ABSTRACT

This thematic analytic qualitative study used participants’ oral narratives to examine primary Cymraeg, which is the Welsh language, and English-speaking adolescents’ perceptions regarding Cymraeg-speakers’ opportunities of using their primary language on social media. Twenty-three participants were interviewed (two Welsh/Bilingual-medium schools: males = 5, females = 6; two English-medium schools: males = 6, females = 6). All of the Welsh/Bilingual-medium participants were primary Cymraeg-speakers. Operating at the broad thematic level, both groups provided similar responses. However, inter-group variance might be inferred at the sub-thematic level where, for instance, Cymraeg-speakers identified a greater array of technical limitations preventing Cymraeg-speakers using Cymraeg within the social media domain. The potential consequences of an actual or perceptual linguistic imbalance on social media are discussed.

KEYWORDS:

Extant research suggests a proportion of Cymraeg-speakers (Cymraeg is the Welsh language) generally use English on social media (Cunliffe, Morris, and Prys Citation2013), and whilst engaging in internet activities per se (McAllister, Blunt, and Prys Citation2013). Whilst there is a suggestion that technical constraints prevent minority language speakers from using their primary language (i.e. an individual’s language of choice within the home) on social media (Cunliffe, Morris, and Prys Citation2013), an array of non-technical factors also inform minority language speakers’ choice of language on social media. These considerations include others’ languages, the use of English being considered more convenient, or not knowing many users on social media retaining an ability to communicate through the minority language (McAllister, Blunt, and Prys Citation2013). McAllister, Blunt, and Prys (Citation2013) noted also how primary language speakers’ restricted opportunity to use their primary language online might also be informed via a lack of awareness regarding the online channels accommodating their minority language. To appreciate Cymraeg within the digital context, it is first necessary to explore the history and vitality of Cymraeg. Please note that whilst Cymraeg-speakers also speak English, the term ‘Cymraeg-speakers’ refers to individuals whose first language is Cymraeg.

Cymraeg is a minority language within its own country with only 28.5% (equating to 861,700 people) of people aged three and over retaining an ability to speak Cymraeg (Welsh Government Citation2021a). In terms of demographic distribution, the Welsh Government (Citation2021a) indicated the greater concentration of Cymraeg-speakers are located in Carmarthenshire (90,600 speakers), Cardiff (89,700 speakers), and Gwynedd (89,200 speakers). Expressed as a percentage, the highest percentage of Cymraeg-speakers are in Gwynedd (75%) and the Isle of Anglesey (66%). The lowest percentage of Cymraeg-speakers are in Bridgend (17%) and Torfaen (17%).

Despite Cymraeg enjoying a relatively high level of prosperity with regard to the relative number of speakers, the history of Cymraeg relative to the majority language English is best described turbulent. Paradoxically, a State-sponsored nineteenth-century act of suppression supplies a hint regarding Wales’ unique linguistic and social identity within the broader context of the British socio-political landscape (Thomas Citation1977). The Education Act of 1870 compelled Cymraeg primary schools to instruct their children in English only, and this was ruthlessly enforced: any child overheard speaking Cymraeg was forced to wear a wooden placard around his/her neck inscribed with the letters ‘W.N.’, which stood for ‘Welsh Not’ (Edwards Citation2005; Khleif Citation1976; Madoc-Jones and Buchanan Citation2004). The placard was a visible reminder of the language’s reduced status. Implicitly, the practice of ‘W.N.’ suggested a division between the minority (Cymraeg) and majority (English) languages and their primary speakers, which underscored the inferiority of Cymraeg relative to English. Thus, the practice of ‘W.N.’ suggests a turbulent past for Cymraeg. Originating as a Celtic language spoken by the ancient Britons, Cymraeg has endured an undulating trajectory (Historic UK Citation2022): enjoying a degree of prosperity during the medieval period through the notable works of the poets Aneirin and Taliesin amongst others to the Middle Ages where famous manuscripts such as the Mabinogion were written in Middle Welsh, Cymraeg encountered its first major act of censure at the hands of Henry VIII’s Act of Union in 1536 that drastically affected Cymraeg’s status as an administrative language; however, via theologians, Cymraeg survived. Further threats to Cymraeg’s vitality were witnessed during eighteenth-century Industrial Revolution where Wales received an influx of English-speakers. As the twentieth century progressed, there was a realization that Cymraeg and its speakers were being unfairly treated, and this gave rise to the recognition of Cymraeg within Wales’ law courts. Thus, by slow degrees, the linguistic prejudices of the Tudor period were reversed and Cymraeg was once more spoken within the home, workplace, and school. Casting an eye toward the future there are indications suggesting a more prosperous Cymraeg existence; for instance, implicitly suggesting support at the highest political level, the Welsh Government’s (Citation2017) objective is to have one million Cymraeg-speakers by 2050. Further, minority and regional languages such as Cymraeg receive protection from the European Charter for Regional and or Minority Languages (Citation2022), with the Charter being ratified by the United Kingdom. The chequered history of Cymraeg raises an important question about the strength of Cymraeg within the present socio-linguistic landscape, and this aspect is addressed below.

It has been suggested that Cymraeg demonstrates a moderate degree of ethno-linguistic vitality (Giles, Bourhis, and Taylor Citation1977); it is spoken by over one-quarter of the population of Wales (Welsh Government Citation2021a), receives support from regional and national governmental offices, industry, mass media, religious, and cultural institutions (Harwood, Giles, and Bourhis Citation1994; Giles, Bourhis, and Taylor Citation1977; Welsh Government Citation2021b; Yr Eglwys yng Nghymru Citation2021), and Cymraeg-speakers have attained a degree of institutional control (EURYDICE Citation2020; Harwood, Giles, and Bourhis Citation1994). However, despite Cymraeg representation on social media (Honeycutt and Cunliffe Citation2010; Keegan, Mato, and Ruru Citation2015), the extent of its active use on social media remains uncertain, and there exists a possibility of Cymraeg becoming digitally extinct (Welsh Government Citation2018).

