ABSTRACT

Two separate data searches underlie this analysis of how references to educational research and to PISA are used in the Swedish education debate. The data consist of 380 newspaper articles from the eight largest print media outlets in Sweden and 200 protocols from parliamentary debates (2000 to 2016) that made explicit reference to ‘PISA’ and/or to ‘educational research’. Based on a content analysis of this material, in which notions of policy borrowing and de-/legitimization are central, we describe the result as a selective use of PISA data and of educational research in the education debate. PISA is used to legitimize selective (party political) solutions that are oriented towards problems of teaching. The analysis also shows that politics and the media debate concerning education seems disinterested in educational research in a broader sense and that PISA seems to offer sufficient and ‘neutral’ authoritative knowledge and support for policy and reforms. We argue that PISA is the first way to obtain legitimate support for educational reforms. In so doing, the kinds of problems that these reforms aim to solve have been narrowed down to teaching- or practice-oriented problems.

Introduction

Almost 20 years since its inception in 2000, OECD PISA (the Programme for International Student Assessment) has become a globally known and well-studied phenomenon. This paper contributes to that area of research by studying the use of PISA as an argument for edu-political ends in comparison to the use of another source of knowledge: educational research. A number of researchers have shown interest in the predominance of PISA in the public debate on educational and national polices. This interest spans reliability issues (Kreiner, Citation2011), discrepancies between national curricula and definitions of PISA literacy (Nardi, Citation2008), and an overall simplified interpretation of results (Kamens, Citation2013; Serder & Ideland, Citation2016). Several policy studies have shown interest in the governing effects of PISA, emphasizing, for example, aspects of measurement as a ‘governmental technology’ (e.g., Carvalho, Citation2012; Grek, Citation2009), or what has been called ‘governing by numbers’ (Gorur, Citation2014, Citation2015; Grek, Citation2009) and governing by comparison (Kamens, Citation2013; Martens, Citation2007). Together, these studies show that PISA has become a very important educational and political tool for organizing education and justifying action (Bieber & Martens, Citation2011; Breakspear, Citation2012; Hultqvist et al., Citation2018; Pettersson et al., Citation2017; Ringarp & Waldow, Citation2016; Sellar & Lingard, Citation2013; Waldow, Citation2017). Recent studies have also pointed at the extent to which the general public is actually affected by PISA results (Pizmony-Levy, Citation2017; Pizmony-Levy & Bjorklund, Citation2018). Pizmony-Levy & Bjorklund, Citation2018 (p. 251), drew on survey data from 30 countries and found ‘evidence that national performance on PISA has a significant positive relationship to public confidence in education’. PISA seems to offer an image of education that is reliable, publicly shared and politically very useful. It operates in a context where educational performance data have become the most legitimate form of ‘evidence’ for politicians and policymakers (Wiseman, Citation2010). Sellar (Citation2015) argued that this is also true ‘for the broader public because of the attention given to performance comparisons and league tables in media reporting on education’ (p. 132). This also means that PISA is intertwined with the ‘frenetic nature of the education debate’ (Ball, Citation2016, preface), in which – to quote Matilda Wiklund in her study of the media debate on Swedish teacher education – the ‘force of international tests dichotomises education into an either-or situation of success or failure’ (Wiklund, Citation2018, p. 129).

Many of the above-mentioned studies have looked at PISA and the public discourse on education through newspaper articles, policy documents and other reports, but surprisingly few have investigated who actually uses references to PISA, and how the use of PISA in public debate and in politics relates to uses of other authoritative references to the state of education, such as references to educational research. The purpose of this paper is to scrutinize the legitimization of educational politics based on different ‘authoritative references’, such as references to instances that, in a ‘trustworthy’ way, claim valid knowledge on education. Such ‘trustworthiness’ can often be linked to structures like culture, time, space, objectivity and predictability (Schriewer, Citation1990).

With inspiration from Weingart (Citation1999) and his study of the historical processes of the scientification of politics and the politicization of science since the Second World War, the present study more precisely aims to understand the position of research in the contemporary education debate, in the era of international large-scale studies. Here we will focus on the educational debate as it takes forms in Swedish media and in the Swedish parliament. This debate often concerns the ‘quality’ of Swedish education and ‘necessary’ reforms in order to ‘improve’ it.

Weingart et al. (Citation2000), who investigated discourses on climate change, argued that the discourse around a specific issue differs in terms of what they refer to as the spheres of science, politics and public (mass media). They also argued that information does not pass unchanged between these different discursive spheres; rather each sphere has different rationalities and ways of using, and not using, information. In the present paper, we explore how PISA and educational research have been used in two different discursive spheres of the Swedish education debate – the media and politics – by asking the following questions: How and when are references to PISA and to educational research made in the Swedish education debate? What actors are involved in the education debate and do different actors use references in different ways?

Sweden is of interest for at least two reasons. Firstly, the decline in PISA results between 2003 and 2012 sent Sweden into so-called ‘PISA shock’, which we also recognize from other countries with poor trends (such as Norway [Haugsbakk, Citation2013] and Germany [Waldow, Citation2009a]). Secondly, this ‘shock’ can lead to a ‘politics of crisis’ and a sense of urgency for education policy (Steiner-Khamsi et al., Citation2018). Together, these factors are believed to have produced the relatively high normative impact of PISA on Swedish education policy (Breakspear, Citation2012). Finally, the access to searchable media articles and parliamentary protocols makes it possible to explore the case of Sweden.

We argue that PISA has become the way of obtaining legitimate support for educational reforms. In so doing, the kinds of problems that these reforms aim to solve have been narrowed down to teaching or practice-oriented problems. This also changes the landscape for the educational research from which practice-based, evidence-based, or subject didactic research is now asked for, rather than, for example, structural or theoretical approaches.

A solution that seeks a problem – selective data use in the politics of education

The education debate under study here has its context in the parliamentary situation in Sweden, where the Social Democrat Party was in government from 1996–2006, then again from 2014, in coalition with the Green Party (Miljöpartiet). The government between these two periods was a coalition between liberals and conservatives (Folkpartiet, Centerpartiet, Kristdemokraterna and Moderaterna). In general terms, Sweden’s PISA results in mathematics, reading and science declined from 2000 to 2012, from average/above average to below average. In PISA 2015, the results for all subject areas were back at the OECD average. Although, as this paper will show, PISA has increasingly turned the attention towards education in the Swedish media coverage during the last two decades, the media focus on education has a longer history (Hultén, Citation2019). In recent years, studies by Wiklund (Citation2018) and Edling and Liljestrand (Citation2019) have shed light on the nature of the Swedish education debate. Both of these studies have focussed on how teacher education (TE) has been discussed.

