ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of spray-drying with two coating agents, maltodextrin (MD) and gum arabic (AG) on antioxidant activity, mineral content, proximate content and sensory evaluation. Results showed that spray-dried sample decreased significantly (P < 0.05) in caffeine content, from 3.8% in control sample to 1.6% in AG and 1.9% in MD. Fat content in spray-dried sample also declined significantly from 21.4% in a pre-dried sample to 0.8% in MD and 2.4% in AG. Antioxidant activities slightly decreased in both AG and MD samples while the mineral content of spray-dried samples significantly increased in AG as compared with MD sample. The significantly higher yield found in MD (72.85%) sample than AG (40.71%). Spray-dried Nigella sativa powders have viable potential in improving food quality that may be beneficial to consumers as well as to industry.

RESUMEN

El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar los efectos de la atomización de dos agentes protectores, la maltodextrina (MD) y la goma arábiga (AG) en su actividad antioxidante, contenido en minerales, contenido aproximado y evaluación sensorial. Los resultados mostraron que la muestra atomizada provocó una disminución significativa (P <0,05) en el contenido de cafeína, de 3,8% en la muestra control, hasta 1,6% en AG y 1,9% en MD. El contenido en grasa de la muestra atomizada también causó un declive significativo de 21,4% en la muestra pre-atomizada hasta 0,8% en MD y 2,4% en AG. La actividad antioxidante disminuyó ligeramente en las muestras de AG y MD mientras que el contenido mineral de las muestras atomizadas aumentó significativamente en AG en comparación con la muestra de MD. Se encontró un rendimiento significativamente más alto en la muestra de MD (72,85%) que en la de AG (40,71%). La Nigella sativa en polvo atomizada tiene potencial viable para mejorar la calidad de los alimentos que podrían ser beneficiosos para los consumidores, como también para la industria.

1. Introduction

Nigella (Nigella sativa L.; NS) or more commonly referred to as black cumin is an annual herbaceous plant belonging to the Ranunculaceae family (Al‐Gaby, Citation1998; Cheikh-Rouhou et al., Citation2007) which originates from Mediterranean Sea (El–Dakhakhny, Citation1963). NS seed is often ground and used as a substitute for black pepper. A flavourful tea may be enjoyed by simply crushing whole NS seeds and steeping into hot, though not boiling water (Goreja, Citation2003). Whole seeds can be spindled into salads and various dishes alike sunflower or sesame seeds. NS seed is also added to meat dishes, especially pates and ground meat mixtures as this herb can be used to prevent excessive oxidation due to presence of antioxidant properties (Sultan et al., Citation2009). In addition to its antioxidant capacity, the black seeds are shown also to be antiarthritic and positively affect the stomach, intestine, kidney, bladder, liver, circulation, respiration and immune system when consumed (Janfaza & Janfaza, Citation2012). The NS is also known to possess some therapeutic medicinal uses due to its hepatoprotective activity, antidiabetic activity, antimicrobial activity, anthelmintic activity and anti-inflammatory activity (Ahmad et al., Citation2013; Bakathir & Abbas, Citation2011; Chaieb, Kouidhi, Jrah, Mahdouani, & Bakhrouf, Citation2011; Cheikh-Rouhou et al., Citation2007; Hannan, Saleem, Chaudhary, Barkaat, & Arshad, Citation2008; Morsi, Citation2000; Salem et al., Citation2010; Umar et al., Citation2012).

Among the number of drying technologies, spray-drying has been widely used to produce instant powders (Quek, Chok, & Swedlund, Citation2007). Commonly optimized with process parameters suited to a specific product, the widespread use in food and food-related industries is due to its plethora of benefits among which include reduced volume and/or weight due to lower moisture content over liquid-based products and extended shelf life (Shrestha, Ua-Arak, Adhikari, Howes, & Bhandari, Citation2007).

There are three essential steps for basic spray-drying, namely atomization, drying gas and droplet contact and lastly powder recovery (Schwartzbach, Citation2010). In short, a spray-drying process starts when sample feed is atomized to form the droplet before its contact with a heated gas. Once the droplets come into contact with the hot air inside the drying chamber, the solvent in the droplets is evaporated immediately forming dry powdered products (Afoakwah, Adomako, & Owusu, Citation2012).

Currently, research on the processing of NS is only focused on cold-press extraction. To the best of our knowledge, there is barely any report available on the effect of roasting and drying of black seed on its quality (Kiralan, Citation2012). Hence, information generated from this study is expected to provide a better insight on the potential applications of NS product as substitute food and beverages due to its high pharmaceutical values.

Despite the wide usage of NS, there is currently no instant black seed drink in the market. Preparation of NS drink for daily basis could be a nuisance procedure with all the filtering process, especially in this fast-paced society. Convenient food such as instant beverage powder is in a rising demand (Lee & Lin, Citation2013).

