ABSTRACT

Intergenerational programs have benefits for both children and older adults; however, the ongoing pandemic has changed social situations across the globe. The focus of this article is on exploring transitions and transformations due to societal conditions and demands that drive the implementation of intergenerational programs during a time of a global crisis that is the COVID-19 pandemic. Through an online survey form and focus group discussion, a total of 64 kindergarten practitioners shared their perspectives on intergenerational programs between young children and older adults in kindergartens in Norway. Kindergarten practitioners identified challenges that hinder intergenerational programs in kindergarten settings during the pandemic, as well as conditions that facilitate its implementation. Implications from this research indicate the need to think differently to be able to provide children with intergenerational experiences in kindergarten settings in Norway even during the pandemic and beyond.

Introduction

The global pandemic brought about by the COVID-19 virus and its mutations can be considered a time of a glocalFootnote1 crisis. It has posed unprecedented societal conditions and demands to nations and local communities in many ways – work-force dynamics have shifted to virtual platforms, schools and universities have been closed temporarily and re-opened with very strict regulations, airports and borders are being monitored and controlled. This time of crisis lends to the concept of glocality wherein local communities are still following health and safety protocols to prevent the spread of the virus more than a year after the start of this global phenomenon. As such, societies, institutions and individuals have been subjected to changes in order to cope with the demands of the times. Further, and important to note is, this situation has inevitably impacted children’s lives and the institutions that they participate in – such as the family and early childhood education and care (ECEC) settingsFootnote2, including the many programs and activities they engage in (United Nations Citation2020).

This period has sparked the interest of researchers to explore and recognize young children’s perspectives and voices from different parts of the world like England, Scotland, Italy and New Zealand (Pascal and Bertram Citation2021; Mantovani et al. Citation2021), which speaks of possibilities and opportunities despite the challenges posed by the crisis. Further, coping responses of early childhood professionals were explored in the U.S.A. and Latin American countries (Atiles et al. Citation2021) in addition to those of Nordic countries Sweden and Norway (Samuelsson Pramling, Wagner, and Ødegaard Citation2020). Furthermore, the socially distanced ‘new normal’ educational set-up was problematized (Formosinho Citation2021) as it poses questions to the future of institutional programs in the light of the pandemic. Common to these studies is the framing of the glocal crisis as a space for critical reflections, lessons and examinations of societal, material and environmental conditions crucial to children’s participation in daily lives.

Intergenerational programs

Intergenerational engagements, or more informal interactions between different generations, happen in family and community settings. However, there are circumstances when social interactions between younger and older age groups need to be deliberately facilitated such as through intergenerational programs. Intergenerational programs are characterized by intentional partnerships and collaborations of different actors and institutions to bridge and encourage different generations to build relationships with each other (Oropilla and Ødegaard Citation2021). Factors that have contributed to the genesis of intergenerational programs include migration histories, rising numbers of older adults that are socially isolated, emerging research focusing on generation gap and conflicts (Newman Citation1995; Newman, Ward, and Smith Citation1997). The birth of intergenerational programs also roots from study findings wherein children express negative views or perceptions of older adults (Seefeldt Citation2008; Holmes Citation2009).

Examples of intergenerational programs include the Together Old and Young (TOY) Project initiative wherein the TOY Project Consortium examined different intergenerational programs in seven European countries: Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain (TOY Consortium Citation2013b). Different activities in varying milieus that the younger generations and the older adults do together were documented as an acknowledgment of the benefits of having intergenerational activities between children and older adults (Airey and Smart Citation2015; Agate et al. Citation2018; Cartmel et al. Citation2018; TOY Consortium Citation2013a). This includes young children learning about community traditions, local history and values, and the elderly feeling more valued and useful to society.

Intergenerational programs in early childhood institutions offer movements towards a more sustainable future. As this study shows, kindergartens are places where different generations can meet and interact, this could mean children, parents, grandparents, but also elderly in local communities through intergenerational programs. Although intergenerational programs and practices exist, there is still little research and documentation about them in academic publications. These programs are emerging and still considered relatively new in ECEC (McAlister, Briner, and Maggi Citation2019). In a scoping literature review, it was found that there are knowledge gaps that can be filled through intergenerational research that include the youngest children from different countries (Oropilla Citation2021). In addition, historically, the literature of intergenerational programming has not paid enough attention to what happens to intergenerational programs after they are planned and implemented (Kaplan, Sanchez, and Hoffman Citation2017). As such, this paper that has Norway as its research context contributes to this international pool of knowledge.

