chng et al., Citation2015; Joshi & Giménez, Citation2014; Wierenga, Citation2011). While a rich body of research has yielded models and principles to inform marketing decision-making in large organisations (Atuahene-Gima & Murray, Citation2004; Cao et al., Citation2019), understanding of effective entrepreneurial marketing decision-making, undertaken by small, more resource-constrained organisations, is less well-developed (Shepherd et al., Citation2015). Entrepreneurial marketing decision-making frequently employs a means-based effectuation approach (Lam & Harker, Citation2015; Miles et al., Citation2015), as marketing decision-makers draw upon available resources to shape and control decision-making outcomes (Sarasvathy, Citation2009; Sarasvathy & Dew, Citation2005). In contrast, the causation approach, which typically underpins established decision-making models, formulates marketing decisions through extensive planning, detailed analyses of predicted outcomes, and the calculated pursuit of specific goals offering desired returns (Sarasvathy, Citation2001).

Research has explored the application of effectuation and causation by marketing decision-makers in SMEs (e.g. Lehman et al., Citation2020). However, entrepreneurial marketing decision-making in microbusinesses is understudied. Microbusinesses have fewer than 10 employees and/or an annual turnover of less than £2 m (Hutton & Ward, Citation2021). Globally, approximately one in three people is employed by a microbusiness (OECD, Citation2019) and, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, microbusinesses accounted for 96% of private sector businesses in the UK (Hutton & Ward, Citation2021) and 91% in Ireland (Central Statistics Office, Citation2019). Microbusinesses represent key sources of economic growth (Evans & Wall, Citation2020). Consequently, enriching knowledge of effective marketing decision-making by microbusinesses has the potential to facilitate the development and continuity of these enterprises, and thus to support local and national economies.

We therefore explore entrepreneurial marketing decision-making by microbusiness owners. Specifically, we examine microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic. The emergence of COVID-19 created a global crisis, with conditions of extreme uncertainty for organisations (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020). Entrepreneurial marketing decision-making theory and research contends that, in uncertain conditions, effectuation is a more effective approach to decision-making than causation (Sarasvathy, Citation2001). To date, however, the application of effectuation and causation approaches to marketing decision-making by microbusiness owners during a crisis is unexplored.

Furthermore, we focus on women microbusiness owners. Entrepreneurship by women has received notably less scholarly attention than that of men (Deng et al., Citation2021; Ogbor, Citation2000), leading to calls for research into women’s entrepreneurial activity (Ahl, Citation2006; Lewis, Citation2015). Professional women were often disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 (UN Women, Citation2020; World Economic Forum, Citation2020), suggesting that women microbusiness owners faced significant challenges in managing both their home and business-related activities. Intuitively, where women microbusiness owners were able to continue trading during the COVID-19 pandemic, their success was likely due, in part, to effective marketing decision-making. Their marketing decision-making during the pandemic period therefore represents a rich context for our first research question: How do women microbusiness owners apply effectuation and causation in entrepreneurial marketing decision-making during a crisis?

Studies of entrepreneurial decision-making traditionally adopt an individualistic perspective (Reich, Citation1987; Schjoedt & Kraus, Citation2009). However, a contrasting body of research highlights collective influences on entrepreneurial decision-making (Yan & Yan, Citation2016), such as an entrepreneur’s social context (Dimov, Citation2007; Drakopoulou Dodd & Anderson, Citation2007), entrepreneurial teams and networks, and communities of practice comprising entrepreneurs who engage in collaborative decision-making (Bergh et al., Citation2011; Jack et al., Citation2010; Lefebvre et al., Citation2015). Collective influences on women microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making have yet to be explored, and our second research question, therefore, is: What are the collective influences on women microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making during a crisis?

We explore microbusinesses in the UK and Ireland that provide group activities to pre-school or school-age children, such as sports, music, dance, and extra-curricular education. These businesses offer valuable services to local communities, supporting customer wellbeing in diverse ways (Holder et al., Citation2009). The role of these organisations grew in importance during periods of lockdown, imposed by the UK and Irish governments due to the emergence of COVID-19, and during which the wellbeing of children and young people suffered (Sancho et al., Citation2021). Schools were predominantly closed, so parents relied upon these microbusinesses to provide their children with an element of routine, opportunities for physical exercise, and the chance to socialise with friends, all of which have been shown to enhance wellbeing among children (Sancho et al., Citation2021). The women microbusiness owners who participated in this research continued to provide activities for children during lockdown by migrating their previously face-to-face and group-based activities online.

We explore our research questions through a qualitative study, adopting a semi-structured interviewing approach. We contribute by, first, enriching knowledge of effectuation and causation in entrepreneurial marketing decision-making during a crisis by evidencing transitions between effectuation and causation approaches, providing enhanced granularity regarding effectuation processes, and shedding light on the nature of resources leveraged in effectuation. In addition, we observe how the outcomes of effectuation decision-making inform subsequent causation decision-making. Second, we extend knowledge of collective influences on entrepreneurial marketing decision-making by highlighting that, during a crisis, information gleaned from the social context influences marketing decisions, and that membership of communities of practice facilitates collective effectuation. Third, by providing insight into entrepreneurial marketing decision-making by women microbusiness owners, we contribute to literature on women’s entrepreneurship.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, we review the literature on entrepreneurial marketing decision-making to clarify the research gaps. Subsequent sections detail the method, present findings, and discuss resultant contributions.

Literature review

Microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making

Marketing scholars agree that insight into marketing decision-making is fundamental to understanding firm performance (Chng et al., Citation2015; Joshi & Giménez, Citation2014; Wierenga, Citation2011). Established marketing decision-making theory offers various principles, processes, and models, to guide marketing managers in making marketing decisions (see e.g. Atuahene-Gima & Murray, Citation2004; Cao et al., Citation2019; Challagalla et al., Citation2014; Joshi & Giménez, Citation2014). Established marketing decision-making theory is, however, predominantly derived from research into marketing by large organisations (Read et al., Citation2009). Consequently, the use of extant marketing decision-making theory in understanding marketing decision-making within microbusinesses is often inappropriate (Bocconcelli et al., Citation2018; Jones & Rowley, Citation2011). Rather, an alternative approach, termed entrepreneurial marketing, is frequently associated with the marketing activities of smaller enterprises, including microbusinesses (Liberman-Yaconi et al., Citation2010; Miles et al., Citation2015; Sadiku Dushi et al., Citation2019).