Wiklund (Citation2018) compared the dominant media discourses on education around the electoral years 1998 and 2014, and observed ‘stronger versions of the dominant discourses in 2014, in comparison to 1998’ (p. 121). Wiklund argued that this ‘indicate[s] how the sets of ideas, which produce and legitimise certain taken for granted truths about education and teachers are moulding into set signifier systems’. According to Wiklund, the Swedish media discourse on education in 2014 seems to only have two possible education policy positions, meaning that, in ‘the editorial media texts, and the forum discussions and blogs connected to them, education policy is constructed as though it was about “cheering on” one or the other team in an ongoing game or battle.’ (Wiklund, Citation2018, pp. 128 − 129).

Also, Edling and Liljestrand’s study (Edling & Liljestrand, Citation2019) reports on a heated Swedish education debate during the years studied (2016 and 2017) and reveals a mistrust in TE and ‘the people labelled as pedagogues’ (p. 17) in a media debate that is ‘primarily fuelled by those outside the field of educational research’ (p. 1).

In both the media and in the Swedish Parliament, the education debate has focused on the call for reforms. A key concept for understanding education policy reforms in recent decades has been the concept of ‘policy borrowing and lending’ (e.g., Steiner-Khamsi & Waldow, Citation2012). Similar to diffusion studies, ‘research on policy borrowing and lending investigates how policies from one domain or one sub-system (education sector, health sector, economic sector, etc.) are transferred to another, or how they are transplanted from one system or country to another’ (Steiner-Khamsi, Citation2012, p. 7).

In comparative education research policy, borrowing recently gained a more general meaning related to how countries’ policies are influenced by other countries’ policies. A central aspect of policy borrowing is how a country can legitimize (that is, justify) its policy changes by making selective references to other countries’ policies (Andersen, Citation2009). This is usually called externalization. Another common form of externalization in education policy is references to science, organization, or history (Schriewer, Citation1990). As Schriewer and Martinez (Citation2004) pointed out, who and what a policy refers to may change over time but it is often about seeking legitimacy for (political) changes by referring to other countries or international organizations. Referring, or externalizing to what it looks like in other countries, or to what research or PISA says, are examples of potentially effective ways of justifying a new reform. For example, Lundahl et al. (Citation2015) showed that Swedish politicians identified the Finnish grading system as the cause of Finland’s PISA success and as something that Sweden needed to replicate. Thus, Finland’s PISA results, combined with its early grading system, were selectively used to argue for and to legitimize early grading in Sweden. In that specific case, this means that PISA could be used as an authoritative reference without either PISA or educational research actually providing evidence for this kind of reform. When selectively choosing a solution with references to an authoritative source, it is often a solution that has been previously suggested in the debate but without finding legitimacy. In the case of the Swedish grading system, Finland’s high scores on PISA helped to legitimize the changes that conservative politicians had argued for, for at least three decades (Tveit & Lundahl, Citation2018). In other words, for this kind of externalization we can then talk of an established solution that seeks a new problem.

The strategy of externalizing in order to gain legitimacy is not new and we can expect it from various political positions, as was the case when the Social democrats in Sweden legitimized comprehensive school during the 1930 and 1940s using vague references to science (e.g., Lundgren, Citation2017). Of specific interest in this paper is the selectiveness in using PISA and educational research as authoritative references when seeking legitimacy for reforms. This means that the research questions stated previously investigate how externalizations are done to different kinds of authoritative sources. There are many different kinds of ‘authoritative truths’ – personal beliefs, ideological convictions, scientific facts and so on – and they can be referred to with different success in different social spheres (cf. Schriewer, Citation1990). As Weingart et al. (Citation2000, p. 263) argued, any issue of interest in the political sphere ‘must be framed as a problem that can be solved by political decision making’. In that sense, scientific uncertainties are problematic because they do not encourage political action. Finally, as shown by Franklin (Citation2004) and further developed by Wiklund (Citation2018), for instance, the media construction of emergency is a necessary aspect of political reform.

Methodology

In order to understand the use of educational research in relation to PISA results in the Swedish education debate, we designed a study based on two data searches: one media search covering the eight largest Swedish newspapers and one covering protocols from parliament debates. Thus, we have demarcated this analysis of the education debate from many other possible sources, such as social media and television and radio broadcasts. Nevertheless, we assume that these data materials expose many of the actors of the education debate and enable us to conduct a content analysis to indicate what topics are dealt with in the debate, by whom and how.

In broad terms, the data searches were followed by data reduction and a content analysis (Cohen et al., Citation2007, p. 466ff), which we used as a point of departure for a further analysis and looked in particular at who said what about PISA or educational research and in relation to which topics. The basic principle in the content analyses was to find statements in which PISA and/or educational research was used as a reference in an argumentation for a reform or a solution to a problem – or, in other words, when PISA or educational research was used as an externalization in an argumentation for an educational problem or solution, as an argumentation for or against a political reform or cause for change. Each kind of reference was classified, using NVivo 11 to track a record (figures and tables below), based on what description of a problem, political reform or solution it was used to support (Schreier, Citation2012).

Data searches and data reduction

The results build on systematic searches in two Swedish databases: Retriever MediaarkivetFootnote1 and the Swedish Parliament’s open database (Riksdagens öppna dataFootnote2). Due to the specific qualities of the two databases, the two search procedures have not been entirely identical.

The media search aimed to find all published and digitalizedFootnote3 education-related articles from 2000 to 2016 that made reference to both PISA and research. The search was limited to articles in which research (forskning) was mentioned, combined with mentioning PISA. This search included all references to research (not only educational research). The term ‘school-’ (skol*) was used to systematically exclude articles on other ‘Pisas’ (such as tourist guides for the town of Pisa). From the resulting 8619 articles, we constrained the analysis to the eight main sources of print Swedish press (Dagens nyheter, Svenska dagbladet, Göteborgsposten, Aftonbladet, Expressen, Kvällsposten, Metro and Sydsvenska dagbladet) (n = 695). Finally, the sample was reduced by excluding articles in which PISA was only mentioned without being emphasized (this included recipes, book reviews, etc.). The remaining articles were classified as either using PISA to debate education (n = 226) or as actually describing/analysing PISA (n = 154). The conducted analyses are based on these 380 articles.