Study context: Norway

In Norway, changing demographics (Gleditsch Citation2020) combined with migration contribute to young children growing up away from grandparents (Leknes and Løkken Citation2020). Furthermore, as a welfare state, Norway ensures that the youngest children and older adults are cared for through public health and social services such as kindergartens and elderly homes. It is in these institutions that youngest children and oldest adults spend most of their days in, particularly as 92.8% of children aged one to five years attended kindergarten in 2020 (Statistics Norway Citation2021a) whereas 28.9% of the population over 80 years old have availed of home care services for the elderly (Statistics Norway Citation2021b). KindergartenFootnote3 places are provided not just for care services while parents work, but also with the recognition of its importance to children’s development as human beings and as arenas for cultural formation, also referred to as Bildung or danning in Norwegian (Ødegaard and Krüger Citation2012).

These societal trends and situations point to why intergenerational programs are important to include in young children’s activities. There are some existing intergenerational programs in Norway that involve kindergartens such as those coordinated by CitationLivsglede for Eldre (Joy of Life for the Elderly) a non-profit, a non-government foundation organization in Norway that helps create meaningful everyday lives for the elderly (Livsglede for Eldre Citation2020). These initiatives are locally better understood as generasjonsmøter, which translates to ‘generational meetings’ in English (Oropilla and Fahle-Johansen Citation2021). In these programs, meetings between the children and elderly transpire within the realms of their institutions that adhere to national and local regulations, as well as the Norwegian Framework for Kindergartens which is locally referred to as Rammeplan (Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training Citation2017).

During the pandemic, most kindergartens had to close for six weeks while some had to find a way to remain open to support the children of healthcare workers before gradually re-opening again in April 2020, with stricter regulations (Ødegaard and Hu Citation2021). Kindergartens in Norway have had to comply with international guidelines and national restrictions to limit physical contact and follow hygiene protocols to lessen infection risks (Samuelsson Pramling, Wagner, and Ødegaard Citation2020). Several challenges have been reported due to the regulations which include the following: (1) staffing challenges to function with smaller cohorts of children; (2) less time for planning and preparation; (3) increased cost for hiring substitute staff and hygiene tools; and (4) scarce information about the children at home in family settings (Samuelsson Pramling, Wagner, and Ødegaard Citation2020; Ødegaard and Hu Citation2021).

As such, this paper is timely in light of the unique demands to nations, institutions and individuals to change and transition to different ways of functioning. Intergenerational programs have had to find new approaches to make connections especially as the oldest adults became most at risk for getting infected (Thang and Engel Citation2020). In this light, this paper aims to explore the changes in terms of transitions and transformations in societal, material and physical conditions for intergenerational programs to happen between young children and older adults in kindergartens in Norway, particularly during a time of crisis. Specifically, the following research questions guided this study: Which conditions can be considered ‘facilitating’ or ‘hindering’ to the implementation of intergenerational programs in kindergartens, and how can these programs be implemented despite the COVID-19 pandemic, and post-pandemic?

Theoretical underpinnings

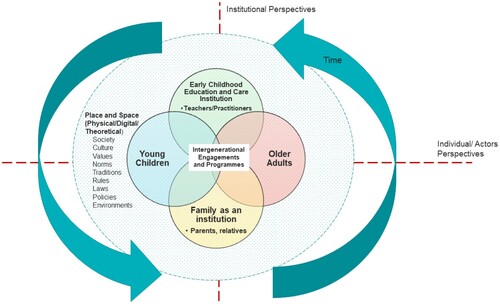

This project draws on Hedegaard’s wholeness approach to understand intergenerational programs in Norway on societal and institutional levels. Hedegaard’s (Citation2009) work is an extension of Vygotsky’s (Citation1998) cultural history intertwining culture to learning and development. Particularly she posits that transitions and transformations occur through interactions with other people in everyday practice and the situations around them – a perspective that is highlighted in this paper. Hedegaard’s wholeness approach (Citation2008) offers three levels of understanding to see the learning and development process as a whole – through societal perspective, institutional perspective and an individual perspective. Further, Hedegaard’s model considers the motives of activities. She had been influenced by Leontiev’s (Citation1978) view of motives where the true motive lies in the object of the activity that serves as the driving force that determines the direction and differences of activities. Herein, motives for having intergenerational programs in kindergartens in Norway are used as a frame for analysis. In this paper, institutional intergenerational programs and practices are viewed as activity systems that serve as the unit of analysis (see ). We have taken inspiration from Hedegaard’s model in understanding intergenerational programs. As shown in the model, we take into account the time and the place where these programs are situated.