Spray-drying is also commonly used with additional substances called carrier agents and commonly used carrier agents are maltodextrin (MD) and gum arabic (AG) because of its high solubility and low viscosity that aid in the spray-drying process (Quek et al., Citation2007). Presence of protein in AG is particularly advantageous because it contributes to its emulsifying properties which coupled its high solubility and low viscosity in water (aqueous)-based solutions, making it a highly viable carrier agent (Frascareli, Silva, Tonon, & Hubinger, Citation2012; Pitalua, Jimenez, Vernon-Carter, & Beristain, Citation2010). The objective of this study was to evaluate effects of spray-drying with MD and AG as carrier agents on the chemical properties and sensory evolution of the resulting NS powder. These include antioxidant activities, proximate, caffeine and mineral content.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample preparation and spray-drying

After conducting several preliminary tests, commercially roasted NS (Perak Malaysia) was dissolved in distilled water and agitated with magnetic stirrer. The sample was then filtered using a muslin cloth to remove the solid particles in suspension in order to facilitate the solution to pass through the nozzle atomizer during the spray-drying. AG and MD dissolved in distilled water were added to the filtered black seed solution (5% w/w). The mixture was stirred gently throughout the spray-drying process. A laboratory scale BUCHI Mini Spray Dryer B-290 (AG, Switzerland), with a standard orifice of 0.7 mm in diameter was used for the spray-drying. The parameters which were used in spray-dryer in this study included aspirator (100%) and compressor (30 bar) as well as inlet temperature (110°C, 120°C and 130°C) and feed flow rate (7%, 11% and 15%) shown in . Response surface methodology (RSM) was applied to find out the optimum condition of the used parameters (inlet temperature and flow rate). The spray-dried NS powder then was taken from the collecting vessel, weighted and packed in a resealable polyethylene bag and stored at room temperature until further analysis.

Table 1. Experimental design for spray-drying runs with their corresponding response values.

Tabla 1. Diseño experimental de ensayos atomizados con sus valores de respuesta correspondientes.

The powder yield was calculated according to the formula as follows:

where

WT = Total weight of powder collected after spray-drying

WF = Total solid content in feed

2.2. Experimental design and statistical analysis

Spray-drying conditions (inlet temperature (°C) and feed flow rate (%)) on the yield of the NS sample had been performed to get the optimal parameter ranges of the experiment. The RSM was used to design and analyse the experimental data using a Design Expert version 8.0.7.1 (Statease Inc., Minneapolis, U.S.A.). Central composite design (face centred) with two variables and three levels was applied to find out the response pattern and then to establish a model. The experiments consisted of 13 runs with 2 variables and 5 replicates of the central point for the estimation of pure error, as shown in . Influence of factors on independent variables (X1: inlet temperature and feed flow rate: X2) on the extraction yield (%) of the commercial roasted NS was presented according to the equation as follows:

where Y was the dependent variable predicted by the model (response), β0 was the constant coefficient of intercept, β1 and β2 were the linear effects, β11 and β22 were the quadratic effects, β12 was the linear-by-linear interaction. Inlet temperature (°C) and feed flow rate (%) were represented by X1 and X2, respectively, as the coded independent variables. Chemical analysis was carried out using SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York 1050–1722, United States).

2.3. Chemical analysis on powder produced

2.3.1. Proximate analysis

Proximate analysis was carried out as prescribed in the Association of Analytical Chemists methods (Committee, A. A. O. C. C. A. M, Citation2000). Analysis carried out included fat (AOAC method 960.39), moisture (AOAC method 950.46), ash (AOAC method 923.03), crude protein (AOAC method 960.52) and crude fibre (AOAC method 962.09).

2.3.2. Caffeine analysis

Extraction of caffeine content was performed with some modification to the methods by Atomssa and Gholap (Citation2011); Belay, Ture, Redi, and Asfaw (Citation2008). Approximately 50 mg of NSP was added to 25 mL of 80°C distilled water in a centrifuge tube and vortexed for 1 min. After 10 min of centrifugation in 3500 rpm (Kubota 4000 centrifuge, Japan), the supernatant was mixed with dichloromethane by volume ratio of 20:20 in a separating funnel for caffeine extraction. By inverting the separating funnel at least three times to allow mixing well, the mixture was then left for 30 min for extraction. The extract was then stored in beaker enclosed with aluminium foil. The extraction procedure was repeated four times with 20 mL of dichloromethane. The final extract was measured with UV-Visible spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Corp, Japan) with wavelength of 273 nm.

2.3.3. Mineral analysis

As suggested (Kealaher et al., Citation2015; Speight, Citation2015), with slightly modification, analysis of mineral elements for calcium (Ca), ferum (Fe), manganese (Mn) and sodium (Na) was conducted. About 1 g of dried samples were weighted and put into a microwave digestion vessel. The samples were wet acid digested with 10 mL of nitric acid (HNO3) in microwave digester (Mathews Mars 6 240/50, U.S.A.) for 1 h until colourless or pale yellow liquid was obtained.

The digested samples were diluted with 100 mL with deionized water. For calcium determination, 20 mL of lanthanum oxide solution was added to the sample prior to the dilution. Lanthanum oxide solution was prepared by mixing 50 mL of deionized water, 58.64 g of lanthanum oxide (La2O3) and 250 mL of HCl, then made up to 1 L in volumetric flask. The total amounts of Ca, Fe, Mn and Na in the digested samples were quantified by atomic absorption spectroscopy, (Perkin Elmer, 4100ZL). A series of standard solution was prepared in different concentrations (ranged from 0 to 4 ppm) depending on the sample. Standard curve was plotted and results obtained were expressed as ppm/sample.