Adopting a holistic vision with respect to Cymraeg’s social media representation with respect to other minority languages, Keegan, Mato, and Ruru’s (Citation2015) study suggested Cymraeg is similarly represented within the microblogging-oriented (i.e. short messages including no more than 140 characters) Twitter platform. Focusing primarily on the te reo Māori language, data analysis of the Indigenous Tweets website (launched in March 2011 with the express purpose of connecting Indigenous language speakers) suggested a Twitter presence for an array of Indigenous languages including Basque, Haitian Creole, Irish Gaelic, Frisian (Netherlands), Kapampangan (Philippines), etc. Cymraeg was similarly represented. When the various languages were ranked according to the quantity of people ‘tweeting’ per Indigenous language, Cymraeg consistently held a top-three position out of the twenty Indigenous languages surveyed.

Online usage of Cymraeg frequently entails the incorporation of English words (Cunliffe Citation2019; Cunliffe and Harries Citation2007), not all primary Cymraeg-speakers use Cymraeg on social media (Cunliffe, Morris, and Prys Citation2013; McAllister, Blunt, and Prys Citation2013), and bilinguals do not always take advantage of opportunities for online Cymraeg usage (Cunliffe Citation2019).

A reduced opportunity to use one’s primary language on social media (whether imposed by technological restriction, opportunity, or a minority language speaker’s perception) might set in motion a chain of undesirable psychological associations. Conceivably, the prospect of being ‘forced’ to use the majority language on social media, which constitutes an assimilative and submissive response mechanism (Crystal Citation2000), transmits a message suggesting society per se might not place a high value upon the minority language and associated culture, which ultimately diminishes a minority language speaker’s level of self-esteem (Baker Citation1996; Brandt Citation1988). Self-esteem has been negatively associated with depression (Orth, Robins, and Roberts Citation2008; Orth et al. Citation2009), loneliness (Rosenberg Citation1965; McWhirter Citation1997), social anxiety (de Jong et al. Citation2012; Obeid et al. Citation2013), and social media dependency (Kuss and Griffiths Citation2011; Andreassen Citation2015). Concomitantly, Cymraeg-speaker believing opportunities to use Cymraeg on social media to be curtailed might be vulnerable to these psychological associations related to diminished levels of self-esteem, which would clearly be an undesirable and non-advantageous state-of-affairs.

However, there have been few, if any, studies focusing upon Cymraeg- and English-speakers’ perceptions regarding the opportunities to use Cymraeg on social media, especially from a key group of young people in schools. The key point-of-interest is whether perceptual differences prevail between primary Cymraeg- and English-speaking participants regarding Cymraeg linguistic opportunities on social media. Thus, the objective of the present analysis is to test the following hypothesis: primary Cymraeg-speaking participants will perceive fewer opportunities to use Cymraeg on social media relative to primary English-speaking participants.

The latter part of the review examines Cymraeg in the social media context with respect to linguistic revitalization, digital obstacles with respect to revitalization, and how social media impacts contemporary adolescents’ lives with regards self-esteem and identity construction.

The ‘good news’ is that initiatives are in motion to maintain and revitalize Cymraeg with regard to the on and offline worlds; for instance, implicitly suggesting support at the highest political level, the Welsh Government’s (Citation2017) objective is to reach one million Cymraeg-speakers by 2050. Encouragingly, the digital vitality of Cymraeg is further strengthened by the work of the University of South Wales’ Hypermedia Research Group (Hypermedia Research Group Citation2022), which conducts ‘research into the relationship between minority languages and information technology’ with a specific emphasis placed upon Cymraeg. With numerous years’ language technology experience, Bangor University remains proactive in the development of Cymraeg resources such as spelling and grammar checking applications, e-dictionaries, etc. (Cunliffe et al. Citation2022; Prys et al. Citation2021). However, despite the honest and noble intentions of the Welsh Government and esteemed academic institutions, practical problems remain, which conspire to curtail the digital unification of the Cymraeg-speaking collective; for instance, there is a recognition of access-related issues, which was an issue initially found by the then Welsh Assembly Government (Citation2003) when they showed that resolution of the ‘digital divide’ would facilitate social inclusion via the on-line unification of Cymraeg-speaking communities. The passage of time, it would appear, has failed to resolve the access issue, since the Welsh Government’s (Citation2019) public consultation revealed the majority of respondents referenced poor mobile connectivity and broadband services within certain parts of Wales with the problem being more pronounced within the rural regions. One of the consultation’s findings showed widespread public support for the Welsh Government’s digital inclusion program Digital Communities Wales; however, there was a conviction that greater financial investment was needed to ensure every Welsh community enjoyed access to high-speed broadband connections (Welsh Government Citation2019). Resolution of the broadband and connectivity issues are important since research into online second-line acquisition would implicitly suggest the digital unification of disparate Cymraeg-speakers would realize tangible benefits regarding Cymraeg-speakers’ linguistic skills, motivation, and confidence (Kabilan, Ahmad, and Abidin Citation2010). The proliferation of mobile technology has enhanced Cymraeg learners’ experiences; for instance, students experience a combination of formal and informal learning styles, studying from home, and taking advantage of micro-blogging to perfect their Cymraeg reading and writing skills (Jones Citation2015a; Citation2015b).