Scholars of marketing and entrepreneurship acknowledge that entrepreneurial marketing activities are different to traditional marketing activities (Gilmore, Citation2011; Ionita, Citation2012; Morrish & Jones, Citation2020). Entrepreneurial marketing is, for instance, often unplanned, instinctive, non-linear, and supported heavily by networking (Hills et al., Citation2008; Morrish & Jones, Citation2020; Sadiku Dushi et al., Citation2019). Entrepreneurial marketing theory is informed by an understanding of how entrepreneurs make marketing decisions (Miles et al., Citation2015). Specifically, the entrepreneurial marketing decision-making process is often underpinned by an effectuation approach (Lam & Harker, Citation2015; Miles et al., Citation2015). Sarasvathy (Citation2001) delineated causation and effectuation as distinct decision-making processes, though both are integral to human reasoning and may occur simultaneously (Galkina & Jack, Citation2022; Reymen et al., Citation2015). Causation processes generate marketing decisions through extensive planning, detailed analyses of predicted outcomes, and the calculated pursuit of pre-determined goals which offer desired returns (Sarasvathy, Citation2001). In contrast, effectuation is a means-based, control-oriented approach to decision-making, in which individuals apply their creativity, skills and experience to the use of available resources, in order to shape marketing decisions (Sarasvathy, Citation2009; Sarasvathy & Dew, Citation2005). Sarasvathy and Dew (Citation2005) and Sarasvathy (Citation2009) identify five principles of effectuation: (1) the ‘bird in the hand’ principle, which refers to a means-based orientation whereby decision-makers assess and leverage available resources, rather than adopting a goal-driven approach to action; (2) an ‘affordable loss’ principle, which entails assessing what one is willing to lose rather than investing in anticipated returns; (3) the ‘crazy quilt’ principle, which refers to the activity of exploring relationships with many potential stakeholders (such as suppliers and customers) with a view to determining which will succeed and thus lead to market co-creation; (4) the principle of ‘making lemonade’, which captures attitudes towards unexpected events and the leveraging of difficult situations to create positive outcomes; and (5) the ‘pilot in the plane’ principle, which reflects a focus on what can be controlled in the present rather than on activity in future years.

The study of entrepreneurial marketing is bourgeoning (Ferreira et al., Citation2019). However, understanding of entrepreneurial marketing decision-making is underdeveloped and knowledge of how effectuation and causation are effectively applied to marketing decision-making is fragmented (Bocconcelli et al., Citation2018; Lehman et al., Citation2020). Prior studies have explored the use of effectuation and causation by marketing managers in hypothetical scenarios relating to new business development (Read et al., Citation2009), declining business performance (Chng et al., Citation2015), and in the establishment of new, technology-based SMEs (e.g. Lehman et al., Citation2020). In contrast, there has been limited investigation of entrepreneurial marketing decision-making within service industries (Altinay & Arici, Citation2021) and, to date, microbusiness owners’ application of effectuation and causation processes to marketing decision-making remains underexplored.

Microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making in a crisis

Crises are the result of external events as diverse as terrorism, extreme weather, a pandemic, adverse economic conditions, and localised problems such as disruptions to infrastructure (Young et al., Citation2017). Crisis conditions are characterised by low probability of occurrence, conditions of extreme uncertainty for firms, high consequence, and time-pressured decision-making (Runyan, Citation2006). Within markets, crises can hamper supply chain activities and impact customer demand (Manolova et al., Citation2020). In contrast with large organisations, microbusinesses may be particularly at risk of disruption by crises as their operations often rely on internally generated cash flow and they frequently lack access to external capital (Cowling et al., Citation2020). However, an alternative perspective asserts that small, entrepreneurial businesses might be more resilient to crises than large firms, due to their ability to adjust their business models in recognition of emerging opportunities (Newman et al., Citation2022; Smallbone et al., Citation2012), resulting in improved business performance (Charoensukmongkol, Citation2022; Kusa et al., Citation2022). To adapt to crisis conditions requires effective marketing decision-making as part of business model adaptation (Keiningham et al., Citation2020).

A rich stream of research explores how organisations plan for and respond to crises (see e.g. Coombs & Laufer, Citation2018). However, the crisis management and entrepreneurship literatures offer limited knowledge of how microbusinesses respond to crises (Budge et al., Citation2008; Herbane, Citation2013; Khurana et al., Citation2022; Newman et al., Citation2022; Stephens, McLaughlin, et al., Citation2021). This has led to calls within the entrepreneurship literature for a greater focus on the role of entrepreneurs, particularly those who own their businesses, in navigating crisis situations (Newman et al., Citation2022). Prior studies of microbusinesses’ responses to crises have highlighted a typical lack of formal crisis planning (Budge et al., Citation2008; Herbane, Citation2013; Irvine & Anderson, Citation2004) and focused predominantly on the post-crisis period (Doern, Citation2016). A small body of studies during the COVID-19 pandemic has yielded insight into how microbusiness owners ensured business continuity during periods of lockdown by, for example, shortening supply chains, adjusting customer payment mechanisms (Fabeil et al., Citation2020), using social media and online platforms to advertise and sell goods (Hamdan et al., Citation2021), and pivoting business models to serve new markets in new ways (Manolova et al., Citation2020). However, research to date has not examined microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making processes during a crisis.

Sarasvathy (Citation2001) contends that, due to its emphasis on control rather than prediction, effectuation is a more effective approach to decision-making than causation in uncertain situations. Studies of marketing decision-making in crisis scenarios have explored the application of effectuation and causation by SMEs, evidencing the benefits of an effectuation approach. Specifically, an ability to apply an effectuation approach to decision-making affords flexibility and adaptability in an uncertain, changing environment, and enables SMEs to recognise and capitalise upon opportunities to, for example serve new market segments or develop new products or services (Altinay & Arici, Citation2021; Laskovaia et al., Citation2019; Shirokova et al., Citation2020). However, microbusiness owners’ application of effectuation or causation to marketing decision-making in a crisis remains unclear.

Collective influences on microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making

While entrepreneurial marketing is a useful lens for exploring marketing decision-making by microbusiness owners (Liberman-Yaconi et al., Citation2010; Miles et al., Citation2015; Sadiku Dushi et al., Citation2019), entrepreneurship research has traditionally adopted an individualistic perspective, viewing the entrepreneur as a self-made, independent, and lone maverick (Busenitz et al., Citation2003; Cooney, Citation2005; Reich, Citation1987; Schjoedt & Kraus, Citation2009). However, a growing body of scholars asserts that failing to explore collective influences on entrepreneurial decision-making limits our understanding of resultant organisational growth (Yan & Yan, Citation2016).

Consequently, researchers have highlighted the role of the social context. Specifically, entrepreneurs’ interactions within social networks provide valuable insight, interpretation, resources and feedback, which inform entrepreneurial decision-making (Dimov, Citation2007; Drakopoulou Dodd & Anderson, Citation2007). Evidencing further collective influences on entrepreneurial decision-making, researchers highlight entrepreneurial teams (Cooney, Citation2005; Lazar et al., Citation2020; Patzelt et al., Citation2021) and entrepreneurial networks (Jack et al., Citation2010), which are formal peer groups, the members of which benefit from the provision of access to information, advice and collaborative problem solving (Bergh et al., Citation2011; Jack et al., Citation2010). Entrepreneurial networks may evolve into communities of practice (CoPs) (Lefebvre et al., Citation2015), which are ‘groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis’ (Wenger et al., Citation2002, p. 4). CoPs represent social learning systems (Wenger, Citation2010), and the primary output of CoPs is knowledge, which can improve business performance by, for instance, informing decision-making (Lesser & Storck, Citation2001; Wenger & Snyder, Citation2000).

