ABSTRACT

In arguing for alternatives to test-based accountability, researchers have suggested that teacher-assigned student grades could be used for high-stakes purposes. In this study, Sweden serves as an example of a school system in which teacher-assigned grades have a major role in performance management and accountability. We study how politicians view and legitimise the strengths of grading in an outcome-based accountability system. Based on two-part analysis, we show how grades, through complex processes of legitimation, have acquired and retained a central position in governing the overall quality of the educational system in Sweden. We argue that in the Swedish system, grades used in an administrative rather than a pedagogical way function as a quick language that effectively reduces the complexity of communication between various actors with regard to what students learn and accomplish in education. As such, grades are legitimate in terms of their communicative rationality. However, their use in communicating student learning has not been sufficient to meet the needs of government. We conclude that in order to turn grading into an instrument that can moderate some of the downsides of testing regimes, a broader view of what constitute outcomes in education needs to follow.

Introduction

In measuring and governing the quality of education, outcomes in terms of academic achievement have come to play an increasingly important role in recent decades (Hopmann, Citation2003; Sahlberg, Citation2016). In many countries, the policies accompanying this development have relied on an increased use of testing for accountability purposes (Baker, Citation2016; Brookhart, Citation2015; Linn, Citation2000). Sahlberg (Citation2016) included test-based accountability as one of the key features of what he termed a Global Educational Reform Movement, which he argued is currently affecting educational policies around the world.

At the same time, global educational reform and ‘policy borrowing’ are not uniform phenomena, but interact with educational traditions in the respective countries in which they are implemented (Lingard, Citation2010; Schriewer, Citation1988). Taking the examples of England, Germany and Sweden, Waldow (Citation2014) argued that these three countries represent three different educational traditions in relation to how their examination and assessment systems are governed. England has had a long tradition of governing through external exams, of what Hopmann (Citation2003) has called ‘product control’, and of focusing on monitoring outcomes while leaving many other aspects of the educational system unregulated. The German tradition is characterised by what Waldow calls ‘process control’, which entails regulating education through detailed curricula and regulated teacher education while leaving the outcomes of education almost entirely in the hands of the teachers, while Sweden can be seen as a mixture of these two types of systems (Waldow, Citation2014). However, in relation to product control and compared to England, the Swedish system has relied heavily on teacher-assigned grades for high-stakes purposes, such as graduation and selection. We argue that Sweden is an interesting – almost unique – example of an educational system in which outcome-based accountability has been accomplished by using teacher-assigned grades.

The use of graded achievement in outcome-based accountability systems has not attracted much attention in research; instead, the focus has been on test-based accountability and its effects (e.g. Au, Citation2011; Baker, Citation2016; Dee & Jacob, Citation2011; Harlen & Deakin Crick, Citation2002). The downsides of test-based accountability systems have led researchers to argue for alternatives. Harris and Herrington (Citation2006) argued that there is a need to refocus, shifting from the efficiency doctrine of testing regimes such as No Child Left Behind, back to the resource and content focus of the preceding policies. Such policies have recently been implemented in the US (e.g., Darling-Hammond, Wilhoit, & Pittenger, Citation2014).

In arguing for alternatives to test-based accountability, researchers have suggested that teacher-assigned student grades could be used for high-stakes purposes in order to moderate negative effects of testing (Brookhart et al., Citation2016; Willingham, Pollack, & Lewis, Citation2002). For a long time, teacher-assigned grades have been considered too unreliable to be used for high-stakes or administrative purposes (Brookhart, Citation2015; Brookhart et al., Citation2016). However, this conclusion has been questioned in the last decade, as it has been shown that graded achievement is not a measure of the same construct as tested achievement (Brookhart, Citation2015). Instead, graded and tested achievements must be seen as complementary measures, and they can thus possibly serve complementary functions in governing and measuring the quality of education (Brookhart, Citation2015; Brookhart et al., Citation2016; Südkamp, Kaiser, & Möller, Citation2012). For example, grades seem to better predict future success in education, and to some extent measure conative skills – such as student interest, volition, and self-regulation (Brookhart, Citation2015; Brookhart et al., Citation2016). At the same time, some researchers have argued that the differences between grades and tests are to be found in high-stakes and low-stakes uses, where the objectivity of tests lends them to high-stakes/administrative purposes, while teacher-assigned grades have their strengths when used internally for pedagogical purposes, as a contract between students and teachers (Willingham et al., Citation2002).

In Sweden, grades have for more than half a century been used for high-stakes purposes. It was during the era of extensive educational reform in Europe in the post-war period that Sweden developed a national grading system for primary and secondary education that would make the previous reliance on entrance and exit exams obsolete, thus putting Sweden on a different track compared to school systems in which external exams are still means of graduation and selection, such as England or America.

The post-war grading system that was developed in Sweden was based on teacher-assigned grades that were standardised through use of national tests in selected subjects (Lundahl, Citation2006, Citation2008). However, in the 1980s, severe criticisms were made of this grading system, with the main one being that it was not designed to govern the outcomes of education (Lundahl, Citation2006). An expert commission suggested abandoning grading in favour of national tests (Ds 1990:60), but instead of abandoning grading, the grading system was redesigned in order to make it a tool for outcome-based accountability. We argue that Sweden can serve as an internationally interesting example of a school system in which teacher-assigned grades have a major role in performance management and accountability, which means that teacher-assigned grades in Sweden have come to have predominantly high-stakes/administrative functions, rather than pedagogical ones. We are interested in how politicians view and legitimise the strengths of grading in an outcome-based accountability system, not least from a ‘policy-borrowing’ perspective, as Sweden has a unique way of using grading when compared to other countries.