2.3.4. Antioxidant properties

Sample extraction was done according to method modified from Sun-Waterhouse et al. (Citation2009). Approximately 0.5 g of defatted powder was used with 20 mL of distilled water for extraction in centrifuge tube. The mixture was shaken for 120 min at 200 rpm in a water bath (SW-23; Julabo, Eisenbahnstrasse 45, 77,960 Seelbach, Germany). The mixture was then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 30 min to obtain a clear supernatant (Kubota 4000 centrifuge, Japan). When the centrifugation was completed, the supernatant was carefully separated to be used in analysis for determination of phenolic content, DPPH free radical-scavenging assay, flavonoid content and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay. The extract preparations, as well as all the experiments were triplicated to ensure reproducibility.

2.3.5. Determination of total phenolic content (TPC)

Total phenolic content (TPC) of NS was determined with Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) assay based on a slightly modified method described by Singleton and Rossi (Citation1965). About 40 μL of extract was mixed with 3.12 mL of distilled water in aluminium foil-wrapped test tube, followed by 200 μL of FC reagent and 600 μL 20% (w/v) sodium carbonate solution. Mixing well the solution, it was then incubated for 30 min at 40°C (SW-23; Julabo, Eisenbahnstrasse 45, 77,960 Seelbach, Germany). Finally, the absorbance of the solution was measured using spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Corp, Japan) at 765 nm. Standard solution of gallic acid with known concentrations (0, 80, 160, 240, 320, 400, 480 mg GAE/g) was used to prepare a standard curve. The obtained result was expressed as gallic acid equivalent (mg GAE/g sample).

2.3.6. Determination of DPPH free radical-scavenging assay

The free radical-scavenging effect of the sample on DPPH was evaluated based on method described by de Ancos, Sgroppo, Plaza, and Cano (Citation2002). An aliquot of 10 μL extract was mixed with 90 μL of distilled water in wrapped test tube with lid, together with 3.9 mL of 25 mM DPPH methanolic solution. The mixture was then mixed well with vortex and stored in the dark for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 515 nm using UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Corp, Japan) against a blank. The result was exhibited in terms of percentage of DPPH inhibition according to the following equation:

where AControl is the absorbance of the blank and ASample is the absorbance of sample.

2.3.7. Determination of ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

A modified method as proposed by Benzie and Strain (Citation1996) was conducted to determine the total antioxidant activity of sample based on the reduction of Fe3+ ferric-TPTZ (tripyridyltrianzin) to a blue colour solution (Fe2+ ferric-TPTZ). About 3.8 mL of warmed FRAP reagent at 37°C was mixed with 200 μL of extract and mixed well. After 30 min incubation in dark at 37°C, the absorbance was read at 593 nm (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Corp, Japan) against a blank. A standard curve was made using the aqueous solution of ferrous sulphate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O) solution (200–800 μmol). FRAP reagent was prepared in the ratio of 10:1:1 by mixing 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 20 mM ferric (III) chloride hexantydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) and 2,4,6-tris (1-pyridyl)-5-triazine (TPTZ) solution in 40 mM HCl. The FRAP value was showed in terms of ferrous equivalent (μmol/mg of sample).

2.3.8. Determination of total flavonoid content (TFC)

Colorimetric assay by Ramamoorthy and Bono (Citation2007) was referred with slight modification to determine the total flavonoid content (TFC) of sample. A proper diluted 1.5 mL extract was mixed with 1.5 mL of 2% aluminium chloride (AlCl2) in methanol. After 10 min incubation at 37°C, absorbance of the mixture was read at 415 nm (UVmini-1240, Shimadzu Corp, Japan) against the blank. Blank was prepared by replacing the extract with distilled water in the mixture. A standard curve was prepared using (-)-Epicatechin (10–90 mg/L) to calculate the TFC. TFC was expressed on weight basis as mg (-)-Epicatechin equivalent (ECQ/g of sample).

2.3.9. Sensory evaluation

A sensory evaluation involving 30 semi-trained panellists were participated at sensory lab, Food Technology Division, Universiti Sains Malaysia to evaluate the sensory attributes such as appearance (colour), aroma and taste, texture (mouthfeel) and overall acceptability of the spray-dried product. The reconstituted instant black seed drink was served in warm with the brewed black seed drink as control. Every sample has different coded which made to the panellist as single blinded. The sensory evaluation was carried out as single blinded. A 9-point hedonic scale was applied in this evaluation with 1 score equals to dislike and 9 score equals to like extremely detailed shown in Appendix A (Watts & Watts, Citation1989).

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Analysis of response surfaces

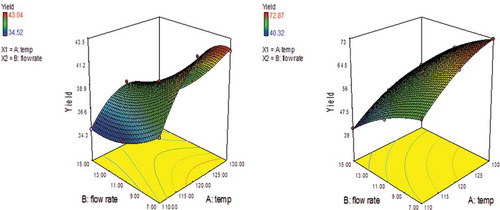

Spray-dryer has some critical elements that need to be concerned, which are the atomizer, airflow and drying chamber (Patel, Patel, & Suthar, Citation2009). According to the equation, effects of two independent variables, A: inlet temperature and B: feed flow rate on the yield obtained for NS were illustrated using surface response and contour plots of the quadratic polynomial models ().

