ABSTRACT

Research – practice partnerships (RPPs) in education have been on the political agenda in Sweden during the last years. RPPs are long-term collaborations between higher education institutions and school districts (municipalities) and schools which intend to facilitate teacher-researcher collaboration in close relation to the teaching practice. This study focuses on a Swedish RPP between one university and multiple municipalities. It explores why two comparable municipalities differed in their success in the partnership’s core activity: calls for funding for collaborative research. Using the theoretical framework of absorptive capacity and boundary infrastructure, the internal organization of the two municipalities and how the RPP-initiative was docked into these organizations were analysed. We interviewed municipal- and school-level actors involved in the application processes within the two municipalities. Significant results include that for equal opportunities for teacher – researcher collaboration, municipalities must develop an organizational capacity that allows them to learn productively from external partners and recognize the knowledge provided by boundary spanners. This study contributes to the expanding literature on partners’ strategies to address emerging challenges of RPPs. It expands our understanding of how municipalities’ internal organization facilitates or hinders collaborative research within RPPs in education.

Introduction

In recent years, research – practice partnerships (RPPs) in education have been on the education policy agenda in Sweden. As part of the evidence-based education movement, RPPs are emerging in European countries (Fjørtoft & Sandvik, Citation2021; Nutley et al., Citation2008; Prøitz & Rye, Citation2023; Sjölund et al., Citation2022) and they have become an integrated part of the American educational system (Farrell et al., Citation2021). RPPs are long-term research collaborations between higher education institutions (HEIs) and school districts and schools intended to facilitate teacher – researcher collaboration closely within the teaching practice. The Swedish government has taken several measures to strengthen teachers’ capacities to engage in research during the last decades, and in 2017 it launched a national initiative to establish RPPs between HEIs, municipalities, independent school providers, and schools (Prøitz et al., Citation2022). It is labelled the ULF initiative (Utbildning/Education, Lärande/Learning, Forskning/Research) and aims to strengthen the opportunities for research collaboration between teachers and researchers closely related to the teaching practice. Ultimately, the ULF initiative intends to stimulate research in schools and teacher education, supporting educational improvement (Prøitz & Rye, Citation2023).

Prior studies have shown that RPPs have contributed to teachers’ engagement in research, evidence in schools and school districts, and educational improvement and transformation (Coburn et al., Citation2013; Farrell et al., Citation2021). Additionally, we know that RPPs face several challenges, such as HEIs and schools being ‘two separate knowledge communities with their unique cultural and historical practices and traditions’ (Lillejord & Børte, Citation2016, p. 561). When researchers and teachers conduct research together, these differences cause a theory – practice divide (Christianakis, Citation2010). They may also cause RPP partners to speak past one another – however informed their intentions and commitments may be – potentially leading to different understandings of the partnership’s purpose (Farrell, Harrison, et al., Citation2019). To achieve genuine collaboration, RPP partners must understand each partner’s everyday working conditions and knowledge cultures. Therefore, RPP partners must also be open to learning from one another and adjusting their internal structures and processes to meet the joint commitments to bridge their distinct cultures.

That partnerships face challenges related to their collaborating organizations’ internal traditions and ways of doing things is well known. However, what is less well-known is ‘when and under what conditions RPPs can navigate these challenges and make [progress toward] their goals for longer-term outcomes’ (Farrell et al., Citation2022, p. 198). After reviewing the literature on RPPs, Coburn and Penuel (Citation2016, p. 48) concluded that research has primarily targeted challenges but provided ‘little insight into how partnership designs and strategies used by participants can address these challenges’. They called for studies on the outcomes of partnerships’ varying strategies to achieve genuine, substantive collaboration.

Answering these calls, this study focuses on a Swedish RPP in education between one HEI (a university) and multiple school districts (municipalities). This RPP is part of the national Swedish ULF initiative, aimed at establishing RPPs between HEIs and school districts to support various forms of collaboration between teachers and researchers. The national initiative has stimulated the growth of partnerships between HEIs and schools and municipalities, utilizing diverse strategies to facilitate collaboration (Benerdal & Westman, Citation2023; Jarl et al., Citation2024; Popa, Citation2023; Prøitz & Rye, Citation2023). The primary research strategy emphasized in the RPP which we explore in this article, and which two of the authors have been actors in, is calls for funding for collaborative research. Reviewing this partnership’s first call (2018), we identified the uneven success of the municipalities in terms of participation and research funding. We found this outcome puzzling as the RPP partners jointly and strategically designed the call to be inclusive. The call included a two-step process: First, teachers and researchers working at schools in the municipalities and the university were invited to submit sketches in the first step; second, it was widely announced and supported by collaborating partners’ leadership. We found that two municipalities facing similar socioeconomic and demographic conditions were equally successful in the number of sketches submitted during the first step but differed significantly in their research funding during the second step.

Based on these findings, we designed this study to explore the organizational capacities of two partnering municipalities to actively engage in the RPP’s core research strategy, i.e. calls for funding for collaborative research. Significant results include that for equal opportunities for teacher – researcher collaboration, municipalities must develop an organizational capacity that allows them to learn productively from external partners and recognize the knowledge provided by boundary spanners. Due to the highly decentralized, fragmented educational systems in Sweden, where authority is transferred to municipalities and independent school providers, we assumed and found variation in organizational capacity among municipalities. The study expands our understanding of how school districts’ internal organization facilitates or hinders collaborative research within RPPs in education. In this way, it contributes significantly to the literature on partnership challenges and how they can be addressed.

Organizational learning in research – practice partnerships

The evidence-based education movement pressures school districts and schools to use research to transform and improve education. Teachers’ active involvement in research is considered crucial in encouraging more use of evidence in schools and school districts. The current body of literature is increasingly focused on research where researchers and teachers collaborate to address problems of practice (Cochrane-Smith & Lytle, Citation1993; Lau & Still, Citation2014; Wagner, Citation1997; Westbrook et al., Citation2022). RPPs have been presented as a promising approach to encourage teacher – researcher collaboration (Coburn & Penuel, Citation2016; Coburn et al., Citation2013; Wentworth et al., Citation2023) and promote teacher empowerment in educational reform (Datnow, Citation2020). RPPs’ growth represents the efforts of partners to ‘pursue locally driven, collaborative approaches to research in support of educational equity’ (Farrell et al., Citation2021, p. 2). Scholars have defined RPPs as ‘long-term, mutualistic collaborations between practitioners and researchers that are intentionally organized to investigate problems of practice and solutions for improving district outcomes’ (Coburn et al., Citation2013, p. 2). Farrell et al. (Citation2021) emphasize that these partnerships are long-term collaborations whose leading activity is engagement with research.