Analysing two Swedish grading reforms

Based on two-part analysis, we will show how teacher-assigned grades, through complex processes of legitimation, have acquired and retained a central position in governing the overall quality of the educational system in Sweden. The first part of our analysis focuses on the revision of the grading system in the early 1990s, which was part of a major reform of the Swedish school system in order to improve the outcomes of schooling. The grading system was redesigned and new functions for governing educational quality were developed: a grading system that could give an indication of the outcomes of schooling and also govern the quality of schooling by means of accountability was designed (Lundahl, Erixon Arreman, Holm, & Lundström, Citation2013).

In the second part of our analysis, we study the system almost two decades after its initial construction. Also in this analysis, we focus on a grading reform (launched in 2011). The quality of the Swedish school system was again considered to be too poor, and the grading system was considered a key part of improving educational quality.

The two parts of our analysis reveal differences in how a grading system that could serve outcome-based accountability was legitimised: in the first reform, the main legitimising processes concerned the core principles, and the work to find a grading system that could be broadly accepted among stakeholders. In the second reform, we observed a new strategy in achieving legitimacy for a grading system by reference to other countries’ grading systems (‘policy borrowing’). More generally, Ringarp and Waldow (Citation2016) noted a shift in educational policy in Sweden around 2007, when the international argument became prominent. The two studies inform what policy-makers see as important aspects of a grading system in developing it as a governing instrument of educational outcomes.

Our methodological approach is to systematically follow arguments concerning the use of grades in relevant committee work, Swedish government official reports and propositions. In this paper we will not give a full account of the arguments, but will focus on key legitimising strategies in the two respective reforms described above. To examine how the European and global arguments were put forward in the Swedish policy documents following the 2011 reform processes, we have analysed the complexity of European countries’ grading and accountability systems as represented in Eurydice,Footnote1 which was a principal source for the government’s legitimation of the grading reform.

Eurydice holds the most accessible knowledge regarding educational systems in Europe. This database is a searchable online platform, developed by the European Commission’s Education, Audiovisual, and Culture Executive Agency (Eurydice, Citation2016).Footnote2 There are substantial validity problems related to the construction and use of data intended to facilitate such comparisons of educational systems. Knowledge is geographical, sociological and chronological (Burke, Citation2012). In other words, we can expect editors of an encyclopaedia such as Eurydice to struggle with geographical and periodical frames, translations and issues of deciding on the relevance and limitations of content and of contributors. In a larger study of the construction and use of Eurydice data (Tveit & Lundahl, Citationsubmitted) we systematically reviewed all countries’ descriptions of their approaches to assessment.Footnote3 Thereby, we identified variations with respect to matters such as school structure, grading scales, and students’ age when they receive formal grades and certificates, as described in Eurydice. In this paper, we have focused on the various types of grading scales that we could identify in the Eurydice database, and supplemented the Eurydice data with other sources to substantiate the various forms grading takes in different countries. Thereby, we juxtapose different ways of organising grading in school, and the use of grades as tools of accountability in different countries, to illustrate how referring to or borrowing from other countries often neglects idiosyncratic national contexts.

Theoretical perspectives on grading systems and policy making

The use of numbers or other simple performance measures to describe school quality and development can be viewed as a type of independent language about schooling. In an attempt to understand the need for performance measurements and statistics in schools, Lundahl (Citation2008) introduced the concept of a ‘quick language’ – a way to reduce complexity by creating a common language, enabling a smooth transfer of information in the field of education. A quick language connects various actors who may otherwise find it difficult to communicate with one another. A quick language can be based on various types of information, but is characterised by some form of quantification or abstraction. During 1920–1930, this quick language involved, for instance, the emergence of medical and psychological terminology in the organisation of schooling. In 1940–1960, intelligence measurements and statistical methods (i.e. psychological factor analyses) became central to the conversation about schooling, while during the 1970s and 1980s, sociological theory and sociological correlation analyses began to emerge. Finally, in the 1990s, the language terminology shifted to economic and administrative goal attainment analyses (Lundahl, Citation2006).

The development of a quick language resembles what Strang and Meyer (Citation1993) called the ‘theorisation’ of social concepts and practices: the ‘self-conscious development and specification of abstract categories and the formulation of patterned relationships such as chains of cause and effect’ (Strang & Meyer, Citation1993, p. 492). Theorisation in this sense ‘facilitates communication among strangers by providing a language that does not presume directly shared experience’ (Strang & Meyer, Citation1993, p. 499; see also Lundahl & Waldow, Citation2009).

We perceive a quick language as a way to ‘make sense of the world’. However, the form that a quick language assumes (medical, sociological, economic) represents a choice of possible theorisations. Thus, a quick language tends to be somewhat underdetermined and/or can be interpreted in different ways. This ambiguity actually contributes to its attractiveness, as advocates of different positions can unite behind it. There may, in other words, be many different explanations for declining school results, and different actors may understand these in different ways, but by using the notion that the situation is clearly presented in statistics, they can unite in the battle over educational reforms and educational policies.

A grade, as well as a test result, is quick in its representation (it includes much information), and (therefore) it is quick to use. It flows smoothly between various actors because they do not (think they) need to decode it. It therefore works perfectly well as a boundary object (Star & Griesemer, Citation1989).

However, only reviewing the symbolic use of grades as a quick language is not sufficient if we want to understand how the politics of grading work. Grades are used to legitimise a certain type of policy, but they must also be legitimised themselves. According to Schriewer (Citation1988), the legitimisation of national work for change typically occurs using references to tradition and faith, organisation, science and policies in other countries; so-called ‘policy borrowing’. According to Schriewer (Citation1988), the national references through which educational systems legitimise themselves are under threat during times of rapid social, economic and political change. Policy borrowing then ‘becomes an effective means to radically break with the past through transferring education models, practices, and discourses from other educational systems’ (Silova, Citation2009, p. 299). Or, as Halpin and Troyna (Citation1995, p. 303) argued,

Cross-national policy borrowing rarely has much to do with the success, however defined, of the institutional realisation of particular policies in their countries of origin; rather, it has much more to do with legitimating other related policies.