Figure 1. Quadratic polynomial models of the yield of Nigella sativa with gum arabic (Left) and maltodextrin (Right) based on the effects of inlet temperature and flow rate.

Figura 1. Modelos polinómicos cuadráticos del rendimiento de Nigella sativa con goma arábiga (izquierda) y maltodextrina (derecha) en base a los efectos de la temperatura de entrada y el caudal.

The model adequacy can be checked to get the best fit of a designed model using coefficient of determination (R2) and lack of fit (Wang & Blaschek, Citation2011). A good fit model can be identified with ANOVA, which evaluated the significance of regression used to predict responses based on the sources of experimental variance (Bezerra, Santelli, Oliveira, Villar, & Escaleira, Citation2008).The coefficient of determination should be close to 1 or not less than 0.8 for a good fitted model (Koocheki, Taherian, Razavi, & Bostan, Citation2009) (Koocheki et al., Citation2009). Low values of R2 showed poor relevance of a model to explain the relationship between the variables (Xu, Gao, Liu, Wang, & Zhao, Citation2008; Xu et al., Citation2008). With a R2 of 0.9932 and 0.9987 for AG and MD, respectively, the designed model showed a great agreement in fitting the experimental data. Meanwhile, R2 can always be increased by adding more variables into the model. Thus, R2 should not be taken alone to validate the model. Koocheki and his company (Koocheki et al., Citation2009), suggested to evaluate the model with adj-R2 which showed the relativity of the parameters to the number of points in the design. Value greater than 90% is preferable for adj-R2. The experimental adj-R2 was 0.9883 and 0.9977 for AG and MD, respectively, found using the model shown in , supporting the criteria to be a good fitted model.

Table 2. ANOVA for response surface quadratic model Significant levels on the yield of Nigella sativa with maltodextrin and gum arabic.

Tabla 2. ANOVA del modelo de superficie de respuesta cuadrático Niveles significativos en el rendimiento de Nigella sativa con maltodextrina y goma arábiga.

To further strengthen the accuracy of the model, pred-R2 was compared with adj-R2 with a difference expected within 0.20. The pred-R2 determined the accuracy of the model in predicting the response value. The study found the pred-R2 (0.9585) which showed the model can be explained with 96% of the variability in the prediction of new observations. From the results, the difference between pred-R2 (0.9585) and adj-R2 (0.9883) was 0.0298 for AG and pred-R2 (0.9919) and adj-R2 (0.9977) was 0.0058 for MD. The variation was undersized enough to validate the model (Karthikeyan & Balasubramanian, Citation2010). The reliability of the model is denoted by coefficient of variation (CV). The CV is the standard deviation expressed as the percentage of mean, which is calculated by dividing the standard deviation with mean and 100 times. Generally, CV should be lower than 10% (Koocheki et al., Citation2009). Daniel (Citation1991) explained that high CV indicates high variation of the mean value, which in turn is not satisfactory to develop an adequate response model. Based on the result in , the CV of AG and MD was 0.72% and 70%, respectively, illustrating the reliability of this experiment. showed experimental design for spray-drying runs with its corresponding response values whereby optimization was applied to the range of inlet air temperature and feed flow rate which was 110–130°C and 7–15 mL/h respectively. Results indicated that process yield was the highest at higher inlet temperature (130°C) which was typical of the spray-drying process due to better efficiency of heat-to-mass transfer at higher temperatures, evident from the past work by Fazaeli, Emam-Djomeh, Ashtari, and Omid (Citation2012); and Tonon, Brabet, and Hubinger (Citation2008) whereby they studied spray-drying of black mulberry juice and acai pulp, respectively. showed one optimum level of independent variables with predicted values of the response generated from the software. Inlet air temperature and feed flow rate of 130°C and 7 mL/h for MD and 130°C and 12 mL/h for AG, respectively, were obtained as the optimal conditions for spray-drying parameters. Predicted values for optimal process yield were 70.73% and 38.92% for MD and AG, respectively, while experimental values were 72.85% and 40.71% for MD and AG, respectively, indicating the suitability of the model to be used for optimization of NS powder production.

3.2. Caffeine analysis

Caffeine content is commonly associated with coffee and tea which typically vary with varieties, roasting and brewing methods (Bunker & McWilliams, Citation1979). The caffeine content of NS, NS with MD and NS with AG was 3.863%, 1.940% and 1.613%, respectively, and the results showed that by adding carrier agents, caffeine content decreased significantly (P < 0.05) as compared with control presented in . When spray-dried at different temperatures, caffeine content would not be affected by inlet temperatures up to 220°C and outlet temperatures up to 115°C. Therefore, it is concluded that at a temperature of 130°C in this study, caffeine content is affected not by the heat but by its carrier agents. In terms of retention, MD had higher caffeine content as compared with AG, however, absence of carrier agent definitely resulted in highest caffeine content. Caffeine has been known to possess potent antioxidant properties making it a valuable constituent in beverages for human consumption (Lee, Citation2000). Presence of caffeine in foods is able to prolong shelf life which is generally advantageous (Nonthakaew, Matan, Aewsiri, & Matan, Citation2015).