While the entrepreneurship literature highlights collective influences on decision-making in relation to business development, innovation and problem-solving (Lefebvre et al., Citation2015), there is scope for increased insight into collective influences on entrepreneurial marketing decision-making, such as that undertaken by microbusiness owners. Moreover, studies have yet to examine collective influences on effectuation and causation in marketing decision-making (Ben-Hafaidedh et al., Citation2022). In addition, collective influences on marketing decision-making by microbusinesses owners in responding to a crisis is largely unexplored, though examples of research into collective activity by microbusiness owners during the COVID-19 pandemic can be found (e.g. Ratten et al., Citation2021; Stephens, Cunningham, et al., Citation2021)

Furthermore, prior research has not explored the potential for CoPs comprising microbusiness owners, or the role that membership might play in supporting these enterprises during a crisis. However, research highlights the beneficial role played by CoPs during the COVID-19 pandemic (see e.g. Delgado et al., Citation2020; McLaughlan, Citation2021; McQuirter, Citation2020; Mead et al., Citation2021) with evidence of CoP adaptation and changing focus, (McLaughlan, Citation2021; McQuirter, Citation2020; Mead et al., Citation2021), of increasing member participation, and a growth in collaborative activity (Delgado et al., Citation2020; McLaughlan, Citation2021). Additionally, new CoPs emerged during the pandemic to focus on specific challenges (Delgado et al., Citation2020; Gachago et al., Citation2021). Intuitively, as microbusiness owners are likely to have faced new challenges during the pandemic which were also experienced by other microbusinesses, CoPs comprising microbusiness owners may have emerged.

Women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making

In addition to an individualistic view, entrepreneurship research has traditionally adopted a male-dominated perspective (Ahl, Citation2006). Entrepreneurs are typically assumed to have masculine personality attributes (Ogbor, Citation2000) and to adhere to a heroic male archetype (Lewis, Citation2015). Conversely, women business owners have received less scholarly attention than their male counterparts within the entrepreneurship literature (Ogbor, Citation2000).

In response, scholars are increasingly exploring entrepreneurship by women (Deng et al., Citation2021) and women’s approaches to entrepreneurial decision-making (Shepherd et al., Citation2015). Findings suggest that women are more risk-averse than men under normal conditions (Manolova et al., Citation2020) and in the event of a crisis (e.g. Maxfield et al., Citation2010), and may typically favour a causation approach to decision-making over effectuation (Melo et al., Citation2019). However, studies are limited in number and findings are inconsistent (see e.g. Manolova et al., Citation2020; Maxfield et al., Citation2010), and research to date has not yielded insight into women microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making in a crisis scenario.

A concurrent narrative challenges the value of research exploring differences between men and women entrepreneurs, due to evidence of considerable heterogeneity within men and women (Shepherd et al., Citation2015) which weakens any gender-based conclusions. Furthermore, Ahl (Citation2006) argues that to differentiate between entrepreneurs on the basis of their gender risks perpetuating perceptions of women entrepreneurs as being subordinate to men. There is an argument, therefore, for research that surfaces the voices of women entrepreneurs independently from, rather than in contrast with those of men, thus developing a more holistic, non-gendered understanding of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial decision-making.

Accordingly, in this study we do not compare men and women microbusiness owners. Rather, our rationale for exploring microbusiness owners who are women stems from evidence that they represent one of many groups for whom conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic were particularly challenging (UN Women, Citation2020; World Economic Forum, Citation2020). Specifically, women-owned microbusinesses are typically concentrated in service industries requiring contact with customers (Anna et al., Citation2000), meaning that lockdowns and social distancing requirements were particularly disruptive. Additionally, women tended to carry greater household responsibilities than men during the pandemic, devoting more time to housework and caring responsibilities (Minello, Citation2020; Vincent Lamarre et al., Citation2020) and to home schooling (Hughes et al., Citation2022; OECD, Citation2020). The resulting documented time pressures made it difficult to run a microbusiness successfully (Hughes et al., Citation2022; OECD, Citation2020). We contend, therefore, that where women microbusiness owners successfully continued operating their businesses during periods of lockdown, their success was in part the result of effective entrepreneurial marketing decision-making. Thus, by exploring the marketing decision-making processes of women microbusiness owners during the pandemic, we are able to shed meaningful light upon effective entrepreneurial marketing decision-making, undertaken by women, during a crisis.

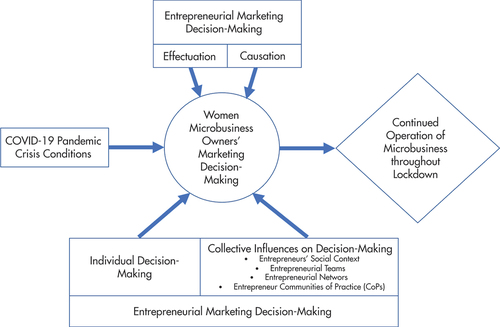

In we present a synthesis of insights, derived from our review of literature. serves as a framework for our empirical study, to which we now turn, and in which we extend current knowledge of entrepreneurial decision-making during crisis conditions.

Methodology

As this was an exploratory study, we adopted a qualitative approach (Cassell & Symon, Citation2004) to understand women microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making in response to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown restrictions. We followed a purposive sampling approach in selecting study participants (Bryman, Citation2016), which enabled us to access information-rich cases with a specific set of criteria. We applied the following criteria for inclusion: (1) participants had to be women; (2) to qualify as a microbusiness owner, they needed to be responsible for the day-to-day operation and future direction of a business employing fewer than ten people (Hutton & Ward, Citation2021); (3) their business had to provide services to children; (4) so we could explore marketing decision-making in response to the COVID-19 lockdown, participants’ businesses must have been in operation prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and remained operational during the lockdown period by moving online.

In addition, participants were required to be operating their businesses in the UK or the Republic of Ireland. Our goal was not to compare participants from these countries but to treat microbusinesses owners in these two nations as a single population of interest. Studies of samples comprising British and Irish businesses can be found elsewhere in the management research literature (see e.g. Panagiotopoulos et al., Citation2015), due, in part, to the similar cultural context and business environment in these countries. Moreover, the UK and Irish governments imposed equivalent ‘stay at home’ lockdown conditions at similar times; the UK entered lockdown on March 23rd 2020 and Ireland did so on March 27th 2020. Consequently, at the point of recruitment, microbusiness owners in these nations had had comparable lengths of time to respond to very similar lockdown-related challenges. We did not apply a criterion relating to the age of the business as both novice and experienced business owners may apply effectuation and causation approaches to decision-making (Laskovaia et al., Citation2017).

Following Galkina and Jack (Citation2022) and Patton (Citation2002), we selected participants from a single industry sector. Specifically, we recruited owners of microbusinesses that provided activities to children up to the age of 18. Our rationale for focusing on this group of microbusiness owners is that prior to the pandemic, they typically delivered exclusively face-to-face services. Consequently, lockdown was likely to have had a particularly detrimental impact on these participants and their resultant marketing decision-making was, therefore, likely to have been highly pertinent in determining whether their businesses survived such adverse conditions. Consequently, we contend that a focus on this under-researched industry (Altinay & Arici, Citation2021) offers rich insights into the phenomenon of interest.

Recruitment began in early June 2020. Initially, the research team drew upon their personal networks, directly approaching suitable candidates with an invitation to participate. The study was also promoted on social media platforms. LinkedIn was deemed important to capture business owners and relevant groups on Facebook were also targeted. Despite not fitting the established criteria for ‘hard-to-reach populations’ (that is, small population size, difficult to identify and/or to contact population members, or members who do not identify as such (Marpsat & Razafindratsima, Citation2010)), recruitment was initially challenging. This was due, in part, to the adverse conditions experienced by suitable participants at the time of recruitment (Hughes et al., Citation2022; OECD, Citation2020), which led many to decline citing a lack of time. Consequently, and mirroring other studies of hard-to-reach populations (e.g. Abrams, Citation2010), we adopted a snowball approach to sampling, drawing upon the networks of our initial participants to recruit further women microbusiness owners to our study. Ultimately, twenty-four potential participants were identified from the research team’s own networks, responses to social media posts, and participants’ networks. Thirteen agreed to be interviewed, all of whom were based in various locations in England and in the Dublin area of Ireland. This gave a sample size which markedly exceeded the number of participants in other studies of women microbusiness owners during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as that of Hamdan et al. (Citation2021) (six interviewees), Fabeil et al. (Citation2020) (two interviews), and Manolova et al. (Citation2020) (two case studies).

summarises the nature of the participants’ service, their location, number of employees, and age of business. shows participants’ use of digital technology in their marketing activity prior to lockdown and illustrates how, for all participants, transferring their classes online represented a new endeavour. In , pseudonyms have been used to ensure participant anonymity.