In our analysis of grades, we assume that they possess, and therefore provide, legitimacy through their perceived effectiveness, abstraction and ability to act as a quick language, but also through special policy work that refers to organisations’ needs and functionality, as well as to policies in other countries.

Part I: legitimising grades as a key accountability measure

Part of the driving force behind the new role of grades and the new grading system in Sweden in the 1990s was an overall change in the governing of the public sector to management by objectives (Nordin, Citation2014; Tarschys & Lemne, Citation2013; Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015). In 1988, the Swedish parliament decided in principle on government management based on objectives and results (in short, management by objectives). This new orientation, which was prompted around the world in terms of public activities, is usually referred to as New Public Management (Hood, Citation1995).

Management by objectives became a basic premise of the new school system that was developed in Sweden in the early 1990s (Tarschys & Lemne, Citation2013). Essential elements of the new school system were formulated in education policy bills (Policy bill 1988/89:4; 1990/91:18). These have argued for a need to ‘find new and more effective ways to develop the school’ (1988/89:4, p. 6) and that it is time to ‘increase the demands on the school system to achieve set goals’ (p. 6). The need for ‘greatly expanded efforts for evaluation’ has also been stressed (Policy bill 1988/89:4, p. 11). All in all, the foundations were laid for an outcome-based accountability system to come. However, nothing was said about the role of tests and grades in such a system. In fact, as stated earlier, an expert committee had suggested abandoning grading altogether in primary and lower secondary school (Ds 1990:60).

In order to understand how grades became a legitimate part of the accountability system that was implemented in Swedish primary and secondary education during the second half of the 1990s, we have to account for the need to find viable political solutions.

The 1980s has been characterised by a status quo in national educational policy, centred around grades. There was a consensus among political parties that the educational system needed to change, but there was no way to find directives that all parties could agree on. This was especially the case regarding the grading system (Gustafsson, Citation1997; Johansson, Citation1997). On the one hand were left-wing parties that wanted to abandon grades; on the other were right-wing parties that wanted to expand the grading system. An important turning point was the 1990 Social Democratic convention, which agreed on promoting a new grading system. This opened up for a joint proposal from left–right to initiate a parliamentary grading committee (Gustafsson, Citation1997; Johansson, Citation1997). With the grading problem being solved, a comprehensive reform of primary and secondary education began. The fact that solving the grading problem paved the way for a comprehensive reform indicates the strong position of grading in the Swedish educational system, and indicates that a solution that did not involve grades was not possible. To find a legitimate political solution for an outcome-based accountability system, grading had to be included as a vital instrument.

The guidelines for an outcome-based school system in Sweden were developed by two different committees in the early 1990s: the Parliamentary Committee on the Grading of School Examinations, which was responsible for developing a new outcome-based grading system; and the National Curriculum Committee, which was responsible for developing a new outcome-based national curriculum. Both submitted their final reports at the end of 1992 (SOU 1992:86, 1992:94). In the second half of the 1990s, the new national curriculum, Lpo 94, and the new grading system were implemented in Swedish schools; the first grades were given to students in year 8 in the fall semester of 1996. Even though the implemented system in some respects differed from the ones proposed in the final reports, the key aspects of the grading system were formulated in the committee work.

Although grading was seen as an important part of the new accountability system, it is interesting to note that grades were initially treated separately to the development of a new national curriculum, thus suggesting that grades and the curriculum were not necessarily linked to each other. However, it became evident early on in the work of the parliamentary committee that such a link was needed. An outcome-based grading system that did not have a clear link to the curriculum did not make sense to the grading committee, and they demanded new directives. New directives were given to both the parliamentary committee and the curriculum committee, which specified the need to coordinate their respective work (Dir. 1990:62; Dir. 1991:53; Dir. 1991:104):

Given that the parliamentary committee must base its proposal of a new criterion-referenced grading system on the curricula, grading issues should be given a comprehensive solution based on the curriculum committee’s standpoint on the curricula’s knowledge concepts and formulation of goals, as well as guidelines and models for course syllabi. (Dir. 1991:53, p. 1, authors’ translation)

The new directives facilitated a tighter link between the grading system and the curriculum in which the outcomes of education were to be formulated. However, this required a grading system that was perceived as legitimate by both left- and right-wing representatives in the parliamentary committee. As the first chair of the grading committee recalled, of the eight politicians in the committee, four were against grading, two were in favour, and two had a more pragmatic take (Gustafsson, Citation1997). The pass level came to be an important aspect of a grading system that everybody could accept.

Accountability and the pass level

The importance of a pass level in an outcome-based school system had already been stressed in the first directives to the parliamentary committee: ‘Especially important is the definition of a pass level’ (Persson, Dir. 1990:62, p. 4, authors’ translation). However, the character and function of that pass level was not further elaborated upon in the directives, but evolved in the process of committee work. It became evident that the pass level had strong support from the political members of the committee, both left and right, despite the left being principally against any type of grading. It seems that the pass level came to function as a boundary object in this respect, where left-wing and right-wing representatives could accept the same measure, but for different reasons. Three experts were engaged in the committee work of developing the new grading system, and also working with teachers that tested the ideas in their school practice. Key aspects of the grading system were formulated, and the pass level became the central accountability measure. In the words of Chairman Larz Johansson (Social Democrat),

… grades serve other purposes aside from grading student knowledge; namely, to assess the teachers’ teaching and school results. In reality, all students in compulsory school should receive a passing grade. The school’s responsibility for results includes focusing their efforts particularly on students who fall behind. (Eliasson, Citation1991, pp. 2–3, authors’ translation)

This statement indicates that new political significance had developed for grades; namely, they could serve to evaluate teachers as well as students, and were viewed as a means to support ‘students who fall behind’. The new approach to grading found support even with the Socialist Party representative of the parliamentary committee, Ylva Johansson, who noted that although she would prefer a compulsory school without grades, she could support this type of grading system. She also stressed the importance of not setting the pass limit too low, and of including not only facts but also higher-learning qualities in the requirements, keeping in line with the majority of the parliamentary committee’s council members (Eliasson, Citation1992, p. 5). The new grading system thus met both the left-wing’s demands to support weaker students and the right-wing’s wish to signal, through grades, the requirements to be met.