At the time of the searches, the Swedish Riksdag’s open database consisted of approximately 300,000 documents and information dating back as far as 1971.Footnote4 This includes documents (committee reports, private members’ motions, laws), results of votes and members’ speeches in the parliament. Parliamentary debates are transcribed in parliamentary protocols, which are searchable based on topics. For example, it is possible to search for instances when the words ‘research’ and ‘education’ appear within 50 words of each other. In this manner, we could delimit the search to ensure that hits on research most often actually concerned education.

According to the search engine at the Swedish Parliament’s database, the term ‘PISA’ was used in 176 parliamentary debates in Sweden between 2001 and 2017. However, only 151 of these instances were actually about OECD’s PISA. PISA may occur more than once in a given debate. During the same time span, the term ‘educational research’ [pedagogisk forskning] is mentioned in only 27 different parliamentary protocols.Footnote5

Analysis

For the two data sets, we were interested in identifying two types of patterns: key topics and arguments. For each search result (media and parliament), we noted the distribution of articles/protocols over time, in order to determine the intensity of the debate. Next, to analyse the media articles and the parliamentary protocols with respect to their content, we classified the texts based on the content of their main arguments. Here, we systematically sought to distinguish how referring to PISA or educational research was used to argue for and against specific solutions, reforms or causes.

The media analysis was further guided by the principles suggested in Waldow’s (Citation2017) media analysis, looking at the degree to which (1) PISA and (2) educational research were used in a (a) primarily positive or (b) negative (or seemingly falsifying) way or in a (c) neutral or ambivalent way.Footnote6 The actors (researchers, politicians, and journalists, the public and political parties) involved in each mention were noted.

Finally, we attempted to discern whether references to PISA or educational research was used mainly in an externalizing (that is, legitimizing or delegitimising) way, or whether the source making the references actually claimed to have learned something from PISA or educational research.

Results

PISA is central in Swedish education debate. The last PISA report was released on 6 December 2016. During 2017, 3119 texts in Swedish media included the search terms PISA AND school* (Retriever Mediaarkivet). Meanwhile, 784 peer-reviewed papers in educational research [utbildningsvetenskap] were published involving Swedish researchers, along with 21 Swedish doctoral theses in education [pedagogik] (source: diva-portal.org). However, the newsworthiness of these sources (compare Weingart et al., Citation2000) seems to be low: there were only 43 texts in the newspaper press during the same period that include educational research [‘pedagogisk forskning’] AND school*.

The use of PISA in the media debate

The studied topics of the education debate clearly find inspiration in the PISA reports and in the declining Swedish PISA results. However, the analysis suggests that the topics of the debate are also reactions to national media events. Politicians and policy makers, representatives of the teacher unions, teachers and principals appear to act and to react upon the conclusions drawn by several nationwide media events.Footnote7 Examples of how media events have been used in the debate will be presented later in this article.

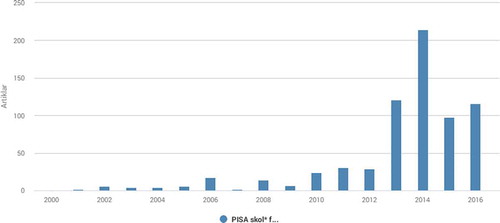

We found an increasing number of articles mentioning both ‘PISA’ and ‘research’ in the Swedish media from 2000 to 2016. The number of articles peaked during 2014 (the Swedish election year) and declined thereafter, but to a proportionately high number (). Interestingly, the same pattern emerged internationally, in very different kinds of media publications. Steiner Khamsi et al. (2018, p. 196) reported that the number of articles in American financial journals that gave attention to PISA also peaked in 2014 and then decreased. For the Swedish case, we believe the reason for the peak in references was the fact that it was an election year, combined with the strong discourse on education crisis (Wiklund, Citation2018), but there may be other reasons as well.

Figure 1. Distribution of articles collected in media search for year 2000 to 2016 (N = 695). Source: Retriever Mediaarkivet

The content analysis provides a picture of what topics that have been mobilized into the education debate, using PISA as argument. Unsurprisingly, the overall picture is that more and more topics were added. The table below () provides the most frequent topics and the number of articles coded in which PISA has been used as argument. It should be noted that the number of topics had multiplied by the time of the General Election in 2014 (eight months after the sensational Swedish PISA 2012 result went public in December 2013).

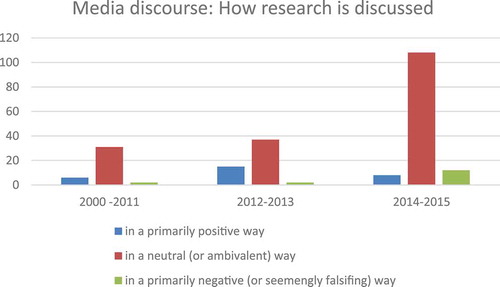

The analysis of whether PISA is discussed in a primarily positive, negative or neutral/ambivalent way (Waldow, Citation2017; see also Hopfenbeck & Görgen, Citation2017) points to questions concerning the legitimacy of PISA as argument for educational reform. Throughout the studied period, PISA appears as a legitimate source of knowledge, but it is also a subject for debate and under negotiation. Around 2010–2011 – perhaps as a consequence of elements in the debate (such as a series of media events) that strengthened the idea of an ongoing ‘school crisis’ in Sweden – an ‘agreement’ seems to have been reached in the debate whereby PISA reached the status of being uncontradictable as an assessment of the Swedish school system. Closer analysis of the political reactions to PISA that emerged in the articles studied shows that, in the political sphere, the status of PISA as a valid source of knowledge has never really been in question. What is open to debate is what PISA is considered to show. As an example, immediately after the publication of the Swedish PISA 2000 results (which were at or moderately above the OECD average at the time), commentators representing the political liberal/conservative parties paid attention to what was described as the disappointing Swedish results with respect to classroom discipline. On the other hand, politically speaking, the governing Social Democrats pointed at the Swedish PISA results to demonstrate that Swedish school was in good condition, even when compared internationally.

Swedish students report loud classes and devote little time for homework. Yet they are doing cognitively well in reading, science and mathematics.

These seemingly paradoxical results appear from the analysis of the OECD’s so called PISA study. As the study was presented in November, commentators from the side of the Social Democrats chose to highlight the virtues of the Swedish school, whereas Conservative commentators gave their attention to poor classroom discipline. (Svenska Dagbladet 8 February 2002)

This political divide with respect to PISA use remained during the years that followed. For the Social Democrats, and the Left, PISA initially proved that Swedish schools (historically most often governed by Social Democrat governments) were doing well. Thereafter, following the decline in PISA (2006, 2009, 2012), PISA – according to the Social Democrats – showed that the right-wing politics resulting from the governmental shift in 2006 to a liberal/conservative government, had been unsuccessful. The rhetoric on schools by Jan Björklund (minister of education from 2006–2014) was repeatedly concerned with the ‘school crisis’ (skolkris).Footnote8 For the right-wing parties and commentators, PISA, as a legitimate and unquestionable knowledge source, showed that school was in crisis and needed to be fixed.