Table 1. Study participants.

Table 2. Participants’ use of digital technology in marketing activities prior to lockdown.

As shows, some participants’ businesses were franchises. While there is an argument within the entrepreneurship literature that franchisees are managers rather than entrepreneurs, Clarkin and Rosa (Citation2005) demonstrate entrepreneurship among franchisees. In addition, like non-franchisee microbusiness owners, franchisees typically invest personal resources in establishing their enterprises and assume responsibility for the successful running of their business (Kaufmann & Dant, Citation1999). While franchisees vary in the extent of their decision-making freedom (Kaufmann, Citation1999), all study participants met the project’s recruitment criteria. Moreover, as shows, while all franchisee participants received guidance from the franchisor in responding to lockdown conditions, the extent of support varied and all participants were ultimately responsible for marketing decision-making in response to the imposition of lockdown conditions. Pseudonyms have been used in to ensure participant anonymity.

Table 3. Support provided by franchisor to franchisee.

To collect data, we conducted individual interviews with study participants. Ratten et al. (Citation2021) argue that data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic required flexible approaches due to the challenges likely faced by participants. Consequently, interviews were scheduled at a time that suited each participant and it was agreed to limit them to 30 minutes, although several participants were happy to continue for longer (up to 46 minutes). Interviews were conducted by telephone as lockdown restrictions prevented any face-to-face communication and we were prohibited by institutional research ethics regulations from using video conferencing software, such as Zoom or MS Teams.

Interviews adopted a semi-structured approach; that is, the interviewer aimed to discuss a series of topics, designed to reveal each participant’s experiences of marketing decision-making in response to the COVID-19 lockdown. In practice, interviews resembled conversation and we began each by asking: ‘Can you tell me about your business?’ This was followed by questions that explored participants’ marketing decision-making before the COVID-19 pandemic, at the point at which national lockdowns were announced, and during the period after lockdown came into effect. We discussed participants’ individual decision-making and any collective influences on their decision-making process. We also discussed participants’ future plans for their businesses. We were mindful that recounting personal experiences of the pandemic could be upsetting for participants, so allowed participants to lead the discussion and decide what they were comfortable in disclosing. In addition, interviewers adopted a flexible and empathetic approach, which included pauses for participants to attend to customers or children if necessary. Several participants reported finding the opportunity to reflect on what happened during the pandemic to be cathartic as their busy schedule did not usually allow for this.

Data collection took place between June and September 2020, meaning that the UK and Ireland had been in lockdown for between two and six months at the time of each interview. As lockdown had been recently imposed, participants could easily recall and reflect upon their marketing decision-making during this period. At the time of data collection, some restrictions in the UK and Ireland were scheduled to be lifted, but it was not expected that conditions would return to their pre-COVID-19 state in the short term. Also, there was an anticipated ‘second wave’ of COVID-19 infections with an associated risk of future lockdowns. Consequently, participants’ marketing decision-making remained surrounded by uncertainty, meaning that participants were able to discuss marketing decisions pertaining to the more imminent and the longer-term futures of their business.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, yielding 144 pages of transcript. Transcripts were analysed with the aid of the NVIVO software package. We adopted an inductive approach to data analysis, drawing on elements of grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967) which provides a rigorous set of procedures for analysing data (Thornberg & Charmaz, Citation2014). We adapted Corbin and Strauss’ (Citation1990) Classification of Coding in Grounded Theory and worked as a team, critically reviewing each other’s analysis to avoid researcher-induced bias. First, we individually read the transcripts and open coded all the data, identifying commonalities in the transcripts. At this stage, we identified the key areas of marketing decision-making discussed by interviewees and delineated data relating to individual decision-making and collective influences on the decision-making process. We then revisited the data and our initial codes, refining our analysis by creating more specific codes (e.g. relating to decision-making around specific marketing activities), developing higher levels of abstraction and allowing themes to emerge. This enabled us to achieve a more granular and nuanced understanding of participants’ marketing decision-making. Third, we applied selective coding, to formulate key thematic categories which we used to structure and inform our findings and discussion section.

Findings and discussion

We develop a picture of women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making following the imposition of national lockdown conditions in the UK and Ireland. We observe that in response to COVID-19 lockdown, women microbusiness owners adopted an effectuation approach to marketing decision-making. In particular, they focused on decisions around service design and delivery, pricing, and customer communications during the lockdown period. In addition to individual decision-making, we highlight collective influences on marketing decision-making by women microbusiness owners, as they reflected upon knowledge gleaned from the social context of their businesses and participated in CoPs. Moreover, when lockdown conditions looked to ease, women microbusiness owners adopted a causation approach to marketing decision-making, informed by their experiences of an effectuation approach during lockdown.

In the following sections we discuss these observations, adopting a structure which reflects the conceptual framework in . We first discuss findings relating to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis conditions before presenting observations around effectuation and causation approaches to individual entrepreneurial marketing decision-making, followed by findings relating to collective influences on entrepreneurial marketing decision-making.

Marketing decision-making in a crisis: from causation to effectuation

The imposition of lockdown created a crisis situation for participants, with significant consequences (as participants were prevented from operating their businesses), time-pressured decision-making (as they needed to determine quickly how to continue trading), and extreme uncertainty (as it was not known how long lockdown would last) (Runyan, Citation2006). Despite extensive media coverage surrounding the global spread of COVID-19, participants were not prepared for the potential impact of government-imposed lockdowns on their businesses, as Abby described:

Abby: ‘We were getting the news from Italy. Friends there had gone into lockdown, their jobs had stopped. So we were sort of anticipating it, but when lockdown happened it was like, whoa, what’s going to happen now?’

Our findings therefore echo previous studies of microbusiness owners (Budge et al., Citation2008; Irvine & Anderson, Citation2004) as we find that participants had not engaged in crisis planning prior to the COVID-19 lockdown.

In response to these crisis conditions, participants’ adjusted their approach to marketing decision-making and deprioritised long-term business goals, as Jane describes:

Jane: ‘Before COVID I was considering buying three more franchise territories, going all the way to the coast but just in the more affluent areas. I was hoping to build my business that way, but everything’s on a hold for now. It [COVID-19] has put a stop to that at the moment.’

Participants described a shift in focus from long-term planning to short-term business continuity, and a resultant approach to marketing decision-making that focused on what could be controlled in the short term, rather than on future activity. This reflects the ‘pilot in the plane’ principle of effectuation decision-making (Sarasvathy, Citation2009) and we therefore identify a transition in approach to marketing decision-making from causation to effectuation, thus supporting Sarasvathy’s (Citation2001) contention that an effectuation approach to decision-making is more beneficial in uncertain conditions.

Participants’ marketing decision-making during lockdown focused on: (1) service design and delivery; (2) pricing; and (3) customer communications. In the following sections we discuss each area of focus in turn.