As an interim conclusion, one might say that the new outcome-based grading system captured an important component of both left- and right-wing ambitions for schooling, which might explain the continued strong endorsement of this system (e.g. the School Commission’s interim report, SOU 2016:38, p. 86). As a result, although tests were still used both to evaluate the quality of the system and as a support for teachers’ grading, the new grading system became the central piece in the new outcome-based accountability system, which was largely legitimised internally via the construction of key principles, such as the pass limit. The picture has changed somewhat in recent years. Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has emerged as a clear performance measure, while the value of grading as a measure of knowledge has been brought into question based on aspects of grade inflation and the comparability of grading across teachers.

Part II: grades as outcomes are challenged: redesigning the grading policy through OECD and European policy data

Following the turn of the millennium and Sweden’s declining performance in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) PISA tests (OECD, Citation2015), we observed a new strategy in achieving legitimacy for the grading system. Whereas the grading scale and policies of the 1990s were largely framed by the national context, the 2011 reform reflected an increased emphasis on, and interest in, other countries’ grading policies. As noted in the former analysis, a new set of grades were introduced both as a means of quality improvement and as an outcome. In the second grading reform in 2011, grades were mainly viewed as means to achieve higher school quality, which was measured primarily through international large-scale assessments.

Among the most prominent changes in the 2011 reform was the requirement that schools should grade students starting in year 6, and the implementation of grades based on clearer assessment standards in the curriculum, which would be used as the basis for teachers’ grading. In the middle of the 2014 election campaign, former Education Minister Jan Björklund proposed further reducing the age for grading to year 4 (when pupils are 9–10 years old) and made the following statement to justify the proposal:

Almost the entire world grade their students earlier than Sweden does. Most countries grade from year 1. Our neighbour country Finland grades students from years 3 or 4. Countries that excel in PISA grade students very early. (SVT, 20 August 2014 [similar to ‘6’o clock news’], authors’ translation)

A basis for this statement was a commission report called A Better School Start that was mandated by the government and included a list of the points at which grades are introduced in 36 countries, including the US and some countries in Asia and South America (PM 2014-08-20, p. 37). Without going into all of the aspects of the reforms, we note that tests were not an important issue in changing the accountability system; instead, changes were directed towards the grading system, and now by reference to other countries. This led to questions of how the grading systems and their effectiveness in an accountability system could be compared. In the next sections, we will consider a selection of comparative aspects of grading systems (in a previous study we have shown that there are no correlations between grading age and PISA results, see Lundahl, Hutlén, Klapp, & Mickwitz, Citation2015). In summary, we will show that the differences in European grading systems in these respects are more striking than the similarities.

Age for grading

Going more into detail, and using information from Eurydice 2015 and 2016, we see that grading systems in European countries vary widely, not only with respect to grading age, but also regarding the type of grading standards and the use of grades as student performance data, which we address below.Footnote4

Some large geographical patterns can be observed. The Nordic countries have, in part due to their coherent comprehensive education systems, a long tradition of ‘late grading’, usually starting in years 6, 7 or 8. In southern Europe, grades play a role, starting in year 1, in determining whether the student moves up a class; in Germany and Austria, grades in years 4 and 6 play a role in deciding what high school programme students are placed in; in Anglo-Saxon countries, grades are clearly subordinate to external examinations in regard to selection criteria. France applies a system whereby students are monitored over specific cycles, with an exam given at the end of each. The results from these exams are summarised in a book (Livret Scolaire), which is used for communication between teachers and parents and for the transition between different school levels in order to give a continuous picture of the child’s progress (Lundahl, Hultén, & Tveit, Citation2017). In other words, it is more common to start formal grading earlier than in Nordic countries, but for various reasons, and often by using a grading scale that has been adapted to better suit grading of young children.

Grading scales

The six-level Swedish grading scale introduced in 2011/2012 was modelled on Denmark’s new grading scale (Ds 2008:13; Prop. 2008/09:87), which in turn was designed based on the so-called European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) scale. ECTS was designed within the framework of the Erasmus Programme to be applied to higher education. The ECTS scale was originally six-level and relative, but in Denmark and Sweden, it has become goal- and criterion-related. The purpose of implementing this grading scale was to have a scale that is more in harmony with the rest of Europe, but it was also believed that more grading levels would motivate students to study harder and that a finer-grained grading system would serve better as a tool for accountability (Ds 2008:13, Policy bill 2008/09:87). It is therefore interesting to see how other countries have designed their grading scales, and the various reasons for offering more or fewer grading levels. As it turns out, the variation is quite large, as shown in .

Table 1. Number of grading levels as reported in Eurydice.Footnote5

Among the countries reported, we see that five grading levels is the most common (eight countries), while six countries have a six-level scale. However, we must be cautious in classifying the data, since some countries report how many grading levels they have without specifying which grade denotations they use (e.g., Bulgaria and Estonia).

