Abstract

This study reconsidered educational materials by analyzing educators’ opinions regarding handmade manipulative materials (HMMs) for children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities in Japan. Instead of concurring with the view that educational materials are static and inert products, the author adopted an agential realist perspective and considered them as agencies working and becoming with teachers and children. The author interviewed two retired teachers who had spent more than 30 years in HMM production and analyzed the obtained data using a diffractive methodology. Findings showed that making and remaking HMMs allowed teachers and children to engage with actualizing concepts without language and demonstrated the open-ended nature of learning for teachers and children with HMMs.

Introduction

This study aimed to discuss handmade manipulative materials (HMMs) for children with disabilities in Japan. HMMs have had a long history in Japanese special education. An analysis of opinions about educational practice by highlighting HMMs provides an alternative view of education. This study is founded on the agential realist perspective and adopts its diffractive methodology (Barad, Citation2007; Lenz Taguchi, Citation2012) to analyze statements made about HMMs by two retired teachers who have produced thousands of HMMs throughout their careers for children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD). Since people with PIMD frequently experience social exclusion (Cologon, Citation2020) and their desire to become involved in activities often neglected, this study provides a critique of the assumption that the level of PIMD is directly associated with devaluation and contributes to inferior learning.

Theoretical background

Agential realism was introduced by feminist theorist Karen Barad (Citation2007). Its core idea, based on recent quantum physics, is that research cannot explore data or phenomena from outside it. This pertains not only to the epistemological (way of knowing) but also to the ontological issue (way of being). Referring to Niels Bohr’s philosophy-physics, Barad stated, “We are a part of that nature that we seek to understand” (Barad, Citation2007, p. 184). This suggests that an agential realist turns from a traditional postulation of social practice, in which independent actors interact and cause events, to an alternative one, in which relations precede relata. Barad (Citation2007) argued that the “practice of knowing and being are not isolable; they are mutually implicated (p. 185),” and agential realists analyze “with” data, not “of” data. Such stance of agential realism is called onto-epistemology.

Agential realism is profoundly influenced by posthumanism and new materialism theories (Barad, Citation2007). Modernist humanist theory, which originated from the Enlightenment, stipulates that agency is exclusively reserved for people who can realize their own will or intentionality, and that inorganic objects are only within linear cause–effect deterministic processes (Bennett, Citation2010; Colebrook, Citation2008; Coole & Frost, Citation2010). By placing human subjectivity at the core of research, poststructuralism or postmodernism inherited this kind of dualism (Hekman, Citation2008). In contrast, posthumanists and new materialists are suspicious of humanists’ assumption of agency, insisting that agency is distributed as part of all things both human and nonhuman (Bennett, Citation2010; Braidotti, Citation2013; Coole & Frost, Citation2010; Jackson, Citation2017). This means that not only rational entities but also everyone and everything are not fixed or inert objects and play important roles working with other entities to construct social phenomena.

This study is interested in describing what teaching and learning looks like when educational materials are considered agencies. As Lenz Taguchi argues, the key here is “to start thinking of all aspects of learning—including the material—as being active and having agency in the construction of knowledge” (Lenz Taguchi, Citation2010, p. 50). Scholars have applied posthumanism and new materialism in educational research since the start of the 21st century by considering different agencies, including materials and animals (Taylor & Pacini-Ketchabaw, Citation2015), nature (Hadfield-Hill & Zara, Citation2019), technologies (Smith & Dunkley, 2018), buildings (Mcphie, Citation2018), and play equipment (Günther-Hanssen, Citation2020; Hultman & Lenz Taguchi, Citation2010). The aforementioned studies produced novel educational concepts or knowledge that is different from what scholars have taken for granted in human- or discourse-centered research; however, their main focus is almost always on humans’ becoming, as education is in fact about humans. Thus, to address the insufficient consideration given to the becoming of educational materials, this study uniquely puts these materials at the center of educational research.

Additionally, the significance of this study’s adoption of agential realism lies in its ethical stance. Agential realism dismantles binaries such as human/nonhuman, subject/object, mind/body, and rational/irrational (Barad, Citation2007), which emancipates researchers from the notion that humans develop from the minor to the major side of these binaries. Barad (Citation2007) calls the nonhierarchical stance theory of agential realism as “ethico-onto-epistem-ology” (p. 185). Because an agential realist’s stance provides a flattened plane for thinking, some educational researchers adopt it to eliminate the asymmetrical relationships between children and adults (Günther-Hanssen, Citation2020; Lenz Taguchi, Citation2010; Murris, Citation2016), girls and boys (Lenz Taguchi & Palmer, Citation2013; Günther-Hanssen et al., 2019), and children with and without disabilities (Hickey-Moody, Citation2009; Lenz Taguchi, Citation2012; Reddington & Price, Citation2018). Likewise, this study challenges the traditional stereotypical discourse about educating children with PIMD, who are often placed in the most marginalized position in education and whose learning abilities are devalued or neglected.

An emergent posthumanist approach to disability studies

The present study provides an overview of humanist contributions to disability studies and then considers what posthumanists can add to them. The humanist approach to disability studies emerged in the late 20th century, starting as part of the movement of people with disabilities in the UK that opposed the prevailing disability policies linked to medicalization and individualization (Oliver, Citation2009; Shakespeare, Citation2017). Oliver (Citation2009) argued that disadvantages experienced by people with impairments are due to their exclusion from general society. This social model of disability led the Japanese government to promulgate the Act for Eliminating Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities in 2013 (Cabinet Office & Government of Japan, 2013). Some researchers argue that the original theory of disability studies separates impairment from disability (Goodley, Citation2001; Shakespeare, Citation2017). The qualitative approach focuses on the voices of people with disabilities and moves away from previously dominant beliefs of dependence, weakness, custodialism, infantilization, and social encumbrance.