Service design and delivery

Participants’ marketing decisions around service design and delivery related to how to run their previously face-to-face and interactive classes online. Specifically, participants needed to determine which, if any, activities usually undertaken in their classes could be offered online, and how children would take part in those activities. We found that service design and delivery decisions reflected the means-based ‘bird-in-the-hand’ principle of effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009) as participants assessed what resources were available to them, then leveraged them.

For example, where it was feasible to do so, service providers drew upon existing service designs as key resources, in the form of established face-to-face class routines that could be replicated in online delivery. This ensured some continuity for customers. Liz described her approach:

Liz: ‘I kept it [online classes] pretty similar actually and the structure of the class was the same as we would do in face-to-face classes, but obviously you were having to spend more time describing what it was you were trying to do.’

For some participants, due to the nature of their classes it was impossible to deliver established face-to-face class structures online. In these cases, online sessions focused on familiar elements of face-to-face class structures. For example, Lucy was unable to offer gymnastics coaching online for safety reasons (‘[I] didn’t want anyone doing a handstand and crashing into the coffee table’). She therefore designed her online classes to focus on strength and fitness activities with which class members were familiar, and which allowed members to retain skills developed in face-to-face settings.

Participants typically delivered their classes using accounts set up with widely available online platforms such as Facebook, Zoom and YouTube, though some also used bespoke apps tailored to their particular activity. These technologies served as fundamental resources, leveraged by participants to connect with class members in real-time, or to record sessions that customers could access when they chose. To deliver online classes, participants also drew upon their relationships with the parents of existing class members, developed through pre-lockdown face-to-face interactions. These existing customer relationships proved to be an important resource, as participants relied upon parents’ involvement in co-creating the online service experience. For instance, participants typically sent log-in details by email to parents, who then facilitated their child’s participation in the session by, for instance, logging them in to Zoom. In addition, participants often asked parents to provide resources for use during class. Alice described such a scenario:

Alice: ‘In class we’d quite often use coloured scarfs, so I was like: “Mums, go and find me a tea towel or something” so they could still do similar stuff.’

Similarly, Eleanor’s classes involved the use of ‘pots and pans’ while Lucy’s exercise classes revolved around a different prop each week:

Lucy: ‘Each week we pick something they need to have with them, say a chair that they need to do some of the exercises. One week it was a cushion, one week it was a toilet roll.’

An effectuation approach to marketing decision-making around service design and delivery is also evidenced in participants’ ability to ‘make lemonade’ (Sarasvathy, Citation2009). That is, in addition to leveraging existing class routines in service design decisions, participants also demonstrated creativity in offering novel activities to customers. This entailed drawing on available resources in new ways, creating positive outcomes despite the challenging lockdown conditions. Ruth, for example, designed an online activity, never previously offered to children in face-to-face sessions:

Ruth: ‘Some of the children were saying to me before lockdown, they were disappointed that the St Patrick’s parades weren’t happening. I asked them why. They told me that they liked getting ice cream at the parade. So, I said I’ll make mint green ice cream with you online, on St Patrick’s day and you can do it on the computer. About 200 people joined in online.’

Alice also demonstrated the ‘making lemonade’ principle by leveraging the Zoom platform and her employees’ skills to run a social event:

Alice: ‘We did a “big night in”. We did it for two hours one Saturday evening and all of my teachers came online and did something. I did dances with them, my singing teacher did Disney karaoke, one of the teachers did a bedtime story, the other one played a game with them, we watched a film with them. It worked really well and was great fun’

In identifying participants’ application of the ‘bird in the hand’ and ‘making lemonade’ principles of effectuation (Sarasvathy & Dew, Citation2005; Sarasvathy, Citation2009) to marketing decision-making around service design and delivery, we highlight the leveraging of a diverse set of resources, some of which are owned by the participant: established service designs, subscriptions to online platforms, relationships with employees and existing customers. Other leveraged resources are owned by people within the participant’s networks; specifically, employees’ skills and customers’ own resources. We therefore extend knowledge of women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making by illustrating their adoption of an effectuation approach in a crisis scenario and by shedding light on the nature of the resources leveraged in doing so.

Pricing

Participants’ marketing decision-making during lockdown included decisions around how much to charge for online classes. Microbusinesses’ typical reliance on internally generated cash flow (Cowling et al., Citation2020) resulted in a need for participants to continue generating revenue during lockdown. Consequently, all continued to charge fees for their classes. Alice, Amy, Louise, Lucy, and Sheila charged lower prices for online classes while the remaining participants retained their pre-lockdown prices. The decision to reduce fees was informed by the costs incurred by participants during lockdown, as Amy (who felt able to reduce her fees) and Lucy (who did not) explained:

Amy: ‘I don’t pay the rent for our facility, so I was able to really reduce our prices and keep enough income to make sure that my coaches are paid.’

Lucy: ‘In this environment there’s so many extra costs involved in postage and delivery. Then it’s a large franchise fee for every student, your insurance and your tax and your employees. So you’re not gaining much on each student. In the longer term I’d have to charge more to do things this way, but I won’t for now because I don’t want to put that pressure on parents at the moment.’

In addition, decision-making regarding pricing also assumed that customer numbers would reduce, creating financial pressures for participants, as Kate described:

Kate: ‘I did look at lowering my class price, but I knew that I was going to lose a lot of customers, so I kept my class prices the same.’

Marketing decision-making around pricing, then, involved participants’ assessment of what they were willing to lose. In Amy’s case, she was willing to lose revenue, though not to the extent that she couldn’t afford to retain her employees. Kate, in contrast, aimed to limit her loss of revenue by maintaining pre-lockdown prices. This reflects the ‘affordable loss’ principle of effectuation decision-making (Sarasvathy, Citation2009).

Whether or not they adjusted their pricing, all participants offered more classes per week than before lockdown. In doing so, they sought to offer customers greater value for money by offsetting the loss of interactivity and personal contact created by a move to online classes with increased opportunities to join online activities. Amy demonstrated this approach:

Amy: ‘If a child was only registered to do cheerleading, we had a minimum fee and for the lockdown period they could access any style of dance as much as they wanted.’

This further illustrates the use of the ‘bird in the hand’ principle of effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009) as participants leveraged existing resources to deliver additional classes to customers in what they assumed would be the short term. In turn, by offering greater value for money, participants sought to retain customers and thus reduce the risk of revenue loss that they would incur if customers refused to pay for online classes during lockdown.

In exploring participants’ marketing decision-making around pricing, we enrich knowledge of an effectuation approach to marketing decision-making as we highlight the combination of the ‘affordable loss’ and ‘bird in the hand’ principles (Sarasvathy, Citation2009). Specifically, while participants assessed their potential loss of revenue and determined what was acceptable, they simultaneously made decisions around increased leveraging of resources and delivery of additional classes, which sought to offer greater value to and to retain customers, thus reducing the potential loss of revenue.

Customer communications

Prior to lockdown, participants continuously sought to recruit new customers and, therefore, grow their businesses. However, due to the complex and challenging conditions during lockdown, participants’ priorities shifted to the retention of existing customers, as Amy described:

Amy: ‘I kept it very low key for my own customers. There was so much going on, the thought of trying to bring in people that I didn’t know into that mix of things … I just focused on my customers.’