France differs from other countries in Europe, having as many as 20 grading levels. In reality, however, they do not necessarily use all levels:

Marking, which is generally used at all levels, is also a personal affair even though the tendency in France, where the marking scheme is from 0 to 20, is to award marks in the medium range rather than to use extremes. A very good piece of work will rarely be rated 18 or 20; more likely 14 or 15. (Bonnet, Citation1997, p. 296)

In , the countries are classified based on the number of grading levels above the breakpoint at which students fail, but this is slightly misleading because some countries have several levels of failure. Denmark has a 00 limit for fail, but students can also receive as low as a −3, a stronger failing grade. Latvia is another example of a country with a grading scale that looks completely different. According to Eurydice, they have four levels of failing grades: 4 (almost satisfactory), 3 (weak), 2 (very weak), 1 (very, very weak). Intriguingly, the Netherlands, at secondary education (not identified in the Eurydice study), has as many as five levels of failing grades (Van Rijn, Béguin, & Verstralen, Citation2012, p. 124).

An important aspect of the number of grading levels raised in an OECD (Citation2012) report concerns the proportion of students who do not achieve a passing grade. The OECD gives no advice as to what the limit for a pass should be, but notes that if the limit only contains one level (as it does in Sweden), and a high proportion of students receive failing grades, consideration should be given to either lowering the limit or developing more failing levels.

Type of grading standards

Another variable is the type of grading standards employed in the curriculum. Swedish grades are clearly distinguishable from those of other European countries in that Sweden determines a standard for several grading levels and does not simply list what students are expected to learn (learning outcomes); this latter approach seems to be the most common (see also Lundahl et al., Citation2017). Even though several other countries specify a standard for what children should learn at certain points in time, the countries’ descriptions in Eurydice contain no evidence of an approach similar to Sweden’s, i.e. specifying outcomes (knowledge requirements) for three grading levels. Within outcome-based education systems, we also see that teachers are given various degrees of autonomy in their assessment of student knowledge.

Despite large differences across the European countries’ curricula, there are certain international trends, particularly those advocated by the EU and the OECD, that standardise aspects of the countries’ curricula (Adolfsson, Citation2013; Mickwitz, Citation2015; Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015). Most obvious is the introduction of the concept of competence, in the sense of 6–10 key competences that permeate individual subjects and the assessment of those, as well as interdisciplinary themes (Lundahl et al., Citation2017).

Grades and student performance data in quality assurance and accountability

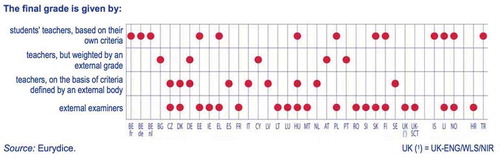

One important motive for the most recent grading reform in Sweden was to introduce a more efficient tool for quality assurance and accountability (Ds 2008:13, Policy bill 2008/09:87). With respect to grading age or the number of grades, we see that there are differences between various countries in terms of how (whether) they use grading as a tool for quality assurance and accountability. While politicians and government reports in Sweden have emphasised the need for more accountability, and try to legitimate these reforms by referring to other countries, they tend to neglect the various qualities of different systems. The European Commission has found that grades can basically be used for quality assurance in four different ways. First, they can govern admittance to the next school level, with a pass being needed for students to avoid retention. Second, they can guide teachers’ lessons and assessments on the basis of criteria provided by an external body. Third, grading can be used as a measure of learning outcomes in official statistics capturing school results and progress. Fourth, grading can be seen as a pedagogical tool in the hands of the teachers; teachers can use grading to encourage students and as a tool for collegial reflections (European Commission, Citation2012, pp. 161–167).Footnote6 Regarding these four ways in which grades can be used in quality assurance, we see, for example, that some countries use a combination of at least two of these four principles, sometimes along with external examinations ().

Regardless of the principles for using grading for accountability and quality assurance that we see in Europe, the last decade has seen a development towards the increased use of student performance in external evaluations (European Commission, Citation2015b, p. 29). Grades as such are not often used for public ranking and national evaluations. Rather, it seems (with some exceptions) that external tests are preferred for these purposes (European Commission, Citation2015a, p. 25).

Whereas 26 countries use both external and internal evaluations of performance data in their quality assurance programmes in quite a homogeneous way (European Commission, Citation2015a, pp. 6–8), there is major difference in how they view accountability. Basically, the line of demarcation is between countries using government-based accountability and those using market-based accountability (Harris & Herrington, Citation2006). The two foundations of market-based accountability systems are access to information and parent/student freedom of choice. Government-based accountability systems are largely based on top-down, pre-defined rules applied to all; in these systems, information on school quality must be accessible primarily to those making decisions about the system.

Different countries thus have different issues at stake in their use of school performance data. We can imagine that those countries using information produced by student performance to hold schools accountable for their outcomes while also providing freedom of choice have the most at stake, leading to grade inflation (Brookhart et al., Citation2016). The Swedish case, in legitimising the use of grades and a finer-grained grading scale as tools for accountability by referring to other countries’ grading and assessment systems, reflects a kind of ‘empty borrowing’ that does not take into account these kinds of contextual conditions. Lowering the formal age for grading in a system with a high degree of market-based accountability, as there is in Sweden, will presumably result in high-stakes grading that is not comparable with many other countries using early grading.

To summarise, when we investigate the differences in European grading systems and how they are used for accountability, the differences between them are more striking than the similarities. Rather than actually trying to learn from the variance abroad, the ‘international’ is treated as one internationality, where, for example, Sweden is compared to the vague notion of ‘other countries’, rather than to specific cultural contexts. In this way, grades are used as boundary objects, which strengthens their position as a quick language; differences in grades as external tools for governing and or data/performance measures are downplayed, while superficial properties are highlighted. As the modification of the Swedish grading system around 2011 was legitimised in relation to other countries’ systems, grading has become a decontextualised means to a seemingly open end (better PISA scores).