While qualitative disability studies have prioritized the language, discourse, and culture of people with disabilities and then championed their involvement in politics and community activities, this social constructionist linguistic direction risks ostracizing people who do not use language to communicate. Except for studies on people with mild intellectual disabilities but who can speak (Anderson & Bigby, Citation2016; Goodley & Rapley, Citation2001; McVittie et al., Citation2008), qualitative approaches have often excluded people with intellectual disabilities whose experiences are rarely or never completely spoken as a linguistic form. That is, qualitative studies tend to promote the Western traditional “troubling dualism” as argued by Haraway (Citation1991, p. 177). Braidotti (Citation2013) asserted that this type of dichotomous thinking based on humanism was “modeled upon ideals of white masculinity, normality, youth and health” (p. 68), which ultimately ignored “non-white, non-masculine, non-normal, non-young, non-healthy, disabled, malformed, or enhanced people” (p. 68). In the ontological plane, where humans are divided into speakers and the mute, the latter have always been marginalized.

Posthumanist disability researchers think differently. Roets and Braidotti (Citation2012) problematized the humanist dualism that promotes categorization and hierarchical stratification, finding that adopting a posthumanist monist mindset could nullify the dichotomy between language and materials and overcome the limitations of social constructivism. The posthumanist outlook is that all humans are “interlined and continually intra-acting with wider material as well as social, economic, psychological, and cultural forces” (Alaimo, Citation2008, p. 250). From this perspective, Nayer (Citation2014) criticizes the stereotypical view wherein people distinguish disabled bodies with prostheses and able bodies with devices and tools. He suggests that posthuman bodies are always a hybrid of “bodies + machines where the body evolves in conjunction with assorted tools (p. 107).” Therefore, disabilities do not pre-exist but emerge after people, who are all hybrids of others, being separated from the actual system or network to live. The ethics of posthumanism blur the boundaries among humans that humanists have presupposed.

No studies have identified the hybrid aspect of children with PIMD, teachers, and teaching materials in education. As their impairment is regarded as a characteristic or property of individuals, people with PIMD are usually characterized as those with significantly low IQ scores (around or below 35) and little or no apparent verbal acuity, who seem to be patients needing constant support in their daily living activities. Nakken and Vlaskamp (Citation2007) found that PIMD has two key characteristics: profound intellectual disability and profound motor disability. From the perspective where language seems an advanced cultural tool, PIMD seems to be defined as the poor quality of humans. Hence, this study dispels the idea of deriving inferiority from this characterization by focusing on the hybrid aspects of teaching and learning involving children with PIMD from an agential realist ethico-onto-epistemological stance.

Japanese special education for PIMD and HMMs

In Japan, most children with PIMD attend special education schools that are separated from mainstream schools. Unlike the curriculum for children without disabilities, the PIMD curriculum focuses more on noncognition and self-determination. Education via the use of HMMs has been one of the main strategies in this approach. In Japan, special schools have woodworking rooms equipped with machinery and carpentry tools for vocational and life skills training of children with mild disabilities. Some teachers use these rooms to create their teaching materials. HMMs are teaching materials that fit in a desk and are operated using hands or body parts. Although HMMs, which have been around for half a century in Japan, are similar to manipulative teaching tools that are part of the Montessori curriculum, their beginnings were entirely different. Despite the lack of a clear HMM originator, Hachizo Umezu (1906–1991) and Akiyoshi Nakajima (1927–2000)—whose research focused on deaf–blind children’s cognitive and functional development—are often acknowledged as pioneers of HMMs, as they were the first to introduce the practice in Japan. Fukashi Mizuguchi (1929–2007), a teacher who worked in the early stages of Japanese PIMD education, learned from Umezu and Nakajima and introduced the HMMs concept to many other teachers. After retiring, Mizuguchi established a teachers’ community called Shogaiji-Kiso-Kyoiku-Kenkyu-Kai (Kiso Ken: Kiso means “fundamental” and Ken means “workshop group”) in 1989. The Kiso Ken’s community is composed of teachers who are passionate about creating or discussing on HMMs.

Kiso Ken is a teacher-run community that holds a monthly workshop meeting, one of hundreds conducted in Japan, each of which focusing on specific educational subjects and topics. Kiso Ken focuses on participants’ creation and mutual introduction of handmade teaching materials, information sharing, and discussions of educational practices using such resources. The group has no specific doctrines except their interest in providing valuable education using HMMs. To my knowledge, Japan has only one other teacher-run group focusing on handmade teaching materials for children with severe disabilities: Chofuku Ken (Chofuku means “multiple”). While Chofuku Ken works on HMMs for children who spend most of their day in bed or in a wheelchair, Kiso Ken focuses on HMMs for children who manipulate these materials with their fingers or hands. Kiso Ken’s main participants are teachers working in schools for children with intellectual disabilities, but it is also joined by educators who concentrate on other types of disabilities, mainstream schoolteachers interested in special-needs education, researchers, and university students in their training courses. The monthly meetings feature each teacher introducing their HMMs and their practice in videos, followed by a discussion about the HMMs. Kiso Ken is like a network, where members are allowed to casually enter and leave; hence, sometimes it would have fewer than 10 participants, but other times there can be more than 30.

HMMs are called Kyo-zai Kyo-gu in Japanese. The literal translation of Kyo-zai is “teaching materials” and Kyo-gu “teaching tools.” Despite the ambiguous boundary between Kyo-zai and Kyo-gu, this study emphasizes the material aspect of HMMs. When things are regarded as tools, they are used to achieve specific goals. Meanwhile, new materialists, considering the vibrant nature of things, view them as agencies (Bennett, Citation2010; Coole & Frost, Citation2010). Like Montessori manipulative materials, Japanese HMMs have various characteristics, such as weight, roughness, color, shape, and volume, which encourage children’s learning across a wide range of topics including classification, categorization, numeration, lettering, and operation. The new materialist view provides new ways of thinking where these various features of HMMs affect humans. Instead of treating things as passive, static, and inertial artifacts that are merely tools that are made outside by someone else to support children’s learning, the starting point of thinking of HMMs as material agencies is by viewing them as more than just products used to achieve educational goals.