Figure 1. Model of intergenerational programs from Oropilla and Ødegaard (Citation2021).

Kindergartens are institutions that have different activity settings (Hedegaard Citation2012) where children participate in intergenerational programs and practices through the support of early childhood practitioners, and where they transition from one institution to another. The transitions and transformations stem from demands and practices embedded in the children’s social situations (Hedegaard Citation2014, Citation2008, Citation2009). Hedegaard (Citation2014) explains demands and conditions in social situations can be broadly understood as the forces surrounding children and their surroundings that are located in their activity settings. Motives are manifested in the personal intentions of the participants within the activity setting (Hedegaard Citation2014), and in this case, are the deliberate and intentional decisions regarding the inclusion of intergenerational practices expressed by the early childhood practitioners. These motives are subject to the conditions of the time, allowing space for transitions and transformations to include intergenerational practices in kindergartens.

Methods

In order to gain institutional insights to the conditions integrated in the transitions and transformations intergenerational programs have had to go through due to the pandemic, Norwegian kindergarten practitioners were enjoined to take part in an online survey. Access to research participants was facilitated through a collaboration with CitationLivsglede for Eldre who helped with validating the questions included in the survey, the emerging trends from the data and forwarded the link of the online survey form to their contacts. In addition, email and social media platforms such as Facebook groups were used to invite kindergarten practitioners.

The online survey form was created in the SurveyXact platform and was developed ad hoc. It had closed questions to determine participants’ profiles and open-ended questions designed to gain insights into the changes and conditions intergenerational programs in kindergartens have faced during the pandemic. Some topics asked were on typical activities prior and during the pandemic, the materials, spaces and tools used and the reasons for using these, and factors that prevented and/or facilitate implementation of these programs. This online survey form was live from November 2020 until May 2021 and was completed by 58 early childhood practitioners from 27 different Norwegian municipalities. The respondents are 97% female, 70% have bachelor’s degrees, 41% are principals (styrer), 43% are pedagogue leaders (teachers). As the research design involves a self-selecting sample, we acknowledge the limitation of the findings and careful consideration of the conclusions as these cannot be generalized due to the possibility of overrepresentation of subgroups of participants who are more interested in the topic (Khazaal et al. Citation2014). Additionally, to supplement and validate responses from the online form, a group of six early childhood practitioners – three females and three males from three different municipalities (Oslo, Sandnes, Bergen) – were invited to a focus group discussion (FGD) through Zoom in March 2021. Open-ended questions were asked in order to probe kindergarten practitioners’ thoughts regarding intergenerational programs. Since the researcher is not a native Norwegian speaker, the FGD was conducted with the help of a Norwegian research assistant so the participants could comfortably respond to the questions.

This multimethod research (Creswell Citation2015) employed digital and low infection risk approaches which have been included in the list of methods for doing fieldwork in a pandemic (Lupton Citation2021). This study followed ethical research standards and was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), securing informed consent for voluntary and anonymous participation. In the presentation of results, quotes of participants from the online survey are assigned number codes (ex. OSP0), and from FGD participants are assigned pseudonyms (ex. FGD_Tina).

Data analysis

Thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) and Hedegaard’s principles for interpreting research protocols (Citation2008) were used to analyse the data generated. Data from the online form were extracted and translated to English. Data from the FGD were also transcribed and translated to English. The researcher made an Excel spreadsheet where data from all sources were saved. Several rounds of reading and re-reading followed to be familiarized with the data generated in both the original language and the translations. These are part of what Hedegaard (Citation2008) refers to as common sense interpretation as the first level of data analysis. As some of the transcriptions had to be translated, there are risks to data validity and original meaning which could lead to mistrust of participants (Pym Citation2004). To mitigate these risks, data were validated through the multimodal design of the research (Creswell Citation2014), and by having stakeholder groups confirm the data generated (Emmel Citation2013). In this case, member checking for validity was through the collaboration with the organization CitationLivsglede For Eldre, as well as the researcher’s supervisor who is a local of the research context. Stakeholder validation also happened as part of the situated practice interpretation in which theoretical concepts and its patterns are formulated in relation to the research aims, as well as in the thematic level interpretation where the emerging conceptual patterns from the data are reduced to formulate new concepts in the research (Hedegaard Citation2008). Further, a matrix was created to organize and summarize the thematic interpretations emerging from the data. Because this research is exploratory, open-ended responses from both the online form and the FGD were analysed inductively and assigned codes to answer the research questions (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Coding and organization of themes centered on the transitions and transformations of societal, material and physical conditions on intergenerational practices due to the pandemic. In addition, these conditions have been further organized based on its facilitating and/or hindering functions to the implementation of intergenerational programs in kindergartens in Norway.