The use of educational research in the media debate

The empirical material indicates that the legitimacy of educational research as a knowledge source for politicians differs among political ideologies or orientations. Whereas Social Democrats often use educational research as a reference (in debate articles, for instance), this is not the case for conservative/liberal commentators. The trust/distrust in the National Agency for Education (Skolverket), and its reports, also varies among political commentators along this line of divide, with liberals/conservatives openly showing distrust. An extreme example is a comment by the prime minister at the time, Fredrik Reinfeldt, on a research report from Skolverket concerning increasing variance between schools in Sweden, which concluded that the free school choice is a possible explanation:

I believe more in the PISA assessment and in international expertise. (Kvällsposten 13 April 2014)

The political divide concerning the legitimacy and usefulness of educational research (‘pedagogisk forskning’) remains. Paradoxically, however, there are also calls in the debate, from all political orientations, for more research to help solve the school crisis. Practice-oriented research (‘praktiknära forskning’) has been advocated as a solution on several occasions.

Understanding the position of research in the debate also involves understanding the position taken or given therein to academic scholars from different disciplines. One striking result is the relative absence of academic scholars in the education debate, at least judging from the eight largest newspapers. In the 380 articles analysed, some 40 individual researchers have been identified; sometimes as authors, but also as interviewees, or in quotes. Their presence largely came late – from late 2013, after the publication of the Swedish PISA 2012 results – showing a steep decline in all three of the subject areas assessed. A possible explanation for this result is that the articles within our sample all meet the combination of hits for ‘school’, ‘PISA’ and ‘research’. Researchers might have been present in the education debate in other arenas, and perhaps did not mention PISA. The academics with the most frequent occurrences in the Swedish media debate on PISA between 2000 and 2016 are not from the field of education but from economics, linguistics and neuroscience ( and ). Some of these researchers debated not only education but also the position of educational research, making attempts to delegitimise it (e.g., Heller Sahlgren, 30 December 2015, Ingvar & Lundberg, 21 June 2006).

Figure 2. Academic scholars identified in the articles either as informants, authors or as the topics of conversation.

Figure 3. Number of positive, neutral/ambivalent and negative references to research in media articles.

In 2010, following the release of the Swedish 2009 PISA results, the education debate clearly intensified around PISA. Politically and ideologically delicate topics, such as grading and equity, were discussed with PISA as a source of knowledge. However, ‘equity’ seems to have received publicity not least thanks to two education researchers − Magnus OskarssonFootnote9 and Anders Jakobsson − who reported a decrease in equity as measured by PISA in the 2009 assessment. However, in the case of equity, as in many others, the question almost immediately became interconnected to elements in the debate that divided the debate in only two possible standpoints (Wiklund, Citation2018). Equity became connected to the effects of the ‘free school choice’ reform, a politically increasingly delicate question separating the proponents (mainly liberal/conservatives) from the sceptics (mainly representing the political left).

The PISA 2012 results were released in December 2013, showing a steep decline in the case of Sweden that caused a nearly chaotic situation to develop in the media. The number of articles for this year is 92, compared to 177, with a total of 392 mentions of ‘PISA’ in 2014. The problem was framed as a crisis calling for solutions. Among the suggested solutions was a so-called ‘school commission’ to be led by experts who could advise Sweden on how to solve the crisis. Educational researchers and their knowledge was debated anew: the Social Democrats suggested including Swedish educational researchers in such a commission, whereas Jan Björklund rejected the legitimacy of both the domestic knowledge more generally and that of educational research. Sweden’s largest morning paper, Dagens nyheter, reported:

The Social Democrats (S), as opposed to the government, want Swedish researchers to be included in the commission that now only will include international researchers and experts. ‘I would have anticipated Swedish top researchers as well and not that they are excluded. Swedish top researchers might have more knowledge about the Swedish school system’, says Ibrahim Baylan (S), spokesman for education. But Jan Björklund is hoping that the international commission will be able to present ‘inconvenient truths’. ‘An independent examination by international experts might very well draw other conclusions than we are doing here. A domestic debate risks getting blind’, he says. (Dagens nyheter 2014-01-15)

Only a small number of articles (16) referred negatively to research, but this number peaked in 2014 and 2015. Eleven articles (some of which were coded as referring to research in an ambivalent way) were coded to discuss ‘the failure of educational research’ ().

Several of the remaining examples of negative mentions relate to debates in the wake of nationwide media events that mobilized both new topics and strong emotions. One example occurred in 2015, when Swedish Radio (SR) broadcast a series of programmes entitled ‘PISA-doktrinen’ that, according to its trailer, aimed to critically investigate the results from PISA and the dominance of one actor (OECD) in education. Several national and international researchers (critical and otherwise) in areas such as assessment, policy and educational philosophy were interviewed, as was the OECD Division Head for PISA Andreas Schleicher and other key people in education and policy.

The reception of PISA-doktrinen is no exception. Among political commentators, an intense, loud and even sarcastic debate emerged. One editorial referred to the critical voices from educational research in the programme as ‘research’ (within quotation marks as if to indicate its lack of legitimacy; Martéus 2 April 2015). Another stated ironically:

New Swedish researchFootnote10 questions whether the PISA results in scientific literacy with certainty shows that Swedish students’ knowledge in science has decreased. The knowledge of Swedish students, not only in science, is the best in the world. Everybody knows that! Swedish schools are all together an incredibly knowledgeable world and this situation – naturally – leads to the very best result in the world. (Aftonbladet 2 April 2015)

However, for the large number of uses of research in the media, we can conclude that educational research, in the sense we have defined it for this paper, is mentioned in a neutral or sometimes ambivalent way. Other types of research on educational issues, such as economic or psychology research, are also referred to in the media education debate but have not been focused on in the present analysis. However, it is noticeable that research from the Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education, IFAU (Institutet för arbetsmarknads- och utbildningspolitisk utvärdering) appears to hold a legitimate position similar to that of the PISA reports. Swedish education researchers mainly appear in interview articles or as authors of debate articles; other debaters rarely refer to them as legitimate knowledge sources. Meanwhile, international studies and researchers (also in education) are, without exception, referred to in a positive way. Among the articles with references to international research about PISA and education, the predominant occasions are interviews with Finnish researchers.