To retain existing customers, in addition to pricing decisions discussed in the previous section, participants’ marketing decision-making during lockdown included decisions regarding how to communicate with existing customers. Prior to lockdown, participants’ face-to-face contact with class members and parents was key to communication and the development and maintenance of customer relationships. Lockdown rendered face-to-face contact impossible, necessitating alternative approaches to communication. Decision-making around communications with existing customers reflected the ‘bird in the hand’ principle of effectuation, as service providers drew upon available resources in the form of established channels of communication (Sarasvathy, Citation2009). Kate, for example, used her existing social media to maintain contact with customers who did not participate during lockdown:

Kate: ‘I’ve kept up my social media, just to keep us in people’s minds, which I think is really important. If they can’t join us for the online classes, that’s absolutely fine, but it’s just keeping us relevant.’

In addition, some providers communicated with existing customers in new ways and for new purposes. For example, Ciara described speaking by telephone to young martial arts students who experienced low motivation during lockdown while Alice encouraged a staff member to support their young dancers with their school work:

Ciara: ‘Some parents called us saying: ‘They’re fed up with lockdown and we can’t get them to do it [online class], can you have a chat with them?’ I did a few video messages and sent them to the parents to show the children saying: ‘Come on, you can do it!’ or I’d phone them if they were struggling to find the motivation to do the class.’

Alice: ‘One of my teachers, throughout lockdown she’s been phoning up the kids that have been struggling with their homework. It’s not dance-related at all, they’ve been struggling with maths homework or whatever. She’s been calling them and doing Zooms with them and helping them with their homework when their parents are busy.’

Ciara and Alice, therefore, further demonstrate the ‘making lemonade’ principle of effectuation in their approach to marketing decision-making as they were able to create positive outcomes (that is, a motivated or an educated child) from difficult situations (Sarasvathy, Citation2009).

Several participants described ‘freezing’ the memberships of children whose parents were unwilling to pay for classes online. In some cases, such as with Alice’s class members, those who froze their membership had no access to online classes but were included in customer communications during lockdown and assured of a place when face-to-face classes recommenced. Other participants, such as Ciara and Amy, allowed customers who chose not to pay fees limited access to online classes:

Ciara: ‘Customers had the choice whether they froze their membership or whether they carried on their payments. If they carried on they got the online lessons, one-to-ones with the instructors, whereas anyone who froze their lessons, they could join in on Facebook or YouTube.’

Amy: ‘Those who couldn’t do online classes weren’t closed off. We were still putting things on our page so if they weren’t paying for classes, they were still getting access to some dances here and there.’

By freezing memberships and maintaining contact, participants sought to retain relationships with existing customers, even though those customers were not generating any revenue. This demonstrates the ‘pilot in the plane’ principle of effectuation, as participants focused on what they could control rather than on the unfamiliar task of new customer recruitment in such complex conditions.

In observing participants’ marketing decision-making around customer communications, we provide further evidence of the application of the ‘bird in the hand’ and ‘making lemonade’ principles of effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009), and highlight the leveraging of further resources (existing and new channels of communication) in doing so.

Collective influences on marketing decision-making in a crisis

Data yielded evidence of collective influences on participants’ marketing decision-making, supporting the argument within the entrepreneurship literature that entrepreneurs are not independent mavericks (Reich, Citation1987). Participants’ accounts captured the socially embedded nature of their business; specifically, interviewees reflected upon how social interactions yielded information and feedback that reflected the social context and influenced their decision-making around service design and delivery. For example, Lucy’s decision to adapt her classes to provide strength exercises was informed by her communications with the parents of some of her gymnasts:

Lucy: ‘We were being told [by governing body]: no online classes, you’re not covered for insurance. And there was a few gymnasts that I was worried about, a few that were having anxiety issues that the parents told me about. So we decided, we need to do something for these gymnasts. They’ve done all the strength work and they’re going to lose it very quickly if they don’t get back to it.’

Lucy provides further evidence of an effectuation approach to marketing decision-making, demonstrating a ‘bird in the hand’ orientation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009) by leveraging available resources (gymnasts’ and coaches’ existing skills, space in homes and an online platform). However, in being guided by specific challenges within the social context (the negative impact of lockdown on young people’s mental health), Lucy’s account also captures the socially embedded nature of her decision-making, thus evidencing a collective dimension to effectuation.

Data also yielded evidence of the role of CoPs during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, participants whose businesses are franchises described the importance of CoP membership to marketing decision-making during lockdown. Typically, the CoPs existed prior to the emergence of COVID-19, yet activity was minimal. However, the CoPs became more active during lockdown and met more frequently, an observation which supports evidence within the wider CoP literature of increased participation as a result of lockdown conditions (Delgado et al., Citation2020; McLaughlan, Citation2021). Sheila describes such a scenario:

Sheila: ‘Because we are all solo operators we might never meet. We have a Facebook group that was previously just used for sharing ideas or asking for advice. But it quickly became far more prevalent. We became far more cohesive. It was like an online staff room. We never would have done that previously.’

In response to lockdown, CoPs focused on sharing information, ideas and experiences of migrating their classes online. Their focus therefore evolved to meet the challenges posed by COVID-19, a finding that mirrors those of studies of CoPs within alternative industry sectors (McLaughlan, Citation2021; McQuirter, Citation2020; Mead et al., Citation2021). CoP members demonstrated a collective effectuation approach to marketing decision-making by collaboratively identifying suitable existing resources and developing ways in which they might be leveraged within multiple businesses (a ‘bird-in-the-hand’ decision-making approach (Sarasvathy, Citation2009)). The following quote from Abby evidences this:

Abby: ‘So a few people did some testers and the whole franchise came together. We discussed ideas of how we could change what we do and still get the fun across. It is great as a sounding board to say: “What about this? Shall we try this? Oh, I thought of this”.’

In addition to decisions around service design and delivery, CoPs supported decisions around customer communications, such as best practice in instructing customers in how to access online classes:

Jane: ‘So, I’d say: ‘I’ve got a mum that’s saying she cannot link in, what are people doing?’ We might be like, right guys, here’s a post for Facebook that tells customers how to put it on their screen better.’

In highlighting collective influences on women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making we extend knowledge of collective entrepreneurial marketing decision and of the role of CoPs in a crisis situation.

Marketing decision-making beyond a crisis

When it became apparent that lockdown conditions might ease, participants’ marketing decision-making became reoriented to longer-term business development goals. Effectuation decision-making and CoP membership both drive learning (Wenger, Citation2010; Jisr & Maamari, Citation2014), and as a result of their marketing decision-making in response to lockdown conditions, participants identified business opportunities for future development. Louise and Ruth described their plans:

Louise: ‘I’ve taken all my classes, and I’ve put those online and now I’m actually training nursery workers in the skills to deliver the classes. Basically, I’ve completely changed the model. I can’t have that uncertainty that we’ll be locked down again. If we are then we’ll know that we’ll have that money coming in.’

Ruth: ‘I think we might continue with offering some online classes. It means we can offer it across the whole country. So, it’s not exclusive now to a small area. It’ll make it a bit more cost effective for small schools to have activities, for sure.’

Both Louise and Ruth are looking to achieving specific goals: Louise is aiming to build a new revenue stream while futureproofing her business against future lockdowns while Ruth is seeking profitable growth through attracting new customers. In developing goals and then determining ways of achieving them, Louise and Ruth demonstrate a return to a causation approach to marketing decision-making (Sarasvathy, Citation2001). We therefore further enrich understanding of entrepreneurial marketing decision-making as we highlight that when uncertainty eases, microbusiness owners adopt a causation approach to marketing decision-making which reflects learnings from effectuation decision-making during the crisis period.