Conclusion: the power of grades as a quick language

In this paper we have argued that grades, as assigned to students by their teachers, have been used to legitimise accountability reforms, in different ways and with some poorly explored implications. We have studied two major grading reforms in Sweden: the first aimed at making grades part of an outcome-based accountability system, and the second aimed at making this system more effective in order for Sweden to get a better position in international comparisons. Even though grades, as compared to external tests, have unique potential in an accountability system, when used as a quick language of comparisons and competitions, some of the finer nuances of grading are lost, e.g how they express teacher trust; longitudinal observation of children’s development; and how they reveal the interconnection between curriculum, teaching and evaluation (Bernstein, Citation2000).

We argue that grades used in an administrative rather than a pedagogical way function as a quick language that effectively reduces the complexity in communication between various actors with regard to what students learn and accomplish in education. As such, grades are legitimate in terms of their communicative rationality. However, their use in communicating student learning has not been sufficient to meet the needs of government. In what can be understood as a mutual legitimation process during the 1990s, grades were reshaped to support outcome-based accountability policies in education. It is likely that many teachers preferred being held accountable for their grading, rather than for external testing. At the same time, grades became a simple and quick indicator used in the new accountability system. Since there has traditionally been political reluctance, especially from left-wing politicians, to put too much reliance on grading, it can be perceived as somewhat surprising that the reform of the 1990s was adopted. One reason may be that grades supported different kinds of theorisation regarding the purposes for which grade data should be used. Grades became boundary objects that aligned those who wanted more control with those who were afraid that teachers might lose their autonomy. One key factor here was the change towards a criterion-referenced grading system and a standard set for the ‘pass’ level. Another factor was that clear standards for teachers’ grading were preferred over introducing more external tests (Lundahl, Citation2009).

The Swedish school system differs from that of many other countries in its extensive use of internal assessment instruments, such as grades set by teachers. One reason for this difference is probably the strong tradition in Sweden of viewing the awarding of grades as a power held by teachers to decide the future of the children, and of teachers as being able to do this in a fair way (Lundahl, Citation2006, Citation2009; Lundahl & Waldow, Citation2009). When, in the 2000s, the OECD’s PISA studies became more influential, and education even more internationalised, grading lost its legitimacy as an outcome measure (Ringarp & Waldow, Citation2016). At the same time, it kept its position as an accountability measure. Although it was not seen as providing an accurate measure of the quality of schooling in Sweden, it was regarded as an essential measure to improve this quality.

For researchers who suggest that grades may provide complementary functions as compared to tests, Sweden may serve as an example. However, as we have shown, political beliefs in what a grading system can accomplish, and how, in many respects resemble those of test-based accountability systems; in essence, a pass/proficiency level that is supposed to hold schools and teachers accountable for outcomes, and that is believed to invoke continuous quality development in the work performed by schools and teachers. But as with the test-based systems, there is little evidence that the grading accountability in Sweden has led to improved outcomes; in fact, the outcomes as measured by PISA have declined. Grades may of course serve other functions in an outcome-based accountability system linked to their abilities to predict future success in education, and as a measure of conative skills (Brookhart, Citation2015; Willingham et al., Citation2002). However, these aspects are not the ones highlighted by politicians in discussion of the grading system in Sweden; instead, comparative and competitive aspects have been focused on as if they were the same type of constructs as tests.

Regarding comparative aspects of grading systems, Schriewer (Citation1988) noted that comparison is not about relating observable facts to each other; rather, it is about relating contexts, or even patterns of contexts, to each other (pp. 33–34). A context can, for example, include grading as used in external evaluations, in the classroom as daily feedback, as a means for external motivation or as a disciplinary tool, and can further include the extent to which it affects students’ continued study, careers, etc. To compare countries’ grading policies, it is necessary to gain a wider perspective on these contexts. Then, the difficult task is to compare the different contexts in which grades are included between different countries. For example, it is important to understand grading systems in relation to the curriculum, how transition between different levels in the educational system is organized (and whether, and if so how, grading plays a role), the academic years included in primary and secondary education, and the external exams and/or forms of examination that are available (Lundahl et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Tveit & Lundahl, Citationsubmitted).

Grades may indeed have the potential to complement tests in outcome-based accountability systems, but the present study reveals some severe challenges based on how grades have been used in the Swedish accountability system. To turn grading into an instrument that can moderate some of the down sides of testing regimes, a broader view on what constitutes outcomes in education must follow. In addition, although grades have long been used for high-stakes purposes in Sweden, they have only been high-stakes for students, not for teachers. The outcome-based system has made grading an instrument for holding teachers accountable for student learning. This may negatively affect other potential benefits of grading, such as the contract between students and teachers – i.e. this may negatively affect the pedagogical uses of grades in the everyday classroom (Willingham et al., Citation2002).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

2. Eurydice was originally a network, founded in 1990 by 12 EU member states, with the purpose of exchanging important information. Today, the network includes 42 countries and publishes information from EU member states, as well as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Macedonia, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, and Turkey. The Eurydice database is named after Eurydice, the wife of Orpheus, who was allowed to return from death on the condition that Orpheus did not turn around, which he did. The website slogan is ‘Better knowledge for better education policies’. The Education, Audio-visual, and Culture Executive Agency is commissioned to handle the EU funding programs for education, sports, culture, etc.

3. Called ‘Assessment in Primary/Secondary’ education, or ‘Assessment in Single Structure Education’.

4. We address here the aspects usually used in the Swedish grading debate when seeking legitimate support for changes in the grading system. There are other important differences between countries regarding teacher-assessment autonomy, information conveyed to the home, and examinations and transition. These are not, however, covered here (for more, see Lundahl et al., Citation2017).