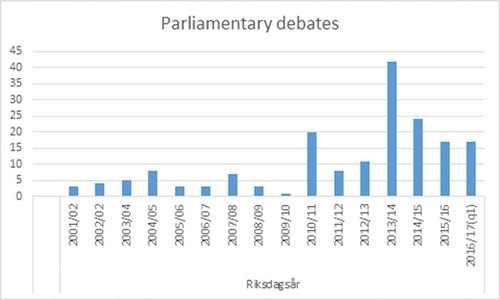

The use of PISA in parliamentary debates

In the parliamentary debates, as in the media analysis, there is a clear increase in the number of references to PISA over the years (). In each debate, PISA is used many times (581 in total) and by many different members of parliament (MPs). Compared to the logic of media, politics is not about reporting on information, but acting on it. Politicians come up with solutions to problems; these solutions are sometimes new, sometimes old, and sometimes not originally their own. They ‘borrow’ without making it explicit (Spreen, Citation2004; Waldow, Citation2009).

Figure 4. Number of parliamentary debates (N = 176) where the word PISA is used in 2001/02 to 2016/17 (quarter 1). All parliamentary debate protocols since 1971 have been digitalised, thus the increase in references to PISA reflects an actual change

When analysing how politicians use PISA, we basically find two different political orientations. The first uses PISA to argue for ideas that do not necessarily relate to how other countries do, but mainly that they perform better and that something needs to be done (about the Swedish school results). We can call this a ‘result–reform’ orientation. Secondly, if politicians use PISA to actually study practitioners in other countries, we call this a ‘learning–reform’ orientation. Thus, the first orientation is more about externalization in a legitimacy fashion, whereas the latter can be seen as actual policy borrowing. In the total use of PISA in parliamentary debates, the latter form is clearly more unusual. Only 22 of the 581 uses make explicit reference to what can be learned from other countries. Of course, we can assume that some ‘silent borrowing’ (Waldow, Citation2009) is taking place; still, this clearly indicates that references made to ‘the international’, as represented by PISA, is a matter of externalization in order to legitimize national policy.

Overall, our material from Swedish parliamentary debates mentioned PISA in connection with education 581 times. However, the categories in are only based on examples where PISA was used to legitimize or delegitimise various reforms or actions. Thus, the table contains the use of PISA both as a pre- and counter-argument, although PISA is most commonly used to argue for something; that is, as a pro-argument. In total, PISA was coded 356 times as arguments in connection with 34 different reforms or actions ().

Table 1. The most frequent topics for which PISA has been used as argument (number of media articles coded). Encoding completed with NVivo 11.0

Table 2. How often PISA has been used to argue for (and occasionally against) specific reforms and other political measures 2002-2017 (quarter 1). Encoding completed with NVivo 11.0

The most common way of using PISA is to argue that Swedish schools need to be more equal, although a few of these figures represent early examples from PISA 2000, which showed that Swedish schools were more equal than those of other countries. In other words, it is clear that PISA is used in a Swedish context, where the issue of equity and equivalence have traditionally engaged politicians in all parties (Lundgren, Citation2017). The question of equity and equivalence is also equally present throughout the studied period. These figures may be different in other countries, where other issues have higher priority. At the same time, equivalence within a country’s school system is also something that PISA reports have highlighted as a prerequisite for a high average score. The second most common way of using PISA is in an argument to focus on the teachers’ professional conditions and development. Most of the material encoded here comes in the wake of PISA 2012. This also applies when using PISA to argue for more support at school. Arguments for more order and discipline and higher demands came mainly in connection with PISA 2009. The same applies to the issue of digital competence. Questions about PISA in relation to immigration have been unilaterally driven by the Swedish Nationalist Party [Sverigedemokraterna]. Similarly, order and discipline issues and questions about early grading have been driven primarily by conservatives, and resistance to profit on private schools or tax cuts associated with lower standards in education has been driven by the left-wing parties. In other words, both historical consistency and party-political differences exist within the question of what PISA is used to argue for. This is also a probable explanation of the political divide in use of PISA that we identified in our media analysis. We also see some changes in the arguments over the PISA cycles that relate to success factors stressed in OECD reports (cf. OECD, Citation2015).

There are different ways to use PISA as an argument. The most common is to promote new reform in the light of falling results. The material contains 68 examples of references to decreasing results over time and 21 examples of being below average. The few opposite examples that exist occurred at the beginning and end of the period of investigation. This reflects Sweden’s score development at PISA, but political research has shown that it is very effective to refer to a crisis or deterioration when seeking legitimacy for a new reform (Maguire, Citation2014; Nordin, Citation2014; König, Citation2016; Landahl & Lundahl, Citation2017; Steiner-Kahmsi, 2018). There are also a few examples in the material of debates about how PISA is being interpreted, if it does or does not provide a sufficient picture of Swedish education. In general, however, most debates are based on the fact that the PISA results are correct both in the decline and in the upturn of the Swedish results. Only six or seven references are made to research in connection with PISA results.

It is also evident that PISA is used in a purely political game: the ‘blame game’. There are 32 examples in the material where the political Left uses PISA to discredit the Right, and 24 examples where the Right blames the Left for the deterioration.

In sum, it has become clear that PISA is used in parliamentary debates for national political ‘trench warfare’ on key topics such as early or late grading, preschool or parental custody, private school or comprehensive public school, traditional teacher-centred or child-centred education, and decentralization or central governing. We also note that the PISA debate is rarely about what educational researchers would define as real international comparisons and international influences. In other words, references to PISA are examples of how externalization takes place in the political discourse in order to legitimize or delegitimise education reforms. Falling or rising PISA results are often the only argument necessary when debating for a reform.

The use of educational research in parliamentary debates

In the parliamentary debates between January 2000 and April 2017, the term ‘educational research’ [pedagogisk forskning] was used on 94 occasions in 27 different parliamentary protocols. Compared with our previous analysis of how PISA is used in parliamentary debates, it is interesting that the explicit reference to educational research is approximately one-sixth of the amount of references to PISA during the same period. As with the term PISA, educational research is used in the political discourse, where both the Left and the Right accuse each other of refraining from research. Most commonly, however, educational research appears in research policy contexts, such as in debates on research propositions and budget propositions ().

Table 3. How often “educational research” has been used in different ways in parliamentary debates 2000-2017 (quarter 1). Encoding completed with NVivo 11.0.