Theoretical implications

This study investigated women microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic, exploring their application of effectuation and causation approaches and any collective influences on their decision-making. In particular, we explore the marketing decision-making of women who own microbusinesses that offer services in the form of group activities to pre-school or school-age children, and which played an important role in supporting young people’s wellbeing during periods of lockdown. Our findings make several contributions to the literature on entrepreneurial marketing decision-making, crisis management and communities of practice. We summarise these contributions and eight resultant propositions in , which we use to structure the following discussion.

Table 4. Women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making in a crisis: contributions to theory.

The first three propositions concern women microbusiness owners’ individual marketing decision-making process in response to a crisis. The literature on entrepreneurial decision-making delineates causation and effectuation approaches (Lam & Harker, Citation2015; Miles et al., Citation2015), yet knowledge of how these approaches are applied to marketing decision-making is fragmented (Bocconcelli et al., Citation2018; Lehman et al., Citation2020), with very few studies of women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making. Moreover, while extensive knowledge of firms’ crisis management exists (Coombs & Laufer, Citation2018), and the entrepreneurial decision-making narrative suggests that effectuation is particularly effective in crisis situations (Sarasvathy, Citation2001), prior research has not shed light on women microbusiness owners’ approach to marketing decision-making in a crisis scenario. We find that, when facing a crisis, women microbusiness owners’ apply the ‘pilot in the plane’ principle of effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009) to their marketing decision-making as their focus alters from the pursuit of long-term business development goals to the management of what can be controlled in the present. Hence our first proposition:

P1:

In response to a crisis, women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making process shifts from causation to effectuation.

Second, we evidence women microbusiness owners’ leveraging of a diversity of existing resources when making marketing decisions in a crisis, some of which were owned by the microbusiness owner (service designs, relationships with employees and customers, communications, subscriptions to online platforms) while others were owned by people to whom the microbusiness owner was connected (customers’ resources, employee skills). This reflects the networked nature of entrepreneurial activity (Morrish & Jones, Citation2020), enriches the narrative around the application in a crisis of the ‘bird in the hand’ principle of effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009), and gives rise to our second proposition:

P2:

In a crisis scenario, women microbusinesses owners leverage a combination of their own resources and those owned by other people within their existing networks in an effectuation marketing decision-making process.

Our third proposition relating to women microbusiness owners’ individual marketing decision-making process in response to a crisis concerns the ‘affordable loss’ principle of effectuation, which asserts that decision-making entails an assessment of what one is willing to lose in the short term over anticipated longer-term returns on investment (Sarasvathy, Citation2009). We observe that when making marketing decisions with a direct impact on revenue (that is, around pricing), women microbusiness owners’ assessments of what they are willing to lose are moderated by decisions around the increased leveraging of resources, which seek to offer greater value to, and thus retain, customers. We therefore highlight the combined application by women microbusiness owners of the ‘affordable loss’ and ‘bird in the hand’ principles of effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009), thereby adding granularity to the discussion around effectuation marketing decision-making. Subsequently, we offer our third proposition:

P3:

Women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making process in a crisis involves the combined assessment of affordable loss of revenue and achievable enhancement in value for customers.

The next two propositions concern collective influences on women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making process in response to a crisis. Collective marketing decision-making by women microbusiness owners is underexplored. However, a growing stream of entrepreneurship research asserts that entrepreneurial decision-making is not necessarily an individual endeavour (Yan & Yan, Citation2016), but is informed by knowledge gleaned from interactions within social networks (Dimov, Citation2007; Drakopoulou Dodd & Anderson, Citation2007). We enrich this body of research as we highlight that, in a crisis scenario, women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making is informed by interactions with customers, and the resultant awareness among microbusiness owners of the challenges faced by customers due to crisis conditions. Where possible, women microbusiness owners make marketing decisions to alleviate these challenges. Thus, our fourth proposition:

P4:

Women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making in a crisis is influenced by their awareness of challenges within the social context in which their business is embedded.

Studies have shown that membership of a community of practice (CoP) is beneficial in a crisis scenario in supporting collective decision-making (e.g. Delgado et al., Citation2020; McLaughlan, Citation2021). However, women microbusiness owners’ involvement in CoPs is underexplored, as are the potential benefits of membership when a crisis occurs. Moreover, studies of collective decision-making in CoPs have not explored whether and how effectuation and causation processes are applied. We contribute to knowledge of CoPs and of collective entrepreneurial marketing decision-making by highlighting the presence of CoPs comprising women microbusiness owners and evidencing collective marketing decision-making by CoP members that adopted an effectuation approach. Hence, our fifth proposition:

P5:

In response to a crisis, communities of practice comprising women microbusiness owners engage in a collective effectuation approach to marketing decision-making.

The final two propositions in concern women microbusiness owners’ individual marketing decision-making in relation to the anticipated post-crisis period. The entrepreneurial decision-making literature contends that an effectuation approach is more effective in crisis situations (Sarasvathy, Citation2001), yet the narrative also acknowledges that both causation and effectuation can occur simultaneously (Galkina & Jack, Citation2022; Reymen et al., Citation2015). We extend this dialogue as we observe that, during a crisis period, when normal conditions seem set to resume, women microbusiness owners begin formulating marketing decisions in support of long-term plans. Moreover, we observe how the outcomes of and subsequent learnings from marketing decisions made in response to crisis conditions inform longer-term marketing decision-making around, for instance, business resilience against the impact of future crises and the development of new opportunities for growth. Consequently, we offer propositions six and seven:

P6:

When crisis conditions look set to ease, women microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making adjusts to incorporate a causation approach.

P7:

An effectuation approach to marketing decision-making by women microbusiness owners during a crisis generates learnings which influence future causation approaches to marketing decision-making.

Managerial implications

Our findings highlight how the adoption of an effectuation approach to marketing decision-making can facilitate continued trading for microbusinesses during difficult periods. To mitigate against the risks of future crises, microbusiness owners, both women and men, should ensure that they are skilled in effectuation decision-making. An understanding of the principles of effectuation decision-making may require formal training by government bodies, universities or members of entrepreneurial networks to highlight the methods and benefits of pivoting from a pre-planned strategic path during a crisis.

To facilitate effective effectuation decision-making during a crisis, microbusiness owners should ensure access to a range of resources. They might, for example, identify third-party sources of customer insight, which would provide information from their social context and inform marketing decision-making. In addition, equipment hire companies, template communiques to customers, employees and suppliers, and key sources of support within peer networks and local agencies represent further resources that microbusinesses can assemble and then draw upon in the event of a crisis. Relatedly, this study has highlighted the invaluable role of digital technology in microbusinesses’ survival during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the acknowledged digital deficit amongst small business owners (OECD, Citation2021), it is imperative that microbusinesses take steps to ensure that they are competent users of digital technologies, and are able to incorporate technology in a manner that is cost-effective and sustainable in the longer-term. Platforms such as Zoom and Facebook Live are not viable long-term solutions for service delivery due to a potential lack of user control, costs and security.

Given the observed benefits of a collective approach to effectuation decision-making, we suggest that crisis plans might be developed in collaboration with other microbusiness owners. Collaborative planning might highlight further resources and sources of support and would ideally pave the way for collective marketing decision-making in the event of a crisis. To facilitate this planning activity, microbusiness owners might form or join entrepreneurial networks and establish a crisis-management dialogue. Additionally, CoPs can play a role in supporting microbusiness owners’ marketing decision-making during a crisis. Therefore, we suggest that microbusiness owners who are not CoP members should seek to join one, even if they maintain a peripheral involvement (as weak ties can nonetheless provide access to ideas and innovation; Granovetter, Citation1973), so they can leverage their membership in times of need.