Findings and discussions

Findings are presented under the themes emerging from the data, aligned with the research questions. These themes are (1) transitions and transformations to intergenerational programs in Norway during the time of a pandemic; (2) hindering and facilitating societal, environmental and material conditions and demands driving intergenerational programs in kindergartens in Norway; (3) thinking differently as means to move forward. Vignettes from some participants are presented for each theme identified.

Transitions and transformations of social situations due to the pandemic

Kindergarten practitioners in Norway have reported several transitions and transformations in generasjonsmøter practices in kindergartens during the pandemic. These transitions and transformations are changes within the activity settings and the children’s social situations (Hedegaard Citation2014, Citation2008, Citation2009) that have had implications to intergenerational institutional programs and practices.

All participants reported that they have had to stop having generasjonsmøter. They have provided similar responses when asked ‘how do you think the pandemic affected intergenerational programs in kindergartens in Norway?’

Stopped completely. (OSP4)

I think it’s affected a lot. It has not been possible to carry out as relevant meeting groups belong to the risk group. (Nursing homes, elderly housing, housing community). (OSP23)

I know that from March last year grandparents were not allowed to pick up at the kindergarten anymore. We did not want them there to protect them of course. All elderly people were not allowed to come to the kindergarten because we did not want to get them infected with the coronavirus. (FGD_Daisy)

Kindergarten practitioners have also shared that most of the generasjonsmøter happen in elderly institutions even prior to the pandemic, but that outdoor spaces are now utilized more for the generasjonsmøter:

Covid-19 has influenced generational meetings so we can’t go inside to visit, but we must be outside. We cannot sit down with them and have that good conversation. (OSP21)

Further, kindergarten practitioners have reported changes in children’s family holidays and provided insights to the children’s affective development. This has brought about transformations, especially to children of different ethnic backgrounds who have had less visits to or from their own grandparents because of travel restrictions:

I also know for kids that a lot of their holiday plans were changed and things that they normally do had to be cancelled or changed and that they missed their grandparents. And I also see that the grandparents miss the kids. In Oslo, I see the older people as they move around and see a kid they go “oh.” They look at these kids and maybe they miss their own grandchildren or family. Or maybe they feel more alone. (FGD_Daisy)

I work in a very multicultural kindergarten, where ethnic Norwegian is the minority. I notice the difference between those who tend to travel and get visits from grandparents but can’t do this anymore. The grandparents can’t come here. They are very sad that Grandma and Grandpa are so far away and that they can’t come. It is mostly with the parents who are worried about the older generation. But the kids also miss them, they’re used to traveling, a lot of them. (FGD_Missy)

Also I know that the kids did not get to see their grandparents except on the phone so a lot of kids came to me and said “yes, my grandmother is inside the phone.” And they showed me their phones. And they pointed to their parents’ phone and said that grandma – and they wanted to call. So they needed more screen time for both generations. Maybe it is good for the elderly people that they learn more to use FaceTime and Skype. (FGD_Daisy)

There was this girl who told me that her baby sister does not know her grandmother. “I know her but she does not because she has only seen them on the computer. And it is not the same,” she told me. “I know her for real and my baby sister does not.” I do not know when they are going to get to know each other so it is things like that are really touching … These meetings can become impossible. (FGD_Rachel)

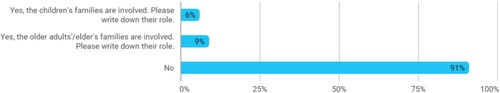

Societal conditions and demands that hinder or facilitate intergenerational programs and practices during the pandemic

Alongside the reported transitions and transformation to intergenerational practices, kindergarten practitioners have also communicated the following conditions and demands for intergenerational programs during the time of crisis. These demands are the driving forces within the environment that affect institutional practices (Hedegaard Citation2014). Responses have been classified to two subcategories – (1) hindering conditions and demands, which include the challenges and difficulties, and (2) facilitating conditions and demands, which include the motives that promote and foster intergenerational engagements and programs between young children and older adults.