Materials and method for analyzing data from agential realist perspective

Moving from the stereotypical discourse with diffractive methodology

This study analyzes interview data from two teachers by adopting a diffractive approach, which is a methodology under agential realist research (Barad, Citation2007; Lenz Taguchi, Citation2012).

Jackson and Mazzei (Citation2012) stated that interview data can be considered partial and incomplete, as they can potentially change later. This is true for the current study not because the interviews were insufficient but because voices themselves are generally innately so (Mazzei, Citation2013); that is, from a posthumanist perspective, individual utterances are assemblages arising from a “collective, social and impersonal, pre-existing ‘us’” (MacLure, Citation2013, p. 660). Different from reflexivity or reflection as a common metaphor for analytical thinking, diffraction refers to a physical phenomenon featuring the interference and blend of multiple waves, leaving some remnants of the original wave (Barad, Citation2007; Hultman & Lenz Taguchi, Citation2010). Diffractive methodology neither interprets meanings in interview data nor reveals the pre-existing reality underlying them; rather, it produces something new and innovative by thinking with data (De Freitas, Citation2017; Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2012; Lather & St. Pierre, Citation2013; Mazzei, Citation2013). This study applied this methodology to overcome the educational marginalization of people with PIMD. Despite the significant potential of learning for children with PIMD with HMMs and their teachers’ awareness of these materials, representing or interpreting data from social constructivists’ reflective methodology direct our focus to the dogmatic belief that autonomous, rational, and well-intentioned individuals are superior (MacLure, Citation2013), which therefore devalues children with PIMD. Instead, diffractive methodology features the capability to affirmatively illuminate vital materialities by advocating freedom from stereotypical discourse.

Procedures

The two interviewees—Ota, 65, and Hara, 71 (both pseudonyms)—were senior Kiso Ken members who spent more than 30 years working in Tokyo schools with students with disabilities and had already retired from full-time work. Both continue to work in special education as external leaders who advise teachers on creating and using HMMs.

In a Kiso Ken meeting in May 2020, Hara delivered a presentation of his “mazes” HMM, which has been used for a long time in Japanese education for students with PIMD. By manipulating a small marker in a wooden maze, moving it from start to goal, children stimulate their thinking with a feeling of enjoyment while operating it. These mazes encourage children’s fine vertical and horizontal movements of their fingers and hands, following the target and maintaining their concentration with their eyes, predicting, monitoring, and modifying their own actions and their outcomes. Hara introduced his novel mazes, which involved moving a small metal ball using a stick with a magnet attached to it instead of moving a marker directly with one’s finger, aiming to connect children’s manipulation of the stick to their future lettering with a pen. Ota participated in the meeting, having been inspired by the aforementioned mazes. Before the subsequent meeting, he revised his mazes with a flat washer and stick, with magnets attached to both of them, and introduced these in the June meeting. As a participant in the May and June meetings, the author was curious about how HMMs enable the learning of children with PIMD and the teaching approach of educators. After the meetings, the author submitted the research plan to the Rikkyo University Ethics Review Board and obtained ethical approval in July. Both interviewees then provided informed consent.

The researcher conducted three online interviews with each teacher, each session lasting two hours, from August to October 2020. The first interview focused on their backgrounds as teachers and Kiso Ken members, their beliefs regarding the value of HMMs, and other relevant information. In the second and third interviews, the teachers demonstrated some of their HMMs, showed pictures and videos of their implementation with children, explained the thinking behind these materials, and discussed their educational value. Since the interviews were unstructured, the teachers were free to talk about the children for whom they had developed the HMMs, how they made and remade the HMMs, what they were thinking about while making and practicing with these materials, who and what inspired them as they were creating these resources, and so on.

After the interviews, the researcher read the collected data diffractively (Günther‑Hanssen, 2020; Lenz Taguchi, Citation2012; Lenz Taguchi & Palmer, Citation2013). The first wave of diffraction in this study was the assemblage of the two voices in the interview data, while the second wave included the researcher’s interference with the data. First, while reading and rereading the interview data, the researcher highlighted relevant parts of the statement, such as the development, change, revision, and remaking of HMMs in Word files, as what matters is the becoming of materials. Next, the researcher read the parts using an agential realist perspective, allowing for the consideration of nonhuman agency and focusing on the aforementioned becoming of education materials. That is, the researcher emphasized parts that suggest material agency and turned those that treat materials like tools into those where materials are at the core. Then, the researcher identified three notable aspects—HMM development, educational practice using HMMs, and learning with HMMs—and changed them into the following by focusing on their material aspects: the nature of HMMs as assemblages, teaching and learning with HMMs, and the endless becoming of HMMs–children–teachers, respectively. Moving beyond traditional educational theories that only consider materials as mere learning aids, this analysis attempts to think differently.

Reading data with materials as the focus

The nature of HMMs as assemblages

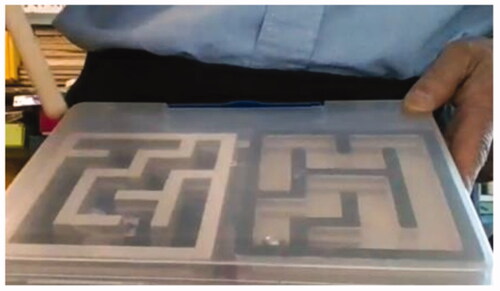

Impressed by the introduction of the mazes at the Kiso Ken meetings in May and June, the researcher asked the two teachers how they developed their materials and what they were specifically thinking about in the process. shows Hara’s new maze, the goal of which he reformulated by attaching a magnet, changing the point marker from a Konoe Double (produced by a Japanese industrial company that originally intended to use it to display land boundaries by burying it in the ground) to a pachinko ball (which is made of steel and used in Japanese gambling machines) and using a wooden stick to attach the magnet to the tip as a pen to move the marker.

Within the remaking process of mazes, Hara determined the best width for the passages in his mazes by restructuring them repeatedly to ensure that good sounds are produced when the pachinko ball is attached to the magnet at the maze goal, as these attracted the children’s interest. In Excerpt 1, Hara explains how he found the width for the best sound by arranging the materials: a metal ball, magnets, wooden walls, and a plastic box.