It is well-known that RPPs face significant challenges (Coburn & Penuel, Citation2016; W. R. Penuel et al., Citation2020; Sjölund & Lindvall, Citation2023; Wentworth et al., Citation2017). They must confront leadership turnover, turbulent environments, varying traditions and knowledge cultures, and different paces of work among partners (Farrell et al., Citation2022). Scholars have particularly highlighted the complex and shifting structure of school districts – including many different levels and divisions – as an aggravating ingredient when developing partnerships (Coburn & Penuel, Citation2016; Coburn et al., Citation2009; Spillane, Citation1998). To handle challenges and bridge the different traditions, cultures, and everyday routines among partners, RPPs must create structures that allow them to ‘innovate in the face of challenges and grow from their experiences’ (Farrell et al., Citation2022, p. 198). Moreover, scholars have noted that improved dialogue between partners does not come easy but requires strategic leadership (Lillejord & Børte, Citation2016) and that there is a need for conceptual frameworks that allow for in-depth descriptions of what ‘the actual work of collaboration looks like’ (Farrell et al., Citation2022, p. 198).

This study draws upon the concept of absorptive capacity from Cohen and Levinthal’s (Citation1990) seminal work on firms’ ability to exploit external knowledge. They argued that an organization’s ability to ‘evaluate and utilize outside knowledge’ depends on its ‘level of prior related knowledge’ (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990, p. 128). By absorptive capacity, they refer to the ability ‘to recognize the value of new information’ and to assimilate and apply it towards their purposes (p. 128). Education scholars have used the concept to study school districts’ capacity to learn from external partners (Farrell & Coburn, Citation2017; Farrell, Coburn, et al., Citation2019) and organizational learning in RPPs (Farrell et al., Citation2022).

Farrell and Coburn (Citation2017) developed ‘a framework for understanding districts’ capacity to productively learn from external sources of knowledge’, which identifies that a school district’s ‘prior related knowledge, pathways for communication, strategic knowledge leadership, and resources’ are critical preconditions for its absorptive capacity (p. 136). In addition, it identifies seemingly impactful characteristics of the external partner and the interactions between the district and the partner (Farrell & Coburn, Citation2017, p. 136). By applying this framework, Farrell, Coburn, et al. (Citation2019) discerned variations in how two departments that belong to the same school district and work with the same external partner are integrated and use external ideas. They concluded that the differences were due to ‘organizational conditions that foster absorptive capacity and the nature of department – partner relations’ (Farrell, Coburn, et al., Citation2019, p. 955).

To explore in further depth the nature of relations between school districts and external partners, Farrell et al. (Citation2022) integrated the concept of boundary infrastructure with the framework of absorptive capacity (also see Hopkins et al., Citation2019; W. Penuel et al., Citation2015). They argued that RPP partners’ organizational learning depends on their prior organizational capacities and conditions as well as the design of the boundary infrastructure, i.e. the networks, practices, and objects that function across partners. According to Farrell et al. (Citation2022, p. 2), for RPPs to be effective, they must designate roles for boundary work and design structures for interaction and artefacts. Through boundary spanners (i.e. designated roles), practices (i.e. interaction structures), and objects (i.e. artefacts), partnerships can handle differences between partners’ cultures, professional norms, and organizational routines. Boundary spanners, defined as ‘individuals who move across boundaries and facilitate connections between groups’, are regarded as especially valuable in terms of transitions across different sites (Farrell et al., Citation2022, p. 2). Indeed, Wentworth et al. (Citation2023, p. 5) suggest that brokers facilitate the ‘“joint work” of teachers and researchers by crossing the professional and organizational boundaries between their worlds’.

There is a growing body of literature on the ULF initiative, focusing on the roles of teachers, principals, and researchers in collaborative research (Forssten Seiser & Portfelt, Citation2024; Jarl et al., Citation2024; Prøitz & Rye, Citation2023) and the expectations on collaborative research among policy actors and practitioners (Bergmark & Hansson, Citation2021; Malmström, Citation2023; Öijen et al., Citation2020). Moreover, there are studies that disseminate results and learning outcomes from collaborative research projects (Ahlstrand & Andersson, Citation2021; Strandler & Harling, Citation2023; Tengberg et al., Citation2021). With few exceptions (Jarl et al., Citation2024; Popa, Citation2023; Prøitz & Rye, Citation2023), there is a lack of studies recognizing the ULF initiative as a concerted effort to establish formal, long-term, and mutualistic partnerships between HEIs and school districts. Benerdal and Westman (Citation2023) argue that ULF has ‘a bearing on organizational aspects’ and call for studies that shed light on the structures that facilitates or hinders collaborative research.

In the context of the ULF initiative, this study uses the concepts of absorptive capacity and boundary infrastructure to explore why two municipalities within a Swedish RPP between a university and multiple municipalities differ in their capacity to integrate and utilize the partnership’s core research activity, which calls for funding for collaborative research. Specifically, we examine the two municipalities’ enactment of the core activity in their pre-existing internal organizations. We use organizational capacity to broadly capture prior organizational capacities and conditions and the design of the boundary infrastructure. Two research questions frame this study:

RQ1. How can the organizational capacity in two municipalities that differ in success in the ULF RPP’s core research activity be understood?

RQ2. To what extent does the municipalities’ organizational capacity match the ULF RPP’s core research activity of calls for funding for collaborative research?

In the remainder of this article, we first discuss the policy context of RPPs in Sweden in the following background section. Second, we introduce this study’s RPP – its primary strategy which is calls for research funding – and review the outcome of the partnership’s first call (2018). Third, we discuss study designs, methods, and data sources. In the fourth section, we explore the organizational capacities of the two municipalities, which differed significantly in their success with the call. We conclude with a summary of the results, discussing the study limitations and main implications for educational research and practitioners.

Background – policy context of RPPs in Sweden

Despite strengthening teachers’ capacities to engage in research, an item on the political agenda in Sweden for several preceding decades, RPPs centred on research collaboration are a recent phenomenon. Since the late 1990s, the Swedish government has taken several measures to strengthen teachers’ research capacities, including reforms to introduce research-based teacher education, establish national postgraduate schools for teachers, earmark funding for research related to the teaching practice, and create positions for teachers with Ph.D.s (Arreman, Citation2008; Bergmark & Hansson, Citation2021). Since 2010, the Education Act stipulates that education should be based on research and proven experience (Magnusson & Malmström, Citation2023). The ULF initiative draws on these prior policies to strengthen teachers’ research capacities. It aims to establish a Swedish infrastructure of RPPs between HEIs, municipalities, and independent school providers (Benerdal & Westman, Citation2023; Prøitz et al., Citation2022) to generate national equal opportunities for research collaboration between teachers and researchers closely linked to the teaching practice.