Hindering conditions and demands

Kindergarten practitioners have explained how societal rules and regulations have lessened the opportunities for generasjonsmøter to happen. They voiced out that infection control became the priority, and generasjonsmøter have had to take the backseat:

It is not given priority and it may be that it “slips out” that one forgets to prioritize and include it back into plans. (OSP1)

It has not been prioritized in the last months because we have been thinking that [the pandemic] will soon be over but it is not coming because there are new waves and new mutations … (FGD_Rachel)

Due to the corona, we have not been able to complete the meetings “as usual”. It’s not so easy to carry out [activities] outdoors due to the weather and the health of the elderly. They cannot be out that long. (OSP17)

Many of the older people are not completely mobile, so they are present and watching us while we do different things. We’ve had feedback that the elderly thought it was fun to watch. (OSP25)

Disadvantage is that we cannot go with children across departments. We have previously gone with 15–20 children from three different departments. It does not work now when we cannot mix cohorts. Then it immediately becomes more difficult to walk alone with a small group of children, especially when we have to walk far along the road, etc. There are some restrictions. (OSP5)

Staffing is one of the biggest obstacles. (OSP42)

[It is] time-consuming planning. It takes time from other things. (OSP13)

The meeting will be perceived as a major event, which can be experienced violently for some of the vulnerable/sensitive children who may find it scary. The meeting will therefore require some time for planning and organizing in advance for the employees to ensure that all children have a good experience. (OSP17)

Kindergarten practitioners have also voiced out loss of motivation, but also of hope during this difficult time.

… I could not find the motivation. The bonuses I mentioned earlier [of children] meeting others in a societal perspective fell away. So I did not do that. But I was thinking some of the things that we have done during the pandemic is because it is already in the routines. We have found ways to do that anyway. Maybe we should not make too much effort of using the next half a year to respond to the pandemic but to focus forward and try to work to get generational meetings in our routines so when the next pandemic comes it will be easier to try to hold onto it. And keep some of it. (FGD_Mark)

Facilitating conditions

On the other hand, kindergarten practitioners have also pointed to conditions that have facilitated intergenerational programs even during a crisis. Some of these facilitating conditions have already been mentioned and discussed, such as the possibilities of the use of outdoor places, local spaces and digital artifacts for communication. However, data show that the planning and implementation of intergenerational programs are influenced by kindergarten practitioners’ personal motives. This is particularly important as Hedegaard (Citation2014) wrote that it is

because it is in the activity setting within a practice that the relations between institutional objectives and the demands from institutional practice can be studied in relation to a person's motives and the demands in the setting that are placed on both other people and material conditions. (p. 189)

In this study, kindergarten practitioners have shared why they think intergenerational meetings are important between young children and older adults, some of which are anchored on their own experiences and beliefs:

One of the reasons that it is a dream of mine is that a lot of elders have a lot of knowledge that they can share with younger people that they may not have. And [making sure] that this knowledge may not be lost. We can transfer it. Also, I think that the elders can feel more valuable and that they can contribute to the kids. And I know that from my grandparents and my son – they light up. It is a different kind of connection. I also see that the children are observing more, and they are calm. I can see from my observation that there is this kind of respect. And I think there is a lot of knowledge that we do not have because we maybe did not get the same possibility. All these small things if we create this intergenerational meetings I think we can learn a lot and so can the kids. (FGD_Daisy)

Another facilitating condition that emerges is also connected with early childhood practitioners’ personal attributes, and that is their creativity. Their responses and ideas as to how intergenerational programs can still be implemented during the pandemic are a manifestation of their creativity. Their responses entailed having to think differently and looking at other ways to create opportunities despite the crisis. These will be discussed in an emergent theme of its own in the next section.

Thinking differently

As above, kindergarten practitioners in Norway offered ways of thinking differently for other possibilities and opportunities for intergenerational programs to happen. Their ideas for activities that young children and older adults can do together are collated in the table below (see ):

Table 1. Kindergarten practitioners’ suggestions for generasjonsmøter.