Excerpt 1: At first, I did not want to widen the path so as not to cause the pachinko ball to roll from side to side. The path was supposed to be 13 mm wide, but the vibration sound at the goal was not considerable because the wall was too narrow. Therefore, 15 mm was found to be just right in design terms. The space between the ball and the side walls is needed for the ball to shake. Before arriving at this conclusion, I experimented repeatedly. I covered the mazes with a plastic box, which resulted in an inevitable decrease in the loudness of the sound vibration. Therefore, to ensure the requisite volume, I concluded that 15 mm was the best option. Although it seems trivial, whether or not children feel good at the end of their work definitely affects their learning. Apart from the learning objective, the fascination of the matters themselves allures them, I think. This fascination does not only concern the HMMs but everything involved in other educational practices as well. To make the materials fascinating, I have to proceed no matter how many times I fail. It is not only for the children but also for myself. (Hara)

Excerpt 1 is a reminder that sounds are vibrations arising from relations among matter, not among specific organs. Sound quality and volume are neither determined solely by Hara’s preference nor each maze component. Here, sound is produced from/in/as assemblages of Hara’s maze, which cannot be divided into parts. Neither Hara’s agency, path width, nor the pachinko ball governs others; the mutual influence of the three, in a place no distinct components precede, is described by the term intra-action, which is a neologism Barad (Citation2007) introduced in contrast to the well-known concept of interaction.

As shown in , Hara’s HMMs are assemblages not only in the conceptual sense but also because they are literally assembled objects in which material agencies temporarily connect and depart (Kelly, Citation2008). The pachinko balls, whose original purpose is to roll loudly inside a Japanese gambling machine from top to bottom, move in an orderly fashion from the start point of the maze to the goal. They are shiny balls that occasionally swerve and make vibrating sounds when they attach to the magnet at the goal. Wooden boards form the bases, walls, and frames of the mazes, which have contrasting colors to delineate boundaries. Sometimes bright brown would appear in front while black recedes; at other times, their order would be reversed. The children use a stick to operate pachinko ball, engrossed by the loudness of its vibration and the colors of the maze. The magnets at the tips of the wooden sticks attract the steel pachinko balls, allowing the children to manipulate the balls through plastic boxes, which do not allow the wooden sticks or steel balls to pass through but selectively allow a magnetic force. Since the magnets at the tip of the wooden sticks have a weaker magnetic force than the one buried at the goal point, when the pachinko balls reach the goal, they separate from the sticks and are strongly attracted to the goal magnet, making a comforting vibration sound. This way, the mazes consist of various matters in which materialities intra-act.

The assemblages of Hara’s mazes are not completed by themselves. In Ota’s previous mazes, the children would use their finger to move a point marker. However, after the May session, Ota adopted Hara’s ideas and rebuilt his mazes using magnets and wooden sticks, shown in . Excerpt 2 illustrates how one HMM influences others.

Excerpt 2: I saw that Hara used magnets, and I thought the children would be delighted with that. Then, I thought if I used acrylic plates, the children in charge would work more earnestly, and I soon made it. After all, moving the Konoe Double with an object like a pen was found to be completely different from moving it with their fingertips. It is different in the way a car compares to a bicycle. I was seeking material that opened up the children to new experiences, so Hara’s mazes were a great inspiration. (Ota)

According to this passage, mazes as assemblages develop through connections with others. However, the mutual development of these mazes does not aim for an integrated form, as Ota did not use pachinko balls or a plastic box (Excerpt 2). Commenting on each other’s HMMs, they explained how they changed and did not change their mazes after being inspired by the other (excerpts 3 and 4).

Excerpt 3: I wanted children to move their fingers well. For this, it did not need to be pachinko balls. If I used pachinko balls, I would have to make the wooden walls taller. So, I thought I would better not use the pachinko balls in my HMMs. Additionally, if the pen detaches from the mazes, the pachinko ball will roll out of the way, leading the children to work harder. Conversely, the Konoe Double can stay in place, so, I did not add those. (Ota)

Excerpt 4: Ota made the cover by himself using an acrylic plate. But in my case, I emphasized that the mazes are easy for children to operate, so I put my mazes into plastic boxes. Though the mazes became a little obscured, this does not seem so problematic. So, I chose plastic boxes whose thickness was 24 mm. At first, the ball was not attracted to the pen because they were apart. I had to press the top of the case to attract the ball. Only when I pressed about 2 mm, was the ball then attracted. As a result, I raised the height of the mazes by attaching an extra wood base. After that, when I simply closed the pen, the ball was attracted. This is very important. If the ball were attracted only when the children pressed the top of the plate strongly by the pen, the children could lose their way. We have to explain without language. (Hara)

The interviewees’ statements, which both refer to each other, show that the development of their mazes is in a differencing and spreading course. Because the two mazes are influenced by each teacher’s preferences and their specific children’s characteristics, the direction at which they develop diverges. Moreover, as the mazes are developed not only by repairing but also producing from scratch, the previous versions of their mazes are preserved and can be used in different situations. Because the old ones are not replaced with new ones, the iterations of creating mazes are broadened.

Consequently, HMMs are ontic and epistemic assemblages. Their assemblages consist of various materialities whose bodies are connected to teachers, children, and other HMMs, differentiating, spreading, and emitting specific sounds, lights, allure, and others.