Our study also highlighted how, when conditions look set to ease, microbusiness owners began to consider the future of their businesses in the post-COVID-19 era. The pandemic has fundamentally changed customer expectations, accelerating the shift to online consumption (Statista, Citation2022) and omnichannel delivery (Accenture, Citation2021). Consequently, microbusinesses need to adapt and to reframe their marketing decision-making activity to deliver a smooth cross platform omnichannel experience (Tyrväinen & Karjaluoto, Citation2019). Future pricing decisions need to account for varying channel-related costs. To deliver a coherent omnichannel experience, marketing decisions require microbusiness owners to understand how to map the customer journey and identify relevant marketing activities at important touchpoints. Ultimately, being aware of customer touchpoints and cognisant of how they interrelate will be essential to building successful long-term customer relationships.

Future research directions

Future research might enrich knowledge of microbusiness owners’ responses to crises by exploring entrepreneurial marketing decision-making within a more diverse sample. In particular, future works might explore entrepreneurial marketing decision-making by providers of more diverse services that target a broader range of customers with varying needs and experiences. Further research might also explore in greater detail any variation in entrepreneurial decision-making by owners of microbusinesses operating different business models, such as franchising and licencing. Moreover, our study sheds light on the marketing decision-making by microbusiness owners who successfully moved their businesses online during the periods of lockdown. Further insight into entrepreneurial marketing decision-making in crisis situations might be gleaned by exploring the marketing decision-making by microbusiness owners who decided not to transfer their businesses online during the COVID-19 lockdowns, or who tried but were unable to do so. Alternatively, microbusiness owners whose customers were unable to access online services due, for example, to digital exclusion, also warrant attention.

In addition, women microbusinesses owners who found themselves unable to balance family and work commitments during lockdown require additional research to understand their entrepreneurial marketing decision-making. Relatedly, we did not seek to compare women and men microbusiness owners, and suggest that future research should explore wider heterogeneities among microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making, in crises and in more normal contexts.

The role of networks and CoPs were central to the success of our participants, however little research has explored how network effects (positive and negative) impact marketing decision-making. The rise of the platform economy and platform business models might prove to be a potential avenue for future research to explore how platforms can enable value creation for producers and customers. Furthermore, the role of platforms in a microbusiness context is even less developed. This research agenda would also allow for a greater exploration of the role and impact of digital technologies as facilitators of network effects.

Some other limitations of our study are evident. First, we studied women microbusiness owners’ entrepreneurial marketing decision-making prior to and during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Future studies should seek to develop detailed descriptions of their marketing decision-making in the post-COVID-19 period. In particular, while we have identified shifts in decision-making orientation between causation and effectuation approaches, we suggest that understanding of entrepreneurial marketing decision-making will be further enhanced by examining how the skills and adaptations accumulated via crisis-induced effectuation approaches inform long-term approaches to marketing decision-making. Second, our study is located in the UK and Republic of Ireland. Future studies might adopt a more global perspective and explore, for instance, cultural influences on entrepreneurial marketing decision-making during a crisis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helen L. Bruce

Helen L. Bruce is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Marketing at Lancaster University Management School. Helen’s research agenda focuses on generating insight that informs business practice in addition to extending theoretical knowledge. Much of her research is undertaken within services contexts, primarily in the business-to-consumer field. Helen has a particular interest in consumer groups, such as families or communities, and their shared perceptions, motivations and identities. Helen has previously published in the Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Services Marketing, Journal of Relationship Marketing, and the International Journal of New Product Development and Innovation Management.

Tara Rooney

Tara Rooney is a Lecturer in Marketing and Digital Marketing Strategy in Technological University Dublin where she has worked since 2004. Tara’s research is focussed on relationship marketing and in particular, digital consumer relationships. Her research applies narrative and storied approaches to exploring how consumer relationships develop, are maintained and dissolve in consumer settings. Tara is also engaged in Case-Based Methodology and is part of the case writing team for the EU-funded European Case Study Alliance Project. Tara has published in a variety of journals and contributed to book publications.

Ewa Krolikowska

Ewa Krolikowska is a Senior Lecturer in Marketing at the University of Greenwich. She has previously worked as a marketing professional and has Chartered Marketer status awarded by the Chartered Institute of Marketing. Ewa’s research interests lie in the management of customer relationships and experiences and business-to-business relationship marketing. Her research has been published in academic journals such as Current Issues in Tourism and the Journal of Relationship Marketing, as well as in consultancy reports, practitioner articles and conference papers.

References

- Abrams, L. S. (2010). Sampling ‘hard to reach’ populations in qualitative research: The case of incarcerated youth. Qualitative Social Work, 9(4), 536–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010367821

- Accenture. (2021). Life reimagined: Mapping the motivations that matter for today’s consumers. https://www.accenture.com/gb-en/insights/strategy/_acnmedia/Thought-Leadership-Assets/PDF-4/Accenture-Life-Reimagined-Full-Report.pdf

- Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 30(5), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00138.x

- Altinay, L., & Arici, H. E. (2021). Transformation of the hospitality services marketing structure: A chaos theory perspective. The Journal of Services Marketing, 36(5), 658–673. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-01-2021-0017

- Anna, A. L., Chandler, G. N., Jansen, E., & Mero, N. P. (2000). Women business owners in traditional and non-traditional industries. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(3), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00012-3

- Atuahene-Gima, K., & Murray, J. Y. (2004). Antecedents and outcomes of marketing strategy comprehensiveness. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.4.33.42732

- Ben-Hafaiedh, C., Champenois, C., Cooney, T. M., & Schjoedt, L. (2022). Entrepreneurship as collective action: The next frontier. International Small Business Journal. https://journals.sagepub.com/pb-assets/cmscontent/ISB/Call%20for%20Papers%20Entrepreneurship%20as%20Collective%20Action-1627624313.pdf

- Bergh, P., Thorgren, S., & Wincent, J. (2011). Entrepreneurs learning together: The importance of building trust for learning and exploiting business opportunities. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0120-9

- Bocconcelli, R., Cioppi, M., Fortezza, F., Francioni, B., Pagano, A., Savelli, E., & Splendiani, S. (2018). SMEs and marketing: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(2), 227–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12128

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Budge, A., Irvine, W., & Smith, R. (2008). Crisis plan? What crisis plan! How microentrepreneurs manage in a crisis. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 6(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2008.019131

- Busenitz, L. W., West, G. P., III, Shepherd, D., Nelson, T., Chandler, G. N., & Zacharakis, A. (2003). Entrepreneurship research in emergence: Past trends and future directions. Journal of Management, 29(3), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00013-8

- Cao, G., Duan, Y., & El Banna, A. (2019). A dynamic capability view of marketing analytics: Evidence from UK firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 76, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.08.002

- Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (Eds.). (2004). Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. Sage.

- Central Statistics Office. (2019). Business in Ireland: Small and medium enterprises. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-bii/businessinireland2019/smallandmediumenterprises/

- Challagalla, G., Murtha, B. R., & Jaworski, B. (2014). Marketing doctrine: A principles-based approach to guiding marketing decision making in firms. Journal of Marketing, 78(4), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.12.0314

- Charoensukmongkol, P. (2022). Does entrepreneurs’ improvisational behavior improve firm performance in time of crisis? Management Research Review, 45(1), 26–46. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-12-2020-0738