The digital unification of Cymraeg-speakers would suggest further benefits in terms of adolescent Cymraeg-speakers’ well-being. Removal of perceived or actual barriers regarding Cymraeg usage on social media would suggest societal recognition of Cymraeg-speakers’ first language, which would benefit Cymraeg-speakers in terms of their collective and individual levels of self-esteem (Baker Citation1996; Brandt Citation1988). The salience of adolescents’ self-esteem is augmented given empirical analyses demonstrating self-esteem’s negative association with an array of psychological variables such as depression, loneliness, and social anxiety, which were addressed previously. Extant research would suggest, therefore, enhanced opportunities of using Cymraeg on social media would benefit Cymraeg-speakers’ well-being. This last point is potentially significant since empirical data would suggest adolescents are a demographic spending significant periods of time on social media (O’Keefe and Clarke-Pearson Citation2011; YouGov Citation2019; Internet Safety Citation101 Citation2020). In addition to enhancing adolescent Cymraeg-speakers’ well-being, extant analyses have shown how the use of immersive technologies such as social media facilitate adolescents’ identity formation, also (Pempek, Yermolayeva, and Calvert Citation2009). Thus, initiatives enhancing Cymraeg-speakers’ opportunities of using their first language on social media would benefit Cymraeg-speakers in many respects such as linguistic ability, sense of self-esteem (and related psychological associations), and identity formation.

Method

Participants

Inclusion criteria were that participants must: attend a Welsh/Bilingual- or English-medium secondary school in Wales; be aged 12–15 years; and have read, understood, signed, and dated the consent form. Exclusion criteria were that the participant declined participation; withdrew during questionnaire completion; or the participant’s school elected to withdraw from the research. Twenty-three pupils volunteered to take part in the interviews: there were 5 males and 6 females from Welsh/Bilingual-medium schools who were all primary Cymraeg-speakers; and 6 males and 6 females from English-medium schools who were primary English-speakers. The mean age for the Welsh/Bilingual- and English-medium interviewees was 15 years. Four schools (two Welsh/Bilingual- and two English-medium) agreed to take part. The schools were located within South Wales and were randomly selected using a random number generator (RANDOM.ORG Citation2020).

Procedure

At the request of each school, participants were predominantly interviewed in pairs. Participants’ teachers were not present during the interviews. All interviews were facilitated by the researcher. Prior to each interview, participants received assurances regarding anonymity, the freedom to decline a response to any question, and the option of withdrawing from the interview at any time of their choosing without having to provide a reason. Encouraging an open response, the comparative question presented to Welsh/Bilingual- and English-medium school participants was identically worded: Does social media provide enough opportunities to communicate using Welsh? All interviews were conducted through the medium of English with no translations.

In accordance with Oppenheim (Citation1992), the interviewees were presented with an identically worded question (please see the previous paragraph) in order to attain the same level of meaning and understanding within interviewees’ minds. As observed by the latter author, attainment of true and equal understanding within all interviewees’ is unrealistic, but the pursuit of this ideal is the goal and avoidance of interviewer bias is the objective. The ultimate objective, therefore, was the attainment of data that was free of contamination through the interview process. Thus, the interview objective was to standardize the interview process across all interviews whilst simultaneously responding to interviewees’ words in an objective and non-influential manner, as recommended by Oppenheim (Citation1992). However, acknowledging interviewees’ different personalities and personal circumstances, the application of a pre-determined ‘perfect’ and equal template across all interviews was unrealistic (Banister et al. Citation1999). Thus, the interviewer’s position per interview was to impart an objective facilitative role wherein interviewees were at liberty to express their views freely.

Analytic design

The design adopts a primarily deductive method. The supportive rationale is predicated on the basis that the research question proceeded from a hypothesis that was informed by empirical analyses. The deductive approach was subjected to the six-step thematic analytic design proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), which has been widely used (Crompton et al. Citation2020; Tambling et al. Citation2021; Xu and Zammit Citation2020). The applied six-step process addressed the following in strict chronological order (Braun and Clarke Citation2006).

Data familiarization

Interviews were digitally recorded using a Phillips DVT2510 Voice Tracker Audio Recorder with Dragon Naturally Speaking software and were fully transcribed. The dual process of transcription and re-reading of transcripts afforded a higher degree of textual familiarity.

Generation of initial codes

Codes were non-numerical in orientation. Coding was undertaken by a single person and checked by the co-authors. The deployed codes were brief textual descriptions, referencing related concepts embedded within participants’ quotations, e.g. with respect to Cymraeg-speakers, some of the identified concepts were: ‘Cymraeg is a minor language’, ‘Cymraeg language is growing’, etc. Whilst there is no strict rule regarding coding, consistency of application across the entirety of the data set was sought, in that an identified code might relate to a single word or multiple words. Code descriptors (i.e. code names) were conceptual in nature, i.e. free of researcher interpretation.

Searching for themes

Having identified the various codes, the next step entailed the collation of related codes into designated themes. Pursuing the Cymraeg-speaker example referenced during the initial generation of codes, above, the codes: ‘Cymraeg is a minor language’, ‘Cymraeg language is growing’, and ‘Cymraeg language had died a bit’, comprised a theme entitled ‘Perception of the Cymraeg language’. Mind maps were deployed to better identify and demarcate themes and codes from one another. In one instance, one of the identified codes warranted the creation of sub-codes.

Reviewing themes

Having established an initial set of themes, the next step in the process entailed a review of the themes, to determine whether they ‘fitted’ the data, codes, and themes per se. As per Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), a two-step process was enacted. First, data was examined to determine whether the themes accurately reflected the transcribed data. Second, the mind maps were reviewed to provide assurance the themes also reflected the over-arching themes of the data.

Defining and naming themes

As a process of continual refinement, this stage essentially formed the ‘story’ of the participants’ quotations. Pursuing the Cymraeg-speaker example, illustrated during initial code generation, the theme ‘Perception of the Cymraeg language’ (accommodating the identified three codes), attracted an over-arching definition indicating the theme’s codes collectively reflected the participants’ belief regarding the vitality and future prospects of the Cymraeg language.

Producing the report

Whilst quantitative analyses might employ p-values, for instance, to prove or disprove a hypothesis, qualitative analysis must rely upon rather more subjective evaluations. To demonstrate support for the tested hypothesis, reliance was made upon participants’ quotations. Where available, the literature was employed to clarify and explain findings.