Teaching and learning with HMMs

How are HMMs linked to teaching and learning? In Excerpt 4, Hara stated that teachers work with HMMs to teach children who do not speak language. This suggests that HMMs can work with humans without language. Regarding the role of HMMs, Hara explained (Excerpt 5) as follows:

Excerpt 5: We cannot teach by using language to those whose language is not enough. While including some concrete operations, you insert concepts into it. Then, you make them aware of the various kinds of concepts that the materials possess. All we can do is study the deeper senses beyond language, such as the concepts of differences and sameness. For example, teachers usually explain discrimination or classification as simply dividing things, gathering the same things, or identifying the exceptions. They are just paraphrase; this does not tell what actually the concepts are. When you cannot teach concepts with language, the concrete operation precedes the verbal explanation, and sometimes the explanations are attached later. (Hara)

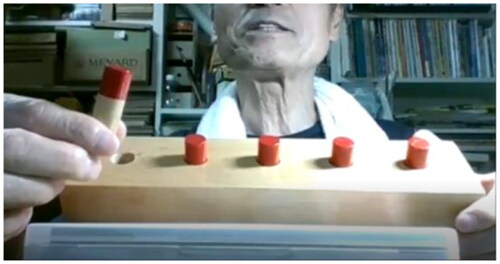

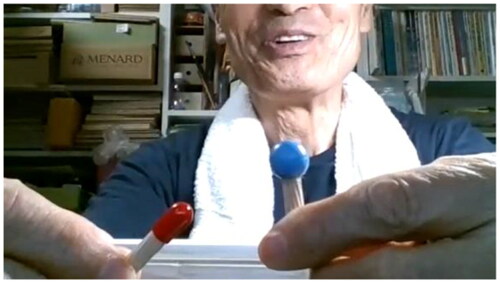

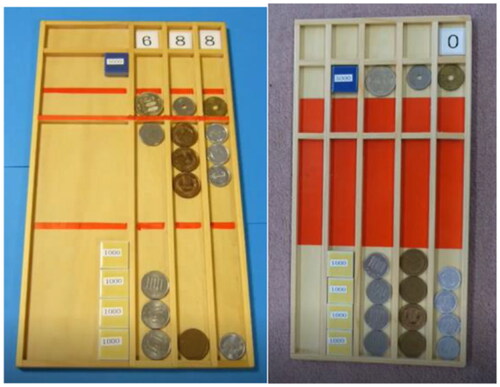

HMMs for children with PIMD validate the contention that materials affect humans without someone always having to imbue them with meaning (Bennett, Citation2010). Hara argued that children with PIMD need HMMs to learn because HMMs make them aware of concepts without the use of language. In Excerpt 6, Ota discusses his “abacus” to describe how HMMs can arise concepts without language. Ota reconstructed his previous abacus, which had red lines (, left), into one that had red areas (, right).

Figure 3. Ota’s abacus (the one on the left is the former version, and the one on the right is the latter version).

Excerpt 6: (What is this red line?) Good question. The line suggests that this area is special. I tried to articulate the different worlds using this line. However, if the child focuses on this area, the line vanishes. (What?) If you focus on areas, the lines are out of sight. (I see.) Nevertheless, if you paint this area, the borderline remains. If people can pay attention to all the parts at the same time, they can understand the differences. In contrast, those who pay attention only to the areas cannot see the line, and in this case, they cannot understand the difference between the two areas (Certainly.) After I painted the area, no explanation was needed. The materials tell people what they should do next. I think that the materials call for the desire of people to divide things. (Ota)

He did not design the HMM abacuses as tools for calculations. Rather, children with PIMD working with the abacus could learn various concepts associated with money, numbers, operations, and shopping. When a child worked with the first abacus by sliding the coins, they did not understand what they were doing, as they did not perceive any differences between the two areas. Ota explained that when the child focused on these areas, the red line vanished, which meant that these lines did not function as articulations separating the phases in the two areas. Therefore, to actualize the concept, Ota remade his abacus by painting one area red, which was to fold and arrange the materialities. As to why this action increased the child’s awareness of the differences without language, Ota explained that children have a desire to divide, which they can actualize when presented with divisible materials.

Diffractive reading encourages researchers not to explore the meaning of the speaker’s words but rather to focus on the new wave emerging within as the researchers become involved in the data. Ota’s use of the word “desire” is linked to the author’s image of “desiring machines” mentioned in Deleuze and Guattari (1972/Citation1983, p. 216). Activating practice without language revealed that the concept of division emerged from within the practice and not from a language instruction from teacher to child. The concept of desire explains why it is possible to teach and learn without language. When Jackson and Mazzei (Citation2012) described desiring machines, they claimed that “there is no ‘subject’ that lies behind the production of desire, and that this ‘desire’ is due not to the lack nor a desire for an object, but rather to production of intensities produced in order to actualize potentials to an ever-increasing degree” (p. 89). Simply put, the children’s mindset with respect to dividing using the HMMs is not a goal-oriented action of the children or the teacher but rather an actualization of a concept in the process of becoming assemblages of the abacus, which includes materials and humans. Therefore, the concept is neither a priori nor conveyed by the teacher to the students; instead, it refers to the process and the product of intra-actions of multiple agencies that contingently emerge from within the HMMs.

The endless becoming of HMMs–children–teachers

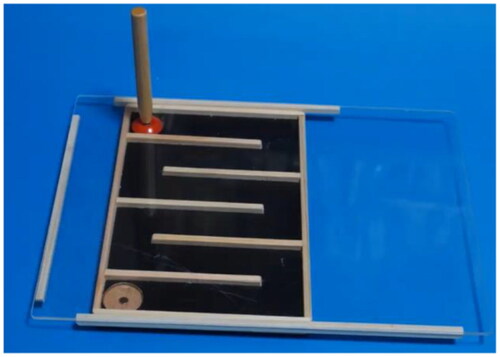

In one of the interviews, Hara showed various “put-stick-ins” that he previously made, with the series of put-stick-ins exemplifying the process of becoming assemblages of materials. Hara’s opinion in Excerpt 7 suggests how HMMs differentiate and disseminate variations.