Although Swedish teachers’ engagement in research is growing, their participation depends on the resources and interests of HEIs of municipalities and independent school providers (SOU Citation2018:19). The Swedish education system is highly decentralized and fragmented due to structural reforms in the 1990s, when authority was transferred from the central government to municipalities and independent school providers (Håkansson & Adolfsson, Citation2022). Subsequently, neoliberal reforms introduced a voucher system that legislated parents’ right to choose schools for their children and paved the way for an expansion of publicly funded independent schools (Lundahl, Citation2005). The responsibilities of municipalities and independent school providers include hiring and paying teachers and principals, allocating resources, organizing education, and answering to national standards (Jarl et al., Citation2012). In addition, these responsibilities include efforts to improve schools (Nordholm et al., Citation2021) and provide teachers with professional development (Kirsten & Wermke, Citation2016). The 1990s reforms’ decentralization also replaced detailed state regulations with management by objectives and results. Therefore, the role of the central government is limited to setting objectives and standards in the curriculum and following up on results. Conversely, municipalities and independent school providers bear a significant mandate in governing education.

Due to the decentralizing 1990s reforms and the principle of local self-government, which have characterized the political system in Sweden for decades (Montin, Citation2015), we may assume variation in municipal internal organization. However, while municipalities have extended autonomy to decide on their internal organization, there are some national regulations concerning local governance structures that apply to all 290 municipalities. At the municipal level, education governance includes a school board of locally elected politicians and an education administration office staffed with managers and officials supporting the school board and implementing its policies (Nordholm et al., Citation2021). Since 2018, per the Education Act (SFS Citation2010:800), all municipalities should employ a superintendent (skolchef) whose primary role is to support the school board in ensuring that the municipality’s education services meet national standards. Additionally, research has shown that positions as quality strategists and developers of quality and improvement have been frequently introduced within municipalities in recent years (Liljenberg & Andersson, Citation2023).

In Sweden, most HEIs are public agencies subject to national legislation. The central government provides resources for education and research and expects HEIs to interact with the surrounding society in its primary education and research activities. Teacher education has been university-based since the late 1970s, when a higher education reform transferred teacher education from teacher seminars to higher education alongside reforms in other welfare professions, such as nurses and social workers (Furuhagen et al., Citation2019). HEIs, which provide teacher education, regularly collaborate with municipalities and independent school providers on teacher students’ clinical placements.

Introducing the RPP and the case selection process

This section first introduces the RPP discussed in this article, along with its primary strategy to promote teacher-researcher collaboration: calls for funding for collaborative research. Second, it discusses the case selection process which is based on a review of the first call for research funding that was conducted within this RPP in 2018.

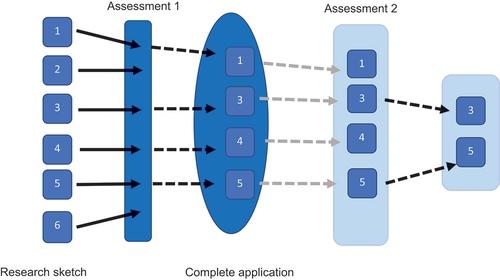

This study focuses on municipalities belonging to and partnered in an RPP between a HEI and multiple municipalities in Sweden. This partnership (hereafter called ‘the ULF RPP’) is part of the national ULF initiative. It is focused on the geographical area surrounding the HEI which, in 2017, initiated the partnership, inviting municipalities in the vicinity to join as partners. The number of residents in the municipalities that choose to become RPP partners would amount to approximately 1,000,000 and there is variation in municipalities’ sizes in terms of number of inhabitants. The partnership was established in 2018 through an agreement that regulates the partners’ mutual goals and commitments, including the central joint activity of calling for funding for collaborative research. The ULF RPP partners jointly designed the call for funding as a two-step process aiming to include teachers working at schools in the municipalities and university researchers. The outline of the research call, comprising two steps, is illustrated in .

In the first step, research sketches (RSs) with a two-page maximum are submitted by each applicant. An evaluation committee of representatives from the university and the municipalities assess the RSs with emphasis on the project idea and how it contributes to increased knowledge in educational research and teaching activities. In addition, the feasibility of the project is assessed. In the second step, applicants of sketches with the most significant potential are invited to submit a complete application. Primary applicants must have a Ph.D. to apply, and they should document formal arrangements for collaboration between researchers and at least one school or preschool. Municipalities must certify that they will provide organizational resources if the project is funded. The applications are assessed on the project’s scientific quality and potential to contribute to evidence-based education, collaboration, and dissemination of research results.

Reviewing RPP strategy outcomes

As part of the ULF RPP’s improvement work and as a preparatory work for this study, we reviewed the outcome of the 2018 call based on a mapping of the ULF RPP policy documents, such as the partnership’s formal agreement, including calls for funding regulations and events. In addition, the review is based on the results from an evaluation of the municipalities’ active participation and success in the call for research funds.

Per the inclusive aim to provide teachers and researchers among RPP partners equal opportunities to participate, the call was announced widely. Proceeding the call, information was continuously updated on the university’s website, and news was communicated via several municipalities’ web pages. Information was also communicated to municipalities’ leadership through the collaborative network structure of the region, which further spread information about the call to preschool teachers, teachers, and principals in the region. During the two weeks that the first step of the call was open, 99 RSs were submitted. Of these sketches, 68 were submitted from the municipalities and 31 from the university. As a result of the evaluation committee’s assessments of the submitted sketches, 20 sketches were invited to submit a complete application in step two. In the four weeks of step two, complete applications were received from 17 of the 20 sketches invited to participate in the second step. Eight of these 17 applications were granted funding. Most of the principal applicants in step two were employed by the university.

To evaluate municipalities’ active participation in the call, and as illustrated by below, we first evaluated the municipalities’ participation in RSs submitted by other partners, i.e. we examined the 31 RSs and application forms submitted by the university. We noted if a specific municipality was mentioned in the documents. Second, the 68 sketches submitted by the municipalities were reviewed to identify any reference to a municipality different from the one applying to either the RS or the application form. To measure the municipalities’ overall participation in the first step of the call, we summed the number of RSs submitted by each municipality with the participation in RSs from other collaborating partners (). To compare overall participation across the different municipalities, the total number of RSs was normalized to establish a ratio per 100,000 inhabitants (RSs/100,000). When reviewing the applications submitted in the second step of the research call, an uneven distribution of participating municipalities was seen. In the 17 applications reviewed, a combined total of eight municipalities were referenced. Most research applications referred to one municipality each. However, in five applications, between two and six municipalities were mentioned. As shown in , two municipalities, A and B, stood out as they were mentioned in 10 and 7 research applications, respectively. They were also the most successful municipalities regarding funded research applications (). Lastly, a ranking of municipalities with funded research applications was utilized to comprehensively assess their active engagement and success in the 2018 funding call. This ranking was based on the sum of RSs per 100,000 inhabitants and the total number of funded applications ().