Results

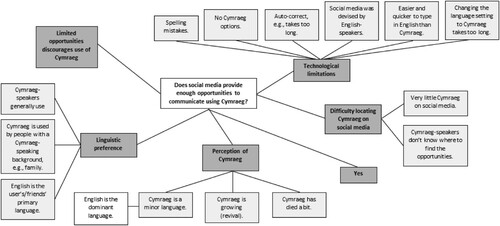

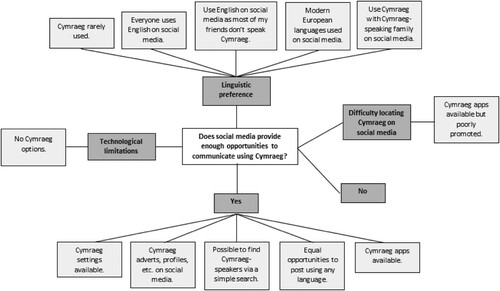

and present the mind maps (accommodating themes and related codes – including one sub-code), and and provide an explanation for each identified theme. The results from the Cymraeg-speaking participants are shown in and , and those from the English-speaking participants are shown in and .

Table 1. Cymraeg-speakers’ themes, sub-themes, and explanations.

Table 2. English-speakers’ themes, sub-themes, and explanations.

The thematic analytical approach revealed five broad themes for Cymraeg-speaking pupils ( and ), these being: technological limitations, difficulty locating Cymraeg on social media, linguistic preferences, perception of Cymraeg, and few opportunities.

There were four broad themes reported by English-speaking participants ( and ), these being technological limitations, difficulty locating Cymraeg on social media, linguistic preference, and opportunities available.

Three of the themes, technological limitations, difficulty locating Cymraeg on social media, and linguistic preference, were repeated for both groups. However, despite the broad thematic similarity, the groups differed with regard to certain sub-codes. Moreover, whereas the Cymraeg-speaking participants reported experiencing few opportunities to use Cymraeg on social media, the English-speaking participants suggested that they believed there were opportunities available. [Note: within the interview extracts, ‘W’ denotes a Cymraeg-speaker, and ‘E’ denotes an English-speaker.]

Technological limitations

Emerging as the dominant theme amidst the Cymraeg-speaking cohort, and to a lesser extent amidst the English-speaking cohort, participants’ responses referenced social media’s inability to adequately host and support the usage of Cymraeg acted as a deterrent for Cymraeg-speakers to use Cymraeg on social media in any meaningful way. Participants’ responses, for instance, suggested a dearth of Cymraeg options on social media: ’I don't think you can really set your language on your phone to Welsh. If you did, I reckon more people would speak more Welsh on social media’ (W8); ‘There’s no option to choose the Welsh language’ (W9); ‘On Facebook, we don’t have the option to have everything in Welsh’ (E4); ‘ … there’s no option to kind of change the language to Welsh if you want’ (E3).

Alluding to the linguistic emphasis of social media’s original software engineers, one participant suggested an absence of Cymraeg linguistic influence at the conception stage: ‘The people that made social media are probably English and I don’t think any of them are Welsh, so they probably, basically, just made them in English so there isn’t a way to make them Welsh’ (W4).

Numerous participants’ responses referenced the practical difficulties of using Cymraeg within social media, such as issues regarding the correct spelling of Cymraeg words: ‘ … it’s kind of harder to do especially with like spelling is a big part of it. With auto-correct it takes about five minutes to type a single sentence’ (W3); ‘There are websites and all sorts in Welsh but it’s just that maybe sometimes there might be spelling mistakes’ (W8).

The auto-correct feature within social media applications received criticism, as indicated by W3, above, which is an assertion shared by another participant: ‘To start off with, you’ve got auto-correct: I can’t text my friends something in Welsh because it will auto-correct to something completely different. So, I don’t bother’ (W10). Changing language settings also received criticism: ‘ … it takes you a while to have to change the language … ’ (W6).

Difficulty locating Cymraeg on social media

Although a greater proportion of Cymraeg-speaking participants referenced the difficulties associated with locating Cymraeg text on social media, this was an issue shared by both groups. Fundamentally, a core concern suggested Cymraeg per se was poorly represented on social media: ‘ … there’s not really a lot of Welsh elements on social media … There’s not enough on there to encourage people to use Welsh outside school on social media, so people just don’t bother to do it’ (W3); ‘The only Welsh I see is from the school page’ (W9).

Suggesting there are opportunities for Cymraeg-speakers on social media, one of the English-speaking participants suggested the key issue related to the inadequate promotion of Cymraeg opportunities: ‘Yes, there are a few different apps that you can use different languages, but it’s not promoted enough on, like, social media and stuff to [make] people want to learn Welsh and different languages’ (E7). Extending from E7’s observation, above, the difficulty associated with locating Cymraeg opportunities within social media was similarly identified: ‘I think there [are] enough opportunities but people just don’t know they are there’ (W9); ‘ … people don’t know it’s there’ (W8).

Linguistic preference

The linguistic preference theme featured strongly during Cymraeg- and English-speakers’ interviews. Inter-group consensus is suggested wherein participants within both linguistic settings suggested Cymraeg-speakers generally used English: ‘I do think people speak English more on-line even if they do speak Welsh’ (W1); ‘ … most people don’t bother speaking Welsh even though they go to a Welsh school … ’ (W4); ‘ … you don’t normally speak Welsh when you’re texting; it’s always English’ (W5); ‘ … people mainly talk in English or in [a] different language’ (E1); ‘ … the main language is English. Everyone uses English on-line’ (E12).

However, there was recognition that Cymraeg might be used when communicating with Cymraeg-speaking family members or where the speaker retains a particularly strong Cymraeg emphasis: ‘I think the only reason that people use Welsh is if they are a very Welsh person or if their family is Welsh … ’ (W4);

Like my grandma speaks Welsh and so does my mum – so I speak quite a lot of Welsh at home, and I would message them on Instagram, or something, in Welsh. So, I would talk to them in Welsh on Instagram. (E6)

Suggesting friends’ primary language influenced choice of language used on-line, participants within both groups, accordingly, attained a degree of consensus: ‘Most of my friends are outside school anyway and don’t speak Welsh’ (W10); ‘I don’t speak much Welsh on-line … social media because I don’t have many only-speaking Welsh friends’ (E5).