Their suggestions imply glocal anchoring of content through the use of local artifacts such as snow, the weather, seasons and holidays. Further, they have also suggested the use of both older or more traditional artifacts such as letters or mail, as well as the newer digital artifacts. Possibilities of the use of both show collaborations with the perspective of time – the past meeting in the present towards the future.

One suggestion of having an idea bank so that families could come up with other suggestions to make intergenerational meetings happen speaks of an opportunity to further involve the family, and even their local communities or municipalities, in the program. In this way, intergenerational practices could involve more people, especially the children and older adults, and hence become something shared by all. It should be able to respond to one practitioner’s question: is it the parents’ responsibility to make intergenerational meetings happen?

At my kindergarten I have just a small role so it is not up to me to plan the meetings. I think we are still hoping that it will be over soon and we can meet properly instead of substitutes like through the screens. It is a difficult question to answer because there are many things that we have to think about as a kindergarten. The first thought of many pedagogues is who is in charge? Is it the parents’ task, maybe, to make sure the intergenerational meetings do not stop? That is how I feel about it now. I feel that this is not good enough but it is the reality. (FGD_Rachel)

Implications and conclusions

In this paper, we have explored kindergarten practitioners’ perspectives on intergenerational programs in Norwegian kindergartens during the COVID-19 pandemic with a particular focus on the transitions and transformations in the institutional practices. In this paper, the pandemic is considered a crisis from which institutional transformations have emerged. These transitions and transformations informed by the practitioner’s personal motives can be considered manifestations of opportunities to think differently, be creative and innovative.

Kindergarten practitioners reflected on the mediating and facilitating role they have in planning and implementing intergenerational practices in the kindergartens. Their personal motives revealed they have the capacity to deliberately include and/or exclude intergenerational practices in kindergarten activities in creative ways. While they were faced with challenging demands of the time forcing the different actors of intergenerational programs apart (refer to ), opportunities arose from providing supportive environmental and material conditions in institutions where they participate.

Also as such, implications to pedagogical practices arise from this study. First, data reveal that overcoming hindering conditions necessitates thinking differently and creatively about the inclusion of intergenerational programs such as the use of digital technologies. Practices that make use of mediating tools such as digital technologies could help sustain these programs despite ongoing regulations that still force societies to be physically apart.

Second, data reveal that there are possibilities to include families, communities, the children and older adults in planning and implementing intergenerational programs. This could begin with a key person who develops a personal motive that drives him/her to intentionally act.

Third, environmental conditions could be deliberately and intentionally designed to make physical places that are safe for all, especially during the time of a pandemic. Considerations for safety, infection control, mobility, level of functioning, interests could be included in the design. We argue that policymakers take these into consideration as part of the hope to attain sustainable development goals and in creating Smart Cities (Van Vliet Citation2011; UNESCO Citation2012; Song et al. Citation2017). In doing so, we not only create possibilities for further learning and development of children but equally to elders who are valuable members of society. More research is needed in early childhood education on how kindergarten practitioners create possibilities for the inclusion of elders, this gives rise to a hopeful pedagogy.

Institutional review board statement

The authors declare that the data were generated according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and their use is approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) on 12 May 2019, with reference number 953897, connected with the research project titled Stories of Intergenerational Experiences: The Voices of Younger Children and Older Adults.

Informed consent statement

Informed written and verbal consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the valuable feedback and support of Livsglede for Eldre in this research. They would also like to thank Jean Guadana for her help.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Glocal is an adjective that pertains to having both global and local characteristics, considerations, impact and interpretations (Ødegaard Citation2015).

2 Also henceforth referred to as kindergartens as it is better understood in the Norwegian context.

3 Officially called barnehage in the Norwegian context (Ødegaard and Hu Citation2021).

References

- Agate, J. R., S. T. Agate, T. Liechty, and L. J. Cochran. 2018. “‘Roots and Wings’: An Exploration of Intergenerational Play: Research.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (4): 395–421. doi:10.1080/15350770.2018.1489331.

- Airey, T., and T. Smart. 2015. “Holding Hands Intergenerational Programs Connecting Generations”.