Table 1. Table summarizing the municipalities’ engagement in the 2018 call for research funding, illustrated by submitted RSs by the municipalities, participation in other partners’ RSs, and complete applications.

We found that Municipality B succeeded significantly better than others in terms of active participation and research funding (Rank 1). Additionally, Municipality B, together with a neighbouring Municipality C showed the highest number of research sketches per 100,000 (RS/100 000) in the first step of the call in 2018. In this step, the number of RSs submitted by Municipality B and its collaborating partners amounted to 15. In the second step of the 2018 call, Municipality B participated in seven research applications, of which four were finally granted funding. The neighbouring Municipality C submitted eight RSs but did not participate in sketches submitted by other municipalities or the university. Despite the high number of RSs per 100,000, Municipality C was not mentioned in any research applications submitted in the second step of the call. Municipalities B and C showed considerably higher activity in the first step of the call than the other municipalities. They faced similar socioeconomic and demographic conditions, which allowed us to make a comparison centred on their internal structures. Based solely on the highest number of total submitted sketches and applications, Municipality A would have been selected. However, due to its size (number of inhabitants), illustrated by the number of RSs per 100,000 inhabitants, we consider this municipality an outlier, in terms of its demographic conditions, to be excluded.

Based on these findings, we devised a comparative case study to map the absorptive capacity – that is, the arrangements in the internal municipal organization that inform research and development and possible structures for external initiatives and collaboration.

Study design and methods

Regarding the analysis of the two municipalities’ organizational capacities, data were acquired through semi-structured interviews with municipal- and school-level actors involved in the application processes within the two municipalities. In total, we conducted eight interviews with ten respondents (). We initiated contact with administration managers and used snowball sampling to identify additional potential respondents at the school and municipal levels. Municipal-level respondents included the superintendent and the deputy superintendent in Municipality B and the deputy superintendent and an administration official with a position as a quality strategistFootnote1 in Municipality C; school-level respondents included principals and teachers in both municipalities. The teacher we interviewed in Municipality B also held a position as a scientific leader. In Municipality C, we interviewed three teachers in total.

Table 2. Overview of the respondents.

All respondents who participated in the study provided written, informed consent before the interviews commenced. The respondents were informed of the study’s objectives and their right to remain anonymous. The interview questions encompassed topics for mapping arrangements within the municipal organization regarding research and development and possible structures for external initiatives and collaboration. In addition, the questions included their view of the municipality’s initiatives for engaging in the ULF RPP and steps taken to provide organizational resources for the RPPs. Interviews were conducted online via Zoom from October 2021 to October 2022. Each interview lasted 45 to 60 minutes and was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. In the first step of the analytic work, the transcripts were examined several times to obtain an overall understanding of the municipal organization and its relation to the applications. In the second step, the critical concepts of absorptive capacity (i.e. strategic knowledge leadership, resources, prior related knowledge, and pathways for communication) and boundary infrastructure (i.e. boundary spanners, practices, and objects) were employed to deductively analyse organizational capacity in the two municipalities. According to Gibbs (Citation2018), using theoretically generated concepts in the empirical analysis is preferred, given that the codes used were generated theoretically rather than empirically.

Exploring the municipalities’ organizational capacity

Our overall results show that the organizational capacity in the two municipalities provided each with different starting points when the ULF RPP was introduced and the first call for funding for collaborative research was disseminated in 2018. By taking a historical perspective on the municipality organizations in the interviews, we identified strategic decisions made by former administration office managers and officials that proved crucial for the municipalities’ possibilities to respond to the sent-out call for funding. In the following sections, we will present our results, giving detailed descriptions of the municipalities’ organizational capacity, elaborating on the fundamental concepts of absorptive capacity (i.e. strategic knowledge leadership, resources, prior related knowledge, pathways for communication), and aspects of boundary infrastructure.

Strategic knowledge leadership and resources

In recent decades, Municipality B has responded strategically to national initiatives towards strengthening teachers’ capacity for engaging in research via making decisions to increase its internal research competence. The municipality thus had some level of preparedness when the statement ‘the education must be based on scientific ground and proven experience’ was added to the Swedish School law in 2010 (2010:800). The superintendent of Municipality B stated that strategic decisions were made before she entered her position; she respectfully admitted that she had her precursor to thank for the strategy to increase the municipality´s internal research competence ‘[looking] the way it does’. She emphasized that the former superintendent had worked hard to establish the idea of a school based on scientific ground and that she had been convinced that it also required investing in it. Early on, the idea was declared an overarching local political goal and a crucial part of the municipality’s school budget. According to the superintendent, having this long-term political goal made it straightforward for her to continue on this track.

Superintendent: When I came to Municipality B, it was [already] a prioritized political goal to have a school based on scientific grounds. And that’s nothing that you sort of decide [to do] without adding resources (…). It is always easier to maintain something like this than to make a big investment that costs a lot of money on a single occasion.

A significant financial investment was made in postgraduate education for teachers. When the interviews were conducted, four teachers in the municipality had taken a doctoral or licentiate degree. During their postgraduate education, they worked half-time in the municipality while studying on a half-time schedule, which provided the municipality access to several resources within the university, such as research databases, research networks, and researchers experienced in diverse research fields. In addition, the municipality’s internal organization was further developed to take advantage of the new knowledge that these teachers brought into the organization. When the first teacher graduated in 2014, a strategic position as a scientific leader was established in the municipality.

Superintendent: Yes, she is our scientific leader. She does some teaching, as we all think that it is important, but she also does some work together with the university and some work for the municipality. Her position is created so that she can maintain her competence while at the same time [being] a strong driving force in the municipality.

When the ULF RPP was constructed in 2018, it was essential for the superintendent to get involved. She appreciated that she, as superintendent, together with the representatives from the other municipalities, had been invited to participate throughout the process – all the way ‘from grain to loaf’. When she, and the other municipalities’ representatives, at the end of this process, had signed the agreement, she passed it on to other managers and officials in the organization to continue the work. In addition, for the deputy superintendent, this was given. She was well-informed about the ULF RPP through the different networks she participated in, and as head of the principals, she started a strategic effort to inform them. As principals have numerous things on their agenda, she knew that sending emails would not be effective. Instead, she targeted dedicated principals with stable school organizations to make them aware of the benefits of RPP involvement and further encouraged them to pass this on to their teachers.