Excerpt 7: At first, the children begin to pay attention or move their hands to the specific points by touching and operating the sticks. Next, they come to know that their motions have directions and sequences. Additionally, they learn the size, shape, and other qualities…. I often start from the thick sticks because they are easy to hold (). Gradually, I increase the variations. Mizuguchi sometimes colorizes the face, but I think it is not bright or beautiful. So, I put caps, instead… red, blue, and so on. There are many cap shapes ()…. I also made a thicker put-stick-ins made of dowels ()…. I made cylindrical put-stick-ins like this. If you want them to pay more attention to their work, you can use vinyl sticks ()…. Next, these are the rivets. These bottoms are rounded. Because it is shiny, beautiful, and weighty, it attracts the eyes of the children. I used to use batteries, but I found that the rivets were easier to grasp…. When I use steel sticks, I often embed the magnet at the bottom of the holes of the base wood. If they put the stick close to the hole, it is attracted and they can feel the pull (). When you make the semicircle sticks (), the direction matters…. When they understand the movement, I use put-stick-ins with large, middle, and small sticks and holes (). (Hara)

HMMs change according to children’s differences, teachers’ preferences, instructional situations, and other conditions. Through the process of becoming others, HMMs connect with and disconnect from manifold materialities, such as wood, metal, magnet, vinyl, and plastic, and form multimodalities, such as color, weight, length, size, texture, attraction, and direction. These kinds of movements deviate from a law, intrinsic purpose or predictable causal mechanisms (Connolly, Citation2010); rather, HMMs change open-endedly and spread into millions of materials (as shown in , which presents Mizuguchi’s HMM assemblages).

A diffractive reading of data from the two retired teachers also leads to a new mindset regarding teacher development. Creating teaching materials is associated with a Japanese educational principle called lesson study (Fujii, Citation2015; Stigler & Hiebert, Citation1999), in which teachers collaboratively design, check, and reflect on their everyday educational practices to improve the quality of their lessons as learning communities. However, the reality is that not many teachers create HMMs, as they must do this voluntarily after the children they are in charge of go home or during their off-days. Nevertheless, some teachers represented by Kiso Ken members eagerly produce teaching materials. Hara describes what motivates some teachers to create and work with HMMs (Excerpt 8):

Excerpt 8: The success of materials is not proportional to my effort but depends on how the children work. The HMMs are praised only when the children enthusiastically and actively work with them. All I have learned as a teacher is honesty. Mizuguchi taught me that “we never give up no matter how we do not go well because we believe in our children’s future. Unless we believe it, our processes will never continue.” Unfortunately, many people attribute the fault to the children, their parents, or their disability. Primarily, all we can do is to accept what they are positively. Unless we see the child positively, we cannot provide effective support for the child. I was taught this by Mizuguchi. (Hara)

Hara feels apologetic when his HMMs do not work well with the children, but his belief in their future encourages him to continue to reconstruct his HMMs. He emphasized the importance of positively acknowledging the children’s current state. Negative evaluations of children with PIMD by comparing with children without disabilities simply emerged from claims regarding the need for special programs, protection, or remedial education. However, accepting the children’s positive state allows the becoming of HMMs, which promotes the becoming of the children.

The question then pertains to what the becoming of children would look like with materials. Lessons with HMMs are different from skills training conducted using behaviorist beliefs and are separate from cognitive science psychotherapeutic approaches. In these two process–product approaches, adults set goals and implement the project to achieve these goals. While teachers with HMMs certainly do not neglect teaching goals, such objectives never determine the entire teaching process and learning practices. In Excerpt 9, Ota claims that they are aware of the risk of the goal-setting situation:

Excerpt 9: When I show my HMMs to other teachers, some comment that “it’s good to develop the skill to use hands.” However, when I started from this point, I always failed. Instead, I often start by wondering if children work actively or if they enjoy my materials. When I was a newcomer, I certainly aimed to develop the children’s specific powers. But now, I pursue materials with which the children can work actively. My thinking has gradually changed. When I was young, I thought the main focus of education was that the children learned to do something. However, I came to rethink that this was not the primary goal. I think that, sometimes, children happen to learn to do something; that is all. In my case, if I set an educational goal to develop skills, I lose sight of children. I will misunderstand what children are being and doing. Certainly, as a teacher, I want children to be able to do something. I never refuse it. But I think it is something thrown in. It is not the primary goal, but a bonus…. I think it is better that children move HMMs in different ways from the ones I had previously expected. (Ota)

The presupposition of children’s development can obscure a teacher’s focus and can ironically make the actual learning process invisible. Ota argues, instead that whether or not the lessons go well is based on whether the children are proactively working with HMMs. Children do not simply toy with the materials; as the materials are becoming with the children, teachers can observe that the children also change as a by-product, suggesting that HMMs are not representations of concepts but rather planes on which some of these concepts can emerge. Indeed, teachers arrange the materials and integrate multimodalities into their HMMs aiming to convey certain concepts to the children without the use of language. However, the concepts cannot be actualized until the children work with them—that is, arranging and rearranging HMMs produces knowledge temporarily and contingently—thus, concepts created in educational practices are never predetermined.

After all, educational practices with HMMs are characterized by a continuous process of creation. Hara felt the becoming through his encounters with the children even after he retired (Excerpt 10).

Excerpt 10: I am now a veteran, but I sincerely admit that there are many children with which I never win. When I visit schools for students with physical disabilities, I am usually knocked out. To be honest, when I meet them, I do not know how I should teach. And I always feel apologetic. I also hope that they would allow me to try some HMMs even in a short time. I cannot do more than that. I am so frustrated when I lose, so I definitely want to win next time for sure. Even at my age, it is very good for me to be able to have such experiences. It is a precious learning opportunity for me to encounter people whom I am unable to conquer through HMMs. I appreciate it very much. (Hara)

Hara rhetorically viewed his lessons as “battles” with the children and stated that he has not been able to defeat some of them no matter how extensive his teaching experience was. He does not accept limitations for himself, the children, or his materials. Instead, when he feels defeated, he always remakes his materials repeatedly with the aim of winning the next fight. Many materials can be incorporated into HMMs when the teachers remake them, including various wooden, metal, scientific, magnetic, fabric, organic, and other knick-knacks from manufacturing, building, gambling, chemical, technological, and other industries, with new paraphernalia emerging every day, all of which have the potential to become assemblages. The HMMs–children–teachers are becoming over their lifetime with materials they have encountered and will encounter in the future.