- Atiles, J. T., M. Almodóvar, A. C. Vargas, M. J. A. Dias, and I. M. Z. León. 2021. “International Responses to COVID-19: Challenges Faced by Early Childhood Professionals.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (1): 66–78. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872674.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Busch, G. 2018. “How Families Use Video Communication Technologies During Intergenerational Skype Sessions.” In Digital Childhoods. International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Development, Vol. 22, edited by S. Danby, M. Fleer, C. Davidson, and M. Hatzigianni. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-6484-5_2.

- Cartmel, J., K. Radford, C. Dawson, A. Fitzgerald, and N. Vecchio. 2018. “Developing an Evidenced Based Intergenerational Pedagogy in Australia.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (1-2): 64–85. doi:10.1080/15350770.2018.1404412.

- Creswell, J. W. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. 2015. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research, Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Emmel, N. 2013. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach. London. https://methods.sagepub.com/book/sampling-and-choosing-cases-in-qualitative-research.

- Formosinho, J. 2021. “From Schoolification of Children to Schoolification of Parents? – Educational Policies in COVID Times.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (1): 141–152. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872677.

- Gleditsch, R. F. 2020. Et historisk skifte: Snart flere eldre enn barn og unge. Norway: Statistics Norway. (SSB).

- Hedegaard, M. 2008. Studying Children: A Cultural-Historical Approach. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Hedegaard, M. 2009. “Children’s Development from a Cultural–Historical Approach: Children’s Activity in Everyday Local Settings as Foundation for Their Development.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 16 (1): 64–82. doi:10.1080/10749030802477374.

- Hedegaard, M. 2012. “Analyzing Children’s Learning and Development in Everyday Settings from a Cultural-Historical Wholeness Approach.” Mind, Culture and Activity 19 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1080/10749039.2012.665560.

- Hedegaard, M. 2014. “The Significance of Demands and Motives Across Practices in Children’s Learning and Development: An Analysis of Learning in Home and School.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 3 (3): 188–194. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.02.008.

- Holmes, C. L. 2009. “An Intergenerational Program with Benefits.” Early Childhood Education Journal 37 (2): 113–119. doi:10.1007/s10643-009-0329-9.

- Kaplan, M., M. Sanchez, and J. Hoffman. 2017. Intergenerational Pathways to a Sustainable Society. Springer Nature. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47019-1.

- Khazaal, Y., M. V. Singer, A. Chatton, S. Achab, D. Zullino, S. Rothen, R. Khan, J. Billieux, and G. Thorens. 2014. “Does Self-Selection Affect Samples’ Representativeness in Online Surveys? An Investigation in Online Video Game Research.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 16: 7.

- Leknes, S., and S. Løkken. 2020. Befolkningsframskrivinger for kommunene, 2020-2050. Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå Statistics Norway.

- Leontiev, A. N. 1978. Activity, Consciousness, and Personality. Englewood Clifs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Livsglede for Eldre. “Ny tegnefilm – generasjonsmøter.” Livsglede for Eldre. https://livsgledeforeldre.no/ny-tegnefilm-generasjonsmoter/.

- Lupton, D. 2021. “Doing Fieldwork in a Pandemic (Crowd-sourced Document), Revised Version.” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1clGjGABB2h2qbduTgfqribHmog9B6P0NvMgVuiHZCl8/edit?usp=sharing.

- Mantovani, S., C. Bove, P. Ferri, P. Manzoni, A. Cesa Bianchi, and M. Picca. 2021. “Children ‘Under Lockdown’: Voices, Experiences, and Resources During and After the COVID-19 Emergency. Insights from a Survey with Children and Families in the Lombardy Region of Italy.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (1): 35–50. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872673.

- McAlister, J., E. L. Briner, and S. Maggi. 2019. “Intergenerational Programs in Early Childhood Education: An Innovative Approach That Highlights Inclusion and Engagement with Older Adults.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 17 (4): 505–522. doi:10.1080/15350770.2019.1618777.

- Newman, S. 1995. History and Current Status of the Intergenerational Field. Generations Together Publications, Pittsburgh Univ. Center for Social and Urban Research.

- Newman, S., C. R. Ward, and T. B. Smith. 1997. Intergenerational Programs: Past, Present, and Future. Washington DC, USA: Taylor & Francis.

- Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. 2017. “Framework Plan for Kindergartens: Contents and Tasks.” https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf.

- Ødegaard, E. E. 2015. “Glocality” in play: Efforts and dilemmas in changing the model of the teacher for the Norwegian national framework for kindergartens,” Policy Futures in Education 14 (1): 42–59. doi:10.1177/1478210315612645.