Demonstrating a macro-linguistic vision, one of the English-speaking participants, whilst indicating that perhaps Cymraeg might be considered less popular within the on-line domain, recognized the widespread popularity of not just English but, also, some of the more prominent European languages: ‘Obviously, German – the more modern foreign languages like French, German, Spanish, but not Welsh’ (E4).

Few opportunities discourages use of Welsh

Suggesting limited Cymraeg on-line linguistic opportunities, one Welsh-speaking participant’s response indicated a lack of opportunity rather quelled Cymraeg-speakers’ enthusiasm to use the language on social media: ‘There’s not enough on there to encourage people to use Welsh outside school on social media, so people just don’t bother to do it’ (W3).

For the most part, the perception that sufficient Cymraeg social media opportunities exist was principally demonstrated by English-speaking participants’ responses, with only a couple of the Cymraeg-speaking participants sharing the same belief. The below extracts communicate a perceptual belief regarding the availability of language settings, apps, and opportunities: ‘You can have settings where you can change it yourself … ’ (E8); ‘There are, like, Twitter accounts in the medium of Welsh, Instagram in Welsh’ (W1); ‘I think there might be something on Instagram’ (W3); ‘Yes, I think there are equal opportunities to everyone on-line because you can post or speak in whatever language you wish to’ (E2).

Perception of Cymraeg

Inspecting responses from the Cymraeg-speaking cohort, participants presented an array of sub-themes. The more salient sub-theme suggested Cymraeg was a minor language, with English being the more dominant. The inference was that Cymraeg is less active within the social media context. In this sense, Cymraeg within the social media domain is considered the lesser language relative to English: ‘If you scrolled five times, you’d see English written all over it’ (W8); ‘ … I haven’t seen anything from anybody else speaking the Welsh language – only the English’ (W9); ‘ … I don’t see any Welsh on social media at all’ (W7).

Reflecting upon Cymraeg within a world-wide context, one participant simultaneously suggested, whilst there appears to be a Cymraeg revival, it remains a relatively unpopular language:

Don’t get me wrong, Wales – the Welsh language – is growing but compared to like the whole world it’s not that popular a language … compared to English especially. So, I think that you’re not really going to see a lot of it on social media. (W7)

Another participant, whilst recognizing the dearth of Cymraeg on social media, simultaneously suggested linguistic death and revival: ‘You’d probably see every language apart from Welsh because Welsh has died off a bit. But now we’re trying to get it back … ’ (W8).

Discussion

Driven by empirical research and the devised hypothesis, the execution of Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step process unearthed an array of themes and related sub-themes (i.e. codes) for Cymraeg- and English-speaking participants in respect to the research question, above. Many of the themes resonated with the empirically referenced analyses, above. Operating from a broad thematic perspective there was an over-arching similarity between both groups – although they differed with respect to many of the sub-themes. Simultaneously, participants’ responses upheld certain empirical propositions whereas others appeared to be contradicted.

Reflecting upon participants’ perceptions of Cymraeg within the social media domain, Cymraeg-speaking participants’ extracts suggested that English was the dominant language relative to Cymraeg (which should come as no surprise given the relative numbers of English- and Cymraeg-speakers, respectively, within the social media domain per se) and that Cymraeg was poorly represented, which runs contrary to Honeycutt and Cunliffe (Citation2010; Keegan, Mato, and Ruru Citation2015) who suggested social network sites created opportunities for people to communicate in Cymraeg. Whilst a perception of under-representation might not equate with actual diminution of the language, conceptually such a belief entertains the possibility of Cymraeg becoming digitally endangered, an assertion that has received attention at the political level (Welsh Government Citation2018). Despite a perception of Cymraeg being poorly represented within the social media context, there was a recognition of a Cymraeg revival, which appears to resonate with the Welsh Government’s target of achieving approximately one million Cymraeg-speakers by 2050 (Welsh Government Citation2017).

Related to the above sub-theme, an additional sub-theme, which is common to both groups, was the belief that most Cymraeg-speakers used English on social media, which aligns with empirical analysis. Participants’ belief that Cymraeg-speakers generally used English on social media resonates with Cunliffe, Morris, and Prys (Citation2013) who suggested 39.8%, 30.1%, and 30.1% of first language Cymraeg-speakers used English, a mix of English and Cymraeg, or all Cymraeg on Facebook, respectively. Although the scope of their study accommodated a broader array of on-line components (including social media), participants’ perceptions regarding online language used comply with McAllister, Blunt, and Prys (Citation2013), also. Accepting the proposition that a proportion of primary Cymraeg-speakers switched to English on social media encouraged the application of Crystal’s (Citation2000) assimilation theory, which conceivably transmitted a self-esteem reducing message suggesting societal devaluation of Cymraeg and the associated culture (Baker Citation1996; Brandt Citation1988). By way of partial explanation, a couple of the participants suggested Cymraeg-speakers’ usage of Cymraeg on social media might be influenced according to the primary language used by family and friends, which is an argument paralleling Cunliffe, Morris, and Prys (Citation2013) proposition. This raised the interesting issue regarding an end user’s intended audience. Cymraeg-speakers’ ability to communicate in English provided them with a choice of language to use online; for instance, when constructing and maintaining personal profiles (Cunliffe, Morris, and Prys Citation2013). Their choice, though, would appear to be influenced by a combination of conscious and subconscious factors such as the language spoken by the target audience. The target audience influence has been identified with respect to Twitter, also, whereby bilingual Cymraeg-English ‘tweeters’ used Cymraeg when communicating with fellow bilinguals; but switched to English when their tweets were not directed toward a specific user (Nguyen, Trieschnigg, and Cornips Citation2015). In this respect, it might be observed how Cymraeg-speakers’ qualitative text paralleled extant research. Potentially negating the Welsh Government’s one million Cymraeg-speakers by 2050 objective (Welsh Government Citation2017), an assertion presented by one Cymraeg-speaking participant suggested a lack of opportunity to use Cymraeg on social media acted as a deterrent against Cymraeg usage.