Table 3. Proximate, caffeine and mineral content of Nigella sativa with carrier agents maltodextrin and gum arabic.

Tabla 3. Contenido aproximado, contenido de cafeína y contenido mineral de Nigella sativa con el agente portador maltodextrina y goma arábiga.

3.3. Mineral analysis

Cheikh-Rouhou et al. (Citation2007) reported that the main trace elements of NS were calcium and iron. showed that NS was the highest in Ca, followed by Na, Fe and Mn. Results indicated the capacity of AG as a carrier agent to incorporate minerals since Ca, Fe and Mn recorded highest values in comparison to MD and NS. Since these minerals are susceptible to damage during processing, preservation is important since they contribute to prevention of certain disorders and diseases (Murugesan & Orsat, Citation2012) and spray-drying with a suitable carrier agent is proven to be a method to preserve minerals.

3.4. Proximate analysis

showed that moisture content was significantly lower in MD and NS (1.12% and 1.34%, respectively) compared with AG. According to Codex Alimentarius, powdered products typically contain no more than 5% water/moisture (Alimentarious, Citation2006; Alimentarius, Citation1999; Codex, Citation1995) and according to moisture content, results ranged fits within prescribed Codex standards. Moisture content is an important parameter since it affects physical, chemical and microbiological stability of the end product whereby lower water activity via lower moisture content tends to increase shelf life of powders (Couto et al., Citation2011). The moisture content of spray-drying product was lower than 5% that expected our product maintained the acceptable standard quality for the shelf life extension (Rannou et al., Citation2015). Protein content in AG was significantly higher than MD due to higher protein content in AG itself (Dickinson, Citation2003).

Fat content was also significantly lower in all three samples with a steep drop from NS to MD and AG samples. Due to the low hygroscopicity nature of MD, it was plausibly a contributing factor in the reduction of fat in MD (0.83%) whereby the significant reduction in fat content was an advantage to both the drying process and also the output powder in terms of extending shelf life (Costa et al., Citation2015). Although no significant differences were observed between MD and AG, both values were significantly different as compared to carrier agents. Addition of carrier agents increased the amount of non-NS solids in the powder samples which significantly lowered the fibre content of resulting spray-dried powder (Grabowski, Truong, & Daubert, Citation2008). The significantly elevated carbohydrate percentages found that can be easily explained due to the addition of carrier agents, which was saccharides (MD) and polysaccharides (AG), the resulting powder was also higher in carbohydrate percentage (Costa et al., Citation2015).

3.5. Antioxidant analysis

The damaging impact of free radicals by initiating peroxidation has been proven to cause abundant health issues and degenerative ailments which can overcome by antioxidant present in abundant in plants (Khattak & Simpson, Citation2008). The phenolic compounds in NS are hydroxylated derivatives of benzoic and cinnamic, which contribute to overall antioxidant activities in the plant. With its relationship with antioxidant activities, the phenolic compounds are believed to possess the ability to scavenge free radical (Škerget et al., Citation2005). If higher polarity solvents are used for extracting phenolic compounds, high concentration of phenolic components can be found. For example, distilled water extract system can achieve a higher yield of phenolic compound than methanol/water extract system. Thus, water extraction method is selected in this experiment (Khattak & Simpson, Citation2008).

The most abundant flavonoids found in NS are picatechin, (+)−catechin, quercetin, apigenin, amentoflavone and flavone (Bourgou et al., Citation2008). TPC and TFC are highly degradable due to heating and oxidation (Fang & Bhandari, Citation2011; Patras, Brunton, O’Donnell, & Tiwari, Citation2010). The study observed 18–22% loss of phenolic compounds after spray-drying has been done.

From the results NS was significantly higher in TPC, TFC, DPPH and FRAP compared to AG and MD (), attributable to the difference in antioxidant capacity in carrier agent-infused powders as compared to the sample in its absence. This has been proven in the past whereby increasing MD in samples of amla juice reduced the TPC which in turn reduced the radical-scavenging capacity of the resulting powder (Mishra, Mishra, & Mahanta, Citation2014). In spite of the decrease in antioxidant capacity, MD was known to be able to preserve antioxidative activity (Costa et al., Citation2015) evident from the fact that there was little difference in FRAP value although significant. The higher and significantly different AG compared with MD was due to the nature of AG which had higher oxidative stability (Costa et al., Citation2015). There was also the contribution of flow rate during spray-drying with MD (7 mL/h) compared with AG (12 mL/h) whereby higher flow rate reduced contact with heat. Heat treatments typically cause loss of naturally occurring polyphenol compounds, hence leading to reduced antioxidant capacity (Daglia, Papetti, Gregotti, Bertè, & Gazzani, Citation2000).

Table 4. Antioxidant activities of Nigella sativa with carrier agent maltodextrin and gum arabic.

Tabla 4. Actividad antioxidante de Nigella sativa con el agente portador maltodextrina y goma arábiga.