- Ødegaard, E. E., and A. Hu. 2021. “Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) Response to COVID-19 in Norway.” An International Collaborative Study and International Symposium: Childcare Response to Covid-19. Sejong-si, South Korea: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

- Ødegaard, E. E., and T. Krüger. 2012. “Studier av barnehagen som ‘danning’ sarena – sosialepistemologiske perspektiver [Studies of kindergarten as arena for cultural formation – Socio-epistemological perspectives].” In Barnehagen som ‘danning’sarena [Kindergarten as arena for cultural formation] , edited by Elin Eriksen Ødegaard, 19–49. Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget.

- Oropilla, C. T. 2021. “Spaces for Transitions in Intergenerational Childhood Experiences.” In Childhood Cultures in Transformation, edited by Elin Eriksen Ødegaard and Jorunn Spord Borgen, 74–120. Leiden: Brill | Sense. doi:10.1163/9789004445666_005.

- Oropilla, C. T., and E. E. Ødegaard. 2021. “Strengthening the Call for Intentional Intergenerational Programmes Towards Sustainable Futures for Children and Families.” Sustainability 13 (10): 5564. doi:10.3390/su13105564.

- Oropilla, C. T., and L. Fahle-Johansen. 2021. “Generasjonsmøter i barnehager – hvorfor er det viktig?” https://www.barnehage.no/barnkunne/generasjonsmoter-i-barnehager–hvorfor-er-det-viktig/217828.

- Pascal, C., and T. Bertram. 2021. “What do Young Children Have to Say? Recognising Their Voices, Wisdom, Agency and Need for Companionship During the COVID Pandemic.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (1): 21–34. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2021.1872676.

- Pym, A. 2004. “Text and Risk in Translation.” In Choice and Difference in Translation: The Specifics of Transfer, edited by M. Sidiropoulu and A. Papaconstantinou, 27–42. Athens: The National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

- Samuelsson Pramling, I., J. T. Wagner, and E. E. Ødegaard. 2020. “The Coronavirus Pandemic and Lessons Learned in Preschools in Norway, Sweden and the United States: OMEP Policy Forum.” International Journal of Early Childhood 52 (2): 129–144. doi:10.1007/s13158-020-00267-3.

- Seefeldt, C. 2008. “Intergenerational Programs – Impact on Attitudes.” Journal of Children in Contemporary Society 20 (3-4): 185–194. doi:10.1300/J274v20n03_19.

- Song, H., R. Srinivasan, T. Sookoor, and S. Jeschke. 2017. “Sustainability in Smart Cities: Balancing Social, Economic, Environmental, and Institutional Aspects of Urban Life.” In Smart Cities: Foundations, Principles, and Applications. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781119226444.ch18.

- Statistics Norway. “Kindergartens.” Statistics Norway (Statistisk sentralbyrå). https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/barnehager/statistikk/barnehager.

- Statistics Norway. “Sjukeheimar, heimetenester og andre omsorgstenester.” Statistics Norway (Statistisk sentralbyrå). https://www.ssb.no/helse/helsetjenester/statistikk/sjukeheimar-heimetenester-og-andre-omsorgstenester.

- Thang, L., and R. Engel. 2020. “Intergenerational Connections: Exploring New Ways to Connect.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 18 (4): 377–378. doi:10.1080/15350770.2020.1828725.

- TOY Consortium. 2013a. Intergenerational Learning Involving Young Children and Older People. Leiden: The TOY Project.

- TOY Consortium. 2013b. Reweaving the Tapestry of the Generations: An Intergenerational Learning Tour Through Europe. Leiden.

- UNESCO. 2012. “Shaping the Education of Tomorrow – 2012 Report on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development.” DESC Monitoring and Evaluation.

- United Nations. 2020. “United Nations Comprehensive Response to COVID-19: Saving Lives, Protecting Societies, Recovering Better.” https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_comprehensive_response_to_covid-19_june_2020.pdf.

- Van Vliet, W. 2011. “Intergenerational Cities: A Framework for Policies and Programs.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 9 (4): 348–365. doi:10.1080/15350770.2011.619920.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1998. “The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky. Volume 5.” Child Psychology.

- Wals, A. E. J. 2017. “Sustainability by Default: Co-Creating Care and Relationality Through Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Early Childhood 49: 155–164.