Predominantly expressed by Cymraeg-speaking participants, in an apparent contradiction with extant research suggesting few technical constraints prevented Cymraeg-speakers from using Cymraeg on social media (Cunliffe, Morris, and Prys Citation2013), participants’ words suggest an array of technical limitations conspired to discourage the use of Cymraeg on social media; for instance, participants suggested there were few or no options enabling Cymraeg-speakers to choose Cymraeg within social media. Contradicting the latter participants’ assertion, a proportion of the participants suggested that options were available. The perceptual distinction might, for instance, be attributed to the poor promotion of Cymraeg and associated opportunities on social media, which is an issue raised by some of the participants. Promotion – or a lack thereof notwithstanding, additional technical constraints were articulated. One of the identified sub-themes related to the spelling of Cymraeg words on social media, with the suggestion that Cymraeg-speakers’ usage of Cymraeg on social media became fraught with delay. The auto-correct feature on social media and time taken to adjust linguistic settings also received criticism.

Implicitly related to the Cymraeg promotion issue identified above, a couple of the Cymraeg-speaking participants expressed difficulty in locating Cymraeg on social media. Relatedly, whilst suggesting social media opportunities existed for Cymraeg, an English-speaking participant indicated that perhaps the poor promotion of Cymraeg opportunities on social media rather conspired against people’s usage of Cymraeg. Indeed, the difficulty in locating Cymraeg on social media was a repeated sub-theme. Whilst only a couple of the Cymraeg-speaking participants suggested Cymraeg social media opportunities existed, a greater proportion of the English-speaking participants indicated likewise, which might suggest a perceptual distinction between Cymraeg- and English-speaking participants per se regarding Cymraeg social media opportunities. Suggesting the prevalence of social media opportunities, articulated sub-themes suggested the existence of Cymraeg settings, availability of Cymraeg-friendly apps, and capability of running routine searches to locate fellow Cymraeg-speakers.

Upon reflection, that perceived technological constraints conspired against practical usage of Cymraeg on social media cannot be denied – based upon participants’ extracts and perceptions. Additionally, the poor promotion of Cymraeg social media opportunities appeared to hamper Cymraeg social media practice. Participants’ words also suggested Cymraeg and English enjoyed an imbalance with regard to social media dominance; that is, there appeared to be a perceptually constructed linguistic disequilibrium within the social media sphere. The perceptual reference is of potential significance since if Cymraeg-speakers believed there are few opportunities to use Cymraeg on social media and, additionally, believed English is the main language, they would be less inclined to use Cymraeg, thereby upholding the Cymraeg-English linguistic imbalance perception. Cymraeg-speakers’ perceptions, however, would appear to run contrary to reality, which suggested Cymraeg-speakers’ opportunities to use Cymraeg on social media are real (Honeycutt and Cunliffe Citation2010; Keegan, Mato, and Ruru Citation2015). This would further suggest that Cymraeg would benefit from better promotion regarding social media opportunities, which is a point raised in the previous paragraph. Paralleling McAllister, Blunt, and Prys (Citation2013) non-technical barriers, participants’ references to others’ languages determining the language spoken on social media suggests non-technical factors also influenced the choice of language used on social media.

Returning to the hypothesis, which stated Cymraeg-speaking participants perceived fewer opportunities to use Cymraeg on social media relative to English-speaking participants, the case for and against might be presented. Operating at the broad thematic level, the similarity of theme certainly materialized; for instance, participants within both groups recognized a difficulty in locating Cymraeg on social media. However, inter-group variance might be inferred at the sub-thematic level; for instance, whilst both groups identified technological limitations associated with Cymraeg usage on social media, Cymraeg-speaking participants’ broader array of sub-themes set them apart from their English-speaking counterparts who presented only one theme.

Casting eye toward the future, based upon Cymraeg-speaking participants’ words, it is clear that initiatives designed to promote Cymraeg usage on social media are required. The two prominent areas requiring resolution would be technological barriers to using Cymraeg on social media and the inadequate promotion of Cymraeg opportunities on social media. The Cymraeg-speaking community incorporating Cymraeg-speakers, formal and informal Cymraeg language-oriented organizations ought to work as one in a collective effort to promote the Cymraeg language within the social media domain. In this regard, Welsh/bilingual-medium schools might be employed as Cymraeg language online conduits for greater Cymraeg usage on social media and other online outlets. Perhaps the Welsh Government might oversee and baseline such an initiative, which would prove commensurate to their one million Cymraeg-speakers by 2050 ambition (Welsh Government Citation2017).

Operating from a practical perspective, Cymraeg-speakers’ narratives conveyed a degree of frustration regarding the difficulties of actively using Cymraeg on social media; for instance, the reported inaccuracy of auto-correct. In this regard, there exists an onus of responsibility upon the social media providers to improve their applications in order to adequately host minority and majority languages alike. Whilst social media providers might consider such an initiative both technically and financially non-conducive, from an ethnolinguistic vitality perspective (Giles, Bourhis, and Taylor Citation1977), the results might prove profitable. One cost-saving method social media providers could adopt would be to ‘borrow’ resources utilized by the better-resourced majority languages, which is a concept recognized by Cunliffe et al. (Citation2022). From a social media developmental perspective, this ‘borrowing’ concept offers a glimpse of how extant majority language technology and associated applications might be deployed to the benefit of minority languages such as Cymraeg at a relatively low cost. From the developers’ perspective, the reduced development costs associated with the ‘borrowing’ concept would remove in part one of the major obstacles currently discouraging major social media providers’ whole-hearted engagement with minority languages.