Compared to Municipality B, managers and officials at the administration office in Municipality C chose a different path concerning prior national initiatives to strengthen teachers’ capacity for research engagement. Instead of investing in postgraduate education and teachers with PhDs, the municipality decided to build upon the existing experience and knowledge in the organization. However, this strategy did not advance the municipality’s engagement with external partners nor challenged the internal knowledge concerning research. The quality strategist declared that the decision not to invest in postgraduate education partly had been a financial issue, as investing in education for teachers was a significant expense and the municipality had other financial priorities. The interview with the principal confirmed this. From the principals’ perspective, discussions about postgraduate education were always dismissed due to a lack of designated financial resources.

Principal: The difficult part has always been the economy. (…) I had this discussion not too long ago. I have a teacher who is very interested in postgraduate education. I tried to help her as I think it is important that we improve in this area. But the discussion ended up in who should pay for it. That is so sad. Rather, we need to talk about it as a way to improve ourselves as a municipality.

However, the quality strategist argued that the decision not to invest in postgraduate education or any other strategies to improve the organization’s capacity to participate in research partly also had to do with a lack of understanding of how this could be a ‘benefit’ for student outcome. In addition, the deputy superintendent stressed that the municipality had been involved in several short-term projects and initiatives with different stakeholders that had not impacted student results. With these past experiences and a lack of a more systematic and long-term perspective in the organization, it became difficult for the managers at the administration office to see the ‘benefits’ of the RPP.

Deputy superintendent: If you only think [about it from] short-term perspectives, then you cannot see the point of [the] RPP. We need to have a little more endurance in the municipality for things like this. It is very easy for us to become practical. (…) I’ve been thinking a lot about the fact that we have to [acknowledge] to ourselves that some things take a little longer time than a budget frame [allows].

As with the managers in all the other municipalities that belong to the partnership, the administration office managers in Municipality C participated in the process of developing the ULF RPP. However, Municipality C managers’ participation did not fuel the discussion on how to integrate the RPP in the municipality. The teacher stressed that the municipality ‘demonstrated some kind of immaturity’. Consequently, this immaturity or lack of understanding meant that no initiative had been taken to inform or pressure the politicians to direct attention and financial resources to support other priorities. When the first call for funding was sent out, the administration office managers decided to give the task of coordinating the funding call to a person in the municipality organization without a formal mandate to make decisions and without previous experience of research or collaboration with researchers.

Prior related knowledge and pathways for communication

When the first call for funding for collaborative research was sent out, Municipality B had already built up internal knowledge and was, therefore, ready to embrace the two-step application process. The superintendent was convinced that this was one of the reasons for the municipality´s positive outcome in the first call for funding.

Superintendent: We received a lot of funding [for] Municipality B, and that was because we were so well-prepared. We were used to that way of working and had just been waiting for, like, a race to run. I actually think it was like that. I’m not that surprised. (…) We were sort of trained, and I think that our Ph.D. teachers have been a great support in using the right wording and refining the questions and navigating this. Our organization has also been helpful.

As underlined by the superintendent, the teachers with PhDs had the knowledge required to assist others in formulating high-quality scientific projects. In addition, the scientific leader had been given more or less ‘a free hand’ to build up an organization with meetings where project ideas could be discussed, and teachers could receive feedback on their initial RSs.

Scientific leader: We knew this was coming, so we initiated the whole thing. We had writing sessions and created templates for how to write the application. (…) When they (the teachers) came with their drafts, it could be a few paragraphs, we were maybe 2-3 teachers with PhD there, we went around and helped them with what they wanted. We looked at the drafts and asked [things] like, ‘Are you really answering the questions?’ and ‘You have to write down the research problem and how you intend to examine it’, and so on.

When building up this organization, the scientific leader and her colleagues initially discovered that teachers and principals were a bit hesitant about taking part in activities connected to research. This hesitation was built on uncertainty and an understanding of research and of the university as a domain to which they were unacquainted. Hence, to reach the condition where teachers came to writing sessions with drafts to first-step RSs, other forums to promote interest in research and increase scientific competence in the organization had been implemented earlier. One of these forums aimed to bring teachers and principals interested in examining their practice based on a scientific approach together for discussions and, after a while, present their work in open meetings. In another forum, the teachers with Ph.D. exams had coaching sessions with individual teachers or teacher teams who wanted to work more systematically in their development work. Collectively, these activities strengthened knowledge and self-confidence within the organization. In addition, the administration office managers supported these activities by spreading information about upcoming events and giving teachers time to participate. To distinguish the research-based activities from other initiatives occurring in the municipality, a specific vocabulary was introduced. This vocabulary named for instance, the inquiry-based approach to working, the different forums for scientific conversations, and the group for collaboration between teachers with Ph.D. exams called Lecturers Doing Research in Schools group (LDRS). This vocabulary made it possible to unite the municipality around research-based collaborative work and to address issues across different levels in the municipality.

Deputy superintendent: We, the Deputy superintendents, regularly meet with the LDRIS [Lecturers Doing Research in Schools] group. In these meetings, they cover the things that [are] ongoing. I think it is a prerequisite to make this work. I don’t have the knowledge they have, and I don’t have the connections, either.

In Municipality C, no similar internal knowledge or organization existed. When the call for funding for collaborative research in ULF RPP was sent, the managers and officials at the administration office started a campaign to make principals and teachers write first-step RSs. The managers also appointed a coordinator to handle the formal parts of the application process. However, as no prior activities to promote interest in research or increase scientific competence in the organization had taken place, some principals decided this was not the right thing for their school organization. The deputy superintendent, who at that time worked as a principal, was one of the school leaders who decided not to involve herself or her school in the application process, a decision she perceived to be rather unpopular at the central administration. From her perspective, it was a top-down process in which the schools and principals were not involved until they were admonished to ‘write a research sketch ready to be sent in within three weeks’.

Deputy superintendent: It is impossible to do this quickly; it must be a process and a work that goes on between the applications. You must create a culture for this kind of work. I don’t believe in: ‘Now there are three weeks left until the application, write something down’. I think there must be quality, structure, and culture if it is to become something.

In other schools, principals, teachers, and teacher teams made other decisions. They formulated project ideas and wrote first-step RSs, which they also sent in. As no forums for support or collegial peer review existed, they did their writing.