3.6. Sensory evaluation

Panellist tasted NS samples and rated its overall palatability using a 9-point hedonic scale (1 = ‘dislike extremely’; 5 = ‘neither like nor dislike’; 9 = ‘like extremely’). The panellists judged each specific sensory parameter as acceptable with a mean score equal to 6 (like slightly) or higher. The subjects were then provided with samples of NS with different coating agent and the control NS. Five attributes including appearance, aroma, taste, texture and overall acceptability were evaluated by the panellists. From , taste and aroma differed significantly among samples, with NS score higher compared with mean score of MD and AG. Texture and appearance, however, showed no significant difference between samples. The overall acceptability of samples showed no significant difference with the score slightly higher than 6 indicating all the samples were at acceptable level.

Table 5. Sensory evaluation of Nigella sativa with carrier agent maltodextrin and gum arabic.

Tabla 5. Evaluación sensorial de Nigella sativa con el agente portador maltodextrina y goma arábiga.

4. Conclusion

The results showed that spray-dried sample decreased significantly in fat content as compared with pre-dried samples. The antioxidant activities also slightly decreased compared to pre-dried sample. Meanwhile, with the aid of coating agents, the mineral content of the spray-dried sample increased significantly than control samples. Significantly higher yield was recorded in MD (72.85%) sample than AG (40.71%). The treated samples were also acceptable sensorically. This study, therefore, concluded that the use of superheated steam can be used as an alternative conventional heat treatment for NS seeds to produce quality products. Spray-dried NS powders have viable potentiality to improve food product quality that may be beneficial to consumers as well as to industry.

Acknowledgements

Great appreciation goes to the Fellowship Scheme of the Institute of Postgraduate Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia and referees for useful comment and constructive advice in improving this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Afoakwah, A., Adomako, C., & Owusu, J. (2012). Spray drying an appropriate technology for food and pharmaceutical industry. Journal of Environ Science, Computer Science and Engineering & Technology, 1, 467–476.

- Ahmad, A., Husain, A., Mujeeb, M., Khan, S.A., Najmi, A.K., Siddique, N.A., … Anwar, F. (2013). A review on therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa: A miracle herb. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 3(5), 337–352. doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60075-1

- Al‐Gaby, A. (1998). Amino acid composition and biological effects of supplementing broad bean and corn proteins with Nigella sativa (black cumin) cake protein. Food/Nahrung, 42(05), 290–294. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3803(199810)42:05<290::AID-FOOD290>3.0.CO;2-Y

- Alimentarious, C. (2006). Codex standard for food grade salt. Codex Alimentarious. 166, 371–375

- Alimentarius, C. (1999). Codex standard for named vegetable oils. Codex Stan, 210, 1999.

- Atomssa, T., & Gholap, A. (2011). Characterization of caffeine and determination of caffeine in tea leaves using uv-visible spectrometer. African Journal of Pure and Applied Chemistry, 5(1), 1–8.

- Bakathir, H.A., & Abbas, N.A. (2011). Detection of the antibacterial effect of nigella sativa ground seedswith water. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines, 8, 2. doi:10.4314/ajtcam.v8i2.63203

- Belay, A., Ture, K., Redi, M., & Asfaw, A. (2008). Measurement of caffeine in coffee beans with UV/vis spectrometer. Food Chemistry, 108(1), 310–315. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.10.024

- Benzie, I.F., & Strain, J. (1996). The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Analytical Biochemistry, 239(1), 70–76. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0292

- Bezerra, M.A., Santelli, R.E., Oliveira, E.P., Villar, L.S., & Escaleira, L.A. (2008). Response surface methodology (RSM) as a tool for optimization in analytical chemistry. Talanta, 76(5), 965–977. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2008.05.019

- Bourgou, S., Ksouri, R., Bellila, A., Skandrani, I., Falleh, H., & Marzouk, B. (2008). Phenolic composition and biological activities of Tunisian Nigella sativa L. shoots and roots. Comptes Rendus Biologies, 331(1), 48–55. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2007.11.001

- Bunker, M.L., & McWilliams, M. (1979). Caffeine content of common beverages. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 74(1), 28–32.

- Chaieb, K., Kouidhi, B., Jrah, H., Mahdouani, K., & Bakhrouf, A. (2011). Antibacterial activity of Thymoquinone, an active principle of Nigella sativa and its potency to prevent bacterial biofilm formation. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 11(1), (1). doi:10.1186/1472-6882-11-29

- Cheikh-Rouhou, S., Besbes, S., Hentati, B., Blecker, C., Deroanne, C., & Attia, H. (2007). Nigella sativa L.: Chemical composition and physicochemical characteristics of lipid fraction. Food Chemistry, 101(2), 673–681. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.022

- Codex, S. (1995). Codex standard for whey powders. Standard CODEX Alimentarius. Revision 2003. Amendment 2006, 2010. Argentina.

- Committee, A. A. O. C. C. A. M. (2000). Approved methods of the american association of cereal chemists (Vol. 1). Eagan, MN: American Association of Cereal Chemists.