This study is not without its limitations. Whilst present analysis employed twenty-three participants and, accordingly, afforded a glimpse of contemporary adolescents’ perceptions, future studies would be encouraged to utilize a larger cohort. Accordingly, any attempt to generalize present findings ought to be caveated with this limitation. A further limitation is that the surveyed schools were located within South Wales. Concomitantly, it is observed how the language profiles between North and South Wales contrast with one another. Future studies would be encouraged to canvass an equal proportion of Cymraeg-speakers located within both geographic regions.

In summary, a case might be presented suggesting response similarity between both groups, refuting the hypothesis. Conversely, reflection upon the sub-themes, especially with respect to perceived technological limitations, encouraged the belief that Cymraeg-speaking participants perceived a greater array of obstacles preventing Cymraeg usage on social media.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard Jones

Richard Jones, Final year PhD student within Swansea University's Psychology Department. Conducts social media addiction research within the context of minority and majority language speakers. Previously researched motivational psychology within the secondary education system at Master of Philosophy level.

Irene Reppa

Dr Irene Reppa obtained a D.Phil from Bangor University, where she held a research Officer position for 2 years, before taking an Assistant Professor post in the Department of Psychology at Swansea University. Dr Reppa's research interest and publications fall into four broad categories: Object Recognition, Object-based Attention and Memory, Perception and Action, and Aesthetic Appeal and Performance. Dr Reppa's work has been supported by Unilever, SR-Research (Ltd.), the Economic and Social Research Council, The Leverhulme Trust, and the Wales Institute for Cognitive Neuropscience, and the Economic and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Phil Reed

Phil Reed obtained a D.Phil from University of York, held a Research Fellowship at University of Oxford, and a Readership in Learning and Behaviour at University College London, before taking a University Chair in Psychology at Swansea University. Professor Reed's basic and applied research interests include: Learning and Behaviour; Autism, Special Needs, and Educational Interventions; and Psychology and Medicine, including Internet Addiction and Uro/Gynaecological Health. Professor Reed has written several books, published over 230 papers, and been invited to present his work at international conferences. Professor Reed's research includes evaluation of interventions, services, and products in relation to psychological and behavioural factors impacting effectiveness. Professor Reed and his team have presented their work in Women's Health at the National Assembly for Wales, and were awarded the 'Medal of the President of the republic' of Italy in 2016 for scientific contribution to society.

References

- Andreassen, C. S. 2015. “Online Social Network Site Addiction: A Comprehensive Review.” Current Addiction Reports 2 (2): 175–184.

- Baker, C. 1996. “Educating for Bilingualism – key Themes and Issues.” Paper Prepared for Presentation at ‘Bilingualism and the Education of Deaf Children: Advances in Practice’ Conference, University of Leeds. Accessed June 29, 1996. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/000000302.htm

- Banister, P., E. Burman, I. Parker, M. Taylor, and C. Tindall. 1999. Qualitative Methods in Psychology. A Research Guide. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Brandt, E. 1988. “Applied Linguistic Anthropology and American Indian Language Renewal.” Human Organization 47 (4): 322–329. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44126738.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Crompton, C. J., S. Hallett, D. Ropar, E. Flynn, and S. Fletcher-Watson. 2020. “I Never Realized Everybody Felt as Happy as I do When I am Around Autistic People’: A Thematic Analysis of Autistic Adults’ Relationships with Autistic and Neurotypical Friends and Family.” Autism 24 (6): 1438–1448.

- Crystal, D. 2000. Language Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cunliffe, D. 2019. “Minority Languages and Social Media.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Minority Languages and Communities, edited by G. Hogan-Brun and B. O’Rourke, 451–480. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cunliffe, D., and R. Harries. 2007. “Promoting Minority-Language use in a Bilingual Online Community.” New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 11 (2): 157–179.

- Cunliffe, D., D. Morris, and C. Prys. 2013. “Young Bilinguals’ Language Behaviour in Social Networking Sites: The use of Welsh on Facebook.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 18 (3): 339–361.

- Cunliffe, D., A. Vlachidis, D. Williams, and D. Tudhope. 2022. “Natural Language Processing for Under-Resourced Languages: Developing a Welsh Natural Language Toolkit.” Computer Speech & Language 72: 1–20.

- de Jong, P. J., B. E. Sportel, E. de Hullu, and M. H. Nauta. 2012. “Co-occurrence of Social Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Adolescence: Differential Links with Implicit and Explicit Self-Esteem?” Psychological Medicine 42 (3): 475–484.

- Edwards, V. 2005. “When School is not Enough: New Initiatives in Intergenerational Language Transmission in Wales.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 8 (4): 298–312.

- European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. 2022. “The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages is the European convention for the protection and promotion of languages used by traditional minorities.” (coe.int) Accessed April 16, 2022.

- EURYDICE. 2020. “United Kingdom: Wales. Population: Demographic situation, languages and religions. Population: Demographic Situation, Languages and Religions | Eurydice (europa.eu).” Accessed June 21, 2021.

- Giles, H., R. Y. Bourhis, and D. M. Taylor. 1977. “Towards a Theory of Language in Ethnic Group Relations.” In Language, Ethnicity and Intergroup Relations, edited by H. Giles, 307–347. London: Academic Press.

- Harwood, J., H. J. Giles, and R. Y. Bourhis. 1994. “The Genesis of Vitality Theory: Historical Patterns and Discoursal Dimensions.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 108: 167–206. The genesis of vitality theory: historical patterns and discoursal dimensions. (arizona.edu) Accessed June 4, 2021.

- Historic UK. 2022. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/ Accessed March 1, 2022..

- Honeycutt, C., and D. Cunliffe. 2010. “The Use of the Welsh Language on Facebook.” Information, Communication and Society 13 (2): 226–248.