Teacher: We found it interesting and decided to write something together. We decided on an occasion to meet and sat down and wrote. That’s roughly how it happened. It was a bit random, simply.

Interviewer: There was no forum for this in Municipality C?

Teacher: No, and we did not have contact with anyone outside our team.

Moreover, as the previous knowledge about how to write RSs was limited in Municipality C, the quality of the sketches that were sent in was, as previously presented, assessed as low by the evaluation committee. As the Quality Strategist in Municipality C was a member of the evaluation committee, reading all the sketches that had been submitted, he became aware of the lack of knowledge in Municipality C.

Quality Strategist: We didn’t receive any funding. I was part of the assessment committee, so I sort of know that we also were sorted out quite early in the evaluation process. We lack in our understanding … of the academy, so to speak. (…) We kind of need to step up, and we have talked about it. For example, … the municipalities that received funding and were invited to participate in various projects have a specific competence that we do not have, not least those municipalities that have invested in lecturers.

In the interviews, the teachers and the principal also problematized if Municipality C had the competence to participate in initiatives like the ULF RPP. The principal did not doubt that the teachers had the competence required but questioned the administration office’s knowledge about how to organize collaborative learning about the RPP, something she thought would have taken Municipality C one step further through the application process. The teachers were more convinced that specific knowledge about how to formulate a research question and other expressions would have been good for them to know when they wrote their first-step RS. As ‘ordinary teachers’, this was not part of their repertoire, they argued.

Boundary infrastructure

Through the analysis, it also became clear that Municipality B, aside from its high level of absorptive capacity, had a boundary infrastructure including boundary spanners, practices, and objects that worked across the municipality and the university and thus strengthened the municipality’s conditions responding to the ULF RPP initial call for funding. In Municipality C, no similar boundary infrastructure existed.

As reported above, four teachers in Municipality B were involved in coursework for or had completed their Ph.D.s. Through their postgraduate studies, these teachers had established relationships with university researchers and recommended researchers interested in taking part in RPP projects to contact teachers and vice-versa. In that sense, the municipality had designated roles in the organization that had the competence, through knowledge and connections, to bring together educational practice and academia with a solid aim of developing practice-based research. Notably, the scientific leader in Municipality B, who has a dual function and works as a teacher, appears to have a significant role as a boundary-spanner.

Scientific leader: I have the pleasure of participating in a research environment at the university. I am always very welcome in all environments, but it is, after all, based on personal initiative. There are no formal paths.

Additionally, the deputy superintendent emphasizes the vital role of the scientific leader. She highlights her important work facilitating connections between teachers, principals, administration office managers, and officials in research and development. Moreover, she stresses her role in ensuring the municipality’s interest regarding this matter through her transition across different sites, i.e. the municipality and the university.

Deputy superintendent: She kind of has a good feeling for questions like, ‘What’s going on?’, ‘What can be favourable for us?’ but she also has the courage to question things. That’s why she is important to us.

As previously presented, the scientific leader and her colleagues had introduced different practices where they collaboratively worked with teachers and principals in research-based activities. One of these activities was the ULF RRP’s call for funding. However, as the scientific leader was familiar with university routines, she had identified that the application process (ending early fall) required a time plan starting in the early spring since Swedish teachers have a 10-week summer holiday.

Scientific leader: Before the summer, I already received several questions (from teachers). We started to prepare templates so that they could start writing their sketches.

To support the teachers and to create optimal conditions for writing good sketches, this time plan was essential. Forums to discuss research ideas and to give feedback on early drafts were implemented. Additionally, objects such as templates for structuring sketches were tried out and developed. This was important for creating confidence among the teachers and the principals, consolidating that their ideas matched the expectations in the education research community. These boundary practices and objects contributed to closing gaps (i.e. culture, professional norms, organizational routines) between the municipality and the university.

Conclusions and discussion

At its core, this article studied a RPP whose leading research strategy was calls for research funding designed as a two-step process including RSs and complete applications. When the strategy was first implemented, several challenges emerged. Despite the support and engagement for the strategy among RPP partners’ leadership and the call’s inclusive aim to provide teachers and researchers equal opportunities to participate, we identified significant variation in municipalities’ success (regarding research funding). The strategic selection of two municipalities that showed uneven success despite facing similar socioeconomic and demographic conditions provided a unique opportunity to explore in more depth the conditions behind these differences (Farrell et al., Citation2022). We found that the organizational capacity of the two municipalities differed and that boundary spanners had a crucial role and function within the municipalities’ internal organization.

Significant results of this study include that the municipal organizational capacity – the absorptive capacity and the existing boundary infrastructure – differed significantly between the two sites. Because the municipalities’ absorptive capacity varied, they faced different possibilities when enacting the call to fund collaborative research in their internal organizations. The results show that, on the one hand, collaborative research in RPPs is facilitated by local political goals on evidence-based education and related investments and by internal knowledge and communication structures continuously supporting teachers’ engagement; on the other hand, the lack of goals for research use, investments, and supporting structures hinders such research. In addition, we identified the importance of a supportive boundary infrastructure. In detail, Municipality B had a high level of absorptive capacity; among other things, this included well-established communication pathways connected to research. However, we also found that the municipality had designed a boundary infrastructure explicitly used in the calls. Teachers who had completed postgraduate studies played a leading role as boundary spanners, moving back and forth between the university and the municipality and helping researchers and teachers meet and make connections between their research and practice. On the other hand, Municipality C had a low level of absorptive capacity and lacked a boundary infrastructure. Economic investments were prioritized in other areas. Consequently, there was a lack of understanding in the municipality regarding the potential contribution of research.

This study contributes to the literature that has called for studies on strategies participants use in partnerships to address challenges (Coburn & Penuel, Citation2016). It shows that the joint commitment of partners to design core research activities for inclusivity strategically does not sufficiently provide teachers with equal opportunities to engage in research. Partnership success is also dependent on the organizational capacity of involved partners. Additionally, the results illustrate that organizations with similar conditions can differ in their preparation to engage in and learn from encounters at boundaries (Farrell et al., Citation2022). Our results also validate prior research on the importance of boundary spanners as valuable in their ability to transition across the sites of research and practice (Williams, Citation2002). However, it contradicts Sjölund and Lindvall (Citation2023) that ‘researchers have an authoritative position from which to work on amplifying’ teachers’ voices by demonstrating the crucial role of municipally employed teachers with postdoctoral education.

Additionally, this study significantly contributes to the literature on ULF. Although this study aligns with Bergmark and Hansson (Citation2021, p. 451) that ‘strategic effort to create supportive structures’ by the municipality management supports teachers’ enactment of evidence-based education, it demonstrates that the lack of similar structures hinders research collaboration. It provides valuable insights that corroborate the findings by Öijen et al. (Citation2020), who observed variations in municipal managers’ readiness for research collaboration within their organizations.