In the parliamentary debates, findings from educational research are rarely used in an argument for specific reforms and actions. In other words, there seems to be very little borrowing from educational research. When educational research is used in an externalizing way, the references are often vague and lofty; for example:

In the curriculum, no specific way of teaching is prescribed. However, there is no doubt that a subject-integrated and varied work approach with both theoretical and practical technical features has strong support in educational research and practice. (Prot. 2000/01: 61, Ingegerd Wärnersson (S) [The Social Democrats], Answer to interpellations)

Actual references to research are only used once, and then in a debate about the grades in Year 4. Here it becomes clear that different parties make different assessments of educational research.

I have read some articles on the subject. Most of them are negative about grades in low ages. But most of these articles – most of which appear when you Google the topic – are based on a single source, which is an interview with Christian Lundahl, professor of education. He thinks that we here in the Parliament should make decisions on scientific, evidence-based grounds. But the interview with him was not evidence-based at all. If you look closer at the text, you can see that he says what he thinks about the matter in many ways. I have looked up the sources [he uses], and there are extremely insufficient sources about this. (Prot. 2016/17: 76 Robert Stenkvist, SD [The Nationalist Party], An experimental activity with grades from Year 4)

The Left Party (‘Vänsterpartiet’), on the other hand, has shown greater confidence in the research on the issue:

In 2015, the Swedish Research Council presented a research report that rejected the idea of early grades. Christian Lundahl has been mentioned earlier here in the speaker chair. He is a professor of education, unlike the one who mentioned him. Christian Lundahl led the work with the report and, together with colleagues, concluded that early grades have a negative impact on many students, especially those with the most difficult schooling. The students, on the other hand, perform better if they receive continuous feedback with positive information on how to improve their work. (Prot. 2016/17: 76 Daniel Riazat (V) [The Left Party], An experimental activity with grades from Year 4)

References like the ones above to specific research are rare. When politicians talk of educational research, it is more as a matter of research politics. We also see that the political discourse about research is generally about investing more money in educational research − but not all kinds of research. The politicians advocate the need for more practice-oriented research, as the following quotation exemplifies:

I totally share the view that we need more research graduates in school. Everyone working in Swedish schools will work on a scientific basis. All teaching must be carried out from a scientific basis. The support for doing so will be so much stronger if the teachers and colleges are doctoral graduates and people who choose to do research in parallel with their teaching profession. The development we are in today, where educational research is increasingly appreciating the school practice – what is actually happening in the classroom, which provides learning – is also strengthened by having more effective teachers who do research. The teaching profession should primarily be an active researcher profession rather than a profession that is merely subject to research. (Prot. 2016/17: 78 Gustav Fridolin (MP) [The Green Party], Answer to interpellations)

Throughout the parliamentary debate on educational research, practice-oriented and didactic research is requested and expected to be useful. Similar requests for more practice-oriented research to solve the problems – which, thanks to the negative trends in PISA, have incontestably been identified as an education crisis – are emergent in the media analysis as well. In contrast, the need for more systemic and argumentative or theoretical research has never, according to our analysis, been raised in the political sphere.

The use of educational research in parliamentary debates is rare. PISA appears significantly more ‘useful’ as an argument and counter-argument. Meanwhile, members of parliament safeguard the educational research and find it important, as long as it is practice-oriented.

PISA is a useful authoritative reference that invites selective use for building arguments in the political sphere, where the rationality is to frame questions as ‘a problem that can be solved by political decision making’ (Weingart et al., Citation2000, p. 263). PISA delivers lots of results that seem to confirm almost any ideological stance around the school and justify, for example, both increased classroom discipline and increased student influence. On the other hand, the growing request for a school based on science, together with political fear of scientific uncertainties, pushes educational research towards claims it could not fulfil. As our media analysis has shown, educational researchers who have tried to stress critical points have been severely criticized in the press. In several cases, they were accused of being too politically involved (Bergström, 15 December 2010), and in other cases they were rhetorically portrayed as unreliable (Marteus, 2 April 2015) or as the very cause of the crisis of Swedish schools (Heller Sahlgren, 30 December 2015).

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to study the legitimization of educational politics based on different uses of authoritative references. We did this by analysing the use of PISA and educational research in the eight largest print media outlets in Sweden, as well as in parliamentary debates since the launch of PISA in 2000. We have described the result as a selective use of PISA data and of educational research in the education debate.

Media, politics and research are different discursive spheres that have different rationalities and ways of using – and not using – information (Weingart et al., Citation2000). Even if media and politics are based on different logics, some similarities are identified in this study in that both spheres seemingly rely more on PISA than on educational research, and that PISA is mainly referred to as a way of pointing at problems than for actual learning.

Our analysis shows that politics and the media debate concerning education seems disinterested in educational research in a broader sense, or – in a particular sense of interest – refers to it as a problem rather than as knowledge of value. On the other hand, PISA seems to offer sufficient and ‘neutral’ authoritative knowledge and support for policy and reforms to judge from the arguments of the lion’s share of actors in this study. When educational research is called for, it is as research with a focus on practice-oriented and classroom-focused approaches. While such educational research is indeed important, we believe that the expectations from it are to provide evidence on how to improve teaching and learning with the goals of increasing PISA results. Thus, PISA points at problems that educational research is either said to have caused or cannot be relied upon to solve.

When PISA is used in arguments to point at solutions, it is in the context of externalizations from abroad. This means that PISA is used to identify problems by pointing at low PISA results and then to selectively point at desired solutions from countries with higher results. This use of PISA is consistent with the notion of policy borrowing. According to Schriewer (Citation1990), the national references through which educational systems legitimize themselves are under constant threat due to rapid social, economic and political changes. Policy borrowing then becomes an effective way to introduce change and break with the past through transferring education models, practices, and discourses from other educational systems. However, policy borrowing does not always occur with the actual attempt to introduce foreign policy in the own country. Instead, referring to the situation abroad – as presented by PISA reports, for example, – can be seen as a strategic way of legitimizing something that has more trust than local policy or domestic knowledge sources. This is what Schriewer (Citation1990) called externalization. Thus, we argue that referring to PISA is often not about actual policy borrowing, but more a way of ‘disguising’ local policy in order to legitimize it through externalization.

Especially in the parliamentary debates, externalization – in the sense of vague references to what has to be done as a consequence of PISA – reinforces traditional Swedish political trenches in the field of education rather than challenges them. Accordingly, it is reasonable to believe that this situation is nurtured by a media discourse in which the ‘force of international tests dichotomises education into an either-or situation of success or failure’ (Wiklund, Citation2018, p. 129).