- Hypermedia Research Group. 2022. Computing and Minority Languages Group. University of South Wales. Computing and Minority Languages Group | University of South Wales Accessed February 27, 2022.

- Internet Safety 101. 2020. Cyberbullying Statistics. https://internetsafety101.org/cyberbullyingstatistics Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Jones, A. 2015a. Mobile Informal Language Learning: Exploring Welsh Learners’ Practices. Open Research Online. ELearning Papers 45 (6). Accessed March 15, 2021. http://www.openeducationeuropa.eu/en/paper/language-learning-and-technology

- Jones, A. 2015b. “Social Media for Informal Minority Language Learning: Exploring Welsh Learners’ Practices.” Journal of Interactive Media in Education 1: 7.

- Kabilan, M. K., N. Ahmad, and M. J. Z. Abidin. 2010. “Facebook: An Online Environment for Learning of English in Institutions of Higher Education?” Internet and Higher Education 13: 179–187.

- Keegan, T. T., P. Mato, and S. Ruru. 2015. “Using Twitter in an Indigenous Language: An Analysis of te reo Māori Tweets.” Alternative 11 (1): 59–75. Alternative 11(1) online_01.indd (waikato.ac.nz) Accessed March 15, 2021.

- Khleif, B. B. 1976. “Cultural Regeneration and the School: An Anthropological Study of Welsh-Medium Schools in Wales.” International Review of Education 22 (2): 177–192. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3443088.

- Kuss, D. J., and M. D. Griffiths. 2011. “Online Social Networking and Addiction – a Review of the Psychological Literature.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8 (9): 3528–3552.

- Madoc-Jones, I., and J. Buchanan. 2004. “Indigenous People, Language and Criminal Justice: The Experience of First Language Welsh Speakers in Wales.” Criminal Justice Studies 17 (4): 353–367.

- McAllister, F., A. Blunt, and C. Prys. 2013. “Exploring Welsh Speakers’ Language use in Their Daily Lives. Exploring Welsh Speakers’ Language in Their Daily Lives.” Beaufort Research. http://www.beaufortresearch.co.uk/BBQ01260eng.pdf.

- McWhirter, B. T. 1997. “Loneliness, Learned Resourcefulness, and Self-Esteem in College Students.” Journal of Counseling and Development 75: 460–469.

- Nguyen, D., D. Trieschnigg, and L. Cornips. 2015. “Audience and the use of Minority Languages on Twitter.” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 9 (1), Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14648.

- Obeid, N., A. Buchholz, K. E. Boerner, K. A. Henderson, and M. Norris. 2013. “Self-esteem and Social Anxiety in an Adolescent Female Eating Disorder Population: Age and Diagnostic Effects.” Eating Disorders 21 (2): 140–153.

- O’Keefe, G. S., and K. Clarke-Pearson. 2011. “Clinical Report – the Impact of Social Media on Children, Adolescents, and Families.” Pediatrics 127 (4): 800–804.

- Oppenheim, A. N. 1992. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement. London: Printer.

- Orth, U., R. W. Robins, and B. W. Roberts. 2008. “Low Self-Esteem Prospectively Predicts Depression in Adolescence and Young Adulthood.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95: 695–708.

- Orth, U., R. W. Robins, K. H. Trzesniewski, J. Maes, and M. Schmitt. 2009. “Low Self-Esteem is a Risk Factor for Depressive Symptoms from Young Adulthood to old age.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 118 (3): 472–478.

- Pempek, T. A., Y. A. Yermolayeva, and S. L. Calvert. 2009. “College Students’ Social Networking Experiences on Facebook.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 30 (3): 227–238.

- Prys, D., D. Jones, G. Prys, G. Watkins, S. Cooper, J. C. Roberts, P Butcher, L. Farhat, W. Teahan, and M. Prys. 2021. Language and Technology in Wales: Volume 1. Prifysgol Bangor University, Bangor. Language and Technology in Wales – Volume I (bangor.ac.uk) Accessed February 27, 2022.

- RANDOM.ORG. 2020. https://www.random.org/

- Rosenberg, M. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tambling, R. R., A. J. Tomkunas, B. S. Russell, A. L. Horton, and M. Hutchison. 2021. “Thematic Analysis of Parent-Child Conversations About COVID-19: ‘playing it Safe.’” Journal of Child and Family Studies 30: 325–337.

- Thomas, R. 1977. South Wales. Edinburgh: John Bartholomew.

- Welsh Assembly Government. 2003. A National Action Plan for a Bilingual Wales. Iaith Pawbe – A National Action Plan for a Bilingual Wales 2003 (valeofglamorgan.gov.uk) Accessed April 16, 2021.

- Welsh Government. 2017. Cymraeg 2050. A million Welsh speakers. Cymraeg 2050: A million Welsh speakers (gov.wales) Accessed June 19, 2021.

- Welsh Government. 2018. Welsh Language Technology Action Plan. WG34015 (gov.wales) Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Welsh Government. 2019. Connected Communities: Tackling Loneliness and Social Isolation. *summary-of-responses_2.pdf (gov.wales) Accessed April 15, 2021.

- Welsh Government. 2021a. Welsh Language Data from the Annual Population Survey: July 2019 to June 2020. Welsh language data from the Annual Population Survey: July 2019 to June 2020 | GOV.WALES Accessed April 24, 2021.

- Welsh Government. 2021b. Welsh Language. Welsh language | Topic | GOV.WALES Accessed June 20, 2021.

- Xu, W., and X. Zammit. 2020. “Applying Thematic Analysis to Education: A Hybrid Approach to Interpreting Data in Practitioner Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 1–9.

- YouGov. 2019. Teens use These Social Media Platforms the Most. Accessed October 21, 2020 https://today.yougov.com/topics/lifestyle/articles-reports/2019/10/25/teens-social-media-use-online-survey-poll-youth

- Yr Eglwys yng Nghymru. 2021. Eglwys yng Nghymru – The Church in Wales Retrieved 20th June 2021.