Discussion

The diffractive analysis of educators’ opinions highlighted the agentive and creative value of learning for children with PIMD; that is, if they are not engaged in the practices, HMMs and teachers can never develop. Here, educational practice is described neither as information nor an exploration of knowledge because it does not pre-exist. Agential realist onto-epistemology illustrates teaching and learning with HMMs. Barad (Citation2007) emphasized the constant entanglement between the knower and knowledge in the world, saying, “Meaning is not a property of individual words or groups of words but an ongoing performance of the world in its differential dance of intelligibility and unintelligibility” (p. 149). In the same way, knowledge, which is not pre-existent, emerges from the specific intra-action among teachers, children, and HMMs in/as assemblages. Even if teachers working with HMMs speak to children with PIMD, their voices do not convey meanings. Indeed, teachers seem to verbalize their communication: not unusually, teachers would say, for example, “Please put sticks in the holes in order from the left,” while exhibiting the put-stick-ins although the children could not literally make sense of these words. However, here, as Colebrook (Citation2008) claimed, language is “no longer the expression of [a] preceding subject nor the indication of a fulfilling sense” (p. 75); rather, the language with which the teachers converse is one of the materialities (Colebrook, Citation2008), which involve sound, vibrations, and other modalities that entangle with the materialities presented in the HMMs. According to Mazzei’s neologism of voice without organs (Mazzei, Citation2013), inspired by Deleuze and Guattari’s (1972/1983) body without organs, voice is emitted through the posthumanist body that exists in a complex network of human–nonhuman forces. Based on this reasoning, teachers’ voices are not wasted even if they do not convey meaning; instead, they work with HMMs and children as more than meaning.

When materials in educational practices are considered as more than language—because language is just one material (Colebrook, Citation2008)—education with HMMs may generate more by-products than those produced with only language. Lenz Taguchi (Citation2011) criticized modernist education as being excessively human-centric or logocentric. The present findings also revealed that logocentric education renders learning without language invisible; as Murris (Citation2016) critiqued in a reference to Berkeley (Citation1977), “[W]e have first raised a dust and then complain we cannot see” (p. 51). Instead, if researchers are freed from the restrictions of dualism and conduct research considering materialities in education, they develop an awareness of the intra-action of materials–children–teachers, becoming others. The agential realist perspective has the power to change what is taken for granted in education. In the educational practice with HMMs, the teacher’s role is not to convey knowledge but to fold the HMM multimodalities and arrange them to satisfy an impersonal desire to create a conceptual emergence. However, HMMs are not representations of these concepts but are materials that enable their actualization; therefore, teachers must contemplate how to portray concepts such as lining up, operating numbers, and dividing things without language.

Ironically, the theorization of HMMs in a linguistic form risks losing the essential ambiguities and complexities associated with tacit theory and practice. HMM culture in Japan has been inherited among teachers’ communities and communication rather than academies. The exchange of ideas regarding HMM practices in schools or monthly meetings of Kiso Ken has differentiated and spawned millions of HMM variations as well as educational practices with them. From the teacher-centric view, Japanese lesson study has been regarded as a collaborative reflective practice (Fujii, Citation2016; Takahashi, Citation2014). Because reflection is considered a pivotal property of professionals (Schön, Citation1991), it is believed that joint reflection in the teacher community, by showing and observing lessons and talking about them, promotes the professional development of teachers. However, when emphasis is placed on the becoming of materials, teachers’ professional development seems to be a diffractive process because its course is neither driven only by individual teachers’ subjectivity nor their discourse. The Kiso Ken participants not only reflect using language but also affect and are affected by the manifold discourses and materials. Hence, it is important for teachers working with HMMs to record videos and share their experience with one another, as this enhances teachers’ awareness of the complexities of becoming.

Realizing education via HMMs may not be appealing to educators who believe that cultural application is the mission. However, the alternative lens appreciates production rather than reproduction. When compared to education that is driven by educational goals, HMM education provides diverging directions from which millions of new materials can emerge. In HMM education, one finds the “situatedness and path dependence of knowledge production” that Pickering (Citation1995, p. 209) discovered through his analysis of the practice of well-known scholars. He suggests that the vectors of the practice of knowledge production temporarily veer, so the goals are potentially open-ended when humans and material agencies contingently interplay. Materials, children, and teachers, each of which include multiple materialities and multimodalities, shape each other in terms of their machinic assemblages, which one can observe as more like rhizomatic connections than linear transformations (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980/1987)—that is, children and teachers also become others with HMMs. Goal-centric education ignores the opportunities that could be seized if children agentively engage in materials–children–teachers intra-action. The diffractive reading of the opinions of the two retired teachers suggests that the goals of education with HMMs never govern the entire teaching and learning process.

Logocentric education tends to view children with PIMD in a negative light; furthermore, more people may be suffering from the disadvantages inherent in conservative education based on goal-oriented linear education. When teachers use more than language, they can help children by assembling materials in their teaching to actualize concepts, which can then help them become others and again different others with HMMs. Therefore, for teachers, becoming others can continue endlessly even after they retire.

Although the HMMs in the current article target education for children with PIMD, all children have the opportunity to take advantage of educational practice with more than language. Placing emphasis on education as the becoming of materials–children–teachers can lead to the emergence of several novel concepts that have not been seen before.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Y.K.], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yusuke Kusumi

Yusuke Kusumi, a postdoctoral researcher in Japan, was awarded a scholarship of Research Fellowships for Young Scientists from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. He earned his Ph.D in Education from the University of Tokyo, Japan. For the past 10 years, he has conducted field research on special educational schools in Japan and analyzed classroom discourse from a sociocultural perspective. Recently, he is interested in posthumanism and new materialism.

References

- Alaimo, S. (2008). Trans-corporeal feminisms and the ethical space of nature. In S. Alaimo & S. Hekman (Eds.), Material feminisms (pp. 237–264). Indiana University Press.

- Anderson, S., & Bigby, C. (2016). Empowering people with intellectual disabilities to challenge stigma. In K. Scior & S. Werner (Eds.), Intellectual disability and stigma: Stepping out from the margins (pp. 165–177). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Bennett, J. (2010). A vitalist stopover on the way to a new materialism. In D. Coole & S. Frost (Eds.), New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics (pp. 47–69). Duke University Press.