The implications of these results are particularly important for educational policy. The varying levels of the municipalities’ absorptive capacities illustrate establishing conditions to facilitate teachers’ engagement in research is possible. However, generating the necessary conditions to realize this engagement also requires strategic leadership, goals, and investments. We believe that organizations with a high absorptive capacity can serve as a proof of principle for organizations that aim to enhance their internal structures. However, we concur with Cohen and Levinthal (Citation1990, p. 136) that the ‘simple notion [of] prior knowledge [underlying] absorptive capacity has important implications for the development of absorptive capacity over time and, in turn, the innovative performance of organizations’ (Cohen & Levinthal, Citation1990, p. 136). Accordingly, municipalities with a high absorptive capacity may steadily accumulate more of this capacity, deepening any already unequal conditions.

To some extent, this is a considerable risk in a decentralized school system like the Swedish one. The 290 municipalities in Sweden are substantially different in their sizes and resources. They also have extended autonomy to choose and design their internal organization. On a similar note, Benerdal and Westman (Citation2023, p. 10) anticipate unequal conditions among universities in RPPs: ‘If, for example, members are included based on historic merit or ease and no new agreements are constructed, there is a potential risk that collaborative actors will miss out on important conversations regarding the fundamental values of a collaboration’.

In sum, it remains to be seen whether municipalities see absorptive capacity in educational research competencies or limitations as resources to be well-invested and whether HEIs value organizing for collaboration. In RPP development, HEIs must handle the above diversity when collaborating with municipalities building models like the ULF RPP. This study’s results, which indicate that the ‘in-house’ municipal research capacity seems to have a considerable impact, point in this direction. In short, the results call for more situationally adapting processes in related organizations when developing national RPP initiatives like the ULF. Some municipalities may require much more scaffolding and support than others to facilitate collaborative research. When developing the mutual boundary infrastructure – the networks, practices, and objects across partners – this is essential to consider. It is a question of the utmost importance for improving teachers’ and researchers’ opportunity to engage in collaborative research and for, in the longer run, meeting the education act requirements on evidence-based education.

Limitations and implications for further research

One of this study’s primary limitations is that it did not analyse the organizational capacities of the university that belongs to the ULF RPP. As argued by Lillejord and Børte (Citation2016), all involved in a partnership must accommodate their internal structures and processes to meet their common objectives. To generate a deeper understanding of what hinders and facilitates enacting the partnerships’ core strategies, we recommend that future studies include the experiences of a broader range of actors in a partnership, particularly HEIs and school districts. Future research should explore whether municipalities that transition from less to more successful exhibit traces of increased absorptive capacity, as well as investigating municipalities in other RPPs. Such studies are crucial for gaining deeper insights into the factors influencing municipalities’ initial organizational structures.

In addition, the small number of respondents who were managers and officials at the municipal level, as well as principals and teachers willing to share their experiences, provide an additional limitation to this study, narrowing the scope of its conclusions. Accordingly, the results must be interpreted cautiously, and there are limited possibilities for generalization. Moreover, we wish to highlight that some of the author team has been involved in the ULF RPP through different roles and functions. This involvement has made us aware of this partnership’s context and circumstances, allowing us a deeper understanding of its critical elements. Although this close relationship could also affect our findings, as interviews were conducted individually and by authors uninvolved in the partnership, we believe that the risk that our involvement may cause respondents not to share their genuine beliefs is limited.

Statements and declarations

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Supporting data is not available. Sharing supporting data, i.e. full interview transcripts, would risk the anonymity of research participants due to context specific circumstances.

Notes

1. Quality Strategist is a position at the municipal level that coordinates quality work, conducts reviews on behalf of municipal officials and politicians, and supports principals’ and schools’ improvement work.

References

- Ahlstrand, P., & Andersson, N. (2021). Learning study – a model for practice-based research in a Swedish theatre classroom. Youth Theatre Journal, 35(1–2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/08929092.2021.1910602

- Arreman, E. I. (2008). The process of finding a shape: Stabilising new research structures in Swedish teacher education, 2000–2007. European Educational Research Journal, 7(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2008.7.2.157

- Benerdal, M., & Westman, A.-K. (2023). Organising for collaboration with schools: Experiences from six Swedish universities. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. Published online. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2023.2263476

- Bergmark, U., & Hansson, K. (2021). How teachers and principals enact the policy of building education in Sweden on a scientific foundation and proven experience: Challenges and opportunities. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(3), 448–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1713883

- Christianakis, M. (2010). Collaborative research and teacher education. Issues in Teacher Education, 19(2), 109–125.

- Coburn, C. E., & Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education: Outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educational Researcher, 45(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16631750

- Coburn, C. E., Penuel, W. R., & Geil, K. (2013). Research–practice partnerships at the district level: A new strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement. William T. Grant Foundation.

- Coburn, C. E., Toure, J., & Yamashita, M. (2009). Evidence, interpretation, and persuasion: Instructional decision making at the district central office. Teachers College Record, 111(4), 1115–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911100403

- Cochrane-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1993). Inside/outside: Teacher research and knowledge. Teachers College Press.

- Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393553

- Datnow, A. (2020). The role of teachers in educational reform: A 20-year perspective. Journal of Educational Change, 21(3), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09372-5

- Farrell, C. C., & Coburn, C. E. (2017). Absorptive capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding district central office learning. Journal of Educational Change, 18(2), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9291-7

- Farrell, C. C., Coburn, C., & Chong, S. (2019). Under what conditions do school districts learn from external partners? The role of absorptive capacity. American Educational Research Journal, 56(3), 955–994. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218808219

- Farrell, C. C., Harrison, C., & Coburn, C. E. (2019). “What the hell is this, and who the hell are you?” Role and identity negotiation in research-practice partnerships. American Educational Research Association Open, 5(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419849595

- Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A., Anderson, E. R., Bohannon, A. X., Coburn, C. E., & Brown, S. L. (2022). Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research–practice partnerships. Educational Researcher, 51(3), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211069073

- Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Coburn, C., Daniel, J., & Steup, L. (2021). Research–practice partnerships in education: The state of the field. William T. Grant Foundation.