Only a few political parties have used educational research as an externalization, while PISA is used as an authoritative reference for all political orientations. We could even argue that educational research becomes an object of politics in itself. Our analysis shows that instead of valuing different sources of knowledge as just that – different – the political education debate has turned into a questioning of their legitimacy.

Weingart (Citation1999) claimed that the unthinkable liaison between science and politics has changed during the last century, resulting in a somewhat dangerous coupling of these spheres: with a high cost for both politics and science. The scientification of politics meant that scientists’ advice was used for political means. However, due to the inherent uncertainty of scientific knowledge, this coupling, according to Weingart, came to weaken both science and politics. A similar coupling was observed in Sweden in the 1980s, when educational researchers were criticized for being too close to the government (which, at the time, consisted of Social Democrats), and therefore started to build some distance by developing critical perspectives (Härnquist, Citation1997). Today, as we have stated, our analysis shows that politics and the media debate seem disinterested in educational research in a broader sense.

Of course, such an approach to educational research can be seen as a sound decoupling where research became autonomous, and it can also be seen as an effect of the inherent logic of media and politics to point at problems and possible solutions. However, the present study adds to previous research (Edling & Liljestrand, Citation2019; Maguire, Citation2014; Wiklund, Citation2018) by identifying an increasing distrust in educational research and ‘the people labelled as pedagogues’ (Edling & Liljestrand, Citation2019, p. 17). We are among those who have been openly discredited in the debate, and so have our colleagues, so this has been a troublesome research journey. However, it has also been a rewarding study to conduct. The discredit is evidently neither to consider personal failures nor even an isolated Swedish phenomenon, although the Swedish case seems to be strong (Edling & Liljestrand, Citation2019). Studying education as a researcher in the era of large-scale international studies is not an innocent practice. This study has stressed the need for researchers, as professionals, to learn about the discourses and rationalities of media and political sphere. However, we must also acknowledge and accept them as different to our scientific sphere, but still important. According to the National School Act, Swedish education shall rest on a scientific foundation. Seemingly though, it rests, at least the debates on school reforms, on PISA. We strongly believe that educational research, in its broader sense, has important contributions to make in educational policy reform.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council under Grant [dnr/ref] 2014-1952, From Paris to PISA. Governing Education by Comparison 1867-2015.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

3. We have verified that all of the media sources included in the search have been digitally published since 2000.

4. See further description at http://data.riksdagen.se/in-english/.

5. In Swedish, several terms can be used to denote what, in English, is called educational research. Other terms than ‘pedagogisk forskning’ for educational research are ‘utbildningsvetenskap’ (mentioned in 30 protocols), and ‘didactic research’ (mentioned in 23 protocols). Looking more broadly for the terms ‘research’ and ‘school’ within 50 words of each other found 100 protocols.

6. Only those instances clearly positioned at the extreme ends of this category have been classified as discussing research in a primarily ‘positive way’ or ‘negative or seemingly falsifying way’.

7. Examples include the two series of programmes produced by the Swedish radio (SR) in 2008 (Kris i skolan/Crisis in school) and in 2015 (PISA-doktrinen), a series of articles by the journalist Maciej Zaremba in Dagens nyheter in 2011 (Hem till skolan) and the semi-documentary Klass 9A produced by Swedish television in 2011.

8. Björklund’s name appears in almost one-third of all articles in this media analysis (385 times in 137 articles).

9. Oskarsson is an independent academic scholar but, in his role as PISA project leader, is also connected to Skolverket.

10. Serder (Citation2015).

References

- Andersen, J. A. (2009). Organisasjonsteori. Fra argument og motargument til kunnskap. Universitetsforlaget.

- Ball, S. (2016). The education debate. Policy Press.

- Bergström, H. (2010, December 15). Bluff om PISA. [The scam about PISA]. Dagens Nyheter. http://ret.nu/UDBylUBH

- Bieber, T., & Martens, K. (2011). The OECD PISA study as a soft power in education? Lessons from Switzerland and the US. European Journal of Education, 46(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2010.01462.x

- Breakspear, S. (2012). The policy impact of PISA: An exploration of the normative effects of international benchmarking in school system performance. OECD Education Working Papers No. 71. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k9fdfqffr28-en

- Carvalho, L. M. (2012). The fabrications and travels of a knowledge-policy instrument. European Educational Research Journal, 11(2), 172–188. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2012.11.2.172.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Edling, S., & Liljestrand, J. (2019). Let’s talk about teacher education! Analysing the media debates in 2016–2017 on teacher education using Sweden as a case. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 48(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2019.1631255

- Franklin, B. (2004). Education, education and indoctrination! Packaging politics and the three Rs. Journal of Education Policy, 19(3), 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093042000207601

- Gorur, R. (2014). Towards a sociology of measurement in education policy. European Educational Research Journal, 13(1), 58–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2014.13.1.58.

- Gorur, R. (2015). Situated, relational and practice-oriented. The actor-network theory approach. In K. N. Gulson, M. Clarke, & E. B. Petersen (Eds.), Education policy and contemporary theory. Implications for research (pp. 87–98). Routledge.

- Grek, S. (2009). Governing by numbers: The PISA ‘effect’ in Europe. Journal of Education Policy, 24(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930802412669

- Härnquist, K. (1997). Educational research in Sweden: Infrastructure and Orientation. In K.-E. Rosengren & B. Öhngren (Eds.), An evaluation of Swedish research in education. HFSR, 235–272.

- Haugsbakk, G. (2013). From Sputnik to PISA shock – New technology and educational reform in Norway and Sweden. Education Inquiry, 4(4), 23222. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i4.23222

- Heller Sahlgren, G. (2015, December 30). Kunskapsskolans fall och återkomst. [The fall and return of the school of knowledge]. Dagens nyheter. http://ret.nu/6mKeZbBZ

- Hopfenbeck, T., & Görgen, K. (2017). The politics of PISA: The media, policy and public responses in Norway and England. European Journal of Education, 52(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12219

- Hultén, M. (2019). Striden om den goda skolan. Hur kunskapsfrågan enat, splittrat och förändrat svensk skola och skoldebatt. Nordic Academic Press.

- Hultqvist, E., Lindblad, S., & Popkewitz, T. S. (2018). Critical analyses of educational reforms in an era of transnational governance. Springer.