- Berkeley, G. (1977). The principles of human knowledge: With other writings. Fontana.

- Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Polity Press.

- Cabinet Office & Government of Japan. (2013, April 27). Act for eliminating discrimination against persons with disabilities. https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/3052

- Colebrook, C. (2008). On not becoming man: The materialist politics of unactualized potential. In S. Alaimo & S. Hekman (Eds.), Material feminisms (pp. 52–84). Indiana University Press.

- Cologon, K. (2020). Is inclusive education really for everyone? Family stories of children and young people labelled with “severe and multiple” or “profound” “disabilities. Research Papers in Education, 1–23.

- Connolly, W. E. (2010). Materialities of experience. In D. Coole & S. Frost (Eds.), New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics (pp. 178–200). Duke University Press.

- Coole, D., & Frost, S. (2010). Introducing the new materialisms. In D. Coole & S. Frost (Eds.), New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics (pp. 1–43). Duke University Press.

- De Freitas, E. (2017). Karen Barad’s quantum ontology and posthuman ethics: Rethinking the concept of relationality. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(9), 741–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417725359

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press. (original work published 1972)

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press. (original work published 1980).

- Fujii, T. (2015). The critical role of task design in lesson study. In A. Watson & M. Ohtani (Eds.), Task design in mathematics education: An ICMI study (pp. 273–286). Springer.

- Fujii, T. (2016). Designing and adapting tasks in lesson planning: A critical process of Lesson Study. ZDM, 48(4), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-016-0770-3

- Goodley, D. (2001). ‘Learning difficulties,’ the social model of disability and impairment: Challenging epistemologies. Disability & Society, 16(2), 207–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590120035816

- Goodley, D., & Rapley, M. (2001). How do you understand “learning disabilities”? Towards a social theory of impairment. Mental Retardation, 39(3), 229–232. https://doi.org/10.1352/0047-6765(2001)039<0229:HDYULD>2.0.CO;2

- Günther-Hanssen, A. (2020). A swing and a child: How scientific phenomena can come to matter for preschool children’s emergent science identities. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 15(4), 885–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-020-09980-w

- Günther-Hanssen, A., Danielsson, A. T., & Andersson, K. (2020). How does gendering matter in preschool science. Gender and Education, 32(5), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2019.1632809

- Hadfield-Hill, S., & Zara, C. (2019). Complicating childhood-nature relations: Negotiated, spiritual and destructive encounters. Geoforum, 98, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.036

- Haraway, D. (1991). Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. Routledge.

- Hekman, S. (2008). Constructing the ballast: An ontology for feminism. In S. Alaimo & S. Hekman (Eds.), Material feminisms (pp. 85–119). Indiana University Press.

- Hickey-Moody, A. (2009). Unimaginable bodies: Intellectual disability, performance and becomings. Brill Academic Publishers.

- Hultman, K., & Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Challenging anthropocentric analysis of visual data: A relational materialist methodological approach to education research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(5), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2010.500628

- Jackson, A. Y. (2017). Thinking without method. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(9), 666–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417725355

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. Routledge.

- Kelly, J. (2008). The anthropology of assemblages. Art Journal, 67(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2008.10791291

- Lather, P., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2013). Post-qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 629–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788752

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education: Introducing an intra-active pedagogy (contesting early childhood). Routledge.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2011). Investigating learning, participation and becoming in early childhood practices with a relational materialist approach. Global Studies of Childhood, 1(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2011.1.1.36

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2012). A diffractive and Deleuzian approach to analysing interview data. Feminist Theory, 13(3), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700112456001

- Lenz Taguchi, H., & Palmer, A. (2013). A more “livable” school? A diffractive analysis of the performative enactments of girls’ ill-/well-being with(in) school environments. Gender and Education, 25(6), 671–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2013.829909

- MacLure, M. (2013). Researching without representation?: Language and materiality in post-qualitative methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788755

- Mazzei, L. A. (2013). A voice without organs: Interviewing in posthumanist research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(6), 732–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788761

- Mcphie, J. (2018). I knock at the stone’s front door: Performative pedagogies beyond the human story. Parallax, 24(3), 306–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2018.1496581

- McVittie, C., Goodall, K. E., & McKinlay, A. (2008). Resisting having learning disabilities by managing relative abilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36(4), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2008.00507.x

- Murris, K. (2016). The posthuman child: Educational transformation through philosophy with picturebooks. Routledge.

- Nakken, H., & Vlaskamp, C. (2007). A need for a taxonomy for profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 4(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2007.00104.x

- Nayer, P. K. (2014). Posthumanism. Polity Press.

- Oliver, M. (2009). Understanding disability: From theory to practice (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pickering, A. (1995). The mangle of practice: Time, agency, & science. University of Chicago Press.

- Reddington, S., & Price, D. (2018). Pedagogy of new materialism: Advancing the educational inclusion agenda for children and youth with disabilities. International Journal of Special Education, 33, 465–481.

- Roets, G., & Braidotti, R. (2012). Nomadology and subjectivity: Deleuze, Guattari and critical disability studies. In D. Goodley, B. Hughes & L. Davis (Eds.), Disability and social theory (pp. 161–178). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schön, D. (1991). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. An Ashgate Book.

- Shakespeare, T. (2017). The social model of disability. In L. J. Davis (Ed.), The disability studies reader (5th ed., pp. 195–203). Routledge.

- Smith, T. A., & Dunkley, R. (2018). Technology-nonhuman-child assemblages: Reconceptualising rural childhood roaming. Children’s Geographies, 16(3), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2017.1407406

- Stigler, J. W., & Hiebert, J. (1999). The teaching gap: Best ideas from the world’s teachers for improving in the classroom. Free Press.

- Takahashi, A. (2014). The role of the knowledgeable other in lesson study: Examining the final comments of experienced lesson study practitioners. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 16(1), 4–21.

- Taylor, A., & Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. (2015). Learning with children, ants, and worms in the Anthropocene: Towards a common world pedagogy of multispecies vulnerability. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 23(4), 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1039050