- Costa, S.S., Machado, B.A.S., Martin, A.R., Bagnara, F., Ragadalli, S.A., & Alves, A.R.C. (2015). Drying by spray drying in the food industry: Micro-encapsulation, process parameters and main carriers used. African Journal of Food Science, 9(9), 462–470. doi:10.5897/AJFS2015.1279

- Couto, R., Araújo, R., Tacon, L., Conceição, E., Bara, M., Paula, J., & Freitas, L.A.P. (2011). Development of a phytopharmaceutical intermediate product via spray drying. Drying Technology, 29(6), 709–718. doi:10.1080/07373937.2010.524062

- Daglia, M., Papetti, A., Gregotti, C., Bertè, F., & Gazzani, G. (2000). In vitro antioxidant and ex vivo protective activities of green and roasted coffee. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 48(5), 1449–1454. doi:10.1021/jf990510g

- Daniel, W.W. (1991). Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences (5th ed). New Jersey, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- de Ancos, B., Sgroppo, S., Plaza, L., & Cano, M.P. (2002). Possible nutritional and health‐related value promotion in orange juice preserved by high‐pressure treatment. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 82(8), 790–796. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0010

- Dickinson, E. (2003). Hydrocolloids at interfaces and the influence on the properties of dispersed systems. Food Hydrocolloids, 17(1), 25–39. doi:10.1016/S0268-005X(01)00120-5

- El–Dakhakhny, M. (1963). studies on the chemical constitution of egyptian nigella sativa l. seeds. II1) the essential oil. Planta Medica, 11(04), 465–470. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1100266

- Fang, Z., & Bhandari, B. (2011). Effect of spray drying and storage on the stability of bayberry polyphenols. Food Chemistry, 129(3), 1139–1147. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.05.093

- Fazaeli, M., Emam-Djomeh, Z., Ashtari, A.K., & Omid, M. (2012). Effect of spray drying conditions and feed composition on the physical properties of black mulberry juice powder. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 90(4), 667–675. doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2012.04.006

- Frascareli, E., Silva, V., Tonon, R., & Hubinger, M. (2012). Effect of process conditions on the microencapsulation of coffee oil by spray drying. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 90(3), 413–424. doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2011.12.002

- Goreja, W. (2003). Black seed: Nature’s miracle remedy. Basel: Karger Publishers.

- Grabowski, J., Truong, V.-D., & Daubert, C. (2008). Nutritional and rheological characterization of spray dried sweetpotato powder. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 41(2), 206–216. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2007.02.019

- Hannan, A., Saleem, S., Chaudhary, S., Barkaat, M., & Arshad, M.U. (2008). Anti bacterial activity of Nigella sativa against clinical isolates of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Ayub Medical Colegel Abbottabad, 20(3), 72–74.

- Janfaza, S., & Janfaza, E. (2012). The study of pharmacologic and medicinal valuation of thymoquinone of oil of Nigella sativa in the treatment of diseases. Annals Biological Research, 3, 1953–1957.

- Karthikeyan, R., & Balasubramanian, V. (2010). Predictions of the optimized friction stir spot welding process parameters for joining AA2024 aluminum alloy using RSM. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 51(1–4), 173–183. doi:10.1007/s00170-010-2618-2

- Kealaher, E., Speight, L., Stone, M., Lau, D., Ketchell, R., & Duckers, J. (2015). 202 Bone mineral density and fractures at the All Wales Adult CF Centre (AWACFC). Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, 14, S110. doi:10.1016/S1569-1993(15)30379-9

- Khattak, K.F., & Simpson, T.J. (2008). Effect of gamma irradiation on the extraction yield, total phenolic content and free radical-scavenging activity of Nigella staiva seed. Food Chemistry, 110(4), 967–972. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.03.003

- Kiralan, M. (2012). Volatile compounds of black cumin seeds (Nigella sativa L.). From Microwave‐Heating and Conventional Roasting. Journal of Food Science, 77(4), C481–C484.

- Koocheki, A., Taherian, A.R., Razavi, S.M., & Bostan, A. (2009). Response surface methodology for optimization of extraction yield, viscosity, hue and emulsion stability of mucilage extracted from Lepidium perfoliatum seeds. Food Hydrocolloids, 23(8), 2369–2379. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2009.06.014

- Lee, C. (2000). Antioxidant ability of caffeine and its metabolites based on the study of oxygen radical absorbing capacity and inhibition of LDL peroxidation. Clinica Chimica Acta, 295(1), 141–154. doi:10.1016/S0009-8981(00)00201-1

- Lee, J.Y., & Lin, B.-H. (2013). A study of the demand for convenience food. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 19(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/10454446.2013.739120

- Mishra, P., Mishra, S., & Mahanta, C.L. (2014). Effect of maltodextrin concentration and inlet temperature during spray drying on physicochemical and antioxidant properties of amla (Emblica officinalis) juice powder. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 92(3), 252–258. doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2013.08.003

- Morsi, N.M. (2000). Antimicrobial effect of crude extracts of Nigella sativa on multiple antibiotics-resistant bacteria. Acta Microbiologica Polonica, 49(1), 63–74.

- Murugesan, R., & Orsat, V. (2012). Spray drying for the production of nutraceutical ingredients—A review. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 5(1), 3–14. doi:10.1007/s11947-011-0638-z

- Nonthakaew, A., Matan, N., Aewsiri, T., & Matan, N. (2015). Caffeine in foods and its antimicrobial activity. International Food Research Journal, 22, 1.