- Fjørtoft, H., & Sandvik, L. V. (2021). Leveraging situated strategies in research–practice partnerships: Participatory dialogue in a Norwegian school. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101063

- Forssten Seiser, A., & Portfelt, I. (2024). Critical aspects to consider when establishing collaboration between school leaders and researchers: Two cases from Sweden. Educational Action Research, 32(2), 260–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2022.2110137

- Furuhagen, B., Holmén, J., & Säntti, J. (2019). The ideal teacher: Orientations of teacher education in Sweden and Finland after the second world war. History of Education, 48(6), 784–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760X.2019.1606945

- Gibbs, G. R. (2018). Analyzing qualitative data (Vol. 6). Sage.

- Håkansson, J., & Adolfsson, C.-H. (2022). Local education authority’s quality management within a coupled school system: Strategies, actions, and tensions. Journal of Educational Change, 23(3), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09414-6

- Hopkins, M., Weddle, H., Gluckman, M., & Gautsch, L. (2019). Boundary crossings in a professional association: The dynamics of research use among state leaders and researchers in a research-practice partnership. American Educational Research Association Open, 5(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419891964

- Jarl, M., Fredriksson, A., & Persson, P. (2012). New public management in public education: A catalyst for the professionalization of Swedish school principals. Public Administration, 90(2), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01995.x

- Jarl, M., Taube, M., & Björklund, C. (2024). Exploring roles in teacher–researcher collaboration: Examples from a Swedish research–practice partnership in education. Education Inquiry, ahead of print. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2024.2324518

- Kirsten, N., & Wermke, W. (2016). Governing teachers by professional development: State programmes for continuing professional development in Sweden since 1991. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 49(3), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1151082

- Lau, S. M. C., & Still, S. (2014). Participatory research with teachers: Toward a pragmatic and dynamic view of equity and parity in research relationships. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.882313

- Liljenberg, M., & Andersson, K. (2023). Recognizing LEA officials’ translator competences when implementing new policy directives for documentation of schools’ systematic quality work. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2023.2206882

- Lillejord, S., & Børte, K. (2016). Partnership in teacher education - a research mapping. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(5), 550–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1252911

- Lundahl, L. (2005). A matter of self-governance and control. The reconstruction of Swedish education policy: 1980-2003. European Education, 37(1), 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2005.11042375

- Magnusson, P., & Malmström, M. (2023). Practice-near school research in Sweden: Tendencies and teachers’ roles. Education Inquiry, 14(3), 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2022.2028440

- Malmström, M. (2023). Anticipations of practice-near school research in Sweden. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 9(3), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2023.2236751

- Montin, S. (2015). Municipalities, regions, and county councils: Actors and institutions. In J. Pierre (Ed.), The oxford handbook of Swedish politics (pp. 367–382). Oxford University Press.

- Nordholm, D., Arnqvist, A., & Nihlfors, E. (2021). Sense-making of autonomy and control. Comparing school leaders in public and independent schools in a Swedish case. Journal of Educational Change, 23(4), 497–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09429-z

- Nutley, S., Jung, T., & Walter, I. (2008). The many forms of research-informed practice: A framework for mapping diversity. Cambridge Journal of Education, 38(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640801889980

- Öijen, L., Öhman-Sandberg, A., & Haglind, U. (2020). Kommunala skolhuvudmäns syn på samverkan med universitet kring praktiknära forskning. Rapport 2020:4. [Municipalities’ perceptions of collaboration with universities on practice-near research. Report 2024:4.]. Örebro University

- Penuel, W., Allen, A.-R., Coburn, C. E., & Farrell, C. (2015). Conceptualizing research-practice partnerships as joint work at boundaries. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 20(1–2), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2014.988334

- Penuel, W. R., Riedy, R., Barber, M. S., Peurach, D. J., LeBouef, W., & Clark, T. (2020). Principles of collaborative education research with stakeholders: Toward requirements for a new research and development infrastructure. Review of Educational Research, 90(5), 627–674. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320938126

- Popa, N. (2023). Navigating contexts to facilitate RPPs. Learning from local and international experiences. Roundtable report Unpublished. Karlstad University.

- Prøitz, T. S., & Rye, E. (2023). Actor roles in research–practice relationships: Equality in policy–practice nexuses. In T. S. Prøitz, P. Aasen, & W. Wermke (Eds.), From education policy to education practice: Unpacking the Nexus (pp. 287–304). Springer.

- Prøitz, T. S., Rye, E., Borgen, J. S., Barstad, K., Afdal, H., Mausethagen, S., & Aasen, P. (2022). Education, learning, research. Report from an evaluation of the ULF initiative [Utbildning, lärande, forskning. Slutrapport från en utvärderingsstudie av ULF-försöksverksamhet]. Skriftserien nr 87. Universitetet i Sørøst-Norge.

- SFS 2010:800 Skollag [Education Act].

- Sjölund, S., & Lindvall, J. (2023). Examining boundaries in large-scale educational research-practice partnership. Journal of Educational Change, 25(2), 417–443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-023-09498-2

- Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., & Ryve, A. (2022). Using research to inform practice through research–practice partnerships: A systematic literature review. Review of Education, 10(1), e3337. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3337

- SOU 2018:19. Forska tillsammans – samverkan för lärande och förbättring. Betänkande av utredningen om praktiknära skolforskning i samverkan. In [Research together – collaboration for learning and improvement. Official Governmental Report.]. Norstedts Juridik AB.

- Spillane, J. P. (1998). State policy and the non-monolithic nature of the local school district: Organizational and professional considerations. American Educational Research Journal, 35(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312035001033

- Strandler, O., & Harling, M. (2023). The problem of “problematic school absenteeism” – on the logics of institutional work with absent students’ well-being and knowledge development. European Education, 55(3–4), 172–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2023.2251018

- Tengberg, M., van Bommel, J., Nilsberth, M., Walkert, M., & Nissen, A. (2021). The quality of instruction in Swedish lower secondary language arts and mathematics. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(5), 760–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2021.1910564

- Wagner, J. (1997). The unavoidable intervention of educational research: A framework for reconsidering researcher–practitioner cooperation. Educational Researcher, 26(7), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X026007013

- Wentworth, L., Arce-Trigatti, P., Conaway, C., & Shewchuk, S. (2023). Brokering in education research–practice partnerships. A guide for educational professionals and researchers. Routledge.

- Wentworth, L., Mazzeo, C., & Connolly, F. (2017). Research practice partnerships: A strategy for promoting evidence-based decision-making in education. Educational Research, 59(2), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/07391102.2017.1314108

- Westbrook, H., Janssen, F., Mathijsen, I., Doyle, W, W., & Doyle, W. (2022). Teachers as researchers and the issue of practicality. European Journal of Teacher Education, 45(1), 60–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1803268

- Williams, P. (2002). The competent boundary spanner. Public Administration, 80(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00296