5. Source Eurydice 2015. This is based on the grading scales students meet first through the course of schooling, as identified in Eurydice. This should not be taken as an exhaustive report of grading scales, as many countries have either not reported such information properly or, as in several instances, information was lacking. Note that the Eurydice database is updated regularly; thus, the countries’ representation may have changed substantially. See also Lundahl et al. (Citation2017).

References

- Adolfsson, C. H. (2013). Kunskapsfrågan: En läroplansteoretisk studie av den svenska gymnasieskolans reformer mellan 1960-talet och 2010-talet (Doctoral dissertation). Linnaeus University Press.

- Au, W. (2011). Teaching under the new Taylorism: High- stakes testing and the standardization of the 21st century curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(1), 25–45. doi:10.1080/00220272.2010.521261

- Baker, E. (2016). Research to controversy in 10 decades. Educational Researcher, 45(2), 122–133. doi:10.3102/0013189X16639048

- Bernstein, B. B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity: Theory, research, critique (Rev ed.). Oxford, UK: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Bonnet, G. (1997). Country profile from France. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 4(2), 295–306. doi:10.1080/0969594970040206

- Brookhart, S. M. (2015). Graded achievement, tested achievement, and validity. Educational Assessment, 20(4), 268–296. doi:10.1080/10627197.2015.1093928

- Brookhart, S. M., Guskey, T. R., Bowers, A. J., McMillan, J. H., Smith, J. K., Smith, L. F., … Welsh, M. E. (2016). A century of grading research: Meaning and value in the most common educational measure. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 803–848. doi:10.3102/0034654316672069

- Burke, P. (2012). A social history of knowledge II: From the encyclopédie to wikipedia. Cambridge: Polity.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wilhoit, G., & Pittenger, L. (2014). Accountability for college and career readiness: Developing a new paradigm. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 22(86), 1–34.

- Dee, T. S., & Jacob, B. (2011). The impact of no child left behind on student achievement. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 30(3), 418–446. doi:10.1002/pam.20586

- Dir. 1990:62. Kommittédirektiv. Tillkallande av en beredning för att ge förslag till ett nytt betygssystem i grundskolan, gymnasieskolan och den kommunala vuxenutbildningen (Beslut vid regeringssammanträde 1990-10-25). Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Dir. 1991:104. Kommittédirektiv. Tilläggsdirektiv till beredningen (U 1990:07) för att ge förslag till ett nytt betygssystem i grundskolan, gymnasieskolan och den kommunala vuxenutbildningen (dir. 1990:62) (Beslut vid regeringssammanträde 1991-12-05). Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Dir. 1991:53. Kommittédirektiv. Tilläggsdirektiv till beredningen (U 1990:07) för att ge förslag till ett nytt betygssystem i grundskolan, gymnasieskolan och den kommunala vuxenutbildningen (dir. 1990:62) (Beslut vid regeringssammanträde 1991-06-20). Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Ds 1990:60. Betygens effekter på undervisningen (Letter of Ministry of Education and Research).

- Ds 2008:13. En ny betygsskala (Letter of Ministry of Education and Research).

- Eliasson, S. (1991). Minnesanteckningar från sammanträde nr 9 I den parlamentariska beredningen för utredning av betygsfrågor. 1991-10-16 (Riksarkivet, Betygsberedningens arkiv, SE/RA/324219, volume 1).

- Eliasson, S. (1992). Minnesanteckningar från sammanträde nr 21 i den parlamentariska beredningen för utredning av betygsfrågorna. 1992-08-04 (Riksarkivet, Betygsberedningens arkiv, SE/RA/324219, volume 4).

- European Commission. (2012). Key data on education in Europe 2012. Retrieved from http://bookshop.europa.eu/is-bin/INTERSHOP.enfinity/WFS/EU-Bookshop-Site/en_GB/-/EUR/ViewPublication-Start?PublicationKey=ECAF12001

- European Commission. (2015a). European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015 (Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe. Eurydice Report). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from http://bookshop.europa.eu/is-bin/INTERSHOP.enfinity/WFS/EU-Bookshop-Site/en_GB/-/EUR/ViewPublication-Start?PublicationKey=EC0414939

- European Commission. (2015b). Structural indicators for monitoring education and training systems in Europe – 2015. Eurydice background report to the education and training monitor 2015 (Eurydice Report). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/thematic_reports/190EN.pdf

- Eurydice (2016). Network on education policies and systems in Europe. Retrieved from http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/index_en.php

- Gustafsson, L. (1997). Minnen från skilda arenor. In G. Richardsson (Ed.), Spjutspets mot framtiden? Skolministrar, riksdagsmän och SÖ-chefer om skola och skolpolitik (pp. 135–156). Uppsala: Föreningen för svensk undervisningshistoria.

- Halpin, D., & Troyna, B. (1995). The politics of education policy borrowing. Comparative Education, 31(3), 303–310. doi:10.1080/03050069528994

- Harlen, W., & Deakin Crick, R. (2002). A systematic review of the impact of summative assessment and tests on students´ motivation for learning (EPPI-Centre Review, version 1.1*). In Research evidence in educational library (Vol. Issue 1). London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education.

- Harris, D. N., & Herrington, C. D. (2006). Accountability, standards, and the growing achievement gap: Lessons from the past half-century. American Journal of Education, 112(2), 209–238. doi:10.1086/498995

- Hood, C. (1995). The “new public management” in the 1980s: Variations on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(2–3), 93–109. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W

- Hopmann, S. T. (2003). On the evaluation of curriculum reforms. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(4), 459–478. doi:10.1080/00220270305520

- Johansson, L. (1997). Konfrontation eller resultatpolitik? In G. Richardsson (Ed.), Spjutspets mot framtiden? Skolministrar, riksdagsmän och SÖ-chefer om skola och skolpolitik (pp. 177–192). Uppsala: Föreningen för svensk undervisningshistoria.