- Patel, R., Patel, M., & Suthar, A. (2009). Spray drying technology: An overview. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 2(10), 44–47.

- Patras, A., Brunton, N.P., O’Donnell, C., & Tiwari, B. (2010). Effect of thermal processing on anthocyanin stability in foods; mechanisms and kinetics of degradation. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 21(1), 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2009.07.004

- Pitalua, E., Jimenez, M., Vernon-Carter, E., & Beristain, C. (2010). Antioxidative activity of microcapsules with beetroot juice using gum Arabic as wall material. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 88(2), 253–258. doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2010.01.002

- Quek, S.Y., Chok, N.K., & Swedlund, P. (2007). The physicochemical properties of spray-dried watermelon powders. Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification, 46(5), 386–392. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2006.06.020

- Ramamoorthy, P.K., & Bono, A. (2007). Antioxidant activity, total phenolic and flavonoid content of Morinda citrifolia fruit extracts from various extraction processes. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology, 2(1), 70–80.

- Rannou, C., Queveau, D., Beaumal, V., David-Briand, E., Le Borgne, C., Meynier, A., … Loisel, C. (2015). Effect of spray-drying and storage conditions on the physical and functional properties of standard and n− 3 enriched egg yolk powders. Journal of Food Engineering, 154, 58–68. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.11.002

- Salem, E.M., Yar, T., Bamosa, A.O., Al-Quorain, A., Yasawy, M.I., Alsulaiman, R.M., & Salem, E. (2010). Comparative study of Nigella Sativa and triple therapy in eradication of Helicobacter Pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology, 16(3), 207. doi:10.4103/1319-3767.65201

- Schwartzbach, H. (2010). The possibilities and challenges of spray drying. Pharmceutical Technology Europe, 22, 5–8.

- Shrestha, A.K., Ua-Arak, T., Adhikari, B.P., Howes, T., & Bhandari, B.R. (2007). Glass transition behavior of spray dried orange juice powder measured by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermal mechanical compression test (TMCT). International Journal of Food Properties, 10(3), 661–673. doi:10.1080/10942910601109218

- Singleton, V., & Rossi, J.A. (1965). Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 16(3), 144–158.

- Škerget, M., Kotnik, P., Hadolin, M., Hraš, A.R., Simonič, M., & Knez, Ž. (2005). Phenols, proanthocyanidins, flavones and flavonols in some plant materials and their antioxidant activities. Food Chemistry, 89(2), 191–198. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.02.025

- Speight, J.G. (2015). Mineral Matter. In J. D. Winefordner (Ed.), Handbook of coal analysis (pp. 84–115). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sultan, M.T., Butt, M.S., Anjum, F.M., Jamil, A., Akhtar, S., & Nasir, M. (2009). Nutritional profile of indigenous cultivar of black cumin seeds and antioxidant potential of its fixed and essential oil. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 41(3), 1321–1330.

- Sun-Waterhouse, D., Chen, J., Chuah, C., Wibisono, R., Melton, L.D., Laing, W., … Skinner, M.A. (2009). Kiwifruit-based polyphenols and related antioxidants for functional foods: Kiwifruit extract-enhanced gluten-free bread. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 60(sup7), 251–264. doi:10.1080/09637480903012355

- Tonon, R.V., Brabet, C., & Hubinger, M.D. (2008). Influence of process conditions on the physicochemical properties of açai (Euterpe oleraceae Mart.) powder produced by spray drying. Journal of Food Engineering, 88(3), 411–418. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.02.029

- Umar, S., Zargan, J., Umar, K., Ahmad, S., Katiyar, C.K., & Khan, H.A. (2012). Modulation of the oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine response by thymoquinone in the collagen induced arthritis in Wistar rats. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 197(1), 40–46. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2012.03.003

- Wang, Y., & Blaschek, H.P. (2011). Optimization of butanol production from tropical maize stalk juice by fermentation with Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052. Bioresource Technology, 102(21), 9985–9990. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.08.038

- Watts, B.M., & Watts, B.M. (1989). Basic sensory methods for food evaluation. Canada: International Development Research Centre.

- Xu, X., Gao, Y., Liu, G., Wang, Q., & Zhao, J. (2008). Optimization of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of sea buckthorn (Hippophae thamnoides L.) oil using response surface methodology. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 41(7), 1223–1231. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2007.08.002

Appendix A

NIGELLA SATIVA DRINK EVALUATION

Panellist No.: ________________

Gender: ________________

Date: ________________

INSTRUCTION:

1. You are given several coded samples. Please taste the sample thoroughly and rate its overall palatability on the scale below. You may expectorate the sample if you wish.

2. Please rinse your mouth with plain water before starting. You may rinse again at any time during the test as needed.

3. Each sample was described according to the following scale

1 = Dislike extremely

2 = Dislike very much

3 = Dislike moderately

4 = Dislike slightly

5 = Neither like nor dislike

6 = Like slightly

7 = Like moderately

8 = Like very much

9 = Like extremely

N.B: Scorecard with 9-point hedonic scale used to rate acceptability of N. sativa brew