- Ingvar, M., & Lundberg, I. (2006, June 21). Läscentrum mot bättre vetande. [Centre for reading against better knowledge]. Svenska Dagbladet. http://ret.nu/u1N3Lxfe

- Kamens, D. D. H. (2013). Globalization and the emergence of an audit culture: PISA and the search for ‘best practices’ and magic bullets. In H.-D. Meyer & A. Benavot (Eds.), PISA, power and policy. The emergence of global educational governance (pp. 117–140). Symposium Books.

- König, P. D. (2016). Communicating austerity measures during times of crisis: A comparative empirical analysis of four heads of government. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18(3), 538–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148115625380

- Kreiner, S. (2011). Is the foundation under PISA solid? A critical look at the scaling model underlying international comparisons of student attainment. Köpenhamns Universitet, Department of Biostatistics.

- Landahl, J., & Lundahl, C. (Eds.). (2017). Bortom PISA. Internationell och jämförande pedagogik. [Beyond PISA. International and comparative Pedagogy]. Natur och Kultur.

- Lundahl, C., Hultén, M., Klapp, A., & Mickwitz, L. (2015). Betygens geografi – Forskning om betyg och summativa bedömningar i Sverige och internationellt. Delrapport från Skolforskprojektet. Vetenskapsrådet. Vetenskapsrådet.

- Lundgren, U. P. (2017). En utbildning för alla – Skolan expanderar [Education for all – The expansion of schooling]. In U. P. Lundgren, R. Säljö, & C. Lidberg (Eds.), Skola, lärande, bildning – En grundbok för lärare (4th ed., pp. 91–114). Natur och Kultur.

- Maguire, M. (2014). Reforming teacher education in england − ‘An economy of discourses of truth’. In M. A. Peters, B. Cowev, & I. Menter (Eds.), A companion to research in teacher education (pp. 483–494). Springer Nature.

- Martens, K. (2007). How to become an influential actor: The ‘comparative turn’ in OECD education policy. In K. Martens, A. Rusconi, & K. Lutz (Eds.), Transformations of the state and global governance (pp. 40–56). Routledge.

- Martéus, A. C. (2015, April 2). Försök inte babbla bort PISA. [Don’t babble PISA away]. Expressen. http://ret.nu/qHDz7pS

- Nardi, E. (2008). Cultural biases: A non-anglophone perspective. Assessment in education: Principles. Policy & Practice, 15(3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940802417467.

- Nordin, A. (2014). Crisis as a discursive legitimation strategy in educational reforms: A critical policy analysis. Education Inquiry, 5(1), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v5.24047.

- OECD. (2015). Improving schools in Sweden: An OECD perspective. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/education/school/Improving-Schools-in-Sweden.pdf

- Pettersson, D., Prøitz, T., & Forsberg, E. (2017). From role models to nations in need of advice: Norway and Sweden under the OECD’s magnifying glass. Journal of Education Policy, 32(6), 721-744. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1301557

- Pizmony-Levy, O. (2017). Big comparisons, little knowledge: Public engagement with PISA in the USA and Israel. In A. Wiseman & C. Stevens Taylor (Eds.), The OECD’s impact on education worldwide (pp. 125–156). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Pizmony-Levy, O., & Bjorklund, P., Jr. (2018). International assessments of student achievement and public confidence in education: Evidence from a cross-national study. Oxford Review of Education, 44(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1389714

- Ringarp, J., & Waldow, F. (2016). From ‘silent borrowing’to the international argument–legitimating Swedish educational policy from 1945 to the present day. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2016(1), 29583. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v2.29583

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE Publications.

- Schriewer, J. (1990). The method of comparison and the need for externalization: Methodological criteria and sociological concepts. In J. Schriewer & B. Holmes (Eds.), Theories and methods in comparative education (pp. 3–52). Lang.

- Schriewer, J., & Martinez, C. (2004). Constructions of internationality in education. In G. Steiner-Khamsi (Ed.), The global politics of educational borrowing and lending (pp. 29–53). Teachers College Press.

- Sellar, S., & Lingard, B. (2013). PISA and the expanding role of the OECD in global educational governance. In I. H. Meyer & A. Benavot (Eds.), PISA, power and policy (pp. 185–206). Symposium Books Ltd.

- Sellar, S. (2015). A feel for numbers: Affect, data and education policy. Critical Studies in Education, 56(1), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2015.981198.

- Serder, M. (2015). Möten med PISA. Kunskapsmätning som samspel mellan elever och provuppgifter i och om naturvetenskap [Encounters with PISA. Knowledge measurement as co-action between students and test assignments in and about science] [Doctoral dissertation]. Malmö University.

- Serder, M., & Ideland, M. (2016). PISA truth effects: The construction of low performance. Discourse: The Cultural Politics of Education, 37(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1025039.

- Spreen, C. A. (2004). Appropriating borrowed policies: Outcomes-based education in South Africa. In G. Steiner-Khamsi (Ed.), The global politics of educational borrowing and lending (pp. 101–113). Teachers College Press.

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2012). Understanding policy borrowing and lending building comparative policy studies. In G. Steiner-Khamsi & F. Waldow (Eds.), World yearbook of education 2012: Policy borrowing and lending in education (pp. 4–17). Routledge.

- Steiner-Khamsi, G., Appleton, M., & Vellan, S. (2018). Understanding business interests in international large-scale student assessments: A media analysis of the economist, financial times, and wall street journal. Oxford Review of Education, 44(2), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1379383

- Steiner-Khamsi, G., & Waldow, F. (Eds.). (2012). World yearbook of education 2012: Policy borrowing and lending in education. Routledge.

- Tveit, S., & Lundahl, C. (2018). New modes of policy legitimation in education: (Mis)using comparative data to effectuate assessment reform. European Educational Research Journal, 17(5), 631–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904117728846

- Waldow, F. (2009). Undeclared imports: Silent borrowing in educational policy‐making and research in Sweden. Comparative Education, 45(4), 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060903391628

- Waldow, F. (2017). Projecting images of the ‘good’ and the ‘bad school’: Top scorers in educational large-scale assessments as reference societies. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(5), 647–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2016.1262245

- Weingart, P. (1999). Scientific expertise and political accountability: Paradoxes of science in politics. Science and Public Policy, 26(3), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154399781782437

- Weingart, P., Engels, A., & Pansegrau, P. (2000). Risks of communication: Discourses on climate change in science, politics, and the mass media. Public Understanding of Science, 9(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/304

- Wiklund, M. (2018). The media as apparatus in the becoming of education policy: Education media discourse during two electoral periods. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 16(2), 99–134.

- Wiseman, A. (2010). The uses of evidence for educational policymaking: Global contexts and international trends. Review of Research in Education, 34(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X09350472