- Lingard, B. (2010). Policy borrowing, policy learning: Testing times in Australian schooling. Critical Studies in Education, 51(2), 129–147. doi:10.1080/17508481003731026

- Linn, R. L. (2000). Assessments and accountability. Educational Researcher, 29(2), 4–16.

- Lundahl, C. (2006). Viljan att veta vad andra vet. Kunskapsbedömning i tidigmodern, modern och senmodern skola (Doctoral dissertation). Uppsala University.

- Lundahl, C. (2009). Varför nationella prov? Framväxt, dilemman, möjligheter. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lundahl, C., Hultén, M., & Tveit, S. (2017). Betygssystem i internationell belysning. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Lundahl, C., Hutlén, M., Klapp, A., & Mickwitz, L. (2015). Betygens geografi – forskning om betyg och summativa bedömningar i Sverige och internationellt (Delrapport från skolforsk-projektet. Vetenskapsrådet). Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet.

- Lundahl, C. (2008). Inter/national assessments as national curriculum: The case of Sweden. In M. Lawn (Ed.), An atlantic crossing? The work of the international examination inquiry, its researchers, methods and influence (pp. 157–180). Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Lundahl, C., & Waldow, F. (2009). Standardisation and ”quick languages”: The shape-shifting of standardised measurement of pupil achievement in Sweden and Germany. Journal of Comparative Education, 45(3), 365–385. doi:10.1080/03050060903184940

- Lundahl, L., Erixon Arreman, I., Holm, A.-S., & Lundström, U. (2013). Educational marketization the Swedish way. Education Inquiry, 4(3), 497–517. doi:10.3402/edui.v4i3.22620

- Mickwitz, L. (2015). En reformerad lärare: Konstruktionen av en professionell och betygssättande lärare i skolpolitik och skolpraktik (Doctoral dissertation). Institutionen för pedagogik och didaktik, Stockholms universitet.

- Nordin, A. (2014). Crisis as a discursive legitimation strategy in educational reforms: A critical policy analysis. Education Inquiry, 5(1), 109–126. doi:10.3402/edui.v5.24047

- OECD. (2012). Grade expectations: How marks and education policies shape students’ ambitions. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- OECD. (2015). Improving Schools in Sweden. An OECD Perspective. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/school/Improving-Schools-in-Sweden.pdf

- PM 2014-08-20 (2014). U2014/4873/S En bättre skolstart för alla: Bedömning och betyg för progression i lärandet. Stockholm: Ministry of Education and Research in Sweden.

- Policy bill 1988/89:4. Om skolans utveckling och styrning. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Policy bill 1990/91:18. Om ansvaret för skolan. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Policy bill 2008/09:87. Tydligare mål och kunskapskrav – nya läroplaner för skolan. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet

- Ringarp, J., & Waldow, F. (2016). From‘silent borrowing’ to the international argument – legitimating Swedish educational policy from 1945 to the present day. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2(1), 1–4.

- Sahlberg, P. (2016). The global educational reform movement and its impact on schooling. In K. Mundy, A. Green, B. Lingard, & A. Verger (Eds.), The Handbook of Global Education Policy (pp. 128–144). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Schriewer, J. (1988). The method of comparison and the need for externalization: Methodological criteria and sociological concepts. In J. Schriewer & B. Holmes (Eds.), Theories and methods in comparative education. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Silova, I. (2009). Varieties of educational transformation: The post-socialist states of central/Southeastern Europe and the former soviet union. In R. Cowen & A. M. Kazamias (Eds.), International handbook of comparative education (pp. 295–320). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Star, S., & Griesemer, J. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. doi:10.1177/030631289019003001

- Strang, D., & Meyer, J. W. (1993). Institutional conditions for diffusion. Theory and Society, 22(4), 487–511. doi:10.1007/BF00993595

- Südkamp, A., Kaiser, J., & Möller, J. (2012). Accuracy of teachers’ judgments of students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 743–762. doi:10.1037/a0027627

- Swedish Government Official Reports. (1992a). SOU 1992:86. In Ett nytt betygssystem: Slutbetänkande av Betygsberedningen. Stockholm: Allmänna förlaget.

- Swedish Government Official Reports. (1992b). SOU 1992:94. In Skola för bildning: Huvudbetänkande av Läroplanskommittén. Stockholm: Allmänna förlaget

- Swedish Government Official Reports. (2016). SOU 2016:38. In Samling för skolan. Nationella målsättningar och utvecklingsområden för kunskap och likvärdighet. Delbetänkande från Skolkommissionen.Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Tarschys, D., & Lemne, M. (Eds.). (2013). Vad staten vill: Mål och ambitioner i svensk politik. Mörklinta: Gidlunds.

- Tveit, S., & Lundahl, C. (submitted). New modes of policy legitimation in education: (Mis)using comparative data to effectuate assessment reform. European Educational Research Journal.

- Van Rijn, P. W., Béguin, A. A., & Verstralen, H. H. F. M. (2012). Educational measurement issues and implications of high stakes decision making in final examinations in secondary education. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 19(1), 117–136. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2011.591289

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2015). Theory-based evaluation of the curriculum Lgr 11. Uppsala: Institute for Evaluation of Labor Market and Education Policy (IFAU).

- Waldow, F. (2014). Conceptions of justice in the examination systems of England, Germany, and Sweden: A look at safeguards of fair procedure and possibilities of appeal. Comparative Education Review, 58(2), 322–343. doi:10.1086/674781

- Willingham, W. W., Pollack, J. M., & Lewis, C. (2002). Grades and test scores: Accounting for observed differences. Journal of Educational Measurement, 39(1), 1–37. doi:10.1111/jedm.2002.39.issue-1